Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Article 2013 1 CLJ I Caveats, Prohibitory Orders and Injunctions Under The National Land Code 1965

Загружено:

givamathanОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Article 2013 1 CLJ I Caveats, Prohibitory Orders and Injunctions Under The National Land Code 1965

Загружено:

givamathanАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

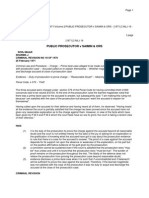

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

Caveats, Prohibitory Orders And Injunctions Under The National Land Code 1965*

by Datuk Dr. Wong Kim Fatt** Introduction The Malaysian National Land Code 1965 (the NLC), modelled on the Australian Torrens System, came into force on 1 January 1966 and applies to the eleven states of Peninsular Malaysia, the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur (with effect from 1 February 1974 P.U. (A) 56 of 1974), and the Federal Territory of Putrajaya (with effect from 1 February 2001, see Federal Territory of Putrajaya (Modification of National Land Code) Order 2001). Before the NLC came into force in 1966, there were seven separate land laws in Peninsular Malaysia, ie, (a) the National Land Code (Penang and Malacca Titles) Act 1963 codifying the land laws of Penang and Malacca, (b) the Federated Malay States Land Code of 1926 (Cap 138) applicable to the four federated states of Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, Perak and Selangor, (c) the five land laws of each of the states of Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis and Terengganu. As for the State of Johor, its land laws were codified as the Land Enactment No. 1 (2 of 1910). It was in operation for over 50 years until it was replaced by the NLC in 1966. It is interesting to note that under s. 2 of the repealed Johore Land Enactment, the court means the Supreme Court of Johore, and only one form of caveat in Schedule L is provided under s. 55 of this Enactment, where the person whose title is bound by the caveat is called the caveatee, an expression not

L A W

* This article is based on a talk given by the writer on Day 1 in a 3-day seminar on Land Development Issues held on 27 November 2012 in Mutiara Hotel, Johor Bahru, organised by Uni-Link Smart Venture Sdn Bhd. I wish to thank Mr. Wong Boon Lee, Mr. Wong Boon Chong and Miss Kelly Yeo Hui Yain for the valuable discussions I had with them on the relevant subjects and authorities. I am solely responsible for the shortcomings of this article which discusses restraints of dealings, injunctions, and the appeal procedures in the Malaysian Courts. ** Advocate & Solicitor Co-founder & Partner, Gulam & Wong

ii

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

used in the NLC. To meet modern requirements and for uniformity, it was necessary to have a single Land Code to replace these seven out-moded separate land laws in the States of Malaya before they achieved independence on 31 August 1957. Clause 1 of the Introduction to the Explanatory Statement of the National Land Code Bill published in the Federal Government Gazette on 1 July 1965 reads:

Under the present law of the States of Malaya two quite different systems of land tenure exist side by side: (a) The States of Penang and Malacca retain a system peculiar to the pre-war Straits Settlements (modelled on the English laws of property and conveyancing) whereby privately executed deeds are the basis of title to land; (b) The nine Malay States, by contrast, employ a system based on the principle that private rights in land can derive only from express grant by the State or secondarily from State registration of subsequent statutory dealings.

The purpose of the Bill is stated in cl. 4 of the Explanatory Statement:

The purpose of the present Bill is to remedy this state of affairs to replace the complex of seven separate and out-moded laws by a single statute of general application throughout all eleven States and so establish a uniform system of land tenure and dealing appropriate to the present day. For such a unified system there can be only one model that is already in existence in the majority of the States as described in (b) above. In itself it is entirely acceptable; it is efficient, well tried and familiar and can without difficulty be modified to suit modern requirements. In nine States its introduction will mean no break in continuity and in Penang and Malacca the way for its introduction has already been prepared by the National Land Code (Penang and Malacca Titles) Act 1963 which, when brought into force, will abolish the existing system described in (a).

L A W

Caveat Under The NLC Under s. 5 of the NLC on interpretation, a caveat means a registered caveat. This shows that a caveat is not effective unless registered under the provisions of the NLC. A caveat, when

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

iii

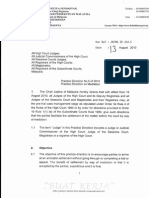

registered, will have the particulars of registration, the serial or presentation number, with the date and time of entry, and signed under his seal by the Registrar of Titles in respect of a registry title or the Land Administrator in respect of a Land Office title. Thus a caveat entered under the NLC is an entry or an endorsement on the register document of title under the hand and seal of the Registrar of Titles or the Land Administrator, as the case may be. Unless the caveator gives his consent in writing under s. 322(5)(b) of the NLC, a caveat shall prohibit dealings by the registered proprietor in the land or interest affected. A caveat gives notice on the register document of titles to the world at large as well as protects the existing interests or claims to such interest of the caveator in the land or particular interest affected. A caveat, often described as a temporary or interlocutory statutory injunction, is not an instrument of dealing and it creates no new interest in land. However, when determining the priority of competing claims or equities between the claimants in any dispute concerning the land or interest bound by the caveat, it is material to note that, everything being equal, the first in time prevails. The New Rules Of Court 2012 Effective From 1 August 2012 It should be noted that, with effect from 1 August 2012, the new Rules of Court 2012 (P.U. (A) 205/2012) came into operation, repealing, under O. 94 r. 1, the Rules of the High Court 1980 and the Subordinate Courts Rules 1980. Language Of The Courts

L A W

Under the National Language Acts 1963/1967, in Peninsular Malaysia, the language of the courts is the national language (bahasa kebangsaan), ie, the Malay language. However, currently the language of the courts in the two East Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak is the English language. Writs, pleadings, cause papers, orders, and legal documents in the courts in these two states are filed in English and proceedings are still conducted in English. In Peninsular Malaysia, all writs pleadings, cause papers, orders and legal documents filed in the courts, and correspondence with the courts, government ministries and

iv

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

departments, shall be in the national language (bahasa kebangsaan), other than the giving of evidence by witnesses. However, all these documents filed in the courts in the national language may be accompanied by their English translations. In practice court proceedings in chambers or in open court are very often conducted in English in the High Court, the Court of Appeal, and the Federal Court in Peninsular Malaysia, and written and oral submissions are frequently made in English in the interest of justice. In these superior courts counsel and judges more often conduct the proceedings in English, unlike in the Subordinate Courts, ie, the Magistrates Court and the Sessions Court where proceedings are virtually conducted in the national language, except the giving of evidence by witnesses. Section 8 of the National Language Act reads:

8. All proceedings (other than giving of evidence by a witness) in the Federal Court, the Court of Appeal, the High Court or any Subordinate Court shall be in the national language: Provided that the Court may either of its own motion or on the application of any party to any proceedings and after considering the interests of justice in those proceedings, order that the proceedings (other than the giving of evidence by a witness) shall be partly in the national language and partly in the English language.

In this connection, it is relevant to refer to art. 152 of the Federal Constitution which reads:

152 National language

L A W

(1) The national language shall be the Malay language and shall be in such script as Parliament may by law provide: Provided that (a) no person shall be prohibited or prevented from using (otherwise than for official purposes), or from teaching or learning, any other language; and (b) nothing in this Clause shall prejudice the right of the Federal Government or of any State Government to preserve and sustain the use and study of the language of any other community in the Federation.

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

. (4) Notwithstanding the provisions of Clause (1), for a period of ten years after Merdeka Day, and thereafter until Parliament otherwise provides, all proceedings in the Federal Court, the Court of Appeal or a High Court shall be in the English language: Provided that, if the Court and counsel on both sides agree, evidence taken in language spoken by the witness need not be translated into or recorded in English. (5) Notwithstanding the provision of Clause (1), until Parliament otherwise provides, all proceedings in subordinate courts, other than the taking of evidence, shall be in the English language.

Grounds Of Judgment In English Are Lawful The crucial national language issue concerning the grounds of judgment written in the English language came up for adjudication by the Federal Court in a criminal case in Harcharan Singh Piara Singh v. PP [2011] 6 CLJ 625 in which the Federal Court unanimously held that the grounds of judgment in the English language do not contravene the National Language Act and the court has a wide discretion to conduct proceedings in English or in the national language. Delivering the judgment of the Federal Court, Richard Malanjum CJ (Sabah and Sarawak) said at p. 636:

[30] Accordingly, on the authority of Dato Seri Anwar Ibrahim v. Tun Dr. Mahathir (supra) which we accept as good law, we hold that grounds of judgments do not fall within s. 8 of the Act, and the court has a wide discretion whether to conduct proceedings in the English language or in the national language, be it on the courts own motion or on application by the parties. Further, judges have the discretion to provide their grounds of judgment in either in the national language or the English language. The choice of language adopted by the respective judge is not open for challenge as long as it is in the national language or the English language.

L A W

vi

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

In the 1991 issue of the Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, I had the opportunity at pp. 611 and 612 to make the following observations on the language issue:

For over a century, English has been the language, both spoken and written, of the courts in Peninsular Malaysia. The change came when s. 8 of the National Language Act was amended by the National Language (Amendment) Act 1990 which took effect from 30 March 1990 and administratively from 1 June 1990 by Practice Direction of the Chief Justice (Malaya). ... The Bench and the Bar in Peninsular Malaysia are doing reasonably well in the conduct of cases in the National language, especially in the Subordinate Courts. Judges of the High court and Supreme Court are encouraged to write their judgments in the National Language. Some of these judgments and their English translations, have found their way into the law journals. However, it is respectfully urged that Malaysian judges should continue to write their judgments in English so that these may be read and studied in other parts of the world interested in Malaysian laws because their published judgments in the Malay language will hardly be read or understood in the English-speaking world. As long term objective, English should continue to be used, alongside Malay, where justice requires it in the superior courts of the country. The best of post-independence judgments written in the English language by judges of the Malaysian High Court, the Federal Court and its successor, the Supreme Court [now the Federal Court with the Court of Appeal below it] are of comparable standard and quality with those of their counterparts in the Commonwealth.

L A W

National Language Not Threatened Now looking back the last 55 years since Merdeka Day on 31 August 1957, I am of the view that the secure constitutional position of the Malay language as the national language of Malaysia has never been threatened, and will never be, by the continued use of English in the Malaysian Courts. Malaysians of different races accept the Malay language as the national language of the country. Mastery and use of the English language will be to the benefit of Malaysia and her citizens in the international and domestic scenes, now and in the future.

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

vii

Application Of The New Rules Order 1 r. 2 of the Rules of Court 2012 provides as follows:

2(1) Subject to paragraph (2), these Rules apply to all proceedings in (a) the Magistrates Court; (b) the Sessions Court; and (c) the High Court. (2) These Rules do not have effect in relation to proceedings in respect of which rules have been or may be made under any written law for the specific purpose of such proceedings or in relation to any criminal proceeding.

Overriding Objective Of The Rules: Justice It should be borne in mind at all times that the overriding objective of these Rules is justice, as provided in O. 1A reading as follows:

In administering these Rules, the Court or a Judge shall have regard to the overriding interest of justice and not only to the technical non-compliance with these Rules.

Non-Compliance With The Rules

Under O. 2 r. 1(1) mere non-compliance of the Rules of 2012 does not nullify the proceedings. It is significant to note that under O. 2 r. 1(2), the parties must now assist the court to achieve the overriding objective of dealing with the cases justly. Commence By Writ, Or Originating Summons, Or Notice Of Application We should take note that O. 5 of the Rules of 2012 makes provisions for the mode of commencement of civil proceedings by writ or originating summons (rr. 3 and 4). Order 32 r. 1 of these Rules provides that every application in chambers shall be made by notice of application in the new Form 57, replacing, but practically in the same format of, the old familiar summons-inchambers, except the new Form 57 is headed Notice of Application.

L A W

viii

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

Cases In Which The Rules Of Court 2012 Are Inapplicable Currently, in Peninsular Malaysia, proceedings relating to company winding-up matters may still be filed in the English language. Under the Appendix C (O. 94 r. 2), the Rules of Court 2012 do not apply to the following proceedings under the following laws:

Appendix C List Of Exempted Laws 1. Bankruptcy proceedings 2. Proceedings relating to the winding up of companies and capital reduction 3. Criminal proceedings 4. Proceedings under the Elections Offences Act 1954 5. Matrimonial proceedings 6. Land reference Bankruptcy Act 1967 Companies Act 1965

Criminal Procedure Code [Act 593] Elections Offences Act 1954 [Act 5] Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act 1976 [Act 164]

7. Admission to the Bar

L A W

Land Acquisition Act 1960 [Act 486] Legal Profession Act 1976 [Act 166], Advocates Ordinance of Sabah [Sabah Cap. 2], Advocates Ordinance of Sarawak [Sarawak Cap. 110]

8. Proceedings under the Income Tax Act 1967

Income Tax Act 1967 [Act 53]

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

ix

Proceedings Under The New Rules Proceedings relating to caveats under the caveat system, prohibitory orders, and injunctions relating to the NLC should now be taken under the Rules of Court 2012, with effect from 1 August 2012. On the caveat system, there are four types of caveats provided under Part Nineteen on Restraints on Dealing in the NLC. These caveats are the Registrars caveat, private caveat, lien-holders caveats, and trust caveat. Over the last 46 years since the coming into force of the NLC in 1966, there have been many amendments made to the NLC. In the future, there will many more arising under the NLC amendments in order to update the NLC to meet future requirements. Our courts have adjudicated on many disputes and have had many cases decided and reported in the law reports for guidance of the legal profession. The Registrars Caveat Form Of Registrars Caveat The Registrars caveat is now entered by the Registrar in Form 19F (previously Form 7) on the register document of title to any land under specified circumstances. Form 19F provides as follows:

By virtue of the power conferred on me by section 320 of the National Land Code, I have entered a Registrars Caveat on the land held under Title No. ..................... for Lot No. .....*Town/Village/Mukim ... District .. for the following reason: ......... 2. This caveat shall, so long as it continues in force, prohibit the registration, endorsement or entry on that document, of any instrument of dealing, any claim to the benefit of a tenancy exempt from registration and any lien-holders caveat. This prohibition shall apply to any such instrument, claim or application notwithstanding that it was received before this caveat was entered.

L A W

[Form 19F] (Section 320) ENTRY OF REGISTRARS CAVEAT

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

Dated the day of .., 20 . .. Registrar/Land Administrator

Definitions Note the following definitions under s. 5 of the NLC:

Court means the High Court in Malaya. Dealing means any transaction with respect to alienated land effected under the powers conferred by Division IV, and any like transaction effected under the provisions of any previous land law, but does not include any caveat or prohibitory order. Registrar means (a) in relation to land held or to be held under Registry title, or under the form of qualified title corresponding to Registry title, or under subsidiary title dependent on a Registry title, a Registrar of Titles or Deputy Registrar of Titles appointed under section 12; (b) in relation to land held or to be held under Land Office title, or under the form of qualified title corresponding thereto, or under subsidiary title dependent on a Land Office title, the Land Administrator. Registry title means title evidenced by a grant or a State lease, or by any document of title registered in a Registry under the provisions of any previous land law. Land Office title means title evidenced by a Mukim grant or Mukim lease, or by any document of title registered in a Land Office under the provisions of any previous land law. Land Administrator means a Land Administrator appointed under section 12, and includes an Assistant Land Administrator appointed thereunder; and, in relation to any land, references to the Land Administrator shall be construed as references to the Land Administrator, or any Assistant Land Administrator, having jurisdiction in the district or sub-district in which the land is situated.

L A W

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xi

Prohibitive Effect Of Registrars Caveat Under s. 319(b) of the NLC, so long as the Registrars caveat remains in force, it shall prohibit the registration, endorsement or entry of:

(i) any instrument of dealing; (ii) any claim to the benefit of a tenancy exempt from registration; and (iii) any lien-holders caveat.

The Registrars caveat is more powerful than a private caveat in that it can operate backward to prevent registration of an instrument of dealing under s. 319(b) (i) above like a transfer of land in Form 14A, or the tenancy claim under (ii) above or a lienholders caveat under (iii) above, notwithstanding these documents were presented, but had not been registered or endorsed, prior to the entry of the Registrars caveat. Under s. 319(3), the Registrar has the discretion to waive the prohibition. Circumstances For Entry Of The Registrars Caveat Section 320 of the NLC, as amended in 1979 by Act A444 by the insertion of subsection (1)(ba), now reads as follows:

320 Circumstances in which Registrars caveats may be entered (1) Subject to sub-section (2), a Registrars caveat may be entered in respect of any land wherever such appears to the Registrar to be necessary or desirable (a) for the prevention of fraud or improper dealing; or (b) for protecting the interests of (i) the Federation or the State Authority; or (ii) any person who is in his opinion under the disability of minority, mental disorder or unsoundness of mind, or is shown to his satisfaction to be absent from the Federation; or (ba) for securing that the land will be available to satisfy the whole or part of any debt due to the Federation or the State Authority, whether such debt is secured or unsecured and whether or not judgment thereon has been obtained; or

L A W

xii

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

(c) by reason of some error appearing to him to have been made in the register or issue document of title to the land or any other instrument relating thereto. (2) Knowledge by the Registrar of the fact that any land or interest therein has been acquired, or is to be held, by any person or body in a fiduciary capacity shall not of itself constitute a ground for entering a Registrars caveat in respect of that land.

Cancellation Of The Registrars Caveat Section 321(3) of the NLC provides as follows:

(3) A Registrars caveat shall continue in force until it is cancelled by the Registrar (a) of his own motion; or (b) on an application in that behalf by the proprietor of the land affected; or (c) pursuant to any order of the Court made on an appeal under section 418 against his decision to enter the caveat, or his refusal of any application for its cancellation under paragraph (b).

Authority Of The High Court

The decision, including any act, omission, refusal, direction or order, of the Registrar or the Land Administrator is subject to the control and order of the High Court in proceedings relating to land. It is the duty of the Registrar or the Land Administrator to comply forthwith with the order of the court under s. 417(1) of the NLC. Appeals To The High Court It is important to note that under s. 418(1) of the NLC, any person or body aggrieved by the decision of the Registrar or Land Administrator has the right of appeal to the High Court within the period of three months beginning from the date of communication of the decision. Unlike O. 3 r. 5 of the Rules of Court 2012 where the High Court has the discretion to extend time, the court has no jurisdiction to extend this statutory period of three months under s. 418(1) of the NLC. See the Federal Court case of Land Executive Committee of Federal Territory v. Syarikat Harper Gilfillan

L A W

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xiii

Bhd [1980] 1 LNS 150; [1981] 1 MLJ 234, where Raja Azlan Shah AG LP (as he then was) said at p. 237:

Reading section 418 of the Code, we are satisfied that the latter is the correct interpretation. Having regard to the special provision for limiting the time within which to enforce the right, the indications are that Parliament has by using plain and unambiguous language intended the right to be exclusive of any other mode of enforcing it. The time-limit is the foundation of the right given in the section. It is in the highest degree improbable that the period of three months as a limitation would have been inserted if an indefinite period were intended to be given. The period of the three months is obviously for the purpose of preventing stale claims.

In Public Bank Bhd v. Pengarah Tanah & Galian & Anor [1989] 1 LNS 159; [1990] 2 MLJ 510, Mohtar Abdullah JC (as he then was), without referring to the above earlier case of Land Executive Committee of Federal Territory, held that the three-month period runs from the date of communication. His Lordship said at p. 510:

By virtue of s. 418, the time limited for appeal against the order of the registrar is three months from the date of communication of the decision of the registrar. The decision of the registrar in this case is the decision to enter the caveat and not the decision to refuse the application for cancellation of the said caveat since para (b) and the second limb of para (c) of s. 321 are not relevant in the present case. Therefore, for the purpose of computation of time under s. 418, it is crystal clear that time runs from the date of communication of the decision of the registrar to enter the caveat, ie, 20 October 1988. The plaintiffs appeal under s. 418 was entered on 29 January 1989. Therefore, I hold that the Plaintiffs appeal was filed out of time and consequently time barred.

L A W

Appeal Procedure The appeal procedure was, before the commencement of the Rules of Court 2012 on 1 August 2012, by originating motion. Under the new Rules of 2012, I am of the opinion that the appeal will be by originating summons under O. 5 r. 4. Section 418 of the NLC reads:

418(1) Any person or body aggrieved by any decision under this Act of the State Director, the Registrar or any Land Administrator may, at any time within the period of three months beginning with the date on which it was communicated to him, appeal therefrom to the Court.

xiv

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

(2) Any such appeal shall be made in accordance with the provisions of any written law for the time bring in force relating to civil procedure; and the Court shall make such order thereon as it considers just. (3) In this section decision includes any act, omission, refusal, direction or order.

Person Aggrieved In a nutshell, a person aggrieved is one whose legal right or interest is affected by the wrongful act or conduct of another person. Following the Privy Council case of AG of Gambia v. Pierre Sarr Njie [1961] AC 617, Mokhtar Sidin JCA, in delivering the judgment of the Court of Appeal in Wu Shu Chen & Anor v. Raja Zainal Abidin Raja Hussin [1997] 3 CLJ 854, said of an aggrieved person at p. 868:

The Code contains no definition on who is an aggrieved person. To my mind, the word aggrieved must be given its ordinary meaning. To be aggrieved means one is dissatisfied with or adversely affected by a wrongful act of someone. An aggrieved person is therefore a person whose legal right or interest is adversely affected by the wrongful act or conduct of another person or body. The category of aggrieved persons is never closed.

Cases On Registrars Caveat

There are relatively a few cases reported in the law reports on the Registrars caveat. One of the leading cases under s. 418 against the decision of the Registrar to enter his caveat under the NLC is Temenggong Securities Ltd and Tumbuk Estate Sdn Bhd v. Registrar of Titles, Johore which was commenced by originating motion No. 4 of 1973 by the two applicants in the Muar High Court as persons aggrieved. In this High Court case (unreported), the Malaysian Inland Revenue Department requested the Registrar of Titles to enter a Registrars caveat over certain lands sold by the registered proprietor Li-Ta Company (Pte) Ltd as vendor to the first applicant Temenggong Securities Ltd which had paid the full purchase, and had received the transfers and the issue documents of title and possession of the lands on completion of the

L A W

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xv

transaction on 22 September 1972. The Registrars caveat was entered on 11 October 1972 to protect the interest of the Federal Government for recovery of income tax due from the vendor. The Registrar rejected the transfers and other documents presented, after adjudication for stamp duty payment, for registration on 14 December 1972, and informed on 15 March 1973 the applicants that a Registrars caveat had been entered. The applicants lost their case before Pawan Ahmad bin Ibrahim Rashid J, who erroneously held in his judgment (reproduced from p. 32 of the appeal record in Privy Council Appeal No. 38 of 1975):

I am of the view that the legislature clearly had in view the protection of the interests of the Federation or the State authority and because of this, gave the Registrar specific powers under Section 320 to enter a caveat in respect of any land when he deemed it necessary or desirable to do so in the protection of such interests. It might also be mentioned here that the word interests is plural in number and in my view it can be interpreted to include interests other than registrable interests, whereas in Section 323 the word interest is singular in number and includes only a registrable interest. For this reason I am of the opinion that interests such as vested or contingent are also within the purview of Section 320 of the National Land Code, as far as it pertains to the Federation or the State authority.

In The Federal Court

The applicants appealed to the Federal Court in Temenggong Securities Ltd & Anor v. Registrar of Titles, Johore & Ors [1974] 1 LNS 175; [1974] 2 MLJ 45. In allowing the appeal and reversing the decision of the learned High Court Judge, Ong Hock Sim FJ, in delivering the unanimous judgment of the Federal Court, said at p. 47:

We are of the view that the vendor, having parted with their interest in the lands to the appellants, are bare trustees and have no interest in the land over which a valid caveat can be lodged. Respondents counsel tried to make much of clause 1 of the Agreement of August 30, 1972 that the vendor shall sell and purchaser shall purchase and that therefore no rights passed as the agreement was non-registrable and a non-statutory instrument capable of passing title to the appellants. He glossed over the fact that the vendors had done everything that was required of them to transfer the title and had thereby constituted themselves bare trustees for the appellants and had no other or further interest in the lands.

L A W

xvi

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

In The Privy Council The Registrar of Titles appealed to the Privy Council against the judgment of the Federal Court. The Privy Council dismissed with costs the appeal by the Registrar in Registrar of Titles, Johore v. Temenggong Securities Ltd [1976] 1 LNS 135; [1976] 2 MLJ 44, [1976] 2 WLR 951, [1977] AC 302. In delivering the judgment of the Privy Council, Lord Diplock said of the Registrars caveat at [1976] 2 MLJ 44, at p. 46:

A registrars caveat has substantially the same prohibitory effect as a private caveat expressed to bind the land itself. It is entered by the registrar of his own motion by endorsing the register document of title to the land with the words Registrars Caveat Entered and the time of entry. In one respect its effect is more severe than that of a private caveat: it operates to prohibit the registration, endorsement or entry of instruments, claims to exempt tenancies and lien-holders caveats which were received at the registry before the time of entry of the registrars caveat if they have not been already entered on the register document of title by then. On the other hand the registrar may waive the prohibition in any case where he is satisfied that this would not be inconsistent with the purpose for which the caveat was entered.

Note the learned Law Lords concluding opinion on s. 320(1)(b) (ii) that the Registrar was not entitled to enter a Registrars for unpaid income tax at p. 48:

The characteristic which is common to the three categories of persons specified in sub-paragraph (ii) is that they are handicapped in their ability to search for themselves the entries in the register relating to land in which they are entitled to an interest or to learn of any threatened dealing with the land which might have the effect of overriding their interest and which accordingly would justify an application for a private caveat. So far as these three categories of persons are concerned, in their Lordships view the clear intention of Parliament in including paragraph (b) in s. 320(1) was to enable the registrar of his own initiative to do for persons in any of these categories what could have been done upon an application made by them for private caveat; and to do no more than that. As a public servant appointed by the state, the registrar is an appropriate officer himself to do on behalf of the Federation and the State Authority what in the case of private individuals he could be required to do by a formal application on

L A W

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xvii

their part for the entry of a private caveat. Their Lordship accordingly conclude that the interests which the registrar is empowered to protect under s. 320(1)(b) are confined to interests in the land that are recognised by the Code as being either registrable or otherwise entitled to protection. An unsecured creditor of the proprietor of land has no such interest in the land. Even if no contract of sale by Li-Ta to Temenggong had been in existence at the time, the registrar would not have been empowered by s. 320(1) to enter any registrars caveat in respect of Li-Tas land, upon the information which their Lordship have assumed was available to him. Upon this ground they would dismiss the appeal.

If the Registrar were entitled to enter the Registrars caveat for unpaid income tax, then many individual and corporate tax payers will run the risk of having their lands caveated by the Registrar. Amendment To s. 320 After the decision in the Privy Council was made against the Registrar of Titles, amendment was made to s. 320 of the NLC by the insertion of (ba) to s. 320(1) by Act A444, gazetted on 15 February 1979 (see my article Registrars Caveat Amended [1980] 1 MLJ, vii, and judgment of Mohamed Dzaiddin J (as he then was) in Lim Ah Hun v. Pendaftar Hakmilik Tanah, Pulau Pinang & Anor [1990] 2 CLJ 640; [1990] 2 CLJ (Rep) 369, cancelling the Registrars caveat). The amendment to s. 320 does not appear to assist the Government in tax collection where the land in question has been charged. But the situation may well be different where the tax payers land is not charged and is free from encumbrances. In Oversea-Chinese Banking Corp Ltd v. Pendaftar Hakmilik, Negeri Kedah [1990] 2 CLJ 275; [1990] 2 CLJ (Rep) 594, KC Vohrah J (as he then was) did not support the entry of the Registrars caveat. He said at p. 598:

L A W

It seems to me that once there is a charge registered in respect of the land, a Registrars caveat is incapable of being entered in respect of the land for it cannot possibly appear necessary or desirable to him for securing that the land will be available to satisfy the whole or any part of the debt due the Federation since the caveat will not transform an unsecured debt into a secured debt let alone give the debt a priority over other registered interest in the land; instead the caveat serves to interfere with the legitimate right of the chargee to sell the land under the provision of the code to recoup losses secured by the charge.

xviii

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

In Public Bank Bhd v. Pengarah Tanah & Galian & Anor [1989] 1 LNS 159 referred to earlier, a Registrars caveat was entered also at the request of the Inland Revenue Department. In this case, the plaintiff bank as registered charge applied by letter to the Registrar to remove his caveat but the Registrar rejected the chargees application to cancel the caveat. The proprietors of the land affected, however, had not made the application for cancellation of the caveat under s. 321(3)(b) of the NLC. Mohtar Abdullah JC (as he then was), accepting the submissions of the then Johor State Legal Adviser Zulkefli bin Ahmad Makinudin (now CJ (Malaya)) for the first defendant, and Senior Federal Counsel Balia Yusof bin Wahi (now JCA) for the second defendant, correctly dismissed the appeal of the plaintiff represented by Tan Kiah Teck on the ground that the appeal was filed out of the three-month statutory period. A lesson to be learned from this case is that whether or not a person or body aggrieved requests the Registrar to cancel his caveat, it is always prudent to file the appeal in the High Court within the threemonth period. Private Caveat Sections 322 to 329 of the NLC make provisions relating to private caveats. Private caveats are practically entered every day throughout Peninsular Malaysia in transactions involving sales and purchases of land of various categories of uses (including industrial land, houses and strata title units like condominiums), and loan transactions to finance the purchases of various immovable property. A basic working knowledge of private caveats is therefore important to the practice of advocates and solicitors in advising or acting for their clients whether in conveyancing or litigation.

L A W

Nature And Effect Section 322 of the NLC as amended now reads as follows:

322 Nature and effect of private caveats. (1) A caveat under this section shall be known as a private caveat, and (a) may be entered by the Registrar on the register document of title to any land at the instance of any of the persons or bodies specified in section 323;

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xix

(b) shall have the effect specific in sub-section (2) or (3), according as it is expressed to bind the land itself or an undivided share in the land or merely a particular interest therein. (2) The effect of any private caveat expressed to bind the land itself or an undivided share in the land shall, subject to subsections (4) and (5), be to prohibit so long as it continues in force the registration, endorsement or entry on the register document of title thereto of (a) any instrument of dealing executed by or on behalf of the proprietor thereof, and any certificate of sale relating thereto; (b) any claim to the benefit of any tenancy exempt from registration granted by the said proprietor; and (c) any lien-holders caveat in respect thereof; Provided that where the claim is in respect of a part of the land the caveat bind the whole land and where the claim is in respect of an undivided share in the land, the caveat binds the whole of undivided share in the land. [Inserted by Act A1104]. (3) The effect of any private caveat expressed to bind a particular interest only shall, subject to sub-sections (4) and (5), be to prohibit the registration, endorsement or entry on the register document of title of (a) any instrument of dealing directly affecting that interest (including any certificate of sale relating thereto); and (b) where that interest is a lease or sub-lease -

L A W

(ii) any lien-holders caveat in respect thereof.

(i) any claim to the benefit of any tenancy exempt from registration granted directly thereout, and

(4) A private caveat shall not prohibit the registration endorsement or entry of any instrument, claim or lienholders caveat where the instrument was presented, or the application for endorsement or entry received, prior to the time from which the private caveat takes effect.

xx

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

(5) A private caveat shall not prohibit the registration or endorsement of any instrument or claim where (a) the instrument was presented or the application for endorsement made by the person or body at whose instance the caveat was entered; or (b) the said instrument or application was accompanied by the consent in writing of that person or body to its registration or, as the case may be, to the making of the endorsement. (5A) No consent of the person or body at whose instance a private caveat has been entered on a part of the land, an undivided share in the land or a particular interest therein is necessary to effect any registration, endorsement or entry of any instrument on the register document of title not affecting the claim relating to the part of the land, undivided share in the land or interest therein. [Inserted by Act A1104].

Cases On Purpose And Effects Of Caveats As early as 1917, in the well-known Australian High Court case of Butler v. Fairclough [1917] 23 CLR 78 Griffith CJ was considering the nature and effect of a caveat. The learned Chief Justice said at p. 84:

The effect of these provisions is not to enlarge or add to the existing proprietary rights of the caveator upon which the caveat is founded, but to protect those rights, if he has any.

In 1976 in Registrar of Titles, Johore v. Temenggong Securities Ltd [1976] 1 LNS 135; [1976] 2 MLJ 44 Lord Diplock said at p. 46 (also at [1976] 2 WLR 951, and [1977] AC 302 at p. 308) on the purpose of a private caveat:

The purpose of a private caveat is to preserve the status quo pending the taking of timeous steps by the applicant to enforce his claim to an interest in the land by proceedings in the courts.

L A W

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xxi

In 1979 in an appeal from the Federal Court of Malaysia, the Privy Council in the often-quoted case of Eng Mee Yong & Ors v. Letchumanan [1979] 1 LNS 18; [1979] 2 MLJ 212, Lord Diplock has the opportunity to make useful observations on private caveats under the NLC at p. 214:

The system of private caveats is substituted for the equitable doctrine of notice in English land law. By s. 322(2) the effect of entry of a caveat expressed to bind the land itself is to prevent any registered disposition of the land except with the caveators consent until the caveat is removed By s. 324 the Registrar is required to act in an administrative capacity only; he is not concerned with the validity of the claim on which the caveat purports to be based. The caveat under the Torrens System has often been likened to a statutory injunction of an interlocutory nature restraining the caveatee from dealing with the land pending the determination by the court of the caveators claim to title to the land, in an ordinary action brought by the caveator against the caveatee for that purpose. Their Lordship accept this as an apt analogy with its corollary that caveats are available, in appropriate cases, for the interim protection of rights to title to land or registrable interests in land that are alleged by the caveator but not yet proved.

Caveatable Interest

It is important to note that not everyone is entitled to enter a private caveat and that before a person applies in Form 19B of the NLC for the entry of a private caveat, he must make sure that he has a caveatable interest in the land concerned under s. 323(1) of the NLC. In AKB Airconditioning & Electrical Sdn Bhd v. Hew Foo Onn & Anor [2002] 1 LNS 26; [2002] 5 MLJ 391, Abdul Malik Ishak J (as he then was) succinctly stated the law at p. 401 as follows:

It is wrong to presume that every person has a right to enter a private caveat. Section 323 of the NLC envisages the situation that only a person having a caveatable interest may enter a private caveat. It is essential that a person who enters a private caveat must claim title to the land or any registrable interest in the land or any right to such title or interest to the land. Under s. 324(1) of the NLC, it is not the duty nor the function of the registrar to enquire into whether the application for the entry of a private caveat is validly made. It is the domain of the High Court to

L A W

xxii

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

exercise its judicial function to adjudicate on the validity of the entry of the private caveat. According to the long line of authorities, the registrars duty in respect of an application for entry of a private caveat is purely administrative or ministerial.

In the Court of Appeal case of Luggage Distributors (M) Sdn Bhd v. Tan Hor Teng @ Tan Tien Chi & Anor [1995] 3 CLJ 520, Gopal Sri Ram JCA had paraphrased s. 323(1)(a) at p. 547 as follows:

To paraphrase sec. 323(1) (a) of the Code, a private caveat may be entered at the instance of any person or body who claim either: (1) the title to land; or (2) any registrable interest in Land. The parameters of caveatability under s. 323(1) (a) are therefore circumscribed by these words: title and registrable interest. It is only one who makes a claim to either of these in land may enter a private caveat.

In the case of Megapillars Sdn Bhd v. Loke Kwok Four [1996] 4 CLJ 82, Kang Hwee Gee J (as he then was) made the following observations on caveatable interest at p. 90:

It is trite law that a caveator must have a caveatable interest in the land and not merely a pecuniary interest in it before he can lodge a caveat under s. 323 of the National Land Code (Registrar of Titles, Johore v. Temenggong Securities Ltd. [1976] 2 MLJ 44). Thus, in Wong Kuan Tan v. Gambut Development Sdn. Bhd. [1984] 2 MLJ 113, a contractual right to an unpaid balance of the purchase price of the sale of land was held by the Federal Court to be incapable of creating a caveatable interest in land which would entitle the caveator to continue to maintain his caveat. Likewise, in the Supreme Court case of Abdul Rahim v. Vallapai Shaik (a case cited by defendants Counsel), an agreement entered into by the three beneficiaries of the estate of the deceased to sell land which was conditional upon consent being given by the four other beneficiaries and upon the purchaser making the monthly instalments towards the discharge of charge of that land to the bank, was held to confer no caveatable interest on the purchaser.

L A W

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xxiii

Further, where that interest is claimed through a contract for the sale of land, the contract must be enforceable by the caveator and negotiations for a contract no matter how advanced is not capable of creating a caveatable interest in his favour ( Ayer Hitam Tin Dredging Malaysia Bhd v. Y.C. Chin Enterprises Sdn. Bhd. [1994] 3 CLJ 133). The point is well illustrated by the following passage in the Court of Appeal case of Murugappa Chettiar Lakshmanan (Wasi Tunggal Harta Pesaka M.R.L. Murugappa Chettiar, Simati) v. Lee Teck Mook [1995] 2 CLJ 545 at p. 551:

Until and unless a purchaser has an enforceable contract for the sale of land, he can lay no claim to the title to registered land. A fortiori, he has no interest that is capable of protection by the entry of a caveat (per Gopal Sri Ram JCA).

No Caveatable Interest The courts have held that in the following cases the following persons have no caveatable interest. A creditor or judgment creditor of a proprietor of land is not entitled in law to enter a private caveat against the debtors land to secure or realize a debt for the reason that a mere debt, whether under a judgment or not, is not an interest relating to land. A judgment creditor for a monetary debt may take out execution proceedings against the land of the judgment debtor made by way of a prohibitory order under ss. 334 to 339 of the NLC. In Hiap Yiak Trading Sdn Bhd & Ors v. Gim Hin & Co (M) Sdn Bhd [1989] 1 LNS 32 in which the applicants had paid the full purchase price, the private caveat and prohibitory order were removed because they were not interested in the land as they sought only the refund of the deposit and other expenses. In United Malayan Banking Corp Bhd v. Development & Commercial Bank Ltd [1983] 1 CLJ 82; [1983] CLJ (Rep) 421, the Federal Court held that failure to obtain the consent of the first chargee meant that the appellant bank did not have a caveatable interest in the land. The claimant for a mere chose in action arising out of or incidental to a contract for the sale of land is not entitled to enter a private caveat (see Mawar Biru Sdn Bhd v. Lim Kai Chew And Another Application [1990] 1 LNS 123). The caveators appeals to the then Supreme Court were dismissed on 11 June 1991. A tenant for a tenancy for two years with an option for having it renewed for a further two years has no caveatable interest (see Luggage Distributors (M) Sdn Bhd v. Tan Hor Teng @ Tan Tien Chi & Anor [1995] 3 CLJ 520). A

L A W

xxiv

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

purchaser of shares in a company has also no caveatable interest in the land of the company (see Pembangunan Wang Kita Sdn Bhd v. Fry-Fry Marketing Services Sdn Bhd [1998] 2 CLJ Supp 96). A shareholder or officer of a company does not have a caveatable interest in the land sold by his company, as was held in Hew Sook Ying v. Hiw Tin Hee [1992] 3 CLJ 1325; [1992] 1 CLJ (Rep) 120 where Mohd Azmi SCJ said at p. 127:

Further, once the company has executed the instrument of transfer in Form 14A in favour of the purchaser, and handed over the original document of title, the managing director either as an officer of the company or in his personal capacity as a shareholder has no fiduciary duty to challenge the conduct of the company by means of private caveat for the alleged purpose of protecting his own interest or the interest of other shareholders.

In my article entitled Private Caveats, Entry, Extension and Removal published in INSAF, the Journal of the Malaysian Bar, (2006) XXXV No. 2, at p. 87, I wrote:

Having determined that the applicant has a caveatable interest under s. 323(1) of the Code in the land in question, you may then apply for the entry of a private caveat in Form 19B in accordance with the provisions of s. 323 of the Code. The following points and procedure should be observed: (a) Apply in the prescribed Form 19B, which may be printed or typed. The relevant particulars must be properly completed. (b) Under para 2 of Form 19B, state concisely the grounds of the claim to the title in the land or undivided share in the land or interest therein, and/or further as stated in the supporting statutory declaration. It is important to bear in mind that what the applicant affirms in the statutory declaration may be used against him in any subsequent litigation concerning the caveat. Although the statutory declaration can be affirmed by the advocate and solicitor under para 3(b) of Form 19B, it is advisable for his client to affirm it in order to maintain detachedness on the part of the solicitor. (c) Note the supplementary provisions as to forms and procedure are provided under the Tenth Schedule of the Code. Under para 11 thereof, the signatures of the caveat applicant and the attesting witness should be in permanent black or blue-black ink. Signatures in ball point pens are not accepted. Roller point pens are accepted. It is important to know the practice of the relevant land registry or land office.

L A W

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xxv

(d) Form 19B, if executed by a natural person, i.e. the caveator or his attorney or the attorney of a company (typically an attorney of a chargee bank whose power of attorney has been registered with the Registrar of Titles or the Land Administrator) requires attestation by one of the qualified person stipulated in the Fifth Schedule, typically an advocate and solicitor in Peninsular Malaysia. Execution of Form 19B by a limited company under its common seal requires no attestation but Form 19B must be accompanied by such documents as the Memorandum and Articles of Association of the Company, its board resolution, its Form 49 and the supporting statutory declaration which may be affirmed by one of its directors. If Form 19B is executed by a director on behalf of the company (see Mahadevan & Anor v. Patel [1975] 2 MLJ 207), the signature of the director requires attestation. (e) Identify the share of the land in column 4 of the Schedule in Form 13A. In most cases, the caveat is to bind the whole (semua in Malay) of the land itself. Sometimes, where the land is registered in the name of more than one proprietor, an undivided share like 1/2 or 1/3, caveat only the undivided share of the particular proprietor involved. (f) Caveating a part of land or a strata title unit requires greater care. Note the new proviso to s. 322(2) of the NLC stating that where the claim is in respect of a part of the land the caveat binds the whole land. Note also para 3(c) of Form 19B. In my experience, I would, while indicating the whole land, state and limit the caveat to the particular interest claimed in column 4 of the Schedule like limited to the X sq. ft. or limited to the Y unit (in Malay: Semua. Terhad kepada X kaki persegi or Terhad kepada unit Y). The details of the interest claimed in the agreement or a plan of the land affected can be disclosed in the supporting statutory declaration. Note the provisions in the new s. 322(5A) on the question concerning the consent of the caveator. (See the judgment of Suffian LP in the Federal Court case of N. Vengedaselam v. Mahadevan & Anor. [1976] 2 MLJ 161.)

L A W

(g) Pay the appropriate registration fees, which vary from state to state [and time to time]. For example, (i) under the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur Land Rules 1995, the fee for entry of a private caveat in Form 19B is RM300 per title (item 32),

xxvi

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

(ii) under the Federal Territory of Putrajaya Land Rules 2002 (P.U. (A) 76), the fee for entry of a private caveat under item 29 of Schedule 4 is RM50 per title. (iii) under the Selangor Land Rules 2003, the fee is RM300 per title (item 40), and (iv) under the Johore Land (Amendment) Rules 2002, item 15 (XXVI), the registration fee is RM150 per title. However, where Form 19B contains more than one title the fee for each title after the first title is RM30 per title. As for the solicitors legal costs relating to caveats, these are slightly increased and are provided under the Fifth Schedule to the Solicitors Remuneration Order 2005, which came into operation on 1 January 2006. The remuneration for a solicitor for entry of a caveat is now RM200 for the first title and RM50 for each subsequent title. For the withdrawal of a caveat, it is RM150 for the first title and RM50 for each subsequent title. Please observe the no discount rule of the Bar Council.

Caveator Bound By His Grounds A caveator should remind himself that he is bound by what he has stated in his grounds for the entry of his private caveat, as these grounds may later be used against him. In Teck Hong Development Sdn Bhd v. Toh Chin Ann [2008] 4 CLJ 756, Gopal Sri Ram JCA (as he then was) said at p. 761 in delivering the judgment of the Court of Appeal:

The caveat is not grounded on the fact that the order for sale is invalid. In Luggage Distributors Sdn Bhd v. Tan Hor Teng [1995] 2 CLJ 713, this court held that a caveator is bound by the grounds he or she sets out in the application in Form 19B for the entry of the caveat. It was also held if the grounds disclosed in Form 19B do not disclose a caveatable interest, then cadit quaestio.

L A W

Further Caveat After Lapsing The statutory lifespan of a private caveat under s. 328(1) is six years, unless extended by order of the High Court, or earlier withdrawn or removed. Section 328(1) reads:

A private caveat shall, if not sooner withdrawn under s. 325 or lapsing pursuant to sub-section (1B) of s. 326 or removed by the Registrar pursuant to an order of the Court under s. 327, lapse at the expiry of six years from the time from which it took effect,

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xxvii

and the entry thereof may be cancelled accordingly by the Registrar, either of his own motion or on an application in that behalf by any interested person or body.

Can a further caveat be entered after lapsing? I am inclined to think that the caveator should be allowed to enter a further caveat to protect the same interest based on the same ground, provided his claim or interest is still subsisting and not barred by limitation. (See Wong: Restraints of Dealings in Land. in The Centenary of the Torrens System in Malaysia. (Malayan Law Journal (1989), and Teo: Further Thoughts on Second Caveats [1990] 3 MLJ cxvi.) That question was answered in the positive by LC Vohrah J in Thevathason s/o Pakianathan v. Kwong Joon [1990] 2 CLJ 308; [1990] 3 CLJ (Rep) 248, where he said at p. 251:

I did not think that both these authorities which were cited in Damodaran v. Vasudeva to support the proposition that a second caveat may not be entered at the instance of the same applicant in respect of the same land and precisely the same grounds under the National Land Code in any way prohibited the entering of fresh caveat even after the lapse of the first caveat based on a different ground or even on the same grounds if it is for the bona fide purpose of protecting the caveators interest in respect of the same land. It was my judgment that if a contrary view was taken there would be no way in which caveator like the defendant who had already filed his action could protect his existing interest pending resolution of his dispute by the Court. It seemed to me that s. 328(1) merely provided for the normal longevity of a private caveat and envisaged a time frame within which the caveator should take action to realize his existing interest; it did not exist to extinguish his right to further protection of that interest if he had taken positive action, as was done in the present case, to realize it.

L A W

Failure To Enter Caveat As a rule of prudence, a solicitor should advise the client to enter the private caveat immediately after execution of the sale and purchase agreement. However, failure to enter a private caveat or enter one later in time does not necessarily mean that a purchaser of land or a chargee will lose his equitable interest in the land, which eventually will be converted to a legal interest upon registration of the transfer or charge. In Haroon bin Guriaman v.

xxviii

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

Nik Mah binte Nik Mat & Another [1951] 1 LNS 24, Briggs J held that the caveat of Haroon cannot prevail over the prior equities of Nik Mah. In the Temenggong Securities case, I was involved as a solicitor in the sale and purchase of the relevant lands in the early 1970s, just a few years after the NLC had come into force. At that time I did not know of the Registrars caveat. The purchaser had paid the full purchase price and had received the transfers and other relevant documents. The purchaser and its nominee did not enter any private caveat. The Inland Revenue Department had caused a Registrars caveat to be entered against the lands. The High Court refused to remove the caveat. On appeal, the Registrars caveat was ordered to be removed by the Federal Court, which was affirmed by the Privy Council. Much to my relief, Temenggongs nominee eventually became the registered proprietor of the land free from encumbrances. In the Court of Appeal case of Tsoi Ping Kwan v. Medan Juta Sdn Bhd & Ors [1996] 4 CLJ 553, the second respondent company did not appear to have entered a private caveat and its knowledge of the appellants caveats did not affect its interest adversely. Gopal Sri Ram JCA (as he then was), finding the balance of convenience favours the second respondent, said at p. 567:

In our judgment, it would be wholly unjust and inequitable to permit the appellant to contend that the caveats should remain as against the second respondent which, in the light of the circumstances adumbrated by Raja Aziz in the course of his address to us, is entirely innocent.

The Federal Court applied the Australian case of Butler v. Fairclough in United Malayan Banking Corporation Bhd v. Goh Tuan Laye & Ors. [1975] 1 LNS 187 in which, in the absence of caveats and registrations, the Federal Court found in favour of the appellant bank which had possession of the documents of title. In Ng Kheng Yeow v. Chiah Ah Foo & Ors [1987] 2 CLJ 108; [1987] CLJ (Rep) 254, the Supreme Court held that the entry of a private caveat by one party does not necessarily mean that he has better priority against another who has not as yet lodged one. The court found in favour of the 4th respondent although

L A W

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xxix

his caveat was later in time than that of the appellant. In delivering the judgment of the court, Lee Hun Hoe CJ (Borneo) said:

The submission of the 4th respondent that he has better equity is well founded. He entered into the sale agreement with the vendor first. He had paid the full purchase price. The vendors had executed the Memorandum of Transfer in favour. Also, most importantly the title deed is in his possession. He had become the beneficial owner. The only thing against him is that he entered the caveat later than the appellant. However, we are satisfied that on the facts he has the better equity.

In Bank of Tokyo Ltd v. Mohd Zaini Arshad & Anor [1991] 2 CLJ 989; [1991] 2 CLJ (Rep) 341, Lim Beng Choon J held that the plaintiff bank, as financier and absolute assignee, had the better equity. The learned judge said at p. 349:

On principle and authority I cannot, therefore, accept the proposition that just because the intervenor had caveated the land in question in 1984 the priority of the plaintiff should be reduced and be subservient to the equity of the intervenor.

Withdrawal Of Private Caveats Withdrawal of private caveats poses no difficulty under s. 325 of the NLC. A caveator may withdraw his caveat at any time by presenting to the Registry or Land Office a notice in Form 19G duly completed and accompanied by the prescribed fees. Removal Of Private Caveats

L A W

There are two ways of removing a private caveat under the NLC by the caveatee, ie, the person or body whose land or interest is bound by a caveat. One way is by application under s. 326 in Form 19H to the Registrar or the Land Administrator as the case may be and paying the prescribed fee. A registered proprietor or registered chargee under the NLC may proceed to remove the caveat under s. 326 by virtue of his registered interest. The other way is by application to the High Court as an aggrieved person under s. 327(1) of the NLC to cover any one whose land or interest therein is adversely affected by the caveat. See the wellconsidered judgment of Abdul Malik Ishak J (as he then was) in

xxx

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

AKB Airconditioning & Electrical Sdn Bhd v. Hew Foo Onn & Anor [2002] 1 LNS 26; [2002] 5 MLJ 391 at 403 on an aggrieved person, where he said:

If you are acting for the caveatee, you will have to decide and advise clients as to which one of the two ways is the more expedient in the circumstances of the case, bearing in mind (a) the workload and the hearing time of the High Court concerned and (b) the duration for removal by the Registrar or Land Administrator is two months under s. 326(1B) after service, when the burden is on the caveator to obtain an order for extension of his caveat from the High Court.

Removal Under s. 326 Removal, in my experience, it is often faster for the registered proprietor to remove the private caveat through the Registrar under s. 326. As the applicant is the registered proprietor of the land, the burden shifts to the caveator to show that his caveat should not be removed. See Eng Mee Yong & Ors v. Letchumanan [1979] 1 LNS 18, PC, Hew Sook Ying v. Hiw Tee Hee [1992] 2 MLJ 189, at 194, SC and Pembangunan Wang Kita Sdn. Bhd. v. Fry-Fry Marketing Services Sdn. Bhd. [1998] 5 MLJ 709 at 716. A recent case in point of removal under s. 326 is Urethane Systems Sdn Bhd v. Quek Yak Kang [2006] 6 CLJ 81. In this case, the caveator failed to get an order to extend its private caveat before Helmy J (as he then was) and the caveat was accordingly removed by the Land Administrator. Removal Under s. 327

L A W

Section 327 of the NLC provides for any person or body aggrieved by the existence of a private caveat to apply to the High Court for an order for its removal. In normal circumstances the caveator must be served with the application for removal. The procedure for removal of a private caveat is regulated by the rules relating to civil procedure, now the Rules of Court 2012 which came into force on 1 August 2012, repealing the Rules of the High Court 1980 which repealed the Rules of the Supreme Court 1957.

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xxxi

In 1991 in Kumpulan Sua Betong Sdn Bhd v. Dataran Segar Sdn Bhd [1992] 1 CLJ 20; [1992] 1 CLJ (Rep) 150, the Federal Court by a 2:1 majority held that there were serious questions to be tried and that the balance of convenience was in favour of allowing the caveat to remain. Jemuri Serjan CJ (Borneo) said for the majority at p. 158:

The crucial issue for our determination is whether in order to support the caveat to remain in force, the appellant has succeeded in satisfying us that it is a body at whose instance a caveat may be entered under s. 323(1)(a). This seems to be the logical approach to the issue. Be that as it may, the approach that is common in Malaysia before the case of Eng Mee Yong & Ors v. Letchumanan [1979] 1 LNS 18 was decided by the Privy Council, is to ask the question whether the caveator has a caveatable interest which terms are not defined in the National Land Code 1965, by applying to him para. (a) of sub-s (1) of s. 323 of the Code. The relevant question which the court should address itself to is: Is the appellant a person claiming title to, or registrable interest in any alienated land, or any right to such title or interest? If it is not, that ends the matter and the caveat cannot be allowed to remain. The factual matrix of the claim to be a person or body within the purview of para (a) of the subsection must be minutely considered by evidence to establish that the claim is not frivolous or vexatious. This approach can be best illustrated by reference to the judgments of all the three Federal Court judges in the Federal Court case of Macon Engineers Sdn Bhd v. Goh Hooi Yin [1976] 1 LNS 67 where reference was made to s. 323(1)(a) of the Code in the course of the judgments. At p. 54 Gill CJ (Malaya), in dealing with s. 323(1)(a) of the NLC, says: As regards the first questions, s. 323(1)(a) of the National Land Code 1965 provides that a private caveat may be entered at the instance of any person or body claiming title to, or any registrable interest in, any alienated land or may right to such title or interest. It would seem clear that the respondent cannot claim title to or any registrable interest in the property in question merely on the strength of the sale agreement which is a nonstatutory and non-registrable instrument, but it cannot be denied that has a right under that agreement to such title or interest by bringing an action for specific performance of the agreement, which in fact he has already done.

L A W

xxxii

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

In the Court of Appeal case of Luggage Distributors (M) Sdn Bhd v. Tan Hor Teng @ Tan Tien Chi & Anor [1995] 3 CLJ 520, the court held that as exempted tenants the respondents private caveats were not available to them. In a claim to a caveatable interest, Gopal Sri Ram JCA (as he then was) at p. 535 stated there are three stages involved. The first stage is the examination of the grounds expressed in the application for the caveat. If it appears that the grounds stated therein are insufficient in law to support a caveat, then cadit quaestio , and the caveat must be removed without the necessity of going any further. In the second stage, the caveator must show his claim discloses a serious question meriting a trial. The third stage is to determine where the balance of convenience or justice lies. The caveator must satisfy the three stages before his caveat is permitted to remain. In 1996 in Kho Ah Soon v. Duniaga Sdn Bhd [1996] 2 CLJ 218, the Federal Court ordered the caveat which was removed by the High Court to be restored as there are indeed serious questions for trial. On the onus of the caveator, Peh Swee Chin FCJ, in delivering the judgment of the court, said at p. 223:

It is settled that in a matter of removal of a caveat as between a caveator and caveatee, as in the instance appeal, the onus is on the caveator to satisfy the court that his evidence does raise a serious question to be tried as regards his claim to an interest in the land in question, and having done his claim so he must show that, on a balance of convenience, it would be better to maintain the status quo until the trial of the action by preventing the caveatee from disposing of his land, as laid down by Lord Diplock in Eng Mee Yong & Ors. v. Letchumanan [1979] 2 MLJ 212, and by analogy indirectly to American Cyanamid Co v. Ethicon [1975] AC 396 as indicated by Lord Diplock, the serious question for trial referred to above could mean a question not being vexatious or frivolous.

L A W

In a pending suit, where the caveator and the caveatee are parties, the removal application was previously made by summonsin-chambers (Woo Yok Wan v. Loo Pek Chee [1974] 1 LNS 192), which should now be made by an application under the Rules of Court 2012.

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xxxiii

For an application to remove a private caveat made by originating summons, see Chi Liung & Son Sdn Bhd v. Chong Fah & Sons Sdn Bhd & Anor [1974] 1 LNS 21; Chiew Sze Sun v. Muthiah Chettiar [1982] CLJ 39; [1982] CLJ (Rep) 423; and Bank Utama (Malaysia) Bhd v. Periamma Vellasamy [2003] 1 CLJ 142 where Azmel J (as he then was) refused to remove the caveat. As the originating summons is retained by the new Rules of Court 2012, this procedure may, in an appropriate case where there is no serious dispute on facts, be used in removing a private caveat. No Further Caveat On Removal A caveator is prohibited from entering further caveats on like claims after removal by the court or the Registrar, as provided under s. 329(2) of the NLC:

(2) where the Court has ordered the removal of any private caveat under s. 327, or has refused an application under subsection (2) of s. 326 for an extension of time with respect to any such caveat, or where the Registrar has removed any caveat pursuant to sub-section (3) of s. 326, the Registrar shall not entertain any application for the entry of a further caveat in respect of the land or interest in question it is based on the like claim as that on which the former one was based.

Caveating Own Land

The provisions in s. 323(1) or any other section in the NLC is silent on the question whether a registered proprietor can or cannot caveat his own land or his interest therein to block a chargees sale or a dealing affecting his land or interest. In the first local case, the question was answered in the negative by LC Vohrah J when he removed the caveat in Eu Finance Bhd v. Siland Sdn Bhd (M & J Frozen Food Sdn Bhd, Intervenor) [1988] 1 LNS 200, following Richmond J in the case of Re An Application by Haupiri Courts Ltd (No. 2) [1969] NZLR 353, at p. 357:

He must go further and establish some set of circumstances over and above his status as registered proprietor which affirmatively gives rise to a distinct interest in the land. In such circumstances it would seem that the fact that he is the registered proprietor of an estate or interest under the Act may not prevent him lodging a caveat.

L A W

xxxiv

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

In Hiap Yiak Trading Sdn Bhd & Ors v. Hong Soon Seng Sdn Bhd [1990] 1 CLJ 912; [1990] 2 CLJ (Rep) 117, Richard Talalla JC (as he then was) held that the registered proprietor could caveat its own land, and the caveat in question should remain as the nature of the agreements and the compensation issue should be tried. Damages For Wrongful Caveats An intended caveator must first ensure he has a caveatable interest in the land before entering a private caveat, as a caveator is liable to pay compensation for his wrongful caveat under s. 329(1) of the NLC. In Luggage Distributors (M) Sdn Bhd v. Tan Hor Teng @ Tan Tien Chi & Anor [1995] 3 CLJ 520 Gopal Sri Ram JCA (as he then was) gave the following caution at p. 537:

It is a serious matter to caveat a persons property, and unless a case is properly made out, caveat ought not to be permitted to remain on the register a moment longer than is absolutely necessary.

In the Court of Appeal case of Trans-Summit Sdn Bhd v. Chun Nyook Lin (P) [1996] 3 CLJ 502 Siti Norma Yaakob JCA (as she then was), with whom Shaik Daud JCA and Abu Mansor JCA concurred, in ordering payment of damages, said at p. 506:

On that conclusion, we allow this appeal with costs here and below and order that the deposit be refunded to the appellant. Consequentially, there will also be an order to assess damages by the Registrar of the High Court, Melaka, to be paid by the respondent to the appellant under s. 329(1) of the National Land Code 1965. The private caveat Jilid 75 Folio 99 entered by the respondent against Lot 1915 is to be removed forthwith and ex parte order for extension of the caveat is set aside.

L A W

In Pembangunan Wang Kita Sdn Bhd v. Fry-Fry Marketing Services Sdn Bhd [1998] 2 CLJ Supp 96 Low Hop Bing J (as he then was) ordered removal of the caveat and damages to be paid by the wrongful caveator. The learned judge said at p. 106:

By reason of above, I hold that the defendants entry of the private caveat is wrongful as the defendant had not disclosed a caveatable interest in its application (Form 19B) under s. 323(1) of the National Land Code. Hence the defendant is unable to cross the first hurdle. I order that the private caveat be hereby

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xxxv

removed forthwith, without the necessity of going further. I also make a consequential order that damages be awarded to the plaintiff, to be assessed by the Registrar of this Court. Costs to be taxed and paid by the defendant to the plaintiff.

Burden To Prove Damages To recover damages, the burden of proving loss or damage rests on the caveatee, ie, the person or body whose land or interest is bound by the private caveat. In practice, the task of proving loss or damage suffered is not always easy. For example, in Mawar Biru Sdn Bhd v. Lim Kai Chew [1992] 1 LNS 22, the defendant land proprietor did not recover any damages as he had failed to prove any loss for the wrongful entry of the private caveat by the plaintiff purchaser. In Plenitude Holdings Sdn Bhd v. Tan Sri Khoo Teck Puat & Anor [1994] 2 CLJ 796, a case concerning wrongful termination of contract for purchase of land, the High Court had awarded a total sum of about RM16 million in damages. On appeal, in Tan Sri Khoo Teck Puat & Anor v. Plenitude Holdings Sdn Bhd [1995] 1 CLJ 15, the Federal Court set aside the judgment of PS Gill J (as he then was) and reduced the huge damages of some RM16 million to a mere RM10 as nominal damages mainly because the land had appreciated in value. In the course of his judgment Edgar Joseph Jr. FCJ said at p. 31:

At the end of the day, the purchaser got the land worth approximately RM120,000,000, for which they had paid only RM47,939,958.

No Extension If Caveat Cancelled

L A W

In Manian Kandasamy v. Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Raub & Anor [2011] 7 CLJ 583, the Court of Appeal refused to extend the caveat which had been cancelled by the Land Administrator. Zaleha Zahari JCA, in delivering the judgment of the Court of Appeal, said at p. 591:

[15] The popular meaning attributed to the word extend in s. 326(2) of the Code is that it enlarges or gives further duration to any existing right rather than re-vests an expired right. We are in agreement with the judicial commissioner that the courts power to extend a caveat under s. 326(2) of the Code was only exercisable where a caveat is still alive and was no longer exercisable after a caveat had been cancelled.

xxxvi

Current Law Journal

[2013] 1 CLJ

[16] On the facts of this case the Land Administrator had clearly acted within the powers conferred upon him by s. 326(1B) of the Code in removing the appellants 4th private caveat for failure to furnish a court order within the time specified. The judicial commissioner was right in ruling that once a private caveat has been removed, the Code does not give the court power to revive, renew/continue a private caveat which has been cancelled. It is not within the inherent jurisdiction of the court to make orders which go beyond the limit of the powers expressly given to it by statute.

Restoration Of Caveat If a private caveat had been wrongly removed, the court has the power to restore it. In Palaniappa Chettiar v. Letchumanan Chettiar [1981] 1 LNS 83; [1981] 2 MLJ 127, the caveat was removed by the High Court, but on appeal the Federal Court ordered the caveat to be restored on the ground at p. 129 that:

There are many factors concerning the caveat which were not considered and from the evidence that is available the considerations in favour of maintaining the caveat outweigh any consideration that has so far been shown to be in favour of removing it. We therefore restored it.

In Syed Ibrahim bin Syed Abdul Rahman v. Liew Su Chin (F) [1983] 1 LNS 45; [1984] 1 MLJ 160, the Federal Court refused to restore the caveat of the appellant ordered to be removed by Wan Hamzah J Lee Hun Hoe CJ (Borneo) said at p. 163:

The learned Judge rejected the contention of the appellant that he was entitled in law to have the caveat imposed. He cited the principle laid down in Karuppiah Chettiar v. Subramaniam and followed in Temenggong Securities Ltd. & Anor. v. Registrar of Titles, Johore & Ors. that once the owner by a sale had wholly disposed of the land he divested himself of all interest therein and he becomes thereby merely a bare trustee for the purchaser. There was therefore no interest remaining against which a third partys caveat can lie. He distinguished Macon v. Goh Hooi Yin from the case before him where the respondent had paid the full purchase price. But in Macons case the earlier of the two sales was not completed as only part payment was made. The later sale was completed by full payment of the purchase price. Also, there was a pending suit whereas there is none in the instant case. The question of notice on the part of the appellant becomes important as both sales were unregistered and subject to the approval of the State. On the evidence the learned Judge held that the appellant had notice of the earlier sale.

L A W

[2013] 1 CLJ

Current Law Journal

xxxvii

In affirming the judgment of the High Court, the learned Chief Justice said at p. 164: