Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Role of Ethical Principles in Health Care and The Implications For Ethical Codes

Загружено:

NewfaceОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Role of Ethical Principles in Health Care and The Implications For Ethical Codes

Загружено:

NewfaceАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on March 3, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.

com

Journal of Medical Ethics 1999;25:394-398

The role of ethical principles in health care and the implications for ethical codes

Alexander E Limentani East Kent Health Authority, Dover

Abstract

A common ethical code for everybody involved in health care is desirable, but there are important limitations to the role such a code could play. In order to understand these limitations the approach to ethics using principles and their application to medicine is discussed, and in particular the implications of their being prima facie. The expectation of what an ethical code can do changes depending on how ethical properties in general are understood. The difficulties encountered when ethical values are applied reactively to an objective world can be avoided by seeing them as a more integral part of our understanding of the world. It is concluded that an ethical code can establish important values and describe a common ethical context for health care but is of limited use in solving new and complex ethical problems. (7ournal of Medical Ethics 1999;25:394-398)

Increasingly, many of the moral difficulties in present day health care arise in complex organisations where care is delivered by multidisciplinary clinical teams and influenced by a range of others including managers, boards and governments.' This, among other considerations, has led to the recent call for a code of ethics for all health care professions,5 and follows a number of expressions of concern voiced about the general ethical state of modern medicine.6 In their recent paper, Dr Berwick et al give ample illustration of the diverse and complex moral challenges facing contemporary health care workers, and say they have been encouraged by many to seek a common ethical basis for medical practice.5 Their concern is not an esoteric, specialist one; ethics are a central element in the quality of day to day clinical practice and of enormous importance Keywords: Ethical principles; codes of professional ethics; to the care of patients. Even if codes have only a small influence they are likely to be worthwhile. philosophical ethics; medical ethics Most ethical codes cover a range of topics. They usually include some specific prohibitions, for Introduction Codes of ethics have been a longstanding element example, forbidding euthanasia, or disclosure of in the professional control of the behaviour of secret information, but mainly they describe gendoctors, and indicate a commitment to act with eral attitudes and expected forms of conduct, for integrity in extreme circumstances.' When pa- example: "always to act for the benefit of patients, tients seek medical care they are not entering an deliver bad news with understanding and sympaordinary social relationship; they often feel thy, not sit in moral judgement on any patient, and vulnerable but need to expose and share intimate strive to cure where possible but to comfort and important aspects of their lives. Ethical codes always".7 There are advantages to be gained of conduct offer some tangible protection to both through the adoption of an ethical code and in patients and doctors in these circumstances. The having a common understanding of the ethical Hippocratic Oath is perhaps the best known code nature of medical practice. However, a code may of this kind, and is still administered in some raise unrealistic expectations about its scope and medical schools in the UK and elsewhere,2 despite some caution is required. It is important, in strikuncertainty about its origin and relevance.3 Some ing the right balance, to understand the role that schools use a modernised version of the such a code can play. Ethical codes work in a similar way to ethical Hippocratic Oath or the Prayer of Maimonides, others use the Declaration of Geneva or their own principles, the use of which has received much institutional oath. More recently the General attention in recent years.8 In fact, the principles Medical Council has issued a code, Duties of a approach is now the most generally accepted and Doctor,4 in response to changes in society, the law influential school of thought among medical ethiand medical practice. Traditionally, codes were cists and is highly relevant to the discussion of adopted and oaths taken exclusively by doctors, ethical codes. There are important limitations to reflecting that professional health care was a mat- the principles approach to ethics which apply ter mainly between the doctor and the patient. equally to ethical codes. The theory is most nota-

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on March 3, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

Limentani

395

bly described by Beauchamp and Childress,9 whose exposition is based on four principles: autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, and justice. These principles are seen as one of four tiers in a hierarchy of levels of analysis necessary for moral justification. At the first tier there are particular judgments which are justified at the second level by moral rules. These in turn are justified at the third level by principles, and principles are finally justified at the fourth level by more comprehensive ethical theory. Both the methodology'0 and applicability" of "principlism" have been challenged, as well as defended as a common framework for biomedical ethics.'2 However, even their strongest supporters do not see principles as a complete or self-standing means of establishing ethical practice. Beauchamp and Childress explain that: "Principles guide us to actions, but we still need to assess a situation and formulate an appropriate response, and this assessment and response flow from character and training as much as from principles". Gillon subsequently called this: "the four principles and scope" approach to biomedical ethics."

How principles operate

The expectation is that, in practice, ethical principles and codes will help in thinking through difficult moral issues and in defending subsequent decisions. Proponents of the principles approach claim that they offer a firm grounding for moral judgment that can be used to resolve ethical Principles as 'prima facie' dilemmas and be given in justification of our Principles and the moral rules derived from them actions. For example, doctors are frequently faced are not absolutely binding. Their status is best with the dilemma of deciding what information described as "prima facie", by which Beauchamp should be given to patients about their condition. and Childress'6 mean that a principle is a duty On the one hand, it is important for patients to which is binding on all occasions unless it is in know as much as possible about their disease in conflict with equal or stronger duties. Following order to respond appropriately and take proper Ross,'7 Beauchamp and Childress determine account of its implications in the conduct of their overriding duty by locating "the greatest balance" lives. On the other hand, knowledge of some of right over wrong in any circumstance where aspects of the disease, in particular, complications there is conflict between principles. Although not that may occur but are unlikely, may carry the absolute, they are more than expendable rules of certainty of causing unnecessary distress and thumb: anxiety. This knowledge itself may adversely affect "Because they are always morally relevant, they the patient, detracting from the quality of remainconstitute strong moral reasons for performing ing life, and thereby worsening the prognosis. The the acts in question, although they may not always approach taken using principles is to consider the prevail over other prima facie duties. One's actual requirements of each relevant principle in turn. In is thus determined by the balance of the duty this example they are: the principle of autonomy, respective weights of the competing prima facie requiring relevant information to be given to the duties in the situation. One might say that prima patient who wishes to receive that information; non-maleficence, not causing harm to the patient facie duties count even when they do not win."'8 (either by giving information inappropriately and The strength of principles lies in their being prima causing unnecessary confusion or anxiety or facie, but so does their weakness. Problems begin against the patient's expressed wishes); and to emerge when we ask how we are to moderate beneficence, wishing to promote the patient's between principles when they are in conflict.

general wellbeing to produce the best outcome. The moral process resulting from this method is one of weighing the conflicting thrusts of these different concerns and deciding, on balance, the best course of action. An important benefit of using principles in medical ethics is the drawing together of a common core of issues which loosely unite ethical concerns in health care. Taken in isolation the principles themselves are desirable, attractive and morally sound (similar in character to that of virtues).'4 However, on any particular occasion they may conflict with each other and will not provide a moral conclusion without further judgment. Hence the need to make an assessment of the particular instance in order to decide the extent to which each principle is compatible with the underlying moral, professional, religious, or political theories that individual clinicians may hold. The advocates of the principles approach argue that since the content of general principles is consistent with most theories their application is universal and they transcend most cultural boundaries. They also have the attraction of being consistent with common approaches to the teaching of ethics, in particular lending themselves to the method of casuistry where the desired principles can be woven into a description of the situation as part of a narrative style of teaching. 1

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on March 3, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

396 The role of ethical principles in health care and the implications for ethical codes

There is nothing internal or intrinsic to prima facie principles themselves that determines relative importance. For example, when there is a need for autonomy, how important is non-maleficence? On any particular occasion it may be of overwhelming importance or of little practical relevance. The reference must be, as Beauchamp and Childress correctly say, to a more basic and profound ethical system, but the precise form this should take is not inherent in the principles themselves. Whenever there is a testing moral case principles are silent and something more, beyond principles, is required. However, in practice they are often accepted at face value without direct reference to a more comprehensive ethical theory, and indeed, the danger is that they will obscure ethical theory rather than illuminate it. This difficulty is manifest when principles are used in explanation of moral judgment; they are given no explanation themselves other than their prior designation as prima facie, and cannot give moral theory grounding without circularity."9 In practice, does the prima facie nature of principles matter? Can it not be argued that principles give us a very useful method of reaching moral conclusions and are sufficiently secure in their generality to perform this task without recourse to more basic and specific moral theory? This is the position implied by the presentations of moral theory in many bioethical texts, where different moral systems are given only superficial consideration, often drawing no conclusions as to relative merit. As a result, when particular issues are considered the weight allocated to individual principles is usually presented independently from any direct connection with underlying moral theory. It is not seen as material that the agent has, for example, a deontological approach to duty or is a consequentialist. Whether right or wrong, this lack of connection has little practical relevance when the rights and wrongs of the particular case are obvious and not in dispute. However, it is of critical importance when moral judgments are difficult - as they invariably are in many of the moral dilemmas in medicine, for example, whether a health authority should offer an expensive new treatment for Alzheimer's disease to all patients even though it will mean hardship in other areas, or whether a managed care organisation should selectively enrol well people and avoids vulnerable populations.' In these cases the basis of moral judgments and their justification are called into question, and it is insufficient to take principles as a guide to action without further reference.

Understanding the role of principles in medicine The role principles can play in medicine is influenced by the way ethics in general are conceived. Clinical practice has an intrinsic ethical component, however, in training and in thinking about moral values clinicians frequently find that they share a particular ethical outlook that is consistent with a scientific approach to life,

and which treats ethics as a separate and secondary issue. Reality is seen primarily in terms of the objective, external, physical world, whilst in contrast, values and ethics are seen as a separate, subjective and personal realm.20 In following this division there are two components to making a moral judgment. First there are the morally neutral facts of the case that are either true or false and about which one can have knowledge or belief. Second there are the ethical attitudes one can have in response to the situation which determine the rights and wrongs of the case and guide what action should follow.2' This process of applying principles to a particular situation should ideally be carried out objectively, with the subject deciding in a calm and detached manner the relative importance of each theoretical principle. This relegation of the ethical aspects of the world to a secondary and distinct subject is at the root of the difficulties encountered in subsequent ethical debate. As soon as a division is established one issue tends to overshadow any further ethical consideration: how are the two realms of thought related and how can ethical value be derived from the objective facts? The subsequent discussions range across a spectrum from extreme scepticism that there is any objective connection between facts and values to a rigid reductionism of fixed relationships, usually utilitarian of one kind or another. Some attempts have been made to overcome these problems, by extending, through the work of social science and psychology, the idea of naturalism beyond the natural sciences to include social and emotional aspects of life, in an effort to enable science to provide a more holistic picture of nature. However, the philosophical difficulties persist and cannot be overcome by simply extending the concept of nature to include social and psychological factors. The root of the problem lies more fundamentally with the conception of the relationship between ethics and other aspects of the world. In order to make further progress, instead of moral judgments being considered as separate, non-cognitive aspects of life, they are better understood as being an integral and inseparable part of empirical and factual properties.22 It is a mistake to think of an objective,

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on March 3, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

Limentani

397

physical world which we then evaluate and from which we derive subjective ethical judgments. Values are better thought of as being already present in our conceptions of the world. This is not just a different interpretation but an epistemological claim about the way we understand the world, such that moral aspects are already present in our understanding and not thought of as being added by a further, secondary step. Here, moral properties are part of the world in the same way as any other property, including physical, social and emotional components. For example, cruelty can be recognised in the world and is not separable from the particular circumstances in which it is found. This view opens up the possibility of seeing the world and understanding what is going on in different ways. So, in the previous example of disclosure of information, although not giving information may be considered on the grounds of kindness (not wishing to cause additional anguish), it may also be seen as a cruel deception. The same set of circumstances can be seen in different ways and what is "right" depends on our point of view; and this in turn is shaped by cultural and social influences as well as our own individual views. The skill of a clinician lies in understanding the import of these competing views and in his or her ability to make a practical

decision.

The arguments about providing a new drug for Alzheimer's disease hinge around cost and clinical effectiveness, but also crucially depend on how important Alzheimer's disease is thought to be and the extent to which it matters whether some respite is obtained in the course of the disease. The question about whether a managed care organisation should selectively enrol well people may be connected only to the financial viability of the organisation or it may be seen in the wider context of the health needs of the population as a whole and care of the most vulnerable groups, involving the question of where medical skills can provide the greatest benefit. However, unless we can see the particular possibility we cannot make a judgment about it. We make sense of the world in a factual and evaluative way as an integral and coherent process; it is the way the world is perceived that gives reasons to act morally. Principles and codes are still active as general background concepts establishing and describing issues that are important, but they have a limited role in explaining why we hold the values we do. Although principles are derived in the context of an underlying moral theory, this is usually not explicit, and alone they cannot explain why a particular ethical position is important. If we try to

use them in this way, instead of acting as a conduit for moral clarity they may intervene and obscure a clear ethical view of a situation. In any particular situation principles cannot ensure a correct balance of the indeterminate number of factors that can or could be taken into consideration, but they can help to focus on relevant moral issues. Principles are not the basis on which moral judgments are made, and they cannot give an explanatory basis for making those judgments; moral judgments themselves are more basic and no more profound reference is available. Once one understands the limitations of moral principles it is easier to see where they can play a useful role. They are markers that establish and define important concepts and can be used to describe important aspects of the positions we hold. They give shape to our moral environment and summarise our ethical positions. This understanding of the role of principles and codes can allow a broader and more direct consideration of the moral issues. Instead of an inconclusive debate about conflicting principles, tending to narrow down the issues for consideration, this encourages broader and more robust moral discussion, requiring personal sensitivity as well as a trained appreciation of the many issues that can be relevant. We are more likely to understand why we feel the way we do and focus more clearly on comprehensive patient needs rather than taking a more limited perspective.

Conclusion

The content of general principles and codes represents concepts and values that can set the general ethical character and approach for health care. However, it is of little use in explaining individual ethical judgments. The implications for establishing ethical codes lie in recognising their potential value in describing the ethical environment and ethical attitudes that are shared by health care workers. Codes can also provide clear positions for a few headline ethical issues such as euthanasia, but cannot provide the certain answers to many of the ethical problems encountered in the course of everyday medical practice.

Alexander E Limentani, MBBS, FFPHM, PhD, is Director of Public Health, East Kent Health Authority, Dover. Address for correspondence:East Kent Health Authority, Protea House, New Bridge, Marine Parade, Dover, CTI 7 9AW

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on March 3, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

398

The role of ethical principles in health care and the implications for ethical codes

14 There are some similarities between the principles approach to ethics and ethical systems based on virtues, such as that of Aristotle. Both raise the questions: where do they arise from, and what is their basis or reference. They usually rest on a descriptive analysis of nature and thus fall into the categorv of

References and notes

1 Hurwitz B, Richardson R. Swearing to care: the resurgence in medical oaths. British Medical Journal 1997;315:1671-4. 2 Delamothe T. The Hippocratic Oath. British Medical J7ournal 1994;309:953. 3 Loudon I. The Hippocratic Oath. British Medical_Journal 1994; 309:414. 4 General Medical Council. Duties of a doctor: guidance from the General Medical Council. London: General Medical Council, 1995. 5 Berwick D, Hiatt H, Laneway P, Smith R. An ethical code for everybody in health care. British Medical ournal 1997-315: 1633-4. 6 For example: Wetherall DJ. The inhumanity of medicine. British Medical Jo7urnal 1994;309:1671 -2, and Mill M, Davies HTO, Macrae WA. Care of dying patients in hospital. British Medical Journal 1994;309:583-6. 7 Robin ED. The Hippocratic Oath updated. British Medical Jrournal 1994;309:96. 8 Gillon R, Lloyd A, eds. Printciples oJ health care ethics. Chichester: J Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1994. 9 Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Priniciples of bioniedical ethics [3rd ed]. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989. 10 Holm S. Not just autonomy - the principles of American biomedical ethics. Journal of Medical Ethics 1995;21:332-8. 11 Maclean A. The elimisnationi of mnorality. London: Routledge, 1993. 12 Gillon R. Defending 'the four principles' approach to biomedical ethics. Journal of Medical Ethics 1995;21:323-4. 13 Gillon R. Medical ethics: four principles plus attention to scope. British Medical Journal 1994;309: 184-8.

"naturalism". 15 Jones AH. Literature and medicine: narrative ethics. Lancet 1997;349: 1243-6. 16 See reference 9:51. 17 Ross WD. The Foundations of cthics. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1939. 18 See reference 9:52. 19 The problem of circularitv and justification of ethical judgments is present in virtue ethics and in most forms of ethical naturalism. The ethical values in question are derived from various natural aspects of the world and human nature which have already been judged to be desirable or not desirable. 20 This is a familiar ethical standpoint held by many ethicists and classically described by: Hume D. In: Selby-Bigge LA, ed. Enquiries conicernini<g humlani understanzding and conzcerninlg the principles of niorals. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975. 21 McNaughton, D. Moral vision. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998. This position is that which he calls "moral non-cognitivism". 22 Recent examples of this position are: Norman R. Making sense

of moral realism. Philosophical Investigations 1997;20,2:117-35. Diamond C. The realistic spirit. Wittgenstein, philosophy anid the niind. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1991, and McDowell J. Mind and world. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1994. This position is broadly derived from the works of Wittgenstein, for example: Wittgenstein L. In: Anscombe GEM, ed. Philosophical investigations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1978.

News and notes

Fifth European Forum Care

on

Quality Improvement in Health

Collaboration between managers and clinical leaders; Health policy and quality improvement for lasting success in the health care system; Implementing existing knowledge and disseminating best practices: our highest priority and our obligation to patients. For further information please contact the BMA/BMJ Conference Unit, PO Box 295, London WC1H 9TE. Telephone: +44 (0)171 383 6478; fax: +44 (0)171 383 6869; email:MMitchell(abma.org.uk

The organisers of the Fifth European Forum on Quality Improvement in Health Care, to be held in Amsterdam Rai, the Netherlands from 23 - 25 March 2000, are calling for papers. Themes of the forum include: Continuous quality improvement of patient care: what it is and how it can be implemented; Leadership, culture change and change management: the major success factors in continuous quality

improvement;

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on March 3, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

The role of ethical principles in health care and the implications for ethical codes.

A E Limentani J Med Ethics 1999 25: 394-398

doi: 10.1136/jme.25.5.394

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://jme.bmj.com/content/25/5/394

These include:

References Email alerting service

Article cited in:

http://jme.bmj.com/content/25/5/394#related-urls

Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the box at the top right corner of the online article.

Notes

To request permissions go to:

http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions

To order reprints go to:

http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To subscribe to BMJ go to:

http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/

Вам также может понравиться

- Dubai Energy Efficiency Training Program Presents Certified Energy Manager Course (Cem)Документ16 страницDubai Energy Efficiency Training Program Presents Certified Energy Manager Course (Cem)Mohammed ShamroukhОценок пока нет

- Master of Science in Nursing (Adult Health)Документ8 страницMaster of Science in Nursing (Adult Health)Sarah Agudo FernandezОценок пока нет

- Medical Professionalism in The New Millennium: A Physician CharterДокумент2 страницыMedical Professionalism in The New Millennium: A Physician CharterNewfaceОценок пока нет

- Concept of Family Nursing Process Part 1Документ14 страницConcept of Family Nursing Process Part 1Fatima Ysabelle Marie RuizОценок пока нет

- Principles of Teaching and LearningДокумент4 страницыPrinciples of Teaching and LearningAmberShanty TalerОценок пока нет

- UNIT 1 Reaction PaperДокумент3 страницыUNIT 1 Reaction PaperDeng Navarro PasionОценок пока нет

- Nursing As Art-CaringДокумент14 страницNursing As Art-CaringBasti HernandezОценок пока нет

- The Ethic of Care: A Moral Compass for Canadian Nursing Practice - Revised EditionОт EverandThe Ethic of Care: A Moral Compass for Canadian Nursing Practice - Revised EditionОценок пока нет

- Module I Group WorkДокумент6 страницModule I Group WorkNur Sanaani100% (1)

- Medical Ethics Manual En.2ndedition2009Документ140 страницMedical Ethics Manual En.2ndedition2009giosancristianОценок пока нет

- Health Assessment IntroductionДокумент50 страницHealth Assessment IntroductionEdna Uneta RoblesОценок пока нет

- Greene's Precede Procede ModelДокумент4 страницыGreene's Precede Procede ModelBk GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Respiratory Disorders 2.2Документ74 страницыRespiratory Disorders 2.2Deenjane Nishi IgnacioОценок пока нет

- What Is TeachingДокумент7 страницWhat Is TeachingAlexandre Andreatta100% (1)

- TFN Theories OutlineДокумент6 страницTFN Theories Outlineleviona halfОценок пока нет

- Ethico-Legal Considerations in The Care of Older AdultДокумент25 страницEthico-Legal Considerations in The Care of Older AdultMarlone James OcenaОценок пока нет

- Faye Glenn AbdellahДокумент31 страницаFaye Glenn AbdellahMikz JocomОценок пока нет

- Alternative Delivery SystemДокумент10 страницAlternative Delivery SystemJulieta Busico100% (1)

- Images of Nurses in MediaДокумент8 страницImages of Nurses in MediaRufus Raj50% (2)

- BIOETHICS 2011 TransparencyДокумент12 страницBIOETHICS 2011 TransparencyLean RossОценок пока нет

- Cultural and Ethical Issues in Working With Culturally Diverse Patients and Their Families The Use of The Culturagram To Promote Cultural Competent Practice in Health Care SettingsДокумент14 страницCultural and Ethical Issues in Working With Culturally Diverse Patients and Their Families The Use of The Culturagram To Promote Cultural Competent Practice in Health Care Settingslagaanbharat100% (1)

- Nursing Theory PaperДокумент5 страницNursing Theory Paperapi-268670617Оценок пока нет

- Department of Health: History, Policy, Budget, Programs For HealthДокумент57 страницDepartment of Health: History, Policy, Budget, Programs For HealthAngelica Cassandra VillenaОценок пока нет

- Hildegard Peplau Theory of Interpersonal RelationsДокумент1 страницаHildegard Peplau Theory of Interpersonal RelationsTADZMALYN JINANGОценок пока нет

- Nursing As An Art: CaringДокумент58 страницNursing As An Art: CaringZeus CabungcalОценок пока нет

- Community Mobilization in AECD FInal NoteДокумент35 страницCommunity Mobilization in AECD FInal NoteRyizcОценок пока нет

- Caring and The Professional Practice of NursingДокумент4 страницыCaring and The Professional Practice of NursingGalihPioОценок пока нет

- Biliran Province State University: ISO 9001:2015 CERTIFIED School of Nursing and Health SciencesДокумент9 страницBiliran Province State University: ISO 9001:2015 CERTIFIED School of Nursing and Health SciencesMaia Saivi OmegaОценок пока нет

- Funda Lecture SG #5Документ5 страницFunda Lecture SG #5Zsyd GelladugaОценок пока нет

- Tools of Public Health NurseДокумент43 страницыTools of Public Health NursernrmmanphdОценок пока нет

- Matrix of Proposed Revisions To RA No 9173Документ25 страницMatrix of Proposed Revisions To RA No 9173geinu17Оценок пока нет

- Ethics and The Covid-19 Pandemic Everyday Challenges Uams LGG No NarrationДокумент42 страницыEthics and The Covid-19 Pandemic Everyday Challenges Uams LGG No Narrationapi-136237609Оценок пока нет

- Hildegard E. Peplau - Psychiatric Nurse of The CenturyДокумент9 страницHildegard E. Peplau - Psychiatric Nurse of The CenturyLord Pozak Miller100% (1)

- AssignmentДокумент3 страницыAssignmentKim Rose SabuclalaoОценок пока нет

- Monitoring Intake & OutputДокумент16 страницMonitoring Intake & OutputSalome RahimОценок пока нет

- PH 251 PaperДокумент7 страницPH 251 PaperfreeromanticsОценок пока нет

- Beliefs and Healthcare Practices of Major Religious Traditions in The WorldДокумент4 страницыBeliefs and Healthcare Practices of Major Religious Traditions in The WorldDayan CabrigaОценок пока нет

- Beauchamp and Rauprich 2016 PDFДокумент12 страницBeauchamp and Rauprich 2016 PDFRazero4Оценок пока нет

- Ethics in Truth-Telling 2Документ8 страницEthics in Truth-Telling 2David WashingtonОценок пока нет

- Hildegard Peplaus Theory of Interpersonal RelationsДокумент101 страницаHildegard Peplaus Theory of Interpersonal Relationsapi-384387326Оценок пока нет

- Ethical Decision Making nsg434Документ6 страницEthical Decision Making nsg434api-470941612Оценок пока нет

- Ethics Essay Professional MisconductДокумент7 страницEthics Essay Professional Misconductapi-283071924Оценок пока нет

- Pharamacology Notes 3Документ7 страницPharamacology Notes 3Martinet CalvertОценок пока нет

- Bacillus Calmette - Guérin: Oral Polio VaccineДокумент1 страницаBacillus Calmette - Guérin: Oral Polio VaccineElleОценок пока нет

- Chapter 3Документ13 страницChapter 3Lawrence Ryan DaugОценок пока нет

- AbortionДокумент14 страницAbortionRizabel VillapandoОценок пока нет

- Name of StudentДокумент20 страницName of StudentHassan KhanОценок пока нет

- Baby Theresa: - Anencephalic Infants: Babies Without Brains'Документ14 страницBaby Theresa: - Anencephalic Infants: Babies Without Brains'AquinsОценок пока нет

- Human Becoming TheoryДокумент7 страницHuman Becoming TheoryDelvianaОценок пока нет

- Impacts of Parenting Practices To The Academic Behavior of Grade 12 Stem Students of Cor Jesu CoДокумент8 страницImpacts of Parenting Practices To The Academic Behavior of Grade 12 Stem Students of Cor Jesu CoMaxenia Fabores100% (1)

- NCM120-Theoritical Foundations of Transcultural Nursing-W2Документ3 страницыNCM120-Theoritical Foundations of Transcultural Nursing-W2Meryville JacildoОценок пока нет

- Nurs412 Ethical Issues in Nursing Paper Neuburg IntroДокумент2 страницыNurs412 Ethical Issues in Nursing Paper Neuburg Introapi-452041818100% (1)

- TheoryДокумент2 страницыTheoryjennelyn losantaОценок пока нет

- Ethical Theories: Prepared By: Regine Emerald B Dela Cruz RNДокумент20 страницEthical Theories: Prepared By: Regine Emerald B Dela Cruz RNRegine Dela CruzОценок пока нет

- Cancers and Abnormal GrowthsДокумент37 страницCancers and Abnormal GrowthsNABAKOOZA ELIZABETHОценок пока нет

- Chapter 9 Nursing Celebrates Cultural DiversityДокумент12 страницChapter 9 Nursing Celebrates Cultural DiversityDon DxОценок пока нет

- Bioethics and Moral Issues in NursingДокумент9 страницBioethics and Moral Issues in NursingPhilip Jay BragaОценок пока нет

- Nurs 05: Community Health Nursing 1 Community Health Nursing of Individual and Family As ClientДокумент23 страницыNurs 05: Community Health Nursing 1 Community Health Nursing of Individual and Family As ClientToyour EternityОценок пока нет

- Bioethics LectureДокумент40 страницBioethics LecturejeshemaОценок пока нет

- Fields in Nursing - FUNDAДокумент12 страницFields in Nursing - FUNDADanielle TorresОценок пока нет

- Bioethics: Walbert F. Delos Santos, RN - MNДокумент43 страницыBioethics: Walbert F. Delos Santos, RN - MNmaidymae lopezОценок пока нет

- Care of THEДокумент13 страницCare of THEDavid Frank EdisonОценок пока нет

- Foundation of Nursing AsepsisДокумент34 страницыFoundation of Nursing AsepsisYemaya84Оценок пока нет

- Student Copy Conti - Intrapartal Week8Документ25 страницStudent Copy Conti - Intrapartal Week8Toyour EternityОценок пока нет

- Annex A - ALAGA KA Barangay Health Station Screening Form - FINALДокумент4 страницыAnnex A - ALAGA KA Barangay Health Station Screening Form - FINALIke Homer SolomonОценок пока нет

- Doctor Nurse Bad BehaviorДокумент19 страницDoctor Nurse Bad BehaviorNewfaceОценок пока нет

- Medical Ethics APAДокумент35 страницMedical Ethics APANewfaceОценок пока нет

- Reporting Incompetent DoctorsДокумент9 страницReporting Incompetent DoctorsNewfaceОценок пока нет

- Breaking Bad NewsДокумент22 страницыBreaking Bad NewsNewfaceОценок пока нет

- DR Robert Blackburn Do1Документ3 страницыDR Robert Blackburn Do1NewfaceОценок пока нет

- DR Robert Blackburn DO2Документ1 страницаDR Robert Blackburn DO2NewfaceОценок пока нет

- Sri Alluri Sitaramaraju Memorial Tribal Museum at Kapuluppada in VizagДокумент2 страницыSri Alluri Sitaramaraju Memorial Tribal Museum at Kapuluppada in Vizagపైలా ఫౌండేషన్Оценок пока нет

- 6th Semester Final Result May 2021Документ39 страниц6th Semester Final Result May 2021sajal sanatanОценок пока нет

- Sample Essays For Class Comments (2007) - Writing 4Документ21 страницаSample Essays For Class Comments (2007) - Writing 4Phuong Mai Nguyen100% (1)

- Syllabus AssignmentДокумент4 страницыSyllabus Assignmentapi-269308807Оценок пока нет

- SEMINAR 08 Agreement and DisagreementДокумент5 страницSEMINAR 08 Agreement and Disagreementdragomir_emilia92Оценок пока нет

- Greek Philosophy: A Brief Description of Socrates, Plato, and AristotleДокумент3 страницыGreek Philosophy: A Brief Description of Socrates, Plato, and AristotleMissDangОценок пока нет

- Arola (2009) The Design of Web 2.0. The Rise of The Template, The Fall of Design PDFДокумент11 страницArola (2009) The Design of Web 2.0. The Rise of The Template, The Fall of Design PDFluliexperimentОценок пока нет

- دليل المعلم اللغة الانجليزية ص12 2009-2010Документ174 страницыدليل المعلم اللغة الانجليزية ص12 2009-2010Ibrahim AbbasОценок пока нет

- Letter of PermissionzzzДокумент3 страницыLetter of PermissionzzzRamwen JameroОценок пока нет

- Brecht SowДокумент10 страницBrecht SowRichard BaileyОценок пока нет

- Translanguaging in Reading Instruction 1Документ8 страницTranslanguaging in Reading Instruction 1api-534439517Оценок пока нет

- Holistic AssessmentДокумент3 страницыHolistic AssessmentJibfrho Sagario100% (1)

- Course Description Guide 2023 2024 1Документ90 страницCourse Description Guide 2023 2024 1api-243415066Оценок пока нет

- Kathryn Millar Resume PDFДокумент3 страницыKathryn Millar Resume PDFapi-262188497Оценок пока нет

- Contoh Paper SLR 4Документ11 страницContoh Paper SLR 4Noor Fazila Binti Abdul ManahОценок пока нет

- Ellaiza Peralta - Midterm Exam #2Документ3 страницыEllaiza Peralta - Midterm Exam #2ellaiza ledesmaОценок пока нет

- LP Math 1 2023Документ4 страницыLP Math 1 2023Ma. Fatima MarceloОценок пока нет

- DsfadfaДокумент2 страницыDsfadfaMaria Masha SouleОценок пока нет

- Plagiarism: What Is It? Why Is It Important To Me? How Can I Avoid It?Документ24 страницыPlagiarism: What Is It? Why Is It Important To Me? How Can I Avoid It?Kurnia pralisaОценок пока нет

- Ladderized CurriculumДокумент4 страницыLadderized CurriculumJonas Marvin AnaqueОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Social PedagogyДокумент22 страницыIntroduction To Social PedagogyesquirolgarciaОценок пока нет

- E127934498164309039138535-Ayush PathakДокумент15 страницE127934498164309039138535-Ayush PathakpriyankОценок пока нет

- Oral Communication in Context: Quarter 1 - Module 2 Message Sent!Документ13 страницOral Communication in Context: Quarter 1 - Module 2 Message Sent!John Lui OctoraОценок пока нет

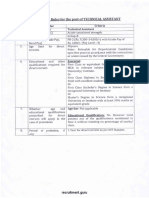

- NIT Recruitment RulesДокумент9 страницNIT Recruitment RulesTulasiram PatraОценок пока нет

- A Critical Analysis of Cultural Content in EFL Materials-A ReimannДокумент17 страницA Critical Analysis of Cultural Content in EFL Materials-A ReimannJasmina PantićОценок пока нет

- Pythagoras 3 (Solutions)Документ5 страницPythagoras 3 (Solutions)ٍZaahir AliОценок пока нет

- Print Curriculum FileДокумент2 страницыPrint Curriculum Fileanna.mary.arueta.gintoro031202Оценок пока нет