Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

How The Circadian Rhythm Affects Sleep, Wakefulness, and Overall Health

Загружено:

Rosemarie Fritsch100%(1)100% нашли этот документ полезным (1 голос)

238 просмотров62 страницыCircadian rhythm entrains an organism's functions to the environmental cycle of light and dark. Light has different effects on the circadian rhythm depending on when we are exposed to it. Circadian rhythm can be altered by a number of factors, especially stress.

Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

How the Circadian Rhythm Affects Sleep, Wakefulness, And Overall Health

Авторское право

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документCircadian rhythm entrains an organism's functions to the environmental cycle of light and dark. Light has different effects on the circadian rhythm depending on when we are exposed to it. Circadian rhythm can be altered by a number of factors, especially stress.

Авторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

100%(1)100% нашли этот документ полезным (1 голос)

238 просмотров62 страницыHow The Circadian Rhythm Affects Sleep, Wakefulness, and Overall Health

Загружено:

Rosemarie FritschCircadian rhythm entrains an organism's functions to the environmental cycle of light and dark. Light has different effects on the circadian rhythm depending on when we are exposed to it. Circadian rhythm can be altered by a number of factors, especially stress.

Авторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 62

The Circadian

Rhythm and its

disorders

PROF. DRA. ROSEMARIE FRITSCH

MATERIAL DOCENTE

ANDREW D. KRYSTAL, MD, MS

How the Circadian Rhythm

Affects Sleep, Wakefulness,

and Overall Health

1

Properties of the Circadian

Rhythm

The field of circadian rhythm research was launched

in the early 18th century (AV 1).

1

The circadian rhythm

entrains an organisms functions to the environmental

cycle of light and dark. This rhythm is seen in nearly all

species and plays an important role in synchronizing

organ systems to optimal phase relationships with each

other. Variations in many biological processes occur

over roughly a 24-hour period (AV 2).

This type of endogenous rhythmicity is also seen in

many other biological measures. For example, levels of

plasma melatonin increase in the evening and early

part of the night, while levels of plasma cortisol

increase over the course of the night, peak at waking,

and diminish throughout the day.

2

Our innate circadian rhythm can be modified by a

number of factors, especially light. For example, when

you travel to a new time zone, your body is on a

different schedule from the new environment, because

it continues to function for some time on the circadian

rhythm you developed in your previous location. The

longer you stay in the new environment, the more your

body aligns with its new environmental clock. This

process is driven by cues, especially exposure to light,

which tells us when it is day or night.

2

Light has different effects on the circadian rhythm

depending on when we are exposed to it.

1

Thus, if we

are exposed to light late during the night, this shifts

our rhythm so that we tend to go to bed and wake up

earlier. If we are exposed to light in the early part of the

night, this shifts our rhythm so that we tend to stay up

and sleep later. Exposure to light during the period

when we are usually awake has no effect at all.

Other factors that can affect our internal clock include

when we eat, our activity level, and caffeine intake.

3,4

Thus we often have gastrointestinal upsets in a new

time zone because we are eating when our body does

not expect to eat (ie, our digestive hormones are out of

synch with our meal time).

5

Our innate circadian

rhythm also affects how our autonomic nervous system

and our brain function.

6

3

2

Anatomy of the Circadian

Rhythm

The important role of the suprachiasmatic nucleus

(SCN) in regulating periodic behavior

7

has been

confirmed by a number of findings in animal studies

(AV 3).

1. When the SCN is lesioned, circadian

rhythmicity goes away because the SCN is no longer

able to stimulate the production of melatonin and

other substances that modulate the sleep-wake

pattern.

8

2. If cells are removed from the SCN and grown

in vitro, they continue to show self-sustaining circadian

rhythmicity.

9

3. If the SCN is transplanted from one animal to

another, the recipient manifests the circadian rhythm

of the donor, showing that the SCN can entrain

biological activity and drive a circadian process on its

own.

10

4

3

Genetics of the Circadian

Rhythm

Although researchers had been able to breed for

changes such as different eye or hair color for a long

time, it was not until the 1960s that Benzer first

demonstrated that behavior could be modified

genetically by breeding circadian behavioral patterns

into fruit flies.

11

This demonstrated that the chemical

clock in the SCN is under genetic control. A relatively

small number of genes and proteins regulate this

biological clock. The critical components of this genetic

system are the Period, Clock, and Cryptochrome (Cry)

genes, and these can be manipulated to alter the

circadian cycle.

12

The role of genetic factors in our circadian rhythm is

supported by the observation that preferred

sleep/wake schedules (eg, being a night owl or a

morning lark) tend to run in families. The tendency to

go to bed and get up very early (sleep phase advance),

is linked to a mutation in the human Period-2 (hPer2)

gene that is an autosomal dominant trait.

13

The

tendency to stay up late and sleep late (sleep phase

delay) is associated with several genes, including the

human Period-3 (hPer3) gene.

14

In humans, the circadian rhythm is controlled by

several core genes that operate via a series of feedback

loops (Figure 1). A transcriptiontranslation

negative-feedback loop powers the system, with a delay

between the transcription of these genes and the

negative feedback being a key factor that allows the

system to oscillate.

5

4

Effects on Sleep/Wake

Function

The SCN regulates our sleeping and waking through its

effect on 3 brain regions

7

:

! Ventrolateral preoptic area: releases "-

aminobutyric acid (GABA) and promotes sleep

! Lateral hypothalamic area: releases the

transmitter hypocretin/orexin that promotes

wakefulness

! Paraventricular hypothalamus: involved

in the release of melatonin

The interaction shown in the sleep/wake model

15

produces a consolidated period of wakefulness, driven

by the circadian rhythm, and a consolidated period of

sleep that occurs when the homeostatic drive to sleep

has built up and the wake-promoting systems have

shut down (AV 4).

16

The circadian rhythm system

enables us to stay awake for extended periods, despite

a growing homeostatic drive for sleep. It does this by

modulating the release of neurotransmitters, in

particular hypocretin/orexin, that maintain

wakefulness. Otherwise, we would have great difficulty

functioning, since we would fall asleep as soon as a

great enough drive to sleep had built. This is what

happens in narcolepsy, which involves abnormalities in

the hypocretin/orexin system.

17

6

7

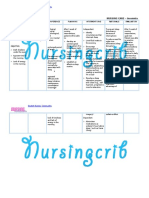

Process S represents

the homeostatic

built-up of sleep

pressure

Process C represents

the circadian rhythm

When the distance

between process S and

process C is largest,

sleep propensity will

be highest.

Borblys model of sleep-wake regulation (Borbly & Achermann, 1999).

Here you can see how sleep pressure keeps building up due to sleep deprivation, but since the circadian rhythm

keeps fluctuating by its regular 24 hour cycle, our sleep propensity will also fluctuate with this rhythm. In addition

this picture also shows that such sleep deprivation will lead to a higher slow wave activity (SWA, representing

deeper stages of sleep) during the recovery sleep. This type of activity is used as a marker for the homeostatic

process. When we for example go to bed earlier when homeostatic sleep pressure hasnt built up that much, this will

translate into less slow wave activity. Even within a sleep cycle itself you can see this phenomenon, with less

slow-wave activity during the second part of the sleep.

8

5

Problems in Sleep/Wake

Function

Problems can occur when the drive for wakefulness

and the drive for sleep are not correctly synchronized.

Thus, if you try to sleep when your body doesnt

normally sleep, you will sleep less and you will not

sleep as well because your circadian processes are

fighting the sleep drive. Individuals with circadian

rhythm sleep disorders often experience at least partial

sleep loss on a long-term basis. This is because they are

trying to sleep at an unfavorable time for extended

periods. Even modest prolonged sleep deprivation can

produce 4 types of serious physiological

abnormalities

18-23

:

! Metabolic dysfunction (increased appetite,

metabolism, or oxygen consumption; sympathetic

nervous system activation; decreased cerebral glucose

utilization in certain subcortical structures)

! Neuroendocrine abnormalities (low

thyroid-stimulating hormone; decreased levels of

growth hormone, prolactin, or leptin)

! Decreased resistance to infectious

disease

! Oxidative stress

9

Humans who experience prolonged sleep deprivation

also demonstrate higher rates of obesity and type 2

diabetes and neurobehavioral impairment, including a

shortening of voluntary and involuntary sleep latency

resulting in daytime sleepiness, microsleeps (intrusion

of sleep into wakefulness), and errors of omission and

commission on cognitive testing.

24,25

10

6

Role of the Circadian

Rhythm in Health and

Disease

By synchronizing the bodys biological clocks, the SCN

has extensive influence on peripheral tissues through

the autonomic nervous system.

26

For example, glucose

is released in a gradual, oscillating, sinusoidal-like

pattern over a 24-hour period. If animals are fed at

times other than their natural feeding times, the

original cycle continues. However, if you cut out the

SCN, glucose release becomes entrained to feeding

times and is no longer linked to other physiologic

processes related to eating and digestion.

27

Phase dyssynchrony occurs when the rhythms of

organs are out of synch with the SCN. Research in

animals and humans has shown that such disruptions

can have negative effects on health. For example, one

study found that disrupting the normal circadian

rhythmicity of hamsters with cardiomyopathy reduced

their median life span by 11%.

28

In the next chapter, Dr

Roth will discuss the types of negative effects that can

occur in humans who experience such phase

dyssynchrony, as occurs when someone has Shift Work

Disorder.

11

The circadian rhythm, a self-sustained

rhythm of biological processes observed

in nearly all species, is determined by

both genetic and behavioral factors. It

plays an important role in coordinating

and modulating sleep/wake function and

in many other biological processes.

Disturbances of the circadian rhythm

cause misalignment among biological

and behavioral processes that can lead to

disturbances in sleep/wake function and

other types of impaired functioning and

may affect our capacity to fight off

disease.

xii

Summary

Comprobar

respuesta

Pregunta 1 de 4

The circadian rhythm is

A. The determinant of cicada

lifecycles

B. A self-sustained rhythm of

biological processes observed in

nearly all species

C. Another name for jet lag

THOMAS ROTH, PHD

Shift Work Disorder:

Overview and Diagnosis

1

Circadian Rhythm Sleep

Disorders

According to the second edition of the American

Academy of Sleep Medicines International

Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-2),

1

the major

feature of circadian rhythm sleep disorders is a

misalignment between the patients sleep pattern and

the sleep pattern that is desired or regarded as the

societal norm (AV 1).

14

In addition to shift work disorder (SWD), the

ICSD-2 lists 8 other types of circadian rhythm sleep

disorders, including time zone change (jet lag)

syndrome and delayed and advanced sleep phase

syndromes. Many people have experienced jet lag

syndrome, caused by a lack of synchrony between your

internal clock and a new time zone in which you are

trying to function. Circadian rhythm disturbances can

also involve delayed or advanced sleep phases

(AV 2).

15

Because delayed and advanced sleep phase syndromes

often cause the person to be out of synchrony with the

prevailing sleep/wake patterns of society, they can lead

to significant morbidity. Recent studies

2-5

have found

that, when high school classes were started an hour or

two later, the number of car accidents decreased and

academic functioning improved. Problems can also

arise when there is chronic dyssynchrony between the

persons internal clock and external light and dark (ie,

when a person is required to stay awake and work

when it is dark and sleep when it is light), which can, in

some cases, lead to SWD.

16

2

Shift Work

It is important to distinguish between shift work and

SWD. Shift work is a job description. The vast majority

of people who work shifts adjust and do well. However,

a subgroup of people have great difficulty adjusting

their internal clocks and develop SWD due to a

mismatch between the sleep/wake schedule required

by their jobs and their own circadian sleep/wake

cycles.

Prevalence. It is estimated that 15%26% of the US

labor force works night, evening, or rotating shifts (AV

3).

6,7

Effects of shift work on the sleep/wake cycle.

Shift work affects the sleep/wake cycle in a number of

ways. No matter how many hours you have slept

during the day, trying to work during the downside of

the circadian rhythm (eg, between 12 AM and 6 AM) is

very difficult unless you can shift your internal clock.

Studies have found that, over a 24-hour cycle, both

subjective alertness and cognitive functioning decline

17

between 2 AM and 4 AM.8 Also, because you are not

sleeping at night, the homeostatic pressure to sleep is

not relieved, producing an ever-increasing pressure to

sleep.

9

However, only a subset of individuals who work

night or rotating shifts develop SWD, because

circadian rhythms are modulated not only by light and

dark, but also by other factors such as clock genes,

melatonin, and environmental cues (eg, noise).

10,11

18

3

Shift Work Disorder: An

Overview

Prevalence.

Drake et al12 found that 28% of those who work night

or rotating shifts, compared with 18% of day workers,

experienced insomnia and/or excessive sleepiness, and

they estimated the true prevalence of SWD to be

approximately 10% of those who work night or rotating

shifts. A study of 103 shift workers on a North Sea oil

rig (working 2 weeks on 7 nights/7 days, 12-hour shifts,

4 weeks off) by Waage et al13 found a relatively high

prevalence of SWD. They reported that 24 (23.3%) of

the shift workers were suffering from SWD and that,

during their 4-week period off work, the workers with

SWD reported significantly poorer sleep quality, more

subjective health complaints, and greater problems in

coping than individuals who did not have SWD. Shift

workers without SWD reported results similar to those

of day workers on the rig with regard to sleep,

sleepiness, subjective health complaints, and coping.

Diagnosis.

The ICSD-2 diagnostic criteria for circadian rhythm

sleep disorder, shift work type, are shown in (AV 4).

The differential diagnosis of SWD includes excessive

sleepiness due to obstructive sleep apnea, narcolepsy,

restless legs syndrome, and chronic insufficient sleep

due to daytime conflicts (eg, child care, environmental

factors, moonlighting at a second job). Comorbid

conditions (eg, increased prevalence of sleep apnea in

shift workers) can complicate the diagnosis of SWD.

Clinicians should also rule out comorbid disorders that

can cause insomnia and excessive sleepiness (eg,

primary insomnia, insomnia associated with

psychiatric disorders such as major depression), as

well as consider whether the person may be taking

medications or abusing drugs or alcohol to help with

sleep, which may be causing impairment at work.

19

20

4

Consequences of Shift

Work Disorder

Just as animal studies have found that disruptions in

circadian rhythm can affect health outcomes, studies in

humans have produced similar findings.

Gastrointestinal problems (eg, ulcers, functional

bowel disorders) are significantly increased in

individuals who work night or rotating shifts. However,

the increased prevalence of ulcers is associated not just

with shift work, but also with SWD. In a study

comparing 360 workers on rotating shifts, 174 on night

shifts, and 2,036 on day shifts, Drake et al12 found

that, among those who reported excessive sleepiness

and/or insomnia, the prevalence of ulcers was higher

among rotating shift workers (12.5%) and night shift

workers (15.4%) than day workers (6%). This effect was

not seen to any marked degree in those who worked

rotating or night shifts but did not have excessive

sleepiness and/or insomnia. Zhen Lu et al14 found that

the prevalence of functional bowel disorders was

higher in a sample of nurses who worked rotating

shifts (38%) than in those who worked day shifts (20%)

and that functional bowel disorder symptoms were

positively correlated with level of sleep disturbance.

Cancer. Shift work (whether or not the person has

SWD) has been found to be a risk factor for cancer.

Increased odds ratios for breast cancer have been

found in large samples of women who worked night

shifts, particularly with increasing duration of

nighttime employment.15-19 A study20 of 14,052

working men in Japan also found a significantly

increased risk of prostate cancer in those who worked

rotating shifts. The World Health Organization

International Agency for Research on Cancer has

concluded, Shift work that involves circadian

dysruption is probably carcinogenic to humans.21

Depression. The prevalence of depression is

significantly higher in those who work rotating and

night shifts than in day workers. In addition, while

insomnia or daytime sleepiness is a risk factor for

depression for all individuals, it is a much greater risk

factor for rotating or night shift workers.12

21

Cardiovascular effects. While insomnia is a risk

factor for hypertension in all individuals, it is a

significantly higher risk factor for shift workers with

insomnia.12 In contrast, although shift work is

associated with a significantly increased risk of heart

disease compared with nonshift work, this increased

risk is not associated with SWD.12

Excessive sleepiness and accidents. Insomnia is

associated with excessive sleepiness, which can impair

functioning, in rotating shift workers compared with

day workers.12 Studies have found a 12% frequency of

drowsy driving and an increased risk of driving

accidents related to sleepiness in rotating shift workers

with SWD compared with those without the disorder.

Relative risk of injuries and accidents increases with

each successive night shift worked.22 The effects of

shift work on patient and employee safety are an

important consideration in the health care field, where

many workers have extended shifts.23

Productivity. Similarly, it is the combination of night

or rotating shift work and daytime sleepiness or

insomnia that decreases productivity, not each factor

alone.12 Rotating shift workers with insomnia and/or

excessive sleepiness (SWD) missed significantly more

days of work (an average of 3 days per month over 3

months, a 10% decrease in productivity) than day

workers with these symptoms, who missed

approximately half a day of work per month over the

3-month period. This effect was not seen in shift

workers who did not have insomnia or excessive

sleepiness: they also missed a half day or less of work

over 3 months.12 Rotating shift workers who

experience both insomnia and excessive sleepiness are

at the greatest risk for lost productivity. (See Keller23

for a review of potential productivity problems in

health care workers on extended shifts.)

22

Shift work is very prevalent in our

society. However, only a subset of shift

workers meet criteria for SWD and need

treatment. Potential targets for treatment

are (1) the persons work schedule, (2)

difficulty sleeping during the day, and,

most important, given the accident data

discussed above, (3) difficulty

functioning because of excessive

sleepiness (eg, commuting home safely).

xxiii

Summary

Comprobar

respuesta

Pregunta 1 de 4

The Shift work disorder (SWD) is a

disruption of sleep patterns affecting

A. All people who work night or

rotating shifts

B. Primarily workers in natural

resources, con struction, and

maintenance occupations, such as

farmers, fishermen, and

construction workers

C. Approximately 10% of all shift

workers

D. Shift workers with hypertension

or cardiovascular disease

RICHARD D. SIMON, JR, MD

Shift Work Disorder:

Clinical Assessment and

Treatment Strategies

1

Identifying Circadian

Rhythm Disturbances

The most important clue that a patient may have a

circadian rhythm sleep disorder is an irregular

sleep/wake schedule. It is not possible for people to

change their circadian rhythm by more than 24 hours

in any given day.1,2 Thus, if a persons sleep/wake

schedule varies by more than 24 hours between days

on and off work, this suggests that he or she may have

circadian rhythm problems. One of the best ways to

identify such problems is to ask, Do you have

difficulty falling asleep at bedtime (insomnia) and

difficulty waking up when you need or want to

(hypersomnia)? If the patient says yes, this can

indicate a delayed sleep phase syndrome (ie, the

person may be a night owl). Individuals with this

sleep pattern often overuse the snooze button, hitting it

repeatedly. This pattern is frequently seen in teenagers.

People may also fall asleep very early, say at 8:00 PM

(hypersomnia), and wake up long before they want to

(eg, 3:00 AM). This sleep pattern reflects an advanced

sleep phase syndrome, a pattern frequently seen in the

elderly (AV 1).

25

2

Taking a Sleep History

The first step in assessing for shift work disorder

(SWD) is to take a thorough sleep history. The most

important item to ask about is the persons schedule of

work and sleep. Ask the person how his or her

sleep/wake schedule differs on work days, days off, and

vacation days. (The persons sleep schedule when on

vacation can give particularly helpful clues to the

persons intrinsic sleep/wake schedule.) (AV 2)

Assess the quality of sleep and wakefulness by asking

questions such as these:

! Do you sleep all night? Do you feel refreshed

in the morning? Or do you have fragmented sleep?

! Do you find it easy to stay alert throughout

the day? Or do you find yourself getting fatigued and

sleepy?

! Do you snore? Has anyone you live with

witnessed any episodes when your breathing appeared

to stop and then start again while you were asleep

(sleep apnea)?

Restless legs syndrome, characterized by an

uncomfortable, creeping, crawling, restless feeling in

the legs, can make it very difficult to fall asleep. If the

person reports snoring or witnessed episodes of apnea,

abnormal nocturnal behaviors (eg, injuring self or

others by acting out dreams), or symptoms suggesting

narcolepsy, a sleep study is required. It is also

important to ask about use of drugs or medications to

help with sleep or alertness (eg, caffeine in the

daytime, pills or alcohol to promote sleep) and the

quality and safety of the sleeping and waking

environments. A medical and psychiatric history is

necessary to identify conditions that might be

contributing to the sleep problems (eg, respiratory

problems, pain, depression, anxiety).

26

27

3

Assessment Tools

The simplest and most important assessment tool for

day-to-day clinical use by primary care physicians and

general psychiatrists is a sleep diary (AV 3).

Several easy-to-use scales are also commonly used in

sleep assessments. The Stanford Sleepiness Scale

3

and

the Epworth Sleepiness Scale

4

measure level of

excessive sleepiness. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale

asks the person to rate the likelihood of dozing in 8

different situations on a 4-point scale (0 = would never

doze to 3 = high chance of dozing), with a score of 10 or

greater suggesting the need for further evaluation. The

Insomnia Severity Index

5

assesses severity of current

sleep problems and their effect on daytime functioning.

Scales such as these are particularly useful for tracking

the effectiveness of an intervention over time.

In some situations, depression or anxiety scales or a

general outcome scale such as the Short-Form 36-Item

Health Survey, Version 2,

6

may be useful.

Actigraphy, which uses a device worn on the wrist to

record motion (ie, suggesting the person is awake) is

not generally necessary in assessing for SWD, since an

accurate history and a sleep diary will usually supply

all necessary information. Referral for overnight sleep

studies or polysomnography is also not indicated to

diagnose SWD, but is indicated if one suspects the

patient may have obstructive sleep apnea, parasomnias

leading to injurious nocturnal behaviors during sleep,

or narcolepsy. If narcolepsy is suspected in a shift

worker, it is usually necessary to have the worker

discontinue shift work for 24 weeks, because shift

work itself and the associated circadian misalignment

can confuse testing for narcolepsy. Narcolepsy is

suggested by a history of excessive sleepiness that often

started when the person was a teenager and predates

his or her shift work.

28

29

4

Differential Diagnosis and

Comorbid Conditions

Conditions that frequently occur in conjunction with

SWD include obstructive sleep apnea and restless

legs syndrome. Signs suggesting sleep apnea include

large neck size, crowded oropharynx, and reports of

witnessed apneas. Poor sleep habits of shift workers

can also cause them to develop learned insomnia

behaviors, referred to as psychophysiologic insomnia.

Other comorbid conditions include depressive

and/or anxiety disorders and chronic fatigue,

which can be difficult to distinguish in a person with

chronic circadian dyssynchrony.

30

5

Treatment Goals

The primary goal of treatment for SWD is to reduce the

degree of circadian misalignment by fostering better

sleep when it is desired and improved alertness and

functioning when appropriate. Other goals are to

identify and appropriately treat any intrinsic sleep

disorders (eg, apnea) and any medical or psychiatric

disorders that are present. Nonpharmacologic

strategies should be tried before considering use of

medications to promote sleep and/or alertness.

Zeitgebers: Strategies for

Shifting the Biological

Clock

The term zeitgeber (German for time giver) describes

an external cue that helps synchronize a plant or

animals internal clock to the earths 24-hour

light/dark cycle.

7

The most powerful zeitgebers in

humans are light, supplemental melatonin, dark, and

exercise.

Very bright light has powerful effects,

1,2

with

individuals being most sensitive to the effects of light

approximately 2 hours before or 12 hours after their

spontaneous wake time. If a pulse of very bright light is

given 24 hours before a persons spontaneous wake

time (eg, 3:00 AM for someone with a usual wake time

of 6:00 AM), the person is likely to wake up 24 hours

later (ie, to move toward a delayed sleep phase,

becoming more of a night owl). On the other hand, if

you expose the person to very bright light at the

spontaneous wake time or in the hour or so after, the

person is likely to wake up 24 hours earlier (ie, to

move toward an advanced sleep phase, becoming more

of a morning lark).

31

Melatonin acts in the opposite way.

1,2

When

administered in the evening, it tends to make the

person fall asleep and wake up earlier (ie, to advance

the sleep phase). When administered in the morning, it

tends to make the person stay up later and wake up

later (ie, to delay the sleep phase).

Dark also has powerful effects on sleep phase.

1,2

Thus,

naps in a darkened environment act in much the same

way as melatonin. Greatly limiting exposure to light in

the evening will help you go to sleep earlier.

Conversely, absence of light in the morning will help

you sleep later. Because primarily the shorter

wavelengths (eg, blue light) lead to phase shifts, one

strategy for exposing the biological clock to dark is to

wear dark or blue-blocking sunglasses.

Similar phase response curves have been found for

exercise.

1,2

Exercising in the early evening tends to

phase-advance you and make you more of a morning

person. Exercising after midnight generally does the

opposite. However, exercise is not often used to adjust

sleep phase in humans (AV 4).

32

6

Practical Strategies for

Sleep Problems Associated

With Shift Work

To minimize problems associated with shift work,

workers should have as predictable a work schedule as

possible. It is also helpful if employers provide

sufficient breaks at work, allow shift workers to take a

short nap at work, avoid schedules that involve

working multiple days in a row, and provide sufficient

time off between work days. These strategies are

important because the vast majority of shift workers do

not fully entrain (ie, their biological clocks never fully

synchronize with their required work and sleep

schedules). It is also useful to try to limit commuting

time and overtime.

Another key strategy is to minimize circadian

misalignment between work days and days off, which

involves educating and enlisting the support of

significant others in the shift workers family and

immediate social circle. For most shift workers, this

means producing a phase delay in their biological

clocks (ie, to make them more night owls). This is

done by changing the persons environment so that he

or she gets as much light as possible during the

scheduled day and as little light as possible during

the scheduled night and by minimizing the difference

in sleep/wake patterns between work days and days

off. Practically, this means having bright light at work,

wearing dark glasses during the drive home when one

is likely to be exposed to light, and keeping the

bedroom, bathroom, and other rooms that will be used

at home as dark as possible during the desired sleep

period.

Shift workers who achieve complete or even partial

entrainment (ie, their biological clocks become

realigned with a new sleep/wake schedule) show

marked improvements in psychomotor vigilance,

memory, reaction time, night work performance, and

mood and reductions in fatigue, excessive sleepiness,

and mental exhaustion compared with those who do

not

8,9

(AV 5).

33

34

SWD needs to be considered in all

patients who have a sleep/wake schedule

that differs by more than 24 hours on

work days compared with days off and

who exhibit symptoms of sleepiness at

work and difficulty sleeping during the

desired sleep time. Asking about snoring

and restless legs symptoms can lead to

comorbid diagnoses that, if treated, can

improve the shift workers sleep.

xxxv

Summary

Comprobar

respuesta

Pregunta 1 de 4

The most important clue that a patient may

have a circadian rhythm sleep disorder is:

A. Complaint of restless legs

syndrome

B. An irregular sleep/wake schedule

C. Depression

D. Sleep apne

4

Cases

1

The young man with

difficulty falling asleep

A 24-year-old male patient reports difficulty falling

asleep, followed by daytime sleepiness, a pattern that

has persisted for about 5 years since his days as a

student. His excessive sleepiness has become more

severe during the past year due to the 8 AM starting

time for his work shift. He recently needed to take 2

personal days off from work due to inability to report

on time. Once asleep, he does not have difficulty

staying asleep. His bedtime ranges from 11:30 PM to

1:00 AM, with time required to fall asleep averaging 2

hours. His wake time is scheduled for 6:45 AM on

workdays. Weekday mornings are particularly difficult.

The patient feels "out of it" until about noon. He has

fallen asleep while driving to work and has had several

near-miss traffic accidents the past month.

The patient is being treated with sertraline 50 mg for

depression, which was first diagnosed 2 years ago, and

with zolpidem 10 mg as needed for insomnia. He

suffers from exercise-induced asthma. His blood

pressure is stable at 130/80 mm Hg, and he has a body

mass index (BMI) of 26. His mother and brother both

suffer from similar types of insomnia symptoms.

Physical and neurological exams were normal. He had

a score of 12 on an ESS questionnaire.

37

Comprobar

respuesta

Which of the following additional assessments

would you next employ for this patient?

A. Polysomnogram

B. Actigraphy

C. Sleep diary

D. Multiple sleep latency test

Like the ESS, a sleep diary is a first-line diagnostic tool

for suspected sleep disorders because of its ease of

administration and low cost. A sleep diary will plot the

patient's sleep pattern and is suitable as the next test in

this case. Actigraphy may be used but is not

commonly available in primary care practices.

Polysomnograms and multiple sleep latency tests are

more elaborate diagnostic methods reserved for

validation of initial screening tests, or to evaluate for

other sleep disorders, such as OSA and narcolepsy.

Circadian rhythm sleep disorders are disorders of sleep

and wake timing. Thus, an essential aspect of

diagnosing and treating circadian rhythm sleep

disorders is to determine whether symptoms are due to

chronic or short-term misalignment of the patient's

circadian rhythms with external 24-hour cues, or due

to other etiologies. A sleep diary is an easily

administered diagnostic tool that can be easily used in

a primary care setting to determine if the patient's

internal circadian sleep and wake rhythm is misaligned

with work or social schedules.

The pathophysiology of circadian rhythm sleep

disorders is multifactorial, only partially understood.

What is of importance to clinicians is that they

consider the full range of physiological, behavioral, and

environmental factors involved in a clinical sleep

disorder when developing treatment strategies. In the

case of Circadian rhythm sleep disorders, their etiology

can be intrinsic due to endogenous factors, or extrinsic

due to factors in the environment.

ASSESSMENT

The patient completed a 7-day sleep diary during his

normal work week (see the Figure). The diary confirms

a bedtime of 10:30-11:45 PM on workdays and a

prolonged time to fall asleep of over 2 hours. On

weekends, bedtimes are later (midnight to 1 AM), but it

still takes 1-2 hours to fall asleep. Note that on

38

Saturday, he sleeps in until 11 AM, and on Thursday, he

took a nap in the afternoon between 3 to 4 PM.

Average sleep duration is less than 6 hours on

weekdays. The patient went on vacation for a 10-day

period shortly after his initial visit, providing an

opportunity for actigraphy monitoring during his

preferred sleep schedule. Actigraphy showed an

average bedtime of 3-4 AM and an average wake time

of 10 AM to noon while on vacation. After returning

from vacation, the patient said he had been able to

catch up on his sleep and feels much better. However,

after returning to work, he reports that his bedtime

insomnia has returned, often preventing him from

falling asleep before 2 AM.

39

Comprobar

respuesta

Pregunta 1 de 2

Based on the previous description, what is

the most suitable diagnosis for the patient

in case 1?

A. Psychophysiologic (conditioned)

insomnia

B. Insomnia due to depression

C. Advanced sleep-phase disorder

D. Delayed sleep-phase disorder

The patient's symptoms are consistent with delayed

sleep-phase disorder, namely a stable pattern of delay

in the nighttime sleep period until the early morning

hours followed by inability to wake up until the late

morning. In contrast, patients with insomnia disorder,

including psychophysiologic insomnia or insomnia

associated with depression, do not typically show a

stable pattern of delayed sleep and when allowed to

sleep at a later time have normal sleep duration.

Advanced sleep-phase disorder is characterized by

early sleep onset and premature awakening, the

opposite of delayed sleep-phase disorder.

Treatment should be aimed at advancing the timing of

sleep and wake cycle. Morning bright light exposure

(close to natural awakening) signals the circadian clock

to advance its timing. Similarly, low-dose melatonin

given in the late afternoon or early evening signals the

clock to advance. (Melatonin is not approved by the

FDA for the treatment of circadian rhythm sleep

disorder.) One should avoid bright light exposure in

the evening because it will delay or shift circadian

rhythms. An advance in the timing of circadian

rhythms (advance shift) will result in earlier sleep

onset and awakening, which is needed to synchronize

with the desired sleep/wake and work schedule. In

addition, bright light in the morning can have an

alerting effect, which can facilitate waking.

Pharmacologic therapies such as hypnotic agents or

antidepressants to treat symptoms of insomnia without

resetting the circadian clock will only partially address

symptoms, rather than the underlying cause of the

symptoms.

40

DIAGNOSIS

The patient's history confirms that his ability to

perform on the job is impaired by his excessive

sleepiness and lack of energy and alertness in the work

place. He thinks that his occasional feelings of

depression and anxiety are associated with poor sleep.

Although he is concerned about poor performance

associated with his sleep pattern, he does not feel

anxious overall. "I'm just never sleepy at 10:30 at

night," he says. He is diagnosed with delayed

sleep-phase disorder. According to the International

Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10),

diagnostic billing codes for Circadian rhythm sleep

disorders start with G47.2, with delayed sleep-phase

disorder G47.21.

41

Episodic and

paroxysmal

disorders G40-

G47

Sleep

disorders G47

Circadian

rhythm sleep

disorder G47.2

delayed sleep

phase type

G47.21

INITIAL TREATMENT

The patient was instructed to purchase a bright light

box, readily available on the Internet, and sit in front of

the light source (1-2 feet away) for 1 hour in the

morning, starting at 10:30 AM on a weekend day (off

work). Light box exposure was then advanced by 1 hour

each morning until he started treatment at his normal

workday wake up time of 6:30 AM. He was also

instructed to take melatonin 1 mg at 8 PM for the next

3 weeks.

Recognizing the pattern of the patient's sleep-wake

cycle is the key to both the diagnosis and treatment of

circadian rhythm sleep disorders. The goal of circadian

rhythm sleep disorder is to synchronize (entrain) the

sleep-wake cycle with the appropriate external physical

environment and work schedule. Treating symptoms of

insomnia or excessive sleepiness without resetting the

circadian rhythm sleep disorder patient's circadian

clock will only partially address the symptoms, rather

than the underlying cause of the symptoms. Thus, the

principal goal of therapy for the delayed sleep-phase

disorder patient (as illustrated in case 1) is to advance

the timing of circadian rhythms. Conversely, the goal of

therapy for an advanced sleep-phase disorder patient

would be to delay the timing of circadian rhythms.

42

Comprobar

respuesta

What is the principal goal in managing the

sleep disorder for this case?

A. Advance the timing of the patient's

circadian rhythms

B. Increase the duration of sleep

C. Provide treatment with the use of

prescription drugs

D. Avoid sleeping so late on weekends

FOLLOW-UP

The patient reported good compliance with nightly

MLT treatment but could tolerate morning light

therapy for only 30-40 minutes on some days. He

reports a bedtime of 11 PM, falling asleep by midnight

on most days. He is able to awaken with the aid of an

alarm clock at 6:30 AM on workdays, but feels like he

could sleep longer. He wakes up naturally at 8-10 AM

on weekends.

43

2

The old man with a history

of difficulty staying asleep

PRESENTATION AND PATIENT HISTORY

A 66-year-old man has a history of difficulty staying

asleep. This has caused him to be a habitual early riser

around 5 AM virtually every day for about 10 years. His

difficulty in staying asleep has become progressively

worse. His typical sleep pattern is to fall asleep on the

couch by 7 PM, wake up 90 minutes to 2 hours later,

and then go to bed around 9:30-10 PM. He usually

sleeps until 3-4 AM or until he goes to the bathroom,

after which he has difficulty going back to sleep. He

often lays awake in bed for up to 2 hours until he rises

at 5-5:30 AM. By the afternoon and early evening, he is

excessively sleepy and struggles not to fall asleep. He

reports that his ES has affected his social life and

relationship with his wife due to his drowsiness. He

says his ideal sleep schedule would be to fall asleep

about 10 PM and wake at 5-6 AM. His score on an ESS

questionnaire is 12.

He has a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia,

for which he is treated with olmesartan and

atorvastatin. The patient has a paternal family history

of early risers. His wife has informed him that he

snores lightly but has not witnessed any breathing

irregularities during his sleep. He has no restless legs

symptoms and is not depressive, but he is frustrated by

his sleep problem. He has reflux symptoms when he

eats late. His physical examination, cognition, and

mental health status are normal.

44

Comprobar

respuesta

What is the most likely diagnosis for the patient

in this case?

A. Advanced sleep-phase disorder

B. Delayed sleep-phase disorder

C. Irregular sleep-wake pattern

D. Insomnia due to nocturia

The patient's symptoms are consistent with advanced

sleep-phase disorder, a stable pattern of sleep onset

several hours earlier than the usual nighttime sleep

period and sleep offset several hours before the normal

or desired wake time. Advanced sleep-phase disorder is

more common in older adults. Nighttime urination

typically occurs in men of the patient's age but is not

the primary cause of an advanced sleep-wake cycle or

daytime sleepiness in this case.

Schematic of typical sleep phase vs 4 circadian rhythm

sleep disorders. A feature of ASPD, DSPD, and

non-24-hour sleep pattern is that the sleep architecture

and total amount of sleep are comparable to the

normal pattern, but timing of sleep does not conform

to a conventional 24-hour schedule.

45

46

47

ASSESSMENT

The patient returns 3 weeks later and provides a 7-day

sleep diary (Figure). The diary shows that he lays

awake for 1-2 hours before getting out of bed at 5-5:30

in the morning. The premature wake times are

preceded by involuntary drowsiness and napping in the

early evening from 5:30-8 PM. His symptoms support

a diagnosis of Advanced sleep-phase disorder.

48

Comprobar

respuesta

Which treatment is most appropriate for

this patient?

A. An antidepressant

B. A stimulant

C. Melatonin

D. Light therapy

Timed light exposure for 1-2 hours in the evening (7-9

PM) is indicated as standard first-line therapy to delay

onset of the sleep cycle in cases of advanced

sleep-phase disorder. In addition, the patient is

counseled on sleep hygiene and told to avoid naps

before a targeted bedtime of 10:30 PM. Physical

activity such as walking before or after dinner is

recommended to maintain wakefulness during the

evening. Low-dose Melatonin taken in the morning

may be useful but may induce residual sleepiness. The

patient does not suffer from mood disorders, so

antidepressant medication is not indicated. Stimulants

have a limited role in treating advanced sleep-phase

disorder. Caffeine taken in moderation is acceptable

for maintaining wakefulness but is not considered a

primary therapy for advanced sleep-phase disorder.

The wake-promoting agents modafinil and armodafinil

are approved for short-term use in treating excessive

sleepiness associated with sleep apnea, narcolepsy, and

shift-work disorder, but not advanced sleep-phase

disorder.

49

Actigraphy

Consiste en un pequeo aparato que se coloca en la mueca del individuo y

registra sus movimientos a lo largo de la noche. Los datos obtenidos se

analizan mediante un sistema computarizado que permite acumular datos

hasta un mximo de 22 das consecutivos, y estimar diversos parmetros del

sueo (Hauri & Wisbey, 1992). Contrariamente a la polisomnografa, la

actigrafa de mueca no es un instrumento costoso ni intrusivo y su

utilizacin es sencilla. Permite registrar periodos de 24 horas y proporciona

informacin del ritmo circadiano. No obstante, slo mide vigilia y sueo y no

estadios especficos de sueo.

Trminos del glosario relacionados

ndice

Captulo 4 - The young man with difficulty falling asleep

Arrastrar trminos relacionados aqu

Buscar trmino

Chronic fatigue

El Sndrome de Fatiga Crnica (SFC) es una enfermedad grave compleja y debilitante

caracterizada por una fatiga intensa, fsica y mental, que no remite, de forma

significativa, tras el reposo y que empeora con actividad fsica o mental. La aparicin

de la enfermedad obliga a reducir sustancialmente la actividad y esta reduccin de

actividad se produce en todas las Actividades de la Vida Diaria (AVD).

El impacto del SFC en la vida del enfermo es demoledor, tanto por la enfermedad en s

misma como por el aislamiento e incomprensin del entorno, de hecho, las medidas

validadas de calidad de vida, cuando se comparan con otras enfermedades, evidencian

que el SFC es una de las enfermedades que peor calidad de vida lleva aparejada.

Adems de estas caractersticas bsicas, algunos pacientes de Sndrome de Fatiga

Crnica (SFC) padecen diversos sntomas inespecficos, como debilidad muy especial

en las piernas, dolores musculares y articulares, deterioro de la memoria o la

concentracin, intolerancia a los olores, insomnio y una muy lenta recuperacin, de

forma que la fatiga persiste ms de veinticuatro horas despus de un esfuerzo.

Casi siempre la enfermedad es crnica (curaciones inferiores al 5-10%) y de un gran

impacto en la vida del enfermo. De hecho, la mejor medida del impacto de la

enfermedad es evaluar las actividades previas y posteriores a la instauracin de la

enfermedad, tanto en la esfera fsica, como en la intelectual, aunque disponemos de

escalas validadas de Clasificacin de la Severidad e Impacto de la Fatigabilidad

Anormal en un paciente concreto, como por ejemplo la Escala IFR de Fatigabilidad

Anormal.

Trminos del glosario relacionados

ndice

Captulo 3 - Differential Diagnosis and Comorbid Conditions

Arrastrar trminos relacionados aqu

Buscar trmino

Circadian rhythm

Los ritmos biolgicos endgenos pueden ser de diferentes frecuencias [Adn; 1995,

Goldbeter; 2008,Haus; 2009,Ohdo; 2010,Smolensky et al; 2007,Valds-Rodrguez;

2009,Volpato et al; 2005]:

Ritmos de frecuencia alta (con periodos cortos menores a 30 minutos):

- Ritmos con periodos de un milisegundo a 10 segundos de duracin, como el de la

actividad elctrica cortical.

- Ritmos con periodos de segundos de duracin, como el cardaco y respiratorio.

- Ritmos con periodos de 30 segundos a 20 minutos de duracin, como las oscilaciones

bioqumicas.

Ritmos de frecuencia media (con periodos intermedios desde media hora

hasta 6 das de duracin):

- Ritmos ultradianos, ciclos de media hora a 20 horas de duracin, como los ritmos

hormonales, las fases del sueo, la depresin pospandrial o post-lunch.

- Ritmos circadianos o nictamerales, con periodos alrededor de 24 horas de duracin

(24 4 horas), producidos por la rotacin terrestre y que determinan los ciclos del da

y la noche (luz-oscuridad) fundamentales para regular la temperatura corporal, la

secrecin de cortisol y melatonina, el ciclo de vigilia-sueo, etc.

- Ritmos dianos, con periodos de 24 2 horas de duracin.

- Ritmos infradianos, con periodos de 28 horas a 6 das de duracin, como los procesos

metablicos.

Ritmos de frecuencia baja (con periodos largos de ms de 6 das de

duracin):

- Ritmos circaseptanos, con periodos de 7 3 das de duracin, como el del bienestar

subjetivo.

- Ritmos circadiseptanos, con periodos de 14 3 das de duracin.

- Ritmos circavigintanos, con periodos de 21 3 das de duracin.

- Ritmos circatrigintanos o circamensuales, con periodos de unos 30 das de duracin

(30 5 das), definidos por el ciclo lunar de traslacin lunar y que determinan la

alternancia de las mareas y la luminosidad del cielo nocturno.

- Ritmos circanuales o estacionales, con periodos de aproximadamente 1 ao de

duracin (1 ao 2 meses), definidos por el ciclo solar de traslacin terrestre y que

determinan las estaciones del ao, con sus diferencias en intensidad de luz y

temperatura y regulan la reproduccin e hibernacin animal.

- Ritmos de aos de duracin, como en ecologa y epidemiologa.

De todos ellos los ms estudiados son los circadianos y los estacionales.

Trminos del glosario relacionados

ndice

Captulo 1 - Properties of the Circadian Rhythm

Arrastrar trminos relacionados aqu

Buscar trmino

Circadian rhythm sleep disorders

LOS TRASTORNOS DEL SUEO POR ALTERACIN DEL RITMO CIRCADIANO

Ante situaciones extremas para el individuo se pierde la periodicidad circadiana de

aproximadamente 24 horas, (como en el turno laboral nocturno, enfermedades

intercurrentes, etc.). Hay una interrupcin transitoria del funcionamiento del NSQ y

pierde el control de los osciladores perifricos. [Haus;

2009,www.sleepassociation.org]. Es lo que ocurre en los TSRC en los que la

perturbacin del patrn de sueo es consecuencia de la desincronizacin entre el ritmo

de vigilia-sueo deseado (por las circunstancias del entorno del individuo) y su propio

ritmo vigilia-sueo circadiano marcado por el marcapasos interno o reloj biolgico

[Barion et al; 2007,Haus et al; 2006,Lu et al; 2006, Martinez et al; 2010]. Las

repercusiones que tendrn en estas personas (hasta que se adapte su ritmo) sern

alteraciones del sueo (insomnio de conciliacin y mantenimiento y excesiva

somnolencia diurna [Lu et al; 2006]), biolgicas a nivel celular y molecular, cambios

en la actividad cerebral, alteraciones funcionales y del metabolismo de lpidos y

carbohidratos, cambios en la resistencia a la insulina, cambios hormonales-endocrinos

(secrecin de hormona de crecimiento, melatonina, etc.), etc. [Haus et al;

2006,www.sleepassociation.org].

Los TSRC segn la segunda edicin de la Clasificacin Internacional de los Trastornos

del Sueo [Westchester; 2005] de la Academia Americana de Medicina del Sueo

(American Academy of Sleep Medicine o AASM) pueden ser primarios, por mal

funcionamiento del reloj biolgico, (Sndromes del retraso y adelanto de fase, Patrn

irregular del ciclo vigilia-sueo y Sndrome de ciclo vigilia-sueo diferente a 24 horas);

secundarios, en los que son las circunstancias del medio ambiente las que provocan el

desfase del reloj biolgico, (Jet lag, TSRC secundario al trabajo a turnos, TSRC

secundario a enfermedades y al consumo de frmacos u otras sustancias) y otros TSRC

no especificados [Martinez et al; 2010].

Trminos del glosario relacionados

ndice

Captulo 2 - Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders

Arrastrar trminos relacionados aqu

Buscar trmino

Delayed or advanced sleep phases

Sndrome de la fase del sueo retrasada. Se caracteriza, como su propio nombre

indica, por un retraso habitualmente mayor de dos horas en los tiempos de

conciliacin del sueo y despertar, en relacin con los horarios convencionales o

socialmente aceptados. Los individuos afectados por esta entidad tienen una prctica

imposibilidad para dormirse y despertarse a una hora razonable, hacindolo ms tarde

de lo habitual. La estructura del sueo es normal, destacando nicamente en los

estudios polisomnogrficos un importante alargamiento de la latencia del sueo o el

tiempo que tardan en dormirse los pacientes. Estos tienen con frecuencia problemas

socio-laborales, ya que sus horas de mayor actividad suelen ser las de la noche. En

estos individuos estn tambin retrasados otros ciclos biolgicos circadianos, como

son el de la temperatura y el de la secrecin de melatonina.

Sndrome de la fase del sueo adelantada. Es menos frecuente que el sndrome

de la fase retrasada. Los periodos de conciliacin del sueo y de despertar son muy

tempranos o precoces con respecto a los horarios normales o deseados. Los sujetos que

padecen este sndrome suelen quejarse de somnolencia durante la tarde y tienen

tendencia a acostarse muy pronto, y se despiertan espontneamente tambin muy

pronto por la maana. Cuando se acuestan muy tarde, por factores exgenos, sufren

un dficit de sueo, ya que su ritmo circadiano les despierta igualmente pronto. No se

conoce su prevalencia, pero se estima en torno al 1% en los adultos y ancianos, y

aumenta con la edad (probablemente porque con la edad se acorta el ritmo

circadiano). Afecta a ambos sexos por igual.

Trminos del glosario relacionados

ndice

Captulo 2 - Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders

Arrastrar trminos relacionados aqu

Buscar trmino

Endogenous rhythmicity

La periodicidad circadiana, como la del ritmo vigilia-sueo, est mediada

genticamente, tiene un control y est sincronizada al ciclo regular de 24 horas de

luz-oscuridad ambiental por los osciladores internos, y por ltimo est modulada por

influencias ambientales que permiten su adaptacin a las condiciones variables del

entorno [Adn; 2004,Aschoff; 1967,Chiesa et al; 1999, Haus et al; 2006]:

Trminos del glosario relacionados

ndice

Captulo 1 - Properties of the Circadian Rhythm

Arrastrar trminos relacionados aqu

Buscar trmino

Escala de Somnolencia de Epworth

La Escala de Somnolencia de Epworth (Johns, 1991) estima la somnolencia

subjetiva diurna de individuos adultos. La escala de ocho tems, pide al

individuo que punte de 0 a 3 el grado de somnolencia en diferentes

situaciones cotidianas, diferenciando somnolencia de fatiga. Actualmente,

un puntaje de 10 o ms se considera como el punto de corte ms

apropiado para detectar somnolencia patolgica. La Escala de

Somnolencia de Epworth es sencilla de administrar, es actualmente la

medida subjetiva de somno- lencia diurna ms corrientemente empleada.

Chung (2000) en su estudio encontr que la escala resultaba ser un

instrumento til para diferenciar pacientes con y sin un grado patolgico de

somnolencia objetiva diurna. Tambin Sanford, Lichstein, Durrence, Riedel,

Taylor & Bush (2006) detectaron que los sujetos con insomnio obtienen

puntuaciones ms elevadas en la Escala de Somnolencia de Epworth que los

sujetos sin insomnio, lo que puede ayudar a discriminar sujetos con el

trastorno de aquellos sin el mismo. La escala ha sido traducida al alemn y

espaol y se ha encontrado que su uso no resulta afectado por factores

culturales o de lenguaje (Chung, 2000; Izquierdo-Vicario, Ramos-Platn,

Conesa-Peraleja & Lozano-Parra, 1997).

Trminos del glosario relacionados

ndice

Captulo 4 - The young man with difficulty falling asleep

Captulo 4 - The young man with difficulty falling asleep

Captulo 4 - The old man with a history of difficulty staying asleep

Arrastrar trminos relacionados aqu

Buscar trmino

Genetic control

En las clulas del organismo (en cerebro y tejidos perifricos), el mantenimiento de la

ritmicidad circadiana depende de algunos genes que hay en su ncleo, genes del reloj

o genes circadianos, que componen la maquinaria molecular del reloj circadiano

[Haus; 2009,Hofman et al; 2005]. Se expresan mediados por seales humorales y

neuronales, como la melatonina, que parten de los osciladores internos [Haus et al;

2006,Hofman et al; 2005].

Las lneas de investigacin gentica han tratado de identificar los polimorfismos y

mutaciones que sufren estos genes y se asocian al cronotipo de una persona (medido

por el Cuestionario de matutinidad-vespertinidad de Horne y stberg), determinados

TSRC en algunas familias, adicciones (a drogas y alcohol) y otras enfermedades

(diabetes, enfermedades cardiovasculares, cncer, etc.) [Bechtold et al; 2010,Eismann

et al; 2010,Rosenwasser; 2010,Sack et al; 2007b].

Trminos del glosario relacionados

ndice

Captulo 1 - Genetics of the Circadian Rhythm

Arrastrar trminos relacionados aqu

Buscar trmino

Obstructive sleep apnea

El sndrome de apnea e hipopnea obstructiva del sueo (SAHOS) es una enfermedad

frecuente que afecta al 4% de la poblacin adulta. Su sntoma cardinal es la

somnolencia diurna excesiva que, junto a la alteracin del nimo y deterioro cognitivo,

producen un deterioro progresivo en la calidad de vida de los pacientes. Adems, se ha

asociado a mayor riesgo de hipertensin arterial, morbimortalidad cardiovascular,

accidentes laborales y de trnsito. Esta entidad est ostensiblemente subdiagnosticada,

por lo que es necesario mejorar su conocimiento para aumentar la pesquisa para su

adecuado tratamiento.

Trminos del glosario relacionados

ndice

Captulo 3 - Differential Diagnosis and Comorbid Conditions

Arrastrar trminos relacionados aqu

Buscar trmino

Restless legs syndrome

Corresponde a un trastorno del movimiento caracterizado por la presencia de

sensaciones desagradables localizadas en extremidades inferiores que llevan a la

imperiosa necesidad de moverlas. Esta sensacin empeora con el reposo e interfiere

con el sueo.

La prevalencia de este sndrome es variable segn los estudios y va de 10,6% en USA, y

11,6% en Espaa con una mayor proporcin de mujeres versus hombres de 3:1. La

prevalencia va aumentando con la edad, incluso los primeros sntomas pueden

aparecer en la infancia.

Trminos del glosario relacionados

ndice

Captulo 3 - Differential Diagnosis and Comorbid Conditions

Arrastrar trminos relacionados aqu

Buscar trmino

Shift work disorder

Trastorno del sueo por alteracin del ritmo circadiano (TSRC) de Tipo trabajo a

turnos segn la segunda edicin de la Clasificacin Internacional de los Trastornos del

Sueo (ICSD-2 [Westchester; 2005]) de la Academia Americana de Medicina del

Sueo, o Trastorno del sueo por horarios cambiantes de trabajo.

Este TSRC se produce cuando el horario laboral se solapa con el periodo de sueo

habitual para el trabajador y no consigue adaptar su ritmo biolgico a este horario de

vigilia-sueo que, debido a sus circunstancias laborales, debe seguir [Lu et al; 2006,

Martinez et al; 2010,Waage et al; 2009].

Puede darse en trabajos con guardias nocturnas ocasionales, turnos rotatorios, horario

fijo nocturno y aquellos que empiezan muy temprano por las maanas (antes de las 6

a.m.) [Barion et al; 2007,Sack et al; 2007].

Trminos del glosario relacionados

ndice

Captulo 2 - Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders

Arrastrar trminos relacionados aqu

Buscar trmino

Zeitgebers

The four most important time givers:

! The light (and thus the rising hour) controls the melatonin secretion. It is

proven that the exposure to light has an arousing effect and an influence on the sleep

rhythms. Phototherapy has shown its efficiency in a large number of pathologies

(insomnia, depression, fibromyalgia...).

! Physical exercice has a significant influence on the body temperature. The

warmer the organism was during the day, the stronger becomes the action of

melatonin on the fall of body temperature in the evening. Endurance sports (walking,

jogging, swimming, ski...) are traditionally associated with a deeper sleep.(Cf.) On the

opposite, it is not advised to practice an intensive sport less than three hours before

going to sleep.

Be careful, that advice for insomniacs must not lead the sick people to stop all activity

too early in the evening, like some bad sleepers do who "wait for the train of sleep"

from 9 PM on and hope to find sleep in trying not to do anything.

! The meal hours influence the brain through hormones that have been

discovered quite recently like the hypocretin/orexin (which has a common action in

the food intake behaviors and the circuits of sleep).

! Social contacts, love, laughter and pleasure also play a role that is not to

be neglected in the synchronization of the sleep rythms.

These new "somnications" are rarely the subject of specific scientific studies but some

observations suggest their importance.

In 1532, Rabelais already asserted very opportunely that "The cheerful always recover"

The pleasures of life are often associated with a short and efficient sleep whereas

"clinophilia" (the need to lie down), in which the tired subjects seek shelter, prolonges

the sleep duration but diminishes the slow wave activity, thus making the sensation of

tiredness even worse. (Cf. "hypo-sleep syndrome) Besides, it is known that (like in

cases of forced bed rest), the sudden decrease of activity induces sleep disturbances

and functional disorders very quickly.

Trminos del glosario relacionados

ndice

Captulo 3 - Sin ttulo

Arrastrar trminos relacionados aqu

Buscar trmino

Вам также может понравиться

- Biological RhythmsДокумент4 страницыBiological RhythmsMarco Alfieri100% (1)

- On Circadian RhythmsДокумент65 страницOn Circadian RhythmsDipti100% (1)

- Circadian RhythmsДокумент2 страницыCircadian RhythmsOmar SalehОценок пока нет

- Treatment of Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders With LightДокумент8 страницTreatment of Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders With LightshibutaОценок пока нет

- The Circadian Code Health Assessment PDFДокумент3 страницыThe Circadian Code Health Assessment PDFPablo Padilla MuñozОценок пока нет

- Circadian RhythmsДокумент6 страницCircadian Rhythmshafsa111100% (1)

- Primary Symptoms of Night Eating Syndrome AreДокумент3 страницыPrimary Symptoms of Night Eating Syndrome AreAisa Shane100% (1)

- Circadian Rhythms: Altered States of Awareness What Is An Altered State of Awareness?Документ1 страницаCircadian Rhythms: Altered States of Awareness What Is An Altered State of Awareness?api-461452779Оценок пока нет

- Human Biological ClockДокумент8 страницHuman Biological ClockShehani Liyanage100% (1)

- The Power of A Good SleepДокумент28 страницThe Power of A Good SleepJose PradoОценок пока нет

- Sulforaphane Q & AДокумент7 страницSulforaphane Q & AuL7iMaОценок пока нет

- Book About Cfs Titel Magical-Medicine Source Quelle Www-meactionuk-Org-uk) Magical-medicine-PDF Date 24-February-2010Документ442 страницыBook About Cfs Titel Magical-Medicine Source Quelle Www-meactionuk-Org-uk) Magical-medicine-PDF Date 24-February-2010xmrvОценок пока нет

- Molecular Biology of Circadian Rhythms PDFДокумент286 страницMolecular Biology of Circadian Rhythms PDFSupratik Chakraborty100% (1)

- What Is Functional NeurologyДокумент2 страницыWhat Is Functional NeurologydrtimadamsОценок пока нет

- 0 Tips For Deep, Rejuvenating, Age-Reversing SleepДокумент7 страниц0 Tips For Deep, Rejuvenating, Age-Reversing SleepFlori MarcociОценок пока нет

- SleepДокумент78 страницSleepbiswajitsinha100% (4)

- How The Circadian Rhythm Affects Sleep Wakefulness and Overall HealthДокумент62 страницыHow The Circadian Rhythm Affects Sleep Wakefulness and Overall HealthSlavicaОценок пока нет

- Circadian RhythmДокумент5 страницCircadian Rhythmapi-253459532Оценок пока нет

- Sleep Wake CycleДокумент27 страницSleep Wake CycleNadina TintiucОценок пока нет

- Circadian RhythmsДокумент10 страницCircadian RhythmsJerome Ysrael EОценок пока нет

- The Circadian RhythmsДокумент1 страницаThe Circadian RhythmsUrielОценок пока нет

- Biological Clock Control of Glucose Meta PDFДокумент28 страницBiological Clock Control of Glucose Meta PDFpradeep pОценок пока нет

- Chrono NutritionДокумент8 страницChrono NutritionLoona LuОценок пока нет

- Endo & Exogenous Pacemakersin Biological RhythmsДокумент2 страницыEndo & Exogenous Pacemakersin Biological RhythmsMiss_M90Оценок пока нет

- Biological Clock: Biology Department Birla Public School, Doha-QatarДокумент11 страницBiological Clock: Biology Department Birla Public School, Doha-QatarShreya BalajiОценок пока нет

- How Sleep & Nutrition Interact - Sigma NutritionДокумент16 страницHow Sleep & Nutrition Interact - Sigma NutritionJpwilderОценок пока нет

- Discuss The Role Played by Endogenous Pacemakers and Exogenous Zeitgebers in Biological RhythmsДокумент3 страницыDiscuss The Role Played by Endogenous Pacemakers and Exogenous Zeitgebers in Biological RhythmsiaindownerОценок пока нет

- Review Article: The Impact of Sleep and Circadian Disturbance On Hormones and MetabolismДокумент10 страницReview Article: The Impact of Sleep and Circadian Disturbance On Hormones and MetabolismRENTI NOVITAОценок пока нет

- Do All Animals Sleep?: Jerome M. SiegelДокумент6 страницDo All Animals Sleep?: Jerome M. Siegelantoni_gamundi3942Оценок пока нет

- 5 - Gerer Le Jet LagДокумент8 страниц5 - Gerer Le Jet LagRimaTresnawatiОценок пока нет

- Psychology: Unit 3: Biorhythms, Aggression, RelationshipsДокумент16 страницPsychology: Unit 3: Biorhythms, Aggression, RelationshipsRimi_xОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Sleep On Gastrointestinal Functioning (ERGE y Dormir) PDFДокумент9 страницThe Effect of Sleep On Gastrointestinal Functioning (ERGE y Dormir) PDFAlejo RiveraОценок пока нет

- The Visually ImpairedДокумент21 страницаThe Visually ImpairedAnanthi balaОценок пока нет

- Circadian Rhythms - BB VerДокумент90 страницCircadian Rhythms - BB VerAlejandro CallanaupaОценок пока нет

- Final Paper-Turn In1Документ12 страницFinal Paper-Turn In1api-272378934Оценок пока нет

- 1 Circadian Rhythms in Attention, 2019Документ12 страниц1 Circadian Rhythms in Attention, 2019miryam25almaОценок пока нет

- Circadian Rhythm: Effect of Circadian DisruptionДокумент9 страницCircadian Rhythm: Effect of Circadian DisruptionJoshua MarkosОценок пока нет

- Chrononutrition: Summary Well-Regulated Eating Habits Are Said To Be Important For Health. A MajorДокумент3 страницыChrononutrition: Summary Well-Regulated Eating Habits Are Said To Be Important For Health. A MajorFranklin Howley-Dumit SerulleОценок пока нет

- The Relationship Between Sleep Disturbances and DiabetesДокумент15 страницThe Relationship Between Sleep Disturbances and Diabeteskarar.hasan2000Оценок пока нет

- Biological Rhythms With Respect To EndocrinologyДокумент6 страницBiological Rhythms With Respect To EndocrinologyTehseen KhanОценок пока нет

- Effects of Age On Circadian RhythmДокумент4 страницыEffects of Age On Circadian RhythmJulie AmalaОценок пока нет

- SLEEPДокумент19 страницSLEEPRegimae BartolomeОценок пока нет

- Circardian RhythmДокумент15 страницCircardian RhythmGopika SОценок пока нет

- Sleep and Dreams Booklet 1Документ36 страницSleep and Dreams Booklet 1joffriennetriolОценок пока нет

- Outline and Evaluate Infradian And/or Ultradian Rhythms (16 Marks)Документ2 страницыOutline and Evaluate Infradian And/or Ultradian Rhythms (16 Marks)HumaОценок пока нет

- Animal Behavior Biological RhythmsДокумент3 страницыAnimal Behavior Biological RhythmsAlok PatraОценок пока нет

- Assignment of EndocrinologyДокумент12 страницAssignment of EndocrinologySaba RiazОценок пока нет

- CircadianДокумент3 страницыCircadianPrernaОценок пока нет

- Daily Rhythms of The Sleep-Wake Cycle: Review Open AccessДокумент14 страницDaily Rhythms of The Sleep-Wake Cycle: Review Open AccessCintya RambuОценок пока нет

- Sleep N Wake DisorderДокумент55 страницSleep N Wake DisorderFUN FLARE SHADOWОценок пока нет

- Term Paper On Circadian RhythmsДокумент8 страницTerm Paper On Circadian Rhythmsaflspfdov100% (1)

- Heavy Sleepers: SleepДокумент2 страницыHeavy Sleepers: SleepPatrickReisingerОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Sleep On Gastrointestinal FunctioningДокумент9 страницThe Effect of Sleep On Gastrointestinal FunctioningMércia FiuzaОценок пока нет

- Sleep and WakingДокумент36 страницSleep and WakingPayal MulaniОценок пока нет

- Thesis LiewДокумент29 страницThesis Liewfpm5948Оценок пока нет

- Sleep and Circadian Rhythms: Key Components in The Regulation of Energy MetabolismДокумент10 страницSleep and Circadian Rhythms: Key Components in The Regulation of Energy MetabolismAacg MeryendОценок пока нет

- Sexual Dimorphism in Body ClocksДокумент3 страницыSexual Dimorphism in Body ClocksDjinОценок пока нет

- Circadian RhythmДокумент65 страницCircadian RhythmDipti PunjalОценок пока нет

- Wal Jee 2018Документ2 страницыWal Jee 2018Rosemarie FritschОценок пока нет

- Utilizing The DSM-5 Anxious Distress Specifier To Develop Treatment Strategies For Patients With Major Depressive DisorderДокумент12 страницUtilizing The DSM-5 Anxious Distress Specifier To Develop Treatment Strategies For Patients With Major Depressive DisorderRosemarie FritschОценок пока нет

- PDFДокумент532 страницыPDFRosemarie FritschОценок пока нет

- Reference Subjects Age (Yr) Gender (% F) Baseline HAM D 17 / Madrs Study Design OutcomesДокумент8 страницReference Subjects Age (Yr) Gender (% F) Baseline HAM D 17 / Madrs Study Design OutcomesRosemarie FritschОценок пока нет

- Safety and Efficacy of Lorcaserin: A Combined Analysis of The BLOOM and BLOSSOM TrialsДокумент12 страницSafety and Efficacy of Lorcaserin: A Combined Analysis of The BLOOM and BLOSSOM TrialsRosemarie FritschОценок пока нет

- Adult 22q11 Study - UCLAДокумент1 страницаAdult 22q11 Study - UCLARosemarie FritschОценок пока нет

- Teachers & Carers Guide PDFДокумент11 страницTeachers & Carers Guide PDFRosemarie FritschОценок пока нет

- Update On ParasomniasДокумент8 страницUpdate On ParasomniasRosemarie FritschОценок пока нет

- BIPOLAR DEPRESSION A Comprehensive Guide El MallakhДокумент278 страницBIPOLAR DEPRESSION A Comprehensive Guide El MallakhRosemarie Fritsch100% (3)

- Effect of Sleep Deprivation On College Students' Academic PerformanceДокумент10 страницEffect of Sleep Deprivation On College Students' Academic PerformanceVirgil Viral Shah0% (1)

- Best Practices of Dave ElmanДокумент2 страницыBest Practices of Dave ElmanEliferion100% (4)

- Relax Release and Dream OnДокумент3 страницыRelax Release and Dream OnKing GeorgeОценок пока нет

- All About Sleep LISTO InglesДокумент6 страницAll About Sleep LISTO InglesMeisson CabreraОценок пока нет

- A Brief History of Sleep ResearchДокумент3 страницыA Brief History of Sleep ResearchAleh ValençaОценок пока нет

- Black Book of Forbidden Knowledge - Lucid DreamingДокумент11 страницBlack Book of Forbidden Knowledge - Lucid Dreamingorakuldragyn83% (30)

- Idiopathic Hypersomnia Its All in Their HeadДокумент2 страницыIdiopathic Hypersomnia Its All in Their HeadSambo Pembasmi LemakОценок пока нет

- End The Insomnia Struggle - A Step-by-Step Guide To Help You Get To Sleep and Stay Asleep PDFДокумент234 страницыEnd The Insomnia Struggle - A Step-by-Step Guide To Help You Get To Sleep and Stay Asleep PDFBella Donna100% (1)

- Prevalence of Sleep Disorder Among Dental Students - A PDFДокумент8 страницPrevalence of Sleep Disorder Among Dental Students - A PDFSara VegaОценок пока нет

- Classification ParagraphДокумент2 страницыClassification ParagraphPamela MarquezОценок пока нет

- Sleep ParalysisДокумент7 страницSleep ParalysisAireeseОценок пока нет

- Sleep Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Deepti Shenoi MDДокумент50 страницSleep Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Deepti Shenoi MDCitra Sukri Sugesti100% (1)