Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Vogel and Inference To The Best Explanation

Загружено:

Justin HorkyОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Vogel and Inference To The Best Explanation

Загружено:

Justin HorkyАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Justin Horky

Epistemology

Second Paper

Vogel & Inference to the Best Explanation In his paper "The Refutation of Skepticism," Jonathan Vogel attempts to refute skepticism about the external world of material objects by arguing that we are justified in inferring the existence of such a world from our sensory perceptions because such a world is the best explanation for these perceptions and because this mode of inference, the 'inference to the best explanation,' is a justified form of inference. In this paper, I will explain Vogel's theory of justification and how it justifies belief in an external, material world and then explain how these views relate to Agrippa's Trilemma of justification. Finally, I will offer a Kantian-inspired critique of Vogel's arguments. Vogel begins his paper by outlining the challenge that skepticism poses to our common-sense belief that we know many things about the world that we live in thanks to our sensory perception. The basic challenge is that, according to skepticism, one explanation for our sensory perceptions is that these perceptions are indeed caused by an external world of material objects; however, another explanation is that these perceptions could be the result of some massive sensory deception which tricks us into having perceptions of material objects which are not truly there. Furthermore, we have no grounds for favoring one of these hypotheses over the other and hence no grounds for believing that there really is a material world or, even if there is such a world, that it is structured and arranged as our senses portray it. As Vogel puts it: "[According to the 'Underdetermination Principle] [i]f Q is a competitor to p, then a subject S can know p only if p has more epistemic merit (for S) than q" (pg. 108). The skeptic wants to argue that our common-sense beliefs about the world are underdetermined because we have no grounds for affirming them instead of the hypothesis of sensory deception. Vogel wants to refute this argument by showing that our beliefs are not in fact underdetermined, and he wants to argue that this is because our move from our sensory perceptions to the belief that there is an external, material world that is arranged as portrayed by those perceptions is justified by inference to the best explanation (IBE). Vogel explains this mode of inference as follows: "[W]hen one is choosing between competing candidates for belief A and B, one has good reason to accept A rather than B if

A provides a better explanation of a relevant body of facts than B does" (pg. 110). The relevant body of facts here, of course, is our sensory perceptions, e.g. the fact that you are currently perceiving a sheet of paper. According to Vogel, skeptical hypotheses are not able to explain these facts as adequately as the hypothesis of a world that really is arranged as these perceptions indicate, and thus the Real World Hypothesis (RWH) is not underdetermined after all - we do in fact have a reason for favoring it over the various skeptical hypotheses that attempt to provide alternative explanations. To flesh this out in greater detail, Vogel then goes to work setting out in greater detail the various skeptical hypotheses that can rival the RWH so that we can see why IBE favors the RWH over them. According to Vogel, there are two different possible construals of the skeptical position, what he calls the 'Minimal Skeptical Hypothesis' (MSH) and the 'Isomorphic Skeptical Hypothesis' (ISH). The MSH is, as its name implies, a skeptical hypothesis that is very minimal in structure and content, such as, for example, the hypothesis that our sensory perceptions are deceiving us because they are being caused, not by a world arranged as these perceptions indicate, but rather by an evil demon. The problem with this kind of hypothesis should be obvious - it doesn't really provide any explanation at all for the fact that I am having the perceptions I am having; or, at the very least, it leaves much more unexplained than the RWH. This is not to say that the RWH leaves nothing unexplained whatsoever because it actually does. The RWH on its own is unable to account for the age old problem of trying to understand how its is possible for material objects to generate the immaterial, mental representations of these objects which reside in our immaterial minds, e.g. how is it possible for material and immaterial objects to interact with one another?i The 'Demon Hypothesis' perhaps gets around this problem by simply denying the existence of material substances altogether, but it then faces even more layers of explanation which need to be surmounted. For example, "Why is the evil demon so concerned with tricking us? How exactly does the demon cause these sensory perceptions to exist in our minds? Where does this power come from?" and so on. Vogel's point here is that even though the RWH may not explain everything, it still offers more explanation than the MSH and so fairs better under the principle of IBE. As Vogel puts it, "The putative explanations [the MSH] offers are impoverished and ad hoc. According to the MSH, it appears to you that Z because

something causes it to appear to you falsely that Z. That is like explaining that you fell asleep because of the action of something with a dormitive virtue..." (pg. 111). More worrying is the ISH, which is a skeptical hypothesis that is more substantive in nature. This hypothesis essentially latches onto and subverts the RWH by conceding that the background 'nexus of causes and regularities' posited by the RWH does in fact exist and then goes on to argue that it is possible that within this system there is a subsystem that harnesses that causal and regularity structure to set up a deceptive scheme that tricks the viewer into believing that there exists an arrangement of material objects which does not actually exist: "In fact, it seems that the skeptic could take over the causal-explanatory structure of the RWH, but substitute within it reference to objects and properties other than the ones we take to be real" (pg. 111) For example, if I perceive myself throwing a stone off of a bridge into a river, it is possible that there is no material stone, bridge or river but rather that these are simulations which are stored within a computer as files, such that they really do exist, but not as the material objects which I perceive them to be. Because the ISH posits the same causal system as the RWH, and is thus structurally identical with it, but then goes on to argue that within this system there is still room for a deceptive scheme that uses this wider structure to generate a simulation of that structure - a la a computer program coded to mimic the effects of the real world neither the RWH nor the ISH enjoy a level of explanatory fullness over one another. Vogel's objection against the ISH is that it lacks a simplicity which the RWH enjoys. Although the ISH utilizes the same spatiotemporal regularity and causal structure as the RWH, it wants to be a genuine competitor to the RWH as an explanation for our perception of material objects located in space; hence, it needs to use the same spatiotemporal structure which the RWH assumes in order to explain how it is possible for us to experience pseudo-objects which are not actually spatial in nature. And this, Vogel contends, is incredibly complex and inelegant as compared to the RWH's explanation that the reason for why we experience objects in space is because they really are in space. Compared to this, the ISH needs to argue that the (pseudo-)objects of our perception obey the a priori laws of space - such as, e.g. the law that a cube does not become a sphere as our perspective of it changes or the law that two different objects cannot be in the same place at the same time - because they have been written with an

incredibly complex code to make them simulate such laws, not because they are genuinely spatial objects which must, of their nature, therefore obey them: "[T]here is a natural impression that a good explanation for why X behaves like something that is F is that X is, indeed, F. An explanation of why something that isn't F nevertheless behaves as though it were F seems bound to involve greater complications...Even though the ISH is supposed to share the structure of the RWH...the ISH is required to explain the character of our experience as successfully as the RWH does, while positing a very different disposition of matter in space." (pg. 112). The ISH thus lacks the explanatory simplicity of the RWH. In order to arrive at an explanation of the same facts that the RWH accounts for, it must use a much more complex scheme of explanation that postulates the existence of a greater number of entities, and this violates Occam's Razor. If two explanations fully account for the same facts but are unequal in simplicity and entities postulated as explanatory corollaries, the simpler one which utilizes fewer such corollaries constitutes a better explanation and is thus favored by the mode of inference to the best explanation. Hence, because of the IBE, the RWH is not underdetiermined against either the MSH or the ISH and there are no skeptical hypotheses that are able to give a level of explanatory fullness for our perceptions that do not also share the same structure as that used by the RWH - or, at the very least, the skeptic needs to flesh out such a hypothesis before it can be taken seriously. Hence, because the only availbale skeptical hypotheses are either explanatorily unsatisfactory or structurally too complex vis--vis the RWH, the IBE justifies our belief in an external world that is arranged as we perceive it. This leads us to the Agrippan Trilemma, an ancient argument that has been used to try to demonstrate that no beliefs whatsoever can be justified. According to this trilemma, there are only three ways to try to justify a belief, but all three fail. The first way is foundationalism, i.e. the attempt to ground ones beliefs in some fundamental belief or proposition which itself needs no justification or which somehow justifies itself; the second is coherentism, i.e. the attempt to ground ones beliefs in a web of beliefs which come together to justify one another so that they succeed in holding themselves up as a group; and the third is infinitism, i.e. the position that a belief can be grounded in another belief, which can be explained by another and so on ad infinitum. All three of these attempts at justification fail, the skeptic argues, because they either rely upon

dogmatically asserting a belief that itself has no real grounds for justification (foundationalism), because they involve circular reasoning (coherentism) or because, due to the fact that there is no end to the chain of inferences, there is no ultimate explanation and hence every link in the chain is itself thus unjustified (infinitism). Vogel wants to argue that IBE justifies the belief that our perceptions are accurate. But what justifies the principle of IBE? It is clear that the IBE cannot be justified a posteriori because it is a mode of inference which we use when reasoning about our experiences; hence, it cannot be derived from them. Furthermore, the proposition that 'one should always believe the explanation which most adequately and simply accounts for the facts' carries with it a sort of necessity (and normativity) which the process of induction could never justify. Hence, the principle of IBE must be a priori in nature. And Vogel, in his discussion of 'Fumerton's Requirement,' implies that a priori modes of inference, if they are to ever be justified, must have some sort of intrinsic justification in and of themselves if we are to avoid Carroll's Tortoise and Achilles dilemma. Hence, Vogel appears to be a foundationalist who argues that our belief that there exists a world arranged as our perceptions portray it is justified via IBE as an explanation for those perceptions and that the principle of IBE is intrinsically and a priori justified. At this point, I now wish to level a criticism against Vogel's argument. Kant, in the Critique of Pure Reason and elsewhere, had argued that all metaphysical propositions, i.e. propositions which are simultaneously synthetic and a priori, must receive their a priori justification due to the fact that the subject's mind has been structured such that the propositions hold for all experiences which that subject has. Kant's argument was as follows: an a priori proposition, such as 'every object of experience must be spatiotemporal,' can never receive its justification from experience because induction can never justify the universality and necessity which such propositions lay claim to. For example, even if you have only ever seen and heard of white swans, from which you inductively conclude that all swans are white, it is still fully possible for you to conceive of black swans. Hence, the inductively justified proposition 'all swans are white,' has no real claim to universality or necessity. But we acknowledge that the proposition 'all objects of experience must be spatiotemporal,' really is true in the

full-blooded sense that every object of experience is spatiotemporal and it is not possible for such objects to be otherwise. Because this proposition cannot be justified by experience of external objects, the explanation for the justification of such a proposition must lie at the other end of the subject-object dichotomy; i.e. it must be true for the subject because this is the very way the subject's mind is structured so that all experiences which that subject has must conform to it. According to Kant, a priori propositions are justified a priori and are true by virtue of the fact that there are various subjective, transcendental pre-conditions for experience which our minds apply to all sensations that we receive from independently existing objects, resulting in the phenomenological appearances of our experience which must, as a result of this form of genesis, always conform to such conditions. Hence, the reason for why the proposition 'all objects of experience must be spatiotemporal' is true is because space and time are modes of intuition which our minds apply to the sensations we receive from all objects, rather than aspects of things-in-themselves. If Kant's theory of the a priori is true, and if it is the case that the principle of IBE is ultimately justified a priori, then it must be the case that the reason for why this rule of inference is justified a priori is because our minds are constructed such that they themselves apply this rule to our intuitions. It is in essence, an a priori concept which exists as a part of the subject's mental structure.ii This being the case then, it would not actually have a jurisdiction in application when it comes to reasoning about the nature of things-in-themselves, because such entities exist independently of the subject and hence independently of the subjective, a priori concepts and modes of intuition which are used by the subject's mind to make experience possible.iii Hence, we have no right to apply the principle of IBE when we are reasoning about things-in-themselves, although we can use it when reasoning about things-as-they-appear-to-us. The question here then is whether this restricted domain of jurisdiction for the principle of IBE is still good enough to defeat the skeptic. In order to defeat the skeptic, at least as Vogel interprets him, then we need to show that we are justified in believing that our perceptions accurately portray a world of material objects. Can Vogel still do this if the principle of IBE only legitimately applies to appearances? This question is complicated by the fact that Kant seems to have wanted to posit appearances as a sort of

intermediary between us and things-in-themselves, such that they are not entirely subjective in nature. Rather, unlike the thing-in-itself, which exists independently of us and is entirely objective in nature, and unlike our entirely subjective conceptions of objects, such as the feelings that well up within us when we think of certain objects, these appearances or 'phenomena' are a mixture of the objective and subjective because they arise as a result of objectively existing sensations caused by things-in-themselves uniting with our subjectively existing modes of intuition and a priori concepts to result in the appearance that is the actual object of our perception and experience. Hence, even though the appearance is a personal, phenomenological event, it nevertheless enjoys a sort of inter-subjective existence as well insofar as, if you were to receive the same sensations which I do, you would experience the same phenomena because your mind uses the same subjective modes of intuition and a priori concepts that my mind does. Could Vogel thus argue that our ability to use the principle of IBE when reasoning about these appearances is enough to justify that the entirely subjective thoughts in our mind accurately represent a real, inter-subjective world (the appearances) which is material in nature? No, he cannot. The reason for this is because the appearances are not spatial or material in nature; they are phenomenological phenomena. Nor is it the case that our entirely subjective concepts are trying to represent these phenomena; they are just the feelings or ideas which we happen to associate with the object of experience that the appearance constitutes. The appearance itself is the sensory perception which we are concerned with when considering whether or not our sensory perceptions accurately portray the world. To make things simpler, consider Hume, who also wondered whether his perceptions accurately represented the world. Because Hume's sensory organs were (reasonably) similar to our own, his perception of an object would have been the same as ours if we were to perceive the same object, although, of course, his entirely subjective associations with such perceptions would have differed. But does this fact of inter-subjectivity with regards to these perceptions (i.e. these 'appearances' or 'phenomena') therefore defeat Humean skepticism? Hardly. Hence, although Vogel has provided an interesting argument here, I believe that this argument, given the nature of the a priori, ultimately founders upon Kantian skepticism regarding the nature of things-in-themselves.

One could try to get around this problem by opting for materialism, but then one gets into the even more impossible issues of trying to explain how it is possible for matter to give rise to self-consciousness, the intentionality that is present in thoughts and so-called sensory 'qualia.'

ii

Given Kant's theory of the a priori, the term 'a priori,' in addition to meaning 'justified independently of experience,' pulls double duty as a synonym for 'originates within the subject.'

iii

In this sense, Kant almost seems to have a psychologistic understanding of the nature of logic and the modes of inference (insofar as they are a priori), albeit with a metaphysical spin to it.

Вам также может понравиться

- Vogel On Cartesian SkepticimДокумент4 страницыVogel On Cartesian SkepticimcofiОценок пока нет

- The Theory of EvidenceДокумент5 страницThe Theory of EvidenceLukas NabergallОценок пока нет

- Dialnet TheArgumentFromIllusionReconsidered 4004123Документ7 страницDialnet TheArgumentFromIllusionReconsidered 4004123hyukabreadОценок пока нет

- A Defense of The Given PDFДокумент4 страницыA Defense of The Given PDFuzzituziiОценок пока нет

- Is The World in The Brain or The Brain I PDFДокумент7 страницIs The World in The Brain or The Brain I PDFbia shampooОценок пока нет

- Angels NeedleДокумент29 страницAngels NeedleSantiago FrancoОценок пока нет

- The Will to Power - An Attempted Transvaluation of All Values - Vol II Books III and IVОт EverandThe Will to Power - An Attempted Transvaluation of All Values - Vol II Books III and IVРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (4)

- LORENZ B. PUNTEL, Truth, Sentential Non-Composiotionality, and OntologyДокумент40 страницLORENZ B. PUNTEL, Truth, Sentential Non-Composiotionality, and OntologyfalsifikatorОценок пока нет

- Epistemic Relativism: Mark Eli Kalderon November 22, 2006Документ13 страницEpistemic Relativism: Mark Eli Kalderon November 22, 2006Carolina MircinОценок пока нет

- Réfutation Du Kalam ArgumentДокумент5 страницRéfutation Du Kalam Argumentoumar SYLLAОценок пока нет

- Why Is There Anything at All by Van Inwagen Peter Z-LiborgДокумент28 страницWhy Is There Anything at All by Van Inwagen Peter Z-LiborgscriblarsОценок пока нет

- Interv Entions Discussions: Phenomenological R Ealism and The Moving Image of ExperienceДокумент14 страницInterv Entions Discussions: Phenomenological R Ealism and The Moving Image of ExperienceAdam JurkiewiczОценок пока нет

- Crane (1988) - Concepts in PerceptionsДокумент5 страницCrane (1988) - Concepts in PerceptionsPippinosОценок пока нет

- Should We Expect To Feel As If We Understand Consciousness?: Mark C. PriceДокумент12 страницShould We Expect To Feel As If We Understand Consciousness?: Mark C. PriceSIRISHASIRIIОценок пока нет

- Noam Chomsky - A Reply To PiagetДокумент4 страницыNoam Chomsky - A Reply To PiagetRobyОценок пока нет

- DoweДокумент6 страницDoweRian LobatoОценок пока нет

- A Dialogic Response To An AtheistДокумент5 страницA Dialogic Response To An AtheistAggelos ChiotisОценок пока нет

- Rowe Ac and PSR PDFДокумент15 страницRowe Ac and PSR PDFHobbes20Оценок пока нет

- Lecture Notes #04Документ4 страницыLecture Notes #04Boram LeeОценок пока нет

- Nozick, Robert. Knowledge and SkepticismДокумент16 страницNozick, Robert. Knowledge and SkepticismViktor VangelovОценок пока нет

- Refutation Argument KalamДокумент6 страницRefutation Argument Kalamoumar SYLLAОценок пока нет

- Locke Empirical KnowledgeДокумент21 страницаLocke Empirical KnowledgeRichardo ManahanОценок пока нет

- Stewart-Rethinking The Subject Matter of ProtometaphysicsДокумент26 страницStewart-Rethinking The Subject Matter of ProtometaphysicsAnonymous LnTsz7cpОценок пока нет

- No Z Ick Phil ReadingДокумент16 страницNo Z Ick Phil ReadingThangneihsialОценок пока нет

- J. Toribio (2007) - Nonconceptual Content'. Philosophy Compass 23 445-460.Документ16 страницJ. Toribio (2007) - Nonconceptual Content'. Philosophy Compass 23 445-460.David LopezОценок пока нет

- Broad 1914 Review Arnold Ruge AДокумент4 страницыBroad 1914 Review Arnold Ruge AStamnumОценок пока нет

- Why Is There Anything at All? 101Документ1 страницаWhy Is There Anything at All? 101CherryОценок пока нет

- Ferraris2015 TrascendentalДокумент18 страницFerraris2015 TrascendentalRodrigo CarcamoОценок пока нет

- Gennaro Chierchia (1989) Anaphora and Attitude de SeДокумент29 страницGennaro Chierchia (1989) Anaphora and Attitude de SejacoporomoliОценок пока нет

- Nietzsche's PositivismДокумент43 страницыNietzsche's Positivismgerti09Оценок пока нет

- Broad 1914 Review Proceedings AristotelianДокумент3 страницыBroad 1914 Review Proceedings AristotelianStamnumОценок пока нет

- The Riddle of ExistenceДокумент43 страницыThe Riddle of Existenceenvcee100% (1)

- On Leibnizs Cosmological ArgumentДокумент9 страницOn Leibnizs Cosmological Argumentapi-662463700Оценок пока нет

- 701 800Документ116 страниц701 800readingsbyautumnОценок пока нет

- Nietzsches PositivismДокумент43 страницыNietzsches PositivismJorgeDiazОценок пока нет

- Sosa, Ernest, Rational Intuition Bealer On Its Nature and Epistemic StatusДокумент12 страницSosa, Ernest, Rational Intuition Bealer On Its Nature and Epistemic StatusTiaraju Molina AndreazzaОценок пока нет

- Armstrong 1991Документ11 страницArmstrong 1991rkasturiОценок пока нет

- Knowledge and ScepticismДокумент15 страницKnowledge and ScepticismJuan IslasОценок пока нет

- Ex Nihilo Nihil FitДокумент11 страницEx Nihilo Nihil Fitlarry14_grace1231Оценок пока нет

- An Intuitionistic Way to Ultimate Reality: Unlocking the Mysteries of Man and His UniverseОт EverandAn Intuitionistic Way to Ultimate Reality: Unlocking the Mysteries of Man and His UniverseОценок пока нет

- Subjectivity Objectivity and Frames of R PDFДокумент49 страницSubjectivity Objectivity and Frames of R PDFCarlos Orlando Wilches GuzmánОценок пока нет

- GroundcauseДокумент52 страницыGroundcauseRaúl SánchezОценок пока нет

- Positism in Contemporary EpistemologyДокумент15 страницPositism in Contemporary EpistemologyRyan HedrichОценок пока нет

- Bernardo Kastrup - A Rational, Empirical Case For Postmortem Survival Based Solely On Mainstream ScienceДокумент63 страницыBernardo Kastrup - A Rational, Empirical Case For Postmortem Survival Based Solely On Mainstream Sciencedick_henrique100% (1)

- Subjectivity, Objectivity and Frames of Reference in Evans's Theory of ThoughtДокумент36 страницSubjectivity, Objectivity and Frames of Reference in Evans's Theory of ThoughtjaardilaqОценок пока нет

- Jeremy Walker Mcgill UniversityДокумент20 страницJeremy Walker Mcgill UniversityNOEОценок пока нет

- The Meaning of Saphêneia in Plato's Divided LineДокумент30 страницThe Meaning of Saphêneia in Plato's Divided LineSantiago Rojas QuijanoОценок пока нет

- Spring 2010 Final PrintДокумент31 страницаSpring 2010 Final PrintEnquiryPhilosophyОценок пока нет

- Metaphysical RealismДокумент6 страницMetaphysical RealismSamson LeeОценок пока нет

- Hegeler InstituteДокумент6 страницHegeler InstituteAlfonso RomeroОценок пока нет

- Locke and Van Fraassen On UnobservablesДокумент5 страницLocke and Van Fraassen On UnobservablesRemko Van der PluijmОценок пока нет

- Yandell Faithphil 1995Документ19 страницYandell Faithphil 1995Lior NirОценок пока нет

- Weltanschauung Which Renders The Twisted Structure of Our Reality Intelligible. Indeed Leibniz's Theory-Or atДокумент9 страницWeltanschauung Which Renders The Twisted Structure of Our Reality Intelligible. Indeed Leibniz's Theory-Or atapi-279308482Оценок пока нет

- Problems of PhilosophyДокумент6 страницProblems of PhilosophySubhendu GhoshОценок пока нет

- Aristotle: Logic: From Words Into PropositionsДокумент27 страницAristotle: Logic: From Words Into PropositionsArindam PrakashОценок пока нет

- A Priori PosterioriДокумент4 страницыA Priori Posteriorizenith492Оценок пока нет

- The Nature of Narrow ContentДокумент20 страницThe Nature of Narrow Contentdemian agustoОценок пока нет

- Responding To SkepticismДокумент26 страницResponding To SkepticismLookinglass1Оценок пока нет

- Councils and ParliamentsДокумент41 страницаCouncils and ParliamentsJustin HorkyОценок пока нет

- Emmanuel - Unequal ExchangeДокумент496 страницEmmanuel - Unequal ExchangeJustin Horky100% (2)

- Aristotle's Physis and Modern PhysicsДокумент19 страницAristotle's Physis and Modern PhysicsJustin HorkyОценок пока нет

- Bernstein - Preconditions of Socialism PDFДокумент265 страницBernstein - Preconditions of Socialism PDFJustin HorkyОценок пока нет

- Fischer - Schellings Lehre PDFДокумент874 страницыFischer - Schellings Lehre PDFJustin HorkyОценок пока нет

- An Analysis of Fichte's 'Introductions To The Wissenschaftslehre.'Документ7 страницAn Analysis of Fichte's 'Introductions To The Wissenschaftslehre.'Justin HorkyОценок пока нет

- Aristotle & Decision-MakingДокумент7 страницAristotle & Decision-MakingJustin HorkyОценок пока нет

- Sraffa - Production of Commodities PDFДокумент131 страницаSraffa - Production of Commodities PDFJustin HorkyОценок пока нет

- Aristotle & FriendshipДокумент5 страницAristotle & FriendshipJustin HorkyОценок пока нет

- De AnimaДокумент7 страницDe AnimaJustin HorkyОценок пока нет

- Vogel & ExternalismДокумент5 страницVogel & ExternalismJustin HorkyОценок пока нет

- AnimalismДокумент2 страницыAnimalismJustin HorkyОценок пока нет

- Descartes' Ball of WaxДокумент2 страницыDescartes' Ball of WaxJustin Horky100% (1)

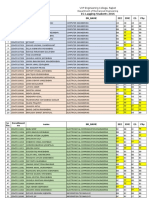

- Month - Attendance B.E FY Semester1 SectionE ELEMENTSOFMECHANICALENGG. 17EME14 PDFДокумент2 страницыMonth - Attendance B.E FY Semester1 SectionE ELEMENTSOFMECHANICALENGG. 17EME14 PDFenggsantuОценок пока нет

- Agree and Disagree Statements StrategyДокумент2 страницыAgree and Disagree Statements Strategyapi-248208787Оценок пока нет

- Deconstructing Developmental Psychology - Twenty Years OnДокумент3 страницыDeconstructing Developmental Psychology - Twenty Years OnOntologiaОценок пока нет

- CJR Baru Kel 1-1Документ4 страницыCJR Baru Kel 1-1desertfox27Оценок пока нет

- PCS 1: NaturalismДокумент22 страницыPCS 1: NaturalismBincy100% (1)

- Thompson (1990) - Ideology & Modern Culture - ExtrasДокумент64 страницыThompson (1990) - Ideology & Modern Culture - ExtrasAndreea MalancaОценок пока нет

- God and Ultimate Origins: A Novel Cosmological ArgumentДокумент211 страницGod and Ultimate Origins: A Novel Cosmological ArgumentConrad Aquilina100% (4)

- Reflection Paper Hum 2Документ4 страницыReflection Paper Hum 2Mhia DulceAmorОценок пока нет

- Nature, Scope & Importance of Philosophy of EducationДокумент47 страницNature, Scope & Importance of Philosophy of EducationHafeez UllahОценок пока нет

- 11 Data Collection and Analysis ProceduresДокумент17 страниц11 Data Collection and Analysis ProceduresCarmilleah FreyjahОценок пока нет

- Organization Case StudyДокумент2 страницыOrganization Case StudyVishlesh Pai100% (1)

- TOTA Notes IДокумент3 страницыTOTA Notes ILxranОценок пока нет

- Alexis Karpouzos - The Mathematics of ImaginationДокумент4 страницыAlexis Karpouzos - The Mathematics of ImaginationAlexis karpouzos100% (2)

- Concepts of Urban SociologyДокумент81 страницаConcepts of Urban Sociologygiljermo100% (4)

- 3a. Systems Approach To PoliticsДокумент12 страниц3a. Systems Approach To PoliticsRohit MohanОценок пока нет

- EG Lagging Students 2016Документ30 страницEG Lagging Students 2016arickОценок пока нет

- BungeДокумент6 страницBungebemerkungenОценок пока нет

- Summary EYl 10Документ3 страницыSummary EYl 10Afifah Hisyam BachmidОценок пока нет

- Piaget's Stages of Cognitive DevelopmentДокумент13 страницPiaget's Stages of Cognitive DevelopmentFarah Therese AdarnaОценок пока нет

- Alvesson & Spicer 2012 - Critical Leadership Studies - The Case For Critical PerformativityДокумент25 страницAlvesson & Spicer 2012 - Critical Leadership Studies - The Case For Critical PerformativityCristian NeiraОценок пока нет

- TFN Prelims ReviewerДокумент6 страницTFN Prelims ReviewerKeyla PedrosaОценок пока нет

- PSY1020 Foundation Psychology Essay Cover SheetДокумент7 страницPSY1020 Foundation Psychology Essay Cover SheetklediОценок пока нет

- In Defense of Pure ReasonДокумент246 страницIn Defense of Pure ReasonJacob Sparks100% (1)

- O BДокумент12 страницO BDinakara KenjoorОценок пока нет

- Cooper, M. M. (1997) - Distinguishing Critical and Post-Positivist Research.Документ7 страницCooper, M. M. (1997) - Distinguishing Critical and Post-Positivist Research.asean efОценок пока нет

- Research Proposal FormatДокумент4 страницыResearch Proposal FormatAdnan HaseebОценок пока нет

- Philosophy of Latin America PDFДокумент320 страницPhilosophy of Latin America PDFJoao100% (1)

- L. Jonathan Cohen - The Probable and The Provable-Oxford University Press, USA (1977)Документ392 страницыL. Jonathan Cohen - The Probable and The Provable-Oxford University Press, USA (1977)Giovanni Americo Bautista Pari100% (1)

- Digital Physics The Universe ComputesДокумент4 страницыDigital Physics The Universe ComputesnepherОценок пока нет