Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Book Review: Aron Nimzowitsch - On The Road To Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 - Per Skjoldager and Jørn Erik Nielsen

Загружено:

Chess India CommunityОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Book Review: Aron Nimzowitsch - On The Road To Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 - Per Skjoldager and Jørn Erik Nielsen

Загружено:

Chess India CommunityАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

In honor of its being voted the ChessCafe.

com 2012 Book of the Year, we thought it fitting to revisit the review of Aron Nimzowitsch, 18861924. Congratulations to authors Per Skjoldager and Jrn Erik Nielsen, along with publisher McFarland.

Purchases from our chess shop help keep ChessCafe.com freely accessible:

A Beautiful Legacy

by John D. Warth

Book Reviews

Aron Nimzowitsch: On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924, by Per Skjoldager and Jrn Erik Nielsen, McFarland 2012, Hardcover, 456pp. $49.95 (ChessCafe Price: $43.95) Merely opening this book might immediately raise the reader's pulse with beautiful page spreads, solid binding, and a cover that feels inviting. I couldn't wait to get my hands on a copy, both for the scholarship I knew it would contain, and for the history it was sure to reveal about chess in a bygone era. Part biography and part games collection, this compendium captures a golden age of chess culture through the life of Aron Nimzowitsch, a progressive force in the growth of twentieth century chess. Nimzowitsch's first tournaments were played in the splendor of the Edwardian age: in bustling city chess cafes and in the picturesque settings of resort hotels. He attended college, but sporadically. He would rather play chess in coffee houses. His family back in Riga were wealthy lumber merchants, but he had always dreamed of making his living at chess. For the most part, he made his living as a journalist: he was a chess columnist, a chess author, and correspondent. Sometimes he worked as a theater critic. Nimzowitsch also earned money lecturing: not just on chess, but on philosophy and other topics. His innovative chess ideas were gathered into his famous book My System. His system of play was so influential that it is still in print nearly one hundred years later.

Translate this page

Eminent Victorian Chess Players by Tim Harding

Rating Chart

Awful Poor Uneven Good Great Excellent

Chess Facts and Fables by Edward Winter

100 Best Chess Games by Andrew Soltis

Aron Nimzowitsch

Nimzowitsch was drafted at age thirty into the Russian army in 1916. After returning to Riga in 1917, he faced-down Bolshevik thugs at his family home. Soon, he left Riga to travel and follow his dreams. The family business was ruined in the turmoil of the revolution.

Later chapters describe Nimzowitsch's lecture and demonstration tours of Scandinavian cities in the early 1920s. The memoir ends soon after his final move to Denmark in 1924. Nimzowitsch's story will continue when volume two is published. Nimzowitsch was born into a beautiful but volatile era. Dynamic social and political forces shifted the cultural landscape near the end of the Edwardian age. These forces included the powder keg of European alliances that led to the Great War. Popular uprisings in his native Russia culminated in the rise of Bolshevism and usurping Romanov rule in the Russian Revolution.

Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch

Chess was changing, too through a new generation of progressive players. Old order ideas, dominated by the theories of Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch, were growing stale. His ideas had many adherents, but he was rigid about how a game of chess should be played, with no room for growth. Nimzowitsch played chess with a free-form style. He rejected Tarrasch's authority. They clashed over the board and face to face. They argued theory in European chess journals of the age. Their bitter rivalry exploded into a personal and ideological feud for the soul of the game. Through his games, his writings, and his travels, Aron Nimzowitsch inspired and challenged his peers with fresh ideas breathing life into a game often played in the haze of stale cigars. A staunch non-smoker, he brought fresh air into the playing halls by opening the doors to innovation, and bringing new moves to the table. His opening ideas rejected the fixed central pawns that Tarrasch insisted on. Nimzowitsch was innovative. He liked positions with a flexible and fluid center, and nimble pawns. Above all, he wanted to avoid rigid concepts and outdated ideas. Tarrasch, his nemesis, scoffed. He criticized Nimzowitsch. Aron had played black against Carl Schlechter in a fourth round game from the San Sebastian tournament of 1912: "1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 Nf6 Not good, since the knight is immediately driven away. But Mr. Nimzowitsch goes his own way in the opening, which, however, is not recommended to the readers . . ." from the International Schachturnier zu San Sebastian, 1912 pp. 32-34 Aron Nimzowitsch was a master-level tournament player and opening theorist. He wrote and corresponded as a chess author and journalist, and promoted chess on a lecture circuit of Scandinavian cities. His itinerary included exhibition games against multiple opponents, which meant moving pieces while shuffling from board to board for long hours without a break. All told, he played 532 games against simultaneous opponents on his 1922 Danish tour, losing just twenty-three. But he had no idea he would one day call Denmark home. Author Per Skjoldager, is a chess historian and chess book collector from Denmark. He has unearthed and compiled a wealth of information about the first part of Nimzowitsch's life that is a rare combination of comprehensiveness and readability. This may be the most thorough treatment

of Nimzowitsch and his times ever in print. But the author's work is only half finished. A second volume is planned, taking the master's life to its conclusion. This book has everything. Readers interested in early twentieth century chess will find hundreds of games to study. Stories are filled with colorful anecdotes. The book is filled with nostalgia, beauty, and atmosphere: what Germans call Zeitgeist the spirit of the times. The feel of this book is very solid, and its font is easy on the eye, and looks appropriate. Printed in the U.S. on acid-free archival stock, all pages are bound together in signatures for durability and permanence. Only the best books are still produced this way. There is far more scholarship in Skjoldager's book than the average reader might comfortably take in it is exhaustive in its research and its revelations. This is a book that will take time to read. Browsers will find something new with each flip of the page. The nuances of this book would be difficult to experience in an electronic format, although the ability to magnify much of the fine print would help. The title of this book announces the year of Aron's birth, 1886, and takes us midway through the master's life, just after he became a permanent resident of Denmark in 1923. Chapters progress chronologically, from his childhood and formative years and include details of his family's solid business and cultural background, before the war brought their prosperity to an end. The author includes details of his extensive travels, and his personal correspondence. Entries from his books and chess journalism are included, among them, examples of Nimzowitsch's writings as a newspaper chess correspondent and magazine columnist. Some outline his theories about pawn chains and other elements of chess. Other aspects of Nimzowitsch's life are found in letters and official records, family photographs, facsimiles of historic documents, game scores, postcards, 450 games and game fragments, regional maps, and chess compositions. Sketches feature tournament players in profile. Detailed indexes list opponents alphabetically, while others list openings by ECO codes, and another lists openings by name. Readers will appreciate and need these extensive indexes to navigate the enormous material encompassed in its pages. The general index alone comprises ten pages of fine print. Much has been documented about Nimzowitsch's life in chess. His father, a lumber merchant was as a master-strength player. He reluctantly taught his son the moves when he turned eight, but only after Aron's insistent urging. After a brief struggle to comprehend the moves of the men, he soon showed talent. Yet much about his early life beyond chess remained untold, particularly his formative years, 1914-1924. This book claims to be our only guide to those days. Much of what we have learned depicts Nimzowitsch as frail, thin-skinned, and eccentric. But he was also brilliant and hard-working. Aron had grown up a child of privilege, but he was immersed in turbulent times, with Bolshevik partisans pounding at the family's door with rifle butts, and once inside, rifling through drawers demanding tribute and looting their possessions.

Kurhaus spa and resort

With its huge number of games, this book could easily be mistaken as a games collection. Most notes are from the original sources and welltranslated. At times they reveal a comic naivety, as theory and times have changed. But it contains far more than that. The authors chronicle changing times, not just for chess, but for world order. Nimzowitsch's story is told in photographs and postcards that depict the atmosphere of the posh venues at which many major tournaments were then held: at Karlsbad in 1907 and 1911 (from which a stunning architectural postcard depicts the Kurhaus spa and resort), and beautiful seaside San Sebastian, Spain in 1911 and 1912, are also shown in period photographs. The prestigious talent at the tournament held at St. Petersburg in 1914 was captured in a group portrait. Nimzowitsch stands among Alekhine, Bernstein, Capablanca, Janowski, Lasker, Marshall, Rubenstein, Tarrasch, and ZnoskoBorovsky, and others. So great was their collective talent that Tzar Nicholas II pronounced them all "Grandmasters of Chess," coining the term.

St. Petersburg 1914

Though its pages are black and white, Skjoldager's account reveals a nostalgic and colorful world. Photographs and postcards of beautiful hotels and seaside resorts are scattered throughout this book, revealing vaulted ceilings and palatial architecture, bathing their interiors in softly-diffused light. Master-level chess was once a formal affair. Players wore dark suits, and peered through their pince-nez spectacles at polished chessmen on wooden boards. They examined the day's progress on chained pocket watches. Chess was a gentleman's game, played in clubs and coffee houses. But at top levels, elaborate venues reflected the majesty of the royal game. But royal or not, chess is decided by struggle. A portion of the book covers an ongoing rift between Nimzowitsch and his rival, Tarrasch. These battles, over theory were often snide or rife with vicious attacks. Each man's reputation was tied to his playing style, and those ideas clashed. Nimzowitsch tells his side of the story: ". . . I was already aware that Tarrasch was my antagonist, then I still did not feel that he was my 'born enemy.' Our relations, however, soon worsened. This is how it happened.

". . . Tarrasch granted me the honor of playing a serious game with him. My opening play was as usual most peculiar, partly because at that time, as explained earlier, I was generally ill-versed in 'positional play,' partly because I was already avoiding well worn paths, and partly because I was skeptical of the dogmas of the then dominant school. A large number of spectators were gathered even though the game was private. The audience was aware of my wealth of combinative imagination and mistakenly took this for playing strength. They expected, if not an equal game Tarrasch was then at the height of his fame then at least an interesting and eventful game. "After the 10th move, Tarrasch folded his arms across his chest and made the following spontaneous pronouncement: 'Never in my life have I had such a won game after ten moves as I have now!' The game, incidentally, ended in a draw. But for a long time I could not forgive Tarrasch for the 'insult' he inflicted on me in front of all those spectators. . . . "For the present I must say that, had it not been for a feeling of hostility towards Tarrasch, I would never have learned to play chess properly. To play stronger than Tarrasch, that was the impulse behind all my desires during the period 1904-1906. I can therefore pass the following pleasant advice to all my readers: 'If you wish to achieve results, select an arch rival and attempt to punish him by toppling him from his pedestal.' . . . "I have to add though, that is my feeling of hostility towards Tarrasch was founded in personal motives, then it was not sustained by them (from 1904 onwards, we had no further quarrels), but by that profound antagonism in the ideological area, which I had felt so strongly right from the beginning of our acquaintance. Tarrasch, to me, was always mediocrity. It is true that he was a very strong player, but all his views, his sympathies and antipathies and above all his inability to create new ideas fully proved the mediocrity of his cast of mind. I myself, who paid homage to genius, could in no way be reconciled to the fact that mediocrity should stand as the leader of the dominant school! This fact, for me, was a veritable outrage! Kak Ya Stal Grosmeystrom, pages 16-19; Claes Lofgren translation." With Tarrasch, ideas about chess theory were set and immutable. He liked a fixed center, which meant posting central pawns. Nimzowitsh represented the new order, allowing for a more fluid, changeable center not necessarily occupying it with pawns, but controlling it indirectly, often from the flanks. Bishops might be used, for example, to attack the center from the wings. These ideas are the beginnings of Nimzowitsch's Hypermodernist ideas, but years before his thoughts and those of peers had grown into what some have called a school or movement, which Skjoldager explains and contests: " . . . we would like to investigate in more detail if Nimzowitsch was the father of Hypermodernism. It is clear that he, very early on, had a different perception of the center than Tarrasch, but how should he be regarded in terms of the Hypermodern School? "The concept of Hypermodernism appears to have established itself as an institution within modern chess literature. But, although the term is frequently used and aims to describe a select group of chess masters and their ideas, little effort has been made to define the real significance of the concept. "Even the name is not used consistently. Sometimes we see Hypermodern School and sometimes Hypermodern movement. But what is the difference? Does the difference have any significance? Yes, ideally the use of the word "School" should mean that a set of new significant ideas were offered by the school's ideologists to its practitioners and followers. This is true when we look at some of the preceding schools which have been named after their ideologists, e.g., Philidor, Steinitz and Tarrasch.

"But Hypermodernism is not associated with a single player. Typically a handful of players are mentioned when we talk about the 'Great Hypermodern Masters' and it appears that Rti, Nimzowitsch, Tartakower and Breyer are among those most frequently mentioned. But they did not have a common style, they never worked out a common dictum and it appears they worked completely independently of each other. "The first time on record in which the word 'Hypemodern' is used is in an article by Alapin in Wiener Schachzeitung 1913. The article in question was written by Alapin in reply to Nimzowitsch's article Enspricht. Using the word hypermoderne in this context makes it a counterpart to moderne, i.e., Die Moderne Schachpartie versus Die hypermoderne Schachpartie. This dispute may well have created the concept of Hypermodernism as early as this and it may have been the seed that later induced Tartakower to name his famous book Die Hypermoderne Schachpartie." To my mind, the author is splitting hairs over terms here. Clearly, though, change was in the air, with these players bound by their progressive styles, whether or not they considered themselves a part of a movement or school. Tarrasch's rigid ideas were losing ground, while Nimzowitsch's challenging proposals encouraged change and experimentation, invigorating the game with innovation. Moving on to lighter things, one of the most enjoyable aspects of this book are its colorful anecdotes. For instance, at Hamburg in 1910 something quirky was about to happen, as related by Edward Lasker in Chess Secrets: "The other comedy involved Nimzowitsch and Walter John. When Nimzowitsch was scheduled to play the latter, he came forty five minutes late to the tournament hall. He had heard that John had made a derogatory remark about him, and he was going to have a little revenge. John, who had made his first move, was pacing the hall nervously, possibly hoping that Nimzowitsch might be a whole hour late. In that case, John could have claimed the game. When Nimzowitsch finally appeared, he seemed in no hurry to start the contest. Instead of sitting down at the board, he feigned intense interest in the oil paintings, which lined the walls, walking from one to another and examining them carefully, although he had been looking at them every day for two weeks. "By that time John knew, of course, that something was up, and he turned red with anger at the contemptuous nonchalance with which Nimzowitsch was treating the game. Finally Nimzowitsch came to the board, made his move without sitting down, and immediately went off again to continue his study of the paintings. This he repeated until he had played his sixteenth move, consuming probably no more than five minutes in pondering his play. "On the seventeenth move he offered a fine pawn sacrifice, which won the game nine moves later. John might as well have resigned at that point, but he was naturally furious at Nimzowitsch and he kept him playing on for eighty-two moves before he resigned. The next morning John sent two seconds to Nimzowitsch with a challenge to a duel. Nimzowitsch laughed at them and said he would gladly fight John, but only with bare fists. At the same time, he showed them his muscles and suggested they had better warn John. Of course, the duel was off [Chess Secrets, pp. 104-105]." The author states that while most of this incident is probably true, the duel threat may not have happened at all. Skjoldager researches and documents carefully and sets the record straight whenever possible. And though that is important, he sometimes does so ad nauseum. But of course, the reader determines when he or she has had enough and is free to move on when things get tedious.

It can be of benefit to know a little German. For many it won't matter, but the names of many of the periodicals mentioned are usually left untranslated. Not everyone will care that Wiener Schachzeitung means Vienna Chess Newspaper. This book is a benchmark of biographical and historical chess research. It captures the spirit of changing times, and honors a grandmaster of chess through his thoughts, words, and games. This book is his legacy. Skjoldager and Nielsen have produced a significant work. It is wonderfully written and edited, and beautifully bound and produced. This tribute to Aron Nimzowitsch represents the spirit of traditional book publishing at its unqualified best.

My assessment of this product: Order Aron Nimzowitsch: On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 (Hardcover) by Per Skjoldager & Jrn Erik Nielsen

A PDF file of this week's review, along with all previous product reviews, is available in the ChessCafe.com Archives.

Comment on this week's review via our official Chess Blog!!

[ChessCafe Home Page] [ChessCafe Shop] [ChessCafe Blog] [Book Review] [Columnists] [Endgame Study] [The Skittles Room] [ChessCafe Links] [ChessCafe Archives] [About ChessCafe.com] [Contact ChessCafe.com] [Advertising] 2013 BrainGamz, Inc. All Rights Reserved. "ChessCafe.com" is a registered trademark of BrainGamz, Inc.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Exploits and Triumphs, in Europe, of Paul Morphy, the Chess ChampionОт EverandThe Exploits and Triumphs, in Europe, of Paul Morphy, the Chess ChampionОценок пока нет

- (Chess Ebook) - Master Class - Typical Mistakes - Neil McDonaldДокумент17 страниц(Chess Ebook) - Master Class - Typical Mistakes - Neil McDonaldjohnnythebiggestОценок пока нет

- Hansen 41Документ18 страницHansen 41fdmbzfОценок пока нет

- Alekhine On CarlsbadДокумент17 страницAlekhine On CarlsbadToshiba Satellite100% (1)

- Hansen 34Документ20 страницHansen 34fdmbzf100% (1)

- The Sicilian Najdorf 6 Bg5: Kevin Goh Wei MingДокумент21 страницаThe Sicilian Najdorf 6 Bg5: Kevin Goh Wei MingCaralde AceОценок пока нет

- Chess Lessons: Quality Chess WWW - Qualitychess.co - UkДокумент17 страницChess Lessons: Quality Chess WWW - Qualitychess.co - UkUjaan Bhattacharya100% (1)

- Evans Gambit PDFДокумент2 страницыEvans Gambit PDFKaren0% (2)

- Best Chess Games: Bobby Fischer - Reuben FineДокумент2 страницыBest Chess Games: Bobby Fischer - Reuben FineCharles GalofreОценок пока нет

- The Czech Benoni EmmsДокумент6 страницThe Czech Benoni EmmsleomellaОценок пока нет

- Victor Bologan - The Psychology of The Decisive MistakeДокумент7 страницVictor Bologan - The Psychology of The Decisive MistakeRenukha PannalaОценок пока нет

- Test, Evaluate and Improve Your ChessДокумент12 страницTest, Evaluate and Improve Your ChessAnonymous kdqf49qbОценок пока нет

- Rizzitano, James - Play The Najdorf SicilianДокумент148 страницRizzitano, James - Play The Najdorf SicilianDino BesozziОценок пока нет

- How To Beat 1 d4Документ4 страницыHow To Beat 1 d4radovanbОценок пока нет

- Tennison GambitДокумент2 страницыTennison GambitKartik ShroffОценок пока нет

- Shereshevsky Mihail Slutsky LM Mastering The End Game Vol 2Документ250 страницShereshevsky Mihail Slutsky LM Mastering The End Game Vol 2Tickle AccountОценок пока нет

- Mihail MarinДокумент16 страницMihail MarinMáximo Moreyra Tinoco100% (1)

- Benoni: 3 E5 Czech Benoni 3 E6 Modern Benoni 3 b5 Volga / BENKO GambitДокумент6 страницBenoni: 3 E5 Czech Benoni 3 E6 Modern Benoni 3 b5 Volga / BENKO GambitsalihОценок пока нет

- Franklin K. Young - The Major Tactics of Chess (1919) PDFДокумент284 страницыFranklin K. Young - The Major Tactics of Chess (1919) PDFPetronio66100% (1)

- Blumenfeld GambitДокумент13 страницBlumenfeld GambitManuelGerardoMonasterioОценок пока нет

- Learn From: Kasparov's GarryДокумент54 страницыLearn From: Kasparov's Garrytalhahameed85Оценок пока нет

- Win With The Stonewall Dutch: Sverre Johnsen, Ivar Bern & Simen AgdesteinДокумент1 страницаWin With The Stonewall Dutch: Sverre Johnsen, Ivar Bern & Simen AgdesteinEuqah Fisuat Azrim0% (1)

- Improving Upon Kasparov-KramnikДокумент3 страницыImproving Upon Kasparov-KramnikjogonОценок пока нет

- Anand 1.e4 c5 Vol.12 - KhalifmanДокумент3 страницыAnand 1.e4 c5 Vol.12 - Khalifmanmuthum444993350% (1)

- Common Sense in Chess - Lasker PDFДокумент148 страницCommon Sense in Chess - Lasker PDFFabio MoscarielloОценок пока нет

- Attacking Chess KI, Vol 1 ExtractДокумент7 страницAttacking Chess KI, Vol 1 ExtractRenzo Marquez100% (1)

- MBM Sicilian Dragon ExtractДокумент15 страницMBM Sicilian Dragon ExtractEllisОценок пока нет

- Sistema Colle 2da ParteДокумент160 страницSistema Colle 2da ParteCristóbal González VásquezОценок пока нет

- Dutch DefenseДокумент3 страницыDutch DefenseNuwan RanaweeraОценок пока нет

- The Instructor: Training With GrandmastersДокумент13 страницThe Instructor: Training With GrandmastersFuad AkbarОценок пока нет

- Novice Nook: Tactical Sets and GoalsДокумент6 страницNovice Nook: Tactical Sets and GoalsPera PericОценок пока нет

- Dvoretsky (Trap 1) PDFДокумент10 страницDvoretsky (Trap 1) PDFJude-lo AranaydoОценок пока нет

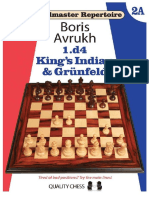

- PDF 1d4 Kingx27s Indian Amp Grunfeld 2a 2018 1 DDДокумент337 страницPDF 1d4 Kingx27s Indian Amp Grunfeld 2a 2018 1 DDGerSalas17Оценок пока нет

- Kramnik, Kasparov and ReshevskyДокумент6 страницKramnik, Kasparov and Reshevskyapi-3738456Оценок пока нет

- King's Indian DefenseДокумент11 страницKing's Indian DefenseAb AU100% (1)

- Sveshnikov Sicilian Defense CHessДокумент3 страницыSveshnikov Sicilian Defense CHessGerardoIbarra100% (2)

- Hacking Up The King - David Eggleston (Print Layout)Документ265 страницHacking Up The King - David Eggleston (Print Layout)Abhas BhattacharyaОценок пока нет

- King's Indian Defence - WikipediaДокумент51 страницаKing's Indian Defence - Wikipediaferdinando16Оценок пока нет

- Top 50 Chess Quotes of All TimeДокумент6 страницTop 50 Chess Quotes of All TimeHoracio MarmotoОценок пока нет

- Chebanenko Slav PDFДокумент4 страницыChebanenko Slav PDFSteve Ormerod100% (1)

- Pawn Power by Dunnington Angus.Документ109 страницPawn Power by Dunnington Angus.Manuel QuesadaОценок пока нет

- Chess Problems Made Easy - T.tavernerДокумент101 страницаChess Problems Made Easy - T.tavernerAid Farhan MaarofОценок пока нет

- The Modern Benoni & Castling Long PDFДокумент8 страницThe Modern Benoni & Castling Long PDFelenaОценок пока нет

- Fritz18 Manual-EngДокумент425 страницFritz18 Manual-EngQlibetОценок пока нет

- B33Документ6 страницB33lol364Оценок пока нет

- Keverel Chess CatalogueДокумент176 страницKeverel Chess CatalogueЮлия ПесинаОценок пока нет

- PDF 04Документ6 страницPDF 043187265100% (1)

- The GambitДокумент186 страницThe Gambitchess manОценок пока нет

- Beating The Hedgehog System: Using A Space Advantage in The Chess OpeningДокумент15 страницBeating The Hedgehog System: Using A Space Advantage in The Chess OpeningSteffany L WОценок пока нет

- Works of Damiano Ruy Lopez SalbioДокумент416 страницWorks of Damiano Ruy Lopez Salbiotudoranluciana1Оценок пока нет

- BeatingtheAnti Sicilians ExcerptДокумент15 страницBeatingtheAnti Sicilians ExcerptDaniel's Jack67% (3)

- 29) Build-up-Your-Chess-3-exceprt PDFДокумент16 страниц29) Build-up-Your-Chess-3-exceprt PDFhoni230% (1)

- Ccafe Spinrad 31 Colonel Moreau 1Документ6 страницCcafe Spinrad 31 Colonel Moreau 1Anonymous oSJiBvxtОценок пока нет

- Edward Winter - Kasparov's 'Child of Change'Документ7 страницEdward Winter - Kasparov's 'Child of Change'Jerry J MonacoОценок пока нет

- The Instructor 18 - Should He Have Sacrificed - DvoretskyДокумент9 страницThe Instructor 18 - Should He Have Sacrificed - DvoretskyDaniel López GonzálezОценок пока нет

- Advance Chess - Inferential View Analysis of the Double Set Game, (D.2.30) Robotic Intelligence Possibilities: The Double Set Game - Book 2 Vol. 2От EverandAdvance Chess - Inferential View Analysis of the Double Set Game, (D.2.30) Robotic Intelligence Possibilities: The Double Set Game - Book 2 Vol. 2Оценок пока нет

- 2016-08 DS Osa5548c SsuДокумент2 страницы2016-08 DS Osa5548c SsunguyenaituyenОценок пока нет

- CX-One: FA Integrated Tool PackageДокумент23 страницыCX-One: FA Integrated Tool Packageairderas192488100% (2)

- AR 114 2034 ROOFING FinalДокумент13 страницAR 114 2034 ROOFING FinalJohn Lloyd CabreraОценок пока нет

- By: Engr. Ronald John R. CajillaДокумент1 страницаBy: Engr. Ronald John R. CajillareynoldОценок пока нет

- Model GP Building EstimateДокумент153 страницыModel GP Building Estimatekalyan_kolaОценок пока нет

- Airlaser Ip1000 EnglischДокумент55 страницAirlaser Ip1000 EnglischdictvmОценок пока нет

- SG 246219Документ458 страницSG 246219api-3707774Оценок пока нет

- CHP 4 Reading Organizer - Student VersionДокумент6 страницCHP 4 Reading Organizer - Student VersionAntonio LópezОценок пока нет

- Northeast Regional Corrections Center (NERCC) Campus ImprovementsДокумент8 страницNortheast Regional Corrections Center (NERCC) Campus ImprovementsSenateDFLОценок пока нет

- Design of Concrete Structures 15edДокумент4 страницыDesign of Concrete Structures 15ederjuniorsanjipОценок пока нет

- A Study of Selection of Structural SystemДокумент9 страницA Study of Selection of Structural SystemEmal Khan HandОценок пока нет

- VMware L1 L2 L3 TasksДокумент4 страницыVMware L1 L2 L3 TasksPruthviraj Nayak50% (2)

- HILTI Firestop and Fire Protection SystemsДокумент9 страницHILTI Firestop and Fire Protection Systemsfrikkie@100% (1)

- GVG M2100Документ21 страницаGVG M2100hafizabadknightsОценок пока нет

- TR 196Документ131 страницаTR 196Yooseop KimОценок пока нет

- BCD EditДокумент22 страницыBCD EditpedrokaulsОценок пока нет

- Mould Hot Runner SystemsДокумент10 страницMould Hot Runner SystemsVimal AathithanОценок пока нет

- Epox Ep-9npa3 Sli Ep-9npa7 ManualДокумент84 страницыEpox Ep-9npa3 Sli Ep-9npa7 ManualGiovanni De SantisОценок пока нет

- SAP Analytics CloudДокумент17 страницSAP Analytics Cloudccreddy830% (1)

- Load Propelling Trolley Design ReportДокумент45 страницLoad Propelling Trolley Design Reporthafizheykal0% (1)

- Using C To Create Interrupt Driven Systems On Blackfin ProcessorsДокумент9 страницUsing C To Create Interrupt Driven Systems On Blackfin ProcessorsEmin KültürelОценок пока нет

- Design of Flat Slab Using Equivalent Frame MethodДокумент41 страницаDesign of Flat Slab Using Equivalent Frame Methodabadittadesse100% (2)

- Siemens PLM NX Mold Flow Analysis Solutions Fs Y7Документ5 страницSiemens PLM NX Mold Flow Analysis Solutions Fs Y7Nuno OrnelasОценок пока нет

- Ccure-9000-Security-Managmt-V1 92 Ds r10 LT enДокумент4 страницыCcure-9000-Security-Managmt-V1 92 Ds r10 LT enflaviodooОценок пока нет

- Tourist GuideДокумент116 страницTourist GuidejuliangalindoОценок пока нет

- Checklist For Waterproofing - TerraceДокумент1 страницаChecklist For Waterproofing - Terraceyash shahОценок пока нет

- Factors Influencing The Performance ofДокумент3 страницыFactors Influencing The Performance ofjoshua laraОценок пока нет

- Tempcon Sandwich Panel BrochureДокумент10 страницTempcon Sandwich Panel BrochureskmeshramОценок пока нет

- Spring Boot ReferenceДокумент385 страницSpring Boot ReferenceNilesh KutariyarОценок пока нет

- Floor Truss GuideДокумент4 страницыFloor Truss GuideSamia H. BhuiyanОценок пока нет