Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Development of Free Speech in Modern Britain

Загружено:

Hans GretelАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Development of Free Speech in Modern Britain

Загружено:

Hans GretelАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Development of Free Speech in Modern Britain

John Roberts is a Senior Lecturer in Sociology and Communications at Brunel University. He received a PhD at Cardiff University in 2000 for his thesis on the sociological history of free speech at Speakers Corner in Hyde Park. John has specialised in research and writing about how different social and political movements have sought to extend the right to free speech in Londons parks. His more theoretical work argues for an inclusive theory of free speech. More recently, John has written about how management and employees discuss and debate contemporary changes in how they work together. He is also about to embark on research which will look at whether new media has changed the way we debate social and political issues. Email: John.Roberts@brunel.ac.uk

In this essay John Roberts traces the origins of our commitment to free speech to the ancient Athenian conviction that its exercise is the defining characteristic of citizenship and a prerequisite for democratic governance. He goes on plot its development in this country from the Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest of the early thirteenth century. But while these famous settlements mark perhaps the first significant transfer of power from the monarch to a wider ruling group, it was not until the English civil war four hundred years later that the fight for free speech became part of the broader struggle for civil and political rights. Roberts cites the Levellers as one of the first committed groups of campaigners for freedom of expression but notes that their agenda was too progressive and too egalitarian even for Cromwells reforming Parliamentarians. He also illustrates how vigorously, particularly after the Restoration, the political establishment not only resisted the development of new rights but also framed the law, particularly on libel, to suppress freedom of expression both as a right in itself and as a vehicle for wider reform. He shows how the radical new thinking of the Enlightenment combined with the dramatic impact of the industrial revolution on the conditions of working people to generate new mass movements for reform which, while they met with determined and, as with the Peterloo Massacre of 1819, occasionally violent reaction from the governments of the day, eventually forced the concessions which from the mid 19th century onwards gradually established the rights British citizens enjoy today. But as Roberts observes, many of those rights, including freedom of speech, were only enshrined in British law as recently as 1998 when Parliament adopted the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms as part of the Human Rights Act. He points out too that even since that time, legislation - most notably the Terrorism Act of 2000 empowers the authorities to curtail a number of those civil liberties in the cause of national security. As Roberts concludes, free speech along with other democratic entitlements have been hard won in Britain as elsewhere: free speech, then, is not merely a gift bestowed on us by judges and government ministers. Free speech and what it means and entails depends on people coming together in order to test its limits. A healthy democracy demands this.

Introduction The Classical Inheritance

Free speech is recognised as a fundamental civil liberty for the maintenance of a healthy modern democracy but its roots go back far into history. In ancient Greece the term parrhesia was used to describe a practice which stipulated that a citizen should not only exercise free speech but should also speak the truth even at personal risk (see Foucault 2001) in the manner, for example, of Socrates who famously paid with his life for being outspoken. As Saxonhouse (2006: 24) observes, this view of free speech was related to a broader belief the ancient Greeks shared about democratic participation. For them, democracy meant self-rule where the separation between the state and civil society a key prerequisite of modern democracies didnt yet exist. In ancient Athens this meant that Greek citizens could play an active role in the largest policy-making arena known as the Assembly. And one key element of being actively involved in the Assembly was the right for every citizen to stand up and make a speech about a matter that concerned them. In such a large public space with hundreds listening, one was impelled to speak through courage, conviction and passion. That is to say, each person had to embody parrhesia. Of course, it is also true that Greek democracy was built on the sweat and labour of slaves who, like women, could observe but not practice free speech. Nonetheless, ancient Greek ideas about free speech have proved highly influential for modern democratic movements. For example, the belief that free speech is a key feature of a broader democratic principle of popular sovereignty and self-government has been embraced in different ways by a wide variety of political leaders and social activists from the fifteenth century onwards. Some radical political and social movements have seen free speech as one of a range of interrelated political and economic rights all of which are necessary prerequisites for a genuinely democratic society. Others have suggested that a discrete right to free expression should merely enable individuals and not always all individuals to enhance their personal autonomy and self-cultivation through the power of reason and deliberation (Saxonhouse 2006: 26-7). This short essay will explore how modern British history has been informed by both viewpoints. On the one hand free speech has been promoted and defended as one means amongst others to extend and deepen democratic self-government while on the other it has been advanced as a means for individuals to enhance their autonomy in democratic deliberation with others. In many respects both viewpoints have proved to be a blessing and a curse. They have opened up gaps in the legal framework for ordinary people to campaign for greater protection and for the legal ratification of free speech and, critically, the rights of association and assembly along with other democratic rights. But they have also allowed governments to argue that some people invariably those in power should have greater rights than others to free speech. By exploring a number of examples from modern British history we will see that far from being granted free speech by benevolent governments, British people have had to fight long hard battles against them to win this very special right.

Magna Carta and Early Rights

Without doubt, Britain has been seen by other nations as a standard-bearer for the guarantee and promotion of modern rights. And there is good reason why this image has prevailed. In 1215, for example, King John agreed to a new set of rights for the English population that became known as the Magna Carta. None of its sixty-three clauses made reference to the right to free expression but by curbing royal powers and strengthening individual protection, they sought in other ways to extend liberties to the freeman of England. Clause 37 ensured that a person could be arrested only through the law of the land. Clause 41 acknowledged the growing influence of a nascent bourgeois merchant class through its guarantee that traders would be allowed the freedom to travel across England. The rights of women to claim their inheritance after the death of their husband and not be forced into another marriage were also recognised. Critically, as Linebaugh (2008: 31-6) notes, the Magna Carta also contained clauses (47 and 48) which safeguarded common rights to forests and woodlands. At a time when the majority of ordinary people gained much of their subsistence from common pastures, these clauses conceded that their rights had to be protected. Two years later the Charter of the Forest was issued by King Henry III as a complementary set of rights to the Magna Carta. The Charter embedded and extended clauses 47 and 48 into seventeen new clauses so that, for instance, the abuse by some in power of unfairly taxing commoners use of the land was now outlawed. While most of the clauses in the Magna Carta were repealed by the nineteenth century, Linebaugh notes that the principles contained in it proved to be a rallying point in other countries. Notably, many of those who fought in the North American War of Independence five hundred years later were united in seeing the Magna Carta as a document which justified their resistance against the British (Linebaugh 2008: 171). But the Magna Cartas importance also lay in its recognition of the democratic and economic aspirations of new feudal elite interests and its recognition that commoners likewise should enjoy various rights. Symbolically therefore, the Magna Carta signified a growing tension in English society over which rights should be extended and protected: those of the elite or those of commoners. This tension soon asserted itself in medieval England, particularly in a new and emerging public sphere of communication. Marketplaces were used by the monarchy and nobility on an increasing scale in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries to issue public proclamations. Generally, the aim of such proclamations was to help form public opinion and emphasise the kings role as the guarantor of peace, security, and good government (Masschaele 2002: 392). Broadsides single sheets of information posted up by officials in public places were likewise becoming more common in the late fourteenth century and signalled an early type of print culture.

Another important transformation of the public sphere occurred in 1352 with the passing of the Statute of Treasons. One of the main aims of this legislation was to limit prosecutions of treason to those overt acts of planning the death of the king. As a result, dissident speech was now not in itself deemed to be an act of treason. Yet in practice the overt act condition was often simply ignored at trials. In fact, any speech could now be judged as dissident speech, particularly those considered hostile to the government on important political issues, and the person making the speech might still therefore be prosecuted (Mayton 1984: 99-100). However, rural literacy was also increasing during this period, helped in part by priests willing to teach some rural inhabitants basic reading and writing for a small cost (Justice 1994: 29-33). Literacy skills were strengthened by the growing number of peasants able to sign their name on charters and documents to acquire pastures from landlords. Along with being able to recognise only a handful of Latin words, signing ones name gave peasants a familiarity with a documentary culture. This was a powerful symbolic expression of ones freedom from being forced to work by a landlord and ones freedom to own land. Indeed, Justice (1994: 36-7) argues that knowledge of land charters and documents became embedded in popular rural ideas of free status employed in the Peasants Revolt of 1381. One command issued to King Richard II by peasant leaders stated that no one should be bound to serve another except voluntarily and by free consent (cited in Justice 1994: 37). Rebellious peasants also recognised the symbolic power of controlling public space in order to articulate their demands for greater land rights. In the town of St. Albans, for example, peasants gathered in the marketplace to hold a mass meeting and swear oaths of allegiance to one another. They then issued their own proclamations, one of which demanded that some nearby woods owned by a local lord should be confiscated and instead be held in common for all to enjoy (Masschaele 2002: 416). In medieval England, then, the basis was set for a new public sphere to develop in later years through new modes of communication in public spaces and through the use of documents, literacy, and a nascent print culture. In addition, prosecution for treasonable words was becoming more coherently defined in a legal sense. Successive generations of political and social activists would use this growing public sphere to construct a historical narrative to claim that documents like the Magna Carta had legally established something akin to an English constitution to safeguard the liberties of all. Therefore, if these liberties should come under attack from tyranny, whether Royal or Parliamentary, it was incumbent on ordinary people to restore them once again. One such group of activists were the Levellers.

Civil War Radicalism

Emerging with gusto during the Civil War (1642-51), the Levellers, who initially sided with Cromwell, campaigned for a number of what today we would regard as progressive left-wing beliefs. Some sought to ensure that all freeborn men enjoyed the right to vote, while others were concerned to establish a number of rights which could not be curtailed by Parliament. These included freedom of worship, freedom from conscription, indemnity from prosecution, equality before the law and a commitment that the content of the law itself must be fair (Vallance 2009: 165).

The Levellers were also skilled at making use of a budding print culture. Books, pamphlets, public notices, petitions, and newspapers grew in popularity, fuelled in part by dissenting voices thrown up by the Civil War. Certainly, influential political interests in Parliament exploited print for propaganda purposes, for example by sanctioning political leaks into the public domain to influence a particular debate (Peacey 2007: 96). But the Levellers used print media to turn the tables on their opponents propaganda. This helped to further their own agenda and enabled them to tap into an already established debate in England about the meaning of free speech itself. In early Stuart England some had argued for a pragmatic vision of free speech whereby one should speak out when necessary depending on the circumstances. If, for example, one perceived the actions of a neighbouring country to be a threat to England, it was a civic duty to state this opinion even if it offended the English monarchy and government (Colclough 2005: 5). These discussions gained momentum after Charles I was crowned in 1625. For instance, his various attempts to raise money, including the notorious Forced Loan of 1626-7 which compelled subjects to pay five subsidies to the Crown to finance a military campaign in Denmark (on which see Cust 1985), gave rise to populist oppositional voices which instead championed ancient liberties and common rights. Indeed, when the king attempted to restore the forest laws in 1634 for his own benefit, one member of an Essex grand jury overseeing this task asked to read a copy of King Johns charter to ascertain whether Charless actions held legal force (Underdown 1985: 125). In peoples memories the Magna Carta still therefore carried symbolic importance with regard to popular rights. One illustration of the Levellers contribution to these ongoing debates emerged in June 1647 when the Leveller agitator William Walwyn republished the fifth demand of thirteen set out in the Large Petition that called for the development of equal rights and which Parliament had rejected three months earlier. He wrote: That no man, for preaching or publishing his opinion in religion in a peaceable way, may be punished or persecuted as heretical by judges Importantly, during this period religious preaching had become a mechanism for dissenting voices to address large groups of ordinary people about the social and political ills of the day. Indeed, many preachers and agitators used the Gospels to suggest that God had created all people equal and therefore it was His desire that equality be practiced on earth and not just in heaven. Religion was thus an important device for those who wished to exercise free speech. This more materialist reading of religion relating the Scriptures to social questions like equality was bolstered in part by the effects of the Renaissance. Beliefs in the power of reason and empirical evidence to guide ones intellect had gained some ground amongst influential English writers. John Milton notably penned his Areopagitica in 1644 in which he criticised censorship of the press and advocated individual freedom.

Unsurprisingly therefore, the Large Petition also implored the authorities not to prosecute any person who criticised Parliament and instead pursue the virtues of true freedom for all. Other demands sought to embed this wide vision of free speech in a plea for a more equitable and just society: improving the lot of those at the bottom of the social scale so that they didnt have to beg to survive was one; others sought to give greater rights to prisoners and called for the withdrawal of sentences and fines imposed on commoners without due legal process. Critically, the Levellers and other radical movements had begun to link rights to material welfare to rights to free thought and expression. Indeed, Walwyn, like all Levellers, took it for granted that writing pamphlets which championed these causes was his natural right. As a result, the right for all to practise free speech along with a whole host of other rights like freedom of thought, religion, conscience, the press and assembly were regarded by the Levellers as prerequisites for a healthy democracy (see Wood and Wood 1997; Woodhouse 1986). By the time Walwyn republished the Large Petition he, like other Levellers, had become frustrated by Cromwells Parliament and the new vested interests residing therein. He believed it included malignants, and delinquentslawyers (some few excepted)monopolising merchants, the sons and servants of the Lords who had grouped together to vote against the presentation of the Large Petition to the Commons. Cromwells supporters had in turn grown tired of radicals like the Levellers. In 1649 one Cromwellian went as far as to write of their pamphlets that: among all the exorbitances of this last age, there is none that hath stained the glory of this nation more than the multitude of licentious and abusive pamphlets that continually fly abroad like atoms in the air, whereby the press is made a common strumpet to conceive and bring forth this froth of every idle and wanton fancy, or to vent the malice and venom of every discontented and debauched spirit (cited in Peacey 2007: 99). What Walwyn and the Levellers came to represent was an early modern popular movement in England to promote and extend the right of free speech. In this respect they occupy an important place in a British political tradition of campaigning for the right of ordinary people both to enjoy and to exercise their right to free speech in pursuit of other rights.

Free Speech and Equality Sedition and the Establishment

Of course, the history of such campaigns has not been an easy one. Innumerable obstacles have been placed in their way by the governments of the day. One such obstacle in early modern Britain was prosecution through libel and in particular of seditious libel, construed as an incitement to revolt or to encourage acts of violence against authority and employed as much to preserve the political status quo as protect the reputation of individuals.

In 1606 the common law judge Sir Edward Coke famously declared that any words thought by the courts to be insulting against private individuals or government officials could be punished as libel even if the words were found to be true (Kersch 2003: 48). The truth of a potentially seditious statement was decided solely by the judge while a jury would merely consider the facts of a case but make no judgement as to its seditious status. With a growing print culture some in authority therefore took the view that defamation through print (libel) as opposed to the spoken word (slander) was more damaging to a persons reputation precisely because it was more permanent and reached a wider audience (Rolph 2008: 52-3). Significantly, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the words seditious and libel were brought together by governments and judges to create an offence of seditious libel which was often arbitrarily used to prosecute political opponents and those thought to bring the monarchy or government into public disrepute through written or spoken words. Political opponents would therefore often be silenced and many were jailed for what were considered libels against authority. Walwyn for example noted in his 1647 tract that one member of the House of Commons had referred to the original Large Petition as a scandalous and seditious paper. Two years later he was imprisoned merely for being associated with Leveller pamphlets. While Charles I lost his head during the Civil War, the restoration of the monarchy in 1689 under King William III and Queen Mary II led to the Bill of Rights being passed in the same year. Ensuring the monarchy was restrained by handing over considerable decision-making powers to the government of the day, the Bill of Rights also guaranteed free speech for MPs in the confines of Parliament. But the right of free speech was a more complex issue for ordinary people. Again, the law on libel shows us why. Libel gained a more coherent legal definition in the eighteenth century. Between 1765 and 1769 Sir William Blackstone published his landmark common law texts and in volume four outlined a legal definition of freedom of the press. According to Blackstone, one should not expect absolute freedom to publish whatever one desired. On the contrary, he believed that the only freedom one should assume is that any book or pamphlet need not be subject to prior approval by a government before it was published. But if it contained improper, mischievous, or illegal words the author could, and should in Blackstones eyes, feel the full force of law. Certainly, what might constitute improper, mischievous, or illegal words might be open to question but significantly Blackstone stated that those words engaged in an immoral or illegal tendency and which brought about a breach of the peace could be treated as libel. As Curtis (2000: 45) notes, Blackstone was effectively suggesting that if it could be shown that what had been printed led to violent revenge, the author could be prosecuted whether or not what had been written contained an element of truth. Significantly, the maintenance of order took precedence over the expression of truth.

Perhaps its not so remarkable that Blackstone should have taken such a restrictive view of free speech and the press. In his own day platform politics witnessed what he might have regarded as a dangerous resurgence. For example, the radical MP John Wilkes first published the newspaper, the North Briton, in 1762. Coming from a rich merchant background, Wilkes tapped into growing discontent over increased bread prices, falling wages and unpredictable employment. The North Briton capitalised on this anger and in April 1763 published an attack on a speech by George III who had attracted critics for promoting his friend, the Earl of Bute, to the post of Prime Minister. Incensed by the article, the government decided to prosecute Wilkes for seditious libel. His status as an MP enabled him to be freed from jail on a writ of habeas corpus (unlawful detention) and in 1763 he fled to Paris on hearing he was to be arrested again for the same offence. When he returned five years later to win the Parliamentary seat of Middlesex the authorities arrested him and only released him two years later (see Jephson 1968, vol. 1: chapter 2). During the eighteenth century Britain also saw an increasing number of public spaces and popular reading materials being made available for ordinary people to become engaged in debate and discussion about the issues of the day. Needless to say, these spaces and reading materials differed depending on ones social background. In London for example members of the newly emerging middles classes would parade their social status in recently opened public parks while those in the lower orders met regularly at events like public executions where they would often riot in favour the condemned, believing it an injustice that people would be launched into eternity for minor crimes (Roberts 2004). Some even referred to eighteenth century platform politics as scaffold politics for this very reason. When placed in this wider context Blackstones judgements can be seen as a reaction to an already burgeoning popular form of free speech.

Radicalism and Mass Movements for Reform

In the final quarter of the nineteenth century there was an explosion of influential and powerful arguments for a new vision of democratic rights. Thomas Spence, an ultra-radical, wrote a pamphlet in 1775 championing the rights of man by economic and political means, particularly through public ownership of land. This pamphlet, along with others he wrote in successive years, were enough to get him jailed for High Treason. More notably, Thomas Paine published his Rights of Man in 1791 which became a bestseller but which also prompted the government to convict him in his absence (he had fled to Paris) for seditious libel. One year later Mary Wollstonecraft wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, her famous tract advocating equality between the sexes. Due in part to the growth of this public sphere the Libel Act of 1792 was passed which took the power away from judges to decide the legality of criminal libels. Juries now enjoyed this privilege. But social life more generally was experiencing profound changes. Enclosure of agricultural lands by rich farmers who parcelled off and privatised huge swathes of the countryside for their own profitable ventures pushed many independent farmers into wage labour. Other workers found themselves swept along by industrialisation which appeared in workplaces associated with textile, pottery and iron production, while skilled workers sought protection of their livelihoods in trade and friendly societies which came to form the basis for modern trade unions (Wright 1988: 33-7).

This heady mix of radical thinking both at home and abroad along with shifting work patterns led to a new upsurge in organised political activism. Most famously, the London Corresponding Society, established in 1792 and with a membership drawn from artisans and advocating mainly parliamentary reform, used open air mass meetings to campaign for an extension of the franchise. These social forces reached a peak in 1795 when during protests over food shortages and the war with France a stone was thrown at a coach carrying George III. The government decided to clamp down on political protest. On 18 December 1795 the Treasonable Practices and Seditious Meetings Acts became law. Amongst other things, the first Act extended the definition of treason to written or spoken words while the second Act prohibited the holding of meetings of more than fifty persons without the permission of local magistrates (Hone 1982: 11). But while both Acts curtailed free speech, agitators used inventive means to overcome them. One illustration came in the guise of ultra-radical clubs, a home for veterans of late eighteenth-century radicalism. Such activists managed to circumvent the repressive hand of the law by holding meetings in obscure alehouses and taverns or by acquiring dissenting ministers licences in order to hide under the rubric of religious dissent which was more readily tolerated than political protest. These debating clubs tended to eschew polite formal political debate in favour of plebeian rhetoric which would often deal with politics through bawdy humour and popular culture (McCalman 1987; 1993). Populist radical sentiments also found an outlet in early nineteenth century progressive newspapers such as The Black Dwarf (first published in 1817). Plebeian and radical in its outlook, The Black Dwarf made use of satire alongside serious political arguments, news, and poetry (Hendrix 1976). In addition, the well-known radical agitator William Cobbett claimed to have sold 44,000 copies of the first edition of his Political Register in 1816 while Henry Hetheringtons Poor Mans Guardian had an average circulation of 16,000 in 1833 (Cannon 1981: 110). Displays of plebeian spirits were in turn soon reproduced at platform meetings. A notable instance was a meeting at Spa Fields in Islington, London, in December 1816. Gripped by an air of inclusive, mocking and concise debate, the Spa Fields meeting was also suffused with imagery and iconography. Some in the crowd could be seen wearing the cap of liberty which, with its strong association with the French revolution, clearly signified a radical approach to the right of public assembly, freedom of expression and popular sovereignty (Epstein 1989). These developments came to a head on 9 August 1819 at St. Peters Fields in Manchester when 60,000 people gathered to hear the radical orator Henry Hunt. Describing the radical platform as the true heir to constitutional freedom and the rule of law, Hunt used mass meetings to accuse the government of betraying the constitution. For him the radical platform was an opportunity to chronicle a legal history of struggles in Britain against absolutism which he believed were enshrined in the Magna Carta, Habeas Corpus, Bill of Rights and the Act of Settlement (Belchem 1981).

The sight of such vast numbers at St Peters Fields, many of whom were engaged in quasimilitary drilling, convinced Manchester magistrates to send in the yeomanry almost immediately to arrest Hunt. But they panicked and indiscriminately lashed out with their sabres. Eleven people were killed and over 600 injured. The incident reverberated throughout British society and became known as the Peterloo Massacre. Hunt was arrested and spent the next two years in jail. When eventually freed he decided to leave the mass platform and instead court public opinion by less radical means as well as setting up various businesses. Other radicals initially hesitated in their response to the massacre and debated amongst themselves as to what actions to take. As this debate continued the Tory government asserted its authority. On 29 November the notorious Six Acts became law, constraining multiple forms of political free speech in one stroke: (1) An Act to prevent the training of persons to the use of arms, and to the practice of military evolutions and exercise; (2) An Act to authorise Justices of the Peace, in certain disturbed counties, to seize and detain arms collected or kept for purposes dangerous to the public peace; (3) An Act to prevent delay in the administration of justice in cases of misdemeanour; (4) An Act for the effective prevention of seditious meetings and assemblies; (5) An Act for the more effectual prevention and punishment of blasphemous and seditious libels; (6) An Act to subject certain publications to the duties and stamps upon newspapers, etc. (Jephson 1968, vol. 1: 503-504). Freedom of expression through print and freedom of assembly through mass meetings could now be declared illegal. For example, the sixth act allowed the government to extend the existing publication stamp duty of 4d, which had originally been introduced in 1815, to those publications that appeared at least once a month and charged less than 6d. Many working class publications which had been outside of the remit of the 1815 stamp duty now found they were legally obliged to pay the new tax, potentially putting the cost of the paper beyond the means of its readers. But the Acts failed to stop a new generation of political agitators from exercising what they believed to be their right of free speech. Many working class newspapers refused to pay the stamp duty and in 1836 the government reduced it to 1d for all newspapers. This did not appease radical publishers and many still rejected it. In London the Society for the Promotion of the Repeal of the Stamp Duties was formed and by June 1836 the Society had transformed itself into the London Working Mens Association (LWMA). In January 1837 the LWMA drafted an address to Parliament which was to become known as The Peoples Charter and which subsequently proved to be the impetus for the Chartist movement. Based around six points universal suffrage, no property qualifications, annual parliaments, equal representation, payment of MPs and vote by ballot the Charter launched the most influential politically organised socialist movement of its time.

10

One key outcome of the Charter was that it helped to establish new public spheres for free speech about the social and political issues of the day. For instance, by travelling around the country and speaking at local rallies, Chartist activists ensured that Chartism remained both a local and national political movement. It also heralded an increasing sophistication through which working-class political debate came to be circulated through newspapers. Important in this respect was the establishment of the Northern Star by the Chartist leader Feargus OConnor in 1837. Conveying a populist political rhetoric, the Star sought to bring the working-class together by educating its readers through skilled journalism which communicated the latest political issues into understandable prose. Working class clubs and reading rooms stocked copies and they were also available in radical coffee houses and Chartist taverns. Likewise, the Star circulated amongst friends and colleagues or would be read out loud at collective gatherings (see Epstein and Thompson 1982). By the early 1850s Chartism had started to decline as a political force, not least because it was running out of strategies to push forward its political programme while many members began to move into other campaign groups. Even so, Chartism left its mark on British political culture. It demonstrated for instance that ordinary working class people could organise themselves into a potent political and social force, especially in the realms of public debate and print media. Indeed, prominent political thinkers were prompted in part to rethink the ideals of free speech in order to provide a response to the inclusive type of public debate advocated by new movements like Chartism. The most outstanding of these thinkers was John Stuart Mill. In 1859 Mill published On Liberty which tried to widen the definition of the liberty of thought and discussion through four distinct grounds. First, if any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility. Secondly...since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied. Thirdly, even if the received opinion be not only true, but the whole truth; unless it is suffered to be, and actually is vigorously and earnestly contested, it will, by most of those who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice, with little compensation or feeling of its rational grounds. And not only this, but, fourthly, the meaning of the doctrine itself will be in danger of being lost or enfeebled, and deprived of its vital effect on the character and conduct. (Mill1989: 53-54) In warning of the sin of infallibility and advocating respect for diversity and in arguing against prejudice and dogma Mill sought persuasively to convince those in polite society that they should recognise the right of others to engage in public debate even if they disagreed with their opinions.

11

Hyde Park and the Power of Assembly

More practically, Chartism showed how later political movements might organise themselves. One case in point was the rise of the Reform League in 1865. Led by the barrister Edmond Beales and seeking to extend manhood suffrage, the Reform League recruited an estimated 65,000 members to over 600 local branches. Like Chartism, the League adopted the tactics of open air mass meetings and demonstrations to further its cause. But it was also substantially different to Chartism to the extent that it received financial contributions from progressive employers, liberal academics and other middle-class reformers. These contributions and affiliations added an air of respectability to the Leagues image, status and resources that was lacking for Chartism (see Belchem 1996). On 2 July 1866 the Reform League stepped up its campaign by calling for a meeting at Hyde Park. Approximately 50,000 attended to hear Beales give a public address. Another was called for on 23 July. The Chief Superintendent of the Metropolitan Police, Sir Robert Mayne, was resolute that the meeting should not take place. Notices were put up prohibiting it and nearly 1,700 police surrounded the Hyde Park that night. While Beales and his followers decided to retreat to Trafalgar Square, the majority of protestors stayed in the park, gaining entry by forcing down the railings. Speeches were made and politics discussed. By midnight the crowds dispersed but returned two nights in a row (Coleman 1997: 31-2). Through their actions Hyde Park was increasingly being seen as a public space in its own right for ordinary men and women to engage in debate and discussion. In April 1867 a Working Mens Rights Association marched into Hyde Park to protest against the park being closed to them, as they contended they had a perfect right to be there (Dreher 1993: 134). Then, on 6 May 1867, the Clerkenwell Branch of the Reform League appeared at Hyde Park carrying a red flag surmounted by the cap of liberty. Half an hour later there were between 100,000 and 150,000 people in the park. In many respects these activists were deliberately provoking the authorities. Spencer Walpole, the Home Secretary, had previously announced that if the Reform League entered Hyde Park for the purpose of preaching and discussing they would be committing an act of trespass and be arrested. However, with such large numbers of protestors the authorities soon realised the futility of trying to block their entrance. The leaders of the League entered to the sound of festive cheering and proceeded to address the crowd from no fewer than ten separate platforms (Harrison 1965: 94). Popular broadsides written by protestors appeared in the streets celebrating the success of the demonstration. One stated: In Hyde Park, on the 6th, it was right against might, With Beales our leader, we beat them that night... Our rights! it is all that we ask, To meet with each other when labour is done, And speak out our minds in the Park. (cited in Dreher 1993: 134-135). The right to meet in Hyde Park and the question of the franchise had by now been translated into one and the same issue. Yet, once the Reform Act 1867 had given the vote to some sections of working class males the Reform League lost its momentum and was finally dissolved in 1869.

12

Campaigns to establish the right to free speech in public spaces, however, survived the Leagues demise. In March 1872 a report from the Metropolitan Police to the Home Office noted that meetings, some with crowds of 2,000, others with 200-300, were regularly occurring at Hyde Park on the issue of the right to free speech in public parks. In one meeting the speaker burnt an order prohibiting public assemblies in Hyde Park to loud cheers from the crowd. In another, a speaker called on the assembly to kick the government out of the country. In yet another, a white flag could be seen on which was stated that freedom of speech was the bulwark of liberty (Public Records Office [PRO]: HO 45/9490/3239). Such was the scale of these campaigns and meetings that later in 1872 the government introduced The Parks Regulation Act that gave people the legal right of public address at Hyde Park. In effect, the act formally recognised what became known as Speakers Corner. In the final years of the nineteenth century a whole array of social movements came to campaign for free speech. Political activism of women, for example, proved integral to the extension and guarantee of free speech in Britain. As Rowbotham (2011) observes, between the 1880s and 1920s British feminists were using pamphlets, books and public meetings to speak freely about a whole range of issues affecting women such as sex, birth control, housework, education, and the workplace (see also Dicenzo et al. 2011). Suffragette activists also ventured into other notable prominent public spaces to speak about the rights of women. Hyde Park once again provided an important platform for this political programme. In July 1926, for instance, a number of prominent Suffragettes met in Hyde Park as part pf their campaign for universal suffrage (see Vallance 2009: 529). Within this renewed political context it is perhaps not surprising to discover that while the government had granted the right of people to give a public address at Hyde Park, speakers who exercised this right constantly tested its free speech potential. In particular the authorities were concerned to prescribe what they believed to be proper topics of discussion. On 30 August 1908 a speaker called Herbert Blyth stood on a socialist platform at Hyde Park to inform the gathered crowd that he considered it a grave injustice that Oscar Wilde had been sent to prison for his sexuality. Indeed, Blyth spoke at length about different aspects of sexual behaviour. After a while, however, two plain clothed police officers stepped in and arrested him for using indecent and obscene language (PRO: MEPO 2/1211). Importantly, examples such as these illustrated that there was an ongoing challenge about what exactly constituted free speech at Hyde Park after 1872. For individual speakers like Blyth, it was an expressive and populist way to talk about a variety of social issues that remained relatively absent from mainstream public debate, while for the government public address was legitimate if it was situated within the bounds of what was thought of as public decency.

13

What the government meant by public decency can be gauged by one further illustration. In August 1925 an anarcho-communist called Guy Aldred was arrested at Hyde Park for using insulting words during his speech. Aldred told those listening that the Union Jack was both rotten and designed to keep people poor and ignorant and that the British national anthem was rubbish (Roberts 2008: 115-6). At his trial the magistrate found Aldred guilty of trying to precipitate a breach of the peace by insulting the Union Jack. This example indicates that the authorities held a very flexible notion of public decency. In the case of Aldred, it was related to symbolic markers of British imperial greatness; after all, Britain was still an imperialist nation in 1925 and the Union Jack was an emotional representation of the crown and military strength (Hobsbawn 1987: 105). Insulting the Union Jack was therefore perceived as an insult to the imperialist state and such indecent behaviour, so the authorities believed, had to be constrained and regulated. Yet such regulation was an acknowledgement that even though ordinary people could legally speak to the public at Hyde Park there was still ambiguity about their right to do so. But there was a change afoot more generally as regards platform politics in Britain. Public meetings were becoming less rowdy affairs. One reason for this, according Lawrence (2009: 128), was that after 1918 more people, including women, gained the right to vote. Therefore, those who once might have disrupted public meetings in order to voice their discontent at their exclusion from the franchise could now legitimately make their protests felt in the polling booth. In fact, such was the decline in energetic and lively displays of discussion at public gatherings and meetings during elections that by the 1950s major political figures like Tony Benn began to mourn the old days of petitions, indoor meetings, 100 per cent canvasses and the rest (Lawrence 2009: 155). Nonetheless, by the 1960s, at a time when the laws on censorship were being tested and reformed in celebrated legal cases such as the Lady Chatterly and Oz obscenity trials, a new generation of activists based around a politics such as feminism, sexuality, environmentalism, antiwar and disarmament, racial equality and so on, came together with more traditional political bodies like trade unions to embark on a new wave of protest politics and a platform politics of sorts. During the 1960s and 1970s the feminist movement, for example, became particularly adept at exploiting mass media for a new form of protest and self expression characterised by the disruption by activists of the 1970 Miss World contest in Londons Albert Hall. Interestingly, the debate about freedom of expression was then focused from the left as well as the right as much on what should be unacceptable for example, images perceived as degrading to women as what should be allowed. As history has shown, the limits of free expression can never be comprehensively defined but are constantly being tested and redetermined under pressure from one side of the line or the other.

14

Conclusion A Work in Progress

What constitutes free speech will always to some degree be a subject of controversy and speculation (for interesting perspectives see Alexander 2005; Fish 1994). These days, however, we regularly hear about how media outlets and the excessive spin used by politicians and their PR gurus have contributed to the dumbing down of political discourse. To what extent this does in fact represent a decline in public debate and free speech is subject to debate itself. But what cannot be denied is that the actions of ordinary people in early modern British history to gain and extend free speech set important precedents for successive generations of social and political campaigners throughout the twentieth century and they have left an inspiring and proud legacy for us living in the twenty-first century. Yet while British citizens have indeed enjoyed various rights enshrined in law, the UK is also unusual amongst many democratic countries. In 1948 the United Nations published the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 18 of which states that everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, while Article 19 asserts that everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression. But while many modern constitutions predate or reflect those principles, freedom of expression was only given legal guarantee by the British government in 1998 through the Human Rights Acts (HRA) which codified provisions of the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms into British law. Of particular relevance is Article 10 of the Convention, which states: Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. The fact that Britain only codified freedom of expression in 1998 demonstrates that, in one important respect at least, British domestic law prior to the HRA substantially restricted the ability of the British judiciary to consider free speech on the merits. In the vast majority of cases arising before the HRA, any claim that an act of Parliament unduly infringed legitimate speech rights was heard (if at all) by the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France (Krotoszynski 2006: 192). In effect, many UK courts in the 1980s and early 1990s were already applying a free speech principle in some common law cases such as those of libel. They saw it as their duty where possible to maintain free speech beyond the special interests of individuals, groups or organisations. Even before HRA, judges were therefore willing to provide legal protection for what they saw as foundational tenets of free speech (Barendt 2005: 40-1). However, despite the incorporation of the Convention, British judges are not empowered to enact a judicial review of existing British legislation should any element of domestic law be found to be incompatible with the HRA. They can instead seek to interpret the specific incompatibility through existing rules and statutes and in the process attempt to identify a resolution. If none can be found, a reviewing court can inform Parliament that an incompatibility exists between elements of domestic law and the European Convention (see Krotoszynski 2006: 183-4) but that is all they can do.

15

Krotoszynski goes on to observe that Parliament could repeal at any point statutes relating to freedom of expression in the HRA if it so wished. In fact, previous governments have introduced domestic laws which some have argued do indeed infringe civil liberties. The Terrorism Act of 2000 for instance grants police the power under s45 to zone areas of public space in order to carry out s44, namely the stop and search policy. As Moran (2005) notes: From 2001-2003 there was no part of London which had not been zoned for s44/45 searches (Moran 2005: 343). The Act also allows the police to restrain more conventional protests. Such legislation has moved the legal scholar K.D. Ewing to observe recently that it seems to be the case that free speech in Britain is being increasingly subordinated to the interests of national security (Ewing 2010: 176). But as we have also already noted the legal right to free speech and its associated civil liberties such as freedom of thought, conscience and religion and freedom of assembly and association have in many cases been extended and granted by successive governments under pressure from popular campaigns by ordinary and remarkable citizens prepared to struggle for these rights. Free speech, then, is not merely a gift bestowed on us by judges and government ministers. Free speech and what it means and entails depends on people coming together in order to test its limits. A healthy democracy demands this.

16

Bibliography and Further Reading

Alexander, L. (2005) Is There a Right of Freedom of Expression? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Barendt, E. (2005) Freedom of Speech, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Belchem, J. (1981) Republicanism, Popular Constitutionalism and the Radical Platform in Early Nineteenth-Century England, Social History 6: 1-32. Belchem, J. (1996) Popular Radicalism in Nineteenth-Century Britain, London: Macmillan. Cannon, J. (1981) New Lamps for Old: The End of Hanoverian England in J. Cannon (ed.), The Whig Ascendancy: Colloquies on Hanoverian England, London: Edward Arnold. Colclough, D. (2005) Freedom of Speech in Early Stuart England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Coleman, S. (1997) Stilled Tongues: From Soapbox to Soundbite, London: Porcupine Press. Curtis, M.K. (2000) Free Speech, the Peoples Darling Privilege: Struggles for Freedom of Expression in American History, Durham: Duke University Press. Cust, R. (1985) Charles I, the Privy Council, and the Forced Loan, The Journal of British Studies 24(2): 208-235. Dicenzo, M., Delap, L., and Ryan, L. (2011) Feminist Media History, London: Palgrave. Dreher, N.H. (1993) Public Parks in Urban Britain, 1870-1920: Creating a New Public Culture, PhD thesis, University of Pennsylvania. Epstein, J. and Thompson, D. (eds.) The Chartist Experience: Studies in Working-Class Radicalism and Culture, 1830-60, London: Macmillan. Epstein, J.A. (1989) Understanding the Cap of Liberty: Symbolic Practice and Social Conflict in Early Nineteenth-Century England, Past and Present, no. 122 (February): 75-118. Ewing, K.D. (2010) Bonfire of the Liberties: New Labour, Human Rights and the Rule of Law, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Fish, S. (1994) Theres No Such Thing as Free Speech: And its a Good Thing Too, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Foucault, M. (2001) Fearless Speech, Los Angeles: Semiotext(e). Harrison, R. (1965) Before the Socialists: Studies in Labour and Politics, 1861-1881, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Hendrix, R. (1976) Popular Humor and The Black Dwarf, Journal of British Studies, 16(1): 108-128. Hobsbawn, E. (1987) The Age of Empire 1875-1914, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. Hone, J.A. (1982) For the Cause of Truth: Radicalism in London, 1796-1821, Oxford: Claredon Press. Jephson, H. (1968) The Platform: Its Rise and Progress, vols. 1 and 2, London: Frank Cass and Co. Ltd. Justice, S. (1994) Writing and Rebellion: England in 1381, Berkeley and California: University of California Press. Kersch, K. (2003) Freedom of Speech: Rights and Liberties under the Law, ABC-Clio Inc. Krotoszynski, Jr., R. (2006) The First Amendment in Cross-cultural Perspective, New York: New York University Press:

17

Lawrence, J. (2009) Electing Our Masters: The Hustings in British Politics from Hogarth to Blair, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Linebaugh, P. (2008) The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All, Berkeley: University of California Press. McCalman, I. (1987) Ultra-Radicalism and Convivial Debating-Clubs in London, 17951838, English Historical Review, 102: 309-333. McCalman, I. (1993) Radical Underworld: Prophets, Revolutionaries and Pornographers in London, 1795-1840, Oxford: Clarendon Press Mayton, W.T. (1984) Seditious Libel and the Lost Guarantee of a Freedom of Expression, Columbia Law Review 84(91): 91-142. Masschaele, J. (2002) The Public Space of the Marketplace in Medieval England, Speculum 77(2): 383-421. Mill, J.S. (1989) On Liberty and Other Writings, edited by S. Collini, Cambridge University Press Milton, J. (1999) Areopagitica and Other Political Writings of John Milton, Liberty Fund Inc. Moran, J. (2005) State Power in the War on Terror: A Comparative Analysis of the UK and USA, Crime, Law and Social Change 44(4): 335-359. Paine, T. (2008) Rights of Man, Common Sense and Other Political Writings, ed. M. Philip, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Peacey, J. (2007) Print and Public Politics in Seventeenth-Century England, History Compass 5(1): 85-111. Public Records Office (PRO): MEPO 2/1211. PRO: HO 45/9490/3239 Roberts, J.M. (2004) From Populist to Political Dialogue in the Public Sphere, Cultural Studies 18(6): 882-908. Roberts, J.M. (2008) Expressive Free Speech, the State and the Public Sphere, Social Movement Studies 7(2): 294-313. Rolph, D. (2008) Reputation, Celebrity and Defamation Law, Aldershot, Hants: Ashgate. Rowbotham, S. (2011) Dreamers of a New Day: Women Who Invented the 20th Century, London: Verso. Saxonhouse, A.W. (2006) Free Speech and Democracy in Ancient Athens, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Underdown, D. (1985) Revel, Riot and Rebellion: Popular Politics and Culture in England 1603-1660, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Vallance, E. (2009) A Radical History of Britain, London: Abacus. Walwyn, W. (1647) Gold Tried in Fire, or the Burnt Petitions Revived, at http://www.constitution.org/lev/eng_lev_06.htm (accessed 01/12/11). Warburton, N. (2009) Free Speech: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Wollstonecraft, M. (2004) A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, London: Penguin. Wood, E.M. and Wood, N. (1997) A Trumpet of Sedition: Political Theory and the Rise of Capitalism 1509-1688, London: Pluto Press. Woodhouse, A.S.P. (ed.) (1986) Puritanism and Liberty: Being the Army Debates 1647-9, third edition, London: Dent. Wright, D.G. (1988) Popular Radicalism: The Working-Class Experience 1780-1880, London: Longman.

18

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- FBI - Report Cthulhu - CultДокумент33 страницыFBI - Report Cthulhu - CultDennis Deangelo100% (3)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Aleph BetДокумент16 страницAleph BetStephen MurtaughОценок пока нет

- David Beth - Aleister Crowley and The Dawn of AiwassДокумент11 страницDavid Beth - Aleister Crowley and The Dawn of AiwassCrabStar100% (5)

- Private Military CompaniesДокумент23 страницыPrivate Military CompaniesAaron BundaОценок пока нет

- Esoterism and The Left Hand PathДокумент3 страницыEsoterism and The Left Hand PathHans GretelОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- David Altman - Direct Democracy in Comparative Perspective. Origins, Performance, and Reform-Cambridge University Press (2019) PDFДокумент271 страницаDavid Altman - Direct Democracy in Comparative Perspective. Origins, Performance, and Reform-Cambridge University Press (2019) PDFfelixjacomeОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Due Diligence ChecklistДокумент4 страницыDue Diligence ChecklistHans Gretel100% (1)

- ContractДокумент2 страницыContractRaffe Di Maio100% (1)

- Modin, Yuri - My 5 Cambridge Friends Burgess, Maclean, Philby, Blunt, and Cairncross by Their KGB ControllerДокумент298 страницModin, Yuri - My 5 Cambridge Friends Burgess, Maclean, Philby, Blunt, and Cairncross by Their KGB Controlleryasacan8782100% (3)

- (BARTELSON) A Genealogy of SovereigntyДокумент330 страниц(BARTELSON) A Genealogy of SovereigntyTarsis DaylanОценок пока нет

- Don Webb The Seven Faces of DarknessДокумент57 страницDon Webb The Seven Faces of DarknessHans Gretel100% (2)

- Flowers Stephen Red RunaДокумент53 страницыFlowers Stephen Red RunaJoCxxxygenОценок пока нет

- Councilwoman Gym Renaissance AnalysisДокумент6 страницCouncilwoman Gym Renaissance AnalysisIan GaviganОценок пока нет

- Thomas Taylor - The Mystical Hymns of OrpheusДокумент264 страницыThomas Taylor - The Mystical Hymns of OrpheusSakisОценок пока нет

- Henry Dunant 2016 ProsecutionДокумент36 страницHenry Dunant 2016 Prosecutionkarti_am100% (13)

- Cultural Backlash Theory Power Point NorrisДокумент43 страницыCultural Backlash Theory Power Point NorrisJosé R.67% (3)

- A Thelemic PrimerДокумент12 страницA Thelemic PrimerMurilo Spricigo GeremiasОценок пока нет

- Article On Joseph RoyeppenДокумент4 страницыArticle On Joseph RoyeppenEnuga S. ReddyОценок пока нет

- Mg350 All PagesДокумент24 страницыMg350 All PagessyedsrahmanОценок пока нет

- Zuckerberg Petition Signers and Comments As of 1.11.17Документ121 страницаZuckerberg Petition Signers and Comments As of 1.11.17Leonie HaimsonОценок пока нет

- Property Syllabus With Case AssignmentsДокумент5 страницProperty Syllabus With Case AssignmentsJued CisnerosОценок пока нет

- Sayyid Saeed Akhtar Rizvi - ImamatДокумент69 страницSayyid Saeed Akhtar Rizvi - Imamatapi-3820665Оценок пока нет

- Keith Motors Site 1975Документ1 страницаKeith Motors Site 1975droshkyОценок пока нет

- Chapter #31: American Life in The "Roaring Twenties" - Big Picture ThemesДокумент17 страницChapter #31: American Life in The "Roaring Twenties" - Big Picture Themesapi-236323575Оценок пока нет

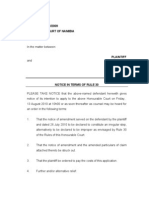

- 21 EXAMPLE NOTICE in Terms of Rule 30cДокумент3 страницы21 EXAMPLE NOTICE in Terms of Rule 30cAndré Le RouxОценок пока нет

- Seamus HeaneyДокумент17 страницSeamus Heaneyapi-3709748100% (4)

- Northern SamarДокумент2 страницыNorthern SamarSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Indian Foreign Policy - Objectives, Principles & DeterminantДокумент20 страницIndian Foreign Policy - Objectives, Principles & DeterminantSanskriti BhardwajОценок пока нет

- Nycaasc 2012 ProgramДокумент17 страницNycaasc 2012 ProgramSusan LiОценок пока нет

- United States v. Charleston County SC, 4th Cir. (2004)Документ18 страницUnited States v. Charleston County SC, 4th Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- AL Brothers Prakashan: 1. The Rise of Nationalism in EuropeДокумент13 страницAL Brothers Prakashan: 1. The Rise of Nationalism in EuropeVino AldrinОценок пока нет

- Violence in War and PeaceДокумент5 страницViolence in War and PeaceÁngela Botero CabralОценок пока нет

- Principles of Management: Managing in The Global ArenaДокумент16 страницPrinciples of Management: Managing in The Global ArenaKumar SunnyОценок пока нет

- Barrage PresentationДокумент10 страницBarrage Presentationpinky100% (1)

- Civil Liberties: Liberty of Abode and TravelДокумент14 страницCivil Liberties: Liberty of Abode and TravelJuris MendozaОценок пока нет

- Cast Certfct FormatДокумент1 страницаCast Certfct FormatNikhil IndurkarОценок пока нет

- Page 1 of 10: Learning CentreДокумент1 страницаPage 1 of 10: Learning Centreanurag mauryaОценок пока нет

- Bodenhausen & Peery (2009) - Social Categorization and StereotypeingДокумент22 страницыBodenhausen & Peery (2009) - Social Categorization and StereotypeingartaudbasilioОценок пока нет

- Legacies of Indian PoliticsДокумент20 страницLegacies of Indian Politicsyashasvi mujaldeОценок пока нет