Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Georgiev, G. 2001

Загружено:

vivhansonИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Georgiev, G. 2001

Загружено:

vivhansonАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Benefits of Commodity Investment

Georgi Georgiev

Ph.D. Candidate, University of Massachusetts

CISDM

CISDM Working Paper

March, 2001

Please Address Correspondence to:

Thomas Schneeweis

CISDM/School of Management

University of Massachusetts

Amherst, Massachusetts 01003

Phone: (413) - 545-5641

Fax: (413) - 545-3858

Email: Schneeweis@som.umass.edu

Benefits of Commodity Investment

Abstract

Direct commodity investment has historically been a minor part of investors asset allocation. In

recent years, however, investible commodity indices and commodity-linked assets have increased the

number of available commodity-based products. In this study, the various theoretical arguments for

the relative risk and return advantages of direct commodity investment are reviewed and then these

theoretical foundations are tested with the Goldman Sachs Commodity Indices. Investment in the

GSCI is shown to result in significant diversification benefits. These benefits are traced to the unique

exposure of commodity investment to macroeconomic variables, as well as the potential to capture a

positive roll return. This research places the use of commodity-linked or investible commodity

indices as a central part of the investors asset allocation decision.

1

Benefits of Commodity Investment

I. Introduction

Direct commodity investments have historically been a minor part of investors asset allocation

decision. In contrast, indirect investment (e.g., equity or debt ownership of firms specializing in

direct commodity market production) was the principal means of obtaining claims on commodity

investment. In recent years, however, investible commodity indices and commodity-linked assets

have increased the number of available direct commodity-based investment products. In addition,

there is increasing evidence that indirect commodity investment, through debt and equity instruments

in commodity-linked firms, does not provide direct exposure to commodity price changes

[Schneeweis et al., 1997b]. However, there is little information on the expected as well as the actual

risk and return performance of a wide variety of investible commodity indices or commodity linked

product) that have been marketed. The purpose of this study is, first, to detail the various theoretical

arguments for the relative risk and return advantages for real commodity investment and, second, to

test if currently available investible commodity forms such as the Goldman Sachs Commodity

Indices offer means to obtain the prescribed theoretical risk and return processes embedded in

commodity investment.

In the following section, the basis for and the structure of alternative indirect (e.g., stock funds)

as well as direct passive and active option- and futures-based investible commodity products are

reviewed. The expected return and risk structure for the GSCI indices (direct long-only futures-

based investible commodity indices) are analyzed as part of a fully diversified portfolio (stocks,

bonds, hedge funds, and real estate). Results (section III) indicate that the GSCI indices have sources

of risk and return (e.g. roll return, real options) that are distinct from traditional assets such as stocks

and bonds as well as managed futures or hedge fund benchmark indices and offer investors an

important area of diversification [Schneeweis et al., 1997a]. Conclusions and suggestions for future

studies will be discussed in Section IV.

II. Commodity Investment in Asset Management

The increased use of commodity trading vehicles in investment management has led

practitioners to create investible commodity indices and products that offer unique performance

opportunities for investors in physical commodities. As is true for stock and bond performance as

well as investment in managed futures and hedge fund products, commodity-based products have a

variety of uses. They are a source of information on cash commodity and futures commodity market

trends, are used as performance benchmarks for evaluation of commodity trading advisors, and

provide a historical track record useful in developing asset allocation strategies. However, the

investor benefits of commodity or commodity-based products lie primarily in their ability to offer

risk and return trade-offs that cannot be easily replicated through other investment alternatives.

Previous research [Schneeweis et al., 1997b] indicates that direct stock and bond investment offers

little evidence of providing returns consistent with direct commodity investment. To the degree that

firms hedge a major portion of the commodity risk [Chung, 2000], even commodity-based firms may

not be exposed to the risk of commodity price movement. Thus for investors, direct commodity

2

investment may be the principal means by which one can obtain exposure to commodity price

movements.

Academic research has examined the economic determinant of returns to commodity

investment. For example, Fama and French [1988] and Schneeweis, Spurgin, and Georgiev [2000]

identified a strong business cycle component in the variation of spot and futures prices of industrial

metals. Fama and French [1987, 1988] perform tests of the theory of storage and present empirical

evidence that in periods of increasing volatility and risk, convenience yields increase for a wide

variety of metals prices (e.g., aluminum, copper, nickel and lead). The theory of storage [Kaldor,

1939, Working, 1948, 1949, and Telser, 1958] splits the difference between the futures price and the

spot price into the forgone interest from purchasing and storing the commodity, storage costs and the

convenience yield on the inventory. Convenience yield reflects an embedded consumption timing

option in holding a storable commodity. Further, the theory predicts an inverse relationship between

the level of inventories and convenience yield at low inventory levels convenience yields are high

and vice versa. A related implication is that the term structure of forward price volatility generally

declines with time to expiration of the futures contract the so-called Samuelson [1965] effect.

This is caused by the expectation that, while at shorter horizons mismatched supply and demand

forces for the underlying commodity increase the volatility of cash prices, these forces will fall into

equilibrium at longer horizons.

Litzenberger and Rabinowitz [1995] observe that oil futures prices are often below spot prices,

that is futures markets are backwardated. Strong backwardation occurs when futures prices are below

current spot prices. In weak backwardation, discounted futures prices are below spot prices. Strong

backwardation is inconsistent with Hotelling's [1939] theory under certainty that the net price of an

exhaustible resource rises over time at the rate of interest. Litzenberger and Rabinowitz explain the

phenomenon with the existence of real options under uncertainty. They show that production

occurs only if discounted futures are below spot prices and strong backwardation emerges if the

riskiness of future prices is sufficiently high. Their empirical analysis presents evidence that U.S. oil

production is inversely related and backwardation is directly related to implied volatility. Related

option-based theories of backwardation and empirical tests can be found in the work of Milonas and

Tsomadakis [1997] and Routledge, Seppi, and Spatt [2000]. A major consequence of a declining term

structure of forward prices for investment in commodity futures is the opportunity to capture a

positive roll return as investment in expiring contracts is moved to cheaper new outstanding

contracts.

The question of whether commodities represent a separate asset class has been extensively

debated in both the academic and practitioner literature [Huberman, 1995, Strongin and Petsch, 1995,

Greer, 1994, Froot, 1996, Schneeweis et al., 1997a]. For many investors, the question no longer is

whether commodity investment is an asset class, but whether this asset class is appropriate for a

given investor, and if so what is the best approach to implementing the investment.

The diversification benefits of commodities have been studied in Ankrim and Hensel [1993],

Anson [1998], Becker and Finnerty [2000], and Schneeweis and Spurgin [1997b], among others. For

instance, Becker and Finnerty find that the inclusion of portfolios of long commodity futures

contracts (CRB and GSCI) improves the risk and return performance of stock and bond portfolios for

the period of 1970 through 1990. They observe that the improvement is more pronounced for the

1970s the 1980s due to the high inflation of the 1970s with commodities acting as an inflation hedge.

Futures prices were also found to have little value in predicting inflation.

Schneeweis and Spurgin [1997b] examine the correlations of oil-based futures contracts with

energy-related and non-energy related stock, bond, real estate and commodity markets, and CPI. Their

results confirm that, except in periods of extreme energy price movement, many traditional forms of

3

indirect energy investment such as natural resource mutual funds or energy-based common stocks are

not correlated with energy price movements. This is as expected. Given the risk management and firm

diversification abilities of most corporate firms, unless a the price change in the underlying commodity

is structural and long lasting, short term changes in commodity prices may have little impact on a firm's

equity performance. They also show that in addition to energy-based passive long-only commodity

indices offering returns not available in traditional equity investments, active long/short energy traders

offer returns (positive returns in markets with declining energy prices) not available in long-only

commodity indices or traditional commodity based equity investments.

Research on the LMEX [Scneeweis and Spurgin, 2000, Schneeweis, Spurgin, and Georgiev, 2000]

and precious metals reflects both the benefits of commodity indices as an alternative means to capture

commodity return not found through direct investing in the underlying production firm as well as

possible existence of roll return and the benefits of active trading in metals.

The principal argument for investing in commodities is that investing in assets that rise in price

with inflation provides a natural hedge against losses in equity and debt holdings that typically lose

value during periods of unexpected inflation [see Bodie, 1983, Greer, 1978, Halpern and Warsager,

1998, Becker and Finnerty, 2000]. While previous studies have concentrated on measuring

commodity returns during high and low inflation periods, the real benefits of commodity investment

may lie in periods of unexpected rises in inflation. Anticipated inflation, which results in high bond

yields and high equity earnings growth, may result in positive real returns for stocks and bonds. It is

the unexpected inflation that should cause concern to every serious investor. The importance of being

exposed directly to commodity price movements is due to the possibility of obtaining natural sources

of commodity return and inflation protection. In periods of unexpected inflation, market conditions

may often lead to increasing commodity prices and weakness in stocks and bonds.

Commodity Indices

One of the most attractive aspects of commodity investment today is that there are now a

number of passive indexes that are fully investible. Most alternative assets do not have a passive,

investible index, requiring the investor to select and monitor active managers. In addition to

providing a simple method to access these returns, commodity indexes have a number of other uses.

Commodity indexes are a source of information on cash commodity and futures commodity market

trends, are used as performance benchmarks for evaluation of commodity trading advisors, and

provide a historical track record useful in developing asset allocation strategies.

Commodity indices are generally based on the returns of futures contracts and/or cash markets.

Included in this group are the Dow Jones-AIG, CRB, Goldman Sachs, and MLM indices. These

indices provide returns comparable to passive long positions in listed futures contracts or, in the case

of the MLM index, of long and short positions determined by a moving average trading rule. Of

these indices, all but the CRB and Dow Jones-AIG indices are investable. The CRB is not generally

considered investable because the formula for apportioning investment across the different contract

months is too cumbersome. The Dow Jones-AIG index requires daily rebalancing of each position,

making it expensive to replicate.

Commodity indices attempt to replicate the return available to holding long positions and short in

agricultural, metal, energy, or livestock investment. Since the cost-of-carry model insures that the

return on a fully margined position in a futures contract should mimic the return on an underlying

spot deliverable, futures contract returns are often used as a surrogate for cash market performance.

Futures-contract-based commodity indices have three separate sources of return: price, roll, and

4

collateral return. Price return derives from changes in commodity futures prices. Roll return arises

from rolling long futures positions forward through time and may capture a liquidity premium

through an increased convenience yield in periods of high volatility of the underlying due to demand

and supply shocks. Collateral return assumes the full value of the underlying the futures contracts are

invested at a risk-free interest rate. This is equivalent to assuming an investor posts 100% margin

with Treasury bills.

The Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (GSCI) the object of this study - is an arithmetic

measure of the performance of actively traded, dollar-denominated nearby commodity futures

contracts. The weights assigned to individual commodities are based on a five-year moving average

of world production. Weights are determined each July and are made effective the following January.

All contracts are rolled on the fifth business day of the month prior to the expiration month of the

contract. Subindices are calculated for agricultural, energy, industrial, livestock, and precious metals

contracts. Two versions of the indices are available: a total return version, which assumes that

capital sufficient to purchase the basket of commodities is invested at the risk-free rate, and a spot

version, which only tracks movements in the futures prices. The GSCI was officially launched in

1992.

III. Data, Methodology, and Empirical Results

Methodology and Data

The methodology is similar to that conducted in previous studies by the authors [Schneeweis et

al., 1997b] as well as others [Ankrim and Hensel, 1993]. In general, these tests are consistent with

performance modeling with which both retail and institutional investors are familiar.

Monthly returns are derived for a series of stock, bond, commodity, and hedge fund indices for

the time period from January 1990 through December 2001. Data was obtained for each of the

indices and relevant subindices (GSCI), as well as the Standard and Poors 500 and MSCI World

Stock Indices, the Lehman Brothers U.S. Government/Corporate and World Bond Indices, the

EACM 100 hedge fund index, one-month Treasury bill yields, and the U.S. Consumer Price Index.

Stock, bond, commodity, currency and inflation indices are obtained from Datastream. The EACM

100 index returns are obtained from Evaluation Associates Capital Markets.

Empirical Results

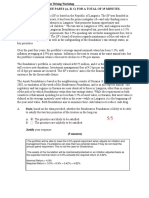

In Exhibit 1, the average monthly arithmetic returns and standard deviations of monthly

arithmetic returns, Sharpe ratios, minimum monthly returns, and correlations to the GSCI Index for

the sample of stock, bond, hedge fund and commodity indices over the January 1990 through

December 2001 period are presented, both as stand-alone investments as well as in various portfolio

groupings.

5

Exhibit 1

GSCI EACM 100 S&P 500 Lehman Gov./Corp MSCI World Lehman Global

Bond Bond

Annualized Return 3.4% 13.8% 12.9% 8.1% 6.5% 6.9%

Annualized StDev 18.5% 4.3% 14.6% 4.2% 14.6% 4.9%

Sharpe Ratio -0.11 1.94 0.51 0.63 0.08 0.31

Minimum Monthly Return -12.2% -4.4% -14.5% -2.5% -13.4% -3.0%

Correlation with GSCI 0.19 -0.04 0.02 -0.03 0.05

Portfolio I Portfolio II Portfolio III Portfolio IV Port V Port VI

S&P 500 & S&P 500, S&P 500, MSCI World, MSCI World, MSCI World,

Lehman Bond Lehman Bond Lehman Bond, Lehman Global Lehman Global, Lehman Global,

& GSCI GSCI, & GSCI GSCI,

& EACM 100 & EACM 100

Annualized Return 10.7% 9.6% 10.5% 7.0% 6.6% 7.5%

Annualized StDev 8.1% 7.4% 6.9% 8.4% 7.6% 7.1%

Sharpe Ratio 0.65 0.56 0.74 0.19 0.16 0.29

Minimum Monthly Return -6.3% -6.2% -6.0% -5.6% -5.7% -5.5%

Correlation with GSCI -0.03 0.48 0.25 -0.01 0.48 0.26

Note:

Portfolio I: 50% S&P 500 and 50% Lehman Gov./Corp. Bond

Portfolio II: 40% S&P 500, 40% Lehman Gov./Corp. Bond, and 20% GSCI

Portfolio III: 40% S&P 500, 40% Lehman Gov./Corp. Bond, 10% GSCI, and 10% EACM 100

Portfolio IV: 50% MSCI World and 50% Lehman Global Bond

Portfolio V: 40% MSCI World, 40% Lehman Global Bond, and 20% GSCI

Portfolio VI: 40% MSCI World, 40% Lehman Global Bond, 10% GSCI and 10% EACM 100

Performance 1990 - 2001

The annualized return, standard deviation, and Sharpe ratio for the GSCI composite index are

3.4 percent, 18.5 percent, and -0.11, respectively. Thus, both in absolute terms and on a risk-adjusted

basis, commodities have underperformed US and world bonds and equities as well as US real estate.

Only world real estate has registered a slightly weaker performance. Nonetheless, commodities may

produce investment benefits when considered as an addition to a diversified portfolio. The decision to

add an investment product to an existing portfolio depends on the relative means and variances of the

investment vehicle and the existing portfolio as well as the correlation between the investment

vehicle and the portfolio. The low or negative correlations of GSCI returns with returns to the S&P

500 (-0.04), Lehman Gov./Corp. Bond (0.02), and the EACM 100 (0.19) suggest such potential

benefits. Similarly, when considered as a global investment, the GSCI exhibits low or negative

correlations with the MSCI World Index (-0.03) and the Lehman Global Bond Index (0.05).

The above relationships are reflected in the performance of investment portfolios including the

GSCI. When added to a domestic portfolio of stocks and bonds, the GSCI helps reduce the standard

deviation of the portfolio from 8.1 percent to 7.4 percent. However, risk-adjusted performance

(Sharpe ratio) also decreases from 0.65 to 0.56. This is due to the effect of the 2001 period which was

dismal for physical commodities with the GSCI index losing nearly 32% of its value. Similarly, when

added to a global stock/bond portfolio, the GSCI reduces volatility from 8.4 percent to 7.6 percent

and decreases the Sharpe ratio from 0.19 to 0.16. Adding more assets such as hedge funds to the

portfolio results in improved performance.

Exhibit 2 shows the performance statistics for the GSCI component subindices. Even though the

performance is unimpressive on its own, the low or negative correlations with stock, bond, hedge

fund, and real estate indices shown in Exhibit 3 again suggest that investors who wish to target

6

particular commodity sectors may still benefit from the addition of that sector to a diversified

portfolio of assets.

Commodities as an Inflation Hedge

A significant part of the benefit of direct commodity investment is said to derive from unique

fluctuations in commodity values as a function of shifting economic forces. One such aspect of the

return process of commodities is that commodity cash prices benefit from periods of unexpected

inflation, whereas stocks and bonds suffer. As a result, commodities should provide a positive return

while other asset classes decrease in value. This premise is tested by calculating the correlation of

spot GSCI returns, as well as stock, bond, hedge fund, and real estate returns, with a proxy for

unexpected inflation. The proxy used is the monthly change in the rate of inflation.

Exhibit 2

Return St. Dev Sharpe Ratio Minimum Monthly

Return

GSCI Agricultural -2.7% 13.6% -0.59 -9.6%

GSCI Energy 4.6% 32.4% -0.03 -22.1%

GSCI Industrial Metals 1.8% 16.7% -0.21 -12.9%

GSCI Livestock 3.4% 12.8% -0.16 -10.4%

GSCI Non-Energy 0.1% 8.8% -0.60 -6.3%

GSCI Precious Metals -1.6% 11.9% -0.59 -8.6%

Performance of GSCI Subindices (1990 - 2001)

Correlations were calculated using data in months in which the change in the rate of inflation

was beyond one standard deviation from the average change. The results presented in the last column

of Exhibit 3 lend some support to the theory. Stocks and bonds do exhibit a negative correlation with

unexpected inflation (-0.22 and -0.26, respectively) and so do some commodity classes (e.g.

Agricultural and Non-Energy). However, storable commodities directly related to the intensity of

economic activity exhibit a high degree of positive correlation with unexpected inflation (0.30 for

Industrial Metals and 0.34 for Energy). Similarly, Precious Metals have a correlation of 0.34. These

results suggest that direct investing in Industrial and Precious Metals, as well as Energy may provide

a significant inflation hedge.

7

Exhibit 3

S&P 500 Lehman Bond Change in Credit Change in Change in Term Change in Change in Unexpected

Spread (Baa-Aaa) VIX Term Spread Bond vol Stk Vol Inflation

GSCI -0.04 0.02 -0.05 -0.02 -0.14 0.02 -0.07 0.31

GSCI Agricultural 0.21 -0.05 0.03 -0.24 -0.08 -0.05 -0.08 -0.35

GSCI Energy -0.08 0.02 -0.05 0.03 -0.11 0.05 -0.03 0.34

GSCI Industrial Metals 0.15 -0.12 -0.26 -0.10 0.01 -0.03 -0.09 0.30

GSCI Livestock 0.02 0.08 -0.03 -0.06 -0.01 -0.02 -0.04 -0.02

GSCI Non-Energy 0.21 -0.02 -0.08 -0.24 -0.05 -0.06 -0.13 -0.10

GSCI Precious Metals -0.10 -0.06 0.12 0.01 0.12 -0.08 -0.06 0.34

S&P 500 1.00 0.28 -0.15 -0.63 -0.11 0.10 -0.29 -0.22

Lehman Gov./Corp. Bond 0.28 1.00 -0.06 -0.12 -0.53 0.21 -0.03 -0.26

EACM 100 0.40 0.17 -0.24 -0.22 -0.09 0.02 -0.32 0.41

Note: Monthly changes in inflation beyond one standard deviation of the average are used to proxy for unexpected inflation

Factor Correlations (1990 - 2001)

Direct and Indirect Commodity Investment

It is well known that many commodity-based firms hedge their exposure to commodity price

fluctuations. As a result, investment in commodity-liked equities does not replicate the unique price-

return behavior of direct commodity investment. This issue is explored here by studying the

relationship between the return properties of commodity-linked equities (S&P 500 Agricultural

Products, Metals Mining, Energy, and Gold and Precious Metals Mining) and the corresponding

GSCI indices. Returns to the four pairs of indices above were ranked in ascending order according to

the GSCI indices. Exhibit 4 shows plots of the indices in each of the groups. It is apparent from the

plots that often direct investment in commodities can provide a positive return when commodity-

linked stocks lose money. Clearly, direct commodity investment can provide downside portfolio

protection in this sense.

Roll Return

Finally, futures-based commodity investment can benefit from increased roll returns in periods

of increased volatility of the underlying commodity and backwardation. For example, monthly roll

returns on the GSCI Composite index were ranked against the intra-month volatility of the GSCI

Composite spot price index. Exhibit 5-a shows a clear upward trend in average roll return with

increasing intra-month spot volatility in the Composite index. Exhibit 5-b contains similar graphs for

the six GSCI subindices. The described relationship between spot volatility and roll return is not

observed for all commodity groups, but it is quite pronounced in the cases of Energy and Industrial

Metals. This explains why the effect is observed in the Composite index as these groups dominate the

index.

8

Exhibit 4

Mean roll returns and standard deviations for the Composite index and the six subindices in the

least volatile and the most volatile 36 months (spot price volatility is meant here) are presented in the

second and third columns of Exhibit 6, respectively. For each index, F-tests were run for equal

variances of roll returns in the least volatile and the most volatile 36 months. Next, we tested for

equality of the means of roll returns in each index/subindex pair, assuming either equal variance or

unequal variance, depending on the results from the F-tests. The p-values of the variance and mean

tests are presented in the last two columns of Exhibit 6.

As previously suggested by the graphs, mean roll returns for the Energy and Industrial Metals

subindices, as well as the GSCI Composite Index, significantly increase and are positive with

increased spot volatility. In contrast, mean roll return for the Livestock subindex decreases and

becomes negative. The effect of spot price volatility on the mean roll return of the Agricultural, Non-

Energy, and Precious Metals subindices is insignificant. In general, the effect is more pronounced for

non-perishable, storable commodities, whose convenience yield rises in periods of increased

volatility due to demand and supply shocks.

IV. Conclusions

In recent years, investible commodity indices and commodity linked assets have increased the

number of available commodity-based products. This paper has shown that direct commodity

investment can provide significant portfolio diversification benefits beyond those achievable from

commodity-based stock and bond investment. These benefits stem from the unique exposure of

commodities to markets forces such as unexpected inflation as well the potential of a

Ranked on GSCI (1990-2001): Agriculture

-25.0%

-20.0%

-15.0%

-10.0%

-5.0%

0.0%

5.0%

10.0%

15.0%

20.0%

25.0%

30.0%

1 6 11 16 21 26 31 36 41 46 51 56 61 66 71 76 81 86 91 96

S&P

Agriculture

GSCI

Agricultural

Products

(Spot)

Ranked on GSCI (1990-2001): Energy

-30.0%

-20.0%

-10.0%

0.0%

10.0%

20.0%

30.0%

40.0%

1 10 19 28 37 46 55 64 73 82 91 100 109 118 127 136

S&P Energy

GSCI Energy

(Spot)

Ranked on GSCI (1990-2001): Industrial Metals

-30.0%

-20.0%

-10.0%

0.0%

10.0%

20.0%

30.0%

40.0%

1 10 19 28 37 46 55 64 73 82 91 100 109 118 127 136

S&P Metals

Mining

GSCI Ind.

Metals (Spot)

Ranked on GSCI (1990-2001): Precious Metals

-30.0%

-20.0%

-10.0%

0.0%

10.0%

20.0%

30.0%

40.0%

50.0%

60.0%

70.0%

1 10 19 28 37 46 55 64 73 82 91 100 109 118 127 136

S&P Gold &

Prec. Metals

GSCI

Precious

Metals (Spot)

9

positive roll return in futures-based commodity investment in periods of high spot price volatility.

Adding a commodity component to a diversified portfolio of assets has been demonstrated to results

in enhanced risk-adjusted performance. We believe that this research would place the use of

investible commodity indices as a central part of the institutional investors asset allocation decision.

The present research can be extended by studying the potential benefits of active trading in

various commodity indices. Also, future studies might consider the impact of alternative asset

allocation strategies under varying market conditions (e.g., business cycle) and the impact of

investment into commodity linked-products or investible commodity indices under these economic

conditions.

Exhibit 5-a

GSCI Composite Roll Return Ranked on Spot Volatility

(1990-2001)

0.0%

10.0%

20.0%

30.0%

40.0%

50.0%

60.0%

70.0%

80.0%

1 8 15 22 29 36 43 50 57 64 71 78 85 92 99 106 113 120 127 134 141

-5.0%

-4.0%

-3.0%

-2.0%

-1.0%

0.0%

1.0%

2.0%

3.0%

4.0%

5.0%

GSCI Spot

Intramonth

St.Dev.

GSCI Monthly

Roll Return

10

Exhibit 5-b

Exhibit 6

Mean St.Dev. Mean St.Dev. P-Value (one-tail) P-Value (one-tail)

Composite -0.23% 0.984% 0.59% 1.747% 0.051% 1.775%

Agricultural 0.01% 0.941% 0.10% 1.753% 0.020% 77.784%

Energy -0.57% 1.649% 1.22% 2.811% 0.109% 0.165%

Industrial Metals -0.24% 0.369% 0.40% 1.680% 0.000% 3.373%

Livestock -0.11% 1.854% -0.43% 1.923% 23.782% 46.899%

Non-Energy -0.16% 0.932% -0.02% 1.153% 10.669% 58.147%

Precious Metals -0.25% 0.332% -0.30% 0.381% 20.733% 55.782%

GSCI Roll Return Ranked on Monthly Spot Standard Deviation (1990-2001): Statistics and Tests

Least Volatile 36 Months Most Volatile 36 Months H0: Equal St.Dev H0: Equal Means

GSCI Agricultural Roll Return Ranked on Spot Volatility (1990-2001)

0.0%

5.0%

10.0%

15.0%

20.0%

25.0%

30.0%

1 8 15 22 29 36 43 50 57 64 71 78 85 92 99 106 113 120 127 134 141

-6.0%

-4.0%

-2.0%

0.0%

2.0%

4.0%

6.0%

GSCI Spot

Intramonth

St.Dev.

GSCI Monthly

Roll Return

GSCI Energy Roll Return Ranked on Spot Volatility (1990-2001)

0.0%

10.0%

20.0%

30.0%

40.0%

50.0%

60.0%

70.0%

80.0%

90.0%

1 8 15 22 29 36 43 50 57 64 71 78 85 92 99 106 113 120 127 134 141

-10.0%

-8.0%

-6.0%

-4.0%

-2.0%

0.0%

2.0%

4.0%

6.0%

8.0%

GSCI Spot

Intramonth

St.Dev.

GSCI Monthly

Roll Return

GSCI Industrial Metals Roll Return Ranked on Spot Volatility (1990-2001)

0.0%

5.0%

10.0%

15.0%

20.0%

25.0%

30.0%

35.0%

40.0%

1 8 15 22 29 36 43 50 57 64 71 78 85 92 99 106 113 120 127 134 141

-2.0%

-1.0%

0.0%

1.0%

2.0%

3.0%

4.0%

5.0%

6.0%

7.0%

8.0%

GSCI Spot

Intramonth

St.Dev.

GSCI Monthly

Roll Return

GSCI Livestock Roll Return Ranked on Spot Volatility (1990-2001)

0.0%

5.0%

10.0%

15.0%

20.0%

25.0%

30.0%

1 8 15 22 29 36 43 50 57 64 71 78 85 92 99 106 113 120 127 134 141

-8.0%

-6.0%

-4.0%

-2.0%

0.0%

2.0%

4.0%

6.0%

GSCI Spot

Intramonth

St.Dev.

GSCI Monthly

Roll Return

GSCI Non-Energy Roll Return Ranked on Spot Volatility (1990-2001)

0.0%

2.0%

4.0%

6.0%

8.0%

10.0%

12.0%

14.0%

16.0%

1 7 13 19 25 31 37 43 49 55 61 67 73 79 85 91 97 103 109 115 121 127 133 139

-4.0%

-3.0%

-2.0%

-1.0%

0.0%

1.0%

2.0%

3.0%

4.0%

GSCI Spot

Intramonth

St.Dev.

GSCI Monthly

Roll Return

GSCI Precious Metals Roll Return Ranked on Spot Volatility (1990-2001)

0.0%

5.0%

10.0%

15.0%

20.0%

25.0%

30.0%

35.0%

40.0%

1 7 13 19 25 31 37 43 49 55 61 67 73 79 85 91 97 103 109 115 121 127 133 139

-2.0%

-1.5%

-1.0%

-0.5%

0.0%

0.5%

GSCI Spot

Intramonth

St.Dev.

GSCI Monthly

Roll Return

11

Bibliography

Ankrim, E. and C. Hensel, Commodities in Asset Allocation: A Real-Asset Alternative to Real Estate,

Financial Analysts Jourrnal, May-June 1993, 20-29.

Anson, M., Spot returns, Roll Yield, and Diversification with Commodity Futures," The Journal of

Alternative Investments, December 1998, pp

Becker, K., and J. Finnerty, Indexed Commodity Futures and the Risk and Return of Institutional

Portfolios, OFOR Working Paper, 2000.

Bodie, Z., and V. Rosansky, "Risk and Return in Commodity Futures," Financial Analysts Journal,

36, May-June 1980, 3-14.

Bodie, Z., Commodity Futures as a Hedge against Inflation, The Journal of Portfolio Management,

Spring 1983, pp. 12-17.

Chung, S., Effects of Derivative Usage on Commodity-Based Corporations, Ph.D. Dissertation,

University of Massachusetts, 2000.

Culp, C. and M. Miller, Metallgesellschaft and the Economics of Synthetic Storage, Journal of

Applied Corporate Finance, Winter 1995, pp. 62-75.

Fama, E. and K. French, Commodity Future Prices: Some Evidence of Forecast Power, Premiums,

and the Theory of Storage, The Journal of Business, vol. 60, no. 1, 1987, pp. 55-73.

Fama, Eugene and Kenneth French, "Business Cycles and The Behavior of Metals Prices," Journal of

Finance, Vol. 43, no. 5, December 1988.

Froot, K., "Hedging Portfolios with Real Assets", Journal of Portfolio Management, Summer 1995,

pp. 60-77.

Greer, R. J., Conservative Commodities: A Key Inflation Hedge, The Journal of Portfolio

Management, Summer 1978.

Greer, Robert J. Methods for Institutional Investment in Commodity Futures, The Journal of

Derivatives, Winter 1994, pp. 28-36

Halpern, P. and R. Warsager., The Performance of Energy and Non-Energy Based Commodity

Investment Vehicles in Periods of Inflation, The Journal of Alternative Investments, Summer 1998,

pp. 75-81.

Hotelling, H., "The Economics of Exhaustible Resources", Journal of Political Economy, 1931.

Huberman, G., The Desireability of Investment in Commodities via Commodity Futures,

Derivatives Quarterly, Fall 1995, pp. 65-67

12

Kaldor, N., Speculation and economic stability, Review of Economic Studies 7, 1939, pp. 1-27.

Kaplan, P. D. and S. Lummer, GSCI Collateralized Futures as a Hedging and Diversification Tool

for Institutional Portfolios: an Update, working paper, Ibbotson Associates 1997.

Kolb, R., "Is Normal Backwardation Normal," The Journal of Futures Markets, Vol. 12, No. 1

February 1992, 75-91.

Litzenberger, R. and N. Rabinowitz, Backwardation in Oil Futures Markets: Theory and Empirical

Evidence, The Journal of Finance, December 1995, pp. 1517-1545.

New York Stock Exchange, Commodity Futures as an Asset Class, Report by Powers Research

Associates, January 1990.

Routledge, B., D. Seppi, and C. S. Spatt, Equilibrium Forward Curves for Commodities, Journal of

Finance, Vol. LV, No. 3, June 2000, pp. 1297-1338.

Satyanarayan, S. and P. Varangis, Diversification Benefits of Commodity Assets in Global

Portfolios, Journal of Investing, Spring 1996, pp. 69-78.

Schneeweis, T., U. Savanayana, and D. McCarthy, "Alternative Commodity Trading Vehicles: A

Performance Analysis," Journal of Futures Markets, August 1991, 475-490.

Schneeweis, T. and R. Spurgin, Comparisons of Commodity and Managed Futures Benchmark

Indexes, The Journal of Derivatives, Summer 1997a, pp. 33-50.

Schneeweis, T. and R. Spurgin, Energy Based Investment Products and Investor Asset Allocation,

CIDSM/SOM, University of Massachusetts, 1997 b.

Schneeweis, T., and R. Spurgin, The Benefits of The LMEX Index for Active Trading, Working

Paper, University of Massachusetts/CISDM, September 2000.

Schneeweis, T., R. Spurgin, and G. Georgiev, The LMEX and Asset Allocation: the Economic

Foundations for Investment into Base Metals, Working Paper, University of Massachusetts/CISDM,

December 2000.

Strongin, S., and M. Petsch, Commodity Investing: Long-Run Returns and the Function of Passive

Capital, Derivatives Quarterly, Fall 1995, pp. 56-64.

Telser, L. G., Futures trading and the storage of cotton and wheat, Journal of Political

Economy 66, 1958, pp. 133144.

Williams, J. C., and B. D. Wright, Storage and Commodity Markets, Cambridge University Press,

1991.

13

Working, H., Theory of the inverse carrying charge in futures markets, Journal of Farm

Economics, 30, 1948, pp.128.

Working, H., The theory of the price of storage, American Economic Review, 39, 1949, pp. 1254

1262.

Вам также может понравиться

- Commodity Index InvestingДокумент69 страницCommodity Index InvestingMayankОценок пока нет

- 2022 Ijmef-109135Документ26 страниц2022 Ijmef-109135Vikas PandeyОценок пока нет

- Multi-Asset Factor Investing: Master ThesisДокумент39 страницMulti-Asset Factor Investing: Master ThesisJuan Sebastian CardonaОценок пока нет

- WP 78 RiddioДокумент47 страницWP 78 RiddioIrenataОценок пока нет

- Ijrar Issue 20542305Документ10 страницIjrar Issue 20542305Manjunath NayakaОценок пока нет

- MPRA Paper 29862Документ21 страницаMPRA Paper 29862arjittripathi02Оценок пока нет

- American Finance AssociationДокумент26 страницAmerican Finance AssociationSanjita ParabОценок пока нет

- Fernandez2006 PDFДокумент17 страницFernandez2006 PDFCristhianRosadioAranibarОценок пока нет

- Disposition Effect and Multi-Asset Market DynamicsДокумент21 страницаDisposition Effect and Multi-Asset Market DynamicsWihelmina DeaОценок пока нет

- 62-Article Text (FULL, With Biographies) - 299-1-10-20150226Документ14 страниц62-Article Text (FULL, With Biographies) - 299-1-10-20150226Rahi vermaОценок пока нет

- 5 Zib Vol2 Issue4Документ22 страницы5 Zib Vol2 Issue4John CarpenterОценок пока нет

- BIS Working Papers: No 952 Passive Funds Affect Prices: Evidence From The Most ETF-dominated Asset ClassesДокумент67 страницBIS Working Papers: No 952 Passive Funds Affect Prices: Evidence From The Most ETF-dominated Asset Classes5ty5Оценок пока нет

- Why Do We Need DerivativesДокумент4 страницыWhy Do We Need DerivativesAnkit AroraОценок пока нет

- 3116 Paper Nkr2saNhДокумент53 страницы3116 Paper Nkr2saNhMiguel Angel Montoya FigueroaОценок пока нет

- A Study On Financial Derivatives (Futures) With Reference Karvy Stock Broking LTDДокумент6 страницA Study On Financial Derivatives (Futures) With Reference Karvy Stock Broking LTDSauravОценок пока нет

- What Makes The VIX Tick PDFДокумент59 страницWhat Makes The VIX Tick PDFmititeiОценок пока нет

- Financialization of CommodityДокумент49 страницFinancialization of CommodityWeldone SawОценок пока нет

- Bond Returns ReexaminedДокумент3 страницыBond Returns Reexaminedmonty_zОценок пока нет

- Predictability of Equity Reit Returns: Implications For Property Tactical Asset AllocationДокумент24 страницыPredictability of Equity Reit Returns: Implications For Property Tactical Asset AllocationKarburatorОценок пока нет

- Katakana VietnameseДокумент21 страницаKatakana VietnamesegorrielleyОценок пока нет

- Journal of Empirical FinanceДокумент30 страницJournal of Empirical FinanceElena FlorescuОценок пока нет

- Bessler 2015Документ58 страницBessler 2015Arief RachmansyahОценок пока нет

- Stock Market Analysis: A Review and Taxonomy of Prediction TechniquesДокумент22 страницыStock Market Analysis: A Review and Taxonomy of Prediction TechniquesSadeen MobinОценок пока нет

- Stock Market Analysis: A Review and Taxonomy of Prediction TechniquesДокумент22 страницыStock Market Analysis: A Review and Taxonomy of Prediction TechniquesNikhil AroraОценок пока нет

- Inflation-Hedging Portfolios in Different Inflation Regimes: M. Brière and O. SignoriДокумент9 страницInflation-Hedging Portfolios in Different Inflation Regimes: M. Brière and O. Signorihershie5252Оценок пока нет

- An Intermarket Approachto Beta Rotationthe 2014 Dow Award WinnerДокумент16 страницAn Intermarket Approachto Beta Rotationthe 2014 Dow Award WinnerBruno Constante GoedertОценок пока нет

- Exploring The Volatility of Stock Markets: Indian ExperienceДокумент15 страницExploring The Volatility of Stock Markets: Indian ExperienceShubham GuptaОценок пока нет

- The Impact of Interest Rate Policy On Stock Market Bubbles and Trading BehaviorДокумент31 страницаThe Impact of Interest Rate Policy On Stock Market Bubbles and Trading BehaviorshahsahbОценок пока нет

- Index Investment and Financialization of Commodities: Ke Tang and Wei XiongДокумент46 страницIndex Investment and Financialization of Commodities: Ke Tang and Wei Xiongmylife123Оценок пока нет

- MR 2023 42-3 Jul 02engДокумент24 страницыMR 2023 42-3 Jul 02engsonia969696Оценок пока нет

- Analysis of Liquidity-Study On Indian Mid-Cap StocksДокумент14 страницAnalysis of Liquidity-Study On Indian Mid-Cap Stockssunil601Оценок пока нет

- Optimal Momentum - A Global Cross Asset ApproachДокумент28 страницOptimal Momentum - A Global Cross Asset ApproachJeffStelling1Оценок пока нет

- Portfolio Management in RecessionsДокумент6 страницPortfolio Management in RecessionsNovelty JournalsОценок пока нет

- Value Vs Growth An Evidence From German Stock MarketДокумент13 страницValue Vs Growth An Evidence From German Stock MarketAyesha SiddikaОценок пока нет

- Liquidity and Asset PricesДокумент74 страницыLiquidity and Asset PricesHiru RodrigoОценок пока нет

- Diversification Benefits From Investing in Commodity Sector: The Case of Precious Metals, Industrial Metals & Agricultural ProduceДокумент12 страницDiversification Benefits From Investing in Commodity Sector: The Case of Precious Metals, Industrial Metals & Agricultural Producedrmanhattan61075Оценок пока нет

- Determinants of Bear Market Performance: Acase of The Nairobi Securities Exchange in KenyaДокумент17 страницDeterminants of Bear Market Performance: Acase of The Nairobi Securities Exchange in KenyaAnonymous CwJeBCAXpОценок пока нет

- Mutual Funds 5Документ53 страницыMutual Funds 5Saddam AwanОценок пока нет

- Financial ReportingДокумент2 страницыFinancial ReportingbiswamohanjenaОценок пока нет

- 10 1016@j Ribaf 2017 07 124Документ40 страниц10 1016@j Ribaf 2017 07 124sonia969696Оценок пока нет

- 06 - Chapter 2Документ33 страницы06 - Chapter 2abhaypratap8435Оценок пока нет

- Herd BehaviorДокумент14 страницHerd BehaviorMarii KhanОценок пока нет

- Property Derivatives For Managing European Real-Estate Risk: Frank J. FabozziДокумент19 страницProperty Derivatives For Managing European Real-Estate Risk: Frank J. FabozziVictor GutierrezОценок пока нет

- Hedging Real-Estate RiskДокумент27 страницHedging Real-Estate RiskStonerОценок пока нет

- Bubbles, Froth, and Facts: The Impact of Index Funds On Commodity Futures PricesДокумент26 страницBubbles, Froth, and Facts: The Impact of Index Funds On Commodity Futures Pricesmgazall@rcgdirect.comОценок пока нет

- Market Dispersion and The Pro Tability of Hedge FundsДокумент35 страницMarket Dispersion and The Pro Tability of Hedge FundsJeremy CanlasОценок пока нет

- Singh, Kumar - 2008 - Volatility Modeling, Seasonality and Risk-Return Relationship in GARCH-In-Mean Framework The Case of Indian Stock-AnnotatedДокумент35 страницSingh, Kumar - 2008 - Volatility Modeling, Seasonality and Risk-Return Relationship in GARCH-In-Mean Framework The Case of Indian Stock-AnnotatedPrabu NirvanaОценок пока нет

- Discussion Papers: Search-Based Endogenous Illiquidity and The MacroeconomyДокумент49 страницDiscussion Papers: Search-Based Endogenous Illiquidity and The Macroeconomypathanfor786Оценок пока нет

- Explaining Asset Prices: Nobel Prize in Economics 2013: by Dr. Paramita MukherjeeДокумент4 страницыExplaining Asset Prices: Nobel Prize in Economics 2013: by Dr. Paramita MukherjeeParomita Adhya MukherjeeОценок пока нет

- Research On The Factors Affecting Stock Price Volatility: Sijia Li Yuping Wang Zifan Zhang Yiming ZhuДокумент6 страницResearch On The Factors Affecting Stock Price Volatility: Sijia Li Yuping Wang Zifan Zhang Yiming ZhuSaira Ishfaq 84-FMS/PHDFIN/F16Оценок пока нет

- COT Energy Futures Prices and Commodity Index Investment From Big Funds Level - Universitiy Illinois - DFДокумент44 страницыCOT Energy Futures Prices and Commodity Index Investment From Big Funds Level - Universitiy Illinois - DFDraženSОценок пока нет

- Aepp/ppq 032Документ31 страницаAepp/ppq 032sonia969696Оценок пока нет

- Redeploy UncertaintyДокумент60 страницRedeploy UncertaintyOyewande ToyinОценок пока нет

- Liquidity and Volatility Commonality in The Canadian Stock MarketДокумент20 страницLiquidity and Volatility Commonality in The Canadian Stock MarketAzo DarnisОценок пока нет

- Neural Network Models For Forecasting Mutual Fund Net Asset ValueДокумент18 страницNeural Network Models For Forecasting Mutual Fund Net Asset ValueClara Agustin StephaniОценок пока нет

- Short Selling, Informational Efficiency, and Extreme Stock Price Adjustment China BasedДокумент20 страницShort Selling, Informational Efficiency, and Extreme Stock Price Adjustment China BasedAbhishree JainОценок пока нет

- Market Microstructure Term PaperДокумент20 страницMarket Microstructure Term PaperMburu SОценок пока нет

- Correlation and Volatility Dynamics in InternationДокумент24 страницыCorrelation and Volatility Dynamics in InternationSafuan HalimОценок пока нет

- EIB Working Papers 2019/11 - Macro-based asset allocation: An empirical analysisОт EverandEIB Working Papers 2019/11 - Macro-based asset allocation: An empirical analysisОценок пока нет

- Analyzing the Fair Market Value of Assets and the Stakeholders' Investment DecisionsОт EverandAnalyzing the Fair Market Value of Assets and the Stakeholders' Investment DecisionsОценок пока нет

- Artigo PDFДокумент21 страницаArtigo PDFvivhansonОценок пока нет

- An Hedonic Analysis of American CollectableДокумент18 страницAn Hedonic Analysis of American CollectablevivhansonОценок пока нет

- Social Determinants of HealthДокумент27 страницSocial Determinants of HealthDensearn Seo100% (5)

- Academic Publishing FutureДокумент14 страницAcademic Publishing FuturevivhansonОценок пока нет

- Asset Allocation and Diversification Returns: MARCH 1994Документ7 страницAsset Allocation and Diversification Returns: MARCH 1994vivhansonОценок пока нет

- Antoniou and Garret (1993)Документ19 страницAntoniou and Garret (1993)Viviane ASОценок пока нет

- Financial Crises in Efficient MarketsДокумент25 страницFinancial Crises in Efficient MarketsvivhansonОценок пока нет

- Baffes and HaniotisДокумент42 страницыBaffes and HaniotisvivhansonОценок пока нет

- 330 S12 IndSty MT AMongelluzzoДокумент8 страниц330 S12 IndSty MT AMongelluzzomongo9279Оценок пока нет

- 10 Principles of Basic Financial ManagementДокумент7 страниц10 Principles of Basic Financial ManagementJeyavikinesh Selvakkugan100% (3)

- Uranium Insider PRO Q2 2020 PDFДокумент48 страницUranium Insider PRO Q2 2020 PDFv0idinspace100% (1)

- Power of 3 JPMAMДокумент28 страницPower of 3 JPMAMAnup Jacob JoseОценок пока нет

- Preferred Stock and Common StockДокумент22 страницыPreferred Stock and Common StockSaMeia FarhatОценок пока нет

- Performance Evaluation of ICB Mutual FundsДокумент61 страницаPerformance Evaluation of ICB Mutual FundsDidar Rikhon100% (1)

- Notes On The Revised Corporation CodeДокумент34 страницыNotes On The Revised Corporation CodeZuleira Parra100% (9)

- B, Com Calicut SyllaBUSДокумент79 страницB, Com Calicut SyllaBUSjahfarОценок пока нет

- ABC Analysis For Final Subjects PDFДокумент15 страницABC Analysis For Final Subjects PDFCA Test Series100% (1)

- HBS - Pitcairn Family Heritage (R) Fund PDFДокумент16 страницHBS - Pitcairn Family Heritage (R) Fund PDFAngelo LauriОценок пока нет

- IAET Case 5Документ14 страницIAET Case 5HADTUGIОценок пока нет

- What Does The DFL of 3 Times Imply?Документ7 страницWhat Does The DFL of 3 Times Imply?Sushil ShresthaОценок пока нет

- SodikoffДокумент10 страницSodikoffAnn DwyerОценок пока нет

- General Counsel in New York NY Resume Adele FreedmanДокумент3 страницыGeneral Counsel in New York NY Resume Adele FreedmanAdeleFreedmanОценок пока нет

- Cash Flow AnalysisДокумент75 страницCash Flow AnalysisBalasingam PrahalathanОценок пока нет

- CR Workshop Q11-20 Ryan Ebner SDДокумент26 страницCR Workshop Q11-20 Ryan Ebner SDRyan EbnerОценок пока нет

- MayTag Corp - Understanding of Financial StatementДокумент16 страницMayTag Corp - Understanding of Financial StatementMirza JunaidОценок пока нет

- Rich at 26 - Alexis AssadiДокумент178 страницRich at 26 - Alexis AssadiDavid100% (3)

- Introduction To Business Combinations: Summary of Items by TopicДокумент30 страницIntroduction To Business Combinations: Summary of Items by TopicKyla Ramos DiamsayОценок пока нет

- The Nairobi Stock Exchange (NSE) Sectors ReconfiguredДокумент5 страницThe Nairobi Stock Exchange (NSE) Sectors ReconfiguredPatrick Kiragu Mwangi BA, BSc., MA, ACSIОценок пока нет

- Bba Training ReportДокумент64 страницыBba Training ReportNourin KhanОценок пока нет

- Risk, Return & Capital BudgetingДокумент12 страницRisk, Return & Capital BudgetingIrfan ShakeelОценок пока нет

- IDLC Finance LTD OverviewДокумент13 страницIDLC Finance LTD OverviewKhan Mohammad ShahadatОценок пока нет

- PNJ Update 20201207Документ7 страницPNJ Update 20201207Khoa PhamОценок пока нет

- Entrepreneurial Exit As A Critical Component of The Entrepreneurial ProcessДокумент13 страницEntrepreneurial Exit As A Critical Component of The Entrepreneurial Processaknithyanathan100% (2)

- Corporation Law: Atty. Divina's Highlights of The Revised Corporation Code (Zoom Lecture and Book)Документ14 страницCorporation Law: Atty. Divina's Highlights of The Revised Corporation Code (Zoom Lecture and Book)Joesil DianneОценок пока нет

- Cash Flow AnalysisДокумент6 страницCash Flow AnalysisMa Jessica Maramag BaroroОценок пока нет

- GSIS Law 1Документ13 страницGSIS Law 1Arbie Dela TorreОценок пока нет

- Signaling TheoryДокумент7 страницSignaling TheorysaharsaeedОценок пока нет

- Investor Profile QuestionnaireДокумент4 страницыInvestor Profile QuestionnaireVОценок пока нет