Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Nigerian

Загружено:

Yahiko YamatoАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Nigerian

Загружено:

Yahiko YamatoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Subject: Afro-Asian Literature (Eng 103) Instructor: Prof. Joyce C.

Castillo I Reporter: Dona Gongora (BSEd 2) Topic: Nigergian

Literature

Introduction: Nigeria is the country which has the greatest literary output in Africa. There are over fifty notable literary artists currently active and the sheer volume of the literature far exceeds that of any other black African country. Political independence in 1960 brought in its wake a great awareness of the problems of building a nation out of the diverse ethnic entities which make up the huge conglomerate called Nigeria. This fact has dominated a sizeable portion of the literature espe cially in the early years of independence. The literature in question is written literature in contradistinction from oral literature or oration, and it is in English and some Nigerian languages. At present, Nigerian literature in English is the one which attracts greater attention and has the greater influence nationally and internationally. This prominence is because the literature has been produced by the new westernized elite who often have greater literary competence in English than in their indigenous languages. Although some highly literate Nigerians (for example Professor Akin Isola) have chosen to write in their indigenous languages rather than English, the number of writers who have made such a choice is very small indeed. Nigerian literature in English has raised more issues relevant to our contemporary situation than the literature in indigenous Nigerian languages. Whereas the latter has largely been anchored to the past, invoking images and symbols of our rich heritage, literature in English has aligned itself more forcefully and with greater artistic profit to the wide and more diverse literature of the world. Thus, it is the Nigerian literature in English, far more than its indigenous language counterpart, that has raised issues of culture-contact and culture-conflict, the place of tradition in the modern ethos, the problems of the administration of a modern polity, as well as notions of sexism and the place of the womenfolk in our new reality. It has also been concerned with the way forward if the Nigerian nation is to recover from its present problems, realize its full potentials and become a member of the comity of prosperous nations.

History: Pre-literate Nigeria once enjoyed a verbal art civilization which, at its high point, was warmly patronized by traditional rulers and the general public. At a period when writing was unknown, the oral medium served the people as a bank for the preservation of their ancient experiences and beliefs. Much of the evidence that related to the past of Nigeria, therefore, could be found in oral traditions. Although most Nigerians knew and could recount parts of their genealogy and local history, only a few oral artists have the skill and stamina required to chant the lengthy oral literature. The oral artists, freelancers or guild-associates, enjoyed reverence as "keepers of the people's ancient wisdoms and beliefs." These oral artists frequently entertained their audiences dramatically, providing relaxation and teaching moral lessons. In Yorubaland, "as a means of relaxation, farmers gather their children and sit under the moon for tale-telling. . . .The telling of stories is used by narrators to instruct the young and teach them to respect the dictates of their custom: as a result, a large body of moral instruction, of societal values and norms are preserved for posterity by the Yoruba." Western influences began affecting Nigerian literature as early as the eighth century AD when Arabic ideas and culture were introduced to Africa. During the fourteenth century, written and spoken Arabic flourished in northern Nigeria and by the seventeenth century, some Hausa literature had been translated into Arabic. Christian missionaries accelerated the importation of western education into Nigeria during the nineteenth century. Some native black Moslems met the threat of white Christians with protests in poetry. Aliyu dan Sidi, for example, utilized the oral literature tradition to write poetic protests against the missionaries. However, other Yoruba authors, such as D.O. Faguna and Isaac Delano, wrote novels promoting the missionaries and teaching the Christian religion. Although Faguna and Delano offered Christian religious instruction and preached acceptance of western ideas, both relied heavily upon their ancestral folktales in creative writing. Faguna's pieces in particular "show and extensive use of proverbs, riddles, traditional jokes and other lore central to Yoruba belief." In various parts of the country, novels developed around 1930. Centered upon fantastic, magical characters of humans and fairies, Hausa novels, called "non-realistic novels," were based on folktales. The "mysterious" characters transmuted into other beings; fairies, animals, and humans all conversed among one another. Of Muhammadu Bello's fantasy novel Gandoki, Ajuwon comments, "One is led to say that the book is a reduction of Hausa oral tradition to written literature." In the 1930's, Igboland also saw a growth in the number of novelists who expressed the distaste of their people for the Christian missionaries. While poetry of that persuasion emphasized religious devotion to Allah (shunning the Christian god), Pita Mwana's 1935 prize-winning book, Omenuko, shows the style of a anti-missionary "didactic intention" underlying a fantasy novel. A major shift in literary style from fantasy to realism resulted from the founding of the University College of Ibadan in 1948. The calls for a new literary style came from scholars educated in the western tradition at the University. Conferences, journals, and newspapers urged the shift to realism; when the Ministry of Education sponsored a novel-writing competition in 1963, "the kind of story they wanted to see was the story that dealt with the kind of things we could see with our eyes in

Nigeria today." Yoruba writers of the time reacted appropriately, eliminating the fairies in favor of human characters, omitting the animal-to-human conversation found in the non-realistic literature. Leaving behind group-specific references and literature styles, the authors worked with broader themes. "Thus a new literary tradition was being adopted by many Yoruba novelists; they dealt with such universal themes as religion, labor, corruption, and justice; they employed human characters and concrete symbols."

Type of text: Nigerians have cultivated virtually every known genre of literature including fiction, poetry, drama, the travelogue, biography and autobiography. Nevertheless, the emphasis here will be on prose fiction, poetry and drama in which they have made very significant literary achievements.

Languages:

There are hundreds of languages spoken in Nigeria. The official language of Nigeria, English, the former colonial language, was chosen to facilitate the cultural and linguistic unity of the country. English remains an exclusive preserve of the country's urban elite, and is not widely spoken in rural areas, which comprise three quarters of the country's population. The other major languages are Hausa, Igbo, Yoruba, Ibibio, Edo, Fulfulde, and Kanuri. Nigeria's linguistic diversity is a microcosm of Africa as a whole, encompassing three major African languages families: Afroasiatic, Nilo-Saharan, and NigerCongo. Nigeria also has several as-yet unclassified languages, such as Cen Tuum, which may represent a relic of an even greater diversity prior to the spread of the current language families.

Religion: There exist several religions in Nigeria, helping to accentuate regional and ethnic distinctions. All religions represented in Nigeria were practiced in every major city in 1990. However, Islam dominated the north and had a number of supporters in the South Western, Yoruba part of the country. Nigeria has the largest Muslim population in sub-Saharan Africa. Protestantism and local syncretic Christianity are also in evidence in Yoruba areas, while Catholicism dominates the Igbo and closely related areas. Both Protestantism and Catholicism dominated in the Ibibio, Annang, and the Efik kiosa lands.

Writers: Achebe's first novel, Things Fall Apart, published in 1958, details the tragic disintegration of Igbo clans upon the arrival of the Europeans. Igbo folklore saturates the novel, preserving the African elements despite the English prose. Soyinka earned his international reputation as a novelist, although later, he became better known for his drama and poetry. The poetry in the collection A Shuttle in the Crypt, echoes with elements of older Nigerian literature. The repetition found in "O Roots!" recalls the ritualistic chanting of the oral literature. Both "O Roots!" and "When Seasons Change" dwell upon the images of ancestral generations and the souls of ancient Nigerians, reflective of the purpose of the oral literature of keeping family and local histories alive. Although Soyinka's poetry in A Shuttle in the Crypt encompasses many themes and techniques of modernists, nevertheless, reverberates with the Nigerian oral and written literary traditions. Buchi Emecheta (born 21 July 1944, in Lagos) is a Nigerian novelist who has published over 20 books, including Second-Class Citizen (1974), The Bride Price (1976), The Slave Girl (1977) and The Joys of Motherhood (1979). Her themes of child slavery, motherhood, female independence and freedom through education have won her considerable critical acclaim and honors, including an Order of the British Empire in 2005. Emecheta once described her stories as "stories of the world where women face the universal problems of poverty and oppression, and the longer they stay, no matter where they have come from originally, the more the problems become identical."

Elechi Amadi (born 12 May 1934) is a Nigerian author of plays and novels that are generally about African village life, customs, beliefs and religious practices, as they were before contact with the Western world. Amadi is best regarded for his 1966 first novel, The Concubine, which has been called "an outstanding work of pure fiction". He worked for a time as a land surveyor and later was a teacher at several schools, including the Nigerian Military School, Zaria (1963-1966). Amadi did military service in the Nigerian army and was on the Nigerian side during the Nigeria-Biafra War, retiring in the rank of Captain. After the war Amadi left the army to work for the Rivers State government. Positions he held include Permanent Secretary (19731983), Commissioner for Education (1987-1988) and Commissioner for Lands and Housing (1989-1990).

People: The Nigerian culture is shaped by Nigeria's multiple ethnic groups. The country has over 50 languages and over 250 dialects and ethnic groups. The three largest ethnic groups are the Hausa-Fulani who are predominant in the north, the Igbo who are predominant in the southeast, and the Yoruba who are predominant in the southwest.

The Edo people are predominant in the region between Yorubaland and Igboland. Much of the Edo tend to be Christian while the remaining 25 percent worship deities called Ogu. This group is followed by the Ibibio/Annang/Efik people of the coastal southeastern Nigeria and the Ijaw of the Niger Delta.

Culture: The music of Nigeria includes many kinds of folk and popular music, some of which are known worldwide. Traditional musicians use a number of diverse instruments, such as the Gongon drums. Other traditional cultural expressions are found in the various masquerades of Nigeria, such as the Eyo masquerades, the Ekpe and Ekpo Masquerades of the Efik/Ibibio/Annang/Igbo peoples of coastal southeastern Nigeria, and the Northern Edo Masquerades. The most popular Yoruba wooden masks are the Gelede masquerades. Fermented palm products are used to make a traditional liquor, Palm Wine, as is fermented Cassava. Nigerian foods are spicy mostly in the western and southern part of the country even than Indian cuisine, but since culture is dynamic some Nigerians do not like spicy food. Some more examples of their traditional dishes are eba, pounded yam, iyan, fufu etc. with soups like okra, ogbono, egusi and so on.

Themes: Nationalist, religion, feminism, culture.

Plot summary: The Bride Price by Buchi Emechita In the city of Lagos, the Ibo Aku-nna and her brother, Nna-nndo, are bid farewell by their father Ezekiel, who says he is going to hospital for a few hours their mother, Ma Blackie, is back home in Ibuza, performing fertility rites. It becomes apparent that he is much sicker than he let his children know, and he dies three weeks later. They have the funeral the day before Ma Blackie arrives; she takes them back to Ibuza with her, as she now becomes the wife of Ezekiels brother Okonkwo. The family is problematic in Ibuza Ma Blackie has some of her own money, and so her children receive much more schooling than other children in the village, particularly the children of her new husbands other wives. Aku-nna is blossoming, though she is thin and passive, and starts to attract the attention of young men in the neighborhood, though she has not yet started to menstruate. Her stepfather Okonkwo, who has

ambitions of being made a chief, begins to anticipate a large bride price for her. Meanwhile she has begun to fall for her teacher Chike, who in turn has developed a passion for her. Chike is the descendant of slaves when colonization started, the Ibo often sent their slaves to the missionary schools so they could please the missionaries without disrupting Ibo life, and now the descendants of those slaves hold most of the privileged positions in the region. Chikes inferior background means it is unlikely that Okonkwo will agree to let him marry Aku-nna, although his family is wealthy enough to offer a generous bride price. When Aku-nna begins menstruating the sign that she is now old enough to get married she at first conceals it in order to stave off the inevitable confrontation. When she finally reveals that she has her period, young men come to court her and Okonkwo receives several offers. One night, after she finds out that she has passed her school examination (meaning she might become a teacher, earning money by means other than the bride price) she and the other young women of her age-group are practicing a dance for the upcoming Christmas celebration when men burst in and kidnap her. The family of an arrogant suitor with a limp, Okoboshi, has kidnapped her to be his bride in order to save her from the attentions of Chike. On her wedding night, she lies and tells Okoboshi that she is not a virgin and has slept with Chike; he refuses to touch her. The next day, word of her disgrace has already spread around the village when Chike rescues her and the two elope, fleeing to Ughelli where Chike has work. The two begin a happy life together, marred by her guilt over her unpaid bride price Okonkwo, furious, refuses to accept any of the increasingly generous offers made by Chikes father, and has gone so far as to divorce Ma Blackie and torture a doll made in Aku-nnas image. When Aku-nna feels sick, she goes home. There she is not sure if she will have a baby. Soon the doctor in Chikes oil company confirms that Aku-nna will have a baby. Later on when she feels sick and screams, Chike brings her to the hospital. There Aku-nna dies in childbirth. Chike christens his baby Joy.

Вам также может понравиться

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Canoy vs. OrtizДокумент2 страницыCanoy vs. OrtizYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Alcantara Vs PefiancoДокумент3 страницыAlcantara Vs PefiancoYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Metrobank Vs CAДокумент2 страницыMetrobank Vs CAYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Corporate Law MidtermsДокумент34 страницыCorporate Law MidtermsYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Banogon Vs ZernaДокумент1 страницаBanogon Vs ZernaYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Mary Ann Mattus vs. Albert VilasecaДокумент1 страницаMary Ann Mattus vs. Albert VilasecaYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Producers Bank Vs NLRCДокумент175 страницProducers Bank Vs NLRCYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Report For AdrДокумент2 страницыReport For AdrYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Baby Linda Dulay Lacar: ObjectiveДокумент2 страницыBaby Linda Dulay Lacar: ObjectiveYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Report For Adr (AutoRecovered)Документ5 страницReport For Adr (AutoRecovered)Yahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Ecological Solid Waste Management Shall Refer To The SystematicДокумент26 страницEcological Solid Waste Management Shall Refer To The SystematicYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Reps and WarrantiesДокумент6 страницReps and WarrantiesYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Like The Cranes We Fly, To World We Lie, in The Midst of This Great Danger We Strive We Ought To Know .ShsbabakkdbsbxjdjsmdnnsДокумент1 страницаLike The Cranes We Fly, To World We Lie, in The Midst of This Great Danger We Strive We Ought To Know .ShsbabakkdbsbxjdjsmdnnsYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Sales DigestДокумент3 страницыSales DigestYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Statutory Construction ReviewerДокумент8 страницStatutory Construction ReviewerYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- Alternative Dispute Resolution PDFДокумент50 страницAlternative Dispute Resolution PDFYahiko Yamato100% (3)

- Sy Santos, Del Rosario and Associates For Petitioners-Appellants. Tagalo, Gozar and Associates For Respondents-AppelleesДокумент34 страницыSy Santos, Del Rosario and Associates For Petitioners-Appellants. Tagalo, Gozar and Associates For Respondents-AppelleesYahiko YamatoОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Sexuality Disorders Lecture 2ND Sem 2020Документ24 страницыSexuality Disorders Lecture 2ND Sem 2020Moyty MoyОценок пока нет

- 10 Problems of Philosophy EssayДокумент3 страницы10 Problems of Philosophy EssayRandy MarshОценок пока нет

- NCLEX 20QUESTIONS 20safety 20and 20infection 20controlДокумент8 страницNCLEX 20QUESTIONS 20safety 20and 20infection 20controlCassey MillanОценок пока нет

- Explicit and Implicit Grammar Teaching: Prepared By: Josephine Gesim & Jennifer MarcosДокумент17 страницExplicit and Implicit Grammar Teaching: Prepared By: Josephine Gesim & Jennifer MarcosJosephine GesimОценок пока нет

- Capital Structure: Meaning and Theories Presented by Namrata Deb 1 PGDBMДокумент20 страницCapital Structure: Meaning and Theories Presented by Namrata Deb 1 PGDBMDhiraj SharmaОценок пока нет

- Reaction PaperДокумент4 страницыReaction PaperCeñidoza Ian AlbertОценок пока нет

- Notes Structs Union EnumДокумент7 страницNotes Structs Union EnumMichael WellsОценок пока нет

- Equal Protection and Public Education EssayДокумент6 страницEqual Protection and Public Education EssayAccount YanguОценок пока нет

- John Galsworthy - Quality:A Narrative EssayДокумент7 страницJohn Galsworthy - Quality:A Narrative EssayVivek DwivediОценок пока нет

- HR Recruiter Interview Question & AnswerДокумент6 страницHR Recruiter Interview Question & AnswerGurukrushna PatnaikОценок пока нет

- Apr 00Документ32 страницыApr 00nanda2006bОценок пока нет

- 3723 Modernizing HR at Microsoft BCSДокумент14 страниц3723 Modernizing HR at Microsoft BCSYaseen SaleemОценок пока нет

- Schmitt Allik 2005 ISDP Self Esteem - 000 PDFДокумент20 страницSchmitt Allik 2005 ISDP Self Esteem - 000 PDFMariana KapetanidouОценок пока нет

- scn615 Classroomgroupactionplan SarahltДокумент3 страницыscn615 Classroomgroupactionplan Sarahltapi-644817377Оценок пока нет

- You Are Loved PDFДокумент4 страницыYou Are Loved PDFAbrielle Angeli DeticioОценок пока нет

- PPH CasestudyДокумент45 страницPPH CasestudyRona Mae PangilinanОценок пока нет

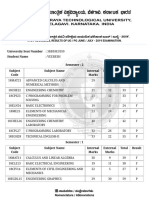

- VTU Result PDFДокумент2 страницыVTU Result PDFVaibhavОценок пока нет

- Pplied Hysics-Ii: Vayu Education of IndiaДокумент16 страницPplied Hysics-Ii: Vayu Education of Indiagharib mahmoudОценок пока нет

- Solution Manual For Management A Focus On Leaders Plus 2014 Mymanagementlab With Pearson Etext Package 2 e Annie MckeeДокумент24 страницыSolution Manual For Management A Focus On Leaders Plus 2014 Mymanagementlab With Pearson Etext Package 2 e Annie MckeeAnnGregoryDDSemcxo100% (90)

- Appendix I Leadership Questionnaire: Ior Description Questionnaire (LBDQ - Form XII 1962) - The Division IntoДокумент24 страницыAppendix I Leadership Questionnaire: Ior Description Questionnaire (LBDQ - Form XII 1962) - The Division IntoJoan GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Holland Party GameFINAL1 PDFДокумент6 страницHolland Party GameFINAL1 PDFAnonymous pHooz5aH6VОценок пока нет

- 05 The Scriptures. New Testament. Hebrew-Greek-English Color Coded Interlinear: ActsДокумент382 страницы05 The Scriptures. New Testament. Hebrew-Greek-English Color Coded Interlinear: ActsMichaelОценок пока нет

- Breathing: Joshua, Youssef, and ApolloДокумент28 страницBreathing: Joshua, Youssef, and ApolloArvinth Guna SegaranОценок пока нет

- Designing Organizational Structure-Basic and Adaptive DesignsДокумент137 страницDesigning Organizational Structure-Basic and Adaptive DesignsAngelo DestaОценок пока нет

- Rincian Kewenangan Klinis AnakДокумент6 страницRincian Kewenangan Klinis AnakUchiha ItachiОценок пока нет

- Ryan Brown: Michigan State UniversityДокумент2 страницыRyan Brown: Michigan State UniversitybrownteachesОценок пока нет

- An Equivalent Circuit of Carbon Electrode SupercapacitorsДокумент9 страницAn Equivalent Circuit of Carbon Electrode SupercapacitorsUsmanSSОценок пока нет

- Network Firewall SecurityДокумент133 страницыNetwork Firewall Securitysagar323Оценок пока нет

- Rules and IBA Suggestions On Disciplinary ProceedingsДокумент16 страницRules and IBA Suggestions On Disciplinary Proceedingshimadri_bhattacharje100% (1)

- Productflyer - 978 1 4020 5716 8Документ1 страницаProductflyer - 978 1 4020 5716 8jmendozaqОценок пока нет