Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Role of Institutional Structures at District and Sub-District Levels

Загружено:

Lokesh BangaloreОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Role of Institutional Structures at District and Sub-District Levels

Загружено:

Lokesh BangaloreАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

...

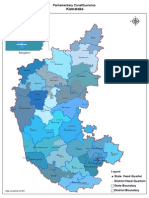

Role of Institutional Structures at District and

Sub - District Levels in Promoting School Quality

in the Context of Universalisation of Elementary

Education in Karnataka

Thesis Submitted to the

Bal1ga[ore Bal1ga[Ore

Through the Department of Education, Bangalore University

For the Award of Degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN EDUCATION

By

B.

Doctoral Fellow

Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore - 560 072 .

.

-. [.

... .

r,t .. LCr:r.: ) . .-

. , .

l

\. ,,/

_1', ..... ,.' ..

'. ,"-/ .... ,.... .;",' -..".... ..... --..

.

'. v::;...- ,,' '''0 [" .

U d th G

'd f '. . ,,(\, ",l ;." , /..... '.

n er e UI ance 0 c'-:>

Dr. M.D. Ushadevi y '<., ...

Associate Professor, Education Unit (Ii (' Ace No) 1::1 1.3

Institute for Social and Economic D"Le..J..q.-..

Nagarabhavi, Bangalore - 560 072 - _. _. _ ;<(. -' ..

BANGAdll'l ....

__

JANUARY 2004

DCLARA TlON

I hereby declare that the present Thesis entitled "Role of Institutional

Structures at District and Sub-District Levels in promoting

school Quality in the Context of universalisation of

El ementary Educati on in Karnataka" is the outcome of the original work

'lndertaken by me unde,r the guidance of Dr. M. D. Ushadevi, Associate Professor,

Education Umt, Institute for Social and Economic Change, Nagarabhavi, Bangalore-

560072. I also declare that the materials of this thesis has not formed, in anyway the

hasis for the award of any Degree, Diploma or Associate Fellowship previously of the

Bangalore University or any other Universities. Due acknowledgements have been made

wherever anything has been borrowed from other sources.

Bangalore -560072

Date: I.:I! c!btJ-'t

tu '?

;o;JriOt:J.I:J, - 560 072.

INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL

AND ECONOMIC CHANGE

Nagarabhavi, . 560 072.

3215468.3215519.3215592. GRAMS ECOSOCI BANGALORE 560040. FAX:91-080 3217008 INDIA. E-mail: admn@isec.karnle.ln

AN ALL INDIA INSTITUTE FOR INTER-DISCIPLINARY RESEARCH & TRAINING IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES

Dr. M.D. llshade\'i PhD .. ODE .. D.H.E.

Associate Protessor in Education

institute for Social and Econorrllc Change

'>:agarbhavi. Bangalore - 560072

CERTIFICA TE

I hereby certify tliat I have guided and supervised the preparation and writing of

the Thesis entitled "Role of Institutional Structures at District and Sub-District

Levels in Promoting School Quality in the Context of Universalisation of

Elementary Education in Karnataka" submitted by B Krishnegowda, who worked on

the subject at the Institute for Social and Economic Change. Nagarabhavi. Bangalore-

560072.

I also certify that the Thesis has not previously formed the basis for the award of

any Degree, DIploma or Associate Feilowship previously of the Bangalore University or

any other Uni\'ersities.

r:0i 1{'{y/--.!h v\.

(M. D. Ushadevi)

Associate Professor ..

Education Unit,

Bangalore - 560072. '

'If I,

'072 .

II

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It gives me a great pleasure to record my sincere and profound gratitude and

indebtedness to several persons and friends, who provided much needed support in

completing the thesis.

I am indeed deeply indebted and grateful to my supervisor Dr. M D Ushadevi,

Associate Professor, Education Unit, Institute for Social and Economic Change,

Bangalore. Without her guidance ap.d co-operation, my thesis would not

h,ne been possible. Her benevolent encouragement, valuable insights and endunng

.

ha\c all made this endeavor possible.

I thank the ISEC, 111 partIcular to the previous Directors Dr. P V Shenoi and Dr.

'I Go\inda Rao and the present Director Prof. Gopal K Kadekodi for providing me an

opportUnIty and facillues to carryout thIS study.

My sincere thanks are due to Prof. A S Sectharamu, Professor and Head,

Educanon Unit for hiS academIC and professional guidance. I have also benefited from

the academic interactions v.ith the laculty of ISEC Mention must be made of Dr.

Ramcsh Kanabargi. Prof. M R Narayana, Prof. R S Deshapande, Dr. K V Raju and

Dr. \, l'sha Ramkumar, whc were willing to share their wisdom and gave

,'l1couragement needed 111 this regard. Discussions with Dr. C S Nagaraju, Professor

and Head, OERPP, NCERT proved extremely useful in my research study. I am thankful

to him.

SInce the days of my Post Graduation, a person, who influenced me a lot to do

research IS Late Dr. D Shivappa. His inspiring words and academic works made me to

<,lay in research field. So it is my proud privilege to exprt'ss my deep sense of gratitude

t(l hIm.

III

I like to rccl'rd my thanks (0 Dr. M S Talwar, Chairman, Department of

Education, Bangalore University and other Staff Members for extending the support and

c?ncouragement in completing the study. I am also grateful to the Officials and Teachers

of various Institutions in Kolar and Tumkur districts for furnishing the required

I n formation.

I must thank Mr. K S Narayana for editing the thesis. I am also thankful to Mr.

'l;agaraju, Mr. Kalyanappa, Mr. Vcnkatesbappa, Mr. Rajanna, Mr. Karigowda and

other Library Staff members. I also thank Mr. Krishna Chandran and Mr. Satish

Kamat for their help in computer related problems and other Staff members of ISEC for

their timely help at each and every stage of my work.

I also thank my friends Dr. S Puttaswamaiah, !\Ir. Sitakanta Sethi, Mr.

Amitayusb Vyas, Mrs. Mini, Ms. Deepti, Ms. Geetanjali and others for their

encouragement and suppo!"! in ways in the completion of this work.

Last, but not the least. lowe a special place for my beloved parents,

parents-in-law, my wife 'Irs. Santla M S, my son Chi. Scvanth and other family

members for stimulating my inclination to study.

IV

CONTENTS

Contents

DECLARA TION

CERTIFICATE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CHAPTER-I INTRODlJCTION

1.1 Background of the Study

1.2 Need and Importance of the Study

1.3 Issues Raiseu in the Study

1.4 o,bjectives of the Study

J.5 Statement of the Problem

1.6 Scope and Limitations of the Study

1. 7 Presentation of the Study

Page No.

1

..

n

III - IV

1-20

1

17

18

18

19

20

20

CHAPTER-II REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE 21-48

2.1 Studies relating to VEE 21

2.2 Studies Relating to School Quality 27

2 3 Studies Relating to SchoollEducational

Perfomlance IEfficiency 31

2.4 Studies Relating to Educational Management /

Administration 35

2.5 An Overview of the Literature 47

CHAPTER-III METHODOLOGY 49-69

3. I Research Design 49

3.2 Sampling Design 49

3.3 Tools Used f()r Data Collection 53

3.4 Sources and Collection of Data 57

3.5 Procedure for Collection of Data 58

3.6 Operational Definitions 59

3.7 Theoretical Framework 63

3.8 Mode of Analysis

69

Contents

CHAPTER-IV

4.1

4.2

CHAPTER-Y

5. I

- !

5.3

)A

5.5

5.6

CIl'\pTER-VI

UNIVERSALISA TION OF ELEMENTARY

EDUCA TION IN KARNA TAKA, KOLAR

AND TUMKUR DISTRICTS: PROGRESS

AND PROBLEMS

Educational Progress in Kamataka-An Overview

Educational Progress in Kolar and Tumkur

Districts-An Overview

AND

OF PRIMARY DATA

'Il1e Role of District Institute of Education and

Training (DIET) at the District Level

Role of Block Resource Centers at the Block

Level

Role of Cluster Resource Centers at the Cluster

Level

Role of School Complexes at the Cluster Level

Role of Village Education Committees at the

V illaoe Level

to

Promoting School Quality

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSION

Bibliography

Appendices

Page No.

70-104

70

93

105-242

106

142

169

210

220

233

243-273

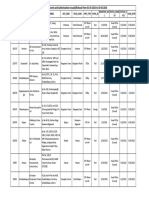

Table

No

1.1

2.1.1

3.2.1

3.2.2

4.1.1

4.1.2

4.1.3

4.1 A

4.1.5

4.16

41.7

4.1.8

421

4.2.3

LIST OF TABLES

Tilk

Development of Elementary Education in India over the Years

Number of Researches conducted in the atea of Elementary Education

over the Decades

Female Literacy Attainments across the Distncts and the Phase-wise

launching of DPEP in Kamataka

Total Number of Institutional Structures and Primary Schools in the

Sample Blocks.

Literacv Rates (%) Total, Rural and Urban areas in Kamataka, 1951-

2001

District \\;se Literacy Rates by Place of Residence and Sex, 2001

Elementary Schools in Kamataka, 1956-99

Teachers In Elementary Schools of Kamataka, 1956-99

Enrolment of Children by Sex and Level of Education in Kamataka (In

Ten Thousands)

GER of Boys and Girls 111 !he State from 1970 to 2000

TPR and STR in Elementary Schools of Kamatak, 1956-99

Dropout Rates of Children in Elementary Schools in Kamataka, 1980-81

to 1999-no

Literacy Percentages in Kolar and TlIlllkur districts

I:lclllentan Sclwols fro 111 1 ')ll() 1 ')lIl) In Kdl:irand rUlllkur

Districts

Teachers at Liementary Levels from 19(,11 tll 1')<)<) ill Kolar and TUllIkur

Districts

Page

No.

4

22

50

51

77

80

82

83

85

86

88

91

94

96

96

Table Title Page

No. No.

4.2.4 Enrolment in Lower Primary Classes (1-4) from 1960 to 2000 in Kolar 98

and Tumkur Districts

4.2.5 TPR and STR in Elementary Schools, in Kolar and Tumkur from 1970

2000 99

4.2.6 GER of Children by Sex at LPS in Kolar and Tumkur Districts [rom 1970

to 2001 101

4.2.7 Wastage Rates (%) by Sex from 1970-1998 in Kolar and Tumkur

Districts 102

4.2.8 Wastage Rates (%) ofSC Children by Scx from 1970-1996 in Kolar and

Tumkur Districts 103

4.2.9 Wastage Rates (%) of ST Children by Sex from 1970-1998 in Kolar and

Tumkur Districts 103

5.1.1 Showing the Staffing Pattern in DIETs of Kolar and Tumkur Districts 107

5 1.2 Demographic, Academic and Professional of the DIET

faculty 110

5.1.3 Showing the Categories of Experience ofthe DIET Faculty III

5 1.4 Showing the Orientation / Induction Training received by the DIET

Faculty III

5.1.5 Availability of Physical Infrastructure facility in Kolar and Tumkur DIET 112

5.1.6 AvailabiIity ancl Worki:1g Ctmdition of the Academic Equipment in the

Sample DIETs i 13

51 7 Overall Capacitv (If III tenm of Human Resource and Academic

1.qlllplllclll 115

51 8 Number of'lraining I\ctlvitics conducted ill h:.olar and Tumkur

DIETs 116

Table

No.

Title

5.1.9 Number or Rranch wise Training Activities or DIETs tn Kolar and

Tumkur districts

5.1. 10 Proposed and Achieved Training Program at DIETs in Kolar and

Tumkur districts during 1998-99

5.1.11 Showing the Extent of Coverage of Teachers under In-service Training

activities in the Sample DIETs from 1996-97 to 1998-99

5.1.12 Activities conducted under different Themes in the Sample DIETs

5. I. 13 Activities conducted for different Clientele groups in the Sample DIETs

5.1.14 Duration of Activities .:onducted in the Sample DIETs

5.1.15 Standard wise and subject wise number of lessons delivered by Pre-

Service Trainees in Kolar DIET

5.1.16 Standard wise and subject wise number of lessons delivered by Pre-

Service Tratnees in Tumkur DIET

5.1.17 Showing the Priority of Goals and Objectives as Perceived by the DIET

Faculty

5.I.1S Showing the Perceptions of the Faculty regarding the Level of

achievement of Goals and Objectives by the DIET

5.1.19 Co-operation with in the DIET as Rated by RPs

5.1.20 Opportunities for ProfessIOnal Development of DIET Faculty

5 1.21 Categories or Problems as Cited by the DIET faculty

5.2.1 Shov.;ng the Staffing Pattern in RRCs of Kolar and Gowribidanur

:; 2.2 hJucational ()ualifications orRPs

.5 :: :; Distribution or RPs by Age

I

Page

No.

liS

1 J 9

120

121

121

122

126

126

136

137

138

140

140

143

144

4 ~

Table

Title

Page

No.

No.

5.2.4 Distribution ofRPs by Scx

145

5.2.5 Place of Residence of RPs from BRCs

145

5.2.6

Showing the Length of Service of RPs

145

5.2.7 Experience of BRC RPs in Primary Schools

146

5.2.8 Showing the Details of Training Undergone by the RPs at BRCs

147

5.2.9 Physical Infrastructure facility in BRCs

149

5.2.10 Availability of Academic Equipments at BRCs

150

5.2.11 Number of Training Activities conducted in Kolar and Gowribidanur

BRCs 153

5.2.12 Details of Training Programs / Activities undertaken by the BRCs at

Kolar and Go"vribidanur from 1995-96 to 1998-99. 154

5.2.13 Number of Batches and Duration of Training Programs conducted in the

Sample BRCs 156

52.14 Number of Teachers covered under various Training programs of BRCs 157

5.2.15 Perceptions of Beneficiaries about the training programs at BRCs 158

5.2.16 RPs' Ratings of the Training Methods 159

5.2.17 Numher of School Visits by BRC Personnel for the year 1999-2000

161

5 2 18 Workload as Rated bv RPs

167

:; 2 It) Natun: of II ()rk re!.:\ant to the (,oals of nRC ~ Reportcd by RPs

1M,

53.1 Numbcr ofl'RCs, Schools [lnti TC[lchers in Kolar District

169

532 Numkr oi Schools and Teachers Per CO in the Sample CRCs

171

Table Title Page

No. No.

53.3 Educational Qualifications of COs. 172

534 Showi ng the Total Years Experience 1)1' COs. 172

53.5 Distribution of Coordinators by Age 173

53.6 Distribution of COs by Sex 173

53.7 Distribution ofCRCs by Physical facilities and Equipments 174

53.8

Classification of the Duties and Functions of COs

176

5.39

Perfonnance of Different Functions in Sample CRCs

177

53.10

Number of Meetings held at Sample CRCs

192

5.3.11

Frequencies of Activities Undertaken in the Meetings at CRCs

194

5.3.12

Perceptions of Beneficiaries about the Monthly Meetings at CRCs

198

53.13 Number of Days Proposed for Different Activities by the COs 201

53.14

A Comparative Analysis of the Average Number of days Proposed and 202

Spent for Different Activities by the COs

203

53.15

Different kmds of Tasks of COs

53.16

Number of School Visits by different Funclionaries for the year 99-00 205

54.1

Performance of Different Functions ia Sample SCxes 212

542

Number of Monthly Meetings held at Sam pie SCxes 214

543

Fr..:qu..:ncles of Activiti..:s Undertaken in the Meetings at SCxes 216

544

I\;lllnher of Schools and Teachers per lIead ( '999) in the Sample SCxes

219

Table Title Page

No. No.

5.5. I Number of Monthly Meetings held at SamplL; VECs 221

5.5.2 Average Percentages of Attendance of VEC members during Monthly

Meetings held at Sample VECs 222

5.5.3 Issues discussed in the Meetings at Sample VECs 225

5.5.4 Gender and Caste composition of VEC members in the Sample VECs 226

5.5.5 Training Status of VEC Members 227

5S6 Structure and composition of VECs and SDMCs 228

5.5.7 Roles and Functions of VECs and SDMCs 230

5.5.8 Powers of VECs and SDMCs 231

5.6.1 Academic Atmosphere in the Sample Schools 236

5.6.2 Percentage of Dropout Children in Sample Primary Schools 238

5.6.3 Classroom Curricular Process in DPEP and Non-DPEP Districts

239

5.6.4 Mean Percentage Scores of Children in Achievement Tests in Different

Subjects at the Sample Schools in Kolar and Tumkur Districts

241

LIST OF CHARTS/DIAGRAMS AND GRAPHS

Figure Title Page

No. No.

3.2.1 Distibution of Number of Sample Units selected for the Study 53

4.1 Administrative Setup (Primary and Secondary Education) in Kamataka

State 75

4.1.1 Showing the Literacy Percentages of the State 78

4.1.2 Rural Urban Literacy Percentages in Kamataka 78

4.1.3 Rural Urban Literacy Percentages by Sex 79

4.1.4 Grovv'th of Elementary Schools 82

4.1.5 Percentage Increase of Teachers in Elementary Schools 84

4.1.6 Enrolment of Children by Sex and Level of Education 86

4.1.7 Teacher - Pupil Ratio in Elementary Schools of Kamataka 88

4.1. 8 Standard -Teacher Ratio in Elementary Schools of Kamataka 89

4.2.1 Male-Female Literacy Gap in Kolar and Tumkur Districts 95

4.2.2 Percentage increase of Teachers in Elementary Schools of Kolar and

Tumkur Districts 97

4.2.3 Enrolment Gap Between Boys and Grils in Kolar and Tumkur Districts 98

42.4 TPR in Elementary Schools of Kolar and lumkur Districts 99

4.2.5 STR in Elementarv Schools cf Kolar and Tumkur Districts 100

5.2. I Structural Linkages of I:3RCs with District and Sub-cbstrict level 166

Organizations

8EO

BIC

BRC

CO

CPI

CRC

DDPI:

DIC

DIET

DPH

DPO

HM

HPS

lOS

ISEC

LPS

i>1LL

NFE

NPE

OBS:

RP

SC

sex:

SDMC

SSA

ST

STR:

TPR

UEE:

VEC

ZP:

ABBREVIATIONS

Block Educational Ofliccr

Block Implementation Committee

Resource

Coordinator

Cor.lInissioner of Public Instructiun

Cluster Resource Center

Deputy of Public Instruction

District Irr.plcmentation Committee

Institute of Education and Training

District Primary Education Programme

District Project Office

Head Master / Mistress

Higher Primary School

Inspector of Schools

Institute for Social and Economic Change

Lower Primary School

Minimum Levels of Learning

Non-Formal Education

National Policy on Education

Operation Black Board

Resource Person

Scheduled Caste

School Complex

School Development and Monitoring Committee

Sarva Shikshana Abhiyana

Scheduled Tribe

Standard Teacher Ratio

Teacher Pupil Ratio

Universalisation of Elementary Education

Village Education Committee

Zilla ParishadIPanchayat

CHAPTER -I

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background of the Study

The importance of primary education in a developing country like India needs no

special mention. While the benefits of primary education are assumed to have

facilitated easy take ofT for rapid economic h'Towth in East Asian countries, the low

IlleraC\ and low average educational attainments in the Indian sub-continent have

matters of great concern for hastenmg and sustaining economic growth. At the

time when India is making attempts to move rapidly towards market economy through

Its liberalised economic policies, realising the goal of universal primary education

assumes crucial sigmficance for both economic progress and social equity.

Research c\IJences over the \'cars have demonstrated the significant posillve

dlcd 01 prnnar) ducatlon on the economic gro .... th rates (Peaslee, 1965, 1969,

Benavot, 1985; World Rank, 1987b, 1993; Lau, Jamison and Louat, 1991; Harro, 1991;

1993, Nehru and Dhareshwar, 1994; Oath and Ravallion, 1995); earlllngs (Me

r-..lahon, 1984; Psacharopoulos. 1985, Rayoo, 1988); productivity m general, fann

prllductl\lty in particular (Chaudn, 1979, Lockheed, Jamison and Lau, 1980;

1990; Foster and Rosenzweig, 1995, 1996); Social development in which

reduced fertility (Holslllger and Kasardu., 1975; Cochrane, 1979, 1986; Haverman and

Wolfe, 1984; Basu, 1992; India, MHRD, 1993a) and improved child health and

nutntlOn (Sen and Sengupta, 1983; Cochrane, 1986; Dasgupta, 1990; Walker, 1991);

atlitudinal modernity (Armer and Youtz, 1971; Inkeles and Smith, 1974; Holsinger and

Theisen, 1977) Further, it 15 also found to improve income distributIOn, increase

savlllgs and more rational consumption, enhance the status of women and

promote adaptability to technological change (World Bank, 1990). The contributions

of primary education are also seen in terms of certain benefits accrued to individuals

and society In terms of forging national unity and social cohesion by teaching common

mores, Ideologies and languages.

In India, provision of free and compulsory education to all children until they

c.omplete the age offourteen is a directive principle ofthe constitution. While adopting

the Constitution in 1950, the goal was to provide free and compulsory education to all

children up to the age of fourteen, within the next 10 years. However, the target time

to achieve the goal of Universalisation of Elementary Education (UEE) had to be

revised keepmg in view the educational facilities available at that time, since the goal

was too ambitious to be achieved within that short period of time. During the period

1960-65, no official pronouncements were made regarding the UEE for the children in

age group 6-14. However in 1965-66, the target time was revised to 1975-76. The

working group set up by the policy commission then revised the target to be achieved

b\ the end of Sixth Plan (1984) The Kathan Commission (1966) had suggested that

the same should be achieved latest by 1986.

The World Conference on Education for All (EPA, 1990) held at Jomtein

adopted a declaration calling upon all member countries and agencies to strive for

achle,mg EF A by the year AD 200 I. The meeting of the Consultative Committee

(1992) emphasised that the targets of UEE should no longer be given in terms of

additional enrolment alone and no longer be set for the country as a whole, but all

children irrespective of caste, creed, religion and sex etc. up to the age of 14 years

should be given free education. At the World Education Forum in Dakar in 2000, all

countries resolved to translate the six 'Education For All' goals into a reality by 2015.

These Goals are. (I) ProVision of early child care and education, especially for the

most vulnerable and the disadvantaged: (2) Ensuring all children, particularly girls and

those in difficult circumstances, access to free and compulsory primary education; (3)

Ensuring learning needs met of all young people and adults through equitable access to

learning and life skills; (4) Achieving a 50% improvement in levels of adult literacy,

eSpi:clally for women and equitable access to basic and continuing education for adults;

I ~ f'1Jmlnating gender disparities In education and (6) Improving quality of education

to ensure excellence and achieve measurable learning outcomes in literacy, numeracy

and life skills The two Millenium Goals adopted at the UN General Assembly (6-9-

200 I) also emphasised the need and importance of universalisation of primary

education and promotion of gender parity. Even the 93,d Constitutional amendment

2

makes it mandatory to enroll all the out-of school-aged children for elementary

education; imtlate steps to retain them in school till the completion of elementary

education and ensure mInllTIUm levels of learning. In line with the recommendations

emanating from these reports, India has been making several efforts to achieve the goal

ofEFA.

The National Policy on Education (NPE 1986, 1992) envisaged that all children

who would attain the age of about II years by 1990 would have had five years of

schoollng or I equivalent through the non-formal stream, and that by 1995 all children

will be provided free and compulsory education up to the age of 14 years. Then the

focus shifted from mere quantitative expansion of educational facilities to universal

enrolment and universal retention up to the prescribed age group (6-14 years), with a

substantial iml'rovement In the quality of primary education.

Detennmed efforts towards realising the goal of Universalisation of Elementary

Educatlon (UI E), have received fresh Impetus after the formulation of the National

Polley on Education (NPE, 1986, 1992) Most of the interventions are centrally

sponsored and are aimed at bnngmg about qualitative improvement III primary

educatIOn Correspondingly a Pr06Tfamme of Action (1987, 1992) has also been

noh'ed whlel, Jescnbc, the IInrlementation strate6'} for several of the innovations and

major polley fc'commendatlOns

The urxJated NPE (1992) has given an overriding priority for bringing about

quaiJtatJve iml'rovement In primary education while realising the quantitative targets in

the face of low levels of learning and high dropout rates prevailing In many rural

It caf'le notfced from the table 1.1, that over the years, there has been a steady

progress III thc development of elementary education in India since 1950-51. There

has been a phenomenal increase in the number and spread of institutions as well as

Gross Enrolment Ratios (GER) and number of teachers. The number of Lower

Pnmary Scho( ,;<; (LPSs) has Increased from 2.1 lakh in 1950-51 to 6.3 lakh in 1999-00.

The number 01 Higher Pnmary Schools (HPS) has Illcreased from 0.14 lakh In 1950-51

to I. 9 lakh in 1999-00. The GER of 6-11 age group has gone up to 92. I percent in

J

i

i

I

1999-00 as cllmpared to 43.1 percent in 1950-51. Conversely, the dropout rate has

been reduced fTom 66.34 percent in 1960-61 to 42.65 percent in 1999-2000 at LPS

stage. Although, the dropout rate at HPS reveals a decreasing trend from 1980-81, still

it is as high as 57 percent during the year 1999-00. Similarly, the Teacher - Pupil

Ratio (TPR) over the years has increased at both the levels, although in 99-2000, it was

well within the prescribed norm.

Table 1.1: De\elopment of Elementary Education in India over the Years

Particulars 1950-51 1960-61 1970-71 1980-81 1990-91 1999-00

Primary

I

LPS

,

2.09 3.30 4.08 4.95 5.58 6.3

Schools

I

HPS 0.14 0.5 0.91 '

1.19 1.47 1.9 I

(In Lakhs)

,

i

Total 2.23 3.8 4.99 6.14 7.05 8.2

Teachers

I

LPS 0.54 0.74 1.06 1.36 1.64 1.90

r

(In Millions)

f

HPS 0.09 0.35 0.64 0.85 1.06 1.28

Total 0.63 109 17 2.21 2.7 3.18

,

G 6-11 Boys 60.6 82.6 92.6 95.8 113.9 100.9

.

E Girls 24.8 41.4 59.1 64.1 85.5 82.8

R

Total 43.1 62.4 76.4 80.5 100.1 92.1

11-14 BoYS 20.6 33.2

,

46.5 54.3 76.6 65.3

Girls 4.60 11.3 20.8 28.6 47.0 49.1

Total 12.9 22.5 34.2 41.9 62.1 57.6

Teacher Pupil [ -IV I 24 36 39 38 43 42

RaM (TPR) VI-Vlll 20 31 32 33 37 37

D I I-IV Boys INA 61.74

i

64.48 56.2 40.10 40.63

I

R

I

(LPS) Gtrls INA 70.9l 70.92 62.5 45.97 44.66

0

Total INA 66.34 67.7 59.35 43.04 42.65

P

VI-VIII Boys INA 18.77 22.78 68.00 59.12 54.00

0

(HPS) Girls INA 25.57 27.31 79.40 65.13 60.09

U

f

Total INA 22.17 25.05 73.7 62.13 57.05

T

Source: MHRD, Department of Education, GO!, New Delhi

Central Statistical Organisation, Ministry of Statistics WId Programme

Implementation, GO\, New Delhi, 1999

Note Total ,jropout during a course stage has been taken as percent of intake in the first

year 01 the course stage, I N A - Information Not Available

Thus, the above trends indicate that UEE in terms of provision of schooling

facilities, teachc:rs, emolment of children and reduction in dropout rate at I-V stage has

made positive progress. However, the persisting dropout at the higher primary stage,

particularly of ~ i r l s is a cause for concern. This evidently suggests that the quality of

schooling nee..j, to be enhanced for improving the retention capacity of the schools. It

4

is mime mth this thlnkmg, several centrally sponsored mterventlOns have tx--en

launched Some of the saltent interventions m this direction are described hereunder.

1.1.1 Operation Black Board (OBB, 1987)

Considering the poor infrastructure facilities that prevail In primary schools, the

NPE has given due recognition for improving basic facilities in primary schools as a

first step towards school quality improvement A phased drive symbolically called

Operation Black Board (OBB) was started in 1987-88 by the Union with a view to

reduce impediments and for increasing quality of primary education. The Scheme

had the follOWing objectives:

(i) To provide for at least two classrooms suitable for all weathers and facility

of lavatory for boys and girls.

(il) To pwvide for at least two teachers in every school out of them one should

be a lady so far possible.

(iii) To provide for necessary teaching material with blackboard, maps, charts,

toys and instruments of working experiences.

In ordc:r to make the Revised Policy and Programme Of Action (POA, 1992)

aC!I\e under the OperatIOn Black Board dunng the 8

th

plan, the following three sub

schemes were Included.

(i) The Operation Black Board included under the 7

th

plan to be kept continued

for including the rest of the schools in the above plan.

(il) To make available three tcachers and classrooms in the pnmary schools

where the enrolment is above 100.

(iii) To extend the area of the OBB in the upper primary schools.

1.1.2 District Institutes of Education and Training (DIETs)

Building capacities of schools and teachers assumes larger significance In the

context of efkcttve changes In the qualitative aspects of the elementary education

system. Teachers are the key resource persons in bringing desirable innovations into

the classrooms and making education effective and useful, they have to be trained

5

and oriented In the modem concepts of school organisation, new methods of

teaching, preparation and use of audiovisual aids, trying out action research studies,

carrying out experiments and maintaining better school community relations. The

education and training received before entering into a profession is only a beginning

which may bt' regarded as a foundatIOn course and hence there arises a necessity of

enriching, adding, revIsing and modifying continuously in the light of existing

knowledge Keeping thiS In view, the NatIOnal Policy on Education perceives

teacher education as a continuous process and its pre-service and in-service

components being inseparable have been incorporated in the new restructured

programme of teacher education initiated in 1987. In this direction, the emergence

of District Institute of Education and Training (DIET) is an important milestone.

These DIETs are expected to provide academic and resource support to elementary

education and also to engage in actIOn research and innovation. Thus, DIETs have

come to pia) a key role in the comprehensive educational development of the

district keeping in the background the district specific educational needs and social,

economic and geographical characteristics. It is important to note that prior to

DIETs the in-service and pedagogic training for teachers were undertaken by the

"pex State academic body namely the SCERT. The DIETs have been set up in all

the earlier 20 districts of Kamataka under the second phase m 1993.

1.1.3 School Complexes (SCxes)

The idea of Improvmg the school educatIOn by using school complexes was first

mooted by the EducatIOn CommiSSIOn ( 1964-66). The basic purpose of the complex

\vas to Improve the quality In primary education by integrating the neighbouring

primary schools to a nuclear secondary school, so that the schools of a geographical

area may function as a whole. It was lUlder the assumption that this would further

help in drawing on each other's resources and diffusion of new ideas and practices

ror the development of primary schools with minimum external control and support.

In fact, the idea of SCxes originated as early as 1967 as an experimental

project In Rajasthan following the recommendations of the Education Commission

( 1964-66). Although attempts were made to implement this concept in Punjab and

6

Maharashtra during 1970s, the scheme did not take off in the right spirit for various

Later in 1990, the Review Committee under the chairmanship of Acharya

Ramamurthy also recommended the concept of educational complex for increasing

the professional skills among teachers. However, with the NPE (1986)

reemphasizing the key role played by the SCx, the SCx has come to occupy an

important position in the qualitative improvement of school education.

Following the recommendations of the NPE (1986) and Programme Of Action

(1992) to provide academic support to primary schools and teachers, school complexes

have been established by the Government of Kamataka (GOK) as in the other States at

the cluster level. The school complexes are generally located in High Schools and are

called the lead schools which use the material and human support available in them and

surrounding schools to provide academic guidance and direction to the primary school

teachers under them. At the cluster level, School Complexes (Sexes) have been set

up for short training programmes like seminar and experience sharing workshops.

Fo\lO\ving are the roles and functions of School Complexes.

I. To organise monthly meetings of all teachers working within the SCx and

arrange model lessons by expert teachers,

2. To identify difficult topics in different subjects and find out the solution for the

same.

3. To develop and exhibitions of low cost - no cost teaching aids,

4. To organise competitions for teachers, working within the SCx,

5 To undertake follow up work

1.1.4 Minimum Levels of Learning (MLL)

In order to enforce minimum learning level for bringing about improvement in the

reccptability of students in schools as well as enhancing accountability of teachers, a

curricular guideline has been prepared under the nomenclatue Minimum Levels of

Learning (MLL). The main strategy is to improve learning acquisition in school,

7

l

focuses on what is happening in the classroom and seeks to bnng the pnnclples of

equity, quality and relevance to bear upon it. The stmtegy aims at laying down

learning outcomes expected from basic education at a realistic relevant and

,

functional level, prescribes the adoption of measures that would ensure all children,

who complete a stage of schooling, achieve these outcomes. These outcomes define

the Minimum Levels of Learning common to both schools and equivalent Non

Formal Education (NFE) programme Following are the major Steps involved in thl.:

Introduction of Minimum Levels of Learning

I. Assessing the existing level of learning achievement

2. A definition of the MLL for the area and the time frame within which it will be

achieved.

3. of the training practices to competency based teaching.

4. Introducing the continuous comprehensive evaluation of student learning.

5. Reviewing the textbooks and revision (if required) and

6. Provision of inputs as necessary including provision of physical facilities,

teaching-training, supervision and evaluation etc., to improve the learning

acquisition to the MLL.

For improving this programme, the union government provides cent percent

aid. In order to enrich the learning atmosphere in the class, the teachers have been

provided with handbooks on the three subjects namely language, mathematics and

environmental science. Work books and evaluation materials have been prepared

for the students. State Council for Education, Research and Training (SeERT) and

District Institutes of Education and Training (DIETs) have been included in the

programme by imparting essential training to the members of educational

institutions in the ,elected districts of Kamataka.

Almost all the Commissions and Policies havc given due impor:ance to the

role of teachers ip bringing desirable innovations in the classrooms. Unless they

themselves are not equipped adequately they cannot transact successfully in the

classrooms and hence the in-service teacher training has been the overriding priority

by the DPEP in the form of establishing new institutional structures at sub-district

8

levels in addition to already existing DIETs at the district level for the purpose of

making in-service training rigorous and adequate. The details with regard to these

institutional structures are presented in the forthcoming paragraphs.

1.1.5 Block Resource Centres (BRCs)

At the block level, BRCs have been set up for the purpose of making the in-service

training more rigorous and adequate in terms of coverage of teachers and

frequencies of training. These BRCs have their own building. The BRCs have also

been prO\ided \\ith the equipment like TV, VCR, OHP, furniture, telephone,

jamkhanllS, mattresses, science and mathematics kits, almirahs, water drums,

duplicating machines, Xerox machines etc., in required quantities

These ARCs han: been functioning in the OPEP district from 1995-96. The roles

and functions e.\:pected of these resource centres are as follows

I. To conduct In-service training and other related programmes.

2. To undertake school visits in order to help the teachers to upgrade their teaching

competencies by being a friend, philosopher and guide to increase their

contidence and supervision of CRCs,

3. To provide information on the availability and use of teacher guides in schools

to the relevant authorities and

4. To assist in designing pupil evaluation programmes.

1.1.6 Cluster Resource Centres (CRCs)

A group of 20-25 schools with a definite geographical area were made a cluster for

the purpose of better organisation and management and to enable better utilisation of

the resources of both the State and the community. Each cluster is a full-fledged

unit haVing a co-ordinator (CO) of its own with some delegated powers to

administer the unit Provision fur sharing of experiences for these COs has also

been made. These CRCs have their own buildir.g and have been functioning from

J 997-98 and are encouraged more towards greater self-reliance so that they might

shoulder heavier responsibilities I n addition, they have also been vested with

h'T'eater authurity ;n the management of activities at the cluster level. The major

roles and functions of these eRes can be summarised in the following points.

9

I. To identity the villages with schools and without schools in a CRC limit

,

") To prepare a list of schools, Anganwadi Centres and teachers etc,

3. To prepare the map ofCRC,

4. To collect statistics on schools, children and teachers,

5. To conduct monthly meetings to provide educational information,

6. To help teach..!rs for the development of teaching aids and in solving educational

problems,

7. To supervise NFE centers,

8. To help the children for medical check-up,

9. To undertake the works assigned whenever by the Department of Education,

10. To visit each school in a CRC limit at least once in a month and to give the

required guidance for the teachers about the educational progress and use of

teaching aids in the regular classroom teaching-learning process,

11. To assist in VEC meetings,

12. To organise and maintain programmes like (a)VEC mela, (b) Maa-Beti

conventions, (c) Chinnara mela and (d) micro planning etc,

13. To cooperate with BRCs in organising training programmes by providing the

required information,

14. To assist in the (a) educational tours, (b) sports and (c) cultural activities

conducted in the schools under CRC limit,

15 To distribute (a) text books, (b) furniture, (c) teaching aids and such other

materials provided by the department to schools,

16. To maintain all the records and registers relating to CRC,

17. To maintain the finance ofCRC as per the order of the Department and

18. To prepare the annual works plans and adhere to the same.

1.1.7 Village Education Committees (VECs)

It ,viII defimtely be a dream to achieve success in the universalisation of elementary

education unless and until the parents and guardians of children are made aware of

the necessary social consciousness and enlightenment and to realise the importance

of education, particularly the primary education for all irrespective of sex, caste,

]0

creed. economic status and religion etc. Hence in order to create adequate

awareness and interest in the de'ielopment of primary education Village Education

Committees (VECs) have been created to look after the primary education as a

whole.

Concept of VEC

T"e National Policy on Education (NPE, 1986) and Programme of Action (POA,

1986) further reiterated in 1992 approved by an executive committee popularly

known as CABE (Central Advisory Board on Education) attaches considerable

importance to Village Education Committees (VECs), which would be responsible

for faCIlitating the task of universalisation of elementary education. The maior

.I

responsiblhty or the committee is the operationalisation of micro planmng and

school mapping III the village through systematic house to house survey and periodic

discussion with the parents. It is the endeavour of the committee that every chi Id in

e\ery family participates l!l primary education. The 73

rd

and 74

th

amendments to the

ConstitutIOn of India accorded a further boost to these committees.

In the State of Kamataka, VECs have been constituted OUTing 1995

following the orders of the State government vide its order No. ED 162 NCO 94

date, 1-8-95. It is to be noted that very recently the VECs and SBCs have been

replaced by the School Development and Monitoring Committee5 (SDMCs) in the

State of Karnataka following the recommendations of the Task Force Committee on

educatIOn under the Chairmanship of Dr, Rajaramanna in 2001 vide its order No. ED

I, PBS 200 I. Bangalore, date 28-4-200 I.

Roles and Functions of E ~

The roles and functions of VECs are generally the following.

Supervision o\er Adult Education (AE), Early ChildCare and Education (ECCE),

Non Formal Education (NFE) and Primary Education

Supervision over composite Upper Primary schools under delegation of authority

from Panchayit Samiti.

1 I

Generation and sustenance of awareness among village community by ensuring

participation of all segments of population.

Promote enrolment drives in IJrimary schools and persuade parents of non-attending

chIldren to sepd their wards to schools.

Reduce dropouts in primary schools by initiating measures and services for

retention.

Assist in smooth functioning of primary schools.

Seek support of teachers, youth, women and others for educational and other linked

health and wei fair programmes.

Mobilise resources and help schools to have water supply, urinals, playgrounds and

other facIl ities.

Prepare plans and proposals within their resources for development of education in

the village and to attaintotal adult literacy and universal primary education.

Present reports and proposals to Panchayat Samities and make periodic self-

assessment of progress of committees' efforts.

Co-ordinatIon with other social service departments and committees ft1r mutual

support.

Powers

To \1511 educational institutions.

To check attendance and other registers to enquire and report to concerned

authorities on educatIOnal deficiencies and requirements in the village.

To recommend annual budget of school to concerned authority.

To undertake construction and repair works entrusted to them.

To report on regularity of students, teachers' attendance and school functioning.

To frame the school calendar under the guidance of Zilla Parishad.

12

1.1.8 District Primary Education Programme (DPEP)

Follo\\ing the recommendations of the NPE (1986) and Programme of Action (1992),

a new called District Primary Education Programme (DPEP) a need

based primary education programme was started with an objective of making

primary education universaL It is a centrally sponsored programme with the

assistance of the World Bank. In this programme the development of primary

education has been considered as wholeness and its objective is to implement policy

of VEE through planning and fixation of separate targets according to particular

district. Following are some of the unique features of this programme.

Goals of OPEP

To reduce the ditTerences in emolment, dropout and the learning achievement

among the gcnder a:Jd social groups to than 5'>;(,.

To reduce the overall primary dropout rates for all students to less than 10%

To raise the a\erage achievement levels by at least 25% over measJred baseline

levels and ensure achievement of basic literacy and numeracy competencies and

a minimum of 40%. achievement levels in other areas.

To provide according to national norms access for all children to primary (1 to 4)

classes or Its equl\alent throut;h non-fonnal stream.

Special Features of DPEP

.:. Permeating cthos of cost-cffectivcness and accountability into every part of the

education system,

.:. Stressing partiCipative process \vhcreby the local community plays an active role

in VEE,

.:. Dc\clopment of an effective NFE system which can meet the diverse

educatIOnal needs of the children to whom the school would not reach,

.:. Strengthenmg State capacities m the area of educational planning and

managcment,

.:. Facilitating access for disadvantaged groups such as girls, socially backward

eommumtles and the handicapped,

.:. Recurrent and regular upgrading of teachers' skills,

13

.:. Involvement of communities in programme planning,

.:. Strategies for convergence with related services such as health care, Early

Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) and other government welfare schemes,

.:. Improvement of Infrastructure facilities,

.:. Effective Decentralised school management and

.:. Achievement of MLL.

Strategies and approaches under DPEP:

To open new schools in the villages which do not have schooling facility,

construction of school buildings. and appointment of teachers,

To provide an additional room and renovation of buildings in larger scale,

Provision for drinking water facility, toilet etc., wherever possible preferentially

To provide the teaching-learning materials to all schools,

To supply textbooks cum work books and teachers' support materials,

Establishment of VECs and mother-teacher associations and training,

Strengthening of DIETs, and SCERT,

To establish BRCs and CRCs and continuous training of teachers,

Computerisation of educational information at district and State level and

Training of educational administrators and supervising officers.

In the beginnIng, this programme was launched in the four of

Karnataka, namely Belgaum, Kolar, Mandya and Raichur. In the second phase it

was Implemented in 7 distncts namely Bangalore Rural, Bijapur, Bellary, Bidar,

Mysore, Gulbarga and Dharwar. The DPEP has been drawn in each district with

wide ranging discussIOns with the community, peoples' representatives,

non-go\ernmental organisations and research institutions including apex bodies in

education The basis for the selection of the district was educational backwardness

of distncts with female literacy below the national average and districts where Total

Literacy Campaigns have already been successful leading to enhance demand for

elementary education.

14

An attempt has been made here to p r ~ n t some of the important ongoing

prob'Tammes under the OPEP for the purpose of improving the quality of primary

education. These programmes are broadly classified under different components of

UEE namely access, retention and quality improvement.

Access

[n order to enhance access to children, new schools have been opened in the

unreached areas of the district in order to cater to the needs of the deprived sections

of the socIety such as girls, SCs/STs. Some primary schools also have been

exclusively opened for catering to the needs of girls. The other facilities provided in

this direction are appointment of teachers, construction of school buildings,

provision of equipment, furniture, science and mathematics kit, teaching-learning

and play materials to new schools. The teaching learning materials provided include

maps, charts, models of human body, materials to develop skills in the subjects of

language, mathematics and environmental science and the play materials include

puzzles, balls, skipping ropes and rings etc. Some lower primary schools to class

fifth have also been upgraded and provided an additional teacher for the same. An

attempt also has been made to start some NFE centres as an alternative schooling

facility in places where there are a large number of children, who are un-enrolled or

dropped out of schools and appointment of Village Teacher Motivators to promote

girls education in the places where the school is in the danger of becoming

dysfunctional because of difficulties in posting adequate teachers to the schoel and

where the teacher student ratio is extremely adverse.

Retention

The actIvities like KalaJatha, Chinnara mela and Maa-beti conventions, have been

taken up mainly for the purpose of creating awareness in the minds of the parents by

disseminating the message of the importance of girls' education, equality of women

and abolition of chIld labour etc. Cassettes containing the songs of children have

been produced and distributed to all the primary schools in the district especially for

sustaining interest among children in the classroom. In order to attract the children

15

to schools and create interest in their minds, provision has been made to conduct

sports. cultural competitions and study tours.

Health Cards

The health cards for the children of first standard to fourth have been provided in

order to facilitate the health check up programme for these children to be carried out

by the health department of the State government.

Strengthening of Anganwadi Centres

Some of the existing Anganwadl Centres have been strengthened for the purpose of

improVIng the attendance of girl chIldren in the afternoon sessions in primary

schools and to prepare the children to attend the schools.

Teachers Grant

D\l1amic methods of teaching. use of inexpensive and appropriate audio-visual

materials would generally make primary education effective and appealing to

children KeepIng thiS POInt in view, a teacher grant of 500 rupees has been provided

to each teacher per year to purchase some materials like card boards, colour papers,

paints. skdch pens, thermocol sheets, gum and thread etc, for the preparation of

teaching-learning materIals and to use them in the class room teaching-learning

prvcesses

Scboollmpro\ement Fund

A school IInprO\ ement fund of :WOO rupees per year has been released to each VEC

in the d i s t ~ l t for the purpose of making the schools attractive. The fund can be used

as per the decisions of the VEC for different items like minor repair if allY and white

wash to the building, repair of the furniture, purchase of teaching-learning/play

materials and cupboards etc. In addition, provision for water, sanitation and other

repair works have also been made in order to make the schools attractive.

16

1.2 and Importance ofthe Study

Despite several interventions to improve elementary education across the States in

India. poor attendance in schools, large number of dropouts and poor learning

attainments continue to pose challenges to the education system. The recent baseline

surveys in different parts of the country have reiterated these aspects. Even in the State

of Kama taka, similar trends are observed.

Considering the literacy levels in the State of Kamataka, where the present

study is located. it is observed that the State has experienced increase in literacy levels

from 1991 to 2001(67 % in 1991 to 760,'0 in 2001 for male and 44 % in 1991 to 58 %

in 2001 for female) However, the phenomenon of out of school children, poor

attendance and 10\\ Ieaming Ieveb continue to pose serious problems, especially in

backward regions as well as with to female population

The Oistflct Prob'Tamme of Primary Education Project has been launched

during 1995 to hasten the process of realising the goal of universal primary education

in the State of Kamataka. Initially four districts portraying low female iiteracy levels

have been covered under OPEP phase-I and subsequently seven more districts in phase

II To support the OPEP project, the resource centres namely, the BRCs at the block

bel. the CRCs at the cluster level and VECs at the village level have been formally

established during 1996-1997. The DIETs, which came into being in 1993, are

expt..'Cted to provide academic leadership to the newly started sub-district level

institutions.

NOl\\ithstanding the above developments, poor quality of primary education,

10\\ le\ el of attendance and leaming attainments and persisting phenomenon of out of

school children in the backward regIOns have been serious causes of concern Under

these circumstances, the following research questions asswne vital significance in the

context of the study.

17

1.3 Issues Raised in the Study

To what extent UEE in Kamataka has been successful in terms of enhancing

participation and retention of children in primary schools over the years?

What has been the impact of a major intervention like DPEP in hastening the

goal ofUEE in Kamataka?

To what ex1ent the newly created institutions have been able to contribute to

quality improvement in primary education in terms of enhancing capacities of

schools and teachers?

\\c11ether the newly created institutional structures like the DIET BRC CRC

, , ,

SCxes and VECs at district and sub-district levels have adequate facilities and

CJpacltles to perfonn their expected roles of providing technical and academic

support to primary education'?

\,'hat are the major bottlenecks, which come in the way of effective functioning

and perfomlance of these institutions?

1.... Objecthes of the Study

The present research work" Role of Institutional Structures at District and Sub-district

levels in Promoting School Quahty in the Context of Universalisation of Elementary

Education III Kamataka" aims a! investigating and studying the organisational and

functional dynamics ot DIETs, BRCs, CRCs, School Complexes and VECs. The study

in essence. intends to examme whether the institutional structures have provided the

expected academiC support in promoting school quality for realising the objectives of

UEc The study mter alia attempts to coin pare the status of UEE in OPEP and Non-

OPEP distncls. More specifically, the objectives of the study are,

I. To examme the status of UEE In Kamataka, Kolar (OPEP) and Tumkur (non-

OPEP) dIstricts.

2, To study the orgamsational structure and composition of DIETs, BRCs, CRCs,

SCxes and VL:Cs.

18

3. To examine the tasks, roles and responsibilities of DIETs, BRCs, CRCs, SCxes

and VECs per the prescribed norms.

4. To study the processes and practices of training and other actIvities of DIETs,

BRCs. CRCs. SCxes and VECs.

5. To study the perceptions and views of trainers, trainees, beneficiaries and other

educational functionaries with special reference to the role-played by DIETs,

BRCs. CRCs, SCxes and VECs in promoting school quality.

6 To identit\ bottlenecks. if any in the operationalisation of DIETs, BRCs, CRCs,

SCxes and VECs

7. To compare the roles played by these institutional in promoting school

quality III the DPEP and Non-DPEP contexts.

1.5 Statement of the Problem

Failure to realise the goal of UEE in Kamataka and the persisting problems of poor

partiCIpatIon. attendance and learning attainment levels across different sections of

society clearly suggest that appropriate strategies are required to address these

problems DPEP is seen as one such strategic intervention to address these issues and

to provide complementarity III the task of achieving UEE. Against this backdrop, the

major focus of the present study is to identify the issues pertaining to the functions and

performance of newly created institutional support structures in improvement of school

quality. The problem selected for the present study is stated as "Role of Institutional

::itructures at DIstnct and Sub-district Levels in Promoting School Quality in the

context of Universalisation of Elementary Education in Kamataka".

19

1.6 Scope and Limitations ofthe Study

Since there has been paucity of studies at the maero level, the sclection of a few

institutional structures of two different developmental and contextual districts in

Kamataka was imperative for an analytical study like this. The present study is limited

only to one DPE? district under phase I and another non-DPEP district under the same

educational division (Bangalore) in Kamataka State. It is expected that the findings

emerging from a study of this type would throw light on the functioning of these

institutions, their problems, their potentials and promises in improving the ~ h o o l

quality in primmy education. It is expected that the present study would not only

provide insights into the organisational dynamics of these institutional structures, hut

also the study outcomes ..... ill have wider implications for effective implementation of

the w1iversal primary education policy in the State of Kamataka.

1. 7 Presentation of the Study

The study has been presented in six chapters. In the first chapter, introduction, the

need and importance, objectives, scope and limitations of the study have been

presented. Chapter two is devoted for the reviews of the related literature. The third

chapter presents the operational definitions of the terms and concepts, the theoretical

frame, sampling procedures, materials and methods, data used in the present study.

The fourth chapter presents analysis of macro data relating to the progress of VEE in

the Karnataka State and in the two districts selected for the present study. Chapter five

is devoted to presentation of analysis, interpretation and discussio.1 of micro data

gathered from the field. Findings of the study, conclusions, implications and

recommendations for future research find place in chapter six.

20

CHAPTER- II

REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

In the first chapter, back!:,'Tound of the study, need and importance of the study,

objectives of the study, scope of the study, limitations of the present study and chapter

schemt were discussed.

While conducting any study, a review of the existing literature in the field is

necessary. The review of related literature besides helping the investigator to acquire

theoretical insights into the field of study also enables (i) to evolve suitable theoretical

and conceptual framework for the study, (ii) to identify research tools and (iii) to

choose proper research and analytical design tor the study. In addition, the review also

helps in identifying research gaps in the area of study.

Literature is replete with studies dealing with issues of school education, in

particular at primary stage in developing countries. By and large these studies have

attempted t;) focus on a variety of factors, both school related and non-school related

which have a bearing on efficacy and effectiveness of school education. However,

researches directly delineating the role of institutional and organisational support

structures for quality improvement in primary education is far and few. In this context,

an attempt has been made in this chapter to present a detailed review of related

studies. The literature reviewed is presented in relation to four broad headings

namelv, (I) studIes relating to UEE, (2) Studies relating to school quality, (3)

StudIes relatmg to school/educational performance/efficiency and (4) Studies

relating to educational management/ administration.

2.1 Studies relating to VEE

In the Indian context, research related to elementary education is a phenomenon of the

post-independence period and UEE is the single most crucial problem in education.

W a ~ t a g e stagnation, non-attendance and non-enrolment, etc. are the major problem

21

,

,

areas and the causes of these problems are both area specific and policy specific and

measures are urgently required to tackle the problem or situation (M B Buch, Fourth

Survey. 1983-88) Even though the number of researches conducted in education over

the years re\eals tremendous progress in terms of numbers, the area-wise analysis of

the same indica:es the extent of neglect or lack of concern for elementary education as

far as its qualitative improvement is concerned. Even a recent trend report (V Survey

of Educational Research, 1988-93) reveals that 6503 research studies have been

conducted in the field of education (up to 1992-93) Of these, only 285 studies (44

percent) are in the field of elementary education.

An analysis of the studies in the field of elementary education (see table 2.1.1 )

re\eals that 9 studies belong to the 50s; 25 to the 60s; 68 to the 70s; 106 to the 80s and

77 to the 90s (up to 1992-93) It may also be seen that increasing attention has been

given to elementary education from 1970s onwards. A further analysis of re:>earches

in elementary education has revealed that only 27 per cent of the researches have

focused on universalisation of elementary education, of which a mere 2 per cent of

studies is doctoral research works.

Table 2.1.1. Number of Researches conducted in the area of Elementary Education

o\er 1he Decades

Theme Decade

f-------

.

. ~ .

L--

50s 60s 70s 80s 9 0 s ~ . _ Total

I

i

I

I

I

,

I

I

History 1 1 2 7 8 19(6.7)

Development -- 3 15 IO 12 40 (14)

Universalization 6 8 20 29 \3 76 (26.7)

Pupil Achievement & Development

--

7 10 17 14 48(16.8)

Curriculum development 1 2 8 32 9 52 (18.2)

F\aluation -- -- 2 1 3 6 (2.1)

School Systems 1 1 6 4 4 16 (5.6)

Teacher and Teacher Traming --

3 4 4 10 21 (74)

Economics -- --

I 1 4 6 (2.1)

Research Needs -- -- -

1 --

I (0.4)

Total

9 25 68 106 77 285

Source:

Grewal and Gupta - Research to Elementary EducatIOn. A Trend Report, IV

Survey of Research in Education, Vol. 11,1983-88, NCERT

Note: * Up to 1993-94

Figures in parentheses indicate percentages.

22

Kamat's (196R) study in Maharastra finds that the progress of primary

education among the land owning peasants was higher when compared to that of the

landless The study highlights the decline in the educational participation of the

labour strata in the rural communities

A study hy Das ( 1969) on the "wastage and stagnation at the elementary level

of education in the State of Assam" indicates that in spite of rapid increase in

educational expenditure, efforts and facilities the rate of wastage a:1d stagnation

remains constant The rate of stagnation and wastage was high among the lower classes

and more with respect to girls

Bihari (1969) in his study on "wastage and stagnation at primary education

among tribal" finds that the reasons for the phenomenon are the inefficiency of the

.

teachers and the lack of consciousness among parents.

Bara (1971) compares the wastage and stagnation at primary stage in Sibsagar

and Golaghat. Major finding of the study reveals that the level of educational wastage

is affected by three sets of factors namely. (a) family related factors ie the poor

physicai, health, attitude towards education and (b) school related factors ie the

sympathetic beha\'iour of teachers, multiple class teaching and (e) single teacher

schools.

Agaf\val's (1972) study on "the wastage and stagnation In Mahendragarh"

reveals that the wastage rate was above 90 percent in the primary stage (up to V

standard) in government tribal schools. The rate of wastage was highest in class I

(60.71 %) and lowest in class V (17.91%). The indices of stagnation also slowly reduce

when one moves up to higher classes. Poor socio-economic status, high teacher-pupil

ratio and the non-availability of textbooks are the reasons cited.

Sharma (1973) in hid study on "Increase in enrolment in primary schools" in

Udaipur and Kota of Rajasthan reveals that the enrolment drives with incentives prove

23

to be more useful In boostmg enrolment Among inCentives, free meals. books.

ofte:xtbooks are proved most ef1ective

Acharya S C (1974) tlnds that problems of phYSical plants. lack of pror-.;riy

qualified and trained teachers, absence of adequate school commulllty are

responsible for dropouts and stagnation

Masavi's (1976) study on "wastage and stagnation in primary education m

Tribal areas in Gujarat" reveals that the rate of wastage during the first four was

to the tlme of 65%. Only 91 % of the total numbers enrolled could complete standard

IV. Wastage was greater for boys than girls. The reasons cited were poverty. ,()CIO-

economic change ignorance of parents, i ii-equipped teachers. .

Patel (1978) exammes the educational opportunities of the children of urban

slums in Delhi in terms of available and the utilisatIOn aspe\.ts The study

reveals that (I) The slum children had inferior physical and material resources and

teachers had l(1w capacity of teaching and low interest, (2) The quality (11'

educational faciiities for the slum children was very much inferior to that of the non-

slum children and (3) In the matter of school resources, the slum children were not

at par with schools in non-slum areas. The discrepancy was seen in school building,

equipment, curriculum, teachers and pupils.

Raj (1979) in a study on " Socio-economic Factors and their mterrelationshlps

among the Out of School Children in Madras" finds that the out of school students

consisted of a greater percentage of girls than boys. Amongst the out of school

children the percentage of SC and Sl students was higher than that of the other b'TOUPS

The number of and left outs were high among chi:dren whose parents were

manual labourers. The incidence of dropouts and nOl1-enrolled were higher an10ng

children who came from large families.

Sharma (1982) carried out a study on the " Effect of stay of tt:acher on

enrolment and retention of boys and girls in Rajasthan". He out that the retention.

attendance and regularity of students were better in schools where stayed at

their headquarters. It also reveals that the teachers' stay was useful only when the

relationship between teachers and parents were courteous.

Acharya (1982) conducted a study of four villages in West Bengal on

"Education and Agrarian Relations". He finds that literacy and enrolment declined

steeply with the hierarchical order of the rural society. Of the 55.83 percent of non-

enrolled children in the age group of 6-16, 25.17 percent belonged to agricultural

poor peasants and lo\\er middle peasant families. The participation of the

lo\\er classes of the agrarian society in the process of organisation of education for

the area was negligible Most respondents from the higher strata opposed the

introductIOn of lJEE even though their children registered a higher percent of

enrolment The:: reasons for their oPPOsition stemmed from fear of losing child

lahour and threa! to traditional authority pattern. On the other hand, the lower strata

not Inclined to UEE since it would result in a net loss to the family income as

the children also contnhute. It was also true that the teachers and leaders of the

villages were no: II1strumental ill creating awareness for education among the lower

strata.

De\I's 11983) study on "Probiem of dropouts in primary schools of Manipur"

indicates that there was a hIgher dropout scale among girls than boys. The four

important causes for were poverty, frequent transfer of residence, repeated

faIlure and neglIgence of parents.

Bhattacharya's (198-l) a study on "Social Stratification and System of

Education" in West Bengal observes that the inequality of educational opportunity

eXIsted in West for a Ion!.! time. The observations of social mobility over three

-

generatIons revealed that a majority of people in the lower social strata remained

SOCIally immobile. whde in the middle class. it was evident to the extent that it operated

\\lthll1 a SOCial boundary. The study also reveals that the inequality of educational

Opportlllllty emerged out of the Introduction of 10!,>1stic support and cultltTlli inequalities

25

at home \\ith the organisational climate and effective!less of the system of social

stratitlcation and the equity.

SIE (UP. 1986) reveals that unattractive environment of school indifference of

,

teachers. irrelevant curriculum, lack of physical facilities like water and ~ n i t l t i o n in

schools wen;: the main causes of drop out of children.

Sachidananda (1989) in a study of Bihar on "causes of the backwardness of

education" cites poverty of rural families, lack of teachers commitment to their duties,

lack of effective supervision and rampant corruption in the supervisory cadre, paucity

vf women teachers, highly politicised teaching community and less representative SC

anc ST teachers as the causes for the backwardness.

Ushade\1 and NagaraJu (1989) examine Census data to assess literacy gams in

Kamat[J.;a. The analysis indicates marked difference in the literacy gains between rural

and urban populatIOn with rural females n:gistering least gains. The differences were

explained by poverty 10 case of urban males and poverty coupled with lack of facilities

in the case of urban and rural females.

Yadav I 199 I) studies the dropout among socially and economically deprived

elementary students 10 Ilarvana and lists out the following causes. While teacht:rs

reported non-detention policy of the State government in classes first to third,

engagement of children in the fields during the sowing and harvesting seasons, heavy

syllabi causmg disinterest 10 pupils, illitera.:y of parents, large family size and poor

teacher-children relationship. The pupils on the other hand reported punishment by

teachers, usc of gUides mstead of textbooks in teaching, parental ignorance of the value

of education and prionty of household works for girls as reasons for dropout

Shanna ( 1992) in his study on the prohlems of non enrolment in the district of

Sibsagar In Assam identifies the causes such as involvement of children in domestic

and non domestic work, parental unawareness of the importance of education, non

congema! home atmosphere, parents' inability to provide school matenals to their

26

wards. difference In the language spoken at home and spoken by the teachers in the

schooL poor parent-teachers' relationship, differential expectations from the parents

and povr physical facilities in school for the non-enrolment.

Vyas et al. (1992) in their study in Rajasthan cites following causes

(personal and school related) for the dropout of children. The personal causes were

poor financial conditions of the family (the most important of all) adverse family

Circumstances, parental un\\<; II ingness, illiteracy of parents, illness/ demise of parents,

lack of inraest or weakness in studies, illness, inferiority complex and difficulty in

findIng a for a literate girl. The school related factors wer':: non-

a\aIlability of lady teachers, co-cducational system and lack of interest on the part of

teachers.

2.2 Studies Relating to School Quality

SchiefelbeIn Farrel and Sepulveda-Stuardo ( 1983) in Chile, one of the more advanced

Latin American countries reveal school factors to be of great importance, with effects

larger than those of family characteristics. Evidence also suggests that children who

are economicall\ and socially disadvantaged are more likely than other children to

bene.lt frum an Incn:ase In the a\aIlability and quality ofschool5.

Heyneman and Laxley ( 1983) examIne the impact of school factors and family

charactenstlcs on student achievement in 29 countries. The study reveals that for the

mne LatIn Amen-:an countrIes In their study school factors explained a significant part

of the \arIance in what students learnt. For e.g. they attributed more than 80% of the

variance In achievement 111 BrazIl and Colombia to the quality of the schooL

Munoz Izquierdo and Schmelkes (1983) and Avalos (1986) in their studies

follO\\1ng SOCIological and anthropological approaches find that teachers' beliefs and

attlludes will have a positive significant dfect on self-perception and success or failure

of puptls. They conlirm that teachers develop negative ideas about the abilities of

27

pupils \vho are lagging behind, which deter them from gIVing these pupils the

assistance that might improve their academic situation. The teaching model does not

distinguish between abilities of pupils with similar, lower or higher learning levels than

the mean for each group. Teachers assigned to poor schools believe that the

responsibility for school failure lies with the families of the pupils. The main problem

is that the teachers do not perceive the mechanisms through which they themselves

contnbute to the determination of the school failures.

Fuller ( 1985) reports that at in non-industrialised countries, the quality of

the school which the child attends influences his or her length of stay in school and

academic achievement. ThiS IS clearer in the poorer countries and among lower

income school children In developing' countries. There are also indications that quality

of what IS learned is more important to later life than are the number of years of

schooling. Am,mg the variables that recur in various studies as an influence on

learning are the ti.)l\owing: active school library, teacher training, time on task and

SOCial ongln of the teacher.

Blf(isall ( 1985) reports that in Brazil rural children as well as urban children