Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Quinua Rural PDF

Загружено:

Carlos Martin Perez Aguilar0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

23 просмотров43 страницыQuinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman. A diverse and robust grain 2 2. Quinua and local agricultural systems 3 2. Malnutrition, under-nutrition and food security.

Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

quinua rural.pdf

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документQuinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman. A diverse and robust grain 2 2. Quinua and local agricultural systems 3 2. Malnutrition, under-nutrition and food security.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

23 просмотров43 страницыQuinua Rural PDF

Загружено:

Carlos Martin Perez AguilarQuinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman. A diverse and robust grain 2 2. Quinua and local agricultural systems 3 2. Malnutrition, under-nutrition and food security.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 43

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

1

Quinua and rural livelihoods in

Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

1 Dr Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

11 Magdalen Road

Oxford OX4 1RW

hellin@fincahead.com

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

2

Quiua and rural livelihoods in

Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Executive summary 1

1 Introduction 2

2 Quiua and Andean agriculture 2

2.1 A diverse and robust grain 2

2.2 Quiua and local agricultural systems 3

2.3 The rediscovery of quiua: Malnutrition, under-nutrition and food security 4

3 Production of quiua in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador 7

3.1 How much quiua is grown? 7

3.2 Yields of quiua 9

3.3 Costs and prices 9

4 Consumption of quiua in the Andes 12

4.1 What do the figures say? 12

4.2 Romanticising an indigenous crop? 13

4.3 Consumer demand for quality quiua 14

5 Wheat imports to Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador 16

5.1 Volumes and prices 16

5.2 Impact of wheat imports on the production of quiua and other domestic crops 19

6 Exports of quiua from Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador 21

6.1 Reacting to demand in the Developed World 21

6.2 La Asociacin Nacional de Productores de Quiua (ANAPQUI), Bolivia 22

6.3 Escuelas Radiofnica Populares del Ecuador 24

7 Quiua and food security: The pitfalls of the export market 26

7.1 Were not talking about coffee and bananas 26

7.2 Natural, social and human capital: Under-appreciated resources 26

7.3 The organic dilemma 27

7.4 Quiua diversity and patents 30

7.5 Cultivation of quiua in Europe and the United States 31

8 What does the future hold? The contribution of quiua to food security 33

8.1 Programa Nacional de Apoyo Alimentario: Peru 33

8.2 The power of mimicry: Win over the urban middle classes 34

8.3 The need for new approaches 35

References 38

Annex 1 - Terms of reference 41

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

3

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Executive summary

Quinua (Chenopodium quinoa) is an annual plant found growing in the Andean region of

South America, between sea level and the heights of the Bolivian altiplano, at around 4000 m

above sea level. Quinua has long been known for its nutritional value and was highly valued

by the Incas. In the last 25 years, there has been a growing interest, on the part of scientists

and anthropologists, in quinua, particularly with respect to its contribution to food security.

One of the problems facing any study of quinuas potential and actual contribution to food

security is that there few reliable data available on the impact of quinua on farmers

livelihoods. Data suggest that the production of quinua has increased in the last 20 years,

especially in Bolivia. However, an increasing amount is for export to the developed world.

One of the biggest obstacles to the cultivation and domestic consumption of quinua is that

food preparation is very labour-intensive. In the Andean region, farmers are increasingly

obliged to work off-farm to supplement farm income. Labour availability to process quinua

for home consumption and/or sale in local markets is increasingly unavailable. Often it is far

easier to consume cheaper bread and/or pasta.

While many commentators have referred to the detrimental impacts of wheat imports on the

consumption of indigenous foods such as quinua, it is hard to support this claim with the data

available. Production of quinua and imports of wheat and wheat flour show no direct

relationship. What is undeniable is that people in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador are so

accustomed to eating bread made from imported flour that domestic consumption of quinua is

unlikely to increase dramatically in the short- and mid-term.

Faced with the difficulty of competing with wheat on the national market, current research

and development efforts seek to encourage the production and consumption of organic quinua

and its export. Case studies from Bolivia and Ecuador demonstrate that this approach is

partially successful. One of the dangers is that quinua thrives in parts of Europe and the

United States. This may undermine the market for Andean-produced quinua. There is also a

risk farmers will focus on a handful of quinua varieties that suit the export market rather than

those that offer them great food security in adverse climatic conditions.

Despite the above uncertainties and ambiguities, quinua does have an important role to play in

local peoples livelihoods. This is particularly the case in rural populations living in extreme

condition such as the Bolivian and Peruvian altiplano. Domestic consumption of quinua in

can increase if the crops image as a 3

rd

class food is improved. In the meantime, Peru has

shown that production and consumption of quinua can be stimulated if it is included in

national food programmes.

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

4

2 Introduction

This report examines the role that quinua plays in local peoples livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru

and Ecuador. Quinua was highly valued by the Incas as a nutritious and hardy crop. After

several centuries of neglect it has been rediscovered by natural and social scientists who see

its potential in terms of its contribution to food security in the region. This reports looks at the

area planted with quinua and changes in production and consumption over the last decade.

Furthermore it examines the likely link between imported wheat and the replacement of

quinua in local peoples diets. A number of case studies of farmers who grow quinua for

export are analysed in order to assess the advantages and disadvantages of producing quinua

for a small but growing market in Europe and the United States (US).

It is important to note that much of this report is based on secondary sources. The authors

field research on quinua was largely confined to the issue of farmers producing quinua for the

export market (Sections 6 and 7). Although there are some data on quinua production,

consumption and internal markets, there is little information on the impact of quinua on

farmers livelihoods. Furthermore, data on the impact of subsidised wheat imports on food

security are not readily available. This is particularly the case with respect to imports and

national debt. Further field research is warranted to clarify the potential contribution of

quinua to food security and rural livelihoods and to gather first-hand information from

farmers on the extent to which cultivating quinua is a viable option.

3 Quinua and Andean agriculture

3.1 A diverse and robust grain

Quinua (Chenopodium quinoa), also known as quinoa, is an annual plant found growing in

the Andean region of South America, between sea level and the heights of the Bolivian

altiplano, at around 4000 m above sea level. The mature plants stand 1 to 2 m high and

produce striking purple and yellow heads of seeds, which turn brown on maturity. The grain

is small (about 2 mm across) and can be used as flour, or toasted, added to soups or made into

bread. Dried, it can be stored for up to ten years. Quinua has long been known for its

nutritional value, having a high protein content and significant amounts of many

micronutrients. For the Incas it was a staple, known as the Mother Grain and because it was

a light and nutritious food, quinua helped sustain the Inca army on its long march through the

Andes (National Research Council, 1989). It complemented the other Inca staple of freeze-

dried potatoes, known locally as chuo and like quinua, still consumed today.

As a species, quinua is highly variable. It is more a complex of sub-species, varieties and

landraces (National Research Council, 1989), which allows it to survive in an extraordinarily

wide range of harsh ecological conditions. Once established, quinua can survive levels of

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

5

drought, salinity and frost in which other crops would perish. In Bolivia, near the famous salt

lakes of Uyuni, quinua grows in areas which receive only 200 mm of rainfall per year, in

saline soils and conditions of frost on over 200 nights per year (Sven Jacobsen, Centro

Internacional de la Papa, Lima, pers. comm.). During the day the sun dries the air

mercilessly. At night the temperature plummets to well below freezing. There are few plants

which produce a useful crop under these conditions, and thus few alternatives for farmers to

cultivate in such areas.

Largely because of its ability to survive and produce under such conditions, quinua remains

an important crop in three main regions of the Andes, all located between 3,200 and 4,200 m:

the northern Altiplano (around Lake Titicaca on the Bolivian and Peruvian border); the

southern Altiplano (around the salt flats of southern Bolivia) and the highland valleys of

central Peru, mainly around the Mantaro Valley (Gar, 2000). In these three areas alone, some

56,000 hectares (ha) of quinua were cultivated in 1998, producing about 80 % of Andean

quinua production (Aroni, 1999; Arca, 1999). Significantly less quinua is cultivated in

Ecuador.

Quinua is variable too, in the type of grain it produces. In some areas, notably southern

Bolivia, native quinua varieties tend to be large grained and bitter, with rapidly germinating

seeds and quick maturation times. Further north, there are more varieties of sweet quinua,

with small grains and a longer growing cycle (Alejandro Bonifacio, Fundacin para la

Promocin e Investigacin de Productos Andinos (PROINPA ) La Paz, Bolivia, pers. comm.).

The colour also varies widely, ranging from white through pale yellow, orange, red and black.

Despite its hardiness, Quinua is susceptible to a variety of pest and disease problems. In the

dry southern Altiplano, insect pests cause greater damage. Moving further north and with

increasing humidity, diseases such as mildew become more important. Sweet varieties in

particular, are subject to severe depredation by birds: not only do they eat the grains,

immature grains are also shaken from the seed head and wasted. Up to 25 % of the crop can

be lost this way (Juan Perez, Escuelas Radiofnica Populares del Ecuador (ERPE),

Riobamba, Ecuador, pers. comm.).

3.2 Quinua and local agricultural systems

Andean agriculture, particularly in the altiplano areas of southern Peru and Bolivia, is based

on systems of crop rotation, which emphasise diversity, environmental risk management and

food security. It is traditional to sow a mixture of quinua varieties in any one area. Some

varieties are valued for their ability to withstand drought, frost, and salinity. Other varieties

are grown largely for their market value, and nutritional or gastronomic qualities. For

example in the northern Altiplano area around Lake Titicaca, native varieties such as

Kiankolla has a high resistance to frosts; Blanca de Juli has good market value; kkotio is

valued for its nutritional and gastronomic qualities. Cultivation of a range of varieties

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

6

contributes to farmers security, particularly in a risky environment. This is especially

important for poor farming households cultivating marginal lands (Gari, 2000).

In the northern Altiplano, crop rotation generally involves alternation of potato or another

tuber, followed by quinua and finally a cereal, such as barley, or perhaps a legume. If land

pressure permits, the land is left in fallow for four to eight years, and is used during this time

for grazing of animals. However, with decreasing areas of land available for use, farmers are

often forced to reduce the fallow period. In the southern Altiplano, the traditional system

comprises potatoes in rotation with quinua and fallow, the cycle lasting 10-12 years. There is,

however, a myriad of variations of these systems depending on topography, rainfall, soil type

and land tenure.

In the altiplano, traditional forms of land management still exist. The system of Aynuqa has

traditionally regulated the balance between cultivated land and fallow, grazing land. An

aynuqa is a collection of plots, communally owned, but individually worked and inherited.

The individual plots within an aynuqa are managed in a co-ordinated manner, with periods

designated for crop cultivation; grazing of crop residues; grazing of regrowth, or firewood

collection. Each aynuqa is enclosed by a communal wall, which helps to protect crops from

grazing animals and frost, while minimizing individual labour requirements. This allows a

smaller number of shepherds to watch everyones animals and reduces individual wall-

building and maintenance costs. The aynuqa is managed and regulated by a traditional

organisation, the ayllu (Laguna, 2000). Increasingly, however, the ayllus and aynuqas are

disappearing, weakened by migration, and the increasing intensification of quinua production

where the focus is on an individualised export market (see sections 6 and 7).

3.3 The rediscovery of quinua: Malnutrition, under-nutrition and food

security

For centuries, quinua has been ignored by non-indigenous peoples as a potential agricultural

crop. Following the Spanish conquest of the Incas, traditional crops such as quinua, were

deliberately repressed and replaced with European species such as wheat, barley and broad

beans (National Research Council, 1989), a culinary colonialism that continues to a large

extent today. Whilst extensive crop improvement programmes have focussed on the better

known cereals such as wheat and barley, indigenous crops like quinua have remained

largely untouched by science.

The advantage is that there remains a vast array of locally-adapted varieties which have not

been replaced by more productive improved varieties. Conversely it means that yields are low

and, therefore, while quinua may be able to survive in a range of extreme or marginal

environments, it is not as productive as the improved cereals when grown in favourable

agricultural conditions.

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

7

In the last 25 years, there has been a growing interest, on the part of scientists and

anthropologists, in indigenous crops and the potential they offer both in the Andes and world-

wide. Quinua has attracted much interest in development circles because of its potential

contribution to food security, particularly its ability to provide good quality nutrition in

regions with problems of under-nutrition and malnutrition. Quinua is a source of a wide range

of nutrients, with a similar energy content to, but higher protein levels than other cereals. For

example, the protein content of quinua typically ranges from 14 to 16 %, (different varieties

of quinua have different nutritional properties) while that of wheat tends to be about 10 %,

rice 7.7 % and corn 10.2 % (Macdonald, 1999).

While quinua contains significant amounts of many micro-nutrients, it is deficient in some

essential amino acids and therefore works well when eaten in combination with other foods,

particularly legumes like beans, or animal products. Despite the frequent claims made for the

exceptional nutritional quality of quinua, studies of the effect of quinua in the human diet are

few, although they are suggestive of its beneficial effects (Macdonald, 1999). Hence, while

quinua may chemically be a good source of certain nutrients, it is less well-know how easily

these can be absorbed and utilised by the human body. Its potential contribution to aspects of

food security is unclear and remains unproven.

Following the World Food Summit in November 1996, The Rome Declaration on World

Food Security was issued. Food security was defined as food that is available at all times, to

which all persons have means of access, that is nutritionally adequate in terms of quantity,

quality and variety, and is acceptable within the given culture. Traditionally the focus of

many food security initiatives has been on the problem of ensuring an adequate supply of

food. However, whilst adequate food supply may be available in total, not all members of the

population necessarily have the resources to obtain it. Those most at risk from food insecurity

are the marginalized urban poor and the rural population who are either land-poor or landless.

These groups of people often cannot supplement their diets with home-grown foods.

The issue of quinuas potential contribution to food security is further clouded by the

inconsistency surrounding estimates of the degree of malnutrition and under nutrition in the

Andean region. A recent United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID)

electronic forum entitled Hunger and Poverty, pointed out that the results obtained from

studies of food security and malnutrition may depend on who carries out the monitoring. For

example, governments may be tempted to portray an overly positive picture of food security

in order to demonstrate a policy success. In addition, there are no commonly-agreed

indicators of food security, leaving research open to manipulation.

Studies carried out at particular times of year (e.g. before, during and after harvest) or during

different years, may produce different results in the same population. Most studies have

focused on the provision of macronutrients, with little information available for micronutrient

intake, especially for adult women (Macdonald, 1999). According to some sources, acute

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

8

malnutrition does not appear to be a widespread problem among Andean people. Several

studies have suggested that on average Andean peoples energy intakes range from 80 to over

100% of the required calories. The high consumption of tubers and a mix of different grains

means that on the whole, protein levels may be adequate (Tripp, 1982).

However, although the quantity of protein appears to be adequate, analysis of protein quality

does not seem to be well documented (Macdonald, 1999). The average adequacy of the diet

doubtless conceals severe extremes of nutritional levels. Acute malnutrition, as assessed by

weight-for-height, does not appear to be a widespread problem, especially for children

beyond 24 months of age (Macdonald, 1999). According to another study from 1988, acute

malnutrition was uncommon in Ecuador, and was concentrated among children aged 12 to 23

months (Freire et al., 1988, cited in Macdonald, 1999).

However, other researchers suggest the opposite. In the Ecuadorean Andes stunting has been

reported at levels of 57 to 67 % (Leonard et al, 1993 and Freire et al, 1988, cited in

Macdonald, 1999). Stunting is indicative of chronic under-nutrition. In addition, other studies

(Ayala, 1999) suggest that 50 % of the Peruvian population is affected by chronic

malnutrition, defined as an insufficient quantity and quality of food. The same study suggests

that approximately 45 % of the Peruvian population combine under-nutrition and malnutrition

at different stages of life, where inadequate food availability during childhood leads to obesity

and other medical problems later in life because of a growing preference for junk foods.

Despite confusion over the precise nutritional status, there is little doubt of the need for

improved nutrition and food security among the Andean population, both rural and urban.

What is less clear is the best means of achieving this. Many researchers and development

workers were concerned in the early 1980s at the downward trend in quinua production,

partly caused by cheap and alternative food products made from wheat (Section 5). For

example, research in three rural communities in northern Ecuador in 1980, demonstrated that

in 89 households, only 5 percent of total meals in a 24-hour period contained quinua (Tripp,

1982). Development practitioners speculated that quinua, with its high protein content, could

be promoted within the Andean region to improve nutritional levels of farmers producing the

crop and of the urban population who might consume it, whilst supporting smallholder

farmers to remain productively on the land.

One of the major problems facing any study of quinuas potential and actual contribution to

food security is that there few reliable data available about quinua production levels (Section

3), nor the amount of quinua which is destined for domestic consumption in, (Section 4) and

export from, the three focus countries of Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador (Section 6). It is,

therefore, exceptionally difficult to determine the degree to which projects that encourage

farmers to produce quinua for the market, either national or international, automatically have

beneficial impacts on the nutritional status of the family. A recent study in Ecuador

(Macdonald, 1999) examining the impacts of an agricultural development project in the

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

9

highlands, concluded that it is not clear that re-introducing quinua cultivation necessarily

improves the nutritional status of families, especially of women.

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

10

4 Production of quinua in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

4.1 How much quinua is grown?

Centuries of neglect from outsiders and disdain from the formal agricultural sector led to a

decline in the area of quinua cultivated. Until the 1980s, the area planted with quinua dropped

continuously. It is estimated that in Peru the area cultivated with quinua per annum fell from

47,000 ha in 1951 to 15,000 ha by the 1970s (according to Tapia et al, 1979, quoted in Gar,

2000). Since the 1980s, the area of quinua in Bolivia and Peru has been increasing (data from

FAO Statistical Database), with sharp increases seen in production in Bolivia during the mid-

1980s and late 1990s (Graph 1). The area planted with quinua in Ecuador, by contrast, has

remained very low, fluctuating between 500 and 2000 ha. Quinua in the northern Altiplano of

Peru now comprises about 10 % of the cultivated land (INEI, 1996). However, it should be

noted that less than 10% of the total land area of the northern Altiplano is estimated to be

suitable for agriculture and as a result there is a shortage of land. (Instituto Nacional de

Estadstica e Informtica,1996).

It is estimated that 70 % of peasant households on the Bolivian side of the northern Altiplano

have less than 10 ha (Risi, 1994, cited in Gar, 2000). However, there is much variation, for

example in Escoma, on the eastern shore of Lake Titicaca in Bolivia, the authors were told

that the 1992 census had revealed that each family farmed on average only about 0.8 ha

(Gunter Martinez, Centro de Investigacin y Capacitatin Agropequaria, Escoma, Bolivia,

pers. comm.). Studies carried out in the Cusco and Puno areas of southern Peru (i.e. the very

northern end of the northern Altiplano) in the 1985/86 planting period, suggest that each

family cultivated an average of 1.7 ha, but only 20 % of families sowed quinua. When it was

sown it occupied an average of only 0.07 ha (Benavides, 1993).

In the southern Altiplano, approximately 19,600 families, out of a total of about 25,000,

cultivate quinua (Laguna, 2000). This area probably endures the harshest of the Andean

environments, with annual precipitation of only 110 250 mm, average monthly temperatures

fluctuating between 8 and 20 C, and 200-250 days per year with temperatures falling below

0 C. Families in some areas of the southern Altiplano rely almost entirely on quinua

production, to the exclusion of other crops or livestock, and intensively cultivate an average

of 6-7 ha per family (Laguna, 2000).

In Central Peru, the Mantaro Valley comprises the third largest quinua cultivating area (after

the northern and southern Altiplano areas). The Mantaro valley is a wide, flat agricultural area

at about 3,300 m altitude, which leads into a series of tributary valleys and associated

highland areas. The area planted with quinua in the Mantaro valley has increased

significantly in the 1990s, almost doubling between 1994 and 1998 (Gar, 2000) from 2000 ha

to about 4,000 ha of quinua. This represents about 15 % of Perus quinua production.

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

11

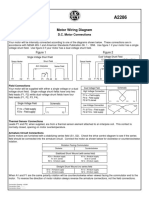

Graph 1 Area of quinua cultivation, Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador,

1961-2000 (Source: FAO Statistical Databases, FAOSTAT)

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

1

9

6

1

1

9

6

3

1

9

6

5

1

9

6

7

1

9

6

9

1

9

7

1

1

9

7

3

1

9

7

5

1

9

7

7

1

9

7

9

1

9

8

1

1

9

8

3

1

9

8

5

1

9

8

7

1

9

8

9

1

9

9

1

1

9

9

3

1

9

9

5

1

9

9

7

1

9

9

9

Year

A

r

e

a

(

h

e

c

t

a

r

e

s

)

Bolivia

Ecuador

Peru

Quinua, although traditionally grown in Ecuador, is cultivated on a much smaller scale than in

Bolivia and Peru. The milder climate of the green Andes of Ecuador and northern Peru,

characterised by adequate rainfall and little climatic variability, permit alternative crops to be

viable, hence, reducing the need to rely on quinua. Land pressure in many upland areas of

Ecuador is a disincentive to growing quinua. In Riobamba average land holdings are only 0.8

hectares per family (Juan Perez, ERPE, Riobamba, Ecuador, pers. comm.). Higher humidity

levels in Ecuador also encourage greater disease problems for quinua.

4.2 Yields of quinua

Yields of quinua in the Andean countries are low in comparison with production levels of

grains such as wheat and also in comparison with quinua which is grown in the developed

world. While the average yield per ha of quinua in 1998-2000 was between 0.5 and 0.98

tonnes in Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru (data from FAO Statistical databases), yields of wheat in

the US averaged 2.8 tonnes. Meanwhile, a trial of quinua production in Portugal in 2000,

resulted in yields of 5 tonnes per ha, a difference attributed to irrigation and mechanised,

uniform cultivation (John Hedger, University of Westminster, UK, pers. comm.). Work on the

profitability of quinua cultivation in Europe carried out by a project funded by the Food and

Agriculture Organisation (FAO), CIP and the Danish aid organisation, DANIDA project,

suggests yields in Europe of between 2 and 4 tonnes per ha.

In examining production of quinua in the Andes, the figures available need to be taken with a

pinch of salt. In Ecuador, groups working with quinua producers anticipated yields of 0.9 - 1

tonnes per ha (extension agents with ERPE, Riobamba, Ecuador and Rodrigo Aroyo

(Inagrofa), pers. comm.). This compares to FAO statistics that indicate average yields of 0.5

tonnes per ha. In Bolivia, an average yield of 0.7 0.9 tonnes per ha in 2000 was considered

an exceptionally good harvest (Asociacin Nacional de Productores de Quinua (ANAPQUI),

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

12

La Paz, Bolivia, pers. comm.). The FAO figure for that year was calculated at 0.5 tonnes per

ha. The overall yield in Bolivia was also expected to be high in 2000, with a harvest of 35-

40,000 tonnes. The FAO databases give the 2000 harvest as only 25,000 tons. The true

picture of quinua production in the Andean countries is therefore not clear.

Sources in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador all pointed out that a lot of the quinua which is sold in

Ecuador and Peru, is actually Bolivian in origin. This is particularly the case with so-called

Quinua Real, the large, white grained quinua, which is only grown in the southern Altiplano

area. Thus, official figures for production, sales and exports from all three countries are

probably missing a large portion of illicit trade in quinua between the three countries.

4.3 Costs and prices

A large proportion of the quinua produced in Peru and Bolivia is destined for home

consumption and is, therefore, never sold on the market. However, in Bolivia, where

commercialisation of quinua has had the biggest impact, farm-gate prices of quinua rose

almost 50 % between 1986 and 1999, from US$ 0.54 per kg to US$ 0.75 per kg in 1999.

Organic quinua, although commanding a slightly higher price (US$ 0.93 per kg in 1999), does

not seem to receive enough of a premium to make up for additional production costs (Laguna,

2000). In 2000, Bolivian farmers were being offered approximately US$ 0.70 per kg, a

reduction on the 1999 price. The authors were told that private buyers were offering only US$

0.28 per kg in local markets.

Although price reductions in 2000 were due to the exceptionally large harvest in the same

year, in Bolivia, there is no obvious relationship between the increasing production of quinua

and the price offered to farmers (Graph 2). Note that the very low prices seen in 1985 and

1986 were during a period of hyperinflation in Bolivia, distorting the price. The price of

quinua has risen in Bolivia along with production. This suggests an increase in demand.

Both price and production have levelled off in Bolivia since about 1998. However, the

relative value of quinua has changed over the past 20 years. At the start of the 1980s, quinua

producers needed to exchange 91 kg of quinua for 45.5 kg of sugar (Laguna, 2000). Relative

price changes now mean that the opposite applies: 45.5 kg of quinua buys 91 kg of sugar.

There is further confusion because it not at all clear, when the full costs of labour, land and

inputs are taken into account, whether the cultivation of quinua is profitable. Several studies

of quinua production suggest that, when labour costs are taken into consideration (i.e. the

opportunity cost of not working elsewhere, or the actual cost of employing paid labour) and

land costs, the net income from quinua is negative.

Based on prices from 1995/96, Salis (1993) calculate that the yield from one ha of quinua in

the Cusco area of Peru was 900 kg. At the time, quinua was sold for $US 0.37 per kg. This

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

13

represented a net loss of US$ 198 per ha if the entire 900 kg was sold. In 2000, the Peruvian

governments National Food Programme, Programa Nacional de Apoyo Alimentrio

(PRONAA), were paying $US 0.61 per kg for good quality, but uncleaned quinua (see section

8.1). This price is considered high by others working in the sector, who are also trying to set

up commercial deals, and who consider that US$ 0.43 per kg was a fair market price in 2000.

In 1990, a study of quinua production in five provinces of Ecuador, looked at the profitability

of quinua production across a range of farm sizes and agricultural systems (Campaa and

Nieto, 1990). This study concluded that the biggest variable in production costs was that of

labour. Calculations of the profitability of quinua were hampered by the fact that production

figures varied from 0.25 to 2.180 tonnes per ha. In this study quinua was profitable in all

cases except in the lowest yielding farm.

Graph 2 Quinua production and price, Bolivia 1984-1999

Source: FAO Statisitical Databases FAOSTAT and Laguna (2000)

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999

Year

P

r

o

d

u

c

t

i

o

n

(

t

o

n

n

e

s

)

$0.00

$0.10

$0.20

$0.30

$0.40

$0.50

$0.60

$0.70

$0.80

$0.90

P

r

i

c

e

(

U

S

$

)

Production Price per kg

The ERPE project (see section 6.3) is encouraging farmers around the town of Riobamba in

Ecuador to join their programme of quinua production for export. ERPEs field staff estimate

that 1 ha of land producing 900 kg of quinua would produce a profit of US$ 431. The ERPE

project offers farmers a price, which in 2000 was fixed at US$ 0.63 per kg for uncleaned

quinua ($ 0.74per kg clean). Rodrigo Aroyo, who runs an agricultural export business called

Inagrofa in Quito, Ecuador, pays farmers a farmgate price of US$ 0.66 per kg for

conventional quinua or $0.77 /kg for organic, uncleaned quinua. These figures are similar to

those paid by PRONAA in Peru.

There is, therefore, much variation across in the region in the farm-gate price of quinua. In

addition, there is very little consensus on whether quinua production is profitable. It could be

argued that in most cases the increased area planted to quinua is indicative of the fact that for

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

14

many farmers it is a priority crop to grow. Whilst figures on the area sown to quinua and the

price paid to farmers are important, of more immediate concern to development practitioners

is the extent to which quinua is consumed in the Andes, and the degree to which subsidised

food imports undermine quinua consumption.

5 Consumption of quinua in the Andes

5.1 What do the figures say?

Quinua is traditionally a food of the rural population in the Andes and a large proportion of

production is destined for home consumption. In Puno, Peru, it is estimated that in recent

years, 60 % of the average 10,000 tonnes per annum produced in the province is for home

consumption, while 20% goes to the local market and a further 20% to local and Cusco-based

processing plants. Farmers produce different varieties of quinua, depending on the expected

end-use: 60-70 % of the area is sown with a mixture of varieties, for home use. The remaining

30-40 % is sown with commercial varieties (Ordinola, 1999).

However, although important in the diet, it seems that quinua is not a staple, in terms of its

inclusion in a majority of meals. A survey of 800 housewives in six provinces of Peru at the

end of 1996, found that 5.5 % included quinua in breakfast, 1.1 % in lunch and 0.9 % in

dinner. Whilst 90 % of respondents consume quinua in some form (from daily to irregularly),

it was not generally eaten on a daily basis. According to a study in Nunoa, Peru in 1988

(Leonard and Thomas, 1988, cited in Macdonald, 1999), quinuas energy contribution to the

diet had decreased from an average of 238 calories per day to 22 calories per day over 20

years. Similar patterns of low levels of quinua consumption have apparently also been

recorded in Bolivia and Ecuador (Kim et al, 1991; Tripp, 1982, cited in Macdonald, 1999)

during the 1980s.

A study by Tripp (1982) in Imbabura, Ecuador, found that quinua was a constituent of only 5

% of meals in a 24-hour period. However, according to a more limited survey carried out at

the same time in three different communities in Imbabura, 30, 60 and 90 % of households had

eaten quinua within the previous week. Quinua consumption was clearly very variable

between communities within the same area.. Another study carried out in five provinces of

the Andean sierra in 1989 found that 35 % of rural families consumed quinua (Nieto &

Andrade, 1990), although it did not look at how regularly.

Urbanisation and changes in working patterns also have an impact on patterns of consumption

of quinua. In 1996 in Peru, a survey found that in 15 farming communities in the Cuzco

Province, quinua was frequently eaten all year round, but particularly during seasons of

harvest and sowing. In contrast, consumption in urban areas tended towards cheaper and more

easily available products (Ayala, 1999b) (see Section 5 on the impact of wheat imports on

quinua consumption).

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

15

5.2 Romanticising an indigenous crop?

Many projects over the past two decades have sought to introduce or reintroduce the

cultivation of quinua, in the hope that this will promote consumption and improve food

security (Tripp, 1990). It seems intuitively illogical not to use a resource as nutritious and

locally available as quinua would seem to be. But are we in danger of romanticising an

indigenous crop, and thereby ignoring some of its drawbacks? Are there perfectly rational

reasons why quinua is not consumed widely by local peoples? The answers may lie in the

labour costs of cleaning quinua and water availability in rural areas.

When the mature quinua crop is harvested, a number of processing steps are needed before

the grain can be consumed or stored. It is a time consuming process and very labour-

intensive, especially when carried out manually, as in the majority of cases in Peru, Bolivia

and Ecuador. Once harvested (during which some grain is lost due to the irregular maturation

of grains on one stalk) the grain is dried in stacks, threshed, winnowed, dried again and then

de-bittered. Losses through the post-harvest processes are estimated to be over 40 % (Salas,

1999). The final result of manual processing is often a poorly cleaned product, contaminated

with dirt and stones.

The bitterness in quinua derives from a chemical called a saponin. Each quinua grain is

contained within a hard coat or pericarp, which contains 0-6 % saponin, depending on the

quinua variety. Saponins are toxic and distasteful and must be removed before consumption,

often an exhaustive process. At an industrial level, removal of the saponins presents two

problems: the high cost of drying the grains and the disposal of the contaminated water

following washing. Industrial processes may involve washing the grains, dry, mechanical

dehulling or a combination of the two. Dry processes entail lower costs and are less polluting

but only remove about 80 % of the saponins (Salas, 1999). Mechanical de-bittering is

therefore limited to the least bitter varieties of quinua.

Normally at a household level, the grains are washed and rubbed with stones to remove the

bitter outer coats. The other limiting factor to the rural consumption of quinua is, therefore,

access to sufficient water. In general, the removal of the saponins has been identified as one

of the main constraints to increased consumption at the household level, particularly the

increased labour demands (Macdonald, 1992).

The impression that there is often a surplus of labour in rural areas is often a fallacy. In many

parts of the developing world and especially in the Andean region, farmers and their families

are increasingly obliged to work off-farm to supplement farm income and provide consumer

goods (Zimmerer, 1993). The root cause of this is often increased costs of production and

reduced returns to labour, forcing farmers to seek off-farm income generating activities

i

.

Throughout the Andean region, temporal migration is a way of life for many communities,

especially in the southern Altiplano. For many years, men migrated to the mining

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

16

communities, leaving their families to care for the animals (sheep and llama), which were

subsequently sold or bartered in the mines. With the closure of many mines in the 1980s,

large numbers of former emigrants returned to their communities. Some of these returnees are

now engaged in the production of quinua for the market (Laguna, 2000). Others continue to

migrate temporarily elsewhere in Bolivia or abroad (Gar, 2000). In Bolivia, for example,

farmers from the altiplano have migrated to the Amazonian lowlands to grow soya bean,

coffee and coca. These farmers retain land in the altiplano and the detrimental impact on farm

management of this temporary migration has been well documented (e.g. Zimmerer, 1992).

In areas such as Sucre, in Bolivia, the labour intensive harvest of quinua, coincides with a

seasonal migration to the cotton, sugar cane, soya and wine producing areas (Oscar Barea,

PROINPA, Sucre, Bolivia, pers. comm.). In areas with significant seasonal migration,

women are often left in charge of the farm. Labour availability to process quinua for home

consumption and/or sale in local markets is increasingly unavailable in many rural areas.

There is a counter argument that if quinua can be made a commercial crop, generating high

enough incomes to obviate the need for migration, sufficient labour may be available for the

post-harvest processing.

5.3 Consumer demand for quality quinua

Quinua is a rustic crop. It is produced largely by small farmers, and any excess to home

consumption is often sold as a mixture of varieties, processed by small companies and

distributed by a network of individual intermediaries. At all stages in this chain, there is a lack

of quality control. At each stage in the market chain, quinua from different sources may be

mixed together, so that good quality quinua will be mixed with other varieties and impurities

by the time it reaches the consumer. For example, in Puno in 1999-2000, there were 49

processing plants, mostly small and informal, with a lack of adequate infrastructure and poor

quality control (Ordinola, 1999).

Intermediaries who collect quinua from the smallest local markets and transport it to the

wholesale market in cities like Lima in Peru, constantly mix quinua from different producers

and markets. By the time the quinua arrives in Lima, and is bought in the retail market by the

poorer urban consumers, even good, clean quinua is mixed up with poor quality grain. Prior

to consumption it must be washed several times, and cleaned of debris.

A survey of housewives in Peru, found that the need for further cleaning of purchased quinua,

first to remove dirt and stones, and secondly to wash out the remaining bitterness, was a

major limitation to the market (Ordinola, 1999). It is not surprising then, that urban

consumers, within the Andean region, are put off buying quinua, despite its known benefits

(Table 1). Quinua sold in supermarkets is of better quality and subject to some controls, but is

sold at such a high price that it is beyond the reach of the low-to-middle classes which make

up the majority of the urban population.

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

17

Table 1 Perception of quinua by potential urban consumers in six

provinces of Peru (Lima, Huaraz, Huancayo, Ayacucho, Cusco

and Puno (Ordinola, 1999)

Positive attributes of quinua Negative attributes of quinua

Highly nutritious

generally with a pleasant taste

a natural, environmentally sound

product

well known

easy to digest

not clean and containing many impurities;

sometimes bitter, where inadequately cleaned

expensive

not consistently available

difficult to prepare

As populations of the Andean countries become increasingly urbanised and linked to the

market, people tend to seek both cheaper and easier alternatives to foods such as quinua.

There is no doubt that wheat products bread and pasta fit both these criteria. According to

Laguna (Laguna, 2000), in 1999 in Bolivia, the farmer who sold 45.5 kg (one quintal) of

quinua, without removing the saponin, received a price of about US$ 35, with which they

could buy about 81.8 kg (1.8 quintals) of pasta ready for cooking. Given the lengthy

preparation necessary for the consumption of quinua, it is much simpler to boil pasta.

Rising prices of quinua, whilst potentially being good for farmers, in terms of providing them

with a better income, may also provide an incentive for farmers as well as the urban poor, to

turn away from consuming quinua and substitute it with bread and pasta made from

subsidised, imported wheat. It is often far easier and cheaper for both rural and urban

households to purchase pasta and/or bread.

In the context of high labour demands, reduced labour availability, and competition from

cheaper alternative foods, it is clearer why efforts to promote quinua for local consumption

have been only partially successful. The issue of cheap imports is considered below. The

question of quinuas contribution to rural household livelihoods via production for export is

discussed in Section 6 and 7.

6 Wheat imports to Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Since the 1950s, the massive imports and donations of wheat arriving to the

Andean countries have constrained the cultivation of quinua, confining it to rather

marginal and upper Andean lands, and driving it away from the gastronomy of

many cities, towns and households (Gar, 2000).

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

18

6.1 Volumes and prices

Wheat has been imported into Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador in large quantities for approximately

50 years. While many commentators have referred to the detrimental impacts of wheat

imports on the consumption of indigenous foods such as quinua and locally-produced rice and

wheat, it is hard to identify cause and effect using the data available.

Statistics available for the import of wheat and wheat flour into Andean countries are not

always consistent (for example, the comparison of data available from US Department of

Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service Global Agriculture Information Network [GAIN]

and those available through the FAO Statistical database), but they do show the same trends.

Wheat and wheat flour imports (wheat equivalent) to Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador have

fluctuated over the past 40 years as shown in Graph 3.

The striking trend is the huge and consistent increase in imports of wheat and wheat flour to

Peru, whilst in Bolivia and Ecuador, volumes have remained more constant. Over the five

years, imports of wheat and wheat flour to Peru have levelled off somewhat, although Peru

remains one of the major wheat importers in the world (USDA, 2001a).

Wheat and wheat flour may be imported in a number of different ways: as food aid (either

donated or on long-term credit supported by the US or other governments) or as commercial

imports. Wheat and wheat flour exports from the USA to Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru, (actual

for January to December 2000 and planned food aid for financial year 2001) are shown in the

table 2 (USDA 2000; USDA 2001b).

Graph 3 Wheat imports to Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador,

1961-1999 (Source: FAO Statistical Databases FAOSTAT)

0

200,000

400,000

600,000

800,000

1,000,000

1,200,000

1,400,000

1,600,000

1

9

6

1

1

9

6

3

1

9

6

5

1

9

6

7

1

9

6

9

1

9

7

1

1

9

7

3

1

9

7

5

1

9

7

7

1

9

7

9

1

9

8

1

1

9

8

3

1

9

8

5

1

9

8

7

1

9

8

9

1

9

9

1

1

9

9

3

1

9

9

5

1

9

9

7

1

9

9

9

Year

V

o

l

u

m

e

(

t

o

n

n

e

s

)

Bolivia

Ecuador

Peru

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

19

Table 2 Wheat and wheat flour imports from the United States

Country Commodity volume 2000

(Tonnes)

Value 2000

(000$)

expected

volume 2001

(Tonnes)

expected value

2001 (000$)

Bolivia wheat flour 36,195 6,609 17,990 3,903

wheat 6,457 796 15,820 2,041

Ecuador wheat flour 21 10 - -

wheat 205,827 26,857 61,130 8,349

Peru wheat flour 9,023 2,055 1,530 332

wheat 266,620 29,582 123,210 16,250

Evidently, the US is not the only country to export wheat and wheat flour in vast quantities to

the Andean region. According to the USDA FAS GAIN report for Ecuador, 2001 (USDA,

2001c), in Marketing Year (MY - July to June) 2000/2001, imports of US wheat to Ecuador

were expected to be 180,000 tonnes out of a total 420,000 tonnes. (It should be noted that this

figure of 180,000 tonnes differs from the figure of 205,827 tonnes for calendar year for wheat

imports above. This may be due to the different time span over which volumes were

calculated.)

According to the GAIN Report, in 2001/2002, imports of US wheat to Ecuador are expected

to rise to 200,000 tonnes of a total 450,000 tonnes. The US contributes less that half of the

total wheat imports to Ecuador. In Year 2000, Canada was the only other exporter of wheat to

Ecuador, holding 60 % of the market. At other times, Argentina and Uruguay also contribute.

The GAIN report suggests local production of wheat in Ecuador is more likely to decline than

increase in future. The main reasons are the lack of incentives, suitable planting land and lack

of adaptable seeds. According to the USDA FAS figures, 50,000 tonnes of wheat was

imported into Ecuador under Section 416(b) regulations in 2000, and a further 30,000 tonnes

under Title I provisions of Food for Progress. This means that the former was donated to

Ecuador (under the US scheme for disposing of its surpluses), while the latter was provided

on long-term credit terms, with a minimum payment holiday of seven years, in return for

liberalisation of Ecuadors agricultural economy for imports of US commodities.

At the same time, Ecuador reduced its tariffs for imports of wheat and wheat flour to 10 and

20 % - presumably the pay-off for wheat supplied under Food for Progress. According to the

GAIN Report, the decision to reduce import tariffs for US wheat, stems from a desire to halt

the increase in the price of bread and pasta occurring in Ecuador during the previous two

years, due to devaluation and the transition from the national currency, the Sucre, to the US

dollar. Wheat flour remained at a relatively constant price of US$ 15.50 to $ 17.50 per 50 kg

bag during the first half of 2000. Increases in the prices of bread and pasta were largely due to

rising prices of electricity, water, labour and other inputs.

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

20

It is unsurprising that there is apparently a lack of incentives for the production of wheat in

Ecuador. Wheat yields in Ecuador were 800 kg per hectare during 2000 (FAO Statistical

Databases) compared to yields of 2,819 kg per ha in the USA and 2,445 kg per ha in Canada.

6.2 Impact of wheat imports on the production of quinua and other

domestic crops

It is worth a look at the scale of the imports of wheat and wheat flour into the Andean

countries in comparison with the production of quinua over the same period. Graph 4

illustrates the situation in Bolivia. There are two striking observations.

the scales are different by a factor of 10. Imports of wheat and wheat flour dwarf the

production of quinua nationally.

production of quinua and imports of wheat and wheat flour show no direct

relationship. There is no trend to increasing imports in correlation with decreasing

production of quinua. This may have happened prior to 1980, but the figures are not

available.

The situation is similar in Peru and Ecuador: imports of wheat and wheat flour occur on a

completely different scale from the production of quinua. Because the imports totally swamp

quinua production, there is no discernable relationship between the two. However, the link

between the two is a long-term one, going back some 50 years. As Rosemary Thorp points

out (Latin American Centre, University of Oxford, pers. comm., July 2001), people in Peru

and other Andean countries have become so accustomed to eating bread made from imported

flour especially in coastal districts that reliance on imported wheat is second nature to the

population

ii

.

While evidence of a possible link between subsidised wheat imports and a decline in quinua

consumption is not clear, there are data that clearly show that wheat imports have disrupted

the production of locally-grown wheat. In Ecuador, duty-free wheat imports and an

overvalued exchange rate led to significant negative incentives for domestic wheat production

during the 1970s.

During this decade, wheat production in Ecuador fell by 6.0 % per year while wheat

consumption increased. As a result wheat imports grew at a rate of 12 % annually from 1970

to 1982 and self-sufficiency in wheat fell from 54 % to 8 % (Byerlee, 1989). Consumers,

however, benefited; flour prices remained constant between 1973 and 1981, and the real price

of bread fell by 50 %

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

21

Graph 4 Wheat and wheat flour imports and quinua production, Bolivia 1980-1999

Source: FAO Statistical Databases FAOSTAT

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999

year

W

h

e

a

t

a

n

d

W

h

e

a

t

F

l

o

u

r

I

m

p

o

r

t

s

(

t

o

n

n

e

s

)

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

Q

u

i

n

u

a

P

r

o

d

u

c

t

i

o

n

(

t

o

n

n

e

s

)

Bolivia: imports Bolivia, quiua production

Byerlee (1989) also points out that in the 1970s, Ecuadors economy grew rapidly. This was

due to the petroleum boom and resulted in more off-farm employment and an accelerated

rural-urban migration. Real wages paid by farmers in the Sierra almost doubled between 1972

and 1980. This raised the costs to farmers because they could not increase product prices due

to competition from cheap, imported wheat. In addition they could not substitute for labour

through mechanisation. Labour-intensive agricultural activities were neglected.

Farmers in Ecuador also had to contend with the fact that during the 1970s, subsidised fuel

meant that long-distance transport costs declined substantially in real terms and this further

reduced the inland prices of imported and bulky items such as wheat. Ecuador became

dependent on imported wheat and since then, the country has not escaped this dependency.

Cano Sanz, (1987) has also documented the impact of cheap food imports on domestic

production in Colombia. There is strong evidence that subsidised wheat imports undermined

domestic production. In the 1950s Colombia cultivated 176,000 ha. of wheat, by 1987 this

had fallen to 50,000 ha. Wheat imports in Colombia between the mid-1960s and mid-1980s

increased by an average of 9.2 % per annum, some four times faster than the population

growth rate. Consumption of locally-produced rice and maize fell.

Given a strong demand for wheat-based products, particularly bread and pasta, it is very

difficult for quinua to be re-inserted into the national palate again. In addition to this, the

subsidisation of wheat production and export by the north American countries, combined with

reduced tariffs on imports to Andean countries (as with Ecuador in 2000) in an attempt to

keep the urban poor fed, means that quinua cannot possibly compete as a crop for national

subsistence. Faced with the difficulty of competing with wheat on the national market, the

prospect of an export market for quinua becomes increasingly attractive.

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

22

7 Exports of quinua from Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

7.1 Reacting to demand in the Developed World

Over the past 20 years, the demand for health foods in the developed world has increased

enormously. Quinua, seen as a rustic and nutritious grain, has begun to be recognised on these

health food markets. Markets have grown in the USA, Germany, Switzerland and other parts

of Europe for products containing quinua. This potentially provides an export market for

quinua produced in the Andean countries, which can be sold as healthy, environmentally

beneficial, and perhaps as helping poor farmers.

Current research and development efforts can be seen as two-fold: to encourage the

production and consumption of quinua and to encourage its production and export so that

rural families can earn the money that is so needed. But what of the basic contradiction of

producing a highly nutritious native grain in a region where under-nutrition is widespread,

and then exporting it to the richer developed world to use in baby food? Is this really the way

forward?

Food insecurity and malnutrition are primarily problems of distribution not production. It is

often the households ability to obtain food that is critical to ensuring household food

security. As the purchasing power of the household increases, access to food increases

(Kennedy, 1994). In this context, if farmers can produce quinua for an export market and

subsequently their purchasing power increases, then in theory (and practice) quinua is

contributing to household food security.

Quinua farmers are expanding their production in several areas of Bolivia and Peru in order to

sell it onto the export market. In Ecuador, farmers are being encouraged to cultivate quinua

again, in areas where people can only remember it as a plant from their childhood. Quinua

was something our grandparents used to grow, according to one resident of Galte Ambrosio

Laso, near Riobamba in central Ecuador. Similarly, prior to an agricultural project to

introduce quinua growing to rural farmers in Imbabura, Ecuador in the 1990s, local

inhabitants did not grow or consume quinua (Macdonald, 1992; cited in Macdonald 1999).

In response to and partly driving the increasing demand for quinua in the export market, a

number of organisations have started providing assistance in production and marketing of

quinua to smallholder producers in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador. Two case studies, one each

from Bolivia and Ecuador, demonstrate the extent to which the twin objectives of increased

domestic consumption and export of quinua can be met. Furthermore, they illustrate the

potential contribution of quinua to household food security and rural livelihoods.

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

23

7.2 La Asociacin Nacional de Productores de Quinua (ANAPQUI), Bolivia

In Bolivia, there are two major associations working on the production of quinua for export:

La Asociacin Nacional de Productores de Quinua (ANAPQUI) claims to represent some

5000 producers out of a total of 20,000 in Bolivia. The farmers are distributed among seven

regional offices, each representing 20 or 30 communities (see Box 1). The Central de

Cooperativas Agropecuarias Operacin Tierra (CECAOT) has about 150 affiliated farmer

families.

Increasingly, ANAPQUI is looking to the export market largely because the internal market

in Bolivia is unlikely to absorb any more quinua than it does at present. Figures provided by

PROINPA (1999) and ANAPQUI (Bolivian Times, January 2001) for 2000 suggest that

quinua exports from Bolivia total only about 2000 tonnes per annum. This represents about 9

% of the average annual production in Bolivia. However, this does not mean that on average

91% of production is consumed in Bolivia. An unknown quantity of quinua is smuggled

across the border to Peru.

Between them CECAOT and ANAPQUI control some 55% of quinua sales from the southern

Altiplano area of Bolivia. The rest of the sales from Bolivia are channelled through private

buyers. ANAPQUI are aiming to increase its production and export, partly through improving

processing capacity by building a new processing plant in El Alto, just outside La Paz. This

factory will produce pasta and biscuits containing quinua. ANAPQUI already has a

processing plant near Uyuni in south-west Bolivia, allowing them to remove the bitter

saponins from the quinua and process it into quinua flakes. ANAPQUI recognises that the

organisation cannot build an export market overnight.

Box 1 La Asociacin Nacional de Productores de Quinua (ANAPQUI)

ANAPQUI aims to improve the living conditions of its member producers by paying a fair

price for their quinua. Farmers need to be affiliated to a local association to be part of

ANAPQUI, ensuring that they are organised and therefore easier to reach, for both purchasing

and technical assistance.

The price paid to farmers is set before they sow the seed. It is based on the previous years

price, with an increase for inflation. This leaves ANAPQUI vulnerable to fluctuations in the

open market price which is affected by the size of the harvest. For example, 2000 was a

difficult year for ANAPQUI. During 1999, the organisation handled about 2,000 tonnes of

quinua from its members. The price offered to producers for the 2000 harvest was based on

the price for the 1999 crop. Although the average production in Bolivia between 1987 and

1993 was 22,000 tonnes (Bonifacio, 1998), an excellent year for quinua in 2000 resulted in a

massive production nation-wide of over 40,000 tonnes, of which approximately 75 % had

been promised to, and accepted prior to the harvest by, ANAPQUI.

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

24

ANAPQUIs dilemma is intense: the market price has dropped precipitously due to

oversupply in Bolivia. Commercial buyers in the open market can offer about US$0.28 per kg

for quinua - less than half the price ANAPQUI promised prior to the harvest. But to abandon

their producers in a bumper harvest year would be disastrous in building up trust and

expanding markets: however, even the fair trade international buyers have requested a review

of the price, given the market situation.

Some of the farmers who are affiliated to ANAPQUI have qualified for organic certification.

Until 1999, the organic market was mostly in the US. In 2000 the focus shifted to Germany

and the Netherlands. Approximately 80 % of ANAPQUIs production is organic, which

commands an international price some 10-15 % higher than conventional quinua. The high

altitude of the Bolivian altiplano means there are relatively few pests and diseases, making

quinua a good choice for organic production, in Bolivia at least. Further north, with increasing

humidity, mildew becomes a greater problem.

What does ANAPQUI mean in terms of food security? Its difficult to judge but there is

plenty of evidence that in the southern Altiplano quinua is vital to food security. The Salar de

Uyuni in southern Bolivia is the second largest salt lake in the world and at almost 4,000 m

above sea level, it quite literally takes your breath away; a thick sheet of hard white salt that

stretches to the horizon. Further south is a series of snow-capped volcanoes, thermal lakes and

barren salt-encrusted soils. The area is raw, inhospitable and stunningly beautiful.

Extraordinarily and seemingly against all the odds, a number of villages are dotted around the

landscape. On the outskirts of each village, walled gardens have been constructed to keep

out foraging goats. Inside there are patches of tall stalks, each with a head of ripening grains.

This is quinua and it is about the only crop that will grow here. Some of the farmers in this

area are members of ANAPQUI.

Farmers who are producing for the market may well keep some quinua behind for home use;

certainly ANAPQUIs policy is to pay a fair price to producers that allows them to benefit in

the market from their production. It is difficult to envisage, however, how ANAPQUI (a

relatively small organisation with limited access to funds) can survive economically under a

system of offering a fixed price to producers before knowing the level of the harvest and the

consequent market price at harvest: if ANAPQUI is driven out of business by the high prices

it has to pay to producers, which are not compensated by high international sale prices,

producers food security will suffer.

7.3 Escuelas Radiofnica Populares del Ecuador

Ecuador differs from the heights of the Bolivian and Peruvian altiplano and Sierra in that in

many areas it is possible to cultivate other crops. Quinua does not have the same fundamental

importance for food security. However, some local NGOs and producers associations see

quinua as a means to diversification and a route into a stable export market.

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

25

In the highlands of Ecuador, the bustling town of Riobamba is a commercial centre for

agriculture in the steep surrounding mountains and upland valleys. The Escuelas Radiofnica

Populares del Ecuador (ERPE or generally known as Radiofnica), is a community radio

station is based in Riobamba, perhaps an unlikely candidate for a development organisation.

But when Juan Perez of Radiofnica explains the history of the station, it becomes clear why

they are developing one of the largest quinua exporting networks in Ecuador. Radiofnicas

aim is to improve the standard of living for the marginalized indigenous, mixed (mestizo)

and urban populations, in an area where the average land holding is only 0.8 ha (Box 2).

In a similar way to ANAPQUI in Bolivia, Radiofnica sets its offer price for producers before

sowing. Each community or group which wants to be involved brings a list of members and

areas to be planted, and Radiofnica provides the seed and some technical advice. In theory,

from each years harvest, Radiofnica allocates a proportion for the farmers food needs, a

proportion for next years seed and the rest for sale to Radiofnica at the price fixed prior to

sowing. Crucially, perhaps, Radiofnica retains some flexibility in the price, a margin within

which they can vary it. Furthermore, at the moment Radiofnica is less vulnerable to

international price fluctuations because it is cushioned by international donor money and it is

working with far fewer farmers than ANAPQUI in Bolivia.

Box 2 Escuelas Radiofnica Populares del Ecuador

Radiofnica started life as a basic education and literacy radio station almost 40 years ago.

Insufficient funds to finance the radio led them to start their own four-hectare farm in the late

1980s, where the focus was on organic production. As Radiofnica started to broadcast about

their own experiences of organic agriculture in the area, people began to ask for advice and

assistance. Radiofnica started to promote their own organic produce through trade fairs in

Germany and Costa Rica .It became evident that there was an international demand for

organic produce, which could be filled by smallholder farmers in the Riobamba area.

Quinua was chosen as a focus crop, partly because it was being lost from Ecuador. The

communities around Riobamba may once have grown quinua, but its image as a third class

food and the comparative ease of preparation of rice and pasta had pushed it off the menu.

Radiofnicas role is to provide technical advice and provide an international marketing

network for local producers. It has the immediate advantage of access to the radio to promote

quinua, provide basic training and motivate people to join the programme.

In 1997, Radiofnica received its first order from the US, and worked with 220 families to

sow quinua and harvest it in June and July 1998. By 1998, Radiofnica had secured funding

from international donors: three years of funding in which to set up a self sustaining quinua

production and export business. Suddenly quinua has become big business in Riobamba and

by 2002 they aim to involve 4,000 families in production of 700 tonnes of quinua. This would

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

26

almost double the current 938 tonnes per year production of quinua in Ecuador (FAO

Statistical Databases, 2001). These volumes are still significantly less than the volumes

produced (and traded) in Bolivia.

Radiofnica has brought in an organic certifier from Germany to assure their organic claims.

With this they aim to expand their market from the US into Europe, as well as trying other

crops such as the grain Amaranto and the nutritious lupin seed. Germany will only accept

organically certified quinua, especially as much of it is sold through health food stores.

The washing and cleaning of the grain is done by Radiofnica. Although they buy the

uncleaned quinua from farmers for US$ 0.63 per kilo, they will also purchase clean quinua

from farmers at a better price of US$ 0.73 a kilo. Radiofnicas cleaning of the quinua is a

matter of serious concern to environmental groups, however, who claim the effluent from the

processing plant is poisonous with saponins. It is an issue which is unlikely to go away, as

Radiofnica doubled the capacity of its processing plant in 2000.

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

27

8 Quinua and food security: The pitfalls of the export market

8.1 Were not talking about coffee and bananas

The export market for quinua is an alternative to a domestic market that, in the absence of

radical policy changes (see below) is unlikely to grow in the near future. However, we should

be under no illusions about the difficulties that smallholders face and the obstacles that they

need to overcome. Some of the challenges in terms of farmers having to contend with issues

such as quality of produce along with quantity and continuity of supply, are no different to

those faced by other farmers in the developing world e.g. coffee and banana producers

seeking niches in the fair trade and organic markets.

The major differences with quinua are that the crop is grown in extreme and adverse climatic

conditions, world markets are minute in comparison with chocolate, coffee and bananas; and

farmers traditional farming practices may prevent them from producing organic quinua,

particularly when quinua is grown in rotation with potatoes (see below). A final concern is

that unlike commodities such as coffee, quinua can be grown in a wide range of agro-

ecological conditions and thrives in parts of Europe and the US. This may undermine the

market, already very small, that exists for Andean-produced quinua.

8.2 Natural, social and human capital: Under-appreciated resources

Despite all the best efforts of Radiofnicas teams of dedicated extension agents, increasing

quinua production in line with predictions has not been easy in the Riobamba area. In

particular the weather has conspired to confound production in the 1999 harvest and again in

2000. Planting was late in some villages within Radiofnicas scheme in 1999, as the

extension teams did not manage to get out into the field early enough, and some villages were

slow to organise into groups. Climatic factors played a role in reducing yields in 2000: high

rainfall early in the growing cycle, frosts, little sun to help ripening, and strong winds may all

have had an effect. In 1999, one kilo of seed produced 30-40 kgs of quinua at harvest;

normally production of 100 kgs would be expected, rising to 200 kgs in some areas. In late

2000, as the quinua was maturing on the stalks, similar low yields were anticipated.

Radiofnicas extensionists are also learning as the project develops. They speculate about the

disappointing production figures: perhaps the quinua was sown too high up, it might have

been too exposed to the winds, perhaps the seed was poor quality or the soil too heavy,

perhaps a different variety of quioa should have been used. The extension agents advice to

local farmers is to plant further down the hill where there is less frost and sandier soil so less

problem with flooding. But the farmers are demoralised and organising them into a group for

planting quinua is difficult. Perhaps farmers expectations were raised too high at the

beginning of the programme.

Quinua and rural livelihoods in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador

Jon Hellin and Sophie Higman

28