Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Adagio Mesto of Brahms's Horn Trio, Op. 40: Romantic Distance, Longing, and Death

Загружено:

Imani MosleyОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Adagio Mesto of Brahms's Horn Trio, Op. 40: Romantic Distance, Longing, and Death

Загружено:

Imani MosleyАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Adagio mesto of Brahmss Horn Trio, op.

40: Romantic Distance, Longing, and Death

Imani Mosley

Introduction

The Horn Trio, op. 40 by Brahms is a piece that has not received a fair amount of discussion. For

hornists, its importance lies in the designation of the natural horn. For musicologists, it can be

found solely within the narrative of the nineteenth-century adagio and in the chamber works of

Brahms. However, at the heart of the work is a beguiling movement: the adagio mesto. The adagio

brings with it its own storied history but the term mesto is an elusive one. A term that became

familiar in Brtoks Sixth String Quartet, it is translated as sad but seems to represent something

more. The pairing of adagio and mesto alludes to something deeply sorrowful and painful and the

combination of the two has only happened once before.

For many, this very emotional and evocative tempo marking is reflective of what is believed to be

the locus of this piece -- the death of Brahmss mother Christiane. This idea comes from Max

Kalbecks biography of Brahms, a work that Brahms scholars are discovering is somewhat flawed.

Because this idea that the Horn Trio is about the death of Brahmss mother only comes from

Kalbeck, its veracity is less certain than previously believed. The lack of this hermeneutical aspect

allows the space to explore why Brahms would choose such a tempo marking. This paper will

explore various aspects of the work and the Adagio mesto movement specifically in order to shine

some light on why Brahms would have used the tempo marking adagio mesto for the third

movement of his Horn Trio.

1

The nineteenth-century adagio

There are many musico-historical reasons surrounding the choice of adagio as a tempo marking.

Notley remarks in Late-Nineteenth-Century Chamber Music and the Cult of the Classical Adagio

that the adagio was seen for many, especially Wagnerites, as a form unto itself that subsumes

sonata form and expresses something different entirely: the Adagio often seems to have

constituted an elevated genre unto itself, distinguished not only by its tempo but also by its

melodic style and quality of expression.

1

To write an adagio after Beethoven (as well as listen to

one) was an experience that, when done properly, could result in some type of musical revelation.

However, there was more to the writing of adagios in the late nineteenth-century than the

experiential. For many, the Classical Adagio stood as a marker for Germaness:

Nohl thus dwelt on the soulfulness of the late-eighteenth-century slow movement while

casually claiming a middle-European repertory as essential German, two intertwining modes

of reception in what appears to have been an intricately textured late-nineteenth-century

cult of the Classical Adagio.

2

Nothing is more a product of the German way than [the] Adagio the Adagio in German

sonata forms belongs to that which is most beautiful not merely in music but in art

altogether.

3

In this sense, the adagio moves far beyond a tempo marking. It becomes a concept, one that does

relate to a tempo (in this case, incredibly slow) but importantly, relates to a particular aesthetic: In

2

1

Notley

2

Notley, 33.

3

Ludwig Nohl as quoted by Notley, 33.

brief, the cult of the Adagio bore the traces of a later generations idealization of an earlier time,

coupled with a perception of its own shortcomings.

4

The importance of the Classical Adagio at this time cannot be overlooked; it was a theme discussed

not just by composers and musicians, but by writers and philosophers as well. German novelists

addressed the theme of the adagio as the aesthetic symbol of melancholy soliloquy and

sentimentally excessive feelings of love.

5

The soliloquy metaphor is an apt one, as the adagio

came to represent an expression of inwardness and internal struggle. These concepts were

translated musically in many ways. On a large-scale level, the adagio represents a form unto itself,

bent on working out singular, internal ideas, closed off to the other surrounding movements. On a

smaller scale, the ideas that are worked out within the adagio are of a melodic nature rather than a

structural. This focus on melody merged nicely for several musicians with that of Wagners

unendliche Melodie:

After Wagner introduced the phrase unendliche Melodie in the essay Zukunftsmusik in

1860, some of the musicians found that that concept conveyed their experience of the

Adagio both as an emotional and/or spiritual revelation -- the latter potentially equivalent to

the former -- and as a musical-textural type whose forms were to be subordinated to a more

fundamental, overriding melodic ideal.

6

3

4

Notley, 34.

5

Ruth E. Mller as quoted by Notley, 35.

6

Notley, 37.

For Ernst Kurth, the Adagio superseded form and structure through melody and theme, allowing

the movement, as it had for others, to become something entirely different rather than taking a new

approach to understanding the Classical Adagio.

Writing an adagio in the 1860s and later was to, in some ways, look back to the adagios of

Beethoven and Haydn and to respond to what seemed to be the loss of the form from the

repertory. Brahms was not the only composer to do so. Many of Bruckners works, notably his String

Quintet and Seventh Symphony, contained adagio movements. And for many opposed to Bruckner

and his compositional style, his adagios were his pieces only saving grace:

The conclusion seems inescapable: the Adagio was a genre unto itself, a special case that

transcended the usual standards of composition. Bruckners Adagio conveyed a sense of the

beyond even to the freethinking materialist Kalbeck.

7

Bruckner, as well as Wagner and Mahler, all approached this Adagio form, employing the same type

of compositional ideas and techniques: a focus on thematic generation and development of that

theme, less priority on overall structure, closed forms, and a somewhat insular nature. Richard

Giarusso points to what he calls a topical focus, the ability to hone in on a theme that will sustain

the interest of a listener through the lengths of an adagio movement.

8

These techniques are

employed by Brahms in the adagios of his First Maturity and would prove to be an attractive

4

7

Notley, 37.

8

Richard Giarusso, 197.

challenge to the young composer. This coupled with the prevailing aesthetic of the time

surrounding the Adagio would be good reasons for Brahms to try his hand at the form.

The adagio mesto of the Horn Trio is one of three adagios written during the period known as

Brahmss First Maturity, a term coined by Donald Tovey.

9

The three adagios (the others in the

Serenade no. 2 op. 16 and the Piano Quartet no. 2 op. 26) represent a break with the adagios

Brahms had previously written:

The adagios in the Second Serenade, the A-Major Piano Quartet (op. 26) and the Horn Trio

(op. 40) sound not only mature but also highly individualized. With their characteristic

concern to examining broad architecture, musicologists have stressed Brahmss innovative

approach to large-scale form in these sightly later slow movements.

10

Notley, however, states that the Adagios of this period may have been motivated more by aesthetic

choices than formal ones:

This melody-centered principle raises the question of whether the large-scale forma novelty

of these Adagios from Brahmss first maturity (Toveys designation for this period) might

be secondary, a complementary by-product of more primary melodic concerns.

11

5

9

Donald Tovey, Brahmss Chamber Music, Essays and Lectures in Music (London, 1949); 243.

10

Notley, 45.

11

Notley, 45.

Regardless of their motivation, these three adagios represent a break from Brahmss previously

written adagio movements.

12

The Adagios focus on thematic generation and development make it a perfect place to work out an

idea, especially one that signifies something internal. If it is to be believed that the Horn Trio,

especially the Adagio mesto, represents Brahmss grief over the loss of his mother, an adagio

movement would be an ideal place to do so. Kalbecks assertion that the theme of the Adagio

mesto (which retroactively becomes the theme of the entire piece) comes from a folksong that his

mother sang to him as a child ties together these separate aspects of the Adagio phenomenon.

This hermeneutical reading of the Adagio becomes problematic when Kalbecks theory is examined

which I will discuss further.

The use of mesto

The Grove Dictionary of Music defines mesto as sad, sorrowful, and dejected, terms that

dont seem to necessarily separate mesto from other sad tempo markings. The definition goes on

to discuss the terms history, noting that it was first used by Zarlino, Bottazzi, and Monteverdi in his Il

ritorno dUlisse (Finita sinfonia in tempo allegro, si inomincia la seguente mesta, alla bassa sin che

Penelope sar gionta in scena per dar principio al canto).

13

There are sparing uses of it throughout

6

12

It is important to note that at this time, the distinction between adagio and andante was not very clear. While the

adagios of the first maturity definitely stand apart due to their size, Brahmss previously written adagios and

andantes do not have such a distinction. Also, as tempo markings, they both seemed to occupy the same speed

range.

13

David Fallows. "Mesto." Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed December

8, 2012, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/18501.

the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in varying forms (as an adjective and as an adverb) but

nothing that seems to be connected with an extramusical event.

The two examples of the use of mesto before Brahms were both employed by Beethoven, in his

Piano Sonata no. 7 op. 10 in D major (largo e mesto) and the String Quartet no. 7, op. 59, no. 1

Rasumovsky (adagio molto e mesto). In Maynard Solomons Beethoven, Freemasonry, and the

Tagebuch of 1812-1818, he discusses the text written at the bottom of the sketch for the adagio

movement of the String Quartet no. 7, a weeping willow or acacia tree on my brothers grave

which while believed to be a reference to freemasonry, is most likely a note referring to the death of

one of his brothers.

14

Note here the use of both adagio and mesto (adagio molto) to imply the

deepest, most doleful feelings. Between Beethoven and Brahms, mesto rarely appears as a tempo

marking. Ten years after the composition of the Horn Trio, Dvo!k used adagio molto e mesto in his

Trio, op. 21 for Violin, Cello, and Piano in B-flat major. Most notably, Brtok used mesto as a tempo

marking throughout his Sixth String Quartet, a tempo marking he added after the death of his

mother.

While it can not be said with any fair amount of certainty, the connection between mesto and

feelings of deep sadness and loss is a vague yet present one. The choice of mesto as a tempo

marking could further the claim that the Adagio mesto movement is one that signifies the death of

Brahmss mother but it is not a claim that would be able to stand alone.

7

14

Maynard Solomon. "Beethoven, Freemasonry, and the Tagebuch of 1812-1818." Beethoven Forum 8 (2000): 125.

Hermeneutics and the Horn Trio

In Kalbecks biography of Brahms, he attributes the genesis of the work, particularly the Adagio

mesto, to the death of Brahmss mother, Christiane in 1864.

15

He bolsters this claim by citing two

musical sources that he believed were the basis for the piece: the folksong Dort in den Weiden

steht ein Haus and the chorale Wer nur den lieben Gott lt walten. According to Kalbeck, these

melodies can be heard at the end of the Adagio mesto movement and at the beginning of the

Finale movement. He devotes a large section explaining aspects of the piece and why Brahms

chose them which revolves around the locus of his childhood: the two songs were songs Brahms

would have learned as a child and that his mother probably would have known and the instruments

that make up the trio are the instruments of Brahmss childhood. Also, the best way to mourn and

commemorate (according to Kalbeck) the loss of ones mother is to use the songs and sound of the

forest (Wald) which comes from the horn. He also notes that the moment of mourning occurs in the

adagio mesto and that this term is the way in which listeners can grasp Brahmss state of mind.

16

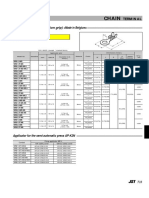

The songs that Kalbeck attributes to the adagio mesto and finale movements of the trio, however,

are somewhat flimsy. His analysis of how these thematic elements work throughout the trio is

correct -- the theme appears in its most complete form at the end of the Adagio and is transformed

at the beginning of the finale -- but the citations seem to be misguided. Examples 1, 2, and 3 show

8

15

16

Kalbeck, . Die eigentliche Totenklage tnt uns aus dem Adagio entgegen, das besonders mit mesto

bezeichnet ist. Auf diese einzige Andeutung beschrnkt sich, was der Komponist der Welt von seinem

Gemtszustande persnlich verraten wollte.

a. Mm. 59-61

the musical times Spring 2011 21

2. Max Kalbeck: Johannes

Brahms (second edition,

Berlin, 1908), vol.2, pp.182

84.

3. Deutsche Volkslieder mit

ihrem Original-Weisen,

compiled by Professor

Dr. Mamann, AW von

Zuccalmaglio & August

Kretzschmer (Berlin,

1838; repr. Hildesheim,

1969). Brahms refers

to his possession of the

anthology in his letter to

Clara Schumann of 25 June

1858. See, e.g., Richard

Litterscheid: Johannes

Brahms in seinen Schriften und

Briefen (Berlin, 1943), p.161.

recognisable in the second half-phrase of the second movement, as shown

by the Xs in ex.4. And the haunting opening theme of the rst movement

can easily be seen as a major-key adumbration of the second element, as

shown by the Xs in ex.5. (The fth BbF is associated with the minor sixth,

Gb, a bit later, in bars 1620.)

Given the intensity with which these themes are developed in their

respective movements, it is not a great exaggeration to say that the majority

of the motivic material of the entire op.40 Trio is derived from the theme that

is heard in its clearest and simplest form at the beginning of the Finale.

Max Kalbeck, Brahmss close friend and early biographer, asserted that

the theme of the op.40 Finale was derived from the German folksong Dort

in den Weiden steht ein Haus, whose beginning is given as ex.6.

2

It does

not require remarkable musical insight, however, to see that the folksong

and the theme do not match up particularly well. One is major, the other

minor. And the highly characteristic omission of the fourth scale-degree,

suggesting a pentatonic collection, and the prompt return to the tonic in

Brahmss theme are not found in this folksong. And from the other side, the

neighbour-note motion between D and Eb that avour this folksong is not

at all present in Brahmss Finale theme.

Even less convincing is Kalbecks reference to the chorale Wer nur den

lieben Gott lt walten (ex.7) as a source of Brahmss melodic material in

op.40. Brahms did know Dort in den Weiden steht ein Haus: it is found in

the anthology of German folksongs compiled by Mamann, Zuccalmaglio,

and Kretzschmer that he owned,

3

and he arranged the song at least four

_

Allegro

_

,

,

,

p

,

x

,

x

,

x

,

x

,

x

,

x

(1)

,

x

,

x

,

_

_

Andante

_

,

,

,

x

p dolce espress.

,

x

,

,

,

x x

,

,

,

(2)

,

,

,

x

,

,

,

,

,

,

x x

,

,

,

x

,

_

_ _

,

,

Dort in

,

den

,

Wei

,

,

den

,

,

- steht

,

,

ein Haus,

,

,

,

steht

,

,

ein Haus,

,

,

,

_

,

,

steht

,

,

ein

,

,

Haus,

,

,

da

,

,

schaut

,

die

,

Magd

,

,

zum

,

,

Fen

,

,

ster

,

,

- nhaus,

,

,

zum Fen

,

_ ,

ster

,

- nhaus!

,

Ex.4

Ex.5

Ex.6

Thematic transformation, folksong and nostalgia in Brahmss Horn Trio op.40 22

4. Twice for voice and

pianoforte (WoO32, no.12;

WoO33, no.31), and once

each for chorus SATB

(WoO35, no.8) and SSAA

(WoO38, no.3).

5. Deutsche Volkslieder, vol.2,

p.540, no.310.

times.

4

Paging further through the Mamann-Zuccalmaglio-Kretzschmer

anthology, however, one eventually comes to another folksong that is an

exact match and must have been Brahmss source for the rst theme of

the Finale: Es soll sich ja keiner mit der Liebe abgeben, which is given in its

entirety as ex.8.

5

What is striking here, of course, is that the opening of Brahmss Finale

is identical to the rst half of the folksong in interval structure, rhythm,

metrical orientation, and even note repetition. Only the passing note at the

end of bar 2 in the folksong is omitted in Brahmss theme. Furthermore,

the downward movement through scale degrees 876, which sets up the

second element of Brahmss theme, is found at the beginning of the second

half of the folksong (bars 56). I think that there can be no doubt that Es soll

sich ja keiner mit der Liebe abgeben was the source of Brahmss Finale theme

and, thus, of most of the motivic material in his Horn Trio op.40

And what of the words to this folksong? Here is my translation:

No one should have anything to do with love.

It has brought many a ne lad to kill himself.

Today my buxom wench promised me her love.

I accused her! I accused her!

In a comic vein, it sounds quite a bit like many remarks about love and

marriage made by Brahms, the conrmed bachelor, up to and including his

famous frei aber froh.

Kalbeck wished to interpret Brahmss purported, but now disproven,

quotation of Dort in den Weiden steht ein Haus with a reference to the words

of that song, believing that, by alluding to the melody, Brahms referred,

with melancholy nostalgia, to the house of his childhood and his associated

memories of his mother. In this way, Kalbeck made the op.40 Trio into an

expression of Brahmss deep sorrow at his mothers death, which occurred

shortly before the completion of the work. The high spirits of the Finale,

alone, should have inspired scepticism about this hypothesis, but most

_

,

Wer

3

,

nur

,

den

,

lie

,

ben

,

- Gott

,

ltt

,

wal

,

ten

,

-

Es

Sie

,

soll

brcht

,

sich

ja

,

ja

so

,

kei

man

,

ner

che

,

-

-

mit

sch

,

,

der

ne -

Lie

Ker

,

,

,

be

le

,

-

-

ab

ums

,

ge

Le

,

- ben,

ben.

,

-

-

Heut

,

hat

,

mir

,

mein

,

_

Trut

,

schel

,

- die

,

Lie

,

be

,

- ver

,

sat,

,

- ich hab

,

,

,

sie

,

ver

,

klat,

,

- ich hab

,

,

,

sie

,

ver

,

klat.

,

-

Ex.7

Ex.8

Example 1: Brahms, Horn Trio in E-flat, op. 40, Adagio mesto main motive

Example 2: Dort in den Weiden steht ein haus

Example 3: Wer nur dein lieben Gott lt walten

the motive in the Adagio movement compared to both quotations that Kalbeck claims to be the

source material. Kalbeck also states in the biography that these themes can be found in others of

Brahmss work (Six Lieder, op. 94, no. 4 Dort in den Weiden) and also in the second movement

of Mendelssohns String Quartet, op. 12 in E-flat major (1829). Surprisingly, Kalbeck cites these

other examples as a way to bolster his argument about the underlying connective tissue of these

themes, as if to say that their appearance in these other works proves that Brahms used them in the

Horn Trio and used them to represent the allusions that Kalbeck suggests.

9

Thematic transformation, folksong and nostalgia in Brahmss Horn Trio op.40 22

4. Twice for voice and

pianoforte (WoO32, no.12;

WoO33, no.31), and once

each for chorus SATB

(WoO35, no.8) and SSAA

(WoO38, no.3).

5. Deutsche Volkslieder, vol.2,

p.540, no.310.

times.

4

Paging further through the Mamann-Zuccalmaglio-Kretzschmer

anthology, however, one eventually comes to another folksong that is an

exact match and must have been Brahmss source for the rst theme of

the Finale: Es soll sich ja keiner mit der Liebe abgeben, which is given in its

entirety as ex.8.

5

What is striking here, of course, is that the opening of Brahmss Finale

is identical to the rst half of the folksong in interval structure, rhythm,

metrical orientation, and even note repetition. Only the passing note at the

end of bar 2 in the folksong is omitted in Brahmss theme. Furthermore,

the downward movement through scale degrees 876, which sets up the

second element of Brahmss theme, is found at the beginning of the second

half of the folksong (bars 56). I think that there can be no doubt that Es soll

sich ja keiner mit der Liebe abgeben was the source of Brahmss Finale theme

and, thus, of most of the motivic material in his Horn Trio op.40

And what of the words to this folksong? Here is my translation:

No one should have anything to do with love.

It has brought many a ne lad to kill himself.

Today my buxom wench promised me her love.

I accused her! I accused her!

In a comic vein, it sounds quite a bit like many remarks about love and

marriage made by Brahms, the conrmed bachelor, up to and including his

famous frei aber froh.

Kalbeck wished to interpret Brahmss purported, but now disproven,

quotation of Dort in den Weiden steht ein Haus with a reference to the words

of that song, believing that, by alluding to the melody, Brahms referred,

with melancholy nostalgia, to the house of his childhood and his associated

memories of his mother. In this way, Kalbeck made the op.40 Trio into an

expression of Brahmss deep sorrow at his mothers death, which occurred

shortly before the completion of the work. The high spirits of the Finale,

alone, should have inspired scepticism about this hypothesis, but most

_

,

Wer

3

,

nur

,

den

,

lie

,

ben

,

- Gott

,

ltt

,

wal

,

ten

,

-

Es

Sie

,

soll

brcht

,

sich

ja

,

ja

so

,

kei

man

,

ner

che

,

-

-

mit

sch

,

,

der

ne -

Lie

Ker

,

,

,

be

le

,

-

-

ab

ums

,

ge

Le

,

- ben,

ben.

,

-

-

Heut

,

hat

,

mir

,

mein

,

_

Trut

,

schel

,

- die

,

Lie

,

be

,

- ver

,

sat,

,

- ich hab

,

,

,

sie

,

ver

,

klat,

,

- ich hab

,

,

,

sie

,

ver

,

klat.

,

-

Ex.7

Ex.8

Example 4: Es soll sich ja keiner mit der Liebe abgeben

However, John Walter Hill in Thematic transformation, folksong and nostalgia in Brahmss Horn Trio

op. 40 points to another song as the source for these motives, the folk song Es soll sich ja keiner

mit der Liebe abgeben.

17

Example 4 shows the excerpt of the folksong that Hill believes to be the

source material for the Trios main thematic motive. Just as the Kalbeck themes held extramusical

meaning, so they do for Hill. He believes that it represents the breakup of the relationship between

Brahms and Agathe von Siebold in 1859. He makes the jump that many years later, this would still

be with him which at first seemed too much of a stretch. However, the recent discovery of a piano

work now entitled Albumblatt which contains the molto meno allegro theme from the second

movement of the Horn Trio makes this seem plausible. The piece was written in Gttingen in 1853

and it was also in Gttingen a few years later that Brahms would meet and fall in love with Agathe,

signifying that all of the concepts of the piece may have been place for quite some time. Hill

furthers his claim that the Horn Trio is about Agathe rather than Christiane by looking at the text of

all three quotations, citing that only one of them has thematically appropriate text:

Kalbeck wished to interpret Brahmss purported, but now disproven, quotation of Dort in

den Weiden steht ein Haus with a reference to the words of that song, believing that, by

alluding to the melody, Brahms referred, with melancholy nostalgia, to the house of his

10

17

John Walter Hill, Thematic transformation, folksong and nostalgia in Brahmss Horn Trio op. 40. Musical Times,

22.

childhood and his associated memories of his mother. In this way, Kalbeck made the op. 40

Trio in an expression of Brahmss deeps sorrow at his mothers death with occurred shortly

before the completion of the work But now that Es soll sich ja keiner mit der Liebe

abgeben, with its comically misogynist words, has been brought forward, we certainly must

dispense with the myth of this Trio as homage to the composers late mother.

18

However, this seems to be circular logic on the part of Hill. This claim that the text reinforces the

idea of Es soll sich ja keiner mit der Liebe abgeben as source material for the motive forces the

conclusion that this folksong is indeed the correct quotation. And while there is a convincing

argument to be made that this is the case, it seems that here, Hill is putting the cart before the

horse.

For Hill, the trio tells the story of love lost and accepted with the adagio at the end of the

relationship. He also connects the Second String Sextet to the Horn Trio because it contains the

cryptogram a-g-a-d-h-e to represent von Siebold and the two should be thought of as

complements. How does one reconcile this with what the terms adagio and mesto signify? Beller-

McKenna touches upon this in Distance and Disembodiment: Harps, Horns, and the Requiem

Idea in Schumann and Brahms, a review of Daverios Crossing Paths: Schubert, Schumann, and

Brahms.

19

For Beller-McKenna, the adagio is purely funereal rather than something that represents

the Requiem Idea which involves a consolation or resolution after grief: Thus it might serve our

present purposes by providing an example whereby we can distinguish between the merely

11

18

Hill, 22.

19

Daniel Beller-McKenna "Distance and Disembodiment: Harps, Horns, and the Requiem Idea in Schumann and

Brahms." The Journal of Musicology, 22, no. 1 (2005)

mournful and the Schumann/Brahms Requiem Idea.

20

Interestingly, Beller-McKenna does not

mention the harp-like passages at the beginning of the adagio mesto, a figure that fits well into the

Requiem Idea. He also does not note the relationship Kalbeck makes between this piece and the

Four Songs for Womens Chorus, Two Horns and Harp, op. 17:

Nicht nur in der Tonart (es-moll) berhrt sich das Adagio mit der Heldenklage des letzten

Intermezzos aus den Klavierstcken op. 118, es sind dieselben schauerlichen, mit dem

Geisterreich kommunizierenden Klnge, und die gebrochenen Akkorde des arpeggierenden

Klaviers erinnern dabei an die drei Lieder fr Frauenchor mit Hrnern und Harfe op. 17, um

Ossiansche und Eichendorffsche Stimmungen hervorzuzaubern.

21

He does however mention the Intermezzo op. 118 no. 6 which is also marked mesto and is in E-flat

minor, a key Beller-McKenna says becomes associated with death for Brahms in later works:

One might even speak of an E-flat minor mood in a cluster of pieces from op. 40 onward,

works that deal with death in its most purely romantic sense, as an unattainable respite from

the sultry languor of life.

22

But for Beller-Mckenna, neither the Adagio mesto nor the Intermezzo move beyond their mourning

and grief:

12

20

Ibid, 84.

21

Kalbeck, . Notley also discusses the opening of the Adagio mesto movement, comparing the arpeggios in the

piano to that of a small folk harp.

22

Beller-McKenna, . Interestingly, Brahmss Intermezzo, op. 117 no. 1 is in the key of E-flat major and was prefaced

by a poem collected by Johann Gottfried von Herder that notes a mother comforting her child over the

abandonment by his father. While this is not as strong of a connection to the feeling of loss and death exhibited by

the E-flat minor works, it is an interesting parallel.

But these works (including Wagners) all convey redemption through some transcendence of

the minor mode. The same can not be said for the third movement of the Horn Trio or the

Intermezzo, op. 118 no. 6: Neither piece uses the obscure key of E-flat minor as a foil or a

departure point from which to transcend its grief Brahms is even less willing to let go of

grief in the Adagio mesto of the Horn Trio Thus for all its somber tone, the Horn Trio

does not partake of the Requiem Idea.

23

And while Beller-McKenna doesnt say so in regards to the Horn Trio, he does talk about the piece

that does commemorate Christianes death: the German Requiem. This piece, for Beller-McKenna

and Daverio, represents the ideal Brahmsian form that would deal with death, loss, and grief. Why

would Brahms commemorate his mother so well in the German Requiem (written in the same year

as the Horn Trio) and so ineffectively in the Horn Trio?

Beller-McKenna goes on, analyzing various aspects of the trio from idea of Romantic distance

represented by the horn itself to the manipulation of the main motivic theme into a fugue. Overall,

Beller-McKenna places an emphasis on stagnation, a concept that directly conflicts with the

Requiem Idea. Notley, however, discusses this very idea of stagnation in regards to the classical

adagio. The adagio, as its own form within a larger structure, focuses more on melody and the

development of a singular idea. And while there may be thematic continuity, harmonic and

structural continuity is not as necessary:

Monothematicism -- or at least the unmistakable reappearance of motives from the opening

in other themes -- seems to have had a higher value in Adagios than in other movement

13

23

Beller-McKenna, 84.

types, an apparent consequence of conceptualizing an Adagio as the generation of one

melody representing a single inner experience.

24

This type of singular focus applies to harmony as well. While Beller-McKenna sees Brahmss inability

to transform or move beyond the key of E-flat minor, Notley sees it as another example of the

Adagio style. Brahms explores B-flat Phrygian in the fugato section of the movement (a section that

Beller-McKenna decries) while avoiding any motion to a dominant key. His use of 6/4 chords and

evasive cadences are, for Notley, central to the Adagio aesthetic.

25

The aspects of the Horn Trios

Adagio mesto movement that Beller-McKenna mentions seem to be the ones that best represent

the late-nineteenth-century Classical Adagio style, something to which Beller-McKenna makes no

mention. Is it possible, then, that this bolsters Hills claim that the Horn Trio, especially the Adagio

mesto, is not representative of the type of loss and grief found in pieces that contain the Requiem

Idea and that, in fact, it is the grief over the loss of a relationship rather than a death? These various

theories do not seem to intersect with each other specifically. They do, however, raise some

suspicion that Kalbecks analysis of the piece was misguided.

The Romantic horn and the Waldhorn

The natural horn played a large part in German Romantic literature as a representative of many

types of distance: temporal, physical, and spiritual. Temporal distance can reference a horn call

coming from far away or evoking a space between past and present while spiritual distance, for lack

of a better work, can signify the space between the living and the dead. Distance can also represent

14

24

Notley, 57.

25

Notley, 55.

a wandering or listlessness, usually a wanderer separated by time and or space. This figures into the

Romantic notion of Sehnsucht, one that is often related to the horn in several ways. Enclosed in this

is the idea of the horn as evocative of the forest (Wald) which also carries many signifiers in German

Romantic literature, poetry, and philosophy. Eichendorff wrote often of the Waldhorn in relation to

the German forest and it was a popular German Romantic trope. Many believe that these signifiers

were the main reason that Brahms specified Waldhorn (natural horn) instead of valved horn.

Other Romantic composers use the horn (or textual imagery of the horn) to represent these varying

types of distance. Schumann discusses spiritual distance in his 1840 review of Schuberts Great

Symphony, D. 944:

There is a passage in it where the horn is calling as if from afar; this appears to me as if it

had come from another sphere. Here everyone is listening, as if a heavenly guest were

creeping through the orchestra.

26

In a footnote, Berthold Hoeckner compares Schumanns description to other Romantic clichs found

in literature, specifically Ludwig Tiecks Franz Sternbalds Wanderungen which references the sound

of distant horns emerging from deep within the forest, playing with the listeners idea of time,

distance, and reality.

27

Similarly, the horn evokes the mystery of the German forest in Webers Der

Freischtz. In Schuberts Die Post from Winterreise, horn call figures are simulated in the piano to

15

26

Schumann as quoted by Berthold Hoeckner, Schumann and Romantic and Distance. Journal of the American

Musicological Society, 50, no. 1 (1997); 74.

27

Suddenly they heard from the distance the touching play of intricate horns out of the forest; standing still they

strained to hear whether it was imagination or reality; but a melodic singing flowed toward them through the trees

like a rippling rill, and Franz thought that the spirit world had suddenly opened up, that perhaps, without knowing it,

they had found the great magic word (ed. Alfred Anger [Stuttgart: Reclam, 1966], 221-22).

evoke the Posthorn, another type of natural horn. However, this horn call represents the distance

between the Wanderer and his beloved, a distance that is not bridged by the arrival of a letter. Just

as the Classical Adagio has both literary and musical functions, so does the natural horn.

In John Ericsons article Brahms and the Orchestral Horn, he states that in the Horn Trio this use

of the natural horn was at least in part to create a nostalgic mood, retrospective, one looking

toward the past and into memories.

28

It was not necessary for Brahms to ask for a natural horn rather than a valved one; the trio was

composed in 1865, the same year that Wagner composed Tristan und Isolde which calls for valved

horn. At the time that Brahms was composing the Horn Trio, hornists favored the valved horn over

the natural horn for its ease and flexibility and the instrument was popular and established enough

that it wouldnt have been necessary to write for natural horn. In Eva Heaters article, Why Did

Brahms Write His E-Flat Trio, Op. 40, for Natural Horn?, she discusses the sonic implications of the

natural horn over a valved one.

29

The techniques involved with a natural horn produce a very

distinct sound, one very different from its valved cousin. In a letter published in the Beilage zur

Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung, Brahms wrote the following about the sound of the natural horn:

[] if the performer is not obliged by the stopped notes to play softly, the piano and violin

are not obliged to adapt themselves to him, and the tone is rough from the beginning.

30

16

28

John Ericson, Brahms and the Orchestral Horn. http://www.public.asu.edu/~jqerics/brahms-natural-horn.html,

2012.

29

Eva Heater, Why Did Brahms Write His E-Flat Trio, Op. 40, for Natural Horn? American Brahms Society

Newsletter, 19, 1. 2001, 2.

30

Selmar Bagge. "Important review of Johannes Brahms Trio for violin, horn and piano, op. 40." In Allgemeine

musikalische Zeitung 2 (1867): 15-17, 24-25.

The timbre is quieter and more mellow but, more specifically, produces a different timbre in

different key areas. Heater explains these technical aspects well, citing a change in timbre in the

molto meno allegro theme in the second movement but Heaters main focus is on that of the

Adagio mesto movement. For Heater, the way that the natural horn handles the key of E-flat minor

is crucial and influences the way listeners might hear the movement:

Again in the third movement (adagio mesto), the selection of key offered Brahms an

expressive opportunity, for choosing E-flat minor meant that the horn has many partially-

stopped notes, creating an effect in keeping with the somber emotional quality of the

movement as a whole Measure 83 in the third movement, if played on a natural horn,

produces a unique and stunning effect: the held sforzando E-flat in the horn part (concert G-

flat), which must be played on the natural horn with the hand partially stopping the bell,

creates a stinging sound This held sforzando on the climatic plagal cadence decays

rapidly to a piano for the final three measures of the movement. The unusual impact of this

passage cannot be achieved when the note is played on a valve horn, for without the hand

technique, all of the notes sound open. This was a deliberate expressive effect on Brahmss

part.

31

Notley also speaks about this plagal cadence, noting that only a performance on natural horn that

Brahms stipulated can produce the full effect here.

32

For Heater and Notley, this aspect is

important, both sonically and harmonically. This sforzando highlights the plagal cadence in a

movement filled with previously evaded cadences. Notley discusses the importance of this cadence

in her paper Plagal Harmony as Other: Asymmetrical Dualism and Instrumental Music by Brahms.

17

31

Heater, 2.

32

Notley, 55. Notley also discusses the timbral quality of the stopped tones in Plagal Harmony as Other:

Asymmetrical Dualism and Instrumental Music by Brahms.

This plagal harmony that acts as the underpinning of the movement is highlighted by the sound of

the natural horn. But what was Heater referring to when she mentioned the somber emotional

quality of E-flat minor played on a natural horn? In reading various writings on natural horn, it

seems that this quality referred to by Heater is one that is understood when heard. Rather than

having a specific cultural or historical reference, it lies within the instruments timbre, therefore

making it difficult to describe. However, others have pointed to the timbre as reflecting some notion

of German Romanticism:

Aside from its suggestion of the Wald, the chase and the mystical significance attached

by Tieck and other Romanticists to Waldeinsamkeit, the horn seems to me to owe its

popularity, at least in part, to its tone-color.

33

It seems clear that whatever this tone color signified it was something that Brahms actively sought

out for both sonic and representational reasons.

The choice to use natural horn was not solely representational. As mentioned earlier, the use of

natural horn helped to cement a harmonically and formally unified structure. Both Michael

Musgrave and Malcolm MacDonald write that Brahms was constricted to a particular harmonic

series by specifying that a natural horn be used but as Joshua Garrett points out in his dissertation

Brahmss Horn Trio: Background and Analysis for Performers, this is not the case:

What is interesting about the use of hand horn in the Horn Trio is, with few exceptions, the

use of the stopped notes and not the use of the open notes. A piece with no stopped

18

33

Lambert Shears, The Romantic Waldhornlied, Monatshefte fr Deutschen Unterricht, 27, no. 1 (1935); 310.

tones, as MacDonald and Musgrave mistakenly suggest the trio is, would thus lack exactly

the quality that Brahms sought out.

34

Garrett goes on to discuss the use of E-flat (both major and minor) as a the focal point of the piece,

echoing statements by Notley about the form and structure of each movement and of the piece as

a whole:

Another possible reason for the retention of E-flat throughout is that Brahms wanted to

intensify the feeling of harmonic departure and return. As written, the tonic in each

movement is reinforced by the open tones of the horn. The farther away the music gets

from the tonic, the more chord tones are stopped, and the closer the music is to the tonic,

the more chord tones are open. By keeping the same tonic for each movement, and by

consistently reinforcing this tonic with the open tones of the horn, the key structure and

form are particularly highlighted, and the sense of harmonic return to the home key is

particularly strong.

35

The natural horns ability to highlight key harmonic and structural moments, especially in the adagio

movement, seems to play a large part in an understanding of the piece. This knowledge of the horn

would have been completely within Brahmss purview: he studied natural horn as a child and his

father was a professional hornist. Kalbeck uses this knowledge as a connection to Brahmss youth,

furthering the idea that this piece represents longing and reminiscence but it seems more likely that

Brahms was just drawing on his own experience to evoke a particular idea. This does not mean that

the horns Romantic signifiers are not bound up within the construction of this piece -- I believe that

19

34

Joshua Garrett, Brahmss Horn Trio: Background and Analysis for Performers. 1998, 33.

35

Garrett, 33.

they are -- however, it is more likely that they are representative of a particular aesthetic at the time

rather than specifically about the death of Brahmss mother. Those signifiers are intertwined with the

actual sound of the natural horn (horn call fifths, dynamics, and timbre) and I think that they are

related in this piece in a very important way. Brahmss insistence on the use of a natural horn over a

valved horn -- he asked for hornists to play on natural horn for weeks before the performance to

become accustomed to it and always used natural horn whenever he performed the work -- seems

to signify more than just a composers prerogative.

Conclusion

Revisiting Kalbecks writing about the Horn Trio reveals some holes in his argument. The passage on

the Horn Trio in his biography of Brahms is surprisingly long, given the status the piece has in

Brahmss oeuvre. Also surprising is the depth in which Kalbeck explains how the piece came about.

While it cant be proven that any of the reasons given by Kalbeck are indeed correct, it does lead

one to believe that there is something there behind this work, something more than just the

motivation of the times to write large-scale adagio movements.

This paper, however, was never meant to be a probing of Brahmss life outside of this work in order

to alter the way we hear or understand the piece. I believe that no matter what the reason (if there

is one) that the sentiment is achieved. This is mostly accomplished by Brahmss compositional

prowess. An overall feeling of mourning and sadness seems to be built into the work, especially

played on natural horn. What this paper tried to achieve was an understanding of how the culture

surrounding Brahms at the time (as well as aspects of his own life) could have led to such a choice.

20

The writing of an adagio movement is fairly straightforward but its pairing with mesto colors the

adagio in a way that possibly no other tempo marking could. All of the individual aspects of the

piece from the choice of natural horn, to the use of mesto, to the adagio itself lend themselves to

some sort of tantalizing hermeneutical reading. And whether a definitive answer will ever arise is

unseen but it does shed some light on the complexity of even some of Brahmss lesser-known

works.

21

Bibliography

Bagge, Selmar. "Important review of Johannes Brahms Trio for violin, horn and piano, op.

40." In Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 2 (1867): 15-17, 24-25.

Beller-McKenna, Daniel. "Distance and Disembodiment: Harps, Horns, and the Requiem Idea

in Schumann and Brahms." The Journal of Musicology, 22, no. 1 (2005): 47-89.

Botstein, Leon. The Compleat Brahms: A Guide to the Musical Works of Johannes Brahms.

W.W. Norton and Company: New York, NY. 1999.

Brinkmann, Reinhold. Late Idyll: The Second Symphony of Johannes Brahms. Harvard

University Press: Cambridge, MA. 1995.

Brodbeck, David. "Medium and meaning: new aspects of the chamber music." The

Cambridge Companion to Brahms. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. 1999.

Garrett, Joshua, 1998. Brahmss Horn Trio: Background and Analysis for

Performers. [Doctor of Musical Arts], Juilliard.

Giarusso, Richard, 2007. Dramatic Slowness: Adagio Rhetoric in Late Nineteenth-Century

Austro-German Music. [Doctor of Philosophy], Harvard University.

Heater, Eva M. "Why Did Brahms Write his E-flat Trio, op. 40 for Natural Horn?" American

Brahms Society Newsletter (2001): 105-107.

Hill, John Walter. "Thematic transformation, folksong and nostalgia in Brahms's Horn Trio op.

40." Musical Times, 152 (2011): 10-24.

Hoeckner, Berthold. "Schumann and Romantic Distance." The Journal of the American

Musicological Society 50, no. 1 (1997): 55-132.

Kalbeck, Max. Johannes Brahms 1833-1894. Deutsche Brahms-Gesellschaft: Hamburg, 1914.

MacAuslan, John. "'The Artist in Love' In Brahms's Life and in his 'German Folksongs'." Music

and Letters 88, no. 1 (2007): 78-106.

MacDonald, Malcolm. Brahms. New York: Schirmer Books, 1990.

Musgrave, Michael. The Music of Brahms. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985.

Notley, Margaret. "Late-Nineteenth-Century Chamber Music and the Cult of the Classical

Adagio." 19th-Century Music, 23, no. 1 (1999): 33-61.

22

------------------------- Lateness and Brahms: Music and Culture in the Twilight of Viennese

Liberalism. Oxford University Press: Oxford. 2007.

Sisman, Elaine. "Brahms's Slow Movements: Reinventing the 'Closed' Forms." Brahms

Studies: Analytical and Historical Perspectives. Clarendon Press: Oxford. 1990.

Smith, Peter H. "Brahms and the Shifting Barline: Metric Displacement and Formal Process in

the Trios with Wind Instruments." Brahms Studies, vo. 3. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln.

2001

Solomon, Maynard. "Beethoven, Freemasonry, and the Tagebuch of 1812-1818." Beethoven

Forum 8 (2000): 101-146.

23

Вам также может понравиться

- Edward Elgar - Variations on an Original Theme 'Enigma' Op.36 - A Full ScoreОт EverandEdward Elgar - Variations on an Original Theme 'Enigma' Op.36 - A Full ScoreОценок пока нет

- Frippery #9Документ1 страницаFrippery #9Patxi GarciaОценок пока нет

- Vincent PersichettiДокумент4 страницыVincent Persichettijoao famaОценок пока нет

- Natural HornДокумент3 страницыNatural HornroroОценок пока нет

- A Study of French Horn Harmonics PDFДокумент78 страницA Study of French Horn Harmonics PDFTiago OliveiraОценок пока нет

- AriasДокумент2 страницыAriasapi-331053430Оценок пока нет

- Fennell v. First Step Designs, 1st Cir. (1996)Документ80 страницFennell v. First Step Designs, 1st Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Concerto For Tuba and OrchestraДокумент2 страницыConcerto For Tuba and Orchestraapi-425284294Оценок пока нет

- "Buddah Lee" - Flexibility and Clef ReadingДокумент4 страницы"Buddah Lee" - Flexibility and Clef ReadingAlvaro Suarez VazquezОценок пока нет

- The Colors of The Horn in Ravel's Pavane For A Dead PrincessДокумент8 страницThe Colors of The Horn in Ravel's Pavane For A Dead Princessjesscl07100% (1)

- Trombón 2Документ5 страницTrombón 2alejotrmb100% (1)

- Unit Study First Suite in EbДокумент8 страницUnit Study First Suite in Ebapi-357472068Оценок пока нет

- PDF DatastreamДокумент34 страницыPDF Datastreambluedragons199260Оценок пока нет

- Oblivion Euphonium PDFДокумент2 страницыOblivion Euphonium PDFNate HОценок пока нет

- Denis Wick PDFДокумент2 страницыDenis Wick PDFvicentikooОценок пока нет

- Wind HagerДокумент38 страницWind Hagertitov33Оценок пока нет

- Tuba Quartet InfoДокумент1 страницаTuba Quartet InfoLeung Lok WaiОценок пока нет

- Karel Husa - Al Fresco PresentationДокумент18 страницKarel Husa - Al Fresco PresentationAndrew JanesОценок пока нет

- Second Trumpet Repertoire ListДокумент2 страницыSecond Trumpet Repertoire ListJavi Alcaraz Leon0% (1)

- Julia Mannherz, Nationalism, Imperialism and Cosmopolitanism in Russian Nineteenth-Century Provincial Amateur Music-MakingДокумент28 страницJulia Mannherz, Nationalism, Imperialism and Cosmopolitanism in Russian Nineteenth-Century Provincial Amateur Music-MakingVd0Оценок пока нет

- NecessitiesДокумент13 страницNecessitiesJoseph GibbsОценок пока нет

- YSO - Fall 2019 Principal Trumpet Audition AnnouncementДокумент1 страницаYSO - Fall 2019 Principal Trumpet Audition AnnouncementErik ShinnОценок пока нет

- Horns Mouthpieces and MutesДокумент4 страницыHorns Mouthpieces and Mutesapi-425284294Оценок пока нет

- Orchestration - WikipediaДокумент2 страницыOrchestration - WikipediaA CОценок пока нет

- Horn Trio Horn PartДокумент7 страницHorn Trio Horn PartJeff Harrington100% (1)

- Horn Call - October 2016 Natural Horn Technique Guiding Modern Orchestral PerformanceДокумент2 страницыHorn Call - October 2016 Natural Horn Technique Guiding Modern Orchestral Performanceapi-571012069Оценок пока нет

- View Attempt 1 of 1: Assessments View All SubmissionsДокумент15 страницView Attempt 1 of 1: Assessments View All SubmissionsShawn Goulette100% (3)

- Euyo Auditions: Solo RepertoireДокумент6 страницEuyo Auditions: Solo RepertoireFilippo SantacroceОценок пока нет

- Premio Frederick Fennell PDFДокумент10 страницPremio Frederick Fennell PDFSamanosuke7AОценок пока нет

- Wren - The Compositional Eclecticism of Bohuslav Martinů. Chamber Works Featuring Oboe, Part II PDFДокумент19 страницWren - The Compositional Eclecticism of Bohuslav Martinů. Chamber Works Featuring Oboe, Part II PDFMelisa CanteroОценок пока нет

- Horn Rep 1Документ6 страницHorn Rep 1api-266767873100% (1)

- Rossini - Wilhelm Tell Overture - 00 ScoreДокумент29 страницRossini - Wilhelm Tell Overture - 00 ScoreEdgars KalninsОценок пока нет

- 39Документ5 страниц39Fidel German Canto ReyesОценок пока нет

- IMSLP321981-SIBLEY1802 22862 E71e-39087009886922scoreДокумент76 страницIMSLP321981-SIBLEY1802 22862 E71e-39087009886922scoreCarlos Parra-MojicaОценок пока нет

- Albeniz Op165 No2 Tango TrumpetДокумент5 страницAlbeniz Op165 No2 Tango Trumpetstomvi3Оценок пока нет

- Symphony FantastiqueДокумент18 страницSymphony FantastiqueGerardo RiveraОценок пока нет

- PDF DatastreamДокумент76 страницPDF DatastreamTom GodbertОценок пока нет

- Trombone FanfareДокумент2 страницыTrombone FanfareAntonioLealОценок пока нет

- Waterfall DuetДокумент2 страницыWaterfall Duetapi-438486704Оценок пока нет

- Listening List of Orchestral MusicДокумент2 страницыListening List of Orchestral MusicJack PhillipsОценок пока нет

- Trom FinallyДокумент5 страницTrom Finallyapi-478100074Оценок пока нет

- Riversongs PresentationДокумент11 страницRiversongs Presentationapi-240855268Оценок пока нет

- Saint Saens Carnaval 13 Cygne TrumpetДокумент4 страницыSaint Saens Carnaval 13 Cygne TrumpetGilda LamuñoОценок пока нет

- Beethoven Fantasia Corale Op. 80 PartituraДокумент56 страницBeethoven Fantasia Corale Op. 80 PartituraDaniele GrottОценок пока нет

- 2019 All-State Orchestra Audition EtudesДокумент3 страницы2019 All-State Orchestra Audition EtudesThoriqОценок пока нет

- Music Teachers National Association American Music TeacherДокумент7 страницMusic Teachers National Association American Music TeacherMeriç Esen0% (1)

- Conducting - Modest Mussorgsky Pictures at An ExhibitionДокумент2 страницыConducting - Modest Mussorgsky Pictures at An ExhibitionBrody100% (1)

- Horn Ensmeble - MatlickДокумент6 страницHorn Ensmeble - Matlickapi-478048548Оценок пока нет

- The Sonata-Form Finale of Beethoven's 9th Symphony - Ernest Sanders (1998)Документ8 страницThe Sonata-Form Finale of Beethoven's 9th Symphony - Ernest Sanders (1998)alsebalОценок пока нет

- Vaughan Williams Beeler - Rhosymedre - AnalysisДокумент8 страницVaughan Williams Beeler - Rhosymedre - Analysisapi-425744426Оценок пока нет

- Portões-Celestiais Trombone 1Документ1 страницаPortões-Celestiais Trombone 1Phernando MacêdoОценок пока нет

- Topolewski Errata AnalysisДокумент7 страницTopolewski Errata AnalysisAndrew JanesОценок пока нет

- Tanan Di Bawah AnginДокумент80 страницTanan Di Bawah AnginLI ZHUOHENG HCIОценок пока нет

- Fagot 2° (Huapango)Документ5 страницFagot 2° (Huapango)Chilo IssidОценок пока нет

- Unit 6 17 Beethoven Septet in E Flat Op 20 Movement IДокумент6 страницUnit 6 17 Beethoven Septet in E Flat Op 20 Movement IAlison Cooper-WhiteОценок пока нет

- Walton - Orb and SceptreДокумент3 страницыWalton - Orb and SceptreJoshua HuОценок пока нет

- Debussy: Prélude À L'après-Midi D'un FauneДокумент1 страницаDebussy: Prélude À L'après-Midi D'un FauneLisa Barge100% (1)

- 22tuba Excerpts From First Suite and Toccata Marziale 22Документ3 страницы22tuba Excerpts From First Suite and Toccata Marziale 22api-425394984Оценок пока нет

- Oct 19 Midsummer Night's DreamДокумент16 страницOct 19 Midsummer Night's DreamImani MosleyОценок пока нет

- Essays On Henry PurcellДокумент145 страницEssays On Henry PurcellImani MosleyОценок пока нет

- HLC Harvard ProgrammeДокумент6 страницHLC Harvard ProgrammeImani MosleyОценок пока нет

- Ravel Pavane For A Dead PrincessДокумент3 страницыRavel Pavane For A Dead PrincessImani Mosley0% (2)

- Chain: SRB Series (With Insulation Grip)Документ1 страницаChain: SRB Series (With Insulation Grip)shankarОценок пока нет

- Passage Planning: Dr. Arwa HusseinДокумент15 страницPassage Planning: Dr. Arwa HusseinArwa Hussein100% (3)

- 1.classification of Reciprocating PumpsДокумент8 страниц1.classification of Reciprocating Pumpsgonri lynnОценок пока нет

- WCDMA Radio Access OverviewДокумент8 страницWCDMA Radio Access OverviewDocMasterОценок пока нет

- Fellows (Antiques)Документ90 страницFellows (Antiques)messapos100% (1)

- RESEARCHДокумент5 страницRESEARCHroseve cabalunaОценок пока нет

- Economics - Economics - Cheat - SheetДокумент1 страницаEconomics - Economics - Cheat - SheetranaurОценок пока нет

- GST RATE LIST - pdf-3Документ6 страницGST RATE LIST - pdf-3Niteesh KumarОценок пока нет

- Ass AsДокумент23 страницыAss AsMukesh BishtОценок пока нет

- Present Perfect and Present Perfect ProgressiveДокумент5 страницPresent Perfect and Present Perfect ProgressiveKiara Fajardo matusОценок пока нет

- Teamcenter 10.1: Publication Number PLM00015 JДокумент122 страницыTeamcenter 10.1: Publication Number PLM00015 JmohanОценок пока нет

- Code of Practice For Design Loads (Other Than Earthquake) For Buildings and StructuresДокумент39 страницCode of Practice For Design Loads (Other Than Earthquake) For Buildings and StructuresIshor ThapaОценок пока нет

- Speaking RubricДокумент1 страницаSpeaking RubricxespejoОценок пока нет

- Dress Code19sepДокумент36 страницDress Code19sepapi-100323454Оценок пока нет

- (Ebook - Antroposofia - EnG) - Rudolf Steiner - Fundamentals of TheraphyДокумент58 страниц(Ebook - Antroposofia - EnG) - Rudolf Steiner - Fundamentals of Theraphyblueyes247Оценок пока нет

- Unit 20: TroubleshootingДокумент12 страницUnit 20: TroubleshootingDongjin LeeОценок пока нет

- Linux and The Unix PhilosophyДокумент182 страницыLinux and The Unix PhilosophyTran Nam100% (1)

- When SIBO & IBS-Constipation Are Just Unrecognized Thiamine DeficiencyДокумент3 страницыWhen SIBO & IBS-Constipation Are Just Unrecognized Thiamine Deficiencyps piasОценок пока нет

- Democracy or Aristocracy?: Yasir MasoodДокумент4 страницыDemocracy or Aristocracy?: Yasir MasoodAjmal KhanОценок пока нет

- Do Now:: What Is Motion? Describe The Motion of An ObjectДокумент18 страницDo Now:: What Is Motion? Describe The Motion of An ObjectJO ANTHONY ALIGORAОценок пока нет

- QSasДокумент50 страницQSasArvin Delos ReyesОценок пока нет

- ENSC1001 Unit Outline 2014Документ12 страницENSC1001 Unit Outline 2014TheColonel999Оценок пока нет

- Unit 3: Theories and Principles in The Use and Design of Technology Driven Learning LessonsДокумент5 страницUnit 3: Theories and Principles in The Use and Design of Technology Driven Learning Lessons서재배Оценок пока нет

- Furniture AnnexДокумент6 страницFurniture AnnexAlaa HusseinОценок пока нет

- Random Questions From Various IIM InterviewsДокумент4 страницыRandom Questions From Various IIM InterviewsPrachi GuptaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 6 Strategy Analysis and Choice: Strategic Management: A Competitive Advantage Approach, 16e (David)Документ27 страницChapter 6 Strategy Analysis and Choice: Strategic Management: A Competitive Advantage Approach, 16e (David)Masum ZamanОценок пока нет

- Week 1 Familiarize The VmgoДокумент10 страницWeek 1 Familiarize The VmgoHizzel De CastroОценок пока нет

- Pre-Paid Customer Churn Prediction Using SPSSДокумент18 страницPre-Paid Customer Churn Prediction Using SPSSabhi1098Оценок пока нет

- Free ConvectionДокумент4 страницыFree ConvectionLuthfy AditiarОценок пока нет

- Using Your Digital Assets On Q-GlobalДокумент3 страницыUsing Your Digital Assets On Q-GlobalRemik BuczekОценок пока нет