Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

NHAI's New Exit Policy for Road Project Developers

Загружено:

shreemanthsОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

NHAI's New Exit Policy for Road Project Developers

Загружено:

shreemanthsАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

[February 26, 2014]

NHAIS EXIT POLICY FOR ROAD PROJECTS NHAI on 29 January, 2014 notified a new exit policy (Exit Policy) for highway developers which allows original consortium members of the Concessionaire (the Project SPV) to exit by way of a substitution mechanism. The earlier NHAI exit policy circular dated July 17, 2013 permitted substitution of only original Project SPV with a new company, instead of a direct exit of consortium members. This note sets out a snapshot of the key aspects of the Exit Policy. 1. Applicability of the Exit Policy

The Exit Policy is applicable to only following national highway projects: (a) On-going 2-laning and 4-laning projects, which have achieved financial closure (but not COD); (b) On-going 6-laning projects, which have achieved financial closure (but completion certificate is not issued); (c) Completed 2 laning, 4-laning and 6-laning BOT projects; (d) All new 2-laning, 4-laning projects and 6-laning PPP projects to be awarded in future on BOT basis. This Exit Policy clearly excludes a large number of recent BOT projects which have not yet achieved financial closure. 2. Pre-condition(s) for Substitution

Financial Distress: The original substitution agreement requires that a financial default should have actually occurred before resorting to substitution. The Exit Policy permits substitution without an actual financial default. In the Exit Policy, the definition of Financial Default is expanded to include a scenario where the following two conditions are fulfilled in the considered opinion of lenders and/or NHAI: (a) Project SPV is likely to face financial distress; and (b) Project SPV is likely to default under the terms of the Concession Agreement. As for the process, the Project SPV would need to make a written representation to the lenders with a request to them to seek NHAI approval for substitution. It appears that this representation would essentially need to demonstrate financial distress requirement. One potential challenge in this respect is that self declaration of financial distress may trigger cross defaults under other agreements of the consortium members/Project SPV, depending on the drafting of events of default, insolvency proceedings, etc., in other agreements. It would be interesting to see if the Exit Policy provides an exit route for developers of projects which are financially viable. Financial distress of the project SPV as a precondition for substitution gives a prima facie impression that the Exit Policy might not apply in relation to viable projects.

[February 26, 2014]

It is however worthwhile exploring whether deterioration in the financial health of consortium members leading to a potential inability to make requisite equity contributions or to continue maintaining any required guarantees or discharging any undertakings which may be required under the financing documents, or the likelihood of attachment and sale of their assets including shares of the Project SPV, can be said to lead to financial distress of the Project SPV and consequent breach of the concession agreement. There is another interesting detail in the Exit Policy. Paragraph 4 of the Exit Policy clarifies that the right of substitution by the lenders representative is not limited to situations listed in the substitution agreement. Thus, it can be argued that the Exit Policy allows the lenders to recommend substitution even in projects where there is neither financial default nor financial distress, if they consider such substitution to be in the interest of the project (please note that the general rule which the lenders need to follow while recommending substitution is set out in para 4(i) of the Exit Policy which says that the lenders representative needs to be satisfied that the proposed substitution will be in the interest of the project). Notwithstanding the language of the Exit Policy which ostensibly vests wide discretion in the lenders to recommend substitution, considering the reluctance with which the exit policy was brought in, the chances of convincing the lenders to exercise wide discretion in this regard might not be very high. It would, therefore, be important for the developer and investor communities to engage with the lenders and explore their willingness for recommending substitution without any financial default or distress in the project. 3. Role of Lenders

The substitution process is to be initiated and led by the project's lenders. Therefore, the Exit Policy, it appears, would be inapplicable to projects where loan obligations have been fully discharged, in which case, promoters of such projects would continue to be subject to lock in provisions of the concession agreement. While this is ironic, given that the objective behind the Exit Policy was to rescue the roads sector and the lenders from the current financial distress, this does not seem to be an oversight. This 'no full exit in zero debt road SPVs' also makes the Exit Policy less than ideal for attracting financial investors into completed projects. Lenders need to assume a central role to implement the substitution under the Exit Policy. The key responsibilities cast on the lenders include determining whether the substitution would be in the interest of the Project, selection (and to some extent certification) of substitute entity (or substitute promoters), equity valuation for substitution and recommendation of substitution to NHAI. It remains to be seen if the lenders would be willing to assume these responsibilities except in cases where failure to do so would jeopardize their own interests. If the lenders show any reluctance or resistance in assuming these responsibilities, the expanded avenues under the Exit Policy for substitution might get negated, practically! 4. Approval from NHAI

The lenders' proposal for substitution is to be submitted to NHAI for its approval. NHAI's discretion to reject the proposal appears to be limited to determining whether the credentials of the substituting entity are satisfactory, which are: 2

[February 26, 2014]

(a) (b)

for operational projects, adequate experience in O&M of completed road projects by itself or through its associates or subsidiaries; and for under-construction projects, requisite financial and technical qualifications for bidding a similar or bigger project;

However, it remains to be seen whether NHAI will limit its approval to this specific question or will analyse the broader question of whether the substitution should take place or not in the first place. 5. Conclusion

If lenders are willing to initiate the substitution process only in cases of acute financial distress, the Exit Policy is unlikely to benefit the investor community as their exit from projects would also be subject to the conditions under the Exit Policy. A financial investor would balk at the prospect of having to self declare financial distress! These are however early days of the Exit Policy, and it remains to be seen if the lenders embrace the idea that substitution can be proposed even where there is no financial distress and how NHAI reacts to any such recommendation. Another hitch is the fact that investors in projects where loan obligations have been discharged, would not be able to take the benefit of the Exit Policy. Given these hurdles around an eventual full exit by a new investor and the ambiguities around feasibility of full exit in financially viable projects, acquisition transactions of the relevant projects are likely to be acquisition of majority stakes (to the extent allowed in the concession agreements), with the original promoters retaining the remaining shareholding. In this context, it would be essential for acquisition documentation to contain robust frameworks for governance and operation of the SPV, sharing of costs, profits, etc.

Вам также может понравиться

- Multi-Party and Multi-Contract Arbitration in the Construction IndustryОт EverandMulti-Party and Multi-Contract Arbitration in the Construction IndustryОценок пока нет

- Guidelines for Fuel Stations & Private Properties on National HighwaysДокумент97 страницGuidelines for Fuel Stations & Private Properties on National Highwaysgaurav dixit50% (2)

- Contract Law in Msia Brochure (MKTG)Документ2 страницыContract Law in Msia Brochure (MKTG)Liaw Ee PinОценок пока нет

- Irc Gov in 070 2017Документ60 страницIrc Gov in 070 2017brisk engineering consultantОценок пока нет

- Procedure for project approval in Indian road transport ministryДокумент4 страницыProcedure for project approval in Indian road transport ministrypvijayabharathiОценок пока нет

- Contract Law in SingaporeДокумент17 страницContract Law in Singaporenta_2502Оценок пока нет

- Bs 8666 Reinforcement Shape CodesДокумент1 страницаBs 8666 Reinforcement Shape CodesBenedict HoorkwapОценок пока нет

- Stride Rev 170409Документ6 страницStride Rev 170409nikfaridfazrilОценок пока нет

- Ham - 16062017Документ17 страницHam - 16062017sumit pamecha100% (1)

- Proposed Methodology - 4.0 Design Standard & Perimeter 1Документ20 страницProposed Methodology - 4.0 Design Standard & Perimeter 1Zaidi MohamadОценок пока нет

- Types of Contract in Construction IndustryДокумент138 страницTypes of Contract in Construction IndustryArpit GautamОценок пока нет

- A1-2 Delegation To RE Final DraftДокумент5 страницA1-2 Delegation To RE Final DraftManuela RosianОценок пока нет

- Indicative Draft Terms of Reference - HPSRP - II (15022018)Документ103 страницыIndicative Draft Terms of Reference - HPSRP - II (15022018)Amar NegiОценок пока нет

- Table of Content 3: Geomteric Design of Namboole RoadДокумент18 страницTable of Content 3: Geomteric Design of Namboole RoadIvan MasubaОценок пока нет

- Clarification on GST Applicability for Highway Construction ProjectsДокумент2 страницыClarification on GST Applicability for Highway Construction Projectssantosh yevvariОценок пока нет

- Design Reinforced Earth Retaining Walls For FlyoverДокумент5 страницDesign Reinforced Earth Retaining Walls For FlyoverSa SureshОценок пока нет

- 12-Ref No 07Документ1 страница12-Ref No 07pvenki123Оценок пока нет

- Road Various Detail RevДокумент83 страницыRoad Various Detail RevCIVIL ENGINEERINGОценок пока нет

- L&T MetroДокумент7 страницL&T MetroSaigyan RanjanОценок пока нет

- Autoplotter With Road Estimator Software PDFДокумент4 страницыAutoplotter With Road Estimator Software PDFpediredlakumar50% (2)

- Road Work SpecificationsДокумент71 страницаRoad Work SpecificationsAbdulla NaushadОценок пока нет

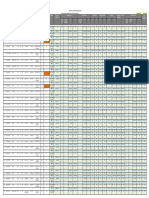

- Master Project Schedule for Oil & Gas DevelopmentДокумент1 страницаMaster Project Schedule for Oil & Gas DevelopmentHua Tien Dung100% (1)

- Use of Fly Ash in Road Flyover Embankment Construction On NH Works Reg DT On 23rd October 2020 (1) - Compressed - Compressed PDFДокумент27 страницUse of Fly Ash in Road Flyover Embankment Construction On NH Works Reg DT On 23rd October 2020 (1) - Compressed - Compressed PDFLASA VADODARAОценок пока нет

- Gurdaspur Sri Hargobindpur Road (Maintenance) 255 Days Tue 07-11-06 Tue 04-09-07Документ4 страницыGurdaspur Sri Hargobindpur Road (Maintenance) 255 Days Tue 07-11-06 Tue 04-09-07Daljeet SidhuОценок пока нет

- CPCCBC4003A-Select-and-prepare A Construction ContractДокумент57 страницCPCCBC4003A-Select-and-prepare A Construction Contractsaher iqbalОценок пока нет

- Payments on disputed sums risks minimizedДокумент3 страницыPayments on disputed sums risks minimizedmarx0506Оценок пока нет

- Highway Construction Production Rates and Estimated Contracct TimesДокумент95 страницHighway Construction Production Rates and Estimated Contracct TimesLTE002Оценок пока нет

- Claims Under FIDIC 2016 HoganДокумент4 страницыClaims Under FIDIC 2016 HogangimasaviОценок пока нет

- CONTRACTOR 12 Magazine - 4utr1a9dДокумент52 страницыCONTRACTOR 12 Magazine - 4utr1a9dOkudetum Rapheal100% (1)

- Measured Mile Labor AnalysisДокумент6 страницMeasured Mile Labor AnalysisSanjeevi JayachandranОценок пока нет

- Discharge of Contract LawДокумент8 страницDischarge of Contract LawAbi abiramiОценок пока нет

- Construction Security and Performance Documents 1st - Edition RicsДокумент42 страницыConstruction Security and Performance Documents 1st - Edition RicsZoltan ZavoczkyОценок пока нет

- SCL India Virtual Conference 2021Документ30 страницSCL India Virtual Conference 2021arkirthi1175Оценок пока нет

- Claims and Variations: Procedure CAP007M Contract Administration System (CAS) ManualДокумент16 страницClaims and Variations: Procedure CAP007M Contract Administration System (CAS) ManualHasitha AthukoralaОценок пока нет

- Irc 039-1986Документ15 страницIrc 039-1986harivennelaОценок пока нет

- Case Study-1 (Travails in Desert, Due To Change in Scope)Документ31 страницаCase Study-1 (Travails in Desert, Due To Change in Scope)hari menonОценок пока нет

- Performance-Based Contracts (PBC)Документ110 страницPerformance-Based Contracts (PBC)Xavier Molina ArceОценок пока нет

- GST Book ConstructionДокумент121 страницаGST Book Constructionvijaykadam_ndaОценок пока нет

- Construction Project Claim ResolutionДокумент50 страницConstruction Project Claim ResolutionDAGMAWI ASNAKEОценок пока нет

- Adjustment of Contract SumДокумент8 страницAdjustment of Contract SumNor Aniza100% (1)

- FHWA Guidelines For Preparing Engineer's Estimate Bid Reviews and Evaluation (2004)Документ18 страницFHWA Guidelines For Preparing Engineer's Estimate Bid Reviews and Evaluation (2004)Amanda CervantesОценок пока нет

- Talegaon Amravat (Approved Length 58 KM) Vol. II & IIIДокумент490 страницTalegaon Amravat (Approved Length 58 KM) Vol. II & IIIUjjval JainОценок пока нет

- NHAI Financial Consultant RFP for OMT Highway ProjectsДокумент18 страницNHAI Financial Consultant RFP for OMT Highway ProjectsdaobvpОценок пока нет

- Bqs 2203 Construction Law II Course OutlineДокумент4 страницыBqs 2203 Construction Law II Course OutlineShinet V MlamboОценок пока нет

- Maintenance of Roads: by D. P. GuptaДокумент24 страницыMaintenance of Roads: by D. P. Guptawanroy100% (1)

- Contract Indian Vs FidicДокумент12 страницContract Indian Vs FidicPritam MondalОценок пока нет

- Variation in QuantityДокумент24 страницыVariation in QuantityPADMANОценок пока нет

- Prolongation Cost Claims - The Basic Principles: Craig Enderbury, Executive Director, HKAДокумент6 страницProlongation Cost Claims - The Basic Principles: Craig Enderbury, Executive Director, HKAKMHoОценок пока нет

- Evolution of India's Model Concession AgreementДокумент37 страницEvolution of India's Model Concession AgreementkumarnramОценок пока нет

- 01-MoRTH Road Specification 5th Revision - CroppedДокумент906 страниц01-MoRTH Road Specification 5th Revision - CroppedSaumitr ChaturvediОценок пока нет

- PPPs Tollway EngДокумент28 страницPPPs Tollway EngASHIОценок пока нет

- Can Contractors Claim Loss of Profit on Omitted WorksДокумент2 страницыCan Contractors Claim Loss of Profit on Omitted WorksseraphmauОценок пока нет

- Light at The End of The Tunnel? Gibraltar Dispute Reviews Key Fidic Yellow Book ProvisionsДокумент15 страницLight at The End of The Tunnel? Gibraltar Dispute Reviews Key Fidic Yellow Book ProvisionsPriyank KulshreshthaОценок пока нет

- Claims ConstructionДокумент11 страницClaims ConstructionsvetОценок пока нет

- Claims PreparationДокумент10 страницClaims PreparationMohammed ShafiОценок пока нет

- Construction of Airport in Shivamogga Taluk TenderДокумент41 страницаConstruction of Airport in Shivamogga Taluk TenderER Aditya DasОценок пока нет

- Measured MileДокумент9 страницMeasured Milesohail2006Оценок пока нет

- Solar PV Hybrid Power Plants For Petrol SystemДокумент27 страницSolar PV Hybrid Power Plants For Petrol SystemLakshmi NarayananОценок пока нет

- Utility Scale Solar Power Plants: A Guide For Developers and InvestorsДокумент204 страницыUtility Scale Solar Power Plants: A Guide For Developers and InvestorsIFC Sustainability94% (18)

- Probability of Default Basic Methods Overview: Toma S Va Clavı KДокумент16 страницProbability of Default Basic Methods Overview: Toma S Va Clavı KshreemanthsОценок пока нет

- Hampi Travel GuideДокумент3 страницыHampi Travel GuideshreemanthsОценок пока нет

- Status As On 17-Jan-13 Jetpur-Somnath Project (NH - 8D) Comprehensive Monitoring of Critical StructuresДокумент2 страницыStatus As On 17-Jan-13 Jetpur-Somnath Project (NH - 8D) Comprehensive Monitoring of Critical Structuresshreemanths100% (1)

- Benefits of Primavera P6 for construction performanceДокумент1 страницаBenefits of Primavera P6 for construction performanceshreemanthsОценок пока нет

- Fire Protection TACДокумент72 страницыFire Protection TACNandkishore Paramal MandothanОценок пока нет

- Insurance Act 1938Документ123 страницыInsurance Act 1938abhinav_surveyor1355Оценок пока нет

- Construction and Infrastructure Projects - Risk Management Through Insurance 50Документ50 страницConstruction and Infrastructure Projects - Risk Management Through Insurance 50Carl Williams100% (1)

- India Foriegn Trade Policy Handbook of Procedures - HandbookYear2007 - 2014Документ142 страницыIndia Foriegn Trade Policy Handbook of Procedures - HandbookYear2007 - 2014JoyОценок пока нет

- GL Corp ProfileДокумент33 страницыGL Corp ProfileshreemanthsОценок пока нет

- Contractors All Risk Insurance Policy Guidelines From IIB PDFДокумент40 страницContractors All Risk Insurance Policy Guidelines From IIB PDFshreemanths100% (1)

- Oriental's Advance Loss of Profit Insurance ExplainedДокумент13 страницOriental's Advance Loss of Profit Insurance ExplainedshreemanthsОценок пока нет

- Fidic Licence AgreementДокумент6 страницFidic Licence AgreementshreemanthsОценок пока нет

- Fidic Licence AgreementДокумент6 страницFidic Licence AgreementshreemanthsОценок пока нет

- SCL Delay and Disruption Protocol - Subject To Rider 1Документ85 страницSCL Delay and Disruption Protocol - Subject To Rider 1Blaženka JelaОценок пока нет

- Oriental's Advance Loss of Profit Insurance ExplainedДокумент13 страницOriental's Advance Loss of Profit Insurance ExplainedshreemanthsОценок пока нет

- ACE1900 All Risks Cover For Machinery Installation Contractors Plant and Tools PDFДокумент6 страницACE1900 All Risks Cover For Machinery Installation Contractors Plant and Tools PDFshreemanthsОценок пока нет

- UGC NET Commerce SyllabusДокумент14 страницUGC NET Commerce SyllabusugcnetworkОценок пока нет

- The Merchant of Venice QuestionsДокумент9 страницThe Merchant of Venice QuestionsHaranath Babu50% (4)

- Burberry Financial AnalysisДокумент17 страницBurberry Financial AnalysisGiulio Francesca50% (2)

- CH 04 Review and Discussion Problems SolutionsДокумент23 страницыCH 04 Review and Discussion Problems SolutionsArman Beirami67% (3)

- NBP Unconsolidated Financial Statements 2015Документ105 страницNBP Unconsolidated Financial Statements 2015Asif RafiОценок пока нет

- General AnnuityДокумент21 страницаGeneral AnnuityMark Alconaba GeronimoОценок пока нет

- Summary Economics of Money Banking and Financial Markets Frederic S Mishkin PDFДокумент143 страницыSummary Economics of Money Banking and Financial Markets Frederic S Mishkin PDFJohn StephensОценок пока нет

- ROMMSДокумент190 страницROMMSspandanОценок пока нет

- BPD AssignmentДокумент2 страницыBPD AssignmentSoniya ShahuОценок пока нет

- Tutorial 1 - SolutionДокумент3 страницыTutorial 1 - SolutionSuganti100% (1)

- 2009-04-09 130229 Case 12-4Документ5 страниц2009-04-09 130229 Case 12-4NadhilaОценок пока нет

- Fears and Lobbying in Colli..Документ9 страницFears and Lobbying in Colli..spudgun56Оценок пока нет

- RMC 08-90 VAT On DepositsДокумент8 страницRMC 08-90 VAT On DepositsRieland CuevasОценок пока нет

- Later in Life Lawyers - Tips For The Non-Traditional Law Student - Charles CooperДокумент215 страницLater in Life Lawyers - Tips For The Non-Traditional Law Student - Charles CooperSteveManningОценок пока нет

- Finance1 LectureДокумент16 страницFinance1 LectureRegimhel Dalisay75% (4)

- Excel RoundДокумент6 страницExcel RoundRajesh VarunОценок пока нет

- J.P. Morgan - Taking EM Asia's Pulse PDFДокумент7 страницJ.P. Morgan - Taking EM Asia's Pulse PDFkumarrajdeepbsrОценок пока нет

- Solved Scanner CA Final Paper 2Документ3 страницыSolved Scanner CA Final Paper 2Mayank Goyal0% (1)

- Youthonomics Global Index 101315Документ57 страницYouthonomics Global Index 101315Leonardo GuittonОценок пока нет

- Internship Report UBLДокумент133 страницыInternship Report UBLInamullah KhanОценок пока нет

- United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitДокумент10 страницUnited States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Important Insurance Financial Awareness QuestionsДокумент11 страницImportant Insurance Financial Awareness QuestionsJagannath JagguОценок пока нет

- Types of Letters of Credit ExplainedДокумент3 страницыTypes of Letters of Credit ExplainedckapasiОценок пока нет

- Chapter 3 Review Quiz SolutionsДокумент4 страницыChapter 3 Review Quiz SolutionsA. ZОценок пока нет

- Credit Rating AgencyДокумент9 страницCredit Rating AgencySreevidya KotaОценок пока нет

- MAD Real Estate Report 2015Документ479 страницMAD Real Estate Report 2015Bayarsaikhan SamdanОценок пока нет

- Resources M&a Articles and Cases by RFB Aug 2004Документ6 страницResources M&a Articles and Cases by RFB Aug 2004Bagus Be WeОценок пока нет

- OBLICON-2nd Exam - 1245 (Dation) and 1252 (Application)Документ2 страницыOBLICON-2nd Exam - 1245 (Dation) and 1252 (Application)Karen Joy MasapolОценок пока нет

- PT Mayora Indah TBK Dan Entitas Anak/: and Its SubsidiariesДокумент76 страницPT Mayora Indah TBK Dan Entitas Anak/: and Its SubsidiariesPascario TheoОценок пока нет

- Duxbury Clipper 07 - 08 - 2009Документ40 страницDuxbury Clipper 07 - 08 - 2009Duxbury ClipperОценок пока нет

- Asset and Liability HDFCДокумент5 страницAsset and Liability HDFCShams S100% (1)

- Love Your Life Not Theirs: 7 Money Habits for Living the Life You WantОт EverandLove Your Life Not Theirs: 7 Money Habits for Living the Life You WantРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (146)

- Financial Literacy for Managers: Finance and Accounting for Better Decision-MakingОт EverandFinancial Literacy for Managers: Finance and Accounting for Better Decision-MakingРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- I Will Teach You to Be Rich: No Guilt. No Excuses. No B.S. Just a 6-Week Program That Works (Second Edition)От EverandI Will Teach You to Be Rich: No Guilt. No Excuses. No B.S. Just a 6-Week Program That Works (Second Edition)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (12)

- The Science of Prosperity: How to Attract Wealth, Health, and Happiness Through the Power of Your MindОт EverandThe Science of Prosperity: How to Attract Wealth, Health, and Happiness Through the Power of Your MindРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (231)

- I'll Make You an Offer You Can't Refuse: Insider Business Tips from a Former Mob Boss (NelsonFree)От EverandI'll Make You an Offer You Can't Refuse: Insider Business Tips from a Former Mob Boss (NelsonFree)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (24)

- Excel for Beginners 2023: A Step-by-Step and Quick Reference Guide to Master the Fundamentals, Formulas, Functions, & Charts in Excel with Practical Examples | A Complete Excel Shortcuts Cheat SheetОт EverandExcel for Beginners 2023: A Step-by-Step and Quick Reference Guide to Master the Fundamentals, Formulas, Functions, & Charts in Excel with Practical Examples | A Complete Excel Shortcuts Cheat SheetОценок пока нет

- Profit First for Therapists: A Simple Framework for Financial FreedomОт EverandProfit First for Therapists: A Simple Framework for Financial FreedomОценок пока нет

- Financial Intelligence: A Manager's Guide to Knowing What the Numbers Really MeanОт EverandFinancial Intelligence: A Manager's Guide to Knowing What the Numbers Really MeanРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (79)

- LLC Beginner's Guide: The Most Updated Guide on How to Start, Grow, and Run your Single-Member Limited Liability CompanyОт EverandLLC Beginner's Guide: The Most Updated Guide on How to Start, Grow, and Run your Single-Member Limited Liability CompanyРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- How to Start a Business: Mastering Small Business, What You Need to Know to Build and Grow It, from Scratch to Launch and How to Deal With LLC Taxes and Accounting (2 in 1)От EverandHow to Start a Business: Mastering Small Business, What You Need to Know to Build and Grow It, from Scratch to Launch and How to Deal With LLC Taxes and Accounting (2 in 1)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (5)

- Tax-Free Wealth: How to Build Massive Wealth by Permanently Lowering Your TaxesОт EverandTax-Free Wealth: How to Build Massive Wealth by Permanently Lowering Your TaxesОценок пока нет

- Financial Accounting - Want to Become Financial Accountant in 30 Days?От EverandFinancial Accounting - Want to Become Financial Accountant in 30 Days?Рейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- SAP Foreign Currency Revaluation: FAS 52 and GAAP RequirementsОт EverandSAP Foreign Currency Revaluation: FAS 52 and GAAP RequirementsОценок пока нет

- The E-Myth Chief Financial Officer: Why Most Small Businesses Run Out of Money and What to Do About ItОт EverandThe E-Myth Chief Financial Officer: Why Most Small Businesses Run Out of Money and What to Do About ItРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (13)

- Bookkeeping: An Essential Guide to Bookkeeping for Beginners along with Basic Accounting PrinciplesОт EverandBookkeeping: An Essential Guide to Bookkeeping for Beginners along with Basic Accounting PrinciplesРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (30)

- The ZERO Percent: Secrets of the United States, the Power of Trust, Nationality, Banking and ZERO TAXES!От EverandThe ZERO Percent: Secrets of the United States, the Power of Trust, Nationality, Banking and ZERO TAXES!Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (14)

- Basic Accounting: Service Business Study GuideОт EverandBasic Accounting: Service Business Study GuideРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (2)

- Bookkeeping: A Beginner’s Guide to Accounting and Bookkeeping for Small BusinessesОт EverandBookkeeping: A Beginner’s Guide to Accounting and Bookkeeping for Small BusinessesОценок пока нет

- Accounting: The Ultimate Guide to Understanding More about Finances, Costs, Debt, Revenue, and TaxesОт EverandAccounting: The Ultimate Guide to Understanding More about Finances, Costs, Debt, Revenue, and TaxesРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (4)

- Accounting Policies and Procedures Manual: A Blueprint for Running an Effective and Efficient DepartmentОт EverandAccounting Policies and Procedures Manual: A Blueprint for Running an Effective and Efficient DepartmentОценок пока нет

- Finance Basics (HBR 20-Minute Manager Series)От EverandFinance Basics (HBR 20-Minute Manager Series)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (32)

- Mysap Fi Fieldbook: Fi Fieldbuch Auf Der Systeme Anwendungen Und Produkte in Der DatenverarbeitungОт EverandMysap Fi Fieldbook: Fi Fieldbuch Auf Der Systeme Anwendungen Und Produkte in Der DatenverarbeitungРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- Accounting 101: From Calculating Revenues and Profits to Determining Assets and Liabilities, an Essential Guide to Accounting BasicsОт EverandAccounting 101: From Calculating Revenues and Profits to Determining Assets and Liabilities, an Essential Guide to Accounting BasicsРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (7)