Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Sales Promotion

Загружено:

Nechirvan KoshnowОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Sales Promotion

Загружено:

Nechirvan KoshnowАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences at an ethnic-group level

Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

School of Marketing, University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, Australia

Abstract Purpose Aims to examine the proposition that consumer sales promotions are more effective when they provide benets that are congruent with those of the promoted product. This proposition is considered at the ethnic-group level (i.e. do differences in cultural values at this level have an impact on sales promotion effectiveness?). Design/methodology/approach A quasi-experimental design is used to test a series of hypotheses based on a sample of Anglo-Australians and Chinese-Australians. The main experiment is informed by the results of two pretests. Findings First, there are signicant differences in consumer cultural values at an ethnic-group level. Second, despite these differences, ethnicity does not have a signicant impact on responses to sales promotions. Third, the expected congruency effects between products and promotion types are not found. Research limitations/implications Some of the detailed results match those reported in previous studies, but there are important differences too. Practical implications There is a need to be aware of differing cultural values at an ethnic-group level. Notwithstanding this inference, the second nding suggests that there continues to be scope for using standardised strategies when promoting to different ethnic groups. Finally, considerable caution should be exercised when planning promotion strategies around hoped-for congruency effects. Originality/value New light is cast on the relationship between consumer differences at an ethnic-group level and the effectiveness of various types of sales promotion for utilitarian and hedonic products. Keywords Consumers, Sales, Promotional methods, Ethnic groups, National cultures Paper type Research paper

Introduction

The widespread use of consumer sales promotions in product management has sparked considerable debate over their effectiveness. Critics argue that sales promotions are ineffective as they make consumers more promotion prone, resulting in market share losses in the long run (Ehrenberg et al., 1994; Totten and Block, 1987). However, other researchers have shown that sales promotions lead to real long-run increases in sales and prots (Dhar and Hoch, 1996; Hoch et al., 1994). This discrepancy suggests there are other factors at work; for instance, that sales promotions are more effective when they provide benets that are congruent with those of the promoted product (Chandon et al., 2000). This paper explores and extends the congruency framework by considering the potential impact of differences in consumer cultural values at an ethnic-group level. In principle, cultural differences at national and ethnic-group levels can impact many aspects of consumer behaviour, from service expectations to consumer innovativeness (Steenkamp et al., 1999; Bridges et al., 1996). An understanding of where these differences do and do not have an impact can assist in

The Emerald Research Register for this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/researchregister The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/1061-0421.htm

Journal of Product & Brand Management 14/3 (2005) 170 186 q Emerald Group Publishing Limited [ISSN 1061-0421] [DOI 10.1108/10610420510601049]

making marketing decisions, such as whether to pursue standardised or localised branding, pricing, advertising and promotion strategies (Fletcher and Brown, 1999). Many of the published studies in consumer marketing have only examined the impact of culture across nations, whereas important differences may also exist at an ethnic-group level for instance among Caucasian-Americans, HispanicAmericans, North African-French, Italian-Australians, etc. The importance of these differences is reected in growing interest in ethnic marketing by both researchers (e.g. Tan and McCullough, 1985; Lee et al., 2002) and practitioners (e.g. Rossman, 1994; AMA, 2003; Keefe, 2004). We contribute to this body of work by focusing on culture at an ethnic-group level and its impact on sales promotions. Several important contributions to both marketing theory and practice are made. First, aspects of work by Chandon et al. (2000) are replicated to assess the generality of the congruency framework of sales promotion effectiveness. Second, the work of Chandon et al. (2000) is extended they attempted a cross-national comparison, but did not explicitly look at the impact of culture. The study also develops work by Lowe and Corkindale (1998) who examined the impact of cultural values across a range of marketing activities. Third, measures of culture at the ethnic-group level provide evidence for the popular assumption that consumer differences do indeed exist at this level. Fourth, the study contributes to theory development by providing further validation of a relatively new scale for measuring cultural differences in a consumer context, namely the CVSCALE (Yoo et al., 2001; Yoo and Donthu, 2002). Finally, the study provides insights for product managers in the design of sales promotion strategies. It addresses the issue of whether to standardise or localise sales promotions between targeted 170

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

Journal of Product & Brand Management Volume 14 Number 3 2005 170 186

ethnic markets. It also offers insights for managers into the applicability (or otherwise) of the congruency framework for sales promotion. The paper is organised as follows. The next section provides a review of the sales promotions literature and considers the potential impact of ethnicity. Hypotheses are presented, followed by a discussion of key measures and stimuli. Results are described in subsequent sections. The study was undertaken in Australia, where a diverse ethnic mix of consumers exists and where packaged goods manufacturers and retailers are making increasing use of sales promotions. A discussion of the ndings is presented. We conclude by highlighting some limitations and by suggesting a few opportunities for future research.

Sales promotion and the potential impact of ethnicity

Types of sales promotion Typically, past studies of the effectiveness of consumer sales promotion have focused on monetary sales promotions (Dhar and Hoch, 1996; Hoch et al., 1994). However, in practice, both monetary and non-monetary sales promotions are used widely (Tellis, 1998). There are important differences between these two types: monetary promotions (e.g. shelf-price discounts, coupons, rebates and price packs) tend to provide fairly immediate rewards to the consumer and they are transactional in character; non-monetary promotions (e.g. sweepstakes, free gifts and loyalty programmes) tend to involve delayed rewards and are more relationship-based. In assessing the effectiveness of sales promotions it is necessary to examine both types. Benets of sales promotion Sales promotions can offer many consumer benets, the most obvious being monetary savings, although consumers also may be motivated by the desire for quality, convenience, value expression, exploration and entertainment (Babin et al., 1994; Hirschman and Holbrook, 1982). These benets are further classied as either utilitarian or hedonic (see Chandon et al., 2000, Table I). Utilitarian benets are primarily functional and relatively tangible. They enable consumers to maximise their shopping utility, efciency and economy. In general, the benets of savings, quality and convenience can be classied as utilitarian benets. By contrast, hedonic benets are more experiential and relatively intangible, associated as they are with intrinsic stimulation, fun and pleasure. Consistent with this denition, the benets of value expression, exploration and entertainment can be classied as hedonic benets. Promotion types and promotion benets Based on the distinction between the types of sales promotions and promotion benets, Chandon et al. (2000) showed that monetary promotions provide more utilitarian benets whilst non-monetary promotions provide more hedonic benets. These relationships are a matter of degree rather than absolutes; for example, coupon promotions (i.e. a monetary promotion) may still provide some hedonic benets such as the enjoyment in redemption, although its main benet of saving is utilitarian. Congruency theory and sales promotion The basic principle of congruency theory is that changes in evaluation are always in the direction that increases congruity 171

with the existing frame of reference (Osgood and Tannenbaum, 1955). In other words, people have a natural preference for consistent information. The principle has been examined in many marketing contexts, including studies of brand extensions and advertising appeals. Applying the congruity principle to sales promotions, it is expected that sales promotions will be more effective when they provide benets that are compatible with the benets sought from the promoted product. For example, Dowling and Uncles (1997) suggested the effectiveness of loyalty programmes is enhanced if programme benets directly support the value proposition of the brand. Roehm et al. (2002) went on to show that loyalty programmes are indeed more successful if they provide incentives that are compatible with the brand. Congruency effects for consumer sales promotions were directly tested and conrmed by Chandon et al. (2000), who showed that: monetary promotions are more effective for utilitarian products as they provide more utilitarian benets, which are compatible to those sought from utilitarian products; and non-monetary promotions are more effective for hedonic products as they provide more hedonic benets, which are compatible to those sought from hedonic products. For example, price cuts are more effective than free gifts for inuencing brand choice of laundry detergent (i.e. a utilitarian product), whereas sweepstakes are more effective than price cuts for inuencing brand choice of chocolates (i.e. a hedonic product). However, it is noted that there are other factors that may have an impact on the congruency effects, including the product life cycle, purchases situations and consumer demographics. Another possible factor, and the focus of this study, is culture at the ethnic-group level. Culture, sub-culture and ethnic groups Culture is complex and difcult to dene, but typically it is seen as a set of norms and beliefs that are shared among a group of people and that provide the guiding principles of their lives (Goodenough, 1971; Kroeber and Kluckholn, 1952; Schwartz and Bilsky, 1987, 1990). The focus in this study is on one particular aspect of culture: the way of life of people grouped by ethnicity, including shared norms and beliefs. For members of the ethnic group these shared norms and beliefs represent a prevailing way of life in a society, which will ultimately have an impact on their dispositions and behaviours, including their behaviour as consumers (Triandis, 1989). The denition here is exible in allowing cultural differences to be evident at various levels (consistent with conceptualisations by Dawar and Parker (1994) and Hofstede (1991)). The notion of society within the denition means culture is not necessarily restricted to a country basis, but instead it can exist at the sub-national level (e.g. ethnicChinese in Malaysia) or at a cross-country level (e.g. ethnicChinese throughout SE Asia). It has been suggested that equating culture with nation-states is often inappropriate because of very strong ethnic differences within countries (Lenartowicz and Roth, 1999; Usunier, 2000). In fact, intracountry variations of culture can be as large as the variation across countries (Au, 1999). This is important given the intracountry focus of this study. Here culture is examined at the ethnic-group level within the domestic Australian context. Ethnic groups can be considered as cultures or sub-cultures within a country. They preserve the main characteristics of the national culture from which they originate but also develop their own unique norms

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

Journal of Product & Brand Management Volume 14 Number 3 2005 170 186

and beliefs (Steenkamp et al., 1999; Usunier, 2000). Indeed, central to any ethnic group is a set of cultural values, attitudes and norms (Tan and McCullough, 1985). Each ethnic group constitutes a unique community because of common culture (Lee et al., 2002). This is particularly the case in the Australian context given its increasingly diverse ethnic mix and the feeling that it is perhaps no longer appropriate to represent Australia as a singular national culture (Millet, 2002; Bochner and Hesketh, 1994).

Hypotheses

In general, it is hypothesised that differences based on Hofstedes (1991) ve cultural dimensions can lead to relative differences between ethnic groups in their preference for promotion types. In effect, within the congruency relationships established between product and promotion types, ethnic groups may differ in their relative choices of monetary and nonmonetary promotions. For example, while monetary promotions might be more effective for utilitarian products, the choice share of monetary promotions may be higher for one ethnic group than another due to cultural differences. In the following, hypotheses are suggested for each of the ve cultural dimensions. It should be kept in mind that the theoretical strength of the hypotheses is not equal across the ve dimensions. For example, hypotheses regarding individualism/collectivism and uncertainty avoidance have a stronger theoretical logic than hypotheses regarding masculinity/femininity. Also, as is in the nature of any hypothesis testing of this kind, it is possible to conceive of alternative arguments. However, all ve dimensions have been included to ensure the study is comprehensive. Power distance Power distance deals with the acceptability of social inequalities, such as in power, wealth and status (Nakata and Sivakumar, 2001). In high power distance cultures, inequality is prevalent and accepted. Indeed, privileges and status symbols are both expected and desired (Hofstede, 1991). Consumers in such cultures are thus likely to be more responsive to sales promotions that offer differential benets. These mainly involve non-monetary promotions, in which differential benets may occur by purchase value (e.g. free gifts and reward programmes) or by chance (e.g. sweepstakes). In contrast, cultures with lower power distance are less tolerant of inequalities and special privileges (Hofstede, 1991). Consumers in such a culture would have a relatively higher preference for sales promotions that offer equal rewards for everyone. These mainly involve monetary promotions, such as price discounts and coupons, as they are generally available with the same level of benet offered to everyone. H1A. Monetary promotions are more effective for low power distance cultures relative to high power distance cultures. H1B. Non-monetary promotions are more effective for high power distance cultures relative to low power distance cultures. Uncertainty avoidance Uncertainty avoidance deals with the level of discomfort regarding future uncertainties (Nakata and Sivakumar, 2001). Although not exactly equivalent, it is closely related to risk aversion. In high uncertainty avoidance cultures, there is a tendency to prefer stable situations and avoid risk (Usunier, 2000). Thus, to the extent that uncertainty avoidance is related to risk aversion, such cultures would prefer promotions that offer more tangible and immediate rewards (e.g. price discounts). This is expected since such rewards are certain, unambiguous and involve little risk. On the other hand, cultures with low uncertainty avoidance are more risk tolerant and see opportunities within future uncertainties (Nakata and Sivakumar, 2001). In fact, they may even be 172

Culture, ethnic groups and sales promotion Cultural differences can inuence consumer responses to various marketing stimuli, including responses to sales promotion (Lowe and Corkindale, 1998; Yau, 1988). For example, Bridges et al. (1996) argued that there is a need for research directed at understanding culturally-driven responses of consumers to promotional activities. They showed that in a services context, cultural values affect the effectiveness of promotion strategies. However, most of these assessments have been conducted at a national level, whereas there is also a need for research to examine the effects of promotional activities on cultural groups within countries (Albaum and Peterson, 1984). There has been some consideration of this in previous studies. For example, it has been argued that various cultural sub-groups should react differently to different promotion strategies (Laroche et al., 2002) and that coupons are relatively less effective for African-Americans than Anglo-Americans (Green, 1995). Nevertheless, evidence at an ethnic-group level remains limited.

Cultural dimensions Given the potential relevance of culture, a basis is required for assessing its impact. Here use is made of the ve cultural dimensions popularised by Hofstede (1991): power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism-collectivism, masculinity-femininity and the Confucian dynamism. These dimensions are widely accepted and have been applied in a large number of cross-cultural studies (e.g. Sondergaard, 1994; Steenkamp et al., 1999; Zhang, 1997; Sivakumar and Nakata, 2001). The bulk of these studies have shown Hofstedes dimensions to be conceptually valid for explaining cultural differences. Use of these dimensions to examine sales promotions has been suggested previously. Kale and McIntyre (1991), for example, argued: there are specic relationships between (Hofstedes) cultural dimensions and the appropriate promotional policy. Also, it has been claimed the dimensions are capable of explaining intra-country variations (Au, 1999). However, in applying the dimensions to consumer-related values (as against the original workrelated values), with a focus on intra-country variations (not the cross-country comparisons envisaged in the original study), a number of adaptations have been made. In particular, the CVSCALE is employed (Yoo et al., 2001). While the dimensions remain the same power distance, uncertainty avoidance, etc. the items are adapted to suit the consumer context and they are designed to allow different ethnic groups within one country to be examined (discussed further in the Methodology section).

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

Journal of Product & Brand Management Volume 14 Number 3 2005 170 186

considered as risk seeking, given that cultures with low uncertainty avoidance have been shown to exhibit higher levels of innovativeness (Steenkamp et al., 1999). Thus, consumers in such a culture are likely to be more accepting of promotions that offer relatively less tangible and less certain rewards (e.g. sweepstakes and loyalty programmes). H2A. Monetary promotions are more effective for high uncertainty avoidance cultures relative to low uncertainty avoidance cultures. H2B. Non-monetary promotions are more effective for low uncertainty avoidance cultures relative to high uncertainty avoidance cultures. Individualism/collectivism Individualism refers to the degree of distance in social relationships (Nakata and Sivakumar, 2001). It has been suggested that relationships play an important role in the search and choice processes of consumers (Doran, 1994). Thus, the extent of individualism may affect consumer choices between different types of promotions. Individualistic cultures have distant social relationships, in which personal goals are favoured over group needs (Watkins and Liu, 1996). Value is placed on self-interest and independence (GurhanCanli and Maheswaran, 2000), as well as pleasure (Triandis and Hui, 1990). In addition, individualistic cultures emphasise differentiation (Aaker and Maheswaran, 1997) and the ability to express ones uniqueness (Watkins and Liu, 1996). Given these characteristics, individualistic cultures might be more receptive to non-monetary promotions since the associated hedonic benets are experiential, entertaining and fun. Furthermore, hedonic benets can provide more intrinsic value to individuals and provide an opportunity for self-expression. In contrast, less individualistic (or more collectivistic) cultures are characterised by group orientation and interdependence (Yau, 1988). There is strong emphasis on conforming to in-groups, which are typically close social groups such as family and friends (Hofstede, 1991). At the same time, entry and exit to other groups is difcult and rare (Watkins and Liu, 1996). Thus, collectivistic cultures can be expected to be less responsive to relationship building promotions (e.g. free gifts and reward programmes) since they will be reluctant to forge a relationship with an outgroup. Instead, collectivistic cultures may be more likely to respond to monetary promotions since the benets provided are more common (e.g. conform to group norms) and are more readily shared amongst the in-group (e.g., savings and quality). H3A. Monetary promotions are more effective for collectivistic cultures relative to individualistic cultures. H3B. Non-monetary promotions are more effective for individualistic cultures relative to collectivistic cultures. Masculinity/femininity Masculinity refers to the tendency to strive for personal achievement and performance (Cutler et al., 1997; Nakata and Sivakumar, 2001). In more masculine cultures, strong values are placed on materialistic success and assertiveness (Fletcher and Brown, 1999). It can be argued that consumers in masculine cultures are more likely to respond to monetary promotions, since the more tangible and transactional-based benets can satisfy the need of these consumers for personal 173

and materialistic success. At the other end of the spectrum, less masculine (or more feminine) cultures emphasise the values of nurturing, caring for others and the quality of life (Nakata and Sivakumar, 2001). There is relatively less emphasis on personal and materialistic gains. Instead, people and relationships are important (Hofstede, 1991) and group oriented harmony is preferred (Cutler et al., 1997). Thus, feminine cultures are expected to be more responsive to non-monetary promotions since the benets offered are more relationship focused. H4A. Monetary promotions are more effective for masculine cultures relative to feminine cultures. H4B. Non-monetary promotions are more effective for feminine cultures than masculine cultures.

Confucian dynamism The nal dimension of Confucian dynamism concerns time orientation and is bipolar. It has been suggested that the way consumers understand and allocate time may help explain differences in consumer behavior across cultures (Brodowsky and Anderson, 2000). The higher or positive end is related to a future-oriented perspective with values placed on persistence and loyalty (Fletcher and Brown, 1999). Consumers in such cultures are more willing to make short-term sacrices or investments for long-term gains (Nakata and Sivakumar, 2001). This is supported by research studies that have shown that people with a future orientation have a preference for delayed rewards (Klineberg, 1968). In effect, consumers in cultures high on Confucian dynamism are expected to be more responsive to non-monetary promotions such as loyalty programmes, since the rewards are long term and relationship-based (Foxman et al., 1988). By contrast, the lower or negative end is characterised by a past-oriented perspective, with an emphasis on traditions (Fletcher and Brown, 1999). People in such cultures favour short-term planning and more immediate nancial gains (Nakata and Sivakumar, 2001). This is supported by the fact that people with a past orientation are less likely to save money for the future (Spears et al., 2001). Thus, consumers in cultures low on Confucian dynamism are expected to react relatively poorly towards non-monetary promotions due to the delayed gratication involved (Foxman et al., 1988). Instead, they are expected to favour monetary promotions given the benets are more immediate and transactional. H5A. Monetary promotions are more effective for cultures low on the Confucian dynamism relative to cultures high on the Confucian dynamism. H5B. Non-monetary promotions are more effective for cultures high on the Confucian dynamism relative to cultures low on the Confucian dynamism. The ten hypotheses associated with the ve cultural dimensions are summarised in Figure 1. Each cultural dimension is considered one-by-one. The focus on single cultural dimensions provides a clear conceptual distinction that facilitates analysis and assists in the interpretation of results. The separate analysis of dimensions is consistent with past studies (Brodowsky and Anderson, 2000; Steenkamp et al., 1999; Zhang, 1997).

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

Journal of Product & Brand Management Volume 14 Number 3 2005 170 186

Figure 1 Summary of hypotheses

are selected as hedonic products. With the exception of biscuits, these product categories are the same as those studied by Chandon et al. (2000). This degree of replication helps to ensure consistency. The utilitarian and hedonic nature of the pre-selected product categories was pretested (see the Appendix). Within each of these product categories, brands of relevance to Australian consumers are selected. Furthermore, only brands with a high level of customerbased brand equity are used as the congruency effects are expected to be strongest for high equity brands. High equity brands tend to be well-known national brands with high market shares. These were identied from pretests based on the brands with the highest market shares in Australia for each product category, as reported by Retail World (Burton, 2001). Promotion stimuli Examples of monetary and non-monetary promotions are used as stimuli for both the pretests and the main experiment. The stimuli for monetary promotions are shelf-price discounts and price packs, and for non-monetary promotions they are sweepstakes and free gifts. Price packs are monetary promotions that offer savings through multiple packs (e.g. two for the price of one) or enlarged packs (e.g. contains 50 per cent more) (Tellis, 1998). It is appropriate to focus on these promotion techniques for several reasons. First, they correspond to those used in earlier research and thus, consistency can again be maintained (e.g. Dhar and Hoch, 1996; Huff and Alden, 1998). Second, they are commonly used in Australia and are also commonly observed for the pre-selected product categories. By contrast, alternatives such as coupons are inappropriate since coupon usage is relatively low in Australia. Loyalty programmes are also unsuitable given that there are few loyalty programmes for the product categories selected for this study. The nature of the pre-selected promotion techniques (i.e. monetary or non-monetary) was veried in a pretest (see the Appendix). Specic examples of the four promotion techniques are used in the main experiment. They are drawn from currently offered promotions in the product categories to ensure realism. This involved the use of a combination of secondary data and judgment. Specically, the examples are derived from reviews of weekly supermarket catalogues and from direct observations in supermarkets. Judgment is then applied to determine the most typical examples representing each promotion technique. Consideration is also given to the fact that monetary promotions will be preferred over

Measurement

The stimuli and measurement scales are presented in Table I. Sales promotion benets Sales promotion benets are dened and classied in this study according to the scale developed by Chandon et al. (2000). The scale indicates six main benets, which can be classied as either utilitarian or hedonic. Specically, the benets of savings, quality and convenience are classied as utilitarian, while the benets of value expression, exploration and entertainment are hedonic. A direct replication of these classications is appropriate as the scale has been shown to be valid and maintaining scale consistency can enhance the comparability of nal results with the original research (Churchill, 1979). A pretest was conducted to conrm the classication of benets in the Australian context (see the Appendix). The measures for the pretest were the same 18-item agree/disagree scales used in the original study. Product category and brand stimuli Utilitarian and hedonic products are listed as stimuli in the main experiment. In the past, researchers have used a variety of products to represent these two categories. For example, Hirschman and Holbrook (1982) suggested that washing machines and other durables are utilitarian products, whereas movies and fashion items are hedonic. Laundry detergent, AA batteries and lm are selected as utilitarian products, while chocolates, ice-cream and biscuits Table I Summary of measures

Item Sales promotion benets Product category stimuli Brand stimuli Promotion stimuli Culture Sales promotion effectiveness Measures/source

Area of application Pretest one Pretest two Main experiment Pretest two Main experiment Pretest one Main experiment Main experiment Main experiment

18-Item benet scale Three-item overall evaluation scale (Chandon et al., 2000) Four-item utilitarian index score (Batra and Ahtola, 1990) Secondary research (Burton, 2001) Secondary research 26-Item CVSCALE (Yoo et al., 2001) Brand choice (market shares)

174

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

Journal of Product & Brand Management Volume 14 Number 3 2005 170 186

non-monetary promotions of the same nominal value; this is because of the claim that consumers prefer immediate over delayed benets (dAstous and Jacob, 2002) and the greater effort required to secure the benets of non-monetary promotions. Thus, another criterion for identifying the examples of each promotion technique is that the nominal value of non-monetary promotions has to be greater than monetary promotions. Culture at an ethnic-group level Culture is measured using a personality-centred approach based on direct value inference (Lenartowicz and Roth, 1999). In particular, use is made of the CVSCALE proposed by Yoo et al. (2001). This is an adaptation of Hofstedes scale; it consists of 26 items, measured by ve-point Likert scales, relating to Hofstedes ve cultural dimensions (see Yoo and Donthu, 2002, Appendix B). It allows culture to be measured at the individual level and then aggregated to form groups at a chosen level for comparison. This is appropriate as it recognises that members of a society may not share the same cultural values (Au, 1999) and it also allows different ethnic groups within one country to be analysed. As suggested by Yoo et al. (2001), the CVSCALE is useful for analysing cultural values in a heterogeneous country and thus, the scale is particularly relevant for this study. Furthermore, the items of the scale have been adapted to suit the consumer context. This reduces the negative impact of using Hofstedes measures, which were based on work-related values. Finally, the reliability and validity of the CVSCALE have been shown to be robust in multiple studies across different samples, including validation studies involving both student and nonstudent respondents from America, Korea, Brazil and Poland (Yoo et al., 2001; Yoo and Donthu, 2002). Thus, there is strong evidence to support the use of this scale, and its reliability and validity is further tested in this study (see the Analysis section). Sales promotion effectiveness There are various ways to dene and measure the effectiveness of sales promotions. The measures typically used are short term, as sales promotions are mostly used to produce short-term effects. This includes measuring the effectiveness of sales promotions by sales volume (Dhar and Hoch, 1996), prots (Hoch et al., 1994) and consumer usage of the promotion (Babakus et al., 1988). However, it has been noted that a brands sales volume is by far the best measure of the performance of a sales promotion (Totten and Block, 1987). For the purposes of this study, the effectiveness of sales promotions is measured by market share, which is a proxy for sales volume. Market shares are calculated based on choices for promotion types, made under the conditions of the quasiexperiment. The effectiveness of sales promotions is then determined by a comparison between the choice shares of promotion types across different products. This is consistent with Chandon et al. (2000).

Methodology and pretests

The sample is described, followed by a summary of the pretests. Then the main experiment is introduced. 175

Samples Anglo-Australians and Chinese-Australians are selected for investigation. Both ethnic groups represent substantial and important market segments in Australia. The source countries of these two groups differ markedly in terms of Hofstedes (1991) cultural dimensions. Relatively, China is seen as: high power distance, low on uncertainty avoidance, collectivistic, feminine and high on the Confucian dynamism, whereas Australia is characterised as: low power distance, high on uncertainty avoidance, individualistic, masculine and low on the Confucian dynamism. While these differences are found at the broad national level, it is also expected that they will be evident at an ethnic level and hence facilitate the testing of the hypotheses. Previous studies of Anglo-Australians and ChineseAustralians, and similar work among North-Americans and Canadian-Chinese, support this belief (Bochner and Hesketh, 1994; Doran, 1994). However, rather than merely rely on previous studies, the differences between the two ethnic groups are derived empirically in the present study (see the Analysis section). The samples are controlled for non-cultural confounding factors. As Foxman et al. (1988) pointed out, both macroeconomic and socio-demographic factors can affect consumers of different cultures in their responses to sales promotions. Macroeconomic factors, such as the level of national economic activity, are effectively controlled by examining only one country, and thus these factors can be treated as constants. With regard to socio-demographic factors, common characteristics considered in cross-cultural studies of sales promotion include age, gender, income and the level of education. These either have been treated as covariates (Steenkamp et al., 1999) or controlled via matched sampling (Green, 1995). A mixed approach is adopted here. First, in terms of matching, the samples are restricted to undergraduate students. Students are ethnically diverse but in many other respects they are reasonably homogeneous, thereby reducing the impact of extraneous factors (Calder et al., 1981). For all the products studied, students are consumers, and there are no reasons to suppose students will systematically respond differently than others to sales promotions. Second, the factors of gender, age and income are treated as covariates. Although gender and age were not found to be a signicant factor by Chandon et al. (2000), they remain important to examine as gender and age differences in consumer behaviour are possible, particularly across different cultures and ethnic groups (Usunier, 2000). Income is also considered a covariate, although students tend to be relatively homogeneous in this respect and any potential impact is expected to be minimal (Durvalsula et al., 1993). In terms of recruitment, a self-identication process is used to determine the ethnicity of respondents (note: this is merely a screening exercise, respondents do not self-select into treatment conditions). This involves asking respondents to self-identify their ethnicity based on prompts such as AngloAustralians, including Anglo-Saxons and Anglo-Celtics. Respondents that identify themselves as neither AngloAustralian nor Chinese-Australian are excluded from analysis. Self-identication is believed to be more relevant for selecting sub-cultures within a country than other popular measures, such as the country of citizenship (Bochner and Hesketh, 1994). Self-identication represents a persons

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

Journal of Product & Brand Management Volume 14 Number 3 2005 170 186

. .

internal beliefs and hence is said to reect a persons cultural reality (Hirschman, 1981). However, despite the validity of self-identication, it may be confounded with the effect of acculturation (i.e. the extent of assimilation of a new culture by an ethnic minority). It has been suggested that the level of acculturation can determine an individuals commitment to the cultural norms of his or her ethnic group (Hirschman, 1981). To permit analysis of this factor, respondents were asked to state their country of birth and the length of time they had lived in Australia (following scales suggested by Quester et al. (2001)). Pretests Two pretests were completed (see the Appendix). The rst pretest was designed to conrm the nature of the promotion techniques, and verify the relationships between monetary and non-monetary promotions with utilitarian and hedonic benets respectively. Short self-administered questionnaires were completed by a random sample of 15 Anglo-Australian and 15 Chinese-Australian students. Results conrmed that shelf-price discounts and price packs can be classied as monetary promotions, with sweepstakes and free gifts as nonmonetary promotions. They also showed that positive relationships exist between monetary and non-monetary promotions with utilitarian and hedonic benets respectively. These results largely replicated the ndings of Chandon et al. (2000). The second pretest was designed to verify the utilitarian and hedonic nature of the pre-selected product categories that are used for the main experiment. It also sought to identify specic brands that are representative of high equity brands in each of the product categories. Using a new random sample of 15 Anglo-Australians and 15 Chinese-Australian, batteries and lm were shown to be utilitarian products and chocolates and ice-cream as hedonic products. Brands with which respondents had most experience, in terms of frequency of purchase, were Energiser (batteries), Kodak (lm), M&Ms (chocolates) and Peters (ice-cream). Main experiment The main experiment consists of a self-administered questionnaire, which is designed to test the validity of the CVSCALE and test the ve pairs of hypotheses listed earlier. The questionnaire was pilot tested. In the main experiment, two versions were used to test for ordering effects. After a brief introduction in undergraduate classes, without disclosing the purpose of the questionnaire, participation was sought on a voluntary basis. Screening for ethnicity did not occur at this stage. Instead all students were invited to participate. The questionnaire took about 10 to 15 minutes to complete and almost all students choose to participate across all classes. No incentives were offered it was felt that in a study about sales promotion the offer of incentives might bias results (this contrasts with Chandon et al. (2000)). Respondents were randomly assigned one of the two versions of the questionnaire. For both versions, respondents were asked to: . Choose between options A and B for two utilitarian and two hedonic products (Option A was a brand associated with a monetary promotion while option B was the same brand but associated with a non-monetary promotion). . Provide past purchase information for the products and brands involved. 176

Complete the CVSCALE items. Complete demographic questions including gender, age, income, ethnicity and acculturation.

It should be noted that Chandon et al. (2000) differed slightly in their research design as they asked respondents to evaluate two different brands within each product category. However, only one brand is used for this study so as to strengthen the promotion manipulations; by asking respondents to choose between two types of promotions for the same brand, any branding effects are eliminated and the focus is on purepromotional effects. Prices were omitted from the earlier study here they are listed, but not manipulated this was simply to add realism to the scenarios.

Analysis

Descriptive analyses are presented, followed by an analysis of the CVSCALE and then the presentation of the main results. Descriptive analysis Some 250 questionnaires were completed by AngloAustralians or Chinese-Australians (with an equal split between the two groups). Almost half of the sample was born overseas with Hong Kong (16 per cent), China (8 per cent) and Indonesia (5 per cent) being the most common countries of birth. On average, respondents had lived in Australia for 15 years. Demographically the two groups are closely matched, although Anglo-Australians are somewhat older on average and have a slightly higher level of income. With regard to past purchasing behaviour, most respondents have bought the four product categories examined in the past 12 months (batteries 80 per cent, lm 81 per cent, chocolate 98 per cent and ice cream 95 per cent). Past purchases were also relatively high at the brand level (Energiser 64 per cent, Kodak 77 per cent, M&Ms 78 per cent and Peters 58 per cent). While there are some differences between the two ethnic groups (ice-cream, M&Ms and Peters; p , 0:05), the percentages of past purchases remain relatively high across all products and brands for each ethnic group. This suggests that respondents have sufcient knowledge and purchase experience of the products and brands involved, and it is reasonable to assume they are able to make informed evaluations of the different promotional options. CVSCALE analysis Responses to the CVSCALE are used to determine the relative cultural values of both ethnic groups on the ve cultural dimensions. However, rst the reliability and validity of the CVSCALE is tested. For the whole sample, the reliability alpha of the cultural dimensions ranged from 0.60 to 0.69 (Table II). There was slight variation between the ethnic groups, but in only one case did the reliability alpha fall below 0.6 (0.54 for masculinity among Anglo-Australians). Although these results are modest, they are comparable to those reported by Yoo et al. (2001) and they satisfy the reliability threshold of 0.6 that is commonly accepted for new scales (Hair et al., 1998). Checks show there are no ordering effects. After reliability testing, factor analysis was used to ascertain the validity of the items. Under the specication of ve factors, the results of exploratory factor analysis provide preliminary support for the CVSCALEs validity. With one exception, all the items loaded highly on the appropriate

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

Journal of Product & Brand Management Volume 14 Number 3 2005 170 186

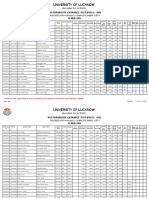

Table II Reliability analysis results

Dimension Power distance Uncertainty avoidance Collectivism Masculinity Confucian dynamism Whole sample 0.65 0.64 0.67 0.60 0.69 Anglo-Australians 0.69 0.67 0.61 0.54 0.68 Chinese-Australians 0.62 0.61 0.70 0.67 0.69 Yoo et al. (2001) 0.61 0.71 0.76 0.67 0.69

factors and no item loaded on more than one factor. Overall, therefore, the results support the independence of the constructs. Furthermore, the ve factors explained 45 per cent of the total variance, which exactly matches the gure reported by Yoo et al. (2001). Conrmatory factor analysis was then employed to validate the scale in regard to specic constructs. The measurement model is based on the same specications as Yoo et al. (2001), with ve factors and 26 items, where each item loaded on only one factor and the factors are uncorrelated. Using AMOS 4.0, the overall t of the measurement model was excellent: x2 df 299 543:32; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) 0.06; normed t index NFI 0:97; comparative t index CFI 0:99; and incremental t index IFI 0:99. These results provide strong conrmatory support for the CVSCALE and its use in studying the hypothesised constructs. With regard to composite reliability, all the estimates were above the recommended level of 0.70, ranging from 0.79 to 0.85. These results are evidence of the scales convergent validity. In addition, whilst the average variance extracted for each dimension was only moderate at 0.50, they satisfy the minimum acceptable levels (Hair et al., 1998). Thus, the results provide support for the independence of the dimensions (Fornell and Larker, 1981). Having conrmed the reliability and validity of the CVSCALE, responses to the scale are aggregated for analysis. An average score for each cultural dimension is computed for each ethnic group. The score is calculated as the average of the individual items of each cultural dimension answered by the respondents of each ethnic group (e.g. if there are ve items for the power distance dimension and 25 respondents for each ethnic group, the average for each ethnic group is S [25 5 items scores]/25). This approach reects the exibility of the CVSCALE in that it allows culture to be measured at the individual level but analysed at an appropriate aggregate level. Thus, individual respondents may differ from the average of their group but will remain appropriate for analysis. The average scores are compared to classify the relative cultural values of the two ethnic groups on each dimension (Table III). Although the absolute differences are small, based on conventional statistical standards there are signicant differences between the two ethnic groups on all of the cultural dimensions (p , 0:05), except for uncertainty avoidance. Using the relative averages, Anglo-Australians can be classied as relatively low power distance, low on uncertainty avoidance, individualistic, feminine and low on Confucian dynamism, and vice versa for Chinese-Australians. The classications largely conform to Hofstedes (1991) results. The exceptions are the contrary results on uncertainty avoidance and masculinity. However, arguably some 177

inconsistency is to be expected given the distinctiveness of the CVSCALE the purpose of using the CVSCALE is to provide a more appropriate measure of culture and to avoid some of the limitations of earlier scales such as Hofstedes. Moreover, the hypotheses involve a comparison of cultures dened only by cultural dimensions. There are no restrictions regarding how Anglo-Australians or Chinese-Australians should score on each dimension. Thus, the hypotheses involving masculinity can be tested using Anglo-Australians as the feminine culture and Chinese-Australians as the masculine culture. Analysis procedures In order to examine each hypothesis, the results of the experiment are analysed using two main procedures. First, logistic regression is used to test for congruency between product and promotion types. The dependent variable is the choice between promotion type (monetary or non-monetary) and the independent variables are product type (i.e. utilitarian or hedonic) and the covariates of gender, age and income. Second, choice shares of promotion types are analysed to identify any differences in the choices between ethnic groups. Analysis is undertaken at an ethnic-group level and an individual level, and across different acculturation groupings Main results at an ethnic-group level In testing the hypotheses, the data were analysed at an ethnic level. The ethnic groups are already classied on each cultural dimension as shown in Table III. For the purposes of analysis, the upper-median-splits within each ethnic group on each cultural dimension are used. This results in greater variance between the two groups on the dimensions of interest. Logistic regression analysis is performed on each ethnic group for each dimension. Thus, a total of ten regressions were conducted (Table IV). Results show that the regression models generally have a poor t since the reduction in the 2 2 log likelihood values and the R2 values are relatively low. However, the omnibus test of model coefcients indicates that coefcients were signicant for ve of the models (p , 0:05). Within the signicant models, product type was consistently shown to have a signicant and negative relationship with promotion type: high power distance (B 21:60, p 0:00), high uncertainty avoidance (B 21:33, p 0:00), collectivist (B 20:96, p 0:00), masculine (B 21:38, p 0:00) and high Confucian dynamism (B 21:06, p 0:00). These results indicate that for each signicant dimension, hedonic products are associated with the choice of monetary promotions and utilitarian products are associated with the choice of non-monetary promotions. Generally, the covariates of gender, age and income were found to be insignicant. The only exception is that higher income was found to be associated with the choice of non-monetary promotions under the collectivist dimension (B 1:29, p 0:04).

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

Journal of Product & Brand Management Volume 14 Number 3 2005 170 186

Table III Average cultural scores

Power distance Anglo-Australians Chinese-Australians 4.05 Relatively low 3.88 Relatively high 2.49 0.01 Uncertainty avoidance 2.16 Relatively low 2.07 Relatively high 1.40 0.16 Collectivism 2.99 Relatively individualistic 2.78 Relatively collectivistic 2.96 0.00 Masculinity 3.28 Relatively feminine 3.03 Relatively masculine 3.16 0.00 Confucian dynamism 2.11 Relatively low 1.91 Relatively high 3.22 0.00

T-value Sig. P-value

Table IV Logistic regression results at an ethnic-group level

Dependent variable promotion type (model summary) 2 2 Log likelihood R2 value Omnibus test of model coefcients Low PD-Anglo High PD-Chinese Low UA-Anglo High UA-Chinese Individualist-Anglo Collectivist-Chinese Feminine-Anglo Masculine-Chinese Low CD-Anglo High CD-Chinese 223 (226)b 218 (242) 238 (242) 241 (261) 261 (266) 244 (258) 241 (242) 216 (236) 255 (261) 236 (250)

a

Independent variables Product type Gender Age 2 0.23 (0.50)d 2 1.60 (0.00) 2 0.48 (0.15) 2 1.33 (0.00) 2 0.28 (0.36) 2 0.96 (0.00) 2 0.16 (0.63) 2 1.38 (0.00) 2 0.39 (0.22) 2 1.06 (0.00) 0.64 (0.08) 0.39 (0.27) 0.55 (0.88) 2 0.15 (0.65) 0.30 (0.36) 0.30 (0.35) 0.16 (0.67) 0.41 (0.25) 0.59 (0.07) 0.35 (0.30) 0.15 (0.69) 2 0.17 (0.66) 0.09 (0.79) 2 0.16 (0.64) 2 0.22 (0.50) 2 0.07 (0.85) 2 0.05 (0.88) 2 0.15 (0.70) 2 0.07 (0.85) 2 0.26 (0.46)

Income 2 0.31 (0.46) 0.58 (0.18) 0.47 (0.18) 0.64 (0.10) 0.61 (0.07) 1.29 (0.04) 0.14 (0.71) 0.78 (0.09) 0.23 (0.50) 0.61 (0.10)

0.03 0.15 0.03 0.12 0.03 0.09 0.01 0.12 0.03 0.09

0.43

0.00

0.42

0.00

0.28

0.00

0.95

0.00

0.25

0.00

Notes: a Model 2 2 log likelihood; b Initial 2 2 log likelihood; c Nagelkerke R2; d Signicance value

The choice share results for each ethnic group on each dimension are shown in Table V. The results are reective of the regression ndings, in that hedonic products have a relatively higher choice share of monetary promotions than utilitarian products. Another key result is that for each ethnic split, monetary promotions are preferred over non-monetary promotions across all products and for each product type. The choice share results provide a means to evaluate the hypotheses. Independent t-tests were used to test for differences in the mean preference of promotion type between the two ethnic groups within each dimension. There was no signicant difference in the choice shares between ethnic groups across all products (Table V). Within product types, differences were found in only two out of the possible ten cases. First, for utilitarian products, there was a signicant difference in the choice of promotion type between the two ethnic groups under the power distance dimension (p , 0:05). Specically, low power distance Anglo-Australians were found to have a higher preference for monetary promotions than high power distance Chinese-Australians (81 per cent vs 70 per cent). This is in line with the prediction of hypotheses H1A and H1B. Second, for hedonic products, a signicant difference was found under the masculinity 178

dimension (p , 0:05). It is evident that Feminine AngloAustralians have a lower preference for monetary promotions than masculine Chinese-Australians (82 per cent vs 91 per cent). This is consistent with H4A and H4B. However, these were the only instances where differences were found. In general, there was no difference in the choice shares between the two ethnic groups across all products and product types, despite differences in cultural values. Thus, there is insufcient evidence to support the hypotheses of this study. The results were conrmed when the same analyses were performed with upper-quartile-split samples. This produced even greater variance in the cultural values between ethnic groups, but no signicant differences in choice shares were observed. Main results at an individual level In order to provide further understanding, the data were also analysed at an individual level. Specically, median splits were conducted on each dimension based on the scores of all individuals, regardless of their ethnic background. The two groups on each dimension were analysed using the same logistic regression model as before. Results generally reect those found at the ethnic level (Table VI). First, the

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

Journal of Product & Brand Management Volume 14 Number 3 2005 170 186

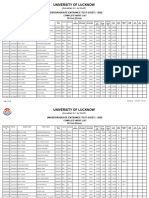

Table V Choice shares at an ethnic-group level

All products Monetary non-monetary promotions utilitarian products 81-19 70-30 (0.03) 76-24 66-34 (0.10) 75-25 71-29 (0.52) 80-20 73-27 (0.16) 75-25 72-28 (0.52) Hedonic products 85-15 92-8 (0.07) 82-18 89-11 (0.33) 80-20 86-14 (0.16) 82-18 91-9 (0.04) 82-18 88-12 (0.15)

Power distance Low-Anglo (%) High-Chinese (%) (Sig. p-value) Uncertainty avoidance Low-Anglo (%) High-Chinese (%) (Sig. p-value) Collectivism Individualist-Anglo (%) Collectivist-Chinese (%) (Sig. p-value) Masculinity Feminine-Anglo (%) Masculine-Chinese (%) (Sig. p-value) Confucian dynamism Low-Anglo (%) High-Chinese (%) (Sig. p-value)

83-17 81-19 (0.56) 79-21 78-22 (0.44) 78-22 79-21 (0.75) 81-19 82-18 (0.82) 78-22 80-20 (0.67)

Note: Choice shares for monetary promotions are quoted rst and non-monetary promotions quoted second (e.g. in the rst cell low power distance the choice share for monetary promotions is 83 per cent and for non-monetary promotions it is 17 per cent)

Table VI Logistic regression results at an individual level

Dependent variable promotion type (model summary) 2 2 Log likelihood R2 value Omnibus test of model coefcients Low power distance High power distance Low uncertainty avoidance High uncertainty avoidance Individualist Collectivist Feminine Masculine Low Confucian dynamism High Confucian dynamism 474 (483)b 509 (524) 479 (489) 505 (519) 491 (503) 497 (506) 484 (492) 500 (517) 497 (506) 494 (503)

a

Independent variables Product type Gender Age

Income 2 0.02 (0.93) 0.03 (0.89) 2 0.09 (0.71) 0.15 (0.52) 0.11 (0.65) 2 0.04 (0.88) 0.15 (0.54) 2 0.09 (0.72) 0.08 (0.74) 0.10 (0.66)

0.03 0.05 0.03 0.04 0.04 0.03 0.03 0.05 0.04 0.03

0.06

0.01 0.05 0.01 0.01

0.06 0.10

0.00 0.01 0.05

2 0.54 (0.02)d 2 0.85 (0.00) 2 0.58 (0.01) 2 0.81 (0.00) 2 0.74 (0.00) 2 0.65 (0.00) 2 0.50 (0.03) 2 0.89 (0.00) 2 0.71 (0.00) 2 0.68 (0.00)

0.48 (0.06) 0.03 (0.91) 0.40 (0.10) 0.09 (0.69) 0.33 (0.18) 0.18 (0.43) 0.41 (0.14) 0.10 (0.67) 0.47 (0.05) 0.07 (0.75)

0.17 (0.50) 2 0.15 (0.53) 0.24 (0.33) 2 0.23 (0.32) 0.02 (0.93) 2 0.03 (0.88) 0.16 (0.49) 2 0.19 (0.45) 0.12 (0.63) 2 0.11 (0.65)

Notes: a Model 2 2 log likelihood; b Initial 2 2 log likelihood; c Nagelkerke R2; d Signicance value

reduction in the 2 2 log likelihood values and the R2 values for each regression are again relatively low, suggesting a poor t for all the models. However, with the exception of the collectivist dimension, model coefcients were found to be signicant for the same dimensions identied at the ethnic 179

level (p , 0:05). Similarly, product type was consistently shown to have a signicant and negative relationship with promotion type: high power distance (B 2 0.85, p 0.00), high uncertainty avoidance (B 20:81, p 0:00), masculine ( B 20:89, p 0:00) and high Confucian dynamism

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

Journal of Product & Brand Management Volume 14 Number 3 2005 170 186

(B 20:68, p 0:00). These results conrm the ndings at the ethnic level that hedonic products are associated with the choice for monetary promotions. Once again, the covariates were generally found to be insignicant, although under the low Confucian dynamism dimension female responses were positively related with the choice of non-monetary promotions (B 0:47, p 0:05). Choice share results for each dimension at an individual level show that hedonic products are associated with a higher choice share of monetary promotions (Table VII). The preference for monetary promotions also dominates across all products and for each product type. In addition, across all products and for each product type, no signicant difference was found in the choice shares between the groups on each dimension. Acculturation analysis The effects of acculturation are explored by dividing the sample of Chinese-Australian respondents using a median split based on the number of years that respondents have lived in Australia and, in a separate analysis, based on whether the respondent was born in Australia or overseas. These two splits are seen as different ways to examine the same underlying dimension of acculturation (Quester et al., 2001). The four groups were analysed using logistic regression (Table VIII). The results are fairly consistent across all groups. First, all the models had relatively poor t, as shown by the small reductions in the 2 2 log likelihood value and the low R 2 values. Second, the model coefcients were insignicant for all groups, except the negative relationship with promotion type. The choice share results for the four groups are shown in Table IX. These results are consistent with those reported for Table VII Choice shares at an individual level

All products

Chinese-Australians in the earlier analyses (Tables V and VII). Firstly, the choice for monetary promotions was found to dominate non-monetary promotions. Second, hedonic products were found to be associated with monetary promotions. The results were consistent across all groups, and no signicant difference in choice shares was observed, suggesting that acculturation does not have an impact on the ndings of this study.

Summary and management implications

The key ndings and contributions of the study are summarised for three main areas: 1 consumer cultural values and ethnicity; 2 culture at the ethnic-group level and sales promotion; and 3 culture at this level and the congruency framework. Consumer cultural values and ethnicity Cross-cultural studies often assume cultural differences exist at an ethnic-group level, rather than directly measure and demonstrate these differences (Laroche et al., 2002). By contrast, the current study provides empirical evidence to conrm the popular assumption. It also further validates the CVSCALE and shows its exibility. This, in fact, might be a more relevant scale with which to work in consumer research than Hofstedes (even where his dimensions are being used). The message here for product managers is it is important to appreciate the clear differences in cultural values that may exist among consumers at an ethnic-group level. As we have found, mean scores between Anglo-Australians and ChineseAustralians are signicantly different from each other across all-but-one cultural dimension (the exception being uncertainty avoidance).

Monetary non-monetary promotions Utilitarian products 77-23 71-29 (0.13) 76-24 72-28 (0.26) 74-26 74-26 (0.92) 77-23 72-28 (0.19) 74-26 74-26 (0.92)

Hedonic products 85-15 85-15 (1.00) 85-15 85-15 (1.00) 86-14 85-15 (0.80) 84-16 86-14 (0.62) 85-15 85-15 (1.00)

Power distance Low (%) High (%) (Sig. p-value) Uncertainty avoidance Low (%) High (%) (Sig. p-value) Collectivism Individualist (%) Collectivist (%) (Sig. p-value) Masculinity Feminine (%) Masculine (%) (Sig. p-value) Confucian Dynamism Low (%) High (%) (Sig. p-value)

81-19 78-22 (0.24) 81-19 79-21 (0.39) 80-20 80-20 (0.94) 81-19 79-21 (0.48) 80-20 80-20 (0.94)

Note: Choice shares for monetary promotions are quoted rst and non-monetary promotions quoted second (e.g. in the rst cell low power distance the choice share for monetary promotions is 81 per cent and for non-monetary promotions it is 19 per cent)

180

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

Journal of Product & Brand Management Volume 14 Number 3 2005 170 186

Table VIII Logistic regression results using acculturation splits

Dependent variable promotion type (model summary) 2 2 Log likelihood R2 value Omnibus test of model coefcients Years in Australia low Years in Australia high Overseas born Australia born 219 (230)b 236 (258) 342 (368) 113 (121)

a

Independent variables Product type Gender Age

Income 0.44 (0.32) 0.35 (0.33) 0.35 (0.28) 0.47 (0.36)

0.07 0.13 0.10 0.10

0.03 0.00 0.00

0.10

2 1.01 (0.01)d 2 1.53 (0.00) 2 1.31 (0.00) 2 1.20 (0.01)

0.44 (0.21) 0.05 (0.89) 0.39 (0.17) 2 0.44 (0.45)

2 0.02 (0.92) 0.10 (0.79) 0.03 (0.92) 2 0.47 (0.43)

Notes: a Model 2 2 log likelihood; b Initial 2 2 log likelihood; c Nagelkerke R2; d Signicance value

Table IX Choice shares for using acculturation splits

All products Monetary non-monetary promotions Utilitarian products 76-24 67-33 (0.12) 72-28 69-31 (0.61) Hedonic products 90-10 90-10 (0.83) 90-10 88-12 (0.55)

Years lived in Australia Few (%) Many (%) (Sig. p-value) Country of birth Overseas (%) Australia (%) (Sig. p-value)

83-17 79-21 (0.26) 82-18 78-22 (0.46)

Notes: Choice shares for monetary promotions are quoted rst and non-monetary promotions quoted second (e.g. in the rst cell few years lived in Australia the choice share for monetary promotions is 83 per cent and for non-monetary promotions it is 17 per cent)

Culture at the ethnic-group level and sales promotion Another key contribution of the study is that despite differences in cultural values between ethnic groups, generally there is no signicant difference in their preferences for sales promotion types. With only two exceptions, this result is found to be consistent at an ethnicgroup level across all products and for each product type. The absence of cultural effects is also evident when analysis is undertaken at an individual level. Clearly, differences in cultural values do not necessarily give rise to differences in preferences and choices. The management implications of this nding are twofold. First, although differences in cultural values may exist, these do not necessarily impact consumer responses to sales promotions at an ethnic level. This suggests that managers can use standardised sales promotions, even when targeting different ethnic groups an approach that is likely to be simpler and cheaper than localised and heavily differentiated strategies. Second, the nding draws attention to the fact that cultural distinctions may be more relevant in some areas of marketing than others. Previous studies, for example, show that the distinction between collectivism and individualism accounts for differences in consumer complaining behaviour (Watkins and Liu, 1996) but is not a factor in assessing advertising appeals (Cutler et al., 1997). Thus, it would be a mistake to assume that differences in cultural values will necessarily affect all aspects of marketing in some cases they will not. 181

Culture at the ethnic-group level and the congruency framework There are mixed ndings in regard to the congruency framework of sales promotion effectiveness. First, the preference for monetary promotions was found to dominate over the preference for non-monetary promotions across all product types. Furthermore, with only a few exceptions, the covariates of gender, age and income were all insignicant in accounting for the choice of promotions. All of this is consistent with Chandon et al.(2000). Furthermore, these results were evident across all cultural groups at all levels of analysis and thus the impact of culture appears to be minimal here. For management this again suggests standardisation strategies might be effective under certain circumstances. Interestingly, the direction of congruency effects between product and promotion types was opposite to that described by Chandon et al. (2000). In the current study, hedonic products were associated with the choice of monetary promotions while utilitarian products were associated with non-monetary promotions. Wang (2004) too has reported results that seemingly contradict some aspects of the original study. The fact that results might differ across studies suggests that product managers must exercise considerable caution when applying the congruency framework it is possible a range of factors will affect the direction of the congruency relationships and these factors need to be teased out. For instance, a possible explanation for our results is that nonmonetary promotions are preferred for utilitarian products

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

Journal of Product & Brand Management Volume 14 Number 3 2005 170 186

because they provide consumers with the experiential benets that are not provided by the product itself. Anecdotally, this is supported by the use of non-monetary promotions for some utilitarian products, such as the loyalty programme for Unilevers Omo laundry detergent and online competitions for Kelloggs Coco Pops. On the other hand, monetary promotions may be preferred for hedonic products because they can reduce the guilt associated with hedonic consumption (Kivetz and Simonson, 2002). Something similar occurs when charitable donations are examined: donations are more likely when tied to the purchase of (hedonic) luxuries than to (utilitarian) necessities (Strahilevitz and Myers, 1998). Managers need to think through implications such as these before making assumptions about the direction of congruency effects.

and McCullough, 1985). These themes deserve further consideration. There are likely to be a range of factors having an impact on the congruency framework and the effectiveness of sales promotions. For example, the role of guilt was mentioned earlier and the nature of the decision might also have an inuence (Dhar and Wertenbroch, 2000). Furthermore, the current study only focused on consumer promotions and consumer packaged goods. Congruency effects and the impact of culture and ethnicity may apply in different ways for business-to-business trade promotions and in other types of product categories (e.g. services and industrial products). All of these areas represent opportunities for future research that can help extend our knowledge of sales promotion effectiveness.

Further research

In terms of the methodology, a quasi-experimental design is adopted here. This is only one of the many possible methodologies that might be used. An alternative would be to observe the choice behaviour of consumers at the point of purchase. This would capture choice behaviour directly, although then it might be harder to determine the ethnicity of consumers. Another alternative is to use scanner data to measure brand choice, as in previous studies of consumer sales promotions (Ehrenberg et al., 1994; Mela et al., 1997). Typically, this would be accompanied by a usage and attitude questionnaire, which could provide demographic, ethnographic and acculturation information. Other measures and stimuli might be employed. For example, culture might be measured using an alternative scale (e.g. Furrer et al., 2000) and the results compared with the CVSCALE to provide a form of triangulation. Another possible methodological extension would be to present the promotion scenarios with pictorial aids. The pictorial presentation of both the product and promotional offer may have an impact on consumer responses to the sales promotion scenarios in the quasi-experimental setting. Finally, the generalisability of the results could be extended by considering other monetary and non-monetary promotions (e.g. coupons, loyalty schemes), and by broadening the list of utilitarian and hedonic products (e.g. other packaged goods or services). This is particularly important given the variety of promotional types now employed across a diverse range of products categories. It would also be worthwhile to explore the responses of other cultural groups within and across a variety of countries (e.g. Italian-Australians, KoreanAustralians, North African-French, Hispanic-Americans, etc.). A number of empirical extensions are recommended. For instance, it has been suggested that consumer responses to brands (McCort and Malhotra, 1993) and prices (Laroche et al., 2002) can differ across cultures. Therefore, it would be worthwhile to explore branding and pricing effects along with the impact of culture and ethnicity on consumer sales promotions. Acculturation is considered briey in this study, but it could be developed as a theme in its own right. So too could the question of how people perceive themselves, in terms of their ethnicity. For example, there is evidence suggesting that people may see themselves belonging to more than one ethnic group and that the strength of identication with a particular group may differ between its members (Tan 182

References

Aaker, J.L. and Maheswaran, D. (1997), The effect of cultural orientation on persuasion, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 24, December, pp. 315-28. Albaum, G. and Peterson, R.A. (1984), Empirical research in international marketing, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 15, Spring/Summer, pp. 161-73. AMA (2003), 2003 directory of multicultural marketing rms, Marketing News, 1 September. Au, K.Y. (1999), Intra-cultural variation: evidence and implications for international business, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 30 No. 4, pp. 798-813. Babakus, E., Tat, P.K. and Cunningham, W. (1988), Coupon redemption: a motivational perspective, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 37-43. Babin, B.J., Darden, W.R. and Grifn, M. (1994), Work and/or fun? Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 20, March, pp. 644-56. Batra, R. and Ahtola, O.T. (1990), Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of consumer attitudes, Marketing Letters, Vol. 2 No. 2, pp. 159-70. Bochner, S. and Hesketh, B. (1994), Power distance, individualism/collectivism, and job-related attitudes in a culturally diverse work group, Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, Vol. 23, June, pp. 233-57. Bridges, E., Florsheim, R. and Claudette, J. (1996), A crosscultural comparison of response to service promotion, The Service Industries Journal, Vol. 16, July, pp. 265-87. Brodowsky, G.H. and Anderson, B.B. (2000), A crosscultural study of consumer attitudes toward time, Journal of Global Marketing, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 93-109. Burton, D. (2001), 2001 Annual Report: market sizes and shares, Retail World, December, pp. 33-75. Calder, N.J., Phillips, L.W. and Tybout, A.M. (1981), Designing research for application, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 8, September, pp. 197-207. Chandon, P., Wansink, B. and Laurent, G. (2000), A benet congruency framework of sales promotion effectiveness, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 64, October, pp. 65-81. Churchill, G.A. (1979), A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 16, February, pp. 64-73. Cutler, B.D., Erdem, S.A. and Javalgi, R.G. (1997), Advertisers relative reliance on collectivism-

Sales promotion effectiveness: the impact of consumer differences Simon Kwok and Mark Uncles

Journal of Product & Brand Management Volume 14 Number 3 2005 170 186

individualism appeals: a cross-cultural study, Journal of International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 9 No. 3, pp. 43-55. DAstous, A. and Jacob, I. (2002), Understanding consumer reactions to premium-based promotional offers, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 36 Nos. 11-12, pp. 1270-86. Dawar, N. and Parker, P. (1994), Marketing universals: consumers use of brand name, price, physical appearance, and retailer reputation as signals of product quality, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 58, April, pp. 81-95. Dhar, R. and Wertenbroch, K. (2000), Consumer choice between hedonic and utilitarian goods, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 37, February, pp. 60-71. Dhar, S.K. and Hoch, S.J. (1996), Price discrimination using in-store merchandising, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 60 January, pp. 17-30. Doran, K.B. (1994), Exploring cultural differences in consumer decision making: Chinese consumers in Montreal, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 21, pp. 318-22. Dowling, G.R. and Uncles, M. (1997), Do customer loyalty programs really work?, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 38, Summer, pp. 71-82. Durvalsula, S., Andrews, J.C., Lysonski, S. and Netemeyer, R.G. (1993), Assessing the cross-national applicability of consumer behaviour models: a model of attitude toward advertising in general, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 19 March, pp. 626-36. Ehrenberg, A.S.C., Hammond, K. and Goodhardt, G.J. (1994), The after-effects of price-related consumer promotions, Journal of Advertising Research, July-August, pp. 11-21. Fletcher, R. and Brown, L. (1999), International Marketing: An Asia-Pacic Perspective, Prentice-Hall, Sydney. Fornell, C. and Larker, D.F. (1981), Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18, February, pp. 39-50. Foxman, E.R., Tansuhaj, P.S. and Wong, J.K. (1988), Evaluating cross-national sales promotion approach strategy: an audit approach, International Marketing Review, Vol. 5, Winter, pp. 7-15. Furrer, O., Shaw-Ching Liu, B. and Sudharshan, D. (2000), The relationship between culture and service quality perceptions, Journal of Services Research, Vol. 2 No. 4, pp. 355-71. Goodenough, W.H. (1971), Culture, Language and Society, Modular Publications, Reading, MA. Green, C.L. (1995), Differential responses to retail sales promotion among African-American and Anglo-American consumers, Journal of Retailing , Vol. 71, Spring, pp. 83-92. Gurhan-Canli, Z. and Maheswaran, D. (2000), Cultural variations in country-of-origin effects, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 37, August, pp. 309-17. Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L. and Black, W.C. (1998), Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed., Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Hirschman, E.C. (1981), American Jewish ethnicity: its relationship to some selected aspects of consumer behavior, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 45, Summer, pp. 102-10. Hirschman, E.C. and Holbrook, M.B. (1982), Hedonic consumption: emerging concepts, methods and 183