Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Bill Dietz - Benjamin Patterson's Lost PETs

Загружено:

Margarita LopezАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Bill Dietz - Benjamin Patterson's Lost PETs

Загружено:

Margarita LopezАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Benjamin Pattersons Lost PETs

Bill Dietz

It seems almost ominous that the last work in The Black & White File (the 1999 primary collection of scores and instructions for [Benjamin Pattersons] music, events, operas, performances and other projects: 19581999) preceding B.P.s temporary retirement from art into life (the work is Seminar II, an environment of challenge, from 1965) is prefaced by Notes on PETs (acronym for Perception Education Tools), a text which not only formulates a theoretical framework for his activities to that date starkly contrasting the general Fluxus framework within which his work is now almost exclusively understood, but which also goes so far as to offer PET-oriented interpretive thumbnails of his own works in marked contradistinction to the orthodoxies of that then-burgeoning neoavant-garde movement. Fluxus appears only in an endnote to the text, subordinately, as one possibility of the phenomenon it describes. Because these Notes are is apparently so unknown as to have escaped the extant Patterson literature, a summarizing selection (the entire text is reproduced following this article): I require that the central function of the artist be a duality of discoverer and educator: discoverer of the varying possibilities for selecting from environmental stimuli specic percepts and organizing these into signicant perceptions, and concurrently, as an educator, training a public in the ability to perceive in newly discovered patterns. [] art objects [] are in the rst order not aesthetic objects, but educational tools. [] Each style is actually a by-product of a new discovery of how percepts stimulated by the envir-

onment may be selected and organized to obtain visual signicance (i.e., enter into a critical relationship with the individuals previous comprehension of the environment). In this light, what now seem to be held as the greatest hits of B.P.s early period, works like PAPER PIECE (1960) and the licking piece from methods & processes (1962), appear as rather spectacular exceptions in the trajectory the artist himself was seeking to articulate. By the time methods & processes is published, all manner of training and exercise modes appropriate to the formulation of PETs are apparent: tournaments, studies, questionnaires, seminars, demonstrations at the chalkboard, examinations. Asserting this interpretive distinction now is not meant to deemphasize the signicance of a work such as PAPER PIECE , but to ask how understanding PAPER PIECE as an at least nascent form of PET might change our experience of it. Put in B.P.s terms: How can we wrest these early works away from their art historical assimilation as art objects (they are, indeed, received in the widest sense as such, regardless of their status as performative ephemera) and experience them anew as means toward the formulation of novel perceptual and behavioral patterns? Explicitly evoking the historical avantgarde and simultaneously dismissing both neuroscience and psychedelics, this nearly fty year old texts call for working through such newly discovered patterns via and beyond the bounds of art reads today with undiminished urgency. The combination of psychological methodology with the specic instances of his works exceeds a looming positivism (Pavlov, the Red Chinese) and points toward the potential of a perpetual recomposition of our selves via sensuous experience. If normative behavior is predicated on usefulness, on that which is benecial to a given self (as B.P. describes), the uselessness of Pattersons exercises suggests an authentically postCagean indeterminacy. Who, indeed, are you after performing a given exercise

44

Bill Dietz, Benjamin Pattersons Lost PETs (2014)

45

from methods & processes until process becomes automatic? Who would you be if processing networks in [your, the reader-participants] brain would indeed become receptive to such new patterns? It is no wonder that after a gap of twenty odd years, B.P.s return to art is accompanied by turning his tools diNotes on PETs * 1 rectly on the behavioral patterns of the Benjamin Patterson art world in works such as How the Average Person Thinks About Art (1983), Critical Encounters (1988), and Artists Greeting (1988). Derivative is usually a nasty word. Thus In late Spring 2013, Mitch McEwen perhaps I feel the necessity to defend and I paid B.P. a visit in Wiesbaden. On and explain the resemblances between the train ride over from Stuttgart, we methods I have used in recent pieces and agreed that the Notes on PETs would certain methods used by psychologists in be an excellent entry for conversation. clinical and experimental work. But upon mentioning it, B.P. responded These resemblances are not accidensomewhat dismissively, Oh, that old tal. The methods have been consciously thing In the text, however, he writes assimilated. They are, however, not the with an uncanny prescience: The art- result of an attempt to produce any sense ists have come to accept the educational of parody, satire, etc. Criticism of socilimits of their work (their methods), to etys involvement with modern psychology is not the intent of these pieces. The deaccept that what they offer society is often overlooked and rarely accepted or cisions favoring this assimilation have been largely pragmatic; that is, based on adopted. It is hoped that only ignorance of the possibilities of pedagogical innov a recognition that these methods have a ation has made this retreat possible. capacity to produce desired results with I cant read this statement today with- a greater degree of predictability. In an out thinking of Pasolini writing, Death earlier attempt to dene my position, is not in being unable to communicate, I stated, My intentions have not been but in not being understood. We dont to produce Art , but have instead condeserve B.P., clearly. And yet we have trived to excite that faculty or faculties the great privilege of his continued tol- responsible for integrating experience. erance of us. In Wiesbaden, after our I have been obsessed with training and overly-thought-out conversation starter exercise. Provocative, but not enlightbombed, we went on to have a wonder- ening. Here a more substantial explanful day together. When we headed off to ation will be attempted. I require that the central function of catch the last train home, we were laden with gifts even a few objects which B. P. the artist be a duality of discoverer and had signed, grinning. Art objects or me- educator: discoverer of the varying possimentoes of an intimate educational en- bilities for selecting from environmental stimuli specic percepts and organizing counter? these into signicant perceptions, and Long live B.P. and his PETs. Berlin, January 2014 concurrently, as an educator, training a public in the ability to perceive in newly discovered patterns.2 The activity of discovery can only take place in the mind of the artist and remains imperceptible to all others. What may be perceived by an outsider is the activity of education, usually attempted through the exhibition

of art objects. Actually, every artist rewards offered mere producers of aesserves in this dual capacity, even though thetic objects are apparently sufcient his function as an educator is usually ob- to distract or buy off many good teachscured by his function as a producer of ers. The artists have come to accept the aesthetic objects. To illustrate, we nd educational limits of their work (their methods), to accept that what they offer in the history of painting styles such discoveries as perspective, the distribu- society is often overlooked and rarely action of light, pointillism, cubism, collage, cepted or adopted. It is hoped that only pop art and op art. Each style is actu- ignorance of the possibilities of pedaally a by-product of a new discovery of gogical innovation has made this retreat how percepts stimulated by the environ- possible. ment may be selected and organized But then, some persist. The Dadato obtain visual signicance (i.e., enter ists were among the rst to reject the into a critical relationship with the indi- traditional methods. And now, with the viduals previous comprehension of the development of happenings (more acenvironment). But this is obvious. What curately, environments) and other lesser is not obvious is that these art objects known activities3, it seems that some art(the paintings) are in the rst order not ists are again re-examining and searchaesthetic objects, but educational tools. ing for new methods. However, even in They stand between the subject matter the majority of this work the method is (the environment) and the student (the still exhibition. The observer is still on viewer) in much the same manner as do his own to devise methods by which he the audio-visual materials associated may assimilate these new patterns into with progressive schools. While there his own mentality. The results in terms has been a constant evolution of the role of conversion or assimilation can only be and subject of art throughout its history, uneven and certainly not predictable. there has not been a parallel developThe development of patterns of hument of its methods. In an earlier con- man behavior (of which perception is a text, a supporting role in religious ritual, part) is generally held to be at least parthe design and methods of the art object tially the result of environmental preswere probably adequate. However, the sures. The individual, through his experimajor portion of art today is no longer ences in the environment, observes the intended for this context, and in many results of specic acts of behavior to cases the artists intended content is of be either benecial or not benecial to such dimensions that its full expression his well-being. These specic acts and demands a complete ritual. Nevertheless, their results are noted by the individual a majority of artists today still attempt to (feedback) and classied into groups or communicate and educate using methods sets, from which networks or patterns of originally designed for a supplementary behavior develop. The adoption of any role. The result is an exhibition of mater- specic pattern of behavior (in this case, ials, the effectiveness of which is depend- perception) by the individual depends ent upon the skill of each individual in upon the degree of usefulness which he judges the pattern of behavior will obanalysis and / or chance assimilation. The development of the professional critic, tain in his attempts to maintain or imwith his published analysis and interpret- prove his well-being within the environations, has returned a certain pedagogic- ment. All this suggests that, to affect a al aspect to the art object, even though behavioral change, the individual must be his efforts have often only obscured the active, not passive, in the environment. original teachings. With societys growing The psychologists say about perception, need for discoveries and education in in- Far from being a passive representation tegrated perception, the responsibilities of what is there, perception shows itof the artist are greater than ever before, self to be a highly selective effort after meaning (Barlett, 1832) whereby the but his methods are inadequate, and the

46

47

individual brings upon the information York, 1964) structured a social environavailable at his sense organs a cognitive ment using individual anxiety and group structure determined by his needs, atti- allegiance. Seminar (I) (New York, 1964) tudes, previous experience and biological employed team participation, impromake-up (N. F. Dixon) and We may visation and the anticipation of an audithink of perception as the end result, the ence (three important factors in successful persuasion according to J. D. Frank, output, of physiological systems adapted to handle information originating from 1961). The following work, Seminar II, is the environment. When we see a table, an environment of challenge, the magnihighly complex mechanisms are involved. tude of the challenge being determined It might be said that as we come to under- by the participant himself. stand these mechanisms we explain perNew York, May 1965 ception (R. I. Gregory). The problem of achieving in an individual specic patterns of perception is then a problem of de- * Editors note: We wish to thank Ben Patterson veloping information processing networks and Hannah Higgins for authorizing our reproducin his brain receptive to these patterns. tion of this text, which originally appeared in The But how? Neither mechanical nor Four Suits: Alison Knowles, Tomas Schmit, Benjamin chemical methods at the moment are Patterson, Philip Corner (New York: Something Else attractive. Neuro-surgery cannot be Press, 1965), 4956. considered. Hallucinatory drugs are limit- 1 Perception Education Tools. ed in their usage and range, as are the 2 Environments here include not only the maDream machines developed by Gray terial surroundings, but the psycho-sociological Walter and Bryon Gysin. However, the habits and intellectual traditions (if these are methods of psychological conditioning separate entities) of the society as well. Percepand persuasion (judged from results ob- tion therefore includes not only organization of tained in other areas) seem to offer information concerning physical phenomena, but more promising solutions. Briey, these also social, psychological and intellectual condimethods involve structuring an environ- tions. ment in such a way that the inhabitant 3 See Fluxus I, An Anthology (Young & Mac Low), of the environment nds it desirable to and Postface (Higgins) for more on these acmake certain adjustments in his patterns tivities. See Appendix for excerpts from these of behavior to maintain or improve his 4 well-being. Pavlov presents the classic works. example. Others are the brainwashing techniques of the Red Chinese, therapy groups (such as Synanon) and the recent Edison Responsive Environment (New APPENDIX York Times, May 9, 1965). from Methods & Processes Below follows a rsum of my experiments in this area.4 think of a number 6 Methods and Processes (Paris, 1962) was bark like dog the rst attempt to structure specic en- think of number 6 twice vironments for conditioning. These were, stand up for the most part, micro-environments, (do not think of number 6) composed of instructions relating back to sit down the reader-participant. Tour (New York, think of number 6 1963) experimented with partial isola- bark like dog tion of the individual from the environment. Examination (New York, 1963) per- think of color brown mitted free exploration within a sharply (azure) dened environment. Symphony (New think smell of roasting coffee beans

think feel of brown suede leather think color of cognac think smell of coconut shelled crabs think feel of cognac brown Indian silk (lavender) think of color of orange think smell of apricots think feel of gold sh (iris) think color of nicotine ngers think smell of sweat stained shirts think feel of scaling orange iron rust (scarlet) think color of blue sulphate think smell of blue-black gs think taste of burning purple smoke (violet or pink)

Symphony

One at a time members of audience are questioned, Do you trust me? and are divided left and right, yes and no. The room is darkened. Freshly ground coffee throughout the room. is scattered

Seminar (I)

The general outline of the seminar is explained to the participants. Models of the particular genre of activity (compositions) which will be examined are demonstrated and rehearsed by the participants. Participants are divided into discussionwork groups. The characteristics, problems, etc. of these models are discussed and new activities are composed within the genre. Each work group presents its new compositions to the seminar. General discussion, if any.

Tour

Persons are invited and meet at designated time and place to commence tour. After methods and general conditions of tour are explained, participants are tted with blindfolds or similar devices and led through any area or areas of guides choice(s). Duration exceeds 45 minutes.

Examination

Dene and elaborate upon the purposes of this examination. (1 hour)

48

Вам также может понравиться

- Robert Irwin Whitney CatalogДокумент60 страницRobert Irwin Whitney Catalogof the100% (1)

- Dieter Mersch Epistemologies of Aesthetics 1Документ177 страницDieter Mersch Epistemologies of Aesthetics 1Victor Fernández GilОценок пока нет

- ATKISON, Dennis. Contemporary Art and Art Education ARTIGOДокумент14 страницATKISON, Dennis. Contemporary Art and Art Education ARTIGOCristian ReichertОценок пока нет

- MFA ThesisДокумент29 страницMFA ThesisStephenHawksОценок пока нет

- Feeling AND Form: A Theory of ArtДокумент433 страницыFeeling AND Form: A Theory of ArtHendrick Goltzius0% (1)

- Thinking MusicallyДокумент14 страницThinking Musicallypaperocamillo100% (2)

- Unit - 1 PDFДокумент18 страницUnit - 1 PDFsrikavi bharathiОценок пока нет

- Crime SketchДокумент21 страницаCrime Sketchapi-315587816Оценок пока нет

- Comte de LautréamontДокумент10 страницComte de LautréamontAbraxazОценок пока нет

- A Number Words On Plays (2006) PDFДокумент56 страницA Number Words On Plays (2006) PDFronaldo100% (1)

- ConceptДокумент39 страницConceptPaul HenricksonОценок пока нет

- Creativity, Learning and Play in A Fluxcentric World, or How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love Art, Owen F. SmithДокумент13 страницCreativity, Learning and Play in A Fluxcentric World, or How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love Art, Owen F. Smithdr.fluxОценок пока нет

- Week 1 Gec 106Документ16 страницWeek 1 Gec 106Junjie FuentesОценок пока нет

- BienalДокумент13 страницBienalRenataScovinoОценок пока нет

- Jerrold Levinson - Aesthetic Contextual IsmДокумент12 страницJerrold Levinson - Aesthetic Contextual IsmDiego PellecchiaОценок пока нет

- Artificial Hells, A Conversation With Claire BishopДокумент5 страницArtificial Hells, A Conversation With Claire BishopTanja Baudoin100% (1)

- Lucy Lippard Desmaterialización Del ObjetoДокумент7 страницLucy Lippard Desmaterialización Del ObjetoCelia SierraОценок пока нет

- Artistic Research: A Performative Paradigm?Документ14 страницArtistic Research: A Performative Paradigm?Denise BandeiraОценок пока нет

- Artistic CreativityДокумент14 страницArtistic CreativityKaren L Olaya MendozaОценок пока нет

- Bateson, Gregory, Review Clifford Geertz (1967) PDFДокумент2 страницыBateson, Gregory, Review Clifford Geertz (1967) PDFRogelio AlcántaraОценок пока нет

- Poiesis and Art MakingДокумент13 страницPoiesis and Art MakingJudhajit SarkarОценок пока нет

- Journal of Visual Culture 2010 Balfour 29 43Документ16 страницJournal of Visual Culture 2010 Balfour 29 43Anonymous YoF1nHvRОценок пока нет

- The Writing Artist: Jan SvenungssonДокумент6 страницThe Writing Artist: Jan SvenungssonBat AlОценок пока нет

- The Necessity An Aesthetics: of As ofДокумент13 страницThe Necessity An Aesthetics: of As ofLata DeshmukhОценок пока нет

- Dazevedo - Definition of ArtДокумент13 страницDazevedo - Definition of ArtThomaz SimoesОценок пока нет

- Mersch Dieter Epistemologies of AestheticsДокумент176 страницMersch Dieter Epistemologies of AestheticsfistfullofmetalОценок пока нет

- Bill Henson Untitled 1982-84 1987 FinalДокумент20 страницBill Henson Untitled 1982-84 1987 FinalმირიამმაიმარისიОценок пока нет

- Review of Strange ToolsДокумент5 страницReview of Strange ToolsIsabela CarlettiОценок пока нет

- Art and BeautyДокумент3 страницыArt and BeautyZeynee AghaОценок пока нет

- Becker Field and WorldДокумент13 страницBecker Field and WorldAmparaguazoОценок пока нет

- Aesthetics-What? Why? and Wherefore?: Kendall WaltonДокумент15 страницAesthetics-What? Why? and Wherefore?: Kendall WaltonJLОценок пока нет

- Between The Visible and The Unspeakable: An Interview With Lilia Moritz Schwarcz About Histories and CuratorshipДокумент13 страницBetween The Visible and The Unspeakable: An Interview With Lilia Moritz Schwarcz About Histories and CuratorshipjksjsОценок пока нет

- Can Improvisation Be TaughtДокумент9 страницCan Improvisation Be TaughtJulián Castro-CifuentesОценок пока нет

- New ModernsДокумент15 страницNew ModernsSimon O'SullivanОценок пока нет

- Popular+inquiry Vol1 NaukkarinenДокумент14 страницPopular+inquiry Vol1 NaukkarinenAlice XuОценок пока нет

- Wollheim, Art and Its ObjectsДокумент102 страницыWollheim, Art and Its ObjectsArs NovaОценок пока нет

- MullerДокумент13 страницMullerAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiОценок пока нет

- Tok Presentation Arts StereotypesДокумент5 страницTok Presentation Arts StereotypesLa ReinaОценок пока нет

- Found Objects in The Design Process MoreДокумент6 страницFound Objects in The Design Process MoreCamila Goncalves dos SantosОценок пока нет

- Aesthetic ReportДокумент11 страницAesthetic ReportCHARLENE JOY TABARESОценок пока нет

- On The Creation of Art, BeardsleyДокумент15 страницOn The Creation of Art, Beardsleyherac12Оценок пока нет

- Learning To See in MelanesiaДокумент19 страницLearning To See in MelanesiaSonia LourençoОценок пока нет

- Lesson 4 Subject and Content: "What": "Why" HowДокумент13 страницLesson 4 Subject and Content: "What": "Why" HowLexie KepnerОценок пока нет

- An Idea Out of MaltaДокумент18 страницAn Idea Out of MaltaPaul HenricksonОценок пока нет

- Art Worlds, 25th Anniversary Edition: 25th Anniversary edition, Updated and ExpandedОт EverandArt Worlds, 25th Anniversary Edition: 25th Anniversary edition, Updated and ExpandedРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (19)

- Andrew Piper, There Will Be NumbersДокумент4 страницыAndrew Piper, There Will Be Numberscbcarey1Оценок пока нет

- Essay Concept ArtДокумент4 страницыEssay Concept ArtRara JLovemoyОценок пока нет

- Educating Openness: Umberto Eco 'S Poetics of Openness As A Pedagogical ValueДокумент27 страницEducating Openness: Umberto Eco 'S Poetics of Openness As A Pedagogical ValueJksaksadflksad KjcnsdОценок пока нет

- Mental Catharsis and Psychodrama (Moreno)Документ37 страницMental Catharsis and Psychodrama (Moreno)Iva Žurić100% (2)

- Art Keeps Us in and With The World: Gert Biesta in Conversation With Lisbet SkregelidДокумент14 страницArt Keeps Us in and With The World: Gert Biesta in Conversation With Lisbet SkregelidkathrynОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Art and Art in Education - The New, Emancipation and TruthДокумент14 страницContemporary Art and Art in Education - The New, Emancipation and TruthMaria João LopesОценок пока нет

- Pisaro11 ThesesДокумент11 страницPisaro11 ThesesmeliaminorОценок пока нет

- The Return of Visual Culture Why NotДокумент3 страницыThe Return of Visual Culture Why NotElver ChaparroОценок пока нет

- Modyul Sa Pagpapahalaga Sa SiningДокумент18 страницModyul Sa Pagpapahalaga Sa SiningJohn Rick MesaОценок пока нет

- Across the Art/Life Divide: Performance, Subjectivity, and Social Practice in Contemporary ArtОт EverandAcross the Art/Life Divide: Performance, Subjectivity, and Social Practice in Contemporary ArtОценок пока нет

- Vernon Lee-Beauty and UglinessДокумент422 страницыVernon Lee-Beauty and UglinessMerve Deniz100% (1)

- Les Immatériaux - A Conversation With Jean-François Lyotard (From Flash Art)Документ10 страницLes Immatériaux - A Conversation With Jean-François Lyotard (From Flash Art)Mattia CapellettiОценок пока нет

- Seda Sicimoğlu Yenikler ARHA 508 Response Paper - Week 6 31.10.2016Документ4 страницыSeda Sicimoğlu Yenikler ARHA 508 Response Paper - Week 6 31.10.2016kuntokinteОценок пока нет

- Arts6 Q1 WK1Документ28 страницArts6 Q1 WK1JOVELYN BAQUIRANОценок пока нет

- Choral Festival Brochure '19 LRДокумент116 страницChoral Festival Brochure '19 LRThe Journal of MusicОценок пока нет

- W.B Yeats Exams QuestionsДокумент4 страницыW.B Yeats Exams QuestionsNaveed Iqbal Khan100% (1)

- Prudential Building, New York (1895-1896)Документ13 страницPrudential Building, New York (1895-1896)KarunyaОценок пока нет

- Wmi Grade 3 3015Документ4 страницыWmi Grade 3 3015Eiky Kwok0% (1)

- LAN Completes Saclay Student Residences For Grand Paris ProjectДокумент17 страницLAN Completes Saclay Student Residences For Grand Paris ProjectSpam TestОценок пока нет

- World Lit Exam KoДокумент3 страницыWorld Lit Exam KoMari LouОценок пока нет

- Contextualize The Text From A Historical and Cultural Point of View - FFFF BunДокумент7 страницContextualize The Text From A Historical and Cultural Point of View - FFFF BunAngela Angelik100% (2)

- Music (Hind)Документ38 страницMusic (Hind)ihateu1Оценок пока нет

- 1423652370naac Cmdpgcollege PDFДокумент237 страниц1423652370naac Cmdpgcollege PDFshreya sharmaОценок пока нет

- Origamic ArchitectureДокумент3 страницыOrigamic ArchitectureRogelio Hernández AlmanzaОценок пока нет

- Chettinad Houses: Ajith Kumar M M S3 B.Arch Roll:4Документ23 страницыChettinad Houses: Ajith Kumar M M S3 B.Arch Roll:4Reshma MuktharОценок пока нет

- Mounting PrintsДокумент2 страницыMounting Prints65paulosalesОценок пока нет

- Constructivism QuotesДокумент8 страницConstructivism QuotesSam HarrisОценок пока нет

- Elle Australia - January 2019Документ172 страницыElle Australia - January 2019Francisco Bustos-GonzálezОценок пока нет

- Moon Skull: Template and InstructionДокумент14 страницMoon Skull: Template and InstructionJackelyn Sharon100% (1)

- Festivals PDFДокумент57 страницFestivals PDFSuraj BirokaОценок пока нет

- Bài Tập Tiếng Anh Lớp 9 Theo Từng Bài Học Có Đáp Án Chi TiếtДокумент266 страницBài Tập Tiếng Anh Lớp 9 Theo Từng Bài Học Có Đáp Án Chi TiếthoangmaiОценок пока нет

- Modern Finnish Wooden TownДокумент6 страницModern Finnish Wooden TownChechu MenendezОценок пока нет

- Final Video Graphy AssignmentДокумент18 страницFinal Video Graphy AssignmenthalaОценок пока нет

- (NT) ZumbiДокумент9 страниц(NT) Zumbiwrcw4dvz6cОценок пока нет

- Dancer SwapnaДокумент3 страницыDancer SwapnaSukanta PradhanОценок пока нет

- Revised Draft Equivalace List28!10!2014Документ16 страницRevised Draft Equivalace List28!10!2014Mrutyunjaya BeheraОценок пока нет

- GDA Master Plan - 2031 Ghaziabad (Draft)Документ1 страницаGDA Master Plan - 2031 Ghaziabad (Draft)Adarsh TyagiОценок пока нет

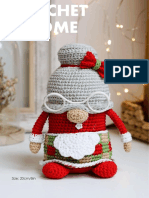

- Mrs - Santaclaus CrochetgnomeДокумент11 страницMrs - Santaclaus CrochetgnomeArnaud Gdn100% (5)

- Film Budget Template StudioBinderДокумент46 страницFilm Budget Template StudioBinderDavid AzoulayОценок пока нет