Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

) On Armed Drones

Загружено:

Vlad SurdeaИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

) On Armed Drones

Загружено:

Vlad SurdeaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

1)

On armed drones

The general public has also recognized these benefits: a Gallup poll conducted last March found that roughly two-thirds of Americans approved of drone strikes on suspected terrorists abroad, unless the target was a U.S. citizen. Domestic opposition to the development or use of drones creates additional problems in other states, even some with the technological capacity to build and field them.In Germany, for example, politicians who advocate drones have faced harsh criticism from a public worried about compromising Germanys long-standing defense-only national security policies. Source: Foreign Affairs

2) On a way more nuanced theory on the terrorist mentality than mad people that only follow an intrinsic goal Economists and political scientists using a rational-choice framework are fond of pointing out that individuals should be reluctant to commit real resources of time,money, and risktaking to advance the cause of a large group. The benefits of advancing the group are available to all group members, whereas the costs are borne by the activists. Thus the rational choice for an individual who cares about a group cause is to do nothing, let other individuals pay the costs, and benefit from any advance for the group as a free-rider.16 The classic answer to the problem of mobilizing individuals for social action is some kind of coercion, that is, punishment for free-riding. Coercion may come from law or government regulation (if free-riders can be accurately identified), from individual morality (internal norms), or from informal face-to-face sanctions (small group norms). According to social comparison theory, opinion positions have social values attached to them. All individuals feel pressure toward agreement, that is, pressure to move their opinions toward the mean opinion of the group. But the pressure is not uniform. Individuals more extreme than average in the group-favored directionthe direction favored by most individuals before discussionare more admired.36 They are seen as more devoted to the group, more ablein sum, as better people. This extra status translates into more influence and less change during group discussion, whereas individuals less extreme than average in the group-favored direction have less influence and change more. No one wants to be below-average in support of the group-favored opinion, and the result is that the average opinion becomes more extreme in the group-favored direction. A vivid description of the power of social comparison in radicalizing the Weather Underground, a U.S. anti-war group of the 1970s, is provided by Collier & Horowitz.37 Within-group competition for the status of being most radicalmoved the group to terrorism. The hallmark of this kind of radicalization is the extent to which the personal becomes politicized: every act is judged by political standards, including who sleeps with whom. Very high levels of cohesion in a group mean very strong pressures for agreement of group members. Group dynamics theory distinguishes between two sources of attraction to a group: the value of material group goals and the value of the social reality created by the

group. Material goals include the obvious rewards of group membership, such as progress toward common goals, congeniality, status, and security. Less obvious is the social reality value of the group: there are many questions of value for which the only source of certainty is group consensus. What is good and what is evil? What is worth working for, worth dying for? What does it mean that I am going to die? Certainty about these crucial human questions can only come from agreement with others.Thus high cohesion brings high pressures for both behavioral compliance and for internalized value consensus. It is obvious to group members that they have to pull together in order to reach group goals, and the result in many cases is compliancego-along-to-get-along agreement that does not bring interior certainty. But the social reality value of the group depends on internalizing group standards of value, including moral standards. Source:A study made by Clark McCauley & Sophia Moskalenko.

3) On democratization and the Middle East Democratization, Sorensen argues, must be seen as having two distinguishable and separable dimensions: first, increasing competitiveness, that is, political liberalization or pluralization, and secondly, increasing political equality, that is,inclusiveness. Full democratization would entail both competitiveness and inclusion.However, it is quite possible to increase the scope of competition for some parts of the population without increasing inclusiveness (in which case political liberalization signifies a move from autocracy to oligarchy or to limited class democracy). First, it is important in shaping conceptions of political legitimacy, which are everywhere constructed of intersubjective (that is,cultural) understandings. It is plausible to argue that Islamic traditions accept authoritarian leadership as long as it is seen to serve the collective interest, that is,defends the community from outside threats and delivers welfare to which people feel entitled, and as long as it is seen to consult with the community (shura).

Moreover, the socialization transmitted within the patriarchal family is arguably congruent with patrimonial rule at the state level: just as the father expects, and receives, obedience in the family so the same may apply to the ruler in the state. The Middle East remains in transition to modernity; hence the obstacles to democratization typical of the transition persist today. The combination of increased social mobilization (notably literacy) and population growth with increased economic inequality amidst states suffering from unconsolidated political identity makes for a particularly democratic-unfriendly environment. Instead of democracy, two outcomes were typical: in the most tribal regions, oil rentierism locked in a shaikhly authoritarianism of the right. In the more advanced settled regions, large landed classes stimulated radical alliances of the salaried middle class and peasantry, issuing in revolutionary coups and a populist authoritarianism of the left. These forms of authoritarianism were arguably congruent with the social structure of their societies, while

stable democracy is not likely to be as congruent until and if these structures are transformed. First, PA( Populist Autocracies) regimes issued from revolutionary coups, originating in the heart of society and expressive of revolt by nativist plebeians against cosmopolitan oligarchs entrenched under Western tutelage.Second, all PA regimes were reactions against ongoing Western penetration of the region and the conflict with Israel. Playing the nationalist card enabled them to discredit the old pro-Western oligarchies while winning over the nationalist middle class and peasantry.Third, PA regimes were consolidated structurally. Military and bureaucratic expansion produced the largest organizations in society. Single-party systems penetrated factories, villages and schools and created or took over corporatist associations organizing the various sectors of society workers, peasants, women, youth.Fourth, PA regimes enjoyed reliable instruments of repression. They learned how to prevent coups, hitherto the main vehicle of regime change. Multiple wings of the mukhabarat (intelligence or security services) maintained pervasive surveillance and specialized security forces repressed active rebellion.Fifth, and crucial to understanding the resistance of PA regimes to democratic change, is that the PA revolutions from above weakened that social force with the strongest interest in the economic liberalization needed to advance political pluralization,namely the bourgeoisie, while incorporating those most threatened by it,namely workers, peasants and civil servants. PA regimes thus tended to deter formation of a democratic coalition because they greatly weakened the bourgeoisie This is where the Islamic factor has its main impact in deterring democratization.Islamic movements fill the welfare gap left by the states post-populist retreat from its welfare responsibilities and, as they champion the victims of economic liberalization,the banner of populism is transferred from regime to Islamic opposition. This dynamic tends to make the political incorporation of Islamic movements incompatible with post-PA economic liberalization. However, without inclusion of Islamist movements in the political system, there can be political liberalization but there can be no democratization. Algeria produced the harshest lesson, namely that economic reform combined with rapid and thorough democratization is disastrous:there it produced Islamist electoral victory, military intervention, civil war(in which the hard-liners on both sides marginalized the moderates) and the rapid reversal of democratization.

4)On the possibility of a North Korean Spring North Korea still ranks seventh out of seven (the lowest possible score) on Freedom Houses Freedom in the Worldindex, and it has therefore earned the odious title, the Worst of the Worst for its political rights and civil liberties record.14 It sits la st of 167 countries on the Economist Intelligence Units (EIU) democracy index.15 It is in the 0th percentile for the World Banks Voice and Accountability index, and is ranked 196 out of 196 countries in the Freedom of the Press index. What is astonishing about these rankings is not the absence of movement to a softer form of authoritarianism, necessitated by the need for economic reform,but that the regime has consistently maintained such controls, decade after decade, without letting up whatsoever. This persistence stems not from a lack of understanding that some liberalization is

necessary for economic reform, but from the Kim regimes conscious choice to prize political control over anything else. This puts the Kim regime in a class of authoritarianism of its own. Defectors from North Korea show anger toward their former prison guards or toward corrupt bureaucrats, but this surprisingly does not aggregate into an anger to expel the Kim leadership. A July 2008 survey of refugees in Seoul, for example,found that 75 percent had no negative sentiment toward Kim Jong-il.A National Geographic documentary, Inside North Korea, followed an eye doctor around the country who did cataract surgeries for ailing citizens.20 After thousands of surgeries,upon having their bandages removed, every single patient immediately and joyously thanked Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il for their renewed eyesight, not the doctor. There are several reasons for the lack of a politically active exile community.First, recent migrants out of North Korea are almost all females leaving the country purely for economic reasons. Some 75 percent of recent defectors are from the northern Hamgyong provinces, which is the worst area economically in North Korea. Women therefore leave the country purely as an economic coping mechanism to survive rather than to act out political ambitions against the regime. Furthermore, because they most often leave husbands and children behind who wait for much-needed support, such as food, money, and medicine,these female defectors are unlikely to become political activists and put their families at risk. The change was evident in the way in which people responded to the governments effort to crack down on marketization by instituting a currency redenomination in 2009. This redenomination wiped out the hard work of many families, who could exchange only a fraction of their household savings for the new currency. People reacted not with typical obedience out of fear, but with anger and despair. Some committed suicide. Others fought with police who tried to close down their local market.27 Still Others defiantly burned the currency in the public square.28 The greatest vulnerability for a regime like North Korea is when a population loses its fear of the government.Once the fear is gone, all that is left is the anger. That turning point may have been reached in 2009 While according to the previously mentioned metrics, all looks calm in the hermit kingdom, there are underlying factors that could potentially spell the end of the Kim regime. The combination of tectonic, bottom-up societal shifts counteracted by rigid, top-down suppression efforts is creating a tension in the North that could give way someday soon perhaps when the stroke-stricken DPRK leader falls ill again creating a political earthquake in the country. And The forces unleashed by spreading modern technology seem to only exacerbate these ongoing trends.

Вам также может понравиться

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Conservative Political Movements: The Religious Right, the Tea Party, and the Alt-RightОт EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Conservative Political Movements: The Religious Right, the Tea Party, and the Alt-RightОценок пока нет

- Everyday Politics: Reconnecting Citizens and Public LifeОт EverandEveryday Politics: Reconnecting Citizens and Public LifeРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Consociation and Voting in Northern Ireland: Party Competition and Electoral BehaviorОт EverandConsociation and Voting in Northern Ireland: Party Competition and Electoral BehaviorОценок пока нет

- Political Advocacy and Its Interested Citizens: Neoliberalism, Postpluralism, and LGBT OrganizationsОт EverandPolitical Advocacy and Its Interested Citizens: Neoliberalism, Postpluralism, and LGBT OrganizationsОценок пока нет

- Draining the Swamp: Can the US Survive the Last 100 Years of Sociocommunist Societal Rot?От EverandDraining the Swamp: Can the US Survive the Last 100 Years of Sociocommunist Societal Rot?Оценок пока нет

- SUICIDE TERRORISM: IT'S ONLY A MATTER OF WHEN AND HOW WELL PREPARED ARE AMERICA'S LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERSОт EverandSUICIDE TERRORISM: IT'S ONLY A MATTER OF WHEN AND HOW WELL PREPARED ARE AMERICA'S LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERSОценок пока нет

- Democracy from the Grass Roots: A Guide to Creative Political ActionОт EverandDemocracy from the Grass Roots: A Guide to Creative Political ActionОценок пока нет

- Project 6 Signature AssignmentДокумент9 страницProject 6 Signature Assignmentapi-722214314Оценок пока нет

- Muslims Talking Politics: Framing Islam, Democracy, and Law in Northern NigeriaОт EverandMuslims Talking Politics: Framing Islam, Democracy, and Law in Northern NigeriaОценок пока нет

- A Shared Future: Faith-Based Organizing for Racial Equity and Ethical DemocracyОт EverandA Shared Future: Faith-Based Organizing for Racial Equity and Ethical DemocracyОценок пока нет

- They’re Not Listening: How The Elites Created the National Populist RevolutionОт EverandThey’re Not Listening: How The Elites Created the National Populist RevolutionОценок пока нет

- #01 - Political SocialisationДокумент6 страниц#01 - Political SocialisationCheolyn SealyОценок пока нет

- Non Party Political Process R. Kothari PDFДокумент17 страницNon Party Political Process R. Kothari PDFBono VaxОценок пока нет

- Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970От EverandPolitical Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970Оценок пока нет

- Nonviolent Resistance and Prevention of Mass Killings During Popular UprisingsОт EverandNonviolent Resistance and Prevention of Mass Killings During Popular UprisingsОценок пока нет

- Global Politics: Exploring Diverse Systems and Ideologies: Understanding Political Systems, Ideologies, and Global Actors: Global Perspectives: Exploring World Politics, #1От EverandGlobal Politics: Exploring Diverse Systems and Ideologies: Understanding Political Systems, Ideologies, and Global Actors: Global Perspectives: Exploring World Politics, #1Оценок пока нет

- The Debasement of Human Rights: How Politics Sabotage the Ideal of FreedomОт EverandThe Debasement of Human Rights: How Politics Sabotage the Ideal of FreedomРейтинг: 2 из 5 звезд2/5 (1)

- Demagogues, Populists And Their Helpers: Politics of Division, Deceit and ConflictОт EverandDemagogues, Populists And Their Helpers: Politics of Division, Deceit and ConflictОценок пока нет

- Chronicling Civil Resistance: The Journalists' Guide to Unraveling and Reporting Nonviolent Struggles for Rights, Freedom and JusticeОт EverandChronicling Civil Resistance: The Journalists' Guide to Unraveling and Reporting Nonviolent Struggles for Rights, Freedom and JusticeОценок пока нет

- The Shadow Party: How George Soros, Hillary Clinton, and Sixties Radicals Seized Control of the Democratic PartyОт EverandThe Shadow Party: How George Soros, Hillary Clinton, and Sixties Radicals Seized Control of the Democratic PartyОценок пока нет

- State of Power 2016: Democracy, Sovereignty and ResistanceОт EverandState of Power 2016: Democracy, Sovereignty and ResistanceОценок пока нет

- Painful Birth: How Chile Became a Free and Prosperous SocietyОт EverandPainful Birth: How Chile Became a Free and Prosperous SocietyОценок пока нет

- The Origins of Liberty: Political and Economic Liberalization in the Modern WorldОт EverandThe Origins of Liberty: Political and Economic Liberalization in the Modern WorldОценок пока нет

- Political Science Second Edition: An Introduction to Global PoliticsОт EverandPolitical Science Second Edition: An Introduction to Global PoliticsРейтинг: 1 из 5 звезд1/5 (1)

- The Capital Come Under Bourgeois Rule And Present Scenario of Political BusinessОт EverandThe Capital Come Under Bourgeois Rule And Present Scenario of Political BusinessОценок пока нет

- Democracy in Peril: Restructuring Systems or Second RepublicОт EverandDemocracy in Peril: Restructuring Systems or Second RepublicОценок пока нет

- Who Becomes A TerroristДокумент44 страницыWho Becomes A TerroristPhương Lương MaiОценок пока нет

- State-Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st CenturyОт EverandState-Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st CenturyРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (21)

- Political Parties Influence and Pressure On Media OrganizationsДокумент52 страницыPolitical Parties Influence and Pressure On Media OrganizationsAdrianaОценок пока нет

- Personal Rule in Black Africa: Prince, Autocrat, Prophet, TyrantОт EverandPersonal Rule in Black Africa: Prince, Autocrat, Prophet, TyrantОценок пока нет

- How Solid Is Mass Support For Democracy-And How Can We Measure It?Документ8 страницHow Solid Is Mass Support For Democracy-And How Can We Measure It?GabrielRamosОценок пока нет

- International Relations - For People Who Hate PoliticsОт EverandInternational Relations - For People Who Hate PoliticsРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- Central African Republic Governance and Political ConflictОт EverandCentral African Republic Governance and Political ConflictРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Two Tyrants. The Myth of a Two-Party Government and the Liberation of the American VoterОт EverandTwo Tyrants. The Myth of a Two-Party Government and the Liberation of the American VoterОценок пока нет

- Politics & the Struggle for Democracy in Ghana: An Introduction to Political ScienceОт EverandPolitics & the Struggle for Democracy in Ghana: An Introduction to Political ScienceОценок пока нет

- Notes Adjudicators WsДокумент16 страницNotes Adjudicators WsVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- WSDC Debate Rules U 2017-2Документ51 страницаWSDC Debate Rules U 2017-2Alex ArpandiОценок пока нет

- Romanian Public Management Reform - Volume 1Документ320 страницRomanian Public Management Reform - Volume 1rousseau07Оценок пока нет

- William A. Edmundson-Death PenaltyДокумент11 страницWilliam A. Edmundson-Death PenaltyVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- Raz Legal ValidityДокумент16 страницRaz Legal ValidityVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- McCombs and Shaw POQ 1972Документ13 страницMcCombs and Shaw POQ 1972Vlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- Raz On AuthorityДокумент24 страницыRaz On AuthorityVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- Fuller-Morality of LawДокумент11 страницFuller-Morality of LawVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- Rawls Dworkin SДокумент50 страницRawls Dworkin SVlad Surdea0% (1)

- Nozick CritiqueДокумент21 страницаNozick CritiqueVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- The Warped BirdДокумент1 страницаThe Warped BirdVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- Hypothetical Consent HannahДокумент16 страницHypothetical Consent HannahVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- The Crisis of Legitimation of Political Estlablishments Is AvoidedДокумент4 страницыThe Crisis of Legitimation of Political Estlablishments Is AvoidedVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- Tax ExemptionsДокумент3 страницыTax ExemptionsVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- Political Obligation NockДокумент18 страницPolitical Obligation NockVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- Constitutionalism and Democracy - Political Theory and The American-Richard BellamyДокумент25 страницConstitutionalism and Democracy - Political Theory and The American-Richard BellamyVlad Surdea100% (1)

- American Imperialism-Andrew BakerДокумент12 страницAmerican Imperialism-Andrew BakerVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- Gheoghe Gheorghiu Dej - The Fight For PowerДокумент33 страницыGheoghe Gheorghiu Dej - The Fight For PowerVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- WSDC 2014 - Draw Head To HeadДокумент18 страницWSDC 2014 - Draw Head To HeadPaul LauОценок пока нет

- North KoreaДокумент19 страницNorth KoreaVlad SurdeaОценок пока нет

- Mass Media and Society QuestionsДокумент7 страницMass Media and Society QuestionsOlivia WoitulewiczОценок пока нет

- Panniru ThirumuraiДокумент22 страницыPanniru ThirumuraiRokeshwar Hari Dass100% (4)

- Chapter I234Документ28 страницChapter I234petor fiegelОценок пока нет

- Anthropology, Sociology&political ScienceДокумент5 страницAnthropology, Sociology&political ScienceAshley AgustinОценок пока нет

- Train The Trainer From Training JournalДокумент49 страницTrain The Trainer From Training JournalDr. Wael El-Said100% (7)

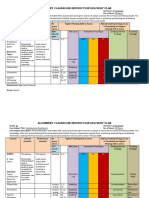

- Alignment Classroom Instruction Delivery PlanДокумент3 страницыAlignment Classroom Instruction Delivery PlanWilly Batalao PuyaoОценок пока нет

- Was Heidegger A Mystic?: Jeff GuilfordДокумент9 страницWas Heidegger A Mystic?: Jeff GuilfordDursun NaimОценок пока нет

- 4 PDFДокумент4 страницы4 PDFKashyap Chintu100% (1)

- Renaissance Art 1Документ4 страницыRenaissance Art 1Meshack MateОценок пока нет

- Emily Bronte As Areligious PoetДокумент322 страницыEmily Bronte As Areligious PoetUmar AlamОценок пока нет

- J.C.P. Auer Bilingual ConversationДокумент123 страницыJ.C.P. Auer Bilingual ConversationMaxwell MirandaОценок пока нет

- Bitch Slapping The Unslappable BitchДокумент5 страницBitch Slapping The Unslappable BitchP. H. Madore100% (1)

- 2nd Year English Essays Notes PDFДокумент21 страница2nd Year English Essays Notes PDFRana Bilal100% (1)

- Urban Tribes: - What Are They Wearing?Документ3 страницыUrban Tribes: - What Are They Wearing?Sareth Dayana Galvis GomezОценок пока нет

- Ethics in Organization PalehДокумент11 страницEthics in Organization PalehFaith Paleh RobertsОценок пока нет

- ECIL 2016 Open HouseДокумент25 страницECIL 2016 Open HouseSafdar QuddusОценок пока нет

- Applied English Phonology 3rd EditionДокумент1 страницаApplied English Phonology 3rd Editionapi-2413357310% (7)

- Stoll's Spiritual Assessment Assessment Guide: Mrs. X 45 Y/o Balatas, Naga CityДокумент2 страницыStoll's Spiritual Assessment Assessment Guide: Mrs. X 45 Y/o Balatas, Naga CityCarlos NiñoОценок пока нет

- Syllabus For CollegeДокумент6 страницSyllabus For CollegeKhyshen WuОценок пока нет

- Music 5 - Unit 1Документ4 страницыMusic 5 - Unit 1api-279660056Оценок пока нет

- 4 5850518413826327694Документ378 страниц4 5850518413826327694MOJIB0% (1)

- Setha M Low - PlazaДокумент14 страницSetha M Low - PlazaRENÉ CAVERO HERRERAОценок пока нет

- Learning Episode 2Документ9 страницLearning Episode 2Erna Vie ChavezОценок пока нет

- Andrea L. Smith, Colonial Memory and Postcolonial Europe: Maltese Settlers in Algeria and France. SeriesДокумент4 страницыAndrea L. Smith, Colonial Memory and Postcolonial Europe: Maltese Settlers in Algeria and France. Seriesianbc2Оценок пока нет

- Podcast Plan Template-1Документ4 страницыPodcast Plan Template-1api-490251684Оценок пока нет

- Dolores Huerta Primary and Secondary SourcesДокумент6 страницDolores Huerta Primary and Secondary Sourcesapi-393875200Оценок пока нет

- Invitation Letter Sports SummitДокумент7 страницInvitation Letter Sports SummitSantos Jewel50% (2)

- Uts Reviewer PDFДокумент3 страницыUts Reviewer PDFRyan Joseph100% (1)

- Agenda 2000Документ184 страницыAgenda 2000Anonymous 4kjo9CJ100% (1)

- Bernard Rosenthal - Records of The Salem Witch-HuntДокумент1 008 страницBernard Rosenthal - Records of The Salem Witch-HuntMilica KovacevicОценок пока нет