Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Comparison Meyerhold Stan

Загружено:

Haneen HannouchАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Comparison Meyerhold Stan

Загружено:

Haneen HannouchАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

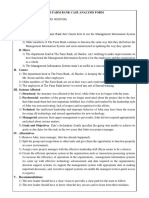

Zoja Buzalkovska The Creative Conflict between Stanislavski and Meyerhold and a Possible Fusion of Their Systems

1. INTRODUCTION It has been exactly 120 years since V.E. Meyerhold first left the Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) and started working on something which was soon to seriously challenge the system of K.S. Stanislavki in regard to the method of working with actors and an actors work on himself and his role. Interestingly enough, to this day Meyerhold has remained to be seen as avant-garde, mysticism, extreme by theatre theoreticians, while his approach is taken as something that is good to know, but would better be avoided when working on a play. This opposition to his system has particularly been evident on the Russian theatre scene, where Stanislavskian method of work still prevails in the theatre, while Meyerholdian is proclaimed an experiment, a sketch which has never been actually implemented in theatrical language and, therefore, should perhaps remain a museum treasure and set in the past of Russian avant-garde and the great utopia of the Russia of the 1920s. Unrelated to this subtle war, in the late 1980s the academic subject of Biomechanics was included into the curriculum of the GITIS (the major national theatre academy with a great international reputation in Moscow, todays RATI), Valery Fokin opened the Meyerhold Centre in Moscow, professors and directors such as Pyotr Fomenko and his successors, Ivan Popovski among others, extended Meyerholds thought and implemented it in their work in various ways, while an extensive literary opus and all the writings and letters associated to Meyerholds work have been published in the last thirty years with a great support of the Meyerhold Museum. Nevertheless, even 120 years after the first steps Vsevolod Emilevich took away from his teacher Stanislavski (as he would emphasise regardless of the fact that his formal professor was NemirovichDanchenko) and Stanislavskis understanding of acting and work with actors, even some 80 or 90 years after his writings, lectures, recorded instructions and notes during the process of working on the play The Inspector General and on his other plays, and 70 years after his death, the progressive and avant-garde thought of Meyerholds expression still struggles against the deeply rooted, entrenched practice of psychological realism, the theatre of experiencing, the feeling of truth and belief in the theatre, the play as in life. It struggles while working on plays in theatres, it struggles during the acting lessons at faculties of dramatic arts, it struggles with the nature of every actor who better understands and more easily adopts the Stanislavski method (in our opinion, a very absurd phenomenon), it struggles with audiences, who are presented with demand for a more committed engagement by the Meyerhold Theatre, and which they are not always willing to fulfil.

The practices of Stanislavski and Meyerhold started from the same point, the same source of love for the theatre and the same absolute dedication, as well as the engaged thinking and conceptualization of the work in the theatre, only to bifurcate, becoming two antipodes, two polar ends of the scope in the field of work with an actor, thus becoming perhaps the quintessential contrast between the presence and representation of an actor. All other approaches and techniques are, one could dare say, (mere) variations of these theatre system antipodes. Hence, it seems particularly important to try to develop this thesis based on their example. Despite all misunderstandings, open criticism, occasional rejoining and collaboration followed by new departures between Stanislavski and Meyerhold, it seems that the system of Vsevolod Emilievich would have never been able to develop, had it not been provoked by its own foundation, the system of Konstantin Sergeyevich. Furthermore, the Stanislavski system, as well as some of his later thoughts and observations on the theatre, testifies that he revisited his earlier rigid positions, which could be related to the theory and practice of Vsevolod Meyerhold. The point of serious divergence of these two systems is the work with actor, or, more accurately, the answer to the questions of where and how an actors creation starts, what it seeks out, and when it reaches the point of its completion in the process of working on a role. It seems that despite the fact that the road to the role in Stanislavskis system leads from the i nside outwards, quite on the contrary from Meyerholds system, which is directed from the outside in wards, both systems have a common goal. That is why something that, perhaps, seems impossible at first sight should be done - an attempt at a fusion of these two systems into one, new, which would create a true balance of presence and representation, using the strongest positions of both approaches, and jettisoning everything that many years of practice have proved insufficiently useful, and, moreover, harmful for the actor, crew, the directors work and the final result of a play. However, to reach that point, we first have to look at the question of what constitutes the opposition in conceptualising the theatre and the actor in these two antipodean systems?

2. ESSENTIAL POSITIONS OF THE STANISLAVSKI SYSTEM For Konstantin Sergeyevich Stanislavski, an act of the theatre should mirror the reality in the theatre. Speaking sharply against representation and imitation in the theatre, he bases his system on the art of experiencing, which he describes in the following way: Certain aspects of the human psyche obey the conscious mind and the will, which have the capacity to influence our involuntary processes. True, this demands long, complex creative

work, which only proceeds partially under the direct guidance and influence of the conscious mind. It is, for the most part, subconscious and involuntary. Only one artist has the power to do it, the most discriminating, the most ingenious, the most subtle, the most elusive, the most miraculous of artists nature. Not even the most refined technique can be compared to her. She holds the key! This attitude, this relationship to nature absolutely typifies the art of experiencing. (Stanislavski, 1982, 158)

This formulation already shows where the hidden danger of this system lies and displays its great intangibility. The partial control and incomplete influence of the conscious on the unconscious mind open, at the very beginning, the door to an unguaranteed, always changeable result, where every action of the actor is a hostage to the incomprehensibleness of his organic nature. On the one hand, his system undoubtedly brought a breath of fresh air into theatre and stripped it off a layer of artificiality, pretentiousness, theatricality and overplaying, but on the other, it is a system deeply buried into the actors psychology and challenged or negated for this very fact. That is why we take with caution his explanation of the conscious ways for affecting the unconscious. Stanislavski advocates: Subconscious creation through the actors conscious psychotechnique. (The subconscious through the conscious, the involuntary through the voluntary.) (Stanislavski, K. S. 1982, 26) One should create credibly, and that means thinking, wanting, striving, behaving truthfully, in a logical sequence, in a human way, within the character, and in complete parallel to it. As soon as the actor has done that, he will come close to the role and will begin to feel as o ne with it. For him, the art of the theatre is the creation of the life of a human spirit in a role and the communication of that life onstage in an artistic way, while, bringing our own individual feelings to it, endowing it with all the features of o ur own personality. (Stanislavski, K. S. 1982, 27) By conscious psychotechnique, Stanislavski means and suggests his magic If, Given Circumstances, Bits and Tasks and their definition with nouns and verbs, even the formulation of Tasks in order to set will into motion, with a suggested I am being.... To offer ones hand to yesterdays enemy is not simple by any means, and needs a lot of forethought and feeling. A Task of that kind can be qualified as psychological, and is quite complicated, (Stanislavski, K. S. 1982,149) he says, giving an example of psychological torture which can be imposed on the actor, because when he is given a Task that is psychological, he must set his subconscious mind in motion in just a few seconds between an extended hand of his enemy and his own decision to respond by reaching back, before he starts experiencing double mind, hatred, love, breaking, conscience, reconciliation, capacity to forgive, dignity, hesitancy, etc.

One of the key positions of Konstantin Sergeyevichs school is Emotional (Affective) Memory which helps the actor to fully accomplish his art of experiencing. Stanislavski says that such experiencing should be achieved at every performance of a play, setting in motion and recalling the same feelings every time it is repeated. But, the question is how to achieve this? Stanislavski himself, in a later stage of his work, wrote down in his notes: What is distasteful in the actors self-feeling? The first time you experience the feeling in a fresh, pure way, intrinsically. By repeating it dozens of times, the pure affective feeling starts merging with Emotional Memory of the onstage experience of the same feeling. Then, the feeling is polluted, poisoned and first loses some and later all of its directness and natural purity and resilience. Finally, what remains is a stage memory. Notes from Book No. 3319, l.10" (, 1986, II, 10) Everything done onstage without an inner justification, for Stanislavski is mechanical, since it does not come as a result of the real life of imagination. But, on the other hand, and contrary to many who think that Konstantin Stanislavski in his system absolutely neglects the aspect of work with the body, he emphasises that the delicacy of subconscious life cannot be expressed without exceptionally responsive and outstandingly well-trained vocal and corporal apparatus, as voice and body provide a means to convey almost imperceptible inner feelings. (Stanislavski, K. S. 1982, 29) However, we must emphasise that this by no means implies that the actor should take body for his starting point in work, but that body will gradually find its form, the accurate gesture will find its true expression, and voice its most powerful timbre once the inner life of the actor has reached the level of development which enables him to embody these external manifestations of experiencing. Thus, bodily expression becomes a symptom of whatever happens in the actors soul that he lends to the character he interprets. One of the greatest pitfalls of this system in the creative sense is the repetition of the actor in every subsequent role, regardless of the text he is uttering or character he is developing. Giving the material of his soul to the character, experiencing instead of representing, seeking always to commit himself and his emotional memory to his work, the actor starts being recognisable, but later becomes someone who reappears in every role and who plays Hamlet, Ivanov and Orestes in a very similar way.

3. ESSENTIAL POSITIONS OF MEYERHOLDS SYSTEM Quite on the contrary, the system of V.E. Meyerhold, from the very beginning to the tiniest of details involved in working with actors, is primarily focused on what the stage action looks like. That is, not WHAT and WHY, but much more HOW. Meyerhold advocates pure play, efficiency of movement, bright visual expression, with intonations and finding a particular tone of voice, the auditory potential of words. For him, the segment of rhythm and tempo of movement and speech are of utmost importance. He sees a play as a musical score. He insists that the actor has to develop an awareness of his own self onstage. The actors work it means to be able to perceive oneself onstage. One should get to know his body, in order that he knows exactly what it looks like when he takes a certain position, (Me, 1998, 46) he says in the first item of his acting lesson, the lesson consisting of forty-one items and can certainly be named the ACTING MANIFESTO today. The actor will gain an absolute control over his body if he combines rhythmic and general gymnastics in his work and if he even succeeds in being able to hear with every part of his body. Vsevolod Emilevich is not interested in anatomy, but the exploration of body as a material for stage play. In the ninth item of his manifesto, he emphasises the importance of playing with perspective, that is, the idea of changing the position of body onstage, playing with what is visible to audience and can be hidden from them at a certain point. To prepare an actor for this kind of theatre, Meyerhold suggests and does biomechanic exercises. They heavily rely on the laws of balance. The actor has to have such a command of his body to be able to quickly find the point of balance at any given moment. In one of his lectures, given on 12 th June 1922, he defined biomechanics: Biomechanics attempts to, in an experimental way, determine the laws of stage movement, and create exercises for actors training based on the norms of human behaviour.(Meyerhold, 1976, 169) Through these exercises the actor extends the possibilities of his work with body, which becomes cultivated, he develops an awareness of how to make his body visually most effective, as well as an ability to emphasise certain actions so that his body becomes visible in its full accuracy of nuanced actions. But, at the same time, Meyerhold warns: The technique of an actor, who has not lived through the spectrum of life, can lead him to the irrelevant circus acrobatics. (Me, 1998, 47) Speaking about the actors play, Meyerhold opens a question of reflective excitement and compares the road to reaching or starting such excitement in systems of play with inside and experiencing. In the case of the former, it is achieved through artificial excitement of the previously weakened feeling, and/or by systematic narcosis (alcohol, cigarettes, narcotics), and in the latter, through enforcing a feeling with hypnotic tension of previously weakened will. This leads us to the crucial proposition of his work with the actor. This is how Vsevolod Emilevich explains his system of work:

"26. Principles of biomechanical perspective upon human nature should be placed at the core of the acting system. In this sense, cultivation of excitement (an ability to reproduce a given task in emotions, in movement and in words) in actors is carried out in such a way to enable mental processes to be a result of physical virtue. 27. Biomechanical system of play is based on the accurate appearance of excitement caused by the correct position of the actor in space. At the same time, each moment the motion will be associated with a precise relationship to all the other surrounding characters and objects. 29. The material of the actors art is the actor himself. Therefore, we have in one person the material and its constructor... 30. Each and every element of acting is necessarily (vitally) composed of three invariable phases: INTENTION, REALISATION AND REACTION INTENTION is the intellectual assimilation of a task prescribed externally (by the dramatist, the director, or the initiative by the performer). REALISATION the cycle of volitional, mimetic reflexes (comprise all movements performed by the separate parts of the actors body and the movements of the entire body in space) and vocal reflexes; REFLEX EXCITABILITY is to reduce to the minimum the process of understanding the task (simple reaction time) 31. It is the very excitement that makes the difference between an actor and a marionette, that which enables the actor to infect the spectator and cause his counter-excitement. This counter-emotion which comes from the spectator at the same time feeds, fuels the continuation of play (state of ecstasy.) (, 1998, 47-48)

It is important to reemphasise the tendency to reduce means of expression, where the actor uses only movements and gestures which are sufficient to send a message to the spectator. Moreover, movements need to be rationalised to reduce the actors fatigue, which increases his fitness and expressive power. It is clear in the first volume of the book Meyerhold Speaks/Meyerhold Rehearses what Vsevolod Meyerhold is interested in when working with actors. Some of the indications he gives to the actors while working at the anthological production of The Inspector General are:

... If in Rogonosac I worked more on rakurses, here in The Inspector General we will focus on the play with hands... For this play, it is very important to observe our hands... There are no heightened tones. Words pour, pour out without changes. Youre raising your voice to no avail. A little higher in baritone register, a little nasal. In one tone, there is almost no intonation. Monotonous, terribly monotonous... ... Hlestakov, go much slower, much slower... ... Ivan Alexandrovich, you should lower it fast, so that the whole scene is immediately lower in regard to sound... The play is going, and the tonality is not that. ... It is better that all movements are with body, not hands. When you move on to gesticulation, the head movement will be lost... ... Our biomechanical laws say: there should be no gesture made, if I dont stand in the spot. Stoppage left leg and right arm. When the leg is bent rakurs is good, when the leg is straight it is not artistic. ( , 1993, 101 - 147)

4. DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE ANTIPODEAN SYSTEMS In one of his books of notes from the later period, somewhere around 1912, Stanislavski writes: My system will be criticised for trying to expel conditionalities, stencils from art, since it believes that all that is conditional is not art, but craft. But all other stagecraftsmen will not acknowledge the beauty of nature, but they acknowledge the beauty of the very ugly matrix. To devaluate my viewpoints they will surely call me a realist, naturalist, etc. They will say that I am a photographer, because I am involved in the greatest beauty nature, and they are refined men of culture, because they work with the most perfect of natures copies with actorial conditionality and stencil. No, I reject no schematisations, nor stylisations, nor many other ...ations yet unborn, but I will set one condition. Let these ...ations live in the soul of the one who does them. Note from the book no. 981, l.12 " (, 1986, II, 8-9)

This note clearly shows the kind of opposition to his system he faced with and what exactly he had a need to defend. One of the people he makes an allusion to in this and other notes of similar content is Meyerhold himself, who, in his public appearances, claims that Stanislavskis method is harmful to the psycho-physical health of the actor. The hypnotic triggering of the unconscious in Stanislavskis System

becomes psychological torture for the actor in search of spontaneity, which, quite contradictorily, often leads him into spasm, contrary to Meyerholds intention-realisation-reaction, which is essentially, and quite contradictorily again, much more natural. By calling into question the control of an actor who is overwhelmed by emotions, Meyerhold explains his position in the following way: Any psychological state is conditioned by certain physiological processes. By finding the correct solution for his physical state, the actor enables a situation of excitability which infects the spectator, involves him into the actors play and represents the essence of his play... With such a system of appearing feelings, the actor always has a solid ground: a physical precondition. (Meyerhold, 1976, 168) Meyerholds way is more difficult in regard to adopting the technique, but it is safer for the actor and the final result. The actors orientation from the inside outward certainly does not vouch for manifestation of the correct gesture, facial expression, particular way of speech and in general, the construction of a character in the direction of a complete transformation. The actors who use Stanislavskis system in its original form or translated to the language of the American theatre in several different versions (Strasberg, Adler, Luis, Meisner), with emphasis on believing or doing, nevertheless, cannot be sure that they have always acted what they have intended to, with domination of privacy and repetition of expressive means. This is so because the system is based on psychology, which, as Meyerhold warns, cannot provide a definite answer to a whole number of questions.(Ibid.) An actor who is overwhelmed by panic onstage can be compared to a cyclist who has lost selfconfidence. In a calm state the cyclist probably knows that the instinct of self-preservation will save him. Yet, when losing balance, it is necessary to turn the handlebars to hold both himself and the bicycle in vertical position. But the damned nervousness and fear can unarm the most powerful habit of self-preservation. In a moment of poor concentration, the cyclist works hard with his legs, but loses the control over the bicycle, a tree draws him and the cyclist feels that he is sent flying, but cannot avoid it and crashes into the tree. This is how an actor feels, that he is not doing what he is supposed to do, but it lessens not his down spiral, feeling that he is collapsing, but having no way to stop it. Note from book no. 3319, l. 21-22 (, 1986, II, 13)

Therefore, Meyerhold advocates a process quite opposite: from the outside inward. He gives examples of the intuitive arrival at such an approach by Coquelin, Bernhardt, Chaliapin, among others, who are characterised by outstanding mastership. But, for Stanislavski, quite on the contrary, they are examples of craftsmen. Konstantin Sergeyevich wrote a lot about craftsmanships harmful effect on the theatre and the actor: C r a f t s i m p l i f i e s a t h e a t r i c a l p i e c e a l o t. For example, Evreinov performance in the centre of the theatre. He has come up with a jocular form and staging. Instead a content for this form a general-actorial ritual, which the audience takes for a truly abstract art. No one will say anything against such content. The audience feel good they worry about nothing, and the actor feels good the craft is comfortable. And for the director bliss. The hardest part of his work getting an insight into the soul of the drama, the actor, etc. has been substituted for a stencil. He has designed something fascinating (a formula, thesis, etc.) and everyone says how fantastic!... Meyerhold, Reinhardt, Evreinov they are like that. And the Meiningenians are completely different. They were engaged with the essence, the only difference was that they started from the outside inward. Note from book no. 782, l. 11-12 (, 1986, II, 34) These notes by Stanislavski appeared in the later period of his work in the theatre, together with all kinds of oppositions to him and his system. This coincided with his doubts and dilemmas about his own system of the actors work on himself and his role. It is terrible in our work that in an old role and monologue, one loses inner essence. In the beginning, you remember the words mechanically or, better to say, your tongue utters them absolutely unconsciously, and then, only when the entire phrase has already been spoken out, - you start to understand the inner meaning. The word comes before the feeling, the tongue before the soul, (1986, II, 11) Stanislavski wrote practically at the same time. These dilemmas of his, perhaps without his full awareness, pinpoint the main problems of his system: unreliability of creating in the process of working on oneself and the role, the variable results of performances in the sense of losing the strand of the role and character over the time, as well as insufficient self-control when the subconscious takes over the actor and he can no longer restrain his emotions or control his actions, so his movements and gestures fall out of the arranged structure. Meyerholds system protects the actor and play from these dangers and vouches for invariable results. His method of creating a frame for the play along with a meticulous design of structure, protects the actor and the director of having the play fall apart, at the same time providing the actor with huge

creative space to fill the frame and improvise in everyday search for new nuances in the inner action protected by so tightly fixed external action. The reserves European actors have in regard to Meyerholds biomechanics refer to the inorganic way of working on the gesture, speech, facial expression. For them, this artificial approach is a torture. But it only lasts as long as it takes the actor to bring the form to perfection. It is important to hold on until the appearance of feelings. The Mechanics is a condition for an actors freedom, says Robert Wilson. ( , 1999, 145-146) But if the external action is fixed in such a way that it seems too artificial, and the movements are visually attractive and display the actors great ability in working with his body, but do not give the activity a chance to become more natural and enable the development of an internal life of the actor on the way to accomplish his role completely, it will remain nothing but a perfect technical performance which will never arouse feelings with the actor and will leave the spectator indifferent.

5. THE POSSIBLE FUSION POINTS Here, we can mention Barba and Savareses vision of the organic unity of body and thought, through rejection of stereotypes, reflex reactions and superficial and false spontaneity, and acquiring a quality of true spontaneity. It is, apparently, possible only through the fusion of these two antepodean systems. But, in order to achieve this, we need an actor who has mastered not only the technique of Stanislavski or his American successors, but also the technique of Meyerhold and his biomechanics. An actor who has gone through the process of work on the role in both directions would indeed be ready to develop an awareness of the duality of presence and representation and explore the po ssibilities offered by the interspace. The interspace would be impossible to reach through Stanislavski alone (despite the ideal of reaching the point where a cultivated body would be used to express the inner life in a role), or through Meyerhold alone (despite the assumption that the strictly defined form, with its biomechanical rules, yields feelings and thus brings such a form to life and impregnate it). Therefore, the future actor should be educated in both systems, with a full awareness of all their advantages and disadvantages. I believe that Meyerholds system should be taken as the base for the fusion, and that only an absolute mastery of his technique can provide grounds for exploring potentials of both systems, whereas we assume that the actor has already gained the experience of working in Stanislavskis system, that he has studied his approach and recognised all problems. By adopting Meyerholds technique he would practically learn how to avoid all weaknesses of Stanislavskis practice. Education is absolutely necessary for this, since an actor who has not acquired training in biomechanics will not be able to follow the process nor to work using Meyerholds method.

Such an approach is independent of dramaturgy. It includes analysis and all its stages suggested by Stanislavski and further work on the text and movement from Meyerholds point of view. Thus, the actor would be given back his position of a creative factor not only in the segment of performance but also in the creation of the role, through a search for the most expressive form for the content which has already been defined, subsequently taking the same road back to reach its reawakening inside of him. However, to get to this point and to bring the entire process of working on the form to its ultimate aim awakening of feelings, the actors body has to find a fine balance between the economy of movements, acrobatic and gymnastic skills and master the work with body which stems from the sources of realism, that is, to reduce the form in order to facilitate an easier and more persuasive return to the content. In this way the extremes of Meyerholds approach could be avoided (Taylor and tailoring of the actors movements). Furthermore, in this way actors would remain on the safe distance from the dangers of marionettisation (Craig), acrobatism (Tairov), overacting and the bare form of speech, while otkaz (rejection, refusal key element in Meyerholds work) would be reduced, which would distance it from the other extreme end, to build the house of the theatre on the foundations of psychology, where actors play starts with a passion of building a sand castle and ends in defeat, in the form of the first wind or merciless wave of his nature. The ideal of such a method of work would be a play which is in its essence made after Meyerhold, but for which everyone believes it is a pure Stanislavski. In a certain way, Stanislavski himself started feeling and wishing this at one point, only it seems that he did not know how to reach it. He wrote this down in one of his books of notes: The character should be approached from both sides. At the beginning one should develop internal psychological personality and character, that is, play the role taking ones own self as the starting point. Especially, one should develop external personality through visual and muscle memory. The moment of merger of internal and external personality is very hard and delicate: when you start to think about the outside you start breaking. And vice versa, when you start thinking about the inside personality collapses. It is a time of desperation and confusion. It is hard to force a merger in this process. It is necessary to give it time, a period determined by nature, during which, with the right chemistry, the merger will occur. When they merge (usually as soon as the twentieth performance), then you stop thinking about the personality and it spills out as much as it should following the usual association. Note from Book No.927 l. 4-5 (, 1986, II, 22)

The free time determined by nature he speaks about, the chemistry which arrives so late, with this new method would be programmed or at least more and more easily predictable. The phases in the fusion of the two systems could be the following: After an individual analysis of dramaturgical material, which is the base of the play, the director makes an extensive analysis with his cast, which includes all phases suggested by Stanislavski. Carving the text and hacking it to Bits and Tasks, defining names of Bits, defining the Tasks using the formulation Im being..., opening the Given Circumstances, developing the relationship with the partner, discussing the germ of the role and all the other elements of analysis. The second phase of reading rehearsals takes us back to the form, that is, work on the aspect of HOW. This requires a development of the intonation of the roles how it will sound. This is where embodiment starts, the development of the relationships through form. A sound equivalent is sought for every mental state defined by the text or its remark, concept or its demand, as well as identified intention and task. Let us take as an example a monologue in which the character is nervous. This state of nervousness can be built with staccato speech tempo, baritone voice, fast rhythm, emphasised vowels, etc. We could look for a key word or a reappearing word. These are no accidents but the authors givens. Such a word is almost invariably the very essence of the monologue and then we can think about how to take it out of the unit of speech and articulate it in such a way as to make it the very centre of the monologue. The form of speech, the vocal line of the monologue which is well defined will lead to the sought nervousness. Once such a musical score of the play has been built, yet not arbitrarily and as some kind of vocal exhibitionism, but grounded on a profound understanding of the subject matter, psychology and all the interpersonal relationships between characters to the most subtle of nuances, mise-en-scene rehearsals can begin. Here, the actors work on the biomechanical preparations, every day, with dedication and a laboratory approach. After each training session, they search for the correct form which can best express the blueprint designed at the table, during the reading rehearsals. However, since the actors together with the director were involved in building the relationships, defining intentions and tasks, they are able to find the correct form of acting, the correct expression to build the relationships. The tendency of every actor trained in Stanislavskis technique is to search, on stage, for the material inside his soul rather than in his body. It is a great struggle of subconscious mechanisms with the conscious technique of acting. It is important to keep a vigilant eye for any sign of deviation and keep pushing the actor back to the road of outside, stimulating his attitude towards himself in the outside direction, with an awareness of what his actions look like. The work on the tempo-rhythm should also be carried out in a musical way, precisely and with a plan, not intuitively. All the while, the actor returns regularly to the Aims and Tasks, the Magic If, Given Circumstances, inspiring Im being... motivations, so that the form does not lead him away from the

content, which he should go back to, that is, which is to be reborn through taming, at the beginning of an artificial articulation of the body and speech. Well matched movement and sound, tone, tempo-rhythm of speech, rehearsed until we find the natural in the unnatural, the comfortable in the uncomfortable, balance in unbalance, gives back to the actor the freedom to create the intimate life of the character he interprets. But the armature of the play is so firm and unchangeable two weeks before the premiere that the actor cannot widen the space of his acting, but only deepen it. So, the play can have a precise duration (as if it is an opera done after a music score where extensions or shortening of single scenes are not possible) and the same visual aspect elaborated to the tiniest detail, with surgical precision, to send to the spectator such a message that is unambiguous or associative, and each performance can be different in the way the armature is built over, where relationships are established in a new way, again, with the stability of the result which covers them and at the same time shows their inspiration. But, a form well matched, always yields contents, well matched sound always stimulates a spiritual state. This is a regularity which vouches for the result and with mathematical precision awakens, but also controls, the psychology of the actor.

6. THE PROBLEMS OF THE APPROACH IN REPERTOIRE THEATRES It would be very difficult to implement this process of work on a play in repertoire theatres, considering the generation gap, differences between different schools from various periods of thought about the theatre and methods of work on the role, the level of physical fitness for body expression, as well as the readiness and desire to use a newly suggested system. Some actors have no knowledge of Meyerholds theatre language, so they need training in biomechanics, which requires time and patience, as well as a general consent of the whole team to be absolutely dedicated to this approach to work. The situation could be further aggravated if the cast consists of people who have biomechanical education and are familiar with working from form to content and those who lack this knowledge. In such a case, they are disinclined to the directors educational work with the other members of the company, because they feel they have some kind of advantage, which discourages them to search expression and can often leave them at the elementary level of knowledge about this method of work. Thus, such plays can turn into showcasing a way of thinking about the theatre rather than an authentic result and the latest work of an ensemble or a director. However, one thing is certain: an actor who has no previous training in Meyerholds system cannot work on a play like this. Therefore, we suggest an audition to check physical fitness, followed by a trainingworkshop which starts several months before the commencement of work with the director on the text, and extends during the preparation of the play, integrating in this phase the members of the team who have previous knowledge of biomechanics and experience of using Meyerholds method.

7. CONCLUSION The relationship between Stanislavski and Meyerhold is similar to the relationship between lovers who could not live with or without one another. They were constantly fighting and making up. They could not stand working together for long, but they always followed with great care and interest and often supported each others work. They wrote each other letters that they never replied to, they made appointments but did not keep them, complained to friends (mostly to Chekhov) about the attitude of the other one, quarrelled in their own notes with the other one. But they always defended each other in public, broke the ground for one another, supported each others attempts to find something new, came to the other ones rescue, protected each other from outside attacks, were careful not to stain their mutual past. And, Meyerhold never forgot and ceased to mention Stanislavski as his teacher and that without him, Meyerholds further work and exploration would have been impossible. All the aforementioned seems to show the natural way to the fusion of their antipodean systems, which seem to have so much in common, a fact that Meyerhold was more aware of than Stanislavski. It is because Meyerhold went through Stanisalvskis school/psycho-technique, while Stanislavski never went through Meyerholds biomechanics. Had he done so, he would have known that the answer to some of his dilemmas was in this very extension, which does not necessarily cancel his system the way Meyerhold did, but can integrate it and provide it with a new quality.

REFERENCES: 1. Mejerholjd, V.E. 1976. O pozoritu. Beograd: Nolit. 2. Stanislavski, K. S. 1982. Sistem. Beograd: Partizanska knjiga. 3. Me, .. 1998. . -: 4. Me, .. 1976. . : . 5. Me, .. 1968. , , , . : . 6. Me, .. 1913. . .- : . 7. Me, .. 2000. . : ... 8. , .. , .. 1993. Me 1 ( 20- ). : . . . 9. , .. , .. 1993. Me 2 ( 30- ). : . . . 10. , .. , .. 1998. . . Me, 1. : ...

11. , .. , .. 2006. . . Me, 2. : ... 12. , .. , .. 2000. . . Me . : ... 13. , . 1967. . : . 14. , .. 1990. : 2- . : . 15. , . 1981. Me. : . 16. , .. , .. 1995. Me . : . 17. . .. 1997. . : . . . 18. , .. 1954. . : . 19. , .. 1954. . 1. : . 20. , .. 1955. . 2. : . 21. , .. 1957. . : . 22. , .. 1945. . : . 23. , ..1986. I (1888-1911). : . 24. , ..1986. II (1912-1938). : . 25. , .1995. . : . 26. , . 1998. . : -. 27. , .. , .. 1999. ( ). : . 28. Barba, E. i Savareze, N. prir. 1996. Renik pozorine antropologije: tajna umetnost glumca. Beograd: Fakultet dramskih umetnosti. 29. Otto-Bernstein, K. 2006. Absolute Wilson: The Biography. New York: Prestel.

Вам также может понравиться

- StanislavskiДокумент14 страницStanislavskiimru2Оценок пока нет

- Vsevolod Meyerhold Actor As The Texture of TheatreДокумент11 страницVsevolod Meyerhold Actor As The Texture of TheatreLizzieGodfrey-Gush0% (1)

- Stanislavski Essay - KJ GatenbyДокумент10 страницStanislavski Essay - KJ GatenbyKeira GatenbyОценок пока нет

- An Explanation and Analysis of One Principle of Meyerhold's Biomechanics TormosДокумент15 страницAn Explanation and Analysis of One Principle of Meyerhold's Biomechanics TormosLizzieGodfrey-GushОценок пока нет

- After The RehearsalДокумент24 страницыAfter The RehearsalFlorin FrăticăОценок пока нет

- Michael Chekhovs Golden HoopДокумент6 страницMichael Chekhovs Golden HoopRobertoZuccoОценок пока нет

- Modern DramaДокумент15 страницModern DramaRangothri Sreenivasa SubramanyamОценок пока нет

- Portia - 2.1 Monologue CutДокумент2 страницыPortia - 2.1 Monologue CutKaiylah WattsОценок пока нет

- Woyzeck Lesson PlanДокумент4 страницыWoyzeck Lesson PlanCaleb S. GarnerОценок пока нет

- Model Proforma For Income CertificateДокумент1 страницаModel Proforma For Income CertificateSreejita KoleyОценок пока нет

- Adler, Anton ChekhovДокумент3 страницыAdler, Anton ChekhovTR119Оценок пока нет

- Michael ChekhovДокумент2 страницыMichael Chekhovapi-541653384Оценок пока нет

- An-Sky's The Dybbukthrough The Eyes of Habima's Rival StudioДокумент29 страницAn-Sky's The Dybbukthrough The Eyes of Habima's Rival StudioRay MoscarellaОценок пока нет

- Jerzy Grotowski 1933-1999Документ5 страницJerzy Grotowski 1933-1999Jaime SorianoОценок пока нет

- Big Dreams Interview Barba PDFДокумент6 страницBig Dreams Interview Barba PDFBalizkoa BadaezpadakoaОценок пока нет

- Embodied PracticeДокумент3 страницыEmbodied PracticeOdoroagă AlexandraОценок пока нет

- Twenty First Century Russian Actor Training Active Analysis in The UK-2Документ16 страницTwenty First Century Russian Actor Training Active Analysis in The UK-2Maca Losada Pérez100% (1)

- Anatoly Efross Pinciples of Acting and Directing20190622-80472-17xesvk PDFДокумент18 страницAnatoly Efross Pinciples of Acting and Directing20190622-80472-17xesvk PDFHaraОценок пока нет

- A Concise Introduction To Actor TrainingДокумент18 страницA Concise Introduction To Actor Trainingalioliver9Оценок пока нет

- The Seagull 1Документ4 страницыThe Seagull 1Jaimie LojaОценок пока нет

- A Selection of Nordic Plays Represented by Nordiska ApsДокумент34 страницыA Selection of Nordic Plays Represented by Nordiska ApscbanОценок пока нет

- Glass Menagerie MonologueДокумент2 страницыGlass Menagerie MonologueDRocker9Оценок пока нет

- GSP Callback MonologuesДокумент1 страницаGSP Callback MonologuesJillian HannaОценок пока нет

- Meyerhold & Mayakovsky - Biomechanics and The Communist UtopisДокумент27 страницMeyerhold & Mayakovsky - Biomechanics and The Communist UtopisViv BolusОценок пока нет

- KIRBY, Michael. Acting and Non-Acting PDFДокумент11 страницKIRBY, Michael. Acting and Non-Acting PDFcarrijorodrigoОценок пока нет

- Sandbox by Edward AlbeeДокумент6 страницSandbox by Edward AlbeeMark Mirando100% (2)

- GestusДокумент1 страницаGestusapi-574033038Оценок пока нет

- Meyerhold's BiomechanicsДокумент9 страницMeyerhold's BiomechanicsBogdan BortaОценок пока нет

- Grotowski Movement TheoriesДокумент5 страницGrotowski Movement TheoriesJaime Soriano67% (3)

- May 2018 Full Audition PacketДокумент20 страницMay 2018 Full Audition PacketKevin Dale HarrisОценок пока нет

- 0015 Games in Education and TheatreДокумент10 страниц0015 Games in Education and TheatreMethuen DramaОценок пока нет

- The Theatre of Pina Bausch. Hoghe PDFДокумент13 страницThe Theatre of Pina Bausch. Hoghe PDFSofía RuedaОценок пока нет

- Composition Fall05Документ6 страницComposition Fall05Juciara NascimentoОценок пока нет

- The Routledge Companion To Jacques Lecoq: Mark Evans, Rick KempДокумент9 страницThe Routledge Companion To Jacques Lecoq: Mark Evans, Rick KempMatthewE036Оценок пока нет

- Art As VehicleДокумент3 страницыArt As VehicleJaime SorianoОценок пока нет

- Meyerhold and StanislavskyДокумент47 страницMeyerhold and StanislavskyDavid Herman100% (1)

- Barba 2002 - Essence of Theater PDFДокумент20 страницBarba 2002 - Essence of Theater PDFbodoque76Оценок пока нет

- Henry Johnson RevДокумент78 страницHenry Johnson RevJoana Estebanell Milian100% (2)

- Real Thing ProgramДокумент6 страницReal Thing ProgramRay RenatiОценок пока нет

- Cue Synopsis - Skin of Our Teeth Lighting - FinalДокумент5 страницCue Synopsis - Skin of Our Teeth Lighting - FinalCamcas CervantesОценок пока нет

- Viewpoints Training - ActingДокумент4 страницыViewpoints Training - ActingCarina Bunea100% (1)

- Richard BoleslavskyДокумент13 страницRichard BoleslavskyfwekmОценок пока нет

- Gestus WorkshopДокумент1 страницаGestus WorkshopantonapoulosОценок пока нет

- Expressionism and Physical Theatre - Steven BerkoffДокумент1 страницаExpressionism and Physical Theatre - Steven Berkoffapi-364338283Оценок пока нет

- Coaching Actors PDFДокумент8 страницCoaching Actors PDFAntonio VettrainoОценок пока нет

- Marius Von Mayenburg ThesisДокумент152 страницыMarius Von Mayenburg ThesisMădălin Hîncu100% (1)

- Authoring Performance The Director in C PDFДокумент13 страницAuthoring Performance The Director in C PDFUmaHalfinaОценок пока нет

- Antigone TextДокумент38 страницAntigone Texttrish_luaОценок пока нет

- Robert Wilson - Guardian InterviewДокумент2 страницыRobert Wilson - Guardian InterviewTR119Оценок пока нет

- Michael ChekhovДокумент3 страницыMichael ChekhovMariana SilvaОценок пока нет

- Autobahn: by Neil LabuteДокумент2 страницыAutobahn: by Neil LabuteMiruna MariaОценок пока нет

- Meyerhold's Key Theoretical PrinciplesДокумент27 страницMeyerhold's Key Theoretical Principlesbenwarrington11100% (1)

- Conspect Katie MitchellДокумент5 страницConspect Katie Mitchellion mircioagaОценок пока нет

- Ib Theatre IntroДокумент8 страницIb Theatre IntroRobert RussellОценок пока нет

- Meyerhold'sДокумент15 страницMeyerhold'sSquawОценок пока нет

- Suzuki TadashiДокумент2 страницыSuzuki TadashiMayan BarikОценок пока нет

- Theoretical Foundations of Grotowski's Total Act, Via Negativa, and Conjunctio OppositorumДокумент15 страницTheoretical Foundations of Grotowski's Total Act, Via Negativa, and Conjunctio OppositorumJaime Soriano100% (1)

- The Nation Is Coming To Life': Law, Sovereignty, and Belonging in Ngarrindjeri Photography of The Mid-Twentieth CenturyДокумент21 страницаThe Nation Is Coming To Life': Law, Sovereignty, and Belonging in Ngarrindjeri Photography of The Mid-Twentieth CenturyHaneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- (Modernist Latitudes) Lee, Steven Sunwoo-The Ethnic Avant-Garde - Minority Cultures and World Revolution-Columbia University Press (2015)Документ300 страниц(Modernist Latitudes) Lee, Steven Sunwoo-The Ethnic Avant-Garde - Minority Cultures and World Revolution-Columbia University Press (2015)Haneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- Saturdays at Midnight, With An Encore Sundays at 10am ET.: JanuaryДокумент1 страницаSaturdays at Midnight, With An Encore Sundays at 10am ET.: JanuaryHaneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- Shearman 01Документ32 страницыShearman 01Haneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- Call For Papers Intersections of Art, Science, and Technology in Soviet Film and CultureДокумент2 страницыCall For Papers Intersections of Art, Science, and Technology in Soviet Film and CultureHaneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- Hans Memling Life and WorkДокумент38 страницHans Memling Life and WorkHaneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- Benjamin NOYS - Malign VelocitiesДокумент26 страницBenjamin NOYS - Malign VelocitiesHaneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- Case Note - Two Bronze Animal HeadsДокумент7 страницCase Note - Two Bronze Animal HeadsHaneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- French Cultural Studies 1998 Rosello 337 49Документ13 страницFrench Cultural Studies 1998 Rosello 337 49Haneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- Vanishing Points and The Technicity of The FutureДокумент4 страницыVanishing Points and The Technicity of The FutureHaneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- Didi Huberman Artistic Survival. Panofsky vs. Warburg and The Exorcism of Impure TimeДокумент14 страницDidi Huberman Artistic Survival. Panofsky vs. Warburg and The Exorcism of Impure TimeHaneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- Socialist Senses Film and The Creation of Soviet SubjectivityДокумент30 страницSocialist Senses Film and The Creation of Soviet SubjectivityHaneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- Mediated Post-Soviet NostalgiaДокумент278 страницMediated Post-Soviet NostalgiaHaneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- Didi Huberman Artistic Survival. Panofsky vs. Warburg and The Exorcism of Impure TimeДокумент14 страницDidi Huberman Artistic Survival. Panofsky vs. Warburg and The Exorcism of Impure TimeHaneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- MOSCOW Learning From MoscowДокумент8 страницMOSCOW Learning From MoscowHaneen HannouchОценок пока нет

- Brainstorm Nouns and VerbsДокумент100 страницBrainstorm Nouns and VerbsjaivandhanaaОценок пока нет

- Hannah Enanod - WS 7 Meaning of CurriculumДокумент2 страницыHannah Enanod - WS 7 Meaning of CurriculumHannah EnanodОценок пока нет

- 1-Page Future Self CheatsheetДокумент1 страница1-Page Future Self CheatsheetaminaОценок пока нет

- Portfolio For Classes IX & XДокумент17 страницPortfolio For Classes IX & XMuskanОценок пока нет

- Verbal and Nonverbal Communication and Their Functions-3 - Group 42 GE-PC - PURPOSIVE COMMUNICATIONДокумент6 страницVerbal and Nonverbal Communication and Their Functions-3 - Group 42 GE-PC - PURPOSIVE COMMUNICATIONLowell James TigueloОценок пока нет

- Auditory and Combined ArtsДокумент2 страницыAuditory and Combined ArtslunatheworldОценок пока нет

- The STOP MethodДокумент1 страницаThe STOP MethodTony HumphreysОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan ArraysДокумент11 страницLesson Plan ArraysErika MytnikОценок пока нет

- Idt Question BankДокумент2 страницыIdt Question BankmanjunatharaddiОценок пока нет

- Lecture 1 - Curriculum ProcessДокумент3 страницыLecture 1 - Curriculum Processapi-373153794% (17)

- REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE FTF LearningДокумент6 страницREVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE FTF LearningHuolynehb TiagoОценок пока нет

- Professional Experience Context StatementДокумент3 страницыProfessional Experience Context Statementapi-512442435Оценок пока нет

- Learning Plan: Learning Outcome Topic Week No. Learnig ActivitiesДокумент2 страницыLearning Plan: Learning Outcome Topic Week No. Learnig ActivitiesJereek EspirituОценок пока нет

- Unit 4 Part 1 Proposal MemoДокумент3 страницыUnit 4 Part 1 Proposal MemoMarshall VilandОценок пока нет

- Anne Bamford Essay 1 PDFДокумент4 страницыAnne Bamford Essay 1 PDFNelia Mae DurangoОценок пока нет

- Enquiry EssayДокумент2 страницыEnquiry EssayisoldeОценок пока нет

- Nuon Chheang Eng - The OD Letters Case Analysis FormДокумент2 страницыNuon Chheang Eng - The OD Letters Case Analysis FormChheang Eng NuonОценок пока нет

- Asch 1951 Jenness 1932 Sheriff 1936Документ1 страницаAsch 1951 Jenness 1932 Sheriff 1936FolorunshoEmОценок пока нет

- Expert SecretsДокумент2 страницыExpert SecretsJesse Willoughby100% (1)

- Fragile World On The SpectrumДокумент4 страницыFragile World On The SpectrumAnastasiya PlohihОценок пока нет

- Extension Education Is An Applied Behavioural Science, The Knowledge of Which Is Applied To BringДокумент12 страницExtension Education Is An Applied Behavioural Science, The Knowledge of Which Is Applied To BringKarl KiwisОценок пока нет

- Fieldstudy 1 - Episode8-ObservationДокумент2 страницыFieldstudy 1 - Episode8-ObservationMission Jemar B.Оценок пока нет

- 4 Philippine Politics and Governance 11 2 60minsДокумент2 страницы4 Philippine Politics and Governance 11 2 60minsGerald RojasОценок пока нет

- Article AdaptativeProjectManagement PDFДокумент8 страницArticle AdaptativeProjectManagement PDFMohammad DoomsОценок пока нет

- Six Essential Chapters in A Science AssignmentДокумент3 страницыSix Essential Chapters in A Science AssignmentLarry kimОценок пока нет

- Machine Learning ReportДокумент128 страницMachine Learning ReportLuffy RajОценок пока нет

- What Are The Expected Tasks You Have Successfully AccomplishedДокумент1 страницаWhat Are The Expected Tasks You Have Successfully AccomplishedImmortality Realm67% (18)

- Top 10 MBA HR Interview QuestionsДокумент14 страницTop 10 MBA HR Interview QuestionsJimmy Graham100% (1)

- Learning Episode 17Документ4 страницыLearning Episode 17mariovillartaОценок пока нет