Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Epolar System Enterprise Pte LTD and Others V Lee Hock Chuan and Others (2003) 2 SLR (R) 0198

Загружено:

lumin87Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Epolar System Enterprise Pte LTD and Others V Lee Hock Chuan and Others (2003) 2 SLR (R) 0198

Загружено:

lumin87Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

198

SINGAPORE LAW REPORTS (REISSUE)

[2003] 2SLR(R)

Epolar System Enterprise Pte Ltd and others v Lee Hock Chuan and others

[2003] SGCA 10

Court of Appeal Civil Appeal No 109 of 2002 Yong Pung How CJ, Chao Hick Tin JA and Judith Prakash J 18 February; 21 March 2003 Tort Nuisance Private Nuisance Fire damage Fire caused by faulty fuse on property Whether landlord liable in nuisance Tort Nuisance Private Nuisance Standing to sue Whether pleadings disclosed sufficient capacity to sue Person(s) pleading as occupying and carrying on business Persons pleading as owners Whether this disclosed sufficient standing to sue Facts A fire, caused by a faulty fuse, broke out at the respondents property (No 25) and spread to the neighbouring properties of the appellants, causing damage to them. The respondents property was leased to tenants, which in turn was sub-let to another party. The appellants, owners and occupiers of the neighbouring properties sued the respondents in nuisance and negligence, contending that the respondents had been in vacant occupation of No 25 when the faulty fuses had already been in place, and thus should have rectified the fault. The action was dismissed by the High Court, on the grounds that the appellants had not proven vacant possession by the respondents at any time, and that the appellants pleadings were defective and did not disclose a sufficient standing for them to sue in private nuisance. The appellants appealed. Held, dismissing the appeal: (1) A plaintiff should have a right to occupation of the affected land for him to be able to sue in private nuisance. The appellant occupiers had pleaded their capacity as occupying and carrying on business, and they were in actual possession of the premises in their own right. As the fire had caused substantial damage to the properties, the appellant owners reversionary interest was affected. Thus, the appellant occupiers and owners had a right to claim in private nuisance: at [15] to [18]. (2) The appellants claims failed as at that time, No 25 was in the exclusive possession of the respondents tenants. It was not established that the potentially dangerous situation was brought about by the respondents or that they knew about it and did nothing: at [7] and [19]. Case(s) referred to Foster v Urban District Council of Warblington [1906] 1 KB 648 (folld) Hunter v Canary Wharf Ltd [1997] AC 655 (folld)

[2003] 2SLR(R)

Epolar System Enterprise Pte Ltd v Lee Hock Chuan

199

Khorasandjian v Bush [1993] QB 727 (refd) Malone v Laskey [1907] 2 KB 141 (folld) Newcastle-Under-Lyme Corporation v Wolstanton Limited [1947] 1 Ch 92 (folld) Shelfer v City of London Electric Lighting Company [1895] 1 Ch 287 (folld) Gn Chiang Soon (Gn & Co) for appellants; Cheong Yuen Hee (instructed), Govinda Gopalan and Cheong Aik Chye (Lim & Gopalan) for respondents. [Editorial note: The decision from which this appeal arose is reported at [2002] 2 SLR(R) 1025.]

21 March 2003 Chao Hick Tin JA (delivering the judgment of the court): 1 This was an appeal against a decision of the High Court dismissing the appellants claims for damages on account of a fire which started in the premises owned by the respondents but let out to tenants and which spread to the adjoining premises occupied/belonging to the appellants. We heard the appeal on 18 February 2003 and dismissed it. These grounds are issued, as certain pronouncements made by the court below, in relation to the tort of nuisance, require some clarification. The facts 2 The first to third appellants were the occupiers of factory premises Nos 21, 35 and 37, Senang Crescent respectively (Nos 21, 35, and 37) and were carrying on their businesses therein. The fourth and fifth appellants were the owners of Nos 35 and 37. The owner of No 21 was a party to the proceedings in the court below but had decided not to pursue the matter further. The respondents were the owners of No 25 Senang Crescent (No 25). The appellants sued in both negligence and nuisance. 3 On 20 February 1999, a fire broke out at No 25. At the time, the property was leased out by the respondents to Great Wall Interior Dcor Pte Ltd (Great Wall), which in turn had sublet the lower floor to Teamwood Decoration & Construction Pte Ltd (Teamwood). The cause of the fire would appear to be a short circuit in the wiring which generated sparks, igniting material in the front yard of No 25. Three fuses in the fuse box of No 25 were found to contain old copper wires (in Imperial measurement) not in use after 1978. These wires had a greater capacity than what was permitted for use and this had apparently resulted in the fuses not blowing to interrupt the flow of electricity. The fuse box was located in the front yard of No 25 occupied by Teamwood. 4 We should mention that there was an earlier action, in relation to the same fire, which was commenced by the owners and tenants of No 23

200

SINGAPORE LAW REPORTS (REISSUE)

[2003] 2SLR(R)

Senang Crescent against the respondents, as well as Great Wall and Teamwood (see Sim Chiang Lee v Lee Hock Chuan [2003] 1 SLR(R) 122). At the end of the trial of that action, the High Court dismissed the plaintiffs claim against the owners of No 25, the respondents herein, as well as their claim against Great Wall. But the court there held Teamwood liable in negligence for the damages caused by the fire. The decision was affirmed by this Court on appeal. 5 In the present action, the case as presented to the court below was that the three tampered fuses, with wire thickness greater than those in use after 1978, were installed sometime before 1978 or, at the latest, before 1991, ie, before Great Wall commenced occupation of No 25. The appellants alleged that the respondents, as the landlords of No 25, upon resuming possession of the premises from the previous tenant, and before leasing the property out to Great Wall, should have ensured that all electrical fittings were in order. In letting out the premises to Great Wall with the tampered fuses, the respondents were negligent and were thus liable for damages suffered by the appellants. 6 The trial judge found that the appellants had failed to establish that the respondents had breached any duty of care owed to them and dismissed the action. 7 In order to prove that the old wires were installed in the tampered fuses before Great Wall took possession of No 25, the appellants relied on the fact that the old wires were wires authorised before 1978 and such wires were no longer permitted to be in use after 1978. We did not think that this fact alone was sufficient proof that the tampered fuses must have been in place before 1978 or at any rate before 1991. We did not see how it necessarily followed that just because the wires were old, they must have been in place before 1991. While we accept that a licenced electrician would most likely have used wires currently authorised, a change of fuse wires could be undertaken by any handyman. Findings must be made based on evidence, and speculation does not constitute evidence. Great Wall and Teamwork should have been called to testify that they did not do anything with regard to the fuses. 8 In the light of the foregoing, the claim in nuisance could also not be sustained. At the relevant time, No 25 was in the exclusive possession of Great Wall and Teamwood. It was not established that the potentially dangerous situation, caused by the tampered fuses and the combustible material accumulated in the front yard of No 25, was brought about by the respondents or that they knew about it and did nothing. There was nothing to link the respondents to that state of affairs.

[2003] 2SLR(R)

Epolar System Enterprise Pte Ltd v Lee Hock Chuan

201

Who may claim in nuisance 9 In dealing with the claim in nuisance, the trial judge, in his judgment, advanced the following propositions:

[A] plaintiff who sues in private nuisance must first prove that he has an interest in land because nuisance is a tort against land. See The Law of Torts, Common Law Series, 2002 Ed, Ch 22 page 901 for a detailed historical background to this tort. Whatever the plaintiff may recover from the defendant depends on the interest that he (the plaintiff) has. Hence, the licensee in Malone v Laskey [1907] 2 KB 141 was held to have insufficient interest in land to sue the next door occupier in nuisance. It follows that the plaintiffs must plead and adduce evidence of their respective interests in land. The case for the first, second, and third plaintiffs in this case must fail from the outset because they claim as occupiers. That is clearly insufficient. The fourth, fifth, and sixth plaintiffs claim as owners. Not a single affidavit of evidence-in-chief was filed by any one of the six plaintiffs. If the owner is not in occupation, then he can only succeed if he can show that he had a right of immediate possession, or that he suffered damage in respect of his reversionary interest. See Shelfer v City of London Electric Lighting Co [1895] 1 Ch 287, 312, per Lindley LJ. Nothing to this effect was pleaded nor proved. The certified true copies of title deeds produced by the solicitors clerk only prove ownership at best, but, as I said, mere ownership is not sufficient, especially where, as in this case, it is not known who had possession or right to immediate possession of the premises known as 21, 35 and 37 Senang Crescent.

10 The tort of private nuisance protects the right of a person who has possession of land to enjoy his premises undisturbed. The essence of nuisance is a condition or activity which unduly interferes with the use or enjoyment of land: see Clerk & Lindsell on Torts (17th Ed, 1995) at p 889, para 18-01. Generally, only a person with a proprietary interest, whether by virtue of his freehold or leasehold interest, can bring proceedings. Thus, a tenant can sue. Where an owner has leased out his property, in order to be able to sue, he must prove that the nuisance has damaged or is likely to be adverse to his reversionary interest. As a rule, occupation per se will not suffice; there must be something more, something in the nature of proprietary interest or its equivalent. Therefore, an individual who is a husband, wife or lodger of the owner or lessee, who is at the premises with the permission of the latter, will have no cause of action even though he may be said to be in occupation. This principle is elucidated in the case of Malone v Laskey [1907] 2 KB 141 where the wife of the manager of a company entitled to live in the premises by virtue of his employment was held to be disentitled to sue in private nuisance. Sir Gorell Barnes P said (at 151):

Many cases were cited in the course of the argument in which it had been held that actions for nuisance could be maintained where a persons rights of property had been affected by the nuisance, but no

202

SINGAPORE LAW REPORTS (REISSUE)

[2003] 2SLR(R)

authority was cited, nor in my opinion can any principle of law be formulated, to the effect that a person who has no interest in property, no right of occupation in the proper sense of the term, can maintain an action for a nuisance arising from the vibration caused by the working of an engine in an adjoining house.

11 However, a person in de facto possession by way of exclusive occupation may be entitled to sue. This is illustrated by the case NewcastleUnder-Lyme Corporation v Wolstanton Limited [1947] 1 Ch 92 where a borough corporation, whose gas mains and pipes laid under roads were damaged due to soil movement caused by works at adjacent mines, was held to be entitled to sue for nuisance as the exclusive occupier. Evershed J said (at 106):

[T]hey have by force of the statute the exclusive right to occupy for the purposes of their statutory undertaking the space in the soil taken by the pipes and that (subterranean) part of the soil on which the pipes rest; but that exclusive right of occupation, which continues so long as the corporation carry on their undertaking, does not depend upon or involve the vesting in the plaintiff corporation of any legal or equitable estate in the land.

And at 109, Evershed J seemed to have endorsed the following statement in Salmond on The Law of Torts (10th Ed, 1945) at p 221:

There seems no reason why possession without title should not as a general rule be sufficient to enable a plaintiff to succeed in nuisance so that the jus tertii cannot be set up as a defence.

12 In Foster v Urban District Council of Warblington [1906] 1 KB 648 an oyster merchant who had set up a business on the lord of the manors shore was able to sue the defendant for damage caused by the discharge of sewage. He had carried on his trade removing and selling oysters for such a length of time that the court was willing to grant him relief. Fletcher Moulton LJ held (at 679) that:

[I]t is an unquestionable principle of our law that, where there has been long-continued enjoyment of an exclusive character of a right or a property, the law presumes that such enjoyment is rightful, if the property or right is of such a nature that it can have a legal origin.

13 In Khorasandjian v Bush [1993] QB 727, the English Court of Appeal attempted to relax somewhat the strict view on the question of entitlement to sue. There, the daughter was living in a house owned by the mother. She was pestered and threatened by unwanted telephone calls. Dillon LJ, giving the majority judgment, held that she had a cause of action in private nuisance. He felt that the court should reconsider earlier decisions in the light of changed social conditions. He said (at 734) it was:

[R]idiculous if in this present age the law is that the making of deliberately harassing and pestering telephone calls to a person is only

[2003] 2SLR(R)

Epolar System Enterprise Pte Ltd v Lee Hock Chuan

203

actionable in the civil courts if the recipient of the calls happens to have the freehold or a leasehold proprietary interest in the premises in which he or she has received the calls.

Peter Gibson J, dissenting, held it was wrong in principle that a mere licensee should be able to sue in private nuisance. 14 However, in Hunter v Canary Wharf Ltd [1997] AC 655 where the House of Lords had the occasion to review this entire area of the law, it overruled the majority decision in Khorasandjian v Bush and put a stop to the attempted departure from the strict position. At first instance, Judge Havery QC held (i) that interference with television reception is capable of constituting an actionable nuisance; (ii) but the plaintiff must have a right of exclusive possession of the land to be entitled to sue for private nuisance. The Court of Appeal reversed him on both points. On the second point, the Court of Appeal held that occupation of property as a home, as had the daughter in Khorasandjian v Bush, provided a sufficiently substantial link to enable the occupier to sue in private nuisance. This view was rejected by the House of Lords by a 4-1 majority. Lord Goff of Chieveley, after reviewing the authorities, concluded (at 692):

It follows that, on the authorities as they stand, an action in private nuisance will only lie at the suit of a person who has a right to the land affected. Ordinarily, such a person can only sue if he has the right to exclusive possession of the land, such as a freeholder or tenant in possession, or even a licensee with exclusive possession. Exceptionally however, as Foster v Warblington Urban District Council shows, this category may include a person in actual possession who has no right to be there; and in any event a reversioner can sue in so far his reversionary interest is affected. But a mere licensee on the land has no right to sue.

15 Thus for a plaintiff to be entitled to sue in private nuisance he must show an interest in land. There must be a right to occupation. 16 Reverting to the pleading in this case, we noted that the plaintiffs had clearly pleaded the capacity in which they were suing when they stated:

1. On 20 February 1999 (the eventful day) the 1st, 2nd and 3rd plaintiffs were occupying and carrying on their business and/or trade at No. 21, 35 and 37 Senang Crescent, Singapore, respectively (Nos 21, 35 and 37). 2. On the eventful day, the 4th, 5th and 6th plaintiffs were the owners of Nos 21, 35 and 37 respectively.

17 The trial judge said that the case for the first, second and third plaintiffs in this case must fail from the outset because they claim as occupiers. He seemed to have relied on the case of Malone v Laskey. But as seen above, Malone v Laskey was concerned with a pure licensee. The wife had no right of occupation. Here, however, the first three plaintiffs had

204

SINGAPORE LAW REPORTS (REISSUE)

[2003] 2SLR(R)

pleaded occupying and carrying on their business at the premises. They were in actual possession of the premises in their own right. They were certainly not in the position of the wife in Malone v Laskey nor the daughter in Khorasandjian v Bush. In our opinion, they were entitled to sue in accordance with the principle enunciated by Lord Goff in Hunter quoted in [14] above. 18 As regards the other appellants who were owners of Nos 35 and 37 (and of No 21 as well, although the owner did not appeal), the trial judge held that proof of ownership per se was not good enough to claim in nuisance. He was quite right to say that the owners must show that they had suffered damage in respect of their reversionary interest. But where there was, as in this case, clear evidence that the fire that began at No 25 had spread to Nos 21, 35 and 37 and caused substantial damage thereto, the reversionary interest of the owners was surely affected. Nuisance arising from smoke and dust may be transient and it would be difficult to establish permanent damage being caused thereby. But fire damage is permanent. Thus, the owners of Nos 21, 35 and 37 would have a right to claim in nuisance. This is illustrated in Shelfer v City of London Electric Lighting Company [1895] 1 Ch 287 where the defendant erected powerful engines and other works on land near to a house occupied by a lessee. The vibration and noise from the excavation works caused structural damage to the house and annoyance and discomfort to the lessee. The lessee and the reversioners brought separate actions and relief was granted to both. 19 Notwithstanding the foregoing, the appellants failed in their claim in nuisance against the respondents because, as stated above, they had not proved that the respondents were in any way responsible for the alleged nuisance. Reported by Chew Chin Yee.

Вам также может понравиться

- RSP Architects Planners & Engineers (Formerly Known As Raglan Squire & Partners FE) V Management Corporation Strata Title Plan No 1075 and Another (1999) - 2 - SLR (R) - 0134Документ32 страницыRSP Architects Planners & Engineers (Formerly Known As Raglan Squire & Partners FE) V Management Corporation Strata Title Plan No 1075 and Another (1999) - 2 - SLR (R) - 0134lumin87Оценок пока нет

- Chee Siok Chin and Others V Minister For Home Affairs and Another (2006) 1 SLR (R) 0582Документ52 страницыChee Siok Chin and Others V Minister For Home Affairs and Another (2006) 1 SLR (R) 0582lumin87Оценок пока нет

- CHNG Suan Tze V Minister For Home Affairs and Others and Other Appeals (1988) 2 SLR (R) 0525Документ46 страницCHNG Suan Tze V Minister For Home Affairs and Others and Other Appeals (1988) 2 SLR (R) 0525lumin87100% (1)

- Legal Profession ActДокумент154 страницыLegal Profession Actlumin87Оценок пока нет

- Re Singapore Symphonia Co LTD & Others - (2013) SGHC 261Документ4 страницыRe Singapore Symphonia Co LTD & Others - (2013) SGHC 261lumin87Оценок пока нет

- Adjudication Determination: Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act (Cap 30B, 2006 Revised Edition)Документ18 страницAdjudication Determination: Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act (Cap 30B, 2006 Revised Edition)lumin87Оценок пока нет

- BGVBF: (2007) SGCA 32Документ32 страницыBGVBF: (2007) SGCA 32lumin87Оценок пока нет

- Twinsectra LTD v. YardleyДокумент39 страницTwinsectra LTD v. Yardleylumin87Оценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

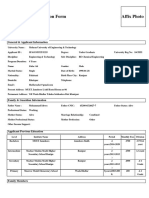

- Scholarship Application Form Affix PhotoДокумент5 страницScholarship Application Form Affix PhotoShakeel AhmedОценок пока нет

- Revised Discount Rate Original Discount RateДокумент13 страницRevised Discount Rate Original Discount RateRITZ BROWNОценок пока нет

- Rental Agreement Format ChennaiДокумент4 страницыRental Agreement Format Chennaisundarji sundararajuluОценок пока нет

- Chapter 9Документ14 страницChapter 9Mritunjay KumarОценок пока нет

- Tenancy Agreement TemplateДокумент17 страницTenancy Agreement Templatelost78Оценок пока нет

- Kemppi TuomasДокумент182 страницыKemppi TuomassapimachoОценок пока нет

- Property Management Training ManualДокумент48 страницProperty Management Training Manualjr_raffy589567% (3)

- de Guia vs. CAДокумент2 страницыde Guia vs. CALeo TumaganОценок пока нет

- Cases For Spec Pro ClassДокумент46 страницCases For Spec Pro ClassBruce WayneОценок пока нет

- Major Quiz #2Документ10 страницMajor Quiz #2jsus22Оценок пока нет

- Nigeria WHT Need To KnowДокумент6 страницNigeria WHT Need To KnowphazОценок пока нет

- Administración de Ventas - Chapter 3Документ61 страницаAdministración de Ventas - Chapter 3albgatmtyОценок пока нет

- Income Tax WHT Rates Card 2016-17Документ8 страницIncome Tax WHT Rates Card 2016-17Sami SattiОценок пока нет

- Architecture Project Topics and MaterialsДокумент13 страницArchitecture Project Topics and MaterialsProject ChampionzОценок пока нет

- Truck Rental Business PlanДокумент1 страницаTruck Rental Business PlansolomonОценок пока нет

- Basic Principle of ValuvationДокумент20 страницBasic Principle of ValuvationEr Chandra BoseОценок пока нет

- Sps. Manila vs. Sps. ManzoДокумент6 страницSps. Manila vs. Sps. ManzoaudreyracelaОценок пока нет

- Direct Financing Lease Bafacr4x OnlineglimpsenujpiaДокумент4 страницыDirect Financing Lease Bafacr4x OnlineglimpsenujpiaAga Mathew MayugaОценок пока нет

- Contractora Estimate Cost - Propelat RapДокумент192 страницыContractora Estimate Cost - Propelat RapMr. RudyОценок пока нет

- XxdaadДокумент12 страницXxdaadattycpajfccОценок пока нет

- Assignment 1 WorksheetДокумент1 страницаAssignment 1 Worksheetgolemwitch01Оценок пока нет

- 2 Apply ApplicationДокумент7 страниц2 Apply Applicationfernando miranda gonzalezОценок пока нет

- Tenancy Agreement RLA ASTДокумент4 страницыTenancy Agreement RLA ASTDavid Dsd Nguyen100% (1)

- Deposit of RentДокумент33 страницыDeposit of RentArunaMLОценок пока нет

- Apartment List 03-23-2012Документ11 страницApartment List 03-23-2012Marcus AttheCenter FlenaughОценок пока нет

- 0321 County LineДокумент8 страниц0321 County LineMineral Wells Index/Weatherford DemocratОценок пока нет

- Taxes On Commercial LeaseДокумент8 страницTaxes On Commercial Leasebelbel08Оценок пока нет

- 24 Millare V HernandoДокумент1 страница24 Millare V HernandoluigimanzanaresОценок пока нет

- 2021 Resit PG Dip Land Law Take Home ExamДокумент8 страниц2021 Resit PG Dip Land Law Take Home ExamNicolae FocsaОценок пока нет

- Millare V.hernandoДокумент8 страницMillare V.hernandoWinter WoodsОценок пока нет