Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

B. Montesquieu Research

Загружено:

Joanne S.Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

B. Montesquieu Research

Загружено:

Joanne S.Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

BARON DE MONTESQUIEU

Charles Louis de Secondat was born in Bordeaux, France, in 1689 to a wealthy family.

Despite his family's wealth, de Decondat was placed in the care of a poor family during his

childhood. He later went to college and studied science and history, eventually becoming a

lawyer in the local government. De Secondat's father died in 1713 and he was placed under the

care of his uncle, Baron de Montesquieu. The Baron died in 1716 and left de Secondat his

fortune, his office as president of the Bordeaux Parliament, and his title of Baron de

Montesquieu. Later he was a member of the Bordeaux and French Academies of Science and

studied the laws and customs and governments of the countries of Europe. He gained fame in

1721 with his Persian Letters, which criticized the lifestyle and liberties of the wealthy French as

well as the church. However, Montesquieu's book On the Spirit of Laws, published in 1748, was

his most famous work. It outlined his ideas on how government would best work.

Montesquieu believed that all things were made up of rules or laws that never changed. He

set out to study these laws scientifically with the hope that knowledge of the laws of government

would reduce the problems of society and improve human life. According to Montesquieu, there

were three types of government: a monarchy (ruled by a king or queen), a republic (ruled by an

elected leader), and a despotism (ruled by a dictator). Montesquieu believed that a government

that was elected by the people was the best form of government. He did, however, believe that

the success of a democracy - a government in which the people have the power - depended

upon maintaining the right balance of power.

Montesquieu argued that the best government would be one in which power was balanced

among three groups of officials. He thought England - which divided power between the king

(who enforced laws), Parliament (which made laws), and the judges of the English courts (who

interpreted laws) - was a good model of this. Montesquieu called the idea of dividing

government power into three branches the "separation of powers." He thought it most important

to create separate branches of government with equal but different powers. That way, the

government would avoid placing too much power with one individual or group of individuals. He

wrote, "When the [law making] and [law enforcement] powers are united in the same person...

there can be no liberty." According to Montesquieu, each branch of government could limit the

power of the other two branches. Therefore, no branch of the government could threaten the

freedom of the people. His ideas about separation of powers became the basis for the United

States Constitution.

Despite Montesquieu's belief in the principles of a democracy, he did not feel that all people

were equal. Montesquieu approved of slavery. He also thought that women were weaker than

men and that they had to obey the commands of their husband. However, he also felt that

women did have the ability to govern. "It is against reason and against nature for women to be

mistresses in the house... but not for them to govern an empire. In the first case, their weak

state does not permit them to be preeminent; in the second, their very weakness gives them

more gentleness and moderation, which, rather than the harsh and ferocious virtues, can make

for a good environment." In this way, Montesquieu argued that women were too weak to be in

control at home, but that there calmness and gentleness would be helpful qualities in making

decisions in government.

Source: http://www.rjgeib.com/thoughts/montesquieu/montesquieu-bio.html

The French satirist (writer using sarcasm to communicate his message) and political and social

philosopher Montesquieu was the first of the great French scholars associated with the

Enlightenment (a philosophical movement in the eighteenth century that rejected traditional

social and religious ideas by placing reason as the most important ideal).

Early life

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu was born on January 18, 1689, at the castle

of La Brde near Bordeaux. His father, Jacques de Secondat, was a soldier

Montesquieu.

Courtesy of the

Library of Congress

with a long noble ancestry, and his mother, Marie Franoise de Pesnel, who died when Charles

Louis was seven, was an heiress (a woman with a large monetary inheritance) who eventually

brought the barony (title of baron) of La Brde to the Secondat family. As was customary the

young Montesquieu spent the early years of his life among the peasants (poor working class) in

the village of La Brde. The influence of this period remained with Charles Louis, showing itself

in his deep attachment to the soil. Montesquieu was also born into a climate of discontent in

France. King Louis XIV's (16381715) long reign was uncomfortable for the citizens of France.

His unsuccessful wars and attempts to dictate religion and culture had a bad effect on France.

Knowledge of this situation helps to explain some of Montesquieu's curiosity and his interest in

societal rules and laws.

In 1700 Montesquieu was sent to the Oratorian Collge de Juilly, at Meaux, where he received

a modern education. Returning to Bordeaux in 1705 to study law, he was admitted to practice

before the Bordeaux Parlement (parliament) in 1708. The next five years were spent in Paris,

France, continuing his studies. During this period he developed an intense dislike for the style of

life in the capital, which he later expressed in his Persian Letters.

In 1715 Montesquieu married Jeanne de Lartigue, a Protestant (a member of the church that

had left the rule of Roman Catholicism), who brought him a large dowry (sum of money given in

marriage). He was also elected to the Academy of Bordeaux. The following year, on the death

of his uncle Jean Baptiste, he inherited the barony of Montesquieu and the presidency of the

Bordeaux Parlement.

Scholarly and literary career

Montesquieu had no great enthusiasm for law as a profession. He was much more interested in

the spirit that lay behind law. It is from this interest that his greatest work, The Spirit of the Laws,

developed. To free himself in order to continue his scholarly interests, he sold his office as

president of the Bordeaux Parlement in 1721. With his newly freed time he wrote the Persian

Letters.

The Persian Letters was a fierce and bitingly critical view of European civilization and manners.

The work takes the form of letters that three Persians (people from what is now Iran) traveling in

Europe send to families and friends at home. Their letters are notes on what they see in the

West. Montesquieu gave his travelers the foreign, commonsense understanding necessary to

effectively criticize European (French) customs and institutions. Yet he also gave his Persians

the weaknesses necessary to make his readers recognize in them their own weaknesses. All

sides of European life were criticized. The message is that society lasts only on the basis of

virtue and justice, which is rooted in the need of human cooperation and acceptance.

Although the Letters was published without his name, it was quickly recognized as the work of

Montesquieu and won him the approval of the public and the displeasure of the governor,

Cardinal Andr Fleury, who held up Montesquieu's introduction into the French Academy until

1728.

The Spirit of the Laws

Montesquieu brought his search for the general laws active in society and history to its

completion in his greatest work. Published in 1748, The Spirit of the Laws was an investigation

of the environmental and social relationships that lie behind the laws of civilized society.

Combining the traditions of customary law with those of the modern theories of natural law,

Montesquieu redefined law as "the necessary relationships that derive [come] from the nature of

things." Laws "must be adapted to each peoples."

The Spirit of the Laws helped to lay the basis of the eighteenth-century movement for

constitutionalism (government run by established law), which ended in the Revolution of 1789

(178993; rise and revolt of the middle class against the failures of King Louis XVI and his

royals, many of whom were killed by the guillotine, or chopping block). In this sense

Montesquieu's most basic belief may be viewed as an attempt to state the necessity of law

review. The Spirit of the Laws was immediately celebrated as one of the great works of French

literature.

Following the completion of his work, Montesquieu, who was going blind, went into

semiretirement at La Brde. He died on February 10, 1755, during a trip to Paris.

Read more: Montesquieu Biography - life, family, name, death, history, mother, young,

information, born, marriage, time http://www.notablebiographies.com/Mo-

Ni/Montesquieu.html#ixzz1f16nkXS1

Вам также может понравиться

- Montesquieu: 1 BiographyДокумент7 страницMontesquieu: 1 BiographyNeverGiveUp ForTheTrueОценок пока нет

- Ismail Pol SciДокумент20 страницIsmail Pol Scisinat fifaОценок пока нет

- Montesque I UДокумент2 страницыMontesque I UDavid ChavezОценок пока нет

- Paul Carrese On MontesquieuДокумент18 страницPaul Carrese On Montesquieureltih18Оценок пока нет

- Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, and Rousseau On Government: Handout AДокумент5 страницHobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, and Rousseau On Government: Handout Aabhisek kaushalОценок пока нет

- HobbesLockeMontesquieuRousseau PDFДокумент7 страницHobbesLockeMontesquieuRousseau PDFKaren NavarroОценок пока нет

- Baron de MontesquieuДокумент15 страницBaron de Montesquieuapi-252717204100% (1)

- The Spirit of Laws: A Compendium of the First English EditionОт EverandThe Spirit of Laws: A Compendium of the First English EditionРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (81)

- HobbeslockemontesquieuДокумент3 страницыHobbeslockemontesquieuapi-264004260Оценок пока нет

- MontesquieuДокумент2 страницыMontesquieuEffy StonemОценок пока нет

- Baron de MontesquieuДокумент4 страницыBaron de MontesquieuAndrew Gonzalez100% (1)

- The Social Contract (Translated by G. D. H. Cole with an Introduction by Edward L. Walter)От EverandThe Social Contract (Translated by G. D. H. Cole with an Introduction by Edward L. Walter)Оценок пока нет

- Two Catholic Conservatives-The Ideas of Josheph de Maistre and Juan Donoso CortesДокумент11 страницTwo Catholic Conservatives-The Ideas of Josheph de Maistre and Juan Donoso Cortesmens_reaОценок пока нет

- Montesquieu and the Despotic Ideas of Europe: An Interpretation of "The Spirit of the Laws"От EverandMontesquieu and the Despotic Ideas of Europe: An Interpretation of "The Spirit of the Laws"Оценок пока нет

- Enlightenment PaperДокумент5 страницEnlightenment PaperMaya HarrisОценок пока нет

- The Enlightenment in EuropeДокумент9 страницThe Enlightenment in EuropeSaranyaОценок пока нет

- Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 58, Number 360, October 1845От EverandBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 58, Number 360, October 1845Оценок пока нет

- Legal Methods ProjeДокумент7 страницLegal Methods ProjeInjila ZaidiОценок пока нет

- Age of Enlightenment: A History From Beginning to EndОт EverandAge of Enlightenment: A History From Beginning to EndРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (10)

- Discourse on Inequality & The Social Contract: Including Discourse on the Arts and Sciences & A Discourse on Political EconomyОт EverandDiscourse on Inequality & The Social Contract: Including Discourse on the Arts and Sciences & A Discourse on Political EconomyОценок пока нет

- Montesquieu HandoutДокумент2 страницыMontesquieu HandoutA Square ChickenОценок пока нет

- The Major Political Writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Two Discourses and the Social ContractОт EverandThe Major Political Writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Two Discourses and the Social ContractРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Mississippi State University The Mississippi QuarterlyДокумент13 страницMississippi State University The Mississippi QuarterlyHarshita DixitОценок пока нет

- CH 22 Sec 2 - The Enlightenment in EuropeДокумент6 страницCH 22 Sec 2 - The Enlightenment in EuropeMrEHsiehОценок пока нет

- University of Pennsylvania PressДокумент11 страницUniversity of Pennsylvania PressGabriela Rodríguez RialОценок пока нет

- The Political Philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Impossibilty of ReasonОт EverandThe Political Philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Impossibilty of ReasonОценок пока нет

- Jean BodinДокумент4 страницыJean BodinyesiamareuОценок пока нет

- THE ENLIGHTENMENT UwuДокумент15 страницTHE ENLIGHTENMENT UwuCamilaОценок пока нет

- The Phenomenon of Crowd Psychology (10 Books in One Volume): Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Instincts of the Herd, The Social ContractОт EverandThe Phenomenon of Crowd Psychology (10 Books in One Volume): Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Instincts of the Herd, The Social ContractОценок пока нет

- Montesquieu and The StateДокумент36 страницMontesquieu and The StateKvkОценок пока нет

- MontesquieuДокумент26 страницMontesquieuMohiuddin QureshiОценок пока нет

- Imagining World Order: Literature and International Law in Early Modern Europe, 1500–1800От EverandImagining World Order: Literature and International Law in Early Modern Europe, 1500–1800Оценок пока нет

- Govt 1001 Topic 6 Montesquieu and Separation of PowersДокумент33 страницыGovt 1001 Topic 6 Montesquieu and Separation of PowersCeline SinghОценок пока нет

- Political TheoryДокумент15 страницPolitical TheoryCindy RheyaОценок пока нет

- The Social Contract: Including Discourse on Inequality, On the Arts and Sciences, On Political EconomyОт EverandThe Social Contract: Including Discourse on Inequality, On the Arts and Sciences, On Political EconomyОценок пока нет

- Jean Jacques Rousseau (Notes)Документ2 страницыJean Jacques Rousseau (Notes)Allan Martin A. Dosdos IIОценок пока нет

- CROWD PSYCHOLOGY: Understanding the Phenomenon and Its Causes (10 Books in One Volume): Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Instincts of the Herd, The Social Contract, A Moving-Picture of Democracy, Psychology of Revolution, The Analysis of the Ego...От EverandCROWD PSYCHOLOGY: Understanding the Phenomenon and Its Causes (10 Books in One Volume): Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Instincts of the Herd, The Social Contract, A Moving-Picture of Democracy, Psychology of Revolution, The Analysis of the Ego...Оценок пока нет

- Montesquieu: Letters. and Their Decline (1734), Considered by Some Scholars, Among His Three Best KnownДокумент2 страницыMontesquieu: Letters. and Their Decline (1734), Considered by Some Scholars, Among His Three Best Knownᘉᓋᘻᗗᘙ ᘉᓋᙏᓲ ᖽᐸᗁᕠᘘОценок пока нет

- Sketches of the French Revolution: A Short History of the French Revolution for SocialistsОт EverandSketches of the French Revolution: A Short History of the French Revolution for SocialistsОценок пока нет

- The Man Who Understood Democracy: The Life of Alexis de TocquevilleОт EverandThe Man Who Understood Democracy: The Life of Alexis de TocquevilleРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (3)

- MontesquieuДокумент38 страницMontesquieuMohiuddin QureshiОценок пока нет

- The Social Contract by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideОт EverandThe Social Contract by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideОценок пока нет

- Jean Jacques Rousseau: Summarized Classics: SUMMARIZED CLASSICSОт EverandJean Jacques Rousseau: Summarized Classics: SUMMARIZED CLASSICSОценок пока нет

- Methodology: Indiuidzldlism, Orality: Monteqzlieds Holism, and MДокумент15 страницMethodology: Indiuidzldlism, Orality: Monteqzlieds Holism, and MFolKalFОценок пока нет

- French PhilosophersДокумент5 страницFrench Philosopherspotter_harry816Оценок пока нет

- Philosophical Issues and Ethical Standards in Public Service Management (GS85 - PHILO 202)Документ17 страницPhilosophical Issues and Ethical Standards in Public Service Management (GS85 - PHILO 202)Fam Catalan Vargas-ChariasОценок пока нет

- Prehistory of PampangaДокумент1 страницаPrehistory of PampangaJoanne S.Оценок пока нет

- Ifugao PoemДокумент1 страницаIfugao PoemJoanne S.100% (3)

- Contributions of The Egyptian CivilizationДокумент2 страницыContributions of The Egyptian CivilizationJoanne S.0% (1)

- Lithium!Документ1 страницаLithium!Joanne S.Оценок пока нет

- Essay of City LifeДокумент4 страницыEssay of City Lifeezmsdedp100% (2)

- 2º Conj. EM2 - 2021 - Prova 01Документ50 страниц2º Conj. EM2 - 2021 - Prova 01Taís ReisОценок пока нет

- How Long Does It Take To Engineer The Collapse of A Government? - NSA Shadow Govt InfoДокумент46 страницHow Long Does It Take To Engineer The Collapse of A Government? - NSA Shadow Govt InfoDGB DGBОценок пока нет

- A20 - T-N - U1 - l4 - Ipa UmbrellasДокумент2 страницыA20 - T-N - U1 - l4 - Ipa UmbrellasHoàng Phương LinhОценок пока нет

- 10 - Chapter 4 The Good Person of Schwan PDFДокумент33 страницы10 - Chapter 4 The Good Person of Schwan PDFpurnimaОценок пока нет

- DP ChartДокумент45 страницDP ChartKumar SaikhomОценок пока нет

- Colin Crouch, The March Towards Post-Democracy - Ten Years On, The Political Quarterly PDFДокумент5 страницColin Crouch, The March Towards Post-Democracy - Ten Years On, The Political Quarterly PDFSolMonteroОценок пока нет

- Kanshi RamДокумент5 страницKanshi Ramprince kanjirathingalОценок пока нет

- (Greece) Battle of Kalamata Waterfront PDFДокумент1 страница(Greece) Battle of Kalamata Waterfront PDFRaúlОценок пока нет

- Activity Worksheet No. 5 - Lights, Camera, Action!Документ2 страницыActivity Worksheet No. 5 - Lights, Camera, Action!Aira MaeОценок пока нет

- The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law Eckert, Julia - Urban Governance and Emergent Forms of Legal Pluralism in MumbaiДокумент33 страницыThe Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law Eckert, Julia - Urban Governance and Emergent Forms of Legal Pluralism in MumbaiKshitij BhardwajОценок пока нет

- As CBSE X SS CH 2 Federalism Practise Sheet 2Документ2 страницыAs CBSE X SS CH 2 Federalism Practise Sheet 2Hemant PadalkarОценок пока нет

- Đề 01Документ5 страницĐề 01teachingielts2023Оценок пока нет

- Historic Decision On Godavari-Cauvery Linkage Will Be Imprinted in TN History - PalaniswamiДокумент1 страницаHistoric Decision On Godavari-Cauvery Linkage Will Be Imprinted in TN History - Palaniswamichennai SupportОценок пока нет

- Rossi Pool San Francisco Hours and RatesДокумент1 страницаRossi Pool San Francisco Hours and Ratesiriesergio100% (6)

- Mayor Marisa Red Inaugural Address To The Sangguniang Bayan - LandscapeДокумент44 страницыMayor Marisa Red Inaugural Address To The Sangguniang Bayan - LandscapeRene Raymond NotoApeco RanesesОценок пока нет

- Andhra PradeshДокумент4 страницыAndhra PradeshBharath KumarОценок пока нет

- Resume Dimas Haryo YudhantoДокумент2 страницыResume Dimas Haryo YudhantoIla MaОценок пока нет

- Reported Speech ChuletaДокумент2 страницыReported Speech ChuletaRut Suarez garciaОценок пока нет

- COFACE BAROMETRE T32022 Carte VGBДокумент1 страницаCOFACE BAROMETRE T32022 Carte VGBMartin Stephan Arias MedinaОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Public Administration MCQs For CSS - PMS - PCS (SET-II)Документ5 страницIntroduction To Public Administration MCQs For CSS - PMS - PCS (SET-II)MAQSOOD AHMADОценок пока нет

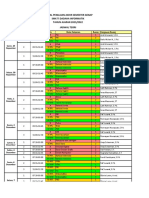

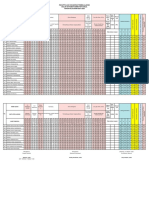

- Jadwal Penilaian Akhir Semester Genap SMK Ti Dadaha Informatik TAHUN AJARAN 2021/2022 Jadwal TeoriДокумент7 страницJadwal Penilaian Akhir Semester Genap SMK Ti Dadaha Informatik TAHUN AJARAN 2021/2022 Jadwal Teoriandi batikОценок пока нет

- Midterm Exam (Philippine Politics and Governance) : Table of SpecificationДокумент3 страницыMidterm Exam (Philippine Politics and Governance) : Table of SpecificationRuby Ann Almazan MatutinoОценок пока нет

- Cassie Docksey TranscriptДокумент48 страницCassie Docksey TranscriptDaily KosОценок пока нет

- HedonismДокумент3 страницыHedonismJanna FavilaОценок пока нет

- Resolution Approving The CbydpДокумент2 страницыResolution Approving The CbydpJay Ann Candelaria OlivaОценок пока нет

- Absensi Xi TBSM OktoberДокумент2 страницыAbsensi Xi TBSM OktoberTaufiq ArrahmanОценок пока нет

- The EnemyДокумент23 страницыThe EnemyMinu JhaОценок пока нет

- 1 PBДокумент14 страниц1 PBAliyu AbdulqadirОценок пока нет

- 19 GS KPSC 07122014 PDFДокумент40 страниц19 GS KPSC 07122014 PDFrpsirОценок пока нет