Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Conempt Third Party

Загружено:

Sudeep Sharma0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

868 просмотров65 страниц1. The plaintiff filed a suit seeking an injunction to prevent the defendant and her agents from conducting construction activities on a property. The subordinate court judge granted a temporary injunction.

2. The plaintiff then filed a contempt petition in the high court against both the defendant and her husband. The plaintiff alleged that both violated the injunction by continuing construction, with the husband aiding and abetting the violation.

3. The high court held that the subordinate court judge who granted the injunction had jurisdiction over matters of disobedience or breach of that order. It was more appropriate for that lower court, familiar with the case, to investigate the alleged violation. The court dismissed the petition.

Исходное описание:

Conempt Third Party

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документ1. The plaintiff filed a suit seeking an injunction to prevent the defendant and her agents from conducting construction activities on a property. The subordinate court judge granted a temporary injunction.

2. The plaintiff then filed a contempt petition in the high court against both the defendant and her husband. The plaintiff alleged that both violated the injunction by continuing construction, with the husband aiding and abetting the violation.

3. The high court held that the subordinate court judge who granted the injunction had jurisdiction over matters of disobedience or breach of that order. It was more appropriate for that lower court, familiar with the case, to investigate the alleged violation. The court dismissed the petition.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

868 просмотров65 страницConempt Third Party

Загружено:

Sudeep Sharma1. The plaintiff filed a suit seeking an injunction to prevent the defendant and her agents from conducting construction activities on a property. The subordinate court judge granted a temporary injunction.

2. The plaintiff then filed a contempt petition in the high court against both the defendant and her husband. The plaintiff alleged that both violated the injunction by continuing construction, with the husband aiding and abetting the violation.

3. The high court held that the subordinate court judge who granted the injunction had jurisdiction over matters of disobedience or breach of that order. It was more appropriate for that lower court, familiar with the case, to investigate the alleged violation. The court dismissed the petition.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 65

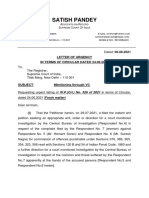

MANU/DE/0426/1982

Equivalent Citation: 1983CriLJ495, 22(1982)DLT33, 1982RLR553

IN THE HIGH COURT OF DELHI

Criminal Contempt Appeal No. 2 of 1982

Decided On: 25.05.1982

Appellants: Bimal Chandra Sen

Vs.

Respondent: Kamla Mathur and Anr.

Hon'ble Judges/Coram:

A.B. Rohtagi and Leila Seth, JJ.

Subject: Criminal

Subject: Contempt of Court

Catch Words

Mentioned IN

Acts/Rules/Orders:

Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) - Order 39 Rule 2

Case Note:

Civil Procedure Code - Order 39, Rule 2 vis-a-vis contempt of Court Act, Sections 10 & 12--

Injunction order issued by court--disobedience--jurisdiction to punish contempt vests in

court issuing it--person not party or abetter or sider cannot be proceeded for contempt--

abettor or aider cannot be held liable for criminal contempt either--criminal and civil

contempt--difference.

A suit of permanent injunction was filed in the court of subordinate judge, by the plaintiff seeking

injunction, restraining the defendant, her servants, and agents from carrying on any construction

activities in the property. A temporary injunction was granted. plaintiff moved an application in the

High Court under Sections 10 and 12 of the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971 read with Article 215 of the

Constitution. The respondent to the application are the defendant in the suit and her husband. The

plaintiff complains that both wife and husband have flouted the order of injunction by going on with

the construction. The allegations are that husband is aider and abettor of contempt, because he is

supervising the fresh illegal construction activities. The question involved in the petition is, whether a

petition under Sections 10 and 12 of the Contempt of Courts Act and Article 215 of the constitution will

lie in the High Court in respect of an injunction order issued by the subordinate Judge. Dismissing the

petition.

Held:

1. For the disobedience of the injunction order or breach of any of its terms the court of subordinate

judge granting the injunction has jurisdiction to punish "a person guilty of such disobedience or

breach". The High Court has the power under Section 10 of the Act but the exercise of that power is

discretionary.

2. Under Order 29, Rules 2-A, C.P.C. any detailed enquiry must be left to the court which has passed

the order and which is fully acquainted with the subject-matter of its own order of temporary

prohibitory injunction. It is more desirable that the court which made the order of injunction should go

in to the facts and ascertain the truth of the alleged disobedience and extent to which is willful.

3. A person not a party to the suit cannot be proceeded against for contempt for aiding and abetting

the breach.

4. The essence of criminal contempt consists in the doing of something calculated or designed to obtain

a result of legal proceedings different from that which would follow in the ordinary course. Criminal

contempt is external to the administration of justice and truly subversive of it. It is an obstruction and

outrage against the public administration of justice. It is essentially criminal in character. It is foulest

contamination which can infect the judicial system. It is a great evil.

5. 'Criminal contempt' may be defined as contumelious or obstructive behavior directed against the

court and one example of this is contempt in the fact of the court. It is an obstruction of justice, a

sinning against the majesty of law and time honoured jurisdiction over such offence is undisputed.

Criminal contempt means despising of the authority of court. Sometimes by using words importing

scorn, reproach or diminution of the court, its process, orders, officers, or ministers, upon executing

or serving such process or orders.

6. Civil contempt is basically a wrong to the person who is entitled to the benefit of the

court order and is essentially remedial and coercive. Civil contempt of court exists to provide the

ultimate sanction against him who refused to comply with the order of a properly constituted court.

Once the offender complies with the court's order he has a right to be released, whereas there is no

such right in respect of criminal contempt.

7. Criminal contempt are essentially offence of a public nature and consist of publications or acts which

interfere with the due court of justice as, for example, by tending to jeopardise the fair hearing of a

trial or by tending do deter or frighten witnesses or by interrupting court proceedings or by tending to

impair public confidence in the authority or integrity of the administration of justice. Civil contempt, on

the other hand, are committed by disobeying court judgments or orders either to do or to abstain

from doing particular acts or by breaking the terms of an undertaking given to the court, on the faith

of which a particular course of action or inaction in sanctioned, or by disobeying other court orders.

Civil contempt are, Therefore, 'offence' essentially of a private nature since they deprive a party of the

benefit for which the order was made. The essence of the court's jurisdiction in respect of criminal

contempt is penal, the aim being to protect the public interest in ensuring that the administration of

justice is duly protected. On the other hand, the court's jurisdiction in respect of civil contempt is

primarily remedial, the basic object being to coerce the offender into obeying the court's judgment

or order.

JUDGMENT

Avadh Behari Rohatgi, J.

(1) The Facts : The plaintiff, Dr. Bimal Chandra Sen, owns property No. 4405 in Darya Ganj, Delhi. He

says that he gave a portion of his property on lease and license to one Mrs. Kamla Mathur wife of Shri

Rama Shankar Mathur. The plaintiff alleges that Mrs. Mathur was making illegal construction in the

property. On 6-4-1981 he brought a suit in the court of the subordinate judge, Mr. S. N. Gupta, for

permanent injunction restraining Mrs. Mathur, her servants and agents, from carrying on any

construction activities in the property. In. the suit the plaintiff made an application for temporary

injunction under Order 39 rules 1 and 2 of the Code of Civil Procedure. The subordinate judge granted

a temporary injunction against the defendant, her agents and servants.. on 6-4-1981. On 6-6-81 he

modified the injunction order. From this order they, the plaintiff and the defendants, appealed to the

court of the senior sub judge. Those appeals were dismissed.

(2) Now the plaintiff has made an application to this court under Sections 10 and 12 of the Contempt

of Courts Act 1971 (the Act) read with Article 215 of the Constitution. The respondents to this

application are (1) Mrs. Kamla Mathur and (2) Rama Shankar Mathur. The plaintiff complains that both

wife and husband have flouted the order of injunction by going on with the construction. He says that

they should be committed for contempt for acting in defiance of the injunction. The wife is admittedly a

party to the suit The husband is said to be an aider and abettor of contempt because he is 'supervising

the fresh illegal construction activities."

(3) Notice of this application was issued to the wife and the husband. They appeared in court and are

represented by counsel. The matter first came before Charanjit Talwar J. He was of the view that the

husband was not a party to the suit and tile averments made against him prima facie constituted on

offence of criminal contempt of court. Since cognizance of criminal contempt can be taken only by a

division bench he, by order dated September 1, 1981, directed that the matter be placed before a

division bench. This is how the mater has come before us.

(4) At the very outset the question arises whether such a petition under Sections 10 and 12 of the Act

is maintainable in this court on the averments made by the plaintiff. The suit was brought by the

plaintiff against the wife of Mr. Mathur. She is the sole defendant in the suit. Against her the

injunction order was issued hy the .subordinate judge under Order 39 rules I and 2, Civil Procedure

Code. enjoining her not to make construction. This was later on modified. No" the plaintiff complains of

violation of the injunction order and says that the wife as the principal offender and the husband as an

'aider and abettor' be punished for contempt of court under Sections 10 and 12 of the Act and

Article 215 of the Constitution. Will such a petition lie in this Court in respect of an

injunction order issued by the subordinate Judge ?

(5) The principal argument of plaintiff's counsel is that Order 39 does not provide effective relief to

the plaintiff as those provisions have their own limitations and a more efficacious remedy for doing

complete justice to a litigant is provided by Sections 10 and 12(3) of the Act. Basing himself entirely

on the Act he says that the wife is guilty of civil contempt and the husband of criminal contempt as an

"aider and abettor'. I will examine this argument in relation to wife and husband separately. Case

against wife :

(6) In so far as the wife is concerned the legal position admits of no difficulty. She is the defendant in

the suit. The court issued a temporary injunction against her. The plaintiff alleges that she has

disobeyed the injunction order. For disobedience of the injunction order rules 2A of Order 39 of the

Code provides the remedy. Rule 2A says : "Consequence of disobedience or breach of injunction. (1) In

the case of disobedience of any injunction granted or other order made under rule 1 or rule 2 or

breach of any of the terms on which the injunction was granted or the order made, the Court granting

the injunction or making the order, or any court to which the suit or proceeding is transferred,

may order the property of the person guilty of such disobedience or breach to be attached, and may

also order such person to be detained in the civil prison for a term not exceeding three months, unless

in the meantime the court directs him release. (2) No attachment made under this rule shall remain in

force for more than one year. at the end of which time, if the disobedience or breach continues, the

property attached may be sold and out of the proceedings, the court may award such compensation as

it thinks fit to the injured party and shall pay the balance, if any, to the party entitled thereto,

(7) Rule 2A was inserted by the Amendment Act of 1976. Sub-rules (3) and (4) have been omitted and

Rule 2A enacted in their place. It provides for cases of disobedience or breach of injunction. The

transferee court can also exercise this power.

(8) The breach by a party of an order made against him or her in the course of a civil case is a

perfectly familiar thing. Cases of breach of injunction are tried every day. The proper court to try that

is undoubtedly the court which tries the civil proceeding and makes the order. I have never yet heard

that cases of disobedience of injunction were anything but subject to trial by the civil judges trying the

suit. And in the course of the trial it is open to the person accused of breach to establish upon the facts

that what had been done is not a breach in fact, but was a legitimate and defensible action. In Taylor

v. Taylor Lr 1 Ch. D. at: p. 431(1) Sir George Jessel said :

" Whereon the other hand, a statutory power is conferred for the first time upon a court and

the mode of exercising it is pointed out, it means that no other mode of exercising it is to be

adopted."

(9) That the court which passes the injunction order shall have power to commit for contempt in case

of breach is the unquestioned rule since 1882. unquestioned by anything that I can recognise as an

authority binding on me. Section 493 of the Code of Civil Procedure (Act XIV) of 1882 enacted this

rule. The present Code (Act V) of 1908 embodies the same rule. During the long history of the. Codes

in India for one hundred years there is not a single instance in Out law books where the High Courts

tried a party for the disobedience of injunction issued by a subordinate court.

(10) A disobedience of an order of injunction is a contempt of court. Sub-rule (1) confers on courts

the power to punish such contempt and, further, prescribes the punishment to be awarded therefore.

(See Amritlal v. P. Srinivas Rao, MANU/AP/0100/1967 : AIR1967AP48 and Ram Saran v. Chatar

Singh (1901) 23 All. 465. The sub-rule provides for the punishment not only of disobedience of the

temporary injunction but also of breach of any of the terms subject to which the injunction may have

been granted. (Narsappa v. Chinnareppa, Air 1947 Mad. 98. While the High Courts as courts of record

have inherent jurisdiction to commit for contempt, other courts have no such power apart from the

provisions of rule 2A. Janak Nandini v. Kedar Narain Singh MANU/UP/0039/1940 : AIR1941All140

and Rochappa v. Sachi Dcvi (1902) 26 Mad 494. So in the case of wife it is plain that for the

disobedience of the inanition order or breach of any of its terms the court of subordinate judge

granting the injunction has jurisdiction to punish "a person guilty of such disobedience or breach". The

High Court has power under Section 10 of the Act but the exercise of that power is discretionary. (See

Ram Rup Pandey v. R. K. Bhargava. MANU/UP/0051/1971 : AIR1971All231 .

(11) In Ramalingan v. Mahalinga Nadar MANU/TN/0114/1966 : AIR1966Mad21 the court held

that Order 39 rule 2(3), Civil Procedure Code . is a far more adequate and satisfactory remedy in such

cases. Any detailed inquiry must be left to the court which has passed the order and which is fully

acquainted with the subject-matter of its own order of temporary prohibitory injunction. "It is clearly

more desirable that the court which made the order of injunction should go into the facts, and

ascertain the truth of the alleged disobedience, and the extent to which it is willful". (page 22). Case

against the husband :

(12) The question remains regarding the liability of the husband. Can he be punished for contempt of

court under contempt of court, counsel for the plaintiff argued that under Sections 10 and 12 of the Act

and Article 215 of the Constitution this High Court has ample power to punish a person even though he

is not a defendant to the suit if the Court is satisfied that he is instigating or assisting in the

disobedience of the injunction order or breach of its terms. I may straightway say that the body of the

case law in India is against this contention. I shall refer to two recent authorities, In Indu v. Ram

Bahadur Choudhary MANU/UP/0202/1981 : AIR1981All309 Sinha J. said : "In my opinion, a person

who has got an effective alternative remedy of the nature specified under Order Xxxix, Rule 2-A or

under Order XXI. Rule 32. Civil Procedure Code. should not be permitted to skip over that remedy and

take resort to initiate proceedings under the Contempt of Courts Act. The least that can be said is that

it would not be a proper exercise of discretion on the part of this Court to exercise its jurisdiction under

the Contempt of Courts Act when such an effective and alternative, remedy is available to any person.

I am fortified in taking this view by the observations made in Ram Rup Pandey v. R. K. Bhargava

MANU/UP/0051/1971 : AIR1971All231 and Calcutta Medical Stores v. Stadmed Private Ltd. (1977)

81 Cal. Wn 209.

(13) In Rudriah v. State of Karnataka 1981 (1) Karnataka Law Journal 33(11) (DB) the Court said that

when special procedure and special provision is contained in the Code of Civil Procedure itself

under Order Xxxix rule 2-A for taking action for the disobedience of an order of injunction, the

general law of contempt of court cannot be invoked. If such a course is encouraged holding that it

amounts to contempt of court, when an order of subordinate court is not obeyed, it is sure to throw

open a floodgate of litigation under contempt jurisdiction. "Every decree holder can rush to this court

staling that the decree passed by a subordinate court is not obeyed. This is not the purpose of the

Contempt of Courts Act." (p. 34).

(14) These two decisions were cases where the plaintiff alleged contempt of court against a party to

the suit and required the High Court to proceed against him under the Act. The Courts refused to take

action under the Act. But what about a person who is not a party to the suit and who is charged with

aiding and abetting the breach of the injunction order. Does Rule 2A also include an aider and abettor'

who is not a party to the suit ? This is the question to be decided. In Mawazzam Ali v. Shubhas

Chandra MANU/WB/0212/1927 : AIR1927Cal598 Rankin Cj and Majumdar J. expressed the opinion

that order 39 rule 2(3) C. P. C. (the old provision now replaced by Rule 2-A), is not intended to give

the court power to visit for contempt of court people against whom no order is made and Therefore

abettors of contempt of court cannot be punished. Rankin Cj said :

" THERE can be no doubt that according to the English cases there does exist in the High Court

in England a power to commit for contempt persons who abet disobedience of an injunction.

But for the purposes of the mofussil courts this jurisdiction has to be taken as it appears in Mrs.

Kamla Matuur And Another Order 39 of the Code of Civil Procedure. In my judgment there is

no reason to suppose that any such power was intended to be conferred by the terms of rule 2

of that order. It is quite true that the phrase used is "the person guilty of such disobedience or

breach.".......... 'The person guilty of such disobedience or breach" includes a person guilty of

any such terms. It seems to me wrong to argue that clause (3) is intended to give the court

power to visit for contempt of court people against whom noorder is made or terms imposed. I

have the greatest difficulty in seeing that anybody can be guilty of disobedience of

an order except the person to whom the orderis directed."

(15) In that case the District Judge had not only punished for contempt of court the persons who were

guilty of breach of his order, but had also directed the properties of . a person to be attached who was

abetting other people in committing contempt of court. Rankin Cj held that the district judge had no

jurisdiction to make the order against the alleged abettor or aider. This is a weighty authority having

regard to the eminence of Rankin Cj who decided it. It is a clear authority against the proposition

contended for.

(16) Following Mawazzam Ali's case (supra) Niyogi J. in Distt. Judge, Chhindwara v. Basori Lal

MANU/NA/0065/1939 held that the terms of Order 39 rule 2 do not contemplate punishment of one

who, not being a party bound by injunction, incites or aids in the commission of its breach. (See also

Bai Mani v. Bhailal Chunilal. MANU/MH/0083/1929 : Air 1929 Bom 417.

(17) In Off. Assignee v. Suryakan Thammal Air 1938 Mad. 927 Loach Cj and Ayyangar J. took a

contrary 545(16) to a case of insolvency under Section 58(5) of the Presidency Towns Insolvency Act,

1909.

(18) In Pratap Udai Nath v. Sara Lal MANU/BH/0211/1948 : AIR1949Pat39 a special bench of

Agarwala Cj, Meredith and Narayan Jj held that equity acts in personam and an injunction is a personal

matter. The ordinary rule is that it can only be disobeyed in contempt by persons named in the writ.

Persons who were not defendants in the suit in which the injunction was granted nor were named in

the decree cannot be proceeded against in contempt for disobeying the injunction, even if such persons

claim through the person against whom the injunction was granted. The special bench held that the

decision of the Privy Council in the case of S. N. Banerjee v. Kuchwar Lime & Stone Co. Ltd..

MANU/PR/0060/1938 was conclusive upon the point before them. Jn that case the Patna High Court

had held that the Secretary of State for India and -the Director , the Manager of the Kalyanpur Lime

Works were guilty of contempt for interfering with a former lessee under the Government, the Kuchwar

Lime and Stone Company Ltd. in breach of an injunction against the Secretary of State. "The Privy

Council held that there had been no contempt by the Secretary of State. But they were pressed with

the argument that Ghosh and Banerjee of the Kalyanpur Company were nevertheless guilty of

contempt for aiding and abetting. The Privy Council said :

' THE respondents ,however, contended that even if the Secretary of State was nut himself

guilty of direct disobedience to the injunction which had been granted, yet the other two

appellants were guilty of contempt upon the principles set out in Avery v. Andrews. 51 L. J. Ch.

414 46 L. T. 279 and Seaward v. Paterson (1897) 1 Ch. 545 : 66 L. J. Ch. 267. In terms,

however, those cases limit the offence of contempt by a person not a party to the injunction to

cases where they aid and abet the party enjoined in its breach. Where, as here, that party has

not broken the injunction it is impossible to hold that anyone has aided or abetted them in

breaking it. The respondents sought to avoid this difficulty by maintaining that the doing by

anyone of an act which was forbidden by the injunction was itself an offence. Their lordships

can find no authority for so wide a proposition. It is certainly not enunciated or indeed hinted at

the cases referred to nor do they think it is sound in principle."

(19) The Privy Council was then pressed with the argument that Ghosh and Banerjee were bound by

the injunction as deriving title from the Secretary of State. To this they said :

" THE utmost which the respondents would say was that the Kalyanpur Company, having

derived their supposed interest from the Secretary of State, who had been forbidden to

interfere with the respondents' lease, were acting against the spirit if not the letter of the

injunction in taking or continuing in possession of the quarries, and were Therefore guilty of

contempt in interfering with the respondents' lease. The fact, however, that Gosh and Banerjee

claimed on behalf of their Company to derive title, rightly or wrongly (and their Lordships will

assume wrongly), through the Secretary of State, cannot in their view make them liable

HCD/82-5 for an act not forbidden to them though forbidden to him."

(20) From the above rulings two propositions emerge, Firstly, a person not a party to the suit cannot

be proceeded against for contempt for aiding and abetting the breach. Secondly, the jurisdiction to

punish for disobedience of the injunction order vests in the court which ranted the injunction.

(21) The next question is : Can an 'aider and abettor' be proceeded against under the Act ? I think not.

The only allegation against the husband is that he "is aider and abettor of contempt" as he "is

supervising the fresh illegal construction activities". This is an allegation more like an allegation against

in agent than an abettor. The plaintiff has in effective alternative remedy against the principal party

bound by the injunction and her agents and servants. We have not been shown any reported decision

in India where the court punished an aider and abettor.

(22) Civil contempt is defined in Section 2(b) of the Act. it "means willful disobedience of any

judgment, decree, direction, order, writ or other process of a court or willful breach of an undertaking

given to a court". This does not deal with the case of temporary injunctions because that subject is

specially dealt with in Order 39, Civil Procedure Code . Aider and Abettor :

(23) Then there is another difficulty in the way of the plaintiff. Unless it is held that the wife is guilty of

disobedience of the injunction order or breach of its terms there can be no question of aiding or

abetting. Unless there is a principal offender there can be no aider or abettor. The culprit's guilt must

first be established. The court must first find who is the principal offender. She can only be the wife

because she is the defendant to the suit. If it is held that she is not guilty of disobedience of the

injunction or breach of its terms, there will be no question of the husband aiding and abetting her. Who

will find whether the wife is guilty of disobedience of the injunction order ? It can only be, I think, the

court of the subordinate judge, which granted the injunction order. The High Court cannot decide in

lieu of the court granting the injunction. The subordinate judge is the best person to interpret his

own order and to find, after taking evidence, whether the defendant is guilty of willful disobedience of

the injunction order issued by him. Criminal contempt :

(24) Counsel for the plaintiff says that the husband is guilty of criminal contempt of court. I do not

agree. This is not a case of criminal contempt. Criminal contempt means :

" THE publication (whether by words, spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible

representation, or otherwise) of any matter or the doing of any other act whatsoever which (i)

scandalizes or tends to scandalise, or lowers or tends to lower the authority any court; or (ii)

prejudices, or interferes or lends to interfere with the due course of any judicial proceeding; or

(iii) interferes or tends to interfere with, or obstructs or tends to obstruct the administration of

justice in any other manner;"

(25) In Advocate General Bihar v. M. P. Khair Industries MANU/SC/0504/1980 : 1980CriLJ684 (19)

the Supreme Court described the nature of criminal contempt in these words :

" IT may be necessary to punish as a contempt, a course of conduct which abuses and males

mockery of the judicial process and which thus extends its pernicious influence beyond the

parties to the action and affects the interest of the public in the administration of justice. The

public have an interest, an abiding and a real interest, and a vital stake in the effective

and orderly administration of justice, because, unless justice is so administered, there is the

peril of all rights and liberties perishing. The Court has the duty of protecting the interest of the

public in the due administration of justice and. so, it is entrusted with the power to commit for

Contempt of Court, not in order to protect the dignity of the Court against insult or injury as

the expression "Contempt of Court" may seem to suggest, but to protect and to vindicate the

right of the public that the administration of justice shall not be prevented, prejudiced.

obstructed or interfered with. "It is a mode of vindicating the majesty of law, in its active

manifestation against obstruction and outrage".

Per Frank Furter, J. in Offutt v. U. S. 1954 348 Us 2.

" THE law should not be seen to sit by limply, while those who defy it go free, and those who

seek its protection lose hope". Per Judge, Curtis-Releigh quoted in Jennison v. Baker (1972) 1

All. E.R. 997."

(26) The essence of criminal contempt consists in the doing of something calculated or designed to

obtain a result of legal proceedings different from that which would follow in the ordinary course.

(Lechmere Charlton's case (1836) 40 E.R. 661 per Lord Cottenham). It deals, to use the words of

Lopes L.J.. with something outside the cause and, is not a mere step in the cause. (O'shea v. O'shea

and Panel 15 Pd 59) (21). Criminal contempt is external to the administration of justice and truly

subversive of it. It is an obstruction and outrage against the public administration of justice. It is

essentially criminal in character. It is the foulest contamination which can infect the judicial system. It

is a great evil. A court has to protect its administration of justice and all those who share or are

convened to its labors .Judges, witnesses, juroxs, process servers, etc. all have to be protected. And a

court of justice can protect itself against the outrage by suppression and punishment. But this power to

commit must be used sparingly and with the greatest caution. The greater the power the greater the

restraint.

(27) 'CRIMINAL Contempt' may be defined as contumelious or obstructive behavior directed against

the court and one example of this is contempt in the face of the court. It is an obstruction of justice, a

sinning against the majesty of the law and the Time-honored jurisdiction over .such offences is now

undisputed. Criminal contempt; has been defined as despising of the authority of court. Sometimes by

using words importing scorn, reproach or diminution of the court, its process, orders, officers, or

ministers, upon executing or serving such process or orders. The distinction between civil and criminal

contempt :

(28) What is the distinction between civil contempt and criminal contempt ? Civil contempt or contempt

in procedure as it is called, consists of failure to comply with an order of the court. The law provides

sanctions for an enforcement of the process and orders of a court. Although civil contempt is basically

a wrong to the person who is entitled to the benefit of the court order, there has always been a

punitive element in the civil contempt disobedience. of a court order of injunction, for example, can

result in a committal to prison just as a criminal contempt can. But civil contempt is essentially

remedial and coercive. Civil contempt of court exists to provide the ultimate sanction. against him. who

refused to comply with the order of a properly constituted court. The jurisdiction in respect of civil

contempts is primarily remedial, once the offender complies with the court's order he has a right to be

released, whereas there is no such right in respect of criminal contempts.

(29) Criminal contempts are essentially offences of a public nature and consist of publications or acts

which interfere with the due course of justice as, for example, by tending to jeopardise the fair hearing

of a trial or by tending to deter or frighten witnesses or by interrupting court proceedings or by tending

to impair public confidence in the authority or integrity of the administration of justice. Civil contempts,

on the other hand. are committed by disobeying court judgments or orders either to do or to abstain

from doing particular acts, or by breaking the terms of an undertaking given to the court, on the faith

of which a particular course of action or inaction is sanctioned, or by disobeying other court orders.

Civil contempts are Therefore "offences" essentially of a private nature since they deprive a party of

the benefit for which the order was made. The essence of the. court's jurisdiction in respect of criminal

contempts is penal, the aim being to protect the public interest in ensuring that the administration oi'

justice is duly protected. On the other hand. the court's jurisdiction in respect of civil contempt is

primarily remedial, the basic object being to coerce the offender into obeying the court's judgment

or order. (Borrie & Lowe-Law of Contempt pages 369-370).

(30) This then is the distinction between 'civil contempt' and 'criminal contempt'. This distinction is

made in the Act. The disobedience of injunction is a civil contempt Strictly speaking it does not fall

within section 2(b) of the Act. It is specifically dealt with in Order 39 of the Code. But it is not a

criminal contempt. The argument that the act of aiding and abetting a breach of injunction amounts to

a criminal contempt is based on the leading English case of Seaward v. Paterson (1897) 1 Ch. 545. ft

concerned a promoter who had arranged boxing matches on residential premises in London and

thereby knowingly assisted the lessee to disobey an order enjoining him from committing a. nuisance.

In the course of his judgment in the Court of Appeal upholding the promoter's committal for contempt.

Lindley L.J. distinguished between "a motion to commit a man for breach of an injunction, which is

technically wrong, unless he is bound by the injunction" and a "motion to commit a man for contempt

of court, not because he is bound by the injunction by being a party to the cause, but because he is

conducting himself so as to obstruct the course of justice.' The inference to be drawn from this

distinction made by Lindley Lj is that the liability of the promoter was considered to be as for a criminal

contempt of court. In Scott v. Scott (1913) A.C. 417, however, Lord Atkinson denied that this was so,

and himself suggested that it would be absurd if a criminal contempt were to be committed by one who

was not personally prohibited from doing the act in question, while no more than a civil contempt was

committed by one who was. A third party which is said to be guilty of aiding and abetting the contempt

incurs the liability of a principal offender. The powerful speech of Lord Atkinson Scott v. Scott (supra),

shows that an aider and abetter will also be guilty of a civil contempt because the principal is guilty of

civil contempt. (See Miller Contempt of Court pp. 249-250). Salmon Lj has said :

" A stranger who helps the defendant to breach the injunction is sent to prison, no doubt as a

punishment for contempt but the effect of sending him to prison is also an indirect en-

forcemeat of the order which benefits the plaintiff."

(Jennison v. Baker (1972) 1 All Er 997. So on any view it is a civil contempt. There is no element of

criminality in it. It is not per se a crime. All that has been said against the husband is that he has

participated in defying the injunction. Has he participated in a criminal act? The answer must be "no".

(31) The Privy Council in S. N. Bannerjee v. Kachwar Lime & Stone Co. (supra) said :

"IT is now sufficiently established that a committal for a finding of contempt for breach of an

injunction is not criminal in its nature and is properly dealt with under the Civil Procedure Code.

See Scott v. Scott (1913) Ac 417."

(32) We have the high authority of the Privy Council for the proposition that the breach of injunction is

a civil contempt. It is so in the case of wife. It will be so in the case of the husband if he can be held

guilty of disobedience of an injunction which forbade hill not. There is no question of criminal

contempt. The "Privy Council is referring to the speech of Lord Atkinson at page 456 in Scott v. Scott

(supra) with approval and saying that the matter is governed by the Code of Civil Procedure. The Code

is a comprehensive and complete refutation of the plaintiff's case. I, Therefore, reject the contention

that the present is a case of criminal contempt. Sections 10 and 12 of the Act invoked by the plaintiff

have no application. It is not a case of contempt of the subordinate courts which the High Court should

punish.

(33) In my view Seaward v. Paterson (supra) on which plaintiff's counsel relies heavily has no

application to the facts of this case. In England that jurisdiction has been exercised for a very long time

for longer than any of us can remember" and was held to be "undoubted" (per Rigby Lj at page 558).

Recently Lord Denning followed Seaward v. Paterson in Acrow (Automation) Ltd. v. Rex Chain-

belt(1971) 3 All E.R. 1175. Whether we have the same jurisdiction I do not decide. Rankin Cj denied

jurisdiction to Indian Courts as long ago as 1927 in Mawazzam Ali. He had in mind Seaward v.

Paterson. the said that in India the Code of Civil Procedure does not permit the court to punish an

aider and abetter. "I have the greatest difficulty", he wrote, "in seeing that anybody can be guilty of

disobedience of an. order except the person to whom the order is directed. The reason is that Indian

law is codified and the statute will govern us. Therefore my conclusion is this. Order 39 does not

empower the court to punish an "aider and abettor". Under the Act of 1971 it is not a criminal

contempt.

(34) The plaintiff's counsel referred us to an unreported judgment of a division bench (Prakash Narain

and F. S. Gill JJ) in Criminal Original 68 of 1977 decided on 23-2-1979 : Raj Prakash vs. Choudhry

Plastic Works(24). That was a patent case. The High Court passed a decree of injunction in plaintiff's

favor. The defendant disobeyed the decree. It was a case of willful disobedience of the undertaking

given to the High Court. The division bench punished the defendant for a deliberate disobedience to

an order of the court and breach of the undertaking given to the court. The judges held that it was a

case of civil contempt. This case illustrates that civil contempt is "essentially a wrong to the person

entitled to the benefit of the order or undertaking". It involves private injury. No public interest is

involved. Only the particular interests of the parties to the case are affected. Rai Prakash's case much

relied on, by no means supports the plaintiff's contention but tends strongly to negative it. It will not

like to comment on it further as it is in appeal to the Supreme Court,

(35) Here we are asked to punish the husband for criminal contempt. The utmost that can be said is

that he is obstructing in the administration of civil justice. But the court has not issued any injunction

against him. Nor forbade him to do any act. Assuming that he supervised the construction the act does

not 'savour of criminality". One who encourages another to act in breach of an injunction is not a

criminal. An order of the court in a civil suit creates an obligation upon the parties to whom it applies,

the breach of which will be punished by the court, and in proper cases such punishment may include

imprisonment. But it does no more. It does not make such disobedience a criminal act. The Courts in

India have consistently and without any exception held that the orderspunishing persons for

disobedience to an order of the court are civil contempt for which an effective remedy is provided in

the Code. So the principle of Civil contempt is rooted in the Codes. It it rooted in the wisdom of a

century of justice in India.

(36) The Act makes a clear distinction between civil and criminal contempt. We have to observe it.

Salmon Lj expressed the opinion that there is no real justification for making distinction between civil

and criminal contempt. In Jenison v. Bakar (supra) he said :

" CONTEMPT Shave sometimes been classified as criminal and civil contempts. I think that at

any rate today, this is unhelpful and almost meaningless classification."

(37) We cannot ignore this distinction because the Act makes it. Each case will depend on its facts, the

distinction being between process to compel performance of a civil obligation and process to punish

conduct which has about it some degree of criminality, some defiance of the general law. (Stourton v.

Stourton (1963) P. 302 per Scarman J). In the present case I am clearly of the opinion that the

process of contempt is being used to compel performance of a civil obligation. It is a civil process. It is

a civil contempt, if proved. I do not regard the case as one of criminal process or the facts of this

particular case as having a criminal character. Appeals

(38) There is another good reason why this application must fail. The plaintiff wants us in the High

Court to try both wife and husband for contempt. Suppose we do. It will lead to startling results.

The order of injunction was made by the subordinate judge under Order 39, Civil Procedure Code .

From his order appeal lay to the court of the senior subordinate judge. Appeals were actually filed in

that court and were heard and dismissed by the senior subordinate judge. For disobedience the wife

can be punished under Rule 2A of Order 39 by the subordinate judge. An appeal lies from

hisorder under that rule. An order under rule I, rule 2 and rule 2A of Order 39 has been made

expressly appealable under Order 43 rule I (r). All these appeals in the present case will lie to the

senior subordinate judge, the valuation of the suit being Rs. 200 for purposes of court fee and

jurisdiction as fixed by the plaintiff. It would be anomalous to hold that the High Court can punish for

contempt under the Act or Constitution committed of the sub judge's order.

(39) The Code of Civil Procedure does not contemplate this. It expressly provides for grant of

injunctions and the punishment for their disobedience. Appeals lie against grant of injunctions. Appeals

lie against punishment. Appeals lie against the order to punish or refusing to punish for disobedience.

The High Court does not come info the picture at all. It is neither a case of civil contempt nor criminal

contempt under the Act. It is a plain case falling within the four corners of Order 39 of the Code of

Civil Procedure. To hold that the High Court has power to punish will be to hold that the subordinate

judge has the power to grant injunction, but the High Court has the power to punish for the

disobedience of his order under Sections 10 and 12 for civil and criminal contempt because aiding and

abetting is alleged.

(40) If this argument of plaintiffs counsel is accepted it will create chaos. Where will appeals lie no one

will know. The absurd anomaly will be this : that the principal who does an act he is expressly

prohibited by injunction from doing shall only be guilty of a civil contempt of court, while a person not

expressly or at all prohibited who aids and abets the principal in doing that very act shall be held guilty

of a criminal contempt of court, with the result that the more flagrant transgressor of the two. the

principal would have a right to appeal to the court of senior sub-judge as in this case against

any order punishing her for her misdeed, while the abettor would have a right "if appeal to the

Supreme Court from our order punishing him for "aiding and abetting" the principal to commit the

Forbidden act. The disrespect to the court which made the order that was disobeyed, and the defiance

of its authority. would seem to be greater in the case of the principal than in that of an abettor.

(41) There is another absurdity. If we try the wife for civil contempt under the Act a single judge will

do it But the husband will have to be tried by two judges for criminal contempt. This will also result in

appeals being taken to different courts. For my part, I refuse to give the statute a meaning which leads

to an impractical and ridiculous result unless compelled to do so by the language of the statute itself or

by a clear authority which is binding on this court. I can find nothing in the Act or the Consultation

which supports the argument on behalf of the plaintiff. Conclusion :

(42) The mere disobedience by a party to a civil action of a specific order of the court made on him in

the suit is "civil contempt". The order is made at the request and for the sole benefit of the other party

to the civil suit. There is an element of public policy in punishing civil contempt, since the

administration of justice would be undermined if the order of any court of law could be disregarded

with impunity, but no sufficient public interest is served by punishing the offender if the only person for

whose benefit the order was made chooses not to insist on its enforcement. A. G. v. Times

Newspapers Ltd. (1973) 3 Wlr 298 per Lord Diplock.

(43) All that is at stake in the present case is the private rights of the parties. For defiance of the

courts under the remedy is provided in the Code. It is attachment and detention in civil prison. For

deliberate defiance of interim injunctions the court can send the contemner to prison. If the

subordinate courts cannot enforce their injunctions the order virtually would be worthless. It is the

deterrent effect of an injunction plus the liability to imprisonment for its breach which is the remedy.

The subordinate judge can punish the defendant if he finds her to be guilty in flagrantly defying

the order which he had made. Contumacious disregard and contemptuous disobedience if

the orders of the court have always been visited with committal to prison and attachment. Against the

husband no case of criminal contempt has been made out. It seems to me that the application is

wholly misconceived.

(44) Founding himself on Seaward v. Paterson counsel argued that the husband incited the wife in

continuing the construction in defiance of the order of the court. It was argued that the husband's

support and endorsement of the action of the defendant in setting the court at defiance is a criminal

contempt. With this contention I do not agree. In that case the principal Paterson, his agents and

servants were restrained by injunction from, amongst other things having, or permitting to be held,

exhibitions of boxing on his premises. He held, or permitted to be held there, such an exhibition in

breach of this injunction. One Murray, who was neither his agent nor servant, was present at the

exhibition, aiding and abetting Paterson in holding it. The plaintiff moved that both principal and the

abettor should be committed for breach of the injunction. The whole controversy before North J. was

whether Murray could be committed, as he was not a party to the suit and was no" named in the

injunction. The learned judge held that he could be committed, not indeed for breach of the injunction

but for contempt of court in aiding and abetting Paterson in doing an act which the latter was by the

injunction prohibited from doing, and committed both Paterson and Murray to prison. Murray alone

appealed from this order to the court of appeal. In the appeal the order of North J. was upheld.

(45) Seaward v. Paterson has given rise to much controversy which in the present case it is not

necessary to resolve. In Scott v. Scott (supra). Lord Atkinson in a devastating criticism exploded the

view that the act of Murray amounted to criminal contempt. Salmon Lj in Jennison v. Baker (supra)

regards it as a case of civil contempt. It was followed in Acrow (Automation) by Lord Denning and

Cross J. in Phonographic Performance Ltd. v. Amusement Caterers Ltd. (1963) 3 Wlr 898. In India its

applicability to injunctions was denied by Rankin C..T. in Mawaz- zam Ali. Niyogi J. in District Judge v.

Basori Lal followed him. In Madras Leach C.J. applied it in Official Assignee v. Suryakanthammal in a

case of insolvent's contempt. Chawla J. in this court approvingly referred to in a case of disobedience

of court's order See Kuldip Rastogi v. Vishva Nath, MANU/DE/0024/1979 : AIR1979Delhi202 .

(46) There is no agreement amongst the judges on its true ratio decidendi. In a trenchant criticism of

the view that this case is an authority on criminal contempt Lord Atkinson said "I cannot agree that

disobedience per se of an order of the court irrespective of the nature of the thing ordered to be

done, is a criminal offence." (Scott vs. Scott). Scott v. Scott and Jennison v. Baker (supra) take the

view that in Seaward v. Paterson the action amounted to a civil contempt. Cross J. in Phonographic

Performance assumed that the act amounted to a criminal contempt. Oswald and Fox in their treatises

on contempt classify adding and abetting breach of injunction as a criminal contempt. Miller in his book

on Contempt of Court takes the view that a person rendering assistance commits a criminal contempt.

(page 248). Borrie and Lowe in their book on The Law of Contempt sum up the controversy in these

words :

" ANOTHER type of contempt which is difficult to classify is aiding and abetting a breach of

injunction. It can be argued that such an act amounts to a criminal contempt since the offence

is not committed by a party to the action and the act clearly impedes the due course of justice.

On the other hand it can equally well be argued that the act amounts to a civil contempt, the

punishment of the offender being an indirect means of enforcing the court order for the benefit

of the plaintiff. Authority can be found to support both of these views."

(47) This controversy shows at least one thing. Despite many important differences between them, it is

possible to see in civil contempt and criminal contempt a number of 'family resemblances', to adopt a

useful phrase of the philosopher Wittgenstein .The line of demarcation is thin. It is difficult in some

cases to say on which side of the line a case falls. Both tend to undermine the administration of justice.

(48) In India the position is different. In this country the authoritative decision is of the Privy Council in

S. N. Banerjee v. Kuchwar Lime & Stone Co. Ltd (supra). The Privy Council has held that disobedience

of the breach of injunction is a civil contempt governed by the Code of Civil Procedure. For their

decision they relied on Scott v. Scott (supra). The Patna High Court had relied on Seaward v. Paterson.

Reversing the High Court the Privy Council held that Seaward v. Paterson did not apply to the case

before them. I would say the same. Seaward v. Paterson does not apply to the present case. This is a

straight forward case of an injunction granted by the subordinate judge and the plaintiff alleging its

disobedience by the defendant and her husband. The answer is : "Go to the court which issued the

injunction".

(49) Mr. Ramachandran in his Contempt of Court (4th ed.) at page 646 says that the principle in

Seaward v. Paterson that persons aiding and abetting the principal offender are also liable in contempt,

has not been followed in India. He refers to Maharaj Pratap Udai Nath v. Sara Lal MANU/BH/0211/1948

: AIR1949Pat39 and the Privy Council in S. N. Bannerjee (supra) in this connection. I have come to

the conclusion that for the purposes of this case it is unnecessary to determine the parameters of

Seaward v. Paterson or to decide how far that case can be followed in India.

(50) For these reasons I would dismiss the application but make no order as to costs. I make it clear

that if the plaintiff desires he may move an appropriate application to the subordinate judge under Rule

2A of Order 39, Code of Civil Procedure for disobedience of the order of injunction. The subordinate

judge will decide the application according to law. I say nothing on the merits of the case.

Manupatra Information Solutions Pvt. Ltd.

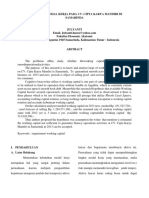

MANU/PH/1350/2001

Equivalent Citation:

IN THE HIGH COURT OF PUNJAB AHD HARYANA

C.O.C.P. No. 1540 of 2000

Decided On: 01.06.2001

Appellants: Gajjan Singh

Vs.

Respondent: Tersam Lal, Assistant Sub Inspector of Police

Hon'ble Judges/Coram:

Bakhshish Kaur, J.

Counsels:

For Appellant/Petitioner/Plaintiff: Mr. J.S. Gill, Adv.

For Respondents/Defendant: Mr. B.R. Mahajan, Adv.

Subject: Contempt of Court

Catch Words

Mentioned IN

Acts/Rules/Orders:

Contempt of Courts Act, 1973 - Sections 2 and 12; Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) - Section 151

- Order 39, Rules 1, 2 and 2A(1)

Cases Referred:

Dr. Bimal Chandra Sen, Delhi v. Mrs. Kamla Mathur, Delhi and another, 1983 Crl.L.J. 495;Om Parkash

Jaiswal v. D.K. Mittal, 2000 AIR SCW 722; Murray & Co. v. Ashok Kr. Newatia and another, JT

2000(1) 337 (S.C.)

Citing Reference:

Discussed

3

Case Note:

Contempt of Court - Violation of the decree - Suit filed for permanent injunction - Learned

Civil Judge decreed the suit in favour of the Petitioner - Contempt petition filed under

Section 12 of the Contempt of Courts Act, 1973 as the Respondent violated the decree

passed by the Civil Judge and threatened family members of the Petitioner in his absence -

Held, Respondents were neither a party to the suit nor a specific order of restraint was

passed against them due to which no case was made out for initiating contempt

proceedings against them - Petitioner had already taken steps by proceeding against the

Respondents by submitting a complainant - Petitioner was within his right to pursue the

complaint and seek the redressal of his grievances - Hence, petition dismissed.

Disposition:

Petition dismissed

JUDGMENT

Bakhshish Kaur, J.

1. The petitioner has filed this contempt petition under Section 12 of the Contempt of Courts Act (in

short 'the Act'). It is alleged that the respondents have deliberately violated the decree passed by the

Civil Judge (Senior-Division), Patti.

2. Gajjan Singh-petitioner claiming himself to be in possession of the land measuring 9 kanals 7

marlas (as mentioned in the judgment Annexure P-1 but 7 kanals; 9 marlas as mentioned in the

petition) filed a civil suit No. 145 of 20.6.2000 for permanent injunction restraining Balkar Singh,

Anokh Singh and Bikkar Singh from dispossessing him forcibly except in due course of law.

3. Bikkar Singh and other defendants though contested the claim of the petitioner, did not lead any

evidence to support their pleas raised in the written statement, Therefore, the learned Civil Judge

(Senior Division), Patti decreed the suit in favour of the petitioner. Copy of the judgment is Annexure

P-1.

4. On November 9, 2000, us averred in the petition, respondent Nos. 1 to 9 along with three

policemen, came to the fields of the petitioner and started ploughing the fields with tractor, The

petitioner pleaded with them not to damage the wheat crop sown by him. He had also submitted

certified copy of the judgment and decree dated 3.11.2000 and apprised them of the situation that he

is in possession of the land for the last 20 years. Shri Tarsem Lal, Assistant Sub Inspector before

whom the order was produced tore away the copy of the order and remarked that in the area he is

the sole authority and this piece of the paper is not help to the petitioner. The petitioner has also met

respectable of the village and the matter was taken by Shri V.K. Mal-hotra, President of All India

Welfare Sangarsh Committee and representations were sent along with copy of the decree as well as

revenue record to Chief Justice of Punjab and Haryana High Court, D.G.P. Chandigarh, I.G. Amritsar,

D.C. Amritsar, SSP Tarn Taran, DSP Bhikhi Wind. The Deputy Superintendent of Police marked the

representations for enquiry to the SHO Bhikhi Wind, but again the petitioner had to face the wrath of

Shri Tarsem Lal, ASI-respondent No. 1 as he came to the house of the petitioner and in his absence

threatened his family members of teaching the petitioner a lesson.

5. In response to the show cause notices issued to the respondents, Tarsem Lal, ASI-respondent No.

I, Sukhwant Singh-respondent No. 2 for himself as well as on behalf of other respondents submitted

joint reply. They have denied the averments contained in the petition. Respondent Nos. 2 to 10 have

also raised a preliminary objection that the answering respondents were not party to the civil suit filed

by the petitioner against his cousin brothers Balkar Singh and others, therefore, this petition is liable

to be dismissed as it amounts to misuse of the process of the Court. It is also denied that the

petitioner is in possession of 7 kanals 9 marlas of land bearing Khatta No. 31, khatauni No. 128 and

Killa No. 46/14/2.16. It is, however, admitted that the land belongs to Gurudwara Gu-rugranth Sahib

and the Gurudwara Committee has been leasing out this land to different persons from time to time.

6. I have heard Shri J.S. Gill, learned counsel, for the petitioner and Shri B.R. Mahajan, learned

counsel for the respondents.

7. A bare perusal of the judgment Annexure P-l would indicate that the suit for permanent injunction

was filed against Balkar Singh, Anokh Singh and Bikkar Singh and none of respondents were arrayed

as defendants in the suit, Annexure P-2 is copy of the interlocutory order passed by the Vacation

Judge, Patti on June 24, 2000. The suit was instituted on June 20, 2000. The defendants who had

appeared before the trial Court i.e. the Vacation Judge had made the statement in the Court that they

have no objection if the application of the plaintiff under Order 39 Rules 1 and 2 and Section 151 CPC

is allowed since the plaintiff is in possession of the suit land,

8, Whether any case is made out for initiating contempt proceedings against the respondent ? Before

doing so, the sequence of events resulting into the filing of the civil suit, passing of the ex parte

decree in favour of the plaintiff, need to be taken into consideration and these are summarised as

under :-

(1) Civil suit for permanent injunction was filed during vacations on June 20, 2000;

(2) Defendants to the suit immediately appeared before the Judge four days thereafter i.e.

on June 24, 2000 and stated that they have no objection to the Order 39 Rules 1 & 2 CPC;

(3) The Vacation Judge adjourned the case to July 17, 2000 for filing of written statement;

(4) On July 17, 2000 when the defendants filed the written statement, they raised a specific

plea that the suit land is under the ownership of Gurudwara Guru Garanthsahib and the

plaintiff is not in possession of the suit land. The entries of Jamabandi and Khasra Girdawaris

have been got effected by the plaintiff wrongly in his name in connivance with the revenue

authorities. Whereas on June 24, 2000 they had made a contradictory statement that the

plaintiff is in possession of the suit land and the application under Order 39 Rules 1 and 2

CPC may be allowed.

(5) The defendants to the suit are stated to be cousin brothers of Gajjan Singh-petitioner.

9. Upon the aforesaid circumstances, the suit of the plaintiff was decreed. A bare perusal of the

judgment Annexure P-l shows that the suit was not seriously contested by the defendants. Firstly,

they had led no evidence. Secondly, counsel for the defendants did not press issue Nos. 2, 3 and 4

which related to the maintainability of the suit, especially the locus standi of the plaintiff in filing the

suit. With this background, when the parties to the suit are closely related, everything was done in a

hurried manner and above all, none of the respondents was a party to the civil suit, whether the act

of the respondents complained of in this petition, would in any way attract the penal consequences as

envisaged under Section 12 of the Contempt of Courts Act.

10. In Dr. Bimal Chandra Sen, Delhi v. Mrs. Kamla Mathur, Delhi and another MANU/DE/0426/1982

, it was held that the jurisdiction to punish for disobedience of, the injunction orders vests in the Court

which granted the injunction. The High Court has power under Section 10 of the Contempt of Courts

Act, but the exercise of that power is discretionary. The disobedience of an injunction is a civil

contempt. Strictly speaking, it does not fall within Section 2(b) of the Contempt of Courts Act. It is

specifically dealt with in Order 39 of the Code. Section 2(b) which defines Civil contempt does not deal

with the case of temporary injunctions because that subject is specifically dealt with in Order 39 CPC.

Sub-rule (1) of Rule 2 A confers on Courts the power to punish such contempt and, further, prescribes

the punishment to be awarded therefore Not only this, a person who is not a party to the suit cannot

be proceeded against for contempt for aiding and abetting the breach.

11. Under these circumstances, where the respondents were neither a party to the suit nor a specific

order of restraint was passed against them, then no case is made out for initiating contempt

proceedings against them. That is why the jurisdiction to initiate proceedings in contempt as also the

jurisdiction to punish for contempt in spite of a case of contempt having been made out are both

discretionary with the court. It has been observed in Om Parkash Jaiswal v. D.K. Mittai AIR 2000 SC

722, that the contempt generally and criminal contempt certainly is a matter between the court and

the alleged contemnor. No one can compel or demand as of right initiation of proceedings for

contempt'. A jurisdiction in contempt shall be exercised only as a clear case having been made out.

Mere technical contempt may not be taken note of. In Murray & Co. v. Ashok Kr. Newatia and

another MANU/SC/0042/2000 , it has been held by the Hon'ble Supreme Court in para 21 that

unless the court is satisfied that contempt is of such a nature that the act complained of substantially

interferes with the due course of justice, question of any punishment would not arise. It is not enough

that there should be some technical contempt of court but it must be shown that the act of contempt

would otherwise substantially interfere with the due course of justice which has been equated with

"due administration of justice. Further in para 24 it has been held that the Contempt of Courts Act

puts an obligation on the Courts to assess the situation itself as regards the factum of any

interference with the course of justice or due process of law.

12. The petitioner has already taken steps by proceeding against the respondents by submitting a

complainant Annexure P-3. He is within his right to pursue the complaint and seek the redressal of his

grievances.

13. For the aforesaid reasons, this petition is dismissed. My observations aforesaid be not construed

as expression of opinion which may ultimately affect the criminal proceedings initiated by the

petitioner against the respondents.

13. Petition dismissed.

Manupatra Information Solutions Pvt. Ltd.

MANU/WB/0212/1927

Equivalent Citation: AIR1927Cal598, 31CWN814

IN THE HIGH COURT OF CALCUTTA

Decided On: 12.04.1927

Appellants: Mawazzam Ali Khan and Ors.

Vs.

Respondent: Shebash Chandra Pakrashi and Anr.

Subject: Election

Catch Words

Mentioned IN

JUDGMENT

Rankin, C.J.

1. This is a somewhat unusual case and in certain aspects it is regrettable.

2. It appears that there was an election, the date of which is not given in the paper-book, for the

Serajgunj Local Board. One of the thanas that sent representatives to that Local Board is called the

Chauhali Thana, and it appears that a certain Babu Shebash Chandra Pakrashi was declared elected to

the Local Board for that thana. There was then a suit for setting aside that election and on the 9th

May 1925, by the judgment of the Munsif that election was declared invalid and Shebash Chandra

Pakrashi was restrained from acting as a member. There was a meeting of the Local Board on the 3rd

July 1925, apparently for the purpose of electing a Chairman and Vice-Chairman, and for electing nine

persons to represent the Local Board on the District Board.

3. It was at one time alleged that, apart from the circumstance that there was no representative from

the Chauhali Thana, other illegalities affected what was done in that meeting. The meeting having

been held on the 3rd July 1925, we find that on the 13th November 1925 Shebash. Chandra Pakrashi

and another gentleman who had been elected to the Local Board of Serajgunj instituted a suit and

presented a petition asking that a temporary injunction should be granted against the defendants

being the persons-elected to represent the Local Board on the District Board, restraining them from

attending at a meeting of the District Board which had been announced for the 26th November, that

is to say, 13 days after the suit and four months after the illegalities complained of. When this

meeting had been first announced I do not know. The Munsif dealt with the application for injunction

and we are informed that he dealt with it not as an ex-parte application, but in the presence of both

parties and he refused the application. This had happened on the 16th November 1925. Thereupon on

the 24th November proceedings took, place which to my mind are astonishing in more ways than one.

4. It appears that the District Judge was at the time sitting at Bogra - a place where he has to take

sessions and not a. place at which civil business is done by the District Judge at all. An application

was made to him on the 24th, November being the presentation of an appeal against the order of the

Munsif and being a petition asking for a temporary injunction to restrain the persons, whom I have

mentioned from attending this meeting on the 26th November, that is, in two days' time. The learned

District Judge who in the ordinary way would have had nothing to do with such an application-it being

part of the-legitimate business of the senior Subordinate Judge in charge of the office of the District

Judge at Pabna - made an order to issue notices upon the respondents to show cause on the 30th

November. "In the meantime, the respondents-are directed not to join in the said meeting" - in other

words (as the only question before the Munsif was whether those persons should be restrained from

taking part in the meeting of the 26th November) the District Judge reversed the decision of the

Munsif for all purposes and granted the very relief which the Munsif had refused - and all this in the

absence of the respondents.

5. The paper-book in this appeal does not contain the petition on which this District Judge acted in

this manner, but the document is on the record. It is a somewhat lengthy Bengali document and we

have done our best to discover what representation was therein made as to the irreparable injury that

would be sustained by the appellants if those nine persons were permitted to attend this meeting. It

appears that this document contains all sorts of grievances but it is entirely lacking in any statement

which purports in any sensible way to show that there would be any real injury at all. It is stated that

if the meeting of the Local Board held on the 3rd of July 1925 had been properly conducted, one of

the plaintiffs would have been elected to the District Board and that the Chauhali Thana was not

represented at the meeting of the 3rd July of the Local Board. One would have thought that no Judge

would think of interfering with the proceedings of a local authority on such materials. The petition is

demurrable and discloses no reason for a summary interference with the proceedings of the local

authority.

6. Now, there are two separate questions. The first question is whether the learned District Judge had

any jurisdiction to entertain this matter at all. The second question is whether the learned District

Judge was acting oppressively and wrongly in making the order with which we are now concerned.

There is a great difference between these two questions for the present purpose. Whether an order is

right or wrong, if it is made with jurisdiction it is the duty of the parties to obey the order and the

obedience that has to be given to orders of the Court cannot be dependent on people's opinion as to

their propriety. I proceed therefore to deal with the first question of jurisdiction.

7. In the Bengal, North-Western Provinces and Assam Civil Courts Act (Act 12 of 1887), Section 14

provides that it is for the Local Government, by notification in the official gazette, to fix and alter the

place or places at which any Civil Court under this Act is to be held. In this case the fixed place was

Pabna. By Section 10 it is provided that

in the event of the death, resignation or removal of the District Judge, or of his being

incapacitated by illness or otherwise for the performance of his duties, or of his absence from

the place at which his Court is held, the Additional Judge, or if an Additional Judge is not

present at that place, the senior Subordinate Judge present thereat shall, without

relinquishing his ordinary duties, assume charge of the office of the District Judge and shall

continue in charge thereof until the office is resumed by the District Judge or assumed by an

officer appointed thereto.

8. Now, under that section absence from the place at which the Court is held is dealt with in the same

way as resignation or removal or incapacity by illness and the duty of doing the work is cast

imperatively upon the Subordinate Judge. We also know that the office is to be resumed by the

District Judge according to the plain terms of the section. It was not disputed that in this case the

assumption of jurisdiction by the District Judge was irregular-certainly it was highly irregular and

particularly unwise.

9. But it is contended that he was not without jurisdiction, because, the District Judge, although he

was not at the place where his Court is held, must be taken to be still the District Judge and so the

procedure adopted by him cannot be said to be more than an irregularity, on his part. It is also

argued that there may be at the same time two officers each of whom is discharging the office of the

District Judge. In my opinion, however, the statute cannot be so construed. There is no intention on

the part of the legislature to have a duplication of characters or to give people a choice to go before

one officer or another. If, for example, one puts to oneself the question whether this District Judge at

Bogra could have summoned parties in a contested case before him at Bogra and proceeded to

exercise civil jurisdiction over them, then the answer must be that such proceedings would be wholly

without jurisdiction. The parties would have been under no duty or obligation whatever to attend the

Court. In my judgment the learned District Judge having left Pabna and being absent from the place

where his Court was held, the only person who had any right to deal with the appeal was the

Subordinate Judge who was then discharging the office of the District Judge. In my opinion therefore

this order of the District Judge is without jurisdiction. I have already pointed out that it was, in any

possible view, irregular. Nobody supposes that it was in any way usual that civil business of Pabna

should be done at Bogra. The order made was also wrong on the merits.

10. There is another point, however, which requires to be animadverted upon. It appears that there

was a certain pleader who was a candidate for the Chairmanship of the District Board, and, the

defendants in this case were apparently-most of them-his supporters. On evidence which does not

appear to me to be very definite or very strong the District Judge found that these people had been

heard discussing the matter and that this pleader had been heard saying that the order was made

without jurisdiction and that it would be no offence if it was disobeyed. In that view the learned

District Judge has not only punished for contempt of Court the parsons who were guilty of a breach of

his order of the 24th November 1925, but he has directed the properties of this pleader to be

attached as a person who was abetting the other people in committing the contempt of Court.

11. There can be no doubt that according to the English cases there does exist in the High Court in

England a power to commit for contempt persons who abet disobedience of an injunction. Bit for the

purposes of the mofussil Courts this jurisdiction has to be taken as it appears in Order 39 of the Code

of Civil Procedure, In my judgment there is no reason to suppose that any such power was intended

to be conferred by the terms of Rule 2 of that order. It is quite true that the phrase used is "the

person guilty of such disobedience or breach." It is used with reference to Clause (1) and Clause (2).

Clause 2 gives the Court the power of granting an injunction

on such terms as to the duration of the injunction, keeping an account, giving security or

otherwise as the Court thinks fit.

12."The person guilty of such disobedience or breach" includes a person guilty of a breach of any such

terms. It seems to me wrong to argue, that Clause (3) is intended to give the Court power to visit for

contempt of Court people against whom no order is made Or terms imposed. I have the greatest

difficulty in seeing that anybody can be guilty of disobedience of an order except the person to whom

the order is directed.

13. There is a still further point about the order under appeal. That order directs the attachment of

the properties of all the parties, and, as regards Respondents. Nos. 1 and 3 to 9 it directs that they be

detained in civil prison for a fortnight as well. It is quite true that the terms in which Rule 2 of Order

39 is expressed are misleading and ill-advised in that they read as if the Court were obliged to order

an attachment of property and unles9 this is done, cannot order imprisonment. That may be the

reason why the learned District Judge has made the orders in the way he has done.