Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Goffman Gender

Загружено:

Verónica UrzúaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Goffman Gender

Загружено:

Verónica UrzúaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

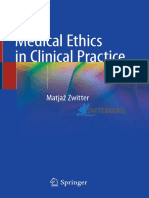

GEIITIER ATNENTISEIIEIIT$

GETIDER ATIUERTISEIIEIITS

Erving Gollman

(

HARPER TORCHBOOKS

Harper & Row, Publ i shers, New York

Cambri dge, Phi l adel phi a, San Franci sco, Washi ngton

London, Mexi co Ci ty, Si o Paul o, Si ngapore, Sydney

cENDER ADVERTTsEMENTs. Copyri Sht O 1976 by rvi n8 Cof f man l nt roduc-

t i on copyri ght O 1979 by Harper and Row Publ i shers, I nc Al l ri Sht s

reserved. Pri nt ed i n t he Uni t ed St at es of Ameri ca Nopart of t hi sbookmay

be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permis-

sion except in the case of briefquotations embodied in critical articles and

reviews. For information address Harper & Row, Publishers, lnc., l0 East

5l rd St reet , New York, N. Y. 10022.

Fi rst HARPER roRcHBooKs edi t i on publ i shed 1987

rsBNr 0-06-132076-5 (pbk.)

93 94 95 15 14

GOIITEIITS

Acknowledgements

Introducti on by Vi vi an Gorni ck

Cender Di spl ay

Pi cture Frames

Cender Commerci al s

Rel ati ve Si ze

The Femi ni ne Touch

Functi on Ranki ng

The Fami l y

The Ri tual i zati on of Subordi nati on

Li censed Wi thdrawal

Concl usi on

vi i

t

1 0

24

2A

29

32

3 7

40

84

[l'

AGIIII0WIEIIGEiIEIITS

Apart from a few changes, this monograph first appeared as

vol. 3, no. 2 (F all 1976) of Studies in the Anthropology of

Visuol Communicotion, a

publication of the Society for the

Anthropol ogy of Vi sual Communi cal i on- | am very

grateful

to i ts then edi tor, the l ate Sol Worth, for support i n worki ng out

the ori gi nal edi ti on and for permi ssi on to use i ts

pl ates and

gl ossi es. I am al so

grateful to El sa Vorwerk, managi ng edi tor

of the Ameri can Anthropol ogi cal Associ ati on, for a

great

deal of hel p wi th the ori gi nal l ayout. The sl i des from whi ch

the reproducti ons were made were themsel ves done from the

ori gi nal s by

J

ohn Carey and Lee Ann Draud.

IIUTROTTUGTIOT

byVivian Gornick

The contemporary femi ni st movement, wi th al l i ts cl amor about

the meani ng of the l i ttl e detai l s i n dai l y l i fe, has acted as a ki nd of

el ectri c prod to the thought of many soci al sci enti sts, gi vi ng new

i mpetus and di recti on to thei r work, the very substance of whi ch

i s the observati on of concrete detai l i n soci al l i fe. Because of the

feminists the most ordinary verbal exchange between men and

women now reverberates with new meaning; the most simple

gesture, familiar ritual, taken-for-granted form of address has

become a source of new understanding with regard to relations

between the sexes and the social forces at work behind those

rel ati ons. Operati ng out of

"a

pol i ti cs that ori gi nates wi th one' s

own hurt feel i ngs," the femi ni sts have made vi vi d what the soci al

sci enti sts have al ways known: l t i s i n the detai l s of dai l y exchange

that the discrepancy between actual experience and apparent

exDerience is to be found.

Ervi ng Coffman i s a bri l l i ant soci al sci enti st who has spent hi s l i fe

observi ng soci al behavi or the way a fi ne l i terary cri ti c reads

literature. He does not sacrifice the text to theory, he knows one

readsoutof it ratherthan into it, he never forgets that both the text

and soci ety are al i ve.

At the same time, Coffman's reading of the text is informed by

a pi ece of systemati c thought about soci al behavi or that has been

gathering shape and force over a great many years. He knows that

the detai l s of soci al behavi or are svmptomati c revel ati ons of how

a sense of self is established and reinforced, and that that sense of

self, in turn, both reflects and cements the social institutions upon

whi ch rests a cul ture' s hi erarchi cal structure. Li ke the real l y fi ne

teacher he is, Coffman is always workinS to demonstrate that if

one exami nes the detai l s of soci al l i fe wi th a hi ghl y consci ous eye

one l ear n s- deepl y- who and what one i s i n t he soci al l y

organi zed worl d.

In thi s wonderful l y dense and l i vel y monograph Coffman

turns hi s aftenti on, speci fi cal l y, to the ways i n whi ch men and

women-mai nl y women-are

pi ctured i n adverti sements

(those

hi ghl y mani pul ated representati ons of recogni zabl e scenes from

"real

l i fe"), and specul ates ri chl y on what those ads tel l us about

ourselves; whatthe interplay is between fashioned image and so-

cal l ed natural behavi or; the de8ree to whi ch adverti sements

embody an artificial pose reflecting on perhaps yet another artifi-

ci al pose-that i s, the process by whi ch we come to thi nk of what

we cal l our natural sel ves.

This ouestion of men and women in advertisements is interest-

ing and important, Coffman says, because

"So

deeply does the

mal e-femal e di fference i nform our ceremoni al l i fe that one fi nds

here a very systematic

'opposite

number' arrangement," one that

al l ows us to thi nk profi tabl y about the way i n whi ch sel f-defi ni -

ti on i s gui ded and external l y determi ned.

For Coffman, social situations are settings for ceremonies

whose function is

"to

affirm social arrangements and announce

ul ti mate doctri ne." In the soci al or

publ i c

si tuati on the most

minute behavior has meaning. Cesture, expression, posture re-

veal not only how we feel about ourselves but add up, as well, to

an entire arrangement-a scene-that embodies cultural values.

Within these scenes, Goffman posits, human behaviors_can be

seen as

"di spl ays."

Expl ai ni ng that i n ani mal s a di spl ay i s an

"emotionally

motivated behavior

lthat]

becomes formalized,

provi des

a readi l y readabl e expressi on of

[the

ani mal ' s] si tuati on,

speci fi cal l y hi s i ntent,

[and] thi s...al l ows for the negoti ati on of an

efficient response from and to witnesses of the display," Coffman

goes on to say that, si mi l arl y, i n human bei ngs

"...an

i ndi vi dual ' s

behavi or and appearance i nforms those who wi tness hi m...about

hi s soci al i denti ty, mood, i ntent. ...

[T]hese are di spl ays that

establ i sh the terms of the contact,..for the deal i ngs that are to

ensue between the persons providingthe display and the persons

percei vi ng i t."

But, Coffman adds-and this

"but"

is the heart ofthe mafter-

"The

human use of di spl ays i s compl i cated by the human capac-

i ty for .eframi ng behavi or....

fD]i spl ays

(i n humans) are a symp-

tom, not a portrai t....l t i s not so much the character of an enti ty

that gets expressed..,.

[E]xpressi on

i n the mai n i s not i nsti ncti ve

but soci al l y l earned and soci al l y patterned....

fl ndi vi dual sl

are

learning to be objects that have a character, that express this

cha.acter, and for whom this characterological expressing is only

natural . We are soci al i zed to confi rm our own hvootheses about

our natures....

"

Turni ng then to the speci fi c subj ect of the work i n hand,

Cof f man obser ves:

" What

t he human nat ur e of mal es and

females really consists of then, is a capacity to learn to provide

and to read depi cti ons of mascul i ni ty and femi ni ty and a wi l l i ng-

ness to adhere to a schedule for presenting these pictures, and this

capacity they have by virtue of being persons, not females or

mal es."

It is around this last, wholly persuasive perception that Cendef

Adveltriementi is organized. Advertisements depict for us not

necessari l v how we actual l v behave as men and women but how

we thi nk men and women behave. Thi s depi cti on serves the

soci al purpose of convi nci nS us that thi s i s how men and women

are, or want to be, or should be, not only in relation to themselves

but in relation to each other. They orient men and women to the

idea of men and women acting in concert with each other in the

l arger pl ay or scene or arrangement that i s our soci al l i fe. That

ori entati on accompl i shes the task a soci ety has of maj ntai ni ng an

essential order, an undisturbed on-goingness, regardless of the

actual experi ence of i ts parti ci pants.

ln a crucial passage Coffman argues that in one sense the

job

of the advertiser and the

job

of a society are the same:

"Both

must

transform otherwise opaque goings-on into easily readable

fotm." Otherwise opaque goings-on! A wonderful phrase that

speaks vol umes. What exacti y are the goi ngs-on that are opaque?

They are the murky, muddled efforts of the half-conscious mind,

the confused spirit, the unresolved will to comprehend the nature

of actual experience rather than described experience, felt emo-

tion rather than cued emotion, perceived truth rather than re-

cei ved wi sdom. And the

"wi l l i ngness

to adhere to a schedul e for

presenti ng these pi ctures" i s the i ncl i nati on both of i ndi vi dual s

and ofsocieties to fall back from the conscious struggle to under-

stand ourselves; to learn about ourselves at a remove; to accept as

real an al most whol l y assumed sel f.

viil INTRODUCTIOI{

Speaki ng i n a sense to thi s hi ghl y si gni fi cant i ncl i nati on, Coff-

man remarks-wi th hi s geni us for bri l l i ant anal ogy-that i t i s not

at al l unl i kel y that a fami l y on vacati on mi ght take i ts cues for

what

"having

a good time" is from external sources and might, in

fact, contri ve to l ook and act l i ke the i deaj i zed fami l y-on-vaca-

ti on i n a Coca-Col a ad. By the same token, i t hardl y needs

stressi ng, men and women take thei r cues about,,eender be_

havi or" from the i mage of thdt behavi or thal adverti :i ne throws

back at them, and they contri ve to become the

,,peopl e,,

i n those

ads.

Reflecting on the intimate give-and-take

between how

pho-

l ographed adverl rsements are made, and whal they are made out

of, Coffman concl udes:

"l n

seei ng what pi cture makers can make

of si tuati onal materi ai s one can begi n to see what we oursel ves

mi ght be engaged i n doi ng."

The pictures that Coffman has chosen and arransed for our

perusal i n CenderAdveftl i emenl j

are, l hen, a comme-ntary on the

complicated mafter of

"what

we ourselves might be engaged in

doi n8." That commentary cl earl y demonstrates that whi l e adver-

ti sements appear to be photographi ng

mal e and femal e human

bei ngs what they are actuai l y photographi ng

i s a depi cti on of

mascul i ni ty and femi n i ni ty that i s fi tted or matched i n such a wav

as to make i t functi on soci al l y.

Nowthi s percepti on i s notori gi nal wi th Coffman (as

Coffman

hj msel f woul d be the fi rst to admi ti he i s emi nentl y fai r about

i denti fyi ng hi s sources). One ofthe mai or

poi nts

of concentrati on

i n the femi ni st strategy has been the i mage ofwomen i n adverti s-

i ng. Many femi ni sts have pai d el aborate attenti on to the fri ghten-

i ng uses to whi ch women have been

put

i n ads ei ther as creatures

of embodi ed sexual usage or as thoroughl y mi ndl ess domesti cs

thrown into ecstasy by a waxed floor or depression by an un-

bl eached shi rt. Moreovet the femi ni sts have al so poi nted out the

soci al and pol i ti cal purposes served by adverti sements rei nforc-

i ng the noti on of men as natural l y domi nant and women as

natural l y subordi nate.

What i s ori gi nal wi th Coffman i s the qual i ty of the i nsi ght he

bri ngs to bear on mal e-femal e i mages i n adverti si ng. Most obser-

vati on on thi s subj ect has been of a bl unt and fundamental nature:

ori gi nal spadework, so to speak; di ggi ng up the i ssue. What

Coffman does here

jn

Cender Advertisement5,by virtue of his

penetrati ng

eye and hi s comprehensi ve context i s to contri bute

an observati on so shrewd and subti e i t takes us farther than we

have been before. For a reader al ready fami l i ar wi th the femi ni st

angl e of vi si on trai ned on the i mage of women i n ads thi s, of

course, i s pure pl easure, an unexpected gi ft: the gi ft of renewed

sti mul ati on, thought fi red once more, mental terri tory i ncreased.

Instead of l ooki ng at cl utched detergents and hal f-naked

bodies, Coffman concentrates on hands, eyes, knees; facjal ex-

pressi ons, head postures, rel ati ve si zes; posi ti oni ng and pl aci ng,

head-eye aversi on, fi nger bi ti ng and sucki ng. He al so groups the

pi ctures

so that the bul k of them i l l ustrate i n a si ngl e seri es what

we thi nk of as a natural pose or pi ece

of behavi or for one of the

sexes, and then he has the last two or three

pictures

in the series

show the same pose of behavior with the sexes switched. Be-

tween the fineness ofdetail that receives Coffman,s attention and

the shock value of the switched-sex pictures we experience that

i nner surpri se that precedes deepened percepti on.

Under headi ngs l i ke

"The

Femi ni ne Touch,"

,,Functj on

Rank-

i ng,"

"The

Ri tual i zati on of Su bord i nati on,,,

,,Rel ati ve

Si ze.,, and

"Li censed

Wi thdrawal ," Goffman makes us see such observabl e

phenomena

i n adverti si ng as the fol l owi ng: 1) overwhel mi ngl y a

woman i s tal l er than a man onl y when the man i s her soci al

i nferi or; 2) a woman' s hands are seen

j ust

barel y touchi ng, hol d_

In8 or caresstng-never graspi ng,

mani pul ati ng, or shapi ng; 3)

when a photograph

of men and women

j l j ustrates

an i nstructi on

ot some sort the man i s al ways i nstructi ng

the woman_even i f

the men and women are actual l y chi l dren l that i s, a mal e chi l d

wi l l be i nstructi ng a femal e chi l d!1; 4) when an adverti sement

requi res someone to si t or l i e on a bed or a fl oor that someone i s

al most al ways a chi l d or a woman, hardl y ever a man; 5) when the

head or eye of a man i s averted i t i s onl y i n rel ati on to a soci al .

pol i ti cal ,

or i ntel l ectual superi or, but when the eye or head of a

woman is averted it is always in relation to whatevef man is

pi ctured

wi th her; 6) women are repeatedl y shown mental l v

dri fti ng from the scene wh i l e i n cl ose physi ca I l ouch wi th a mal e,

thei r faces l ost and dreamy,

,,as

though hi s al i veness to the sur_

roundings and his readiness to cope were enough for both of

them" 7) concomi tantl y, women, much more than men, are

pi ctured

atthe ki nd of psychol ogi cal

l oss or remove from a soci al

si tuati on that l eaves one unori ented for acti on

(e.g.,

somethi ng

terri bl e has happened and a woman i s shown wi th her hands ovei

her mouth and her eyes hel pl ess wi th horror).

.

These detai l s are absorbi ng and graphi c, underl i ni ng as they

do a sense of thi ngs that presses

on the al erted mi nd, the recepti ve

r magi ndt i on.

I hey make you know bet t er whal you have

"known"

before; they induce the vigorous nod of the head, the

murmured

"oh

yes," the surpri sed

,,1

hadn,t thousht of that!,,

But Coffman' s maj or contri buri on i n thi s bo;k of

,,depi cted

femininity" (what

Cender Advertisements is really about) is the

conti nuous, ever-deepeni ng connecti on he makes between our

i mage of women and the behavi or of chi l dren. In a shrewd

di scussi on of the chi l d-parent rel ati on he notes that a chi l d,s

behavior

often indicates that

,A

loving protector is standing by in

the wi ngs, al l owi ng not so much fordependency as a coppi ng out

of or rel i ef from, the

' real i ti es,,

that i s, the necessi ti es and con-

strai nts to whi ch adul ts i n soci al si tuati ons are subj ect.,, He then

adds poi ntedl y:

"You

wi l l note that there

j s

an obvj ous pri ce

the

chi l d must pay for bei ng saved from seri ousness.,,

Being saved from seriousnesj. Another wonderful

ohrase that

echoes endlessly. ln series after series of the photographs

shown

here Coffman leads us to the repeated usage in advertisements of

women posed as chi l dren, acti ng l i ke chi l dren, l ooki ne l i ke chi l -

dren: unerl y devoi d of the natural sobri ety whi ch one associ ates

wi th the adul t mi en. Crown women are seen standi nq wi th the

head cocked way over to the si de paral l el

to the shoul der, face_

front, eyes and mouth: smi l i ng; ot the head tucked i nto the

shoulder, face-front, eyes looking up from under lowered lids,

seducti ve-gami n

styl e; or hands twi sted behj nd the back; or the

toes of one foot standing on the toes of the other in a child,s

,Aw

gosh gee" posture;

or arms and l egs fl yi ng off i n al l di recti ons l i ke

a cl own; or hands dug deep i nto the pockets,

the faci al exoressi on

"wicked"

or

"merry";

and on every last face that damned

,,daz-

zl i ng" smi l e.

Underscori ng

these obseryati ons

of women i mased as chi l _

dren i s an extraordi nary di scussi on i n words and

pi ctures

of the

way i n whi ch we percei ve men and women weari ns cl othes i n

adverl i 5pmqnl r. In thi s di s( ussi on Coffman poi nts

oui that what_

ever a man i s weari ng i n an adverti sement he wears seri ousl y,

wnereas whatever a woman is wearing she appears to be trying

on, as though the cl othes were a costume, not the appropri ate

coveri ng of a person

bei ng seri ousl y presented.

l f a man i n an

INTRODUCTION lx

adveni sement i s weari ng a busi ness sui t and carryi ng a bri efcase

we bel i eve that he i s seri ousl y representi ng a busi nessman; i f the

same man is seen wearing shorts and carrying a racquet we

bel i eve, equal l y, that he i s representi ng the same man pl ayi ng

tennis, that we are looking at different aspects ofthe same life, the

one momentarily discarded for the other. However, when we see

a woman weari ng formal or i nformal , busi ness or sports cl othes

we Jeel we are watchi ng a model pl ay-dctj ng.

We cannot bel i eve

in the seriousness of the person

meant to be reoresented

bv the

cl othes the model i s weari ng. We feel we are wdtchi ng someone

at a perpetual

costume bal l , pl ayi nB dt tryi ng on l hi s a; that, not

someone whose cl othes i ndi cate a person seri ousl y present

j n

the

soci al si tuati on bei ng pi ctured.

Coffman's observation is powerful.

One has only to look at an

adverti sement showi ng a woman carryi ng an attache case, or

reading

'The

Wall Strcet

Journal', or wearing a white coat in a

laboratory sefting-the words

,,Forthe

woman with a mind of her

own" scrawl ed across the ad-and then consul t one,s own i n_

sti ncti ve i ncredul i t, to know the truth of what he i s poi nti ng

out.

There comes suddenly to mind the memory of old-time vaude-

villians in black-face-powerless people

,,playing,,

even more

powerl ess peopl e-and

i toccurs thatthese i mages i n adverti si ng

ofwomen pl ayi ng

at bei ng seri ous peopl e are a true mock_uo oi

l i fe: an i mage refl ecti ng an i mage refl ecl i ng an i mage; tri ck

mi rrors, i l l usory effects, traci ngs that resembl e an i dea of human

bei ngs, voi d of real i ntent, substanti ve l i fe....Or perhaps

Coffman

i s sayi ng thi s i 5 real l i fe. That i s, l hi s i s the real i ty of the l i fe we are

l i vi ng out.

The most painful

and perhaps

the most important sentence in

Cender Advertisements

is this:

,Although

the pictures

shown here

cannotbe taken as representati ve of gender behavi or i n real l i fe...

one can probabl y

make a si gni fi cant negati ve statement about

them, namely, that as pictures

they are not perceived

as

peculiar

and unnatural ."

What Erving Coffman shares with contemporarv feminists is

the fel t convi cti on thdt benedth the surfdce of ordi nary soci al

behavi or i nnumerabl e smal l murders ofthe mi nd and spi ri t take

pl ace

dai l y. l nsi de most peopl e, behi nd a soci al l y useful i mage of

the self, there is a sentient being suffocating slowly to death in a

Kafkaesque atmosphere, taken as

,,natural ,,,that

deni es not onl v

the death but the l i ve bei ng as wel l .

Cender Advertisemerts is an act of creative documentation.

Its ai m-l i ke that of a fi ne novel or a sensi ti ve anal ysi s or a l i ve

pi ece

of pol i ti cs-i s

to name and re-name and name yet agai n

"the

thing itself"; to make us see the unnatural in the natur;l in

order that we may rescue the warm Iife trapped inside the frozen

i mase.

EETIDEN DISPTAT

f

Take i t thdt the functi on of ceremony reaches i n two

I di recti ons, the affi rmati on ol basi c soci al arrangemenl s

and the

presentati on

of ul ti mate doctri nes about man and

the worl d. Typi cal l y these cel ebrati ons are performed

ei ther

by persons

acti ng to one another or acti ng i n concert before

a congregati on. So

"soci al

si tuati ons" are i nvol ved-defi ni ne

these si mpl y as physi cal

arenas anywhere wi thi n whi ci

persons present

are in perceptual

range of one another,

subi ect to mutual moni tori ng-the persons

themsel ves bei ng

defi nabl e sol el y on thi s ground

as a

"gatheri ng."

It i s i n soci al si tuati ons, then, that materi al s for cel ebra-

ti ve work must be found, materi al s whi ch can be shaped i nto

a

pal pabl e

representati on of matters not otherwi se packaged

for the eye and the ear and the moment. And found they are.

The di vi si ons and hi erarchi es of soci al structure are deDi cted

mi croecol ogi cal l y, that i s, through the use of smal l scal e

spati al metaphors. Mythi c hi stori c events are pi ayed

through

i n a condensed and i deal i zed versi on. Apparent

i unctures

or

turni ng poi nts

i n l i fe are sol emni zed, as i n chri steni ngs,

graduati on

exerci ses, marri age ceremoni es, and funeral s.

Social relationships are addressed by greetings

and farewells.

Seasonal cycl es are gi ven dramati zed boundari es, Reuni ons

are hel d. Annual vacati ons and, on a l esser scal e, outi ngs on

weekends and eveni ngs are assayed, bri ngi ng i mmersi on i n

i deal setti ngs. Di nners and parti es

are gi ven, becomi ng

occasions for the expenditure of resources at a rate that is

above one' s mundane sel f. Moments of festi vi ty are attached

to the acqui si ti on of new possessi ons.

In al l of these ways, a si tuated soci al fuss i s made over

what mi ght ordi nari l y be hi dden i n extended courses of

acti vi ty and the unformul ated experi ence of thei r

par-

ti ci pants; i n bri ef, the i ndi vi dual i s gi ven

an opportuni ty to

face di rectl y a representati on, a somewhat i coni c expressi on,

a mock-up of what he i s supposed to hol d dear, a

presentati on

of the supposed orderi ng of hi s exi stence.

A si ngl e, fi xed el ement of a ceremony can be cal l ed a

"ri tual ";

the i nterpersonal ki nd can be defi ned as

perfunc-

tory, conven ti onal i zed acts through whi ch one i ndi vi dual

portrays

his regard for another to that other.

f f

l f Dur khei m l eads us t o consi der one sense of t he t er m

I I ritualization, Darwin, in his Espression of Emotion in

Man ond Ani mal s,l eads us, coi nci dental l y, to consi der qui te

another. To paraphrase

Jul i an

Huxl ey (and the ethol ogi cal

posi ti on),

the basi c argument i s that under the pressure

of

natural sel ecti on certai n emoti onal l V moti vated behavi ors

become formal i /ed-i n the sense of becomi ng si mpl i fi ed,

exaggerated, and stereotyped-and loosened from any

speci fi c context of rel easers, and al l thi s so that, i n effect,

there wi l l be more effi ci ent si gnal l i ng, both i nter and

i ntra-speci fi cal l y.r

These behavi ors are

,,di spl ays,' ,

a speci es-

uti l i tari an noti on that i s at the heart of the ethol oei cal

concepti on of communi cati on. Instead of havi ng to pl ay out

an act, the ani mal , i n effect, provi des

a readi l y readabl e

expressi on of hi s si tuati on, speci fi cal l y hi s i ntent, thi s taki ng

the form of a

"ri tual i zati on"

of some porti on

of the act

i tsel f, and thi s i ndi cati on (whether promi se

or threat)

presumabl y

al l ows for the negoti ati on of an effi ci ent

response from, and to, wi tnesses of the di sptay. (l f

Darwi n

l eads here,

John

Dewey, and G. H. Mead are notfar behi nd.)

The ethol ogi cal concern, then, does not take us back from

a ri tual performance

to the soci al structure and ul ti mate

bel i efs i n whi ch the performer

and wi tness are embedded,

but forward i nto the unfol di ng course of soci al l y si tuated

events, Displays thus provide

evidence of the actor's olign-

ment i n a gatheri ng,

the posi ti on he seems prepared

to take

up i n what i s about to happen i n the soci al si tuati on.

Al i gnments tentati vel y or i ndi cati vel y establ i sh the terms of

the contact, the mode or styl e or formul a for the deal i ngs

that are to ensue among the i ndi vi dual s i n the si tuati on. As

suggested, ethol ogi sts tend to use the term communi cati on

here, but that mi ght be l oose tal k. Di spl ays don' t communi -

cate i n the narrow sense of the term; they don' t enunci ate

somethi ng through a l anguage of symbol s openl y establ i shed

and used sol el y for that purpose.

They provi de

evi dence of

ti e actor' s al i gnment i n the si tuati on. And di spl avs are

i mportant i nsofar as al i gnments are.

A versi on of di spl ay for humans woul d go somethi ng l i ke

thi s: Assume al l of an i ndi vi dual ' s behavi or and appearance

i nforms those who wi tness hi m, mi ni mal l y tel l i ng them

somethi ng about hi s soci al i denti ty, about hi s mood, i ntent,

and expectati ons, and about the state of hi s rel ati on to them.

In every cul ture a di sti ncti ve range of thi s i ndi cati ve behavi or

and appearance becomes speci al i zed so as to more routi nel y

and perhaps

more effecti vel y perform

thi s i nformi ng

functi on, the i nformi ng comi ng to be the control l i ng rol e of

the performance,

although often not avowedly so. One can

cal l these i ndi cati ve events di spl ays. As suggested, they

tentati vel y establ i sh the terms of the contact, the mode or

styl e or formul a for the deal i ngs that are to ensue between

the persons provi di ng

the di spl ay and the persons percei vi ng

i t.

Fi nal l y, our speci al concern: l f gender

be defi ned as the

cul tural l y establ i shed correl ates of sex (whether

i n con-

sequence of bi ol ogy or l earni ng), then gender di spl ay refers

to conventi onal i zed portrayal s

of these correl ates.

l l l

What can be sai d about t he st r uct ur e of r i t ual i i ke

I I I di sol avsl

(1) Di spl ays very often have a di al ogi c character of a

statement-repl y ki nd, wi th an expressi on on the part of one

i ndi vi dual cal l i ng forth an expressi on on the part

of another,

the l atter expressi on bei ng understood to be a response to

the first.

These statement-response pai rs can be cl assi fi ed i n an

'Philosophicol

Trcnsoctions of the Royot Society of London,

Seri es B, No. 772, Vol . 251

l Dec-

29, 1966), p. 2SO.

2 GENDERADVERTI SEMENTS

obvi ous way, There are symmetri cal and asymmetri cal pai rs:

mutual fi rst-nami ng i s a symmetri cal

pai r, fi rst-name/si r i s an

asymmetri cal one. Of asymmetri cal

pai rs,

some are dyadi cal -

l y reversi bl e, some not: the

greeti ngs between gust and host,

asymmetri cal i n themsel ves, may be reversed between these

two persons on another occasi on; fi rst-name/ti tl e, on the

other hand, ordi nari l y i s not reversi bl e. Of dyadi cal l y

i rreversi bl e

pai rs

of ri tual s, some pai r parts are excl usi ve,

some not: the ci vi l i an ti tl e a mal e may extend a femal e i s

never extended to hi m; on the other hand, the

"Si r"

a man

recei ves from a subordi nate i n exchange for fi rst-name, he

hi msel f i s l i kel y to extend to h/5 superordi nate i n exchange

for fi rst-name, an i l l ustrati on of the

great chai n of corporate

berng.

Observe that a symmetri cal di spl ay between two i ndi vi d-

ual s can i nvol ve asymmetri es accordi ng to whi ch of the two

i ni ti al l y i ntroduced the usage between them, and whi ch of

the two begi ns hi s part of the mutual di spl ay fi rst on any

occasion of use.

And symmetry (or asymmetry) i tsel f can be mi sl eadi ng.

One must consi der not onl y how two i ndi vi dual s ri tual l y

treat each other, but al so how they separatel y treat, and are

treated by, a common thi rd. Thus the

poi nt about sym-

metri cal

greeti ngs and farewel l s extended between a mal e and

a cl ose femal e fri end i s that he i s verv l i kel v to extend a

di fferent set, al bei t equal l y symmetri cal , to her husband, and

she, si mi l arl y, a

yet di fferent symmetri cal set to hi s wi fe.

Indeed, so deepl y does the mal e-femal e di fference i nform our

ceremoni al l i fe that one fi nds here a verv svstemati c

"opposi te

number" arrangement. For every courtesy,

symmetri cal or asymmetri cal , that a woman shows to al most

anyone, there wi l l be a

paral l el

one-seen to be the same,

yet

di fferent-whi ch her brother or husband shows to the same

person.

(2)

Gi ven that i ndi vi dual s have work to do i n soci al

si tuati ons, the

questi on

ari ses as to how ri tual can accom-

modate to what i s thus otherwi se occurri ng. Two basi c

patterns seem to appear, Fi rst, di spl ay seems to be con-

centrated at begi nni ngs and endi ngs of

purposeful under-

taki ngs, that i s, at

j unctures,

so that, i n effect, the acti vi ty

i tsel f i s not i nterfered wi th.

(Thus

the smal l courtesi es

someti mes

performed i n our soci ety by men to women when

the l atter must undergo what can be defi ned as a sl i ght

change i n physi cal state, as i n

getti ng up, si tti ng down,

enteri ng a room or l eavi ng i t, begi nni ng to smoke or ceasi ng

to, movi ng i ndoors or outdoors, sufferi ng i ncreased tempera-

ture or l ess, and so forth.) Here one mi ght speak of

"bracket

ri tual s." Second, some ri tual s seem desi gned to be conti nued

as a si ngl e note across a stri p of otherwi se i ntended acti vi ty

wi thout di spl aci ng that acti vi ty i tsel f. (Thus the basi c

mi l i tary courtesy of standi ng at attenti on throughout the

course of an encounter wi th a superi or-i n contrast to the

sal ute, thi s l atter cl earl y a bracket ri tual .) One can speak here

of a

"ri tual

transfi x" or

"overl ay."

Observe that by combi n-

i ng these two l ocati ons-brackets and overl ays-one has, for

any stri p of acti vi ty, a schedul e of di spl ays. Al though these

ri tual s wi l l tend to be

percei ved

as col ori ng the whol e of the

scene, i n fact, of course, they onl y occur sel ecti vel y i n i t.

(3) l t i s pl ai n

that i f an i ndi vi dual i s to gi ve and recei ve

what i s consi dered hi s ri tual due i n soci al si tuati ons, then he

must-whether by i ntent or i n effect styl e hi msel f so that

others present can i mmedi atel y know the soci al (and

someti mes the personal ) i denti ty of he who i s to be deal t

wi th; and i n turn he must be abl e to acqui re thi s i nformati on

about those he thus i nforms. Some di sol avs seem to be

speci al i zed for thi s i denti fi catory, earl y-warni ng functi on: i n

the case of gender, hai r styl e, cl othi ng, and tone of voi ce.

(Handwri ti ng si mi l arl y serves i n the si tuati on-l i ke contacts

conducted through the mai l s; name al so so serves, i n addi ti on

to servi ng i n the management of persons who are present

onl y i n reference.) l t can be argued that al though ri tual i zed

behavi or i n soci al sl tuati ons may markedl y change over ti me,

especi al l y i n connecti on wi th pol i ti ci zati on,

i denti fi catory

styl i ngs wi l l be l east subj ect to change.

(4) There i s no doubt that di spl ays can be, and are l i kel y

to be, mul ti vocal or pol ysemi c, i n the sense that more than

one

pi ece of soci al i nformati on may be encoded i n them.

(For exampl e, our terms of address typi cal l y record sex of

reci pi ent and al so properti es of the rel ati onshi p between

speaker and spoken to. So, too, i n occupati onal ti tl es

["agenti ves"].

In the pri nci pal European l anguages, typi cal l y

a mascul i ne form i s the unmarked case; the femi ni ne i s

managed wi th a suffi x whi ch, i n addi ti on, often carri es a

connotati on of i ncompetence, faceti ousness, and i nex-

peri ence.2) Al ong wi th thi s compl i cati on goes

another. Not

onl y does one fi nd that recogni ti on of di fferent statuses can

be encoded i n the same di spl ay, but al so that a hi erarchy of

consi derati ons may be found whi ch are addressed sequenti al -

l y. For exampl e, when awards are gi ven out, a mal e offi ci al

may fi rst gi ve

the medal , di pl oma,

pri ze,

or whatever, and

then shake the hand of the reci pi ent, thus shi fti ng from that

of an organi zati on' s representati ve bestowi ng an offi ci al si gn

of regard on a sol di er, col l eague, fel l ow ci ti zen, etc., to a man

showing regard for another, the shift in action associated

wi th a sharpl y al tered faci al expressi on. Thi s seems ni cel y

confi rmed when the reci Di ent i s a woman. For then the

second di spl ay can be a soci al ki ss. When Admi ral El mo R.

Zumwal t, then chi ef of U.S. naval operati ons, offi ci ated i n

the ceremony i n whi ch Al ene Duerk became the fi rst femal e

admi ral i n the U.S. Navy' s hi story (as

di rector of the Navy

Nurse Corps), he added to what was done by ki ssi ng her ful l

on the ti ps.3 So, too, a femal e harpi st after

j ust

compl eti ng

Gi nastera' s Harp Concerto, and havi ng

j ust

shaken the hand

of the conductor (as woul d a mal e sol oi st), i s free (as a mal e

i s not) to stri ke an addi ti onal note by l eani ng over and gi vi ng

the conductor a ki ss on the cheek. Si mi l arl y, the appl ause she

recei ves wi l l be her due as a musi ci an, but the fl owers that

are brought onstage a moment after speak to somethi ng that

woul d not be sooken to i n a mal e sol oi st. And the reverse

sequence i s possi bl e. I have seen a wel l -bred father rai se hi s

hat on first meeting his daughter after a two-year absence,

then bend and ki ss her.

(The

hat-rai se denoted the rel ati on-

shi p between the sexes-presumabl y

"any

l ady" woul d have

i nduced i t-the ki ss, the rel ati on between ki n.)

(5) Di spl ays vary qui te consi derabl y i n the degree of thei r

formal i zati on. Some, l i ke sal utes, are speci fi ed as to form and

occasi on of occurrence, and fai l ure to so behave can l ead to

speci fi c sancti ons; others are so much taken for granted that

i t awai ts a student of some ki nd to exDl i cate what evervone

2See

t he t horough t reat ment of

"f emi ni zers"

i n Conners (1971).

3lntenational

Hercld Tribune,

lune

3-4,1972,

knows (but not consci ousl y), and fai l ure to perform l eads to

nothi ng more than di ffuse unease and a search for speakabl e

reasons to be i l l -tempered wi th the offender.

(6)

The ki nd of di spl ays I wi l l be concerned wi th gender

di spl ays-have a rel ated featur: many appear to be opti onal .a

In the case, for exampl e, of mal e courtesi es, often a

parti cul ar di spl ay need not be i ni ti ated; i f i ni ti ated, i t need

not be accepted, but can be pol i tel y decl i ned. Fi nal l y, when

fai l ure to perform occurs, i rony, nudgi ng, and

j oki ng

compl ai nt, el c., can resul t-someti mes more as an

opportuni ty for a sal l y than as a means of soci al control .

Correl ated wi th thi s basi s of l ooseness i s another: for each

di spl ay there i s l i kel y to be a set of functi onal equi val ents

wherewi th sornethi ng of the di spl ay' s effect can be accom-

pl i shed by al ternati ve ni ceti es. At work, too, i s the very

process

of ri tual i zati on. A reci pi ent who decl i nes an

i nci pi ent

gesture of deference has wai ted unti l the i ntendi ng

gi ver has shown hi s desi re to perform i t; the more the l atter

can come to count on thi s forecl osure of hi s move, the more

hi s show of i ntent can i tsel f come to di spl ace the unfol ded

form.

(7) Ordi nari l y di spl ays do not i n fact provi de a repre-

sentati on i n the round of a speci fi c soci al rel ati onshi p but

rather of broad groupi ngs of them. For exampl e, a soci al ki ss

may be empl oyed by ki n-rel ated persons or cross-sex fri ends,

and the detai l s of the behavi or i tsel f may not i nform as to

whi ch rel atl onshi p i s bei ng cel ebrated. Si mi l arl y, precedence

through a door i s avai l abl e to mark organi zati onal rank, but

the same i ndul gence i s accorded

guests of an establ i shment,

the dependentl y

young,

the aged and i nfi rm, i ndeed, those of

unquesti onabl y strong soci al posi ti on and those (by i nversi on

courtesy) of unquesti onabl y weak posi ti on. A pi cture, then,

of the rel ati onshi p between any two persons can hardl y be

obtai ned through an exami nati on of the di spl ays they extend

each other on any one type of occasi on; one woul d have to

assembl e these ni ceti es across al l the mutual l y i denti fyi ng

types of contacts that the

pai r has.

There i s a l oose geari ng, then, between soci al structures

and what

goes

on i n parti cul ar occasi ons of ri tual expressi on.

Thi s can further be seen by exami ni ng the abstract ordi nal

format whi ch i s commonl y

generated wi thi n soci al si tuati ons.

Parti ci pants, for exampl e, are often di spl ayed i n rankabl e

order wi th respect to some vi si bl e property l ooks, hei ght,

el evati on, cl oseness to the center, el aborateness of costume,

temporal

precedence, and 50 forth and the compari sons are

somehow taken as a remi nder of di fferenti al soci al

posi ti on.

the di fferences i n soci al di stance between vari ous posi ti ons

and the speci fi c character of the posi ti ons bei ng l ost from

vi ew. Thus, the basi c forms of deference provi de a

pecul i arl y

l i mi ted versi on of the soci al uni verse, tel l i ng us more,

perhaps, about the speci al depi cti ve resources of soci al

si tuati ons than about the structures

presumabl y expressed

therebY.

(8) Peopl e, unl i ke other ani mal s, can be qui te consci ous

of the di spl ays they empl oy and are abl e to perform many of

them by desi gn i n contexts of thei r own choosi ng. Thus

i nstead of merel y

"di spl aci ng"

an act (i n l he sense descri bed

" As

Zi mmer man and Wes t ( 1977) r emi nd me, t he

j ndj v i dual

has

( and seeks) ver y l i t t l e opt i on r egar di ng i dent i f i cat i on of own sex cl ass.

Of t n, however , t her e wi l l be choi ce as t o whi ch compl ement of

di spl ays i s empl oyed t o ensur e gendr pl acement .

GENDER DISPLAY 3

by eti ol ogi sts), the human actor may wai t unti l he i s out of

the di rect l i ne of si ght of a

putati ve reci pi ent, and then

engage in a

portrayal of attitude to him that is only then safe

to perform, the

performance done for the benefit of the

performer hi msel f or thi rd

parti es. In turn, th reci pi ent of

such a display (or rather the target of it) may actively

collaborate, fostering the impression that the act has escaped

hi m even though i t hasn' t-and someti mes evi dental l y so.

(There

i s the

paradox,

then, that what i s done for reveal ment

can be parti al l y conceal ed.) More i mportant, once a di spl ay

becomes wel l establ i shed i n a parti cul ar sequence of acti ons,

a section of the sequence can be lifted out of its original

context,

parenthesi zed, and used i n a quotati ve way, a

postural resource for mi mi cry, mockery, i rony, teasi ng, and

other sporti ve i ntents, i ncl udi ng, very commonl y, the depi c-

ti on of make-bel i eve scenes i n adverti sements. Here styl i za-

tion itself becomes an obiect of attention, the actor

provi di ng a comment on thi 5 process i n the very act through

whi ch he unseri ousl y real i zes i t. What was a ri tual becomes

i tsel f ri tual i zed, a transformati on of what i s al ready a

transformati on, a

"hyper-ri tual i zati on."

Thus, the human use

of di spl ays i s compl i cated by the human capaci ty for

reframi ng behavi or.

In sum, then, how a rel ati onshi p i s portrayed through

ri tual can

provi de

an i mbal anced, even di storted, vi ew of the

rel ati onshi p i tsel f. When thi s fact i s seen i n the l i ght of

another, namel y, that di spl ays tend to be schedul ed accom-

modati vel y duri ng an acti vi ty so as not to i nterfere wi th i ts

executi on, i t becomes even more cl ear that the versi on ri tual

gi ves us of soci al real i ty i s onl y that not a pi cture of the way

thi ngs are but a passi ng exhortati ve

Sui de

to percepti on.

l \ /

Di spl ays are

part of what we thi nk of as

"erpressi ve

I Y behavi or," and as such tend to be conveyed and

recei ved as i f they were somehow natural , deri vi ng, l i ke

temperature and

pul se, from the way

peopl e are and needful ,

therefore, of no soci al or hi stori cal anal ysi s. But, of course,

ri tual i zed expressi ons are as needful of hi stori cal understand-

i ng as i s the Ford car. Gi ven the expressi ve practi ces we

empl oy, one may ask: Where do these di spl ays come from?

l f, i n

parti cul ar, there are behavi oral styl es-codi ngs that

di sti ngui sh the way men and women

parti ci pate i n soci al

si tuati ons, l hen l he

questi on shoul d be put concerni ng the

ori gi ns and sources of these styl es. The materi al s and

i ngredi ents can come di rectl y from the resources avai l abl e i n

parti cul ar soci al setti ngs, but that sti l l l eaves open the

questi on

of where the formul ati ng of these i ngredi ents, thei r

styling, comes frcm.

The most

promi nent account of the ori gi ns of our

Sender

di spl ays i s, of course, the bi ol ogi cal . Gender i s assumed to be

an extensi on of our ani mal natures, and

j ust

as ani mal s

express thei r sex, so does man: i nnate el ements are sai d to

account for the behavior in both cases. And indeed, the

means bv whi ch we i ni ti al l y establ i sh an i ndi vi dual i n one of

the two sex cl asses and confi rm thi s l ocati on i n i ts l ater

years

can be and are used as a means of pl acement

i n the manage-

ment of domesti c ani mal s. However, al though the si gns for

establ i shi ng

pl acement are expressi ve of matters bi ol ogi cal ,

why we shoul d thi nk of these matters as essenti al and central

i s a cul tural matter. More i mportant, where behavi oral

gender

4 GENDEBADVERTI SEMENTS

di spl ay does draw on ani mal l i fe, i t seems to do so not, or

not merel y, i n a di rect evol uti onary sense but as a source of

i magery-a cul tural resource, The ani mal ki ngdom-or at l east

certai n sel ect

parts of i t provi des us (l argue) wi th mi meti c

model s for gender di spl ay, not necessari l y

phyl ogeneti c ones.

Thus, i n Western soci ety, the dog has served us as an ul ti mate

model of fawni ng, of bri stl i ng, and (wi th bari ng of fangs) of

threateni ng; the horse a model , to be sure, of physi cal

strength, but of l i ttl e that i s i nterpersonal and i nteracti onal .5

Once one sees that ani mal l i fe, and l ore concerni ng that

l i fe,

provi des

a cul tural source of i magery for gender di spl ay,

the way i s open to exami ne other sources of di spl ay i magery,

but now model s for mi mi cry that are cl oser to home. Of

consi derabl e si gni fi cance, for exampl e, i s the compl ex as-

soci ated wi th European court l i fe and the doctri nes of the

gentl eman, especi al l y as these came to be i ncorporated (and

modi fi ed) i n mi l i tary eti quette. Al though the force of thi s

styl e i s perhaps decl i ni ng, i t was, I thi nk, of very real

i mportance unti l the second Worl d War, especi al l y i n Bri ti sh

i nfl uenced countri es and especi al l y, of course, i n deal i ngs

between mal es. For exampl e, the standi ng-at-attenti on pos-

ture as a means of expressi ng bei ng on cal l , the

"Si r"

response, and even the salute, became part

of the deference

styl e far beyond scenes from mi l i tary l i fe.

For our purposes, there i s a source ofdi spl ay much more

rel evant than ani mal l ore or mi l i tary tradi ti on, a source cl oser

to home, a source, i ndeed, ri ght i n the home; the parent-

chi l d r el at i onshi D.

The parent-chi l d

compl ex-taken i n

j ts

i deal mi ddl e-

cl ass versi on has some verv sDeci al features when

consi dered as a source of behavi oral i magery. Fi rst, most

persons end up havi ng been chl l dren cared for by parents

and/or el der si bs, and as parents (or el der si bs) i n the reverse

posi ti on. So both sexes experi ence both rol es a sex-free

resource.

(The person pl ayi ng the rol e opposi te the chi l d i s a

mother or ol der si ster as much or morei than a father or el der

brother. Hal f of those i n the chi l d rol d wi l l be mal e, and the

housewi fe rol e, the one we used to thi hk was i deal l y sui tabl e

for femal es, contai ns l ol s of

parental el ements.) Second,

gi ven

i nheri tance and resi dence

patterhs, parents are the onl y

authori ty i n our soci ety that can ri ghtl y be sai d to be both

temporary and exerted

"i n

the best i nterests" of those

subordi nated thereby. To speak here at l east i n our Western

soci ety-of the chi l d gi vi ng somethi ng of equi val ence i n

exchange for the reari ng that he gets i s l udi crous. There i s no

appreci abl e qui d pro quo. Bal ance l i es el sewhere. What i s

recei ved i n one

generati on

i s

gi ven i n the next. l t shoul d be

added that thi s i mportant unsel fseeki ng possi bi l i ty has been

sAn

i mport ant work here, of course, i s Darwi n' s Expressi on of

Emotions in Mon ond Animols. In this treatise a direct parallel is

drawn, in words and pictures,

between a few gestures of a few

ani mal s-gest ures expt essi ng, f or exampl e, domi nance, appeasement ,

fear-and the same expressions as portrayed by actors. This study,

recent l y and ri ght l y resurrect ed as a cl assi c i n et hol ogy (f or i ndeed, i t

i s i n t hi s book t h. t di spl ays are f i 6t st udi ed i n det ai l i n everyt hi ng but

name), i s general l y t aken as an el uci dat i on of our ani mal nat ures and

t he expressi ons we consequent l y share wi t h t hem. Now t he book i s

al so f unct i oni ng as a source i n i t s own ri ght of cul t ural bel i ef s

concerni ng t he charact er and ori gi ns of al i gnment expressi ons.

much ngl ected by students of soci ety. The establ i shed

i magery i s economi c and Hobbesi an, turni ng on the noti on of

soci al exchange, and the newer voi ces have been concerned

to show how parental authori ty can be mi s8ui ded, oppres-

si ve, and i neffecti ve.

Now I want to argue that parent-chi l d deal i ngs carry

speci al val ue as a means of ori enti ng the student to the

si gni fi cance of soci al si tuati ons as a uni t of soci al organi za-

ti on. For a

great deal of what a chi l d i s pri vi l eged to do and a

great deal of what he must suffer hi s parents doi ng on hi s

behal f pertai ns to how adul ts i n our soci ety come to manage

themsel ves i n soci al si tuati ons. Surpri si ngl y the key i ssue

becomes this: llhot mode of handling ourselves do we

employ in social situqtions os our meons of demonstrating

respectful orientotion to them

qnd

of mqintlining gulrded-

ness within them?

It mi ght be useful , then, to outl i ne schemati cal l y the i deal

mi ddl e-cl ass parent-chi l d rel ati onshi p, l i mi ti ng thi s to what

can occur when a chi l d and

parent

are

present

i n the same

soci al si tuati on.

It seems to be assumed that the chi l d comes to a soci al

si tuati on wi th al l i ts

"basi c"

needs sati sfi ed and/or

provi ded

for, and that thre i s no good reason why he hi msel f shoul d

be pl anni ng and thi nki ng very far i nto the future. l t i s as

though the chi l d were on hol i day.

There i s what mi ght be cal l ed ori entati on l i cense. The

chi l d i s tol erated i n hi s dri fti ng from the si tuati on i nto

aways, fugues, brown studi es, and the l i ke. There i s l i cense to

fl ood out, as i n di ssol vi ng i nto tears, capsi zi ng i nto l aughter,

bursti ng i nto gl ee, and the l i ke.

Rel ated to thi s l i cense i s another, namel y, the use of

patentl y i neffecti v means to effect an end, the means

expressi ng a desi re to escape, cope, etc., but not possi bl y

achi evi ng i ts end. One exampl e i s the chi l d' s hi di ng i n or

behi nd parents,

or (i n i ts more attenuated form) behi nd hi s

own hand, thereby cutti ng hi s eyes off from any threat but

not the part

of hi m that i s threatened. Another i s

"pum-

mel i ng," the ki nd of attack whi ch i s a hal f-seri ous

j oke,

a use

of consi derabl e force but agai nst an adversary that one

knows to be impervious to such an effort, so that what starts

wi th an i nstrumental effort ends up an admi ttedl y defeated

gesture. l n al l of thi s one has ni ce exampl es of ri tual i zati on i n

the cl assi cal ethol ogi cal sense. And an anal ysi s of what i t i s to

act chi l di shl y.

Next, protecti ve i ntercessi on by parents. Hi gh thi ngs,

i ntri cate thi ngs, heavy thi ngs, are obtai ned for the chi l d.

Dangerous thi ngs chemi cal , el ectri cal , mechani cal *are kept

from hi m. Breakabl e thi ngs are managed for hi m. Contacts

wi th the adul t worl d are medi ated, provi di ng a buffer

between the chi l d and surroundi ng persons. Adul ts who are

present general l y

modul ate tal k that must deal wi th harsh

thi ngs of thi s worl d: di scussi on of busi ness, money, and sex

i s censored; cursi ng i s i nhi bi ted;gossi p di l uted.

There are i ndul gence pri ori ti s: precedence through doors

and onto l i fe rafts i s

gi ven the chi l d; i f there are sweets to

di stri bute, he gets them fi rst.

There i s the noti on of the erasabi l i ty of offense. Havi ng

done somethi ng wrong, the chi l d merel y cri es and otherwi se

shows contrition, after which he can begin afresh as though

the sl ate had been washed cl ean. Hi s i mmedi ate emoti onal

response to bei ng cal l ed to task need onl y be ful l enough and

i t wi l l be taken as fi nal payment for the del i ct. He can al so

assume that l ove wi l l not be di sconti nued because of what he

has done, provi di ng

onl y that he shows how broken up he i s

because of doi ng i t.

There i s an obvi ous general i zati on behi nd al l these forms

of l i cense and pri vi l ege.

A l ovi ng protector

i s standi ng by i n

the wi ngs, al l owi ng not so much for dependency as a coppi ng

out of, or rel i ef from, the

"real i ti es,"

that i s, the necessi ti es

and constrai nts to whi ch adul ts i n soci al si tuati ons are

subj ect. In the deepest sense, then, mi ddl e-cl ass chi l dren are

not engaged i n adi usti ng to and adapti ng to soci al si tuati ons,

but i n practi ci ng,

tryi ng out, or pl ayi ng

at these efforts.

Real i ty for them i s deepl y forgi vi ng.

Note, i f a chi l d i s to be abl e to cal l upon these vari ous

rel i efs from real i ti es, then, of course, he must stay wi thi n

range of a di stress cry, or wi thi n vi ew scamper-back di s-

tance. And, of course, i n al l of thi s, parents

are provi ded

scenes i n whi ch they can act out thei r

parnthood.

You wi l l note that there i s an obvi ous ori ce that the chi l d

must pay

for bei ng saved from seri ousness.

He i s subj ected to control by physi cal

fi at and to

commands servi ng as a l i vel y remi nder thereof: forced

rescues from oncomi ng traffi c and from potenti al

fal l s;

forced care, as when hi s coat i s buttoned and mi ttens

pul l ed

on agai nst hi s protest. In general ,

the chi l d' s doi ngs are

unceremoni ousl y i nterrupted under warrant of ensuri ng that

they are executed safely.

He i s subj ected to vari ous forms of nonperson treatmenL

He i s tal ked past

and tal ked about as though absent. Gestures

of affecti on and attenti on are

performed

"di rectl y,"

wi thout

engagi ng hi m i n verbal i nteracti on through the same acts.

Teasi ng and taunti ng occur, deal i ngs whi ch start out i n-

vol vi ng the chi l d as a coparti ci pant i n tal k and end up

treati ng hi m merel y as a target of attenti on.

Hi s i nward thoughts, feel i ngs, and recol l ecti ons are not

treated as though he had i nformati onal ri ghts i n thei r

di scl osure. He can be queri ed

on contact about hi s desi res

and i ntent, hi s aches and

pai ns, hi s resentments and

grati tude, i n short, hi s subj ecti ve si tuati on, but he cannot go

vry far i n reci procati ng thi s sympatheti c curi osi ty wi thout

bei ng thought i ntrusi ve.

Fi nal l y, the chi l d' s ti me and terri tory may be seen as

expendabl e. He may be sent on errands or to fetch somethi ng

i n spi te of what he i s doi ngat the ti me; he may be caused to

give up territorial prerogatives because of the needs of adults.

Now note that an i mDortant feature of the chi l d' s

si tuati on i n l i fe i s that the way hi s parents i nteract wi th hi m

tends to be empl oyed to hi m by other adul ts al so, extendi ng

to nonparental ki nsmen, acquai nted nonki n, and even to

adul ts wi th whom he i s unacquai nted. (l t i s as though the

worl d were i n the mi l i tary uni form of one army, and al l

adul ts were i ts offi cers.) Thus a chi l d i n patent need provi des

an unacquai nted adul t a ri ght and even an obl i gati on to offer

hel p, provi di ng onl y that no other cl ose adul t seems to be i n

charge.

Gi ven thi s parent-chi l d compl ex as a common fund of

experi ence, i t seems we draw on i t i n a fundamental way i n

adul t soci al gatheri ngs. The i nvocati on through ri tual i sti c

expressi on of thi s hi erarchi cal compl ex seems to cast a spate

of face-to-face interaction in what is taken as no-contest

terms, warmed by a touch of rel atedness; i n short, beni gn

GENDER OI SPLAY 5

cont rol . The superordi nat e gi ves somet hi ng grat i s out of

support i ve i dent i f i cat i on, and t he subordi nat e responds wi t h

an out ri ght di spl ay of grat i t ude, and i f not t hat , t hen at l east

an i mpl i ed submi ssi on t o t he rel at i onshi p and t he def i ni t i on

of t he si t uat i on i t sust ai ns.

One afternoon an officer was given a call for illegal parking

in a

commercial area well off his sector. He was fairly new in the

di st ri ct , and i t t ook hi m awhi l e t o f i nd t he address. When he

affived he saw a car parked

in an obviously dangerous and illegal

manner at t he corner of a smal l st reet . He t ook out hi s t i cket book

and wrot e i t up. As he was pl aci ng

t he t i cket on t he car, a man

came out of the store on the corner. He approached and asked

whether the officer had come in ansver to his call. When the

pat rol man

sai d t hat he had, t he man repl i ed t hat t he car whi ch had

been bot heri ng hi m had al ready l ef t and he hoped t he pat rol man

was not going

to tag his car.

"Hey,

l'm sorry, pol

but it,s already

"l

expect ed Of f i cer Reno, he' s usual l y on 6515 car. I ' d

appreci at e i t , Of f i cer, i f next t i me you

woul d st op i n bef ore

you

wri t e t hem up. " The pat rol man was sl i ght l y conf used. . . .

He sai d pol i t e, y

and f rankl y,

"Mi st er,

how woul d i r l ook i f I

went into every store before I wrote up a ticket and asked if it was

al l ri ght ? What woul d peopl e

t hi nk I was doi ng?" The man

shrugged hi s shoul ders and smi l ed.

"You' re

ri ght , son, O. K. , f orget

i t , Li st en st op i n somet i me i f I can hel p you wi t h somet hi ng. " He

pat t ed

t he

pat rol man

on t he shoul der and ret urned t o hi s busi ness

I

Rubi nst ei n 197 3t 1 61

-1

62] .

Or t he subordi nat e i ni t i at es a si gn of hel pl essness and need,

and t he superordi nat e responds wi t h a vol unt eered servi ce. A

Time magazine story on female police might be cited as an

i l l ustrati on:

Those

Ipol i cewomen]

who arc there al ready have

provi ded

a

devastati ng new weapon to the pol i ce cri me-fi ghti ng arsenal , one

that has hel ped women to get thei r men for centuri es. l t worked

wel l for di mi nuti ve Patrol woman l na SheDerd after she col l ared a

muscul ar shopl i fter i n Mi ami l ast December and di scovered that

there were no other cops-or even a tel ephone-around, Unabl e to

summon hel p, she burst i nto tears.

"l f

I don' t bri ng you

i n, l ' l l

l ose my

i ob,"

she sobbed to her pri soner, who chi val rousl y

accompani ed her unti l a squad car coul d be found.d

It turns out, then, that i n our soci ety whenever a mal e has

deal i ngs wi th a femal e or a subordi nate mal e (especi al l y

a

younger one), some mi ti gati on of potenti al

di stance,

coerci on, and hosti l i ty i s qui te l i kel y to be i nduced by

appl i cati on of the parent-chi l d

compl ex. Whi ch i mpl i es that,

ri tual l y speaki ng, femal es are equi val ent to subordi nate mal es

and both are equi val ent to chi l dren. Observe that however

di stasteful and humi l i ati ng l essers may fi nd these gentl e

prerogatives

to be, they must give second thought to openly

expressi ng di spl easure, for whosoever extends beni gn concern

i s free to qui ckl y change hi s tack and show the other si de of

hi s oower.

v I fJli#.'"'J"",:":',jf J:"'"T ;ff l#;':iJil:,ffi';

for the student to take soci al si tuati ons very seri ousl y as one

natural vantage poi nt from whi ch to vi ew al l of soci al l i fe.

After al l , i t i s i n soci al si tuati ons that i ndi vi dual s can

communi cate i n the ful l est sense of the term, and i t i s onl y i n

them that i ndi vi dual s can physi cal l y

coerce one another,

assaul t one another, i nteract sexual l y, i mportune on another

6Ti me, May

1, 1972, p. 60; I l eav e unc ons i der ed t he r ot eof s uc h

tales in t/re's fashioning of stories.

l- 6 GENOERADVERTI SEMENI S

gestural l y, gi ve physi cal comfort, and so forth. l vl oreover, i t i s

i n soci al si tuati ons that most of the worl d' s work gts done.

Understandabl y, i n al l soci eti es modes of adaptati on are

found, i ncl udi ng systems of normati ve constrai nt, for

managi ng the ri sks and opportuni ti es speci fi c to soci al

si tuati ons.

Our i mmedi ate i nterest i n soci al si tuati ons was that i t i s

mai nl y i n such contexts that i ndi vi dual s can use thei r faces

and bodi es, as wel l as smal l materi al s at hand to engage i n

soci al

portrai ture, l t i s here i n these smal l , l ocal

pl aces that

they can arrange themsel ves m i croecol ogi cal l y to depi ct what

i s taken as thei r

pl ace i n the wi der soci al frame, al l owi ng

them, i n turn, to cel ebrate what has been depi cted. l t i s here,

i n soci al si tuati ons, that the i ndi vi dual can si gni fy what he

takes to be hi s soci al i denti ty and here i ndi cate hi s feel i ngs

and i ntent-al l of whi ch i nformati on the others i n the

gatheri ng wi l l need i n order to manage thei r own courses of

acti on-whi ch knowl edgeabi l i ty he i n turn must count on i n

carryi ng out hi s own dsi gns.

Now i t seems to me that any form of soci al i zati on whi ch

i n effect addresses i tsel f to soci al si tuati ons as such, that i s,

to the resources ordi nari l y avai l abl e i n any soci al si tuati on

whatsoever, wi l l have a very powerful effect upon soci al l i fe.

In any

parti cul ar socl al

gatheri ng at any parti cul ar moment,

the effect of thi s soci al i zati on may be sl i ght-no more

consequence, say, than to modi fy the styl e i n whi ch matters

at hand

proceed. (After al l , whether you l i ght your own

ci garette or have i t l i t for you, you can sti l l get l ung cancer.

And whether your

j ob

termi nati on i ntervi ew i s conducted

wi th del i cacy or abruptness,

you' ve sti l l l ost your

i ob.)

However, routi nel y the

questi on i s that of whose opi ni on i s

voi ced most frequentl y and most forci bl y, who makes the

mi nor ongoi ng deci si ons apparentl y requi red for the co-

ordi nati on of any

i oi nt

acti vi ty, and whose

passi ng concerns

are gi ven the most wei ghL And however tri vi al some of these

l i ttl e

gai ns and l osses may appear to be, by summi ng them al l

up across al l the soci al si tuati ons i n whi ch they occur, one

can see thai thei r total effect i s enormous. The expressi on of

subordi nati on and domi nati on through thi s swarm of si tua-

ti onal means i s more than a mere traci ng or symbol or

ri tual i sti c affi rmati on of the soci al hi erarchy. These expres-

si ons consi derabl y consti tute the hi erarchy; they are the

shadow ond the substance.T

And here gender styl es

qual i fy. For these behavi oral styl es

can be empl oyed i n any soci al si tuati on, and there recei ve

thei r smal l due. When mommi es and daddi es deci de on what

to teach thei r l i ttl e

Johnnys

and Marys, they make exactl y

the ri ght choi ce; they act i n effect wi th much more

soci ol ogi cal sophi sti cati on than they ought to have

assumi ng, of course, that the worl d as we have known i t i s

what thev want to rDroduce.

And behavi oral styl e i tsel f? Not very styl i sh. A means of

maki ng assumpti ons about l i fe pal pabl e i n soci ai si tuati ons.

At the same ti me, a choreography through whi ch parti ci pants

?A

recent suggest i on al ong t hi s l j ne can be f ound i n t he ef f ort t o

speci f y i n det ai l t he di f f erence bet wen col l ege men and women i n

regard t o sequenci ng i n cross-sexed conversat i on. See Zi mmerman and

West ( 1975) , Fi shman ( 1975) , and west and zi mmer man ( 1975) . The

l ast di scusses some si mi l ari t i es bet ween parent -chi l d and adul t

mal e-f emal e conversat i onal

pract i ces.

present

thei r al i gnments to si tuated acti vi ti es i n progress.

And the styl i ngs themsel ves consi st of those arrangments of

the human form and those el aborati ons of human acti on that

can be di spl ayed across many soci al setti ngs, i n each case

drawi ng on l ocal resources to tel l stori es of vry wi de appeal ,

Vl I fi::; l';;ii: il:J*T, *"r rishes ,ive in the sea

because they cannot breathe on l and, and that we l i ve on

l and because we cannot breathe i n the sea. Thi s

proxi mate,

everyday account can be spel l ed out i n ever i ncreasi ng

physi ol ogi cal detai l , and excepti onal cases and ci rcumstances

uncovered, but the

general answer wi l l ordi nari l y suffi ce,

namel y, an appeal to the nature of the beast, to the gi vens

and condi ti ons of hi s exi stence, and a gui l el ess use of the

term

"because."

Note, i n thi s happy bi t of fol k wi sdom-as

sound and sci enti fi c surel y as i t needs to be-the l and and sea

can be taken as there

pri or

to fi shes and men, and

not contrary to

genesi s-put there so that fi shes and men,

when they arri ved, woul d fi nd a sui tabl e pl ac awai ti ng them.

Thi s l esson about the men and the fi shes contai ns, I thi nk,

the essence of our most common and most basi c way of

thi nki ng about oursel ves: an accounti ng of what occurs by an

appeal to our

"natures,"

an appeal to the very condi tl ons of

our bei ng. Note, we can use thi s formul a both for categori es

of persons and for parti cul ar i ndi vi dual s.

Just

as we account

for the fact that a man wal ks upri ght by an appeal to hi s

nature, so we can account for why a parti cul ar amputee

doesn' t by an appeal to hi s parti cul ar condi ti ons of bei ng,

It i s, of course, hardl y possi bl e to i magi ne a soci ety whose

members do not routi nel y read from what i s avai l abl e to the

senses to somet[]i ng l arger, di stal , or hi dden, Survi val i s

unthi nkabl e wi thout i t. Correspondi ngl y, there i s a very deep

bel i ef i n our soci ety, as presumabl y there i s i n others, that an

obj ect produces si gns that are i nformi ng about i t. Obi ects are

thought to structure the envi ronment i mmedi atel y around

themsel ves; they cast a shadow, heat up the surround, strew

i ndi cati ons, l eave an i mpri nt; they i mpress a part pi cture of

themsel ves, a

portrai t

that i s uni ntended and not dependent

on bi ng attended,

yet, of course, i nformi ng nonethel ess to

whomsoever i s properl y pl aced, trai ned, and i ncl i ned.

Presumabl y thi s i ndi cati ng i s done i n a mal l eabl e surround of

some ki nd-a fi el d for i ndi cati ons the actual perturbati ons

i n whi ch i s the si gn. Presumabl y one deal s here wi th

"natural

i ndexi cal si gns," someti mes havi ng

"i coni c"

features. l n any

case, thi s sort of i ndi cati ng i s to be seen nei ther as physi cal

i nstrumental acti on i n the ful l esl sense, nor a5 communi ca-

ti on as such, but somethi ng el se, a ki nd of by-producti on, an

overfl owi ng, a tel l -tal e soi l i ng of the envi ronment wherever

the obj ect has been. Al though these si gns are l i kel y to be

di sti nct from, or onl y a part of, the obj ect about whi ch they

provi de i nformati on, i t i s thei r confi gurati on whi ch counts,

and the ul ti mate source of thi s, i t i s fel t, i s the obi ect i tsel f i n

some i ndependence of the

parti cul ar fi el d i n whi ch the

expressi on happens to occur. Thus we take si gn producti on

to be si tuati onal l y phrased but not si tuati onal l y determi ned.

The natural i ndexi cal si gns gi ven off by obj ects we cal l

ani mal

(i ncl udi ng,

and

pri nci pal l y, man) are often cal l ed

"expressi ons,"

but i n the sense of that trm hre i mpl i ed, our

i magery sti l l al l ows that a materi al process i s i nvol ved, not

conventi onal symbol i c communi cati on. We tend to bel i eve

that these speci al obj ects not onl y gi ve off natural si gns, but

do so more than do other obj ects. l ndeed, the emoti ons, i n

associ ati on wi th vari ous bodi l y organs through whi ch

emoti ons most markedl y appear, are consi dered veri tabl e

engi nes of expressi on. As a corol l ary, we assume that among

humans a very wi de range of attri butes are expressi bl e:

i ntent, feel i ng, rel ati onshi p, i nformati on state, heal th, soci al

cl ass, etc. Lore and advi ce concerni ng these si gns, i ncl udi ng

how to fake them and how to see behind fakeries, constitute

a ki nd of fol k sci ence. Al l of these bel i efs regardi ng man,

taken together, can be referred to as the doctrine of natural

expressi on.

It i s

general l y bel i eved that al though si gns can be read for

what i s merel y momentari l y or i nci dental l y true of the obi ect

produci ng them-as, say, when an el evated temperature

i ndi cates a fever-we routi nel y seek another ki nd of i nforma-

ti on al so, namel y, i nformati on about those of an obj ect' s

properties that are felt ta be

perduring,

overoll, and

structurolly bosic, in short, information about its character or

"essenti al

nature,"

(The same sort of i nformati on i s sought

about cl asses of obi ecs.) We do so for many reasons, and i n

so doi ng

presume that obi ecs (and cl asses of obj ects) have

natures i ndependent of the

parti cul ar

i nterest that mi ght

arouse our concern. Si gns vi ewed i n thi s l i ght, I wi l l cal l

"essenti al ,"

and the bel i ef that they exi st and can be read

and that i ndi vi dual s gi ve thm off i s

part

of the doctri ne of

natural expressi on. Note agai n, that al though some of these

attributes, such as passing mood,

particular

intent, etc., are

not themselves taken as characteristic, the tendency to

possess such states and concerns is seen as an essential

attri bute, and conveyi ng evi dence of i nternal states i n a

particular

manner can be seen as characteristic, In fact, there

seems to be no i nci dental conti ngent expressi on that can' t be

taken as evidence of an essential attribute: we need only see

that to respond i n a

parti cul ar way to parti cul ar ci rcum-

stances is what might be expected in

general

of

persons as

such or a certain kind of

person or a

particular person. Note,

any

property seen as uni que to a

parti cul ar person i s l i kel y

also to serve as a means of characterizing him, A corollary is

that the absence in him of a particular property seen as

common to the cl ass of whi ch he i s a member tends to serve

si mi l arl y.

Here l et me restate the noti on that one of the most deepl y

seated trai ts of man, i t i s fel t, i s gender; femi ni ni ty and

mascul i ni ty are i n a sense the prototypes of essenti al

expressi on-somethi ng that can be conveyed fl eeti ngl y i n any

soci al si tuati on and

yet

somethi ng that stri kes at the most

basi c characteri zati on of the i ndi vi dual .

But. of course, when one tries to use the notion that

human obj ects

gi ve

off natural i ndexi cal si gns and that some

of these expressions can inform us about the essential nature

of l hei r

producer, matters

get

compl i cated. The human

obi ects themsel ves empl oy the term

"expressi on,"

and

conduct themsel ves to fi t thei r own concepti ons of ex-

pressi vi ty; i coni ci ty especi al l y abounds, doi ng so because i t

has been made to. l nstead of our merel y obtai ni ng ex-

pressi ons

of the obj ect, the obj ect obl i gi ngl y gi ves them to

us, conveyi ng them through ri tual i zati ons and communi ca-

ti ng them through symbol s. (But then i t can be sai d that thi s

gi vi ng i tsel f has uni ntended expressi ve features: for i t does

GENDER DI SPLAY 7

not seem possi bl e for a message to be transmi tted wi thout

the transmi tter and the transmi ssi on process bl i ndl y l eavi ng

traces of themselves on whatever

gets

transmitted,)

There i s, strai ght off, the obvi ous fact that an i ndi vi dual

can fake an expressi on for what can be gai ned thereby; an

i ndi vi dual i s unl i kel y to cut off hi s l eg so as to have a nature

unsui tabl e for mi l i tary servi ce, but he mi ght i ndeed sacri fi ce

a toe or affect a l i mp. In whi ch case

"because

of" becomes

"i n

order to," But that i s real l y a mi nor matter; there are

more seri ous di ffi cul ti es. I menti on three.

Fi rst, i t i s not so much the character or overal l structure

of an enti ty that gets expressed (i f such there be), but rather

parti cul ar,

si tual i onal l y-bound features rel evant to the