Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

JHP 2010

Загружено:

Cirtiu Dana0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

13 просмотров11 страницThe French version of The Ways of Coping Checklist revised (wcc-r) was completed by 622 patients and 464 completed the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI). A confirmatory factor analysis (cfa) on the original factor structure did not fit the data.

Исходное описание:

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документThe French version of The Ways of Coping Checklist revised (wcc-r) was completed by 622 patients and 464 completed the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI). A confirmatory factor analysis (cfa) on the original factor structure did not fit the data.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

13 просмотров11 страницJHP 2010

Загружено:

Cirtiu DanaThe French version of The Ways of Coping Checklist revised (wcc-r) was completed by 622 patients and 464 completed the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI). A confirmatory factor analysis (cfa) on the original factor structure did not fit the data.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 11

1246

The Ways of Coping

Checklist (WCC)

Validation in French-

speaking Cancer Patients

FLORENCE COUSSON- GLI E

Laboratoire de Psychologie Sant et Qualit de vie EA 4139,

IFR Sant publique, Universit Bordeaux 2, France

OLI VI ER COSNEFROY

Laboratoire de Psychologie Sant et Qualit de vie EA 4139,

IFR Sant publique, Universit Bordeaux 2, France

VRONI QUE CHRI STOPHE

URECA EA 1059, Equipe Famille, Sant & Emotion,

Universit de Lille 3, France, and Centre Oscar Lambret,

Lille, France

CARI NE SEGRESTAN- CROUZET

Laboratoire de Psychologie Sant et Qualit de vie EA 4139,

IFR Sant publique, Universit Bordeaux 2, Bordeaux, France

I SABELLE MERCKAERT

Psychosomatic and Psycho-Oncology Research Unit,

Universit Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium

EMMANUELLE FOURNI ER

URECA EA 1059, Equipe Famille, Sant & Emotion,

Universit de Lille 3, France, and Centre Oscar Lambret, Lille,

France

YVES LI BERT

Psychosomatic and Psycho-Oncology Research Unit,

Universit Libre de Bruxelles, and Insitut Jules Bordet,

Bruxelles, Belgium

ANA S LAFAYE

Laboratoire de Psychologie Sant et Qualit de vie EA 4139,

IFR Sant publique, Universit Bordeaux 2, France

DARI US RAZAVI

Psychosomatic and Psycho-Oncology Research Unit,

Universit Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium

Abstract

We explore the psychometric

properties of the French version of the

Ways of Coping Checklist Revised

(WCC-R) for a cancer patient sample.

The WCC-R was completed by 622

patients and 464 completed the State-

Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). A

confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on

the original factor structure did not fit

the data. The sample was randomly

divided into two subsamples.

Exploratory factor analysis was

conducted on one subsample and

revealed three factors: Seeking social

support, Problem focused-coping

and Self-blame and avoidance,

including 21 items. A CFA confirmed

this structure in the second subgroup.

These scales correlated with the

anxiety scores.

Journal of Health Psychology

Copyright 2010 SAGE Publications

Los Angeles, London, New Delhi,

Singapore and Washington DC

www.sagepublications.com

Vol 15(8) 12461256

DOI: 10.1177/1359105310364438

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. This study was partly supported by the Service

Publique Fdral Sant Publique, Scurit de la Chaine alimentaire of

Belgium under the Appel doffre-2002-16 and by the CAM (Training and

Research Group) of Belgium and by the Institut National du Cancer (INCa)

of France.

COMPETI NG I NTERESTS: None declared.

ADDRESS. Correspondence should be directed to:

FLORENCE COUSSON- GLI E, PhD, Health Psychology and Quality of

Life Laboratory, Universit de Bordeaux 2, 3 place de la Victoire, 33076,

Bordeaux, France.

Keywords

I cancer

I confirmatory factor analysis

I coping

I measurement

COUSSON-GLIE ET AL: THE WAYS OF COPING CHECKLIST (WCC)

1247

When confronted with stressful life events,

individuals normally resort to a wide range of

coping strategies to modify the impact of stress.

Research on coping over the past 30 years has been

dominated by contextual models that emphasize

coping by a person situated in a particular stressful

encounter (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984a, 1984b) or

stressful social condition (e.g. Pearlin, Lieberman,

Menaghan, & Mullin, 1981; Pearlin & Schooler,

1978). In the Lazarus transactional model of stress,

each individual faced with a stressful situation sets

up specific adjustment strategies called coping,

including a meaningful pattern of cognitive,

behavioral, emotional and somatic responses. The

first generation coping theoreticians and

researchers proposed a taxonomy taking account

two separate types of processes, leading to the

distinction between problem-focused (i.e. strategies

directed at solving the impact of the stressful event)

and emotion-focused (i.e. efforts directed at affect

regulation) coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984b).

More recent research on conceptualizing coping

included the addition of a third strategy (i.e. seeking

social support) (Greenglass, 1993; Litman, 2006),

as well other two-dimensional configurations (i.e.

approach vs. avoidance) (Holahan & Moos, 1987;

Krohne, 1996; Moos & Holahan, 2003).

The measurement of coping received a boost in the

1980s by the development of the Ways of Coping

Checklist (WCC) (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). The

WCC is a well-known measure of coping responses

derived from Lazarus transactional model of stress.

The items were derived from a problem-focused

subscale (24 items) and from an emotion-focused

subscale (40 items). Aldwin Folkman, Shaefer,

Coyne and Lazarus (1980) administered the WCC to

100 subjects and found seven interpretable factors

(one problem-focused coping and six different kinds

of emotion-focused coping). The subject-items ratio

raised the question about the quality of the factor

structure (Parker & Endler, 1992). The WCC was

validated by Vitaliano and colleagues (Vitaliano,

Russo, Carr, Maiuro, & Becker, 1985) on 425

medical students. Five subscales containing 42 items

were identified: problem-focused; seeking social

support; blamed self; wishful thinking; and

avoidance. Cousson et al. (1996) administered the

French version of the WCC validated by Vitaliano et

al. (1985) to 468 adult subjects and found a three-

factor solution: problem-focused; emotion-focused;

and social-support seeking. The revised instrument

contained a 27-item French version of the WCC with

good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and

construct and criterion validities (WCC-R; Cousson,

Bruchon-Schweitzer, Quintard, & Nuissier, 1996).

When investigating coping strategies with cancer,

some authors have typically employed measures of

coping with life stresses in general, such as the

WCC or the COPE,

1

whereas others are more

disease-specific, such as the Mental Adjustment to

Cancer scale (MAC).

2

Dunkel-Schetter, Feinstein,

Taylor, & Falke (1992) identified five coping

strategies in analyzing the factor structure of the

WCC (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984a) administered to

603 USA cancer patients: seeking or using social

support; focusing on the positive; distancing;

cognitive escape-avoidance; and behavioral escape-

avoidance. The authors did not report the percent of

total variance explained by the five factors. We

decided to use the WCC-R (Cousson et al., 1996) as

the starting point in our psychometric analysis. First,

given the importance of measuring coping with

cancer and the relative absence of coping

instruments in French-speaking subjects (only the

MAC scale validated in French cancer patients),

additional instruments are needed. Second, this

instrument is a reliable operationalization of the

concept of coping as defined by Lazarus and

Folkman, and we wanted to know both the clinical

generalizability and construct validity of the WCC

scales in French cancer patients. Third, the revised

WCC scale containing 27 items corresponded to the

three principal coping strategies identified in the

French population (Cousson et al., 1996).

The aim of the present study was to explore the

psychometric properties of the French version of the

WCC-R (Cousson et al., 1996) for a cancer patient

sample. We decided to develop a specific cancer

version of a coping questionnaire for three main

reasons: (1) the inappropriateness of some of the

WCC-R items in our sample; (2) cultural differences

interfering in the understanding of the questions by the

subjects; and (3) diversity in the factor structure due to

the specific stressful situation. Lazarus and Folkman

(1984b) indicated that a subject will cope differently

as a function of the stressful situation, in particular if

the situation is non-controllable. Cancer includes a

wide range of situations with which to cope such as

painful or secondary effects of treatment, fear of

cancer recurrence and changes in social relationships.

We also examined the construct validity and factor

structure of the original scales and the associations

with anxiety (trait and state). Previous work has

indicated that emotion-focused coping strategies are

JOURNAL OF HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY 15(8)

1248

consistently associated with greater anxiety (Ben-Zur,

1999; Cousson-Glie, 2000; David, Montgomery, &

Bovbjerg, 2006; Schnoll, Harlow, Stolbach, & Brandt,

1998). However, as pointed out by Stanton et al.

(2000), many WCC items are often confounded with

expression of emotion. Therefore, we hypothesized

that high emotion-focused coping would be linked

with high state anxiety. Since dispositional anxiety is

conceptualized as vulnerability to stress response, we

hypothesized that presence of trait-anxiety is

associated with high emotion-focused coping.

Materials and methods

Sample

To achieve a heterogeneous sample of French-

speaking cancer patients, the sample of this

multicenter, descriptive, cross-sectional study

consisted of a total of 622 patients attending two

French hospitals (n = 217) and eight Belgian

hospitals (n = 405). To fulfill the inclusion criteria,

patients had to be in- or out-patients; to be at least 18

years old; to be aware of their cancer diagnosis; to

be fit enough to complete the questionnaire

according to their physician; to be French speaking

and to be free of any cognitive dysfunction. Patients

gave their written informed consent as regards

participation in the study. They were excluded when

they had just been diagnosed or when they were

hospitalized in palliative care units. A total of 765

patients were approached and 143 patients refused

to participate (24%). Six hundred and twenty two of

the patients completed a whole questionnaire

including the WCC and a total of 464 patients

(French and Belgian) also completed the State-Trait

Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Sociodemographic

characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

The sample was randomly divided into two

subsamples of 312 and 310 participants. The first

subsample was considered as the calibration sample

and the second as the replication sample. Participants

mean age in the first subsample was 58.99

(SD = 13.10), and the mean age in the second was

57.05 (SD = 13.80). All differences between the

subsamples on demographic characteristics were non-

significant by chi-square (for the categorical variable)

or t-tests (for the continuous variables).

Measures

The French Ways of Coping Checklist WCC-R

(Cousson et al., 1996) is a 27-item coping scale

assessing three coping strategies (problem-focused

coping; emotion-focused coping; and seeking social

support) and derived from Lazarus and Folkmans

WCC, which was validated by Vitaliano et al.

(1985) in 425 medical students. The French form of

the WCC presents good construct and criterion

validities in the general population (Bruchon-

Schweitzer, Cousson, Quintard, & Nuissier, 1996).

Respondents use a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging

from No to Yes.

The State-Trait-Anxiety Inventory, form Y

(Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vaag, & Jacobs,

1983) consists of two scales, one assessing anxiety

as a personality trait (20 items) and the other

assessing anxiety as a state (20 items). The STAI

has been demonstrated to be reliable for the French

population (Bruchon-Schweitzer & Paulhan, 1993).

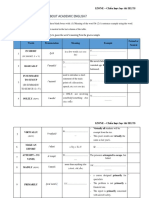

Table 1. Patient characteristics

Characteristic n %

Age

40 years 64 10.3

4150 years 122 19.6

5160 years 178 28.6

6170 years 160 25.7

> 70 years 98 15.8

Sex

Female 475 76.4

Male 147 23.6

Diagnosis

Breast 372 59.8

Lung 49 7.9

Gastrointestinal 38 6.1

Gynaecological 30 4.8

Bladder 26 4.2

Lymphoma 21 3.4

Head and neck 20 3.2

Melanoma 11 1.8

Nervous system 9 1.4

Prostate 8 1.3

Sarcoma 7 1.1

Hodgkin 5 0.8

Thyroid 1 0.2

Others 25 4.0

Partner status

Un-partnered 137 28.6

Partnered 447 71.4

Stage of the disease

Local 368 59.16

Local-regional 138 22.18

Metastatic 99 15.92

Unknown 17 2.73

COUSSON-GLIE ET AL: THE WAYS OF COPING CHECKLIST (WCC)

1249

Statistical methods

The psychometric properties of the WCC-R

(univariate statistics, internal consistencies) are

presented. The calibration sample was used to perform

two steps. First, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

was performed to test the structural properties of the

27 items for testing the factorial structure initially

identified with non-cancer French subjects. Second, if

CFA did not fit the data, then Exploratory Factor

Analysis (EFA) was conducted followed by

congeneric confirmatory factor analysis to refine the

scales. Finally, a novel CFA on the replication sample

was performed to test the new version. Pearson

product-moment correlation coefficients were

calculated to assess criterion validity.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

Data obtained from the WCC-R are based on a

4-point Likert-type scale. Although the items

measure a continuous construct, this kind of response

format is considered as ordinal scaled data because it

does not have equally spaced intervals. When

observed variables are ordinal, previous research

findings support a model estimation using polychoric

correlations, which have been found to perform

better than Pearson correlations (DiStefano, 2002;

Flora & Curran, 2004; Gilley & Uhlig, 1993;

Jreskog & Moustaki, 2001, 2006; Kim & Muller,

1978). Furthermore, a recent work by Wirth and

Edwards (2007) demonstrates the importance of

using categorical estimation techniques when using

fewer than five response categories and of comparing

results using various estimation methods. We thus

selected two estimation methods to calculate the

model parameters and fit. The Unweighted Least

Squares (ULS) method has been shown to be fairly

robust (Ximnez, 2007) and the Diagonally

Weighted Least Squares (DWLS) method seems to

perform well across many conditions (Flora &

Curran, 2004). We compared the results from both

methods to determine whether or not the different

methods led to different conclusions. The ULS

method was run using the covariance matrix and the

DWLS method was run by incorporating the

polychoric correlation matrix. The DWLS also

required an estimate of the asymptotic covariance

matrix of the sample correlations.

The covariance, polychoric correlation matrices and

the asymptotic covariance matrix were calculated by

using PRELIS 2.8. Two models were specified and

estimated by using LISREL 8.8: the three-factor model

with 27 items fromCousson et al. (1996) and a newone

based on the EFA results. To test the quality of

adjustment of these models, we selected a chi-square/

degree of freedom ratio smaller than 2.0. To take

account of sample size, we report the Comparative Fit

Index (CFI) and the Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index

(AGFI). Values close to .95 were considered to indicate

acceptable model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The Root

Mean Square Error of Approximation RMSEA of less

than .05 indicated good fit, while a value of .08 was not

to be exceeded. We chose to drop items which

explained variance smaller than 0.21, as did Osborne

Elsworth, Kissane, Burke and Hopper (1999) and

Cayrou, Dickes, Gauvain-Piquard and Roge (2003) in

the same type of study. Finally, none of our models

allowed errors between items to correlate.

Exploratory factorial analysis

To select items to form a new version of the WCC,

we based our analysis on the 27-item coping scale

assessing three coping strategies (problem-focused

coping; emotion-focused coping; and seeking social

support). EFA was calculated using the ML method

with Oblique (Promax) rotations on the polychoric

correlation matrix. Items were retained if their

unique variance was < 0.80, their factor loading

> 0.40 or cross-loadings < 0.30 on a second factor.

Because we used polychoric correlations, we checked

for violations of underlying bivariate normality

assumptions using the comparison of Likelihood

Ratio (LR) test statistic and Goodness-of-Fit (GF)

statistic for each correlation when the Root Mean

Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was larger

than 0.1 (Jreskog, 2001)

Using the congeneric measurement model, the

three subsamples of items tested using three distinct

submodels hypothesized a single factor explaining

the common variance of the corresponding items

(Cayrou et al., 2003; Nordin, Berglund, Terje, &

Glimelius, 1999).

Results

Reliability and mean value

As assessment of the reliability (internal consistency)

coefficient alpha was computed for the three original

WCC subscales. The reliability coefficients were

comparable with those we reported with non-cancer

subjects (Cousson et al., 1996) with the exception of

seeking social support (see Table 2). Estimates of

reliability (Cronbachs ) were satisfactory for two

original scales, emotion-focused coping ( = 0.76)

JOURNAL OF HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY 15(8)

1250

and problem-focused coping ( = 0.79), with the

exception of seeking social support ( = 0.69). This

suggested that this subscale is in need of

improvement. The mean of social support was

significantly higher in cancer patients than in the

general population (t = 3.98, p < 0.001).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

Before using the polychoric correlation matrix, we

checked for the assumption of underlying bivariate

normality and found no correlations violating this

assumption. We used a CFAto test the factor structure

initially found by Cousson et al. (1996) where three

factors were identified: problem-focused coping (10

items); emotion-focused coping (9 items); and social

support seeking coping (8 items).

3

The result of CFA

on these 27 items and three oblique factors

hypothesized showed a lack of adjustment. The

indices for the confirmatory factor models for Models

1.a and 1.b (see Table 3), using two distinct methods

but testing this theoretical model (three factors with 27

items), showed an inadequate fit. None of the selected

indices reached the standard chosen and four of the 27

items showed an explained variance lower than 0.21.

Therefore, this model was rejected and not considered

as the best explanation of the data.

Exploratory factor analysis and

congeneric factor analysis

Owing to the lack of adjustment, we ran EFA.

Analysis based on the scree plot did not really show

an elbow in the plot. However, the contributions

were relatively low after the sixth component. In

order to complete our analysis we used a parallel

analysis and retained only those factors whose

actual eigenvalues were greater than the eigenvalues

from the random data. The results indicate that only

the first four eigenvalues were greater than those

generated by parallel analysis (for both the average

and 95th percentile criteria based on 1000 iterations)

and thus had to be initially retained. The results on

the fourth factor were hardly interpretable with only

one item loading on this statistical factor. We finally

retained a three-factor solution. This result agrees

with the preceding conclusion that three factors

provide a reasonable summary of the data and

provide an optimal meaningfully interpretable

solution (Cousson et al., 1996).

Of the 27 survey items, 21 were retained for further

analyses. Three items were considered complex (i.e.

had a high loading on more than one component) and

three others were deleted because their unique

variance was greater than 0.80 (see the last six items in

Table 5). Congeneric factor analysis showed no items

Table 2. Psychometric properties of the WCC subscales

WCC Subscales n M SD

Cousson et al., 1996

Social support (8 items) 468 20.33 4.89 .76

Emotion-focused 468 21.00 5.59 .72

coping (9 items)

Problem-focused 468 27.3 5.79 .79

coping (10 items)

Present study

Social support (8 items) 622 23.93 5.45 .69

Emotion-focused 622 21.11 6.16 .76

coping (9 items)

Problem-focused 622 28.42 6.68 .79

coping (10 items)

Present study

Social support (6 items) 622 18.11 5.15 .79

Emotion-focused 622 14.70 5.12 .74

coping (7 items)

Problem-focused 622 23.05 5.65 .78

coping (8 items)

Table 3. Fit indices for the confirmatory factor models of the WCC questionnaire

Model Method

2

df p

2

/df RMSEA CFI AGFI

Model 1.a: 27 items/ 3 factors ULS 845.40 321 < 0.0 2.63 0.13 1.00 0.92

Model 1.b: 27 items/ 3 factors DWLS 780.05* 321 < 0.0 2.43 0.07 0.94 0.92

Model 2.a: 21 items/ 3 factors ULS 341.86 186 < 0.0 1.84 0.05 0.94 0.94

Model 2.b: 21 items/ 3 factors DWLS 342.96* 186 < 0.0 1.84 0.05 0.98 0.97

Notes:

ULS = Unweighted Least Squares; DWLS = Diagonally Weighted Least Squares;

2

/ df = chi-square - degree of

freedom ratio, RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation. CFI = Comparative Fit Index; AGFI= Adjusted

Goodness-of-Fit Index.

* Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square

COUSSON-GLIE ET AL: THE WAYS OF COPING CHECKLIST (WCC)

1251

whose explained variance was less than 0.21. For each

factor, fit indices showed an acceptable value. We

therefore selected the 21 items.

The three factors explained 37.8 percent of the total

variance. Loadings for this solution are shown in

Table 4. Factor 1 consisted of five items that indicated

seeking social support behavior, including, asking for

advice, for an objective intervention, for the help of a

professional person, and one itemregarding emotional

support (expressing ones emotions). This factor could

be named seeking social support. The second factor

comprised seven items that mainly reflected self-

blame attribution (criticizing or lecturing oneself,

feeling guilty) and avoidance (hoping for a miracle,

feeling bad for not avoiding the situation, trying to

forget everything). This factor was named Self-blame

and Avoidance. The third factor comprised eight items

that indicated an active and optimistic psychological

outlook on the illness, including, fighting spirit,

feeling stronger, taking things one by one, and finding

some solutions. This could be interpreted in terms of

Problem-focused coping.

Confirmatory factor analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to

analyze the fit of this new 21-item three-factor

solution in the replication subsample (N = 310). The

three-factor solution was also tested with correlated

factors. All regression paths and correlations were

found to be significant. Whatever the method, the

results indicate that the three-factor solution with 21

items fits the data (see Models 2.a and 2.b in Table 3).

Correlations between the new WCC

subscales and reliability

Correlations among the three new subscales showed

Seeking Social Support to be positively associated

with Avoidance and Self-blame (r = 0.25, p <

0.001), and strongly and positively associated with

Problem-focused Coping (r = 0.70, p < 0.001).

Avoidance and Self-blame was also positively

associated with Problem-focused Coping (r = 0.28,

p < 0.001). Estimates of reliability with Cronbachs

(N = 622) were satisfactory for all the new WCC

subscales (see Table 2).

Correlations between the WCC and

anxiety scales

The results showed a positive association between

state anxiety and Self-blame/Avoidance (r = 0.30,

p < 0.001), and a negative association between State

Anxiety and Problem-focused Coping (r = 0.19,

p < 0.001). Trait anxiety was also positively associated

with Self-blame/Avoidance (r = 0.47, p < 0.0001)

and negatively associated with Problem-focused

Coping (r = 0.13, p < 0.01). No significant correla-

tions were found between anxiety scales (trait and

state) and Seeking Social Support (respectively,

r = 0.01, p = 0.77; r = 0.02, p = 0.70).

Comparisons of mean WCC scores

for age, sex, diagnosis, partner

status and stage of the disease

Results on all the subjects (N =622) showed no

significant differences for age on mean WCC scores.

However, women had lower mean scores on the

Seeking Social Support (t = 4.64, p < 0.001) and Self-

blame/Avoidance scale (t = 2.62, p < 0.01) than men.

Breast cancer patients had lower mean scores on

Seeking Social Support (t = 5.60, p < 0.001), on Self-

blame/Avoidance (t = 2.43, p <0.05) and on Problem-

focused Coping (t = 4.82, p < 0.001) than patients

with other types of cancer.

We found no significant differences between

patients living with a partner or those living alone

for the three scores of the WCC (t = 0.20, p = 0.83;

t = 1.13, p = 0.26; t = 1.02, p = 0.29).

Discussion

The present study used a complete procedure to test the

psychometric properties of the WCC in a sample of

French-speaking cancer patients. First, we conducted a

CFA to test the factor structure obtained with 468

healthy French-speaking participants (Cousson et al.,

1996). Results showed that this factor structure did not

fit the cancer patient data, so we conducted an initial

exploratory factor analysis followed by a confirmatory

factor analysis based on a large sample. EFAidentified

a factor structure with three principal dimensions:

seeking social support (6 items); self-blamed

attribution and avoidance (7 items); and problem-

focused coping (8 items). All the items retained

correspond to the original scales of the WCC validated

in French-speaking subjects but some items were

dropped: three items (item numbers 2, 5 and 15) of the

original emotion-focused coping, two items of

problem-focused coping (items numbers 19 and 22)

and one item (item number 21) of the social support

seeking scale. According to current methodological

recommendations, we found a stable factor structure

whatever the method used. The internal consistency of

each of these subscales is satisfactory.

JOURNAL OF HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY 15(8)

1252

Table 4. Factor loading estimates for ML with Promax-rotated factor in calibration sample (N = 310)

Self-blamed Problem-

Social attribution and focused Unique

Items support avoidance coping variance

Q18

a

Talked to someone who could do SS

b

0.86 0.00 0.02 0.28

something about the problem.

Q 12 Talked to someone to find out SS 0.86 0.09 0.09 0.29

about the situation.

Q 09 Asked someone I respected for SS 0.80 0.01 0.02 0.34

advice and followed it.

Q 06 Got professional help and SS 0.57 0.15 0.09 0.64

did what they recommended.

Q 03 Talked to someone about how SS 0.57 0.10 0.02 0.68

I was feeling.

Q 24 Accepted sympathy and SS 0.51 0.03 0.28 0.52

understanding from someone.

Q 14 Blamed myself. E 0.13 0.77 0.23 0.49

Q 26 Criticized or lectured myself. E 0.11 0.77 0.13 0.49

Q 17 Thought about fantastic or unreal E 0.03 0.62 0.11 0.54

things that made me feel better.

Q 11 Hoped a miracle would happen. E 0.18 0.62 0.14 0.59

Q 23 Wished I could change the way that I felt. E 0.08 0.58 0.13 0.62

Q 08 Felt bad that I couldnt avoid the problem. E 0.17 0.54 0.00 0.64

Q 20 Tried to forget the whole thing. E 0.04 0.48 0.09 0.75

Q 27 I know what had to be done, so I doubled P 0.12 0.14 0.84 0.44

my efforts and tried harder to make

things work.

Q 16 Came out of the experience better than P 0.19 0.02 0.72 0.59

when I went in.

Q 01 Made a plan of action and followed it. P 0.07 0.15 0.68 0.63

Q 10 Just took things one step at a time. P 0.07 0.05 0.63 0.57

Q 04 Stood my ground and fought for what P 0.13 0.01 0.60 0.55

I wanted.

Q 25 Came up with a couple of different solutions P 0.18 0.05 0.49 0.62

to the problem.

Q 13 Concentrated on something good that could P 0.17 0.10 0.45 0.64

come out of the whole thing.

Q 07 Changed or grew as a person in a good way. P 0.12 0.23 0.41 0.63

Eliminated items

Q 19 Changed something so things would turn P 0.12 0.36 0.39 0.53

out all right.

Q 02 Wished the situation would go away or E 0.41 0.26 0.09 0.64

somehow be finished.

Q 05 Wished that I could change what had happened. E 0.28 0.41 0.02 0.68

Q 15 Kept my feelings to myself. E 0.40 0.32 0.24 0.80

Q 21 Tried not to burn my bridges behind me, but SS 0.15 0.07 0.17 0.93

left things open somewhat.

Q 22 Tried not to act too hastily or follow my P 0.01 0.08 0.33 0.87

own hunch.

Notes:

Factor loadings > .40 are in boldface

a

Item number in the original WCC

b

Abbreviations for the original WCC subscales: SS, social support; E, emotion-focused coping; P, problem-focused

coping

COUSSON-GLIE ET AL: THE WAYS OF COPING CHECKLIST (WCC)

1253

We found that seeking social support was strongly

and positively associated with problem-focused

coping. This result is consistent with the findings of

Vitaliano et al. (1985) in which problem-focused

coping was correlated with seeking social support

(r = .70). For four items of the seeking social support

scale, the patient solicited someones help in order to

solve the problem: talked to someone who could do

something about the problem, talked to someone to

find out about the situation, asked someone I

respected for advice and followed it, got professional

help and did what they recommended, whereas for

only two items did the patient seek social support to

help them express how they felt. So although the

correlations are high, seeking social support should be

separated from problem-focused coping.

The relationship of the coping scales to partner

status and age were either nonexistent or minimal.

However, gender was significantly related to the

seeking social support score and the Self-blame/

Avoidance scale. These results are partly consistent

with the finding of Cousson et al. (1996) in which

men were more likely to use social support than

women. However, the results about avoidance do not

agree with previous findings that reported higher

scores on avoidance strategies in females than males

(Matud, 2004). Nevertheless, not all these studies

were conducted with cancer patients. We hypothesize

that when confronted with a high stressor like cancer,

women do not avoid the situation. In this study, we did

not expect a difference in factorial structure because

we did not obtain it with the general population

(Cousson et al., 1996), and previous studies using the

WCC did not find any sex differences in coping with

cancer (Dunkel-Shetter et al., 1992).

As pointed out by Nordin et al. (1999), the value of

using the WCC as a measure of coping rather than the

MAC scale developed by Watson et al. (1988) is that

the WCC corresponds to the coping theory developed

by Lazarus and Folkman (1984a, 1984b). Previous

results concerning factor analysis of the MAC are not

congruent. The original structure proposed by Watson

et al. (1988) was not replicated by Schwartz et al.

(1992) on 239 USA cancer patients, nor by Nordin et

al. (1999) in a heterogeneous Swedish sample of

cancer patients (n = 868).

The subscales of the MAC contain components of

mental adjustment like threat and anxiety, which are

arguably not coping strategies but rather an emotional

reaction to diagnosis and illness. While the anxious

preoccupation subscales of the MAC focus more on

outcomes, Lazarus pointed out the importance of

separating appraisal, coping and outcome (Lazarus &

Folkman, 1984a). In our clinical experience, some

MAC items were judged by patients as shocking (I

dont have cancer). Another limitation with the

research on coping with cancer using the MAC scale,

as suggested by Nordin et al. (1999), is that it

confounds coping with distress outcome.

The negative correlation between the WCC

problem-focused coping scale for cancer patients and

anxiety and the positive correlation between avoidant/

self-blame and anxiety are consistent with previous

findings (Ben-Zur, 1999; Cousson-Glie, 2000; David

Table 5. Means (and standard deviation) for WCC scores depending on age, sex, diagnosis, partner status of cancer patients

N Seeking social support Avoidance/Self- blame Problem-focused coping

Age

40 years 64 15.44 (4.18) 14.84 (5.31) 23.58 (5.17)

4150 years 122 14.25 (4.45) 14.51 (5.06) 22.47 (5.47)

5160 years 178 14.48 (4.91) 14.20 (5.02) 23.49 (5.67)

6170 years 160 14.67 (4.52) 14.93 (4.78) 22.86 (5.46)

> 70 years 98 15.39 (4.61) 15.13 (5.78) 23.74 (5.67)

Sex

Female 475 14.30** (4.69) 14.59 (5.18) 22.86** (5.63)

Male 147 16.13** (4.03) 14.99 (4.93) 24.22** (5.05)

Diagnosis

Breast cancer 376 13.84* (4.77) 14.33* (5.23) 22.31* (5.67)

Other cancer 246 15.89* (4.16) 15.36* (4.96) 24.45* (5.10)

Partner status

Un-partnered 137 14.78 (4.89) 15.05 (5.34) 23.5531 (5.97)

Partnered 447 14.70 (4.49) 14.53 (5.02) 23.0293 (5.34)

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

JOURNAL OF HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY 15(8)

1254

et al., 2006; Schnoll et al., 1998) and support our

hypotheses about the relationship between coping

factors and outcome. The absence of relation between

anxiety scales and Seeking Social Support was also

found with non-cancer French subjects (Cousson

et al., 1996). Such findings are more surprising with

cancer patients. Previous studies showed that emotional

social support from family and friends is associated

with good adjustment to the disease (Alferi, Carver,

Antoni, Weiss, & Durn, 2001; Dunkel-Schetter, 1984;

Funch & Marshall, 1983; Hoskins, Baker, Sherman, &

Bohlander, 1996; Moyer & Salovey, 1996; Neuling &

Winefield, 1988; Northouse & Swain, 1987; Parker,

Baile, De Moor, & Cohen, 2003). However, those

studies evaluated perceived social support but not social

support as a coping strategy. One study noted that

cancer patients who reported more stress seek more

social support (Dunkel-Schetter et al., 1992).

Unfortunately, coping strategies and anxiety are

assessed at the same time and it is impossible to unravel

whether one leads to the other. Further longitudinal

research is needed to test the relationship between the

subscales of this WCC adapted for cancer patients and

a range of psychosocial outcomes such as anxiety,

depression and quality of life. Another aspect to be

considered in future research is the relative

inconsistency of coping strategies over time.

The present findings represent a first step towards

a valid measure of the WCC in a sample of French-

speaking cancer patients. This short 21-item version

of the WCC is easier to use in a protocol than the

initial 27-item version. However, a single study is

not a sufficient basis for establishing the construct

validity of an instrument. Comparisons in other

samples and relationships with other measures of

similar constructs will be included in further studies.

Notes

1. The COPE (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989)

consists of 13 scales: five scales assessing problem-

focused coping, five scales assessing emotion-focused

coping and three scales assessing focusing on and

venting emotion, behavioral disengagement, and

mental disengagement.

2. The Mental Adjustment Cancer (MAC) scale was

then developed to evaluate adjustment styles in

clinical trials (Watson et al., 1988) following the

publication by Greer, Morris and Pettingale (1979) of

a link between coping strategy (i.e. fighting spirit) and

length of survival. A French validation of the MAC

retained only three dimensions: fighting spirit;

hopelessness/helplessness; and anxious preoccupation

(Cayrou, Dickes, Gauvain-Piquard, & Roge, 2003).

3. The authors administered the WCC (42 items)

validated by the Vitaliano et al. (1985) questionnaire to

468 adults French subjects (males and females). A

principal component analysis followed by varimax

rotations yielded three factors accounting for about 35

percent of the total variance. They were interpreted as

Problem-focused, Emotion-focused and Social-support

Seeking types of coping. Fifteen items were dropped.

References

Alferi, S. M., Carver, C. S., Antoni, M. H., Weiss, S., &

Durn, R. E. (2001). An exploratory study of social

support, distress, and life disruption among low-income

Hispanic women under treatment for early stage breast

cancer. Health Psychology, 20(1), 4146.

Aldwin, C., Folkman, S., Shaefer, C., Coyne, J., &

Lazarus, R. S. (1980). Ways of Coping Checklist: Process

measure. Paper presented at the Annual American

Psychological Association Meetings, Montreal, Canada.

Ben-Zur, H. (1999). The effectiveness of coping meta-

strategies: Perceived efficiency, emotional correlates

and cognitive performance. Personality and Individual

Differences, 26(5), 923939.

Bruchon-Schweitzer, M., Cousson, F., Quintard, B., &

Nuissier, J. (1996). French adaptation of the ways of coping

checklist. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 83(1), 104106.

Bruchon-Schweitzer, M., & Paulhan, I. (1993). Manuel

franais de lchelle dAnxit Trait, Anxit Etat de

C.D., Spielberger. Paris: ECPA.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989).

Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based

approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

56(2), 267283.

Cayrou, S., Dickes, P., Gauvain-Piquard, A., & Roge, B.

(2003). The Mental Adjustment to Cancer (MAC) scale:

French replication and assessment of positive and negative

adjustment dimensions. Psycho-Oncology, 12(1), 823.

Cousson, F., Bruchon-Schweitzer, M., Quintard, B., &

Nuissier, J. (1996). Analyse multidimensionnelle dune

chelle de coping: validation franaise de la W.C.C.

(Ways of Coping Checklist). Psychologie Franaise,

41(2), 155164.

Cousson-Glie, F. (2000). Breast cancer, coping and

quality of life: A semi-prospective study. European

Review of Applied Psychology, 50(3), 315320.

David, D., Montgomery, G. H., & Bovbjerg, D. H. (2006).

Relations between coping responses and optimism-

pessimism in predicting anticipatory psychological

distress in surgical breast cancer patients. Personality

and Individual Differences, 40(2), 203213.

DiStefano, C. (2002). The impact of categorization with

confirmatory factor analysis. Structural Equation

Modeling, 9(3), 327346.

Dunkel-Schetter, C. (1984). Social support and cancer:

Findings based on patient interviews and their

implications. Journal of Social Issues, 40(4), 7798

Dunkel-Schetter, C., Feinstein, L. G., Taylor, S. E., &

Falke, R. L. (1992). Patterns of coping with cancer.

Health Psychology, 11(2), 7987.

Flora, D. B., & Curran, P. J. (2004). An empirical

evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for

confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data.

Psychological Methods, 9(4), 466491.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of

coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of

Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 219239.

Funch, D. P., & Marshall, J. (1983). The role of stress,

social support and age in survival from breast cancer.

Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 27(1), 7783.

Gilley, W. F., & Uhlig, G. E. (1993). Factor analysis and

ordinal data. Education, 114(2), 258.

Greenglass, E. R. (1993). The contribution of social

support to coping strategies. Applied Psychology: An

International Review, 42(4), 323340.

Greer, S., Morris, T., & Pettingale, K. W. (1979).

Psychological response to breast cancer. Lancet,

314(8146), 785787.

Holahan, C. J., & Moos, R. H. (1987). Personal and

contextual determinants of coping strategies. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 52(5), 946955.

Hoskins, C. N., Baker, S., Sherman, D., & Bohlander, J.

(1996). Social support and patterns of adjustment to

breast cancer. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice,

10(2), 99123.

Hu, L.-t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria

for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis:

Conventional criteria versus. Structural Equation

Modeling, 6(1), 1.

Jreskog, K. G. (2001). Structural equation modeling with

ordinal variables using LISREL. http://www.ssicentral.

com/lisrel/techdocs/ordinal.pdf

Jreskog, K. G., & Moustaki, I. (2001). Factor analysis of

ordinal variables: A comparison of three approaches.

Multivariate Behavioral Research, 36(3), 347387.

Jreskog, K. G., & Moustaki, I. (2006). Factor analysis of

ordinal variables with full information maximum

likelihood.http://www.ssicentral.com/lisrel/techdocs/or

fiml.pdf

Kim, J.-O., & Muller, C. W. (1978). Factor analysis:

Statistical methods and practical issues. Newbury Park,

CA: Sage.

Krohne, H. W. (1996). Individual differences in coping. In

M. Zeidner & N. S. Endler (Eds.), Handbook of coping:

Theory, research and implications (pp. 381406). New

York: John Wiley & Sons.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984a). Stress, appraisal

and coping. New York: Springer.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984b). Stress, coping and

adaptation. New York: Springer.

Litman, J. A. (2006). The COPE inventory:

Dimensionality and relationships with approach- and

avoidance-motives and positive and negative traits.

Personality and Individual Differences, 41(2), 273284.

Matud, M. P. (2004). Gender differences in stress and

coping styles. Personality and Individual Differences,

37(7), 14011415.

Moos, R. H., & Holahan, C. J. (2003). Dispositional and

contextual perspectives on coping: toward an

integrative framework. Journal of Clinical Psychology,

59(12), 13871403.

Moyer, A., & Salovey, P. (1996). Psychosocial sequelae

of breast cancer and its treatment. Annals of Behavioral

Medicine, 18(2), 110125.

Neuling, S. J., &Winefield, H. R. (1988). Social support and

recovery after surgery for breast cancer: Frequency and

correlates of supportive behaviours by family, friends and

surgeon. Social Science & Medicine, 27(4), 385392.

Nordin, K., Berglund, G., Terje, I., & Glimelius, B.

(1999). The Mental Adjustment to Cancer scale A

psychometric analysis and the concept of coping.

Psycho-Oncology, 8(3), 250259.

Northouse, L. L., & Swain, M. A. (1987). Adjustment of

patients and husband to the initial impact of breast

cancer. Nursing Research, 36(4), 221225.

Osborne, R. H., Elsworth, G. R., Kissane, D. W., Burke, S. A.,

& Hopper, J. L. (1999). The Mental Adjustment to Cancer

(MAC) scale: Replication and refinement in 632 breast

cancer patients. Psychological Medicine, 29(6), 13351345.

Parker, P. A., Baile, W. F., De Moor, C., & Cohen, L.

(2003). Psychosocial and demographic predictors of

quality of life in a large sample of cancer patients.

Psycho-Oncology, 12(2), 183193.

Parker, J. D., & Endler, N. S. (1992). Coping with coping

assessment: A critical review. European Journal of

Personality, 6(5), 321344.

Pearlin, L. I., Lieberman, M. A., Menaghan, E. G., &

Mullan, J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of

Health and Social Behavior, 22(4), 337356.

Pearlin, L. I., & Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of coping.

Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19(1), 221.

Schnoll, R. A., Harlow, L. L., Stolbach, L. L., & Brandt,

U. (1998). A structural model of the relationships

among stage of disease, age, coping, and psychological

adjustment in women with breast cancer. Psycho-

Oncology, 7(2), 6977.

Schwartz, C. E., Daltroy, L. H., Brandt, U., Friedman, R.,

& Stolbach, L. (1992). A psychometric analysis of the

Mental Adjustment to Cancer scale. Psychological

Medicine, 22(1), 203210.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R., Vaag, P.

R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for the State-Trait-

Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Palo Alto: Consulting

Psychologists Press Inc.

Stanton, A. L., Danoff-Burg, S., Cameron, C. L., Bishop,

M., Collins, C. A., Kirk, S. B., et al. (2000). Emotionally

expressive coping predicts psychological and physical

adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and

Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 875882.

Vitaliano, P. P., Russo, J., Carr, J. E., Maiuro, R., & Becker,

J. (1985). The Ways of Coping Checklist: Revision

COUSSON-GLIE ET AL: THE WAYS OF COPING CHECKLIST (WCC)

1255

JOURNAL OF HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY 15(8)

1256

and psychometric properties. Multivariate Behavioral

Research, 20(1), 326.

Watson, M., Greer, S., Young, J., Inayant, Q., Burgess, C.,

& Robertson, B. (1988). Development of a

questionnaire measure of adjustment to cancer: the

MAC scale. Psychological Medicine, 18(1), 203209.

Wirth, R. J., & Edwards, M. C. (2007). Item factor analysis:

current approaches and future directions. Psychological

Methods, 12(1), 5879.

Ximnez, C. (2007). Effect of variable and subject

sampling on recovery of weak factors in CFA.

Methodology, 3(2), 6780.

FLORENCE COUSSON-GLIE, PhD, has been a senior

lecturer in Health Psychology since 1998 at the

University of Bordeaux 2 (France). Her studies

focus on cancer patients quality of life, coping

strategies, locus of control, social support and

psychosocial interventions. She also studies the

impact of cancer on family relationships.

OLIVIER COSNEFROY is study engineer and data

manager at the University of Bordeaux 2. He

collaborates on research projects in health

psychology and child development.

VRONIQUE CHRISTOPHE, PhD, is a lecturer in

Social and Health Psychology at Lille North of

France University. Her research interests include

self and social regulation of emotion, its

consequences on interpersonal relationships, and

on chronic disease, especially on cancer.

CARINE SEGRESTAN-CROUZET is a PhD student at

Bordeaux 2 University (France) and Psychologist

at the Libourne Hospitals Oncology Unit. Her

clinical and research interests include the role of

transactional variables, such as social support and

coping strategies, in women and couples coping

with breast cancer, patient education, and

cognitive-behavioral therapy.

ISABELLE MERCKAERT has been Assistant Professor

at the Universit Libre de Bruxelles since 2008

(Belgium) and collaborates actively on research

projects in the field of physician-patient

communication in cancer care. She also works part-

time as a clinical psychologist in the Belgian cancer

centre Institut Jules Bordet. Her main focus of

interest lies in the relationships of health-care

professionals with patients and their families in

cancer care. More precisely, her research topics

focus on how to improve physicians

communication skills with cancer patients and their

families and on the exchange of information in the

context of informed consent in cancer clinical trials.

EMMANUELLE FOURNIER is a psychologist and

research engineer at Lille North of France

University. She works with the staff of Famille,

Sant, Emotions, especially in cancerology.

YVES LIBERT, PhD, is Master of Lectures at the

Universit Libre de Bruxelles (Belgium) and

collaborates actively on research projects in three

main fields: oncogeriatry; clinical support given to

the patient and their relatives; and physicianpatient

communication in cancer care. He is also a clinical

psychologist at the Belgian cancer centre Institut

Jules Bordet. One of his main research topics focuses

on how to improve the psychological support given

to cancer patients and their informal caregivers.

ANAS LAFAYE received her PhD in Psychology in

2009 at the University of Bordeaux 2, in France. Her

research interests concern prostate cancer patients

and their spouses quality of life and emotional state,

and the actor and partner effects of social support,

coping strategies and dyadic adjustment on quality

of life, anxiety and depression.

DARIUS RAZAVI is a neuro-psychiatrist and

Professor at the Universit Libre de Bruxelles. He

is at present the director of a Psychosomatic and

Psycho-oncology Research Unit (PPRU) at the

Universit Libre de Bruxelles and the head of the

Psycho-oncology, Pain and Palliative Care Clinic at

Institut Jules Bordet, Cancer Center of the

Universit Libre de Bruxelles. His research focuses

on the interface of psychiatry and oncology:

communication skills, screening of psychiatric

disorders, treatment of anxiety and depression,

psycho-endocrinology and smoking cessation.

Author biographies

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Class Reading Profile: Name of PupilДокумент2 страницыClass Reading Profile: Name of PupilPatrick EdrosoloОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- PIIS0261561422000668 Micronitrientes: RequerimientosДокумент70 страницPIIS0261561422000668 Micronitrientes: Requerimientossulemi castañonОценок пока нет

- Statement of PurposeДокумент5 страницStatement of PurposesagvekarpoojaОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Pelvic Fracture Case StudyДокумент48 страницPelvic Fracture Case StudyYves BasanОценок пока нет

- 04fc75de986c12 Pharmaceutics-I AROMATIC WATERSДокумент14 страниц04fc75de986c12 Pharmaceutics-I AROMATIC WATERSsultanОценок пока нет

- Hazops Should Be Fun - The Stream-Based HazopДокумент77 страницHazops Should Be Fun - The Stream-Based HazopHector Tejeda100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Cold Agglutinin DiseaseДокумент8 страницCold Agglutinin Diseasehtunnm@gmail.comОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Below The Breadline: The Relentless Rise of Food Poverty in BritainДокумент28 страницBelow The Breadline: The Relentless Rise of Food Poverty in BritainOxfamОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Ijtk 9 (1) 184-190 PDFДокумент7 страницIjtk 9 (1) 184-190 PDFKumar ChaituОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- IEEE Guide To The Assembly and Erection of Concrete Pole StructuresДокумент32 страницыIEEE Guide To The Assembly and Erection of Concrete Pole Structuresalex aedoОценок пока нет

- Boracay Rehabilitation: A Case StudyДокумент9 страницBoracay Rehabilitation: A Case StudyHib Atty TalaОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Safe Operating Procedure Roller: General SafetyДокумент4 страницыSafe Operating Procedure Roller: General SafetyRonald AranhaОценок пока нет

- Pediatric Dosing For OTCsДокумент5 страницPediatric Dosing For OTCsCareyTranОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- ErpДокумент31 страницаErpNurul Badriah Anwar AliОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- 978 3 642 25446 8Документ166 страниц978 3 642 25446 8Gv IIITОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Statistical EstimationДокумент37 страницStatistical EstimationAmanuel MaruОценок пока нет

- Corpus Alienum PneumothoraxДокумент3 страницыCorpus Alienum PneumothoraxPratita Jati PermatasariОценок пока нет

- Cleaning Reusable Medical DevicesДокумент12 страницCleaning Reusable Medical DevicesDavid Olamendi ColinОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- 13fk10 Hav Igg-Igm (D) Ins (En) CeДокумент2 страницы13fk10 Hav Igg-Igm (D) Ins (En) CeCrcrjhjh RcrcjhjhОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- 16-23 July 2011Документ16 страниц16-23 July 2011pratidinОценок пока нет

- IZONE Academic WordlistДокумент59 страницIZONE Academic WordlistTrung KiênОценок пока нет

- Talent MappingДокумент18 страницTalent MappingSoumya RanjanОценок пока нет

- Ankylosing SpondylitisДокумент4 страницыAnkylosing SpondylitisSHIVENDRA YADAVОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Pediatric Blood PressureДокумент28 страницPediatric Blood PressureGenta Syaifrin Laudza0% (1)

- Tsoukaki 2012Документ8 страницTsoukaki 2012Marina JoelОценок пока нет

- Administration of PICU Child Health NursingДокумент37 страницAdministration of PICU Child Health NursingJimcy100% (3)

- TinnitusДокумент34 страницыTinnitusHnia UsmanОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Format OpnameДокумент21 страницаFormat OpnamerestutiyanaОценок пока нет

- Excerpts From IEEE Standard 510-1983Документ3 страницыExcerpts From IEEE Standard 510-1983VitalyОценок пока нет

- Cigna SmartCare Helpful GuideДокумент42 страницыCigna SmartCare Helpful GuideFasihОценок пока нет