Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Holschbach, Susanne - Continuities and Differences Between Photographic and Post-Photographic Mediality

Загружено:

bashevisИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Holschbach, Susanne - Continuities and Differences Between Photographic and Post-Photographic Mediality

Загружено:

bashevisАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

16/5/2014 Media Art Net | Photo/Byte | Photographic/Post-Photographic

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/photo_byte/photographic_post-photographic/print/ 1/12

Photo/Byte

Continuities and differences between photographic and post-photographic mediality

Susanne Holschbach

ht t p://www.medienkunst net z.de/t hemes/phot o_byt e/phot ographic_post -phot ographic/

At the end of the 1980s through the beginning of the 1990s, photo curators, art and media

theorists began to examine the significance of electronic image technology for the status and the

practice of photography. [1] The rapid permeation of digitally processed photographs in the

commercial and journalistic areas, the introduction of relatively high-performance and reasonably

priced PCs, software, scanners, printers, etc., which made electronic image processing accessible

to artists and amateurs as well, gave cause to speak of an epoch-making turning point: From the

moment of its sesquincentennial in 1989 photography was deador, more precisely, radically and

permanently displacedas was painting 150 years before. [2]

However, the focus on the difference between analog and digital media, which in the second half

of the twentieth century advanced to become the dominant difference in media history and theory,

[3] conceals their common starting point in the nineteenth century and the radical turning point

associated with the invention of photography: As the first technical imaging method, it ushered in

theradical change between old and new media. In this sense, the media theorists Marshall

McLuhan and Vilm Flusser, both of whom think in terms of generously measured eras, place

photography at the beginning of the information age and the telematic society. In his anthology

Understanding Media, [4] which was first published in 1964, McLuhan writes: Photography

was decisive in making the break between mere mechanical industrialization and the graphic age

of electronic man. In his work Ins Universum der technischen Bilder (Into the universe of

technical images), which was published 20 years after McLuhan's, Flusser establishes that

technical images are a completely new type of media, even though in many respects they may be

reminiscent of traditional images, and that they have a completely different meaning than traditional

images. In short: they are indeed about a cultural revolution. [5] Both of them see the age of the

computer as a consequence or a continuation of this photographic revolution. Following McLuhan

and Flusser in this respect, this contribution begins with a return to the fundamental qualities of

photographic mediality and their manifestation in the various ways photography is used and the

discourse surrounding it. It is only from this media-historical perspective that one can comprehend

what transformations the photographic dispositive undergoes in the course of technological change

and how these transformations affect the media function of photography.

Automatic Recording

Daguerre and Talbot regarded their inventions as a chemical and physical process by which, in

Talbot's words, natural objects may be made to delineate themselves without the aid of the artist's

pencil. [6] What is being stressed is the immediacy of the image, the absence of an artistic

rendering. The omission of this rendering, which is prone to errors, guaranteed truth to reality and

objectivity. In writings on photography in the nineteenth century, this objectivity was time and again

connected with the indifference and neutrality of photography towards its object, i.e. its referent.

The automatic photo is not selectiveit depicts all objects with the same care; it does not

distinguish between important and unimportant, worthy or unworthy of being taken.There was a

slogan used by contemporaries to move the equalizing quality of photography onto a politically

progressive horizon: All things are equal under the sun. The qualities of automatic recording

judged as positive became decisive for the use of photography for documentary purposes: in the

preservation of historical monuments; in the sciences, criminology, and medicineto name the

central areas of the nineteenth century. However, they stood in the way of the recognition of

16/5/2014 Media Art Net | Photo/Byte | Photographic/Post-Photographic

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/photo_byte/photographic_post-photographic/print/ 2/12

photography as art. This is the reason that until far into the twentieth century, reference was still

made to the creative means of photographers in order to justify their work as art. The intentional

inartistic implementation of photography in the Concept Art of the 1960s and 1970s signified a

transition in this regard: In order to deconstruct established art values, precisely those ways of using

photography were taken up that could not be brought into line with their artistic ennoblement. With

books of photographs such as Twenty-Six Gasoline Stations or Every Building n the Sunset

Strip by Ed Ruscha and Alle Kleider einer Frau (All of a woman's clothes) by Hans Peter

Feldmann, for example, these artists return to the photographic recording in the sense of a simple

list or bureaucratic registration. Concept artists mime, so to speak, different ways of using

photographysuch as e.g. scientific documentation, chronophotography, crime scene

photography, illustration, the photo report, shutter photography and in this way presentoften

ironicallycritical analyses of these usages.

While Concept artists refer to the superficial banality of photography, conceptional photography,

which appeared at about the same time as Concept Art, relies on its documentary quality, i.e. on

the reproductive output and objectivity of the photographic medium. Within this context, the return

to automatic recording means the greatest possible technical quality combined with the withdrawal

of the photographer in favor of the object (this was formulated in the introduction of the exhibition

catalogue New Topographics. Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape in a way that points

the way ahead; [7] because it exemplifies this photographic attitude, the book by Bernd and Hilla

Becher is particularly worth mentioning).

The photograph as an index

In the twentieth century, automatic recording was given an emphasis that went beyond the

objectivity of photographic depiction. In the photographic theory of the time, the characterization of

photography as a copy of nature was restated using the sign theoretical term of indexicality. [8]

Indexical signs such as the smoke of a fire, footprints in the sand and the like have a physicalone

could also say causal (cause and effect)connection to their referent. In this understanding, the

photographic image is a trace or the effect of the object that was photographed: a print of the

rays of light thrown back from an object onto a carrier material that has been made sensitive to light

with silver salt crystals. Thus the photographic depiction of an object is at the same time verification

of its existence, even if this applies to a past moment. Roland Barthes' formula for the certification

of a past present, which for him constitutes the naturethe noemaof photography, is: That's

the way it was. [9] Of course this quality especially predestines photography for its use in

investigative surveillance and the securing of criminal evidenceuses that have been adopted by

artistic photography in many ways (for instance On this site (Crime scenes) by Joel Sternfeld, or

The Shadow and lHtel by Sophie Calle). [10]

Photography's promise of reality, [11] which goes beyond realistic depiction, is based on this

physico-chemically based indexicality: because it claims to be capable of verifying reality. In doing

so, indexicality relates only to the photographic act, [12] the moment of releasing the image; all of

the other factors that lend meaning to the photographic imagechoice and choreography of the

subject, processing the print, material and discursive contextualizationare blended out in the

process.

Mechanical Reproduction

In early proto-photographic experiments, the search for a simplified process for duplicating existing

masters was equally as important as the goal of fixing the camera obscura's images. As early as the

1820s, Nipce dealt with the transfer of engravings onto lightsensitive carrier material, which was

then meant to serve as a printing plate. Talbot, whose positive/negative processprovided the

prerequisite for what was in principle the infinite duplicability of photographs, also had in mind the

production of multiplying at small expense copies of rare or unique engravings. [13] Indeed, the

reproduction of works of art and historical monuments from throughout the world advanced to one

of the most successful branches of photography in the nineteenth century. In his canonic essay The

Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction , Walter Benjamin described the resulting

consequences for the function of art as the loss of its aura: Outside of their contextreleased from

the here and nowworks of art lose their uniqueness as originals and thus their cultural value.

16/5/2014 Media Art Net | Photo/Byte | Photographic/Post-Photographic

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/photo_byte/photographic_post-photographic/print/ 3/12

Assembled in an imaginary museum [14] and disregarding their original function and integration

into a cultural context, works of different origins and of different epochs can be compared as purely

visual data (surfaces). This kind of comparison was first made possible by form analysis, thus

establishing an aesthetics based on the history of style at the end of the nineteenth century. At the

same time, however, the photographic parity of artifacts goes beyond the boundaries of

disciplinary aesthetics: Aby Warburg, who arranged photographic reproductions according to

subject in the plates of his Mnemosyne Atlas [15] , made no distinction between antique relief

and contemporary advertisement, and thus already pointed in the direction of visual studies.

The photograph as a multiple

The combination of mechanical reproduction with a mode of production based on the division of

labor made the photograph into a mass-produced article in the nineteenth century. At the same

time, however, the trouble-free duplicatability of the photograph as a product became a problem:

The legal dispute over the copyright of photographs starts out from commercial photography, which

needed to protect itself from the exploitation of its productse.g. portraits of prominent figures or

stereoscopic cards. [16]

However, the quality of the photograph as a copy implies more than just the mechanical

reproduction of existing imagesbe it in the form of prints from a negative or rephotographing

image masters. In connection with Walter Benjamin's essay on the work of art, the art theorist

Rosalind Krauss sets out thatphotography is a medium that directly produces copies, i.e. a

medium in which the copies exist without an original. [17] According to this understanding of

photography, even the negative of a nature scene is already a copy: a reproduction of the depicted

subject. [18] For Krauss, the explosive force of this photographic quality for art of the modern age

(and of art reproduction in the twentieth century in general) lies in the fact that it undermines the

concept of originality itself. [19] It was above all the photographic activity of postmodernism

[20] that consciously took up this quality in order to deconstruct notions of (creative) authorship

and the autonomy of works of art. In this way, the artist Sherrie Levine appropriated [21] icons

from artistic photography simply by taking her own photographs of them (e.g. in the series After

Walker Evans ), and in doing so attacked the auralization of photography, which had accompanied

its musealization in the 1970s and 1980s. [22]

Mass Medium Avant la Lettre

Mechanical reproduction created the condition for the development of photography into a mass

medium, whose hegemony was not forced open until the 1950s and 1960s with the advent of

television. [23] It began in the 1850s with the distribution of portraits of prominent figures and

stereographs, and experienced a further thrust in the 1880s through the beginnings of shutter

photography and the illustrated press.

Facial society

In 1854 the photographer Alphonse-Eugene Disdri patented a process that allowed taking several

portraits in succession on one plate. He rationalized and reduced the cost of portrait photography in

this way, which consequently experienced a tremendous boom. [24] The small-format carte de

visite, the term for the cut-to-size portrait cards, were used less as a personal keepsake than for

communicative exchange. Portraits of prominent figures, whose spectrum ranged from ruling

families, writers, musicians, scientists and actors to demimondes, were especially popular.

Collecting and looking at the cards became a parlor game that leveled off social hierarchies by

juxtapositioning images that had been choreographed in a similar way. The portrait of prominent

figuresanticipated the modern portrait of stars and was thus incipient of a facial society, in which

the faces of politicians, generals, managers, athletes, artists or products advanced to portraits of

stars and brand names, to logos with public appeal. [25]

Modern observer

In 1851, Sir David Brewster introduced a transportable viewing device at the London World's Fair

that allowed merging together slightly displaced paired photographs to create one image, which

appeared to be three-dimensional. [26] Brewster's stereoscope became a huge success, and soon

thereafter thousands of greedy pairs of eyes bent over the stereoscope's openings like over the

16/5/2014 Media Art Net | Photo/Byte | Photographic/Post-Photographic

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/photo_byte/photographic_post-photographic/print/ 4/12

skylight to infinity. [27] The stereograms [28] mass produced in the period following the

stereoscope's introduction for the most part showed historical monuments, landscapes and urban

scenestourist views from countries near and far that could be quasi virtually traveled via the

stereoscope. In addition, they allowed the middle class a visual appropriation of foreign countries

and cultures, which was already taking place through colonization. Contemporary descriptions [29]

verify that the visual desire that arises when viewing stereoscopic photographs lay in the feeling of

immersion: [30] The outside world disappears in favor of the space of an image, which is

experienced as a real space. In its linking of apparatus and the physiology of sight, stereoscopy is

part of a modernization of vision [31] that according to the art historian Jonathan Crary is

associated with a new concept of the observer. The exploration of the physiology of human vision

driven forward in the nineteenth century came to the conclusion that the observer is in no way

merely a passive recipient of images of the outside world, rather the images are created in the visual

process. Optical toys such as the phenacistiscope, the zootrope, [32] and of course the

stereoscope represent the new insight that was being gained into vision (such as the after-image

effect or binocularity). Besides their being a form of entertainment, at the same time they trained

perception, which was being subjected to new demands in the age of industrialization.

Consumer as producerProducer as consumer

Photography, however, not only produces the modern consumers of images, but also empowers

them to produce their own images. In the beginning, photography as a private pastime was reserved

for a small class as it required money and above all time to learn the skills necessary for taking and

developing photos. At the end of the 1880s, the creation of the hand camera and roll film created

the conditions for shutter photography, which no longer required knowledge of the photographic

process. The famous slogan You press the button, we do the rest, with which the Kodak

company advertised its first cameras, is an accurate indication of the dependence of the lay

photographer on the photographic industry: S/he had become a producer of photographs only in

the sense of being a consumer of its products and services.

An essential part of the practices of private photography is the photograph's quality as an index

(refer to the section on The photograph as an index, above): Biographical occurrences are

recorded and authenticated at the same (It actually happened). Shutter photography, as analyzed

by the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu in the 1960s, became primarily an agent of the cohesion of the

family, for which it both produced verification and at the same time created. [33] For this reason,

the new practices of shutter photography that arose in the course of digitalization are to be viewed

in connection with the dissolution of traditional family structures and the forms of relationships and

communication that take their place. [34]

The photograph in the media environment

The history of photographic intermedialitythe connection of photo/book, text/imagebegan with

the publication of Talbot's book The Pencil of Nature. [35] However, prior to the 1880s this

connection was associated with a small number of copies, as photographs were either glued into

books or produced using printing processes that required a high degree of craftsmanship. For the

mass circulation of illustrated magazines and newspapers, photographs first had to be transferred

onto wood engravings with the arrival inthe 1880s of the screening process of autotypy, they

could then be transferred mechanically to a printing plate and printed together with the copy. In the

course of the illustrated magazine boom in the first half of the twentieth century, the photo report

and the documentary photo essay emerged as specific forms of the combination of photo series

with text contributions. The success of the mass press in the 1920s was also accompanied by

criticism thereof: Siegfried Kracauer, for instance, implored the danger of substituting the

experience of reality with the world of media. In his words: The public sees the world in

magazines, and magazines prevent perception of the world. [36] This criticism would later be

formulated in a whole range of variations. [37] In the media environment of the illustrated press,

photographs are assigned meaning through captions and text contributions; text contributions are

verified through photos: This intermedial configuration is decisive for the reception of photographic

images. The switchover from offset printing to computer-based desktop publishing required the

conversion of the photographic image into digital datadigitalization thus represents a logical

16/5/2014 Media Art Net | Photo/Byte | Photographic/Post-Photographic

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/photo_byte/photographic_post-photographic/print/ 5/12

further development for photography in the media environment. If one looks back at the history of

how it was used in the mass media, which was only briefly touched on here, the most recent

technological change in photography, i.e. its connection to electronic media, represents nothing

more than an extension of precisely these media functions and their being made more effective. It

was not until the advent of the Internet that the options aired by the early phototexts of a non-site-

specific availability and an unrestricted circulation of images could actually be redeemed. In doing

so, this continuation of objectives and applications, which from the beginning were associated with

photography, oscillates between democratization and commercialization, between the ideal of a

general accessibility of media technology and the problem of its dependence on the mechanisms of

the economy and industrial production.

Digitalization

The technological transformation of photography isa natural consequence of its intermediality. In the

same way the screening process constituted the condition for its integration into the medium of mass

printing, its digitalization is the condition for its implementation into the universal medium of the

computer. The substitution of the analog through the digitalor more precisely: analogo- numeric

process took plate in several stages and on different technological levels: that of the recording,

the processing, and the transmission of data.

From a media-archeological perspective, the screening of photographic masters for the purpose

of their automatic transfer onto printing plates can already be described as a form of digitalization:

The continuous tonal values of a photochemical master are broken down into discreet units, i.e.

black dots and white blanks. [38] This breaking down is at the same time the condition for coupling

photography with electric telegraphy. [39] , on the media historical connection between

photography and telegraphy. In order to be able to transmit photographic images per telegraph, the

image to be sent is screened into fields, which are then assigned discreet signs according to their

various brightness attributes. These signs then travel through the channel, and on the receiving end

they are again assigned the corresponding dots, which allows recombination of the image. In their

technical arrangement, screening and image-telegraphic scanning anticipate the modern scanning

process: however they differ on an essential point: During the modern scanning process, values are

stored and can be further processed. By scanning them, analog photos are carried over into the

computer and thus made accessible to mathematical operations: The condition for image processing

was created. Electronic image recording was not made possible for another 20 years: through the

CCD (charged coupled device) chip, which was patented in 1974 and consists of a lattice-like

arrangement of light-sensitive elements via which light can be converted into an electrical charge.

This, on the other hand, can be measured and subsequently digitalized, i.e. converted into bit

patterns. [40] Although photographs are in this way made directly (without going through a

scanner) available to processing or transmission by the computer, their creation remains bound to

the analog transfer of lightquantities: The actual digitalization occurs only through the measuring out

of these light values and their code conversion into numerical values (bits). This distinguishes

analogo-numerical photography (mentioned above) from images that have completely generated by

a computer and whose look is only adapted to photographic (or cinematic) aesthetics. [41]

In view of the use of the photograph by the mass media, the advantages of its digitalization are

perfectly apparent: It can be delivered immediately (e.g. as a press photo) and made available for

prompt processing (e.g. for the layout of a magazine); in addition, it can be directly distributed

throughout the world via the Internet.

Digital Montage

Apart from their use in military and scientific contexts, [42] the possibilities of digital image

processing and analog-digital image recording (beginning with the so-called video still camera

introduced in 1981) were first used in the areas of magazines and the press. Until way into the

1980s, digital image processing remained a high-tech option only large agencies could affordthe

pyramids, for example, were moved closer together by means of Scitex rendering for the February

1982 cover of National Geographic, who plays an exemplary role in the debate over

digitalization. The introduction of the personal computer and the opening of the Internet, however,

also shaped the participatory and (inter)active potential of the configuration of photography, the

16/5/2014 Media Art Net | Photo/Byte | Photographic/Post-Photographic

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/photo_byte/photographic_post-photographic/print/ 6/12

video, and computer processing: Multi-media desktop publishing is now no longer only available

to the mass media, but also political groups, citizens' groups, artistsi.e. anyone who has anything

to communicate. It is in this spirit that in the exhibition catalogue Digital Photography: Captured

Images, Volatile Memory, New Montage, Jim Pomeroy takes up a slogan of the leftwing media

avant-garde of the 1930s: Every receiver can become a transmitter. [43] The exhibition, which in

1988 was presumably the first to take up the subject of digital photography within the context of

art, also makes reference to the avant-garde of the 1920s and 1930s in another respect. The

image/text works by the artists, which were presented primarily in the simple form of computer

printouts, are compared in their method with themontage concepts of Dadaism, Surrealism and

Constructivism: [44] In the same way the analog collages consist of fragmentary photos and texts

of different origins, the computer works also disclose their construction principlesthe contrastive

superimposition of heterogeneous material. In doing so, the low-tech optics of coarse, mosaic-like

pixel resolution, visible video lines, of saw-tooth distortions and transmission errors (cf. e.g. The

Noise Factor (1988) by George Legrady) are set against the smooth, high-tech image

manipulation by the large photo agencies. The noise of the data not only prevents illusionistic

effectsit shows, so to speak, the medium computer at work.

With the introduction of the image processing software Photoshop, a further form of digital

montage appeared. Like the large magazines, artists can now process photographs without their

intervention being directly visible in the result. Works such as Faces #112 (1998) by Vibeke

Tandberg, Affaires infinies by Bettina Hoffmann (1997), or Le jeu de la rgle (1992ff.) by

Alain Fleischer are based on thestill assumedreception of photographic images as

representations of a real (or a staged) occurrence. The irritation begins at second glance or in the

course of the series of images; it lifts the naive perception of the scene and thus opens up a further

horizon of meaning. [45]

Digital Trouble

The welcoming of the creative potential and the multi-media connectability of a digitalized

photograph is eclipsed by a critical discourse, which above all points out the potential for

manipulation and forgery of all kinds in electronic image processing. For this reason, it is not

coincidental that the debate over the loss of the credibility of photographic images ignites in the area

of photojournalism. The authority of the classical photo report is particularly bound to photographic

indexicality, in which the That's how it was of the object being shown is substantiated by the

photographer's I was there, and vice versa. Digitalization severs the indexical connection between

the photograph and the object of the photograph, and at the same time it expropriates the

photographer in that the photo is now accessible to any form ofprocessing. Photographer

associations fear that the simplification of the creative editing of photographic masters will

gradually disable the difference between authentic and manipulated photos and thus in the end

completely undermine the belief in the documentary value of photography. [46] The theoretical

contributions that look into this aspect of digitalization necessarily return to the long history of

forging images for the specific purpose of deception and to the classical processes of image/text

layout that confer meaning. [47] Above and beyond that, authors such as Martha Rosler, who as an

artist examined the conditions of a critical practice of documentary photography, emphasize the

fundamental dependence of photography and its documentary function on social, political and

discursive contexts. [48] These aspects allow relativizing the meaning of the technological

transformation from analog to digital photography and shifting to the more fundamental question of

the changes in the use of media by society.

However, the apprehension that the loss of photographic indexicality triggers off goes beyond the

suspicion of deception: It is linked to the idea of the fading away of any reference to external reality

and, as a result, the individual's power of judgement. [49] This is where the debate over the death

of photography converges with that over the virtualization of human experience, which was

conducted in the 1990s in connection with computer games and increasing use of the Internet, but

also in conjunction with the media adaptation of the first Gulf War in 1990/1991. The Gulf War

gained exemplary meaning in two respects: It stands for a new dimension in the

visiontechnological distancing of the fighter pilot from his or her target and for a particularly

16/5/2014 Media Art Net | Photo/Byte | Photographic/Post-Photographic

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/photo_byte/photographic_post-photographic/print/ 7/12

restrictive image policy on the part of American warfare. In this war, writes Mitchell in The

Reconfigured Eye, which was published a year after the first Gulf War ended, satellite imaging

systems did much of the spying and scouting. Laser-guided bombs had nose-cone video cameras;

pilots and tank commanders became cyborgs inseparable from elaborate visual prostheses that

enabled them to see ghostly-green, digitally enhanced images of darkened battlefields. There was

no Mathew Brady to show us the bodies on the ground, no RobertCapa to confront us with the

human reality of a bullet through the head. Instead, the folks back home were fed carefully selected,

electronically captured, sometimes digitally processed images of distant and impersonal destruction.

Slaughter became a video game: death imitated art. [50] This quote is typical for the moral charge

that the discussion over the photographic and post-photographic truth gains through this context:

Electronic image technology stands for the view from abovethe general's view, who only has his

or her sights set on anonymous targetswhile classical photography stands for the view from

belowfor the suffering and death of the individual as the human reality of war. In contrast, the

photographic work Martha Rosler, which Sophie Ristelhuber began after the end of the first Gulf

War, relies on a third perspective. The condition of her fragmentary tracking is the conviction that

the truth of a war cannot in principle be mediated through images: neither through photographs of

its victims, nor through cockpit displays.

In the exhibition Photography after Photography the focus is on a further context of digital

trouble. A number of the works it included tested the new tools (Photoshop, Paintbox and the like)

on the human body, on the human face: Bodies were deformed and hybridized (Inez van

Lamsweerde), constructed (Keith Cottingham's Fictitious Portraits from 1992); faces were

folded (Valie Export's o.T. from 1989), robbed of their countenance (Anthony Aziz and

Sammy Cucher's Dystopia from 1994), their individuality (Nancy Burson's series Chimren

since 1982). [51] It is at the interface of the human body that the post-photographic discourse

eclipses that on the posthuman, [52] in which digital processing stands so to speak metaphorically

for the ubiquitous variability of the human body through cosmetic surgery and the genetic

technology of the future. However, whereas talk of the posthuman drives forward the imagining of

a new design, a new model of the human in more of an affirmative gesture, [53] the artistic works

cited above visualize the apprehension triggered off by the feeling of uncertainty with respect to our

traditional ideas about the similarity and identity of the subject55 (confirmed by the traditional

photographic portrait in its reference to an individual physiognomy, a distinctbody), i.e. they make

dystopic reference to what is possibly a changing human form.

Unstable Images

The digital image technologies have literally eliminated a photographic model of representation, the

spatial-temporal bond of a light-sensitive carrier material to a spatial-temporal

constellation/figuration in front of the camera, and put it up for debate. The very foundation of the

ontology of the photographic image as conceived by the likes of Kracauer and Benjamin, and later

by Bazin and Barthes, has been shaken. In view of the binary coding of the photographic

contingency, even the index theory, which follows Charles S. Pierce, now appears to be obsolete.

[54] As explained above, the indexicality of photography substantiated its credibility as evidence of

something that had actually been there in front of the camera. Even the knowledge that a photo

does not gain meaning until it has been contextualized has not led us to fundamentally doubt this

credibitility. Today, the reception of photographs is beginning to change: We now start off by

doubting its promise of reality. The digital/ized photograph is a dubitative image: [55] ). Its

authenticity as a direct photo and the associated evidential value can now only be established

through external authorization. [56] For this reason, a society whose communication rests primarily

on digital (image) media requires a well-founded, strictly arranged media policy59 those who

analyze the technological change from analog to digital photography are united in this conclusion.

From a technological point of view, the That's how it was of analog photography is based on

the irreversibility of the exposed material; [57] the digital photo, in contrast, is characterized by its

immanent variability: [58] The digital photograph is fundamentally reversible (it can immediately

be deleted); its output as an image is only one of the possible manifestations of the data stored in

binary form. [59]

16/5/2014 Media Art Net | Photo/Byte | Photographic/Post-Photographic

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/photo_byte/photographic_post-photographic/print/ 8/12

A further factor in the instability of digital photographs is their dependence on hardware and

software. Their visual appearance changes along with the file format, the screen configuration,

through compression, conversion, etc. The greatest problem, however, is caused by the continuous

furtherdevelopment of computer systems: The change from one system to the next but one can

make image data unreadable and thus inaccessible. And so there is a rift between potential digital

endurance and mechanical impermanence, [60] which can only be bridged through continuous

activity: Data stocks have to be adapted to each of the new formats in time with the new

developments by the computer industry; they have to be put onto each of the new storage media

before they only become interesting to media archeologists. [61]

According to an expert on image databases, [d]igitalization projects necessitate constant

reacting and acting, because what is digital does not rest, just as overall technological development

does not rest. [62] The professional condition for operators of image databases also affects both

artists who work with digital media as well as each and every lay photographer: While the best way

to slow down the physico-chemical process of the decay of photographs is to protect them from

being accessed (by allowing them to be exposed to as little light as possible and storing negatives in

underground freezer depots), digital photos are only preserved through their useif one ignores

them, the information stored on them will also be lost for future generations. [63]

It is quite possible that the apprehension about the instability of digital photographs and the

efforts to secure their longevity is nothing more than the reflex of a traditional (Old European) self-

conception of culture. [t]ransatlantic media cultures have long since accentuated the technologies

of multi-media and space-seizing transmissionthe dataflows in the Internet. [64] In the sense of

an information society, instability can be regarded as a positive value: It stands for dynamic

transmission, unobstructed circulation, and for communication that is not bound to real space; it

stands for virtuality as the ability to experience what is possible. In contrast, analog photography

hangs on to what is past; its gesture is a clingingto a state of visible reality, to public and private

occurrences, to fleeting moments in everyday life. Its great subjects, the topography of urban and

suburban life and the visualization of biography and identity are (or were) being sustained by a

concept of remembrance that binds historical tradition andpersonal memory to material evidence.

Fifteen years after the beginning of the debate over the end of photography one can establish that

the radical change from analog to digital technology has not invalidated the notions of

representation, identity and memory associated with the photographic dispositiverather it

contributes to a destabilization of these notions. In the environment of electronic media, digital

photography constitutes a threshold phenomenon: It is located so to speak at the transition from old

storage media to new communication media and their paradigms.

[1] Cf. Marnie Gillett/Paul Berger (eds.), Digital Photography: Captured Images, Volatile Memory,

New Montage, exhibition catalogue, SF Camerawork, San Francisco, 1988; Fred Ritchin, In Our

Own Image. The Coming Revolution in Photography, New York, 1990; William J. Mitchell, The

Reconfigured Eye. Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era, Cambridge, MA/London, 1992;

Paul Wombell (ed.), PhotoVideo. Photography in the Age of the Computer, exhibition catalogue,

London, 1991; Martin Lister (ed.), The Photographic Image in Digital Culture, London/New York,

1995; Stefan Iglhaut/Hubertus von Amelunxen/Alexis Cassel (eds.), Photography after

Photography, Basel/London, 1996.

[2] William J. Mitchell, The Reconfigured Eye. Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era,

Cambridge, MA/London, 1992, p. 20.

[3] Cf. Jens Schrter, Analog/DigitalOpposition oder Kontinuum? in Jens Schrter/Alexander

Bhnke, Analog/Digital. Opposition oder Kontinuum. Zur Theorie und Geschichte einer

Unterscheidung, Bielefeld, 2004, pp. 730, here pp. 8f. In his introduction, Schrter deals with the

different levels of the difference between analog and digital, which are used with respect to

technology and media history as well as symbol theory.

[4] Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media. The Extensions of Man, Cambridge, MA, 1964.

[5] Vilm Flusser, Ins Universum der technischen Bilder, Gttingen, 1992, p. 11.

[6] William Henry Fox Talbot, Some Account of the Art of photogenic Drawing or the Process by

which natural objects may be made to delineate themselves without the aid of the artists pencil, in

16/5/2014 Media Art Net | Photo/Byte | Photographic/Post-Photographic

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/photo_byte/photographic_post-photographic/print/ 9/12

The Athenaeum, London, Feb. 9, 1893.

[7] William Jenkins (ed.), New Topographics. Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape,

exhibition catalogue, International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, Rochester,

1975.

[8] According to Charles P. Pierce, sign theory distinguishes three basic forms of the relationship

between the sign and its referent: the symbolic, which is produced through convention; the iconic,

which is based on a similarity between the sign and its object; and the indexical, which requires a

physical connection.

[9] Roland Barthes, La chambre claire. Note sur la photographie, Paris, 1980, English as: Camera

Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard, New York, 1981.

[10] On the subject of crime scene photography, cf. in particular Christine Karallus,

Staatsanwlte, Kriminalisten und Detektive, in Kunstforum International, Themenheft:

Choreographie der Gewalt, Jan.Mar. 2001, pp. 132- 143; and Christine Karallus, Etwas in

Augenschein nehmen. Der Tatort und seine fotografische Identifizierung um 1900, in Charles

Grivel et al. (eds.), Die Eroberung der Bilder. Photographie in Buch und Presse 1816 1914,

Munich, 2003, pp. 141155.

[11] Cf. Wirklich wahr. Realittsversprechen von Fotografie, exhibition catalogue,

Ruhrlandmuseum Essen, Ostfildern, 2004. On the agenda of photography's promise of reality within

the context of art cf. Susanne Holschbach, Die Wiederkehr des Wirklichen? Pop(ulre)-

Fotografie im Kunstkontext der 90er Jahre, in Sigrid Schade/Georg Christoph Tholen (eds.),

Konfigurationen zwischen Kunst und Medien, Munich, 1999, pp. 400 412, and the net discussion

initiated by Kathrin Peters on Wirklichkeitsfotografie

[12] Philippe Dubois, LActe photographique, Paris/Brussels, 1983.

[13] Henry Fox Talbot cited in Helmut Gernsheim, History of Photography. From the Camera

Obscura to the Beginning of the Modern Era, London, 1969, p. 78.

[14] This is the term used by Andr Malraux, French minister for the arts and culture under de

Gaulles, to describe his concept of a museum that consists solely of photographic reproductions.

Cf. the contribution by Jens Schrter Archivepost/photographic.

[15] Cf. Rudolf Frieling's contribution The Archive, the Media, the Map and the Text, in the

module Mapping and Text.

[16] This, on the other hand, could only be achieved through recognizing that photographs are also

works produced by a creative subject. Thus of all people, it was the commercial photographers in

the nineteenth century who paved the way for the ennoblement of photography as art. This

historical example also shows that it was the industrial producers (in this case commercial studios

and photo publishers) and not artists who profited most from copyright. Cf. John Tagg, A Means

of Surveillance. The Photograph as Evidence in Law, in John Tagg, The Burden of

Representation. Essays on Photographies and Histories, Amherst, 1988, pp. 66102.

[17] Rosalind Krauss, The Ministry of Fate, in Denis Hollier (ed.), A New History of French

Literature, Cambridge, MA, 1989, pp. 10001006. Also refer to Rosalind Krauss, A Note on

Photography and the Simulacral, October, 31, Winter 1984, pp. 4968. Krauss cites the

Untitled Film Stills by Cindy Sherman as an example of copies without an original.

[18] This means that the status of being an original at best befits the real landscape, the real

object to which the photograph refers.

[19] For Rosalind Krauss' understanding of photography as a dominant medium in art production in

the twentieth century, refer to Herta Wolf's introduction to the collection of essays by Rosalind

Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-garde and Other Modernist Myth, Cambridge, MA, 1986.

[20] Cf. Douglas Crimp, The Photographic Activity of Postmodernism, in Douglas Crimp, On

the Museums Ruins, Cambridge, MA, 1993 and Douglas Crimp, Pictures, in Tamara Horkov

et al. (eds.), Image:/images. Positionen zur zeitgenssischen Fotografie, Vienna, 2001, pp. 121

138.

[21] Strategies of appropriation such as Sherrie Levine's re-photographs inspired the coinage of

term Appropriation Art.

[22] Richard Prince's re-photographs of advertising photos, which he heightens to images through

their isolation and enlargement, function in the reverse direction.

16/5/2014 Media Art Net | Photo/Byte | Photographic/Post-Photographic

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/photo_byte/photographic_post-photographic/print/ 10/12

[23] This first gave rise to the term mass media. Cf. Dieter Daniels' text TelevisionArt or Anti-

art? in the module Survey of Media Art.

[24] Cf. Elizabeth Anne McCauley, A.A.E. Disdri and the Carte de Visite Portrait Photograph,

New Haven/London, 1984, and Elizabeth Anne McCauley, Industrial Madness. Commercial

Photography in Paris 18481871, New Haven/London, 1993.

[25] Cf. Thomas Macho, Vision und Visage. berlegungen zur Faszinationsgeschichte der

Medien, in Wolfgang Mller-Funk/Hans Ulrich Reck (eds.), Inszenierte Imagination. Beitrge zu

einer historischen Anthropologie der Medien, Vienna/New York, 1997, pp. 87108, here pp. 88f.;

and Thomas Macho, Das prominente Gesicht. Vom Face-to-Face zum Interface, in Manfred

Faler (ed.), Alle mglichen Welten. Virtuelle Realitt. Wahrnehmung. Ethik der Kommunikation,

Munich, 1999, pp. 121136.

[26] Brewster developed his stereoscope on the basis of an apparatus that had been constructed

by the English physicist to illustrate binocular vision.

[27] Charles Baudelaire made this mocking remark in his famous polemic work The Modern

Public and Photography, a first criticism of the commonplace taste of the media recipient (in

contrast to the art recipient): Charles Baudelaire, Der Salon von 1859, in Charles Baudelaire,

Der Knstler und das moderne Leben. Essays, Salons, Intime Tagebcher, Henry Schumann

(ed.), Leipzig, 1990, pp. 199229, here p. 206; cf. Dieter Daniels, Kunst als Sendung. Von der

Telegrafie zum Internet, Munich, 2002, in particular the section on Modernitt und Medien

(Modernity and media), pp. 162176.

[28] Only three years later, the London Stereoscopic Company, which was founded in 1854, had a

selection of 100,000 different stereograms. In 1864 approximately five million stereograms were

produced in the United States.

[29] For instance that by Oliver Wendell Holmes in his article The Stereoscope and The

Stereograph, Atlantic Monthly, 3, June 1859, pp. 738748: The mind feels its way into the very

depths of the picture. The scraggy branches of a tree in the foreground run out at us as if they

would scratch our eyes out. The elbow of a figure stands forth so as to make us almost

uncomfortable. Then there is such a frightful amount of detail, that we have the same sense of infinite

complexity which Nature gives us.

[30] Cf. the text Immersion and Interaction by Oliver Grau in the module Survey of Media Art.

[31] Jonathan Crary, Modernizing Vision, in Hal Foster (ed.), Vision and Visuality. Discussions

in Contemporary Culture, Seattle, 1988, pp. 2944.

[32] The phenacistiscope and the zootrope are first and foremost still known as precursors to

cinematography. They allow individual images to merge together to a single sequence of movement.

[33] Cf. Pierre Bourdieu, Un art moyen, Paris, 1965, German as: Eine illegitime Kunst,

Frankfurt/Main, 1981.

[34] Cf. the text Instant Images by Kathrin Peters.

[35] William Henry Fox Talbot, The Pencil of Nature, London, 1844.

[36] Siegfried Kracauer, Die Photographie, Siegfried Kracauer, Der verbotene Blick.

Beobachtungen, Analysen, Kritiken, Leipzig, 1992, p. 198.

[37] For instance by Susan Sontag in her book On Photography (New York, 1977), in which she

makes reference to Plato's Allegory of the Cave.

[38] This is one of many ways to telegraph images, the so-called statistical method of temporary

clichs. On the methods of image telegraphy from a media-archeological perspective cf. Birgit

Schneider/Peter Berz, Bildtexturen. Punkte Zeilen Spalten; Teil II: Bildtelegraphie, in: Sabine

Flach/Georg Christoph Tholen (eds.), Intervalle 5 Mimetische Differenzen. Der Spielraum der

Medien zwischen Abbildung und Nachbildung, Kassel, 2002, pp. 202220.

[39] Cf. Dieter Daniels, Kunst als Sendung. Von der Telegrafie zum Internet, Munich, 2002, pp.

49 Cf. Hubertus von Amelunxen, Photography after Photography, in Stefan Iglhaut/Hubertus

von Amelunxen/Alexis Cassel (eds.), Photography after Photography, Basel/London, 1996, pp.

116123.

[40] The epistemological prerequisites for this technology lie in quantum mechanics, the

technological prerequisites in semiconductor physics. Cf. Wolfgang Hagen, Die Entropie der

Fotografie. Skizzen zu einer Genealogie der digital-elektronischen Aufzeichnung, in Herta Wolf

16/5/2014 Media Art Net | Photo/Byte | Photographic/Post-Photographic

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/photo_byte/photographic_post-photographic/print/ 11/12

(ed.), Paradigma Fotografie. Fotokritik am Ende des fotografischen Zeitalters, Frankfurt/Main,

2002, pp. 195235.

[41] Cf. Friedrich Kittler, Computergrafik. Eine halbtechnische Einfhrung, in Herta Wolf (ed.),

Paradigma Fotografie. Fotokritik am Ende des fotografischen Zeitalters, Frankfurt/Main, 2002, pp.

178194, on the process of computer-generated images.

[42] The processes of digital photography were initially developed for these contexts. Before the

commercialization of computer technology they could only be implemented there. Cf. Jens

Schrter, Eine kurze Geschichte der digitalen Fotografie, in Verwandlungen durch Licht.

Fotografieren in Museen & Archiven & Bibliotheken, Rundbrief Fotografie, special issue 6,

Dresden, 2000, pp. 249257.

[43] Jim Pomeroy in Marnie Gillett/Paul Berger (eds.), Digital Photography: Captured Images,

Volatile Memory, New Montage, exhibition catalogue, SF Camerawork, San Francisco, 1988, p.

2: Since digital information is easily copied by modem transfer, disk duplification, and other

methods, computer images are equally adaptable for mass media publication or tiny, samizdat runs

anyone with a compatible computer can print-out the material. Every receiver becomes a press.

[44] In this connection also refer to the series Plakate (1997) by Thomas Ruff, which is

reminiscent of John Heartfield's collages.

[45] On this subject refer to the text by Anette Hsch Artistic Concepts at the Crossing from

Analog to Digital Photography.

[46] This would mean the devaluation of their work. Karin E. Becker undertakes a differentiated

analysis of the professional examination of new image technologies using the monthly journal News

Photographer, the official publication of the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA), as

an example: Karin E. Becker, To Control Our Image. Photojournalists Meeting New

Technology, in Media, Culture and Society, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 375391, reprinted in Paul

Wombell (ed.), PhotoVideo. Photography in the Age of the Computer, exhibition catalogue,

London, 1991, pp. 1631.

[47] Cf. Ritchin, op.cit.

[48] Martha Rosler, Bildsimulation, Computersimulation: einige berlegungen (1988, 1995), in

Hubertus von Amelunxen (ed.), Theorien der Fotografie Bd. IV, 19801995, Munich, 2000, pp.

129170.

[49] Cf. e.g. Fred Ritchin, The End of Photography as we have known it, in Paul Wombell (ed.),

PhotoVideo. Photography in the Age of the Computer, exhibition catalogue, London, 1991, pp. 8

15, here p. 15: There is nothing more real than anything else. Into the societal vacuum comes

power, both overt and covert, determining truth. Logic, prediction, and specificity are concepts

which are being devalued, replaced by a sense of overwhelming chaos. The title of Jens Schrter's

text, Das Ende der Welt. Analoge vs. Digitale Bildermehr oder weniger Realitt? (in Jens

Schrter/Alexander Bhnke, Analog/Digital. Opposition oder Kontinuum. Zur Theorie und

Geschichte einer Unterscheidung, Bielefeld, 2004, pp. 335354) also plays on the fear of the loss

of reality.

[50] William J. Mitchell, The Reconfigured Eye. Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era,

Cambridge, MA/London, 1992, p. 13.

[51] Also refer to the text by Anette Hsch, Artistic Concepts Linked to the Transition from

Analog to Digital Photography.

[52] Cf. the exhibition catalogue PostHuman. Neue Formen der Figuration in der Zeitgenssischen

Kunst, Deichtorhallen, Hamburg, 1993.

[53] Refer to the contribution by Verena Kuni, Mythical Bodies I, in particular the section

Stories of creation, revisited in the module Cyborg Bodies.

[54] Hubertus von Amelunxen, Photography after Photography, in Stefan Iglhaut/Hubertus von

Amelunxen/Alexis Cassel (eds.), Photography after Photography, Basel/London, 1996, p. 117.

[55] Peter Lunenfeld introduced the term dubitative image (Cf. Peter Lunenfeld, Digital

Photography: The Dubitative Image, in idem, Snap to Grid. A Users Guide to Digital Arts,

Media, and Cultures, Cambridge, MA, 2000, pp. 55 Cf. Wolfgang Hagen, Die Entropie der

Fotografie. Skizzen zu einer Genealogie der digital-elektronischen Aufzeichnung, in Herta Wolf

(ed.), Paradigma Fotografie. Fotokritik am Ende des fotografischen Zeitalters, Frankfurt/Main,

16/5/2014 Media Art Net | Photo/Byte | Photographic/Post-Photographic

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/photo_byte/photographic_post-photographic/print/ 12/12

2002, p. 253.

[56] I.e. through the credibility of the source or through an electronic watermark that seals the state

of the photograph before any further processing.

[57] Cf. Wolfgang Hagen, Die Entropie der Fotografie. Skizzen zu einer Genealogie der digital-

elektronischen Aufzeichnung, in: Herta Wolf (ed.), Paradigma Fotografie. Fotokritik am Ende des

fotografischen Zeitalters, Frankfurt/Main, 2002, p. 233.

[58] This is a term used by Peter Lunenfeld, in Herta Wolf (ed.), Paradigma Fotografie. Fotokritik

am Ende des fotografischen Zeitalters, Frankfurt/Main, 2002, p. 165.

[59] In the exhibition Photography after Photography, a number of works were shown that are

based on this principle ability of digital data to be translated. Cf. in particular Andreas Mller-

Pohle, Digitale Partituren (nach Nicphore Nipce) (English as: Digital Scores (after Nicphore

Nipce) 19951998) and George Legrady, Equivalents II (1993).

[60] My thanks to Dieter Daniels for this formulation.

[61] Refer to Jeff Rothenberg's Digital Preservation Summary, which lists the various factors

relating to mechanical impermanence and countermeasures to preserve digital artifacts. Rothenberg

sees little reason to be optimistic about the ability to pass on digital archives. (Jeff Rothenberg,

Digital Preservation Summary, Apr. 4, 2003).

[62] Kathryn Pfenniger, Bildarchiv digital, Rundbrief Fotografie, special issue 7, Esslingen, 2001, p.

10.

[63] The age of digitalization will not leave any forgotten treasures in the attic, rather at most

computer scrap.

[64] According to Wolfgang Ernst in a text on the effects of media change on the paradigm of the

archive. He predicts that the twenty-first century will be beyond the archives. In contrast, holding

on to the archive in a traditional sense (for the preservation and safeguarding of cultural assets)

would mean not mobilizing archives in the sense of digital spaces, rather preserving them as a

media-conservative counterweight in their simple mechanics in comparison with electronic

information. Wolfgang Ernst, Archive im bergang, in Interarchive. Archivarische Praktiken und

Handlungsrume im zeitgenssischen Kunstfeld, Cologne, 2002, pp. 137146, here p. 137. Refer

to the texts Beyond the Archive: Bitmapping by Wolfgang Ernst and The Archive, the Media,

the Map and the Text by Rudolf Frieling in the module Mapping and Text.

Media Art Net 2004

Вам также может понравиться

- Photography in Latin America: Images and Identities Across Time and SpaceОт EverandPhotography in Latin America: Images and Identities Across Time and SpaceGisela Cánepa KochОценок пока нет

- Hubertus v. Amelunxen-Photography After PhotographyДокумент7 страницHubertus v. Amelunxen-Photography After PhotographyAdriana Miranda100% (1)

- Art and Its Relationship With TechnologyДокумент16 страницArt and Its Relationship With TechnologyLily FakhreddineОценок пока нет

- 00 MarienIntroChapOneДокумент27 страниц00 MarienIntroChapOneXochitl GarcíaОценок пока нет

- Screen Culture and the Social Question, 1880–1914От EverandScreen Culture and the Social Question, 1880–1914Ludwig Vogl-BienekОценок пока нет

- Matthew S Witkovsky The Unfixed PhotographyДокумент13 страницMatthew S Witkovsky The Unfixed PhotographyCarlos Henrique Siqueira100% (1)

- VisioPhoto PDFДокумент32 страницыVisioPhoto PDFR DОценок пока нет

- Thedevelopmentofaphotographicaesthetic inOJADДокумент13 страницThedevelopmentofaphotographicaesthetic inOJADDAVID SANTIAGO AGUIRRE CANOОценок пока нет

- Between Infrared and Ultraviolet Some As PDFДокумент4 страницыBetween Infrared and Ultraviolet Some As PDFRodrigo AlcocerОценок пока нет

- Artificial Generation: Photogenic French Literature and the Prehistory of Cinematic ModernityОт EverandArtificial Generation: Photogenic French Literature and the Prehistory of Cinematic ModernityОценок пока нет

- The Transcedental Machine PDFДокумент8 страницThe Transcedental Machine PDFRimi NandyОценок пока нет

- Quentin Bajac-The Age of Distraction Photography and FilmДокумент12 страницQuentin Bajac-The Age of Distraction Photography and FilmAgustina Arán100% (1)

- Peter Galassi Before PhotographyДокумент11 страницPeter Galassi Before PhotographyElaine Trindade100% (1)

- A Neglected Tradition? Art History As Bildwissenschaft-Horst BredekampДокумент12 страницA Neglected Tradition? Art History As Bildwissenschaft-Horst BredekampagavilesОценок пока нет

- Jeanfrancois Chevrier The Adventures of The Picture Form in The History of Photography 1Документ22 страницыJeanfrancois Chevrier The Adventures of The Picture Form in The History of Photography 1Carlos Henrique SiqueiraОценок пока нет

- Philip POCOCK Endgame INDA Press Release en PP EditДокумент3 страницыPhilip POCOCK Endgame INDA Press Release en PP EditpjpОценок пока нет

- Bernd + Hilla BecherДокумент30 страницBernd + Hilla BecherJames ConnollyОценок пока нет

- Walter Benjamin On PhotographyДокумент20 страницWalter Benjamin On PhotographyanОценок пока нет

- Intersection of Photography and Architecture IntroductionДокумент7 страницIntersection of Photography and Architecture IntroductionpabloandradehОценок пока нет

- Horst Bredekamp Art History As Bildwissenschaft 2003Документ12 страницHorst Bredekamp Art History As Bildwissenschaft 2003Jose Lozano GotorОценок пока нет

- 07 Walter Benjamin From The Work of Art in The Age of MechanicaДокумент6 страниц07 Walter Benjamin From The Work of Art in The Age of Mechanicakate-archОценок пока нет

- MontageandspectatorДокумент15 страницMontageandspectatorDebanjan BandyopadhyayОценок пока нет

- Technology and Desire: The Transgressive Art of Moving ImagesОт EverandTechnology and Desire: The Transgressive Art of Moving ImagesRania GaafarОценок пока нет

- Sartoris 2005Документ19 страницSartoris 2005cabinetmakerОценок пока нет

- From Carnival To Satire: Photomontage As A Commentary On PhotographyДокумент13 страницFrom Carnival To Satire: Photomontage As A Commentary On PhotographyმირიამმაიმარისიОценок пока нет

- History of PhotographyДокумент4 страницыHistory of PhotographyEricka Mae MateoОценок пока нет

- Photographic PowersДокумент335 страницPhotographic PowerspilgrimhawkОценок пока нет

- N.rosenblum Parcial.p.1a178Документ178 страницN.rosenblum Parcial.p.1a178gabriela100% (1)

- Exhibition As Archive Beaumont Newhall Photography 1839 1937 and The Museum of Modern ArtДокумент9 страницExhibition As Archive Beaumont Newhall Photography 1839 1937 and The Museum of Modern ArtDiego Fernando GuerraОценок пока нет

- Photo at MoMA ElcottДокумент2 страницыPhoto at MoMA ElcottMarcela RuggeriОценок пока нет

- German Abstract Film in The 1920sДокумент5 страницGerman Abstract Film in The 1920sChristoph CoxОценок пока нет

- Lyotard - Presenting The Unpresentable - The SublimeДокумент6 страницLyotard - Presenting The Unpresentable - The Sublimepro_use50% (2)

- Solomon God Eau Who Is Speaking ThusДокумент16 страницSolomon God Eau Who Is Speaking Thusbunnygamer100% (2)

- The Mapping of Space - Perspective, Radar, and 3-D Computer Graphics Lev Manovich PDFДокумент14 страницThe Mapping of Space - Perspective, Radar, and 3-D Computer Graphics Lev Manovich PDFDudley DeuxWriteОценок пока нет

- A Critical Analysis of The Walter Benjam PDFДокумент9 страницA Critical Analysis of The Walter Benjam PDFMudit GoelОценок пока нет

- Krauss ReinventingMedium 1999Документ18 страницKrauss ReinventingMedium 1999annysmiОценок пока нет

- Ci Costello Iversen IntroДокумент15 страницCi Costello Iversen IntroAnonymous HiRiEIsKqОценок пока нет

- The Photographic Reproduction of Space: Wölfflin, Panofsky, KracauerДокумент5 страницThe Photographic Reproduction of Space: Wölfflin, Panofsky, KracaueralexОценок пока нет

- Krauss, Reinventing The Medium (Critical Inquiry 1999)Документ17 страницKrauss, Reinventing The Medium (Critical Inquiry 1999)bartalore4269Оценок пока нет

- People Exposed People As Extras Didi HubermanДокумент8 страницPeople Exposed People As Extras Didi Hubermanerezpery100% (1)

- Film 1900: Technology, Perception, CultureОт EverandFilm 1900: Technology, Perception, CultureAnnemone LigensaОценок пока нет

- Art and Photography (Art Ebook)Документ404 страницыArt and Photography (Art Ebook)Claudiu Galatan100% (2)

- Bernd and Hilla BecherДокумент18 страницBernd and Hilla BechertabumОценок пока нет

- Quentin Bajac - Age of DistractionДокумент12 страницQuentin Bajac - Age of DistractionAlexandra G AlexОценок пока нет

- Intersection of Photography and Architecture IntroductionДокумент7 страницIntersection of Photography and Architecture IntroductionPArul GauTam100% (1)

- The Involution of Photography: September 2009Документ11 страницThe Involution of Photography: September 2009walkerevans439Оценок пока нет

- Damisch FiveNotesДокумент4 страницыDamisch FiveNotesXochitl García100% (1)

- PHRC Symposium Programme April 2014Документ10 страницPHRC Symposium Programme April 2014cesar yanezОценок пока нет

- Expanding Photography - Flusser and Poli PDFДокумент19 страницExpanding Photography - Flusser and Poli PDFJulie WalterОценок пока нет

- Photography Made or Taken Fairburn Jan 505391 Pwdpass4Документ9 страницPhotography Made or Taken Fairburn Jan 505391 Pwdpass4api-255241451Оценок пока нет

- Viridis (Actinopterygii: Perciforms: Centropomidae) in The North CoastДокумент7 страницViridis (Actinopterygii: Perciforms: Centropomidae) in The North CoastbashevisОценок пока нет

- Mitchell, WJT - Holy Landscape (Israel, Palestine, and The American Wilderness) (2000)Документ32 страницыMitchell, WJT - Holy Landscape (Israel, Palestine, and The American Wilderness) (2000)bashevisОценок пока нет

- Perspectives in Ethology Volume - VVAA PDFДокумент348 страницPerspectives in Ethology Volume - VVAA PDFbashevisОценок пока нет

- The Copies of The Qu B MīnārДокумент14 страницThe Copies of The Qu B MīnārbashevisОценок пока нет

- Kiaer, Christina - Boris Arvatov's Socialist Objects (1997)Документ15 страницKiaer, Christina - Boris Arvatov's Socialist Objects (1997)bashevisОценок пока нет

- Batchen, Geoffrey - Phantasm. Digital Imaging and The Death of PhotographyДокумент6 страницBatchen, Geoffrey - Phantasm. Digital Imaging and The Death of PhotographybashevisОценок пока нет

- The Lancet Volume 358 Issue 9281 2001 (Doi 10.1016/s0140-6736 (01) 05693-8) Ruth Richardson - Larmessin's ApoticaireДокумент1 страницаThe Lancet Volume 358 Issue 9281 2001 (Doi 10.1016/s0140-6736 (01) 05693-8) Ruth Richardson - Larmessin's ApoticairebashevisОценок пока нет

- Mobile Sepulchre and Interactive Formats of Memorialization - On Funeral and Mourning Practices in Digital ArtДокумент19 страницMobile Sepulchre and Interactive Formats of Memorialization - On Funeral and Mourning Practices in Digital ArtbashevisОценок пока нет

- Buscombe, Edward - Injuns! Native Americans in The Movies (2006)Документ274 страницыBuscombe, Edward - Injuns! Native Americans in The Movies (2006)bashevisОценок пока нет

- Jones, Colin - The King's Two TeethДокумент17 страницJones, Colin - The King's Two TeethbashevisОценок пока нет

- Martin, Diana - Chinese Ghost MarriageДокумент19 страницMartin, Diana - Chinese Ghost MarriagebashevisОценок пока нет

- Jeandrée, Philipp - A Perfect Model of The Great KingДокумент24 страницыJeandrée, Philipp - A Perfect Model of The Great KingbashevisОценок пока нет

- Candlin, Fiona - The Dubious Inheritance of Touch (Art History and Museum Access)Документ19 страницCandlin, Fiona - The Dubious Inheritance of Touch (Art History and Museum Access)bashevisОценок пока нет

- Partha Mitter - The Triumph of ModernismДокумент273 страницыPartha Mitter - The Triumph of ModernismKiša Ereš100% (12)

- Jan Mrazek, Morgan Pitelka - Whats The Use of Art Asian Visual and Material Culture in Context 2007Документ325 страницJan Mrazek, Morgan Pitelka - Whats The Use of Art Asian Visual and Material Culture in Context 2007bashevisОценок пока нет

- Wood C. DromenonДокумент11 страницWood C. DromenonVera ZakharovaОценок пока нет

- Walker Bynum, Caroline - Holy Anorexia in Modern PortugalДокумент10 страницWalker Bynum, Caroline - Holy Anorexia in Modern Portugalbashevis100% (1)

- Walker Bynum, Caroline - Holy Feast and Holy Fast (The Religious Significance of Food To Medieval Women) (1988)Документ457 страницWalker Bynum, Caroline - Holy Feast and Holy Fast (The Religious Significance of Food To Medieval Women) (1988)bashevis60% (5)

- Political Polarization and Media: Threats To The Democratic Process in GeorgiaДокумент10 страницPolitical Polarization and Media: Threats To The Democratic Process in GeorgiaGIP100% (1)

- Public Relations Conceptual MapДокумент1 страницаPublic Relations Conceptual MapOrlando HernándezОценок пока нет

- Normative Theory of The PressДокумент5 страницNormative Theory of The PressMarcelo Alves Dos Santos Junior100% (1)

- Politeness On Instagram Comment SectionДокумент12 страницPoliteness On Instagram Comment SectionAinun MardhiahОценок пока нет

- Media ManagementДокумент93 страницыMedia ManagementSudip Dutta100% (1)

- Minerva Networks Transforms Virtual Concert Experience With Watch Together PlatformДокумент3 страницыMinerva Networks Transforms Virtual Concert Experience With Watch Together PlatformPR.comОценок пока нет

- MARKETING STRATEGIES OF Radio MirchiДокумент9 страницMARKETING STRATEGIES OF Radio MirchiHEERA SINGH100% (1)

- National Publishing CompanyДокумент11 страницNational Publishing Companysiddhu1579212Оценок пока нет

- DDT Contract - Dana GrahamДокумент1 страницаDDT Contract - Dana GrahamdanagrahОценок пока нет

- Tosh CargoДокумент12 страницTosh Cargoseifsaidi2020Оценок пока нет

- Media and Information Literacy: Quarter 2 - Module 2 Week 2Документ15 страницMedia and Information Literacy: Quarter 2 - Module 2 Week 2Louie Ramos100% (1)

- Media and Information Literacy Module 6Документ4 страницыMedia and Information Literacy Module 6Ennyliejor YusayОценок пока нет

- Berklee Scale Requirements - 3rd SemesterДокумент2 страницыBerklee Scale Requirements - 3rd SemesterGeorge ConstantinouОценок пока нет

- Study - Id92839 - Online Flight Booking Skyscanner in The United Kingdom Brand ReportДокумент30 страницStudy - Id92839 - Online Flight Booking Skyscanner in The United Kingdom Brand Reportmonil panchalОценок пока нет

- Village Free Press Media KitДокумент6 страницVillage Free Press Media KitMichaelRomainОценок пока нет

- The Scarlet Letter A Romance PDFДокумент319 страницThe Scarlet Letter A Romance PDFPeter KizilosОценок пока нет

- Consumer Perceptions of Retail Store Image and Its Impact On Store Loyalty - An Empirical StudyДокумент1 страницаConsumer Perceptions of Retail Store Image and Its Impact On Store Loyalty - An Empirical StudyShubhangi KesharwaniОценок пока нет

- Aleksandra Prijovic - Google SearchДокумент1 страницаAleksandra Prijovic - Google SearchDjordjeОценок пока нет

- Internship ProjectДокумент13 страницInternship ProjectVivek Kumar100% (1)

- Global Digital Cultures - Perspectives From South AsiaДокумент327 страницGlobal Digital Cultures - Perspectives From South AsiaAkansha BoseОценок пока нет

- An Introduction To Integrated Marketing CommunicationsДокумент18 страницAn Introduction To Integrated Marketing CommunicationsSaurabh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Template Set - Marketing Campaign ManagementДокумент60 страницTemplate Set - Marketing Campaign ManagementAbhijitОценок пока нет

- كتاب التحليل المالي الكشف عن الانحراف والاختلاس PDFДокумент183 страницыكتاب التحليل المالي الكشف عن الانحراف والاختلاس PDFnasrcia100% (2)

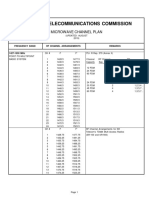

- MICROWAVE CHANNEL PLAN Rev 2019Документ55 страницMICROWAVE CHANNEL PLAN Rev 2019J'ven MakilanОценок пока нет

- Unit 5 Intermediate (TV Programs) PDFДокумент15 страницUnit 5 Intermediate (TV Programs) PDFAytrt srОценок пока нет

- Marketing Mba Exam PaperДокумент1 страницаMarketing Mba Exam PaperPrateek ShrivastavaОценок пока нет

- A Bill: 116 Congress 1 SДокумент21 страницаA Bill: 116 Congress 1 SMarkWarnerОценок пока нет

- ResearchДокумент21 страницаResearchHezielОценок пока нет

- (Ebook) Firm Voice CompendiumДокумент272 страницы(Ebook) Firm Voice CompendiumgagansrikankaОценок пока нет