Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Research Article

Загружено:

Tony RamirezОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Research Article

Загружено:

Tony RamirezАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Research Article

A Quantitative Documentation of the Composition of Two

Powdered Herbal Formulations (Antimalarial and Haematinic)

Using Ethnomedicinal Information from Ogbomoso, Nigeria

Adepoju Tunde Joseph Ogunkunle, Tosin Mathew Oyelakin,

Abosede Oluwaseyi Enitan, and Funmilayo Elizabeth Oyewole

Environmental Biology Unit, Department of Pure and Applied Biology, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology,

PMB 4000, Ogbomoso, Oyo State, Nigeria

Correspondence should be addressed to Adepoju Tunde Joseph Ogunkunle; tjogunkunle@lautech.edu.ng

Received 12 September 2013; Revised 8 January 2014; Accepted 8 January 2014; Published 20 February 2014

Academic Editor: Rainer W. Bussmann

Copyright 2014 Adepoju Tunde Joseph Ogunkunle et al. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons

Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is

properly cited.

Te safety of many African traditional herbal remedies is doubtful due to lack of standardization. Tis study therefore attempted to

standardize two polyherbal formulations from Ogbomoso, Oyo State, Nigeria, with respect to the relative proportions (weight-

for-weight) of their botanical constituents. Information supplied by 41 local herbal practitioners was statistically screened for

consistency and then used to quantify the composition of antimalarial (Malof-HB) and haematinic (Haematol-B) powdered herbal

formulations with nine and ten herbs, respectively. Malof-HB contained the stem bark of Enantia chlorantha Oliv. (30.0), Alstonia

boonei De Wild (20.0), Mangifera indica L. (10.0), Okoubaka aubrevillei Phelleg &Nomand (8.0), Pterocarpus osun Craib (4.0), root

bark of Calliandra haematocephala Hassk (10.0), Sarcocephalus latifolius (J. E. Smith) E. A. Bruce (8.0), Parquetina nigrescens (Afz.)

Bullock (6.0), and the vines of Cassytha fliformis L. (4.0), while Haematol-B was composed of the leaf sheath of Sorghum bicolor

Moench (30.0), fruit calyx of Hibiscus sabdarifa L. (20.0), stem bark of Teobroma cacao L. (10.0), Khaya senegalensis (Desr.) A.

Juss (5.5), Mangifera indica (5.5), root of Aristolochia ringens Vahl. (7.0), root bark of Sarcocephalus latifolius (5.5), Uvaria chamae

P. Beauv. (5.5), Zanthoxylum zanthoxyloides (Lam.) Zepern & Timler (5.5), and seed of Garcinia kola Heckel (5.5). In pursuance of

their general acceptability, the two herbal formulations are recommended for their pharmaceutical, phytochemical, and microbial

qualities.

1. Introduction

Te Medical and Dental Practitioners (Amendment) Decree

number 78 promulgated by the federal government of Nigeria

on September 30, 1992, placed traditional and alternative

medicine side by side with the orthodox medicine [1]. Ever

since that time, there had been an overwhelming increase in

the public awareness and usage of herbal medicines in the

treatment and/or prevention of diseases. Tis development

has been attributed to the active mass media advertisement

embarked upon by the manufacturers and marketers of

herbal drugs who have taken advantage of the relatively high

cost of the conventional medicines [2].

In an attempt to enhance the acceptability of herbal

medicines by consumers in Nigeria, some manufacturers,

licensed by the National Agency for Food Drug Administra-

tion and Control (NAFDAC), and, also, many unregistered

local practitioners have come up with products usable in

the conventional dosage forms such as tablets, capsules, sus-

pensions, solutions, and powders [2]. Many of these herbal

products usually contain two or more botanicals each of

which has a number of chemical compounds that may give

the anticipated activity in combination.

In the development of polyherbal formulations, pharma-

cognosists undertake to analyze and evaluate those active

ingredients from diferent medicinal plants for their possible

chemical interactions with various excipients [3, 4]. Informa-

tion on which such studies are based usually originates from

the traditional healers who make use of the herbs without

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Volume 2014, Article ID 751291, 8 pages

http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/751291

2 Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine

any form of standardization. Annexure I of the guidelines

published by the World Health Organization on evaluation of

traditional medicine provides, among others, for quantitative

list of active ingredients to accompany each herbal product

for the information of the consumer. In cases where the

active ingredients have not been identifed, the whole herb

serving as a constituent of a multiherbal formulation is

regarded as one active ingredient [5]. At the best, traditional

herbal remedies display their constituent plant species and

sometimes, also, the plant parts with little or no empirical

information on their relative proportions [6, 7]. Such details,

especially to the traditional African herbalists, constitute a

trade secret that must be jealously guarded. Tis practice has

efectively hindered the development of phytomedicine in

this part of the world.

Although traditional herbal medicine has always been

part of the peoples culture in Africa, this form of medicine

is yet to be relatively well organized as, for example, in India

andChina [8]. Africanherbal products have particularly been

called to question on account of adulteration, substitution,

contamination, misidentifcation, lack of standardization,

incorrect preparation and/or dosage, inappropriate labeling,

and/or advertisement [9, 10]. Also in the view of Idika

and Niemogha [11], there is an urgent need for developing

some systems and methods of standardization for traditional

medicines in order to enhance the general acceptability, to

allay the skepticism and fears of the people, to avoid dangers

of toxicity, side efects, and overdosage, and to ensure that

a certain minimum level of hygiene in their preparation is

maintained.

Malaria fever has been listed as a major public health

problem in Nigeria where it accounts for more cases and

deaths than any other country in the world [12, 13]. It is

responsible for over 70% of outpatient hospital visitation

and has a great toll on productivity, being a major cause

of absenteeism from school and work and of disease and

complications in children and pregnant women [14]. Tere

is also evidence that people in Nigeria now attend hospitals

as ofen as they go to herbalists to treat themselves of this

dreaded disease, which is most prevalent in southwestern,

north central, and northwestern parts of the country [12, 15,

16].

Much as in the orthodox medical practice, herbalism in

many parts of the world, including southwestern Nigeria,

considers the care of the blood as paramount to preventive

and curative health care [7, 17, 18]. Against this background,

the present study sought to address the issue of standard-

ization of antimalarial and haematinic powdered herbal

remedies popularly used in Ogbomoso, Nigeria, by way of

documenting their prevalent botanical composition, parts

used, and relative proportions of these active ingredients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preliminary Survey and Data Manipulation. A prelim-

inary survey among 55 local herbal practitioners (HPs) in

Ogbomoso land, Nigeria, in May 2011 revealed that 41 of

them were noble in the production and sale of both types of

herbal remedies of interest. Te questionnaire-guided survey

made the respondents identify the botanicals by name and

parts used for the antimalarial herbal remedy (AMHR) and

haematinic herbal remedy (HAHR).

Before the choice of a statistical tool for analyzing the

data collected, it was found expedient to accept that the

statistical mode of each of the two distributions among the 41

HPs should be taken as the most typical herbal formulation

in the study area. To that extent, qualitative data on the

botanical composition of both remedies were independently

transformed into frequency distribution tables, each with

class interval size of 2. With the observation of the maximum

frequency occurring at the end of the two distributions, the

method of grouping three classes at a time was adopted [19]

and the mode in each case was calculated using the formula

according to Gupta [19] as follows:

Mode = +

1

0

1

0

1

2

, (1)

where is lower limit of the modal class,

1

is frequency of the

modal class,

0

is frequency of the class preceding the modal

class,

2

is frequency of the class succeeding the modal class,

and || is the absolute (positive) value of .

Te exercise described above, which, respectively, yielded

9 and 10 herbs as modes for AMHR and HAHR successfully

reduced the number of HPs to be included to 32, all of which

listed both Enantia chlorantha Oliv. and Alstonia boonei De

Wild as part of AMHR and Sorghum bicolor Moench. as

part of HAHR. For consistency in the list of the plants in

each remedy, three further respondents were excluded, such

that the number of HPs to be included in the next phase of

the study was 29. Considering the fact that data for the two

herbal remedies under study were independent andthat some

healers ofered one while others ofered both remedies, it was

possible to identify 33 herbal product outlets (HPOs) from

among the 29 HPs, comprised of 19 for AMHRs and 14 for

HAHRs.

2.2. Determinationof Percent Compositionof Herbal Fractions.

Between December 2011 and April 2012, visits were made

to the 33 identifed HPOs to seek information concerning

the source of plant materials used, relative quantity of each

fraction, and procedure for preparing the powdered AMHRs

and HAHRs. An open plastic container of approximately

5-litre volume (20 cm top diameter, 17 cm bottom diameter,

and 18 cmdepth) was used as a standard measure, which each

respondent was asked to reference for the fnal powdered

product. Te respondents were made to select the quantity

of each dried herbal component as if they were to carry out

the exercise on a good day. Te selections were procured into

labeled plastic bags with the assumption that the correspond-

ing herbs collected from diferent outlets had been dried to

fairly equal moisture contents.

Te weights (g) of the nine components of AMHR pro-

cured from19 outlets and the ten components of HAHRfrom

14 outlets were each determined using a Measuretech triple-

beambalance MB-2610 model. In recognition of the necessity

for data consistency in this type of study, the weight values

Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 3

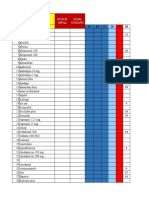

Table 1: Local herbal product outlets visited for AMHRs and

HAHRs in Ogbomoso, Nigeria.

Local government area

Number of outlets

AMHRs HAHRs Total

1 Ogbomoso North 3 4 7

2 Ogbomoso South 3 1 4

3 Surulere 2 1 3

4 Oriire 2 3 5

5 Ogo-Oluwa 4 2 6

Total 14 11 25

AMHRs: antimalarial herbal remedies; HAHRs: haematinic herbal remedies.

for each remedy were fed as multivariate data matrix into the

computer-based SPSS version 17.0, which was used to identify

and exclude outliers across the treatments (i.e., the outlets) in

each case. Tis step reduced the number of outlets for fnal

consideration to 25, that is, 14 and 11 for AMHR and HAHR,

respectively (Table 1).

Using the same statistical sofware, two other analyses

were carriedout onthe quantitative data for the two remedies.

Tese were Pearsons correlation test on the treatments and

the means of the variables (i.e., herbal fractions). Te total

of the mean values of the herbal components in a remedy was

equated to 100%and the contribution of each component was

computed with reference to 100.

3. Results and Discussion

Te results of this study are shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3 and

Tables 2 to 5. A wide variation in the botanical constituents

and their relative quantities in the two herbal remedies was

encountered during the survey. Between 1 and 14 diferent

plant species were identifed as constituents of AMHRs while

those of HAHRs ranged between 1 and 12. Similar obser-

vations were made by Odugbemi et al. [20] with regard to

malaria therapy in Okeigbo, Ondo State, southwest of Nige-

ria. Te multistage preparation of the powdered remedies

also followed diverse protocols, but with two main possible

alternatives, namely, A and B. Te majority (i.e., 84%) of

the HPs usually adopted alternative A while alternative B

was common with 16%, who incidentally were small scale

manufacturers (Figure 3). Te frst alternative was probably

more preferable because of the merit that the herbal fractions

could more accurately be measured out in the desired

proportions. Moreover, according to the respondents, milling

of the fractions separately was advantageous because an herb

so milled was usable in the formulation of more than one type

of herbal remedies. Te practice also ensured homogeneity

of surface area in the fnal powdered product since two

diferent herbal materials might not respond equally to

the milling process. Tese observations are in consonance

with the bottlenecks to polyherbal formulations identifed

by Mallavadhani [21], namely, large variations in diferent

samples of the same formulation, variations in ingredients,

variation in quantity of the ingredients, and lack of uniform

manufacturing protocols.

Figure 1: Samples of the herbs used in combination as antimalarial

herbal formulation (Malof-HB) in Ogbomoso, Nigeria. ENCH:

Enantia chlorantha; ALBO: Alstonia boonei; CAHA: Calliandra

haematocephala; MAIN: Mangifera indica; OKAU: Okoubaka aubre-

villei; SALA: Sarcocephalus latifolius; PANI: Parquetina nigrescens;

CAFI: Cassytha fliformis; PTOS: Pterocarpus osun; STB: stem bark;

ROT: root; VIN: vines.

Figure 2: Samples of the herbs used in combination as haematinic

herbal formulation (Haematol-B) in Ogbomoso, Nigeria. SOBI:

Sorghum bicolor; HISA: Hibiscus sabdarifa; THCA: Teobroma

cacao; ARRI: Aristolochia ringens; GAKO: Garcinia kola; KHSE:

Khaya senegalensis; MAIN: Mangifera indica; SALA: Sarcocephalus

latifolius; UVCH: Uvaria chamae; ZAZA: Zanthoxylum zanthoxy-

loides; LES: leaf sheath; FRC: fruit calyx; STB: stem bark; ROT: root;

SED: seed; RTB: root bark.

Te composition of antimalarial and haematinic herbal

remedies from Ogbomoso in parts per hundred is shown

in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. Not only have the botanicals

making up these remedies been documented fromthis study,

but also their relative quantities have beenobjectively defned.

On this account, the two remedies were, respectively, named

Malof-HB and Haematol-B herbal formulations for the

purpose of proper identifcation. On the question whether

these formulations are representative of the practice in

4 Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Table 2: Similarity matrix based on correlation coefcients of data collected from antimalarial herbal remedy outlets in Ogbomoso, Nigeria.

OT1 OT2 OT3 OT4 OT5 OT6 OT7 OT8 OT9 OT10 OT11 OT12 OT13 OT14

OT1 1

OT2 0.844

1

OT3 0.737

0.978

1

OT4 0.806

0.991

0.978

1

OT5 0.733

0.978

1.00

0.977

1

OT6 0.815

0.984

0.968

0.991

0.968

1

OT7 0.796

0.993

0.991

0.992

0.991

0.986

1

OT8 0.676

0.949

0.959

0.977

0.959

0.958

0.962

1

OT9 0.764

0.979

0.995

0.970

0.944

0.958

0.988

0.937

1

OT10 0.727

0.979

0.992

0.987

0.993

0.976

0.989

0.979

0.981

1

OT11 0.481

ns

0.835

0.886

0.876

0.884

0.821

0.958

0.936

0.866

0.906

1

OT12 0.671

0.948

0.969

0.875

0.970

0.970

0.965

0.987

0.944

0.987

0.911

1

OT13 0.789

0.992

0.991

0.986

0.992

0.980

0.996

0.958

0.989

0.985

0.853

0.958

1

OT14 0.923

0.949

0.890

0.935

0.886

0.916

0.992

0.872

0.899

0.883

0.743

0.842

0.926

Correlation is signifcant at the 0.01 level (2-tail);

signifcant at the 0.05 level (2-tail); ns: not signifcant; OT1, OT2, OT3,. . ., OT14: antimalarial herbal

remedy outlets 1 to 14 used for the study.

Table 3: Similarity matrix based on correlation coefcients of data collected from haematinic herbal remedy outlets in Ogbomoso, Nigeria.

OT1 OT2 OT3 OT4 OT5 OT6 OT7 OT8 OT9 OT10 OT11

OT1 1

OT2 0.981

1

OT3 0.971

0.985

1

OT4 0.987

0.964

0.964

1

OT5 0.966

0.979

0.999

0.959

1

OT6 0.978

0.988

0.997

0.975

0.996

1

OT7 0.975

0.951

0.957

0.991

0.951

0.972

1

OT8 0.961

0.958

0.935

0.952

0.931

0.935

0.911

1

OT9 0.953

0.949

0.984

0.954

0.986

0.981

0.954

0.916

1

OT10 0.985

0.977

0.982

0.979

0.977

0.988

0.981

0.917

0.963

1

OT11 0.951

0.980

0.991

0.941

0.988

0.989

0.946

0.895

0.965

0.977

Correlation is signifcant at the 0.01 level (2-tail); OT1, OT2, OT3,. . ., OT11: haematinic herbal remedy outlets 1 to 11 used for the study.

the study area, the answer is in the afrmative for two

reasons. In the frst place, the results were a product of wide

consultations among referred individuals in the act of local

herbal formulation and secondly, the formulations obtained

from them have been statistically screened to an acceptable

level of consistency (Tables 2 and 3).

As expected, the results of this study have shown the

qualitative and quantitative variations in the two herbal

formulations considered to be diverse. However, the most

typical lists of herbs for AMHRs and HAHRs in this part of

Nigeria have been statistically identifed and quantitatively

characterized (Tables 4 and 5). Tese eforts were not meant

either to prejudice the practice in the study location or to

force the manufacturers to conform to the most popular list

of plants for each remedy. In fact one would recommend

that all the variants of the two herbal formulations should be

given adequate attention if the holistic view of the situation

on ground is intended. But then, for any form of herbal drug

standardization to be valid and workable, it should be based

on the representative practice in the localities that ofer the

remedy.

Of the 49 herbal product outlets identifed across the 41

healers initially interviewed, 28 and 21 ofered AMHRs and

HAHRs, respectively. Similarly, 19 and 14 were, respectively,

identifed across the 29 healers subsequently considered for

analysis. Tis implies that the newly standardized Malof-HB

included the listed nine species of plants (Table 4) that were

used by 68% of the outlets while the standardized Haematol-

B included the 10 identifed species that were favoured

by 67% of the outlets. A total of nine (32%) antimalarial

and seven (33%) haematinic herbal products outlets were

at variance with the standardized formulations in terms

of the composition of their recipe. While Malof-HB and

Haematol-B can be said to be representative of the practice

in Ogbomoso in terms of the quality and quantity of their

composition, the proportion of the dissenting practice would

not allow the information therefrom to be ignored in future

investigations.

Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 5

Table 4: Botanical characterization and % composition (wt/wt) of antimalarial herbal formulation (Malof-HB) from Ogbomoso, Nigeria.

Plant species Family

Indigenous

name (Yoruba)

Part used Total weight (g) Mean weight (g) Parts per 100

1 Enantia chlorantha Oliv. Annonaceae

Awopa/Dokita

igbo

Stem bark 19248.6

1374.9

(1039.52005.5)

30

2 Alstonia boonei De Wild Apocynaceae Ahun Stem bark 12832.3

919.5

(527.51232.0)

20

3

Calliandra haematocephala

Hassk

Fabaceae Tude Root 6430.6

459.8

(310.0740.0)

10

4 Mangifera indica L. Anacardiaceae Mongoro Stem bark 3077.2

460.5

(137.8380.0)

10

5

Okoubaka aubrevillei

Phelleg & Nomand

Santalaceae Igi nla Stem bark 5092.9

366.3

(134.3523.3)

8

6

Sarcocephalus latifolius

(J. E. Smith) E. A. Bruce

Rubiaceae Egbesi Root bark 5140.2

367.2

(232.0554.7)

8

7

Parquetina nigrescens (Afz.)

Bullock

Periplocaceae Ogbo Root bark 3820.5

273.9

(195.0357.5)

6

8 Cassytha fliformis L. Lauraceae Omonigelegele Vine 2039.1

181.7

(119.9278.0)

4

9 Pterocarpus osun Craib Papilionaceae Igi osun Stem bark 2686.0

185.7

(127.8286.8)

4

Total 4589.5 100

wt/wt: weight-for-weight; (number of outlets) = 14; values in parentheses are the ranges of the measurements.

Table 5: Botanical characterization and % composition (wt/wt) of haematinic herbal formulation (Haematol-B) from Ogbomoso, Nigeria.

Plant species Family

Indigenous

name (Yoruba)

Part used Total weight (g) Mean weight (g) Parts per 100

1 Sorghum bicolor Moench Poaceae Oka baba Leaf sheath 13371.1

1215.4

(917.01632.0)

30

2

Hibiscus sabdarifa L.

(red variety)

Malvaceae Isapa pupa Fruit calyx 9104.0

827.6

(460.0972.0)

20

3 Teobroma cacao L. Sterculiaceae Koko Stem bark 4565.2

415.0

(241.5494.5)

10

4 Aristolochia ringens Vahl. Aristolochiaceae Akogun Roots 3174.2

288.6

(140.4453.0)

7.0

5 Garcinia kola Heckel Guttiferae Orogbo Seed 2473.4

225.0

(104.0309.5)

5.5

6

Khaya senegalensis (Desr.)

A. Juss.

Meliaceae Agano Stem bark 2505.0

227.7

(211.0283.0)

5.5

7 Mangifera indica L. Anacardiaceae Mongoro Stem bark 2519.2

229.0

(176.0282.0)

5.5

8

Sarcocephalus latifolius

(J. E. Smith) E. A. Bruce

Rubiaceae Egbesi Root bark 2508.9

228.3

(97.0325.0)

5.5

9 Uvaria chamae P. Beauv. Annonaceae Eruju Root bark 2491.9

227.5

(173.0340.3)

5.5

10

Zanthoxylum

zanthoxyloides (Lam.)

Zepern & Timler

Rutaceae Ata Root bark 2480.3

225.7

(120.4303.7)

5.5

Total 4109.8 100

wt/wt: weight-for-weight; (number of outlets) = 11; values in parentheses are the ranges of the measurements.

Single herbs are the common form in which herbal

formulations are presented and used. Tis practice appears

to be the easiest way to consume herbs and most economical

method of presenting them to individuals as well as herbal

supplement manufacturers [22]. From all the herbalists

contacted during the study, the names Enantia chlorantha

and Alstonia boonei consistently occurred in the list of herbs

for antimalarial remedies and so did Sorghum bicolor in the

list for haematinic remedies. Tese fndings are consistent

with those of Odugbemi et al. [20] and could be a pointer

6 Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine

A B

Herbs procurement

Chipping

Cleaning

Sorting (separation) of

fractions

Sun drying

Milling

Sieving

Measurement

(quantifcation) of fractions

Compose (blending)

Sieving

Milling

Compose (mixing chips)

Measurement

(quantifcation) of fractions

Herbal product

Figure 3: Flow chart of the processes for manufacturing powdered

antimalarial and haematinic herbal remedies by the herbal prac-

titioners in Ogbomoso, Nigeria. Option A was adopted by 84%;

Option B was adopted by 16% of the 25 respondents.

to the general opinion that a single or at most two herbs

could be potent enough to cure one or more ailments

[2325].

With great experience and knowledge of herbs spanning

many centuries, indigenous people are believed to have learnt

that some herbs required the inclusion of other ingredients

(and also other herbs) as catalyst or else the brewof the herbs

being used for therapeutic purposes was inefective [26]. Tis

discovery probably marked the origin of polyherbal or multi-

herbal formulations, which are obtained by subjecting herbal

ingredients from a number of specifed medicinal plant

parts to various processes such as extraction, distillation,

expression, fractionation, purifcation, concentration, and

fermentation [21]. It is however important to note that, as we

frequently see, many herbs go into a medicinal preparation,

so we do have certain medicinal plants, each having multiple

therapeutic uses [23, 27].

Mallavadhani [21] identifed two key parameters of herbal

drugs, namely, standardization and quality evaluation. While

quality evaluation pertains to requirements for authenticity,

Pharmacognostical

Physicochemical Phytochemical

Heavy metals, pesticides, toxins, radioactives,

fumigants, pathogens, and fungicides

Residual analyses

Herbal

drugs

Taxonomical

Morphological

Biological

Biochemical

Biotechnical

Biotechnological

Ash values

pH

Optical rotation

Specifc gravity

Hardness

Disintegration time

Elemental composition

Extractive values

Chemical profling

TLC fngerprinting

Markers

- Bioactive

- Chemical

HPTLC/HPLC-based

quantifcations

Figure 4: Te triple P-based protocols along with residual analyses

for standardizationandquality control of herbal drugs (source: [21]).

purity, and safety, standardization deals, among other things,

with assay, that is, analyzing herbal drug preparation and

adjusting them to a defned content of a constituent. To

that extent, herbal product standardization has been defned

as the body of information and controls necessary to pro-

duce materials of reasonable consistency [28]. Rukangira [6]

believes that the quality of traditional medicines is highly

dependent on individual practitioner, who in his wisdom

determines the correctness of identity and quantity of plant

parts, and, as a result, there is no guarantee of the authenticity

and quantity of plant material used in the preparation. To

this extent, there is a need to select proper and appropriate

technologies for the industrial production of medicines such

that the efectiveness of the preparation can be ensured. One

of the ways to achieve this goal is to minimize the inherent

variation in natural product composition through quality

assurance practice applied to manufacturing processes and

techniques.

Eforts of the World Health Organization and a number

of countries dealing with herbal drugs have yielded the triple

P-based protocols for standardization and quality control of

herbal drugs, that is, pharmacognostical, physicochemical,

and phytochemical, along with residual analyses (Figure 4).

Since standardization of herbal medicines arose out of the

need to create a uniform product for clinical trials [29], this

present study can be said to have contributed a piece to the

standardization of herbal medicine in Nigeria. It has qualita-

tively and quantitatively defned the botanical constituents of

antimalarial and haematinic powdered herbal formulations

commonly used in Ogbomoso, southwest of Nigeria.

Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 7

4. Conclusion and Recommendation

Antimalarial (Malof-HB) and haematinic (Haematol-B)

powdered herbal formulations from Ogbomoso, Nigeria,

have beenbotanically characterizedandquantifed. Anaspect

of the pharmacognostical approach to their standardization

has thus been addressed. It would therefore be of great

interest if researchers could work further to evaluate the

pharmaceutical, phytochemical, and microbial qualities of

Malof-HB and Haematol-B with a view to considering them

for general acceptability.

Conflict of Interests

Te authors have read and understood the editorial policy

statement of the journal on declaration of confict of interests

and as such declare (a) that there was no support from any

organization for the submitted manuscript to the journal; (b)

that there are no fnancial relationships with any individuals

or organizations that might have interest in the submitted

work; (c) that there are no other relationships or activities

that could appear to have infuenced the research, other

than the authors interest in contributing their quota to the

standardization of herbal medicine in Nigeria. As a result

of the foregoing, the authors hereby declare that there is no

confict of interests regarding the publication of this paper by

the journal.

Acknowledgments

Te authors are grateful to those medicinal herb sellers

at Oja-jagun, Ogbomoso, who ofered to assist in locating

some traditional herbal product outlets in the study area,

and to those herbal practitioners in Ogbomoso, Arowomole,

Ajaawa, Odo-Oba, Iresaapa, and Iresaadu, who graciously

ofered information and the herbal materials used for the

study.

References

[1] ABFR & CO, Chronology of Nigerian Decrees, ABFR & CO Law

Ofce, Lagos, Nigeria, 1996.

[2] A. Okunlola, A. A. Adewoyin, and O. A. Odeku, Evaluation

of pharmaceutical and microbial qualities of some herbal

medicinal products in South Western Nigeria, Tropical Journal

of Pharmaceutical Research, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 661670, 2007.

[3] S. G. Bhope, D. H. Nagore, V. V. Kuber, P. K. Gupta, and M. J.

Patil, Design and development of a stable polyherbal formula-

tion based on the results of compatibility studies, Pharmacog-

nosy Research, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 122129, 2011.

[4] P. V. Gomase, P. S. Shire, S. Nazim, and A. B. Choudhari, Devel-

opment and evaluation of polyherbal formulation for anti-

infamatory activity, Journal of Natural Product and Plant

Resources, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 8590, 2011.

[5] World Health Organization, General Guidelines for Methodoli-

gies on Research and Evaluation of Traditional Medicine, World

Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

[6] E. Rukangira, Te African herbal industry: constraints and

challenges, in Proceedings of the Natural Products and Cosme-

ceuticals Conference, pp. 123, 2001, http://e.ncut.edu.cn/eclass/

mydocuments/82928/20080515181239.pdf.

[7] M. Alamgir and S. J. Uddin, Recent advances on the eth-

nomedicinal plants as immunomodulatory agents, in Eth-

nomedicine: A Source of Complementary Terapeutics, D. Chat-

topadhyay, Ed., pp. 227244, Research Signpost, Kerala, India,

2010.

[8] B. Patwardhan, D. Warude, P. Pushpangadan, and N. Bhatt,

Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine: a compara-

tive overview, Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative

Medicine, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 465473, 2005.

[9] A. Lau, M. J. Holmes, S. Woo, and H. Koh, Analysis of

adulterants in a traditional herbal medicinal product using liq-

uid chromatography-mass spectrometry-mass spectrometry,

Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, vol. 31, no.

2, pp. 401406, 2003.

[10] World Health Organization, WHO Guidelines on Good Agri-

cultural and Collection Practices (GACP) for Medicinal Plants,

WHO, Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

[11] N. R. Idika and M. T. Niemogha, Te diversity of uses of

medicinal plants in Nigeria, in A Textbook of Medicinal Plants

from Nigeria, T. Odugbemi, Ed., pp. 7179, University of Lagos

Press, Lagos, Nigeria, 2008.

[12] United States Embassy in Nigeria, Nigeria Malaria fact sheet,

U. S. Embassy in Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria, 2011.

[13] World Health Organization, Malaria, Fact Sheets, World Health

Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2013, http://www.who.int/

mediacentre/factsheets/fs094/en/.

[14] W. Oyibo, A. F. Fagbenro-Beyioku, and U. Igbasi, Uses of medi-

cinalplants in the treatment of malaria and gastrointestinal

parasitic infections, in A Textbook of Medicinal Plants from

Nigeria, T. Odugbemi, Ed., pp. 243256, University of Lagos

Press, Lagos, Nigeria, 2008.

[15] A. O. Okunade, Te Underdevelopment of Health Care Systemin

Nigeria, Faculty of Clinical Scieces and Dentistry, University of

Ibadan, Vantage Publishers Limited, Ibadan, Nigeria, 2001.

[16] A. T. J. Ogunkunle and S. B. Ashiru, Experience and percep-

tions of the residents of Ogbomoso land Nigeria on the safety

and efcacy of herbal medicines, Journal of Herbal Practice and

Technology, vol. 1, pp. 2228, 2011.

[17] P. O. Fabeku and O. Akinsulire, Te role of traditional medi-

cine among the Yoruba, South-West Nigeria, in A Textbook of

Medicinal Plants from Nigeria, T. Odugbemi, Ed., pp. 4354,

University of Lagos Press, Lagos, Nigeria, 2008.

[18] I. I. Olatunji-Bello and B. O. Iranloye, Physiological actions of

some medicinal plants, in A Textbook of Medicinal Plants from

Nigeria, T. Odugbemi, Ed., pp. 257272, University of Lagos

Press, Lagos, Nigeria, 2008.

[19] S. C. Gupta, Fundamentals of Statistics, Himalaya Publishing

House, PVT Limited, Mumbai, India, 6th edition, 2011.

[20] T. O. Odugbemi, O. R. Akinsulire, I. E. Aibinu, and P. O. Fabeku,

Medicinal plants useful for malaria therapy in Okeigbo, Ondo

State, Southwest Nigeria, African Journal of Traditional, Com-

plementary and Alternative Medicines, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 191198,

2007.

[21] U. V. Mallavadhani, Standardization and Quality Control of

Multiherbal Formulations, Herbal Drugs andBio-Remedies Cell

Regional Research Laboratory, Bhubaneswar, India, 2011.

[22] Holistic Herbalist, Herbal formulation: why the balance and

synergy of Herbs are the life of any herbal formulation, 2013,

http://www.holistic-herbalist.net/herbal-formulation.html.

[23] E. Kafaru, Immense Help from Natures Workshop, Elikaf Health

Services Limited, Lagos, Nigeria, 1994.

8 Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine

[24] S. Muhammad and N. A. Amusa, Te important food crops

and medicinal plants of North-Western Nigeria, Research

Journal of Agriculture and Biological Sciences, vol. 1, no. 3, pp.

254260, 2005.

[25] D. Kubmarawa, G. A. Ajoku, N. M. Enwerem, and D. A. Okorie,

Preliminary phytochemical and antimicrobial screening of 50

medicinal plants from Nigeria, African Journal of Biotechnol-

ogy, vol. 6, no. 14, pp. 16901696, 2007.

[26] I. Aibinu, E. Adenipekun, and T. O. Adelowotan, Factors that

may be responsible for the inefectiveness of medicinal plants

when used in therapy, in A Textbook of Medicinal Plants from

Nigeria, T. Odugbemi, Ed., pp. 319325, University of Lagos

Press, Lagos, Nigeria, 2008.

[27] S. B. Zailani and A. H. Ahmed, Some medicinal plants used

as traditional recipes for some disorders among northern com-

munities in Nigeria, in A Textbook of Medicinal Plants from

Nigeria, T. Odugbemi, Ed., pp. 5569, University of Lagos Press,

Lagos, Nigeria, 2008.

[28] F. Gaedcke, B. Steinhof, and H. Blasius, Herbal medici-

nal products, in Scientifc and Regulatory Basis for Develop-

ment, Quality Assurance and Marketing Authorisation by Wis-

senschaffiche, Stuttgart, pp. 3752, CRCPress, Boca Raton, Fla,

USA, 2003.

[29] T. Odugbemi and A. Ayoola, Medicinal plants from Nigeria:

sn overview, in A Textbook of Medicinal Plants from Nigeria,

T. Odugbemi, Ed., pp. 917, University of Lagos Press, Lagos,

Nigeria, 2008.

Submit your manuscripts at

http://www.hindawi.com

Stem Cells

International

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

MEDIATORS

INFLAMMATION

of

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Behavioural

Neurology

Endocrinology

International Journal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Disease Markers

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

BioMed

Research International

Oncology

Journal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Oxidative Medicine and

Cellular Longevity

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

PPAR Research

The Scientifc

World Journal

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Immunology Research

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Journal of

Obesity

Journal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Computational and

Mathematical Methods

in Medicine

Ophthalmology

Journal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Diabetes Research

Journal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Research and Treatment

AIDS

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Gastroenterology

Research and Practice

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Parkinsons

Disease

Evidence-Based

Complementary and

Alternative Medicine

Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporation

http://www.hindawi.com

Вам также может понравиться

- Phytochemical Profiling of Commercially Important South African PlantsОт EverandPhytochemical Profiling of Commercially Important South African PlantsОценок пока нет

- 5.Applied-HPhyto-chemical and Pharmacological Evaluation - Dr.G.panduranga MurthyДокумент26 страниц5.Applied-HPhyto-chemical and Pharmacological Evaluation - Dr.G.panduranga MurthyImpact JournalsОценок пока нет

- Herbal Remedies: A Comprehensive Guide to Herbal Remedies Used as Natural Antibiotics and AntiviralsОт EverandHerbal Remedies: A Comprehensive Guide to Herbal Remedies Used as Natural Antibiotics and AntiviralsОценок пока нет

- Herbal DrugДокумент33 страницыHerbal Drugdeepak_143Оценок пока нет

- Herbal Remedies: A Comprehensive Guide to Herbal Remedies Used as Natural Antibiotics and AntiviralsОт EverandHerbal Remedies: A Comprehensive Guide to Herbal Remedies Used as Natural Antibiotics and AntiviralsОценок пока нет

- Efficacy & Safety of Trad Plant MedicinesДокумент41 страницаEfficacy & Safety of Trad Plant MedicinesBiol. Miguel Angel Gutiérrez DomínguezОценок пока нет

- Pharmacovigilance of Herbal MedicineДокумент6 страницPharmacovigilance of Herbal MedicineMukesh Kumar ChaudharyОценок пока нет

- Research Papers Ethnomedicinal PlantsДокумент6 страницResearch Papers Ethnomedicinal Plantsafmchbghz100% (1)

- Standardization of Herbal Medicines - A ReviewДокумент12 страницStandardization of Herbal Medicines - A Reviewxiuhtlaltzin100% (1)

- Phytochemical Testing On Red GingerДокумент48 страницPhytochemical Testing On Red GingerIrvandar NurviandyОценок пока нет

- 5AADD0627363Документ11 страниц5AADD0627363Rasco Damasta FuОценок пока нет

- Challenges, Constraints and Opportunities in Herbal MedicinesДокумент4 страницыChallenges, Constraints and Opportunities in Herbal MedicinesGregory KalonaОценок пока нет

- Orgin of HerbalДокумент4 страницыOrgin of HerbalTapas MohantyОценок пока нет

- Published PaperДокумент6 страницPublished PaperDemoz AddisuОценок пока нет

- Daphne Plants Review Biological and Pharmacological ActivityДокумент12 страницDaphne Plants Review Biological and Pharmacological ActivityKrisman Umbu HengguОценок пока нет

- Introduction To HerbsДокумент32 страницыIntroduction To HerbsUngetable UnforgetableОценок пока нет

- 1.introduction PushpoДокумент11 страниц1.introduction PushpoMohiuddin HaiderОценок пока нет

- Art Medicinal Plants Toxic North and Central America PDFДокумент29 страницArt Medicinal Plants Toxic North and Central America PDFGabrielОценок пока нет

- Toxicity Evaluation of Methanol and Aqueous Leaf Extracts of Securinega virosa in Albino RatsДокумент34 страницыToxicity Evaluation of Methanol and Aqueous Leaf Extracts of Securinega virosa in Albino RatsPeter DindahОценок пока нет

- Palta As Contrceptive, AbutaДокумент12 страницPalta As Contrceptive, AbutaForgotten BreakerОценок пока нет

- Research ArticleДокумент17 страницResearch ArticleMarkos KumaОценок пока нет

- CHAPTER I, II, III (Scope and Limitation Unfinished)Документ31 страницаCHAPTER I, II, III (Scope and Limitation Unfinished)api-372852279% (47)

- Toxicity Review Natural ProductsДокумент5 страницToxicity Review Natural Productsamino12451Оценок пока нет

- Ethnomedicinal Survey of Plant Used in TreatmentДокумент59 страницEthnomedicinal Survey of Plant Used in TreatmentODUNTAN SULAIMONОценок пока нет

- The Growing Use of Herbal Medicines: Issues Relating To Adverse Reactions and Challenges in Monitoring SafetyДокумент10 страницThe Growing Use of Herbal Medicines: Issues Relating To Adverse Reactions and Challenges in Monitoring SafetyNancy KawilarangОценок пока нет

- A Quantitative Ethnobotanical Study of Common Herbal Remedies Used Against 13 Human Ailments Catergories in MauritiusДокумент33 страницыA Quantitative Ethnobotanical Study of Common Herbal Remedies Used Against 13 Human Ailments Catergories in MauritiusKristoff BerouОценок пока нет

- Role of Medicinal Plants in Disease Prevention StrategiesДокумент20 страницRole of Medicinal Plants in Disease Prevention Strategiesyahia yahiaОценок пока нет

- Current Status and Future of Herbal MedicineДокумент8 страницCurrent Status and Future of Herbal Medicinearci arsiespiОценок пока нет

- Uso Medicinal de Cordia LuteaДокумент12 страницUso Medicinal de Cordia LuteaBelen GonzalezОценок пока нет

- Amalraj 2016Документ14 страницAmalraj 2016prasannaОценок пока нет

- JPSR 12012020Документ7 страницJPSR 12012020windfragОценок пока нет

- Bioactive Medicinal Plants - D. Hota (Gene-Tech, 2007) WWДокумент277 страницBioactive Medicinal Plants - D. Hota (Gene-Tech, 2007) WWAlexandra Maris100% (2)

- Herbal Medicine: Current Status and The FutureДокумент8 страницHerbal Medicine: Current Status and The FuturexiuhtlaltzinОценок пока нет

- Review of Relat WPS OfficeДокумент3 страницыReview of Relat WPS OfficeArdiene Shallouvette GamosoОценок пока нет

- Article1380371399 - Okigbo Et AlДокумент10 страницArticle1380371399 - Okigbo Et AlDiannokaIhzaGanungОценок пока нет

- Research On DOH Approved Herbal MedicinesДокумент31 страницаResearch On DOH Approved Herbal Medicinesfilithesis79% (14)

- Toxicity Assessment of The Methanol Extract of Jatropha Tanjorensis (Euphorbiaceae) LeavesДокумент8 страницToxicity Assessment of The Methanol Extract of Jatropha Tanjorensis (Euphorbiaceae) Leavescamiladovalle95Оценок пока нет

- Article Text 506345 1 10 20201214Документ7 страницArticle Text 506345 1 10 20201214izy nicole bugalОценок пока нет

- Introduction 1 PDFДокумент7 страницIntroduction 1 PDFPawan KumarОценок пока нет

- Different Perception About Herbal MedicineДокумент40 страницDifferent Perception About Herbal MedicineMelody B. MiguelОценок пока нет

- Biological Activities and Medicinal Properties of GokhruДокумент5 страницBiological Activities and Medicinal Properties of GokhrusoshrutiОценок пока нет

- Chapter I, II, III-sept 9 (Badette)Документ26 страницChapter I, II, III-sept 9 (Badette)api-3728522100% (7)

- مواد الأيض الثانويДокумент22 страницыمواد الأيض الثانويMarwa BelaОценок пока нет

- Review ProjectДокумент71 страницаReview ProjectNeha ShuklaОценок пока нет

- A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis On The in Vitro Antiuroliathic Studies Utilizing Medicinal and Herbal PlantsДокумент19 страницA Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis On The in Vitro Antiuroliathic Studies Utilizing Medicinal and Herbal PlantsPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalОценок пока нет

- Review of Literature of Medicinal Plants in IndiaДокумент8 страницReview of Literature of Medicinal Plants in Indiagw10ka6s100% (1)

- Glorious PR FinalДокумент188 страницGlorious PR FinalJulie Silvenia100% (1)

- Herbal Drugs & Research Methodology: Dr. Yogendr BahugunaДокумент52 страницыHerbal Drugs & Research Methodology: Dr. Yogendr Bahugunashoaib naqviОценок пока нет

- Chapter I: IntroductionДокумент11 страницChapter I: IntroductionRobinhood Jevons MartirezОценок пока нет

- Bioactive Compounds in Phytomedicine BookДокумент228 страницBioactive Compounds in Phytomedicine BookAnil KumarОценок пока нет

- ETHNOBOTANICAL SURVEY OF MEDICINAL HERBS Original Published - Docx-With-Cover-Page-V2Документ6 страницETHNOBOTANICAL SURVEY OF MEDICINAL HERBS Original Published - Docx-With-Cover-Page-V2Rasco Damasta FuОценок пока нет

- PV of Herbals 34Документ1 страницаPV of Herbals 34rr48843Оценок пока нет

- Abjna 2 3 476 487Документ12 страницAbjna 2 3 476 487dana.trifanОценок пока нет

- Botany ProДокумент44 страницыBotany ProJishnu AОценок пока нет

- Research Papers Related To Medicinal PlantsДокумент4 страницыResearch Papers Related To Medicinal Plantsafeebjrsd100% (1)

- Traditional Medicinal Plants PhilippinesДокумент3 страницыTraditional Medicinal Plants PhilippinesGiana GregorioОценок пока нет

- Kadir2012 221121 183401Документ14 страницKadir2012 221121 183401Arie HanggaraОценок пока нет

- Health Implication and Complication of Herbal MedicineДокумент26 страницHealth Implication and Complication of Herbal Medicineigweonyia gabrielОценок пока нет

- Madre de Cacao S&TДокумент13 страницMadre de Cacao S&TJHEA MAE OGOTОценок пока нет

- OBAT 2021 SeptemberДокумент142 страницыOBAT 2021 SeptemberTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- OBAT 2021 SeptemberДокумент142 страницыOBAT 2021 SeptemberTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Anxiolytic Effects 0208-47-52Документ6 страницAnxiolytic Effects 0208-47-52Tony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Apple Margarine Lowers Cholesterol in MiceДокумент9 страницApple Margarine Lowers Cholesterol in MiceDhindien Shee ChildishmbembemОценок пока нет

- Stok Opname Etalase DistribusiДокумент2 страницыStok Opname Etalase DistribusiTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- ACAM Newsletter 9313 FeaturedArticle Jimenez PDFДокумент4 страницыACAM Newsletter 9313 FeaturedArticle Jimenez PDFTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- GOUTДокумент16 страницGOUTGabby RachediaОценок пока нет

- DAFTAR OBAT-WPS OfficeДокумент5 страницDAFTAR OBAT-WPS OfficeTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Narsum 1. Peran Vasodilator Beta BlockerFinalДокумент45 страницNarsum 1. Peran Vasodilator Beta BlockerFinalTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Fabel B Ing RamaДокумент3 страницыFabel B Ing RamaTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- 5 263zДокумент11 страниц5 263zDini HanifaОценок пока нет

- 2 PBДокумент6 страниц2 PBTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Kebijakan Kesehatan IndonesiaДокумент12 страницJurnal Kebijakan Kesehatan IndonesiaTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- 060 SridhaДокумент7 страниц060 SridhaTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Hepatotoxicity and Subchronic Toxicity Tests of Morinda Citrifolia (Noni) FruitДокумент2 страницыHepatotoxicity and Subchronic Toxicity Tests of Morinda Citrifolia (Noni) FruitTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- 3 Kali UjiДокумент6 страниц3 Kali UjiTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- 3 Kali UjiДокумент6 страниц3 Kali UjiTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Adam, 2004Документ3 страницыAdam, 2004Tony RamirezОценок пока нет

- 3 Kali UjiДокумент6 страниц3 Kali UjiTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Include ASP Exe News AttachmentДокумент3 страницыInclude ASP Exe News AttachmentTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Excel Tugas Bio PraktДокумент8 страницExcel Tugas Bio PraktTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- 2908 2275 1 SM PDFДокумент6 страниц2908 2275 1 SM PDFTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Nejmcp1003896 Mual Muntah PDFДокумент7 страницNejmcp1003896 Mual Muntah PDFTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Book 1Документ5 страницBook 1Tony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Current Concepts in The Diagnosis and Treatment of Typhoid FeverДокумент5 страницCurrent Concepts in The Diagnosis and Treatment of Typhoid FeverMohamed OmerОценок пока нет

- AlgoritmaДокумент8 страницAlgoritmaTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Excel Tgs PrakДокумент4 страницыExcel Tgs PrakTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Guidelines Manage Typhoid Fever OutbreaksДокумент39 страницGuidelines Manage Typhoid Fever OutbreaksNatasha ChandraОценок пока нет

- Kortiko 3Документ4 страницыKortiko 3Tony RamirezОценок пока нет

- WWW MedscapeДокумент12 страницWWW MedscapeTony RamirezОценок пока нет

- Critique On A Film Director's Approach To Managing CreativityДокумент2 страницыCritique On A Film Director's Approach To Managing CreativityDax GaffudОценок пока нет

- DMS-2017A Engine Room Simulator Part 1Документ22 страницыDMS-2017A Engine Room Simulator Part 1ammarОценок пока нет

- Digital Citizenship Initiative To Better Support The 21 Century Needs of StudentsДокумент3 страницыDigital Citizenship Initiative To Better Support The 21 Century Needs of StudentsElewanya UnoguОценок пока нет

- Mythic Magazine 017Документ43 страницыMythic Magazine 017William Warren100% (1)

- Nature and Scope of Marketing Marketing ManagementДокумент51 страницаNature and Scope of Marketing Marketing ManagementFeker H. MariamОценок пока нет

- Practical LPM-122Документ31 страницаPractical LPM-122anon_251667476Оценок пока нет

- Hastrof Si Cantril. 1954. The Saw A Game. A Case StudyДокумент6 страницHastrof Si Cantril. 1954. The Saw A Game. A Case Studylandreea21Оценок пока нет

- Indian Institute OF Management, BangaloreДокумент20 страницIndian Institute OF Management, BangaloreGagandeep SinghОценок пока нет

- Mole Concept - DPP 09 (Of Lec 13) - Yakeen 2.0 2024 (Legend)Документ3 страницыMole Concept - DPP 09 (Of Lec 13) - Yakeen 2.0 2024 (Legend)Romeshchandra Class X-CОценок пока нет

- The Polynesians: Task1: ReadingДокумент10 страницThe Polynesians: Task1: ReadingHəşim MəmmədovОценок пока нет

- English Skills BookДокумент49 страницEnglish Skills BookAngela SpadeОценок пока нет

- IE399 Summer Training ReportДокумент17 страницIE399 Summer Training ReportgokanayazОценок пока нет

- Storytelling ScriptДокумент2 страницыStorytelling ScriptAnjalai Ganasan100% (1)

- Shimano Brakes ManualДокумент36 страницShimano Brakes ManualKon Arva100% (1)

- Wsi PSDДокумент18 страницWsi PSDДрагиша Небитни ТрифуновићОценок пока нет

- Phys114 Ps 1Документ11 страницPhys114 Ps 1Reine Amabel JarudaОценок пока нет

- Health Information System Developmen T (Medical Records)Документ21 страницаHealth Information System Developmen T (Medical Records)skidz137217100% (10)

- Ilham Bahasa InggrisДокумент12 страницIlham Bahasa Inggrisilhamwicaksono835Оценок пока нет

- ArtigoPublicado ABR 14360Документ14 страницArtigoPublicado ABR 14360Sultonmurod ZokhidovОценок пока нет

- LGFL Service GuideДокумент24 страницыLGFL Service GuideThe Return of the NoiristaОценок пока нет

- E PortfolioДокумент76 страницE PortfolioMAGALLON ANDREWОценок пока нет

- Understand Azure Event HubsДокумент12 страницUnderstand Azure Event HubselisaОценок пока нет

- Analysis of VariancesДокумент40 страницAnalysis of VariancesSameer MalhotraОценок пока нет

- Overview for Report Designers in 40 CharactersДокумент21 страницаOverview for Report Designers in 40 CharacterskashishОценок пока нет

- Wika Type 111.11Документ2 страницыWika Type 111.11warehouse cikalongОценок пока нет

- Where On Earth Can Go Next?: AppleДокумент100 страницWhere On Earth Can Go Next?: Applepetrushevski_designeОценок пока нет

- Types of LogoДокумент3 страницыTypes of Logomark anthony ordonioОценок пока нет

- CH - 3Документ3 страницыCH - 3Phantom GamingОценок пока нет

- Brooks Instrument FlowmeterДокумент8 страницBrooks Instrument FlowmeterRicardo VillalongaОценок пока нет

- Electrocardiography - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaДокумент18 страницElectrocardiography - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediapayments8543Оценок пока нет