Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Genealogies of Religion

Загружено:

T Anees AhmadАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Genealogies of Religion

Загружено:

T Anees AhmadАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Genealogies of Religion, Twenty Years On: An Interview with

Talal Asad

Posted on March 12, 2014 by mattsheedy

The following is part of an interview conducted by Craig Martin with Talal Asad, which

appears in the February issue of the Bulletin for the Study of Religion, Vol. 43, No. 1

(2014). To read the full interview, please follow the link to order a copy of the journal or

to read it on-line.

Craig Martin: Last fall, realizing that 2013 marked the twentieth anniversary of Talal

Asads Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and

Islam, I interviewed Talal AsadDistinguished Professor of Anthropology at The City

University of New Yorkon the book and its reception and influence on the

field.Genealogies of Religion influenced me early in my graduate studiesparticularly

the first chapter on The Construction of Religion as an Anthropological Category, in

which Asad argues that the concept of religion is, in many contemporary contexts,

fundamentally shaped by Protestant assumptions. This was one of the first books I was

exposed to that argued there is normative work accomplished by the very term

religion, and all of my writings since have taken this idea as a central starting point. I

want to thank Asad for taking the time to answer the questions I posed to him.

Craig Martin: Can you discuss what you most hoped to accomplish with Genealogies

of Religion? Do you think the book was received in the way you hoped it would be?

Talal Asad: As far as I can tell, most people have understood that I was trying to think

about religion as practice, language, and sensibility set in social relationships rather

than as systems of meaning. In that book and much of my subsequent work I have tried

to think through small pieces of Christian and Islamic history to enlarge my own

understanding of what and how people live when they use the vocabulary of religion. I

certainly did not want to claim that as a historical construct religion was a reference to

an absence, a mere ideology expressing dominant power. It was precisely because I was

dissatisfied with the classical Marxist notion of ideology that I turned my attention to

religion. I was gradually coming to understand that the question I needed to think about

was how learning a particular language game was articulated with a particular form of

life, as Wittgenstein would say. The business of defining religion is part of that larger

question of the infinite ways language enters life. I wanted to get away from arguments

that draw on or offer essential definitions: Religion is a response to a human need,

Religion may be a comfort to people in distress but it asserts things that arent true,

Religion is essentially about the sacred, Religion gives meaning to life, Religion and

science are compatible/incompatible, Religion is responsible for great evil, So is

science and religion is also a source of much good, No, science is not a source of evil,

as religion often is; it is technology and politics that are the problemthe social use to

which science is put.

I argued that to define religion is to circumscribe certain things (times, spaces,

powers, knowledges, beliefs, behaviors, texts, songs, images) as essential to religion,

and other things as accidental. This identifying work of what belongs to a definition isnt

done as a consequence of the same experiencethe things themselves are diverse, and

the way people react to them or use them is very different. Put it this way: when they are

identified by the concept religion, it is because they are seen to be significantly similar;

what makes them similar is not a singular experience common to all the things the

concept brings together (sacrality, divinity, spirituality, transcendence, etc.); what

makes them similar is the definition itself that persuades us, through what Wittgenstein

called a captivating picture, that there is an essence underlying them allin all

instances of religion.

The things regarded as hanging together according to one conception of religion come

together very differently in another. Thats why the translation of one religious

concept into another is always problematic. But Genealogies doesnt argue that the

definition of religion is merely a matter of linguistic representation. Religious

languagelike all languageis interwoven with life itself. To define religion is

therefore in a sense to try and grasp an ungraspable totality. And yet I nowhere say that

these definitions are abstract propositions. I stress that definitions of religion are

embedded in dialogs, activities, relationships, and institutions that are lovingly or

casually maintainedor betrayed or simply abandoned. They are passionately fought

over and pronounced upon by the authoritative law of the state.

Definitions of religion are not single, completed definitive acts; they extend over time

and work themselves through practices. They are modified and elaborated with

continuous use. To the extent that defining religion is a religious act, whether carried

out by believers or nonbelievers, it may also be an attempt at attacking or reinforcing

an existing religious tradition, at reforming it or initiating a new one.

My problem with universal definitions of religion, therefore, has been that by insisting

on a universal essence they divert us from asking questions about what the definition

includes and what it excludes, how, by whom, for what purpose; about what

social/linguistic context it makes good sense to propound a given definition and when it

doesnt.

Trying to construct genealogies of concepts is one way of getting at such questions. For

me the most important concern in all my writing has been, What, in this matter, is the

right question? So in Genealogies of Religion I did not try to provide a better definition

of religion, still less to undermine the very concept of religion. I was looking for ways

of formulating the most fruitful questions about how people enact, declare, commit to

or repudiatethings when they talk about religion. Thus in Chapter 4, in my

exploration of Hugh of St. Victors account of the sacraments, and of Bernard of

Clairvauxs monastic sermons, I tried to get away from notions like inculcation, a

passive reception of dominating power, and to move towards something more complex.

Thus I wrote, Bernard is not manipulating desires (in the sense that his monks did not

know what was happening to them) but instead creating a new moral space for the

operation of a distinctive motivation. What interested me was how such subjective

processes related to embodiment and disciplineor put differently, how objective

conditions in which subjects find themselves enable them to decide what one must

think, how one can live, and how one is able to live. This was the project I was engaged

in when I wrote the essays making upGenealogies, and this is what Im still engaged in. I

dont think of that book in isolation from my other work.

Many readers have understood what I was trying to do and sympathized (even if

guardedly) with my effort. Some havent. It has even been alleged by the latter, to my

surprise, that I am hostile to religion, and especially to the Christian religion, and that

I developed my hostility during my childhood when I was supposedly humiliated at

boarding school run by missionaries (in India)because I once referred to that period in

my early schooldays as the time when I learnt to argue, to be combative, with my

Christian schoolmates! I was never humiliated by Christian missionaries and never

said I was. More important: anyone who has read Genealogies of Religion with some

attention surely cant make sense of that claim. In fact Ive learnt much about the

complexity of religion by reading Christian writers belonging to different historical

periods. I certainly dont think that when people use a religious vocabulary they are

really talking about mere constructionsabout ideological formations whose role is to

provide justification for social domination. Of course something is constructed, and

reconstructed, but this construction is not teleological (made and completed for a

specific purpose), and it is not properly described as essentially social. That kind of

functionalism is precisely what I wanted to get away from in Genealogies.

CM: Could you comment on the different reactions to your work by other disciplines or

sub-disciplines? Im familiar with how religious studies scholars have reacted to

your work, but do you feel that this work has made the impact you hoped it would in, for

example, anthropology, political sciences, sociology, as well as the diverse areas of

religious studies?

TA: I really dont know what impact Genealogies has had in the social sciences

generally. I know that a number of talented young anthropologists have taken up the

idea of embodiment, of sensibilities, of tradition, and of virtue ethics in their

ethnography of Islam. They have recently been criticized by some people for

exaggerating the importance of formal religiosity at the expense of ordinary spiritual

beliefs and I have been blamed for having started this bad tendencyand then carried

it on into a reactionary view of secularism. This is not the place to engage with their

complaints, especially because they largely concern the anthropology of Islamand so

they are focused more on an earlier essay of mine as well as on Formations of the

Secular. I gather that many sociologists and anthropologists studying Muslim

immigrants in Europe feel that my work is perversely normative, that it deliberately

ignores the reality of the social experience of Muslims and their religious responsein

short, that it overlooks their modern predicament in secular liberal countries. Thats one

kind of reaction to my work, I suppose. But I am curious as to why they feel so strongly

that my work threatens their truth. When I was an anthropology student we used to joke

about senior ethnographers who responded to theoretical arguments in seminars by

interrupting, But in my tribe people believed . . . This kind of empiricism is still,

unfortunately, with us. Many ethnographers think that they have a proper

understanding of their informants experience (and therefore of their religious belief or

disbelief) by virtue of the fact that they have spent some (limited) time with them in

their form of lifeas if the experience of their informants was homogeneous, complete

and consistent, as if their form of life (shared briefly by the ethnographer) could be

summed up in a representation reflecting an indisputable reality and was not itself an

internally ambiguous interpretation, and as if their ordinary language was more

authentic than the language of their theological texts.

At any rate, there has been greater interest in Formations than Genealogies of

Religionamong political scientists, although I see the former book as closely connected

to the latter and its questions about secularism more developed than they are

in Genealogies. This interest is, I suppose, due to questions of pain, violence, and

suffering that I share with some of them. They already know that things are not as

simple as some versions of liberal ideology claim they are.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- (Un) Making Idolatry From Mecca To BamiyanДокумент19 страниц(Un) Making Idolatry From Mecca To BamiyanT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- M Hamidullah Early Life and BackgroundДокумент1 страницаM Hamidullah Early Life and BackgroundT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Genealogies of ReligionДокумент5 страницGenealogies of ReligionT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Future of Islam in The West - M Al-GhazalyДокумент74 страницыFuture of Islam in The West - M Al-GhazalyT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Boy With Cerebral Palsy Learns To Sit UpДокумент1 страницаBoy With Cerebral Palsy Learns To Sit UpT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Islam Is Submission To The Will of GodДокумент1 страницаIslam Is Submission To The Will of GodT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Islam Is Aworldly ReligionДокумент1 страницаIslam Is Aworldly ReligionT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- M Hamidullah CareerДокумент1 страницаM Hamidullah CareerT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Hamidullah YaadenДокумент4 страницыHamidullah YaadenT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Books by DR M HamidullahДокумент1 страницаBooks by DR M HamidullahT Anees Ahmad100% (1)

- Hamidullah YaadenДокумент4 страницыHamidullah YaadenT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- See Also: Contemporary Islamic Philosophy Islamism Jamia NizamiaДокумент1 страницаSee Also: Contemporary Islamic Philosophy Islamism Jamia NizamiaT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- M Hamidullah MemoirsДокумент4 страницыM Hamidullah MemoirsT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- DR Hamidullah Great ScholarДокумент2 страницыDR Hamidullah Great ScholarT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- DR Hamidullah Passes AwayДокумент2 страницыDR Hamidullah Passes AwayT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- DR Hamidullah Passes AwayДокумент2 страницыDR Hamidullah Passes AwayT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Remember Dr. HamidullahДокумент4 страницыRemember Dr. HamidullahT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Biographical Data DR HamidullahДокумент1 страницаBiographical Data DR HamidullahT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- M Hamidullah ScholarshipДокумент1 страницаM Hamidullah ScholarshipT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Obituary Dr. M HamidullahДокумент2 страницыObituary Dr. M HamidullahT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Asad The Muslim ObserverДокумент2 страницыAsad The Muslim ObserverT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Remembering DR M HamidullahДокумент6 страницRemembering DR M HamidullahT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Fethullah Gülen - An Analysis of The Prophet's Life (The Messenger of God: Muhammad)Документ455 страницFethullah Gülen - An Analysis of The Prophet's Life (The Messenger of God: Muhammad)gamirov100% (11)

- Muhammad Hamidullah SpiritualДокумент14 страницMuhammad Hamidullah SpiritualT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- #2065 10th Cross, Maruthi Tent Road, Janatha Nagar, MysoreДокумент1 страница#2065 10th Cross, Maruthi Tent Road, Janatha Nagar, MysoreT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- DR M HamiduullahДокумент5 страницDR M HamiduullahT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Professor M HamidullahДокумент1 страницаProfessor M HamidullahT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Full Text of The Madina CharterДокумент7 страницFull Text of The Madina CharterT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- I Too Have Serious Reservations Regarding The Political Vision Which Gandhi EnvisagedДокумент1 страницаI Too Have Serious Reservations Regarding The Political Vision Which Gandhi EnvisagedT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Cognitive ElementsДокумент7 страницCognitive Elementssolidus400Оценок пока нет

- In Human HistoryДокумент3 страницыIn Human HistoryMa. Kyla Wayne LacasandileОценок пока нет

- Effects of Playing Online Games On The Academic Performance of Grade 12 Abm Students of Lspu in First SemesterДокумент10 страницEffects of Playing Online Games On The Academic Performance of Grade 12 Abm Students of Lspu in First SemesterMike OngОценок пока нет

- Computers in Human Behavior: Tobias GreitemeyerДокумент4 страницыComputers in Human Behavior: Tobias GreitemeyerIvan MaulanaОценок пока нет

- Mindfulness at Work A New Approach To Improving Individual and Organizational PerformanceДокумент27 страницMindfulness at Work A New Approach To Improving Individual and Organizational Performancedongxing zhouОценок пока нет

- Pemberton Happiness Index PDFДокумент13 страницPemberton Happiness Index PDFIesanu MaraОценок пока нет

- Skimming For Key Ideas and Author's PurposeДокумент28 страницSkimming For Key Ideas and Author's PurposeJournaling GailОценок пока нет

- World Mental Health Day 2019: Presentation of Theme by Mrs. Sumam, Assistant Professor, SGNCДокумент57 страницWorld Mental Health Day 2019: Presentation of Theme by Mrs. Sumam, Assistant Professor, SGNCSumam NeveenОценок пока нет

- PROPAGANDAДокумент5 страницPROPAGANDAKate Benedicto-Agustin0% (1)

- Brain CureДокумент157 страницBrain CureJosh BillОценок пока нет

- Factors Affecting BilingualismДокумент10 страницFactors Affecting Bilingualism黃婷婷Оценок пока нет

- Cdep Theory of ArchitectureДокумент8 страницCdep Theory of ArchitectureKitz YoОценок пока нет

- Family Scenario ProjectДокумент13 страницFamily Scenario Projectapi-265296849100% (2)

- Richard Lowell Hittleman - Richard Hittleman's Guide To Yoga Meditation (1974 (1969), Bantam Books)Документ196 страницRichard Lowell Hittleman - Richard Hittleman's Guide To Yoga Meditation (1974 (1969), Bantam Books)Purushottam Kumar100% (2)

- Aquinas AbstractionДокумент13 страницAquinas AbstractionDonpedro Ani100% (2)

- Her Sey and Blanchards Leadership QuestionnaireДокумент3 страницыHer Sey and Blanchards Leadership Questionnairesmanikan030% (1)

- Nature Walk Lesson PlanДокумент7 страницNature Walk Lesson PlanKatelin SchroederОценок пока нет

- Metacognitive Reading and Annotating - The Banking Concept of EducationДокумент5 страницMetacognitive Reading and Annotating - The Banking Concept of Educationapi-381131284100% (1)

- Com569 Final To Check Com569 Final To CheckДокумент37 страницCom569 Final To Check Com569 Final To CheckNURUL HAZIQAH MD BADRUL HISHAMОценок пока нет

- Child Growth and DevelopmentДокумент16 страницChild Growth and DevelopmentNiyonzimaОценок пока нет

- List of Education Books 2019-220Документ151 страницаList of Education Books 2019-220Kairmela PeriaОценок пока нет

- First 90 DaysДокумент13 страницFirst 90 Dayssgeorge23100% (2)

- Research Methodology 1 Unit NotesДокумент18 страницResearch Methodology 1 Unit NotesKaviyaDevanandОценок пока нет

- High-Quality Feedback Calibration Participant PacketДокумент5 страницHigh-Quality Feedback Calibration Participant PacketDamion BrusselОценок пока нет

- Neuropsychology of CommunicationДокумент13 страницNeuropsychology of Communicationkhadidja BOUTOUILОценок пока нет

- CGP Module 7Документ12 страницCGP Module 7Victor Moraca SinangoteОценок пока нет

- Macionis 15 C02 EДокумент40 страницMacionis 15 C02 EXUANN RUE CHANОценок пока нет

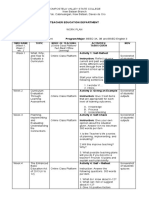

- (Week 1, Week 2, Etc ) (Online Class Platform/ Text Blast/ Offline Learning)Документ3 страницы(Week 1, Week 2, Etc ) (Online Class Platform/ Text Blast/ Offline Learning)Joy ManatadОценок пока нет

- Lecture and Discussion Schedule of Topics (Subject To Change) A Note On The LecturesДокумент3 страницыLecture and Discussion Schedule of Topics (Subject To Change) A Note On The Lecturesishtiaque_anwarОценок пока нет

- Büttner Ma BmsДокумент27 страницBüttner Ma BmsVon Gabriel GarciaОценок пока нет