Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Human Sacrifice

Загружено:

Emry Kamahi Tahatai KereruАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Human Sacrifice

Загружено:

Emry Kamahi Tahatai KereruАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Human sacrifice

1

Human sacrifice

For the Vengeance Rising's album, see Human Sacrifice (album).

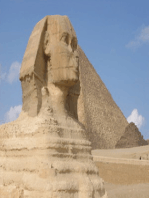

This page from the Codex Tovar depicts a scene

of gladiatorial sacrificial rite, celebrated on the

festival of Tlacaxipehualiztli.

Part of a series on

Homicide

Murder

Note: Varies by jurisdiction

Assassination

Child murder

Consensual homicide

Contract killing

Crime of passion

Depraved-heart murder

Double murder

Execution-style killing

Felony murder rule

Feticide

Honor killing

Human sacrifice

Child

Lust murder

Lynching

Mass murder

Misdemeanor murder

Murdersuicide

Proxy murder

Pseudocommando

Lonely hearts killer

Serial killer

Spree killer

Internet homicide

Manslaughter

In English law

Negligent homicide

Vehicular homicide

Non-criminal homicide

Human sacrifice

2

Note: Varies by jurisdiction

Euthanasia

Assisted suicide

Capital punishment

Feticide

Human sacrifice

Justifiable homicide

War

By victim or victims

Suicide

Family

Familicide

Avunculicide

Prolicide

Filicide

Infanticide

Neonaticide

Fratricide

Mariticide

Sororicide

Uxoricide

Parricide

Matricide

Patricide

Other

Capital punishment

Democide

Friendly fire

Genocide

Gendercide

Omnicide

Regicide

Tyrannicide

v

t

e

[1]

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more human beings, usually as an offering to a deity, as part of a

religious ritual. Its typology closely parallels the various practices of ritual slaughter of animals and of religious

sacrifice in general. Human sacrifice has been practiced in various cultures throughout history. Victims were

typically ritually killed in a manner that was supposed to please or appease gods, spirits or the deceased, for example

as a propitiatory offering, or as a retainer sacrifice when the King's servants are killed in order for them to continue

to serve their master in the next life. Closely related practices found in some tribal societies are cannibalism and

headhunting. By the Iron Age, with the associated developments in religion (the Axial Age), human sacrifice was

becoming less common throughout the Old World, and came to be looked down upon as barbaric in pre-modern

times (Classical Antiquity). Blood libel is a false charge of ritual directed against the Jewish community by

Christians in the Middle Ages, and the idea spread to other communities subsequently. This has subsequently been

shown to be entirely without foundation, however it played a major role in the entrenchment of anti-semitic ideas.

Human sacrifice

3

In modern times, even the practice of animal sacrifice has virtually disappeared from all major religions (or has been

re-cast in terms of ritual slaughter), and human sacrifice has become extremely rare. Most religions condemn the

practice, and present-day secular laws treat it as murder. In a society which condemns human sacrifice, the term

ritual murder is used.

Evolution and context

Further information: Origin of religion, Magical thinking, Anthropology of religion, Homo Necans, The Golden

Bough, Life-death-rebirth deity and Crucifixion of Jesus

The idea of human sacrifice has its roots in deep prehistory, in the evolution of human behaviour. From its historical

occurrences it seems mostly associated with neolithic or nomadic cultures, on the emergent edge of civilization.

Mythologically, it is closely connected with animal sacrifice. Walter Burkert has argued for such a fundamental

identity of animal and human sacrifice in the connection of a hunting hypothesis which traces the emergence of

human religious behaviour to the beginning of behavioural modernity in the Upper Paleolithic (roughly 50,000 years

ago).

The Ashanti yam festival, early 19th century

Human sacrifice has been practiced on a number of different occasions

and in many different cultures. The various rationales behind human

sacrifice are the same that motivate religious sacrifice in general.

Human sacrifice is intended to bring good fortune and to pacify the

gods, for example in the context of the dedication of a completed

building like a temple or bridge. There is a Chinese legend that there

are thousands of people entombed in the Great Wall of China.

In ancient Japan, legends talk about hitobashari ("human pillar"), in

which maidens were buried alive at the base or near some

constructions to protect the buildings against disasters or enemy

attacks, and an almost identical trope/motif appears in the Serbian epic poem The Building of Skadar where a

sacrifice of a young mother still nursing her child will keep the city of Skadar (today Shkodr in the northern tip of

Albania) walls from an evil Vila.

[2][3]

For the re-consecration of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in 1487, the Aztecs reported that they killed about

80,400 prisoners over the course of four days. According to Ross Hassig, author of Aztec Warfare, "between 10,000

and 80,400 persons" were sacrificed in the ceremony.

[4]

Human sacrifice can also have the intention of winning the gods' favour in warfare. In Homeric legend, Iphigeneia

was to be sacrificed by her father Agamemnon for success in the Trojan War. According to the Bible, Jephthah

vowed to devote to God the first creature to come out of his house to meet him if he won the battle against the

Ammonites. Judges 11:30-31; "And Jephthah vowed a vow unto the Lord, and said, If thou shalt without fail deliver

the children of Ammon into mine hands, Then it shall be, that whatsoever cometh forth of the doors of my house to

meet me, when I return in peace from the children of Ammon, shall surely be the Lord's, and I will Him a burnt

offering." His daughter was the first to come out and meet him. Judges 11:34; "And Jephthah came to Mizpeh unto

his house, and, behold, his daughter came out to meet him with timbrels and with dances: and she was his only child;

beside her he had neither son nor daughter." The Bible elsewhere condemns child sacrifice. Deut 18:10 explicitly

states "Let no one be found among you who sacrifices their son or daughter in the fire". Jer 7:31 states that

sacrificing a child by fire, even to Him, had never been commanded nor entered God's mind.

In some notions of an afterlife, the deceased will benefit from victims killed at his funeral. Mongols, Scythians, early

Egyptians and various Mesoamerican chiefs could take most of their household, including servants and concubines,

with them to the next world. This is sometimes called a "retainer sacrifice", as the leader's retainers would be

sacrificed along with their master, so that they could continue to serve him in the afterlife.

Human sacrifice

4

Hawaiian sacrifice, from Jacques Arago's account

of Freycinet's travels around the world from 1817

to 1820.

Another purpose is divination from the body parts of the victim.

According to Strabo, Celts stabbed a victim with a sword and divined

the future from his death spasms.

Headhunting is the practice of taking the head of a killed adversary, for

ceremonial or magical purposes, or for reasons of prestige. It was

found in many pre-modern tribal societies.

Human sacrifice may be a ritual practiced in a stable society, and may

even be conductive to enhance societal bonds (see: Sociology of

religion), both by creating a bond unifying the sacrificing community,

and in combining human sacrifice and capital punishment, by

removing individuals that have a negative effect on societal stability

(criminals, religious heretics, foreign slaves or prisoners of war). But outside of civil religion, human sacrifice may

also result in outbursts of "blood frenzy" and mass killings that destabilize society. The bursts of capital punishment

during European witch-hunts, or during the French Revolutionary Reign of Terror show similar sociological

patterns

[citation needed]

(see also Moral panic).

Many cultures show traces of prehistoric human sacrifice in their mythologies and religious texts, but ceased the

practice before the onset of historical records. Some see the story of Abraham and Isaac (Genesis 22) as an example

of an etiological myth explaining the abolition of human sacrifice. The Vedic Purushamedha (literally "human

sacrifice") is already a purely symbolic act in its earliest attestation. According to Pliny the Elder, human sacrifice in

Ancient Rome was abolished by a senatorial decree in 97 BCE, although by this time the practice had already

become so rare that the decree was mostly a symbolic act. Human sacrifice once abolished is typically replaced by

either animal sacrifice, or by the "mock-sacrifice" of effigies, such as the Argei in ancient Rome.

History by region

Ancient Near East

Further information: Religions of the Ancient Near East and Minoan religion Possibility of human sacrifice

Ancient Egypt

Further information: Ancient Egyptian retainer sacrifices

There may be evidence of retainer sacrifice in the early dynastic period at Abydos, when on the death of a King he

would be accompanied with servants, and possibly high officials, who would continue to serve him in eternal life.

The skeletons that were found had no obvious signs of trauma, leading to speculation that the giving up of life to

serve the King may have been a voluntary act, possibly carried out in a drug induced state. At about 2800 BCE any

possible evidence of such practices disappeared, though echoes are perhaps to be seen in the burial of statues of

servants in Old Kingdom tombs.

Mesopotamia

Retainer sacrifice was practised within the royal tombs of ancient Mesopotamia. Courtiers, guards, musicians,

handmaidens and grooms died, presumed to have taken poison. A new examination of skulls from the royal cemetery

at Ur, discovered in Iraq almost a century ago, appears to support a more grisly interpretation of human sacrifices

associated with elite burials in ancient Mesopotamia than had previously been recognized, say archaeologists. Palace

attendants, as part of royal mortuary ritual, were not dosed with poison to meet death serenely. Instead, a sharp

instrument such as a pike was driven into their heads.

Human sacrifice

5

Levant

Further information: Binding of Isaac

References in the Bible point to an awareness of human sacrifice in the history of ancient near-eastern practice.

During a battle with the Israelites the king of Moab gives his firstborn son and heir as a whole burnt offering (olah,

as used of the Temple sacrifice) (2 Kings 3:27).

[5]

In Genesis 22 as well as the Qur'an, there is a story about Abraham's binding of Isaac, although in the Qur'an the

name of the son is not mentioned and assumed to be Ismail. In both the Qur'an's and Bible's version of the story, God

tests Abraham by asking him to present his son, Isaac, as a sacrifice on Mount Moriah. Abraham agrees to this

command without arguing. The story ends with an angel stopping Abraham at the last minute and making Isaac's

sacrifice unnecessary by providing a ram, caught in some nearby bushes, to be sacrificed instead. Many Bible

scholars have suggested this story's origin was a remembrance of an era when human sacrifice was abolished in

favour of animal sacrifice.

Another possible instance of human sacrifice mentioned in the Bible is the sacrifice of Jephthah's daughter in Judges

11. Jephthah vows to sacrifice to God whatsoever comes to greet him at the door when he returns home if he is

victorious. The vow is stated in Judges 11:31 as "Then it shall be, that whatsoever cometh forth of the doors of my

house to meet me, when I return in peace from the children of Ammon, shall surely be the Lord's, and I will offer

Him a burnt offering." When he returns from battle, his virgin daughter runs out to greet him. She begs for, and is

granted, "two months to roam the hills and weep with my friends", after which "he [Jephthah] did to her as he had

vowed." According to some commentators of the rabbinic Jewish tradition, Jepthah's daughter was not sacrificed, but

was forbidden to marry and remained a spinster her entire life, fulfilling the vow that she would be devoted to the

Lord.

[6]

Phoenicia

According to Roman and Greek sources, Phoenicians and Carthaginians sacrificed infants to their gods. The bones of

numerous infants have been found in Carthaginian archaeological sites in modern times but the subject of child

sacrifice is controversial.Wikipedia:Link rot In a single child cemetery called the Tophet by archaeologists, an

estimated 20,000 urns were deposited.

[7]

Plutarch (ca. 46120 CE) mentions the practice, as do Tertullian, Orosius, Diodorus Siculus and Philo. Livy and

Polybius do not. The Bible asserts that children were sacrificed at a place called the Tophet ("roasting place") to the

god Moloch. According to Diodorus Siculus' account of the Carthaginians:

There was in their city a bronze image of Cronus extending its hands, palms up and sloping toward the ground, so that each of the children

when placed thereon rolled down and fell into a sort of gaping pit filled with fire.

Plutarch, however claims that the children were already dead at the time, having been killed by their parents, whose

consentas well as that of the childrenwas required; Tertullian explains the acquiescence of the children as a

product of their youthful trustfulness.

The accuracy of such stories is disputed by some modern historians and archaeologists.

[8]

Human sacrifice

6

Europe

The sacrifice of Polyxena by the triumphant

Greeks, Trojan War, c. 570-550 BC

Neolithic Europe

Further information: Neolithic religion

There is archaeological evidence of human sacrifice in Neolithic to

Eneolithic Europe. Retainer sacrifices seem to have been common in

early Indo-European religion. For example, the Luhansk sacrificial site

shows evidence of human sacrifice in the Yamna culture.

Greco-Roman antiquity

Further information: Ancient Greek religion and Ancient Roman

religion

The Sacrifice of Iphigeneia, a mythological

depiction of a sacrificial procession on a mosaic

from Roman Spain

References to human sacrifice can be found in Greek historical

accounts as well as mythology. In the Histories, Herodotus talks about

sacrifice of victims by the Athenians at the Acropolis, during the

second Greco-Persian war in 480 BC.

[9]

The human sacrifice in

mythology, the deus ex machina salvation in some versions of

Iphigeneia (who was about to be sacrificed by her father Agamemnon)

and her replacement with a deer by the goddess Artemis, may be a

vestigial memory of the abandonment and discrediting of the practice

of human sacrifice among the Greeks in favour of animal sacrifice.

In ancient Rome, human sacrifice was infrequent but documented.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus says that the ritual of the Argei, in which

straw figures were tossed into the Tiber river, may have been a

substitute for an original offering of elderly men. After the Roman

defeat at Cannae two Gauls and two Greeks in male-female couples

were buried under the Forum Boarium, in a stone chamber used for the

purpose at least once before.

[10]

The rite was apparently repeated in

113 BC, preparatory to an invasion of Gaul.

[11]

According to Pliny the Elder, human sacrifice was banned by law

during the consulship of Publius Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus in 97 BCE, although by this time it

was so rare that the decree was largely symbolic.

[12]

Captured enemy leaders were only occasionally executed at the

conclusion of a Roman triumph, and the Romans themselves did not consider these deaths a sacrificial

offering.

[citation needed]

Gladiator combat was thought by the Romans to have originated as fights to the death among

war captives at the funerals of Roman generals, and Christian polemicists such as Tertullian considered deaths in the

arena to be little more than human sacrifice.

[13]

Human sacrifice

7

Celts

A wicker man, that, according to Caesar, was

used to sacrifice humans to the gods.

According to Roman sources, Celtic Druids engaged extensively in

human sacrifice. According to Julius Caesar, the slaves and dependents

of Gauls of rank would be burnt along with the body of their master as

part of his funerary rites. He also describes how they built wicker

figures that were filled with living humans and then burned. According

to Cassius Dio, Boudica's forces impaled Roman captives during her

rebellion against the Roman occupation, to the accompaniment of

revelry and sacrifices in the sacred groves of Andate. Different gods

reportedly required different kinds of sacrifices. Victims meant for

Esus were hanged, those meant for Taranis immolated and those for

Teutates drowned. Some, like the Lindow Man, may have gone to their

deaths willingly.

Contradicting the Roman sources, more recent scholarship finds that

"there is little archeological evidence" of human sacrifice by the Celts,

and suggests the likelihood that Greeks and Romans disseminated

negative information out of disdain for the barbarians. There is no

evidence of the practices Caesar described, and the stories of human

sacrifice appear to derive from a single source, Poseidonius, whose

claims are unsupported.

Archaeological evidence from the British Isles seems to indicate that human sacrifice may have been practised, over

times long pre-dating any contact with Rome. Human remains have been found at the foundations of structures from

the Neolithic time to the Roman era, with injuries and in positions that argue for their being foundation

sacrifices.

[citation needed]

Skeletons belonging to as many as 150 people and dating back to about the time of the Roman conquest were

discovered in Alveston, England.

[14]

Ritualised decapitation survives in the archaeological record such as the example of 12 headless corpses at the

French late Iron Age sanctuary of Gournay-sur-Aronde.

[15]

Germanic peoples

Further information: Germanic paganism and bog body

Human sacrifice was not a particularly common occurrence among the Germanic peoples, being resorted to in

exceptional situations arising from crises of an environmental (crop failure, drought, famine) or social (war) nature,

often thought to derive at least in part from the failure of the king to establish and/or maintain prosperity and peace

(rs ok friar) in the lands entrusted to him.

[16]

In later Scandinavian practice, human sacrifice appears to have

become more institutionalised, and was repeated as part of a larger sacrifice on a periodic basis (according to Adam

of Bremen every nine years).

[17]

Evidence of Germanic practices of human sacrifice predating the Viking Age depend on archaeology and on a few

scattered accounts in Greco-Roman ethnography. For example, Tacitus reports Germanic human sacrifice to (what

he interprets as) Mercury, and to Isis specifically among the Suebians. Jordanes reports how the Goths sacrificed

prisoners of war to Mars, suspending the severed arms of the victims from the branches of trees.

By the 10th century, Germanic paganism had become restricted to Scandinavia. One account by Ahmad ibn Fadlan

as part of his account of an embassy to the Volga Bulgars in 921 claims that Norse warriors were sometimes buried

with enslaved women with the belief that these women would become their wives in Valhalla. In his description of

the funeral of a Scandinavian chieftain, a slave volunteers to die with a Norseman. After ten days of festivities, she is

Human sacrifice

8

stabbed to death by an old woman, a sort of priestess who is referred to as Vlva or "Angel of Death", and burnt

together with the deceased in his boat. This practice is evidenced archaeologically, with many male warrior burials

(such as the ship burial at Balladoole on the Isle of Man, or that at Oseberg in Norway) also containing female

remains with signs of trauma.

According to Admar de Chabannes, just before his death in 932 or 933 Rollo (founder and first ruler of the Viking

principality of Normandy) practised human sacrifices to appease the pagan gods, and at the same time made gifts to

the churches in Normandy.

[18]

Adam von Bremen recorded human sacrifices to Odin in 11th-century Sweden, at the Temple at Uppsala, a tradition

which is confirmed by Gesta Danorum and the Norse sagas. According to the Ynglinga saga, king Domalde was

sacrificed there in the hope of bringing greater future harvests and the total domination of all future wars. The same

saga also relates that Domalde's descendant king Aun sacrificed nine of his own sons to Odin in exchange for longer

life, until the Swedes stopped him from sacrificing his last son, Egil.

Heidrek in the Hervarar saga agrees to the sacrifice of his son in exchange for the command over a fourth of the men

of Reidgotaland. With these, he seizes the entire kingdom and prevents the sacrifice of his son, dedicating those

fallen in his rebellion to Odin instead.

Slavic peoples

Main article: Slavic paganism

Sixth century Byzantine emperor Mauricius's Strategikon wrote of the Slavs:

They don't hold their prisoners indefinitely, like other people, but, limiting their time as prisoners, offer them a choice: either to ransom their

way back to home or to stay where they are, as free man and friends.

In the 10th century, Persian explorer Ahmad ibn Rustah described funerary rights for the Rus' (Scandinavian Viking

traders in northeastern Europe) including the sacrifice of a young female slave. Leo the Deacon describes prisoner

sacrifice by the Rus' led by Sviatoslav during the Russo-Byzantine War "in accordance with their ancestral custom."

According to the 12th-century Russian Primary Chronicle, prisoners of war were sacrificed to the supreme Slavic

deity Perun. Sacrifices to pagan gods, along with paganism itself, were banned after the Baptism of Rus by Prince

Vladimir I in the 980s.

[19]

Archeological findings indicate that the practice may have been widespread, at least among slaves, judging from

mass graves containing the cremated fragments of a number of different people.

China

The ancient Chinese are known to have made sacrifices of young men and women to river deities, and to have buried

slaves alive with their owners upon death as part of a funeral service. This was especially prevalent during the Shang

and Zhou Dynasties. During the Warring States period, Ximen Bao of Wei demonstrated to the villagers that

sacrifice to river deities was actually a ploy by crooked priests to pocket money. In Chinese lore, Ximen Bao is

regarded as a folk hero who pointed out the absurdity of human sacrifice.

The sacrifice of a high-ranking male's slaves, concubines or servants upon his death (called Xun Zang or

Sheng Xun ) was a more common form. The stated purpose was to provide companionship for the dead in the

afterlife. In earlier times the victims were either killed or buried alive, while later they were usually forced to commit

suicide.

Funeral human sacrifice was widely practiced in the ancient Chinese state of Qin. According to the Records of the

Grand Historian by Han Dynasty historian Sima Qian, the practice was started by Duke Wu, the tenth ruler of Qin,

who had 66 people buried with him in 678 BC. The fourteenth ruler Duke Mu had 177 people buried with him in 621

BC, including three senior government officials. Afterwards the people of Qin wrote the famous poem Yellow Bird

Human sacrifice

9

to condemn this barbaric practice, later compiled in the Confucian Classic of Poetry.

[20]

The tomb of the eighteenth

ruler Duke Jing of Qin, who died in 537 BC, has been excavated. More than 180 coffins containing the remains of

186 victims were found in the tomb. The practice would continue for nearly three centuries until Duke Xian of Qin

abolished it in 384 BC. Modern historian Ma Feibai considers the significance of Duke Xian's abolition of human

sacrifice to Chinese history comparable to that of Abraham Lincoln's abolition of slavery to American history.

After the abolition by Duke Xian, funeral human sacrifice became relatively rare throughout the central parts of

China. However, the Hongwu Emperor of the Ming Dynasty revived it in 1395 when his second son died and two of

the prince's concubines were sacrificed. In 1464, the Zhengtong Emperor in his will forbade the practice for Ming

emperors and princes.

Human sacrifice was also practised by the Manchus. Following Nurhaci's death, his wife, Lady Abahai, and his two

lesser consorts committed suicide. During the Qing Dynasty, sacrifice of slaves was banned by the Kangxi Emperor

in 1673.

Tibet

Human sacrifice, including cannibalism, was thought to be practiced in Tibet prior to the arrival of Buddhism in the

7th century.

[21]

The prevalence of human sacrifice in medieval Buddhist Tibet is less clear. The Lamas, as professing Buddhists,

could not condone blood sacrifices, and they replaced the human victims with effigies made from dough. This

replacement of human victims with effigies is attributed to Padmasambhava, a Tibetan saint of the mid-8th century,

in Tibetan tradition.

Nevertheless, there is some evidence that outside of lamaism, there were practices of tantric human sacrifice which

survived throughout the medieval period, and possibly into modern times. The 15th-century Blue Annals, a seminal

document of Tibetan Buddhism, reports upon how in 13th Century Tibet the so-called "18 robber-monks"

slaughtered men and women for their corrupt tantric ceremonies.

[22]

Such practices of human sacrifice as there was

in medieval Tibet was mostly replaced by animal sacrifice, or the self-infliction of wounds in religious ritual, by the

20th century

[citation needed]

. A systematic survey of evidence for human sacrifice in 20th-century Tibet turns up three

instances:

1. Charles Alfred Bell reports the finding of the remains of an eight-year-old boy and a girl of the same age in a

stupa on the Bhutan-Tibet border, apparently ritually killed.

[23]

2. American anthropologist Robert Ekvall in the 1950s reported some instances of human sacrifice in remote areas

of the Himalayas.

[24]

Based on this evidence, Grunfeld (1996) concludes that it cannot be ruled out that isolated instances of human

sacrifice did survive in remote areas of Tibet until the mid-20th century, but they must have been rare enough to

have left no more traces than the evidence cited above.

[25]

Human sacrifice

10

India

Fierce goddesses like Chamunda are recorded to

have been offered human sacrifice.

The earliest evidence for human sacrifice in the Indian subcontinent

dates back to the Bronze Age Indus Valley Civilization. An Indus seal

from Harappa depicts the upside-down nude female figure with legs

outspread and a plant issuing from the womb. The reverse side of the

seal depicts a man holding a sickle and a woman seated on the ground

in a posture of prayer. Many scholars interpret this scene as a human

sacrifice in honor of the Mother-Goddess.

Regarding possible Vedic mention of human sacrifice, the prevailing

19th-century view, associated above all with Henry Colebrooke, was

that human sacrifice had little scriptural warrant, and did not actually

take place. Those verses which referred to purushamedha were meant

to be read symbolically or as a "priestly fantasy". However,

Rajendralal Mitra published a defence of the thesis that human

sacrifice, as had been practised in Bengal, was a continuation of

traditions dating back to Vedic periods. Hermann Oldenberg held to

Colebrooke's view; but Jan Gonda underlined its disputed status.

Human and animal sacrifice became less common during the

post-Vedic period, as ahimsa (non-violence) became part of

mainstream religious thought. This may correspond to the impact of

Sramanic religions such as Buddhism and Jainism. The Chandogya Upanishad (3.17.4) includes ahimsa in its list of

virtues.

It was agreed even by Colebrooke, however, that by the Puranic periodat least at the time of the writing of the

Kalika-Purana, human sacrifice was accepted. The Kalika Purana was composed in Northeast India in the 11th

century. The text states that blood sacrifice is only permitted when the country is in danger and war is expected.

According to the text, the performer of a sacrifice will obtain victory over his enemies. In the medieval period, it

became increasingly common. In the 7th century, Banabhatta, in a description of the dedication of a temple of

Chandika, describes a series of human sacrifices; similarly, in the 9th century, Haribhadra describes the sacrifices to

Chandika in Odisha. The town of Kuknur in North Karnataka there exists an ancient Kali temple, built around the

8-9th century AD, which has a history of human sacrifices.

Human sacrifices were carried out in connection with the worship of Shakti until approximately the early modern

period, and in Bengal perhaps as late as the early 19th century. Although not accepted by larger section of Hindu

culture, certain tantric cults performed human sacrifice until around the same time, both actual and symbolic; it was

a highly ritualised act, and on occasion took many months to complete.

The Khonds, an aboriginal tribe of India, inhabiting the tributary states of Odisha and Andhra Pradesh, became

notorious, on the British occupation of their district about 1835, from the prevalence and cruelty of the human

sacrifices they practised.

[26]

Human sacrifice

11

Pacific

James Cook witnessing human sacrifice in Tahiti

c. 1773

In Ancient Hawaii, a luakini temple, or luakini heiau, was a Native

Hawaiian sacred place where human and animal blood sacrifices were

offered. Kauwa, the outcast or slave class, were often used as human

sacrifices at the luakini heiau. They are believed to have been war

captives, or the descendents of war captives. They were not the only

sacrifices; law-breakers of all castes or defeated political opponents

were also acceptable as victims.

The people of Fiji practised widow-strangling. When Fijians adopted

Christianity, widow-strangling was abandoned.

[27]

Pre-Columbian Americas

See also: Child sacrifice in pre-Columbian cultures

Altar for human sacrifice at Monte Alban

Some of the most famous forms of ancient human sacrifice were

performed by various Pre-Columbian civilizations in the Americas that

included the sacrifice of prisoners as well as voluntary sacrifice. Friar

Marcos de Niza (1539) writing of the "Chichimecas": that from time to

time "they of this valley cast lots whose luck (honour) it shall be to be

sacrificed, and they make him great cheer, on whom the lot falls, and

with great joy they crown him with flowers upon a bed prepared in the

said ditch all full of flowers and sweet herbs, on which they lay him

along, and lay great store of dry wood on both sides of him, and set it

on fire on either part, and so he dies" and "that the victim took great

pleasure" in being sacrificed.

[28]

North America

The Mixtec players of the Mesoamerican ballgame were sacrificed when the game was used to resolve a dispute

between cities. The rulers would play a game instead of going to battle. The losing ruler would be sacrificed. The

ruler "Eight Deer" was considered a great ball player and won several cities this way, was eventually sacrificed, as

he attempted to go beyond lineage-governing practices, and try create an empire.

Human sacrifice

12

Human sacrificial victim on a Maya

vessel, 600850 AD (Dallas

Museum of Art)

Maya

Main article: Human sacrifice in Maya culture

The Maya held the belief that cenotes or limestone sinkholes were portals to the

underworld and sacrificed human beings and tossed them down the cenote to

please the water god Chaac. The most notable example of this is the "Sacred

Cenote" at Chichn Itz where extensive excavations have recovered the remains

of 42 individuals, half of them under twenty years old.

Only in the Post-Classic era did this practice become as frequent as in central

Mexico.

[29]

In the Post-Classic period, the victims and the altar are represented

as daubed in a hue now known as Maya Blue, obtained from the ail plant and

the clay mineral palygorskite.

[30]

Aztec

Main article: Human sacrifice in Aztec culture

Aztec sacrifices, Codex Mendoza.

The Aztecs were particularly noted for practicing human sacrifice on a

large scale; an offering to Huitzilopochtli would be made to restore the

blood he lost, as the sun was engaged in a daily battle. Human

sacrifices would prevent the end of the world that could happen on

each cycle of 52 years. In the 1487 re-consecration of the Great

Pyramid of Tenochtitlan some estimate that 80,400 prisoners were

sacrificed though numbers are difficult to quantify as all obtainable

Aztec texts were destroyed by Christian missionaries during the period

15281548.

[31]

According to Ross Hassig, author of Aztec Warfare, "between 10,000

and 80,400 people" were sacrificed in the ceremony. The old reports of

numbers sacrificed for special feasts have been described as

"unbelievably high" by some authors and that on cautious reckoning,

based on reliable evidence, the numbers would have been in the

hundreds for yearly feasts in Tenochtitlan. The real number of sacrificed victims during the 1487 consecration is

unknown.

Aztec burial of a sacrificed child at Tlatelolco.

Michael Harner, in his 1997 article The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice,

estimates the number of persons sacrificed in central Mexico in the

15th century as high as 250,000 per year. Fernando de Alva Corts

Ixtlilxochitl, a Mexica descendant and the author of Codex Ixtlilxochitl,

claimed that one in five children of the Mexica subjects was killed

annually. Victor Davis Hanson argues that an estimate by Carlos

Zumrraga of 20,000 per annum is more plausible. Other scholars

believe that, since the Aztecs always tried to intimidate their enemies,

it is more likely that they could have inflated the number as a

propaganda tool.

[32]

Human sacrifice

13

Tlaloc would require weeping boys in the first months of the Aztec calendar to be ritually murdered.

Sacrifices to Xipe Totec were bound to a post and shot full of arrows. The dead victim would be skinned and a priest

would use the skin. Earth mother Teteoinnan required flayed female victims.

US / Canada

Mound 72 mass sacrifice of 53 young women

The funeral procession of Tattooed Serpent in

1725, with retainers waiting to be sacrificed

The peoples of the Southeastern United States known as the

Mississippian culture (800 to 1600 CE) practiced human sacrifice, as

some artifacts have been interpreted as depicting such acts. Mound 72

at Cahokia (the largest Mississippian site), located near modern St.

Louis, Missouri, was found to have numerous pits filled with mass

burials thought to have been retainer sacrifices. One of several similar

pit burials had the remains of 53 young women who had been strangled

and neatly arranged in two layers. Another pit held 39 men, women

and children who showed signs of dying a violent death before being

unceremoniously dumped into the pit. Several examples showed signs

of not having been fully dead when buried and had tried to claw their

way to the surface. On top of these people another group had been

neatly arranged on litters made of cedar poles and cane matting.

Another group of four individuals found in the mound were interred on

a low platform, with their arms interlocked. They had had their heads

and hands removed. The most spectacular burial at the mound is the

"Birdman burial". This was the burial of a tall man in his 40s, now

thought to have been an important early Cahokian ruler. He was buried

on an elevated platform covered by a bed of more than 20,000

marine-shell disc beads arranged in the shape of a falcon, with the

bird's head appearing beneath and beside the man's head, and its wings

and tail beneath his arms and legs. Below the birdman was another

man, buried facing downward. Surrounding the birdman were several

other retainers and groups of elaborate grave goods.

A ritual sacrifice of retainers and commoners upon the death of an elite

personage is also attested in the historical record among the last

remaining fully Mississippian culture, the Natchez. Upon the death of

"Tattooed Serpent" in 1725, the war chief and younger brother of the

"Great Sun" or Chief of the Natchez; two of his wives, one of his

sisters (nicknamed La Glorieuse by the French), his first warrior, his

doctor, his head servant and the servant's wife, his nurse, and a

craftsman of war clubs all chose to die and be interred with him, as

well as several old women and an infant who was strangled by his parents. Great honor was associated with such a

sacrifice, and their kin was held in high esteem. After a funeral procession with the chiefs body carried on a litter

made of cane matting and cedar poles ended at the temple (which was located on top of a low platform mound); the

retainers with their faces painted red and drugged with large doses of nicotine, were ritually strangled. Tattooed

Serpent was then buried in a trench inside the temple floor and the retainers were buried in other locations atop the

mound surrounding the temple. After a few months time the bodies were dis-interred and their defleshed bones were

stored as bundle burials in the temple.

Human sacrifice

14

The Pawnee practiced an annual Morning Star Ceremony, which included the sacrifice of a young girl. Though the

ritual continued, the sacrifice was discontinued in the 19th century.

[33]

The Iroquois are said to have occasionally

sent a maiden to the Great Spirit.

The torture of war captives by the tribes of the Eastern Woodlands cultural region also seems to have had sacrificial

motivations. See Captives in American Indian Wars

South America

Llullaillaco mummies, Inca human sacrifice, Salta

province (Argentina).

The Incas practiced human sacrifice, especially at great festivals or

royal funerals where retainers died to accompany the dead into the

next life.

[34]

The Moche of Northern Peru sacrificed teenagers en

masse, as archaeologist Steve Bourget found when he uncovered

the bones of 42 male adolescents in 1995.

The study of the images seen in Moche art has enabled researchers

to reconstruct the culture's most important ceremonial sequence,

which began with ritual combat and culminated in the sacrifice of

those defeated in battle. Dressed in fine clothes and adornments,

armed warriors faced each other in ritual combat. In this

hand-to-hand encounter the aim was to remove the opponent's

headdress rather than kill him. The object of the combat was the

provision of victims for sacrifice. The vanquished were stripped

and bound, after which they were led in procession to the place of sacrifice. The captives are portrayed as strong and

sexually potent. In the temple, the priests and priestesses would prepare the victims for sacrifice. The sacrificial

methods employed varied, but at least one of the victims would be bled to death. His blood was offered to the

principal deities in order to please and placate them.

The Inca of Peru also made human sacrifices. As many as 4,000 servants, court officials, favorites, and concubines

were killed upon the death of the Inca Huayna Capac in 1527, for example.

[35]

A number of mummies of sacrificed

children have been recovered in the Inca regions of South America, an ancient practice known as capacocha. The

Incas performed child sacrifices during or after important events, such as the death of the Sapa Inca (emperor) or

during a famine.

West Africa

Victims for sacrifice - from The history of

Dahomy, an inland Kingdom of Africa, 1793

Human sacrifice was common in West African states up to and during

the 19th century. The Annual customs of Dahomey was the most

notorious example, but sacrifices were carried out all along the West

African coast and further inland. Sacrifices were particularly common

after the death of a King or Queen, and there are many recorded cases

of hundreds or even thousands of slaves being sacrificed at such

events. Sacrifices were particularly common in Dahomey, in the Benin

Empire, in what is now Ghana, and in the small independent states in

what is now southern Nigeria. According to R. J. Rummel, "Just

consider the Grand Custom in Dahomey: When a ruler died, hundreds,

sometimes even thousands, of prisoners would be slain. In one of these

ceremonies in 1727, as many as 4,000 were reported killed. In addition,

Dahomey had an Annual Custom during which 500 prisoners were

sacrificed."

[36]

Human sacrifice

15

In the Asante region of modern day Ghana, human sacrifice was often combined with capital punishment.

[37]

In the northern parts of West Africa, human sacrifice had become rare early as Islam became more established in

these areas such as the Hausa States. Human sacrifice was officially banned in the remainder of West African states

only by coercion, or in some cases annexation, by either the British or French. An important step was the British

coercing the powerful Egbo secret society to oppose human sacrifice in 1850. This society was powerful in a large

number of states in what is now south-eastern Nigeria. Nonetheless, human sacrifice continued, normally in secret,

until West Africa came under firm colonial control.

The Leopard men were a West African secret society active into mid-1900s that practised cannibalism. In theory, the

ritual cannibalism would strengthen both members of the society as well as their entire tribe. In Tanganyika, the Lion

men committed an estimated 200 murders in a single three-month period.

[38]

Prohibition in major religions

Judaism

Current religious thinking views the Akedah as central to the replacement of human sacrifice; while some Talmudic

scholars assert the replacement was the sacrifice of animals at the Templeusing Exodus 13:212f; 22:28f; 34:19f;

Numeri 3:1ff; 18:15; Deuteronomy 15:19others view that as superseded by the symbolic pars-pro-toto sacrifice of

circumcision. Leviticus 20:2 and Deuteronomy 18:10 specifically outlaw the giving of children to Moloch, making it

punishable by stoning; the Tanakh subsequently denounces human sacrifice as barbaric customs of Baal worshippers

(e.g. Psalms 106:37ff).

An angel interrupts the sacrifice of Isaac by

Abraham, with the animal replacement in the

background (The Offering of Abraham, Genesis

22:1-13, workshop of Rembrandt, 1636)

Judges chapter 11 contains a story in which a Judge named Jephthah

makes a vow to God to sacrifice the first thing that comes out of the

door of his house in exchange for God's help with a military battle

against the Ammonites. Much to his dismay, his only daughter greeted

him upon his triumphant return. Judges 11:39 states that Jephthah kept

his vow. According to the commentators of the rabbinic Jewish

tradition, Jepthah's daughter was not sacrificed, but was forbidden to

marry and remained a spinster her entire life, fulfilling the vow that she

would be devoted to the Lord. The 1st-century CE Jewish historian

Flavius Josephus, however, understood this to mean that Jephthah

burned his daughter on Yahweh's altar, whilst pseudo-Philo, late first

century CE, wrote that Jephthah offered his daughter as a burnt

offering because he could find no sage in Israel who would cancel his

vow.

[citation needed]

Christianity

In Christianity, the belief developed that the story of Isaac's binding

was foreshadowing for the sacrifice of Jesus, whose sacrifice and

resurrection allowed the sins of mankind to be washed away. There is a

tradition that the site of the binding of Isaac, Moriah, was also the city

of Jesus's future crucifixion.

[39]

The beliefs of most Christian denominations hinge upon the substitutionary

atonement of the sacrifice of Jesus, which is necessary for salvation in the afterlife. Each individual person must

participate in, and/or receive the benefits of, this sacrifice for the atonement of their sins. Early Christian sources

explicitly described this event as a sacrificial offering, with Jesus in the role of both priest and victim, although

starting with the Enlightenment, some writers, such as John Locke, have disputed the model of Jesus' death as a

Human sacrifice

16

propitiatory sacrifice.

[40]

Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Christians believe that this sacrifice is made present in the sacrament of the

Eucharist. In this tradition, bread and wine, offered in a liturgical ritual, transforms into the "Real Presence," (the

literal Body and Blood of Jesus Christ). Receiving the Eucharist is a central part of the religious life of Catholic and

Orthodox Christians. Most Protestant traditions do not share the belief in the Real Presence but otherwise are varied,

for example, they may believe that in the bread and wine, Christ is present only spiritually, not in the sense of a

change in substance (Methodism) or that the bread and wine of communion are a merely symbolic reminder

(Baptist). Although early Christians in the Roman Empire were accused of being cannibals,

[41]

practices such as

human sacrifice were abhorrent to them.

[42]

Islam

The Qur'an strongly condemns human sacrifice, as a "grave error and sinful act"

[43]

and an "ignorant, foolish act of

those that have gone astray."

[44]

Eastern religions

Main article: Ahimsa

Many traditions of Eastern religions including Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism embrace the doctrine of ahimsa

(non-violence) which imposes vegetarianism and outlaws animal as well as human sacrifice.

In the case of Buddhism, both bhikkhus (monks) and bhikkhunis (nuns) were forbidden to take life in any form as

part of the monastic code, while non-violence was promoted among laity through encouragement of the Five

Precepts. Across the Buddhist world both meat and alcohol are strongly discouraged as offerings to a Buddhist altar,

with the former being synonymous with sacrifice, and the latter a violation of the Five Precepts.

In Hinduism, the principle of ahimsa appears in Vedas,

[45]

Upnishad.

[46]

In Manu Smrti the same text, however, also

exempts religious sacrifice from the notion of "violence" since the victim of the sacrifice was taken to benefit from

the act as it would be reborn in a higher position.

[47]

In the 19th and 20th centuries, prominent figures of Indian spirituality such as Swami Vivekananda,

[48]

Ramana

Maharshi, Swami Sivananda and A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami

[49]

emphasised the importance of ahimsa.

Allegations of human sacrifice

See also: Blood libel

Groups that have had such accusations leveled against them include blood libel against the Jews by Apion in the 30s

CE, Christians in the Roman empire later allegations of a Jewish conspiracy and the witch hunts of the 16th and 17th

centuries. In the 20th century, blood libel accusations re-emerged as part of the satanic ritual abuse moral panic.

The People's Republic of China as well as Chinese nationalists in the Republic of China in their effort to discredit

Tibetan lamaism make frequent and emphatic reference to the historical human sacrifice in Tibet, portraying the

1950 People's Liberation Army invasion of Tibet as an act of humanitarian intervention. According to Chinese

sources, in the year 1948, 21 individuals were murdered by state sacrificial priests from Lhasa as part of a ritual of

enemy destruction, because their organs were required as magical ingredients.

[50]

The Tibetan Revolutions Museum

established by the Chinese in Lhasa has numerous morbid ritual objects on display to illustrate these claims.

[51]

In

Taiwan, Li Ao in his TV talk show in 2006 claimed that the Dalai Lama had commanded human sacrifices, asking

his followers to "tear out human skin" for "some religious ceremony". Most of the human remains that the Chinese

exhibit as gruesome evidence of Tibetan human sacrifice are in fact body parts of people who died of natural causes

which were collected after sky burial and preserved as relics.

Human sacrifice

17

Contemporary human sacrifice

Asia

Bangladesh

In March, 2010, a 26-year-old labourer was killed by fellow workers on the orders of the owners after a fortune teller

suggested that a human sacrifice would yield highly-prized red bricks.

[52]

India

Human sacrifice is illegal in India. But a few cases do occur in remote and underdeveloped regions of the country,

where modernity has not penetrated well and tribal/semi-tribal groups adhere to cultural practices as they did over

the course of millennia. According to the Hindustan Times, there was an incident of human sacrifice in western Uttar

Pradesh in 2003. Similarly, police in Khurja reported "dozens of sacrifices" in the period of half a year in 2006, by

followers of Kali, the goddess of power.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Further information: Medicine murder

Human sacrifice, in the context of religious ritual, still occurs in other traditional religions, for example in muti

killings in Eastern Africa and West African Vodun. When the purpose of the practice is to procure wealth for the one

who commissions the act, a human sacrifice is called a Money ritual. Human sacrifice is no longer officially

condoned in any country, and such cases are regarded as murder.

In January, 2008, Milton Blahyi of Liberia confessed being part of human sacrifices which "included the killing of

an innocent child and plucking out the heart, which was divided into pieces for us to eat." He fought against Charles

Taylor's militia.

Europe

United Kingdom

On June 2005, a report by BBC revealed that boys from Africa were being trafficked to UK for human sacrifice. It

noted that children were beaten and murdered after being labelled as witches by pastors.

Chile

A 1989 book by investigative journalist Patrick Tierney documents a modern ritual human sacrifice during the

devastating earthquake and tsunami of 1960 by a Machi of the Mapuche in the Lago Budi community.

[53]

The victim, 5-year-old Jos Luis Painecur, had his arms and legs removed by Juan Pan and Juan Jos Painecur (the

victim's grandfather), and was stuck into the sand of the beach like a stake. The waters of the Pacific Ocean then

carried the body out to sea. The sacrifice was rumoured to be at the behest of local machi, Juana Namuncur Aen.

The two men were charged with the crime and confessed, but later recanted. They were released after two years. A

judge ruled that those involved in these events had "acted without free will, driven by an irresistible natural force of

ancestral tradition."

The story is also mentioned in a Time magazine article from that year, although with much less detail.

Human sacrifice

18

Ritual murder

Ritual killings perpetrated by individuals or small groups within a society that denounces them as simple murder are

difficult to classify as either "human sacrifice" or mere pathological homicide because they lack the societal

integration of sacrifice proper.

The instances closest to "ritual killing" in the criminal history of modern society would be pathological serial killers

such as the Zodiac Killer, and mass suicides with doomsday cult background, such as the Peoples Temple,

Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God, Order of the Solar Temple or Heaven's Gate

incidents.Wikipedia:Avoid weasel words Other examples include the "Matamoros killings" attributed to Mexican

cult leader Adolfo Constanzo and the "Superior Universal Alignment" killings in 1990s Brazil.

[54]

In fiction

Human sacrifice has a history as a topic in literature, opera, video games, and cinema. A recurrent theme in the

Classics, it returns to prominence in European imagination with the Spanish accounts of the Aztec rituals. Derek

Hughes in Culture and Sacrifice traces the topic's iterations through the works of Shakespeare, Dryden and Voltaire,

and its central position in the operatic tradition from Mozart to Wagner and into 20th century works such as those of

D.H. Lawrence.

[55][56]

"The Lottery" is a 1948 short story that caused controversy in the United States.

Robin Hardy's 1973 cult film The Wicker Man explores the subject of human sacrifice.

In Rosemary Sutcliff's 1977 historical novel Sun Horse, Moon Horse, the main character accepts a duty as a

sacrificial king and lays down his life for the redemption of his people, while inaugurating the creation of the

Uffington White Horse.

Most of the plot of The Beatles' film Help! deals (in a humorous way) with a group that practises human sacrifice

trying to kill Ringo Starr because he is wearing the sacrificial ring.

In Tintin: Prisoners of the Sun the Inca leader comes close to sacrificing Tintin, Captain Haddock, and Professor

Calculus on a pyre to be set alight with parabolic mirrors. This was for Calculus having committed sacrilege for

wearing the bracelet of Rascar Capac.

In the 1984 film Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, high priest Mola Ram sacrifices men by magically

removing their heart with one hand and lowering them in boiling lava. One sacrifice is shown, in which the

victim's amputated heart spontaneously combusts when the victim hits the lava. In Mel Gibson's 2006 film

Apocalypto, human sacrifice is done to appease the gods.

In the Dan Brown novel The Lost Symbol, the book's main antagonist Mal'akh, prepares himself for the human

sacrifice throughout the story, believing that it is his great destiny to lead the forces of evil.

In the two fantasy series the Belgariad and the Malloreon by David Eddings, human sacrifice of a type similar to

that of the Aztecs is practiced by men of the Angarak race in devotion to their god Torak.

In The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, the main antagonists order the player character to ritually kill a member of the

benevolent Faith Of The Nine during the story arc in which the player is infiltrating their organization. If refused,

they attack the player. If the player does this, the villains will become convinced the player is on their side, and

the infiltration goes more smoothly for this assumption.

In The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, human sacrifice is a recurring element in several side quests involving the

infamous Daedric Princes. The most infamous of these is a quest given by the Daedric Prince Boethiah where the

Dragonborn must sacrifice one of his or her followers in order to progress further into the quest and the Daedric

Prince Molag Bal requires the player to sacrifice a priest of Boethiah by murdering him with a rusted mace once

he is caught in one of Molag Bal's traps.

In the 2012 film The Cabin in the Woods, human sacrifice plays a significant role in the plot.

Human sacrifice

19

References

Footnotes

[1] http:/ / en. wikipedia. org/ w/ index. php?title=Template:Homicide& action=edit

[2] "For example, "The Building of Skadar" (Vuk II, 25) is based on the motif of a blood sacrifice being required to make a building stand."

(Felix J. Oinas: Heroic Epic and Saga: An Introduction to the World's Great Folk Epics; Indiana University Press, 1978, ISBN

9780253327383, p. 262.)

[3] Alan Dundes: The Walled-Up Wife: A Casebook; Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1996, ISBN 9780299150730, p. 146

[4] Hassig, Ross (2003). "El sacrificio y las guerras floridas". Arqueologa mexicana, p. 4651.

[5] "Why King Mesha of Moab Sacrificed His Oldest Son", Baruch Margalit, Biblical Archaeology Review, Nov/Dec 1986 (http:/ / members.

bib-arch.org/ nph-proxy.pl/ 000000A/ http:/ / www.basarchive. org/ bswbSearch. asp=3fPubID=3dBSBA& Volume=3d12& Issue=3d6&

ArticleID=3d5& UserID=3d0& )

[6] Radak, Book of Judges 11:39; Metzudas Dovid ibid

[7] " Relics of Carthage Show Brutality Amid the Good Life (http:/ / www. nytimes. com/ 1987/ 09/ 01/ science/

relics-of-carthage-show-brutality-amid-the-good-life.html?pagewanted=all)". The New York Times. September 1, 1987.

[8] Fantar, MHamed Hassine. Archaeology Odyssey Nov/Dec 2000, pp. 2831

[9] Herodotus VIII, 54 (http:/ / www. perseus. tufts.edu/ cgi-bin/ ptext?doc=Perseus:text:1999. 01. 0126& layout=& loc=6. 113)

[10] [10] Livy 22.55-57

[11] Livy, 22.57.4; Plutarch, Roman Questions, 83 and Marcellus, 3; Mary Beard, J.A. North, and S.R.F. Price, Religions of Rome: A History

(Cambridge University Press, 1998), vol. 1, p. 81.

[12] Pliny, Natural History 30.3.12

[13] Catharine Edwards, Death in Ancient Rome (Yale University Press, 2007), pp. 5960; David S. Potter, "Entertainers in the Roman Empire,"

in Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire (University of Michigan Press, 1999), p. 305; Tertullian, De spectaculis 12.

[14] " Druids Committed Human Sacrifice, Cannibalism? (http:/ / news. nationalgeographic. com/ news/ 2009/ 03/

090320-druids-sacrifice-cannibalism_2.html)". National Geographic.

[15] French archaeologist Jean-Louis Brunaux has written extensively on human sacrifice and the sanctuaries of Belgic Gaul. See "Gallic Blood

Rites," Archaeology 54 (March/April 2001), 5457; Les sanctuaires celtiques et leurs rapports avec le monde mediterranean, Actes de

colloque de St-Riquier (8 au 11 novembre 1990) organiss par la Direction des Antiquits de Picardie et l'UMR 126 du CNRS (Paris: ditions

Errance, 1991); "La mort du guerrier celte. Essai d'histoire des mentalits," in Rites et espaces en pays celte et mditerranen. tude compare

partir du sanctuaire d'Acy-Romance (Ardennes, France) (cole franaise de Rome, 2000).

[16] Buchholz, Peter (1993). "Pagan Scandinavian Religion" in Pulsiano, P (Ed.) Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia". New York:

Routledge. pp. 521525.

[17] Simek, Rudolf (2003). Religion und Mythologie der Germanen. Wissenshaftliche Buchgesellschaft: Darmstadt. pp. 5864. ISBN

3-8062-1821-8.

[18] Franois Neveux, A brief history of the Normans: the conquests that changed the face of Europe, Robinson, 2008

[19] Lavrentevskaia Letopis, also called the Povest Vremennykh Let, in Polnoe Sobranie Russkikh Letopisei (PSRL), vol. 1, col. 102.

[20] Yellow Bird, Classic of Poetry (in Chinese).

[21] e.g. L. Austine Waddell, Tibetan Buddhism: With Its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in Its Relation to Indian Buddhism, 1895,

p. 516: "Human sacrifice seems undoubtedly to have been regularly practised in Tibet up till the dawn there of Buddhism in the seventh

century."

[22] [22] Blue Annals, ed. 1995, p.697.

[23] [23] Bell, 1927, p.80.

[24] Ekvall, 1964, pp.165166, 169, 172.

[25] A. Tom Grunfeld, The making of modern Tibet, 1996, ISBN 978-1-56324-714-9, p. 29.

[26] Khonds, or Kandhs (http:/ / encyclopedia. jrank.org/ KHA_KRI/ KHONDS_or_KANDHS. html), Encyclopdia Britannica

[27] " Odd faiths in Fiji isles (http:/ / query. nytimes.com/ gst/ abstract. html?res=FA0F12FA345F10738DDDA10894DA405B8185F0D3)". The

New York Times.

[28] Grace E. Murray, Ancient Rites and Ceremonies, p. 19, ISBN 1-85958-158-7

[29] " pre-Columbian civilizations (http:/ / www. britannica. com/ EBchecked/ topic/ 474227/ pre-Columbian-civilizations)". Encyclopdia

Britannica.

[30] [30] as cited in

[31] [31] George Holtker, "Studies in Comparative Religion", The Religions of Mexico and Peru, Vol. 1, CTS

[32] Duverger (op. cit), 17477

[33] Pawnee ritual (http:/ / dactyl.som. ohio-state. edu/ Densmore/ Pawnee/ pawnee01. html)

[34] [34] Woods, Michael, "Conquistadors", p. 114, BBC Worldwide, 2001, ISBN 0-563-55116-X

[35] Nigel Davies, Human Sacrifice (1981, p. 261262.).

[36] R. Rummel (1997)" Death by government (http:/ / books. google. com/ books?id=N1j1QdPMockC& pg=& dq& hl=en#v=onepage& q=&

f=false)". Transaction Publishers. p.63. ISBN 1-56000-927-6

Human sacrifice

20

[37] Clifford Williams (1988) The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 21, No. 3. (1988), pp.433441

[38] Murder by Lion (http:/ / www.time.com/ time/ magazine/ article/ 0,9171,867859,00. html), TIME

[39] [39] http://"Voices From the Children of Abraham", [www.newmantoronto.com/040311childrenofabraham2.htm ]

[40] According to Alister McGrath, early sources describing a sacrifice include the New Testament's Letter to the Hebrews and writings by

Augustine of Hippo and Athanasius of Alexandria. Later sources, besides Locke, include Thomas Chubb and Horace Bushnell.

[41] [41] Benko, Stephen, Pagan Rome and the Early Christians, p70, Indiana University Press, 1986, ISBN 0-253-20385-6

[42] [42] "The Britons", Christopher Allen Snyder, p. 52, Blackwell Publishing, 2003, ISBN 0-631-22260-X

[43] [43] surah 17 ayah 31

[44] [44] surah 6 ayah 140

[45] By Walli, Koshelya: The Conception of Ahimsa in Indian Thought, Varanasi 1974, p. 113-145.

[46] "Ahis: Non-violence in Indian Tradition", by Thtinen, p. 25;

[47] Manu Smriti 5.32; 5.3940; 5.42

[48] Religious Vegetarianism, ed. Kerry S. Walters and Lisa Portmess, Albany 2001, pp. 5052.

[49] Religious Vegetarianism p. 5660.

[50] [50] Grunfeld, 1996, p. 29.

[51] [51] Epstein, 1983, p.138

[52] Bangladeshi man beheaded by labourers to 'redden bricks' after fortune teller suggested sacrifice (http:/ / www. dailymail. co. uk/ news/

article-1259736/ Man-beheaded-redden-bricks.html), March 22, 2010

[53] The Highest Altar: Unveiling the Mystery of Human Sacrifice ISBN 978-0-14-013974-7

[54] [54] Todd Lewan, Satanic Cult Killings Spread Fear in Southern Brazil, The Associated Press, 26 October 1992

[55] [55] Hughes (2007)

[56] http:/ / www.hero. ac.uk/ uk/ inside_he/ archives/ 2008/ sacred_horror_Feb. cfm

Books

David Carrasco, City of Sacrifice: The Aztec Empire and the Role of Violence in Civilization, Moughton Mifflin,

2000, ISBN 0-8070-4643-4

Inga Clendinnen, Aztecs: An Interpretation, Cambridge University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-521-48585-2

Clemency Coggins and Orrin C. Shane III Cenote of Sacrifices, ; 1984 The university of Texas Press; ISBN

0-292-71097-6

Ren Girard, Violence and the Sacred, translated by P. Gregory; Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979, ISBN

0-8264-7718-6

Ren Girard, I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, translated by James G. Williams; Orbis Books; 2001, ISBN

1-57075-319-9

Miranda Aldhouse-Green, Dying for the Gods,; Trafalgar Square; 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1940-4

Dennis D. Hughes, Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece 1991 Routledge ISBN 0-415-03483-3

Derek Hughes, Culture and Sacrifice: Ritual Death in Literature and Opera, 2007, Cambridge University Press,

ISBN 978-0-521-86733-7

Ronald Hutton, The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy, 1991, ISBN

0-631-18946-7

Larry Kahaner, Cults That Kill, ; Warner Books; 1994, ISBN 978-0-446-35637-4

Valerio Valeri, Kingship and Sacrifice: Ritual and Society in Ancient Hawaii, 1985, University of Chicago Press,

ISBN 0-226-84559-1

Adolf E. Jensen, Myth and Cult among Primitive Peoples, University of Chicago Press, 1963

Human sacrifice

21

Journal articles

Michael Winkelman, Aztec Human Sacrifice: Cross-Cultural Assessments of the Ecological Hypothesis,

Ethnology, Vol. 37, No. 3. (Summer, 1998), pp.285298.

R.H. Sales, Human Sacrifice in Biblical Thought, Journal of Bible and Religion, Vol. 25, No. 2. (Apr., 1957),

pp.112117.

Brian K. Smith; Wendy Doniger, Sacrifice and Substitution: Ritual Mystification and Mythical Demystification,

Numen, Vol. 36, Fasc. 2. (Dec., 1989), pp.189224.

Brian K. Smith, Capital Punishment and Human Sacrifice, Journal of the American Academy of Religion 2000

68(1):326.

Robin Law, Human Sacrifice in Pre-Colonial West Africa, African Affairs, Vol. 84, No. 334. (Jan., 1985),

pp.5387.

Th. P. van Baaren, Theoretical Speculations on Sacrifice, Numen, Vol. 11, Fasc. 1. (Jan., 1964), pp.112.

Heinsohn, Gunnar: The Rise of Blood Sacrifice and Priest Kingship in Mesopotamia: A Cosmic Decree? (http:/

/ www. kronia. com/ library/ journals/ sacrfice. txt) (also published in Religion, Vol. 22, 1992)

J. Rives, Human Sacrifice among Pagans and Christians, The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 85. (1995),

pp.6585.

Clifford Williams, Asante: Human Sacrifice or Capital Punishment? An Assessment of the Period 18071874,

The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 21, No. 3. (1988), pp.433441.

Sheehan, Jonathan, The Altars of the Idols: Religion, Sacrifice, and the Early Modern Polity, Journal of the

History of Ideas 67.4 (2006) 649674 ( "Project MUSE - Journal of the History of Ideas - The Altars of the Idols:

Religion, Sacrifice, and the Early Modern Polity" (http:/ / muse. jhu. edu/ journals/

journal_of_the_history_of_ideas/ v067/ 67. 4sheehan02. html). Muse.jhu.edu. Retrieved 2010-05-25.)

Harco Willems, Crime, Cult and Capital Punishment (Mo'alla Inscription 8), The Journal of Egyptian

Archaeology, Vol. 76, (1990), 2754.

External links

D.L. Ashliman's Human Sacrifice in Legends and Myths (http:/ / www. pitt. edu/ ~dash/ sacrifice. html)

Article Sources and Contributors

22

Article Sources and Contributors

Human sacrifice Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?oldid=607088986 Contributors: 77 trombones, 7h3 3L173, ADMH, Aaron Kauppi, Aaron Walden, AaronPaige, Addshore,

AdjustShift, AdultSwim, Alexoneill1469, Allycat, Altenmann, Amillar, Amity150, And solo said, Andries, AndyBoySouthPas, Angusmclellan, Antonio Lopez, Art LaPella, Arthena, Ashley Y,

Asperin, Attilios, Auntof6, Avraham, Awien, B, B00P, BCtl, BD2412, Babbage, Bachrach44, Battistoli, Bearcat, Beleg Tl, Ben Ben, Bensin, Bento00, Benzeman, Bgwhite, Bingo4it,

Bladesmulti, BlastOButter42, Blueshirts, Bnyup, Bobak, Boston, Brenont, Brian0918, Briangotts, Bryan Sellars, Bswarts, BuckRefvem, Budgie114, Bumhoolery, CJLL Wright, Calmer Waters,

Camw, Can't sleep, clown will eat me, CanisRufus, Cesar Tort, Ceyockey, Cgnk, Charles Matthews, Charles Ulysses Farley, Chris the speller, ChrisGualtieri, ChrisO, ChromaNebula, Clawed,

Cleared as filed, Clovis Sangrail, Clodhna-2, Cokoli, Cold ground, Coldbourne, Colonies Chris, ColorOfSuffering, CommonsDelinker, ComputerJA, Corpx, Courcelles, Creyes, Cuthbert Pullar,

Cynwolfe, D6, DGJM, DNewhall, DO'Neil, DadaNeem, Daicaregos, Dan Koehl, Danny, Dbachmann, DeadEyeArrow, Deadbeef, Deathawk, Demiurge1000, Deqon, Deville, Dgw,

Dharmabatteries, Discospinster, Dobie80, Dogyo, Dougweller, Dr magdy elmahdy, DrKC9N, Dreadstar, Dreamafter, Drmangnat, Drys, DuffsCalvin, Dumbo1, Dzied Bulbash, EamonnPKeane,

EastTN, Ecbloom, Edith Smitters, Editor2020, Edward Z. Yang, Egmontaz, Egyptzo, Eidimon, El C, Eliyak, Eliz81, Elizabeyth, Ellsworth, Elnon, Elockid, Emaha, Engwar, Epbr123, Esperant,

Eugene-elgato, Everyking, Excirial, Exodus21v20, Explicit, Fallenangei, Fayenatic london, Fbhenry, Feeeshboy, Ferkelparade, Feudonym, Florentino floro, Flyer22, Folantin, Foodman,

Fotoriety, Foxxygirltamara, Fratrep, Freeboson, Frikle, Futurix, Gaius Cornelius, Garret Beaumain, Gatemansgc, Gene Poole, Ghirlandajo, Ginkgo100, Glengordon01, Gogo Dodo,

GoldenMeadows, Goldfritha, Gproud, Grafen, Ground, Gtrmp, Gurch, Harisingh, Hede2000, Heironymous Rowe, Hghyux, Hillel, Hmmr-smokeing, Hno3, Hokie Tech, Hongooi, Hotblaster,

Husond, Ian.thomson, Ihcoyc, Imc, InformationalAnarchist, Infrogmation, Irbster1, Iridescent, Isolater, J04n, JD554, JLogan3o13, JaGa, Jabberwalkee, Jachin, Jack Merridew, JamesAM,

Jamesx12345, Janfrie1988, Jayjg, Jedi6, Jen6jen6, Jennifer1592, Jensketch, Jibbajabba, Jim1138, Jj137, Jmlk17, Jmm6f488, Jmrowland, Joe Cetina, JoeFriday, Joesonyx, John D. Croft, Johncoz,

Jojalozzo, Jonathan Grynspan, Jonathunder, Joyous!, Jpgordon, Jprg1966, Jsp722, KConWiki, KathrynLybarger, Katieh5584, Kbdank71, Keltica, Ken Gallager, Kevin Gorman, KevinOKeeffe,

Keysvolume, Khazar2, Kintetsubuffalo, Kizor, Kjkolb, Klilidiplomus, Kosher Fan, Kylu, LaMenta3, Lacrimosus, Laurips, Lazulilasher, Lds, Leafyplant, LeaveSleaves, Leflyman,

Lemonmelonsuperstar, Leon3289, Leontios, Lesgles, Lightmouse, LilHelpa, Lotje, Lugia2453, LukeTheSpook, Maclean25, Madman2001, Magnificascriptor, Malhonen, Malickfan86, Mamalujo,

MarcelB612, Marek69, Mark Arsten, Martinphi, Masssly, Materialscientist, Mattbr, Mattisse, Maunus, Mboverload, Medicineman84, MegX, Meishern, Meshach, Midnightblueowl, Mike Rosoft,

Mindworm, Mirv, MishaPan, Misterramune, Mkpumphrey, Modulatum, Mogism, Mostafa Saleh A. Mawla, Mr. Lefty, MrHen, Mukogodo, Munci, MusikAnimal, Nanahuatzin, Ncsmad,

Neurolysis, NeuronExMachina, Neverquick, Nh3nh4, Niceguyedc, Nicknack009, Nightscream, Nijgoykar, Nilmerg, Niri.M, Niten, Nixdorf, Nono64, Nuclearfusion567, Olehal09, Olybrius,

Omegafouad, Omegatron, Onceonthisisland, Oobopshark, Owain meurig, Ozomatli-Tepoztli, P0lyglut, PBC, PMLawrence, PanthBharti, Pattych, Paul Barlow, Pavel Vozenilek, PelleSmith,

Penelope D, Pereant antiburchius, Pevos, Ph0kin, Philip Trueman, Pigman, Piledhigheranddeeper, Pinethicket, Plommespiser, Pollinosisss, Pompi222, Populus, Porfyrios, Portillo, Poweron,

Pranathi, Pratikthakore, Prhartcom, Professorjohnas, Proxima Centauri, Pseudo-Richard, Qmwne235, R'n'B, RK, Randroide, RavShimon, Razimantv, Reach Out to the Truth, RedWolf,

Redtigerxyz, Reediewes, Relata refero, ResearchEditor, Rhdv, Rholton, Rhrad, Rich Farmbrough, Richard001, Richigi, Rjwilmsi, Rmhermen, Robert L, Robinson weijman, RodC, RookZERO,

RoyBoy, Rscottstewart, Rwalker, RyanCross, Rdacteur Tibet, Sageling, Sam Spade, SamuelTheGhost, Sannse, Sardanaphalus, Savh, Schuym1, Scutfargus, Scwlong, Seanqtx, Semitransgenic,

Sevilledade, Sgmbest12321, Shirulashem, Shiva321, Simon Burchell, Simon Peter Hughes, Sirius2044, Sj, Skinsmoke, Skizzik, Skysmith, Snakesteuben, Solvita, Sommers, Sonjaaa, Sonyray,

SpaceFalcon2001, Speedy la cucaracha, Spider Liker, Spike Wilbury, StAnselm, Stackofmuscles, Steinberger, Stephen G. Brown, Stevenmitchell, Stevertigo, Stifle, Stormie, Sun Creator,

Super48paul, Switchercat, TJFox, TKingslsgon, Taam, Tachbrook, Teammm, Tentinator, TexasAndroid, The Dark Peria, The Ogre, Theelf29, Thomas Paine1776, Tide rolls, Timrfrench61,

Tobby72, Tobetheman, Tobyc75, Tonyrex, Transfinite, Trasman, TriniMuoz, Triwbe, TrtaTrticTrtinir, TruthShallSetTheeFree, Tsiaojian lee, Tslocum, Twas Now, TyrocP, Ufwuct, Umat4,

Underlying lk, Uyvsdi, V9ngu9rd, Vanished user ewfisn2348tui2f8n2fio2utjfeoi210r39jf, Vardion, Varoon Arya, Video3323, Vivin, Vonharris, WANAX, WLU, WSaindon, Wasell, Wavelength,

Whateley23, Widr, Wiglaf, Wiki-uk, WikiEditor002, Wikiacc, Wikipelli, Wkp123, Woohookitty, Workersdreadnought, X15, XKV8R, Xanzzibar, Xenovatis, Xerographica, Xufanc, Yhasan,

Yilku1, Yllibill, YorkBW, Zacatecnik, Zanhe, Zello, Zerstuckelung, Zvezdara Forest, , , , 708 anonymous edits

Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors

File:Tovar Codex (folio 134).png Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Tovar_Codex_(folio_134).png License: Public Domain Contributors: El Comandante

File:Ashanti Yam Ceremony 1817.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Ashanti_Yam_Ceremony_1817.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: Thomas E. Bowdich

File:Arago 'Supplice Sandwich'.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Arago__'Supplice_Sandwich'.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: Nicolas Eustache

Maurin

File:Sacrifice Polyxena BM GR1897.7-27.2.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Sacrifice_Polyxena_BM_GR1897.7-27.2.jpg License: Creative Commons Attribution

2.5 Contributors: User:Jastrow

File:Sacrifici d'Ifignia (Empries).jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Sacrifici_d'Ifignia_(Empries).jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: Bestiasonica,

Eunostos, Jordiferrer, SeptemberWoman

File:WickerManIllustration.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:WickerManIllustration.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: Unknown Original uploader was

Midnightblueowl at en.wikipedia

File:Camunda5.JPG Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Camunda5.JPG License: Public Domain Contributors: Original uploader was Mohonu at en.wikipedia

File:James Cook, English navigator, witnessing human sacrifice in Taihiti (Otaheite) c. 1773.jpg Source:

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:James_Cook,_English_navigator,_witnessing_human_sacrifice_in_Taihiti_(Otaheite)_c._1773.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors:

unknown

File:Monte Albn-12-05oaxaca031.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Monte_Albn-12-05oaxaca031.jpg License: Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Contributors:

Bobak Ha'Eri

File:Maya vessel with sacrificial scene DMA 2005-26.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Maya_vessel_with_sacrificial_scene_DMA_2005-26.jpg License: Public

Domain Contributors: Photo: User:FA2010

File:Codex Magliabechiano (141 cropped).jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Codex_Magliabechiano_(141_cropped).jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: El

Comandante, Simon Peter Hughes, 1 anonymous edits

File:Kinderopfer 2.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Kinderopfer_2.jpg License: Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0,2.5,2.0,1.0 Contributors: Wolfgang

Sauber

File:Mound 72 sacrifice ceremony HRoe 2013.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Mound_72_sacrifice_ceremony_HRoe_2013.jpg License: Creative Commons

Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Contributors: User:Heironymous Rowe

File:Funeral procession of Serpent Pique du Pratz.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Funeral_procession_of_Serpent_Pique_du_Pratz.jpg License: Public Domain

Contributors: Felix Folio Secundus, Heironymous Rowe

File:Llullaillaco mummies in Salta city, Argentina.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Llullaillaco_mummies_in_Salta_city,_Argentina.jpg License: Creative

Commons Attribution 2.0 Contributors: Amytrael, FlickreviewR, 1 anonymous edits

File:Victims for sacrifice-1793.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Victims_for_sacrifice-1793.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: Archibad Dalzel