Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Q&A About Forests and Global Climate Change: Kenneth Green, D.Env

Загружено:

reasonorg0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

30 просмотров12 страницRPPI is a nonpartisan public policy think tank promoting choice, competition, and a dynamic market economy. RPPI seeks to change the way people think about issues, and promote policies that allow and encourage individuals and voluntary institutions to flourish. The foundation's independent monthly magazine of Free Minds and Free Markets covers politics, culture, and ideas from a dynamic libertarian perspective.

Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

bd1d627be34d9aa3f205f3840439f8cd

Авторское право

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документRPPI is a nonpartisan public policy think tank promoting choice, competition, and a dynamic market economy. RPPI seeks to change the way people think about issues, and promote policies that allow and encourage individuals and voluntary institutions to flourish. The foundation's independent monthly magazine of Free Minds and Free Markets covers politics, culture, and ideas from a dynamic libertarian perspective.

Авторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

30 просмотров12 страницQ&A About Forests and Global Climate Change: Kenneth Green, D.Env

Загружено:

reasonorgRPPI is a nonpartisan public policy think tank promoting choice, competition, and a dynamic market economy. RPPI seeks to change the way people think about issues, and promote policies that allow and encourage individuals and voluntary institutions to flourish. The foundation's independent monthly magazine of Free Minds and Free Markets covers politics, culture, and ideas from a dynamic libertarian perspective.

Авторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 12

September 2001

Q&A About Forests and

Global Climate Change

Kenneth Green, D.Env.

Director of the Environment, Health, and Safety Program

Reason Public Policy Institute

Reason Public Policy Institute

A division of the Los Angeles-based Reason Foundation, Reason

Public Policy Institute (RPPI) is a nonpartisan public policy

think tank promoting choice, competition, and a dynamic market

economy as the foundation for human dignity and progress. RPPI

produces rigorous, peer-reviewed research and directly engages the

policy process, seeking strategies that emphasize cooperation, flex-

ibility, local knowledge, and results. Through practical and innova-

tive approaches to complex problems, RPPI seeks to change the

way people think about issues, and promote policies that allow and

encourage individuals and voluntary institutions to flourish.

Reason Foundation

Reason Foundation is a national research and education organiza-

tion that explores and promotes the twin values of rationality and

freedom as the basic underpinnings of a good society. Since 1978,

the Los Angeles-based Foundation has provided practical pub-

lic-policy research, analysis, and commentary based upon prin-

ciples of individual liberty and responsibility, limited government,

and market competition. REASON, the Foundation’s independent

monthly magazine of Free Minds and Free Markets, covers politics,

culture, and ideas from a dynamic libertarian perspective.

Reason Foundation is a tax-exempt organization as defined under IRS

code 501(c)(3). Reason Foundation neither seeks nor accepts government

funding, and is supported by individual, foundation, and corporate contribu-

tions. Nothing appearing in this document is to be construed as necessarily

representing the views of Reason Foundation or its trustees, or as an attempt to

aid or hinder the passage of any bill before any legislative body.

Photos used in this publication are copyright © 1996, Photodisc, Inc.

Text copyright © 2001, Reason Foundation. All rights reserved.

2 Reason Public Policy Institute

What Can Be Done About the

Build-up of “Greenhouse Gases”

in the Atmosphere?

C oncerns over the potentially negative effects of prolonged

global warming have generated interest in restraining the

buildup of “greenhouse gases” in the atmosphere. Currently,

human-generated emissions of carbon dioxide and other green-

house gases total about 8.2 billion metric tons of carbon per year

(about 1.35 metric tons per capita per year). Global carbon dioxide

emissions contained about 8.2 billion metric tons of carbon in

2000 and, with “business as usual,” could reach 14.5 billion metric

tons in 2050.

Despite many remaining uncertainties in scientific under-

standing of climate change, most initiatives propose to slow or

stop the buildup of greenhouse gases by reducing fossil fuel use.

Such policy options are likely to have little positive impact on

climate, but could result in negative impacts on energy production,

national economies, and personal autonomy.

An alternate approach that is gaining more attention is

removing—“sequestering”—carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse

gas, from the atmosphere and storing it in a variety of ways in

forests and other large masses of plant life.

Forest sequestration offers a “win-win” approach to global

warming. Enhancing sequestration would slow any climate change

that might occur due to greenhouse gas emissions, while offering

immediate environmental benefits.

Q&A About Forests and Global Climate Change 3

What Role Do Forests Play in Carbon

Dioxide Sequestration?

T he concept of carbon removal, or sequestration, is scien-

tifically grounded. In its simplified form, sequestration is

based on the process of photosynthesis, whereby green plants

remove carbon dioxide (CO2 ) from the atmosphere and separate

the carbon atom from the oxygen atom. The tree or plant returns

the oxygen to the atmosphere but uses the carbon to build its own

structure in the form of roots, trunk, stems, and leaves. Thus, a

healthy forest can continue to grow and remove yet more carbon

dioxide from the atmosphere.

Trees, wood, and paper products are natural, renewable

resources that help reduce greenhouse gases by removing and stor-

ing carbon dioxide and providing carbon dioxide-neutral sources of

energy. They are part of a natural cycle that can help meet the

challenge of global climate change.

Based on evaluation of published studies, the potential

amounts of carbon emissions that can be stored in forests and

reduced through the use of the biomass fuel that is a natural by-

product of forest harvesting are as follows:

1. Improvements in Forest Management. This could

result in about 2 billion metric tons of carbon stored per year, at an

average cost around $4 per ton of carbon stored.

2. Use of Biomass Fuels. This could substitute for 2 billion

metric tons of annual fossil fuel emissions at a cost similar to the

replaced fossil fuels.

4 Reason Public Policy Institute

What Forest Management Techniques

Need to be Implemented?

T he life cycle of carbon is tied to forest management tech-

niques, as well as to the eventual disposition of forest prod-

ucts. The forest carbon cycle does not end when a forest is

harvested because, unlike in other manufacturing sectors, carbon

from forests is not immediately emitted. It is stored for long

periods of time in wood and paper products and can be used for

energy as a substitute for fossil fuels. The process can remain in

perpetual balance through tree planting.

There are three principal ways to sequester carbon in forests:

Maximizing carbon retention;

Increased tree-planting on agricultural land; and

Preventing deforestation.

1. Maximizing carbon retention. Advanced forest manage-

ment techniques-including forest thinning, “stand” improvement,

fire protection, competition control, nutrient application, and pest

management-can maintain and enhance the removal of carbon

dioxide from the atmosphere by improving forest growth. Over

the long haul, such practices can sequester and store more carbon

in forests, displace more non-renewable fossil fuel energy, and

store greater amounts of carbon in products than simple forest

preservation alone can.

According to the Department of Agriculture’s U.S. Forest Ser-

vice, managed forests in the U.S. remove approximately 310 million

metric tons of carbon, or 17 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emis-

sions, per year. This is equivalent to removing the carbon dioxide

emissions from 235 million automobiles on the road per year.

However, there is no guarantee that these benefits will be

maintained in the future. Mounting pressures on U.S. forestlands,

including suburban growth, threaten the continuous carbon seques-

tration loop by converting forests to other uses. The management

of forests for multiple environmental objectives will happen only

if forests are managed with sequestration—as well as habitat and

species preservation—as one of its specific goals.

Q&A About Forests and Global Climate Change 5

2. Increased Tree-planting on Agricultural Lands. In addi-

tion to increasing management and productivity of today’s forests,

more tree-planting on agricultural lands will provide an opportunity

to further remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

The establishment of new forests—afforestation—is an envi-

ronmentally beneficial activity. In the United States, 75 percent

of all forests are privately owned. At present, new tree plantings

are currently confined to two federal programs: the Conservation

Reserve Program and the Wetlands Reserve Program. These pro-

grams convert vulnerable cropland to grass or forests. Forests

on 7.5 million hectares (18.53 million acres, or 1 percent of the

continental United States area) in these programs could offset

about 0.25 percent of global “business-as-usual” greenhouse gas

emissions for the next 30 years. While this is only a very small

part of the emission reductions that would be needed, much more

land in the continental United States (32 to 90 million hectares, or

79 to 222 million acres) and other countries may be suitable for

such planting.

3. Preventing Deforestation. Up until the early 1900s, defor-

estation emitted more carbon dioxide than fossil-fuel use. Since

that time, forests in North America and Europe have recovered.

However, deforestation in the tropics has accelerated since the

1950s. In fact, since 1990 almost all worldwide deforestation has

occurred in the tropics, and tropical deforestation now accounts

for 18 percent of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide. (This is

roughly equivalent to the U.S. share of global emissions.)

All forests can remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere if

properly managed. Recognition of the intrinsic carbon sequestra-

tion value of today’s tropical forests can encourage wiser resource

management and help halt needless deforestation.

6 Reason Public Policy Institute

How Do Forest Products Contribute

to Carbon Sequestration?

A tree standing in the forest is approximately 50 percent water,

25 percent carbon, and 25 percent other minerals. When

a tree is harvested, not all the carbon contained in the tree is

released. A substantial portion of the tree is converted into

carbon-based products—including books, furniture, lumber for

housing, and a myriad of other items.

Wood is an energy-efficient building material. It takes 50

percent less energy to produce a wood product than a similar

product made from sheet metal, 60 percent less energy than a

similar product made from concrete, and 75% less energy than a

similar product made from steel. In addition to its energy-efficient

attributes, wood can store carbon dioxide in the form of carbon

for long periods of time. According to researchers, failure to

account for the long-term storage of carbon in wood-based prod-

ucts has caused overestimates of worldwide carbon dioxide emis-

sions by 10 percent.

Q&A About Forests and Global Climate Change 7

How Does Biomass Fuel Fit Into the

Equation?

T he benefits of forest absorption of carbon dioxide continue

after trees are harvested. In fact, carbon-containing, energy-

rich material from the forest is already used to power much of the

lumber- and paper-product industry’s manufacturing processes.

When a tree is processed to make a variety of consumer

goods, residual production material remains in the form of bark,

sawdust, and chips. This material is known as biomass fuel because

it is biological in nature and contains a mass of energy that has

been produced by the sun.

Biomass fuels are renewable through active and sustainable

forest management. Biomass energy is consicered a net-zero con-

tributor of greenhouse-gas emissions, because the carbon dioxide

released during biomass combustion is later withdrawn from the

atmosphere by forest regrowth. Through forest management prac-

tices, the carbon dioxide is reabsorbed, creating a closed-loop

system that has zero effect on the atmosphere.

The following domestic and international agencies agree that

biomass fuels represent a valid alternative to non-renewable fossil

fuels:

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s

Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories:

“Within the energy module, biomass consumption is assumed

to equal its regrowth. Any departures from this hypothesis are

counted within the Land-use Change and Forestry Module.” In

other words, biomass contribution to greenhouse gases is equal

to zero because all carbon accounting is conducted within the

practices of forestry management.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE): “Another way to

reduce carbon dioxide emissions is to displace some of the carbon

that is now emitted to the atmosphere from the combustion of

fossil fuels (an irreversible process) with carbon derived from

renewable resources. There is no net atmospheric carbon buildup

because carbon dioxide released in combustion is compensated for

8 Reason Public Policy Institute

by that withdrawn from the atmosphere during photosynthesis.”

The DOE’s guide for voluntary reporting of greenhouse gas emis-

sions states that “biofuels contain carbon that is part of the natural

carbon balance and that will not add to atmospheric concentrations

of carbon dioxide.”

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Inven-

tory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: “The

combustion of biomass and bio-based fuels…emits greenhouse

gases. Carbon dioxide emissions from these activities, however, are

not included in national emissions totals…because biomass fuels

are of biogenic origin. It is assumed that the carbon released

when biomass is consumed is recycled as U.S. forests and crops

regenerate, causing no net addition of CO2 to the atmosphere.”

Currently, the wood-products industry derives approximately

63 percent of its energy requirements from wood waste. The pulp

and paper industry derives about 57 percent of its energy needs

from wood waste and wood by-products—representing about 205

million barrels of oil equivalent per year, or the equivalent of

taking almost 19 million cars off the road annually.

Q&A About Forests and Global Climate Change 9

Conclusion

T here are still many unknowns regarding climate change, and

it is unclear that active greenhouse gas reduction policies are

prudent at this stage of understanding. Still, if greenhouse gas

reduction policies are to be implemented, they should be policies

that offer benefits in the near-term, as well as potential climate

change protection in the long term. Improvements in forest

and forest-product management can accomplish both objectives,

and the benefits are already scientifically understood. Carbon

sequestration by forests can both slow climate change should it

prove to pose serious threats to humans and the environment,

while dovetailing with other important environmental concerns,

such as air quality, habitat and species preservation, and resource

conservation.

10 Reason Public Policy Institute

About the Author

K enneth Green, D.Env., is Director of the Environmental

Program at Reason Public Policy Institute and an expert

reviewer for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

(IPCC)’s most recent report on climate change. Dr. Green has

published several peer-reviewed policy studies on climate change

for RPPI, including A Plain English Guide to the Science of Climate

Change, Climate Change Policy Options and Impacts, Evaluating the Kyoto

Approach to Climate Change, and A Baker’s Dozen: 13 Questions People

Ask About the Science of Climate Change. He received his doctorate in

environmental science and engineering from UCLA in 1994.

Related RPPI Studies

Reducing Global Warming Through Forestry and Agriculture, Steven R.

Schroeder and Kenneth Green, Plain English Guide No. 4, July

2001.

Exploring the Science of Climate Change, Kenneth Green, Plain English

Guide No. 3, August 2000.

Climate Change Policy Options and Impacts, Kenneth Green, Richard

McCann, Steve Moss, and Roy Cordato, Policy Study No. 252,

February 1999.

A Baker’s Dozen: 13 Questions People Ask About the Science of Climate

Change, Kenneth Green, October 1998.

A Plain English Guide to the Science of Climate Change, Kenneth Green,

Policy Study No. 237, December 1997.

Nuts and Bolts: The Implications of Choosing Greenhouse Gas Emission

Reduction Strategies, Richard McCann and Steven Moss, Policy Study

No. 171, November 1993.

Global Warming, Steven Moss and Richard McCann, Policy Study

No. 167, September 1993.

Q&A About Forests and Global Climate Change 11

Reason Public Policy Institute

3415 S. Sepulveda Blvd., Suite 400

Los Angeles, CA 90034

310-391-2245; 310-391-4395; www.rppi.org

Вам также может понравиться

- DovetailL LCA and Forest Carbon July 2011 PDFДокумент13 страницDovetailL LCA and Forest Carbon July 2011 PDFAkhanda Raj UpretiОценок пока нет

- Global Research PaperДокумент6 страницGlobal Research PaperDana MoeОценок пока нет

- Avoided Deforestation: A CLIMATE MITIGATION OPPORTUNITY IN NEW ENGLAND AND NEW YORKДокумент42 страницыAvoided Deforestation: A CLIMATE MITIGATION OPPORTUNITY IN NEW ENGLAND AND NEW YORKNeal McNamaraОценок пока нет

- Research No. 3Документ2 страницыResearch No. 3Ganaden Magdasoc NikaОценок пока нет

- The Ecology LadyДокумент6 страницThe Ecology LadyEnrique PrimoОценок пока нет

- Forest Management Guide: Best Practices in a Climate-Changed World: Best Practices in a Climate Changed WorldОт EverandForest Management Guide: Best Practices in a Climate-Changed World: Best Practices in a Climate Changed WorldОценок пока нет

- Envt ProjДокумент14 страницEnvt ProjShrikant TaleОценок пока нет

- As Sing MentДокумент6 страницAs Sing MentarslanhandedОценок пока нет

- What Is Social ForestryДокумент4 страницыWhat Is Social ForestryZafirah JamalОценок пока нет

- Tropical Tree Sequestration Co2 Tree-NationДокумент4 страницыTropical Tree Sequestration Co2 Tree-NationMarius AngaraОценок пока нет

- English Speaking-DeforestationДокумент8 страницEnglish Speaking-Deforestationikram729Оценок пока нет

- Carbon FootprintДокумент9 страницCarbon FootprintDino ParkОценок пока нет

- 10 Major Current Environmental ProblemsДокумент23 страницы10 Major Current Environmental ProblemslindakuttyОценок пока нет

- Deforestation: So Why Is It Happening??Документ2 страницыDeforestation: So Why Is It Happening??Shabaaz ShaikhОценок пока нет

- DeforestationДокумент23 страницыDeforestationAnonymous qYklwbОценок пока нет

- Deforestation in The United KingdomДокумент9 страницDeforestation in The United KingdomFind StepsОценок пока нет

- Miss. Maria Mashkoor International Business Management: Section 01 Mohammad Ali Jinnah University, IslamabadДокумент11 страницMiss. Maria Mashkoor International Business Management: Section 01 Mohammad Ali Jinnah University, IslamabadAhmer Masood QaziОценок пока нет

- Deforestation and Global Warming Pose Significant Challenges To Our PlanetДокумент4 страницыDeforestation and Global Warming Pose Significant Challenges To Our PlanetlewaОценок пока нет

- Written Article Analysis SampleДокумент4 страницыWritten Article Analysis SampleNo BuddyОценок пока нет

- Waring Etal GranthamDisc6 2020Документ9 страницWaring Etal GranthamDisc6 2020Meryem HusseinОценок пока нет

- Climate Change: A Call for Global Cooperation Understanding Climate Change: A Comprehensive GuideОт EverandClimate Change: A Call for Global Cooperation Understanding Climate Change: A Comprehensive GuideОценок пока нет

- Yupu, Forests and Climate ChangeДокумент14 страницYupu, Forests and Climate ChangeYupu ZhaoОценок пока нет

- Research Paper DeforestationДокумент8 страницResearch Paper Deforestationukldyebkf100% (1)

- DeforestationДокумент3 страницыDeforestationRashmiRavi NaikОценок пока нет

- DeforestationДокумент6 страницDeforestationKristine Camille Sadicon Morilla100% (1)

- Green Skills Notebook WorkДокумент2 страницыGreen Skills Notebook Workhitarth341Оценок пока нет

- Sonia's IRДокумент5 страницSonia's IRChoco O' BlockОценок пока нет

- 5 SiДокумент8 страниц5 SiNurul Ai'zah MusaОценок пока нет

- Environmental Sciences Term ReportДокумент4 страницыEnvironmental Sciences Term ReportMustufa khalidОценок пока нет

- Carbon Benefits of Wood-Based Products and EnergyДокумент2 страницыCarbon Benefits of Wood-Based Products and EnergyDayanah Rysiamie Dumandan Huraño IIОценок пока нет

- Forests Store A Substantial Amount of The World's Carbon and Increased Tree Death Will Only Propel Future Global Warming"Документ4 страницыForests Store A Substantial Amount of The World's Carbon and Increased Tree Death Will Only Propel Future Global Warming"Ahmad Hassan ChathaОценок пока нет

- The Reduce, Reuse, Recycle' Waste HierarchyДокумент4 страницыThe Reduce, Reuse, Recycle' Waste HierarchyRachel Joy LopezОценок пока нет

- Module 3 FullДокумент8 страницModule 3 FullSipra SamuiОценок пока нет

- Deforestation Final r1Документ17 страницDeforestation Final r1Fire100% (1)

- Affore Sation IngДокумент8 страницAffore Sation IngSanthosh PОценок пока нет

- Learner'S Packet No. 6 Quarter 1: SDO - HUMSS-TNCTC - Grade 11/12 - Q1 - LP 6Документ11 страницLearner'S Packet No. 6 Quarter 1: SDO - HUMSS-TNCTC - Grade 11/12 - Q1 - LP 6Ralph NavelinoОценок пока нет

- Research Paper On DeforestationДокумент5 страницResearch Paper On Deforestationafnhdcebalreda100% (1)

- Mitigation and Adaption For Climate ChangeДокумент17 страницMitigation and Adaption For Climate ChangeSzraxОценок пока нет

- #369Документ7 страниц#369John ManthiОценок пока нет

- Climate Change Is A Global ConcernДокумент5 страницClimate Change Is A Global ConcernHank Henry HaydenОценок пока нет

- Syamala EEE AДокумент7 страницSyamala EEE ASyamala GangulaОценок пока нет

- Introduction to Green Living : A Course for Sustainable LifestylesОт EverandIntroduction to Green Living : A Course for Sustainable LifestylesОценок пока нет

- Global Consumerism and Climate ChangeДокумент5 страницGlobal Consumerism and Climate ChangeReine CampbellОценок пока нет

- Global WarmingДокумент4 страницыGlobal WarmingVy PhạmОценок пока нет

- Env. Ethics Research PaperДокумент5 страницEnv. Ethics Research PaperReine CampbellОценок пока нет

- Organic Management for the Professional: The Natural Way for Landscape Architects and Contractors, Commercial Growers, Golf Course Managers, Park Administrators, Turf Managers, and Other Stewards of the LandОт EverandOrganic Management for the Professional: The Natural Way for Landscape Architects and Contractors, Commercial Growers, Golf Course Managers, Park Administrators, Turf Managers, and Other Stewards of the LandРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (1)

- Environmental Science: Preventive Measures and Alternative SolutionsДокумент17 страницEnvironmental Science: Preventive Measures and Alternative SolutionsJoshua AlamedaОценок пока нет

- Scribd Forest RevДокумент9 страницScribd Forest RevCyrus M.nОценок пока нет

- Urban Forests and Climate RegulationДокумент4 страницыUrban Forests and Climate Regulationwillie1duhartОценок пока нет

- Che Final ProjectДокумент4 страницыChe Final ProjectHarsh GoenkaОценок пока нет

- tác động +biện pháp 2 nn giữaДокумент4 страницыtác động +biện pháp 2 nn giữaleh75259Оценок пока нет

- Revise Concept PaperДокумент6 страницRevise Concept PaperJoshua BermoyОценок пока нет

- Geoooo 9 oДокумент6 страницGeoooo 9 oNUUR HIDAYAH BINTI NAZRI MoeОценок пока нет

- Cut Super Climate Pollutants Now!: The Ozone Treaty’s Urgent Lessons for Speeding Up Climate ActionОт EverandCut Super Climate Pollutants Now!: The Ozone Treaty’s Urgent Lessons for Speeding Up Climate ActionОценок пока нет

- Global WarmingДокумент2 страницыGlobal Warmingkhalid soffianОценок пока нет

- Prosondip Sadhukhan - Roll No (1911119)Документ5 страницProsondip Sadhukhan - Roll No (1911119)polar necksonОценок пока нет

- d834fab5860d5cf4b3949fecf86d3328Документ49 страницd834fab5860d5cf4b3949fecf86d3328reasonorgОценок пока нет

- D A: I T T: Ensity in Tlanta Mplications For Raffic and RansitДокумент6 страницD A: I T T: Ensity in Tlanta Mplications For Raffic and RansitreasonorgОценок пока нет

- 87189798b5d1d8ce1be8fb811a21a3d0Документ38 страниц87189798b5d1d8ce1be8fb811a21a3d0reasonorgОценок пока нет

- af5a2b0939b617d9604f31765df4f0bfДокумент23 страницыaf5a2b0939b617d9604f31765df4f0bfreasonorgОценок пока нет

- 623f73ae14a6925cdaaedeb38c210404Документ8 страниц623f73ae14a6925cdaaedeb38c210404reasonorgОценок пока нет

- 7227d934ecfa04d5db576c126f0385a6Документ53 страницы7227d934ecfa04d5db576c126f0385a6reasonorgОценок пока нет

- 6196f532a4d75327fb15c8a9785edcebДокумент6 страниц6196f532a4d75327fb15c8a9785edcebreasonorgОценок пока нет

- c1e3962b90998a26fe9e1cf3a939a264Документ8 страницc1e3962b90998a26fe9e1cf3a939a264reasonorgОценок пока нет

- W M M P L: Hy Obility Atters To Ersonal IfeДокумент34 страницыW M M P L: Hy Obility Atters To Ersonal IfereasonorgОценок пока нет

- 16 A R P S H S (1984-2005) : TH Nnual Eport On The Erformance of Tate Ighway YstemsДокумент51 страница16 A R P S H S (1984-2005) : TH Nnual Eport On The Erformance of Tate Ighway YstemsreasonorgОценок пока нет

- Leasing The Pennsylvania Turnpike: A Response To Critics of Gov. Rendell's PlanДокумент19 страницLeasing The Pennsylvania Turnpike: A Response To Critics of Gov. Rendell's PlanreasonorgОценок пока нет

- f4b3060c451c35f004519f3971d05fb3Документ13 страницf4b3060c451c35f004519f3971d05fb3reasonorgОценок пока нет

- 59f2e045a676b9c69bb9139b2c217bf3Документ2 страницы59f2e045a676b9c69bb9139b2c217bf3reasonorgОценок пока нет

- M T T: P F S: Iami Oll Ruckway Reliminary Easibility TudyДокумент42 страницыM T T: P F S: Iami Oll Ruckway Reliminary Easibility TudyreasonorgОценок пока нет

- d40314fbefcf4e491538f1d6613103e5Документ11 страницd40314fbefcf4e491538f1d6613103e5reasonorgОценок пока нет

- T U N R Faa' A T C S: He Rgent Eed To Eform The S Ir Raffic Ontrol YstemДокумент38 страницT U N R Faa' A T C S: He Rgent Eed To Eform The S Ir Raffic Ontrol YstemreasonorgОценок пока нет

- Easure A T T A F C ' H P ?: Re Obacco Axes The Nswer To Unding Hildren S Ealth RogramsДокумент10 страницEasure A T T A F C ' H P ?: Re Obacco Axes The Nswer To Unding Hildren S Ealth RogramsreasonorgОценок пока нет

- O L: R S E A: Ccupational Icensing Anking The Tates and Xploring LternativesДокумент58 страницO L: R S E A: Ccupational Icensing Anking The Tates and Xploring LternativesreasonorgОценок пока нет

- db38316bd23c0beef9d021a9fd7af1eaДокумент77 страницdb38316bd23c0beef9d021a9fd7af1eareasonorgОценок пока нет

- 5b1a53503729a50cbca6d5047efce846Документ10 страниц5b1a53503729a50cbca6d5047efce846reasonorgОценок пока нет

- U R A P: Sing The Evenues From Irport RicingДокумент12 страницU R A P: Sing The Evenues From Irport RicingreasonorgОценок пока нет

- E A P W: Vidence That Irport Ricing OrksДокумент9 страницE A P W: Vidence That Irport Ricing OrksreasonorgОценок пока нет

- 8a00bd89cb4421e0c9351b8be7e1b8cbДокумент4 страницы8a00bd89cb4421e0c9351b8be7e1b8cbreasonorgОценок пока нет

- Other Protected Species: Federal Law and Regulation. BNA Books: Washington, D.CДокумент9 страницOther Protected Species: Federal Law and Regulation. BNA Books: Washington, D.Creasonorg100% (1)

- e9f414aa6feb85192849cbfc177dcecdДокумент43 страницыe9f414aa6feb85192849cbfc177dcecdreasonorgОценок пока нет

- bec884a9b25a2e4c07228fec28eb1972Документ78 страницbec884a9b25a2e4c07228fec28eb1972reasonorgОценок пока нет

- Federal Interference in State Highway Public-Private Partnerships Is UnwarrantedДокумент2 страницыFederal Interference in State Highway Public-Private Partnerships Is UnwarrantedreasonorgОценок пока нет

- 07cd869c63c4e54c544786e1ec8935eeДокумент5 страниц07cd869c63c4e54c544786e1ec8935eereasonorgОценок пока нет

- 4ff6a1b3981fcee5a7864ff6eb3dab12Документ167 страниц4ff6a1b3981fcee5a7864ff6eb3dab12reasonorgОценок пока нет

- Edited by Geoffrey F. SegalДокумент81 страницаEdited by Geoffrey F. SegalreasonorgОценок пока нет

- Read The Text Below and Answer Questions 17 To 24.: TerhadДокумент2 страницыRead The Text Below and Answer Questions 17 To 24.: TerhadSyahirNОценок пока нет

- Ostomy Nutrition Guide - Patient Education Materials - UPMC PDFДокумент7 страницOstomy Nutrition Guide - Patient Education Materials - UPMC PDFkaktushijauОценок пока нет

- AP Electricity Tariff Fy2015-16Документ8 страницAP Electricity Tariff Fy2015-16somnath250477Оценок пока нет

- History of DenmarkДокумент21 страницаHistory of DenmarkSighninОценок пока нет

- Waste UtilizationДокумент3 страницыWaste UtilizationWellfroОценок пока нет

- Uptake of Sexed Semen by Uk Suckler Beef Producers: J.R. Franks, D.J. Telford and A. P. BeardДокумент16 страницUptake of Sexed Semen by Uk Suckler Beef Producers: J.R. Franks, D.J. Telford and A. P. Beardlucasfogaca19534Оценок пока нет

- Urton Animals&AstronomyQuechuaДокумент19 страницUrton Animals&AstronomyQuechuaGuerra Manuel100% (2)

- 2009 Novus Sustainability ReportДокумент81 страница2009 Novus Sustainability ReportNovusОценок пока нет

- ET050012 enДокумент112 страницET050012 ennguyenvu2412Оценок пока нет

- Vietnamese Rice Sector 2008Документ46 страницVietnamese Rice Sector 2008Thuan DuongОценок пока нет

- Quick Scan WFD Implementation in GermanyДокумент17 страницQuick Scan WFD Implementation in Germanyarta-kissОценок пока нет

- Approved KS EAS Standards - SAC List - 23rd July 2019Документ4 страницыApproved KS EAS Standards - SAC List - 23rd July 2019Felix MwandukaОценок пока нет

- Humss ScriptДокумент11 страницHumss ScriptVanito SwabeОценок пока нет

- Jaggery ProcessДокумент4 страницыJaggery ProcessAsh1ScribdОценок пока нет

- An Indigenous Fish Aggregating Method Practiced Along The Kolong River in Nagaon District of AssamДокумент6 страницAn Indigenous Fish Aggregating Method Practiced Along The Kolong River in Nagaon District of AssamziauОценок пока нет

- Soil Component and Its PropertiesДокумент21 страницаSoil Component and Its PropertiesThe Musician DharanОценок пока нет

- Matty Doolin EnglishДокумент15 страницMatty Doolin EnglishVictorAlarcon0% (1)

- William Engdahl - A Century of WarДокумент157 страницWilliam Engdahl - A Century of Wargrzes1Оценок пока нет

- The Beer Geek Handbook - Living A Life Ruled by Beer (2016)Документ58 страницThe Beer Geek Handbook - Living A Life Ruled by Beer (2016)zaratustra21Оценок пока нет

- ZXCabbage Fertilizer Requirements PDF - Google SearchДокумент1 страницаZXCabbage Fertilizer Requirements PDF - Google SearchLesley ShiriОценок пока нет

- The 13 Moro TribesДокумент4 страницыThe 13 Moro TribesWali McGuire0% (1)

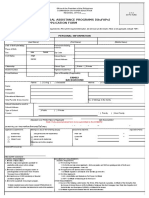

- CHED StuFAPs Application FormДокумент2 страницыCHED StuFAPs Application FormJm Neutron100% (1)

- Banana Macro Propagation ProtocolДокумент6 страницBanana Macro Propagation ProtocolOlukunle AlabetutuОценок пока нет

- Story About Happy CarrotДокумент1 страницаStory About Happy Carrotandreapirro.spamОценок пока нет

- System of Exchange. A Long Time Ago There Were No Coins. There Was No Such Thing As Money. Before TheДокумент3 страницыSystem of Exchange. A Long Time Ago There Were No Coins. There Was No Such Thing As Money. Before TheStefanusBrianPranaSattvaОценок пока нет

- Jordan - Evaluation of Irrigation MethodsДокумент24 страницыJordan - Evaluation of Irrigation MethodsAnonymous M0tjyW100% (1)

- Mariculture: Growth in Milkfish Production in Mati CityДокумент27 страницMariculture: Growth in Milkfish Production in Mati CityKeith Ver Caputol ObateОценок пока нет

- Definition of Co-Operation: ObjectivesДокумент12 страницDefinition of Co-Operation: ObjectivesRekha SoniОценок пока нет

- Revised CBSE Class 12 Economics Syllabus 2020-21Документ7 страницRevised CBSE Class 12 Economics Syllabus 2020-21Vaibhav guptaОценок пока нет

- Evaluating Ecotourism in LaikipiaДокумент129 страницEvaluating Ecotourism in LaikipiaPrince AliОценок пока нет