Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

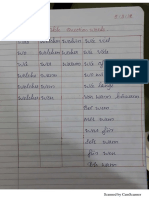

Nom, Akk, Dat Gen

Загружено:

Imola PalИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Nom, Akk, Dat Gen

Загружено:

Imola PalАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Handout: Nominative, Accusative, and Dative: When to Use Them

Nominative

for the subject of a sentence: who or what is doing this?

Der Student lernt Deutsch.

for predicate nouns: when the main verb is sein or werden, use the nominative for both subject and predicate nouns.

Das ist ein Tisch.

Accusative

for the direct object of a sentence: who or what is being <verbed>?

Ich habe einen Tisch. What is being had? A table.

Note that the very common expression "es gibt" (there is/are) requires that the noun be in the accusative case because

it is grammatically a direct object.

Es gibt einen Stuhl da drben. There is a chair over there.

after the accusative prepositions and postpositions: durch, fr, gegen, ohne, um (memory aid: dogfu), as well as the

postpositions bis and entlang . If a noun follows these prepositions, it will ALWAYS be in the accusative!

Er geht um den Tisch. Around what? The table.

Ist das Geschenk fr mich? For whom? For me.

time expressions in a sentence are usually in accusative: jeden Tag, letzten Sommer, den ganzen Tag, diesen

Abend, etc. We havent officially learned this yet, but its good to know.

Jeden Morgen esse ich Brot zum Frhstck. Every morning.

Dative

for the indirect object of a sentence. An indirect object is the beneficiary of whatever happens in a sentence. Its

usually a person, although it doesnt have to be. If you ask yourself: TO whom or FOR whom is this being done?, the

answer will be the indirect object, and in German it will need the dative case. Remember that not every sentence will

have an indirect object -- only some verbs allow an indirect object: to give (to), to bring (to), to tell (to), to buy (for), to

send (to) are some examples of verbs that will almost always have an indirect object. In English, we don't distinguish the

direct and indirect object in the forms of words; instead, we often use "to" or "for" to mark these.

Ich gebe der Frau ein Buch. Im giving her a book = a book to her.

Er schenkt mir ein Buch. He's giving me a book.

Ich habe das dem Mann schon gesagt. I already told the man that.

after the dative prepositions: aus, auer, bei, mit, nach, seit, von, zu (memory aid: Blue Danube Waltz). A noun

immediately following these prepositions is ALWAYS in the dative case. There are many possible translations of these

prepositions, depending on exactly what the context of the sentence is. Please refer to your textbook, pp. 239-240, for

more detailed explanation of the meanings of each preposition.

Sie haben ein Geschenk von ihrem Vater bekommen. From their father.

Auer meiner Mutter spricht meine ganze Familie Deutsch. Except for my mother.

Ich fahre am Wochenende zu meiner Tante in Minnesota. To my aunt's.

after dative verbs: helfen, danken, gefallen, gehren, schmecken, passen. See your book for more details on each

verb. There's no direct translation that explains why these verbs take a dative object, it's just an idiosyncrasy of German -

- it's best just to memorize these verbs as requiring the dative, even though the following noun doesn't 'feel' like an

indirect object.

Ich helfe dir mit deinen Hausaufgaben. I'm helping you = I'm giving help to you.

Wir danken Ihnen, Herr Stein. We're thanking you = we're giving thanks to you.

with some adjectives which describe a condition. You'll just need to know these as fixed phrases.

Mir ist warm. To me (it) is warm / I'm warm.

Wie geht es dir? How's it going / How are you doing?

the preposition in often uses the dative case. Later this week you will be learning more about this preposition and

how to use it correctly. For now, the most you need to know is that when in is used with a stationary verb (e.g. Hes in

the house), it takes the dative case.

Der Tisch steht in der Kche. Where is it? In the kitchen.

Mein Schreibtisch ist im Arbeitszimmer. Note that im = in dem

Die Kinder sind in ihren Zimmern. The children are in their rooms, plural.

Summary: When to use which case

So, when you're trying to decide which case to use, consider the following things:

1. Is it a fixed expression? (such as Mir ist kalt, or Es tut mir Leid)

2. Does the noun follow either an accusative or a dative preposition? If so, this should be easy, since the

preposition determines the case. Just make sure you know which prepositions take the accusative (dogfu)

and which take the dative (Blue Danube Waltz). Once you have the accusative and dative prepositions

memorized, these are your friends when it comes to case -- they tell you exactly what to do. (Next semester

you will learn some other prepositions which aren't quite so easy.)

3. Is the verb a dative verb? If so, the object will be in the dative.

4. If none of the other conditions apply, then you need to determine which noun in the sentence is

the subject, and put that in nominative. Then look for a direct object (put in accusative) and indirect

object (put in dative). Remember that not every sentence necessarily has a direct object and an indirect

object: some have only one or the other, or none at all.

If you need reference to these, here's a table of the different endings and pronouns in the three cases:

Nom Akk Dat (Poss)

1 sg ich mich mir (mein_)

2 sg du dich dir (dein_)

3 sg er ihn ihm (sein_)

3 sg sie sie ihr (ihr_)

3 sg es es ihm (sein_)

1 pl wir uns uns (unser_)

2 pl ihr euch euch (euer_)

3 pl sie sie ihnen (ihr_)

form Sie Sie Ihnen (Ihr_)

masc der den dem

fem die die der

neut das das dem

plur die die den (+ _n)

masc ein einen einem

fem eine eine einer

neut ein ein einem

plur keine keine keinen (+ _n)

masc unser unseren unserem

fem unsere unsere unserer

neut unser unser unserem

plur unsere unsere unseren (+ _n)

masc dieser diesen diesem

fem diese diese dieser

neut dieses dieses diesem

plur diese diese diesen (+ _n)

It may help you to remember these changes with the mnemonic device rese nese mr mn -- in other words, der-die-das-

die, den-die-das-die, dem-der-dem-den.

The question words wer - wen - wem

To ask who in German, you need to decided whether the who is the subject, the direct object, or the indirect

object. The forms of wer are just like the masculine article: wer - wen - wem.

Wer ist das? Who is that?

Wer kommt morgen zur Party? Whos coming to the party tomorrow?

Wen hast du eingeladen? Whom did you invite?

Wem hast du das Buch gegeben? To whom did you give the book?

Handout: Der Genitiv

The genitive case is used in German to express either:

possession, ownership, belonging to or with:

Hier ist das Auto meines Vaters. Here is my fathers car.

Hast du die Freunde meiner Schwester gesehen? Did you see my sisters friends?

of in English, when referring to a part or component of something else:

Am Anfang des Kurses haben wir viel gelernt. We learned a lot at the beginning of the course.

Manche Seiten des Buches fehlen. Some pages of the book are missing.

in addition, there are a handful of prepositions that require the genitive case:

anstatt (statt) -- instead of:

Anstatt eines Wagens haben sie ein Motorrad gekauft. Instead of a car they bought a motorcycle.

auerhalb -- outside of:

Der Park liegt auerhalb der Stadt. The park is outside of the city.

innerhalb -- inside of, within:

Sie sind innerhalb eines Tages angekommen. They arrived within a day.

trotz -- in spite of:

Ich gehe zur Party trotz meiner Erkltung. Im going to the party in spite of my cold.

whrend -- during, in the course of:

Whrend der Party habe ich mich sehr schlecht gefhlt. During the party I felt very ill.

wegen -- because of:

Wir sind wegen des Wetters zu Hause geblieben. We stayed at home because of the weather.

You may occasionally see other genitive prepositions, such as diesseits (on this side of), jenseits (on that side of)

or dank (thanks to, due to), but in general the most common genitive prepositions -- and the only ones youre

responsible for knowing -- are listed above.

The formation of the article in the genitive is fairly simple, as there are only two different endings (-es for masculine

and neuter, -er for feminine and plural). However, the genitive case is unusual in German because it adds an ending

not only to the articles, but to masculine and neuter nouns as well. This ending is -es for single-syllable masculine

and neuter nouns. When the noun is more than one syllable long, the ending is usually just -s.

masc neut fem pl

des Mannes des Buches der Frau der Blumen

meines Mannes meines Buches meiner Frau meiner Blumen

Although you arent required to learn them, the adjective endings for the genitive case are extremely easy:

masculine and neuter are always -en, feminine and plural are either -en (if theres an article) or -er (with no

article):

with article without article (rare!)

masc die Frau des alten Mannes der Geschmack kalten Kaffees

fem der Sohn meiner jungen Schwester anstatt heier Suppe

neut ein Zimmer innerhalb des groen Gebudes trotz schlechten Wetters

pl die Augen der schwarzen Katzen wegen langer Tage

In addition, you may see the question word wessen: this is merely the genitive form of wer, and means whose. It

never has any other form or endings:

Wessen Auto ist das? Whose car is that?

Wessen Bcher liegen hier? Whose books are lying here?

Word of warning:

Your impulse may be to simply put an -s before a noun to indicate the possessive, as we do in English (my fathers

car). However, saying mein Vaters Wagen is not only incorrect in German, it is incomprehensible and makes no

sense at all. You must rephrase: der Wagen meines Vaters. If it helps to think of it as the car of my father,

thats fine, since the meaning is the same as English my fathers car.

Remember that with personal names, you can simply add an -s to indicate the possessive. But when referring to

a common noun rather than a proper name, the genitive formation must be used:

Marias Freund heit Thomas. Der Freund meiner Schwester heit Thomas.

Hans Mutter ist nett. Die Mutter meines Freundes ist nett.

Wisconsins Hauptstadt ist Madison. Die Hauptstadt dieses Bundeslands ist Madison.

Alternate method:

The genitive case has been disappearing in German for some time now. Its not dead yet, but you wont often hear

it in informal situations -- its mostly reserved for formal writing or elevated styles of speech. Instead of the genitive

to indicate possession, you will often hear the dative used with the preposition von:

das Haus meines Freundes = das Haus von meinem Freund

der Onkel meiner Mutter = der Onkel von meiner Mutter

die Namen der Kinder = die Namen von den Kindern

Вам также может понравиться

- Studio Ghibli Beginner Piano BookДокумент192 страницыStudio Ghibli Beginner Piano BookAidan Coffey94% (16)

- Using German PDFДокумент349 страницUsing German PDFLy Thanh Yen96% (24)

- All You Need To Know About German PrepositionsДокумент1 страницаAll You Need To Know About German PrepositionsMark Corella100% (1)

- Separable Verbs in GermanДокумент8 страницSeparable Verbs in GermanMEHAKPAL DHIMAN100% (1)

- Functions of Nouns: Subject (Agent)Документ3 страницыFunctions of Nouns: Subject (Agent)Vishnu Ronaldus NarayanОценок пока нет

- Handout - Der DativДокумент6 страницHandout - Der DativlolapodoroОценок пока нет

- FSI - Czech FAST - Student Text PDFДокумент241 страницаFSI - Czech FAST - Student Text PDFbany78100% (2)

- German Learning and Discussion Resource ListДокумент33 страницыGerman Learning and Discussion Resource ListHeitor Fernandes100% (1)

- Assimil - Spanish With Ease Scanned by TrongДокумент255 страницAssimil - Spanish With Ease Scanned by TrongShamaine Trisha100% (1)

- German Grammar 1Документ4 страницыGerman Grammar 1Renan AbudОценок пока нет

- Wo-/ Da-Wörter Theorie: German EnglishДокумент4 страницыWo-/ Da-Wörter Theorie: German EnglishXtin ClaraОценок пока нет

- Verbs GermanДокумент5 страницVerbs Germantimcaras100% (1)

- Top 100 German VerbsДокумент1 страницаTop 100 German Verbsbekirm10% (1)

- Handout - Nominative, Accusative, and Dative - When To Use ThemДокумент2 страницыHandout - Nominative, Accusative, and Dative - When To Use ThemZulqarnain ShahОценок пока нет

- German Modal ParticlesДокумент3 страницыGerman Modal ParticlesMonОценок пока нет

- German AdverbsДокумент25 страницGerman Adverbsmengelito almonteОценок пока нет

- German WordsДокумент20 страницGerman WordsMirela AlbuОценок пока нет

- 59 Ready-To-Use Phrases To Ace Your German Oral ExamДокумент8 страниц59 Ready-To-Use Phrases To Ace Your German Oral ExamAnishaОценок пока нет

- German Vocab BookДокумент130 страницGerman Vocab BookDipen Pandya100% (1)

- Learn Turkish PDFДокумент44 страницыLearn Turkish PDFKlára BraunОценок пока нет

- German 1000sentences SampleДокумент7 страницGerman 1000sentences Sampleprabhash14Оценок пока нет

- Personal Pronouns:: Ist Bin Komme SprechenДокумент14 страницPersonal Pronouns:: Ist Bin Komme SprechenMaria Erica Jan MirandaОценок пока нет

- German Cases, Nominative, Accusative, Dative, GenitiveДокумент4 страницыGerman Cases, Nominative, Accusative, Dative, GenitiveadnannandaОценок пока нет

- Pali For BeginnersДокумент33 страницыPali For BeginnersANKUR BARUA100% (1)

- English Revision PaperДокумент11 страницEnglish Revision Paperdk.hjh. Ana100% (1)

- Komparativ SuperlativExplДокумент16 страницKomparativ SuperlativExplshirley pit-oyОценок пока нет

- PräpositionenДокумент8 страницPräpositionenfperezbrОценок пока нет

- Tips - Duo LingoДокумент95 страницTips - Duo Lingokaran_arora777100% (1)

- Dativ VerbДокумент3 страницыDativ VerbSuman JojijuОценок пока нет

- A Reflection On: Sex, Gender, and Society by Ann OakleyДокумент1 страницаA Reflection On: Sex, Gender, and Society by Ann Oakleyjhonel_faelnar100% (1)

- Grammatik Im Blick Grammar Supplement GermanДокумент40 страницGrammatik Im Blick Grammar Supplement GermanLydia Benny RotariuОценок пока нет

- German Verb Prefixes - Separable and Inseparable PrefixesДокумент3 страницыGerman Verb Prefixes - Separable and Inseparable PrefixesJosé Marìa LlovetОценок пока нет

- KonjunktionenДокумент7 страницKonjunktionenThales Macêdo100% (1)

- German Vocab BookДокумент130 страницGerman Vocab BookRubab ZahraОценок пока нет

- Temporal Adverbs Dealing With The DayДокумент6 страницTemporal Adverbs Dealing With The DayIlinca StanilaОценок пока нет

- Separable Prefix Verbs Grimm: Verbs Präsens - Trennbare VerbenДокумент5 страницSeparable Prefix Verbs Grimm: Verbs Präsens - Trennbare VerbenRam Sharat Reddy BОценок пока нет

- Artikel For Household & Furniture PDFДокумент2 страницыArtikel For Household & Furniture PDFMMR100% (1)

- Arabic Lesson PlanДокумент2 страницыArabic Lesson Planapi-28138909967% (6)

- Carl Duisberg Deutsch Pruefungen 2016 ENДокумент1 страницаCarl Duisberg Deutsch Pruefungen 2016 ENPolacosОценок пока нет

- German For Beginners in 7 Lessons: Olena ShypilovaДокумент8 страницGerman For Beginners in 7 Lessons: Olena ShypilovaFie Zain100% (1)

- Handout - Kasus - Nominativ Und AkkusativДокумент3 страницыHandout - Kasus - Nominativ Und AkkusativpsjcostaОценок пока нет

- 400 Golden Rules of English GrammarДокумент50 страниц400 Golden Rules of English GrammarTanvir Fuad75% (4)

- Learn GermanДокумент7 страницLearn GermanLittle SAi100% (1)

- Deutschkurs A1 PronunciationДокумент6 страницDeutschkurs A1 PronunciationHammad RazaОценок пока нет

- Infinitiv Mit Zu TheorieДокумент2 страницыInfinitiv Mit Zu TheorieDiego_chg100% (1)

- Teaching Pronunciation: Using The Prosody Pyramid Judy B. GilbertДокумент56 страницTeaching Pronunciation: Using The Prosody Pyramid Judy B. GilbertSLavОценок пока нет

- Temporal AdverbsДокумент10 страницTemporal AdverbsZrnce SoliОценок пока нет

- A2 GermanДокумент6 страницA2 GermanIndrama Purba100% (1)

- 7-Distinct-Uses-Of-The-German Verb Werden PDFДокумент7 страниц7-Distinct-Uses-Of-The-German Verb Werden PDFRatheesh KrishnanОценок пока нет

- German Grammar CheatsheetДокумент5 страницGerman Grammar Cheatsheet강우현Оценок пока нет

- Passiv DeutschДокумент3 страницыPassiv DeutschСтефанија ТемелковскаОценок пока нет

- Zu and Um ZuДокумент7 страницZu and Um ZuSisilia SyanneОценок пока нет

- Toms Deutschseite - Possible Time-TableДокумент4 страницыToms Deutschseite - Possible Time-TablepriaОценок пока нет

- Reflexive Verbs GermanДокумент5 страницReflexive Verbs GermanRam Sharat Reddy BОценок пока нет

- The Unreal ConditionalДокумент3 страницыThe Unreal ConditionalImola PalОценок пока нет

- Präpositionen Dativ Oder AkusativДокумент1 страницаPräpositionen Dativ Oder AkusativElena CeОценок пока нет

- Arabic Manual Levantine F E CrowДокумент368 страницArabic Manual Levantine F E CrowKevin MoggОценок пока нет

- Theory DemonstrativpronomenДокумент2 страницыTheory Demonstrativpronomensofi2Оценок пока нет

- German GrammatikДокумент9 страницGerman Grammatikgajanan aher0% (1)

- List of Trennbare Verbs in GermanДокумент2 страницыList of Trennbare Verbs in GermanNi DhalОценок пока нет

- The Present Tense (Das Präsens)Документ5 страницThe Present Tense (Das Präsens)Mark CorellaОценок пока нет

- The German Spelling ReformДокумент5 страницThe German Spelling ReformkarlTronxoОценок пока нет

- German Verb Prefixeeees: - Separable 2 - With Verb PrefixesДокумент1 страницаGerman Verb Prefixeeees: - Separable 2 - With Verb PrefixescvetanovicmarjanОценок пока нет

- German BooksДокумент1 страницаGerman BookseinszweidreiОценок пока нет

- German Grammar BookДокумент3 страницыGerman Grammar BookGenesis RosarioОценок пока нет

- Sentence StructureДокумент33 страницыSentence StructureChantik Rose MizatoОценок пока нет

- German Participle I vs. Participle IIДокумент1 страницаGerman Participle I vs. Participle IIPearl MykaОценок пока нет

- German Grammar: Ig, Ich, Ing Ling En, El Er Ig Ich Ing Ling en El ErДокумент9 страницGerman Grammar: Ig, Ich, Ing Ling En, El Er Ig Ich Ing Ling en El ErDeepa BalwallyОценок пока нет

- GENETIVДокумент4 страницыGENETIVKatherine VillalunaОценок пока нет

- UNIT 11 Study and WorkДокумент6 страницUNIT 11 Study and WorkLê ViệtОценок пока нет

- German A2Документ7 страницGerman A2Bhagyashri RqutОценок пока нет

- A2 NotesДокумент93 страницыA2 NotesPooja RayОценок пока нет

- Handout: Nominative, Accusative, and Dative: When To Use Them NominativeДокумент4 страницыHandout: Nominative, Accusative, and Dative: When To Use Them NominativePietro FlorioОценок пока нет

- Nominative, Accusative, and Dative: When To Use Them: (Hausaufgaben)Документ5 страницNominative, Accusative, and Dative: When To Use Them: (Hausaufgaben)Souvik BiswasОценок пока нет

- Barenaked LadiesДокумент1 страницаBarenaked LadiesImola PalОценок пока нет

- Money IdiomДокумент5 страницMoney IdiomImola PalОценок пока нет

- I Had/i've Had/i Used To Have Breakfast With BenДокумент2 страницыI Had/i've Had/i Used To Have Breakfast With BenImola PalОценок пока нет

- Roman ConsilsДокумент122 страницыRoman ConsilsImola PalОценок пока нет

- Animula - W. Revised 1st Ch.Документ203 страницыAnimula - W. Revised 1st Ch.Imola PalОценок пока нет

- Characters and Events of Roman HistoryДокумент100 страницCharacters and Events of Roman HistoryImola PalОценок пока нет

- How People Learn A LanguageДокумент3 страницыHow People Learn A LanguageImola PalОценок пока нет

- الأصل الأول engДокумент61 страницаالأصل الأول engroro rokrokОценок пока нет

- Upper Intermediate (Italian)Документ79 страницUpper Intermediate (Italian)Cesar MessiОценок пока нет

- Beyond Explicit Rule LearningДокумент27 страницBeyond Explicit Rule LearningDaniela Flórez NeriОценок пока нет

- Towards A Redefinition of Feminist Translation PracticeДокумент16 страницTowards A Redefinition of Feminist Translation PracticeThahp ThahpОценок пока нет

- Materi Relative ClauseДокумент5 страницMateri Relative ClauseHendri BunawanОценок пока нет

- GRM 1Документ55 страницGRM 1Mady RadaОценок пока нет

- Module 3Документ12 страницModule 3CrisОценок пока нет

- Words and Expressions To Connect Ideas Orally and in WritingДокумент4 страницыWords and Expressions To Connect Ideas Orally and in WritingKarina ElizabethОценок пока нет

- Baulkham Hills Continuers Latin 2014Документ16 страницBaulkham Hills Continuers Latin 2014Eric WareОценок пока нет

- Common German Beginner MistakesДокумент4 страницыCommon German Beginner MistakesArtim AfsharОценок пока нет

- English Grammar (WWW - Qmaths.in)Документ169 страницEnglish Grammar (WWW - Qmaths.in)aayushcooolzОценок пока нет

- Offline Textbook - A Foundation Course in Reading GermanДокумент125 страницOffline Textbook - A Foundation Course in Reading GermanBobbyDongОценок пока нет

- FRC Class 4 GrammarДокумент78 страницFRC Class 4 Grammararunima kumarОценок пока нет

- Lecture 7. Old English Grammar. Morphology.Документ4 страницыLecture 7. Old English Grammar. Morphology.aniОценок пока нет

- Verbs Like Gustar Direct Object Pronouns: Formal Ud. & Uds. CommandsДокумент2 страницыVerbs Like Gustar Direct Object Pronouns: Formal Ud. & Uds. CommandsOlivia Groeneveld100% (1)

- Book of Abstract RUEG Conference 2021Документ47 страницBook of Abstract RUEG Conference 2021Marius KellerОценок пока нет

- Application Form: Emaar Digihomes, Phase 1 Sector 62, GurugramДокумент17 страницApplication Form: Emaar Digihomes, Phase 1 Sector 62, GurugramF2 InfosoftОценок пока нет

- La Vida EstudiantilДокумент9 страницLa Vida EstudiantilHerlleyОценок пока нет

- Shitthatdidnthappen - TXT 06Документ1 000 страницShitthatdidnthappen - TXT 06SnapperifficОценок пока нет