Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Measuring Consumer Brand Preference

Загружено:

sufyanbutt0070 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

76 просмотров12 страницarm

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документarm

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

76 просмотров12 страницMeasuring Consumer Brand Preference

Загружено:

sufyanbutt007arm

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 12

Agricultural & Applied Economics Association

Measuring Consumer Brand Preference

Author(s): D. I. Padberg, F. E. Walker, K. W. Kepner

Source: Journal of Farm Economics, Vol. 49, No. 3 (Aug., 1967), pp. 723-733

Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the Agricultural & Applied Economics

Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1236904

Accessed: 27/03/2009 10:10

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the

scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that

promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Agricultural & Applied Economics Association and Blackwell Publishing are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Farm Economics.

http://www.jstor.org

Measuring

Consumer Brand Preference*

D. I. PADBERG, F. E.

WALKER,

AND K. W. KEPNER

A model is presented

which quantifies

the brand preferences motivating

consumer purchases

from

supermarket displays.

This method of

studying

brand preference

uses the

supermarket display

as a laboratory

for

conducting

controlled experiments. Price, quality

of display space, point-of-sale

merchan-

dising, and display

allocation are controlled to isolate the effect of brand

preference upon consumer purchases. Quantitative

estimates of the

percent-

age

of brand-motivated sales and the

proportion

of brand-motivated cus-

tomers with

allegiance

to each brand are

developed.

The effect of

price

differentials upon

the brand-preference pattern is also investigated.

The

model is applied

to fluid milk sales through supermarkets in a midwestern

metropolitan

market.

NE of the distinctive features of modern

marketing

is the extensive

tOJ use of brands

by

manufacturers and distributors and the

general

preference

for branded items

by

consumers. In our

marketing process,

brands are an

important

communicator of economic information; they

aid

in

product

identification and tend to

protect buyers

and sellers from un-

certainty regarding product quality.

The

importance

of information

concerning

consumer attitudes toward,

acceptance of, preferences for, and

loyalty

to various brands within a

product

class has

long

been

recognized.

These

phenomena

often mean the

difference between success and failure for individual firms.

They

also have

an

important

influence on the nature of

competition

in

many

industries.

Yet this

important

area of economic behavior has not been

operationally

defined,

and methods of measurement are crude at best.

The desire for status in our

complex

social

system

has a

significant

in-

fluence on consumer

preference

and brand

loyalty.

The

study

of these

social influences has contributed to the

understanding

of the basis of con-

sumer brand

preferences

and

loyalties

in a

general way.

But it has not led

to

quantitative analyses

which allow the isolation of brand

preferences

from other factors

affecting

consumer

purchases,

such as

price, point-of-

purchase merchandising,

or

display-space

allocation.

In

general,

three alternative

approaches

have been

developed

in

studying

consumer brand

preferences

and associated

purchase

behavior. Consumer

surveys

have focused on

developing

a

profile

of consumer attitudes and

*

This article

reports

research conducted at the Ohio

Agricultural Experiment

Station under

Hatch 267, "Selling Strategy

and

Selling

Cost in the Ohio Fluid Milk

Industry."

D. I. PADBERG is associate

professor

of marketing

at New York State College

of

Agriculture,

Cornell

University.

F. E. WALKER is associate

professor

of agricultural

economics and rural

sociology

at the Ohio State

University.

W. K. KEPNER is assistant

professor of agricultural

economics at Purdue

University.

723

D. I.

PADBERG,

F. E.

WALKER,

AND K. W. KEPNER

projecting

the

type

of

purchase

behavior that would be consistent with

these attitudes. Problems arise, however, when consumers are

encouraged

to

explain

motivations which

they

do not understand.

Although

consumers

may

behave in a

systematic way,

it cannot be inferred that

they

are aware

of the behavior

pattern

or that

they

understand the

underlying

motivations.

In addition, questions may

cause consumers to

respond

in a

way

that is

different from

customary

behavior in order to make their actions seem

"rational."

A second

approach

uses

panels

of consumers who record

purchases;

it

projects

behavior on the basis of a

profile developed

from

previous buying

activities.1 But

although

this

type

of research has made

important

con-

tributions to our

professional understanding

of consumer

buying behavior,

numerous

problems

related to such factors as cost, time, voluntary

co-

operation, sampling, recall, fatigue,

and falsification are involved. In addi-

tion,

it does not

provide any

information on the

many

identifiable factors

that influence the

purchase

decision.

The third and

perhaps

most recent

approach

is

designed

to

analyze

be-

havior

directly [3].

Tucker has indicated that "no consideration should

be

given

to what the

subject

thinks or what

goes

on in his central nervous

system;

his behavior is the full statement of what brand

loyalty

is"

[6,

p.

32].

Studying purchase

behavior

directly may

have lower academic

ap-

peal

for some, inasmuch as

only vague

inferences can be made

concerning

the

composite

of

psychological, social,

and economic forces which form the

basis for consumer behavior. However, this

approach may

lend itself to

quantitative analysis

more

fully

than the other two

approaches.

If the

impact

of brand

loyalties upon

consumer

purchase

behavior can be iso-

lated,

such measures will have usefulness in motivation research as well as

in business decisions.

An excellent

laboratory

for

measuring

consumer

purchase responses

to

controlled environmental conditions is

provided by

the

supermarket.

Con-

sumers

shopping

in

supermarkets

make

purchase

decisions from

present

displays

without assistance or bias from store

personnel.

This

"purchase

decision

laboratory"

can be controlled in several

ways.

Factors such as

price

and

display

can be controlled so as to neutralize their effects over re-

peated

tests or varied

systematically

to isolate their influence.

By

neutraliz-

ing

all factors

except

the brand

preferences

which the

shopper brought

in

with her, we make it

possible

to measure the effect of this

preference

vari-

able.

By

responding

to variations in the

merchandising display,

consumers

provide

information

concerning

the relative

importance

of various factors

affecting purchase

decisions. Since

they

are unaware that

they

are

par-

ticipating

in a

test, they do not have to

try

to

explain

behavior which they

do not understand.

1

An extensive bibliography

and an

interesting appraisal

of

problems

of

accuracy

in research

of this

type

are

presented by

Sudman

[4, 5].

724

MEASURING CONSUMER BRAND PREFERENCE

Consumer

response

to brands is of

signal importance

in

shaping

the na-

ture of

competition

between the

large

institutions at the retail level and

the

large

institutions which

process

food items. Food

processors

were the

earliest sector of the food distribution

system

to

apply

advanced technol-

ogy.

As a

result, they developed "big

business"

organizations

and

strong

national brands.

Acceptance

of these brands was based

upon

the

superiority

of the products

identified

by

the brands after account was taken of

price

differences. In recent

years,

retail institutions have

grown large enough

to

integrate

into the technical functions of food

processing. Processing

tech-

nology

is more

widely

known and is

generally

available to

integrating

re-

tailers. The extensive

development

of distributor brands indicates a

general

erosion of the

competitive position

once held

by processors.2

How this

competitive struggle

is resolved will

depend upon

consumer

response

to the

variables involved in their

purchase

decisions. These are outlined below.

Consumer Purchase Decisions

It is

possible

to

identify

five

major

factors which influence the

proportion

of total

product

sales made

by

each brand of a

product

class

displayed

in a

supermarket:

(1)

relative brand

prices,

(2)

the

proportion

of

display space

allocated to each brand,

(3)

the

quality

of

display space,

(4)

point-of-sale

advertising

and

promotion,

and

(5)

consumer brand attitudes and

pref-

erences. The first four of these factors are direct dimensions of the

purchase

environment. The fifth is a residual of

advertising

and

promotion,

habits

and

experience,

which is

brought

to the

purchase

environment

by

the

consumer.

A

primary objective

of this

analysis

is to isolate and

quantify

the fifth

item, namely,

brand

preferences

of consumers. The

procedure

outlined in

the model

essentially

involves

controlling

the other four

aspects

of the

purchase

environment and

thereby isolating

the effect of brand

preferences.

In

many merchandising situations, however, the effects of brand

preferences

and relative brand

prices

work

together

in either a cumulative or a com-

pensating way.

For this reason, it

may

also be of interest to

quantify

the

combined effects of consumer brand

preferences

and differences in brand

prices.

While this is

possible

with the model and is discussed

later, the basic

model is

developed

to fit conditions where brand

prices

are

equal.

With

equal

brand

prices,

equal

display quality conditions,

and no

point-

of-sale

advertising

or

promotion,

it is

hypothesized

that the sales of each

brand would be

proportional

to the

display space

allocated to each if all

buyers

were indifferent

concerning

brand choice.

Conversely,

it is

hypoth-

esized that if all

buyers

had a brand

preference

there would not be

any

relationship

between the

percentage

of total sales for a brand and the

2

See Technical

Study

10 of the National Commission on Food

Marketing [2 ] for a discussion

of

private-label operations

of food retailers and measurements of

magnitude of

private-label

business.

725

D. I.

PADBERG,

F. E.

WALKER,

AND K. W. KEPNER

percentage

of

display space

allocated to it. In the latter situation, the sales

of each brand would

correspond

to the

percentage

of

buyers

that had a

preference

for each one. These situations

represent

what

might

be termed

the extremes of consumer behavior with

regard

to brands. That is,

all

buyers

could be

completely

indifferent or all could have a definite and

pronounced

brand

preference.

In

reality,

one finds that sales of each brand

are a combination of these two extremes. That is, a

portion

of sales is de-

rived from consumers who exhibit a brand

preference,

and the

remaining

portion

is attributed to the amount of

display space

allocated to the brand.

The

following

model of consumer behavior with

regard

to brands is based

upon

these

hypotheses.

The Model

If these identified

purchase patterns realistically

describe the consumer

buying

behavior that leads to total sales of a

product class, the model em-

bodying

these

hypotheses

can be used to obtain estimates of

(a)

the

per-

centage

of

buyers

who have a brand

preference, (b)

the

percentage

of these

buyers

who

prefer

each brand, and

(c)

the effect of

display-space

allocation

on sales of each brand. Let P be the

percentage

of all

buyers

who have

a

preference

for some brand and

Fi

be the

proportion

of those who have a

preference

for brand i. As a

percentage

of total

product sales, brand i sales

derived from those consumers who have a

preference

is P times

Fi.

Let

Si

be the

proportion

of total

product display space

allocated to brand i. Since

(100-P)

is the

percentage

of

buyers

who do not exhibit a brand

preference,

(100-P) percent

of total sales will be divided

among

the brands

according

to the

proportion

of total

display space

allocated to each brand. Thus,

as a

percentage

of total

product sales,

brand i sales attributable to those

buyers

without a brand

preference

are

(100-P)

times

Si.

Total brand i sales as a

percentage

of total

product

sales

(Yi)

are the sum of the two

components:

(1) Y,

=

PFi +

(100

-

P)Si.

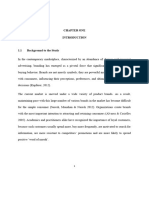

Figure

1 is a

graphic presentation

of this model for two brands

(X

and

Y)

and for P, Fx,

and F,

equal

to 50, 0.8, and 0.2, respectively.

If P=

100,

none of the total

product

sales will be attributable to

display space

alloca-

tion; conversely,

if

P=0,

all sales will be attributable to

display-space

allocation. In the latter situation, the line

representing

sales of brand X

would be drawn from the lower left to the

upper right

corner.

A feature of this model is that

Yi

is a linear function of

Si

and of the

parameters,

P and

Fi,

which can be written as

(2) Yi

=

a

+ bSi

where

b is the

percentage

of sales affected

by space allocation,

or 100

-

P,

and

a

=PFi.

726

MEASURING CONSUMER BRAND PREFERENCE

Percentage

of Proportion of Total Display Space Percentage of

Total Sales

(Brand Y)

Total Soles

(Brand X) (Brand Y)

I.0 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0

100

I I I I i I I I

Fixed

Sales,

Brand Y- PF,, 50 x 0.20-0.10.

90 10

Variable

Soles,

Brand Y 100

-

P)

Sy-50

S

80

-

20

70- -T

-

so

60- ,

>

40

50-

S50

.Varlable Sales,

Brand Xs 50

Sx

Fixed Soles, Brand X

PFx-50

x 0.80=40'

30- - 70

20 -

- 60

10- -90

0 I I I I I I I 1I 100

0 o.I 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1.0

Proportion of Totol Display Space

(Brand X)

Figure

1.

Hypothetical

model of the

relationship

between brand sales

and the

proportion

of

display space

allocated to brands

Consequently,

since a and b can be estimated from observed sets of

values

(Yi, Si) by

the

least-squares method, the

parameters,

P and

Fi,

can

be estimated.

Under this

model, there are two basic

assumptions

about consumer

buy-

ing

behavior. First, it is assumed that some

buyers

have a brand

preference,

that

they purchase

on the basis of this

preference,

and that the

percentage

of

display space

allocated to a brand will not affect their

purchases. Second,

it is assumed that all other

buyers

have no brand

preferences

and that their

brand

purchases vary directly

with the

percentage

of

display space

allocated

to each brand. Standard statistical

concepts

can be used to measure

and/or

test the

validity

of these

assumptions.

A test of the null

hypothesis

that the

slope, b,

of the

regression

function fitted to

equation (2)

is less than or

equal

to zero is

equivalent

to

testing

the

hypothesis

that

P, the

percentage

of

buyers

who have a

preference

for some brand, is

greater

than or

equal

to

100.

Further,

a test of the null

hypothesis

that the

intercept, a, of

equation

(2)

is zero is a test of the

hypothesis

that brand sales made to those

buyers

with some brand

preference

are zero.

At least two brands must be

present

in the

display

if these estimates are

to be obtained. This

places

some limits on the relevant

range through

which

observations can be taken. For

example,

if

eight frontages

are devoted to

the

product

class under

study,

the smallest

possible space

allocation is

0.125. While

space

allocations of 0 or 1 have no

meaning

with the model,

the basic

parameters

of consumer behavior can be estimated within the

727

728 D. I.

PADBERG,

F. E. WALKE, AND K. W. KEPNER

range

of

space

allocations which

permit

a consumer choice between brands.

In

regression analysis,

the coefficient of determination

(r2)

is used as a

conventional measure of the

degree

of

relationship

between the

dependent

and

independent

variables. Even

though

the

slope

(b=100-P)

may

be

zero, this model

may

still

support

valid inferences

concerning

brand-

preference

behavior. That is, when P

equals 100, all sales of a brand are

made to

buyers

who have some brand

preference.

The

regression

line in this

instance is horizontal and r2

goes

to zero. Therefore, for the cases in which P

approaches 100, the coefficient of determination is not an

appropriate

mea-

sure of the

reliability

of the model. The measure which will be used is

Q,

a transformation of the standard error of the estimate.

If observations of the intersections of S, and

Yi

were

completely

random

in

nature, the mean of

Yi

would be 50 and

S,j,

would be 34.14. This ran-

dom

type

of behavior is identified in the index

Q

as a zero fit. On the other

hand,

a

perfect

fit would be identified as the

limiting

case where

S,sj

goes

to zero. The

following

transformation of

Sy,ii

sets

up

the index

Q

as a mea-

sure of fit in which a

perfect

fit is identified as 100 and no fit is identified

as zero:

(3)

Q

=

100

-

(2.93,Sv,,).

This measure is useful in

going beyond

r2. It

separates

the case in which

the data conform

closely

to the model with a zero b value from the random

behavior case-both of which would have zero r2 values.

The model

presented

has been

developed

to isolate and

quantify

the

manner in which consumers' brand

preferences

affect

purchase

choices. To

this

point

in the

analysis, price

does not influence the outcome because the

price

of each

competing

brand is assumed to be the same. A

question

of

paramount importance, however, is,

To what extent do these observed

brand

preferences

neutralize or

compensate

for

price

differences? For ex-

ample,

Bain's definition of

product

differentiation as an

entry

barrier in-

volves the

concept

of a difference in

price by

which the established com-

petitor may

sell above

production

costs due to

product

differentiation with-

out

incurring

the

entry

of

potential competition [1, p. 239].

This definition

has been useful as a

concept; however,

it has not been

operational.

It is

possible

to

get

some

empirical

measure of the effect of

price

relative

to brand

preference by

use of the model

given

here. For

example,

if

prices

of brand

pairs

are made

equal,

a measure of the effect of brand

preference

alone

may

be obtained. The effect of

price

differentials with the same brand

pairs

can next be

analyzed.

This

process

allows measurement of the effect

upon

consumers'

purchasing

habits and choices of the two influences com-

bined-brand

preferences

and

price

differentials.

By comparing

the results

of brand

preferences

alone to the results of brand

preferences

combined

with

price differentials,

we can see some indication of their relative im-

portance.

MEASURING CONSUMER BRAND PREFERENCE

Empirical Analysis

Data were obtained in a

large metropolitan

market on the sales of

various

pairs

of fluid milk brands from

supermarkets

with

varying display-

space allocations, under conditions of controlled brand

prices

and

quality

of

display space

and no

point-of-sale advertising

or

promotion.3

The dis-

tribution of fluid milk in the market is dominated

by

sales

through

retail

food

stores;

brand

competition

within stores is

primarily

between a manu-

facturer brand and its

corresponding

distributor brand.4 In each instance

where distributor and manufacturer brands were in

competition,

the dis-

tributor brand was

priced

a few cents

per

unit below the manufacturer

brand.

For this

analysis,

four

pairs

of brands were observed, selling

from six

retail food stores.5 One brand which was advertised

nationally

was common

to each

pair.

In two

instances, the sales of one

pair

of brands were observed

in two

supermarkets,

one located in a

relatively high

and the other in a

relatively

low income area. In

addition, the sales of one

pair

of brands were

observed under two sets of conditions:

one,

a

price

differential of two cents

per

half

gallon

between

brands,

and the

other, equal

brand

prices.

Sales of

another

pair

of brands were observed in

varying types

and sizes of container:

glass

half

gallons, paper

half

gallons,

and

glass gallons.

These combinations

yielded

12

separate

series of data

by

which brand sales could be related

to the

proportion

of

display space

allocated to each brand. The data were

then used to test the

brand-preference

model. The results are summarized

in Table 1. Measures of statistical

reliability

are included. In the two cases

for which the coefficient of determination was small, the index

Q

of the

standard error of estimate was

high, indicating

that the data fitted the

model

closely.

In

general,

the values for r2 were

high

(with

the

exception

of

the two cases with

price differences),

and the values of

Q

were all

high.

This

suggests

that the

reliability

of the model for

explaining

observed values

is

very good.

The model

generally

indicated that when there were no

price

differences

between brands,

40 to 55

percent

of fluid milk

buyers

had a definite brand

preference.

Of this

group,

80 to 100

percent preferred

the

nationally

ad-

3

Display space

variations were measured in terms of the

proportion of the total

display

area that was allocated to each brand. The total

display

area allocated to fluid milk was held

constant in each store. The

quality

of

display space

was controlled

by rotating

the

position

(in terms of store traffic

flow)

of each brand in the

dairy case. Each

sample

which served as the

basis for one sales observation consisted of the sale of 100

quart-equivalent

units of fluid milk.

4

"Manufacturer brand and its

corresponding distributor brand" indicates that the milk

is

processed and

packaged by the same firm for both brands.

5

This

analysis

relates to a market environment

involving only two competing

brands. In

this

case, the

parameters

for Brand A are estimated and the other brand is residual. The

model is

equally applicable

to situations where several brands are in competition.

729

Table 1. Estimated

brand-preference parameters

of fluid milk

buyers

in an Ohio

metropolitan

area

Proportion

of

Percentage of

Percentage of

Percentage of buyers with pref- prnd A

based

buyers basing Statistical

reliability

coefficientsb

buyers with erences that pre- r e purchases on dis-

preferences

fer Brand A - on

prefe1rc

r

play exposurea

(P) (Fa) (PFcol.

2)

(100-P) 2

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Brands A & B

Equal price

High-income area 40.9 .822 33.6 59.1** 74.7 .643

Low-income area 38.6 .845 32.6 61.4** 82.8 .808

Price differences

High-income area 102.0 .399 40.7 -2.0 95.3 .088

Low-income area 97.3 .283 27.5 2.7 93.2 .065

Brands A & C 54.0 .975 52.7 46.0** 91.4 .939

Brands A & D 56.6 1.028 58.1 43.5** 89.6 .767

Brands A & E

High-income

area

Paper half gallon 58.8 .742 43.6 41.2** 91.8 .958

Glass half gallon 53.6 .808 43.3 46.4** 88.0 .928

Glass gallon 44.3 .889 39.4 55.7** 63.5 .551

Low-income area

Paper half gallon 46.6 .936 43.4 53.6** 87.2 .929

Glass half gallon 16.4 1.430 23.5 83.6** 93.5 .937

Glass gallon

31.0 .849 26.3 69.0** 85.2 .903

a

In testing the hypothesis that

(100- P)

<0,

*

indicates statistical

significance at

5%

level,

**

at

1%

level.

b

Q

is a transformation of the standard error of estimate into an index where 100

represents

a

perfect

fit and zero represents random be-

havior.

c0

)I'd

t

td

m

1.8

171

m

t',

0

41.

t4

t

pq

MEASURING CONSUMER BRAND PREFERENCE

vertised manufacturer's

brand,

Brand A. These estimates seem reasonable

and consistent in the

light

of market observations of and

experience

with

the distribution of fluid milk.

Only

one

exception

to these reasonable

brand-preference parameters

was noted. For the

comparison

of

glass

half

gallons

between Brands A and

E in the low-income

area, the model indicated that a

relatively

small

por-

tion, 16

percent,

of the fluid milk

buyers

had a brand

preference,

but that

of those with a

preference,

143

percent preferred

Brand A. An examination

of the actual

space

and sales data indicated the cause of the unreasonable

estimate. At one

space allocation, the sales of Brand A were

greater

than

one would

anticipate

on the basis of the sales at the other three

space

allocations. This set of

atypical

observations increased the

slope

of the

regression line, which then resulted in an underestimate of the

proportion

of

buyers

that had a brand

preference

and a

corresponding

overestimate

of the

proportion

with a brand

preference

that

preferred

Brand A. It is not

clear whether this

atypical

behavior was caused

by

some external influence

or resulted from an error in

recording.

Since all other estimates of

parame-

ters were within tolerances

explainable by sampling error, this

unexplained

purchase

behavior was not considered as a serious malfunction of the model.

This

analysis displays

some

interesting

observations

concerning

the rela-

tionship

between consumer

preferences

and

price

differentials as a motiva-

tion of consumer

purchases.

In the

analysis

of Brands A and

B, it can be

noted that about 60

percent

of the sales of both brands result from

display

exposure

in both

high-income

and low-income situations when

prices

were

equal.

Of the sales of Brand

A, about 32 to 34

percent

of the

consuming

population

based their

purchases

on a brand

preference.

When a

price

dif-

ferential was

imposed,

the share of the

population purchasing

Brand A

based on

preference

became smaller in low-income areas and increased in

high-income

areas. The

major effect, however, upon

Brand A of a

price

differential in favor of the

competing

distributor brand was that all of the

sales which had been made at random on the basis of

display exposure

were

lost to Brand B. This

implies

that a

completely

unknown

brand, if sold at a

lower

price,

could

expect

substantial sales if it were

displayed

in a

high

proportion

of the total

product display

area. This

may explain the rapid

and

widespread acceptance

of distributor-branded milk and other

products.

The

pattern

of consumer

preference by

income seems to be a rather

complex

one. In five

comparisons

made between

high-income

and low-

income

areas, the

percentage

of consumers with a

preference for some brand

was

always higher

in the

high-income

area. On the other hand, among

these

preference-motivated customers, the

proportion

with

allegiance to the

nationally

advertised brand was

highest

in low-income areas in four of five

cases. Where both of these factors were taken into

account, the share of the

milk

purchases motivated

by preference for the national brand was

slightly

731

D. I.

PADBERG,

F. E.

WALKER,

AND K. W. KEPNER

higher

in the

high-income

areas. It was

markedly higher

in the

high-income

areas when the

price

difference was

against

the national brand.

This

suggests

that

many high-income

families

purchase the local brand

at

equal prices

while

preference

for the national brand increases where it is

sold at a

premium.

Because the milk of different brands is of

comparable

quality,

this behavior

may

be

explained by

snob

appeal.

Comparisons

available between

glass

and

paper

containers and their

effects on consumer

preferences

indicate that

generally

consumer

pref-

erences are

stronger

for

paper

containers. In both the

high-income

and low-

income areas, the

proportions

of sales motivated

by display exposure

was

higher

for both

types

of

glass

containers than for

paper

containers.

Implications

The estimation of the two brand-preference parameters, P and F, by the

model described here has

many implications,

from the

standpoint

both of

public policy

and of the individual firm. The

importance

of brand

pref-

erences and

product

differentiation in

general

or from an

industry perspec-

tive

depends

on the

percentage

of consumers who are motivated

by

brand

preferences

in their

purchase

decisions. The individual firm is most in-

terested in the

preference

of consumers for its own brand.

The

promotion budgets

of

competitors

at both the

processor

and the re-

tail levels of the food distribution

system

are extensive and

increasing

in

size. For the most

part,

advertisers make these

expenditures

without

enough

information about the

expected

effect. If it is

possible by

use of this model

to determine what

proportion

of the

consuming population

is brand con-

scious and of this

group

what

proportion

have

preferences

for various

brands,

it

may

be

possible

to

identify

the

selling problem

more

accurately

and to conduct more effective

promotion campaigns.

Some

types

of

promo-

tional

activity may

affect the indifferent consumers while other

types

re-

arrange

the

preferences

of brand-conscious consumers. This model

may

be

instrumental in

producing

a better

understanding

of

advertising

and

pro-

motion

response

in

general.

These results also have

implications

for retail food distributors. For ex-

ample,

if a substantial

portion

of the fluid milk

buyers

that

patronize

a re-

tail food firm are indifferent to

brands,

it would be

easy

to

gain

consumer

acceptance

of a distributor-controlled brand. However, the elimination of

all manufacturer brands

might

cause considerable consumer dissatisfaction

if a

relatively large proportion

of the

buyers

of a

product

class have a

definite brand

preference.

Policy

makers should find

knowledge

of these

preference parameters

for

a

large

number of

product

classes

very

useful in

understanding present

competitive

behavior and in

anticipating

future

developments

in the food

distribution

system.

This is

especially

true since the nature of

competition

732

MEASURING CONSUMER BRAND PRI';K:iNCE

between food

processors

and retailers as well as the future structure of the

food distribution

system

will be determined

by

the

processors' ability

to

maintain established and

preferred

brands.

Although

this model has been used

only

on a

pilot

basis and with

only

one

product class,

it seems to offer a

relatively inexpensive

and accurate

method of

finding

out about consumer

food-purchase

motivations. Theoreti-

cally,

the model is

applicable

to

any product

sold in retail stores where

more than one brand is

displayed. Practically, however, the model

may

be

more

adaptable

to some

product

classes than to others. The

products

to

which the model is best

adapted

are

probably

those with

(1)

relatively

large

sales volume

per

unit and

high turnover,

(2)

relatively large display

frontage,

and

(3)

relatively

little difference in the established

prices among

brands.

References

[1] BmN,

J. S., Industrial

Organization, New York, John Wiley

& Sons, Inc., 1959.

[2]

National Commission on Food

Marketing, Special

Studies in Food Marketing, Tech.

Study 10, Washington,

D.

C., U.S. Government

Printing Office, June 1966.

[3] PADBERG, D. I., "The

Space-Sales

Ratio as a Measure of Product Differentiation,"

J. Farm Econ. 46:173-178, Feb. 1964.

[4] SUDMAN, SEYMOUR, "On the

Accuracy of Recording of Consumer Panels: I," J.

Mktg.

Res.

1(2):

14-20, May 1964.

[5] , "On the

Accuracy

of

Recording

of Consumer Panels: II," J.

Mktg.

Res. 1(3):

69-83, Aug.

1964.

[6] TUCKER, W. T. "The

Development of Brand

Loyalty," J.

Mktg.

Res.

1(3):32-35,

Aug

1964.

733

Вам также может понравиться

- Research Methodology: Chapter # 4Документ33 страницыResearch Methodology: Chapter # 4DDO Division-2Оценок пока нет

- To Identify The Drivers of Customer Loyalty in Apparel StoresДокумент32 страницыTo Identify The Drivers of Customer Loyalty in Apparel Storespgp28289Оценок пока нет

- Marketing ResearchДокумент11 страницMarketing ResearchgoudarameshvОценок пока нет

- MARKETINHДокумент19 страницMARKETINHRashi HoraОценок пока нет

- Nafisat Research Paper On MarketingДокумент87 страницNafisat Research Paper On MarketingDavid MichaelsОценок пока нет

- CB On Wires and CablesДокумент96 страницCB On Wires and Cablesjaspreet100% (2)

- MK0011 Consumer Behavior Fall 10 SolvedДокумент27 страницMK0011 Consumer Behavior Fall 10 SolvedDeep Dhar100% (1)

- An Introduction To Consumer BehaviorДокумент11 страницAn Introduction To Consumer BehaviorKuldeep SharmaОценок пока нет

- Research Paper On Conversion of FootfallДокумент11 страницResearch Paper On Conversion of FootfallAbu BasharОценок пока нет

- IJCRT2104451Документ16 страницIJCRT2104451Abinash MОценок пока нет

- Customer. ProjectДокумент5 страницCustomer. ProjectRazinОценок пока нет

- Perspectives On Consumer Behavior: Phd.C. Bahman HuseynliДокумент43 страницыPerspectives On Consumer Behavior: Phd.C. Bahman HuseynlisamaОценок пока нет

- Surf Excel 31-10-2015Документ50 страницSurf Excel 31-10-2015Pradnya ShettyОценок пока нет

- Literature Review For Consumer PerceptionДокумент10 страницLiterature Review For Consumer PerceptionArun Girish50% (4)

- A Two Dimensional Concept of Brand LoyaltyДокумент6 страницA Two Dimensional Concept of Brand LoyaltyHamida Kher60% (5)

- A Comparative Study of Various TV Brands in Context of Customer Awareness and Preference'Документ6 страницA Comparative Study of Various TV Brands in Context of Customer Awareness and Preference'Ambresh Pratap SinghОценок пока нет

- Review of Literature: Paulins & Geistfeld (2003), Consumer Perceptions of Retail Store Attributes For A Set ofДокумент8 страницReview of Literature: Paulins & Geistfeld (2003), Consumer Perceptions of Retail Store Attributes For A Set ofDeepa SelvamОценок пока нет

- Thesis On Consumer Purchase IntentionДокумент4 страницыThesis On Consumer Purchase IntentionBestCustomPapersShreveport100% (2)

- How Information Changes Consumer Behavior and How Consumer Behavior Determines Corporate StrategyДокумент29 страницHow Information Changes Consumer Behavior and How Consumer Behavior Determines Corporate StrategyArif FurqonОценок пока нет

- FACTOR INFLUENCING CONSUMER BUYING BEHAVIOUR WITH SPECIAL REFERENCETO DAIRY PRODUCTS Ijariie6805 PDFДокумент5 страницFACTOR INFLUENCING CONSUMER BUYING BEHAVIOUR WITH SPECIAL REFERENCETO DAIRY PRODUCTS Ijariie6805 PDFkshemaОценок пока нет

- Literature Review in Consumer Buying BehaviourДокумент7 страницLiterature Review in Consumer Buying Behaviourfut0mipujeg3100% (1)

- Literature Review: Kotler and Armstrong (2001)Документ15 страницLiterature Review: Kotler and Armstrong (2001)ajaysoni01Оценок пока нет

- Questionnaire Sales PromotionДокумент13 страницQuestionnaire Sales Promotionthinckollam67% (3)

- Identifying The Deal Prone Segment: IV. Substantive Findings and ApplicationsДокумент10 страницIdentifying The Deal Prone Segment: IV. Substantive Findings and ApplicationsPrashant KhatriОценок пока нет

- Consumer BehaviourДокумент46 страницConsumer BehaviourGaurav AgrawalОценок пока нет

- Abhishek Kumar 2021-2023... 14905021036Документ8 страницAbhishek Kumar 2021-2023... 14905021036Abhishek KumarОценок пока нет

- SMU A S: Consumer BehaviourДокумент32 страницыSMU A S: Consumer BehaviourGYANENDRA KUMAR MISHRAОценок пока нет

- Literature Review: Kotler and Armstrong (2001)Документ23 страницыLiterature Review: Kotler and Armstrong (2001)Anuj LamoriaОценок пока нет

- Disserr LitraДокумент17 страницDisserr LitraDisha GangwaniОценок пока нет

- Azad - Front PagesДокумент2 страницыAzad - Front PagesshashikanthОценок пока нет

- Untitled DocumentДокумент12 страницUntitled DocumentAISHWARYA MADDAMSETTYОценок пока нет

- Consumer Buying Behaviour Research PaperДокумент8 страницConsumer Buying Behaviour Research Paperfkqdnlbkf100% (1)

- Discount ImpactДокумент7 страницDiscount Impactpriyanshuv94277Оценок пока нет

- Demand EstimationДокумент3 страницыDemand EstimationMian UsmanОценок пока нет

- Literature Review On Buying DecisionДокумент5 страницLiterature Review On Buying Decisionc5r9j6zj100% (1)

- Literature Review On A Study of Retail Store Attributes Affecting The Consumer PerceptionДокумент11 страницLiterature Review On A Study of Retail Store Attributes Affecting The Consumer PerceptionSampangi Kiran50% (2)

- Research Paper On Consumer Buying BehaviourДокумент6 страницResearch Paper On Consumer Buying Behaviouregx2asvt100% (1)

- Buying Perception of FMCG Consumers - of Soaps and Detergents Products in Mysore District" - A Study at MallsДокумент14 страницBuying Perception of FMCG Consumers - of Soaps and Detergents Products in Mysore District" - A Study at MallsarcherselevatorsОценок пока нет

- What Customers Want TomorrowДокумент3 страницыWhat Customers Want TomorrowHenrique SartoriОценок пока нет

- An Extended Model of Behavioural Process in Consumer Decision MakingДокумент7 страницAn Extended Model of Behavioural Process in Consumer Decision MakingRitika SablokОценок пока нет

- Research On Factors Affecting Consumers PurchaseДокумент6 страницResearch On Factors Affecting Consumers Purchasetrúc vy nguyễnОценок пока нет

- CH 3Документ30 страницCH 3Youssef AymanОценок пока нет

- Consumer BehaviourДокумент68 страницConsumer Behaviourrenu90100% (1)

- Beyond Market SegmentationДокумент4 страницыBeyond Market Segmentationvikas joshiОценок пока нет

- A Study On Factors Influencing Youth's Buying Behavior Towards SoapsДокумент8 страницA Study On Factors Influencing Youth's Buying Behavior Towards SoapsTrung cấp Phương NamОценок пока нет

- CBNM JuryДокумент15 страницCBNM JuryCHAITRALI DHANANJAY KETKARОценок пока нет

- UntitledДокумент35 страницUntitledVikesh PunaОценок пока нет

- Imapct of Branding On Consumer Buying BehaviorДокумент27 страницImapct of Branding On Consumer Buying BehaviorPareshRaut100% (1)

- Consumer Behaviour Towards Foods and ChipsДокумент41 страницаConsumer Behaviour Towards Foods and ChipsRaj Singh100% (1)

- The Role of Consumer Behaviour in Present Marketing Management ScenarioДокумент11 страницThe Role of Consumer Behaviour in Present Marketing Management ScenariojohnsonОценок пока нет

- Consumer Behaviour: Consumer Behaviour Is The Study of Individuals, Groups, or Organizations and The ProcessesДокумент6 страницConsumer Behaviour: Consumer Behaviour Is The Study of Individuals, Groups, or Organizations and The ProcessesViswaprakash IjkОценок пока нет

- A Study On The Brand Choice Decisions of Consumers With Reference To CosmeticsДокумент5 страницA Study On The Brand Choice Decisions of Consumers With Reference To Cosmeticskuhely hossainОценок пока нет

- Institute of Management (Nirma University) Mba-Ft Marketing Management Group Assignment 2.0 "Consumer Behaviour"Документ20 страницInstitute of Management (Nirma University) Mba-Ft Marketing Management Group Assignment 2.0 "Consumer Behaviour"aakashchavdaОценок пока нет

- Customer Analysis & Insight: An Introductory Guide To Understanding Your AudienceОт EverandCustomer Analysis & Insight: An Introductory Guide To Understanding Your AudienceОценок пока нет

- SWOT Analysis of Meezan BankДокумент10 страницSWOT Analysis of Meezan Banksufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Mission and VisionДокумент2 страницыMission and VisionmahibuttОценок пока нет

- M.a.D's SWOT Analysis of Meezan Bank!Документ10 страницM.a.D's SWOT Analysis of Meezan Bank!Muhammad Ali DanishОценок пока нет

- 1947Документ8 страниц1947sufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Notes For Microsoft WordДокумент3 страницыNotes For Microsoft WordKaran KumarОценок пока нет

- Profit and Loss Account: Net Spread Earned 10,645 10,452 9,366Документ8 страницProfit and Loss Account: Net Spread Earned 10,645 10,452 9,366sufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Profit and Loss Account: Net Spread Earned 10,645 10,452 9,366Документ8 страницProfit and Loss Account: Net Spread Earned 10,645 10,452 9,366sufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Ingredients: Buy These Ingredients NowДокумент1 страницаIngredients: Buy These Ingredients Nowsufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- BCRWДокумент56 страницBCRWsufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- 1947Документ8 страниц1947sufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Labo Par Uske Kabhi Baddua Nahi HotiДокумент2 страницыLabo Par Uske Kabhi Baddua Nahi Hotisufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Labo Par Uske Kabhi Baddua Nahi HotiДокумент2 страницыLabo Par Uske Kabhi Baddua Nahi Hotisufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- What Is The Distinction Between Auditing and AccountingДокумент1 страницаWhat Is The Distinction Between Auditing and Accountingsufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Business Law Guess Papers 2014 BДокумент2 страницыBusiness Law Guess Papers 2014 Bsufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Relationship Between Education and Economic Growth in Pakistan: A Time Series AnalysisДокумент6 страницRelationship Between Education and Economic Growth in Pakistan: A Time Series AnalysisSmile AliОценок пока нет

- Economics of Pakistan Guess Papers 2015 BДокумент6 страницEconomics of Pakistan Guess Papers 2015 Bsufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- 2Документ39 страниц2Neeraj TiwariОценок пока нет

- Hu 1032 Principles of Investiga TonДокумент4 страницыHu 1032 Principles of Investiga Tonsufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Audit Working Papers What Are Working Papers?Документ8 страницAudit Working Papers What Are Working Papers?sufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Random ExperimentДокумент4 страницыRandom Experimentsufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Relationship Between Education and Economic Growth in Pakistan: A Time Series AnalysisДокумент6 страницRelationship Between Education and Economic Growth in Pakistan: A Time Series AnalysisSmile AliОценок пока нет

- Muhammad Tayyab Graphics Designer: Address: Muhalla Bakhtay Wala Gala Gulam Muhammad Thaikadar Wala Street # 1 House # 2Документ2 страницыMuhammad Tayyab Graphics Designer: Address: Muhalla Bakhtay Wala Gala Gulam Muhammad Thaikadar Wala Street # 1 House # 2sufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Principles of Economics IДокумент2 страницыPrinciples of Economics Isufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- ConclusionДокумент1 страницаConclusionsufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Labour EconomicsДокумент29 страницLabour EconomicsAniketh Anchan100% (1)

- Principles of Banking IДокумент2 страницыPrinciples of Banking Isufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Introduction To Business Guess Papers 2014 BДокумент1 страницаIntroduction To Business Guess Papers 2014 Bsufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- MBFДокумент1 страницаMBFsufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- MBFДокумент1 страницаMBFsufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- TaleemДокумент46 страницTaleemsufyanbutt007Оценок пока нет

- Retail Management Information SystemДокумент12 страницRetail Management Information Systemmittalsakshi020692Оценок пока нет

- Elasticity of DemandДокумент28 страницElasticity of Demandshweta3547Оценок пока нет

- HRD PPT G-3Документ18 страницHRD PPT G-3Niharika SumanОценок пока нет

- 11 Project LipistikДокумент44 страницы11 Project LipistikKing Nitin AgnihotriОценок пока нет

- SDCVДокумент6 страницSDCVKrishnadeep GuptaОценок пока нет

- Territory ManagementДокумент4 страницыTerritory Managementnory_mendozaОценок пока нет

- Tiffin Talks Deck-AltДокумент14 страницTiffin Talks Deck-AltPAWAN HORAОценок пока нет

- Dental Practice Training With Tracy StuartДокумент2 страницыDental Practice Training With Tracy StuartChris BarrowОценок пока нет

- Bahrain 6.00 YrsДокумент14 страницBahrain 6.00 YrsNHNОценок пока нет

- Assignment 1 - Transforming Corner-Office Strategy Into Front Line Action - CS&O - FinalДокумент6 страницAssignment 1 - Transforming Corner-Office Strategy Into Front Line Action - CS&O - FinalAnurag SukhijaОценок пока нет

- Samsung Witness ListДокумент17 страницSamsung Witness ListMikey CampbellОценок пока нет

- Individual Assignment 4: Competitive AnalysisДокумент5 страницIndividual Assignment 4: Competitive AnalysisStephanie SargentoОценок пока нет

- GIO+Course 3 Email Marketing Tahir AshrafДокумент17 страницGIO+Course 3 Email Marketing Tahir AshrafSayed tahir Ashraf100% (1)

- Project Report On "Symphony Air Cooler"Документ47 страницProject Report On "Symphony Air Cooler"Ronak Jain100% (1)

- Mario Stifano Graphic Designer CVДокумент1 страницаMario Stifano Graphic Designer CVmariostifanoОценок пока нет

- Basic Rights of A ConsumerДокумент3 страницыBasic Rights of A ConsumerCameron Castro100% (1)

- Unit 2 Marketing EssentialsДокумент10 страницUnit 2 Marketing EssentialsUsamaОценок пока нет

- Make Trip: Mem RiesДокумент28 страницMake Trip: Mem RiesShikha Trehan0% (1)

- Kelloggs PromotionДокумент4 страницыKelloggs PromotionWint Wah HlaingОценок пока нет

- TeachRetail ChapterTeachingNoteДокумент45 страницTeachRetail ChapterTeachingNoteThanh Nguyen VanОценок пока нет

- Buildchamp Construction Company (BCC)Документ26 страницBuildchamp Construction Company (BCC)Ikram100% (1)

- The Entrepreneur'S Playbook: by Ted LiebowitzДокумент200 страницThe Entrepreneur'S Playbook: by Ted Liebowitzssrao10Оценок пока нет

- Business Plan RulesДокумент2 страницыBusiness Plan RulesHinu Abid100% (1)

- 2013 The American Mold Builder - SummerДокумент48 страниц2013 The American Mold Builder - SummerAMBAОценок пока нет

- Digital Capability Framework Overview 3Документ9 страницDigital Capability Framework Overview 3Kieran O'HeaОценок пока нет

- Retail Cosmetics SephoraДокумент25 страницRetail Cosmetics Sephoraagga11110% (1)

- City of Birmingham Micro Transit Pilot RFPДокумент15 страницCity of Birmingham Micro Transit Pilot RFPRoy S. JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Curriculum - Vitae: WWW - Staples.inДокумент5 страницCurriculum - Vitae: WWW - Staples.inPradeep ShindeОценок пока нет

- The Marketing Environment PDFДокумент3 страницыThe Marketing Environment PDFzzkhanhОценок пока нет

- Hola Film Festival General ProposalДокумент6 страницHola Film Festival General ProposalMarcia Salazar0% (1)