Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

AHA Hypertension Journal

Загружено:

Tiwi Qira0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

64 просмотров10 страницjurnal kedokteran

Оригинальное название

AHA Hypertension journal

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документjurnal kedokteran

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

64 просмотров10 страницAHA Hypertension Journal

Загружено:

Tiwi Qirajurnal kedokteran

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 10

the NHLBI Working Group

Management of patient compliance in the treatment of hypertension. Report of

ISSN: 1524-4563

Copyright 1982 American Heart Association. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0194-911X. Online

72514

Hypertension is published by the American Heart Association. 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX

doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.4.3.415

1982, 4:415-423 Hypertension

http://hyper.ahajournals.org/content/4/3/415

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

http://www.lww.com/reprints

Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at

journalpermissions@lww.com

Fax: 410-528-8550. E-mail:

Kluwer Health, 351 West Camden Street, Baltimore, MD 21202-2436. Phone: 410-528-4050.

Permissions: Permissions & Rights Desk, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a division of Wolters

http://hyper.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/

Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Hypertension is online at

by guest on May 12, 2012 http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ Downloaded from

Management of Patient Compliance in the

Treatment of Hypertension

Report of the NHLBI Working Group

R. BRIAN HAYNES, M.D., PH.D., Working Group Chairman

McMaster University Faculty of Health Sciences, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

MARGARET E. MATTSON, PH.D., Executive Secretary;

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda,

Maryland.

ARAM V. CHOBANIAN, M.D., Boston University Medical

School, Boston, Massachusetts

JACQUELINE M. DUNBAR, R.N., PH.D., Stanford Univer-

sity School of Medicine, Stanford, California

TILMER O. ENGEBRETSON JR., National Heart, Lung

and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland

THOMAS F. GARRITY, PH.D., University of Kentucky Col-

lege of Medicine, Lexington, Kentucky

HOWARD LEVENTHAL, PH.D., University of Wisconsin,

Department of Psychology, Madison, Wisconsin

ROBERT J. LEVINE, M.D., Yale University School of

Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut

RONA L. LEVY, M.S.W., PH.D., M.P.H., University of

Washington School of Social Work, Seattle, Washington

SUMMARY Low patient cooperation erodes many of the proven benefits of antihypertensive therapy. Over

the last few years, there have been important advances in our understanding of the nature and management of

patient compliance in hypertension and other chronic illnesses. In this article we review the theoretical founda-

tion of compliance behavior; methods of measuring compliance; established and promising approaches to

managing compliance; ethical considerations in measuring, improving, and researching compliance; the cur-

rent state of implementation of compliance techniques in practice settings; and the efforts to disseminate infor-

mation on compliance through undergraduate and continuing health professional education programs.

(Hypertension 4: 415-423, 1982)

K E Y WORD S patient compliance compliance measurement public health education ethics

T

HE benefits of antihypertensive therapy have

been well documented in both selected popu-

lations

1

'

2

and the general community.

8

However, demonstrations of the efficacy of blood

pressure lowering required circumventing patient

compliance as a problem by disqualifying non-

compliers from entering the study

4

or utilizing extra-

ordinary measures to improve compliance that would

be difficult to apply en block in the usual delivery of

medical care.

8

This review was prepared by an ad hoc committee appointed and

supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, United

States Department of Health and Human Services. The views ex-

pressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect

those of the Institute or the Department.

Address for reprints: M.E. Mattson, Ph.D ., Clinical Trials

Branch, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Federal Build-

ing Room 216,7550 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda, Maryland 20205.

Received August 7, 1981; revision accepted October 22, 1981.

Under common conditions of medical practice, the

extent to which low patient compliance undermines

the effectiveness of antihypertensive therapy is truly

staggering.

6

At each step from detection through long-

term follow-up, large numbers of patients fall out of

care: up to 50% fail to follow through with referral ad-

vice;

8

'

7

over 50% of those who begin treatment drop

out of care within 1 year;

7

"

9

and only about two-thirds

of those who stay under care consume enough of their

prescribed medication to achieve adequate blood pres-

sure reduction.

10

'

n

It is no wonder that studies have

repeatedly shown that only 20% to 30% of individuals

who know themselves to be hypertensive are under

good control.

12

'

1S

Achieving and maintaining high

compliance with antihypertensive therapy thus present

challenges that must be met if we are to realize the

benefits of modern medical therapy for high blood

pressure.

415

by guest on May 12, 2012 http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ Downloaded from

416 HYPERTENSION VOL 4, No 3, MAY-JUNE 1982

OUTLINE

Definition of Compliance

Theories of Compliance Behavior

Historical Background

Educational Model

Health Belief Model

Emotional Drive Model

Behavioral Learning Model

Self-Regulation Model

Measuring Compliance

Monitoring Attendance

Clinical Judgment

Patient Self-Reports

Pill Counts

Drug Level Measurement

Biological Effects Assessment

Patient Reactivity

Improving Compliance

Screening Programs

Referral from Screening

Medication and Follow-Up

New Directions in Improving Compliance

Clinician-Patient Relationship

Social Support

Ethical Concerns in Applying Compliance Strategies

Utilization of Strategies to Increase Compliance

cides with medical advice.

14

Although this definition of

compliance is nonjudgmental, for many the term im-

plies patient sin and serfdom. Terms that can be used

synonymously include "adherence" and "default-

ing," with the former term having perhaps fewer

negative connotations.

Theories of Compliance Behavior

Historical Background

The study of compliance behavior holds fascina-

tion for those who wish to understand it (without

necessarily attempting to modify it) as well as those

who wish to modify it (without necessarily under-

standing it). Theory provides an organizational frame-

work through which research can be conducted in an

orderly fashion to satisfy both these perspectives.

Theories of compliance behavior have developed in

an expected fashion from simplistic to relatively

sophisticated. Early theories held that compliance was

related to easily tested characteristics of patients or

their social environments such as age, sex, marital

status, education, intelligence, religion, and socio-

economic status. Empirical testing of these "struc-

tural models" failed to reveal consistent relationships

between these variables and compliance, however.

16

Studies on "situational barriers," such as incon-

venient clinics and complex regimens, were somewhat

more fruitful but still failed to explain more than a

fraction of the compliance problems,

16

and it followed

that compliance was not much affected by simply

making treatments easier to follow and treatment

visits more convenient.

19

"

18

Because it has been only a decade since the first con-

vincing demonstration of the efficacy of antihyper-

tensive treatment,

1

-

2

it is hardly surprising that in-

novative approaches to improving patient acceptance

of this therapy are of recent vintage. Our understand-

ing of compliance and of ways to improve low compli-

ance has grown considerably during the last few

years.

14

This article is a concise summary of the

theory, research, ethics, and application of compliance

management methods in the treatment of hyper-

tension as viewed by an interdisciplinary group of

clinicians and researchers convened by the National

Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute for the purpose of

reviewing current developments in compliance

research.

Definition of Compliance

Compliance is the extent to which a person's be-

havior (in terms of keeping appointments, taking

medications, and executing life-style changes) coin-

Educational Model

A major theory of compliance behavior holds that

patients generally lack sufficient knowledge of their

illness and treatment to comply properly and that

thorough instruction will therefore result in better

compliance. This appears to have merit for short-term

treatments (less than 2 weeks in duration)

19

"

22

but has

very limited value for chronic disease regimens.

11

-

23

~

28

Health Belief Model

The health belief model

2

'

12S

is perhaps the com-

monest "motivational model" of compliance. Simply

stated, it holds that an individual's cooperation with

health advice depends upon the extent to which that

person perceives that he or she is susceptible to the dis-

ease, that the disease is serious, that the treatment is

efficacious, and that the barriers to compliance are

possible to overcome. A cue to action has also been

built into the model to account for the influence of ex-

ternal factors. Tests of the model show that it does

have predictive value for at least some preventive and

short-term therapeutic health actions

27

-

28

but that the

by guest on May 12, 2012 http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ Downloaded from

COMPLIANCE IN HYPERTENSION/AWLS/ Working Group 417

magnitude of its predictive value is modest at best.

29

"

81

Furthermore, communications that influence health

attitudes may have no observable effect on compli-

ance,

32

"

34

making the model of less interest from a

clinical perspective.

Emotional Drive Model

The emotional drive model is related to the health

belief and educational models in that it attempts to

achieve compliance through information about the ill-

ness to which is added some form of motivational

appeal. Generally, the motivating part of the message

seeks to arouse fear in the patient about dire conse-

quences of failing to comply. A graded effect on

behavior has sometimes been demonstrated, with

stronger threat messages effecting greater compli-

ance,

32

-

36

but other studies have shown no such grad-

ient.

33

'

3<i 3e

Most of the studies of this model have

been of once-only or short-term compliance; threats

and fear arousal appear to have little long-term in-

fluence.

37

'

38

Behavioral Learning Model

The behavioral learning model provides a more

powerful explanation of why people comply and how

compliance can be improved. Operant learning

theory, as originally developed by Skinner,

89

'

40

sug-

gests that behavior is solely the result of environ-

mental cues and rewards. More recently, cognitive

learning theory or social learning theory

41

'

42

has been

developed to account for the interaction of en-

vironmental events with a person's perception of

them. This model departs from operant learning

theory in two important ways. First, it holds that the

individual's interpretation of the environment deter-

mines what is reinforcing and what is not. Second, it

postulates that it is possible to teach someone when

and how to respond, without rewarding him or her for

performing the response, especially through "model-

ing" the behavior, that is, by having the person

observe someone execute the desired behavior. Thus,

both the person and his or her environment have an

important effect on a given behavior, with the person

perhaps holding the balance of power. Rather than

competing with the models described earlier, social

learning theory can be seen as a broad frame of

reference that encompasses them.

Self-Regulation Model

The final theoretical construct of relevance is that of

self-regulation. This model attempts to describe,

within the framework of social learning theory, the

role and method of acting of an individual when

presented with health advice. It comprises the follow-

ing components: 1) extracting information from the

environment; 2) generating a representation of the ill-

ness danger to oneself; 3) planning and acting, which

involves imagining response alternatives to deal with

the problem and taking selected actions to achieve

specific effects; and 4) monitoring how ones coping

reactions affect the problem and oneself.

43

"

45

At pres-

ent this model holds promise for both understanding

and modifying a person's compliance, but it has had

only preliminary empirical testing in the health

sphere.

Measuring Compliance

The efficient management of patient compliance

requires accurate and available methods of measure-

ment.

Monitoring Attendance

Because up to 50% of hypertensive patients simply

drop out of care within 1 year of its beginning,

7

'

9

monitoring attendance at appointments is critical.

This is not as obvious a technique as it sounds, as

many primary care practitioners do not make definite

follow-up appointments for their patients or fail to

note when patients miss appointments. Furthermore,

attendance at appointments is not a substitute for

medication compliance, as about one-third of pa-

tients who remain in care fail to follow the prescribed

treatment.

10

'

n

Clinical Judgment

The commonest method of assessing medication

compliance is probably clinical judgment. This is in-

tuitively attractive to clinicians and easily applied, but

it has been shown repeatedly that clinicians cannot

reliably predict the compliance of their patients

4650

even when they feel confident of their predictions.

46

-

60

Thus, clinicians should avoid depending upon their

subjective impressions in monitoring compliance.

Patient Self-Reports

When patients are asked directly about their

compliance they tend to overestimate the amount of

medication they are taking.

8168

However, about half

of noncompliant patients will admit to missing at least

some medication and the ease with which this infor-

mation can be obtained makes it very valuable. The

value of self-reports can be augmented by self-

monitoring through regular recording by the patient

or by special medication dispensers that perform this

task automatically.

64

' " Self-monitoring is one of the

few ways that one can determine the pattern of

medication consumption as distinguished from the

quantity consumed.

by guest on May 12, 2012 http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ Downloaded from

418 HYPERTENSION

VOL 4, No 3, MAY-JUNE 1982

Pill Counts

Pill counts provide a quantitative estimate of

compliance over a period of time. This method is

relatively reliable if performed at the patient's home

and with scrupulous attention to bookkeeping,

53

- "

ST

but these requirements make it largely impractical for

clinical settings. Although it has not been dem-

onstrated empirically, it is generally felt that pill

counts are unreliable when they are performed on pills

that patients bring with them to clinic visits non-

compliant patients may bring only some of their un-

used pills, or forget to bring their pills with them, or

fail to attend the appointment entirely. In general, the

pill count gives higher estimates of compliance than

biological assays"-" and lower compliance than

patient self-reports.

81

-

s3

'

M

Drug Level Measurement

Drug level determinations can be useful, partic-

ularly for drugs that have a sufficiently long half-life to

have minimal fluctuation in plasma concentration dur-

ing usual clinical dosing intervals. For example, digox-

in

s

and phenytoin

60

'

61

plasma levels can provide infor-

mation on compliance which can be used to guide

compliance interventions. However, their interpreta-

tion is subject to the foibles of individual variation in

drug absorption, metabolism, and excretion.

68

Further, drug level assessments are not routinely

available for antihypertensive drugs.

Biological Effects Assessment

In contrast to the direct measurement of drug

levels, the biologic effects of drugs have not been

found to correlate well with compliance. For example,

thiazide diuretics lower blood pressure and serum

potassium and raise serum uric acid; but none of these

effects provides as good an indication of compliance as

simply asking the patient.

83

Nevertheless, in clinical

practice it would improve efficiency to focus concern

about compliance on only those patients who fail to

achieve the therapeutic goal despite prescription of

usually adequate doses of treatment.

63

Patient Reactivity

All methods of assessing patient compliance are

susceptible to "reactivity." That is, if patients become

aware of the purpose of the assessment, they may alter

their compliance. Generally, one would expect any

change in compliance to be in a favorable direction,

and thus this is a potentially useful phenomenon

clinically. For research, it is clearly a hazard if the

purpose of the measurement is solely to document

rather than alter compliance.

While no single method of assessing compliance is

wholly satisfactory, many of the measures provide

more information than guessing and sequential com-

binations of the measures can minimize the amount of

effort required. For example, in routine patient care,

compliance need not be considered a problem unless

the patient fails to respond to usually adequate treat-

ment. When the treatment response is judged inade-

quate, the patient can be asked about compliance. If

the patient reports less than complete compliance, the

clinician can proceed with compliance interventions.

If the patient reports full compliance, problems with

the treatment itself can be considered along with

application of more sophisticated methods of measur-

ing compliance.

63

Improving Compliance

From the perspective of compliance, optimum

control of hypertension in the community will only be

achieved if four aims are met. First, screening

programs must gain the full cooperation of citizens;

second, referral from screening must be successful;

third, appointments for those in care must be attended

regularly; and finally, medication must be taken as

prescribed. These four steps require somewhat

different tactics, but research into compliance has

generated successful methods of dealing with each of

them. All of the following methods have been subjects

of controlled clinical trials unless otherwise stated.

Screening Programs

The yield of screening programs can be increased by

home visits, especially if executed outside usual work-

ing hours.

64

However, most screening programs reach

no more than 25% of the population,

7

-

M

and then only

for the duration of the program. Inasmuch as 70% of

the people visit a physician within a given year,

66

it

would seem logical to shift the site of hypertension

screening to the physician's office. Whether physi-

cians will take up this task, however, remains to be

seen.

Referral from Screening

The success of referral from screening can be aug-

mented by counseling

86

and by assisting patients to

make and keep appointments.

67

Although not

evaluated in controlled trials of compliance strategies

which would perhaps be unnecessary with the results

obtained, virtually complete referral success has been

achieved in two studies in which patients were

followed until at least one appointment had been

kept.

17

-

88

Medication and Follow-Up

Once the patient is under care for hypertension,

additional efforts are usually required to prevent the

by guest on May 12, 2012 http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ Downloaded from

COMPLIANCE IN HYPERTENSION//V7/Ifl/ Working Group

419

patient from dropping out of treatment and to pro-

mote full compliance with prescribed therapy. Unfor-

tunately, there does not appear to be as yet a single-

dose or single-modality cure for noncompliance.

Indeed, none of the following methods has improved

compliance when tested as the only intervention:

special learning packages

17

and pamphlets;

28

counsel-

ing about medication and compliance by a health

educator;

24

home visits;

88

increased convenience of

care at the worksite;

17

'

70

self-monitoring of blood

pressure;

6

"-

71

tangible rewards;

71

group discussions;

71

and counseling by nurses.

71

In contrast to the lack of effect of unimodal inter-

ventions, several controlled trials have shown

statistically and clinically significant increases in com-

pliance from combinations of interventions, including

some that have not worked in isolation. All of these

approaches are characterized by interactions between

providers and patients, leading to the general conclu-

sion that the level of supervision of and attention to

ongoing care is a key factor.

72

Within this framework,

there appears to be a variety of effective options for in-

teraction. These include feedback of the blood

pressure response to the patient, through blood

pressures taken by either the provider

10

-

78

or the pa-

tient;

74

- " rewarding the patient for improved com-

pliance and/or lowered blood pressure;

28

- "

74

tailor-

ing of medications to daily schedules to decrease

forgetting and inconvenience;

68

'

74

encouraging family

support;

24

engendering self-help through group sup-

port and discussion;

24

-" negotiating a brief written

contract with the patient for improvements in health

behavior;

23

and calling back patients who miss ap-

pointments.

78

Although a provider is present in all of the success-

ful interactions, the type of provider does not appear

to be important. Physicians,

7

' nurses,

8

-

J8> 68

pharma-

cists,

10

health educators,

24

psychologists," and even in-

dividuals with no formal health training

74

have played

the key role in successful interventions. In a similar

vein, although a place for provider and patient to meet

is required, the specific site does not appear to be im-

portant. Compliance with antihypertensive treatment

has been increased in community clinics,

73

general

medical clinics,

76

hypertension clinics,

28

-

24

-

7B

phar-

macies,

10

worksites,

70

-

74

and patients' homes.

8

While most interventions were applied directly to

the patient or the patient's family, one study reported

a beneficial effect of tutorials for house staff and at-

tending staff in a general medical clinic.

76

This study

has important implications for the education of health

professionals.

New Directions in Improving Compliance

The comments in the section above are based on

controlled clinical trials of compliance improvement

strategies which provide us with the most reliable in-

formation available on how to improve compliance;

they indicate that several methods are worthwhile.

Nevertheless, our understanding of compliance

remains incomplete and the ways of improving com-

pliance tested to date are both personnel intensive and

less than fully effective. Thus, we must continue to

seek better understanding of compliance and better

ways to manage it. Two promising avenues of ap-

proach to these goals are studies of the clinician-pa-

tient relationship and the role of social support in

compliance.

Clinician-Patient Relationship

Research into the interactions between clinicians

and patients can be broadly classified into four cate-

gories. Studies in the first category deal with the peda-

gogical techniques employed by practitioners to in-

form patients about their prescribed treatment. These

studies are both correlational

77

"

80

and experimen-

tal

23

-

81

in their design and suggest that greater pro-

vider explicitness regarding needed patient behaviors

is associated with better patient follow-through.

The second category of studies addresses the extent

to which clinicians and patients share the same expec-

tations about their interactions and the effect of this

on subsequent patient compliance ("mutuality of ex-

pectations"). Studies on this topic are difficult to per-

form and remain descriptive at present. They indicate

that when patients' expectations are not fulfilled (for

tests they feel should be ordered, and for treatments

and advice they feel should be rendered), compliance

is likely to be low.

82

"

84

The third category includes investigations into

patients' acceptance of responsibility for following

their prescribed therapy, a procedure suggested by the

self-regulation theories described above. Shulman

85

has found that compliance is better among patients

who feel that they are actively involved in their own

care. While no study has yet isolated patient responsi-

bility from other elements of the therapeutic process,

several studies show that negotiating care with the pa-

tient, rather than simply dictating or prescribing it,

results in better compliance.

11

'

8e

'

M

Roter

90

also found

that attendance at appointments improved when

patients were encouraged to take greater responsi-

bility by asking more questions of their physicians.

Finally, Nessman et al.

7B

found that blood pressures

were better controlled and compliance was higher

among patients randomly allocated to monitor their

own blood pressures at home and choose their own

medications in group sessions, according to a stan-

dard step-wise regimen.

The last category concerns the affective tone of the

patient-clinician encounter. The social learning theory

described above suggests that liked and powerful

others would be more influential. This, again, has

proven a difficult matter to study, and no inter-

ventional studies have been reported. Studies in which

the clinician-patient interaction has been observed

directly support the concept that approachability and

friendliness of the clinician to the patient are positively

correlated with compliance.

80

-

B1

by guest on May 12, 2012 http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ Downloaded from

420 HYPERTENSION VOL 4, No 3, MAY-JUNE 1982

Social Support

The second promising new direction for under-

standing and managing patient compliance is that of

social support, that is, the help that patients receive

from their family and friends to carry on with their

treatments. It has been well documented that patients

from disrupted or isolated social circumstances are

less likely to be good compliers than those with stable

families and/or helpful friends.

92

"

99

Only recently,

however, have there been systematic studies of

attempts to engender or direct social support in order

to improve compliance with antihypertensive.

therapy.

24

'

10

These studies have not shown an inde-

pendent effect on compliance of attempting to pro-

mote social support, but their results must be regarded

as preliminary. Both social learning and self-regula-

tion theories point to a number of complex ways that

social support could enhance compliance.

Ethical Concerns in Applying Compliance Strategies

When attempts are made to improve compliance in

medical practice, rather than in research, the ethical

practitioner should consider the following guide-

lines.

101

'

102

First, the diagnosis must be correct. Sec-

ond, the therapy must be of established efficacy.

Third, neither the illness nor the proposed treatment

can be trivial. Fourth, the patient must be an informed

and willing partner in any attempts to alter his compli-

ance behavior. Finally, the strategy to be employed to

improve compliance must also be of established merit.

Of course, the practitioner must tailor these guide-

lines to fit the circumstances of the individual patient:

therapies and compliance interventions that benefit

most patients are not suitable for all.

In research, the focus of intent shifts from benefit to

the individual patient to the testing of a hypothesis in

order to develop new knowledge. The compliance con-

siderations are somewhat different in this context and

depend on whether the object of the research is testing

a new treatment or a new method of improving com-

pliance. If the former, the compliance maneuver used

should, itself, be of established merit, and we should

be able to say that its application will result in more

adequate testing of the new treatment than could be

achieved without the compliance maneuver. Arrange-

ments should be specified in such studies for detecting

harm to patients to permit their prompt removal from

the study, as an effective compliance maneuver would

increase the rate at which harm occurs and poten-

tially the severity of any harm.

When the object of research is to test the safety

and/or efficacy of a compliance intervention itself, say

in increasing compliance to a standard antihyper-

tensive regimen, there must be good cause to believe

that the compliance intervention is worth testing. This

would include an adequate theoretical base as well as a

protocol for testing that details an adequate research

design. In both this and the previous research situa-

tion, the anticipated harms and benefits must be dis-

closed to the prospective research subject who will be

the final arbitor of the favorability of the balance of

harms and benefits, and thus reach a decision concern-

ing participation in the project.

103

"

105

Monitoring patient compliance also poses ethical

problems because some of the most powerful methods

of measuring compliance require deception in order to

maintain validity. While this matter merits more dis-

cussion than can be provided in this article, the basic

ethical principles that must be observed are that pa-

tients and research subjects must be aware of the fact,

if not the details, of measurement and must agree to

its execution. Practitioners and investigators should

avoid circumstances that create the necessity for

"deceptive debriefing" or "inflicted insight" which are

harms incurred by informing patients about com-

pliance monitoring after the fact.

108

Ethical issues may seem to be insurmountable bar-

riers to the execution of at least some compliance

research: in particular cases there may be serious ten-

sions between the demands of scientific design and

obligations to be respectful of the rights and welfare of

human subjects. However, the guidelines above are

not absolute but rather enter into a more general con-

sideration of benefit versus harm in the decision to

execute a research project. Furthermore, it is usually

possible to negotiate resolutions of such tensions that

all concerned will find satisfactory.

Utilization of Strategies to Increase Compliance

Just as the availability of antihypertensive drugs

does not ensure that they will be prescribed optimally,

the demonstration that various methods of promoting

compliance are effective does not mean that prac-

titioners will or do apply them to advantage or that

students of the health sciences will be taught them. We

attempted to ascertain the extent of utilization of com-

pliance promotion in the public and private health

care delivery sectors and teaching of compliance

management in schools of medicine, nursing and phar-

macy. Sources of information included published

literature and direct contact with medical associa-

tions, schools, clearing houses, and organizations con-

cerned with blood pressure control and education ac-

tivities. This informal survey, the details of which are

related elsewhere,

107

leads us to a few general con-

clusions.

First, there is a vigorous effort being made, partic-

ularly through the National High Blood Pressure Edu-

cation Program, under the National Heart, Lung, and

Blood Institute, to disseminate information about

management of compliance and long-term follow-up

of hypertensive patients, and to organize at the state

level various intervention programs. Through this

process and others, several practical strategies are in

common use including streamlined services, patient

by guest on May 12, 2012 http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ Downloaded from

COMPLIANCE IN HYPERTENSION/A7/fl/ Working Group

421

tracking, instruction, and counseling. However, it is

noteworthy that the most frequently used techniques,

such as public and patient instruction, are not those

shown to be the most effective in well-designed con-

trolled trials. Second, research in this area continues

to grow rapidly.

14

Third, compliance management is

beginning to be taught as a subject in some medical

and other health professional schools. Finally, and un-

fortunately, the private practice sector, in which the

majority of hypertensives are treated, appears as yet

little affected by new information about the manage-

ment of patient compliance.

References

1. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Anti-

hypertensive Agents: Effects of treatment on morbidity in

hypertension. I. Results in patients with diastolic blood pres-

sure averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg. J AMA 202: 1028,

1967

2. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on An-

tihypertensive Agents: Effects of treatment on morbidity.in

hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pres-

sure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. JAMA 213: 1143,

1970

3. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative

Group: Five-year findings of the Hypertension Detection and

Follow-up Program. I. Reduction in mortality of persons with

high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. JAMA 242:

2562, 1979

4. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Anti-

hypertensive Agents: Effects of treatment on morbidity in

hypertension. III. Influence of age, diastolic pressure and prior

cardiovascular diseases: further analysis of side effects. Cir-

culation 45: 991, 1972

5. Sackett DL, Snow JS: The magnitude of compliance and non-

compliance. In Compliance in Health Care, edited by Haynes

RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press: 1979, p 11

6. Finnerty FA, Shaw LW, Himmelsbach CK: Hypertension in

the inner city. II. Detection and follow-up. Circulation 47: 76,

1973

7. Wilber JA, Barrow JG: Hypertension a community

problem. Am J Med 52: 653, 1972

8. Wilber JA, Barrow JG: Reducing elevated blood pressure: ex-

perience found in a community. Minn Med 52: 1303, 1969

9. Caldwell JR, Cobb S, Dowling MD, DeJongh D: The dropout

problem in antihypertensive therapy. J Chron Dis 22: 579,

1970

10. McKenney JM, Slining J M, Henderson HR, Devins D, Barr

M: The effect of clinical pharmacy services on patients with es-

sential hypertension. Circulation 48: 1104, 1973

11. Rudnick KV, Sackett DL, Hirst S, Holmes C: Hypertension

in a family practice. Can Med Assoc J 117: 492, 1977

12. Baitz T, Shimizu A: Blood pressure surveys: Are they worth

it? Can Fam Physician 23: 70, 1977

13. Borhani N: Implementation and evaluation of community

hypertension programs. In Epidemiology and Control of

Hypertension, edited by Paul O. Miami: Symposia Special-

ists, 1975, p 627

14. Haynes RB: Introduction. In Compliance in Health Care,

edited by Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL. Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979, p 1

15. Haynes RB: A critical review of the "determinants" of pa-

tient compliance with therapeutic regimens. In Compliance

with Therapeutic Regimens, edited by Sackett DL, Haynes

RB. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976, p 26

16. Haynes RB: Determinants of compliance: the disease and the

mechanics of treatment. In Compliance in Health Care, edited

by Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1979, p 49

17. Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Gibson ES, Hackett BC, Taylor

DW, Roberts RS, Johnson AL: Randomized clinical trial of

strategies for improving medication compliance in primary

hypertension. Lancet 1: 1205, 1975

18. Alderman MA, Miller KF: Blood pressure control: the effect

of facilitated access to treatment. Clin Sci Molec Med 55:

249s, 1979

19. Colcher IS, Bass JW: Penicillin treatment of streptococcal

pharyngitis: A comparison of schedules and the role of specific

counselling. JAMA 222: 657, 1972

20. Sharpe TR, Mikeal RL: Patient compliance with antibiotic

regimens. Am J Hosp Pharm 31: 479, 1974

21. Linkewich JA, Catalano RB, Flack HL: The effect of packag-

ing and instruction on outpatient compliance with medication

regimens. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 8: 10, 1974

22. Dickey FF, Mattar ME, Chudzik GM: Pharmacist counsel-

ling increases drug regimen compliance. Hospitals 49: 85,

1975

23. Swain MA, Steckel SB: Influencing adherence among hyper-

tensives. Res Nurs Hlth 4: 213, 1981

24. Levine DM, Green LW, Deeds SG, Chwalow J, Russell P,

Finlay J: Health education for hypertensive patients. JAMA

241: 1700, 1979

25. Caplan RD, Robinson E, French J, Caldwell J, Shinn M:

Adhering to Medical Regimens Pilot Experiments in Pa-

tient Education and Social Support. Ann Arbor, Michigan:

Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann

Arbor, 1976

26. Tagliacozzo DM, Lusking DB, Lashof J C, Ima K: Nurse in-

tervention and patient behavior. Am J Public Health 64: 596,

1974

27. Becker MH: The health belief model and personal health

behavior. Health Educ Monogr 2: 324, 1974

28. Becker MH: Sociobehavioral determinants of compliance. In

Compliance with Therapeutic Regimens, edited by Sackett

DL, Haynes RB. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press,

1976, p 40

29. Haynes RB: Strategies for improving compliance: a method-

ologic analysis and review. In Compliance with Therapeutic

Regimens edited by Sackett DL, Haynes RB. Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976, p 69

30. Sackett DL: Priorities and methods for future research. In

Compliance with Therapeutic Regimens, edited by Sackett

DL, Haynes RB. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press,

1976, p 169

31. Dunbar J M, Stunkard AJ: Adherence to diet and drug

regimen. In Nutrition, Lipids, and Coronary Heart Disease,

edited by Levy R, Rifkind B, Dennis B, Ernst N. New York:

Raven Press, 1979, p 391

32. Leventhal H: Findings and theory in the study of fear com-

munications. In Recent Advances in Social Psychology, edited

by Berkowitz L. New York: Academic Press, 1970, p 119

33. Leventhal H, Singer R, Jones S: Effects of fear and specificity

of recommendations upon attitudes and behavior. J Pers Soc

Psychol 2: 20, 1964

34. Leventhal H, Watts JC, Pagano F: Effects of fear and instruc-

tions on how to cope with danger. J Pers Soc Psychol 6: 313,

1967

35. Sternthal B, Craig CS: Fear appeals: revisited and revised. J

Consumer Res 1: 22, 1974

36. Janis IL, Feshback S: Personality differences associated with

responsiveness to fear arousing communications. J Pers 23:

154, 1954

37. Kelly AB: A media role for public health compliance? In

Compliance in Health Care, edited by Haynes RB, Taylor

DW, Sackett DL. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press,

1979, p 193

38. Best JA, Bloch M: Compliance in the control of cigarette

smoking. In Compliance in Health Care, edited by Haynes

RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press, 1979, p 202

39. Skinner BF: Sciences and Human Behavior. New York:

MacMillan, 1953

by guest on May 12, 2012 http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ Downloaded from

422 HYPERTENSION VOL 4, No 3, MAY-JUNE 1982

40. Skinner BF: Are theories of learning necessary? Psychol Rev

57: 193, 1950

41. Bandura A: Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs:

Prentice-Hall, 1977

42. Mahoney MJ: Cognition and Behavior Modification. Cam-

bridge: Ballinger, 1974

43. Wiener N: Cybernetics. New York: Wiley and Sons, 1948

44. Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D: Self-regulation and the

mechanisms for symptom appraisal. In Psychosocial

Epidemiology, edited by Mechanic D. New York: Neal Wat-

son Academic Publications, 1980

45. Lazarus R: Psychological Stress and Coping Process. New

York: McGraw-Hill, 1966

46. Caron HS, Roth HP: Patients' cooperation with a medical

regimen. J AMA 203: 922, 1968

47. Dixon WM, Stradling P, Wootton ID: Outpatient PAS

therapy. Lancet 2: 871, 1957

48. Moulding T, Onstad GD, Sbarbaro JA: Supervision of outpa-

tient drug therapy with the medication monitor. Ann Intern

Med 73: 559, 1970

49. Mushlin AI, Appel FA: Diagnosing patient noncompliance.

Arch Intern Med 137: 318, 1977

50. Gilbert R, Evans CE, Haynes RB, Tugwell P: Predicting com-

pliance with digoxin: study in family practice. Can Med Assoc

J 123: 119, 1980

51. Park LC, Lipman RS: A comparison of patient dosage devia-

tion reports with pill counts. Psychopharmacologia 6: 229,

1964

52. Feinstein AR, Wood HF, Epstein JA, Taranta A, Simpson R,

Tursky E: A controlled study of three methods of prophylaxis

against streptococcal infection in a population of rheumatic

children. II. Results of the first three years of the study, includ-

ing methods for evaluating the maintenance of oral prophylax-

is. N Engl J Med 260: 697, 1959

53. Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL, Gibson ES, Bernholz

CD, Mukherjee J: Can simple clinical measurements detect

patient non-compliance? Hypertension 2: 757, 1980

54. Moulding T, Onstad GD, Sbarbaro JA: Supervision of outpa-

tient drug therapy with the medication monitor. Ann Intern

Med 73: 559, 1970

55. Rheder TL, McCoy LK, Blackwell B, Whitehead W, Robin-

son A: Improving medication compliance by counselling and a

special prescription container. Am J Hosp Pharm 37: 379,

1980

56. Roth HP, Caron HS, Hsi BP: Measuring intake of a pre-

scribed medication: a bottle count and a tracer technique com-

pared. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2: 228, 1970

57. Soutter BR, Kennedy MB: Patient compliance assessment in

drug trials: usage and methods. Aust NZ J Med 4: 360, 1974

58. Rickels K, Briscoe E: Assessment of dosage deviation in out-

patient drug research. J Clin Pharmacol 10: 153, 1970

59. Gundert-Remy U, Remy C, Weber E: Serum digoxin levels in

patients of a general practice in Germany. Eur J Clin Phar-

macol 10: 97, 1976

60. Gibberd FB, Dunne J F, Handley AJ, Hazleman BL: Super-

vision of epileptic patients taking phenytoin. Br Med J 1: 147,

1970

61. Lund M, Jorgenson RS, Kuhl V: Serum diphenylhydantoin

(phenytoin) in ambulant patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia 5:

51, 1964

62. Gordis L: Conceptual and methodologic problems in measur-

ing patient compliance. In Compliance in Health Care, edited

by Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1979, p 23

63. Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Taylor DW: Practical management

of low compliance with anti hypertensive therapy: a guide for

the busy practitioner. Clin Invest Med 1: 175, 1979

64. Stahl SM, Lawrie T, Neill P, Kelley C: Motivational inter-

ventions in community hypertension screening. Am J Pub

Hlth 67: 345, 1977

65. Harris L: The Public and High Blood Pressure. A Survey.

Bethesda: DHEW Publication No. (NIH) 74-356, 1973

66. Hoehn-Saric R, Frank J, Imber S, Nash E, Stone A, Battle C:

Systematic preparation of patients for psychotherapy 1)

effects on therapy behavior and outcome. J Psychiatr Res 2:

267, 1964

67. Fletcher S, Appel F, Bourgois M: Management of hyperten-

sion: effect of improving patient compliance for follow-up

care. J AMA 233: 242, 1975

68. Logan AS, Milne BJ, Achber C, Campbell WP, Haynes RB:

Worksite treatment of hypertension by specially trained

nurses: a controlled trial. Lancet 2: 1175, 1979

69. Johnson AL, Taylor DW, Sackett DL, Dunnett CW, Shimizu

AG: Self-recording of blood pressure in the management of

hypertension. CMAJ 119: 1034, 1978

70. Alderman MA, Miller KF: Blood pressure control: the effect

of facilitated access to treatment. Clin Sci Molec Med 55:

249s, 1978

71. Shepard DS, Foster SB, Stason WB, Solomon HS, McArdle

PJ, Gallagher SS: Cost-effectiveness of interventions to im-

prove compliance with antihypertensive therapy. Prev Med 8:

229, 1979

72. Haynes RB: Strategies to improve compliance with referrals,

appointments, and prescribed medical regimens. In

Compliance in Health Care, edited by Haynes RB, Taylor

DW, Sackett DL. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press,

1979, p 121

73. Takala J, Niemela N, Rosti J, Sivers K: Improving compli-

ance with therapeutic regimens in hypertensive patients in a

community health centre. Circulation 59: 540, 1979

74. Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Gibson ES, Taylor DW, Hackett

BC, Roberts RS, Johnson AL: Improvement of medication

compliance in uncontrolled hypertension. Lancet 1:1265, 1976

75. Nessman DG, Carnahan J E, Nugent CA: Improving com-

pliance. Patient-operated hypertension groups. Arch Intern

Med 140: 1427, 1980

76. Inui T, Yourtee E, Williamson J: Improved outcomes in

hypertension after physician tutorials. Ann Intern Med 84:

646, 1976

77. Kincey J, Bradshaw P, Ley P: Patients' satisfaction and

reported acceptance of advice in general practice. J R Coll Gen

Pract 25: 558, 1975

78. Ley P: Memory for medical information. Br J Soc Clin

Psychol 18: 245, 1979

79. Hulka B: Patient-clinican interactions and compliance. In

Compliance in Health Care, edited by Haynes RB, Taylor

DW, Sackett D. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press,

1979, p 63 ;

80. Svarstad B: Physician-patient communication and patient

conformity with the medical advice. In The Growth of Bureau-

cratic Medicine, edited by Mechanic D. New York: Wiley,

1976, p 220

81. Ley P, Whitworth M, Skilbeck C, Woodward R, Pinsent R,

Pike L, Clarkson M, Clark P: Improving doctor-patient com-

munication in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract 26: 720,

1976

82. Davis M: Variations in patients' compliance with doctors' ad-

vice: an empirical analysis of patterns of communication. Am

J Pub Hlth 58: 274, 1968

83. Korsch B, Gozzi B, Francis V: Gaps in doctor-patient com-

munication: doctor-patient interaction and patient satisfac-

tion. Pediatrics 42: 855, 1968

84. Francis V, Korsh B, Morris M: Gaps in doctor-patient com-

munication: patients' response to medical advice. N Engl J

Med 280: 535, 1969

85. Shulman B: Active patient orientation and outcomes in hyper-

tensive treatment. Med Care 17: 267, 1979

86. Eisenthal S, Emery R, Lazare A, Udin H: "Adherence" and

the negotiated approach to patienthood. Arch Gen Psychiatr

36: 393, 1979

87. Eisenthal S, Lazare A: Evaluation of the initial interview in a

walk-in clinic: the clinician's perspective on a "negotiated ap-

proach". J Nerv Ment Dis 164: 30, 1977

88. Tracy J: Impact of intake procedures upon client attrition in a

community mental health centre. J Consult Clin Psychol 45:

192, 1977

89. Barofsky I: Compliance, adherence and the therapeutic

alliance: steps in the development of self-care. Soc Sci Med 12:

369, 1978

90. Roter D: Patient participation in the patient-provider interac-

tion: the effects of patient question asking on the quality of in-

teraction, satisfaction and compliance. Health Educ Monogr

5: 281, 1977

by guest on May 12, 2012 http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ Downloaded from

COMPLIANCE IN HYPERTENSION/A7/I5/ Working Group 423

91. Freemon B, Negrete V, Davis M, Korsch B: Gaps in doctor-

patient communication: doctor-patient interaction analysis.

Pediatr Res 5: 298, 1971

92. Diamond MD , Weiss AJ, Grynbaum B: The unmotivated pa-

tient. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 49: 281, 1968

93. Donabedian A, Rosenfeld LS: Follow-up study of chronically

ill patients discharged from hospital. J Chron Dis 17: 847,

1964

94. Elling R, Whittemore R, Green M: Patient participation in a

pediatric program. J Hlth Hum Behav 1: 183, 1960

95. Macdonald ME, Hagberg KL, Grossman BJ: Social factors in

relation to participation in follow-up care of rheumatic fever. J

Pediatr 62: 503, 1963

96. Oakes TW, Ward JR, Gray RM, Klauber MR, Moody PM:

Family expectations and arthritis patient compliance to a hand

resting splint regimen. J Chron Dis 22: 757, 1970

97. Parks CM, Brown GW, Monck EM: The general practitioner

and the schizophrenic patient. Br Med J 1: 972, 1962

98. Pentecost R, Zwerenz B, Manuel J: Intrafamily identity and

home dialysis success. Nephron 17: 88, 1976

99. Schwartz D, Wang M, Zietz L, Goss ME: Medication errors

made by elderly, chronically ill patients. Am J Pub Hlth 52:

2018, 1962

100. Earp JA, Ory MG: The effects of social support and health

professional home visits on patient adherence to hypertension

regimens. Prev Med 8: 155, 1979

101. Sackett DL. Introduction. In Compliance with Therapeutic

Regimens, edited by Sackett DL, Haynes RB. Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976, p 4

102. Jonsen AR. 'Ethical issues in compliance. In Compliance in

Health Care, edited by Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL,

eds. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979, p 113

103. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1979, chapter 8

104. National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects

of Biomedical and Behavioral Research (Commission): The

Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for Protec-

tion of Human Subjects of Research. Washington, D.C.:

DHEW Publication no. (05) 79-0012, 1979

105. Levine RJ, Lebacqz K. Some ethical considerations in clinical

trials. Clin Pharmacol Thera 25: 728, 1979

106. Baumrind D. IRBs and social science research: the costs of

deception. IRB: a review of human subjects research, 1: 1,12,

1979

107. Mattson ME, Engebretson TO Jr. Trends in the utilization of

strategies to improve compliance in hypertensives. In Patient

Compliance to Prescribed Antihypertensive Medication Reg-

imens: A Report to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Insti-

tute. USD HHS, PHS, NIH, NIH Publication No. 80-2102.

Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office, 1980, p 165

by guest on May 12, 2012 http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ Downloaded from

Вам также может понравиться

- ESC Arterial Hypertension 2018Документ98 страницESC Arterial Hypertension 2018ddantoniusgmailОценок пока нет

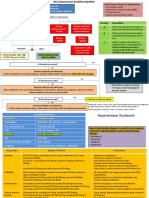

- Hypertension Treatment Steps For HypertensionДокумент15 страницHypertension Treatment Steps For Hypertensionfreelancer08100% (1)

- 5 HypertensionДокумент219 страниц5 HypertensionRaul GascueñaОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Penatalaksanaan EdemaДокумент7 страницJurnal Penatalaksanaan EdemaMariska Nada Debora100% (1)

- Management of Hypertension in CKD 2015Документ9 страницManagement of Hypertension in CKD 2015Alexander BallesterosОценок пока нет

- Pola Makan Vs DMДокумент8 страницPola Makan Vs DMRidyahningtyas SintowatiОценок пока нет

- Anemia E.C Hematemesis Melena E.C Suspect Gastritis ErrosiveДокумент37 страницAnemia E.C Hematemesis Melena E.C Suspect Gastritis ErrosiveAndayanaIdhamОценок пока нет

- Komunikasi Kesehatan: Prodi Kesehatan Masyarakat Universitas Muhammadiyah SurakartaДокумент11 страницKomunikasi Kesehatan: Prodi Kesehatan Masyarakat Universitas Muhammadiyah SurakartaUlima Fadhilah LarasatiОценок пока нет

- Diabetes Mellitus Type 2Документ16 страницDiabetes Mellitus Type 2MTs MIFDAОценок пока нет

- Dr. Erlieza Roosdhania, SP - PD (CKD)Документ38 страницDr. Erlieza Roosdhania, SP - PD (CKD)Pon PondОценок пока нет

- Daftar Pustaka Hipertensi Pada Usia MudaДокумент10 страницDaftar Pustaka Hipertensi Pada Usia MudaToby Hadinata WiranegaraОценок пока нет

- Peritoneal Dialysis Versus Hemodialysis Risks, Benefits, and Access Issues Clinical SummaryДокумент5 страницPeritoneal Dialysis Versus Hemodialysis Risks, Benefits, and Access Issues Clinical SummaryMarko A. MartínОценок пока нет

- Methacholine1 21Документ21 страницаMethacholine1 21Mihaela Dudau100% (1)

- Corrosive PoisoningДокумент4 страницыCorrosive PoisoningaBay AesculapianoОценок пока нет

- Medicinus Agustus SmallДокумент64 страницыMedicinus Agustus SmallNovry DodyОценок пока нет

- ARBs (Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers) NCLEXДокумент15 страницARBs (Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers) NCLEXSameerQadumi100% (1)

- Daftar PustakaДокумент3 страницыDaftar PustakaIndrasti BanjaransariОценок пока нет

- High Blood Pressure GuideДокумент4 страницыHigh Blood Pressure GuideKhaira CharmagneОценок пока нет

- DKA Case Report on Type 1 Diabetes MellitusДокумент56 страницDKA Case Report on Type 1 Diabetes Mellitushilmiana putriОценок пока нет

- DyslipidemiaДокумент21 страницаDyslipidemiaBasil HussamОценок пока нет

- Ketogenic Diet in The Management of Diabetes: June 2017Документ8 страницKetogenic Diet in The Management of Diabetes: June 2017Indra Setya PermanaОценок пока нет

- Bimbingan Dokter Hari - CKDДокумент24 страницыBimbingan Dokter Hari - CKDVicky LumalessilОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Pemilihan Tatalaksana PPOKДокумент6 страницJurnal Pemilihan Tatalaksana PPOKAsyraf HabibieОценок пока нет

- Bhagani 2018Документ7 страницBhagani 2018rifky kurniawanОценок пока нет

- KDIGO Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of CKD-MBDДокумент65 страницKDIGO Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of CKD-MBDCitra DessyОценок пока нет

- Drug InteractionДокумент2 страницыDrug InteractionNicole EncinaresОценок пока нет

- JNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionДокумент2 страницыJNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- Asthma in the 21st Century: New Research AdvancesОт EverandAsthma in the 21st Century: New Research AdvancesRachel NadifОценок пока нет

- Pharmacogenomics: From Discovery to Clinical ImplementationОт EverandPharmacogenomics: From Discovery to Clinical ImplementationShowkat Ahmad GanieОценок пока нет

- Hypertension, Cardiovascular Disease, Analgesics, and Endocrine DisordersОт EverandHypertension, Cardiovascular Disease, Analgesics, and Endocrine DisordersJack Z. YetivОценок пока нет

- Cyanosis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsОт EverandCyanosis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Glucose Intake and Utilization in Pre-Diabetes and Diabetes: Implications for Cardiovascular DiseaseОт EverandGlucose Intake and Utilization in Pre-Diabetes and Diabetes: Implications for Cardiovascular DiseaseРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- Moriskyetal MedicalCare-JSTOR1986Документ10 страницMoriskyetal MedicalCare-JSTOR1986Moch MimarОценок пока нет

- Self-Reported Measure Validity for Medication Adherence PredictionДокумент9 страницSelf-Reported Measure Validity for Medication Adherence PredictionEsti AsadinaОценок пока нет

- Vermeire Et Al-2001-Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and TherapeuticsДокумент12 страницVermeire Et Al-2001-Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and TherapeuticsveronikiОценок пока нет

- Adherence To Therapy: Challenges in HCV-Infected PatientsДокумент9 страницAdherence To Therapy: Challenges in HCV-Infected PatientsjulianatairaОценок пока нет

- Becker 1980Документ23 страницыBecker 1980Lorena PăduraruОценок пока нет

- Eraker 1984Документ11 страницEraker 1984Lorena PăduraruОценок пока нет

- JCH 14332Документ6 страницJCH 14332Sophian HaryantoОценок пока нет

- HI12!64!73 PatientBehavior R8Документ10 страницHI12!64!73 PatientBehavior R8David IoanaОценок пока нет

- Compliance in Heart Failure Patients: The Importance of Knowledge and BeliefsДокумент7 страницCompliance in Heart Failure Patients: The Importance of Knowledge and BeliefsNurfitriah NasirОценок пока нет

- Continuity of Care: Literature Review and ImplicationsДокумент10 страницContinuity of Care: Literature Review and ImplicationsRona RihadahОценок пока нет

- NICE Guidelines For The Management of DepressionДокумент2 страницыNICE Guidelines For The Management of DepressionstefenandreanОценок пока нет

- Metanalisis Adherencia Al TratamientoДокумент9 страницMetanalisis Adherencia Al TratamientosergioОценок пока нет

- Ajph 58 2 274Документ15 страницAjph 58 2 274govindmanianОценок пока нет

- Journal Pone 0094207Документ7 страницJournal Pone 0094207JuanaОценок пока нет

- How Communication Impacts Health OutcomesДокумент7 страницHow Communication Impacts Health OutcomesBegert JamesОценок пока нет

- From Compliance To Concordance in Diabetes: Clinical EthicsДокумент4 страницыFrom Compliance To Concordance in Diabetes: Clinical Ethicschatarina anugrahОценок пока нет

- Science Current Directions in Psychological: Patient Adherence With Medical Treatment Regimens: An Interactive ApproachДокумент5 страницScience Current Directions in Psychological: Patient Adherence With Medical Treatment Regimens: An Interactive Approachadri90Оценок пока нет

- Adherence TheoriesДокумент6 страницAdherence TheoriesmakmgmОценок пока нет

- We Need Minimally Disruptive Medicine: AnalysisДокумент3 страницыWe Need Minimally Disruptive Medicine: Analysisapi-252646029Оценок пока нет

- BMC Family PracticeДокумент10 страницBMC Family PracticeThiago SartiОценок пока нет

- 240 FullДокумент9 страниц240 FullfmОценок пока нет

- Using A Problem Detection Study (PDS) To Identify and Compare Health Care Provider and Consumer Views of Antihypertensive TherapyДокумент9 страницUsing A Problem Detection Study (PDS) To Identify and Compare Health Care Provider and Consumer Views of Antihypertensive TherapySri Rahayu Mardiah KusumaОценок пока нет

- Low-literacy flashcards boost medication adherenceДокумент19 страницLow-literacy flashcards boost medication adherenceCORO CORPSОценок пока нет

- 64Документ9 страниц64parameswarannirushanОценок пока нет

- EBMДокумент636 страницEBMDaniel SalaОценок пока нет

- Editorial: The New Hypertension Guideline: Logical But UnwiseДокумент3 страницыEditorial: The New Hypertension Guideline: Logical But UnwiseLuamater MaterОценок пока нет

- Definition de Adherencia TerapéuticaДокумент3 страницыDefinition de Adherencia TerapéuticaXimena HenaoОценок пока нет

- EtikДокумент7 страницEtikTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Hester PediatricEthicsFinalProofsДокумент9 страницHester PediatricEthicsFinalProofsFitria FitriaОценок пока нет

- Impacts of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Children: An Ethical Analysis With A Global-Child LensДокумент10 страницImpacts of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Children: An Ethical Analysis With A Global-Child LensTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- CEBM Levels of EvidenceДокумент2 страницыCEBM Levels of EvidenceEnisahОценок пока нет

- Severe sepsis criteria, PELOD-2, and pSOFA as predictors of mortality in critically ill children with sepsisДокумент19 страницSevere sepsis criteria, PELOD-2, and pSOFA as predictors of mortality in critically ill children with sepsisTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Ethics in Pediatric Patient CareДокумент12 страницEthics in Pediatric Patient CareTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Sepsis NeonatalДокумент13 страницSepsis NeonatalVianey Estefania Hernandez HernandezОценок пока нет

- Sepsis NeonatalДокумент13 страницSepsis NeonatalVianey Estefania Hernandez HernandezОценок пока нет

- 10 1001@jama 2020 10044Документ11 страниц10 1001@jama 2020 10044Rodrigo Ehécatl Torres NevárezОценок пока нет

- Review of Neonatal Sepsis Causes, Risk Factors and ManagementДокумент9 страницReview of Neonatal Sepsis Causes, Risk Factors and ManagementTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Kuppermann2018 PDFДокумент13 страницKuppermann2018 PDFriska yulizaОценок пока нет

- Tugas Dr. M Riza, Sp.a (K), M.kesДокумент12 страницTugas Dr. M Riza, Sp.a (K), M.kesTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Worksheet CohortДокумент3 страницыWorksheet CohortTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Skor PELOD-CohortДокумент7 страницSkor PELOD-CohortTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Tugas Dr. M Riza, Sp.A (K), M.KesДокумент12 страницTugas Dr. M Riza, Sp.A (K), M.KesTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Practical Algorithms - Stomach-And-Intestine-2014Документ12 страницPractical Algorithms - Stomach-And-Intestine-2014Tiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Tugas Dr. M Riza, Sp.A (K), M.KesДокумент12 страницTugas Dr. M Riza, Sp.A (K), M.KesTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Tugas Dr. M Riza, Sp.a (K), M.kesДокумент12 страницTugas Dr. M Riza, Sp.a (K), M.kesTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Drug Doses 2017Документ127 страницDrug Doses 2017Yuliawati HarunaОценок пока нет

- Severe sepsis criteria, PELOD-2, and pSOFA as predictors of mortality in critically ill children with sepsisДокумент19 страницSevere sepsis criteria, PELOD-2, and pSOFA as predictors of mortality in critically ill children with sepsisTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Skor PELOD-CohortДокумент7 страницSkor PELOD-CohortTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Tugas Dr. M Riza, Sp.A (K), M.KesДокумент12 страницTugas Dr. M Riza, Sp.A (K), M.KesTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Guidelines For Surfactant Replacement Therapy in Neonates Canadian Paediatric SocietyДокумент8 страницGuidelines For Surfactant Replacement Therapy in Neonates Canadian Paediatric SocietyTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Practical Algorithms in Pediatric NephrologyДокумент126 страницPractical Algorithms in Pediatric NephrologyJonathan Welch100% (2)

- Review of Neonatal Sepsis Causes, Risk Factors and ManagementДокумент9 страницReview of Neonatal Sepsis Causes, Risk Factors and ManagementTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Practical Algorithms in Pediatric EndocrinologyДокумент22 страницыPractical Algorithms in Pediatric EndocrinologyTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Critical Therapy Study ResultsДокумент4 страницыCritical Therapy Study ResultsAinur 'iin' RahmahОценок пока нет

- Practical Algorithms in Pediatric Endocrinology: 2nd, Revised EditionДокумент116 страницPractical Algorithms in Pediatric Endocrinology: 2nd, Revised Editionعبد الله عبد اللهОценок пока нет

- Practical-Algorithms-Diare KronisДокумент20 страницPractical-Algorithms-Diare KronisTiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Practical Algorithms - Stomach-And-Intestine-2014Документ12 страницPractical Algorithms - Stomach-And-Intestine-2014Tiwi QiraОценок пока нет

- Pit VeriscolorДокумент5 страницPit VeriscolorNida Fithria FadhilaОценок пока нет

- Effectiveness of Occupational Goal Intervention For Clients With SchizophreniaДокумент10 страницEffectiveness of Occupational Goal Intervention For Clients With SchizophreniaIwanОценок пока нет

- Spartan Bodyweight WorkoutsДокумент102 страницыSpartan Bodyweight WorkoutsSamir DjoudiОценок пока нет

- Summer Internship Report on Chemist Behavior Towards Generic ProductsДокумент30 страницSummer Internship Report on Chemist Behavior Towards Generic ProductsBiswadeep PurkayasthaОценок пока нет

- Method Development and Validation For Estimation of Moxifloxacin HCL in Tablet Dosage Form by RP HPLC Method 2153 2435.1000109Документ2 страницыMethod Development and Validation For Estimation of Moxifloxacin HCL in Tablet Dosage Form by RP HPLC Method 2153 2435.1000109David SanabriaОценок пока нет

- College Women's Experiences With Physically Forced, Alcohol - or Other Drug-Enabled, and Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault Before and Since Entering CollegeДокумент12 страницCollege Women's Experiences With Physically Forced, Alcohol - or Other Drug-Enabled, and Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault Before and Since Entering CollegeGlennKesslerWP100% (1)

- Cosmetic BrochureДокумент4 страницыCosmetic BrochureDr. Monika SachdevaОценок пока нет

- Ijspt 10 734 PDFДокумент14 страницIjspt 10 734 PDFasmaОценок пока нет

- Bcspca Factsheet Life of An Egg Laying Hen PDFДокумент2 страницыBcspca Factsheet Life of An Egg Laying Hen PDFAnonymous 2OMEDZeqCDОценок пока нет

- Context & Interested Party AnalysisДокумент6 страницContext & Interested Party AnalysisPaula Angelica Tabia CruzОценок пока нет

- Hazards of Dietary Supplement Use: Anthony E. Johnson, MD Chad A. Haley, MD John A. Ward, PHDДокумент10 страницHazards of Dietary Supplement Use: Anthony E. Johnson, MD Chad A. Haley, MD John A. Ward, PHDJean CotteОценок пока нет

- Packaged Drinking Water Project ProfileДокумент5 страницPackaged Drinking Water Project ProfileArpna BhatiaОценок пока нет

- List of Pakistani Government Ministries and DivisionsДокумент2 страницыList of Pakistani Government Ministries and DivisionsbasitaleeОценок пока нет

- MIDDLE ENGLISH TEST HEALTH VOCATIONAL HIGH SCHOOLДокумент4 страницыMIDDLE ENGLISH TEST HEALTH VOCATIONAL HIGH SCHOOLZaenul WafaОценок пока нет

- CAP Regulation 35-5 - 03/16/2010Документ20 страницCAP Regulation 35-5 - 03/16/2010CAP History LibraryОценок пока нет

- Editorial Intro DR Jessica Rose-The Lies Vaccinologists Tell Themselves - VAERS Receives Due ScrutinyДокумент3 страницыEditorial Intro DR Jessica Rose-The Lies Vaccinologists Tell Themselves - VAERS Receives Due ScrutinySY LodhiОценок пока нет

- 4400 SystemДокумент24 страницы4400 SystemRaniel Aris LigsayОценок пока нет

- Research Paper For AbortionДокумент10 страницResearch Paper For AbortionMarevisha Vidfather75% (4)

- Pharmacology Mock Exam MCQДокумент8 страницPharmacology Mock Exam MCQanaeshklОценок пока нет

- Dapagliflozin Uses, Dosage, Side Effects, WarningsДокумент8 страницDapagliflozin Uses, Dosage, Side Effects, WarningspatgarettОценок пока нет

- Similarities and Differences Between Brainwave Optimization PDFДокумент5 страницSimilarities and Differences Between Brainwave Optimization PDFthrillhausОценок пока нет

- Brand Analysis of Leading Sanitary Napkin BrandsДокумент21 страницаBrand Analysis of Leading Sanitary Napkin BrandsSoumya PattnaikОценок пока нет

- Wto Unit-2Документ19 страницWto Unit-2Anwar KhanОценок пока нет

- Master Plan for Trivandrum City 2021-2031Документ21 страницаMaster Plan for Trivandrum City 2021-2031Adhithy MenonОценок пока нет

- Social Welfare Administrartion McqsДокумент2 страницыSocial Welfare Administrartion McqsAbd ur Rehman Vlogs & VideosОценок пока нет

- Wellness massage exam questionsДокумент3 страницыWellness massage exam questionsElizabeth QuiderОценок пока нет

- A Plant-Growth Promoting RhizobacteriumДокумент7 страницA Plant-Growth Promoting RhizobacteriumdanyjorgeОценок пока нет

- BG Gluc2Документ3 страницыBG Gluc2Nghi NguyenОценок пока нет

- Kaplan Grade OverviewДокумент5 страницKaplan Grade Overviewapi-310875630Оценок пока нет

- Dr. Nilofer's Guide to Activator & Bionator AppliancesДокумент132 страницыDr. Nilofer's Guide to Activator & Bionator Appliancesdr_nilofervevai2360100% (3)