Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Kastarinen HT Mott

Загружено:

Preha Prehaningrum0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

10 просмотров8 страницjurnal

Оригинальное название

Kastarinen Ht Mott

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документjurnal

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

10 просмотров8 страницKastarinen HT Mott

Загружено:

Preha Prehaningrumjurnal

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 8

Non-pharmacological treatment of hypertension in primary

health care: a 2-year open randomized controlled trial of

lifestyle intervention against hypertension in eastern Finland

Mika J. Kastarinen

a

, Pekka M. Puska

b

, Maarit H. Korhonen

c

,

Juha N. Mustonen

d

, Veikko V. Salomaa

e

, Jouko E. Sundvall

f

,

Jaakko O. Tuomilehto

e,g

, Matti I. Uusitupa

c

and Aulikki M. Nissinen

e

for the LIHEF Study Group

Objective To assess whether lifestyle counselling is

effective in non-pharmacological treatment of

hypertension in primary health care.

Design Open randomized controlled trial.

Setting Ten municipal primary health care centres in

eastern Finland.

Patients Seven hundred and fteen subjects aged 2574

years with systolic blood pressure 140179 mmHg and/or

diastolic blood pressure 90109 mmHg or

antihypertensive drug treatment.

Interventions Systematic health counselling given by local

public health nurses for 2 years.

Main outcome measures Blood pressure, lipids and

lifestyle data were collected annually.

Results Among participants with no antihypertensive drug

treatment, the net reductions after 1 year both in systolic

blood pressure [22.6 mmHg; 95% condence interval (CI),

24.7 to 20.5 mmHg] and in diastolic blood pressure

(22.7 mmHg; 95% CI, 24.0 to 21.4 mmHg) were

signicant in favour of the intervention group. This

difference in blood pressure change was maintained

during the second year. In participants with

antihypertensive drug treatment, no signicant difference

in blood pressure reduction was seen between the groups

during the study.

Conclusions A relatively modest, but systematic

counselling in primary health care can, at least among

untreated hypertensive subjects, produce reductions in

blood pressure levels that are modest for the individual,

but very important from the public health point of view.

J Hypertens 20:25052512 & 2002 Lippincott Williams &

Wilkins.

Journal of Hypertension 2002, 20:25052512

Keywords: hypertension, randomized controlled trial, life change events

a

Department of Public Health and General Practice, University of Kuopio, Kuopio,

Finland,

b

Department of Non-communicable Disease Prevention and Health

Promotion, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland,

c

Department of Clinical Nutrition,

University of Kuopio, Kuopio, Finland,

d

Department of Internal Medicine, North

Karelia Central Hospital, Joensuu, Finland,

e

Department of Epidemiology and

Health Promotion, National Public Health Institute, Helsinki, Finland,

f

Department of Health and Functional Capacity, National Public Health Institute,

Helsinki, Finland and

g

Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki,

Finland.

Sponsorship: This study has been supported by the grants from the following

institutions: the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, the Juho Vainio

Foundation, the National Public Health Institute, the Finnish Ofce for Health

Care Technology Assessment, the Graduate School of Public Health in the

University of Kuopio, the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, the

North Savo Regional Fund of the Finnish Cultural Foundation, the Duodecim

Society, the Aarne and Aili Turunen Foundation, the Ida Montin Foundation and

the EVO Funding from the Kuopio University Hospital.

Correspondence and request for reprints to Mika Kastarinen, MD, Department of

Public Health and General Practice, University of Kuopio, PB 1627, 70211

Kuopio, Finland.

Tel: +358-17-162912; fax: +358-17-162937; e-mail: mika.kastarinen@uku.

Received 23 May 2002 Revised 26 July 2002

Accepted 21 August 2002

Introduction

Evidence indicates that lifestyle measures such as

weight reduction, moderation of alcohol consumption,

reduction in salt intake and increase in physical

activity are feasible and effective in lowering blood

pressure (BP), either alone or in combination with

antihypertensive drug therapy [16]. Some studies

have suggested that fat-modication of the diet or a

diet with low saturated fat intake, but rich in fruits,

vegetables and bre, have a signicant BP-lowering

effect [4,7]. In addition to its effect on BP, such

modication of lifestyle can also reduce the levels of

other cardiovascular risk factors. According to the

latest international and national hypertension guide-

lines, non-pharmacological measures are recommended

as the rst-line therapy for the patients with newly

diagnosed, uncomplicated hypertension and they

should also be applied in the treatment of every

Original article 2505

0263-6352 & 2002 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 10.1097/01.hjh.0000042893.24999.db

hypertensive patient treated with antihypertensive

drugs [810].

Most of the clinical trials assessing the feasibility and

effects of health education targeted to the prevention

and control of hypertension have been performed in

academic study centres by expert personnel trained for

the trial. Because these studies were mainly designed

to test the efcacy of such interventions, the interven-

tion programmes have been intensive. Due to the

limited resources of the public health sector, the

implementation of such intensive lifestyle modication

programmes in primary health care, i.e. in the setting

where most of the hypertensive patients are treated,

would be difcult. Therefore, we decided to conduct a

randomized, controlled trial to assess the efcacy of a

relatively low-intensity patient-counselling programme

planned for hypertensive subjects in primary health

care.

Methods

Participants and randomization

The Lifestyle Intervention against Hypertension in

Eastern Finland (LIHEF) study was conducted in 10

municipal primary health care centres in eastern Fin-

land, mainly in the province of North Karelia. Eight of

the health care centres were located in rural municipa-

lities with 300012 000 inhabitants and two in the

towns with 50 000 and 90 000 inhabitants (51% of all

participants). The study protocol was approved by the

Ethics Committee of the Kuopio University Hospital.

The study participants were enrolled between February

1996 and June 1997. Eligible subjects were men and

women aged 2574 years with systolic blood pressure

(SBP) 140179 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure

(DBP) 90109 mmHg or on antihypertensive drug

therapy. Exclusion criteria included secondary hyper-

tension, mental or physical illness serious enough to

potentially inuence the compliance with the study

procedures, alcoholism, type 1 diabetes, current or

planned pregnancy and history of myocardial infarction

or stroke within the preceding 3 months.

Three screening visits in 1-week intervals were orga-

nized in the health centres to measure the BP of the

subjects not using any antihypertensive drugs. During

each screening visit, BP was measured twice from the

right arm of the subject according to the WHO

MONICA protocol with a standard mercury sphygmo-

manometer [11]. The mean of the BP measurements

performed in the second and third visit (four readings)

was used as the screening BP.

The randomization visit was organized within 30 days

after the third screening visit in a participating health

centre. A written informed consent was obtained from

every eligible person agreeing to participate, after

which they were randomized to receive intervention or

usual care by the same study physician using a dice

(odd numbers intervention group; even numbers

control group). Of the 813 subjects originally eligible

for the study, 715 were eventually assigned to the

intervention group or to the usual care group.

Measurements

Blood pressure, weight, waist and hip circumferences

were measured annually from every participant. Height

was measured at the baseline only. Body mass index

(BMI) was calculated as kg/m

2

. During the annual

visits, BP was measured twice using the same method

as during the screening and the mean was used in the

analyses. A single trained study nurse, who was blinded

to the treatment assignment, performed most of the BP

and anthropometrical measurements during the screen-

ing and the follow-up. Only in one health centre with

176 participants, another trained study nurse carried out

the measurements during the screening and randomiza-

tion visits.

Information on socio-economic status, medical history,

smoking, alcohol use, physical activity and daily medi-

cation were collected annually using questionnaires

with standard questions. A 4-day food record was

collected for the annual visits. The detailed information

of the dietary analyses used in the study will be

published elsewhere [12].

All biochemical assays were performed at the Depart-

ment of Biochemistry of the National Public Health

Institute in Helsinki. Blood samples were drawn at the

participating health centres from the study subjects

after 12-h fasting. Serum total and high-density lipopro-

tein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides and insulin were

determined. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol

concentrations were calculated using Friedewalds for-

mula [13]. Twenty-four-hour urine specimens were

collected for the determination of the 24-h potassium

and sodium excretion.

Intervention

The intervention goals for the study subjects were: (1)

normal weight (BMI , 25 kg/m

2

); (2) daily sodium

chloride intake less than 5 g; (3) alcohol consumption

fewer than two drinks per day; (4) to exercise at

moderate intensity at least three times per week for

30 min; and (5) to stop smoking, if a smoker.

The study physician and a nutritionist trained the local

public health nurses who participated in the study. The

training sessions dealt with simple counselling and

behaviour modication methods targeting weight re-

duction, reduction in salt, alcohol and saturated fat

consumption, as well as an increase in leisure-time

physical activity. The nurses were given a folder with

2506 Journal of Hypertension 2002, Vol 20 No 12

detailed information of the dietary recommendations

and with practical tips to achieve these recommenda-

tions in everyday life.

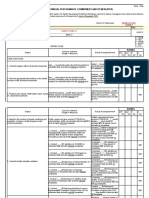

The core of the actual intervention (Fig. 1) consisted of

four visits by the participants to local public health

nurses during the rst year of the follow-up (1, 3, 6 and

9 months after randomization), and of three visits

during the second year (15, 18 and 21 months after the

randomization). At these visits, the participants were

systematically instructed to change their health behav-

iour primarily on the basis of their individual situation.

At each visit, BP and weight were measured, and the

values, as well as the changes in lifestyle factors to be

reached before the next study visit, were written down

using a special follow-up card designed for the study. A

written feedback of the 4-day food record was sent to

the public health nurse to support the intervention. In

addition, a 2-h group session was organized for the

intervention group in every health care centre at 6 and

18 months after the randomization. These two group

meetings concentrated mainly on advice targeting re-

duction of salt intake and overweight. During the 2-

year follow-up, the participants in the usual care group

were instructed to visit their own physicians and public

health nurses according to usual practices.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS for

Windows version 10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois,

USA). For continuous variables, the t-test was used to

test the differences and changes in mean values be-

tween the groups. Condence intervals (CI) for the

differences in proportions were calculated using a

special software package [14]. An intention-to-treat-

analysis was used, i.e. all subjects assigned to interven-

tion or usual care were included in the analysis. In the

case of missing responses, the last observed response

was used when calculating the 1- and 2-year changes in

continuous variables (the carry-forward method). The

same method was used with dichotomous variables. In

a separate analysis of BP changes in subjects without

previous antihypertensive drug treatment, the last BP

measurement without antihypertensive drug treatment

was used if drug treatment was initiated during the

trial. Accordingly, in subjects already on antihyperten-

sive medication, the last BP measurement with anti-

hypertensive drug treatment was used if the treatment

was discontinued during the trial. In the calculations of

BP changes, the changes in doses of antihypertensive

medication were not taken into account. Multiple linear

regression analysis was used to examine the associations

of changes in body weight, sodium and potassium

excretion, alcohol intake and leisure-time physical

activity (times/week) with the changes in BP, control-

ling for the baseline BP levels.

The original target sample size was 800 subjects, which

Follow-up,

Months

Randomisation

Measurements

at baseline,

12 months and

24 months:

PN, FFR

PN

PN,

GM

PN

FFR

PN PN,

GM

PN

Intervention

0 1 3 6 9 12 15 18 21 24

Usual care*

BP

Weight

Height (only at baseline)

Waist

Hip

Total cholesterol

HDL cholesterol

LDL cholesterol

Triglycerides

24-hour urinary sodium excretion

24-hour urinary potassium excretion

Insulin

Questionnaires

4-day Food record

Fig. 1

The design of the study. PN, public health nurse; FFR, feedback from the food record; GM, group meeting.

Usual care group visited their own

public health nurses as usual. BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Non-pharmacological treatment of hypertension Kastarinen et al. 2507

was not reached due to relatively numerous dropouts

before the randomization among the already recruited

subjects. It was estimated that this sample size would

enable detection of a 3.2 mmHg difference in change

of SBP and a 1.6 mmHg difference in change of DBP

between the intervention and usual care groups, with

80% power at the 5% signicance level.

Results

Baseline characteristics and adherence to treatment

The mean age of all participants was 54.3 years. Of the

participants, 52% were on antihypertensive drug treat-

ment at the beginning of the trial (Table 1). There

were no statistically signicant differences between the

groups in any of the baseline variables analysed.

Attendance rates at the 1-year and 2-year study visits

were satisfactory (Fig. 2). The attendance rate at both

group meetings organized for the intervention group

after 6 and 18 months of intervention was 50%. The

subjects who dropped out during the different phases

of the study were, at baseline measurements, signi-

cantly younger (50 versus 55 years) and heavier (83.1

versus 80.1 kg) compared with the attenders of the 2-

year visit. Also, alcohol use (73 versus 42 g/week) and

proportion of smokers (13 versus 7%) were signicantly

higher among the drop-outs at the baseline.

Changes in blood pressure and lifestyle factors

The changes in BP and other continuous variables in

the two groups are shown in Table 2. Without taking

into account the effect of antihypertensive drug treat-

ment, the reduction in DBP during the rst study year

was signicantly greater in the intervention group com-

pared to the usual care group. The reductions in SBP at

1-year follow-up and at 2-year follow-up and in DBP

from baseline to 2 years tended to be greater in the

intervention group, although they did not reach the

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of participants in the intervention and usual care groups. Values are mean

6SD or percentage

Intervention (n 360) Usual care (n 355)

Age (years) 54.4 10.1 54.2 9.9

Female (%) 52 54

Antihypertensive drug treatment (%) 52 53

Current smoker (%) 9 7

History of coronary heart disease (%) 5 3

Moderate physical activity at least three times per week (%) 51 51

Alcohol consumption (g/week) 47 83 48 74

Body weight (kg) 81.1 15.7 80.0 14.8

Body mass index (kg/m

2

) 28.9 4.6 28.5 4.5

Waist circumference (cm) 97.2 13.1 95.8 12.8

Hip circumference (cm) 104.7 10.4 104.1 10.0

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 149 16 148 16

No antihypertensive drug treatment 152 14 150 14

Antihypertensive drug treatment 147 18 146 18

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) 91 9 91 8

No antihypertensive drug treatment 93 8 93 9

Antihypertensive drug treatment 89 9 89 8

Total cholesterol (mmol/l) 5.66 0.91 5.59 0.93

LDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) 3.64 0.81 3.56 0.79

HDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) 1.32 0.33 1.36 0.38

Triglycerides (mmol/l) 1.56 1.01 1.49 1.00

24-h urinary sodium excretion (mmol) 146 56 142 56

24-h urinary potassium excretion (mmol) 83 27 83 28

Serum insulin (IU/l) 12.2 6.8 11.6 6.3

LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

813 eligible subjects after screening

98 declined to participate

715 randomized

Intervention

n 360

Usual care

n 355

Attended 1-year study visit

317/360 (88%)

Attended 1-year study visit

275/355 (77%)

Attended 2-year study visit

304/360 (84%)

Attended 2-year study visit

283/355 (80%)

Fig. 2

The numbers of participants involved throughout the trial.

2508 Journal of Hypertension 2002, Vol 20 No 12

level of statistical signicance. In the subgroup with no

antihypertensive drug treatment, the reductions in both

SBP and DBP were signicantly greater in the inter-

vention group compared with the usual care during

both the rst and the second year of follow-up (Table

3). In subjects with antihypertensive drug treatment at

baseline, the BP reductions were of the same magni-

tude in both groups. In these subjects, the number of

antihypertensive drugs used per patient did not change

signicantly in either of the randomized groups during

the follow-up. In both groups, 70% of the drug-treated

patients were on monotherapy at the end of the study.

Among the subjects with antihypertensive drug treat-

ment, the self-reported frequency of BP measurements

during the previous year decreased signicantly more

in the intervention group during the rst year (net

change 2.3 measurements/year; 95% CI, 4.3 to 0.3;

data not shown). Otherwise the number of BP measure-

ments did not differ signicantly between the groups

during any phase of the study.

The net reductions (intervention versus usual care) in

weight at 1 and 2 years of follow-up were signicant.

Eight per cent of the initially overweight participants

(BMI > 25 kg/m

2

) assigned to intervention had achie-

ved normal weight at the end of the trial, which was

signicantly more than that in the usual care group

(Table 4). Also, the waist and hip circumferences fell

signicantly more in the intervention group than in

usual care throughout the study. The changes in 24-h

urinary sodium and potassium excretion were small,

with no signicant differences between the groups.

Self-reported alcohol consumption fell signicantly

more during the rst study year in the intervention

group, but this difference disappeared during the

second year. Compared to the usual care group, a

signicantly larger proportion of the participants in the

intervention group had increased their physical activity

to the target level at both 1-year and 2-year visits.

The net reduction in weight between the randomized

groups was signicantly greater in subjects with no

antihypertensive drug treatment during the rst year

compared to the group with antihypertensive drug

treatment (1.5 versus 0.8 kg, P for the interaction

Table 2 Changes in continuous variables at 1 and 2 years in the intervention and usual care groups

Change 01 year Change 02 years Difference in change (95% CI) (intervention versus usual care)

Intervention Usual care Intervention Usual care 01 year 02 years

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 4.7 3.4 6.2 4.2 1.3 (3.2, 0.6) 2.0 (4.3, 0.3)

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) 4.0 2.4 4.3 3.2 1.6 (2.7, 0.6) 1.1 (2.4, 0.2)

Body weight (kg) 1.5 0.2 1.5 0.3 1.3 (1.7, 0.9) 1.2 (1.7, 0.7)

Waist circumference (cm) 1.2 0.3 1.2 0.2 1.5 (2.1, 1.0) 1.4 (2.0, 0.8)

Hip circumfererence (cm) 1.4 0.5 1.4 0.4 0.9 (1.4, 0.4) 0.9 (1.5, 0.4)

Alcohol consumption (g/week) 7 1 7 5 8 (15, 0) 2 (9, 5)

Total cholesterol (mmol/l) 0.05 0.03 0.03 0.07 0.02 (0.11, 0.06) 0.11 (0.20, 0.01)

LDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) 0.06 0.01 0.11 0.04 0.05 (0.12, 0.03) 0.15 (0.23, 0.05)

HDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) 0.02 0.01 0.10 0.07 0.01 (0.01, 0.04) 0.03 (0.00, 0.07)

Triglycerides (mmol/l) 0.03 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.03 (0.05, 0.12) 0.00 (0.09, 0.10)

Urinary sodium excretion (mmol/day) 9 6 7 2 3 (10, 5) 5 (14, 3)

Urinary potassium excretion (mmol/day) 1 1 3 1 0 (4, 4) 2 (2, 5)

Serum insulin (IU/l) 0.8 0.2 1.1 0.5 0.6 (1.2, 0.1) 0.6 (1.1, 0.1)

CI, condence interval; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

Table 3 Changes (95% CI in parentheses) in blood pressure levels stratied by antihypertensive drug treatment

status

No antihypertensive drug treatment Antihypertensive drug treatment

Intervention (n 175) Usual care (n 166) Intervention (n 185) Usual care (n 189)

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg)

Baseline mean 152 150 147 146

Change 01 year 3.0 (4.6, 1.4) 0.4 (1.8, 1.0) 4.8 (6.6, 2.9) 4.0 (5.9, 2.1)

Change 02 years 2.0 (3.7, 0.3) 0.4 (1.3, 2.0) 6.0 (8.5, 3.5) 4.7 (6.6, 2.6)

Net change 01 year 2.6 (4.7, 0.5) 0.8 (3.4, 1.9)

Net change 02 years 2.4 (4.7, 0.0) 1.3 (4.5, 1.8)

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg)

Baseline mean 93 93 89 89

Change 01 year 3.3 (4.3, 2.3) 0.6 (1.4, 0.3) 3.6 (4.6, 2.7) 2.8 (3.9, 1.7)

Change 02 years 2.4 (3.4, 1.4) 0.4 (1.4, 0.6) 3.8 (5.1, 2.6) 3.7 (4.9, 2.6)

Net change 01 year 2.7 (4.0, 1.4) 0.8 (2.3, 0.6)

Net change 02 years 2.0 (3.4, 0.6) 0.1 (1.8, 1.6)

CI, condence interval.

Non-pharmacological treatment of hypertension Kastarinen et al. 2509

term 0.021), but such a difference was not detected in

the analysis from baseline to 2 years. Similarly, the net

reductions in alcohol consumption from baseline to

1-year and 2-year visits were signicantly greater in

this group compared to the group with antihypertensive

drug treatment (from baseline to 1-year visit 17 versus

1 g/week, P for the interaction term 0.025; from base-

line to 2-year visit 9 versus 5 g/week, P for the

interaction term 0.029). The response for the interven-

tion in terms of lifestyle changes did not differ sig-

nicantly between the sexes or according to the

baseline age. In a multiple linear regression analysis, a

positive relation with 2-year change in blood pressure

was found for weight change in both subjects with no

antihypertensive drug treatment (SBP, P 0.003; DBP,

P , 0.001) and in drug-treated subjects (SBP, P

0.034; DBP, P 0.012), but not for the changes in

other lifestyle variables. In a separate analysis among

the subjects with no antihypertensive drug treatment,

adjusting for both BP and weight at baseline, the

estimated effect of the 1 kg weight lost at 2 years was a

reduction of 0.55 mmHg in SBP and of 0.50 mmHg in

DBP

Changes in other cardiovascular risk factors

After 2 years of intervention, the net changes in total

(0.10 mmol/l) and in LDL cholesterol (0.15 mmol/l)

were signicant in favour of the intervention group. Also,

in persons without lipid-lowering drug treatment during

the study, the net reductions in total cholesterol

(0.11 mmol/l; 95% CI 0.20 to 0.02) and in LDL

cholesterol (0.13 mmol/l; 95% CI 0.22 to 0.03) were

larger in the intervention group than in the control group

(data not shown). Smoking was already rare at baseline,

and no signicant changes in that habit were observed

during the study. The serum insulin concentration de-

creased more among the persons assigned to interven-

tion, but the net change was not statistically signicant.

Discussion

The lifestyle counselling provided in the LIHEF study

could produce a signicant reduction in BP level of the

subjects with no antihypertensive drug treatment com-

pared with usual care for 2 years. Weight loss was

signicantly greater in the intervention group at the 1-

year visit, and this difference was maintained during

the second year. The intervention programme could

not induce any signicant reductions in salt intake.

Despite the fact that in 95% of the participants the

weekly alcohol consumption was already at the recom-

mended level at baseline, a small but signicant reduc-

tion in alcohol intake occurred in the intervention

group during the rst year. The self-reported leisure-

time physical activity increased signicantly more in

the intervention group throughout the study.

Large-scale randomized trials reporting the effects of

lifestyle intervention on BP and other cardiovascular risk

factors in hypertensive persons in the primary care setting

are rare. The very few previous studies have included

relatively small numbers of patients, with the maximum

follow-up time of 12 months [1517]. Iso et al. [18]

reported that a community-based trial lowered BP among

hypertensive subjects. In their study, the intervention

was based mainly on group sessions instead of the

individualized health counselling used in our study.

The net changes in BP and lipid levels detected in our

study are in accordance with trials of multiple risk

factor intervention or dietary intervention with people

at high risk but not necessarily hypertensive [1921].

The reduction achieved in body weight after 2 years of

intervention was almost the same as in some trials with

more intensive intervention [1]. In contrast, the BP

reduction observed in the subjects without antihyper-

tensive drug treatment was smaller compared to some

clinical trials of non-pharmacological treatment of

hypertension [4,22]. These trials used very intensive

intervention compared to our study. Thus it seems that

at least some of the results obtained in high-intensity

intervention trials can be translated successfully to

primary health care.

According to the separate analysis of the dietary data of

Table 4 The percentage of participants reaching the pre-dened goals for the intervention during the trial among the persons out of goals

at baseline

Year 1 Year 2

Intervention

a

Usual care

a

Difference in

change (95% CI) Intervention Usual care

Difference in

change (95% CI)

BMI , 25 kg/m

2

7.8 (294) 3.9 (279) 3.9 (0.1, 7.7) 8.2 3.6 4.6 (1.0, 8.4)

> 5% reduction in BMI 18.7 9.3 9.4 (3.8, 15.0) 22.1 10.4 11.7 (5.8, 17.7)

24-hour U-Na excretion , 85 mmol 10.6 (301) 8.7 (286) 1.9 (2.9, 6.7) 7.0 7.0 0.0 (4.1, 4.1)

> 10% reduction in 24-h U-Na excretion 41.5 33.6 7.9 (0.2, 15.8) 41.5 33.6 7.9 (0.2, 15.8)

, 2 alcohol drinks per day 27.8 (18) 9.5 (21) 18.3 (6.0, 42.5) 16.7 9.5 7.1 (14.2, 28.5)

Recommended level of physical activity

b

34.7 (173) 24.0 (171) 10.7 (1.2, 20.3) 34.1 22.8 11.3 (1.8, 20.8)

Not smoking 6.5 (31) 12.0 (25) 5.6 (20.9, 9.9) 12.9 12.0 0.9 (16.5, 18.3)

CI, condence interval; BMI, body mass index; U-Na, urinary sodium.

a

Number of subjects out of each goal at baseline in parentheses.

b

Leisure-time physical activity at

least three times per week and at least to 30 minutes.

2510 Journal of Hypertension 2002, Vol 20 No 12

this study, the proportion of fat, and especially of

saturated fats, in total energy intake decreased signi-

cantly more in the intervention group compared to

usual care [12]. Also, the total energy intake tended to

decrease more in the intervention group, although not

reaching the level of statistical signicance. In addition

to the increase in physical activity, these changes in

diet may have contributed to the observed differences

in changes of body weight, lipid levels and BP between

the randomized groups. The dietary data were in

accordance with the results of the 24-h urinary sodium

excretion, showing no signicant changes in sodium

intake. These results repeat the ndings of the many

other studies that have demonstrated the difculties in

achieving the recommended level of salt intake in free-

living subjects [23,24]. It has been suggested that the

main reason for this difculty in salt restriction seen in

all Western countries is the still relatively high concen-

tration of salt in processed foods [25].

The differences in BP reduction observed between the

groups could not be explained by accustomization with

BP measurement, because there was not any difference

in self-reported frequency of BP measurements be-

tween the groups during the study. One explanation for

the greater fall in blood pressure among the participants

who continued antihypertensive drug treatment com-

pared with the participants without antihypertensive

drugs could be a more regular use of antihypertensive

drugs during the trial than before.

As usual in volunteer-based intervention studies, the

study sample is seldom fully representative of the back-

ground population. Highly motivated volunteers are

usually more susceptible to accept the recommended

intervention than the population at large. On the other

hand, many volunteers in lifestyle intervention studies

have already previously changed their lifestyle, which

could reduce the power of the intervention. In our study,

the mean BMI, total cholesterol and the prevalence of

smoking were lower than in Finnish hypertensive sub-

jects in the population-based FINRISK study in 1997

[2628]. The study participants also came from a

geographical area with a long history of cardiovascular

disease prevention activities, and thus many of them

already had a relatively good knowledge about lifestyle

factors affecting the cardiovascular risk [29]. In addition,

the contamination of the control group, due to the fact

that their follow-up visits were done by the same nurses

as with the intervention group, might have reduced the

difference in the lifestyle changes between the groups.

Also, the fact that they were under systematic observa-

tion in an interesting study likely inuenced them.

Thus, our observed effects of the intervention, as usual

in this kind of studies, are likely to be conservative.

In conclusion, the favourable changes in BP and other

cardiovascular disease risk factors in hypertensive per-

sons participating in our study were smaller than in the

trials with more intensive interventions. However, the

principal aim of this study was to nd out the extent to

which lifestyle intervention will work in the usual

primary health care setting. From this point of view,

our results were quite satisfactory, considering the

limited requirement for the use of health care re-

sources. The potential of the intervention shown in this

study can certainly be much improved by further

development and systematic dissemination, especially

concerning newly detected hypertensive persons. Non-

pharmacological treatment of hypertension has been

advocated for a long time, but so far only limited

evidence and experience has been available as to its

effective implementation within primary care. The task

is not easy, due to the limited time and resources that

the public health service can allocate for such preven-

tive services. However, we have shown that this

approach works.

Acknowledgements

The statistician Pirjo Halonen, MSc, advised M. Kastar-

inen about data analysis. Mr Veli Koistinen was respon-

sible for preparing the database. Study nurses Anneli

Mitrunen and Mari Aalto screened the study subjects

and performed BP and anthropometrical measurements.

Registered dietitians Sari Aalto and Sointu Lassila were

responsible for the training of nurses in dietary issues

and for the group sessions organized for subjects

assigned to intervention. We thank for the staff of the

North Karelia Project for the help given in coordination

of the study. Antti Jula MD, PhD; Antti Malmivaara,

MD, PhD; Matti Romo, MD, PhD; Jyrki Olkinuora,

MD, Markku Helio vaara, MD, PhD; Erkki Vartiainen,

MD, PhD and Timo Lakka, MD, PhD were members

of the LIHEF study group and helped in designing the

study. The authors are grateful to all practice staff

working in the participating health care centres, as well

as to the hypertensive persons participating the study.

References

1 Stevens VJ, Obarzanek E, Cook NR, Lee IM, Appel LJ, Smith West D,

et al. Long-term weight loss and changes in blood pressure: results of the

Trials of Hypertension Prevention, phase II. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134:

111.

2 Puddey IB, Beilin LJ, Vandongen R. Regular alcohol use raises blood

pressure in treated hypertensive subjects. A randomised controlled trial.

Lancet 1987; 1:647651.

3 Cutler JA, Follmann D, Allender PS. Randomised trials of sodium reduction:

an overview. Am J Clin Nutr 1997; 65 (suppl 2):643651.

4 Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Harsha D, et al.

Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary

Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASHSodium Colla-

borative Research Group. N Engl J Med 2001; 344:310.

5 Halbert JA, Silagy CA, Finucane P, Withers RT, Hamdorf PA, Andrews GR.

The effectiveness of exercise training in lowering blood pressure: a meta-

analysis of randomised controlled trials of 4 weeks or longer. J Hum

Hypertens 1997; 11:641649.

6 Neaton JD, Grimm RH Jr, Prineas RJ, Stamler J, Grandits GA, Elmer PJ,

et al. Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study. Final results. Treatment of

Mild Hypertension Study Research Group. JAMA 1993; 270:713724.

Non-pharmacological treatment of hypertension Kastarinen et al. 2511

7 Puska P, Iacono JM, Nissinen A, Korhonen HJ, Vartiainen E, Pietinen P,

et al. Controlled, randomised trial of the effect of dietary fat on blood

pressure. Lancet 1983; 1:15.

8 The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection,

evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med 1997;

157:24132446.

9 Guidelines Subcommittee.1999 World Health OrganizationInternational

Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension.

J Hypertens 1999; 17:151183.

10 Ramsay L, Williams B, Johnston G, MacGregor G, Poston L, Potter J, et al.

Guidelines for management of hypertension: report of the third working

party of the British Hypertension Society. J Hum Hypertens 1999;

13:569592.

11 Kuulasmaa K, Hense HW, Tolonen H for the WHO MONICA project.

Quality assessment of data on blood pressure in the WHO MONICA

project. http:www.ktl./publications/monica/bp/bpqa.htm. [Accessed 13

March 2002].

12 Korhonen M, Kastarinen M, Uusitupa M, Puska P, Nissinen A. The effect of

intensied diet counselling on the diet of hypertensive subjects in primary

health care. A 2-year open randomised controlled trial of lifestyle intervention

against hypertension in Eastern Finland (LIHEF). Prev Med 2002, (in press).

13 Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration

of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the

preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972; 18:499502.

14 Gardner M, Gardner S, Winter P. Condence interval analysis (CIA).

Microcomputer program manual. London: BMJ Publishing Group and MJ

Gardner; 1991.

15 Koopman H, Spreeuwenberg C, Westerman RF, Donker AJ. Dietary

treatment of patients with mild to moderate hypertension in a general

practice: a pilot intervention study (1). The rst three months. J Hum

Hypertens 1990; 4:368371.

16 Cohen MD, DAmico FJ, Merenstein JH. Weight reduction in obese

hypertensive patients. Fam Med 1991; 23:2528.

17 Woollard J, Beilin L, Lord T, Puddey I, MacAdam D, Rouse I. A controlled

trial of nurse counselling on lifestyle change for hypertensives treated in

general practice: preliminary results. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1995;

22:466468.

18 Iso H, Shimamoto T, Yokota K, Sankai T, Jacobs DR Jr, Komachi Y.

Community-based education classes for hypertension control. A 1.5-year

randomised controlled trial. Hypertension 1996; 27:968974.

19 Ebrahim S, Smith GD. Systematic review of randomised controlled trials of

multiple risk factor interventions for preventing coronary heart disease.

BMJ 1997; 314:16661674.

20 Brunner E, White I, Thorogood M, Bristow A, Curle D, Marmot M. Can

dietary interventions change diet and cardiovascular risk factors? A meta-

analysis of randomised controlled trials. Am J Public Health 1997;

87:14151422.

21 Steptoe A, Doherty S, Rink E, Kerry S, Kendrick T, Hilton S. Behavioural

counselling in general practice for the promotion of healthy behaviour

among adults at increased risk of coronary heart disease: randomised trial.

BMJ 1999; 319:943947.

22 Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, Applegate WB, Ettinger WH Jr,

Kostis JB, et al. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of

hypertension in older persons: a randomized controlled trial of non-

pharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE). TONE Collaborative

Research Group. JAMA 1998; 279 (11):839846.

23 Pietinen P, Tanskanen A, Nissinen A, Tuomilehto J, Puska P. Changes in

dietary habits and knowledge concerning salt during a community-based

prevention programme for hypertension. Ann Clin Res 1984; 16 (suppl

43):150155.

24 Evers SE, Bass M, Donner A, McWhinney IR. Lack of impact of salt

restriction advice on hypertensive patients. Prev Med 1987; 16:213220.

25 Kumanyika S. Behavioral aspects of intervention strategies to reduce

dietary sodium. Hypertension 1991; 17 (suppl 1):190195.

26 Kastarinen MJ, Nissinen AM, Vartiainen EA, Jousilahti PJ, Korhonen HJ,

Puska PM, et al. Blood pressure levels and obesity trends in hypertensive

and normotensive Finnish population from 1982 to 1997. J Hypertens

2000; 18:255262.

27 Kastarinen M, Tuomilehto J, Vartiainen E, Jousilahti P, Sundvall J, Puska P,

et al. Trends in lipid levels and hypercholesterolaemia in hypertensive and

normotensive Finnish adults from 1982 to 1997. J Intern Med 2000;

247:5362.

28 Kastarinen M, Tuomilehto J, Vartiainen E, Jousilahti P, Nissinen A, Puska P.

Smoking trends in hypertensive and normotensive Finns during 1982

1997. J Hum Hypertens 2002; 16:299303.

29 Puska P, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A, Vartiainen E. The North Karelia Project:

20-year results and experiences. Helsinki: National Public Health Institute;

1995.

2512 Journal of Hypertension 2002, Vol 20 No 12

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Learning DisabilityДокумент240 страницLearning DisabilityKUNNAMPALLIL GEJO JOHNОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Guide To: Raising DucksДокумент16 страницGuide To: Raising DucksNeil MenezesОценок пока нет

- OMFC Application RequirementsДокумент1 страницаOMFC Application RequirementshakimОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Investigation and Treatment of Surgical JaundiceДокумент38 страницInvestigation and Treatment of Surgical JaundiceUjas PatelОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Benign Paratesticlar Cyst - A Mysterical FindingДокумент2 страницыBenign Paratesticlar Cyst - A Mysterical FindingInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Health According To The Scriptures - Paul NisonДокумент306 страницHealth According To The Scriptures - Paul NisonJSonJudah100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Verbalizing Importance of Adequate Nutrition Feeds Self UnassistedДокумент2 страницыVerbalizing Importance of Adequate Nutrition Feeds Self UnassistedMasruri EfendyОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Occupational Health in Indonesia: Astrid Sulistomo Dep. of Community Medicine FmuiДокумент99 страницOccupational Health in Indonesia: Astrid Sulistomo Dep. of Community Medicine FmuiDea MaharaniОценок пока нет

- Bharat India: Extremely Bad Status of Testing & VaccinationДокумент308 страницBharat India: Extremely Bad Status of Testing & VaccinationP Eng Suraj SinghОценок пока нет

- Columbian Exchange Graphic OrganizerДокумент2 страницыColumbian Exchange Graphic Organizerapi-327452561100% (1)

- Radiographic InterpretationДокумент46 страницRadiographic InterpretationSanaFatimaОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- DCA and Avemar A Theoretical Protocol FoДокумент33 страницыDCA and Avemar A Theoretical Protocol FosiesmannОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- MSDS Jun-Air SJ-27FДокумент8 страницMSDS Jun-Air SJ-27FJuan Eduardo LoayzaОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Aioh Position Paper DPM jdk2gdДокумент26 страницAioh Position Paper DPM jdk2gdRichardОценок пока нет

- Neurogenic Shock in Critical Care NursingДокумент25 страницNeurogenic Shock in Critical Care Nursingnaqib25100% (4)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Crim 2 Assignment Title 8 of RPC Book 2Документ8 страницCrim 2 Assignment Title 8 of RPC Book 2Gio AvilaОценок пока нет

- Individual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledДокумент12 страницIndividual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledTiffanny Diane Agbayani RuedasОценок пока нет

- BehandlungskarteiДокумент2 страницыBehandlungskarteidenyse bakkerОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Millennials Generation's Role Is Questioned. How Does It Affect Life Aspects?Документ3 страницыMillennials Generation's Role Is Questioned. How Does It Affect Life Aspects?AjengОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- List of Medical SymptomsДокумент6 страницList of Medical SymptomsAndré Raffael MoellerОценок пока нет

- Malaria & Cerebral Malaria: Livia Hanisamurti, S.Ked 71 2018 045Документ40 страницMalaria & Cerebral Malaria: Livia Hanisamurti, S.Ked 71 2018 045Livia HanisamurtiОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Grape Growing in TennesseeДокумент28 страницGrape Growing in TennesseeDbaltОценок пока нет

- What Explains The Directionality of Flow in Health Care? Patients, Health Workers and Managerial Practices?Документ7 страницWhat Explains The Directionality of Flow in Health Care? Patients, Health Workers and Managerial Practices?Dancan OnyangoОценок пока нет

- Python Ieee Projects 2021 - 22 JPДокумент3 страницыPython Ieee Projects 2021 - 22 JPWebsoft Tech-HydОценок пока нет

- Lab 1: Food SpoilageДокумент15 страницLab 1: Food SpoilageAdibHelmi100% (2)

- Sodium+Bicarbonate Neo v2 0 PDFДокумент3 страницыSodium+Bicarbonate Neo v2 0 PDFApres SyahwaОценок пока нет

- EMOTIONS Are Metaphysical! - TriOriginДокумент1 страницаEMOTIONS Are Metaphysical! - TriOriginStellaEstel100% (2)

- An Overview of Mechanical Ventilation in The Intensive Care UnitДокумент9 страницAn Overview of Mechanical Ventilation in The Intensive Care UnitJaime Javier VegaОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Cyclooxygenase PathwayДокумент8 страницCyclooxygenase PathwayIradatullah SuyutiОценок пока нет

- Nguyen 2019Документ6 страницNguyen 2019ClintonОценок пока нет