Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

X. Fitzgerald Spohn

Загружено:

Marcel Popescu0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

37 просмотров5 страницX. Fitzgerald Spohn

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документX. Fitzgerald Spohn

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

37 просмотров5 страницX. Fitzgerald Spohn

Загружено:

Marcel PopescuX. Fitzgerald Spohn

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 5

preted, tbe property tax is the only local revenue source.

Sanders does not interpret the law that way. He

calls the property tax "regressive," and has proposed a

3 percent gross receipts tax on hotel bills and restaurant

meals. There is some question about whether the city

can legally impose this tax, and the proposal so enraged

the business establishment that it went out and hired a

California consultant firm to fight itwhich only added

to Sanders's anti-establishment appeal.

All this makes Sanders a slight favorite to beat Demo-

crat Judith Stephany and Republican James Gilson in the

March 1 election. The Democrats, though, have reason-

able hopes of forcing Sanders into a runoff, where they

think they can beat him. They have a good candidate in

Stephany, a 37-year-old liberal with no ties to the old

Paquette machine. She takes the race seriously enough

to have quit as minority leader of the State House of

Representatives to run against Sanders.

If Sanders wins, some of his supporters want him to

run for the U.S. Senate, and he has not discouraged their

talk. The next available Senate seat in Vermont will he

Democrat Patrick Leahy's in 1986. It is extraordinarily

unlikely that Sanders could get elected statewide, but by

running as a left-of-center independent he could con-

ceivably deliver the seat to a Republican. In the kind of

radical politics Sanders pursues, this result would be no

worse than the election of another Democrat.

But Sanders, even if re-elected, probably will not have

much impact outside Burlington. He disdains what little

nationwide Socialist movement there is (the Democratic

Socialists of America) for its gradualist philosophy and

its ties to the Democrahc Party. He prefers to make the

revolution in one city, fill the potholes, and keep the tax

rate down. All this may not be what Debs and Thomas

had in mind. But then, they never got elected.

JON MARGOLIS

Jon Margolis is a Washington correspondent for the

Chicago Tribune.

In a time of doubt, the Church turns to the Social Gospel.

PULPIT POLITICS

BY PATRICK GLYNN

W

HATEVER its consequences for the nation as a

whole, the debate over nuclear arms has become

a curiously pivotal event for the Roman Catholic

Church. Not since Humanae Vitaethe papal encycli-

cal prohibiting artificial contraception for Catholics

has an official Church pronouncement stirred as much

attention as the bishops' draft pastoral letter on nu-

clear war. But whereas the effect of Humanae Vitae in

1968 was to shatter the morale of the American

Church and undermine the authority of the bishops,

the current pastoral message is having the opposite

result. Clergy at all levels have been galvanized by the

antinuclear theme, and, dissent from the right notwith-

standing, the bishops are growing accustomed to the

warrnest praise from quarters that formerly proffered

only criticism and scorn.

Yet to see the pastoral letter solely as the product of

Church doctrine or everi of the bishops' strong personal

convictions would be misleading. Behind the hierarchy's

bold new stance on disarmament lies a series of institu-

tional changes that over the past fifteen years have

Patrick Glynn issenior editor

rary Studies.

of Contempo-

thrust politics more and more to the center of Catholic

life. The period since Pope Paul VI's pronouncement on

birth control has been marked by self-doubt and severe

dissension within the Church, Since 1966 the American

Church has lost over 11,000 priests and 35,000 sisters

through resignations; weekly Mass attendance has

dropped precipitously; and roughly four-fifths of Ameri-

can Catholics, according to polls taken by the National

Opinion Research Center, have found themselves at

odds with the Vatican on the birth control question.

Again and again, in the Catholic press and at public

meetings, clergy and lay Catholics have clashed bitterly

with the bishops on the issues of contraception, abor-

tion, divorce, the marriage of priests, and the ordination

of women. The revisions of canon law recently signed

by the Pope have done nothing to alter the fundamental

terms of this debate.

At the same time, there has been an enormous growth

in the portion of the Church's institutional resources

devoted to the concerns of social justice. Much of it dates

from 1967, the year before Humanae Vitae, when Pope

Paul issued his encyclical on third world development.

In its own way the 1967 document, Populorum Pro-

gressio, was nearly as controversial as Humanae Vitae. It

M A R C H 1 4 , 1 9 8 3 I !

chastised the wealthier nations for indifference to the

poorer, and blamed third world poverty on Western

exploitation. It was attacked vociferously by the Ameri-

can right. Populorum Progressio culminated a series of

encyclicals and council documentsPope John XXIII's

Mater et Magistra (1961) and Pacem in Terris (1963),

and Vatican Council II's Gaudium et Spes (1965)in

which the Vatican set forth a new political teaching

whose themes mirrored the mood of the era: a more

conciliatory attitude toward Communism, a new em-

phasis on peace and disarmament, a special sympathy

for the third world. To advance these interests, Paul

established a Pontifi-

cal Commission on

Justice and Peace to

oversee the develop-

ment of Church social

doctrine.

In a sense, Paul's

contrasting encyclicals

on birth control and

on the problems of

developing nations

have defined two

poles in American

Catholic life since the

late 1960s: the one a

source of dissension

and decay, the other a

stimulus to energetic

growth. At the same

time that parish insti-

tutions have withered

and local churches

and parochial schools

have experienced reli-

gious staff shortages,

the Church bureau-

cracy devoted to the

promotion of peace

and justice has dra-

matically expanded.

Altogether there has

been an enormous re-

direction of religious

energy into the secular realm, particularly on the part of

the clergy. For many clerics shaken by the changes of the

Council era, politics has provided what the Catholic

social scientist Russell Barta calls "a new apologetic"a

new message with which to rouse the faithful and

vindicate the Church in the modern world.

Hundreds of clerics and Church officials are now

professionally involved in Church-sponsored social ac-

tivism. Over the last ten years, about 90 percent of the

nation's Catholic religious orders and 60 percent of its

173 dioceses and archdioceses have established "peace

and justice commissions" of their own. Twenty years

ago such political involvement on the part of official

D R A WI N G BY VI \ T L A WR E N C E 1-O R I H [. M- , W K L T U B 1.1 C

Church personnel would have been inconceivable, ex-

cept in connection with matters such as federal aid to

parochial schools, where the interests of the Church

were directly at stake. To the degree that there was an

identifiably Catholic tradition of political activismthe

Catholic Worker movement, the liberal Catholic move-

ment in Chicagoit was initiated and sustained by lay

people, with only rare (and usually tacit) support from

certain hierarchs. Activism generally occurred outside

the official Church bureaucracy; it existed as a minor

countercurrent to the public stance of the Church,

which, because of its strong anti-Communist emphasis,

was generally seen as

conservative. Not that

the bishops were al-

ways conservative or

silent on political is-

sues; in 1919 Catholic

prelates outlined a so-

cial program calling

for child labor laws,

higher wages, social

insurance, and similar

reforms, and through-

out the twentieth cen-

tury the hierarchy re-

mained supportive of

unionism. But if these

positions never regis-

tered very strongly

in the public mind,

it was partly because

statements from the

bishops on politics

in any form were so

infrequent.

Nowadays, by con-

trast, it has become

routine for a Catholic

diocese to take public

stands and even lobby

on a whole range of

domestic and foreign

policy issuesevery-

thing from local con-

cerns, such as housing and rent control, to national

questions, such as U.S. aid to El Salvador and nuclear

disarmament. The more active diocesan commissions

employ full-time activistsas many as six to eight pro-

fessionalswho organize letter-writing campaigns, visit

members of Congress and state legislators, sponsor

demonstrations, and instruct local Catholics on the is-

sues. San Francisco's diocesan commission, one of the

most active, has a full-time staff of six and a budget this

year of $ 150,00045 percent from diocesan sources and

much of the rest from supporters of California's nuclear

freeze campaign.

In short, after two decades of change and inner tu-

T H H N li W R E P U B L I C

mult, it is the Church's politically oriented institutions

that have emerged the most vital and unscathed. The

resulting structural incentives have operated powerfully

on the bishops, since to speak on such matters as birth

control and priestly celibacy has been to risk a torrent of

abuse. In the attempt to gain the ear of clergy and laity

alike, it has proved infinitely more gratifying and pro-

ductive to turn to political themes.

The Catholic bishopsonce a conservative and gen-

erally sober lotnow find themselves willy-nilly in the

vanguard of half a dozen political movements. Since

1966, when they created the United States Catholic

Conference and hired a staff of policy analysts to grap-

ple officially with the secular realm, the bishops have

issued countless declarations on public policy topics:

pastoral letters, statements to the press. Congressional

testimony, lengthy policy analyses. These documents

make for curious reading, mixing a rather standard brew

of secular left-liberalism with the lofty moral rhetoric of

revealed religion: "The Church has a particular respon-

sibility to address the moral questions involved in the

issue of strip-mining." Or again: "As an advocate, the

Church should analyze housing needs in light of the

Gospel, make judgments and offer suggestions." It re-

quires perhaps more than an average grasp of religious

matters to discover what the Gospel has to say about

housing needs, but such, nonetheless, is the perspective

that the bishops offer. They are not above using their

formidable moral authority to drive home a narrowly

political point. Thus a plan of national health insurance

is urged upon us as a "moral necessity"; and with a

confidence reserved for Galbraithian economists and

Catholic prelates, the bishops assure the nation that

there is no necessary trade-off between inflation and

unemployment. At times the Church seems to be par-

ticularly far afield from its own concerns. There is a

lengthy treatise on the virtues of small family farms, a

passionate endorsement of the Panama Canal treaty,

and a document that insists on the rights of Palestinians

to reparations from Israel and a state of their own.

T

HE VAST MAJORITY of these statements are

drafted by the U.S.C.C.'s nine-member policy-

writing staff, but the bishops are aware of what is issued

under their imprimatur, and many have taken consider-

able pride in the progressive tenor of their pronounce-

ments. In 1976, after a particularly disastrous confer-

ence, where 1,300 Catholics convened by the bishops

voted resolutions calling for ordination of women, per-

mitting priests to marry, reinstatement for divorced

Catholics who have remarried, and determination of

conscience in birth control. Archbishop Joseph L.

Bernadin assured the National Catholic Reporter that "in

the area of social concerns" the bishops were "ahead of

the mainstream" of Catholics. "We've got the substance,

but not the style, maybe, to attract a larger audience,"

explained Bernadin, who was recently made a cardinal

and heads the committee that drafted the nuclear pas-

toral letter. "These things [the bishops' policy state-

ments] have to be written in a more popular style."

The draft pastoral letter has certainly succeeded in

attracting this larger audience. Until now, the bishops'

policy statements have gone generally unnoticed out-

side the Church, although that is not to say that they

have been without effect. The Catholic Church, for all its

recent divagations, is still an institution where official

documents mattereven if they matter somewhat in-

consistently. Thus Catholic activists who dismiss

Humanae Vitae out of hand will cite chapter and verse of

Populorum Progressio in support of their political activi-

ties. Populorum Progressio and similar statements have

played a critical role in legitimating social activism

within the institutional Church. (The 1968 statement of

the Latin American bishops at Medellin, Colombia, and

the 1971 declaration Justice in the World by the World

Synod of Bishops are also key documents for the activ-

ists.) Therein lies the real significance of the bishops'

nuclear pastoral message. Because of the general erosion

of authority within the Church, statements by bishops

these days are unlikely to change the minds of many lay

Catholics, but they can provide impetus for the commit-

ment of the Church's considerable resourcesmoral

and financialto particular political programs. Official

documents free clerics and Church professionals to act

politically, ostensibly on behalf of the Church.

N

UMEROUS CLERICS are already involved in anti-

nuclear activities, and many of them predict that

the bishops' letter, if approved in roughly its present

form, will open the floodgates to new involvement.

"There are a lot of staff people who would like to act on

these issues," explains Sister Valerie Heinonen, who

directs military affairs for the Interfaith Center for Cor-

porate Responsibility in New York. "But until there is a

formal statement, they can't act. People criticize them. If

they can go back to a formal statement, that's the end of

the argument."

Yet it is not clear how much thought bishops and

Church leaders have given to the broad social conse-

quences of their pronouncements on topics like nuclear

war. Thus far the most important practical effect of these

declarations has been to fan the fires of political activism

among clerics.

Many clerical activists approach politics with a naive

air of moral certitude and an irresponsible singleness of

purpose. Yet as the Church awakened to its new political

role, enormous institutional power fell into the hands of

these well-meaning but unworldly sisters and priests.

More and more religious communities have placed their

institutionally held stock portfolios at the service of

activist members, who have used them to put share-

holders' resolutions on corporate ballots. In the past year

ninety communities of sisters and priests have joined

forces with the Milwaukee diocese and with several

Protestant congregations to take action against nineteen

companies involved in defense work. The resolutions

M A K t H 14, I 9 K 3 13

are intended to force companies like General Electric

and AT&T to get out of the business of designing and

building nuclear weapons. Though none of the resolu-

tions is likely to succeed, millions of dollars of stock are

involved. Altogether the Interfaith Center for Corporate

Responsibility has about $8 billion in church-owned

shares, Protestant and Catholic, at its disposal for such

initiatives.

T

HE CLERICS directing the corporate responsibility

campaign are remarkably untroubled by the pros-

pect that their efforts could have a one-sided impact,

curtailing U.S. weapons production without affecting

similar cutbacks in the Soviet Union. They act with an

assurance that only the Holy Spirit should provide. "We

think if you have two countries, one atheistic and one

God-fearing," says Father Michael Crosby, a Franciscan

Capuchin who coordinates shareholder activity for the

National Catholic Coalition for Responsible Investment,

"and if the two are at the same point [as regards nuclear

armamentsj, the first step ought to be taken by the

Christian group. Faith is the ultimate rationale. We must

be the ones to take the concrete first step. What's

happening now in this country is no different from

what's happening in the atheistic country. We're the

ones who should be turning the other cheek."

To hear clerics like Father Crosby discuss these mat-

ters so simplistically is to long for the days of Wolsey

and Richelieu, when the Church's immense power fell

into the hands of men who, while ebulliently corrupt,

were nonetheless shrewd and prudent. In the new

Church the chief qualification for authority increasingly

seems to be laudable intentions and an uncanny ability

to read diplomacy and military policy directly from

Biblical parables. Yet the stance of perfect innocence is

not without its moral ironies. Thus a sister in Washing-

ton who coordinates political action for nuns can calmly

explain that the sisters' activities range "from the smash-

ing of warheads, to the pouring of blood, to a simple

presence," as though it were hard to imagine good

works taking any other form.

And always in the background are Church docu-

ments. "I don't see that we have much to worry about,"

says Sister Heinonen, "especially if we fall back on our

theological documents. For Roman Catholics it's easy to

pull out a whole bunch of documents about peace.

According to our statements, this is what we're sup-

posed to be doing."

In the end, the modern Church is faced with an almost

insuperable dilemma. The fact is that its traditional

teaching on sexual matters, and indeed on much of

private life, retains little popular appeal. Inevitably, it is

the "social Gospel" that proves most resonant for mod-

em Catholics. The Pope himself seems acutely con-

scious of this circumstance; though John Paul II dutifully

reiterates more traditional Church themes, it is the mes-

sage of justice and peace that electrifies his hearers. This

recurrent public emphasis on politics by the Pope and

the bishops is altering the nature of Catholic doctrine, if

not as it is technically expressed in official pronounce-

ments, at least as it lives in the minds of Church mem-

bers. For many Catholics today, religious feeling has

been redefined in political terms, and the very content of

moral life has changed: the old preoccupation with

scrupulous personal virtue has been replaced by a gen-

eralized sense of good intentions and series of impecca-

bly "virtuous" stances on public issues. Otherworldli-

ness has given way to utopianism; as a result, the

spiritual has come to be understood by many as some-

thing in opposition not so much to the profane world as

a whole as to the established political order. In such a

context, the "religious" approach to politics almost nec-

essarily takes the form of extremism. After all, what

makes a political position "religious," "Christian," or

"Catholic" is precisely its uncompromising purity of

intention, its vehemence, its unwillingness to accede to

the exigencies of the secular realm. And so friars today

awaken us to the sacred by demanding that we conduct

foreign policy according to the rules laid forth in the

Sermon on the Mount, and they use all the temporal

power at their disposal to see that we are forced to do so.

Catholicism is not alone in this development; but be-

cause of its enormous institutional powerit remains

the nation's largest denominationits inner shifts can

have significant consequences for all of us.

D

EFENDERS of the Church's social doctrine empha-

size that there is a great distance between the

Vatican's generalized statements on such topics as disar-

mament and the actual endorsement of specific policies;

but what characterizes the current clerical activism is

precisely the direct application of principle to practice.

Since the Church is for disarmament, one must favor the

freeze. Since the Church favors negotiations, one must

back SALT []. Since the Church backs peace, one must do

everything in one's power to prevent the manufacture of

nuclear weapons by U.S. companies. By consistently

failing to distinguish between general moral princi-

pleswith which we all agreeand specific applica-

tions of these principles, the bishops have opened the

way to a flood of naive activist initiatives whose long-

term consequences are difficult to predict.

Long ago, defending Catholicism's compatibility with

democracy, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote:

The Catholic priests in America have divided the intellec-

tual world into two parts: in the one they place the doctrines

of revealed religion, which they assent to without discus-

sion; in the other they leave those political truths which

they believe the Deity has left open to free inquiry. Thus the

Catholics of the United States are at the same time the most

submissive believers and the most independent citizens.

The situation described by Tocqueville has exactly re-

versed itself. Now many Catholics assent to political

"truths" without a second thought; it is the doctrines of

revealed religion that have become problematical.

1 4 r u t - : N E W R t r U B M C

Вам также может понравиться

- In Rome We Trust: The Rise of Catholics in American Political LifeОт EverandIn Rome We Trust: The Rise of Catholics in American Political LifeОценок пока нет

- CENTRAL AMERICA-Pentecostals 3 - September JLRДокумент11 страницCENTRAL AMERICA-Pentecostals 3 - September JLRJosé Luis RochaОценок пока нет

- The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape AmericaОт EverandThe Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (47)

- Disputed Lands The Rise of Pentecostalism in Latin AmericaДокумент10 страницDisputed Lands The Rise of Pentecostalism in Latin AmericaTommy BarqueroОценок пока нет

- Reclaiming Power in Congregational and Community Ministry: Creating Shared Power for Effective MinistryОт EverandReclaiming Power in Congregational and Community Ministry: Creating Shared Power for Effective MinistryОценок пока нет

- The Ambivalence of Catholic Politics in Latin America - Amy EdmondsДокумент18 страницThe Ambivalence of Catholic Politics in Latin America - Amy EdmondsKona BlackОценок пока нет

- California's Spiritual Frontiers: Religious Alternatives in Anglo-Protestantism, 1850-1910От EverandCalifornia's Spiritual Frontiers: Religious Alternatives in Anglo-Protestantism, 1850-1910Оценок пока нет

- None of The Above: Beliefs As 'Important' and Having A 'Significant Impact' On Their Lives, Were AlsoДокумент14 страницNone of The Above: Beliefs As 'Important' and Having A 'Significant Impact' On Their Lives, Were Alsoapi-26076820Оценок пока нет

- The Coming Catholic Church: How the Faithful Are Shaping a New American CatholicismОт EverandThe Coming Catholic Church: How the Faithful Are Shaping a New American CatholicismОценок пока нет

- New Age-Mary Jo AndersonДокумент46 страницNew Age-Mary Jo AndersonFrancis LoboОценок пока нет

- Church Leadership Challenges in the Twenty-First CenturyОт EverandChurch Leadership Challenges in the Twenty-First CenturyОценок пока нет

- Why The Catholic Church Is Losing Latin AmericaДокумент5 страницWhy The Catholic Church Is Losing Latin AmericaolegsoldatОценок пока нет

- Religious Influences On Voting Are Still Marked in FranceДокумент5 страницReligious Influences On Voting Are Still Marked in FranceRafidah El ZahrОценок пока нет

- Empowering the People of God: Catholic Action before and after Vatican IIОт EverandEmpowering the People of God: Catholic Action before and after Vatican IIОценок пока нет

- Church and StateДокумент21 страницаChurch and StateCandela Prieto SerresОценок пока нет

- Practicing Christians, Practical Atheists: How Cultural Liturgies and Everyday Social Practices Shape the Christian LifeОт EverandPracticing Christians, Practical Atheists: How Cultural Liturgies and Everyday Social Practices Shape the Christian LifeОценок пока нет

- Without Roots. Ratzinger's Letter To PeraДокумент16 страницWithout Roots. Ratzinger's Letter To Peraandreidirlau1Оценок пока нет

- Allen Ten Mega TrendsДокумент3 страницыAllen Ten Mega TrendsEdsyl John KhuОценок пока нет

- Politics and Piety: Baptist Social Reform in America, 1770–1860От EverandPolitics and Piety: Baptist Social Reform in America, 1770–1860Оценок пока нет

- Religious Aspects of La ViolenciaДокумент25 страницReligious Aspects of La ViolenciaDavidОценок пока нет

- The Church and The Abertura in BrazilДокумент32 страницыThe Church and The Abertura in BrazilMárcio MoraesОценок пока нет

- The Vocation of Christians in American Public LifeДокумент5 страницThe Vocation of Christians in American Public LifeJBSfanОценок пока нет

- The Smoke of Satan: How Corrupt and Cowardly Bishops Betrayed Christ, His Church, and the Faithful . . . and What Can Be Done About ItОт EverandThe Smoke of Satan: How Corrupt and Cowardly Bishops Betrayed Christ, His Church, and the Faithful . . . and What Can Be Done About ItРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Why Jewish Americans Has No Chief Rabbi Santa PedofiliaДокумент11 страницWhy Jewish Americans Has No Chief Rabbi Santa PedofiliaLuis MagalhaesОценок пока нет

- Guerrillas of Peace: Liberation Theology and the Central American RevolutionОт EverandGuerrillas of Peace: Liberation Theology and the Central American RevolutionОценок пока нет

- Pope Francis and AmericaДокумент3 страницыPope Francis and AmericaEC Pisano RiggioОценок пока нет

- A Perspective of Church in PoliticsДокумент6 страницA Perspective of Church in PoliticsJohn Bj TohОценок пока нет

- An Evil Law Against Freedom of ReligionДокумент3 страницыAn Evil Law Against Freedom of ReligionRafaelОценок пока нет

- Latino Catholicism: Transformation in America's Largest ChurchОт EverandLatino Catholicism: Transformation in America's Largest ChurchОценок пока нет

- One World ChurchДокумент10 страницOne World Churchitisme_angelaОценок пока нет

- Zilla - Evangelicals and Politics in BrazilДокумент34 страницыZilla - Evangelicals and Politics in BrazilCarlos Henrique SantanaОценок пока нет

- The Truth about Clergy Sexual Abuse: Clarifying the Facts and the CausesОт EverandThe Truth about Clergy Sexual Abuse: Clarifying the Facts and the CausesОценок пока нет

- Political Catholicism and Political Islam - SynopsisДокумент23 страницыPolitical Catholicism and Political Islam - SynopsisKhushboo KhannaОценок пока нет

- Saving Faith: Making Religious Pluralism an American Value at the Dawn of the Secular AgeОт EverandSaving Faith: Making Religious Pluralism an American Value at the Dawn of the Secular AgeОценок пока нет

- Despite The Pope's Resignation: Catholicism Is Neither A Corporation Nor A Social MovementДокумент4 страницыDespite The Pope's Resignation: Catholicism Is Neither A Corporation Nor A Social MovementDr. Wolfgang Battmann and Roland MaassОценок пока нет

- WATTERS Mary - Bolívar and The Church - CHR 21 (1935) 299-313Документ16 страницWATTERS Mary - Bolívar and The Church - CHR 21 (1935) 299-313jvpjulianusОценок пока нет

- Continental Ambitions: Roman Catholics in North America: The Colonial ExperienceОт EverandContinental Ambitions: Roman Catholics in North America: The Colonial ExperienceРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Cambridge University Press Journal of Latin American StudiesДокумент24 страницыCambridge University Press Journal of Latin American StudiesRoarrrrОценок пока нет

- Would A More Catholic United States BettДокумент13 страницWould A More Catholic United States BettbandarsОценок пока нет

- Piety and Public Funding: Evangelicals and the State in Modern AmericaОт EverandPiety and Public Funding: Evangelicals and the State in Modern AmericaОценок пока нет

- Ricardo Luis C. Angeles Jeanne Lao HI166 - AH A Paper On The Religious Context During The Marcos EraДокумент6 страницRicardo Luis C. Angeles Jeanne Lao HI166 - AH A Paper On The Religious Context During The Marcos EraJeanneОценок пока нет

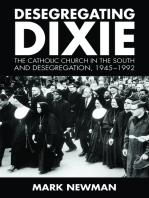

- Desegregating Dixie: The Catholic Church in the South and Desegregation, 1945-1992От EverandDesegregating Dixie: The Catholic Church in the South and Desegregation, 1945-1992Оценок пока нет

- Repair My House: Renewing The Roots of Religious LibertyДокумент45 страницRepair My House: Renewing The Roots of Religious LibertyRocco PalmoОценок пока нет

- Us Foreign Policy 1Документ9 страницUs Foreign Policy 1Arushi singhОценок пока нет

- The Last EnvoysДокумент119 страницThe Last EnvoysFran CummingsОценок пока нет

- Acta 38Документ47 страницActa 38SidneyОценок пока нет

- Integralism and The Brazilian Catholic ChurchДокумент23 страницыIntegralism and The Brazilian Catholic ChurchBetul OzsarОценок пока нет

- Address To The Greater Houston Ministerial Association: By: John F. KennedyДокумент2 страницыAddress To The Greater Houston Ministerial Association: By: John F. KennedyMОценок пока нет

- The Rise of The Catholic Alt-Right: Cite This PaperДокумент26 страницThe Rise of The Catholic Alt-Right: Cite This PaperRaceMoChridhe0% (1)

- The Dynamics Between Catholicism and Philippine SocietyДокумент5 страницThe Dynamics Between Catholicism and Philippine SocietyPaul Bryan100% (1)

- B. EbersoleДокумент14 страницB. EbersoleMarcel PopescuОценок пока нет

- 09 Young CH 09Документ22 страницы09 Young CH 09Marcel PopescuОценок пока нет

- The AwakeningДокумент5 страницThe AwakeningMarcel PopescuОценок пока нет

- 1957 - MACLEAN - The Heretic The Life and Times of Josip Broz Tito PDFДокумент455 страниц1957 - MACLEAN - The Heretic The Life and Times of Josip Broz Tito PDFmilan_ig81Оценок пока нет

- TitoДокумент4 страницыTitoMarcel PopescuОценок пока нет

- Business IT: Sve o Računarskom Oblaku: Karakteristike, Tipovi, Prednosti..Документ52 страницыBusiness IT: Sve o Računarskom Oblaku: Karakteristike, Tipovi, Prednosti..Sakura ShingoОценок пока нет

- OO. Christmas Wars 06Документ4 страницыOO. Christmas Wars 06Marcel PopescuОценок пока нет

- B. EbersoleДокумент14 страницB. EbersoleMarcel PopescuОценок пока нет

- I. OldmixenДокумент23 страницыI. OldmixenMarcel PopescuОценок пока нет

- Ar 2003Документ187 страницAr 2003Alberto ArrietaОценок пока нет

- Personal Philosophy of Education-Exemplar 1Документ2 страницыPersonal Philosophy of Education-Exemplar 1api-247024656Оценок пока нет

- Literature Review On Catfish ProductionДокумент5 страницLiterature Review On Catfish Productionafmzyodduapftb100% (1)

- Master Books ListДокумент32 страницыMaster Books ListfhaskellОценок пока нет

- Accountancy Department: Preliminary Examination in MANACO 1Документ3 страницыAccountancy Department: Preliminary Examination in MANACO 1Gracelle Mae Oraller0% (1)

- Screening: of Litsea Salicifolia (Dighloti) As A Mosquito RepellentДокумент20 страницScreening: of Litsea Salicifolia (Dighloti) As A Mosquito RepellentMarmish DebbarmaОценок пока нет

- Bagon-Taas Adventist Youth ConstitutionДокумент11 страницBagon-Taas Adventist Youth ConstitutionJoseph Joshua A. PaLaparОценок пока нет

- Some Problems in Determining The Origin of The Philippine Word Mutya' or Mutia'Документ34 страницыSome Problems in Determining The Origin of The Philippine Word Mutya' or Mutia'Irma ramosОценок пока нет

- Leisure TimeДокумент242 страницыLeisure TimeArdelean AndradaОценок пока нет

- Right Hand Man LyricsДокумент11 страницRight Hand Man LyricsSteph CollierОценок пока нет

- Contract of PledgeДокумент4 страницыContract of Pledgeshreya patilОценок пока нет

- Dan 440 Dace Art Lesson PlanДокумент4 страницыDan 440 Dace Art Lesson Planapi-298381373Оценок пока нет

- The Cognitive Enterprise For HCM in Retail Powered by Ibm and Oracle - 46027146USENДокумент29 страницThe Cognitive Enterprise For HCM in Retail Powered by Ibm and Oracle - 46027146USENByte MeОценок пока нет

- Erika Nuti Chrzsoloras Pewri Tou Basileos LogouДокумент31 страницаErika Nuti Chrzsoloras Pewri Tou Basileos Logouvizavi21Оценок пока нет

- Update UI Components With NavigationUIДокумент21 страницаUpdate UI Components With NavigationUISanjay PatelОценок пока нет

- Hibbeler, Mechanics of Materials-BendingДокумент63 страницыHibbeler, Mechanics of Materials-Bendingpoom2007Оценок пока нет

- Ma HakalaДокумент3 страницыMa HakalaDiana Marcela López CubillosОценок пока нет

- Storage Emulated 0 Android Data Com - Cv.docscanner Cache How-China-Engages-South-Asia-Themes-Partners-and-ToolsДокумент140 страницStorage Emulated 0 Android Data Com - Cv.docscanner Cache How-China-Engages-South-Asia-Themes-Partners-and-Toolsrahul kumarОценок пока нет

- Instructions: Reflect On The Topics That Were Previously Discussed. Write at Least Three (3) Things Per TopicДокумент2 страницыInstructions: Reflect On The Topics That Were Previously Discussed. Write at Least Three (3) Things Per TopicGuevarra KeithОценок пока нет

- Chapter 019Документ28 страницChapter 019Esteban Tabares GonzalezОценок пока нет

- CH Folk Media and HeatlhДокумент6 страницCH Folk Media and HeatlhRaghavendr KoreОценок пока нет

- SpellsДокумент86 страницSpellsGypsy580% (5)

- Sample Questions 2019Документ21 страницаSample Questions 2019kimwell samson100% (1)

- Ancestral Healing PrayersДокумент4 страницыAncestral Healing Prayerssuperhumannz100% (13)

- Capgras SyndromeДокумент4 страницыCapgras Syndromeapi-459379591Оценок пока нет

- Thesis Statement VampiresДокумент6 страницThesis Statement Vampireslaurasmithdesmoines100% (2)

- Management Strategy CH 2Документ37 страницManagement Strategy CH 2Meishera Panglipurjati SaragihОценок пока нет

- D8.1M 2007PV PDFДокумент5 страницD8.1M 2007PV PDFkhadtarpОценок пока нет

- Gits Systems Anaphy DisordersДокумент23 страницыGits Systems Anaphy DisordersIlawОценок пока нет

- Database Programming With SQL Section 2 QuizДокумент6 страницDatabase Programming With SQL Section 2 QuizJosé Obeniel LópezОценок пока нет