Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Standing Group On Organised Crime: Newsletter, May 2014, Volume 11, Issue 2

Загружено:

SGOCnetОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Standing Group On Organised Crime: Newsletter, May 2014, Volume 11, Issue 2

Загружено:

SGOCnetАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Standing Group on Organised Crime

Newsletter

May 2014

Volume 11, Issue 2

In ThIs Issue

In this issue

Editorial note

Getting ready for the ECPR

Conference in Glasgow

by FALKO A. ERNST and ANNASERGI (Editors)

Centre for Criminology, University of Essex

hese past months have produced ex- ticular, Romain Le Cour Grandmaison

citing results for the ECPR Standing and Tomas Ayuso both affiliated to the

Group on Organised Crime. Our section up- and coming Network for Researchers

at this years ECPR General Conference on International Affairs (NORIA, see box

in Glasgow is enjoying an historical pop- p.7) provide unique and empirically

ularity and we expect cutting-edge dis- based insights into what Latin American

organised crime looks like

cussion and debate. A

on the ground.Professor

new editorial project the

We look forward Simon Mackenzie shares

European Review of Orwith us what the University

ganised Crime has

to seeing you in

of Glasgows Trafficking

been launched and will

Glasgow in

Culture Project is all about

provide fresh perspecSeptember!

and what has been accomtives. Not least, the group

plished to date. Joe Mchas attracted funding for

nulty

takes

us

on

a set of three Summer

Schools on Organised Crime. The first uncharted depths with the niche topic of

group of students will arrive in Catania, organised crime in fisheries in the Pacific

Ocean.

Italy, at the end of June.

e are particularly proud of the present newsletter issue. Once again, it

brings together voices from across regions, disciplines and professions. In par-

ECPR General Conference

3 - 6 September 2014

University of Glasgow

#ecprconf14

e hope these contributions provide

you with as much inspiration as

they have to us and we look forward to

seeing you all in Glasgow!

Trafficking Culture.

Anatomy of a Statue Trafficking Network.

by Prof Simon Mackenzie

Page 2

The shifting landscape of Organized Crime in Honduras

by Tomas Ayuso

Page 4

Towards a 21st century Mexican para-militarism? The Michoacn crisis revisited

by Romain Le Cour Grandmaison

Page 6

Pacific Ocean fisheries and

the opportunities for transnational organised crime

by Joseph Mcnulty

Page 8

Miscellaneous

Page 10

photo:http://weegiehipstertipster.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/glasgow-uni1.jpg

ECPR Standing Group on Organised Crime

May 2014, Volume 11, Issue 2

Trafficking Culture.

Anatomy of a Statue Trafficking Network

by Simon Mackenzie

Simon Mackenzie is Professor of

Criminology, Law & Society at the University of Glasgow, and co-ordinator of

the Trafficking Culture research project

The Trafficking Culture project researches the international market in looted and

smuggled cultural objects. This is a damaging and under-acknowledged transnational criminal market, which takes cultural

objects such as antiquities (e.g. ancient

statues from temples, or valuable ancient

goods from tombs), rips them from their

archaeological context and trafficks them

from their home, which tends to be in the

developing world, to the rich marketplaces

in the global north and west (Brodie et al.

2001; Mackenzie 2005). There, they become transformed from illicitly obtained archaeologically-relevant national cultural

heritage into commodified art, sold to museums and private collectors for sums

which are regularly hundreds of thousands

of dollars, and sometimes millions. A particular recurring issue in the literature has

been whether there is an active role played by organised crime in this form of

transnational traffic.

Our overall research project has several components, with one strand being regional case studies of trafficking networks.

In 2013, I travelled to Cambodia with my

colleague Tess Davis to research the trafficking routes along which ancient Khmer

statues move out of the country. We explored the networks from the bottom-up,

beginning at major archaeological sites

that represented a wide spectrum of Cambodias ancient history, geography and

current development. We started our search for data in communities living around

temples, seeking out the oldest person in

the village or the person who knows stories about the village. In some cases, this

was the village or commune chief, or Buddhist monks or nuns. Some were able to

point us to people who had witnessed looting, or even been involved in it. Consultation with these individuals, especially

those who had taken statues and other

parts from temples, led to information

about who had organized the looting ventures and/or where the objects had gone.

This enabled us to move up the chain of

supply.

In overview, we have established a

picture of a funnelling network that took

statues from the various temples of Cambodia and passed them into a small number of channels that moved them by

oxcart, truck, and even elephant out of the

country and into Thailand. One of these

channels is indicated on the map below. It

operated from Cambodias northwest (including the sites of Angkor, Banteay

Chhmar, Koh Ker, and Phnom Banan)

through Sisophon, a town around 20km

from Thailand. From Sisophon, statues

went through Poipet on the Cambodian

side of the border to Aranyaprathet and Sa

Kaeo on the Thai side. From there it is a

straight drive up a main road to Bangkok

a journey that now can be made by car

in three hours. In this short article, we will

outline the roles played by key traffickers

working at the main points along this channel: at Koh Ker, in Sisophon, and in Aranyaprathet.

ECPR Standing Group on Organised Crime

May 2014, Volume 11, Issue 2

The research literature on trafficking in

a variety of illicit markets has often supported the flexible, informal, small scale trafficking model, somewhat in the face of an

entrenched policy discourse which constructs the threat of transnational organised crime in considerably more fixed,

structural, grand and opaque terms (Woodiwiss and Hobbs 2009). To what extent

are theoretical developments in analysis

of organised crime structural models applicable to the transnational illicit antiquities trade? We suggest that commonplace

claims about the eclipse of hierarchical organised crime enterprises by looser and

shifting networks may not be universally

accurate. Broadly stated, our conclusion

is that while the present case study is undoubtedly of a network, in which nodes,

contacts, and certain types of social capital are useful explanatory concepts, there

is also an observable stability, and identifiable forms of hierarchy, both along the

chain of the whole network and within

each of its nodes. We therefore conceptualise the network as a repetitive process,

having developed by way of linking nodal

actors in long-term trading relations, and

harnessing the benefits at different stages

in the chain of both localised territorial

structure-controlled organised crime (Lo

2010) and (as the trades move increasingly towards the transnational) more flexible entrepreneurial trafficker-dealers who

are less tied into frameworks involving territory or group.

The channel we identify here has four

major network nodes:

1.

A regional broker who organised the looting of statues at Koh Ker and

delivered them to Sisophon. The broker

would drive around the region in the morning, picking up willing participants for that

days looting. This node has elements of

hierarchy combined with a much more

fluid and opportunistic network-type structure at the lower end.

2.

Two organised criminals in Sisophon, who acted as the north-western hub

for Cambodian statue traffic, buying from

various regional brokers such as the one

at Koh Ker, and delivering the loot to the

border with Thailand, crossing at

Poipet/Aranyaprathet. The Sisophon dealers are remembered by locals as running

a wide range of illicit enterprises as well as

statue traffic, including drug smuggling

and prostitution, and as having a reputation for sometimes extreme violence. This

violence had been exercised against people who tried to circumvent the role of

these dealers in the supply chain.

3.

A receiver on the Thai side of the

border who would take delivery of the sta-

tues and move them to Bangkok. This occurred with military complicity and corruption.

An international-facing collector

4.

and dealer of statues in Bangkok, who

was the interface between the licit and illicit trades, filtering the objects into the global public market.

The structure of the network identified

here seems in some respects to support

Los (2010) arguments for a progression

adequately verify this pattern as being generally representative rather than just a regional historical observation.

Acknowledgement and further info

The research outlined above is in press

with the British Journal of Criminology, due

to be published mid-June 2014 under the title

Temple Looting in Cambodia: Anatomy of a

Statue Trafficking Network. The Trafficking

Culture project is funded by the European

Research Council under the European Unions Seventh Framework Programme

(FP7/2007-2013) / ERC Grant agreement n

283873 GTICO. The project website is

www.traffickingculture.org.

References

Professor Simon Mackenzie

(www.traffickingculture.org/people)

from theories of structure-control versus

social network towards a new social capital approach which he suggests can incorporate previous observations on group

and network, while also adding a layer of

explanation around political dynamics as

they support and affect the development

of social networks and organised crime.

However, there are also many elements of

the analysis which seem to continue to demand a more traditional structure-control

approach to explanation. Our research

has uncovered a trafficking channel that

was essentially fixed for several decades,

in terms of its roles, the occupants of those

roles, and their trading relationships.

Where occasionally an individual may

have tried to step outside of the norms of

this trafficking chain, they experienced

sanctions from the established hierarchy

which either quickly brought them back

into line or resulted in their being used as

examples to others not to try similar innovations. Based on this case study evidence, antiquities trafficking networks

might be thought of as more stable, hierarchical, and repetitively functioning supply chains than the highly fluid picture

which has been developed both in some

of the recent general organised crime literature, and in recent papers in the illicit antiquities sub-field. Clearly, much more

primary empiricism needs to be done to

Brodie, N., Doole, J. and Renfrew, C.

(eds) (2001) Trade in Illicit Antiquities: the

Destruction of the World's Archaeological

Heritage. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for

Archaeological Research.

Lo, T.W. (2010) 'Beyond Social Capital:

Triad Organized Crime in Hong Kong and

China', British Journal of Criminology, 50:

851-72.

Mackenzie, S. (2005) Going, Going,

Gone: Regulating the Market in Illicit Antiquities. Leicester: Institute of Art and Law

Woodiwiss, M. and Hobbs, D. (2009) 'Organized Evil and the Atlantic Alliance: Moral

Panics and the Rhetoric of Organized Crime

Policing in America and Britain', British Journal of Criminology, 49: 106-28.

THEECPR SGOC

Who is Who

Steering Committee 2012-2017

Convenor:

Felia Allum,

University of Bath

Co-convenor:

Francesca Longo,

University of Catania

Social Media Officer:

Bill Tupman, University of Exeter,

Anglia Ruskin University

Funding Officer:

Daniela Irrera

University of Catania

Events & Publication Officer:

Helena Carrapico,

University of Dundee

Strategic Communication:

Panos Kostakos,

University of Bath

Newsletter Editors:

Anna Sergi & Falko Ernst

University of Essex

European Review of Organised Crime

Felia Allum, University of Bath

Anita Lavorgna, University of Trento

Yuliya Zabyelina, University of Edinburgh

Member

Giap Parini

University of Calabria

ECPR Standing Group on Organised Crime

May 2013, Volume 11, Issue 2

The Shifting Landscape

of Organized Crime in Honduras

by Tomas Ayuso

Tomas Ayuso is a former Research

Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric

Affairs in Washington, DC. He specializes in organised crime, corruption

and post-conflict settings in the Balkans and Central America. He holds a

Masters Degree in Conflict and Security from the New School in New York

City.

In recent years the unenviable title for

world's most violent country has been a

one-continent-race: Latin America is riddled with countries that could fit that bill.

However, one country has risen as the

deadliest on account of a witches brew of

transnationalized street gangs, homegrown drug trafficking organizations

(DTO), entrepreneurial foreign hitmen,

and police who moonlight as DTO enforcers.

Honduras has developed an

ideal environment for the menagerie of

organized crime groups. The usual indicators that hobble many Latin American

countries, including increasing inequality,

poor infrastructure, and high unemployment, have as a backdrop the slow erosion of the already feeble Honduran

institutionalism. A 2009 coup which entailed debilitating political aftershocks was

followed by an influx of drug money consequent of being in the way of the ever

fluctuating northbound Andean cocaine

routes. Historically, the country had served as a stopover for the drug trade. However, the Mexican Drug War triggered

the alteration of the Americas main trafficking routes, forcing 80% of US-bound

cocaine to pass through Honduran territory.

The trafficking routes that also

overlap Guatemala and El Salvador

brought with them weapons, money, and

operational know-how significantly undermining the state's capacity to govern. Of

the three countries, Honduras has shouldered most of the burden due to its geographic position that juts out into the

Caribbean with a long coast and its heavy

mountainous and forested areas, providing organized crime groups with ideal

operational conditions. The situation is

high-ranking source inside the Honduran

Intelligence community expressed the

worrisome degree in which police and

local governments, particularly those in

areas vital to the drug trade, have been

so thoroughly corrupted.

Tomas Ayuso

made more attractive by the easily corruptible human element of an over-extended, unprofessional, and underpaid

security apparatus that is easily bribed

with impunity. In an interview with a person active in organized crime in the Honduran coast, it was stated that maritime

interdiction operations are futile as long

as there is enough money to pay off the

naval patrols. This source also described

how towns along the coast and other vital

trafficking hubs participate in the drug

trade in exchange for payment or services. These towns, many of which never

drew much attention from public or private investment, have welcomed the influx of drug trade related opportunities,

making organized crime as only game in

town.

The growth of the drug trade in Honduras has also seen the rise of foreign

trained gunmen and advisers in service of

domestic DTOs. Foreign enforcers from

Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela have

been apprehended throughout the country. They come to Honduras as hired guns

with a target. Some stay and pass their

professionalism and ruthlessness on to

locals. Among the many disenfranchised

and unemployed men who quickly join the

sicario (hitman) career path, it is the poorly funded police departments that have

been ransacked by DTOs who enlist

these disgruntled officers; a problem

which is being addressed albeit slowly. A

The State of the Barrio

The increased drug trade created new armed criminal groups, but in the

many urban neighborhoods known as

barrios there has been a war going on

between the many sealed off fiefdoms filled with young people ready to die to preserve their de facto autonomy. These are

aligned with one of the two major transnational youth gangs: MS13 or 18th street.

Originating in the urban environs of 1970s

Los Angeles, the gangs came to Central

America in the 1990s when President Bill

Clinton initiated a massive wave of deportations which included criminally radicalized gang members who were illegally in

the US. Upon their return they remade the

Honduran urban landscape into the

image of inner city LA. Their blood-soaked rivalry was also exported manifesting

itself in gruesome displays of cruelty and

violence against each other and terror for

the non-aligned citizens.

When the maras (as they are

known) first appeared, the state was unable to manage them. Ultimately, it counted

on their disappearance. Yet, their spread

was exacerbated when in 1998 Hurricane

Mitch leveled many densely populated

lower income barrios in Tegucigalpa and

San Pedro Sula. The destroyed barrios

full of recently deported and unemployed

blue collar citizens at a time in which the

state was completely overwhelmed and

underfunded, the maras stepped in to

take over these marginalized and devastated communities. Since then, many of

these neighborhoods have stayed in the

mara yolk. These barrios grow without

any urban planning or infrastructure development, are typically impoverished,

and dwell as far as can be from the state

in terms of governance. The maras understand these barrios as theirs, riddled

with safe houses to hold their wares and

weapons.

ECPR Standing Group on Organised Crime

May 2014 Volume 11, Issue 2

image source:www.rappler.com

They primarily fund their activities by

extracting wealth from the barrio through

extortion of local businesses; a practice

known as impuesto de guerra (war tax),

and more recently as the main vendors of

narcotics in the cities. Gangs occasionally

work with DTOs by serving as enforcers

and guarding shipments. Their pay is typically drugs.

Both gangs with ties to their regional counterparts, including those in the

US, receive their marching orders from

the overcrowded prisons that plague

Central America. In Honduras, incarcerated gang leaders order attacks to settle

scores against people who refuse to pay

their extortion fees or to eliminate threats.

Their blocks within the prison are effectively self-contained barrios themselves

virtually segregated from their rivals.

Each gang's own area is a reconstruction

of the outside barrios both in terms of aesthetics on the walls and the weapons

they hide inside. Now twenty years since

they first came on flights from LA, their

stranglehold over prisons and barrios has

yet to be countered by the state.

An Embattled State's Response

Current president, Juan Orlando

Hernndez, who prior to the 2013 election

served as Congressional President for

three years, spearheaded an initiative to

develop two different paramilitary units,

the Military Police and the counter-insurgency minded Tigres, as well as the formation of the FUSINA (Inter-institutional

National Security Force) task force to investigate and move against all organized

crime activity.

Although it is too soon to tell,

their results so far have been mixed. Successes attributed to them include the capture of Carlos Arnoldo Lobo, the pointman

for the Sinaloa Cartel in Honduras, which

has unleashed a low-intensity turf war

over Lobo's former territory. There has

also been arrests leading to the dismantling of gangs running extortion rackets

and targeted killings; namely cells of the

18th street gang in areas around San

Pedro Sula (SPS) who were alleged to

have been responsible for gruesome

massacres around the city.

The most pointed criticism is

aimed against the heightened militarization and zero tolerance approach that

has not yielded any significant improvements in terms of human security. While

it is true that since 2011, the most violent

year on record at 92 homicides per

100,000 inhabitants, the rate has slowed

to about 80 per 100,00 population in the

first quarter of 2014, the relentless fear of

extortion, intimidation and violence is still

a reality particularly in the urban centers

of Tegucigalpa and SPS. With the capture

of Chapo Guzman, head of the Sinaloa

cartel in Mexico and the extradition of

Lobo drug related homicides are expected to rise as a result of the turf wars and

the unseen consequences their absences

will have. Too little emphasis, however, is

being placed on preventative measures

within affected communities or towards

cleaning up infiltrated government structures.

A Self-Perpetuating Cycle

Honduras is a country in which

large swaths of territory both rural and

urban are completely out of state control,

with little efforts being made to bring

these areas back into the governance

fold. The introduction of two new armed

groups by the current government remain

to be proven as a deterrent in the face of

17.6 violent deaths per day. The shifting

drug routes were the cause for the increase in violence in 2009. Nonetheless,

this would not have been possible had it

not been for the unchecked corruption in

the security apparatus and elsewhere that

allowed DTO related violence to spiral out

of control. The youth gangs were emboldened by this shift and upped the brutality

of their rivalries, bringing more suffering

to the people effectively held captive in

their barrios.

With the inevitable fight over

turf coming as a consequence to the waning of the Mexican Drug War and the

capture of Lobo, the situation on the

ground is not likely to change in the short

term. The traditional sources of violence

like corruption, unemployment, poverty,

food insecurity, and others, which organized crime, both drug or gang related exploit, are simply not being worked on

enough to curb the violence. The current

government's focus on putting out fires

instead of taking aim at these root causes

of violence can only perpetuate the cycle

from which Honduras is unable to find any

reprieve from.

ECPR Standing Group on Organised Crime

January 2014, Volume 11, Issue1

Towards a 21st century Mexican para-militarism?

The Michoacn crisis revisited

by Romain Le Cour Grandmaison

Romain Le Cour Grandmaison is a

PhD Candidate at Sorbonne University

(Paris-1) and Co-President and Founder of Noria Research.

Ever since self-defense groups emerged as a response to state-organized

crime-collusion in February 2013, the western Mexican state of Michoacn has undergone

a

profound

political

reconfiguration. Armed groups have driven

this process and included diverse self-defense groups (autodefensas), cartels operating in the region, and a myriad of state

armed forces. The term reconfiguration

allows to understand the numerous dynamics at stake: 1. This process is relatively

recent and is evolving right before our

eyes; 2. What can be observed is a phase

of democratization of violence, as opposed to the near monopoly previously exerted by the Knight Templars Cartel

(Caballeros Templarios); 3. These ongoing

dynamics, even though they are very

much political in nature, are treated by the

federal government exclusively in terms of

violence, focusing solely on armed interlocutors; 4. This process of dialogue is characterized by instability, in a context where

all parties need each other, but do not trust

each other.

The Rise of the Self-Defense groups

and the Democratization of Violence

A process of political reconfiguration and democratization of violence, a

term I borrow from Paolo Pezzino, has followed the Templarios monopoly of violence. By democratization I mean that

violence, instead of being in the hands of

one entity, which ideally is public but in that

case property of a criminal group, becomes dispersed and used by various

groups against each other. In this particular instance we can identify three different

sets, assuming that they are homogenous:

the self-defense groups; the Templarios;

and (federal) state forces. This democratization provokes the confrontation of a multitude of interests, grouped under the

understanding that violence, and therefore

weapons, are the most important resource

for control of territory, social promotion,

conquest (or rather re-conquest) of political power and control of illegal trade (production and transportation of drugs, as

Romain Le Cour Grandmaison

well as illegal extraction and export of minerals). It is worth noting that these objectives are in no way mutually exclusive,

quite the opposite.

In Michoacn, the prime political

recourse is violence. This is not a recent

phenomenon but a product of decadeslong sociopolitical dynamics. One of the

governments main mistakes has been to

analyze the crisis in terms of a simple

armed conflict opposing two sides, and to

believe that it would be sufficient to pick

and support one side in order to defeat the

other. Yet, it is essential to understand the

role violence occupies within the regions

political system. When leaders of self-defense groups declare that they had not

other choice but to take up arms, they are

merely expressing what has been standard operating procedure in the region for

decades: if you do not engage in the physical or symbolic use of violence, you will

not control Michoacn. This dogma is shared just as much by the government, federal and state, by way of military campaigns

or dirty war, as well as by informal power

holders such as local caciques or drug traffickers.

For several months the public debate

about the self-defense groups has tried to

identify such a thing as their essence: who

are they? Where do they come from? Are

they like the Colombian paramilitaries?

How are we going to control them? These

questions were filling Mexican and international news columns, feeding what Carlos

Monsivais dubbed the interpretive

feast(1). In the meantime, the federal government chose not to follow the same

path by taking a more pragmatic posture.

So much so, that when traveling through

Tierra Caliente, it is not uncommon to hear

people say that the self-defense groups

were made by the Federal government.

Even though it might seem difficult to

share this point of view, my interlocutors

introduced a seldom analyzed aspect: the

instrumentalization and co-option of the

armed movement by the Federal government, as well as the rewards achieved

through the self-defense groups, who deeply know and understand their own society

and people operate. Even more important

is their extensive knowledge of Michoacns back roads, country, trenches, sierras and caves, none of which Federal

forces had been able and/or unwilling to

cover during their previous security operations in Michoacn. In such a situation, the

autodefensas became a crucial ally, albeit

one likely to disappear in case of a breakup among these actors.

The Actors' Fragmentation.

Yet, this conjectural convergence

of interests did not clarify the situation on

the ground. In addition to being extremely

divided, the self-defense groups have

never managed to transform their armed

success into a clear political process. Perhaps this never was their intention. Or perhaps since the Federal government would

not have it. In any case, their leaders did

not necessarily know or want to address

these types of dynamics and expectations

of locals. Even though the liberation of a

municipality should technically trigger the

automatic creation of an autonomous citizens council tasked with dealing with political issues, this process has become

bogged down mainly because the self-defense groups are in no way a homogenous

group.

Numerous internal and external dynamics underpin the autodefensas fragmentation. Internally, a great variety in

motivations guides these groups leaders.

It is not groundbreaking to claim that some

groups show a striking similarity, in appearance and in practice, to groups nominally

labeled criminal.

Some members trajectories prior to

their enrollment raise, carefully phrased,

doubts. Some might simply have switches

sides.

ECPR Standing Group on Organised Crime

January 2014, Volume 11, Issue 1

Yet, the issue is easily reduced to a

normative reading, ignoring the sociological processes at stake. The question is not

whether former Templars have integrated

the ranks of self-defense groups. This is

obvious. But this is not directly related to

this new armed movement, which must be

seen as a product of deeply rooted societal dynamics. When the region was under

Templario rule, many people worked in

one way or another for them. Sometimes

they had a brother, a cousin or a father

who had dealings with them. This does not

imply that Michoacn has been criminalized per se, but rather that a criminal group

who acted like the state for several years

made it impossible for regular people to

avoid contact with them. It is clear that

being a criminal organization's soldier, a

lookout or having to rely on the Templarios

to settle a spousal dispute does not constitute the same social involvement. However, once the self-defense groups made

themselves known, these distinctions lost

their clarity. As in every process of libera-

tion there are those who collaborated with

the old regime and the question arises on

what has to be done with them. In the present case, the answer was simply to

ignore the question and carry on.

As we have already mentioned,

many who expressed regret signed up

for roles in self-defense groups. This reveals a system of social capital and promotion based on violence or, at the very least,

on carrying a weapon. By moving past the

ongoing debate over the weapons of the

self-defense groups (How did they get

their weapons? Where do they come

from? How are they being paid for? Who

is paying for them?) we find the more important question: What is happening and

what is going to happen with so many high

caliber weapons in such a small area? The

debate has thus to be taken past the cultural reductionism that postulates a specific kind of violent Michoacn state of

mind(2). The fact that a fourteen-year-old

boy mans a checkpoint, or gets to eat at a

street-cart carrying an assault rifle is deeply problematic and unveils that violence

is a social opportunity. The self-defense

groups have mobilized an entire population to obtain their coercive potential. The

true issue is, however, if the state could

have responded better to these dynamics

by offering something other than weapons

to this arising form of resistance. A longterm oriented political and social planning

would have been necessary. Under the

given conditions, however, the consequences of the renewed and state-sponsored

proliferation of weapons will undoubtedly

constitute a lasting issue for Michoacn.

Endnotes

(1) MONSIVAIS, Carlos, Fuegos de

nota roja, Nexos, Agosto 1992.

(2) Such culturalist theory is still widely

present in the Mexican society, as well as

in the literature, refering to Michoacn as

bronco (rough).

Noria is a Think Tank based on a

network of researchers and analysts,

promoting the work of a new generation of specialists in international politics.

Founded in 2011, Noria aims at

providing a pertinent and in-depth perspective on the changing nature of the

international landscape and a new approach to understanding and analysing

international issues.

Norias approach is based on three

fundamental principles:

Intellectual independence

Scientific rigour

Linguistic and field expertise

image source www.cwu.edu

As of today, Noria brings together

researchers working on Ukraine, Russia, Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, Palestine,

Jordan, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, India,

Pakistan, China, Libya, Egypt, Mali,

Cameroon, Ethiopia, Colombia, Venezuela, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico.

ECPR Standing Group on Organised Crim

May 2014, Volume 11, Issue2

Pacific Ocean fisheries and the opportunities

for transnational organised crime

by Joseph Mcnulty

Joe Mcnulty is Inspector of the Marine Area Command of the New South

Wales Police Force and Honorary Fellow at the Australian National Centre

for Ocean Resources and Security

(ANCORS), University of Wollongong.

Introduction

The Pacific Ocean is the largest

Ocean on the planet. It covers 45% of the

Earths surface and geographically connects Russia and Asia with Australia in

the South Western Pacific, the Pacific Island Nations and connects with North and

South America. The Pacific Ocean has

experienced World Wars, trade embargoes and environmental disasters, yet nothing has prepared it for the future threat

of organised, transnational fisheries crime

and the gaps in law enforcement capability.

Organised Crime in Fisheries

Why is organised crime involved in fisheries? The main motivation for organised crime in fisheries is profit. Fisheries

are a highly globalised industry. Fish

caught in one ocean is transported and

consumed by people in another region of

the world. Fishing vessels freely transit

the worlds oceans and ports. The transnational mobility of fishing vessels creates opportunities for criminal activities and

the commodities can be transported over

long distances with little or no interference

from law enforcement agencies.1 Organised crime takes advantage of vulnerabilities and opportunities in fisheries

operations and thrives in areas with inadequate Monitoring Control and Surveillance (MCS) operations. We should not

underestimate the capabilities of transnational organised crime syndicates. They

have structures, systems, communications, hierarchy and financial controls placed around their illegal operations,

estimate risk in their operations and

hedge against movements in illicit commodities. Organised crime can be defined

as, criminal groups or a syndication of

groups acting for a period of time in unison with the aim to commit one or more

serious crimes or offences in order to obtain, directly or indirectly a financial or material benefit.2 Successful organised

in the Pacific ocean of 1.2 million tons is

taken through illegal means, a possible

US$276 million dollars worth of return

may be considered lost or stolen each

year. This is a great loss of revenue for

Pacific Island economies, which governments and islanders rely on as means

of livelihood and for food security. 4 This

demonstrates that organised crime not

only negatively affects returns from these

resources but also largely impact community benefits.

Joseph Mcnulty

crime groups operate across many sector

and crime types. They are likely to operate across national borders and including

being based offshore and connected to

offshore criminal groups.

They will have the ability to operate in

several illicit markets and between criminal activities.3 Organised crime successfully operates in economies and markets

where:

Law enforcement environments

are under resourced, over committed,

lack capacity and geographically challenged.

Operate in jurisdictions that lack

strong legal systems and capability to

prosecute fisheries offenders.

Fishing operations and interests

are not publically visible.

Government systems are susceptible to corruption.

Illegal fishing and transhipment practices are hard to estimate. There are similarities in attempting to estimate the

quantity of narcotics transported and distributed through organised crime syndicates with that of assessing the volume

and value of fish trafficked by organised

criminal groups. The return for organised

crime syndicates and business on the exchange of both these commodities is financial revenue. If 10% of skipjack catch

Organised crime is motivated by the

opportunity of large profits generated

from illegal activities. Organised crime

identifies opportunities where it can operate preferably unimpeded by law enforcement. The illegal business structure,

that does not have to conform to any business or corporate practices, or governmental regulations, designs its own

practices to infiltrate susceptible and/or

vulnerable economies. Once business

operations have commenced in this environment, the tentacles of illegal activity

spreads, and can become established within these communities and economies.

Law enforcement practices are generally

reactive; this is usually as a result of other

operational priorities and commitments.

Directing proactive Police resources at a

new, developing crime threat is often laboured in bureaucracy and therefore slow

to respond to emerging crime threats.

This is not an uncommon phenomenon to

policing organisations and is universally

experienced in different jurisdictions. The

Pacific Island National Police Forces, already geographically challenged by large

EEZs, isolated island groups, and large

archipelagos and with very limited and

often stretched resources will find fisheries crime threat difficult to respond to.

The Pacific Island States and Territories cover millions of nautical miles of

ocean and are geographically located

between Asia in the East, Australia and

New Zealand to the south and the Americas to the east.

These States and Territories have unique national identities and vary in legal

and judicial systems, population and culture, and law enforcement capacities.

ECPR Standing Group on Organised Crime

May 2014, Volume 11, Issue 2

Due to geographical locations, political systems, infrastructure and development, the Pacific Islands are vulnerable

to the activities of organised crime and its

criminal syndicates. The Pacific Islands

are located along a maritime corridor necessary for legitimate trade that transits

between major economic markets located

along the Pacific Rim.

Populating this surface picture of the

Pacific Ocean one can examine the many

difficulties in applying regulation and enforcement strategies to the multitude of fishing vessels, flying various State flags,

owned by various foreign companies, crewed by multinational crews, and all transiting through the Pacific Island EEZs and

high seas pockets. The majority of the fishing vessels are conducting legitimate fishing operations. However a number of

vessels engage in IUU fishing activities

and unauthorised transhipment operations. The diversity of these economic activities and lack of effective enforcement

present

a rich

smorgasbord of

opportunities for

transnational

organis e d

crime to

thrive

and prosper in

such an

appetite

rich environment.

Law enforcement responses are severely

challenged in such a large ocean area. Is

organised crime in offshore fisheries too

difficult to contemplate? How do we address this problem given that Pacific Island law enforcement agencies are

already stretched with meeting their current obligations against criminal activities

on land territories? Since little is known

on the precise nature of organised crime

in fisheries, can we consider the out of

sight, hence out of mind?

In 2009, the estimated average annual IUU catch in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (of which a vast

majority of catch is taken in and around

the waters of the FFA member countries)

was between 786,000t and 1,730,000t

(valued between USD707m and

USD1557m). 5 This represents a consi-

derable amount of lost revenue to member countries and is one of the reasons

why effective licensing system was considered essential for the financial sustainability of some Pacific Island Nations.6

Combating Illegal Transhipment Operations and Suspicious Vessel Tracks

Observations made during the MCS

operation illustrated various irregular fishing vessel movements in the area of

operation. After further analysis of these

movements, the irregular navigation patterns of fishing vessels made very little logistical or operational sense and hence

resulted in further interrogation of anomalies and vessel algorithms with the objective of identifying threat trends of

suspicious foreign fishing vessel tracks.

Operational assumptions based on

these suspicious patterns illustrated certain suspicious linkages and contact with

other vessels. By identifying irregular navigation patterns, analysts are now in a

position to share this intelligence with

strategies.

Upon inspection of another vessel,

the author investigated opportunities that

existed for the vessel to be engaged in organised and transnational crime.

The boarding and inspection of compliant foreign long line fishing vessels in

the Port of Honiara highlighted these

complexities. Onboard one vessel, the

crew were asked to identify their nationalities. The vessel crew was made up of Indonesians, Fijians, Filipinos and

Taiwanese; widening the nationality networks from the Pacific to South East and

North East Asia. If this vessel had been

engaged in transnational organised

crime, the crew connections would greatly

aid the facilitation and distribution of illegal commodities.

Most law enforcement agencies in the

Pacific Island States and Territories operate in relative geographical isolation with

limited resources and obsolete legislation

and procedures specifically drafted to

combat and regulate domestic criminal

activity. This is in contrast to organised

criminal groups, which are often well resourced and have networks across the

globe.

Pacific Island nations will have to

strengthen their maritime law and fisheries enforcement programmes in order to

address this new challenge in fisheries.

Each nation will need to consider their

strategic directions to preserve their natural fisheries and ensure fishery sustainability for the present and future

generations of their communities.

other law enforcement agencies. In the

event maritime intelligence and vessel

data can be processed, fused and analysed in a timely manner, it will provide enforcement agencies with high levels of

collaborative intelligence which correctly

utilised, will provide opportunities to disrupt and potentially dismantle organised

crime syndicates using fishing vessels.

Any vessel suspected of engaging in

IUU fishing activities or other forms of

transnational organised criminal activities

should undergo a thorough port inspection and search by either Police and/or

Customs officers. These opportunities are

essential for these Enforcement Officers

to identify and develop their intelligence

capabilities and to build awareness of the

threats and examine procedures to investigate and implement early intervention

ENDNOTES

1 UNODC, Transnational Organized Crime

in the Fishing

Industry, United Nations, Vienna 2011, p.

139.

2 United Nations Office on Drugs and

Crime, United Nations Convention Against

Transnational Organized Crime and the Protocols Thereto, United Nations New York, 2004,

<www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNTOC/

Publications/TO C%20Convention/TOCebooke.pdf>.

3 Australian Crime Commission, Organised Crime in Australia, 2009, pp. 5-13.

<www.crimecommission.gov.au>.

4 Forum Fisheries Agency, FFA members

meet to discuss tools for illegal fishing, 29

March 2010. <www.ffa.int/node/320>.

5 D J Agnew, J Pearce, G Pramod, T Peatman, R Watson, J R

Beddington and T Pitcher, Estimating the

Worldwide Extentof Illegal Fishing. PLoS ONE

4

(2)

2009:

e4570.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004570

6 Pacific Islands Forum Fishing Agency,

<www.ffa.int>.

1010

ECPRECPR

Standing

Group

on Organised

Crime

Standing

Group

on Organised

Crime

Volume

11, Issue

2 3

May 2014,

2013,

Volume

10, Issue

September

MISCELLANEOUS

The European Review of Organised Crime

The SGOC is delighted to announce

the release of the inaugural issue of its

own online open-access peer-reviewed

journal The European Review of Organised Crime (EROC) forthcoming in midJune. EROC has been on the SGOCs

agenda since its inception in 2001, but it

was only after more than a decade of yearly meetings that the SGOC was able to

consolidate its forces to launch its own

journal.

EROCs main aim is to offer a forum

for the study of organised crime in its different manifestations and to promote a

dialogue between the academic community and practitioners. The journals unique feature is that it will be free for

authors to publish and free for readers to

access. We are also dedicated to publishing articles rapidly upon submission

and actively seeking manuscripts from

early career professionals and non-native

speakers of English. Furthermore, we

have adopted a rolling deadline structure

for submissions in order to maximise the

we have started collecting papers for

EROCs second issue to be released in

fall 2014. We invite theoretical and empirical contributions on organised crime

broadly conceived from a variety of disciplines, such as criminology, criminal justice, political science, law, security

studies, sociology, gender studies, economics, media studies, anthropology, and

history. Contributions from practitioners

who can share knowledge about organised crime by drawing upon their on-theground experience are also welcome.

For further information, please visit

our website at

http://www.sgocnet.org/index.php/the-european-review-of-organised-crime

potential of our digital platform and hope

to publish accepted manuscripts with a

six-month period from the date of receipt.

or contact the editorial team at european.review.oc(at)gmail.com.

Having completed EROCs first issue,

Intensive Summer School on Serious and Organized Crime

23 June - 5 July 2014

Department of Political and Social Studies - University of Catania

Hosted and directed by:

University of Catania

Supported by:

EU Commission Lifelong Learning

Program; ECPR; Standing Group on Organised Crime

Partner Universities:

University of Bath, UK; Masaryk University, Czech Republic; Nicolaus Copernicus University, Poland.

ISSOC PROGRAMME COMMITTEE

Daniela Irrera and Francesca Longo

(ISSOC Directors, University of Catania);

Felia Allum (University of Bath, UK); Janusz Bojarski (Nicolaus Copernicus University, Torun); Pavel Peseja and Petr

Kupka (Masaryk University, Brno, Czech

Republic).

Target Audience

The Intensive Summer School on Serious and Organised Crime (ISSOC) is an

advanced and high quality training pro-

gramme offered to Masters students (enrolled in partner universities course)

eager to promote the study and discussion on the topic of serious and organised

crime and to the shifting challenges regarding its prevention. This project will be

particularly focused on the relevance of

the European financial and economic crises on the criminal activities and on the

ways the EU tackles it.

ISSOC is addressed to a specific target group made up of excellent students

enrolled in masters programmes on topics related to European and International

studies, though it focuses on themes not

covered by home Masters programmes

Objectives

The Summer School has selected

among a list of specific thematic focuses,

namely:

Methodological issues: how to

research serious and organised crime in

Social and Juridical Science?

The governance of serious and

organised crime at EU level in the crisis

time: a common policy in the making?

Serious and organised crime as

a security threat: the impact and implications of the crime-terror nexus.

Organised and Economic crime:

Focus on financial crime and related offences money laundering, financial crimes and white-collar crime, links between

legal and illegal business

Main activities:

1.

theoretical-academic lectures by

an international team of scholars;

2.

presentations by civil society representatives;

3.

working groups and students

presentations;

4.

face-to-face simulation.

More information can be found on the

ISSOC website:

http://issocct.wordpress.com/2014/02/

21/issoc/

gh

11

ECPR Standing Group on Organised Crime

May 2014, Volume 11, Issue 2

MISCELLANEOUS

The Standing Group on Organised Crime

presents

UNDERSTANDING AND TACKLING THE ROOTS OF INSECURITY:

TERRORISM, TRANSNATIONAL ORGANISED CRIME

AND CORRUPTION

Following the success of the

Standing Group on Organised Crime

(SGOC)s Section Transnational Organised Crime in a Globalised World

at the 7th ECPR General Conference

in Bordeaux in 2013, SGOC members have reaffirmed their commitment to creating an intellectual

platform for the study of terrorism, organised crime, and corruption by putting

together a section Understanding and

Tackling the Roots of Insecurity: Terrorism, Transnational Organised Crime and

Corruption at the ECPR General Conference taking place at the University of

Glasgow from the 3rd to the 6th of September 2014. The section will be chaired

by Dr. Yuliya Zabyelina (University of

Edinburgh) and co-chaired by Dr. Helena

Carrapico (University of Dundee).

The Section offers to review traditional understandings of security and insecurity and suggests raising questions

about the impact of globalization on these

concepts. It also proposes to examine a

series of phenomena that are currently

understood as transnational security threats, including, but not limited to, terrorism

and terrorism financing, transnational organised crime in its various manifestations, environmental crime, illegal

migration, cyber-crime, and illicit economics of failed states and (post)-conflict

areas. The Section also calls for assessments on the relevance of these problems for the security of the international

and European communities, both states

and individuals.

We have always demonstrated mea-

Glasgow 2014

ECPR General

Conference

3-6 September 2014

ningful presence at ECPR conferences,

but this year we have collected more than

60 abstracts and expect to have a total of

11 panels. Indicative of the high calibre of

SGOCs contribution is the inspiring array

of topics incorporated into the following

panels:

- Contemporary border security challenges

- Global and National Responses to Organised Crime and Terrorism

- Non-State Responses to Insecurity and Corruption

- Non-State Responses to Terrorism and Organised Crime

- Old threats, new challenges:

terrorism and transnational organised

crime

- Making the Elusive Visible

and Tangible: Corruption in Politics

and in the Private Sector

- Political interactions in contexts of presence and influence of criminal organizations

- Understanding and Mitigating Radicalization and Terrorism

- Emerging Trends in Crime:

Crime in the Internet

- The EU Fight against Terrorism, Organized Crime and Corruption

- Italian Organised Crime:

Past, Present and Future

By addressing these key issues,

we expect to engage in a continuing

debate on conventional and alternative theoretical approaches towards

defining, studying and responding to

terrorism, organised crime, and corruption in various parts of the world

and by various actors. Considering

the disciplinary diversity we have demonstrated, this debate could be instrumental

in building bridges across academic and

methodological traditions.

With regards to SGOCs intellectual

input, the meeting at the ECPR General

Conference in Glasgow will not only provide its participants with an opportunity to

exchange ideas and experience but will

also offer an exciting publishing opportunity. A selection of best papers presented

at SGOCs panels in Glasgow will be considered for potential publication in The

European Review of Organised Crime

(EROC), SGOCs own online open-access peer-reviewed journal the group

launched in 2013. Other publications will

also be developed, in particular special issues in peer-reviewed journals. We would

also like to draw your attention timportance of this conference in terms of serving as a platform for developing future

research projects.

Should you be interested in attending

SGOCs panels in Glasgow, join the

SGOC, or receive updates about the

Groups activities, please contact us at

ecpr.sgoc@googlemail.com or visit

SGOCs website

http://www.sgocnet.org/

12

ECPR Standing Group on Organised Crime

May 2014, Volume 11, Issue 2

CONTRIBUTIONS!

For the newsletter we are looking for short

original articles (1000-1500 words) on different

organised crime-related themes. These contributions can stem from yur on- going research

or from summaries of published material, which

you might wish to circulate among the organised crime research community.

You may also contribute to the content of the

newsletter by sending us any announcement of

conferences/ workshops/ literature references

you feel could be of interest to this field.

You are also invited to

propose things that could

improve the quality of the

newsletter.

Please send your suggestions and articles to:

Anna Sergi

asergi@essex.ac.uk

Falko Ernst

faerns@essex.ac.uk

The Next Issue of the ECPR

Standing Group on Organised

Crime Newsletter will be

published

at the end of September 2014.

The deadline for articles and

contributions

is 20th of September 2014.

SUGGESTIONS!

ECPR General Conference

3 - 6 September 2014

University of Glasgow

#ecprconf14

DONOTMISS...all the content from this and previous newesletters, and info on the

authors, will be uploaded on the new website www.sgocnet.org

Visit the SGOC Website at: www.sgocnet.org

And Stay Tuned,

A new website is coming!

Visit the SGOC blog at: http://sgoc.blogspot.co.uk

Join Our Facebook Group Page..our Like us on Facebook!

And we are also on LinkedIn and Twitter @ecpr_sgoc!

Вам также может понравиться

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Call - 2015 CEPOL ANNUAL EUROPEAN POLICE RESEARCH AND SCIENCE CONFERENCEДокумент2 страницыCall - 2015 CEPOL ANNUAL EUROPEAN POLICE RESEARCH AND SCIENCE CONFERENCESGOCnetОценок пока нет

- Standing Group On Organised Crime: Newsletter, January 2014, Volume 11, Issue 1Документ11 страницStanding Group On Organised Crime: Newsletter, January 2014, Volume 11, Issue 1SGOCnetОценок пока нет

- Flyer - 2015 Cepol Annual European Police Research and Science ConferenceДокумент2 страницыFlyer - 2015 Cepol Annual European Police Research and Science ConferenceSGOCnetОценок пока нет

- September in Cambridge and Bordeaux: Editorial NoteДокумент13 страницSeptember in Cambridge and Bordeaux: Editorial NoteSGOCnetОценок пока нет

- ECPR OCSG Newsletter Nov 2010-2Документ19 страницECPR OCSG Newsletter Nov 2010-2SGOCnetОценок пока нет

- Standing Group On Organised Crime: Newsletter, May. 2013, Volume 10, Issue 2Документ14 страницStanding Group On Organised Crime: Newsletter, May. 2013, Volume 10, Issue 2SGOCnetОценок пока нет

- Standing Group On Organised Crime: Newsletter, Dec. 2011, Volume 9, Issue 3Документ14 страницStanding Group On Organised Crime: Newsletter, Dec. 2011, Volume 9, Issue 3SGOCnetОценок пока нет

- ECPR SGOC Call For Papers, 2013 BordeauxДокумент3 страницыECPR SGOC Call For Papers, 2013 BordeauxSGOCnetОценок пока нет

- Standing Group On Organised Crime: Newsletter, Jan. 2013, Volume 10, Issue 1Документ12 страницStanding Group On Organised Crime: Newsletter, Jan. 2013, Volume 10, Issue 1SGOCnetОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Geography Cba PowerpointДокумент10 страницGeography Cba Powerpointapi-489088076Оценок пока нет

- Challenges Students Face in Conducting A Literature ReviewДокумент6 страницChallenges Students Face in Conducting A Literature ReviewafdtunqhoОценок пока нет

- Pepsi IMCДокумент19 страницPepsi IMCMahi Teja0% (2)

- PSI 8.8L ServiceДокумент197 страницPSI 8.8L Serviceedelmolina100% (1)

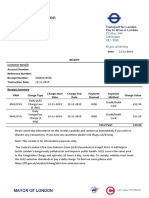

- Transport For London Pay To Drive in London: PO Box 344 Darlington Dl1 9qe TFL - Gov.uk/drivingДокумент1 страницаTransport For London Pay To Drive in London: PO Box 344 Darlington Dl1 9qe TFL - Gov.uk/drivingDanyy MaciucОценок пока нет

- TUV300 T4 Plus Vs TUV300 T6 Plus Vs TUV300 T8 Vs TUV300 T10 - CarWaleДокумент12 страницTUV300 T4 Plus Vs TUV300 T6 Plus Vs TUV300 T8 Vs TUV300 T10 - CarWalernbansalОценок пока нет

- 6.T24 Common Variables-R14Документ29 страниц6.T24 Common Variables-R14Med Mehdi LaazizОценок пока нет

- E2 Lab 2 8 2 InstructorДокумент10 страницE2 Lab 2 8 2 InstructorOkta WijayaОценок пока нет

- LSM - Neutral Axis Depth CalculationДокумент2 страницыLSM - Neutral Axis Depth CalculationHimal KafleОценок пока нет

- Patient Care Malaysia 2014 BrochureДокумент8 страницPatient Care Malaysia 2014 Brochureamilyn307Оценок пока нет

- Direct Marketing CRM and Interactive MarketingДокумент37 страницDirect Marketing CRM and Interactive MarketingSanjana KalanniОценок пока нет

- Fss Operators: Benchmarks & Performance ReviewДокумент7 страницFss Operators: Benchmarks & Performance ReviewhasanmuskaanОценок пока нет

- 2010 LeftySpeed Oms en 0Документ29 страниц2010 LeftySpeed Oms en 0Discord ShadowОценок пока нет

- Pat Lintas Minat Bahasa Inggris Kelas XДокумент16 страницPat Lintas Minat Bahasa Inggris Kelas XEka MurniatiОценок пока нет

- Market Research and AnalysisДокумент5 страницMarket Research and AnalysisAbdul KarimОценок пока нет

- HP Mini 210-2120br PC Broadcom Wireless LAN Driver v.5.60.350.23 Pour Windows 7 Download GrátisДокумент5 страницHP Mini 210-2120br PC Broadcom Wireless LAN Driver v.5.60.350.23 Pour Windows 7 Download GrátisFernandoDiasОценок пока нет

- New Holland TM165 Shuttle Command (Mechanical Transmission) PDFДокумент44 страницыNew Holland TM165 Shuttle Command (Mechanical Transmission) PDFElena DОценок пока нет

- Catalogo AMF Herramientas para AtornillarДокумент76 страницCatalogo AMF Herramientas para Atornillarabelmonte_geotecniaОценок пока нет

- Azar Mukhtiar Abbasi: Arkad Engineering & ConstructionДокумент4 страницыAzar Mukhtiar Abbasi: Arkad Engineering & ConstructionAnonymous T4xDd4Оценок пока нет

- Self-Study Guidance - Basic Accounting. 15 Problems With Detailed Solutions.Документ176 страницSelf-Study Guidance - Basic Accounting. 15 Problems With Detailed Solutions.Martin Teguh WibowoОценок пока нет

- FairyДокумент1 страницаFairyprojekti.jasminОценок пока нет

- PPR 8001Документ1 страницаPPR 8001quangga10091986Оценок пока нет

- Arslan 20 Bba 11Документ11 страницArslan 20 Bba 11Arslan Ahmed SoomroОценок пока нет

- Implementation of BS 8500 2006 Concrete Minimum Cover PDFДокумент13 страницImplementation of BS 8500 2006 Concrete Minimum Cover PDFJimmy Lopez100% (1)

- Important Dates (PG Students View) Semester 1, 2022-2023 - All Campus (As of 2 October 2022)Документ4 страницыImportant Dates (PG Students View) Semester 1, 2022-2023 - All Campus (As of 2 October 2022)AFHAM JAUHARI BIN ALDI (MITI)Оценок пока нет

- Businesses ProposalДокумент2 страницыBusinesses ProposalSophia Marielle MacarineОценок пока нет

- Radioss For Linear Dynamics 10.0Документ79 страницRadioss For Linear Dynamics 10.0Venkat AnumulaОценок пока нет

- Exercise 3 - Binary Coded DecimalДокумент3 страницыExercise 3 - Binary Coded DecimalNaiomi RaquinioОценок пока нет

- Magnetic Properties of MaterialsДокумент10 страницMagnetic Properties of MaterialsNoviОценок пока нет

- MOFPED STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 - 2021 PrintedДокумент102 страницыMOFPED STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 - 2021 PrintedRujumba DukeОценок пока нет