Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

205 Full

Загружено:

lynayanisИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

205 Full

Загружено:

lynayanisАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

http://foa.sagepub.

com/

Developmental Disabilities

Focus on Autism and Other

http://foa.sagepub.com/content/19/4/205

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/10883576040190040201

2004 19: 205 Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl

Kyoung Gun Han and Janis G. Chadsey

ToWard Peers With Severe Disabilities

The Influence of Gender Patterns and Grade Level on Friendship Expectations of Middle School Students

Published by:

Hammill Institute on Disabilities

and

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at: Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities Additional services and information for

http://foa.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://foa.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

What is This?

- Jan 1, 2004 Version of Record >>

at UNIV CALGARY LIBRARY on March 25, 2014 foa.sagepub.com Downloaded from at UNIV CALGARY LIBRARY on March 25, 2014 foa.sagepub.com Downloaded from

A

s students with disabilities are

educated in general education set-

tings, friendships between stu-

dents with and without disabilities have

been considered an important educa-

tional outcome (e.g., Hamre-Nietupski,

1993; Hendrickson, Shokoohi-Yekta,

Hamre-Nietupski, & Gable, 1996; Ken-

nedy & Fisher, 2001; Meyer, Park,

Grenot-Scheyer, Schwartz, & Harry,

1998). Friendships play a critical role

in students social development; they

expose students to important interper-

sonal skills, such as cooperation, sharing,

self-disclosure, and conflict resolution

(Hartup, 1992). In addition, friendships

make a contribution to ones self-esteem

and emotional well-being (Buhrmester,

1990). Further, through close friend-

ships, students receive numerous bene-

fits, such as affection, intimacy, valida-

tion, and the security of a trusted peer

(Buhrmester & Furman, 1986).

For students with disabilities, it is now

widely affirmed that friendships are con-

sidered important for a high quality of

life (e.g., Meyer et al., 1998). Parents

with children who have moderate or se-

vere disabilities consider friendships and

social relationships as critical outcomes

that should be emphasized in school ac-

tivities (Hamre-Nietupski, 1993). Friend-

ships with peers without disabilities can

also serve as the basis for some of the so-

cial, emotional, and practical support stu-

dents with disabilities need to become

FOCUS ON AUTISM AND OTHER DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

VOLUME 19, NUMBER 4, WINTER 2004

PAGES 205214

The Influence of Gender Patterns

and Grade Level on Friendship

Expectations of Middle School

Students Toward Peers with

Severe Disabilities

Kyoung Gun Han and Janis G. Chadsey

This exploratory study investigated gender and grade level factors in friendship expec-

tations of middle school students toward their peers with severe disabilities. A total of

65 students from two middle schools were surveyed using a specifically designed in-

strument called the Middle School Friendship Survey. Results indicated that typical

middle school students had relatively low friendship expectations for their peers with

severe disabilities. Although there were no significant differences in friendship expecta-

tions by gender, there were differences across grade levels. Students in Grade 6 had

lower expectations for friendships than students in Grades 7 and 8. Unlike prior studies

reported in the literature regarding friendship expectations toward peers without dis-

abilities, the current study found that friendship expectations toward peers with severe

disabilities were not influenced by gender, but by grade level. Implications and recom-

mendations for practice are discussed.

truly integrated into everyday commu-

nity life (Traustadottir, 1993).

Some students with severe disabilities

may have limited social skills that create

difficulties for establishing friendships with

peers without disabilities, particularly in

displaying reciprocal interchanges and sus-

tained interactions (Guralnick & Groom,

1988). However, several studies have

shown that peers without disabilities are

willing to be friends with their classmates

who have severe disabilities (e.g., Hen-

drickson et al., 1996; Peck, Donaldson,

& Pezzoli, 1990), and friendships be-

tween students with severe disabilities

and their peers exist (e.g., Evans, Salis-

bury, Palombaro, Berryman, & Hollo-

wood, 1992; Grenot-Scheyer, 1994;

Schnorr, 1997).

As children become young adoles-

cents, friendships with peers become in-

creasingly important because peers offer

necessary models and back-up supports

formerly provided by family members

(Zetlin & Murtaugh, 1988). According

to Raffaelli and Duckett (1989), adoles-

cence is a time of emotional reorientation

to the peer group and increasing detach-

ment from the family. Therefore, appro-

priate and active peer relationships, such

as friendships, are extremely important

for young adolescents to become socially

at UNIV CALGARY LIBRARY on March 25, 2014 foa.sagepub.com Downloaded from

FOCUS ON AUTISM AND OTHER DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

206

competent individuals. It is also believed

that students who are in late childhood

and early adolescence begin to develop

expectations for their friendships (Bige-

low & La Gaipa, 1980). Bigelow and La

Gaipa maintained that young adolescents

begin to develop expectations about the

qualities that friends should possess, and

are attracted to and befriend those who

meet the expectations. Young adoles-

cents have their own expectations regard-

ing desirable characteristics in a friend,

and those expectations may guide the

friendship selection process and the eval-

uation of their friends (Clark & Ayers,

1993).

Friendship expectations may differ by

gender. During adolescence, it is gener-

ally believed that girls develop more inti-

mate friendships than boys. Clark and

Ayers (1993) reported that female junior

high school students had more expecta-

tions regarding characteristics (e.g., mor-

ality, loyalty, commitment, empathic un-

derstanding) of close friendships than

male students. Friendship expectations

may also vary by age or grade level.

Friendships in childhood are character-

ized by mutual trust and assistance, but

during early adolescence, friendships are

centered on characteristics of intimacy

and loyalty (Berndt, 1986; Furman &

Buhrmester, 1985).

Though only a few attempts have been

made to look at gender issues and friend-

ships in the field of special education,

studies have reported that gender differ-

ences often occur in social relationships

and friendships between students with

and without disabilities. Literature sug-

gests that from childhood on, females

have more positive attitudes toward indi-

viduals with disabilities, are more willing

to make social contact with them, and are

more likely than males to become friends

of students with disabilities (e.g., Kishi &

Meyer, 1994; Krajewski & Flaherty,

2000). Consequently, for people with dis-

abilities who have friends, women with-

out disabilities are overrepresented in

friendships (Traustadottir, 1993). There-

fore, it is quite probable that there may

be differences in friendship expectations

between female and male students with-

out disabilities toward their friendships

with peers with disabilities. Also, if the

characteristics of friendships change as

students get older, then one might hy-

pothesize that friendship expectations of

students without disabilities toward their

peers with disabilities will vary by age or

grade level. Moreover, given that stu-

dents in middle school settings are tran-

sitioning from childhood to early adoles-

cence, they may experience rapid changes

in expectations about having friends and

being friends to others. Unfortunately,

direct investigations on the influence of

gender patterns and age on friendship ex-

pectations of middle school students to-

ward their peers with severe disabilities

are sparse.

The purpose of this study was to ex-

plore the influence of gender and grade

level on friendship expectations of typical

middle school students toward their peers

with severe disabilities. Rather than com-

paring the friendship expectations to-

ward peers with and without severe

disabilities, we sought only to explore

friendship expectations toward peers with

severe disabilities to make possible rec-

ommendations for practice. The knowl-

edge of friendship expectations that typ-

ical young adolescents have toward peers

with disabilities would allow us to iden-

tify the determinants of friendship se-

lection and the characteristics needed for

the maintenance of relationships. It would

also help us understand how typical mid-

dle school students gender and grade

level impact their friendship expectations

toward peers with severe disabilities. Con-

sequently, this knowledge would provide

educators and researchers with a vehicle

to create intervention approaches, espe-

cially for intrinsic strategies, that are spe-

cifically designed to meet grade level and

gender factors in fostering social relation-

ships between students with and without

severe disabilities in middle school set-

tings.

Method

To explore the factors of gender and

grade level differences in friendship ex-

pectations, the Middle School Friendship

Survey (MSF; see Note) was developed

and administered to students who were

enrolled in middle schools that included

students with severe disabilities.

Participants

The MSF was administered to students

from sixth, seventh, and eighth grades in

one middle and one junior high school in

two small Midwestern communities. The

schools were selected because they were

midsize, had similar percentages of stu-

dents with severe disabilities, and re-

ported the use of some inclusion prac-

tices. Junior High School A had 680

enrolled students and was located in a

middle-class urban area. According to

the building principal, about 9% of stu-

dents (n = 62) had been identified as hav-

ing disabilities and about 10% (n = 6) of

them had moderate or severe disabilities.

The students with severe disabilities were

placed mainly in a self-contained class-

room for academic classes during the

school day, and participated in general

education classes, such as P.E., art, music,

and lunch. This school had no special

program to promote social interactions

between students with and without se-

vere disabilities.

Middle School B was located in a

middle- to upper-middle-class suburban

area and had a student population of 682.

The building principal reported that

about 18% of the students (n = 122) had

been identified as having disabilities, and

7% (n = 8) were labeled as having mod-

erate and severe disabilities. The students

with severe disabilities were partially in-

cluded in general education settings, de-

pending on their IEPs. Typically these

students were included in art, music, in-

dustrial technology, life skills, lunch, and

P.E. The building principal indicated that

the school had a dance party program

that encouraged students with severe dis-

abilities to participate with their peers.

The building principals of the two

schools asked classroom teachers for vol-

untary participation, and one class from

each grade was randomly selected. The

teachers were asked only if they taught

classes common to all students, such as

math, social science, social studies, and

language arts. A total of 137 students

from six classes (i.e., one class from each

grade and three classes from each school)

were asked to fill out the MSF, and 65

students did so, yielding a 47% response

rate. In Junior High School A, 53 of the

at UNIV CALGARY LIBRARY on March 25, 2014 foa.sagepub.com Downloaded from

VOLUME 19, NUMBER 4, WINTER 2004

207

68 possible students completed the MSF;

one of the questionnaires was excluded

for data analysis because it contained

missing items. The participating classes

were social studies (Grade 6) and lan-

guage arts (Grades 7 and 8). In Middle

School B, 15 of the 69 possible students

filled out the MSF; two questionnaires

were excluded because of missing items.

The participating classes were science

(Grade 6), language arts (Grade 7), and

reading (Grade 8).

To determine the validity of combin-

ing the data obtained from the two

schools whose response rates were not

equal (i.e., 78% in School A and 22% in

School B), a chi-square test for categori-

cal variables (gender and grade levels)

was conducted. This analysis revealed

that the two variables were not statisti-

cally significant from each other: gender,

2

(1, N = 65) = 1.004, p > .05; grade,

2

(2, N = 65) = .771, p > .05, meaning

that the data from the two schools could

be assumed to be drawn from the same

population on these two variables.

Therefore, the data from the two samples

were combined for further analyses.

Out of the total of 65 respondents, 28

(43%) students were boys and 37 (57%)

were girls. The respondents matched the

ethnic makeup of both schools. Among

them, almost 90% were European Amer-

ican, 4.5% were African American, and

3% were Hispanic. About 66% (n = 43)

of the respondents indicated there was at

least one student with severe disabilities

in one or more of their class periods, 17%

(n = 11) had more than two class periods

with peers with severe disabilities, and

27% (n = 18) replied that they did not

have any classes with students with severe

disabilities. Of the respondents, 26% (n =

17) had a family member with disabili-

ties, and 14% (n = 9) reported that they

had friends with severe disabilities.

Survey Instrument

The MSF consisted of six pages of ques-

tions in five sections: Part I asked for de-

mographic information, Part II probed

friendship activities with friends who did

not have disabilities, Part III asked about

friendship activities with friends who had

severe disabilities, Part IV looked at per-

ceptions about friendships with students

who have severe disabilities, and Part V

asked about friendship expectations for

students with severe disabilities. In all of

these sections, participants were asked

forced-choice questions or were asked

to provide short answers to open-ended

questions.

The items included in the MSF were

generated by a review of published re-

search on friendships in children and

young adolescents (e.g., Clark & Ayers,

1993; Clark & Bittle, 1992; DuBois &

Hirsch, 1993) and the perceptions and

attitudes of students without disabilities

about their peers with severe disabilities

(e.g., Hendrickson et al., 1996; Krajew-

ski & Flaherty, 2000). With the informa-

tion from these two literature bases, the

MSF reflected general friendship charac-

teristics of young adolescents and stu-

dents with disabilities. Once the ques-

tions were developed, four experts who

conduct research in the area of social re-

lationships and friendships of students

with disabilities were asked to examine

the items of the MSF and determine their

content validity. The experts primarily

suggested that some of the wording for

middle school students be clarified.

In addition to the content validation

procedure, a pilot test was conducted

with a fifth-grade student to see if the

MSFs wording, layout, and procedures

were easy for younger students to under-

stand. A second pilot test was conducted

with four eighth-grade students. The stu-

dents were asked to give feedback about

the clarity of the survey directions and

questions. The participants of the pilot

tests indicated that they could under-

stand the words and questions, but some

directions were slightly confusing. Based

on this feedback, directions were revised.

Part V of the MSF, which asked stu-

dents about their expectations for friend-

ships involving students with severe dis-

abilities, served as the primary dependent

variable for the study. Questions in Part

V included 32 items describing possible

activities and characteristics that partici-

pants would want in their friends with

severe disabilities. The 32 items were

categorized into three groups (i.e., Indi-

vidual Characteristics, Shared Activities,

and Relationship Characteristics) that

were considered common components

of friendships. The Individual Character-

istics category included three subcatego-

ries: Similarities, Function/Capability, and

Appearance/Characteristics. The Shared

Activities category had two subcate-

gories: In-School Activities and After-

School Activities. The Relationship

Characteristics category included four

subcategories: Intimacy, Support, Loy-

alty, and Peer Pressure. Items from the

categories were randomly interspersed to

prevent them from being arranged in a

particular pattern. The participants were

asked to rate the importance of each item

using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = not im-

portant at all, 6 = extremely important).

Table 1 shows some sample items from

Part V.

Procedures

The first author contacted the principals

from each participating school and de-

scribed the purpose of the study. Both

principals were asked to identify one class

and teacher from the sixth, seventh, and

eighth grades who might be willing to

participate in the study. Each principal

described the study to three teachers who

volunteered to participate in administer-

ing the MSF. The teachers distributed

parental and student consent letters. Stu-

dents who agreed to participate in the

study were asked to fill out the MSF in

their classes; the survey took approxi-

mately 20 minutes to complete and the

teachers collected the completed surveys.

The teachers and the responding stu-

dents were given a small gift (e.g., gift

certificates for a local bookstore, ball-

point pens) for their time.

Data Analysis

When the data obtained from the surveys

was entered into SPSS 10.0 for Win-

dows, a doctoral student in special edu-

cation read the data to the first author

and checked the first authors entries as

they were put into the computer. De-

scriptive statistics were used to analyze

the information gathered from Part I to

Part IV. Responses to each question were

tallied and frequencies and percentages

were calculated to determine the kinds of

at UNIV CALGARY LIBRARY on March 25, 2014 foa.sagepub.com Downloaded from

FOCUS ON AUTISM AND OTHER DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

208

friendship activities identified (Part II

and III) and different perceptions re-

ported (Part IV). These data were ana-

lyzed only descriptively according to

gender patterns and grade level because

the questions were open-ended and the

main dependent variable was Part V.

A Cronbachs coefficient alpha was

computed to check the internal consis-

tency of the items in Part V for each of

the three main categories and their sub-

categories. The means and standard de-

viations for the 32 items were calculated.

In addition, a 3 2 two-factor ANOVA

design, in which one factor had two lev-

els (i.e., male and female) and the other

factor had three levels (i.e., Grades 6, 7,

and 8), was used to test the significance

and interaction effects for each main cat-

egory and the subcategories.

Results

Internal Consistency

To check the internal consistency (i.e.,

internal reliability) of Part V of the MSF,

Cronbachs coefficient alphas were cal-

culated across all categories. The overall

reliability coefficient for all 32 questions

was .8870. Of the three major categories,

the Shared Activities category had the

largest internal consistency coefficient

(i.e., .8541), followed by the Individual

Characteristics category (i.e., .8148), and

the Relationship Characteristics category

(i.e., .6938). Because all categories were

larger than the desired level of reliability

coefficient of .60 (Heppner, Kivlighan,

& Wampold, 1992), no single question-

naire item was excluded from further

data analysis procedures.

To see if the results of Part V from the

two participating schools could be com-

bined, a Levenes test for equality of vari-

ance was conducted. The result showed

that the test assumed equal variances and

the differences of the variances of two

schools were not statistically significant,

t(63) = .365, p > .50. Based on the re-

sult of the test, the data obtained from

the schools were combined for further

analysis.

Activities With Friends

Without Disabilities

Tables 2 and 3 illustrate the activities in

which the respondents reported partici-

pating with their friends without disabil-

ities both at school and after school

(Parts II and III). More than 70% of the

boys across all grade levels indicated that

they participated in sports at school,

mainly basketball and football. Girls also

mentioned sports as their number-one

in-school activity, participating mainly in

basketball and volleyball. Talking with

others at school and playing games were

also mentioned as frequently occurring

activities by boys and girls.

For after-school activities, playing sports

was again the most frequently identified

activity by boys and girls. Girls also talked

on the phone, shopped, visited with

friends, and were involved in clubs; boys

reported they played with video games

and computers.

Activities with Friends with

Severe Disabilities

Nine students (14%) reported that they

had friends with severe disabilities (i.e.,

five students at Junior High School A

and four students at Middle School B).

Of these nine students, six were girls.

Four of the students were in Grade 6,

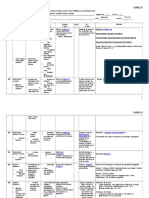

TABLE 1

Sample Questions From Part V

Main category Subcategory Sample questions

Individual characteristics Similarities It is important that my friends with severe disabilities be the same

gender as I am.

Function/capability It is important that my friends with severe disabilities be

athletic.

Appearance/characteristics It is important that my friends with severe disabilities be

attractive.

Shared activities In-school activities It is important that my friends with severe disabilities play sports

or games with me at school.

After-school activities It is important that my friends with severe disabilities go to movies

with me.

Relationship characteristics Intimacy It is important that my friends with severe disabilities tell me their

secrets.

Support It is important that my friends with severe disabilities help me with

school work at school.

Loyalty It is important that my friends with severe disabilities be loyal

to me.

Peer pressure My friends without disabilities should like him or her, too.

at UNIV CALGARY LIBRARY on March 25, 2014 foa.sagepub.com Downloaded from

VOLUME 19, NUMBER 4, WINTER 2004

209

and five were in Grade 8. No students in

Grade 7 reported having friends with se-

vere disabilities. The students met their

friends with severe disabilities mainly in

their classes (n = 4) and at church (n =

4). Two girls indicated that they met

their friends with severe disabilities

through other friends without disabili-

ties. Talking was identified as the most

frequent activity for both boys (n = 2,

both at school and after school) and girls

(n = 5 at school, and n = 4 after school).

Reasons for Not Having a

Friend with Severe Disabilities

Respondents were asked why they did

not have a friend with severe disabilities

and if they were willing to make friends

with students with severe disabilities (see

Table 4). The most frequently cited rea-

son that students did not have friends

with severe disabilities was related to

their limited opportunity to interact with

peers with severe disabilities. About

51.7% of the respondents indicated that

peers with severe disabilities were not in

their classes. The other three most com-

mon reasons included, I do not have

many opportunities to see them at

school (i.e., 40% for boys and 32% for

girls), They are always with teaching as-

sistants (i.e., 20% for boys and 42% for

girls), and I do not know any (16% for

boys and 22.5% for girls). In addition to

citing the limited opportunities for inter-

actions, respondents also identified peer

pressure as a reason. Approximately 14%

of the respondents stated that their other

friends might tease them if they made

friends with peers with severe disabilities;

boys (20%) indicated this reason more

often than girls (9.7%).

When respondents were asked if they

would be willing to make friends with

students with severe disabilities, 89.3% of

the students (i.e., 84% for boys and

93.6% for girls) replied that they were

willing to make friends with students

with severe disabilities, regardless of

gender. Three boys answered that they

would prefer male friends with severe dis-

abilities, and one girl stated that she

would prefer a female friend. Two stu-

dents replied that they did not want to

make friends with students who have se-

vere disabilities.

Friendship Expectations

Toward Peers with

Severe Disabilities

Means Scores. Tables 5 and 6 show

the mean scores for importance ratings of

friendship expectations across all subcat-

egories by gender and grade. The results

in Table 5 indicate that girls and boys had

similar expectations toward peers with

severe disabilities for friendship forma-

TABLE 2

The Most Frequently Occurring In-School Activities Reported With

Friends Without Disabilities

Boys

a

Girls

b

Total

Grade level Activity f % f % f %

6 Sports 15 75.0 8 38.1 23 56.1

Talking 1 5.0 5 23.8 6 14.6

Playing games 2 10.0 8 38.1 10 24.4

Club activities 2 10.0 2 4.9

7 Sports 13 72.3 8 40.0 21 55.3

Talking 3 16.7 7 35.0 10 26.3

Playing games 1 5.5 3 15.0 4 10.5

Club activities 1 5.5 2 10.0 3 7.9

8 Sports 11 78.6 12 52.3 23 62.0

Talking 1 7.1 5 21.7 6 16.2

Hanging around 2 14.3 1 4.3 3 8.2

Club activities 3 13.0 3 8.2

Playing games 2 8.7 2 5.4

Note. The respondents were allowed to mark multiple answers.

a

n = 28.

b

n = 37.

TABLE 3

The Most Frequently Occurring After-School Activities Reported With Friends

Without Disabilities

Boys

a

Girls

b

Total

Grade level Activity f % f % f %

6 Sports 11 68.7 7 36.8 18 51.4

Video games 3 18.8 1 5.3 4 11.4

Visiting/inviting friends 2 12.5 1 5.3 3 8.6

Talking on the phone 5 26.3 5 14.3

Shopping 2 10.5 2 5.7

Playing games 3 15.8 3 8.6

7 Sports 10 76.9 7 46.7 17 60.7

Shopping 5 33.3 5 17.9

Computer activity 3 23.1 3 10.7

Movies 3 20.0 3 10.7

8 Sports 5 50.0 8 38.1 13 41.9

Video games 2 20.0 2 6.5

Hanging out 2 20.0 2 9.5 4 12.9

Visiting/inviting friends 1 10.0 3 14.3 4 12.9

Club activities 6 28.6 6 19.3

On-line chatting 2 9.5 2 6.5

Note. The respondents were allowed to mark multiple answers.

a

n = 28.

b

n = 37.

at UNIV CALGARY LIBRARY on March 25, 2014 foa.sagepub.com Downloaded from

FOCUS ON AUTISM AND OTHER DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

210

tion. The overall mean score of the 32

questions was 2.50 (SD = .57), meaning

that most items were rated as being be-

tween not very important and some-

what important; the mean for girls

(M = 2.52, SD = .56) was slightly higher

than that for boys (M = 2.46, SD = .60).

A comparison of the mean ratings across

all of the subcategories of friendship ex-

pectations indicated that the category of

Relationship Characteristics was the only

one with its mean score over three (for

girls, M = 3.56, SD = .73; for boys, M =

3.27, SD = .85), meaning that both girls

and boys regarded this category as some-

what important or important to mak-

ing friends with peers with severe dis-

abilities.

Differences Among Means by Gen-

der and Grade Levels. Though the to-

tal mean scores of girls were higher than

those of boys, there was no significant

difference between the two mean scores.

In addition, there were no significant dif-

ferences between the two mean scores of

boys and girls across two major cate-

gories (i.e., Individual Characteristics and

Shared Activities) and across all nine

subcategories. Only in the Relationship

Characteristics category was there a sig-

nificant difference between gender, F(1,

59) = 4.06, p < .05, with the mean score

of girls (M= 3.56, SD = .73) higher than

that of boys (M = 3.27, SD = .85).

The results showed that overall there

were statistical differences among grades,

F(2, 59) = 3.436, p < .05. Tukeys test

showed that there was a significant dif-

ference between the students in Grade 6

and Grade 7 (Grade 6, M = 2.27;

Grade 7, M = 2.7; p < .05), but not be-

tween Grades 6 and 8 or Grades 7 and 8.

All three major categories were found to

be significantly different across grades,

but primarily Grade 6 was different from

Grades 7 and 8. In the Individual Char-

acteristics category, F(2, 59) = 4.704,

p < .05, the mean score of Grade 6 (M =

1.68, SD = .53) was statistically different

from that of Grade 8 (M = 2.2, SD =

.59). In the Shared Activities category,

F(2, 59) = 4.200, p < 05, the mean score

of Grade 6 (M= 2.13, SD = .64) was sta-

tistically different from that of Grade 7

(M = 2.7, SD = .78). In the Relation-

ship Characteristics category, F(2, 59) =

4.804, p < .05, the mean score of

Grade 7 (M= 3.71, SD = .69) was statis-

tically different from that of Grade 8

(M = 3.13, SD = .74).

Two subcategories were significantly

different across grades with Grade 6

being different from Grades 7 and 8. In

the Similarities within the Individual Char-

acteristics category, F(2, 59) = 8.893,

p < .0001, the mean score of Grade 6

(M= 1.53, SD = .51) was statistically dif-

ferent from that of Grades 7 (M = 2.27,

SD = .77) and 8 (M = 2.20, SD = .60).

In addition, in the After-School Activities

within the Shared Activities category,

TABLE 4

Frequency of Reasons for Not Having a Friend with Severe Disabilities

Boys

a

Girls

b

Total

Reason f % f % f %

I would not know what to say. 2 8.0 3 9.7 5 9.0

They are not in my classes. 13 52.0 16 51.6 29 51.7

They could not do things I like to do. 4 16.0 2 6.5 6 10.7

They are always with teaching assistants. 6 20.0 13 42.0 19 34.0

I do not have many opportunities to 10 40.0 10 32.0 20 35.7

see them at school.

I am a little afraid of them. 2 8.0 1 3.2 3 5.4

My friends might tease me. 5 20.0 3 9.7 8 14.3

I feel uncomfortable around them. 3 12.0 4 13.0 7 12.5

I dont know any. 4 16.0 7 22.5 11 19.6

They play with others with disabilities. 1 4.0 1 1.8

They dont talk to me. 2 6.5 2 3.6

Note. The respondents were allowed to mark multiple answers. Percentages = number of answers / total

number of responses.

a

n = 25.

b

n = 31.

TABLE 5

Mean Scores and Standard Deviations Across Friendship Expectation

Categories by Gender

Boys

a

Girls

b

Category M SD M SD

Individual characteristics 2.03 .67 1.94 .60

ICSIM 2.10 .73 1.96 .70

ICFC 2.19 .76 2.00 .70

ICAC 1.85 .87 1.80 .78

Shared activities 2.32 .79 2.45 .71

SASC 2.33 .88 2.52 .81

SAFSC 2.32 .85 2.41 .74

Relationship characteristics 3.27* .85 3.56* .73

IT 2.63 1.14 2.91 1.14

SP 3.47 1.06 3.64 .89

LY 3.68 1.54 4.29 1.56

PP 3.32 1.28 3.81 1.56

Total 2.46 .60 2.52 .56

Note. ICSIM = similarities; ICFC = function/capability; ICAC = appearance/characteristics; SASC =

in-school activities; SAFSC = after-school activities; IT = intimacy; SP = support; LY = loyalty; PP = peer

pressure.

a

n = 28.

b

n = 37.

*p < .05.

at UNIV CALGARY LIBRARY on March 25, 2014 foa.sagepub.com Downloaded from

VOLUME 19, NUMBER 4, WINTER 2004

211

F(2, 59) = 5.996, p < .01, the mean score

of Grade 6 (M= 2.05, SD = .60) was sig-

nificantly different from that of Grade 7

(M = 2.76, SD = .81).

In the Appearance/Characteristics

within the Individual Characteristics, F(2,

59) = 3.800, p < .05, the mean score of

Grade 6 (M = 1.45, SD = .66) was sig-

nificantly different from that of Grade 8

(M= 2.08, SD= .82). Two subcategories

within the Relationship Characteristics

category were found to be significantly

different across grades. In Intimacy, F(2,

59) = 4.633, p < .05, the mean score of

Grade 7 (M = 3.19, SD = 1.10) was sig-

nificantly different from that of Grade 8

(M = 2.33, SD = .90). Additionally, in

Support, F(2, 59) = 4.025, p < .05, the

mean score of Grade 7 (M = 3.89, SD =

.84) was significantly higher than that of

Grade 8 (M = 3.13, SD = .82).

Friendships With and Without Peers

with Severe Disabilities. Due to the

small sample size of the students who had

friends with severe disabilities (n = 9),

their scores were compared descriptively

to the students who did not have friends

with severe disabilities. Although the mean

scores of the students who had friends

with severe disabilities were not very dif-

ferent across the nine subcategories, they

were consistently lower than those of the

students who did not have friends with

severe disabilities except for the Loyalty

subcategory within the Relationship Char-

acteristics category.

Discussion

The purpose of this exploratory study

was to investigate gender and age factors

in friendship expectations of typical mid-

dle school students toward their peers

with severe disabilities. The results from

this study indicated that middle school

students had somewhat low friendship

expectations toward their peers with

severe disabilities, and there were few

significant differences in friendship ex-

pectations by gender. The friendship ex-

pectations that middle school students

had toward their peers with severe dis-

abilities, however, did differ across grade

level, with students in Grade 6 having

lower expectations than those in Grades

7 and 8. Descriptive data indicate that

there were some gender differences in ac-

tivities done with friends without disabil-

ities both at school and after school, and

activities done with friends with severe

disabilities were different from those

done with friends without disabilities. Ad-

ditionally, results indicate that although

typical middle school students were will-

ing to make friends with peers with se-

vere disabilities, the lack of opportunity

to interact with them, the presence of

paraprofessionals, and peer pressure were

given as reasons for few friendships.

Though the respondents in this study

may have had low expectations for

friendships with peers with severe dis-

abilities, it was interesting that they rated

the category of Relationship Characteris-

tics as being more important than the

other categories. Findings from previous

studies of typical adolescents showed that

intimacy, support, and loyalty were the

most important characteristics for their

friendships (e.g., Bigelow & La Gaipa,

1980). Thus, it appears that middle school

students also regard intimacy, support,

and loyalty as important considerations

for making friends with peers with severe

disabilities.

Most of the research on the friendship

expectations of typical adolescents has

found that girls and boys have somewhat

different expectations for friendships.

Research suggests that girls have higher

expectations for friends, and expect more

empathetic understanding and a higher

level of intimacy as compared to boys

(e.g., Clark & Bittle, 1992). In the pres-

ent study, there were few differences by

gender; however, girls did have higher

expectations for the category of Rela-

tionship Characteristics.

The most significant finding from this

study was that friendship expectations

toward peers with severe disabilities dif-

fered by grade level. Friendship expecta-

tions of students in Grade 6 were lower

than those for students in Grades 7 and

8, and students in Grade 7 seemed to

have the highest friendship expectations

among students in the three grades.

While age has been a factor in friendships

among typical elementary (Buhrmester

& Furman, 1986) and secondary stu-

dents (McNelles & Connolly, 1999), few

studies have looked at this factor with re-

spect to its impact on students with dis-

abilities. However, Hall and McGregor

TABLE 6

Mean Scores and Standard Deviations Across Friendship Expectation

Categories by Grade

Grade 6

a

Grade 7

b

Grade 8

c

Category M SD M SD M SD

Individual characteristics 1.68* .53 2.08 .66 2.22* .59

ICSIM 1.53** .51 2.27** .77 2.20** .60

ICFC 1.91 .77 2.04 .73 2.29 .66

ICAC 1.45* .66 1.90 .87 2.08* .82

Shared activities 2.13* .64 2.71* .78 2.29 .70

SASC 2.26 .88 2.63 .89 2.39 .72

SAFSC 2.05* .60 2.76* .81 2.22 .73

Relationship characteristics 3.42 .87 3.71* .69 3.13* .74

IT 2.78 1.27 3.19* 1.10 2.33* .90

SP 3.65 1.12 3.89* .84 3.13* .82

LY 3.70 2.03 4.21 1.35 4.14 1.31

PP 3.50 1.79 3.58 1.38 3.71 1.23

Total 2.27* .54 2.71* .56 2.47* .55

Note. ICSIM = similarities; ICFC = function/capability; ICAC = appearance/characteristics; SASC =

in-school activities; SAFSC = after-school activities; IT = intimacy; SP = support; LY = loyalty; PP = peer

pressure.

a

n = 20.

b

n = 24.

c

n = 21.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

at UNIV CALGARY LIBRARY on March 25, 2014 foa.sagepub.com Downloaded from

FOCUS ON AUTISM AND OTHER DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

212

(2000) reported that age was a factor in

peer relationships among students with

and without disabilities as they moved

from kindergarten to elementary school.

In their follow-up study, Hall and Mc-

Gregor found that relationships estab-

lished in kindergarten changed and be-

came less typical and more difficult for

students with disabilities when they

reached the upper elementary grades.

Even though sixth graders in the present

study had lower expectations for friend-

ships as compared to seventh and eighth

graders, it may be that their expectations

are higher than those of kindergarten

children. More research is needed that

investigates age-related factors in expec-

tations for friendships.

The finding of higher expectations for

students in Grade 7 may be due to the

onset of puberty; this period of time

has been described as one of increased

friendship fluctuation (Rice, 1987). It

may be that a transition in social growth

occurs at Grade 7; students in this grade

may develop a different set of percep-

tions on being friends with peers with

severe disabilities, particularly because

friendships in early adolescence take on

greater depth and there is a need for

more intimacy and loyalty (Furman &

Buhrmester, 1985). Or, this difference

could have been due to the particular

sample of seventh graders in this study

because none of them had friends with

severe disabilitiesonly sixth and eighth

graders did. Regardless, when we con-

sider future research directions and the

design of intervention strategies to pro-

mote social relationships between stu-

dents with and without disabilities, grade

level in middle school should be consid-

ered.

The descriptive data from the study

also may have implications for future in-

tervention strategies. Because both girls

and boys identified sports activities as the

most frequent activities done with their

peers without disabilities, students with

severe disabilities should be provided with

opportunities to participate in sports.

Educators may want to develop adapted

sports activities in which both students

with and without disabilities participate

(e.g., Block & Malloy, 1998). After-

school activities, in particular, are impor-

tant because friends who spend more

time together outside school often form

close relationships with each other (Hirsch

& DuBois, 1989) and interactions with

friends outside of school settings are typ-

ical among young adolescents (Blyth,

Hill, & Thiel, 1982). Additionally, after-

school activities are voluntary and may be

more closely aligned to student interests

than in-school activities (Karweit, 1983).

The results from this study also showed

that the activities that typical students en-

gaged in with their friends with disabili-

ties were limited in contrast to those

done with their friends without disabili-

ties; both girls and boys named talking as

the major activity done with their friends

with severe disabilities. Because many

students with severe disabilities have dif-

ficulties communicating with others (Kai-

ser, 2000), it is difficult to know the char-

acteristics and depth of the conversations

between these students. However, com-

munication is a basic element for form-

ing relationships with others, so it is

essential that students with severe dis-

abilities be taught to communicate in in-

timate ways. Typical students may also

need to be taught how to communicate

with peers with severe disabilities.

We also need to pay attention to the

settings where typical students meet their

friends with severe disabilities. For exam-

ple, local churches were reported as a

place to meet friends with severe disabil-

ities. Because almost half of Americans

attend church (Bezilla, 1993), and more

than 60% of parents of individuals with

disabilities consider themselves regular

church attenders (McNair & Rusch,

1991), local churches may be a good

place to meet the social needs of individ-

uals with disabilities by providing them

with many natural opportunities to in-

teract with individuals without disabili-

ties (McNair & Swartz, 1997). More

important, this finding may imply that

various community settings outside of

school should be considered as places for

students with severe disabilities to inter-

act with others.

Although many respondents indicated

they were willing to make friends with

students with severe disabilities, insuffi-

cient opportunities to see students with

severe disabilities was reported as a rea-

son for the lack of friends. Physical inte-

gration is an important first step in de-

veloping relationships; however, merely

placing students with disabilities in gen-

eral education settings is not enough to

create actual friendships or social net-

works (e.g., Schnorr, 1997). The pres-

ence of adult teaching assistants was

viewed by study participants as a deter-

rent. Others have reported that when

paraeducators work too closely with stu-

dents with disabilities, it does not allow

typical students and students with dis-

abilities to have natural opportunities to

interact with each other (Giangreco,

Edelman, Luiselli, & MacFarland, 1997).

Although this study suggests some

promising directions for designing inter-

vention strategies, it had several limita-

tions, so the findings must be considered

exploratory and interpreted with cau-

tion. First, the sampling procedures used

in the study could be biased in that only

two schools participated and only one

class per grade was asked to voluntarily

participate. However, the population of

the two schools was similar to that in

other U.S. middle schools (i.e., 46.4% of

schools have a population of more than

750 and 32.4% of schools have a popu-

lation between 500 and 749; National

Center for Educational Statistics, 2000).

The percentage of students with disabil-

ities was also close to the national aver-

age (i.e., 11.26% of those between ages

6 and 17 nationwide compared to 13.6%

of combined population of the schools in

the study; U.S. Department of Educa-

tion, 2001), so the sample in this study

may be similar to other U.S. middle

schools. In addition, although there was

a discrepancy in response rates between

the two schools, a statistical analysis re-

vealed no significant difference between

the schools in terms of gender and grade

level. The overall response rate of 47%

was somewhat low. Consequently, the re-

sults can only be generalized to adoles-

cents who have characteristics similar to

the responding sample.

Second, the sample size of students

who had friends with severe disabilities

was small, which may impact the external

at UNIV CALGARY LIBRARY on March 25, 2014 foa.sagepub.com Downloaded from

VOLUME 19, NUMBER 4, WINTER 2004

213

validity of the study. Given the limited

sample and small number of participants

who had friends with severe disabilities,

the findings should be interpreted cau-

tiously.

Third, this research relied solely on

survey methodology, which might result

in subjective data. The respondents may

have had a positive response bias and

provided socially acceptable answers

(Heppner et al., 1992). Therefore, the

results may not be an accurate indicator

of what typical students expect about

friendships with peers with severe dis-

abilities. Because social relationships, in-

cluding friendships, are multidimen-

sional and have a dyadic structure, more

systematic explorations (e.g., long-term

direct observations, in-depth interviews

with both students with and without dis-

abilities as well as teachers and parents,

and comparative investigations on friend-

ship expectations for students with and

without disabilities) are necessary. Addi-

tionally, more research is needed on the

MSF to further investigate its psycho-

metric properties.

Even with these limitations, this study

has several implications for future re-

search efforts and educational practice.

First, typical students would like to have

close relationships with their peers with

severe disabilities, but limited opportuni-

ties, peer pressure, and the presence of

paraprofessionals were found to be pos-

sible explanations for why they had diffi-

culty in developing friendships. To sup-

port students with severe disabilities in

the development of peer relationships,

they need more opportunities to meet

peers without disabilities both during and

after school, particularly during sport

activities. Additionally, the roles and re-

sponsibilities of paraeducators need to be

reexamined, particularly if they interfere

with interactions between students with

and without disabilities.

Second, the designers of friendship pro-

grams need to be aware of the social net-

works that exist among typical students.

The dynamics of friendship in young

adolescence may not be simple, so re-

searchers and practitioners should have

extensive knowledge about how typical

students form relationships with others,

how social networks can be constituted

and maintained, what skills are necessary

to enter a certain group of friends, and

what, if any, pressures exist among the

members of a group.

Third, age or grade level may play an

important role in friendship expectations,

and specific strategies should be devel-

oped with age or grade level as a consid-

eration. It may also be appropriate to in-

corporate social relationship programs

into transition programs for students as

they enter middle school. Students in

middle school may be very volatile in

terms of social needs and emotional change

(Bowers, 1995), so systematic transition

approaches could be effective at this

stage while providing many natural op-

portunities to interact with others.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Kyoung Gun Han, PhD, is a visiting assistant

professor in the Department of Special Educa-

tion, Kongju National University, Chung-

nam, Korea. His current interests include in-

struction related to students with significant

disabilities and their social relationships with

typical peers. Janis G. Chadsey, PhD, is a pro-

fessor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-

Champaign. Her research interests include the

social inclusion of individuals with disabilities

into all settings, transition, and instructional

strategies for teaching communication skills to

individuals with significant disabilities. Ad-

dress: Janis G. Chadsey, Department of Special

Education, University of Illinois, Champaign,

IL 61820; e-mail: chadsey@uiuc.edu

NOTE

The MSF is available from the authors on re-

quest.

REFERENCES

Berndt, T. J. (1986). Childrens comments

about their friendships. In M. Perlmutter

(Ed.), Cognitive perspectives on childrens so-

cial and behavioral development (pp. 189

212). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bezilla, R. (Ed.). (1993). Religion in Amer-

ica 19921993. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

Religion Research Center.

Bigelow, B. J., & La Gaipa, J. J. (1980). The

development of friendship values and

choice. In H. B. Foot, A. J. Chapman, &

J. R. Smith (Eds.), Friendship and social re-

lations in children (pp. 1544). New York:

Wiley.

Block, M. E., & Malloy, M. (1998). Attitudes

on inclusion of a player with disabilities in a

regular softball league. Mental Retarda-

tion, 36, 137144.

Blyth, D. A., Hill, J. P., & Thiel, K. S. (1982).

Early adolescents significant others: Grade

and gender differences in perceived rela-

tionships with familial and nonfamilial

adults and young people. Journal of Youth

and Adolescence, 11, 425450.

Bowers, R. S. (1995). Early adolescent social

and emotional development: A construc-

tivist perspective. In M. J. Wavering (Ed.),

Educating young adolescence: Life in the

middle (pp. 79110). New York: Garland.

Buhrmester, D. (1990). Intimacy of friend-

ship, interpersonal competence, and adjust-

ment during preadolescence and adoles-

cence. Child Development, 61, 11011111.

Buhrmester, D., & Furman, W. (1986). The

changing functions of friends in childhood:

A neo-Sullivan perspective. In V. J. Derlega

& B. A. Winstead (Eds.), Friendship and so-

cial interaction (pp. 4162). New York:

Springer-Verlag.

Clark, M. L., & Ayers, M. (1993). Friendship

expectations and friendship evaluations:

Reciprocity and gender effects. Youth and

Society, 24, 299313.

Clark, M. L., & Bittle, M. L. (1992). Friend-

ship expectations and the evaluation of

present friendships in middle childhood

and early adolescence. Child Study Journal,

22, 115135.

DuBois, D. L., & Hirsch, B. J. (1993).

School/nonschool friendship patterns in

early adolescence. Journal of Early Adoles-

cence, 13, 102122.

Evans, I. M., Salisbury, C. L., Palombaro,

M. M., Berryman, J., & Hollowood, T. M.

(1992). Peer interactions and social accep-

tance of elementary-age children with se-

vere disabilities in an inclusive school. Jour-

nal of the Association for Persons with Severe

Handicaps, 17, 205212.

Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Chil-

drens perceptions of the personal relation-

ships in their social networks. Developmen-

tal Psychology, 21, 10161024.

Giangreco, M. F., Edelman, S. W., Luiselli,

T. E., & MacFarland, S. E. C. (1997).

Helping or hovering? Effects of instruc-

tional assistant proximity on students with

disabilities. Exceptional Children, 64, 718.

Grenot-Scheyer, M. (1994). The nature of in-

teractions between students with severe dis-

abilities and their friends and acquaintances

without disabilities. Journal of the Associa-

at UNIV CALGARY LIBRARY on March 25, 2014 foa.sagepub.com Downloaded from

FOCUS ON AUTISM AND OTHER DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

214

tion for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 19,

253262.

Guralnick, M. J., & Groom, J. M. (1988).

Friendships of preschool children in main-

streamed playgroups. Developmental Psy-

chology, 24, 595604.

Hall, L. J., & McGregor, J. A. (2000). A fol-

low-up study of the peer relationships of

children with disabilities in an inclusive

school. The Journal of Special Education,

34, 114126.

Hamre-Nietupski, S. (1993). How much time

should be spent on skill instruction and

friendship development? Preferences of par-

ents of students with moderate and severe/

profound disabilities. Education and Train-

ing in Mental Retardation, 28, 220231.

Hartup, W. W. (1992). Friendships and their

developmental significance. In H. McGurk

(Ed.), Child social development: Contempo-

rary perspectives (pp. 175205). Hillsdale,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Hendrickson, J. M., Shokoohi-Yekta, M.,

Hamre-Nietupski, S., & Gable, R. A.

(1996). Middle and high school students

perceptions on being friends with peers

with severe disabilities. Exceptional Chil-

dren, 63, 1928.

Heppner, P. P., Kivlighan, D. M., & Wam-

pold, B. E. (1992). Research design in coun-

seling. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Hirsch, B. J., & DuBois, D. L. (1989). The

school/nonschool ecology of early adoles-

cent friendships. In D. Belle (Ed.), Chil-

drens social networks and supports (pp. 164

173). New York: Wiley.

Kaiser, A. P. (2000). Teaching functional

communication skills. In M. E. Snell &

F. Brown (Eds.), Instruction of students

with severe disabilities (5th ed., pp. 453

492). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Karweit, N. (1983). Extracurricular activities

and friendship selection. In J. L. Epstein &

N. Karweit (Eds.), Friends in school: Pat-

terns of selection and influence in secondary

schools (pp. 131139). New York: Academic

Press.

Kennedy, C., & Fisher, D. (2001). Inclusive

middle schools. Baltimore: Brookes.

Kishi, G. S., & Meyer, L. H. (1994). What

children report and remember: A six-year

follow-up of the effects of social contact be-

tween peers with and without severe dis-

abilities. Journal of the Association for Per-

sons with Severe Handicaps, 19, 277288.

Krajewski, J., & Flaherty, T. (2000). Attitudes

of high school students toward individuals

with mental retardation. Mental Retarda-

tion, 38, 154162.

McNair, J., & Rusch, R. R. (1991). Parent in-

volvement in transition programs. Mental

Retardation, 29, 93101.

McNair, J., & Swartz, S. L. (1997). Local

church support to individuals with devel-

opmental disabilities. Education and Train-

ing in Mental Retardation and Develop-

mental Disabilities, 32, 304312.

McNelles, L. R., & Connolly, J. A. (1999).

Intimacy between adolescent friends: Age

and gender differences in intimate affect

and intimate behaviors. Journal of Research

on Adolescence, 9, 143159.

Meyer, L. H., Park, H. S., Grenot-Scheyer,

M., Schwartz, I. S., & Harry, B. (1998).

Making friends: The influences of culture

and development. Baltimore: Brookes.

National Center for Educational Statistics.

(2000). In the middle: Characteristics of

public schools with a focus on middle schools.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Ed-

ucation.

Peck, C. A., Donaldson, J., & Pezzoli, M.

(1990). Some benefits nonhandicapped

adolescents perceive for themselves from

their social relationships with peers who

have severe handicaps. Journal of the Asso-

ciation for Persons with Severe Handicaps,

15, 241249.

Raffaelli, M., & Duckett, E. (1989). We

were just talking: Conversations in early

adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adoles-

cence, 18, 568582.

Rice, F. P. (1987). The adolescent: Develop-

ment, relationships, and culture (5th ed.).

Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Schnorr, R. F. (1997). From enrollment to

membership: Belonging in middle and

high school classes. Journal of the Associa-

tion for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 22,

115.

Traustadottir, R. (1993). The gendered con-

text of friendships. In A. N. Amado (Ed.),

Friendships and community connections be-

tween people with and without developmen-

tal disabilities (pp. 109127). Baltimore:

Brookes.

U.S. Department of Education. (2001). To

assure the free appropriate public education

of all children with disabilities: Twenty-third

annual report to Congress on the implemen-

tation of the Individuals with Disabilities

Education Act. Washington, DC: Author.

Zetlin, A. G., & Murtaugh, M. (1988).

Friendship patterns of mildly learning han-

dicapped and nonhandicapped high school

students. American Journal on Mental Re-

tardation, 92, 447453.

at UNIV CALGARY LIBRARY on March 25, 2014 foa.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Вам также может понравиться

- 30 4 2 Maths StandardДокумент16 страниц30 4 2 Maths Standardanirban7172Оценок пока нет

- Getting Acquainted Through DialogsДокумент13 страницGetting Acquainted Through DialogsAriefful CiezboyОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- Week 14 (Part 4) - Integrals Yielding Inverse Trigonometric FunctionsДокумент12 страницWeek 14 (Part 4) - Integrals Yielding Inverse Trigonometric FunctionsqweqweОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- 04 Skema Tlo Mte3101Документ6 страниц04 Skema Tlo Mte3101Siti KhadijahОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- CC10 Coplanar Forces in GeneralДокумент18 страницCC10 Coplanar Forces in GeneralSaqlain KhalidОценок пока нет

- Banao Elementary School Annual Performance ReportДокумент2 страницыBanao Elementary School Annual Performance ReportAjie TeopeОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- June 2016 Mark Scheme 11 PDFДокумент2 страницыJune 2016 Mark Scheme 11 PDFjohnОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Mikho ResumeДокумент2 страницыMikho Resumeapi-283579568Оценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Calculus For EngineersДокумент347 страницCalculus For EngineersAwal SyahraniОценок пока нет

- 0580 Y15 SP 2Документ12 страниц0580 Y15 SP 2RunWellОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- SMO 2016 Senior Section Round 1 Questions and SolutionsДокумент7 страницSMO 2016 Senior Section Round 1 Questions and SolutionsIwymic MathcontestОценок пока нет

- Challenge 4 AnswersДокумент11 страницChallenge 4 Answersmohammed mahdyОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Quant Checklist 136 PDF 2022 by Aashish AroraДокумент70 страницQuant Checklist 136 PDF 2022 by Aashish AroraRajnish SharmaОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Diff CalДокумент40 страницDiff CalRobertBellarmineОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Application For Original Degree-2013Документ6 страницApplication For Original Degree-2013SIVA KRISHNA PRASAD ARJA0% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Continuity & Differentibilitytheory & Solved & Exercise Module-4Документ11 страницContinuity & Differentibilitytheory & Solved & Exercise Module-4Raju SinghОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Grade 10 English Exam Papers 2016Документ3 страницыGrade 10 English Exam Papers 2016Kevin40% (5)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- Y6 White Rose Problems Mon ThursДокумент18 страницY6 White Rose Problems Mon ThursKki YuОценок пока нет

- Registration Form Scilympics16Документ17 страницRegistration Form Scilympics16Emel AmboОценок пока нет

- FSJM - Semi-Final-20 March 2021: Start For All ParticipantsДокумент3 страницыFSJM - Semi-Final-20 March 2021: Start For All ParticipantsTapas HiraОценок пока нет

- Uptown School - Admission RequirementsДокумент2 страницыUptown School - Admission RequirementsfarraheshamОценок пока нет

- Coordinate Geometry SolutionsДокумент20 страницCoordinate Geometry SolutionsWeird DemonОценок пока нет

- Applications of HzVert CurvesДокумент5 страницApplications of HzVert CurvesteamОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Conic Sections Worksheet: Equations, Foci, EccentricitiesДокумент2 страницыConic Sections Worksheet: Equations, Foci, EccentricitiesbhartОценок пока нет

- Worksheet On Set and Venn DiagramДокумент20 страницWorksheet On Set and Venn DiagramMario Bacani Pidlaoan100% (1)

- Newsletter Vol 1Документ3 страницыNewsletter Vol 1Yakamia Primary SchoolОценок пока нет

- Trigonometry One Shot BouncebackДокумент125 страницTrigonometry One Shot BouncebackMayank VishwasОценок пока нет

- Milam Candice ResumeДокумент1 страницаMilam Candice Resumeapi-277775718Оценок пока нет

- 01 8th Nift MathsДокумент12 страниц01 8th Nift MathsLandon MitchellОценок пока нет

- Hen Eggs and Anatomical CanonДокумент13 страницHen Eggs and Anatomical CanonIgnacio Colmenero Vargas100% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)