Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Self-Esteem Scores Among Deaf College Students

Загружено:

Elena Lily0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

57 просмотров8 страницThis study asked whether self-esteem scores are significantly different among deaf college students compared across groups based on gender and parents' hearing status and signing ability. Results revealed that gender, age, and the interaction of parent by gender were nonsignificant. Respondents who had at least one deaf parent and signed scored significantly higher than those with hearing parents who could not sign.

Исходное описание:

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документThis study asked whether self-esteem scores are significantly different among deaf college students compared across groups based on gender and parents' hearing status and signing ability. Results revealed that gender, age, and the interaction of parent by gender were nonsignificant. Respondents who had at least one deaf parent and signed scored significantly higher than those with hearing parents who could not sign.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

57 просмотров8 страницSelf-Esteem Scores Among Deaf College Students

Загружено:

Elena LilyThis study asked whether self-esteem scores are significantly different among deaf college students compared across groups based on gender and parents' hearing status and signing ability. Results revealed that gender, age, and the interaction of parent by gender were nonsignificant. Respondents who had at least one deaf parent and signed scored significantly higher than those with hearing parents who could not sign.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 8

Overall, research studies of self-esteem and deafness yield in-

consistent ndings. Some studies indicate a higher incidence

of low self-esteem among deaf individuals than among hearing

individuals (Bat-Chava, 1994; Mulcahy, 1998; Schlesinger,

2000). Other ndings suggest that one must examine this com-

plex phenomenon more closely to understand how deafness

inuences self-concept and self-esteem (Bat-Chava, 2000;

Emerton, 1998; Foster, 1998; Munoz-Baell & Ruiz, 2000;

Stone, 1998). This study asked whether self-esteem scores are

signicantly different among deaf college students compared

across groups based on gender and parents hearing status

and signing ability. The construct of self-esteem was mea-

sured by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, administered us-

ing an American Sign Languagetranslated videotape. Results

revealed that gender, age, and the interaction of parent by gen-

der were nonsignicant. However, respondents who had at

least one deaf parent and signed scored signicantly higher

than those with hearing parents who could not sign and those

with hearing parents who could sign. Overall, self-esteem

scores for all respondents were high. Implications for further

study are discussed.

The question of whether deaf individuals have lower

self-esteem than their hearing counterparts is still open

to debate. Overall, research studies of self-esteem and

deafness yield inconsistent ndings. Some studies have

found a higher incidence of low self-esteem among deaf

individuals than among hearing individuals (Bat-Chava,

1994; Mulcahy, 1998; Schlesinger, 2000). Other ndings

suggest that one must examine this complex phenome-

non more closely to understand how deafness inuences

self-concept and self-esteem (Bat-Chava, 2000; Emer-

ton, 1998; Foster, 1998; Munoz-Baell & Ruiz, 2000;

Stone, 1998). This article presents a study of self-esteem

among deaf college students at Gallaudet University that

addressed the question, Are self-esteem scores signi-

cantly different among deaf college students when com-

pared across groups based on gender and parents hear-

ing and signing ability?

Deafness and Self-Esteem

In a review of the literature, Mulcahy (1998) identies

potentially negative factors that may affect a deaf in-

dividuals self-esteem: poor parental communication

skills, inadequate maternal bonding, feelings of mistrust

due to a sense of inequality and negative attitudes to-

ward deaf people, poor acquisition of American Sign

Language (ASL) skills, lack of appropriate role models,

social isolation, negative body image, lack of a strong

cultural identity, and rejection from family members

and society in general. These ndings have been sup-

ported by other studies (Bat-Chava, 1993, 1994, 2000;

Schlesinger, 2000).

In a meta-analysis study of self-esteem, Bat-Chava

(1993) examined the effects of family and school factors

and the inuence of Deaf group identication. Overall,

she found that deaf children of deaf parents had higher

self-esteem than deaf children of hearing parents. In ad-

dition, self-esteem was higher among deaf people who

used sign language. Related to group identication, the

Self-Esteem Scores Among Deaf College Students: An

Examination of Gender and Parents Hearing Status and

Signing Ability

Teresa V. Crowe

Gallaudet University

Correspondence should be sent toTeresa V. Crowe, Department of Social

Work, Gallaudet University, 800 Florida Avenue, NE, Washington, DC

20002 (e-mail: Teresa.Crowe@gallaudet.edu).

2003 Oxford University Press

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

M

a

y

2

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

j

d

s

d

e

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

more strongly one identied with being a member of the

Deaf community, the higher the self-esteem scores. In a

1994 study, Bat-Chava found that deaf people who grew

up in environments that included other deaf people who

used sign language were more likely to identify with the

Deaf community in adulthood, thus enhancing self-

esteem. Interestingly, Bat-Chava (1993, 1994) found

that although group identication (e.g., having prima-

rily deaf friends, involvement in the Deaf community)

contributed to higher self-esteem, group membership

(e.g., having a level of hearing loss, but not feeling proud

of being a member in the cultural group) was indicative

of lower self-esteem.

Deafness can be seen as an experience that limits in-

teraction and linguistic feedback from the social envi-

ronment (Finn, 1995; Schlesinger, 2000). In addition,

negative parental reactions about the childs deafness,

as well as lack of understanding about means of interact-

ing with a deaf child, can result in inappropriate family

interactions that contribute to negative self-perceptions.

Furthermore, negative social perceptions may validate

and strengthen negative internal self-perceptions (Finn,

1995; Triandis, 1996). Finally, as development pro-

gresses, potential difculties with communicating de-

sires, thoughts, and experiences can arise due to previous

social shaping, resulting in social isolation, depression,

and low self-esteem among others. The reverse is also

true. Positive familial interactions can enhance self-

esteem and support overall functioning.

Deafness, from a communication perspective, iso-

lates members from the society at large, resulting in cog-

nitive and interpersonal deprivation (Clymer, 1995).

Distorted self-concepts can develop if deaf people per-

ceive themselves as decient in relation to the hearing

people around them. In general, Clymer suggests that

hearing people lay the burden of communication on the

deaf person. This may contribute to negative self-

perceptions and frustration when communication is not

successful.

Family Inuences

Self-image and identity, as well as cultural values and

norms, are often connected to ones experiences within

the family. The fact that most deaf children are born

into hearing families is common knowledge among

those who live and work in the Deaf community (Foster,

1998; Schein, 1974). The impacts of deafness on the

family system have been widely documented (Foster,

1998; LaSasso & Metzger, 1998; Schlesinger, 2000). Yet

communication issues within the family seem to be em-

bedded deeply in the lives of its members.

Communication issues affect the entire family, in-

cluding both hearing and deaf members (Foster, 1998).

Even when hearing family members learn to sign, most

never attain high levels of uency. Thus, a deaf family

member may still be excluded from informal and inci-

dental conversations involving the hearing family mem-

bers. Indeed, Foster notes that deaf youths reported a

preference for interactions with deaf peers to those with

nonsigning family members.

In families with deaf parents, the deaf child learns

language through modeling in the home (LaSasso &

Metzger, 1998). Both parents and child may share a deaf

identity that can help to organize the childs self image

(Emerton, 1998). In addition, a deaf environment can

help to foster a healthy self-concept with common val-

ues. A community of deaf and signing peers has the po-

tential to ll gaps in social interactions inherent in a

hearing community without sign language. In essence, a

deaf environment can help to construct a subculture

through which larger societal values may be interpreted.

Social and Cultural Inuences

Gender

Gender is considered by many to be a cultural phenom-

enon (Peplau, Veniegas, Taylor, & DeBro, 1999; Wade &

Tavris, 1999). Gender, according to Wade and Tavris, is

described as all the duties, rights, and behaviors a cul-

ture considers appropriate for males and females [and]

is a social invention (p. 16). Often, cultural expecta-

tions and roles are ascribed beginning at birth and vary

across cultures.

Social norms, which include the rules and expecta-

tions of group member behavior, inuence virtually all

aspects of life (Peplau et al., 1999). These norms often

establish the boundaries for status and power, accepted

ideology, and stereotypes. Generally, men continue to

have more status and power than women (Wade & Tavris,

1999). These barriers are often difcult for women to

200 Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 8:2 Spring 2003

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

M

a

y

2

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

j

d

s

d

e

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

overcome and continue to contribute to differences in

everyday life, such as employment and salary.

Deafness

Bateman (1998) suggests that the success of the Deaf

community as a minority group relies heavily on the

emergence of successful deaf leaders. Deaf leaders are

created by several positive factors converging to create a

strong and clear sense of self. Bateman identies several

key factors that impede development of these attributes.

He suggests that barriers in family life, school life, com-

munication, type of education, community support,

and visibility of the Deaf community can interfere with

a strong development of leadership skills. Specically,

families that tend to make decisions for the deaf mem-

ber, passivity in school, lack of communication, and lack

of community support and visibility in essence prevent

the deaf individual from developing strong and clear

leadership skills. Indeed, insufcient communication

between the deaf individual and his or her environment

(i.e. family members, school peers, teachers, etc.) may

not only prevent leadership skills but also can convey

negative or conictual messages to the individual.

The inuence of culture also plays a key role in de-

veloping an identity within a social context. Culture,

according to some, exists both inside (subjective) and

outside (objective) of individuals (Mruk, 1999; Singelis,

Bond, Sharkey, & Siu Yiu Lai, 1999). According to

Rosenberg (1981),

[self-concept] is not present at birth but arises out

of social experience and interaction; it both incor-

porates and is inuenced by the individuals location

in the social structure; it is formed within institu-

tional systems, such as the family, school, economy,

church; it is constructed from the materials of the

culture; and it is affected by immediate social and

environmental contexts. (p. 593)

Subjectively, culture exists as internalized beliefs, val-

ues, and interaction patterns. Objectively, culture exists

as part of the environment including religious, political,

and educational institutions. Social systems are the

structures that provide the social context for the indi-

vidual. These systems are a complex and interrelated

network of roles and statuses, which convey the values,

attitudes, norms, and expectations of society to the indi-

vidual. The individual, in turn, interacts with societys

members, presenting a socially constructed image of

self, and receives social evaluations from others.

Individual behavior must always be considered in the

context of culture (Mruk, 1999). Tension between ones

own identity and ones culture is known as cultural dis-

sonance (Mruk, 1999; Rosenberg, 1981). For example,

a hard-of-hearing individual may nd herself feeling

caught between identifying herself as part of hearing cul-

ture or as part of Deaf culture. Consequently, she may

feel that she does not quite t into any particular culture;

this can create internalized tension and anxiety. How-

ever, this is not to say that all individuals would feel ten-

sion. Others may nd themselves able to integrate cul-

tural and individual aspects into a bicultural identity

(Bat-Chava, 2000).

Conicts between dominant and minority group

norms can also create feelings of cultural dissonance. In

fact, Rosenberg (1981) states that the effect of the dis-

sonant cultural context may be even more insidious than

that of direct prejudice (p. 113). Thus, it makes sense

that if minority group members are treated with dis-

dain, one would expect members of that group to have

low self-esteem. If supportive environments help pro-

tect minority group members from the negativity of the

dominant group, members may not necessarily absorb

these negative values.

In summary, deafness can affect an individual in

many areas. Whereas some studies suggest that deafness

itself directly inuences self-esteem, other studies indi-

cate that strong familial, social, and cultural inuences

play a key role in supporting self-esteem. Clearly, there

are numerous inuences at work in the lives of deaf in-

dividuals, their families, and their communities.

This study was part of a larger study that examined

the psychometric properties of a backtranslated, ASL

version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES;

Crowe, in press). The reliability of the ASL version of

the RSES (Cronbach = .784) was deemed adequate

for comparison of other variables collected (see Appen-

dix 1). Information about parental hearing status and

signing ability was gathered on a general demographic

questionnaire. Thus, respondents were not asked to rate

the level of sign language uency in the home. Speci-

cally, the research question examined by this study

Self-Esteem Scores Among Deaf Adults 201

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

M

a

y

2

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

j

d

s

d

e

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

asked whether self-esteem scores are signicantly dif-

ferent among deaf college students when comparing

gender and parents signing ability.

Method

Participants

Two hundred college students completed the ASL ver-

sion of the RSES. Because the study was specically

geared toward those who primarily used ASL, respon-

dents whose data were missing or who reported that

they did not know or use ASL were excluded from the

study. One hundred and fty-two participants reported

both knowing and using ASL, and this sample was used

for all further analyses. Overall, this sample included a

wide range of ages and races. Respondents ranged in age

from 18 to 49 years (M= 24.96, SD = 7.43). The racial

composition of the same was 72.1% White, 11.5%

Black/African American, 7.7% Asian/Pacic Islanders,

4.9% Hispanic, .5% Native American, and 3.3% other.

The mean age of the onset of deafness was 2.65 years

of age (SD = 11.31). Most of the respondents parents

were hearing (76% of fathers, 79% mothers). Most of

the respondents used sign language in the home (64%).

This sample, however, is unique in that the respondents

are college students or staff working in a Deaf environ-

ment, surrounded by sign language and Deaf culture.

Measure

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1991).

The original, self-report, 10-item measure was designed

to measure self-esteem of hearing individuals (see Ap-

pendix 2). The scale is a unidimensional measure and is

scored using a 4-point response format (strongly agree,

agree, disagree, strongly disagree). The scores range

from 10 to 40, with higher scores representing higher

self-esteem. Blascovich and Tomaka report Cronbach al-

phas from .77 to .88. The test-retest correlation was .85

after a 2-week interval and .82 after a 1-week interval in

another study by Fleming and Courtney (1984, cited in

Blascovich & Tomaka, 1991). Cronbachs alpha for the

backtranslated ASL version was .78 (Crowe, in press).

The RSES was translated using a three-stage back

translation method (Brauer, 1993; Crowe, 2002). Trans-

lators were not blind to the study objective. In the rst

stage, a prelingually deaf professional ASL instructor

translated the scale items from written English into

ASL onto a videotape. In the second stage, a certied in-

terpreter, unfamiliar with the RSES, translated the

videotaped version back into written English. In the

third stage, two different individuals, one deaf bilingual

and one hearing bilingual, compared the original and

back translated version for conceptual equivalence. Sug-

gested modications to the signed version were made to

maintain the validity of the original written scale. Am-

biguous items were discussed among the evaluators, and

the scale was videotaped again until a consensus about

the conceptual equivalence of test items was reached.

Procedures

After pilot testing, the videotaped version was shown to

groups of Deaf college students who attended Gal-

laudet University. The directions for completing the

scale and the items were signed on the videotape. Par-

ticipants were allowed approximately 7 seconds to circle

their response on the form provided. The forms did not

have the questions written on them. Instead, respon-

dents circled their response from the following options:

strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree.

Answers were circled corresponding to the appropriate

numbered question. Following the test, respondents

completed a general demographic questionnaire and

answered questions related to the clarity of the video-

tape. The entire process of test administration took ap-

proximately 10 to 15 minutes. Each respondent was paid

$5 for his participation.

Results

A factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) was con-

ducted to compare scores of the RSES as the dependent

variable with two independent variables: gender and

combined category of parents hearing status and par-

ents knowledge of sign language. The independent

variable combined hearing status and signing knowl-

edge was created because all of the respondents with

two deaf parents used sign language in the home. Thus,

202 Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 8:2 Spring 2003

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

M

a

y

2

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

j

d

s

d

e

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

there was no way to compare those with deaf parents

who signed versus those who did not sign. This variable

divided the respondents into three groups: those with at

least one deaf parent, those with hearing parents who

signed, and those with hearing parents who did not sign.

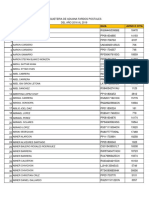

Age was used as a covariate in the analyses. Table 1 pres-

ents the descriptive statistics for the sample.

Table 2 presents the results for the factorial ANOVA.

The main effect of gender was nonsignicant ( p = .961).

The main effect of parents signing knowledge was sig-

nicant ( p = .006). The interaction of gender with par-

ents signing knowledge ( p = .424) was nonsignicant.

Post hoc Bonferroni tests revealed that respondents

whose parents were deaf and signed scored signicantly

higher than those with parents who could not sign ( p =

.015) and those with parents who could sign ( p = .012).

Respondents whose parents were deaf and signing

scored signicantly higher than respondents whose par-

ents were hearing, regardless of whether sign language

was used (see Table 1 for means and standard devia-

tions). There were no signicant differences between

those whose parents were hearing and either signed or

did not sign.

Discussion

Scores did not differ signicantly for male and female re-

spondents. Though there is little research on this issue

in the Deaf community, gender differences appear to

have little impact on self-esteem within this sample. A

possible explanation for this may be Wade and Tavriss

(1999) ndings that when men and women are mutually

dependent and work cooperatively, antagonism between

the genders is much lower. Perhaps when men and

women are in a nurturing and supportive environment,

they feel good about themselves equally. There is less an-

tagonism, which in turn creates a less tense environment

when there is no one group that reigns over another.

In comparison with scores for hearing cohorts, the

mean scores for this sample were somewhat higher than

those reported in other studies. The mean score reported

in a Persian translation study (Shapurian, Hojat, & Nay-

erahmadi, 1987) was 30.41 (SD = 4.22). In a study with

African Americans with low literacy (Westaway & Wol-

marans, 1992), the mean score was 28.01 (SD= 6.02). In

an Afrikaans translation study by Bornman (1999), mean

scores were reported ranging from 15.97 (SD = 3.31) to

17.49 (SD = 2.08). This nding may point to cultural

and environmental factors affecting scores.

Self-esteem scores differed signicantly among re-

spondents whose parents were deaf and hearing. Re-

spondents who had two signing deaf parents (all those

with two deaf parents reported using sign language in the

home) reported higher self-esteem scores than those

who had two hearing parents or those who had one hear-

ing and one deaf parent, regardless of signing ability.

The respondents with deaf parents in this study scored

very high on self-esteem compared to those with hearing

parents who could sign and those with hearing parents

who could not sign. This nding is consistent with other

research ndings that suggest a positive relationship

with family orientation to deafness and self-esteem (Bat-

Chava, 1994, 2000; Clymer, 1995, Schein, 1989). Be-

cause respondents did not evaluate the sign language

abilities of parents, the level of signing prociency

among hearing parents is unknown. There may indeed

be a difference among those with parents who are uent

signers and those with parents who do not sign. Bat-

Self-Esteem Scores Among Deaf Adults 203

Table 1 Descriptive statistics

Parents hearing status and sign use n M(SD)

Parents deaf and sign 28 34.38 (4.82)

Parents hear and sign 72 31.55 (3.51)

Parents hearing and dont sign 52 31.60 (4.02)

Total 152

Dependent variable: score on the RSES.

Table 2 Univariate ANOVA comparing parents signing ability, gender

Effect MS df SS F p

Parent knowledge of sign 88.70 2 177.41 5.216 .006

Gender 4.03 1 4.03 .002 .961

Parent knowledge of sign by gender 14.69 2 29.32 .862 .424

Error 17.01 146 2482.78

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

M

a

y

2

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

j

d

s

d

e

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

Chava (2000) states that a key element in the role of iden-

tity development may be parental hearing status and sign

language usage. She suggests that those who grew up

with deaf parents may be likely to regard deafness as a

cultural phenomenon rather than a disability. In addi-

tion, most hearing parents of deaf children do not use

sign language. Bat-Chava (2000) notes that the minority

of parents who do (approximately 4%) may not neces-

sarily convey the cultural perspective of deafness. In this

respect, deaf students who have Deaf parents may have

not only language accessibility but also role models to

convey cultural, social, and familial values.

Another possible explanation for higher self-esteem

scores for those with Deaf parents may be that the Deaf

community discriminates between those whose families

are Deaf or hearing. In the Deaf community, a culturally

deaf person with Deaf parents is at the top of the power

hierarchy (Kannapell, 1989). Therefore, membership in

the Deaf community is a given, passed on by family lin-

eage. Indeed, White (1999) reports that

while hearing parents struggle with communication

and language choice issues, search for answers from

professionals, and cope with their own grief reac-

tions to the deafness, Deaf parents are already fa-

miliar with the Deaf experience, have social net-

works of support, and are familiar with educational

and community resources for Deaf children. They

usually do not have the prolonged mourning period

that hearing parents experience, and are prepared to

begin communicating with their Deaf infant in sign

language immediately. (pp. 3940)

For offspring of Deaf parents, social and cultural sup-

port may have been established at an early age, thus con-

tributing to a high level of self-esteem.

Overall, all of the respondents in this study scored

high on the self-esteem measure. This is an expected

nding considering that respondents were either stu-

dents or staff who work in a culturally Deaf-oriented en-

vironment. Signed communication is readily accessible

for social gatherings, academic studies, and on-campus

services. Thus, the respondents in this study were in a

linguistically and culturally supportive environment.

The question remains whether Deaf students in pre-

dominantly hearing environments would score as high

on the measure.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

A limitation of the study relates to the sample of re-

spondents. This study included college students, fac-

ulty, and staff who, by present standards, are not repre-

sentative of the deaf population at large. Munoz-Bell

and Ruiz (2000) note that most deaf people tend to be

undereducated with low status jobs and low levels of in-

come. Clearly, the respondents in this sample may have

particular characteristics that make them unique in

comparison to other groups of deaf individuals. There-

fore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to

other groups of deaf individuals.

The academic environment from which the sample

was selected is unique in that it provides a culturally

sensitive atmosphere for socializing, learning, and com-

municating. Although the sample itself may be selective,

a strength of the study was that the data were gathered

within a unique environment that is difcult to replicate

in the larger society, where most deaf individuals are

geographically located in small clusters throughout the

nation.

Another strength of the study was the utilization of

a protocol with regard to translation. Unfortunately,

many ASL translation studies do not include the proce-

dures for backtranslation. Thus, the accuracy of trans-

lation is questionable. Because this study followed pre-

viously established guidelines and carefully planned the

translation, inadequate translation is not likely to be a

mitigating factor.

Implications for Future Research

Because the respondents in this sample scored very high

on the RSES, this study raises several questions. What

possibilities exist for deaf individuals when social envi-

ronments are linguistically accessible and culturally

supportive? What positive outcomes are possible when

discrimination decreases? How can hearing parents pro-

vide not only a rich linguistic environment but a cultural

one as well? If this type of environment is provided, will

that raise the self-esteem of their deaf children?

Clearly, an inuential factor in this study was that

these students, faculty, and staff attended and worked

for a university for the deaf. Self-esteem scores may be

different for those who compare themselves to hearing

204 Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 8:2 Spring 2003

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

M

a

y

2

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

j

d

s

d

e

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

people as a referent group. Likewise, self-esteem scores

may be different for those who are socially isolated from

other deaf people. This has implications for clinical use

as well as further research.

Clinicians must be aware of the complex psycholog-

ical, social, and cultural aspects that may affect the lives

of deaf people. Assumptions about the causes for low or

high self-esteem may be different for deaf and hearing

individuals. The Deaf community is diverse; its mem-

bers have varying needs. Clinicians must take into con-

sideration what clients themselves consider linguisti-

cally accessible and culturally supportive. Qualitative

studies examining self-esteem in deaf persons may pro-

vide insight into the factors that inuence the self-

esteem of deaf individuals. Thus, further research is

needed to ask those questions and to explore the nature

of the deaf experience.

Appendix 1

Participant Demographic Sheet

ID#: ___________

Date of Assessment: _____________

I am (check one): [ ] Deaf [ ] Hard of Hearing

[ ] Hearing

What age did you become deaf ? _________________

Birthdate: ___/___/___Gender:[ ] Male [ ] Female

Race: [ ] Black/African American [ ] White

[ ] Asian/Pacic Islander

[ ] Hispanic/Latino [ ] Native American

[ ] Other: ______________

1. Can you sign using ASL?

[ ] yes [ ] no [ ] I dont know

2. Can you understand someone signing ASL?

[ ] yes [ ] no [ ] I dont know

3. Are you a member of the Deaf community?

[ ] yes [ ] no [ ] Sometimes

4. My mother (or female caretaker) is:

[ ] Deaf [ ] Hearing [ ] Hard of Hearing

5. My father (or male caretaker) is:

[ ] Deaf [ ] Hearing [ ] Hard of Hearing

6. Growing up, did you and your family use sign

language in your house?

[ ] yes [ ] no

7. Growing up, what kind of school did you go to

(check all that apply)?

[ ] Deaf, stayed in dorm [ ] Deaf, day student

[ ] Mainstream program [ ] Hearing, public

Appendix 2

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

1. I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an

equal basis with others.

1. STRONGLY AGREE 2. AGREE

3. DISAGREE 4. STRONGLY DISAGREE

2. I feel that I have a number of good qualities.

3. All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure.

4. I am able to do things as well as most other people.

5. I feel I do not have much to be proud of.

6. I take a positive attitude toward myself.

7. On the whole, I am satised with myself.

8. I wish I could have more respect for myself.

9. I certainly feel useless at times.

10. At times I think I am no good at all.

Reversed-scored items are 3, 5, 8, 9, 10.

Source: Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, J. (1991). The Self-Esteem

Scale. In J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.),

Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes: Volume 1

(pp. 121122). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

References

Bat-Chava, Y. (1993). Antecedents of self-esteem in deaf people: A

meta-analytic review. Rehabilitation Psychology, 38, 221234.

Bat-Chava, Y. (1994). Group identication and self-esteem of deaf

adults. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 494502.

Bat-Chava, Y. (2000). Diversity of deaf identities. American An-

nals of the Deaf, 145, 420428.

Bateman, G. C. (1998). Attitudes of the deaf community toward

political activism. In I. Parasnis (Ed.), Cultural and language

diversity and the deaf experience (pp. 146159). New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, J. (1991). The Self-Esteem Scale. In

J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Mea-

sures of personality and social psychological attitudes: Volume 1

(pp. 121122). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Bornman, E. (1999). Self-image and ethnic identication in

South Africa. Journal of Social Psychology, 139, 411425.

Brauer, B. A. (1993). Adequacy of a translation of the MMPI

into American Sign Language for use with deaf individuals:

Linguistic equivalency issues. Rehabilitation Psychology, 38,

247260.

Self-Esteem Scores Among Deaf Adults 205

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

M

a

y

2

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

j

d

s

d

e

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

Clymer, E. C. (1995). The psychology of deafness: Enhancing

self-concept in the deaf and hearing impaired. Family Ther-

apy, 22, 113120.

Crowe, T. V. (2002). Translation of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem

Scale: A principal components analysis. Social Work Research.

Emerton, R. G. (1998). Marginality, biculturalism, and social

identity of deaf people. In I. Parasnis (Ed.), Cultural and lan-

guage diversity and the deaf experience (pp. 136145). New

York: Cambridge University Press.

Finn, G. (1995). Developing a concept of self. Sign Language

Studies, 86, 117.

Foster, S. B. (1998). Communication experiences of deaf people:

An ethnographic account. In I. Parasnis (Ed.), Cultural and

language diversity and the deaf experience (pp. 117135). New

York: Cambridge University Press.

Kannapell, B. (1989). Inside the deaf community. In S. Wilcox

(Ed.), American deaf culture: An anthology (pp. 128). Burtons-

ville, MD: Linstok Press.

LaSasso, C. J., & Metzger, M. A. (1998). An alternate route for

preparing deaf children for BiBi programs: The home lan-

guage as L1 and cued speech for conveying traditionally spo-

ken languages. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education,

3(4), 265289.

Mulcahy, R. T. (1998). Cognitive self-appraisal of depression and self-

concept: Measurement alternatives for evaluating affective states.

Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Gallaudet University.

Munoz-Bell, I. M., & Ruiz, M. T. (2000). Empowering the deaf.

Let the deaf be deaf. Journal of Epidemiological Community

Health, 54, 4044.

Mruk, C. J. (1999). Self-esteem: Research, theory, and practice. New

York: Springer.

Peplau, L. A., Veniegas, R. C., Taylor, P. L, & DeBro, S. C. (1999).

Sociocultural perspectives on the lives of women and men. In

L. Peplau, S. DeBro, R. Veniegas, & P. Taylor (Eds.), Gender,

culture, and ethnicity: Current research about women and men

(pp. 2337). Mountain View, CA: Mayeld.

Rosenberg, M. (1981). The self-concept: Social product and so-

cial force. In R. H. Turner, Social psychology: Sociological per-

spectives. New York: Basic Books.

Schein, J. D. (1989). At home among strangers. Washington, DC:

Gallaudet University Press.

Schlesinger, H. S. (2000). A developmental model applied to

problems of deafness. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Edu-

cation, 5(4), 349361.

Shapurian, R., Hojat, M., & Nayerahmadi, H. (1987). Psycho-

metric characteristics and dimensionality of a Persian version

of Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Perceptual and Motor Skills,

65, 2734.

Singelis, T. M., Bond, M. H., Sharkey, W. F., & Siu Yiu Lai, C.

(1999). Unpackaging cultures inuence on self-esteem and

embarrassability. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30,

315341.

Stone, J. B. (1998). Minority empowerment and the education of

deaf people. In I. Parasnis (Ed.), Cultural and language diver-

sity and the deaf experience (pp. 171180). New York: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Triandis, H. C. (1996). The psychological measurement of cul-

tural syndromes. American Psychologist, 51, 407413.

Wade, C., & Tavris, C. (1999). Gender and culture. In L. Peplau,

S. DeBro, R. Veniegas, & P. Taylor (Eds.), Gender, culture, and

ethnicity: Current research about women and men (pp. 1522).

Mountain View, CA: Mayeld.

Westaway, M. S., & Wolmarans, L. (1992). Depression and self-

esteem: Rapid screening for depression in Black, low literacy,

hospitalized, tuberculosis patients. Social Science Medicine,

35, 13111315.

White, B. J. (1999). The effect of perceptions of social support and per-

ceptions of entitlement on family functioning in deaf-parented

adoptive families. Doctoral dissertation, The Catholic Uni-

versity of America.

Received December 14, 2001; revisions received March 29, 2002;

accepted April 26, 2002

206 Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 8:2 Spring 2003

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

M

a

y

2

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

j

d

s

d

e

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

Вам также может понравиться

- Chapter 2 - Sample 2Документ15 страницChapter 2 - Sample 2Je CoОценок пока нет

- The Voice of Adolescents: Autonomy from Their Point of ViewОт EverandThe Voice of Adolescents: Autonomy from Their Point of ViewОценок пока нет

- Cog in OldsДокумент21 страницаCog in Oldshdorina10-1Оценок пока нет

- Fowler and Soliz (2010) JLSP - Responses of Young Adult Grandchildren To Grandparents' Painful Self-Disclosures - JLSP VersionДокумент26 страницFowler and Soliz (2010) JLSP - Responses of Young Adult Grandchildren To Grandparents' Painful Self-Disclosures - JLSP VersionCraig FowlerОценок пока нет

- IC dịchДокумент9 страницIC dịchHoang vyОценок пока нет

- Literaturereview PortfolioДокумент14 страницLiteraturereview Portfolioapi-272642588Оценок пока нет

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region X - Northern Mindanao Division of Misamis OrientalДокумент12 страницRepublic of The Philippines Department of Education Region X - Northern Mindanao Division of Misamis OrientalkendieОценок пока нет

- Emotional and behavioral problems and academic achievement impact of demographic and intellectual ability among early adolescent students of government and private schoolsОт EverandEmotional and behavioral problems and academic achievement impact of demographic and intellectual ability among early adolescent students of government and private schoolsОценок пока нет

- Families and Social Interaction: Cultivation. These Children's Involvement in These Activities Provides Them Various LifeДокумент2 страницыFamilies and Social Interaction: Cultivation. These Children's Involvement in These Activities Provides Them Various LifeDavid Arthur SteeleОценок пока нет

- Leigh - Inclusive Education and Personal DevelopmentДокумент10 страницLeigh - Inclusive Education and Personal DevelopmentPablo VasquezОценок пока нет

- Elusive Adulthoods: The Anthropology of New MaturitiesОт EverandElusive Adulthoods: The Anthropology of New MaturitiesDeborah DurhamОценок пока нет

- Content ServerДокумент16 страницContent ServerMelindaDuciagОценок пока нет

- Having A Sibling With A Developmental DisabilityДокумент15 страницHaving A Sibling With A Developmental Disabilityapi-604646074Оценок пока нет

- 3 I'S 1 Q2M3 Sharing Your Research (Presenting and Revising A Written Research Report)Документ8 страниц3 I'S 1 Q2M3 Sharing Your Research (Presenting and Revising A Written Research Report)Antonette JonesОценок пока нет

- Final Practicial ResearchДокумент9 страницFinal Practicial ResearchMark VirgilОценок пока нет

- Module 1 Essay QuestionsДокумент7 страницModule 1 Essay QuestionsadhayesОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Generation Gap On Using LanguageДокумент8 страницThe Effect of Generation Gap On Using Languagedanu saputroОценок пока нет

- Influence of Family Background On The Academic Achievement of Senior Secondary School StudentДокумент59 страницInfluence of Family Background On The Academic Achievement of Senior Secondary School StudentDaniel Obasi100% (1)

- A Qualitative Investigation of Middle SiblingsДокумент8 страницA Qualitative Investigation of Middle SiblingsCharmaine SorianoОценок пока нет

- Persuasion EffectДокумент5 страницPersuasion Effectapi-455430475Оценок пока нет

- Patterns and Profiles of Promising Learners from PovertyОт EverandPatterns and Profiles of Promising Learners from PovertyОценок пока нет

- Bullying: Age DifferencesДокумент8 страницBullying: Age Differencesgenesis gonzalezОценок пока нет

- Peer Influenceson Attitudesand BehaviorsДокумент17 страницPeer Influenceson Attitudesand BehaviorsNoor HafizaОценок пока нет

- Broken Family ThesisДокумент9 страницBroken Family ThesisMa Angelica TugonОценок пока нет

- tmp2079 TMPДокумент9 страницtmp2079 TMPFrontiersОценок пока нет

- 08 - Chapter 3Документ17 страниц08 - Chapter 3djamel eddineОценок пока нет

- Wilkinson2009 - SCHOOL CULTURE AND THE WELL-BEING OF SAME-SEX - ATTRACTED YOUTHДокумент27 страницWilkinson2009 - SCHOOL CULTURE AND THE WELL-BEING OF SAME-SEX - ATTRACTED YOUTHAlice ChenОценок пока нет

- An Overview of Family DevelopmentДокумент18 страницAn Overview of Family DevelopmentMiyangОценок пока нет

- Waldegrave Et Al 2009Документ18 страницWaldegrave Et Al 2009Barbara CFОценок пока нет

- CODA's ExperiencesДокумент9 страницCODA's ExperiencesBetül Özsoy TanrıkuluОценок пока нет

- Practitioner's Guide to Empirically Based Measures of Social SkillsОт EverandPractitioner's Guide to Empirically Based Measures of Social SkillsОценок пока нет

- Summary in GAS PDFДокумент6 страницSummary in GAS PDFRose CalisinОценок пока нет

- Northland Community and Technical College Occupational Therapy Assistant Program Critically Appraised Topics Assignment Bailly SagerДокумент12 страницNorthland Community and Technical College Occupational Therapy Assistant Program Critically Appraised Topics Assignment Bailly Sagerapi-285542134Оценок пока нет

- Why Does Gender Matter Counteracting Stereotypes With Young Children Olaiya E Aina and Petronella A CameronДокумент10 страницWhy Does Gender Matter Counteracting Stereotypes With Young Children Olaiya E Aina and Petronella A CameronAnnie NОценок пока нет

- Attachment and Bonding in Indian Child WelfareДокумент4 страницыAttachment and Bonding in Indian Child WelfareSofiaОценок пока нет

- Sociology 2710. Final ExamДокумент6 страницSociology 2710. Final ExamHương Thảo HồОценок пока нет

- CommunicationДокумент1 страницаCommunicationNguyen Hai MinhОценок пока нет

- Infant-Language, Shyness and SocialContextДокумент9 страницInfant-Language, Shyness and SocialContextJuan Lino Fernandez GonzalezОценок пока нет

- Bush & James JR 2020 - Adolescents in Individualistics CulturesДокумент11 страницBush & James JR 2020 - Adolescents in Individualistics Culturespsi.valterdambrosioОценок пока нет

- An Exploratory Investigation of Jealousy in The FamilyДокумент14 страницAn Exploratory Investigation of Jealousy in The FamilyKanakОценок пока нет

- Single Parenting and Children EducationДокумент74 страницыSingle Parenting and Children EducationAbdullai Lateef100% (1)

- Contexts of DevelopmentДокумент19 страницContexts of Developmentellenginez180Оценок пока нет

- PRACTICAL RESEARCH 1 Group 4Документ20 страницPRACTICAL RESEARCH 1 Group 4daling.sophianoreenОценок пока нет

- Communication in Divorced Families With ChildrenДокумент9 страницCommunication in Divorced Families With ChildrenElla Grace MierОценок пока нет

- Sex Differences in Social DomainsДокумент6 страницSex Differences in Social DomainsVictor MangomaОценок пока нет

- Psyc339 - Term Paper FinalДокумент15 страницPsyc339 - Term Paper FinalAaron BuckleyОценок пока нет

- Jay PDFДокумент33 страницыJay PDFYSJOS100% (1)

- Family Relationships Research PaperДокумент6 страницFamily Relationships Research Paperfysfs7g3100% (1)

- Decision Making For ManagersДокумент4 страницыDecision Making For ManagersMohit YdvОценок пока нет

- Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Treatment of Abused and Neglected Children and Their Families: It Takes a VillageОт EverandMultidisciplinary Approaches to the Treatment of Abused and Neglected Children and Their Families: It Takes a VillageОценок пока нет

- INTRODUCTION Revised CompleteДокумент5 страницINTRODUCTION Revised CompleteSheena ChanОценок пока нет

- Mubarak 1-3 ProjectДокумент45 страницMubarak 1-3 ProjectAbdullai LateefОценок пока нет

- T.O. CAOT Position StatementДокумент3 страницыT.O. CAOT Position StatementElena LilyОценок пока нет

- TEACHER Training Thomas GordonДокумент183 страницыTEACHER Training Thomas GordonElena Lily100% (3)

- STILUL de UMOR Humor Style QuestionaireДокумент13 страницSTILUL de UMOR Humor Style QuestionaireElena LilyОценок пока нет

- Socioeconomic Status and ObesityДокумент16 страницSocioeconomic Status and ObesityElena LilyОценок пока нет

- Early Intervention in Deafness and Autism: One Family's Experiences, Reflections, and RecommendationsДокумент7 страницEarly Intervention in Deafness and Autism: One Family's Experiences, Reflections, and RecommendationsElena LilyОценок пока нет

- Anika Mombauer - Uzroci Izbijanja Prvog Svetskog Rata + BiografijaДокумент6 страницAnika Mombauer - Uzroci Izbijanja Prvog Svetskog Rata + BiografijaDukisa21Оценок пока нет

- Devolution in KenyaДокумент143 страницыDevolution in Kenyajtmukui2000Оценок пока нет

- Complete Notes 4 PolityДокумент108 страницComplete Notes 4 PolityPraveenkumar Aepuri100% (1)

- Elizabeth I SummaryДокумент1 страницаElizabeth I SummaryNataliaОценок пока нет

- Race, Class & MarxismДокумент11 страницRace, Class & MarxismCritical Reading0% (1)

- Jobactive: Failing Those It Is Intended To ServeДокумент239 страницJobactive: Failing Those It Is Intended To ServeAnonymous Gl5K9pОценок пока нет

- Social Studies 20-1 Unit 2 TestДокумент5 страницSocial Studies 20-1 Unit 2 Testapi-491879765Оценок пока нет

- Air University, Shadow of Politics On SportsДокумент13 страницAir University, Shadow of Politics On SportsArslan Kiani100% (1)

- Policy Sexual HarrasmentДокумент7 страницPolicy Sexual HarrasmentPrecious Mercado QuiambaoОценок пока нет

- Listado de Paqueteria de Aduana Fardos Postales PDFДокумент555 страницListado de Paqueteria de Aduana Fardos Postales PDFyeitek100% (1)

- Moef&cc Gazette 22.12.2014Документ4 страницыMoef&cc Gazette 22.12.2014NBCC IPOОценок пока нет

- CSS-Essay Paper 2006Документ1 страницаCSS-Essay Paper 2006Raza WazirОценок пока нет

- MatuteДокумент299 страницMatuteJorge Yacer Nava QuinteroОценок пока нет

- Final Affidavit of Illegal Discriminatory Practice-Gentry, Mirella 2019Документ12 страницFinal Affidavit of Illegal Discriminatory Practice-Gentry, Mirella 2019FOX 61 WebstaffОценок пока нет

- Official Ballot Ballot ID: 25020015 Precinct in Cluster: 0048A, 0048B, 0049A, 0049BДокумент2 страницыOfficial Ballot Ballot ID: 25020015 Precinct in Cluster: 0048A, 0048B, 0049A, 0049BSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Administrative LiteracyДокумент87 страницAdministrative LiteracyPoonamОценок пока нет

- Unit 8: Sad Experiences in Europe, Rizal'S 2Nd Homecoming, Hongkong Medical Practice and Borneo Colonization ProjectДокумент21 страницаUnit 8: Sad Experiences in Europe, Rizal'S 2Nd Homecoming, Hongkong Medical Practice and Borneo Colonization ProjectMary Abigail LapuzОценок пока нет

- Apllication FormДокумент2 страницыApllication FormDhonato BaroneОценок пока нет

- 1940 Decade ProjectДокумент24 страницы1940 Decade Projectapi-307941153Оценок пока нет

- Lesson Element Norms and Values ActivityДокумент6 страницLesson Element Norms and Values ActivityDianne UdtojanОценок пока нет

- Leadership Reflection AssignmentДокумент4 страницыLeadership Reflection AssignmentRachel GertonОценок пока нет

- SK 10th Regular SessionДокумент2 страницыSK 10th Regular SessionSK PinagsamaОценок пока нет

- Ad From Catholics For Marriage Equality Washington StateДокумент1 страницаAd From Catholics For Marriage Equality Washington StateNational Catholic ReporterОценок пока нет

- Pink TaxДокумент5 страницPink TaxussyfitriyaОценок пока нет

- Official Recognition of Kenyan Sign LanguageДокумент10 страницOfficial Recognition of Kenyan Sign LanguageJack OwitiОценок пока нет

- English Comprehension: CanadaДокумент4 страницыEnglish Comprehension: CanadaBlassius LiewОценок пока нет

- Population Disadvantage GDI 2005Документ71 страницаPopulation Disadvantage GDI 2005Incoherency100% (12)

- Ela Lifework 9 2f11 - Poor Boys Rich Neighborhood - ArticleДокумент7 страницEla Lifework 9 2f11 - Poor Boys Rich Neighborhood - Articleapi-265528988Оценок пока нет

- PIL ReviewerДокумент23 страницыPIL ReviewerRC BoehlerОценок пока нет

- Non ViolenceДокумент4 страницыNon ViolencezchoudhuryОценок пока нет