Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

JOYCE (Rural Problems)

Загружено:

Hayley GuyИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

JOYCE (Rural Problems)

Загружено:

Hayley GuyАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Rural Problems

For the past four decades, rural development and rural reform have been an area of

concern of both government and non-government organization. Pres. Ramos said, the rural folks

have to be brought into the economic mainstream and their access to growth centered improved.

While improvements have been done for the rural areas, much more needs to be done. The rural

areas have considerably lagged behind Metro Manila and other urban centers. The plight of rural

folks has been far from rosy.

Poverty

Poverty and inequality in the Philippines remains a challenge. In the past four decades,

the proportion of households living below the official poverty line has declined slowly and

unevenly and poverty reduction has been much slower than in neighboring countries such as the

People's Republic of China, Indonesia, Thailand, and Viet Nam. Economic growth has gone

through boom and bust cycles, and recent episodes of moderate economic expansion have had

limited impact on the poor. Great inequality across income brackets, regions, and sectors, as well

as unmanaged population growth, are considered some of the key factors constraining poverty

reduction efforts.

About half of the Philippines 88 million people live in rural areas. Poverty is most severe

and most widespread in these areas and almost 80 per cent of the countrys poor people live

there. Agriculture is the primary and often only source of income for poor rural people, most of

whom depend on subsistence farming and fishing for their livelihoods. In general, illiteracy,

unemployment and the incidence of poverty are higher among indigenous peoples and people

living in the upland areas. Overall, more than a third of the people in the Philippines live in

poverty. The poorest of the poor are the indigenous peoples, small-scale farmers who cultivate

land received through agrarian reform, landless workers, fishers, people in upland areas and

women. There are substantial differences in the level of poverty between the regions and

provinces and the poverty gap between urban and rural areas is widening. Indigenous people

living in highly fragile and vulnerable ecosystems, people in the uplands of the Cordillera

highlands and on Mindanao Island are among the poorest in the country.

The causes of poverty in rural areas in the Philippines vary widely from island to island. Among

the causes of rural poverty are a decline in the productivity and profitability of farming, smaller

farm sizes and unsustainable practices that have led to deforestation and depleted fishing waters.

Rural areas lag behind in economic growth and they have higher underemployment. This is

partly because poor people have little access to productive assets and business opportunities.

They have few non-farm income-generating activities, and people lack access to microfinance

services and affordable credit. Some vulnerable groups also face specific problems. For example,

indigenous peoples have high illiteracy rates and are affected by the encroachment of modern

technology and cultures onto traditional norms and practices. Fishers face continuing reduction

in their catches and they have few opportunities or skills outside of fishing. Women have limited

roles outside of marketing and family responsibilities.

Causes of Poverty

The main causes of poverty in the country include the following:

low to moderate economic growth for the past 40 years;

low growth elasticity of poverty reduction;

weakness in employment generation and the quality of jobs generated;

failure to fully develop the agriculture sector;

high inflation during crisis periods;

high levels of population growth;

high and persistent levels of inequality (incomes and assets), which dampen the positive

impacts of economic expansion; and

recurrent shocks and exposure to risks such as economic crisis, conflicts, natural disasters,

and environmental poverty.

Key Findings

The report's key findings include the following:

Economic growth did not translate into poverty reduction in recent years;

Poverty levels vary greatly by regions;

Poverty remains a mainly rural phenomenon though urban poverty is on the rise;

Poverty levels are strongly linked to educational attainment;

The poor have large families, with six or more members;

Many Filipino households remain vulnerable to shocks and risks;

Governance and institutional constraints remain in the poverty response;

There is weak local government capacity for implementing poverty reduction programs;

Deficient targeting in various poverty programs;

There are serious resource gaps for poverty reduction and the attainment of the MDGs by

2015;

Multidimensional responses to poverty reduction are needed; and

Further research on chronic poverty is needed.

The report comprehensively analyzes the causes of poverty and recommends ways to accelerate

poverty reduction and achieve more inclusive growth. In the immediate and short term there is a

need to enhance governments poverty reduction strategy and involve key sectors for a collective

and coordinated response to the problem. In the medium and long term the government should

continue to pursue key economic reforms for sustained and inclusive growth.

Rural education

The Problem of Rural Education in the Philippines

In this journal, I have discussed the relationship between education, poverty

alleviation, and economic development. The link is critical and the three are self-

reinforcing. Education creates greater opportunities for the youth, who go on to work

decent jobs in cities like Bacolod, Manila, and Cebu. The children remit money back to the

parents, who spend on home improvements and the tuition fees for the younger siblings.

College-educated individuals are much less likely to end up impoverished (about 1 in 44).

Trade schools also create opportunities, with only one in 10 people with post-secondary

degrees living below the poverty line. Unfortunately, the ratios drop precipitously after

that. One in three high school graduates and half of elementary school grads are

impoverished. Here are the sobering education statistics:

The long-term outlook for poverty reduction doesnt look good either, unfortunately. We all

know that there is a very strong link between education (or lack of education) and poverty

two-thirds of our poor families have household heads whose highest educational attainment

is at most Grade 6. Well, the education statistics (all from the NSCB ) tell a very sad tale:

elementary school net participation rates (NPR)the proportion of the number of enrollees

7-12 years old to population 7-12 years oldhave plummeted from 95 percent in school

year (SY) 1997-98 to 74 percent in 2005-2006, as have high school NPRs.

Cohort survival rates (CSR) have also dropped: Out of every 100 children who enter Grade

1, only 63 will reach Grade 6, down from 69 children in 1997-1998. In high school, CSR

have dropped even more: from 71 to 55. Which means, of course, that school dropout rates

have increased? Which is one of the reasons why, in 2005-2006, for the first time in 35

years, total enrollment decreased in both elementary and high school: although private

school enrollment increased, public school enrollment went down more?

The correlation is not difficult to see, but fixing the problem presents a challenge for several

reasons. According to some observers, the Department of Education Culture and Sports

(DECS) in the Philippines is one of the most corrupt government entities in the country. It

has a budget equal to 12% of spending, but is riddled with graft from procurement (buying

textbooks and other supplies), grease money, and bribes for just about any sort of

movement within the bureaucracy. The impact on the education system is detrimental:

Embezzlement, nepotism, influence peddling, fraud and other types of corruption also

flourish. Corruption has become so institutionalized that payoffs have become the lubricant

that makes the education bureaucracy run smoothly. The result: an entire generation of

Filipino students robbed of their right to a good education.

This corruption leads to poor allocation of resources. Teachers are underpaid and treated

poorly. In 2005, the Philippine government spent just $138 per student, compared to $852

in Thailand, another developing country in Southeast Asia. But graft and corruption are not

the only issues. Poverty is a vicious cycle that leads traps generations of families.

About 80% of the Filipino poor live in the rural areas of the country. These are towns

located deep in the mountains and the rice fields. The population density in the rural parts

of the country is low, and there is a corresponding deficiency in schools and classrooms.

Public school is free, but families still cannot afford to send their children for a complicated

network of reasons. In this editorial for the Pinoy Press, one author delineates the key

issue:

With around 65 million Filipinos or about 80 percent of the population trying to survive on

P96 ($2) or less per day, how can a family afford the school uniforms, the transportation to

and from school, the expenses for school supplies and projects, the miscellaneous

expenses, and the food for the studying sibling? More than this, with the worsening

unemployment problem and poverty situation, each member of the family is being expected

to contribute to the family income. Most, if not all, out-of-school children are on the streets

begging, selling cigarettes, candies, garlands, and assorted foodstuffs or things, or doing

odd jobs.

Beyond the selling goods on the street, children in farming families are expected to

work in the fields during harvest time. In agriculture-based communities where farming is

the primary livelihood, having children around to help with the work means more income for

the family. In a recent trip to Valladolid, someone told me that children are paid 15 pesos

for a days work in the blistering heat. They are pulled from school for two or three months

at a time and are irreparably disadvantaged compared with their classmates. So, they may

have to repeat the grade, only to be pulled out of school again next year.

Transportation is another big problem. Kids walk 2-3 kilometers or more to and from school

every day. They have to cross rivers and climb hills with their book bags. The ones that

can afford it take a tricycle, but that is a luxury. Schools are sometimes too far for the

most remote communities to practically access. So the families cant afford to pay and the

children are pulled from school.

It seems like an intractable problem. Corruption in the education bureaucracy and a

lack of resources make delivering a high-quality education to all Filipinos a challenge.

Microfinance is one way to help. With the assistance of microcredit loans, women can pay

for the education of their children to purchase uniforms, textbooks, lunches, and rides to

school. Also, by creating another source of income other than farming, the children do not

have to come help the family work the fields. When I talk to NWTF clients about their

dreams, they unfailingly say they hope for their children to finish their studies. History has

shown that it is an achievable goal. But real systemic change needs to come from above.

As long as corruption and bureaucracy paralyzes the system, the goal of delivering a decent

education to children which pays dividends to the country in the long run will remain out

of reach.

For the rural poor, non-profits exist to help in the mission of education. While looking up

pictures for this post, I came across a Filipino organization called the Gamot Cogon (Grass

Roots) Institute:

The Gamot Cogon Institute (a non-stock, non-profit organization) is an Iloilo-based cultural

institution working to transform society through human development approaches including

education and training. GCI also prototypes or demonstrates alternative approaches to

education, agriculture, health, and full human development.

Rural Health and Nutrition

In medicine, rural health or rural medicine is the interdisciplinary study

of health and health care delivery in rural environments. The concept of rural health incorporates

many fields, including geography, midwifery, nursing, sociology, economics,

and telehealth or telemedicine.

Research shows that the healthcare needs of individuals living in rural areas are different

from those in urban areas, and rural areas often suffer from a lack of access to healthcare. These

differences are the result of geographic, demographic, socioeconomic, workplace, and personal

health factors. For example, many rural communities have a large proportion of elderly people

and children. With relatively few people of working age (2050 years of age), these communities

have a high dependency. People living in rural areas also have poorer socioeconomic conditions,

less education, higher rates of tobacco and alcohol use, and higher mortality rates when

compared to their urban counterparts.

[1]

There are also high rates of poverty amongst rural

dwellers in many parts of the world, and poverty is one of the biggest social determinants of

health.

Many countries have made it a priority to increase funding for research on rural

health. These efforts have led to the development of several research institutes with rural health

mandates, including the Centre for Rural and Northern Health Research in Canada, Countryside

Agency in the United Kingdom, the Institute of Rural Health in Australia, and the New

Zealand Institute of Rural Health. These research efforts are designed to help identify the

healthcare needs of rural communities and provide policy solutions to ensure those needs are

met. The concept of incorporating the needs of rural communities into government services is

sometimes referred to as rural proofing.

For rural communities, health and nutrition are intricately linked with farming, food

production, income generation, culture and community life. So Groundswell supports local

organizations to improve community health and gain better access to health services.

Women generally are often the key link between family and childhood health and production, as

they are deeply involved in both. In the Andes, farmers know that Pachamama (mother earth)

and must be cared for to maintain soil fertility, and that soil health is directly connected to the

level and quality of food production. Good food and nutrition in turn contributes to healthy

families and communities, which are needed to continue the cycle of people living sustainably on

the land. So EkoRural supports local organizations to improve community and reproductive

health in marginalized indigenous communities. In Burkina Faso, women are a storehouse of

knowledge on biological diversity and how to keep their children fed during the hungry season,

relying on nuts, fruits, leaves and other products from surrounding trees and bushes as well as

small livestock they manage. Groundswell is supporting womens groups to increase vegetable

production for their families and improve their nutritional knowledge and practices.

In Haiti, Groundswells partner organization Partenariat pour le Dveloppement Local (PDL)

strengthens local peasant organizations to improve life in rural communities. In addition to

promoting sustainable farming, seed and grain banks, and savings and credit cooperatives, they

also help communities to organize health production committees. PDL health staff train local

health promoters from the committees, in themes such as reproductive health; prevention of HIV

and other sexually transmitted diseases; hygiene and sanitation to prevent disease; childhood

nutrition; and the production of natural medicines. The health promoters and committees then

survey local needs and develop and implement local action plans to address them. After the

earthquake in January 2010, Haiti was struck another devastating blow when a cholera epidemic

broke out in October of that year. Communities made urgent calls for support to respond to this

deadly outbreak, and Groundswell and PDL sprung into action. Staff coordinated with the

community health promoters to organize massive education campaigns for over 1,500 families

(9,000 people) to help people understand the cause and prevention of cholera. People passed on

what they learned to others. The peasant organizations quickly identified cholera cases in their

areas, and responded with antibiotics and oral rehydration fluids we provided. Chlorine was

distributed to disinfect water, and through education has become an ongoing practice for over

950 families. For longer term prevention, we have provided support and training to peasant

organizations to launch a campaign to build over 285 latrines and over 180 simple, household

water purification filters so far. As of September 2011, over 439,000 cases of cholera have

occurred in Haiti, with over 6,266 deaths. Even though it works with communities in the heart of

the area where cholera broke out, PDLs effective work has helped local peasant organizations

save hundreds of lives, preventing all but a few deaths.

Rural Change and Development

Rural development generally refers to the process of improving the quality of life and economic

well-being of people living in relatively isolated and sparsely populated areas. Rural

development has traditionally centered on the exploitation of land-intensive natural resources

such as agriculture and forestry. However, changes in global production networks and increased

urbanization have changed the character of rural areas. Increasingly tourism, niche

manufacturers, and recreation have replaced resource extraction and agriculture as dominant

economic drivers. The need for rural communities to approach development from a wider

perspective has created more focus on a broad range of development goals rather than merely

creating incentive for agricultural or resource based businesses. Education, entrepreneurship,

physical infrastructure, and social infrastructure all play an important role in developing rural

regions. Rural development is also characterized by its emphasis on locally produced economic

development strategies. In contrast to urban regions, which have many similarities, rural areas

are highly distinctive from one another. For this reason there are a large variety of rural

development approaches used globally.

Developmental action

Rural development actions are mainly and mostly to development aim for

the social and economic development of the rural areas. Rural development programs are usually

top-down from the local or regional authorities, regional development agencies, NGOs, national

governments or international development organizations. But then, local populations can also

bring about endogenous initiatives for development. The term is not limited to the issues

for developing countries. In fact many of the developed countries have very active rural

development programs. The main aim of the rural government policy is to develop the

undeveloped villages.

Rural development aims at finding the ways to improve the rural lives with participation of the

rural people themselves so as to meet the required need of the rural area. The outsider may not

understand the setting, culture, language and other things prevalent in the local area. As such,

general people themselves have to participate in their sustainable rural development.

In developing countries like Nepal, India, integrated development approaches are being followed

up. In the context of many approaches and ideas have been developed and followed up, for

instance, bottom-up approach, PRA- Participatory Rural Appraisal, RRA- Rapid Rural.

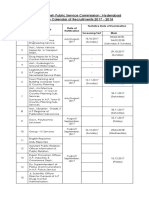

Naval State University

Naval, Biliran

College of Education

Written Report

In

SOCIETY AND CULTURE

(RURAL PROBLEMS)

Submitted by:

Vismanos, Joyce C.

Submitted to:

Henry Delapena

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Cheap TBE Inverter TeardownsДокумент33 страницыCheap TBE Inverter TeardownsWar Linux92% (12)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Harmonized Household Profiling ToolДокумент2 страницыHarmonized Household Profiling ToolJessa Mae89% (9)

- SSN Melaka SMK Seri Kota 2021 Annual Training Plan: Athletes Name Training ObjectivesДокумент2 страницыSSN Melaka SMK Seri Kota 2021 Annual Training Plan: Athletes Name Training Objectivessiapa kahОценок пока нет

- Earth As A PlanetДокумент60 страницEarth As A PlanetR AmravatiwalaОценок пока нет

- To 33B-1-1 01jan2013Документ856 страницTo 33B-1-1 01jan2013izmitlimonОценок пока нет

- Science 9-Quarter 2-Module-3Документ28 страницScience 9-Quarter 2-Module-3Mon DyОценок пока нет

- Sesion 2 - Copia-1Документ14 страницSesion 2 - Copia-1Maeva FigueroaОценок пока нет

- Recipe: Patisserie Method: Eclair Cake RecipeДокумент3 страницыRecipe: Patisserie Method: Eclair Cake RecipeEisha BibiОценок пока нет

- High School Students' Attributions About Success and Failure in Physics.Документ6 страницHigh School Students' Attributions About Success and Failure in Physics.Zeynep Tuğba KahyaoğluОценок пока нет

- Data Performance 2Документ148 страницData Performance 2Ibnu Abdillah MuhammadОценок пока нет

- Latihan Soal Bahasa Inggris 2Документ34 страницыLatihan Soal Bahasa Inggris 2Anita KusumastutiОценок пока нет

- This Unit Group Contains The Following Occupations Included On The 2012 Skilled Occupation List (SOL)Документ4 страницыThis Unit Group Contains The Following Occupations Included On The 2012 Skilled Occupation List (SOL)Abdul Rahim QhurramОценок пока нет

- Mapeh 9 Aho Q2W1Документ8 страницMapeh 9 Aho Q2W1Trisha Joy Paine TabucolОценок пока нет

- Lohmann GuideДокумент9 страницLohmann GuideRomulo Mayer FreitasОценок пока нет

- Stereochemistry Chiral Molecules QuizДокумент3 страницыStereochemistry Chiral Molecules QuizSean McDivittОценок пока нет

- 348 - Ct-Tol Toluene TdsДокумент1 страница348 - Ct-Tol Toluene Tdsonejako12Оценок пока нет

- AppendicitisДокумент7 страницAppendicitisTim LuoОценок пока нет

- Posi LokДокумент24 страницыPosi LokMarcel Baque100% (1)

- Faculty Based Bank Written PDFДокумент85 страницFaculty Based Bank Written PDFTamim HossainОценок пока нет

- APPSC Calender Year Final-2017Документ3 страницыAPPSC Calender Year Final-2017Krishna MurthyОценок пока нет

- Aliant Ommunications: VCL-2709, IEEE C37.94 To E1 ConverterДокумент2 страницыAliant Ommunications: VCL-2709, IEEE C37.94 To E1 ConverterConstantin UdreaОценок пока нет

- Qi Gong & Meditation - Shaolin Temple UKДокумент5 страницQi Gong & Meditation - Shaolin Temple UKBhuvnesh TenguriaОценок пока нет

- WT Chapter 5Документ34 страницыWT Chapter 5Wariyo GalgaloОценок пока нет

- Calculation Condensation StudentДокумент7 страницCalculation Condensation StudentHans PeterОценок пока нет

- Microbial Communities From Arid Environments On A Global Scale. A Systematic ReviewДокумент12 страницMicrobial Communities From Arid Environments On A Global Scale. A Systematic ReviewAnnaОценок пока нет

- Week 1 Seismic WavesДокумент30 страницWeek 1 Seismic WavesvriannaОценок пока нет

- Palf PDFДокумент16 страницPalf PDFKamal Nadh TammaОценок пока нет

- Buddahism ReportДокумент36 страницBuddahism Reportlaica andalОценок пока нет

- Tomography: Tomography Is Imaging by Sections or Sectioning Through The Use of AnyДокумент6 страницTomography: Tomography Is Imaging by Sections or Sectioning Through The Use of AnyJames FranklinОценок пока нет

- Citizen's 8651 Manual PDFДокумент16 страницCitizen's 8651 Manual PDFtfriebusОценок пока нет