Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Have Iphone - Will Travel: Beware, Tunnel Vision Ahead

Загружено:

rotorbrentОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Have Iphone - Will Travel: Beware, Tunnel Vision Ahead

Загружено:

rotorbrentАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

HAVE iPhone - WILL TRAVEL

By David Carr

Director of Safety

DECEMBER 2013

HAVE iPhoneWILL

TRAVEL

Steep & Slow; Wires

Below

Applying Aviation Safety

Concepts To Reduce

Patient Error

Safety Donts

2013 Incident Stats

Beware, Tunnel Vision Ahead

I was in a rush to get to the airport for another Med-Trans

adventure. I loaded up my stuff in the back, and being in a

frenzied state of mind, opted out of opening the car door for

my wife (Error #1 of many).

I slid behind the wheel, fired up the family truckster and

backed out of the garage. Full steam ahead. Destination:

the always-glamorous DFW airport. About 10 miles into our

journey, going from 0-70-back to crawl, walk and run speeds,

we had cleared most of the traffic and realizing that I had a

free moment to multi-task, reached for my cell phone to

check which terminal I would be flying out of.

My hand searched at first then grappled and grasped,

reaching for the cellphone that is ALWAYS where I put it, in

the center console cup holdernothing but air.

1*

Pilots, being right brained are prone to setting up systems.

Procedures we mentally and physically put in place to

ensure we dont miss anything. When you have 3 radios

going off, an LZ improperly setup, and two medical

professionals prepping for the worst case scenario patient

pickup , the mission can get distracting and complicated in a

really big hurry. Cue our fallback

systems. We reach for the

checklist to run through the do-or-

hurt yourself items; you instinctively

know where all the buttons areyou

have memorized your cockpit so

youd be ready for such things; you

mentally go through a task list to

make sure all the bases are

covered, then you follow well

practiced procedures of reconning

the LZ, cause you know that when it

comes to a safe outcome, first

responders are involved, but you are

committed. These are pieces of your

survival strategy. After all, you only

have:

My search was in vain. I looked down and my greatest

fear was realized. No phone, where a phone was

supposed to be! I dont I dont know about you, but just

but just about everything of value (with the exception of my

family) is in some fashion in that phone. Precious photos,

contact list of hundreds and important notes, not to mention

it was set up exactly how I wanted it (who wants to go

through setting up a phone more than once a decade?).

My mind shifted to troubleshooting. Did my wife have it in

her purse. No. Is it in my back pocket, No. Is it still plugged

in at home. Maybe, or did I put it on the back bumper as I

was loading my stuff?

Is That Steve Jobs Spinning In His Grave?

Stage II panic. As I looked for an opening in traffic to get

off the highway, Stage II panic escalated to stage III when I

dared to consider the possibly that I had made the

unpardonable sin. I found a spot with a wide shoulder, I

eased off the gas and brought the 6000 lb. SUV to a

standstill. Even in my panicked state of mind, I glanced

out the side view mirror for traffic before opening the

dooranother piece of my survival strategy. As I

proceeded to the back bumper, my minds eye was

conjuring images of little bits of Steve Jobs wonderphone

scattered about Hwy 121. As I made the turn, I looked

down and there it was, my prized iPhone 4 resting

comfortably on the back bumper, just where I left it.

Misery Loves Company

Shown below is empirical evidence that when it comes to

leaving stuff on my vehicle, Im in good company:

The same can be said in our flight operations. Med-Trans is

averaging one incident a month of something left on, out that

should be in, connected to that shouldnt be, or hanging out

of our aircraft.

An unsecure door opens in flight. Probably not the end of the

world, unless a bed sheet goes with it. You can ask our Air

Evac brethren about that one. How about stuff left on the

ramp that a patient might need in flight. The oops gets more

serious. What about stuff left on that falls off in flight? I

wouldnt want to be under our aircraft as a radio plummets

like a homesick brick from 500 feet above (1lb @ terminal

velocity = new Med-Trans patient + lawsuit).

Why does it continue to happen? We are all trained, we are

all professional, we all care. Here are my thoughts: Much

like my adventure to the airport, we get busy, in a rush, were

kicking up dust to get stuff loaded and on our way--hey, we

have lives to save people! Somewhere along the way

though, we miss the part about backing each other up. One

last check to make sure weand our stuff are together,

secure and ready to gallop off.

POLICY BETA TESTING UPDATE

If you recall from last months Safety Compass newsletter, we explained a new approach to developing and fielding new

policies or major changes to current policies. First, the proposed policy was published for a two week comment period, then

the changes were reviewed. Ten of 13 recommendations were made and the revised draft policy was beta tested by two

B407 and two EC135 bases for two weeks.

The next step in the policy evolution is to review the feedback from those bases, make final changes and publish the policy.

The feedback comments are posted on the Sharepoint Safety Page as is the proposed policy. It will be updated periodically

until it becomes a real live policy. https://sharepoint.med-trans.net/Safety/default.aspx

Thanks to all who took the time to provide comments, recommendations and feedback. Your opinions are appreciated.

DECEMBER 2013

STEEP & SLOW; WIRES BELOW

Bill Cady

BAM, GHS Med Trans (Greenville, SC)

I informed the crew that I was going to turn on the belly lights

during this approach. (Most crewmembers ask that we not turn

these on as they reflect off of the landing gear, hindering

visibility under NVG). The crew agreed with my decision to use

the supplemental lights and we began another slow, steep

approach toward the intersection from east to west, remaining

over the highway. At approximately 30 AGL, and clear of the

fire pumper, I heard the nurse say STOP, WIRES!

I immediately arrested our descent and looked below the

aircraft. There were two wires

approximately 10-15 below us,

running diagonally from 1

Oclock to 7 Oclock. I climbed

up 20 feet and moved forward,

away from the wires and asked

the LZ Commander if he saw

he saw the wires below us. He

responded Negative, Negative,

the only wires are in front of

you. We found out quickly that

this was not true. We landed

safely on the highway and shut

down, awaiting extrication of our

patient. With the patient

successfully delivered to the

trauma center, we began

debriefing this incident. It was

agreed that two things ultimately prevented us from striking

those wires:

The use of the belly lights which allowed the nurse to see

the wires unaided, and;

Our painfully slow descent and closure rates which

allowed us to stop immediately, with minimal power input.

The nurse stated, during the debrief, that if we had not been at

a crawl, he would not have seen the wires in time to stop us,

as he could only see about 20 feet, even with the aid of the

belly lights. It was also noted that the fire department tasked

with setting up the landing zone, was the same department

whose volunteer members were just involved in the tanker

truck rollover. Were their minds in the game?

The information provided to us in our landing zone briefings is

usually good, but should always be taken at face value. Many

hazards cannot be seen from the ground or are simply missed.

High and low recons should always be accomplished and

never taken lightly. Orbit the LZ as many times as necessary

to get a complete picture of the area you are about to descend

into. Be prepared, on EVERY approach, to stop on that

proverbial dime, and fly your EMS helicopter with this

philosophy; If your picture is not on my pilots license, youre

trying to kill me. This incident is but another example of how

flying with this mindset has saved me several times.

On a recent night, with little sleep and less than an hour

remaining in our busy night shift, GHS Med Trans responded

to an MVA involving a fire department tanker which had rolled

over, trapping at least one occupant. While enroute, we were

provided with coordinates and told that the local volunteer fire

department would be setting up a landing zone for us. We

made radio contact with the LZ Commander and learned that

the LZ was being set up in a highway intersection not far from

the scene. We arrived overhead and observed two pieces of

fire apparatus arriving at the intersection.

We orbited the area numerous

times while waiting for the LZ to

be secured. The LZ Commander

advised us that a police car was

parked underneath the only wires

in the LZ and that he wanted us

to land between those wires and

his rescue truck. I noted the

position of the police car, which

was parked on the Northwest

corner of the intersection and

asked if the wires were parallel

the highway. No, they are

perpendicular was his response.

I then told LZ Command that we

were unable to tell which of his

two trucks was the rescue truck

and asked him to identify it by cardinal direction. It was to the

west of the intersection.

We identified the wires crossing the highway, finished our

high recon and began a slow steep approach/low recon

toward the rescue truck. At 300 AGL we decided that the

landing area was not acceptable and I initiated a climb out

and go around. We told the LZ Commander of our decision

to reject the LZ and he radioed his personnel to move the

pumper farther down the road. The pumper was being used

to block the highway on the east side of the intersection. We

were then told that we could land behind the pumper. This

changed the touchdown area of the LZ to just east of the

intersection, well away from the previously reported wires.

We performed a few more orbits to complete a high recon of

the new LZ. We identified a power pole in a field, north of the

highway on which we would be landing. The pole was not an

impediment to our approach but we could not determine the

direction of any wires on the pole. We saw what appeared to

be a second pole near a residential structure directly east of

the first pole. We believed that any wires on the first pole

were possibly running to that house and if so, would not be in

our path during our approach and landing. I asked the LZ

Commander to watch our approach closely and to say stop,

if he saw any obstacles in our path. He acknowledged that

he would, stating the only wires are under the police car.

DECEMBER 2013

APPLYING AVIATION SAFETY CONCEPTS TO REDUCE

PATIENT SAFETY ERRORS Part I

DECEMBER 2013

By Connie Eastlee

VP, Program Operations

In the 2000 Institute of Medicines (IOM) report To Err is

Human, it was estimated that health care errors in the

United States contribute annually to between 48,000 and

96,000 in-patient deaths.

Why Hospitals Should Fly is an excellent

book that compares the similarities between

aviation and healthcare. The author made

the following analogy. Medical mistakes

likely occur to 22-30 patients every hour of

every day amounting to a staggering total

of 100,000-250,000 unnecessary patient

injuries every year-- the equivalent of crashing ten fully

loaded Boeing 747s every week.

Air Medical Transport is a high-risk environment for health

care error due to the presence of critical and complicated

patient physiology, the high volume of tasks, extensive

multitasking and predictable gaps in the continuity of care in

transporting the patient from one place to another. (scene to

hospital etc.).

When you compare aviation safety and patient safety

literature the terminology may be slightly different but the

concepts are the same. Error exists when a planned

sequence of activities, either mental or physical, does not

achieve the intended outcome. Either the plan did not

proceed as intended or the plan itself was inadequate. An

error is a mistake, inadvertent occurrence or unintended

event in an aviation or health care delivery [that] may or may

not result in injury.

From an article in a 2012 edition of Critical Care Nurse titled

Strategies for Improving Patient Safety: Linking Task Type

to Error Type. Three types of errors are described in detail.

1. Skill-Based Errors which include Slips and Lapses. Slips

and lapses occur during automatic or skill-based tasks:

A slip is an observable, external failure in the physical

execution of ones plan. Slips generally result from deficits

in attention or perception. The failure to focus ones

attention at a critical moment during an automatic (routine)

task creates an opportunity for error. Slips and lapses may

also occur from over attention during a routine task. When

attention is placed on the wrong thing, the result is skipping

or repeating steps in the task/checklist, or even in a reversal

of the task/checklist.

Sound familiar? How many times have you given a

medication or performed a walk-around, your attention

is diverted and the dosage is different than you

intended, or a clipboard was left on the helicopter skid?

2. Lapses are internal, less visible to an outside observer.

Lapses occur from failure of memory storage and manifest

in many different ways. Lapses commonly contribute to

errors of omission, which can have serious consequences.

An example of a lapse called reduced intentionality would

be when you start walking towards the room where the

refrigerated medications or Blood product is to pick up

before a flight and enroute something distracts you and you

cant remember what you were headed in that direction for

and continue on to get in the aircraft without the medications

or blood (and you thought this was just a result of old age).

3. Mistakes occur when the actions proceed as planned, but

the plan itself is inadequate to achieve its intended aim.

Essentially, the strategy used to solve the problem is flawed.

There are two distinct types of mistakes: rule based and

knowledge based.

Rule-Based Mistakes: Selecting the wrong path involves

the acknowledgment of a problem to be addressed and

a departure from skill-based, reflective performance.

Knowledge-Based Mistakes occur when we are

confronted with novel events where skill-based and rule-

based behavior are deemed inapplicable. These

situations require deliberate and conscious problem

solving. How often do we arrive at a Critical Access

Hospital which rarely sees a pediatric sepsis patient?

The hospital staff must rely on knowledge based

behavior as skills and rule based behavior will not help.

Ultimately, most tasks are governed by skill-based or rule-

based behavior, and thus most errors occur during these

processes. Hence the use of initial and recurrent

training for skills and checklists, policies and

procedures for rules (sounds like Aviation).

But if a task is not skill-based or rule-based and falls to

knowledge-based behavior, the rate of error relative to

opportunity increases significantly.

So how do we decrease our Human Errors? Safety

(whether patient or aviation) requires error and risk

management which refers to both error reduction (limit

the occurrence of the error/frequency of the risk) and

error containment (measures designed to enhance

detection and recovery of an error/probability of the

severity of the risk).

At Med-Trans we utilize the Risk Management Matrix for

identifying Hazards (prior to the error). We have been using

a risk assessment and its associated risk management

matrix for many years. In the near future though, expect to

(continued next page)

DECEMBER 2013

Sitting in the doctors office waiting room provided me with some time to kill. I looked around and saw everyone else glued

to their smartphone. So I took the road less traveled. I was sifting through ancient editions of various magazines when I

happened upon a dogeared issue of Glamour. Instantly, I recollected my favorite part, the section in the back titled

Fashion Dos and Donts. While perusing the various pictures I stumbled on a fun idea. Why not add a lighthearted

section entitled Safety Donts at the end of each newsletter. And so, an idea was born. If you would like to contribute,

send me your Darwin-Award worthy pics and I will include them in future editions.

Here are my top shots for December. Bask in the glory of our fellow human beings putting their critical decision making

skills on display.

see risk assessments for our aircraft maintenance and

clinical operations. Both are a necessary additions to our

Safety Management System because the risks we face

include risks faced in all of our day to day operations, not

just flying. Part Two - next month on how to Reduce

and Contain Errors.

LEARN FROM THE EXPERIENCE OF OTHERSIT HURTS LESS

If you have a safety concern, or if something in your operation doesnt seem right, you have tools available. First,

speak up! Get your supervisor involved. Submit a hazard report/Safety Concern. If you are uncomfortable with

either of those options, you can submit your concerning via our compliance hotline anonymously at:

800-399-2319.

The Med-Trans Safety Compass monthly newsletter

is one method we have of communicating with every

employee. We want this newsletter to be a forum for

fostering a culture of informing and learning.

I welcome your suggestions on topics you would like

to see addressed here. Better yet, send me your

article and I will get it added in the next issue.

Feel free to contact me by phone or email, my virtual

door is always open.

David Carr

Director of Safety

Director of Safety

David Carr

David.carr@med-trans.net

The Med-Trans Leadership Team

Chief Operating Officer

Rob Hamilton

Hamiltonrobert@med-trans.net

Director of Operations

Bert Levesque

levesquebert@med-trans.net

VP, Program Operations

Connie Eastlee

Eastleeconnie@med-trans.net

Director of Maintenance

Josh Brannon

Brannonjoshua@med-trans.net

Chief Pilot

Don Savage

Savagedonald@med-trans.net

Assistant Chief Pilot

Mike LaMee

Lameemichael@med-trans.net

VP, Flight Operations

Brian Foster

Fosterbrian@med-trans.net

DECEMBER 2013

Вам также может понравиться

- Measuring Our Safety-Ness: by David Carr Director of SafetyДокумент4 страницыMeasuring Our Safety-Ness: by David Carr Director of SafetyrotorbrentОценок пока нет

- TAC Attack October 1961Документ20 страницTAC Attack October 1961TateОценок пока нет

- ASRS CALLBACK Issue 506 - March 2022Документ2 страницыASRS CALLBACK Issue 506 - March 2022François Hubert SergiОценок пока нет

- February - Stevedore Injured by TwistlockДокумент2 страницыFebruary - Stevedore Injured by TwistlockHarman SandhuОценок пока нет

- Positive Vision: Enjoying the Adventures and Advantages of Poor EyesightОт EverandPositive Vision: Enjoying the Adventures and Advantages of Poor EyesightОценок пока нет

- Aviation EnglishДокумент86 страницAviation Englishtmhoangvna100% (1)

- The Decision Was Easy: The Ground Truth About Safety LeadershipОт EverandThe Decision Was Easy: The Ground Truth About Safety LeadershipОценок пока нет

- Contingency PlanДокумент2 страницыContingency Planapi-630394298Оценок пока нет

- Near Miss Toolbox TalkДокумент2 страницыNear Miss Toolbox Talkpruncu.alianmОценок пока нет

- Callback - NASA - 492Документ2 страницыCallback - NASA - 492Αλέξανδρος ΒασιλειάδηςОценок пока нет

- Urban Survival Guide Top Urban Survival Skills (Field & Stream) (2012) PDFДокумент11 страницUrban Survival Guide Top Urban Survival Skills (Field & Stream) (2012) PDF20180321Оценок пока нет

- Haunter Grey Deception, Seven Book Boxed Set: Includes Upheaval, Evolution, and the PrequelsОт EverandHaunter Grey Deception, Seven Book Boxed Set: Includes Upheaval, Evolution, and the PrequelsОценок пока нет

- Hazard HeroДокумент31 страницаHazard HeroKennet PhanОценок пока нет

- 005 - Vocabulary - Taking OffДокумент3 страницы005 - Vocabulary - Taking OffFábia RodriguesОценок пока нет

- Safety Awareness: Celebrating Operational ExcellenceДокумент8 страницSafety Awareness: Celebrating Operational ExcellenceMario AndrewОценок пока нет

- The Secret Nuclear Threat: Trident Whistleblower William McneillyДокумент17 страницThe Secret Nuclear Threat: Trident Whistleblower William McneillyLeakSourceInfoОценок пока нет

- English Writers Effect InsДокумент4 страницыEnglish Writers Effect InsChunky PresidentОценок пока нет

- HalflifeДокумент13 страницHalflifeRooWWОценок пока нет

- "To Err Is Human ": AccountabilityДокумент4 страницы"To Err Is Human ": AccountabilityrotorbrentОценок пока нет

- (Sample Essay) (Hope)Документ2 страницы(Sample Essay) (Hope)muhdsabri51Оценок пока нет

- Critical Thinking in Company 3.0 Lesson 2015Документ3 страницыCritical Thinking in Company 3.0 Lesson 2015Jimmy HaddadОценок пока нет

- Material para Estudos Da AVI Azul Linhas AéreasДокумент32 страницыMaterial para Estudos Da AVI Azul Linhas AéreasThaís BaraúnaОценок пока нет

- Student Guide 9: Activity 1 1.1 Explain The Meaning of The Following WordsДокумент9 страницStudent Guide 9: Activity 1 1.1 Explain The Meaning of The Following WordsLORAINE CAUSADO BARONОценок пока нет

- Blind Suctioning For BeginnersДокумент7 страницBlind Suctioning For BeginnersMark HammerschmidtОценок пока нет

- Risk Management in ParaglidingДокумент2 страницыRisk Management in Paraglidinglinh nguyenОценок пока нет

- Crime Scene InvestigationДокумент94 страницыCrime Scene InvestigationTina SwainОценок пока нет

- The Practice or Art of Using Language With Fluency and AptnessДокумент1 страницаThe Practice or Art of Using Language With Fluency and AptnessCorey HomОценок пока нет

- David Fravor Statement For House Oversight CommitteeДокумент3 страницыDavid Fravor Statement For House Oversight CommitteeStephanie Dube DwilsonОценок пока нет

- English (101-103)Документ5 страницEnglish (101-103)Umiyanti AzizahОценок пока нет

- Filename(s) Quote Play: Absolutely. Menu 0:00Документ17 страницFilename(s) Quote Play: Absolutely. Menu 0:00uwaifotonyОценок пока нет

- Ladies and Gentlemen IДокумент1 страницаLadies and Gentlemen IPanergo ErickajoyОценок пока нет

- Risk Assesment HGДокумент3 страницыRisk Assesment HGapi-632030001Оценок пока нет

- Oldier Onors Rogram and Ospital With Riceless Ift: S H P H P GДокумент8 страницOldier Onors Rogram and Ospital With Riceless Ift: S H P H P GrotorbrentОценок пока нет

- The Worst-Case Scenario Survival Handbook: TravelОт EverandThe Worst-Case Scenario Survival Handbook: TravelРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (346)

- Safety Compass March 2014Документ5 страницSafety Compass March 2014rotorbrentОценок пока нет

- KLBB Rnav (GPS) 35lДокумент1 страницаKLBB Rnav (GPS) 35lrotorbrentОценок пока нет

- "How To Murphy-Proof Your Life": If Anything Can Go Wrong, It WillДокумент4 страницы"How To Murphy-Proof Your Life": If Anything Can Go Wrong, It WillrotorbrentОценок пока нет

- "How To Murphy-Proof Your Life": If Anything Can Go Wrong, It WillДокумент4 страницы"How To Murphy-Proof Your Life": If Anything Can Go Wrong, It WillrotorbrentОценок пока нет

- "To Err Is Human ": AccountabilityДокумент4 страницы"To Err Is Human ": AccountabilityrotorbrentОценок пока нет

- G500 Cockpit Reference GuideДокумент84 страницыG500 Cockpit Reference Guiderotorbrent100% (1)

- Tradition Meet Practical DriftДокумент6 страницTradition Meet Practical DriftrotorbrentОценок пока нет

- "Sugar N Spice ": - One of These Is Not Like The Other (Part I)Документ5 страниц"Sugar N Spice ": - One of These Is Not Like The Other (Part I)rotorbrentОценок пока нет

- Trimble 2101 ManualДокумент243 страницыTrimble 2101 ManualrotorbrentОценок пока нет

- The Dutch Oven CookbookДокумент53 страницыThe Dutch Oven CookbookCrisОценок пока нет

- School Rules and Policy Manual: ArcproДокумент13 страницSchool Rules and Policy Manual: ArcprorotorbrentОценок пока нет

- Book of EnochДокумент77 страницBook of EnochrotorbrentОценок пока нет

- Electric Motor Test RepairДокумент160 страницElectric Motor Test Repairrotorbrent100% (2)

- How To Make Professional Lock Pick ToolsДокумент5 страницHow To Make Professional Lock Pick Toolsvinekm6100% (6)

- Locksport International GuideДокумент22 страницыLocksport International Guidewhistjenn100% (2)

- Electric Motor Test RepairДокумент160 страницElectric Motor Test Repairrotorbrent100% (2)

- Coil Winding MachineДокумент4 страницыCoil Winding MachineJim90% (10)

- Skull Osteology & Cranial Cavity - TUSKДокумент66 страницSkull Osteology & Cranial Cavity - TUSKterima kasihОценок пока нет

- Installation Instructions: Lock-Down ScrewДокумент1 страницаInstallation Instructions: Lock-Down ScrewDhimas ZakariaОценок пока нет

- Tool Operating Manual Tool Operating Manual: 276-7273 Cylinder Sensor Test Box (In Cylinder Function Test)Документ12 страницTool Operating Manual Tool Operating Manual: 276-7273 Cylinder Sensor Test Box (In Cylinder Function Test)CarlosОценок пока нет

- Bed Bath MikeДокумент24 страницыBed Bath MikeMike100% (1)

- Surgical Site Infection (SSI) Event: Monthly Reporting PlanДокумент31 страницаSurgical Site Infection (SSI) Event: Monthly Reporting PlanDRMC InfectioncontrolserviceОценок пока нет

- 2090 2697 2 108 PDFДокумент5 страниц2090 2697 2 108 PDFMuhammad Riza FahlawiОценок пока нет

- Pelvis and Perineum (Appleton & Lange Review)Документ41 страницаPelvis and Perineum (Appleton & Lange Review)orea100% (2)

- Helix Alliance - Resume (Dr. Appukutty Manickam (Kumar) ) - 1Документ6 страницHelix Alliance - Resume (Dr. Appukutty Manickam (Kumar) ) - 1indo 5SОценок пока нет

- PE Theory Knowledge OrganiserДокумент5 страницPE Theory Knowledge OrganiserSharra LopezОценок пока нет

- Spinal Injury Nursing Care PlanДокумент2 страницыSpinal Injury Nursing Care PlanPatricia OrtegaОценок пока нет

- Fetal Macrosomia ArtДокумент14 страницFetal Macrosomia Artanyka2Оценок пока нет

- Chinese Herbal FormulasДокумент8 страницChinese Herbal Formulasryandakota100% (1)

- AORN Electrosurgery GuidelinesДокумент20 страницAORN Electrosurgery GuidelinesRudy DuterteОценок пока нет

- JZ990D43501 eДокумент6 страницJZ990D43501 eМаксим ПасичникОценок пока нет

- Scorebuilders 3Документ40 страницScorebuilders 3DeepRamanОценок пока нет

- D 100394 X 012Документ52 страницыD 100394 X 012Preyas SuvarnaОценок пока нет

- Jackson V AEG Live Transcripts of DR Scott David Saunders (Doctor)Документ69 страницJackson V AEG Live Transcripts of DR Scott David Saunders (Doctor)TeamMichaelОценок пока нет

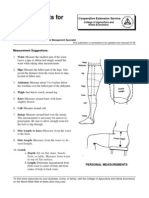

- Measurements For Fitting Pants: Guide C-209Документ2 страницыMeasurements For Fitting Pants: Guide C-209Ranil Hashan FОценок пока нет

- Vertebral Column Skull Projection MethodДокумент8 страницVertebral Column Skull Projection MethodLaFranz CabotajeОценок пока нет

- Shipboard High VoltageДокумент62 страницыShipboard High VoltageArun SОценок пока нет

- Radiographic Positioning and Radiologic Procedures I FinalsДокумент13 страницRadiographic Positioning and Radiologic Procedures I FinalsrozdhagaОценок пока нет

- Dorin The Dwarf SpellsДокумент3 страницыDorin The Dwarf Spellspotato123123aОценок пока нет

- Respiration PHYSIOДокумент23 страницыRespiration PHYSIOTauseef AfridiОценок пока нет

- Impaired Physical MobilityДокумент1 страницаImpaired Physical Mobilitykyaw100% (1)

- ARDSДокумент81 страницаARDSShanaz NovriandinaОценок пока нет

- Lucas vs. TuanoДокумент2 страницыLucas vs. Tuanomelinda elnarОценок пока нет

- A Fighter's Lines by Marzuki AliДокумент5 страницA Fighter's Lines by Marzuki AliAnonymous TADs3BevnОценок пока нет

- Accessory Navicular BoneДокумент29 страницAccessory Navicular BonePhysiotherapist AliОценок пока нет

- Article Review Kel 3 KompilasiДокумент21 страницаArticle Review Kel 3 KompilasiFazlin KhuzaimaОценок пока нет

- Safe Working ProcedureДокумент23 страницыSafe Working ProcedureBea MokОценок пока нет