Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Atonality: Atonality in Its Broadest Sense Is Music That Lacks A Tonal Center, or

Загружено:

Paulo Cesar Maia de Aguiar(Composer)0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

159 просмотров8 страницAtonality in its broadest sense is music that lacks a tonal center, or key. Atonality describes music that does not conform to the system of tonal hierarchies. The term is sometimes used to describe music that is neither tonal nor serial.

Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Atonality

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документAtonality in its broadest sense is music that lacks a tonal center, or key. Atonality describes music that does not conform to the system of tonal hierarchies. The term is sometimes used to describe music that is neither tonal nor serial.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

159 просмотров8 страницAtonality: Atonality in Its Broadest Sense Is Music That Lacks A Tonal Center, or

Загружено:

Paulo Cesar Maia de Aguiar(Composer)Atonality in its broadest sense is music that lacks a tonal center, or key. Atonality describes music that does not conform to the system of tonal hierarchies. The term is sometimes used to describe music that is neither tonal nor serial.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 8

The ending of Schoenberg's "George

Lieder" Op. 15/1 presents what would

be "extraordinary" chord in tonal

music, without the harmonic-

contrapuntal constraints of tonal

music (Forte 1977, 1). Play

Atonality

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Atonality in its broadest sense is music that lacks a tonal center, or

key. Atonality, in this sense, usually describes compositions written

from about 1908 to the present day where a hierarchy of pitches

focusing on a single, central tone is not used, and the notes of the

chromatic scale function independently of one another (Kennedy

1994). More narrowly, the term atonality describes music that does

not conform to the system of tonal hierarchies that characterized

classical European music between the seventeenth and nineteenth

centuries (Lansky, Perle, and Headlam 2001). "The repertory of

atonal music is characterized by the occurrence of pitches in novel

combinations, as well as by the occurrence of familiar pitch

combinations in unfamiliar environments" (Forte 1977, 1).

More narrowly still, the term is sometimes used to describe music that

is neither tonal nor serial, especially the pre-twelve-tone music of the Second Viennese School, principally

Alban Berg, Arnold Schoenberg, and Anton Webern (Lansky, Perle, and Headlam 2001). However, "[a]s a

categorical label, 'atonal' generally means only that the piece is in the Western tradition and is not 'tonal' " (Rahn

1980, 1), although there are longer periods, e.g., medieval, renaissance, and modern modal musics to which this

definition does not apply. "[S]erialism arose partly as a means of organizing more coherently the relations used in

the preserial 'free atonal' music. ... Thus many useful and crucial insights about even strictly serial music depend

only on such basic atonal theory" (Rahn 1980, 2).

Late 19th- and early 20th-century composers such as Alexander Scriabin, Claude Debussy, Bla Bartk, Paul

Hindemith, Sergei Prokofiev, Igor Stravinsky, and Edgard Varse have written music that has been described,

in full or in part, as atonal (Baker 1980, 1986; Bertram 2000; Griffiths 2001; Kohlhase 1983; Lansky and Perle

2001; Obert 2004; Orvis 1974; Parks 1985; Rlke 2000; Teboul 199596; Zimmerman 2002).

Contents

1 History

1.1 Free atonality

2 Controversy over the term itself

3 Composing atonal music

4 Criticism of the concept of atonality

5 Criticism of atonal music

6 See also

7 Sources

8 Further reading

9 External links

History

While music without a tonal center had been written previously, for example Franz Liszt's Bagatelle sans

tonalit of 1885, it is with the twentieth century that the term atonality began to be applied to pieces,

particularly those written by Arnold Schoenberg and The Second Viennese School.

Their music arose from what was described as the "crisis of tonality" between the late nineteenth century and

early twentieth century in classical music. This situation had come about historically through the increasing use

over the course of the nineteenth century of

ambiguous chords, less probable harmonic inflections, and the more unusual melodic and rhythmic

inflections possible within the style[s] of tonal music. The distinction between the exceptional and

the normal became more and more blurred; and, as a result, there was a concomitant loosening of

the syntactical bonds through which tones and harmonies had been related to one another. The

connections between harmonies were uncertain even on the lowestchord-to-chordlevel. On

higher levels, long-range harmonic relationships and implications became so tenuous that they

hardly functioned at all. At best, the felt probabilities of the style system had become obscure; at

worst, they were approaching a uniformity which provided few guides for either composition or

listening. (Meyer 1967, 241)

The first phase, known as "free atonality" or "free chromaticism", involved a conscious attempt to avoid

traditional diatonic harmony. Works of this period include the opera Wozzeck (19171922) by Alban Berg and

Pierrot Lunaire (1912) by Schoenberg.

The second phase, begun after World War I, was exemplified by attempts to create a systematic means of

composing without tonality, most famously the method of composing with 12 tones or the twelve-tone

technique. This period included Berg's Lulu and Lyric Suite, Schoenberg's Piano Concerto, his oratorio Die

Jakobsleiter and numerous smaller pieces, as well as his last two string quartets. Schoenberg was the major

innovator of the system, but his student, Anton Webern, is anecdotally claimed to have begun linking dynamics

and tone color to the primary row, making rows not only of pitches but of other aspects of music as well (Du

Noyer 2003, 272). However, actual analysis of Webern's twelve-tone works has so far failed to demonstrate

the truth of this assertion. One analyst concluded, following a minute examination of the Piano Variations, op.

27, that

while the texture of this music may superficially resemble that of some serial music ... its structure

does not. None of the patterns within separate nonpitch characteristics makes audible (or even

numerical) sense in itself. The point is that these characteristics are still playing their traditional role

of differentiation. (Westergaard 1963, 109)

Twelve-tone technique, combined with the parametrization (separate organization of four aspects of music:

pitch, attack character, intensity, and duration) of Olivier Messiaen, would be taken as the inspiration for

serialism (du Noyer 2003, 272).

Atonality emerged as a pejorative term to condemn music in which chords were organized seemingly with no

apparent coherence. In Nazi Germany, atonal music was attacked as "Bolshevik" and labeled as degenerate

(Entartete Musik) along with other music produced by enemies of the Nazi regime. Many composers had their

works banned by the regime, not to be played until after its collapse after World War II.

The Second Viennese School, and particularly 12-tone composition, was taken by avant-garde composers in

the 1950s to be the foundation of the New Music, and led to serialism and other forms of musical innovation.

Prominent post-World War II composers in this tradition are Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luciano

Berio, Krzysztof Penderecki, and Milton Babbitt. Many composers wrote atonal music after the war, including

Elliott Carter, Gyrgy Ligeti, and Witold Lutosawski. After Schoenberg's death, Igor Stravinsky began to write

music with a mixture of serial and tonal elements (du Noyer 2003, 271). Iannis Xenakis generated pitch sets

from mathematical formulae, and also saw the expansion of tonal possibilities as part of a synthesis between the

hierarchical principle and the theory of numbers, principles which have dominated music since at least the time of

Parmenides (Xenakis 1971, 204).

Free atonality

The twelve-tone technique was preceded by Schoenberg's freely atonal pieces of 19081923, which, though

free, often have as an "integrative element...a minute intervallic cell" that in addition to expansion may be

transformed as with a tone row, and in which individual notes may "function as pivotal elements, to permit

overlapping statements of a basic cell or the linking of two or more basic cells" (Perle 1977, 2).

The twelve-tone technique was also preceded by nondodecaphonic serial composition used independently in

the works of Alexander Scriabin, Igor Stravinsky, Bla Bartk, Carl Ruggles, and others (Perle 1977, 37).

"Essentially, Schoenberg and Hauer systematized and defined for their own dodecaphonic purposes a pervasive

technical feature of 'modern' musical practice, the ostinato" (Perle 1977, 37)

Controversy over the term itself

The term "atonality" itself has been controversial. Arnold Schoenberg, whose music is generally used to define

the term, was vehemently opposed to it, arguing that "The word 'atonal' could only signify something entirely

inconsistent with the nature of tone... to call any relation of tones atonal is just as farfetched as it would be to

designate a relation of colors aspectral or acomplementary. There is no such antithesis" (Schoenberg 1978,

432).

"Atonal" developed a certain vagueness in meaning as a result of its use to describe a wide variety of

compositional approaches that deviated from traditional chords and chord progressions. Attempts to solve these

problems by using terms such as "pan-tonal", "non-tonal", "multi-tonal", "free-tonal" and "without tonal center"

instead of "atonal" have not gained broad acceptance.

Composing atonal music

Setting out to compose atonal music may seem complicated because of both the vagueness and generality of the

term. Additionally George Perle explains that, "the 'free' atonality that preceded dodecaphony precludes by

definition the possibility of self-consistent, generally applicable compositional procedures" (Perle 1962, 9).

However, he provides one example as a way to compose atonal pieces, a pre-twelve-tone technique piece by

Anton Webern, which rigorously avoids anything that suggests tonality, to choose pitches that do not imply

tonality. In other words, reverse the rules of the common practice period so that what was not allowed is

required and what was required is not allowed. This is what was done by Charles Seeger in his explanation of

dissonant counterpoint, which is a way to write atonal counterpoint (Seeger 1930).

Further, Perle agrees with Oster (1960) and Katz (1945) that, "the abandonment of the concept of a root-

generator of the individual chord is a radical development that renders futile any attempt at a systematic

formulation of chord structure and progression in atonal music along the lines of traditional harmonic theory"

(Perle 1962, 31). Atonal compositional techniques and results "are not reducible to a set of foundational

assumptions in terms of which the compositions that are collectively designated by the expression 'atonal music'

can be said to represent 'a system' of composition" (Perle 1962, 1). Equal-interval chords are often of

indeterminate root, mixed-interval chords are often best characterized by their interval content, while both lend

themselves to atonal contexts (DeLone and Wittlich 1975, 36272).

Perle also points out that structural coherence is most often achieved through operations on intervallic cells. A

cell "may operate as a kind of microcosmic set of fixed intervallic content, statable either as a chord or as a

melodic figure or as a combination of both. Its components may be fixed with regard to order, in which event it

may be employed, like the twelve-tone set, in its literal transformations. Individual tones may function as

pivotal elements, to permit overlapping statements of a basic cell or the linking of two or more basic cells" (Perle

1962, 910).

Regarding the post-tonal music of Perle, one theorist wrote: "While ... montages of discrete-seeming elements

tend to accumulate global rhythms other than those of tonal progressions and their rhythms, there is a similarity

between the two sorts of accumulates spatial and temporal relationships: a similarity consisting of generalized

arching tone-centers linked together by shared background referential materials" (Swift 198283, 272).

Another approach of composition techniques for atonal music is given by Allen Forte who developed the theory

behind atonal music (Forte 1977). Whereas in tonal music, chords belonged to the same scale, in atonal music

different operations on the chords are defined. Because of the lack of tonality, all twelve notes of the scale are

considered including sharps as well. It is useful to represent these notes on a circle where each note is

associated with a number (0 is A, 1 is A, 2 is B, 3 is C, and so on). No distinction is made between the scales

at different octaves meaning that an A is always noted 0 whatever octave it belongs to. Starting from a random

chord or pitch class, Forte describes two main operations: transposition an inversion. These can be easily

visualized on the circle above. Transposition can be seen as a rotation of t either clockwise or anti-clockwise,

where each note of the chord is rotated equally. For example if t = 2 and the chord is [0 3 6], transposition

(clockwise) will be [2 5 8]. Inversion can be seen as a symmetry with respect to the axis formed by 0 and 6. If

we carry on with our example [0 3 6] becomes [0 9 6].

In this case, the chord is determined by three factors which are the choice of the notes also called pitch class,

the cardinal number which is the number of notes in the chord, and the interval content of the chord. To

determine if two chords are equivalent, the prime form is defined. This prime form is just a standard way of

writing down the chord, in a normal order. First, the pitch class indexes increase from left to right. Secondly, the

circular permutation (permutation obtained by placing the last element in the first position of the pitch class)

chosen is that with the smallest difference between the first and last note of the chord. If that is not enough to

differentiate the chords, the chord with the least difference between the two first notes is chosen as the prime

form. Two chords are equivalent if they can be reduced to the same prime form by transposition or inversion

followed by transposition. There are some chords which are not equivalent but have an identical interval content,

these are known as z-related pairs.

An important characteristic are the invariants which are the notes which stay identical after a transformation. It

should be noted that no difference is made between the octave in which the note is played so that, for example,

all Cs are equivalent, no matter the octave in which they actually occur. This is why the 12-note scale is

represented by a circle. This leads us to the definition of the similarity between two chords which considers the

subsets and the interval content of each chord (Forte 1977).

These equivalent chords,invariants, z-related pairs, identical subsets, all give a continuity to the musical piece

and compensate for the lack of tonality by defining new equivalence relations between chords.

Criticism of the concept of atonality

Composer Anton Webern held that "new laws asserted themselves that made it impossible to designate a piece

as being in one key or another" (Webern 1963, 51). Composer Walter Piston, on the other hand, said that, out

of long habit, whenever performers "play any little phrase they will hear it in some keyit may not be the right

one, but the point is they will play it with a tonal sense. ... [T]he more I feel I know Schoenberg's music the

more I believe he thought that way himself. ... And it isn't only the players; it's also the listeners. They will hear

tonality in everything" (Westergaard 1968, 15).

Donald Jay Grout similarly doubted whether atonality is really possible, because "any combination of sounds can

be referred to a fundamental root". He defined it as a fundamentally subjective category: "atonal music is music

in which the person who is using the word cannot hear tonal centers" (Grout 1960, 647).

One difficulty is that even an otherwise "atonal" work, tonality "by assertion" is normally heard on the thematic or

linear level. That is, centricity may be established through the repetition of a central pitch or from emphasis by

means of instrumentation, register, rhythmic elongation, or metric accent (Simms 1986, 65). It is noted however

that centricity in tonal music is established through hierarchical relationships of chords functions and scale

degrees, and is not directly related to instrumentation, or temporal aspects.

Criticism of atonal music

Swiss conductor, composer, and musical philosopher Ernest Ansermet, a critic of atonal music, wrote

extensively on this in the book Les fondements de la musique dans la conscience humaine (French for: The

foundations of music in human consciousness) (Ansermet 1961), where he argued that the classical musical

language was a precondition for musical expression with its clear, harmonious structures. Ansermet argued that

a tone system can only lead to a uniform perception of music if it is deduced from just a single interval. For

Ansermet this interval is the fifth (Mosch 2004, 96). Modern atonal music, incomprehensible to Ansermet,

chooses interval relations by means that seemed random to him, so he claimed it could not achieve such an

impact, ethos, or catharsis for an audience. Musics of other historical periods and cultures do not have these

language constraints or difficulties.

See also

Emancipation of the dissonance

Klangfarbenmelodie

Noise (music)

Jazz improvisation

List of atonal compositions

Sources

Ansermet, Ernest. 1961. Les fondements de la musique dans la conscience humaine. 2 v. Neuchtel:

La Baconnire.

Baker, James M. 1980. "Scriabin's Implicit Tonality". "Music Theory Spectrum" 2:118.

Baker, James M. 1986. The Music of Alexander Scriabin. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Bertram, Daniel Cole. 2000. "Prokofiev as a Modernist, 19071915". PhD diss. New Haven: Yale

University.

DeLone, Peter, and Gary Wittlich (eds.). 1975. Aspects of Twentieth-Century Music. Englewood

Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-049346-5.

Du Noyer, Paul (ed.). 2003. "Contemporary", in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Music: From Rock,

Jazz, Blues and Hip Hop to Classical, Folk, World and More, pp. 271272. London: Flame Tree

Publishing. ISBN 1-904041-70-1

Forte, Allen. 1977. The Structure of Atonal Music. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

ISBN 978-0-300-02120-2.

Griffiths, Paul. 2001. "Varse, Edgard [Edgar] (Victor Achille Charles)". The New Grove Dictionary of

Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan

Publishers.

Grout, Donald Jay. 1960. A History of Western Music. New York: W. W. Norton.

Katz, Adele T. 1945. Challenge to Musical Traditions: A New Concept of Tonality. New York:

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Reprint edition, New York: Da Capo, 1972.

Michael Kennedy. 1994. "Atonal." The Oxford Dictionary of Music. Oxford & New York: Oxford

University Press. ISBN 0-19-869162-9

Kohlhase, Hans. 1983. "Aussermusikalische Tendenzen im Frhschaffen Paul Hindemiths. Versuch uber

die Kammermusik Nr. 1 mit Finale 1921". Hamburger Jahrbuch fr Musikwissenschaft 6:183223.

Lansky, Paul, and George Perle. 2001. "Atonality 2: Differences between Tonality and Atonality". The

New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John

Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

Lansky, Paul, George Perle, and Dave Headlam. 2001. "Atonality". The New Grove Dictionary of

Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan

Publishers.

Meyer, Leonard B. 1967. Music, the Arts, and Ideas: Patterns and Predictions in Twentieth-

Century Culture. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. (Second edition 1994.)

Mosch, Ulrich. 2004. Musikalisches Hren serieller Musik: Untersuchungen am Beispiel von Pierre

Boulez' Le Marteau sans matre. Saarbrcken: Pfau-Verag.

Obert, Simon. 2004. "Zum Begriff Atonalitt: Ein Vergleich von Anton Weberns 'Sechs Bagatellen fr

Streichquartett' op. 9 und Igor Stravinskijs 'Trois pices pour quatuor cordes' ". In Das

Streichquartett in der ersten Hlfte des 20. Jahrhunderts: Bericht ber das Dritte Internationale

Symposium Othmar Schoeck in Zrich, 19. und 20. Oktober 2001. Schriftenreihe der Othmar

Schoeck-Gesellschaft 4, edited by Beat A. Fllmi and Michael Baumgartner. Tutzing: Schneider.

Orvis, Joan. 1974. "Technical and stylistic features of the piano etudes of Stravinsky, Bartk, and

Prokofiev". DMus Piano pedagogy: Indiana University.

Oster, Ernst. 1960. "Re: A New Concept of Tonality (?)", Journal of Music Theory 4:96.

Parks, Richard S. 1985. "Tonal Analogues as Atonal Resources and Their Relation to form in Debussy's

Chromatic Etude". Journal of Music Theory 29, no. 1 (Spring): 3360.

Perle, George. 1962. Serial Composition and Atonality: An Introduction to the Music of

Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07430-0.

Perle, George. 1977. Serial Composition and Atonality: An Introduction to the Music of

Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern. Fourth Edition. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of

California Press. ISBN 0-520-03395-7.

Rahn, John. 1980. Basic Atonal Theory. New York: Longman, Inc. ISBN 0-582-28117-2.

Stegemann, Benedikt: Theory of Tonality. Theoretical Studies, Wilhelmshaven, Noetzel 2013, ISBN

978-3-7959-0963-5

Rlke, Volker. 2000. "Bartks Wende zur Atonalitt: Die "tudes" op. 18". Archiv fr

Musikwissenschaft 57, no. 3:24063.

Schoenberg, Arnold. 1978. Theory of Harmony, translated by Roy Carter. Berkeley & Los Angeles:

University of California Press.

Seeger, Charles. 1930. "On Dissonant Counterpoint." Modern Music 7, no. 4:2531.

Simms, Bryan R. 1986. Music of the Twentieth Century: Style and Structure. New York: Schirmer

Books. ISBN 0-02-872580-8.

Swift, Richard. 198283. "A Tonal Analog: The Tone-Centered Music of George Perle

(http://www.jstor.org/stable/832876)". Perspectives of New Music 21, nos. 1/2 (Fall-Winter/Spring-

Summer): 25784. (Subscription Access.)

Teboul, Jean-Claude. 199596. "Comment analyser le neuvime interlude en si du "Ludus tonalis" de

Paul Hindemith? (Hindemith ou Schenker?) ". Ostinato Rigore: Revue Internationale d'tudes

Musicales, nos. 67:21532.

Webern, Anton. 1963. The Path to the New Music, translated by Leo Black. Bryn Mawr.

Pennsylvania: Theodore Presser; London: Universal Edition.

Westergaard, Peter. 1963. "Webern and 'Total Organization': An Analysis of the Second Movement of

Piano Variations, Op. 27." Perspectives of New Music 1, no. 2 (Spring): 10720.

Westergaard, Peter. 1968. "Conversation with Walter Piston". Perspectives of New Music 7, no.1

(Fall-Winter) 317.

Xenakis, Iannis. 1971. Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition. Bloomington

and London: Indiana University Press. Revised edition, 1992. Harmonologia Series No. 6. Stuyvesant,

NY: Pendragon Press. ISBN 0-945193-24-6

Zimmerman, Daniel J. 2002. "Families without Clusters in the Early Works of Sergei Prokofiev". PhD

diss. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Further reading

Beach, David (ed.). 1983. "Schenkerian Analysis and Post-Tonal Music", Aspects of Schenkerian

Theory. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dahlhaus, Carl. 1966. "Ansermets Polemik gegen Schnberg." Neue Zeitschrift fr Musik 127, no.

5:17983.

Forte, Allen. 1963. "Context and Continuity in an Atonal Work: A Set-Theoretic Approach".

Perspectives of New Music 1, no. 2 (Spring): 7282.

Forte, Allen. 1964. "A Theory of Set-Complexes for Music". Journal of Music Theory 8, no. 2

(Winter): 13683.

Forte, Allen. 1965. "The Domain and Relations of Set-Complex Theory". Journal of Music Theory 9,

no. 1 (Spring): 17380.

Forte, Allen. 1972. Sets and Nonsets in Schoenberg's Atonal Music. Perspectives of New Music 11,

no. 1 (FallWinter): 4364.

Forte, Allen. 1978. The Harmonic Organization of The Rite of Spring. New Haven : Yale University

Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02201-8.

Forte, Allen. 1978. "Schoenberg's Creative Evolution: The Path to Atonality". The Musical Quarterly

64, no. 2 (April): 13376.

Forte, Allen. 1980. "Aspects of Rhythm in Webern's Atonal Music". Music Theory Spectrum 2:90

109.

Forte, Allen. 1998. The Atonal Music of Anton Webern. New Haven and London: Yale University

Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07352-2.

Forte, Allen, and Roy Travis. 1974. "Analysis Symposium: Webern, Orchestral Pieces (1913):

Movement I ('Bewegt')". Journal of Music Theory 18, no. 1 (Spring, pp. 2-43

Krausz, Michael. 1984. "The Tonal and the Foundational: Ansermet on Stravinsky". The Journal of

Aesthetics and Art Criticism 42:38386.

Philippot, Michel. 1964. "Ansermets Phenomenological Metamorphoses." Translated by Edward

Messinger. Perspectives of New Music 2, no. 2 (Spring-Summer): 12940. Originally published as

"Mtamorphoses Phnomnologiques."

(http://www.entretemps.asso.fr/Philippot/Ecrits/11.Metamorphoses.html) Critique. Revue Gnrale des

Publications Franaises et Etrangres, no. 186 (November 1962).

Radano, Ronald M. 1993. New Musical Figurations: Anthony Braxton's Cultural Critique Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

External links

An Introduction to Atonal Music Analysis (http://www.robertkelleyphd.com/12-tone.htm) by Robert T.

Kelly.

Atonality, Information, and the Politics of Perception

(http://www.thinkingapplied.com/tonality_folder/tonality.htm) by Lee Humphries

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Atonality&oldid=610541729"

Categories: Musical techniques Post-tonal music theory

This page was last modified on 28 May 2014 at 20:26.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may

apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia is a registered

trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

Вам также может понравиться

- A Primer For Atonal Set TheoryДокумент20 страницA Primer For Atonal Set TheoryHenrique97489573496Оценок пока нет

- Empirically Testing Tonnetz, Voice-Leading, and Spectral Models of Perceived Triadic DistanceДокумент26 страницEmpirically Testing Tonnetz, Voice-Leading, and Spectral Models of Perceived Triadic Distanceorbs100% (1)

- Theory Basics - 12 Chromatic Tones PDFДокумент2 страницыTheory Basics - 12 Chromatic Tones PDFPramod Govind SalunkheОценок пока нет

- Xenakis Electronic MusicДокумент1 страницаXenakis Electronic MusicCharlex López100% (1)

- Leedy & Corey - Tuning Systems (Grove)Документ8 страницLeedy & Corey - Tuning Systems (Grove)tunca_olcaytoОценок пока нет

- 0 - Zieht 11 - Full ScoreДокумент37 страниц0 - Zieht 11 - Full ScoreOnur Dülger100% (1)

- Coriolan Three Key ExpositionДокумент23 страницыCoriolan Three Key ExpositionIsabel Rubio100% (1)

- Musical Composers HungaryДокумент46 страницMusical Composers HungaryIvan Paul CandoОценок пока нет

- Furnace Fugue Music EditionДокумент168 страницFurnace Fugue Music EditionCaveat EmptorОценок пока нет

- The Structural Function of Musical Textu PDFДокумент7 страницThe Structural Function of Musical Textu PDFMarcello Ferreira Soares Jr.Оценок пока нет

- Just Intonation Guitar Chord Atlas by DotyДокумент26 страницJust Intonation Guitar Chord Atlas by DotyGeorge Christian Vilela PereiraОценок пока нет

- Bring Da Noise A Brief Survey of Sound ArtДокумент3 страницыBring Da Noise A Brief Survey of Sound ArtancutaОценок пока нет

- Cage Cunningham Collaborators PDFДокумент23 страницыCage Cunningham Collaborators PDFmarialakkaОценок пока нет

- Scale Systems and Large-Scale Form in The Music of Yes: Brett G. ClementДокумент16 страницScale Systems and Large-Scale Form in The Music of Yes: Brett G. ClementDiego Spi100% (1)

- Moscovich Viviana French Spectral Music An IntroductionДокумент8 страницMoscovich Viviana French Spectral Music An IntroductionbeniaminОценок пока нет

- Edgar VareseДокумент4 страницыEdgar VareseJulio TorresОценок пока нет

- Scelsi, Giacinto - Piano WorksДокумент2 страницыScelsi, Giacinto - Piano WorksMelisa CanteroОценок пока нет

- Ostrava Days 2003 - Tristan Murail Lecture PDFДокумент3 страницыOstrava Days 2003 - Tristan Murail Lecture PDFCaterina100% (1)

- SLAWSON - The Color of SoundДокумент11 страницSLAWSON - The Color of SoundEmmaОценок пока нет

- Richard S Hill Twelve Tone PaperДокумент16 страницRichard S Hill Twelve Tone PaperScott McGill100% (1)

- Melodic ConsonanceДокумент18 страницMelodic ConsonanceCoie8t100% (2)

- Anatomy of A Melody Part 1Документ3 страницыAnatomy of A Melody Part 1jim4703100% (2)

- VISUAL Music. Bibliograqfiìa y Webs. Antonio FernandezДокумент9 страницVISUAL Music. Bibliograqfiìa y Webs. Antonio FernandezJoão SantosОценок пока нет

- Equal TemperamentДокумент16 страницEqual TemperamenthbОценок пока нет

- Bitonality, Mode, and Interval in The Music of Karol SzymanowskiДокумент25 страницBitonality, Mode, and Interval in The Music of Karol SzymanowskiDaniel Perez100% (1)

- Intro and Literature ReviewДокумент17 страницIntro and Literature ReviewYiyi GaoОценок пока нет

- Spectral Music (FR.: Musique Spectrale) : Published in Print: 20 January 2001 Published Online: 2001Документ3 страницыSpectral Music (FR.: Musique Spectrale) : Published in Print: 20 January 2001 Published Online: 2001CortadoОценок пока нет

- MusiksemiotikДокумент110 страницMusiksemiotikIin Katharina100% (1)

- Xenakis' Keren: A Computational Semiotic AnalysisДокумент17 страницXenakis' Keren: A Computational Semiotic AnalysisandrewОценок пока нет

- Rwannamaker North American Spectralism PDFДокумент21 страницаRwannamaker North American Spectralism PDFImri TalgamОценок пока нет

- Space Resonating Through Sound - Iazzetta y Campesato PDFДокумент6 страницSpace Resonating Through Sound - Iazzetta y Campesato PDFlucianoo_kОценок пока нет

- Counterpoint Textbook FeraruДокумент44 страницыCounterpoint Textbook Feraruurmom com100% (1)

- Goal Directed BartokДокумент9 страницGoal Directed BartokEl Roy M.T.Оценок пока нет

- Lutoslawsky in Retrospect (Stucky)Документ4 страницыLutoslawsky in Retrospect (Stucky)letrouvereОценок пока нет

- Webern Sketches IДокумент13 страницWebern Sketches Imetronomme100% (1)

- Atonal MusicДокумент6 страницAtonal MusicBobby StaraceОценок пока нет

- Deviant Cadential Six-Four Chords: Gabriel FankhauserДокумент11 страницDeviant Cadential Six-Four Chords: Gabriel FankhauserZoran Nastov100% (1)

- Russian Submediant - UnknownДокумент29 страницRussian Submediant - UnknownvoodoodaveОценок пока нет

- The Role of Melodic and Rhythmic Accents in Musical StructureДокумент35 страницThe Role of Melodic and Rhythmic Accents in Musical StructurechrisОценок пока нет

- Schonberg An Analysis of Large Structures Found Within Pierrol Lunaire (Nelson)Документ6 страницSchonberg An Analysis of Large Structures Found Within Pierrol Lunaire (Nelson)letrouvereОценок пока нет

- Techicques SchoenbergДокумент10 страницTechicques SchoenbergAntonis KanavourasОценок пока нет

- Geometric ChordsДокумент37 страницGeometric ChordsnachobellidoОценок пока нет

- Impressionism AssignmentsДокумент2 страницыImpressionism Assignmentsahmad konyОценок пока нет

- The Whispering Voice Materiality Aural Qualities and The Reconstruction of Memories in The Works of Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller Tina Rigby HanssenДокумент17 страницThe Whispering Voice Materiality Aural Qualities and The Reconstruction of Memories in The Works of Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller Tina Rigby HanssenTiago CamposОценок пока нет

- Lerdahl 2005 Tonal Pitch Space Biliography PDFДокумент21 страницаLerdahl 2005 Tonal Pitch Space Biliography PDFATОценок пока нет

- Gerard Grisey: The Web AngelfireДокумент8 страницGerard Grisey: The Web AngelfirecgaineyОценок пока нет

- Interview With Stuart Saunders Smith and Sylvia Smith Notations 21Документ10 страницInterview With Stuart Saunders Smith and Sylvia Smith Notations 21artnouveau11Оценок пока нет

- MCG2B9 Debussy 2021Документ43 страницыMCG2B9 Debussy 2021Youngjae KimОценок пока нет

- A Chronology of Electronic and Computer Music and Related Events 1906 - 2013Документ50 страницA Chronology of Electronic and Computer Music and Related Events 1906 - 2013Giorgio BossoОценок пока нет

- Realtime Stochastic Decision Making For Music Composition and ImprovisationДокумент15 страницRealtime Stochastic Decision Making For Music Composition and ImprovisationImri Talgam100% (1)

- The Theory of Pitch-Class SetsДокумент18 страницThe Theory of Pitch-Class SetsBen Mandoza100% (1)

- General Interval SystemДокумент14 страницGeneral Interval Systemmarco antonio Encinas100% (1)

- How To (Not) Teach CompositionДокумент14 страницHow To (Not) Teach CompositionAndrew100% (1)

- Tone ClusterДокумент12 страницTone ClusterVictorSmerk100% (1)

- Kompositionen für hörbaren Raum / Compositions for Audible Space: Die frühe elektroakustische Musik und ihre Kontexte / The Early Electroacoustic Music and its ContextsОт EverandKompositionen für hörbaren Raum / Compositions for Audible Space: Die frühe elektroakustische Musik und ihre Kontexte / The Early Electroacoustic Music and its ContextsОценок пока нет

- Telemann Viola Conc HPSCRDДокумент14 страницTelemann Viola Conc HPSCRDJorge Alberto Medina LopezОценок пока нет

- (Classical) Ludwig Van BeethovenДокумент9 страниц(Classical) Ludwig Van BeethovenPaulo Cesar Maia de Aguiar(Composer)Оценок пока нет

- Tarot Overview SmallДокумент2 страницыTarot Overview SmallPaulo Cesar Maia de Aguiar(Composer)Оценок пока нет

- (Classical) Ludwig Van BeethovenДокумент9 страниц(Classical) Ludwig Van BeethovenPaulo Cesar Maia de Aguiar(Composer)Оценок пока нет

- Augmented FifthДокумент2 страницыAugmented FifthPaulo Cesar Maia de Aguiar(Composer)Оценок пока нет

- Composer Dictionary For WebsiteДокумент46 страницComposer Dictionary For WebsitePaulo Cesar Maia de Aguiar(Composer)100% (1)

- 15 Pallava ArchitectureДокумент2 страницы15 Pallava ArchitectureMadhu BabuОценок пока нет

- Music 1ST QTRДокумент4 страницыMusic 1ST QTRShapee Manzanitas100% (2)

- Rimska ArhitekturaДокумент11 страницRimska ArhitekturadebbronnerfilesОценок пока нет

- Sorsogon Folk SongsДокумент7 страницSorsogon Folk SongsAngelika Mae BalisbisОценок пока нет

- Sample of Exemplification EssayДокумент7 страницSample of Exemplification Essayafabidbyx100% (2)

- The Moldau AnalysisДокумент3 страницыThe Moldau AnalysisChristoph Kirch100% (7)

- Granada For Harp 00 LaraДокумент14 страницGranada For Harp 00 LaraTimo HoeperОценок пока нет

- Love Me ParedДокумент10 страницLove Me PareddanyОценок пока нет

- Quitoy FeatureДокумент2 страницыQuitoy FeatureJose Erwin BorbonОценок пока нет

- Carlo Ginzburg Clues Myths and The Historical Method MinДокумент245 страницCarlo Ginzburg Clues Myths and The Historical Method MinNishant Singh100% (2)

- Flute S1 - International School of MusiciansДокумент12 страницFlute S1 - International School of Musiciansalvarogc_207923Оценок пока нет

- Zlittle Prince BlueДокумент9 страницZlittle Prince BlueMariana Anchepe92% (24)

- Bourdieu e A Sociologia Da MúsicaДокумент13 страницBourdieu e A Sociologia Da MúsicaDavi Ribeiro GirardiОценок пока нет

- Humanities: Our Lady of The Pillar College - San Manuel, IncorporatedДокумент16 страницHumanities: Our Lady of The Pillar College - San Manuel, IncorporatedJayson DoctorОценок пока нет

- We Are The World PianoДокумент4 страницыWe Are The World PianoLuis MRudaОценок пока нет

- All S3RL SongsДокумент6 страницAll S3RL SongsMichele ArmelliniОценок пока нет

- SPENCER - Spatial Imagery of Annunciation FlorenceДокумент11 страницSPENCER - Spatial Imagery of Annunciation FlorenceMarta SimõesОценок пока нет

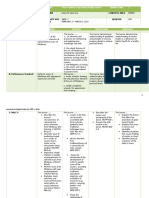

- DLL - WEEK 3 Q3-Grade-7-DLL-ROMA DELA CRUZДокумент8 страницDLL - WEEK 3 Q3-Grade-7-DLL-ROMA DELA CRUZRoma Dela Cruz - CayaoОценок пока нет

- Plate No.1 Free Hand DrawingДокумент1 страницаPlate No.1 Free Hand DrawingMAYTHEL CANECIOОценок пока нет

- Grade 7-10 3rd Quarter Exam..Документ6 страницGrade 7-10 3rd Quarter Exam..Benjonit CapulongОценок пока нет

- Schapiro-"Courbet and Popular Imagery... "-1942 PDFДокумент32 страницыSchapiro-"Courbet and Popular Imagery... "-1942 PDFAlexMingjianHeОценок пока нет

- Week 11 To 20: Creative Writing - Dane GammadДокумент38 страницWeek 11 To 20: Creative Writing - Dane GammadRia BarisoОценок пока нет

- Just Intonation in 20th-21st Century Western Music - Final Paper - Ashish DhaДокумент9 страницJust Intonation in 20th-21st Century Western Music - Final Paper - Ashish DhaAshish DhaОценок пока нет

- 22 BookReviewsДокумент36 страниц22 BookReviewsAhtesham AliОценок пока нет

- 17 Yoruba Drum PoetryДокумент11 страниц17 Yoruba Drum Poetryajibade ademola100% (1)

- Wallaschek Primitivemusic PDFДокумент380 страницWallaschek Primitivemusic PDFAnastasiia MazurenkoОценок пока нет

- Approved Courses For Humanities Credit Outside of TandonДокумент100 страницApproved Courses For Humanities Credit Outside of TandonpodolskiОценок пока нет

- PreviewpdfДокумент32 страницыPreviewpdfOrkun TürkmenОценок пока нет

- Classical Music AnalysisДокумент2 страницыClassical Music AnalysisMarie Patrice LehОценок пока нет

- Karnataka Government Music Examination SyllabusДокумент18 страницKarnataka Government Music Examination Syllabuskamaleshaiah88% (73)