Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

CIR vs. Algue Inc

Загружено:

Oliver Reidsil M. Rojales0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

17 просмотров2 страницыTaxation

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

DOC, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документTaxation

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOC, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

17 просмотров2 страницыCIR vs. Algue Inc

Загружено:

Oliver Reidsil M. RojalesTaxation

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOC, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 2

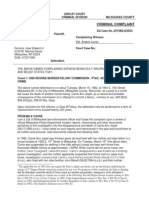

G.R. No.

L-28896 February 17, 1988

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENE, petitioner,

vs.

ALGE, INC., a!" T#E CORT OF TA$ A%%EALS, respondents.

CR&, J.:

Taxes are the lifeblood of the government and so should be collected without unnecessary hindrance On the other hand, such collection should be

made in accordance with law as any arbitrariness will negate the very reason for government itself. It is therefore necessary to reconcile the

apparently conflicting interests of the authorities and the taxpayers so that the real purpose of taxation, which is the promotion of the common good,

may be achieved.

The main issue in this case is whether or not the Collector of Internal Revenue correctly disallowed the P!,"""."" deduction claimed by private

respondent #lgue as legitimate business expenses in its income tax returns. The corollary issue is whether or not the appeal of the private

respondent from the decision of the Collector of Internal Revenue was made on time and in accordance with law.

$e deal first with the procedural %uestion.

The record shows that on &anuary '(, ')*!, the private respondent, a domestic corporation engaged in engineering, construction and other allied

activities, received a letter from the petitioner assessing it in the total amount of P+,,'+,.+! as delin%uency income taxes for the years ')!+ and

')!).

1

On &anuary '+, ')*!, #lgue flied a letter of protest or re%uest for reconsideration, which letter was stamp received on the same day in the

office of the petitioner.

2

On -arch '., ')*!, a warrant of distraint and levy was presented to the private respondent, through its counsel, #tty.

#lberto /uevara, &r., who refused to receive it on the ground of the pending protest.

'

# search of the protest in the doc0ets of the case proved

fruitless. #tty. /uevara produced his file copy and gave a photostat to 1IR agent Ramon Reyes, who deferred service of the warrant.

(

On #pril ,

')*!, #tty. /uevara was finally informed that the 1IR was not ta0ing any action on the protest and it was only then that he accepted the warrant of

distraint and levy earlier sought to be served.

)

2ixteen days later, on #pril .,, ')*!, #lgue filed a petition for review of the decision of the

Commissioner of Internal Revenue with the Court of Tax #ppeals.

6

The above chronology shows that the petition was filed seasonably. #ccording to Rep. #ct 3o. ''.!, the appeal may be made within thirty days after

receipt of the decision or ruling challenged.

7

It is true that as a rule the warrant of distraint and levy is 4proof of the finality of the assessment4

8

and

renders hopeless a re%uest for reconsideration,4

9

being 4tantamount to an outright denial thereof and ma0es the said re%uest deemed

re5ected.4

1*

1ut there is a special circumstance in the case at bar that prevents application of this accepted doctrine.

The proven fact is that four days after the private respondent received the petitioner6s notice of assessment, it filed its letter of protest. This was

apparently not ta0en into account before the warrant of distraint and levy was issued7 indeed, such protest could not be located in the office of the

petitioner. It was only after #tty. /uevara gave the 1IR a copy of the protest that it was, if at all, considered by the tax authorities. 8uring the

intervening period, the warrant was premature and could therefore not be served.

#s the Court of Tax #ppeals correctly noted,4

11

the protest filed by private respondent was not pro forma and was based on strong legal

considerations. It thus had the effect of suspending on &anuary '+, ')*!, when it was filed, the reglementary period which started on the date the

assessment was received, vi9., &anuary '(, ')*!. The period started running again only on #pril , ')*!, when the private respondent was definitely

informed of the implied re5ection of the said protest and the warrant was finally served on it. :ence, when the appeal was filed on #pril .,, ')*!, only

." days of the reglementary period had been consumed.

3ow for the substantive %uestion.

The petitioner contends that the claimed deduction of P!,"""."" was properly disallowed because it was not an ordinary reasonable or necessary

business expense. The Court of Tax #ppeals had seen it differently. #greeing with #lgue, it held that the said amount had been legitimately paid by

the private respondent for actual services rendered. The payment was in the form of promotional fees. These were collected by the Payees for their

wor0 in the creation of the ;egetable Oil Investment Corporation of the Philippines and its subse%uent purchase of the properties of the Philippine

2ugar <state 8evelopment Company.

Parenthetically, it may be observed that the petitioner had Originally claimed these promotional fees to be personal holding company income

12

but

later conformed to the decision of the respondent court re5ecting this assertion.

1'

In fact, as the said court found, the amount was earned through the

5oint efforts of the persons among whom it was distributed It has been established that the Philippine 2ugar <state 8evelopment Company had

earlier appointed #lgue as its agent, authori9ing it to sell its land, factories and oil manufacturing process. Pursuant to such authority, #lberto

/uevara, &r., <duardo /uevara, Isabel /uevara, <dith, O6=arell, and Pablo 2anche9, wor0ed for the formation of the ;egetable Oil Investment

Corporation, inducing other persons to invest in it.

1(

>ltimately, after its incorporation largely through the promotion of the said persons, this new

corporation purchased the P2<8C properties.

1)

=or this sale, #lgue received as agent a commission of P'.*,"""."", and it was from this

commission that the P!,"""."" promotional fees were paid to the aforenamed individuals.

16

There is no dispute that the payees duly reported their respective shares of the fees in their income tax returns and paid the corresponding taxes

thereon.

17

The Court of Tax #ppeals also found, after examining the evidence, that no distribution of dividends was involved.

18

The petitioner claims that these payments are fictitious because most of the payees are members of the same family in control of #lgue. It is argued

that no indication was made as to how such payments were made, whether by chec0 or in cash, and there is not enough substantiation of such

payments. In short, the petitioner suggests a tax dodge, an attempt to evade a legitimate assessment by involving an imaginary deduction.

$e find that these suspicions were ade%uately met by the private respondent when its President, #lberto /uevara, and the accountant, Cecilia ;. de

&esus, testified that the payments were not made in one lump sum but periodically and in different amounts as each payee6s need arose.

19

It should

be remembered that this was a family corporation where strict business procedures were not applied and immediate issuance of receipts was not

re%uired. <ven so, at the end of the year, when the boo0s were to be closed, each payee made an accounting of all of the fees received by him or

her, to ma0e up the total of P!,"""."".

2*

#dmittedly, everything seemed to be informal. This arrangement was understandable, however, in view of

the close relationship among the persons in the family corporation.

$e agree with the respondent court that the amount of the promotional fees was not excessive. The total commission paid by the Philippine 2ugar

<state 8evelopment Co. to the private respondent was P'.!,"""."".

21

#fter deducting the said fees, #lgue still had a balance of P!","""."" as

clear profit from the transaction. The amount of P!,"""."" was *"? of the total commission. This was a reasonable proportion, considering that it

was the payees who did practically everything, from the formation of the ;egetable Oil Investment Corporation to the actual purchase by it of the

2ugar <state properties. This finding of the respondent court is in accord with the following provision of the Tax Code@

2<C. ,". Deductions from gross income.AAIn computing net income there shall be allowed as deductions B

CaD <xpenses@

C'D In general.AA#ll the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred during the taxable year in carrying on any trade or

business, including a reasonable allowance for salaries or other compensation for personal services actually rendered7 ...

22

and Revenue Regulations 3o. ., 2ection " C'D, reading as follows@

2<C. ". Compensation for personal services.AA#mong the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred in carrying on any

trade or business may be included a reasonable allowance for salaries or other compensation for personal services actually

rendered. The test of deductibility in the case of compensation payments is whether they are reasonable and are, in fact,

payments purely for service. This test and deductibility in the case of compensation payments is whether they are reasonable

and are, in fact, payments purely for service. This test and its practical application may be further stated and illustrated as

follows@

#ny amount paid in the form of compensation, but not in fact as the purchase price of services, is not deductible. CaD #n

ostensible salary paid by a corporation may be a distribution of a dividend on stoc0. This is li0ely to occur in the case of a

corporation having few stoc0holders, Practically all of whom draw salaries. If in such a case the salaries are in excess of those

ordinarily paid for similar services, and the excessive payment correspond or bear a close relationship to the stoc0holdings of the

officers of employees, it would seem li0ely that the salaries are not paid wholly for services rendered, but the excessive

payments are a distribution of earnings upon the stoc0. . . . CPromulgated =eb. '', '),', ," O./. 3o. '+, ,.!.D

It is worth noting at this point that most of the payees were not in the regular employ of #lgue nor were they its controlling stoc0holders.

2'

The 2olicitor /eneral is correct when he says that the burden is on the taxpayer to prove the validity of the claimed deduction. In the present case,

however, we find that the onus has been discharged satisfactorily. The private respondent has proved that the payment of the fees was necessary

and reasonable in the light of the efforts exerted by the payees in inducing investors and prominent businessmen to venture in an experimental

enterprise and involve themselves in a new business re%uiring millions of pesos. This was no mean feat and should be, as it was, sufficiently

recompensed.

It is said that taxes are what we pay for civili9ation society. $ithout taxes, the government would be paraly9ed for lac0 of the motive power to

activate and operate it. :ence, despite the natural reluctance to surrender part of one6s hard earned income to the taxing authorities, every person

who is able to must contribute his share in the running of the government. The government for its part, is expected to respond in the form of tangible

and intangible benefits intended to improve the lives of the people and enhance their moral and material values. This symbiotic relationship is the

rationale of taxation and should dispel the erroneous notion that it is an arbitrary method of exaction by those in the seat of power.

1ut even as we concede the inevitability and indispensability of taxation, it is a re%uirement in all democratic regimes that it be exercised reasonably

and in accordance with the prescribed procedure. If it is not, then the taxpayer has a right to complain and the courts will then come to his succor.

=or all the awesome power of the tax collector, he may still be stopped in his trac0s if the taxpayer can demonstrate, as it has here, that the law has

not been observed.

$e hold that the appeal of the private respondent from the decision of the petitioner was filed on time with the respondent court in accordance with

Rep. #ct 3o. ''.!. #nd we also find that the claimed deduction by the private respondent was permitted under the Internal Revenue Code and

should therefore not have been disallowed by the petitioner.

#CCOR8I3/EF, the appealed decision of the Court of Tax #ppeals is #==IR-<8 in toto, without costs.

2O OR8<R<8.

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1091)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Strawman IllusionДокумент3 страницыThe Strawman IllusionSaVanTx75% (4)

- Jose Ferreira Criminal ComplaintДокумент4 страницыJose Ferreira Criminal ComplaintDavid Lohr100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Domenico Losurdo, David Ferreira - Stalin - The History and Critique of A Black Legend (2019)Документ248 страницDomenico Losurdo, David Ferreira - Stalin - The History and Critique of A Black Legend (2019)PartigianoОценок пока нет

- Notes in Torts (Jurado, 2009)Документ5 страницNotes in Torts (Jurado, 2009)Lemwil Aruta SaclayОценок пока нет

- Public-International-Law Reviewer Isagani CruzДокумент89 страницPublic-International-Law Reviewer Isagani Cruzricohizon9990% (31)

- G.R. No. L-36142. March 31, 1973 DigestДокумент3 страницыG.R. No. L-36142. March 31, 1973 DigestMaritoni RoxasОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 175097 Allied Banking Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Respondent. Del Castillo, J.Документ2 страницыG.R. No. 175097 Allied Banking Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Respondent. Del Castillo, J.thelionleo1Оценок пока нет

- Documentary Stamp TaxДокумент3 страницыDocumentary Stamp TaxOliver Reidsil M. RojalesОценок пока нет

- Torio Vs Fontanilla (Case Digest)Документ1 страницаTorio Vs Fontanilla (Case Digest)Oliver Reidsil M. Rojales100% (1)

- IssuesДокумент2 страницыIssuesmary100% (3)

- Carriage of PassengersДокумент5 страницCarriage of PassengersLoueljie AntiguaОценок пока нет

- Soler Vs CA FulltextДокумент3 страницыSoler Vs CA FulltextOliver Reidsil M. RojalesОценок пока нет

- Lyceum of The Philippines vs. Ca 219 SCRA 610: FactsДокумент2 страницыLyceum of The Philippines vs. Ca 219 SCRA 610: FactsOliver Reidsil M. RojalesОценок пока нет

- Republic Act No 7160 - Local Government Code of 1991Документ21 страницаRepublic Act No 7160 - Local Government Code of 1991Oliver Reidsil M. RojalesОценок пока нет

- Anti-Hazing Law of The PhilippinesДокумент3 страницыAnti-Hazing Law of The PhilippinesOliver Reidsil M. RojalesОценок пока нет

- Assessment 1Документ7 страницAssessment 1zakiatalha0% (1)

- RPT - CollectionДокумент3 страницыRPT - CollectionKezОценок пока нет

- Abalos v. Macatangay, JR., (G.R. No. 155043 September 30, 2004)Документ18 страницAbalos v. Macatangay, JR., (G.R. No. 155043 September 30, 2004)Leizl A. VillapandoОценок пока нет

- PCIB Vs BalmacedaДокумент11 страницPCIB Vs BalmacedaBeverlyn JamisonОценок пока нет

- Syllabus CPLДокумент2 страницыSyllabus CPLLogan DavisОценок пока нет

- Gideon Matthews 36962325 CRW2601 Exam PDFДокумент4 страницыGideon Matthews 36962325 CRW2601 Exam PDFGideon MatthewsОценок пока нет

- Legislative Process FlowchartДокумент1 страницаLegislative Process FlowchartElizabeth Delgado-SavageОценок пока нет

- State Bank of India Vs Sarathi Textiles and Ors 21SC2002080818160429152COM54278Документ2 страницыState Bank of India Vs Sarathi Textiles and Ors 21SC2002080818160429152COM54278Advocate UtkarshОценок пока нет

- Contracts ProjectДокумент38 страницContracts Projectkrapanshu rathiОценок пока нет

- Marina vs. Coa GR No. 185812 Jan. 13, 2015 Facts:: ChanroblesvirtuallДокумент2 страницыMarina vs. Coa GR No. 185812 Jan. 13, 2015 Facts:: ChanroblesvirtuallJessica PulgaОценок пока нет

- JatinДокумент1 страницаJatinhappybhogpurОценок пока нет

- C45 - Fiji Resolution - FINALДокумент3 страницыC45 - Fiji Resolution - FINALIntelligentsiya HqОценок пока нет

- Alabang Development Corp. v. Valenzuela, GR L-54094, Aug. 30, 1982, 116 SCRA 261Документ1 страницаAlabang Development Corp. v. Valenzuela, GR L-54094, Aug. 30, 1982, 116 SCRA 261Gia DimayugaОценок пока нет

- RFD Employment ApplicationДокумент2 страницыRFD Employment ApplicationusmjacksonalumОценок пока нет

- Punjab High CourtДокумент12 страницPunjab High CourtpvigneshwarrajuОценок пока нет

- Candida Virata vs. Victorio OchoaДокумент3 страницыCandida Virata vs. Victorio OchoaKristine KristineeeОценок пока нет

- Internation Police Organization Member CountriesДокумент128 страницInternation Police Organization Member CountriesReincar Angel Ruiz GarciaОценок пока нет

- Jurisprudence - TutorialДокумент2 страницыJurisprudence - TutorialNelfi Amiera MizanОценок пока нет

- Claim Form For Physical InjuryДокумент2 страницыClaim Form For Physical InjuryMichael_Lee_RobertsОценок пока нет

- Human Trafficking BrochureДокумент2 страницыHuman Trafficking Brochureapi-251031082Оценок пока нет

- List of Intl DelegatesДокумент3 страницыList of Intl DelegatesAhsan Mohiuddin100% (1)

- Advocacy and Community PlanningДокумент4 страницыAdvocacy and Community PlanningNurshazwani OsmanОценок пока нет