Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Global LCC Outlook v2

Загружено:

JcastrosilvaИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Global LCC Outlook v2

Загружено:

JcastrosilvaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

2

Published by

Level 4, Aurora Place, 88 Phillip St

Sydney NSW 2000, Australia

Tel: + 61 - (02) 9241 3200

Fax: + 61 - (02) 9241 3400

publications@centreforaviation.com

www.centreforaviation.com

Principal Authors:

Peter Harbison and Dr Phil McDermott

Contributors:

Derek Sadubin and Liz Thomson

2009 Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation

No part of this publication may be reproduced, or transmitted in any form,

without the prior permission of Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation. This report is

for internal use only by full time employees of the purchasing company.

Dates and coverage:

Part One of this report covers developments up to and including October-

2009, while Part Two covers the period up to June 2009. For more recent

carrier updates, please refer to www.centreforaviation.com/profiles/airlines

Disclaimer:

Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation has made every effort to ensure the accuracy

of the information contained in this publication. The Centre does not accept

any legal responsibility for consequences that may arise from errors,

omissions or any opinions given. This publication is not a substitute for

specific professional advice on commercial or other matters.

3

Foreword

The airline industry has changed. Take Ryanair for example. It is

profitable, while many are deep in red ink even in the UKs

deepest recession in 80 years. And it is still expanding at breakneck

pace. Meanwhile, Southwest Airlines, the global role model, lost

money in four of the last five quarters, after 30 unbroken years of

profits.

Look at how Ryanair is profitable: over 21% of its revenue is

ancillary, from charges for non-essential items, previously taken

for granted on airlines with frills.

Yet Ryanair showed a 17.6% net return on total revenue (which

was flat year-on-year) for the first quarter of its financial year

ended 30-Jun-2009. Ryanairs ancillary revenues outpaced

scheduled traffic growth and rose by 13% in the first quarter to

EUR165.3 million. Net profit rose 550% to EUR136.5 million.

In other words, had it not been for that 21% of non-essential

payments, it too would have been deeply in the red. Meanwhile,

legacy airlines in the US will generate billions this year from similar

ancillaries (including baggage fees). That is just one way that the

industry has evolved.

In this wide-ranging report, we do not seek to cover every aspect of

the airline industry, nor do we expect to escape unscathed from

either purists who will debate every definition nor even many who

will quite appropriately correct errors we have made.

For the latter we apologise. But we felt it was worth the effort to try

to capture in words and some numbers - a period in which the

industry has been transformed. As our contribution to recording a

piece of the history of this infinitely fascinating business, we hope

you will find it of value.

The Centre has been privileged to work with many of the airlines

and personalities identified in this report over many years. From

first working with Ray Webster later to be founding CEO of

easyJet on developing a Southwest-inspired LCC airline model in

the early 1990s, through continuing contacts with most of the LCCs

in Asia and the Middle East, then later Europe and north America,

we consider ourselves fortunate to have witnessed at first hand the

remarkable transformation of the airline industry which these

airlines have driven.

This movement, which has now become very

much part of the mainstream, has changed

the world. And, what is more, there is a lot

more excitement to come.

We welcome your feedback, so please

Peter Harbison

Executive Chairman

Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation

October 2009

4

Acknowledgements

Our special thanks to the following for their

valuable contributions to this report:

Professor Michael E. Levine

Professor Nawal Taneja

Bill Franke, Indigo Partners

Dr Julius Maldutis

Jim Parker, Raymond James

Gary Kelly, CEO Southwest Airlines

Dave Barger, CEO, JetBlue Airways

Adel Ali, CEO Air Arabia

Sanjay Aggarwal, CEO SpiceJet

Azran Osman-Rani, CEO AirAsia X

Nico Bezuidenhout, CEO Mango

Bruce Buchanan, CEO Jetstar

Michael Cawley, Deputy CEO and COO of

Ryanair

Alex Cruz, CEO Vueling

David Cush, CEO Virgin America

Tony Fernandes, CEO AirAsia

Brett Godfrey, CEO Virgin Blue

Jin Air, Korean Air LCC subsidiary

Yasuyushi Motu, former CEO, Adviser to the

President, Starflyer

Gidon Novak, CEO Kulula/Comair

Kevin Steele, CEO Sama

Tero Taskila, CCO airbaltic

Nigel Turner, CEO bmibaby

Wang Zhenghua, President Spring Airlines

About The Centre

Established in 1990, the Centre for Asia

Pacific Aviation is a leading provider of

independent aviation market intelligence,

covering worldwide developments, analysis

and data services.

The Centre produces a wide range of highly

analytical aviation intelligence reports. All of

these can be accessed either by individual

subscriptions or by becoming a CAPA

Member.

Our range of reports include:

Asia Pacific Airline Daily

Europe Airline Daily

America Airline Daily

Airport Business Daily

Asia Pacific Airline Daily

Peanuts! Weekly

Peanuts! Daily

Airport Investor Monthly

Air Traffic Management Monthly

Monthly Essential China

Monthly Essential India

Monthly Essential Middle East

Airport & Airline Europe

Airport & Airline Asia Pacific

Aviation Executive Monthly

Regulatory Affairs Review

CAPA DATA

Asia Pacific Aviation Outlook 2009

Low Cost Airports & Terminals 2009

The Centres analytical reports and industry

news enable senior executives to stay ahead

of trends and developments in this fast

changing, complex and dynamic industry.

The Centres Membership service provides

your company with access to all of the

aviation market research and analysis you

need to take the right business decisions.

Membership benefits include:

A massive time saving in finding ALL

the information you need. We publish over

150 news/analysis items per day. No other

provider comes close!

A big reduction in your annual spend

on aviation intelligence, with our flat fee for

company-wide access;

High quality analysis and outlook

focus helps you make better business

decisions

Ensures you avoid the feeling that

there are gaps in your teams intelligence

gathering;

Significantly reduced hassle factor

in obtaining reliable and accurate aviation

intelligence.

For further information on the Centres

information and membership services, please

contact: Marcos Best - Tel: +61 2 9241 3200

mb@centreforaviation.com

Professor

Michael E. Levine

Southwest

Gary Kelly, CEO

Professor

Nawal Taneja, CEO

Indigo Partners

Bill Franke, Partner

JetBlue

Dave Barger, CEO

Air Arabia

Adel Ali, CEO

SpiceJet

Sanjay Aggarwal, CEO

AirAsia X

Azran Osman-Rani, CEO

Doctor

Julius Maldutis

Raymond James

Jim Parker, Partner

Mango

Nico Bezuidenhaut, CEO

Virgin Blue

Brett Godfrey, CEO

AirAsia

Tony Fernandes, CEO

Sama

Kevin Steele, CEO

airBaltic

Tero Taskila, CCO

bmi

Nigel Turner, CEO

Jetstar

Bruce Buchanan, CEO

Ryanair

Michael Cawley, COO

Vueling

Alex Cruz, CEO

Virgin America

David Cush, CEO

6

Part I: Review, Performance and Prospects

1 An industry in turmoil .......................................................................................... 14

1.1 How did we get into this mess? .............................................................................. 14

1.2 2008/09: the pendulum swings to a new era ........................................................... 16

1.3 Old airlines dying of sclerosis, new entrants sprouting .......................................... 17

2 LCCs account for all global passenger growth since 2001 ................................... 20

2.1 Two distinctive facets to growth ................................................................................. 23

3 (Not) Defining the Low Cost Carrier .................................................................. 29

3.1 Proliferation and diversification.............................................................................. 29

3.2 Attributes common to low fare airlines and low cost carriers ................................. 31

3.3 Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Making a difference ........................................ 46

4 Distribution & sales and social media ................................................................. 51

4.1 LCCs and Distribution ............................................................................................ 51

4.2 Accessing corporate markets .................................................................................. 54

4.3 Social Media opportunities and... ........................................................................... 55

5 The spread of LCC operations around the world ................................................ 61

5.1 The growth of the Low Cost sector since 2000 ....................................................... 61

The Expansion of LCCs, 2000-2009 ............................................................................. 61

5.2 Drivers of Growth .................................................................................................... 63

5.3 LCC growth by region............................................................................................. 65

5.3.1 North America .......................................................................................... 66

5.3.2 Europe ....................................................................................................... 70

5.3.3 Asia Pacific ............................................................................................... 75

5.3.4 Other Emerging Markets........................................................................... 79

5.3.5 Country Performance ................................................................................ 80

6 The evolving model .............................................................................................. 85

6.1 Hybridisation and evolution ................................................................................... 85

6.1.1 Directions in hybridisation ........................................................................ 85

6.1.2 Other variations on the basic model .......................................................... 88

6.1.3 The Future? Going international, going long haul .................................... 89

6.2 Ancillary revenues: a growth future ........................................................................ 96

6.2.1 Charges for Services: Up-Selling or Downgrading? ................................ 96

6.2.2 Managing Costs or Chasing Revenue? ..................................................... 98

6.2.3 What the consumer pays ........................................................................... 99

6.2.4 A simple equation: ANCILLARIES =PROFIT ..................................... 101

6.2.5 The prospects for ancillary revenue ........................................................ 102

6.2.6 On-line Sales ........................................................................................... 103

6.2.7 Beyond travel products ........................................................................... 103

6.2.8 The Leisure Line ..................................................................................... 104

6.2.9 Cargo carriage ......................................................................................... 105

6.2.10 Frequent Flyer Programmes .................................................................... 106

7 How the legacy airlines have responded ............................................................ 108

7.1 Reduce fares: low fare-high cost, a dangerous formula .....................................109

7.2 LCC Subsidiaries by region ................................................................................... 113

7.2.1 North America ........................................................................................ 113

7.2.2 Europe ..................................................................................................... 113

7

7.2.3 Asia Pacific ............................................................................................. 114

7.3 Reposition: reduce costs and maintain yield differential ......................................120

8 Airport responses ................................................................................................ 125

8.1 A radical change in thinking by airports ...............................................................125

9 Financial performance ........................................................................................ 134

9.1 LCCs as Investments .............................................................................................134

9.2 Investing in LCCs is risky business .......................................................................134

10 Challenges to the low cost model ....................................................................... 138

10.1 Fuel prices and airline performance ......................................................................138

10.1.1 Fuel prices a changed risk profile ........................................................ 140

10.1.2 Avoiding the cost trap ............................................................................. 140

10.1.3 The rising and rising price of fuel ..................................................... 141

10.1.4 Varied airline exposure to fuel prices ..................................................... 142

10.2 The Outlook ...........................................................................................................144

10.3 Aircraft ...................................................................................................................145

10.3.1 Narrowbody development ....................................................................... 145

10.3.2 Aircraft values: September-11 and Great Recession downturns, and

the Outlook.............................................................................................................. 146

10.3.3 One size doesnt fit all ............................................................................ 147

10.3.4 The environmental challenge driving efficiency gains ........................... 148

11 The new economic environment ........................................................................ 150

11.1 Economic outlook ..................................................................................................150

11.2 Impact on aviation .................................................................................................152

12 The Outlook: Great Expectations ...................................................................... 157

12.1 The Outlook for LCCs - and the Airline Industry .................................................157

12.2 The main threats and opportunities for LCCs ....................................................... 171

12.2.1 The Threats ............................................................................................. 171

12.2.2 Opportunities........................................................................................... 177

13 Conclusion: The world has changed and so has the low cost carrier .............. 188

8

Part II: Regional Perspectives

14 Globalisation of LCCs ......................................................................................... 192

14.1 Traffic Growth ........................................................................................................192

14.2 The Role of LCCs ..................................................................................................195

15 North America .................................................................................................... 198

15.1 Market Performance ..............................................................................................198

15.2 The Airlines ............................................................................................................199

15.2.1 WestJ et, Canada ...................................................................................... 200

15.2.2 Sunwing Airlines, Canada ...................................................................... 200

15.2.3 Southwest Airlines .................................................................................. 200

15.2.4 AirTran, USA .......................................................................................... 202

15.2.5 Spirit Airlines, USA ................................................................................ 203

15.2.6 J etBlue, USA........................................................................................... 203

15.2.7 Allegiant Airlines, USA .......................................................................... 204

15.2.8 Frontier Airlines, USA ............................................................................ 206

15.2.9 USA 3000, USA...................................................................................... 207

15.2.10 Virgin America, USA ............................................................................. 207

15.3 Outlook ................................................................................................................. 209

16 Central and South America ................................................................................. 211

16.1 Market Performance .............................................................................................. 211

16.2 The Airlines ............................................................................................................213

16.2.1 Viva Aerobus, Mexico ............................................................................ 213

16.2.2 Avolar, Mexico ....................................................................................... 213

16.2.3 Volaris, Mexico....................................................................................... 213

16.2.4 Interjet, Mexico ....................................................................................... 214

16.2.5 Mexicana Click, Mexico ......................................................................... 214

16.2.6 Gol Airlines, Brazil ................................................................................. 214

16.2.7 Webjet, Brazil ......................................................................................... 216

16.2.8 Azul Brazilia, Brazil ............................................................................... 216

16.3 Outlook ..................................................................................................................218

17 Europe ................................................................................................................ 220

17.1 Market Performance ............................................................................................. 220

17.1.1 Comparative Performance of European LCCs ....................................... 222

17.2 Western Europe The Airlines ............................................................................. 225

17.2.1 Iceland Express, Iceland ......................................................................... 225

17.2.2 Norwegian Air Shuttle, Norway and Sweden ......................................... 225

17.2.3 TUIfly, Germany..................................................................................... 226

17.2.4 Germanwings, Germany ......................................................................... 227

17.2.5 Air Berlin, Germany ............................................................................... 227

17.2.6 Condor, Germany .................................................................................... 228

17.2.7 Niki, Austria ............................................................................................ 229

17.2.8 easyJ et Switzerland ................................................................................. 229

17.2.9 FlyOnAir, Italy ........................................................................................ 230

17.2.10 Air Italy ................................................................................................... 230

17.2.11 Blu-express.com, Italy ............................................................................ 230

17.2.12 Windjet, Italy .......................................................................................... 231

17.2.13 Eurofly, Italy ........................................................................................... 231

9

17.2.14 Meridiana, Italy ....................................................................................... 232

17.2.15 Vueling (Clickair), Spain ........................................................................ 232

17.2.16 Transavia.com, Netherlands, Denmark ................................................... 233

17.2.17 Martinair, Netherlands ............................................................................ 233

17.2.18 Transavia, France .................................................................................... 234

17.2.19 bmibaby, United Kingdom...................................................................... 234

17.2.20 easyJ et, United Kingdom ........................................................................ 234

17.2.21 Flybe, United Kingdom .......................................................................... 236

17.2.22 Flyglobespan, United kingdom ............................................................... 237

17.2.23 J et2.com, United Kingdom ..................................................................... 237

17.2.24 Monarch, United Kingdom ..................................................................... 238

17.2.25 Thomson , United Kingdom ................................................................... 238

17.2.26 Ryanair, Ireland....................................................................................... 239

17.3 Outlook ..................................................................................................................241

17.4 Capacity Growth, Eastern Europe ........................................................................ 243

17.5 Eastern Europe The Airlines ............................................................................. 244

17.5.1 Red Wings, Russia .................................................................................. 244

17.5.2 Sky Express, Russia ................................................................................ 245

17.5.3 Wizz Air, Central Europe ....................................................................... 245

17.5.4 Blue Air, Romania .................................................................................. 247

17.5.5 Belle Air, Albania ................................................................................... 247

17.5.6 Smart Wings, Czech Republic ................................................................ 248

17.6 Outlook ................................................................................................................. 249

18 Africa ................................................................................................................... 251

18.1 Market Performance ..............................................................................................251

18.2 The Airlines ........................................................................................................... 252

18.2.1 Kulula, South Africa ............................................................................... 252

18.2.2 1time, South Africa ................................................................................. 253

18.2.3 Mango, South Africa ............................................................................... 253

18.2.4 Atlas Blue, Morocco ............................................................................... 253

18.2.5 Air Arabia Maroc, Morocco ................................................................... 254

18.2.6 J et4you, Morocco .................................................................................... 254

18.2.7 Kathargo Airlines, Tunisia ...................................................................... 254

18.2.8 Fly540, Kenya ......................................................................................... 254

18.3 Outlook ................................................................................................................. 255

19 Middle East ........................................................................................................ 257

19.1 Market Performance ............................................................................................. 257

19.2 The Airlines ........................................................................................................... 258

19.2.1 Nas Air, Saudi Arabia ............................................................................. 258

19.2.2 Sama Airlines, Saudi Arabia ................................................................... 259

19.2.3 Felix Airways, Yemen ............................................................................ 259

19.2.4 EgyptAir Express .................................................................................... 259

19.2.5 Bahrain Air.............................................................................................. 259

19.2.6 J azeera Airways, Kuwait ........................................................................ 260

19.2.7 flydubai, Dubai, UAE ............................................................................. 260

19.2.8 Air Arabia, Sharjah, UAE ....................................................................... 261

19.3 Outlook ................................................................................................................. 262

20 Northeast Asia .................................................................................................... 264

10

20.1 Market Performance ............................................................................................. 264

20.2 The Airlines ........................................................................................................... 266

20.2.1 Air Busan, South Korea .......................................................................... 266

20.2.2 J eju Air, South Korea .............................................................................. 267

20.2.3 J in Air, South Korea ............................................................................... 267

20.2.4 Yeongnam Air, Hansung Airlines, South Korea .................................... 268

20.2.5 Eastar J et, South Korea ........................................................................... 268

20.2.6 Skymark, J apan ....................................................................................... 268

20.2.7 StarFlyer, J apan....................................................................................... 269

20.2.8 Air Do, J apan .......................................................................................... 269

20.2.9 SkyNet Asia, J apan ................................................................................. 269

20.2.10 Fuji Dream Airlines, J apan ..................................................................... 269

20.2.11 Ibex Airlines, J apan ................................................................................ 270

20.2.12 Air Next .................................................................................................. 270

20.2.13 J AL Express, J apan ................................................................................. 270

20.3 Outlook ..................................................................................................................271

21 China .................................................................................................................. 273

21.1 Market Performance ............................................................................................. 273

21.2 The Airlines ........................................................................................................... 274

21.2.1 J uneyao Airlines...................................................................................... 274

21.2.2 Viva Macau, Macau Special Administrative Region .............................. 274

21.2.3 Okay Airways, China .............................................................................. 275

21.2.4 Spring Airlines, China ............................................................................ 275

21.2.5 Lucky Air, China .................................................................................... 275

21.2.6 China West Air ....................................................................................... 276

21.2.7 United Eagle, China ................................................................................ 276

21.3 Outlook ................................................................................................................. 277

22 Southeast Asia .................................................................................................... 279

22.1 Market Performance ............................................................................................. 279

22.2 The Airlines ........................................................................................................... 280

22.2.1 J etstar Pacific, Vietnam .......................................................................... 280

22.2.2 Indochina Airlines, Vietnam ................................................................... 281

22.2.3 Cebu Pacific, Philippines ........................................................................ 281

22.2.4 Spirit of Manila Airlines, Philippines ..................................................... 282

22.2.5 AirAsia (Malaysia) and AirAsia X, Malaysia ......................................... 282

22.2.6 J etstar Asia, Singapore ............................................................................ 284

22.2.7 Tiger Airways, Singapore ....................................................................... 285

22.2.8 Indonesia AirAsia, Indonesia .................................................................. 286

22.2.9 Mandala Airlines, Indonesia ................................................................... 286

22.2.10 Batavia Air, Indonesia ............................................................................ 287

22.2.11 Citilink, Indonesia ................................................................................... 287

22.2.12 Nok Air, Thailand ................................................................................... 287

22.2.13 One Two GO, Thailand........................................................................... 288

22.2.14 Thai AirAsia, Thailand ........................................................................... 288

22.3 Outlook ................................................................................................................. 290

23 South Asia ........................................................................................................... 292

23.1 Market Performance ............................................................................................. 292

23.2 The Airlines ........................................................................................................... 293

11

23.2.1 SpiceJ et, India ......................................................................................... 293

23.2.2 IndiGo, India ........................................................................................... 294

23.2.3 GoAir, India ............................................................................................ 294

23.2.4 Air India Express, India .......................................................................... 295

23.2.5 Kingfisher Red, India .............................................................................. 295

23.2.6 MDLR, India ........................................................................................... 296

23.2.7 J etLite, India ........................................................................................... 296

23.2.8 J et Airways Konnect, India ..................................................................... 297

23.2.9 Mihin Lanka, Sri Lanka .......................................................................... 297

23.3 Outlook ................................................................................................................. 298

24 Oceania .............................................................................................................. 300

24.1 Market Performance ............................................................................................. 300

24.2 The Airlines ........................................................................................................... 302

24.2.1 Virgin Blue Group, Australia .................................................................. 302

24.2.2 Pacific Blue New Zealand ...................................................................... 304

24.2.3 Polynesian Blue, Samoa.......................................................................... 304

24.2.4 V Australia .............................................................................................. 305

24.2.5 J etstar, Australasia .................................................................................. 306

24.2.6 Tiger Airways, Australia ......................................................................... 307

24.3 Outlook ................................................................................................................. 309

Global LCC Outlook Report 2009

Part One:

Review, performance

and prospects

Global LCC Outlook Report 2009

Chapter 1

An Industry in turmoil

14

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

1 An industry in turmoil

1.1 How did we get into this mess?

The airline industry, never healthy financially, is today in turmoil.

Much of the reason is that the full service model relies on high

yielding traffic to complement a fast-growing leisure market. The

perhaps temporary, but continuing decline of premium demand has

jeopardised the very future of many venerable airlines as a result.

Meanwhile, a changing of the guard had been occurring, as new

entrant, predominantly low cost airlines, have irrevocably rewritten

the fundamentals of airline operations. And, partly driven by this new

format, governments across the word have re-evaluated the outdated

regulatory restrictions designed to protect national airlines which

paradoxically have done so much to ensure an inefficient and

unprofitable system.

This report reviews the evolution and current status of the LCC

model, but makes no apologies for raising as many questions as it

answers about the future of the aviation industry as a whole. This is

indeed an industry in turmoil. And, unlike the way things were a

decade ago, any discussion of low cost airlines implies a review of

the entire industry. Depending on the country or region, LCCs

already account for between a quarter and a half of the market, so

when they shout, everyone hears.

Today, at the crest of another shockwave, as global recession and

the threat of a new pandemic batter travel demand, is as good a

time as any to take stock and look at where we may be headed.

For, while H1N1 swine flu - may be seen as just another in the

string of constant shocks that the industry has had to deal with,

prolonged deep recession appears certain to trigger a more

fundamental shift in the shape of aviation. And it is inevitable that

low cost carriers (LCCs) will have a strong influence on how the

sector emerges from the fundamental changes to the economic and

geo-political relationships that have shaped it until now.

Just as there are no two companies that are identical, so there is no

one LCC model. As experimentation occurs and the individual

airlines are steadily transformed, a proliferation of styles emerges.

This is a Darwinian process; some common evolutionary threads

are evident, with local species rolling out so as best to fit their

particular environmental niches.

The future is not simply for LCCs, nor is it simply for hybrid

versions, or indeed for full service airlines. The one irreversible

outcome of what has happened over the past decade is that the

industry will have the opportunity to be much more diverse in the

future than it was ten years ago and, indeed, than it is today. And

even while it diverges, a convergence of models can increasingly be

detected, as full service airlines mimic LCCs to cut costs and the low

cost airlines add frills to boost yields.

15

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

A very short list of model LCCs

Today, only a handful of airlines can undisputedly be described as

basic model LCCs, which remain brutally focused on cost

reduction to the exclusion of almost all else. These include Ryanair

and Wizz Air in Europe (even though Wizz Air has to operate in a

high-cost airport country); Spirit and Allegiant in the US; Tiger

Airways, Mandala and AirAsia in Asia (although even AirAsia is

diverging from the short haul model, with its long haul offshoot; but

it still has the lowest unit costs in the world); in the Middle East, Air

Arabia is extremely low cost (but has adopted a number of non-core

features); and Indias Indigo, SpiceJet and GoAir are basic models

(but must operate with enormous government fuel taxes).

Southwest, usually cited as the aspirational LCC goal (although

Ryanair is taking that mantle), has long since been obliged to move

from its original hard line strategy, for example adopting

codesharing agreements and serving many of the leading US hub

airports.

But little hope of financial equilibrium

Whatever the outcome of this process, the industry is unlikely to

reach any sort of financial equilibrium. This is an industry that has

never been self-sustaining, despite the fact that it has been so

heavily regulated. While restrictive rules may give the semblance of

stability they have themselves become unsustainable in a world

changing rapidly. Even such regulatory fundamentals as limits on

trans-national ownership of airlines are breaking down. Despite

this, and the need for a dynamic, responsive industry, some

governments are still apparently unable to restrain the urge to

intervene to protect flag carriers, even when those flag carriers

are no longer owned or controlled by the public sector.

LCCs meanwhile have been at the cutting edge of reform, exploiting

and forcing regulatory change. In doing this, they have

demonstrated a capacity for innovation and flexibility in airline

operations. Meanwhile the longer-standing incumbents have merely

been reactive, still emerging from the weight of rules focused on

who should operate and where.

LCCs have demonstrated fast footwork to

take on the incumbents and respond to new

and dynamic markets. And today they face a

real test of their viability, confronted by the

rigours of a prolonged recession without the

comfort of government favour, but only their

cost-efficiency and innovation to rely on.

We welcome your feedback, so please

16

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

1.2 2008/09: the pendulum swings to a new era

Over the past year, the airline industry around the world has ridden

a roller coaster, first attacked by unexpectedly high fuel prices and

then by disappearing demand, as the global economy deflated.

These two shifts offer a microcosm of the past and the future of the

airline industry; that is, the two core factors that have driven the

past and will determine the future. First in 2008, high fuel prices

a major airline cost item helped neutralise the cost profile of

different airline models. High cost carriers and low cost carriers

alike had to suffer the pain of higher costs.

US carriers fuel costs as % of total (per ASM): 2Q2003 vs 2Q2008

Source: Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation and BTS

In that environment the high cost, full service airlines could still

prosper; they had the advantage of being able to differentiate their

higher value/higher cost premium product to generate higher

prices. And passengers then were still prepared to pay those higher

fares. The lower cost, single product carriers had no such upside

luxury, as fuel prices surged to account for more than half their

total costs. The LCCs suffered much higher proportional cost

increases, but could not recover it on the revenue side; their no-

frills product could not justify charging up to 5 times the basic fare

for a seat, as their full service rivals could.

Then, late in the year and into 2009, the momentum shifted.

Premium demand collapsed, as financial institutions and corporate

clients generally were forced to slash travel costs. Even as oil prices

plummeted, demand evaporated. In the space of weeks, fuel prices

fell by more than a hundred dollars a barrel. High cost airlines, now

with empty premium cabins, still had their high costs, but this time

there were only low value customers. The reduction in fuel prices

helped them a little, by reducing costs by perhaps 10-15% of total,

but yields fell an additional 5% and more. This left full service

airlines scrambling to reduce capacity, often by double digit

percentages, in order to stem losses. Even so, most are still losing

money heavily. That applies to almost every full service airline in

the world today.

But for the LCCs, the late 2008 fuel price reduction was again

disproportionate, this time in their favour, slicing 25% and more off

their bottom line costs. Now become lean again, the opportunity

reignited for them to regain profitability even in the new frugal

consumer environment. The LCCs' ability to offer lower fares, yet

still be profitable, became a virtue where no-one was any longer

prepared to pay five, or even three, times the price for a short haul

journey. Not only was their cost structure made for the new

environment, LCCs could now extend their reach into core full

service airlines as newly cost conscious travellers began exploring

their options.

17

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

These contrasts of recent months pointedly illustrate the

importance of these very different cost/revenue models.

Premium passengers may not return

Within Europe travel on premium tickets declined even

more in June at a rate of 31.3%, compared with a 30.6%

decline in May and a 24.2% fall in the first quarter. Economy

travel on this market is moving is the opposite direction with

a moderation in the recent decline to 3% in June, after 4.9%

in May and a 7% decline in the first quarter. The

deterioration in premium travel is despite the better

economic news declared by Germany and France. There

are lags in any cyclical recovery but on this short/medium-

haul market this does suggest some further structural

decline in premium travel. Passengers who had previously

paid premium fares to travel on these markets and have

now moved to the back of the aircraft, or onto low fare

airlines, may not return, IATA, 19-Aug-2009.

Consequently, for the time being at least, the momentum is with

LCCs. That is unlikely to change, as business travellers irreversibly

trade down on short haul trips and as LCCs move into international

markets.

The current equation will at least endure long enough to reshape an

entire industry, FSC and LCC alike. When we emerge from this

economic downturn, the airline profile will be squarely redefined. It

may even evolve sufficiently to lay down a model which is overall

financially sustainable - but that remains far from certain.

1.3 Old airlines dying of sclerosis, new

entrants sprouting

So how indeed did we arrive in this parlous state of affairs, where

only a handful of airlines can be profitable?

Low cost carriers have been around in one form or another for a

long time. However, occasional attempts like Freddie Lakers trans-

Atlantic Skytrain and PEOPLExpress of the 1970s and 80s were

swept away by the seemingly relentless growth of national carriers

and international majors as the full service, network airline shaped

the aviation world in the second half of the 20th century, carrying

with it powerful connotations of a public utility operation.

In shaping the aviation world, todays legacy airlines also played a

significant part in shaping the geo-political world. They linked the

worlds capitals through their networks, alliances, and interlining,

drawing nations together. They tied exotic resort destinations to the

income and consumption centres of Europe, North America and Asia

Pacific. They enabled business people to move quickly between

producers and markets, fostering the globalisation of production,

services and consumption. Within North America and Europe, in

particular, increasing domestic and regional air networks

alongside a parallel explosion in communications brought together

disparate regions and broke down differences among cultures.

While they were helping to shape the world in this way, the airlines

themselves were operating at the high risk end of demand. They

got fat and unhealthy. They became major corporations, but made

only minor profits. Some government owned airlines operated for

decades without ever coming close to profitability.

18

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

Passenger numbers trended well ahead of GDP, but as markets

grew airlines were buffeted by edgy, price sensitive demand, and

constrained by regulatory limits on where they could go. A heavily

regulated environment, driven by safety, sovereignty and security

concerns and not a little nationalism was reflected in rigid

internal structures. Add to this the high capital costs of aircraft and

the high overheads associated with expansion, the complications of

developing secondary feed routes spokes to the airlines hub

and the expectations of a highly skilled - and unionised - labour

force across a complex array of disciplines, and the result was a

business model offering only indifferent returns and struggling to

remain viable by the end of the 20

th

century.

Over the past ten years airlines have become more exposed as

public ownership and protection became more difficult to justify and

sustain. And the prevailing business model has been buffeted

during the most volatile decade for the aviation industry since the

Second World War. A 50-year history of uneven but more or less

continuous growth was dislocated by unexpected and continuing

financial, security, health and fuel price shocks which collectively

shook conventional airline businesses to the core. It had become an

industry that was inherently fragile and, underneath, supported in

one way or another by a twisted framework of regulation.

As the supporting structure has been progressively (and unevenly)

removed, there have been fewer places to hide when events turned

hostile. The US domestic market has been fully deregulated since

the late 1970s, but the distortions of Chapter 11 bankruptcy laws,

allowing failed airlines protection from creditors, performed a

largely similar distortive and ultimately unhelpful regulatory role in

weakening that industry, too. Today, as a world airline force, the

US domestic market is apparently in irrevocable decline.

Meanwhile, in Europe, protectionism and government subsidy had

prevailed well into the 1990s. The internal market was turned on its

head in the latter half of that decade, as the European Commission

applied its powers to remove national entry restrictions. But it was

not until the current decade that the genre became significant.

Numerically, these two regions still dominate the global LCC market

as they do the full service sector although that supremacy is to

be challenged as the new decade rolls out. As Asias economies

surge and liberalisation spreads through the region, the balance will

rapidly shift.

But still, the awkward relationship between nationalism, regulation

and market demand persists. Consolidation is often suggested as

the essential progression but this is not just around the corner, no

matter how necessary it might be. So the hopes of a brighter

financial future may not be justified quite yet.

New entrants continue to be launched, despite challenging

economic environment

Global LCC Outlook Report 2009

Chapter 2

LCCs account for all

global passenger growth

since 2001

20

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

2 LCCs account for all

global passenger growth

since 2001

Given the traditional dominance of a relatively small number of

international airlines and national flag carriers, the impact of new

entrants has been as surprising as it has been swift. The number of

seats flown worldwide in May 2009 was 298 million, up 18% from

234 million in 2001 (although it peaked at 307 million in May

2008)

1

.

On this count (seats flown), the capacity of network carriers

actually fell slightly over this period. Consequently, the overall

global capacity growth between 2001 and 2009 was entirely

attributable to LCCs.

This is the more remarkable because the changing of the guard has

occurred during perhaps the most powerful five years of economic

growth in recent history conditions which should have been

particularly favourable for those airlines which receive most of the

benefits of corporate well-being. When the current economic cycle

is done, the contrast will be even starker.

Between 2001 and 2009, LCCs grew from 7.7% of the total to 22%

(66 million seats) at compound annual growth rate of 16%.

Expansion of Worldwide Aviation Capacity (seats): May-2001 to

May-2009

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

S

e

a

ts

(

M

illio

n

s

)

NetworkCarriers

Low CostCarriers

Source: OAG and Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation

The nature of LCC operation is typically point-to-point, short haul,

so that a comparable measure of available seat kilometres flown

(ASKs) weights this measure towards the long haul profiles of full

service carrier capacity. Nonetheless, this shift in emphasis is

remarkable for its rapidity.

Today, as we remain embedded in the worst global recession for

decades, the opportunity arises for the first time to test the two

models against prolonged adverse conditions. Temporarily high fuel

costs in mid-2008 nearly brought many low cost carriers to their

knees and did end the lives of some of the more marginal players

where they were unable to compensate for increased costs by

accessing higher yielding traffic.

1

OAG capacity data

21

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

But, since then, the current downturn has been perhaps most

notable for the destruction of premium traffic. One consequence is

that the low price end of the market becomes the battlefield.

Under these conditions, how far will aviation growth continue to

depend on LCCs. Can the LCC model as we know it continue to

deliver in turbulent times?

Throughout however, the number of people who travel globally has

grown, faithfully tracking a long term growth path from 1.47 billion

passengers in 1998 to 2.29 billion in 2008, according to ICAO

(although a 3.8% reduction is expected in 2009), despite

aberrations following September 11, 2001 and the SARS impact in

2003.

Worldwide passenger numbers (millions): 1998 to 2008

Source: Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation & ICAO

w

w

w

.

a

a

l

.

c

o

m

.

a

u

A tell

-

tail

sign of success

As the capital city of South Australia, Adelaide enjoys sandy beaches, parklands, cosmopolitan cafes

and some of the worlds best winemaking regions such as the Barossa Valley.

Adelaide Airport features modern multi-user integrated facilities and excellent weather

characteristics. Thats why weve been able to attract more domestic and

international airlines ying to more destinations than ever before.

We have available slots for international trafc to grow our network

of non-stop connections to major international hubs.

23

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

2.1 Two distinctive facets to growth

First, most of the growth has been on ai rlines that were

barel y heard of or did not exist ten years ago.

It has been the LCC sector that has given new life to an ageing

industry, providing for progress during a period of unprecedented

industry turbulence.

but at the expense of the incumbents?

An alternative interpretation is that the expansion of LCCs/new

entrants generally has diverted traffic from the incumbents. Some

would argue the extreme position that this is actually the main

source of business of the new breed. But there is clear evidence

that lower fares have stimulated additional traffic, especially in

developing markets. Low fares have not been the exclusive domain

of LCCs, but prices did dip sharply once they arrived in a market.

A 2006 study in the UK produced some relatively controversial

findings in this regard. In a report entitled No-frills carriers:

Revolution or Evolution?

2

the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA)

examined the impact that no-frills airlines had had on the airline

market, on passengers and on society more widely.

It concluded that no-frills airlines have revolutionised the short-

haul airline market, radically changing the fares on offer, and the

choice of airlines, airports and destinations available to

passengers. As a result, other airlines now ran their businesses

differently as a result of the advent of no-frills airlines.

But, less predictably, the report also concluded, contrary to

commonly held views that:

1. No-frills airlines appear to have had little impact on

overall rates of traffic growth; the average annual rate of

growth of short-haul traffic had been similar to that before

the arrival of no-frills airlines. In other words, most of the

no-frills airlines growth seems to have been at the

expense of other carriers; and

2. There had been little evidence of any marked change to

the income and socio-economic profile of air passengers.

Although the number of leisure passengers from all income

groups increased, the majority of this increase came from

middle and higher income and socio-economic groups.

2

UK Civil Aviation Authority, 15-Nov-2006.

24

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

Income profiles of UK business and leisure passengers (UK -

EU), departing from surveyed London airports (Heathrow,

Stansted, Gatwick and Luton): 1996 and 2005

Source: UK CAA, 2006

The report concerned only UK operations and arguably may reach

different conclusions if repeated today.

A feature critical to the CAA reports wider relevance - or not - for

other parts of the world is one very special feature of the European

aviation market: charters. This sector of the market, which

slipped under the radar of European restrictions on scheduled air

services, had for many years been carrying a third to a half of all air

travellers.

UK to EU and UK domestic traffic- combined growth 1976-2005

Source: UK CAA

But the report also noted the impact on business travel, where the

finding was somewhat different: There has been a more significant

impact on business passengers.

Parti cular benefits for SMEs

The report noted, they have a lower income profile overall now

than ten years ago. The availability of lower fares to and from more

destinations (and in particular the removal of fare restrictions) has

made trips on a range of airlines more viable for lower income

business passengers, particularly from the UK regions. This change

seems to be linked directly to the effect no-frills airlines have had

on the market.

25

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

The economic impact of these movements for regional development

must have been highly significant, not only in delivering tourists,

but in facilitating business links (two features which often go hand

in hand in international route development) although there does

not appear to have been any holistic study of this element.

There are also unaccounted benefits from an airport infrastructure

development aspect. Had these additional services operated into

the usual hubs, massive new development would have been

necessary. There will have been enormous, but hard to quantify,

financial (and environmental) savings through more effective use of

otherwise under-utilised regional airports, many of which were

previously disused military strips.

Overall, it is quite possible that the LCCs in fact reinvigorated a

mature market subject with declining rates of growth.

Secondl y, most of the expansion has been on new

routes and newer markets

Meanwhile, much of the global growth over this period, said the

CAA, had been on new routes and in developing nations. There was

a changing of the guard well under way.

Analysis of world air travel during the period 2000-2008

demonstrates that, while North Atlantic nations still dominate,

growth has been shifting the focus to Asia, first Northeast and then

Southeast Asia, and now China and India. The Middle East has also

become a major player, and Central and South America may be

expected to do so over the next decade.

Throughout the developing world, with the exception of China, the

LCC has been the catalyst for growth, particularly in domestic and

regional air travel.

Growth, relative to market size, will be modest in North America

and Europe. Even in these markets, it is likely to continue to

depend on the reshaping of airline operations by the sort of

innovation and fast footwork associated with LCCs.

And, whatever the case in 2006 in the UK, a growing body of global

evidence of substantial market stimulation by new LCC entry

accumulates.

LCCs catal ysing strong regional growth

Where the specific city pair data may get buried in gross data, there

are some remarkable growth figures for many regional airports

around the world many due solely to the entry of LCCs. More than

half of the 60 airports globally to have exhibited more than a

doubling of passenger numbers between 2004 and 2008 have the

130+ LCCs covered in this report to thank.

Ryanair is responsible for pushing eleven of these airports into the

global Top 60, while Wizz Air (3), Kingfisher (including the former

Deccan) (3), Blue Air (2) and Gol (2) have also pushed regional

airports in their home markets onto the list.

26

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

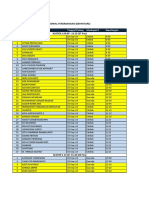

Worlds fastest growing airports (>500,000 pax) between 2004

and 2008 and dominant airlines by capacity share (seats)

Where LCCs are the dominant airline is denoted by bold font

Rank Airport Name Pax -

2004

Pax -

2008

%

growth

2008-

2004

Dominant Airline Capacity

Share of

Dominant

Airline

2 Istanbul, TR 245,601 4,355,717 1,673% Pegasus Airlines 70%

6 Belo Horizonte, BR 446,344 5,036,700 1,028% Gol 48%

9 Subang, MY 93,373 571,476 512% Firefly 94%

14 Wroclaw, PL 343,255 1,478,029 331% Ryanair 52%

15 Cluj, RO 177,862 759,555 327% Wizz Air 48%

16 Katowice, PL 622,612 2,417,754 288% Wizz Air 68%

19 Krakow, PL 813,461 2,923,961 259% Ryanair 31%

20 Riga, LV 1,063,341 3,690,549 247% Air Baltic 68%

22 Moscow, RU 2,489,803 7,923,834 218% Utair Aviation 41%

23 Sharjah, AE 1,661,941 5,280,445 218% Air Arabia 77%

26 Brno, CZ 171,888 506,174 194% Ryanair 36%

27 Zaragoza, ES 209,570 592,920 183% Ryanair 68%

28 Alexandria, EG 410,817 1,102,497 168% EgyptAir 27%

29 Astana, KZ 518,430 1,325,831 156% Air Astana 75%

30 Santander, ES 341,982 856,501 150% Ryanair 62%

31 Hyderabad, IN 2,641,737 6,541,133 148% Deccan/Kingfisher Red 21%

32 Granada, ES 571,081 1,406,869 146% Ryanair 33%

33 Ahmedabad, IN 1,212,871 2,958,669 144% Spicejet 24%

34 Newcastle, AU 459,572 1,110,607 142% Jetstar 65%

37 Eindhoven, NL 697,122 1,629,893 134% Ryanair 66%

38 Guwahati, IN 580,769 1,345,764 132% Deccan/Kingfisher Red 20%

40 Bangalore, IN 4,013,670 9,220,992 130% Deccan/Kingfisher Red 26%

41 Murcia, ES 839,496 1,879,090 124% Ryanair 40%

42 Cochin, IN 1,553,884 3,436,155 121% Jet Airways 15%

43 Bournemouth, GB 494,328 1,088,405 120% Ryanair 68%

44 Timisoara, RO 405,177 889,677 120% Carpatair 45%

45 Banda Aceh, ID 271,731 594,887 119% Lion Air 38%

51 Kiev, UA 3,168,769 6,664,949 110% Aerosvit Airlines 22%

52 Addis Ababa, ET 1,583,383 3,306,836 109% Ethiopian Airlines 78%

53 Amritsar, IN 305,479 636,487 108% Air India 21%

54 Calcutta, IN 3,443,891 7,143,838 107% Indigo Air 23%

55 Vilnius, LT 994,161 2,050,720 106% Air Baltic 31%

56 Cuiaba, BR 695,507 1,433,017 106% Gol 45%

59 Minsk, BY 504,346 1,010,695 100% Belavia 64%

60 Sofia, BG 1,614,326 3,230,696 100% Bulgaria Air 24%

Source: Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation & ACI

And in some very small markets there has often been extreme

percentage growth.

27

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

Worlds fastest growing airports (<500,000 pax) between 2004

and 2008 and dominant airlines by capacity share (seats)

Where LCCs are the dominant airline is denoted by bold font

Rank Airport Name Pax -

2004

Pax -

2008

%

growth

2008-

2004

Dominant Airline Capacity

Share of

Dominant

Airline

1 Arad, RO 1,778 142,951 7,940% Blue Air 100%

3 Targu Mures, RO 4,211 70,312 1,570% Wizz Air 46%

4 Pelotas, BR 679 9,021 1,229% NHT Linhas Aereas 50%

5 Southend, GB 3,673 47,488 1,193% n/a n/a

7 Eldoret, KE 13,613 98,021 620% Jetlink Express 56%

8 Taranto, IT 448 3,139 601% n/a n/a

13 Vinh City, VN 36,352 160,163 341% Vietnam Airlines 68%

10 Saint-Nazaire, FR 2,663 15,056 465% Airlinair 100%

11 Uruguaiana, BR 551 2,785 405% Nht Linhas Aereas 50%

12 Angouleme, FR 5,495 25,555 365% Ryanair 100%

17 Haiphong, VN 80,149 299,903 274% Vietnam Airlines 73%

18 Sibiu, RO 44,611 165,056 270% Blue Air 52%

21 Baia Mare, RO 6,741 22,264 230% Tarom 100%

24 Foggia, IT 9,331 29,502 216% Darwin Airlines 91%

25 Salamanca, ES 19,594 59,779 205% Iberia 100%

35 Maribor, SI 7,083 17,096 141% n/a n/a

36 Nador, MA 89,287 215,045 141% Royal Air Maroc 43%

39 Grenoble, FR 204,068 469,777 130% n/a n/a

46 Fez, MA 188,851 409,271 117% Ryanair 51%

47 Rabat, MA 155,857 334,664 115% Air France 44%

48 Ostend, BE 81,340 173,068 113% Jetairfly 100%

49 Karlovy Vary, CZ 36,327 77,283 113% Czech Airlines 70%

50 Ndola, ZM 80,259 169,793 112% South African Airways 40%

Source: Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation & ACI

These are only the airports where rates have exceeded 100%.

But headline statistics too often do not fully illustrate the impact of

new entry. For example, for Asia Pacifics AirAsia, nearly half of the

city pair routes the LCC operates today did not even have direct

service prior to the carrier's entry. This is commonly the case in

global markets, as new entrants seek to address untapped

opportunities.

Inevitably there has been some displacement of full service airlines,

at least in proportional shares, on larger city pairs and airports, but

low fare responses by those airlines have also contributed to growth

where there is head to head competition.

Global LCC Outlook Report 2009

Chapter 3

(Not) Defning the

Low Cost Carrier

29

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

3 (Not) Defining the Low

Cost Carrier

3.1 Proliferation and diversification

The proliferation of LCCs has been the key structural change in

aviation over the past ten years. The LCC model has been favoured

for airline start-ups, with around 130 new LCCs established and

some 90 surviving since 2000.

Given another 36 that existed before 2000 although not

necessarily initially in the form of LCCs we can identify 126

operating airlines in early 2009 that feature at least several of the

key characteristics identified in the classic model:

High seating density;

High aircraft utilisation;

Single aircraft type;

Low fares, including very low promotional fares;

Predominant usage of internet-based booking;

Single class configuration;

Point-to-point services;

No (free) frills;

Predominantly short- to medium-haul route structures

Frequent use of second tier airports;

Rapid turnaround time at airports.

While some airlines remain pure, the classic model has

increasingly been eroded, and the lines between low cost carriers

and large network and regional carriers blurred as a result.

The strategy and business model of the purist version is best

described by the Tiger Airways description on its website:

Core Business Strategy

Tiger Airways, a true low fare airline, operates on three customer-

focused core strategies:

Market stimulation - creating opportunities for new travellers

and empowering budget-conscious people to fly more often

by making travel affordable with its consistently low fares;

Stringent cost controls through our operations so that we

can keep our fares consistently low for travellers;

Capacity utilisation - maximising the number of sectors

served by our aircraft per day with efficient air traffic

planning.

The Proven Business Model

The Tiger Airways business model is based on Europe's successful

Ryanair, which uses its very low cost base to offer competitively low

fares on a consistent basis. It also involves scrutinising every single

aspect of the business to remove non-essential costs but not cutting

any corners in passenger safety, security and punctuality.

This includes:

Online Internet sales to help keep sales and distribution

costs low. 95% of flights are booked directly at

www.tigerairways.com

Ticketless travel to save on print and distribution of paper

tickets

Removing frills so passengers only pay for what they want.

30

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

Excess luggage, meals and entertainment onboard flights

are all available at affordable prices should passengers

want them

New aircraft provides new technology with greater fuel

efficiency and less maintenance, plus passengers enjoy a

more comfortable ride

Operating at budget terminals and secondary airports to

reduce operating costs

Short aircraft turn-around to keep ground time low and flying

time high. This means more seats can be sold on more

flights for passengers to enjoy more cheap fares

Outsourcing aircraft maintenance to reputable companies

such as Singapore Airlines Engineering Company to ensure

high safety standards are achieved at competitive rates

There is continuing convergence with the operating profile of

network airlines, as they adopt innovations introduced by LCCs, and

of LCCs varying the business model to meet local circumstances, to

pursue higher yields, and in response to increasing low cost

competition. This applies to the majority of airlines. Today there are

in reality few carriers which would qualify as low cost airlines on the

principles of a decade ago.

As noted in Chapter 1, apart from Ryanair, only the Indigo Partners

stable of airlines Tiger, Mandala, Spirit, Wizz Air and Avianova

AirAsia, AirArabia and Indias Indigo, GoAir and SpiceJet and

Allegiant in the US can be described as ultra-low cost.

31

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

3.2 Attributes common to low fare airlines and

low cost carriers

To avoid unhelpful pedantic explorations, this report does not

attempt a definitive description of the term low cost carrier; so

many varieties of airline have emerged since the beginning of this

century, many of them still evolving, that the exercise becomes

fruitless. Meanwhile full service airlines have remodelled to

incorporate some, or even much of the character of their low cost

competitors.

This lack of definition will necessarily leave some of our statistics

and comparisons open to different interpretations and even to

challenges. But the purpose of the report is instead to provide a

reference point in history for the evolution of a movement not

merely one type of airline that has changed the aviation world

irreversibly.

Nonetheless, there are certain characteristics that are self-defining,

most particularly that the airline offers low fares, with no or limited

frills and, of course, operates off a low cost base. These include the

following, some or all of which relate to most so-called LCCs.

Attributes common to low fare airlines and low cost carriers

Attribute Benefits Downside Importance

Strategy

Short haul, point-to-point services

Minimum on-board service;

Build passenger volume through higher

frequencies;

Rapid turnaround improves aircraft

utilisation

Operating costs spread

over shorter distances

High

Underserved airports close to large

population centres

Provides access to substantial under-

served markets;

Avoids congestion, better access to slots;

Minimises direct competition; and

Lower user costs, including landing fees

Longer ground transport;

Limited airport facilities

Reduced connectivity

with other services

High

Target mature, high fare markets,

greater degrees of business travel

elasticity

New passenger take-up of low fares;

Tap into regular business travellers

seeking lower fares (short-haul)

Market may be less price

sensitive;

Limited corporate travel

accounts

High

Operate in liberal regulatory

environment

Limited or no restrictions on entry,

development of services

Open to entry of other

low fare competitors

High

Technology friendly markets with

right demographics

Internet reduces distribution costs;

Younger age groups receptive

Internet users tend to

shop around

Medium

Operate in homogenous cultural

and economic environment

Enhances marketing, customer

acceptance of LCA product

Limits potential market Medium

Strict adherence to business plan

Ensure consistency, limit risks; and

Avoids ad hoc costs and confusing the

market

Could slow response to

change operating

environment

High

Neutral geographic (non-flag)

branding

Consumer (and government) acceptance

of unconfined operational potential

Allows development of global brand

which is at home in any market

No flag carrier

protection

Medium

Service Structure

Differentiated product (alternate

airports, city-pairs)

Limits direct competition;

Marketing benefits in new markets

Higher risk in targeting

untested airports, routes

High

Uncomplicated yield

management/low fare structure,

one way fare pricing, 50% below

standard economy rates, with few

conditions

Highly competitive, transparent pricing

framework;

Facilitates marketing;

Streamlined passenger loading (first come,

first served)

Minimises ability to

manage;

Full service competitors

can match rates (although

limited availability )

High

No frills services

Lower operating costs, quicker aircraft

turnaround

Advantages full service

providers;

Limits to business market

Medium

Highly-motivated airline culture

Assists in differentiating product;

Enhances customer acceptance;

Reduces industrial disputes

Difficult to sustain over

long period

High

High seat density Maximises revenue per flight

Disincentive to

passengers

Medium

32

Global LCC Outlook 2009: The World Has Changed

Attribute Benefits Downside Importance

Operations

Single aircraft and engine type

Reduces maintenance, training &

inventory costs;

Increases employee familiarity with

aircraft

Limits range of services

and routes

High

Operational efficiency (operating

on time, baggage handling, aircraft

utilisation)

Minimises operating overheads;

Reinforces brand image; and

Encourages repeat travellers

High customer

expectations;

Vulnerable to airport

operational problems

High

Outsource non-core activities

(maintenance, ground handling,

catering)

Reduces employee and infrastructure

costs;

Provides for more efficient support

services; and

Allows for innovative third party

arrangements

No direct quality controls;

May be less reliable,

depends on third party

availability

Medium

Productivity-based labour