Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Lymphadenitis in

Загружено:

Abdur Rachman Ba'abdullahИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Lymphadenitis in

Загружено:

Abdur Rachman Ba'abdullahАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

REVIEWS

49

IMAJ VOL 12 JANUARY 2010

Lymphadenitis is the most common manifestation of non-

tuberculous mycobacteria infection in children. Its frequency

has increased over the past few decades. Diagnosis is based

on clinical presentation, puried protein derivative skin test,

and bacterial isolation. Management options are surgery,

antibiotics, or "observation only"; however, the optimal thera-

py for this condition is still controversial.

IMAJ 2010; 12: 4952

non-tuberculous mycobacteria, mycobacteria,

lymphadenitis, children

Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Lymphadenitis in

Children: Diagnosis and Management

Jacob Amir MD

Department of Pediatrics C, Schneider Childrens Medical Center of Israel, Petah Tikva and Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, Israel

ABSTRACT:

KEY WORDS:

N

on-tuberculous mycobacteria are a diverse group of

mycobacterial species that cause a wide range of clinical

infections in children and adults. Tey are environmental

free-living organisms in water (including tap water), soil,

animals and dairy products. Te spectrum of clinical mani-

festations caused by these organisms in immunocompetent

individuals comprises three major categories: lymphadeni-

tis, pulmonary infections, and skin/sof tissue infections.

Lymphadenitis due to NTM strikes mainly young children,

whereas pulmonary and skin/sof tissue infections are com-

mon only in adults, usually afer the third decade [1,2]. Tis

review will focus on the epidemiology, diagnosis and treat-

ment of NTM lymphadenitis.

NTM lymphadenitis typically presents as a swelling of

non-tender cervical/facial lymph nodes, followed by a pur-

plish discoloration of the overlying skin and no systemic

symptoms [2] [Figure 1]. Te most commonly involved

nodes are the submandibular, cervical or preauricular (usu-

ally one or two nodes on the same side) [3-5]. Te disease

usually afects children between the ages of 1 and 5 years;

the median age is approximately 3 years, and it rarely pres-

ents afer age 12 [3-7]. Tis age distribution may refect an

acquired natural immunity to NTM or maturation of the

innate immune system.

Te estimated annual incidence of NTM lymphadeni-

tis in children is 1.21 cases per 100,000 and > 3 cases per

100,000 in children aged 04 years [7,8]. Since the 1990s, the

annual number of afected children started to increase and

continued climbing into the following decade [6,8-10]. Te

reason for this increase is unclear, although some research-

ers link these phenomena to the discontinuation of the BCG

(Bacillus Calmette-Gurin) vaccination in developed coun-

tries [2,11,12]. Te BCG vaccine provides protection against

various NTM species; this has also been demonstrated in

animal models [13].

Te NTM species involved in pediatric lymphadenitis has

changed over the last 50 years. Mycobacterium scrofulaceum

was the most common cause in the 1970s [3], replaced by M.

avium-intracellulare complex, which is now found in approxi-

mately 80% of cases [2]. However, in two recent studies, M.

haemophilum was recognized as an important pathogen in

children with NTM adenitis, and was isolated in 2451%

of cases with positive cultures [14,15]. Te reason for the

emergence of M. haemophilum as an important pathogen in

immunocompetent children is probably related to improved

laboratory processing procedures [16]. Many other species of

NTM = non-tuberculous mycobacteria

BCG = Bacillus Calmette-Gurin

Figure 1. A child with non-tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis

REVIEWS

50

IMAJ VOL 12 JANUARY 2010

Species

% of positive

isolates References

Mycobacterium avium complex 5580 [4,5,14]

M. haemophilum 2451 [14,15]

M. scrofulaceum < 10 [5]

M. simiae < 10 [5]

M. gordonae < 10 [5]

M. chelonae < 10 [5,14]

M. fortuitum < 10 [14]

M. kansasii < 10 [14]

M. malmoense < 10 [14]

M. triplex <10 [17]

NTM are isolated in small numbers [Table 1], and new strains

continue to be identifed as technology improves [17].

DIAGNOSIS

Te diferential diagnosis of chronic cervical lymphadenopathy

presents a diagnostic challenge to pediatricians. Diagnosing

NTM adenitis is determined by clinical presentation, tubercu-

lin skin test (purifed protein derivative), mycobacterial culture

and, to a lesser extent, histology and imaging.

Children with NTM lymphadenitis usually present with

painless unilateral cervical or facial (preauricular or cheek)

swelling. Te overlying skin is normal or has a purplish dis-

coloration, whereas an undiagnosed longstanding disease

may ulcerate with spontaneous drainage. In most children

the disease presents afer a therapeutic trial of anti-staphylo-

coccal and anti-streptococcal antibiotics.

Te PPD skin test is a practical and valuable tool for the

early diagnosis of NTM adenitis, although controversy exists

regarding interpretation of the results. Recommendations

based on literature of the 1980s

consider PPD 15 mm indura-

tions to be more indicative of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis,

with a reaction of 59 mm

more likely to indicate an NTM infection [18]. More recent

studies have shown that a PPD of 15 mm and 10 mm are

more common in children with NTM adenitis, 1359% and

5576%, respectively [10,19,20]. Skin tests with NTM-purifed

proteins are no longer produced commercially; consequently,

the standard MTB-PPD remains the only available skin test.

Te reported variable reaction to the skin test may refect

PPD = puried protein derivative

MTB = Mycobacterium tuberculosis

regional diferences in the species cell wall structure and,

accordingly, immunogenicity, or genetic variations that inter-

fere with the skin response [21]. Te main issue regarding PPD

interpretation is the probability of MTB infection. Although

NTM are the main cause of mycobacterial adenitis, when

relying only on the skin test for diagnosis and management

certain conditions need to be present, such as a low prevalence

of tuberculosis, no exposure to adults with TB, and normal

chest radiograph. Te new assays, based on measurement of

the release of interferon-gamma in whole blood or mononu-

clear cells afer in vitro stimulation with specifc MTB antigens,

may enable us to diferentiate between NTM and MTB infec-

tion [22].

Isolation and identifcation of the NTM causing the

lymphadenitis is the defnitive diagnosis, although it needs an

invasive procedure such as fne needle aspiration, incision or

excisional biopsy. However, the fnal results may take up to 6

weeks. Te yield of FNA cultures has improved recently and

positive FNA cultures of 6480% have been reported in some

clinical laboratories [5,14], a much higher rate than in previ-

ous reports [23,24]. Changing the sequence of handling these

specimens, use of Gen-probes and real-time polymerase chain

reaction, and better-defned growth requirements for fastidi-

ous Mycobacteria such as M. haemophilum [16] are the main

reasons for the improved isolation rate. Routine use of PCR for

rapid results is usually not available in many medical centers.

Tissue histology is used to rule out malignancy in children

with lymphadenopathy. Although necrotizing granulomatous

lymphadenitis or purulent material was found in most cases,

attempts were made to diferentiate between lymphadeni-

tis caused by NTM or by MTB. Te results have not been

encouraging [25].

Imaging is frequently used to evaluate children with neck

swelling. Chest X-ray is performed to rule out pulmonary

tuberculosis. Sonographic fndings in children with NTM

lymphadenitis led to a decrease of echogenicity in early stages

of the infection and intranodal liquefaction in advanced stages;

however, it is not entirely spe-

cifc [26]. Te appearance of

NTM lymphadenitis in com-

puted tomography and mag-

netic resonance imaging were

reported to be typical, characterized by an asymmetric cervical

lymphadenopathy with minimal infammatory stranding of the

subcutaneous fat, and lack of surrounding infammation [27].

However, extensive infammatory reaction in the fat tissue

was also reported in patients with NTM adenitis, and similar

fndings may be seen in other diseases such as lymphoma or

metastatic lymphadenopathy [28,29]. In our experience, imag-

FNA = ne needle aspiration

PCR = polymerase chain reaction

M. haemophilum was recognized as an

important pathogen in children with NTM

adenitis, and is isolated in 24%51% of

cases with positive cultures

Table 1. Isolated non-tuberculous mycobacteria species taken

from children with lymphadenitis during the last 10 years

REVIEWS

51

IMAJ VOL 12 JANUARY 2010

comparing surgical excision and medical treatment was pub-

lished [36]. Surgical excision was found to be more efective than

antibiotic therapy with clarithromycin and rifabutin, the cure

rate being 96% compared to 66%, respectively. Nevertheless,

surgical complications were reported in 28% of the children as

compared to adverse efects to the antibiotic in 78%.

OBSERVATION-ONLY

Only a few cases of observation-only in children with NTM

lymphadenitis have been reported [39,40]. A recently published

study described the natural history of cervical NTM lymph-

adenitis in 92 immunocompetent children [5]. In all cases, the

NTM organism was isolated using FNA as the main diagnostic

procedure. In most cases, the skin

over afected lymph nodes under-

went violaceous changes with

discharge of purulent material for

38 weeks. Total resolution was achieved within 6 months in

71% of the patients, and within 912 months in the remainder.

No complications were observed, and at 2 years follow-up a

skin-colored fat scar in the region of the drainage was noted.

Te healing time in these observation-only patients afer

6 months was similar to the antibiotic therapy group from the

Netherlands' CHIMED trial, 71% and 66%, respectively [36],

taking into account that the endpoint results at 3 months

were from the time of antibiotic initiation, about 3 months

afer the swelling of the lymph nodes had begun [36].

Te defnition of successful treatment in a self-limited con-

dition like NTM lymphadenitis is not straightforward. While it is

clear that lymphadenitis in normal hosts will eventually heal as

shown above [5], the main factors ensuring success are parental

tolerance to a prolonged healing

process, cosmetic outcome, compli-

cations, and cost. Table 2 presents

the reasons for and against surgical excision and spontaneous

healing. Te optimal way to manage this disease is still unclear.

ing of the cervical swelling plays a small role in diagnosing or

managing NTM adenitis.

TREATMENT

Te management of cervical lymphadenitis caused by NTM

is controversial due to the lack of randomized controlled

studies. Tere are three main options: surgical, medical

management, and observational.

SURGERY

For the past 20 years, complete excision of the infected lymph

node has been considered the optimal therapy by most research-

ers [2,3,8,9,30]. Tis recommenda-

tion was not based on controlled

trials but was the preferred choice

for several reasons: a) surgical

intervention is necessary to obtain tissue for diagnosis; b) the

rate of complete cure with good cosmetic outcome is high, if

surgery is performed early; and c) surgery avoids the toxicity

and cost of long-term anti-mycobacterial treatment.

Incision and drainage are performed when the lesions are

too large to be excised, concerns about facial nerve damage

are raised, or when NTM adenitis is considered unlikely. For

similar reasons, incision and partial curettage are performed.

Few retrospective case series have demonstrated the superior-

ity of complete excision over incision and drainage [30-34]. A

cure rate of about 90% was reported with excision compared

to < 20% post-incision and drainage [35].

Te main side efects of complete excision are unac-

ceptable scarring with or without keloid formation, wound

breakdown, secondary staphy-

lococcal infection, and facial

nerve paresis. Most facial nerve

damage is transient and only in about 2% was permanent

palsy reported [32,36]. Te procedure is performed under

general anesthesia. For extensively involved nodes, surgery

ofen takes a few hours. Most children stay 14 days in the

hospital. Reoperation is needed in only 620% of the cases

[4,10,24,36]. On the other hand, in most children who under-

went incision and drainage only, another surgical procedure

was necessary, usually excision [10,24,31].

MEDICAL TREATMENT

Pharmacological therapy with clarithromycin, alone or com-

bined with other anti-mycobacterial agents, such as rifampicin,

rifabutin or ethanbutol, have been reported [review in 24].

Anecdotal case reports and small series have reported variable

therapeutic efects of chemotherapy alone or in combination

with surgery and chemotherapy [4,37,38]. However, there are no

controlled clinical trials showing the efcacy of chemotherapy

versus placebo. Recently, the only randomized controlled study

There are three main options for

managing cervical NTM adenitis:

surgical, medical and observation

The optimal therapy for this condition

is still controversial

Surgical excision Observation

Healing time Short (wks) Long (mos)

Suitable for all cases No (only early diagnosed cases) Yes

Complications [36] Yes (28%) No

Long-term

sequelae [32,36]

Yes (VII nerve palsy) No

Scar quality Variable Variable

Hospitalization Yes No

General anesthesia Yes No

Cost High Low

Table 2. Comparison between two therapeutic modalities of NTM

lymphadenitis in children: complete surgical excision versus

observation only

REVIEWS

52

IMAJ VOL 12 JANUARY 2010

Samara Z, Kaufman L, Zeharia, A et al. Optimal detection and identifcation 16.

of Mycobacterium haemophilum in specimens from pediatric patients with

cervical lymphadenopathy. J Clin Microbiol 1999; 37: 832-4.

Hazra R, Floyd MM, Sloutsky A, Husson RN. Novel mycobacterium related 17.

to Mycobacterium triplex as a cause of cervical lymphadenitis. J Clin Microbiol

2001; 39: 1227-30.

Starke JR, Correa AG. Management of mycobacterial infection and disease in 18.

children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1995; 14: 455-69.

Haimi-Cohen Y, Zeharia A, Mimouni M, Soukhman M, Amir J. Skin 19.

indurations in response to tuberculin testing in patients with nontuberculous

mycobacterial lymphadenitis. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33: 1786-8.

Lindeboom JA, Kuijper EJ, Prins JM, Brunestejn van Coppenraet 20.

ES, Lindeboom R. Tuberculin skin testing is useful in screening for

nontuberculous mycobacterial cervicofacial lymphadenitis in children. Clin

Infect Dis 2006; 43: 1547-51.

Van Eden W, De Vries RR, Stanford I, Rook GA. HLA-DR3-associated 21.

genetic control of response to multiple skin tests with new tuberculin. Clin

Exp Immunol 1983; 52: 287-92.

Manuel O, Kumar D. QuantiFERON-TB GOLD assay for the diagnosis of 22.

latent tuberculosis infection. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2008; 8: 247-55.

Margileth AM, Chandra R, Altman RP. Chronic lymphadenopathy due to 23.

mycobacterial infection: clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology and

management. Am J Dis Child 1984; 138: 917-22.

Starke JR. Management of nontuberculous mycobacterial cervical adenitis. 24.

Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000; 19: 674-6,

Kraus M, Benharroch D, Kaplan D, et al. Mycobacterial cervical 25.

lymphadenitis: the histological features of non-tuberculous mycobacterial

infection. Histopathology 1999; 35: 534-8.

Lindeboom JA, Smets AMJB, Kuijper EJ, van Rijn RR, Prins JM. Te 26.

sonographic characteristics of nontuberculous mycobacterial cervicofacial

lymphadenitis in children. Pediatr Radiol 2006; 36: 1063-7.

Robson CD, Hazra R, Barnes PD, Robertson RL, Jones D, Hussen RN. 27.

Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection of the head and neck in immun-

ocompetent children: CT and MR fnding. Am J Neuroradiol 1999; 20: 1829-35.

Nadel DM, Bilaniuk L, Handler SD. Imaging of granulomatous neck masses 28.

in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1996; 37: 151-62.

Hanck C, Fleisch F, Katz G. Imaging appearance of nontuberculous myco- 29.

bacterial infection of the neck [Letter]. Am J Neuroradiol 2004; 25: 349-50.

Saggese D, Compadretti GC, Burnelli R. Nontuberculous mycobacterial adenitis 30.

in children: diagnostic and therapeutic management. Am J Otolaryngol 2003; 24:

79-84.

Stewart MG, Starke JR, Coker NJ. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections 31.

of head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994; 120: 873-6.

Fergusson JA, Simpson E. Surgical treatment of atypical mycobacterial 32.

cervicofacial adenitis in children. Aust NZ J Surg 1999; 69: 426-9.

Rahal A, Abela A, Arcand PH, Quintal MC, Lebel MH, Tapiero FB. 33.

Nontuberculous mycobacterial adenitis of the head and neck in children

from a tertiary pediatric center. Laryngoscope 2001; 111: 1791-6.

Panesar J, Higgins K, Daya H, Forte V, Allen U. Nontuberculous mycobacterial 34.

cervical adenitis: a ten-year retrospective review. Laryngoscope 2003; 113: 149-54.

American Toracic Society. Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by 35.

nontuberculous mycobacteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 156: S1-25.

Lindeboom JA, Kuijper EJ, Brunestejn van Coppenraet ES, Lindeboom R. 36.

Prins JM. Surgical excision versus antibiotic treatment for nontuberculous

mycobacterial cervicofacial lymphadenitis in children: a multicenter,

randomized, controlled trail. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44: 1057-64.

Tessier MH, Amoric JC, Mechinhaud F, Dubesset D, Litoux P, Stalder JF. 37.

Clarithromycin for atypical mycobacterial lymphadenitis in nonimmuno-

compromised children. Lancet 1994; 344: 1778.

Berger C, Pfyfer GE, Nadal D. Treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial 38.

lymphadenitis with clarithromycin plus rifabutin. J Pediatr 1996; 128: 383-6.

Flint D, Mahadevan M, Barber C, Grayson D, Small R. Cervical lymphadenitis 39.

due to non-tuberculous mycobacteria: surgical treatment and review. Int J

Pediatr Otolaryngol 2000; 53: 187-94.

Mandell DL, Wald ER, Michaels MG, Dohar JE. Management of non- 40.

tuberculous mycobacterial cervical lymphadenitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head

Neck Surg 2003; 129: 341-4.

In conclusion, NTM adenitis is a common cause of neck

swelling in children. Te diagnosis is based on clinical pre-

sentation, PPD skin test and FNA culture. In countries with a

low rate of MTB, most cases of mycobacterial lymphadenitis

are caused by NTM. Te optimal therapy for this condition

is still controversial. However it seems that antibiotics are

not efective in treating immunocompetent children. A ran-

domized, controlled trial examining surgical excision versus

spontaneous healing is warranted.

Acknowledgment:

Te author wishes to thank Phyllis Curchack Kornspan for her edito-

rial and secretarial services.

Correspondence:

Dr. J. Amir

Dept. of Pediatrics C, Schneider Childrens Medical Center of Israel, Petah

Tikwa 49202, Israel

Phone: (972-3) 925-3775, Fax: (972-3) 925-3801

email: amirj@clalit.org.il

References

OBrien DP, Currie BJ, Krause VL. Nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in 1.

northern Australia: a case series and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis

2000; 31: 958-68.

Grifth DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliot BA, et al. American Toracic Society: 2.

diagnosis, treatment and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial

diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175: 367-416.

Wolinsky E. Mycobacterial lymphadenitis in children: a prospective study of 3.

105 nontuberculous cases with long-term follow-up. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 20:

954-63.

Hazra R, Robson CD, Perez-Atayde AR, Husson RN. Lymphadenitis due 4.

to nontuberculous mycobacteria in children: presentation and response to

therapy. Clin Infect Dis 1999; 28: 123-9.

Zacharia A, Eidliz-Markus T, Haimi-Cohen S, Samra Z, Kaufman L, 5.

Amir J. Management of nontuberculous mycobacteria-induced cervical

lymphadenitis with observation alone. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008; 27: 920-2.

Grange JM, Yates MD, Poznaik A. Bacteriologically confrmed non- 6.

tuberculous mycobacterial lymphadenitis in south east England: a recent

increase in number of cases. Arch Dis Child 1995; 72: 516-17.

Haverkamp MH, Arend SM, Lindeboom JA, Hartwig NG, van Dissel JT. 7.

Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in children: a 2-year prospective

surveillance study in the Netherlands. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39: 450-6.

Sigalet D. Lees G, Fanning A. Atypical tuberculosis in the pediatric patient: 8.

implications for the pediatric surgeon. J Pediatr Surg 1992; 27: 1381-4.

Maltezou HC, Spyridis P, Kafetzis DA. Nontuberculous mycobacterial 9.

lyphadenitis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1999; 18: 968-70.

Vu TT, Daniel SJ, Quach C. Nontuberclous mycobacteria in children: a 10.

changing pattern. J Otolaryngol 2005; 34: Suppl 1.

Trnka L, Dnkov D, Svandov E. Six years experience with the discontinuation 11.

of BCG vaccination. 4. Prospective efect of BCG vaccination against

Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex. Tuber Lung Dis 1994; 75: 348-52.

Romanus V, Hallander HO, Whln P, Olinder-Nielsen AM, Magnusson PH, 12.

Juhlin I. Atypical mycobacteria in extrapulmonary disease among children.

Incidence in Sweden from 1969 to 1990, related to changing BCG-vaccination

coverage. Tuber Lung Dis 1995; 76: 300-10.

Orme IM, Collins FM. Prophylactic efect in mice of BCG vaccination against 13.

nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Tubercle 1985; 66: 117-20.

Lindeboom JA, Prins JM, Brunestejn van Coppenraet ES, Lindeboom R, 14.

Kuijper E. Cervical lymphadenitis in children caused by Mycobacterium

haemophilum. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41: 1569-75.

Haimi-Cohen Y, Amir J, Ashkenazi S, et al. 15. Mycobacterium haemophilum and

lymphadenitis in immunocompetent children, Israel. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;

14: 1437-9.

Вам также может понравиться

- Community Medicine OspeДокумент4 страницыCommunity Medicine OspeHammad Shafi100% (1)

- Biology Project On TBДокумент20 страницBiology Project On TBAdnan Fazeel73% (15)

- Public Health Questions and Answers For StudentsДокумент22 страницыPublic Health Questions and Answers For StudentsKen Sharma100% (1)

- Nontüberküloz Lenf AdenitДокумент7 страницNontüberküloz Lenf AdenitDogukan DemirОценок пока нет

- Extrapulmonary Infections Associated With Nontuberculous Mycobacteria in Immunocompetent PersonsДокумент9 страницExtrapulmonary Infections Associated With Nontuberculous Mycobacteria in Immunocompetent Personsrajesh Kumar dixitОценок пока нет

- Diagnosing Childhood Tuberculosis: Traditional and Innovative ModalitiesДокумент28 страницDiagnosing Childhood Tuberculosis: Traditional and Innovative ModalitiesSentotОценок пока нет

- TB MeningitisДокумент10 страницTB Meningitisrizky ramadhanОценок пока нет

- Etiologi-Clamydia TrachomatisДокумент14 страницEtiologi-Clamydia Trachomatisavely NathessaОценок пока нет

- Antibiotic Coated Shunt ManuscriptДокумент6 страницAntibiotic Coated Shunt ManuscriptBilal ErtugrulОценок пока нет

- Laboratory Diagnosis of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection and Disease in ChildrenДокумент8 страницLaboratory Diagnosis of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection and Disease in ChildrenFaradilla FirdausaОценок пока нет

- Clinico-Epidemiological Profile of Childhood Cutaneous TuberculosisДокумент7 страницClinico-Epidemiological Profile of Childhood Cutaneous TuberculosisFajar SatriaОценок пока нет

- Journal TB Kulit PDFДокумент4 страницыJournal TB Kulit PDFdrmarhuОценок пока нет

- Pneumonia Caused by Chlamydia Pneumoniae in ChildrenДокумент19 страницPneumonia Caused by Chlamydia Pneumoniae in Childrenmayteveronica1000Оценок пока нет

- 1 BavejaДокумент9 страниц1 BavejaIJAMОценок пока нет

- Diagnosis and Therapy of Tuberculous Meningitis in ChildrenДокумент7 страницDiagnosis and Therapy of Tuberculous Meningitis in ChildrenRajabSaputraОценок пока нет

- Tuberculosis in ChildrenДокумент4 страницыTuberculosis in ChildrenMarthin TheservantОценок пока нет

- 7Документ7 страниц779lalalaОценок пока нет

- Reduced Lung Diffusion Capacity After Mycoplasma Pneumoniae PneumoniaДокумент5 страницReduced Lung Diffusion Capacity After Mycoplasma Pneumoniae Pneumoniawawa chenОценок пока нет

- GR 0420 041Документ1 страницаGR 0420 041kafosidОценок пока нет

- Bacterial Meningitis 18Документ3 страницыBacterial Meningitis 18caliptra36Оценок пока нет

- Recent Innovations in Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric TuberculosisДокумент8 страницRecent Innovations in Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric TuberculosisDannyLagosОценок пока нет

- Clamidia TrachomatisДокумент13 страницClamidia TrachomatisAnisha PutryОценок пока нет

- International Journal of Pediatric OtorhinolaryngologyДокумент7 страницInternational Journal of Pediatric OtorhinolaryngologyAndi SuhriyanaОценок пока нет

- Congenital Cytomegalovirus-HistoryДокумент6 страницCongenital Cytomegalovirus-Historydossantoselaine212Оценок пока нет

- Vervloet Et Al-2007-Brazilian Journal of Infectious DiseasesДокумент8 страницVervloet Et Al-2007-Brazilian Journal of Infectious DiseasesCynthia GalloОценок пока нет

- DiagnosisofpulmonaryTB in ChildrenДокумент8 страницDiagnosisofpulmonaryTB in ChildrenSumit MitraОценок пока нет

- Immunology of Chlamydia InfectionДокумент13 страницImmunology of Chlamydia InfectionTrinh TrươngОценок пока нет

- Daftar Pustaka No 6Документ11 страницDaftar Pustaka No 6Efti WeaslyОценок пока нет

- Bab I Pendahuluan Tuberculous Meningitis: Diagnosis and Treatment OverviewДокумент14 страницBab I Pendahuluan Tuberculous Meningitis: Diagnosis and Treatment OverviewInalОценок пока нет

- Research Paper On Mycobacterium TuberculosisДокумент7 страницResearch Paper On Mycobacterium Tuberculosisgqsrcuplg100% (1)

- Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Current Strategies and Future PerspectivesДокумент17 страницCongenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Current Strategies and Future PerspectivesAfif AriyanwarОценок пока нет

- Tugas Jurnal TBДокумент6 страницTugas Jurnal TBMedica HerzegovianОценок пока нет

- TB in Children: EpidemiologyДокумент13 страницTB in Children: EpidemiologyAdel HamadaОценок пока нет

- SkrofulodermaДокумент4 страницыSkrofulodermabangunazhariyusufОценок пока нет

- Tuberculous Meningitis: Neurological Aspects of Tropical DiseaseДокумент12 страницTuberculous Meningitis: Neurological Aspects of Tropical DiseaseBayuHernawanRahmatMuhariaОценок пока нет

- NXJDBSKHDДокумент4 страницыNXJDBSKHDMonika ZikraОценок пока нет

- FullДокумент17 страницFullambiebieОценок пока нет

- Prevalence of Anti-Cytomegalovirus Anticorps in Children at The Chantal Biya Foundation Mother Child Centre, CameroonДокумент6 страницPrevalence of Anti-Cytomegalovirus Anticorps in Children at The Chantal Biya Foundation Mother Child Centre, CameroonInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- Tuberculosis: An Approach To A Child WithДокумент25 страницTuberculosis: An Approach To A Child WithMateen ShukriОценок пока нет

- Evidence 3) Congenital Infection Causes Neurologic and Hematologic Damage andДокумент5 страницEvidence 3) Congenital Infection Causes Neurologic and Hematologic Damage andandamar0290Оценок пока нет

- Preventing Sexually Transmitted Infections: Back To Basics: Review Series IntroductionДокумент4 страницыPreventing Sexually Transmitted Infections: Back To Basics: Review Series Introductionursula_ursulaОценок пока нет

- IndianJMedRes1523185-2140176 055641Документ42 страницыIndianJMedRes1523185-2140176 055641irfanОценок пока нет

- Jurnal RadiologiДокумент9 страницJurnal RadiologiAndrean HeryantoОценок пока нет

- Mycobacterium Tuberculosis ThesisДокумент5 страницMycobacterium Tuberculosis Thesisamandagraytulsa100% (2)

- A Review On The Diagnosis and Treatment of SyphiliДокумент8 страницA Review On The Diagnosis and Treatment of SyphiliRaffaharianggaraОценок пока нет

- Guidelines For The Management of Suspected and Confirmed Bacterial Meningitis inДокумент18 страницGuidelines For The Management of Suspected and Confirmed Bacterial Meningitis inswr88kv5p2Оценок пока нет

- Meningitis TBCДокумент12 страницMeningitis TBCJessica L. AlbornozОценок пока нет

- Fop Piano Palacios 2020Документ6 страницFop Piano Palacios 2020Muhammed GhaziОценок пока нет

- Kartamihardja2018 Article DiagnosticValueOf99mTc-ethambu PDFДокумент9 страницKartamihardja2018 Article DiagnosticValueOf99mTc-ethambu PDFrft akbrОценок пока нет

- Cutaneous Tuberculosis - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfДокумент5 страницCutaneous Tuberculosis - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfLinuel Quetua TrinidadОценок пока нет

- Abdominal CT in Patients With AIDS: Dmkoh,, B Langroudi, S P G PadleyДокумент11 страницAbdominal CT in Patients With AIDS: Dmkoh,, B Langroudi, S P G PadleyEnda RafiqohОценок пока нет

- PHD Thesis TuberculosisДокумент8 страницPHD Thesis TuberculosisBecky Goins100% (2)

- Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma Pneumoniae in Adolescents With Community-Acquired PneumoniaДокумент7 страницMacrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma Pneumoniae in Adolescents With Community-Acquired PneumoniaReza NovitaОценок пока нет

- Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Children: Increased Need For Better MethodsДокумент9 страницDiagnosis of Tuberculosis in Children: Increased Need For Better MethodsphobicmdОценок пока нет

- Children - Acute Transvers MyelitisДокумент6 страницChildren - Acute Transvers MyelitisHAKIMOPОценок пока нет

- Mycobacteria-Derived Biomarkers For Tuberculosis DiagnosisДокумент8 страницMycobacteria-Derived Biomarkers For Tuberculosis DiagnosisSantanu PalОценок пока нет

- Viruses 09 00011Документ17 страницViruses 09 00011Hany ZutanОценок пока нет

- Fped 07 00311Документ14 страницFped 07 00311frida puspitasariОценок пока нет

- Childhood CAPДокумент8 страницChildhood CAPAlex Toman Fernando SaragihОценок пока нет

- Clinical Presentations, Diagnosis, Mortality and Prognostic Markers of Tuberculous Meningitis in Vietnamese Children: A Prospective Descriptive StudyДокумент10 страницClinical Presentations, Diagnosis, Mortality and Prognostic Markers of Tuberculous Meningitis in Vietnamese Children: A Prospective Descriptive StudySilva Dicha GiovanoОценок пока нет

- Diagnosis, Initial Management, and Prevention of MeningitisДокумент8 страницDiagnosis, Initial Management, and Prevention of MeningitisBilly UntuОценок пока нет

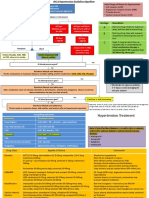

- Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaОт EverandPediatric Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaMotohiro KatoОценок пока нет

- Current Opinion: European Heart Journal (2017) 00, 1-14 Doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx003Документ14 страницCurrent Opinion: European Heart Journal (2017) 00, 1-14 Doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx003grace kelyОценок пока нет

- Chapter32 - UTI in ElderyДокумент4 страницыChapter32 - UTI in ElderyInes DantasОценок пока нет

- JNC8 HTNДокумент2 страницыJNC8 HTNTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- Anemia en AncianosДокумент8 страницAnemia en AncianosWilliam OslerОценок пока нет

- Antibacterial ActivityДокумент19 страницAntibacterial ActivityAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Beta-Blockers in Acute Heart FailureДокумент3 страницыBeta-Blockers in Acute Heart FailureAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Apoptosis Shaping of Embryo PDFДокумент10 страницApoptosis Shaping of Embryo PDFAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Dertmatitis AtopikДокумент7 страницDertmatitis AtopikAmanda FaradillahОценок пока нет

- High Altitude HypoxiaДокумент4 страницыHigh Altitude HypoxiaAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Apoptosis - A Biological PhenomenonДокумент13 страницApoptosis - A Biological PhenomenonAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- High Blood Pressure - ACC - AHA Releases Updated Guideline - Practice Guidelines - American Family PhysicianДокумент2 страницыHigh Blood Pressure - ACC - AHA Releases Updated Guideline - Practice Guidelines - American Family PhysicianAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Pulmonary AbscessДокумент5 страницPulmonary AbscessAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Adult Cutaneous Fungal Infections 1 DermatophytesДокумент61 страницаAdult Cutaneous Fungal Infections 1 DermatophytesAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Apoptosis - A Biological PhenomenonДокумент13 страницApoptosis - A Biological PhenomenonAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Hypersensitivities Dermatitis Atopic PDFДокумент70 страницHypersensitivities Dermatitis Atopic PDFSarahUtamiSr.Оценок пока нет

- STD Treatment 2015Документ140 страницSTD Treatment 2015Supalerk KowinthanaphatОценок пока нет

- Main Article - BM PancytopeniaДокумент10 страницMain Article - BM PancytopeniaAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Ireland Vaccination Guideline For GP 2018Документ56 страницIreland Vaccination Guideline For GP 2018Abdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Pulmonary AbscessДокумент5 страницPulmonary AbscessAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Section6 Psoriasis Guideline PDFДокумент38 страницSection6 Psoriasis Guideline PDFDesi RatnaningtyasОценок пока нет

- En V29n3a01Документ2 страницыEn V29n3a01Abdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Section6 Psoriasis Guideline PDFДокумент38 страницSection6 Psoriasis Guideline PDFDesi RatnaningtyasОценок пока нет

- STD Treatment 2015Документ140 страницSTD Treatment 2015Supalerk KowinthanaphatОценок пока нет

- The Essentials of Contraceptive TechnologyДокумент355 страницThe Essentials of Contraceptive TechnologyIndah PurnamasariОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Kulit 2Документ14 страницJurnal Kulit 2UmmulAklaОценок пока нет

- Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Inducedby Hydroxychloroquine PDFДокумент3 страницыAcute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Inducedby Hydroxychloroquine PDFAbdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Ireland Vaccination Guideline For GP 2018Документ56 страницIreland Vaccination Guideline For GP 2018Abdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Global Initiative For Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseДокумент139 страницGlobal Initiative For Chronic Obstructive Lung Diseaseport spyОценок пока нет

- Postgrad Med J 2004 Mathew 196 200Документ6 страницPostgrad Med J 2004 Mathew 196 200Abdur Rachman Ba'abdullahОценок пока нет

- Ulcus Decubitus PDFДокумент9 страницUlcus Decubitus PDFIrvan FathurohmanОценок пока нет

- NosodeДокумент2 страницыNosodeMuhammad Shahzad KhalidОценок пока нет

- Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis InfectionДокумент10 страницTreatment of Latent Tuberculosis InfectionRichard WooliteОценок пока нет

- Twaites Meningo TB 2013 PDFДокумент12 страницTwaites Meningo TB 2013 PDFgolin__Оценок пока нет

- 13-Risk Factors of Tuberculosis in ChildrenДокумент5 страниц13-Risk Factors of Tuberculosis in ChildrenAnthony Huaman MedinaОценок пока нет

- ComprehensiveUnifiedPolicy TBДокумент159 страницComprehensiveUnifiedPolicy TBallan14_reyesОценок пока нет

- TB in Postcolonial South India and Southeast AsiaДокумент30 страницTB in Postcolonial South India and Southeast AsiaVivek NeelakantanОценок пока нет

- Community Health NursingДокумент396 страницCommunity Health NursingAiza Oronce100% (2)

- LMR Book 2018Документ52 страницыLMR Book 2018Mohamed ArsathОценок пока нет

- Kangaroo Mother Care Rooming in UpdatedДокумент44 страницыKangaroo Mother Care Rooming in UpdatedStar DustОценок пока нет

- Cutaneous TBДокумент45 страницCutaneous TBWarren Lie100% (1)

- Drug Study FinalsДокумент4 страницыDrug Study FinalsKathleen Dela CruzОценок пока нет

- RD Manual Med and BathingДокумент5 страницRD Manual Med and Bathingapple m.Оценок пока нет

- CHN TP ReviewДокумент40 страницCHN TP ReviewPatrick Jon LumaghanОценок пока нет

- BRS Microbiology Flash-CardsДокумент500 страницBRS Microbiology Flash-CardsAmirsalar Eslami100% (1)

- The History of Immunology and VaccinesДокумент32 страницыThe History of Immunology and VaccinesClement del RosarioОценок пока нет

- John Bunyan (1628-1688) : The Captain of All These Men of Death'Документ56 страницJohn Bunyan (1628-1688) : The Captain of All These Men of Death'Johir ChowdhuryОценок пока нет

- Vaccines and Routine Immunization Strategies During The COVID 19 PandemicДокумент9 страницVaccines and Routine Immunization Strategies During The COVID 19 PandemicMěđ SimoОценок пока нет

- Review Notes in PHCДокумент130 страницReview Notes in PHCJohn Michael Manlupig Pitoy100% (1)

- Tuberculosis Power PointДокумент20 страницTuberculosis Power PointLeena LapenaОценок пока нет

- Bacillus Calmette-Guérin: (Not MMR)Документ2 страницыBacillus Calmette-Guérin: (Not MMR)Shanne ShamsuddinОценок пока нет

- Do Vitamins C and E Affect Respiratory InfectionsДокумент143 страницыDo Vitamins C and E Affect Respiratory Infectionspetri_jvОценок пока нет

- Slma Vaccines Guidelines 2011Документ111 страницSlma Vaccines Guidelines 2011Jude Roshan WijesiriОценок пока нет

- Treatment of Non Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer With BCG and Emda MMCДокумент7 страницTreatment of Non Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer With BCG and Emda MMCRyan IlhamОценок пока нет

- Expanded Program On ImmunizationДокумент4 страницыExpanded Program On ImmunizationcharmdoszОценок пока нет

- TB PDFДокумент66 страницTB PDFKyaw Zin HtetОценок пока нет

- Immunization Program of The PhilippinesДокумент9 страницImmunization Program of The Philippinesnelar MacabalitaoОценок пока нет

- What Is Primary ComplexДокумент18 страницWhat Is Primary ComplexMary Cruz100% (6)