Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Penjelasan Font Vladimir Script

Загружено:

PutriBudiasihАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Penjelasan Font Vladimir Script

Загружено:

PutriBudiasihАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Vladimir Script adalah font sikat-gaya, mirip dengan jenis huruf yang ditemukan pada tanda-tanda tua

department store yang dilukis dengan tangan selama tahun 1950. Surat-surat memiliki kemiringan yang

curam, dan huruf besar dan jumlahnya lebih informal. Banyak stroke huruf 'berakhir di terminal

melingkar, beberapa dengan jumlah dinamis kontras.

Vladimir Script paling baik digunakan dalam ukuran titik yang lebih besar, di mana rincian halus yang

bisa menari di halaman. Tipografi tampak luar biasa pada tanda-tanda dan kartu.

Link video

Anna Pavlova - The Dying Swan

Anna Pavlova performs ballet solos, 1920's - Film 7224

Anna Pavlova - 'Invitation to the Dance' aka 'Invitation to the Valse'

Anna Pavlovna (Matveyevna) Pavlova was born on January 31, 1881 in Ligovo to unwed parents. Her mother,

Lyubov Feodorovna was a laundress. Some sources, including The Saint Petersburg Gazette, state that her

biological father was the Jewish Russian banker Lazar Polyakov.

[1]

Her mother's second husband, Matvey

Pavlov, is believed to have adopted her at the age of three, by which she acquired his last name.

Pavlova's passion for the art of ballet was ignited when her mother took her to a performance of Marius

Petipa's original production of The Sleeping Beauty at the Imperial Maryinsky Theater. The lavish spectacle

made an impression on Pavlova. At the age of nine, her mother took her to audition for the renowned Imperial

Ballet School. Because of her youth, and what was considered her "sickly" appearance, she was not chosen. In

1891, she was finally accepted at the age of 10. She appeared for the first time on stage in Marius Petipa's Un

conte de fes (A Fairy Tale), which the ballet master staged for the students of the school.

Young Pavlova's years of training were difficult. Classical ballet did not come easily to her. Her severely arched

feet, thin ankles, and long limbs clashed with the small and compact body in favour for the ballerina at the time.

Her fellow students taunted her with such nicknames as The broom and La petite sauvage (The little savage).

Undeterred, Pavlova trained to improve her technique. She would practise and practise after learning a step.

She took extra lessons from the noted teachers of the day Christian Johansson, Pavel Gerdt, Nikolai

Legat and from Enrico Cecchetti, considered the greatest ballet virtuoso of the time and founder of

the Cecchetti method, a very influential ballet technique used to this day. In 1898, she entered the classe de

perfection of Ekaterina Vazem, former Prima ballerina of the Saint Petersburg Imperial Theatres.

During her final year at the Imperial Ballet School, she performed many roles with the principal company. She

graduated in 1899 at age 18, chosen to enter the Imperial Ballet a rank ahead ofcorps de ballet as a coryphe.

She made her official dbut at the Mariinsky Theatre in Pavel Gerdt's Les Dryades prtendues (The False

Dryads). Her performance drew praise from the critics, particularly the great critic and historian Nikolai

Bezobrazov.

Students of the Imperial Ballet School in Marius Petipa's Un conte de fes. A ten year-old Anna Pavlova participated in this

work in her first ever ballet performance. She is photographed here on the left holding the birdcage. St. Petersburg, 1891.

Photographic postcard of Anna Pavlova as the Princess Aspicia in the Petipa/Pugni The Pharaoh's Daughter, Saint

Petersburg, c. 1910

Anna Pavlova in the Fokine/Saint-Sans The Dying Swan, Saint Petersburg, 1905

Career[edit]

At the height of Petipa's strict academicism, the public was taken aback by Pavlova's style, a combination of a

gift that paid little heed to academic rules: she frequently performed with bent knees, bad turnout,

misplaced port de bras and incorrectly placed tours. Such a style in many ways harked back to the time of

the romantic ballet and the great ballerinas of old.

Pavlova performed in various classical variations, pas de deux and pas de trois in such ballets as La

Camargo, Le Roi Candaule,Marcobomba and The Sleeping Beauty. Her enthusiasm often led her astray: once

during a performance as the River Thames in Petipa's The Pharaoh's Daughter her energetic double pique

turns led her to lose her balance, and she ended up falling into the prompter's box. Her weak ankles led to

difficulty while performing as the fairy Candide in Petipa's The Sleeping Beauty, leading the ballerina to revise

the fairy's jumpsen pointe, much to the surprise of the Ballet Master. She tried desperately to imitate the

renowned Pierina Legnani, Prima ballerina assolutaof the Imperial Theaters. Once during class she attempted

Legnani's famous fouetts, causing her teacher Pavel Gerdt to fly into a rage. He told her,

"... leave acrobatics to others. It is positively more than I can bear to see the pressure such steps put on your

delicate muscles and the severe arch of your foot. I beg you to never again try to imitate those who are

physically stronger than you. You must realize that your daintiness and fragility are your greatest assets. You

should always do the kind of dancing which brings out your own rare qualities instead of trying to win praise by

mere acrobatic tricks."

Pavlova rose through the ranks quickly, becoming a favorite of the old maestro Petipa. It was from Petipa

himself that Pavlova learned the title role in Paquita, Princess Aspicia in The Pharaoh's Daughter, Queen Nisia

in Le Roi Candaule, and Giselle. She was named danseuse in 1902, premire danseuse in 1905, and

finally prima ballerina in 1906 after a resounding performance in Giselle. Petipa revised many grand pas for

her, as well as many supplemental variations. She was much celebrated by the fanatical balletomanes of

Tsarist Saint Petersburg, her legions of fans calling themselves the Pavlovatzi.

When the ballerina Mathilde Kschessinska was pregnant in 1901, she coached Pavlova in the role of Nikya

in La Bayadre. Kschessinska, not wanting to be upstaged, was certain Pavlova would fail in the role, as she

was considered technically inferior because of her small ankles and lithe legs. Instead audiences became

enchanted with Pavlova and her frail, ethereal look, which fitted the role perfectly, particularly in the scene The

Kingdom of the Shades.

Her feet were extremely rigid, so she strengthened her pointe shoe by adding a piece of hard wood on the

soles for support and curving the box of the shoe. At the time, many considered this "cheating", for a ballerina

of the era was taught that she, not her shoes, must hold her weight en pointe. In Pavlova's case this was

extremely difficult, as the shape of her feet required her to balance her weight on her little toes. Her solution

became, over time, the precursor of the modern pointe shoe, as pointe work became less painful and easier for

curved feet. According to Margot Fonteyn's biography, Pavlova did not like the way her invention looked in

photographs, so she would remove it or have the photographs altered so that it appeared she was using a

normal pointe shoe.

[2]

Pavlova is perhaps most renowned for creating the role of The Dying Swan, a solo choreographed for her

by Michel Fokine. The ballet, created in 1905, is danced to Le cygne from The Carnival of the

Animals by Camille Saint-Sans. Pavlova also choreographed several solos herself, one of which is The

Dragonfly, a short ballet set to music by Fritz Kreisler. While performing the role, Pavlova wore a gossamer

gown with large dragonfly wings fixed to the back.

In the first years of the Ballets Russes, Pavlova worked briefly for Sergei Diaghilev. Originally she was to dance

the lead in Mikhail Fokine's The Firebird, but refused the part, as she could not come to terms with Igor

Stravinsky's avant-garde score, and the role was given to Tamara Karsavina. All her life Pavlova preferred the

melodious "musique dansante" of the old maestros such as Cesare Pugni and Ludwig Minkus, and cared little

for anything else which strayed from the salon-style ballet music of the 19th century.

By the early 20th century she had founded her own company and performed throughout the world, with a

repertory consisting primarily of abridgements of Petipa's works, and specially choreographed pieces for

herself. Members of her company included Kathleen Crofton. The ballet writer Cyril Johnson said

that"her bourres were like a string of pearls".

Pavlova had a rivalry with Tamara Karsavina. According to the film A Portrait of Giselle, Karsavina recalls a

'wardrobe malfunction'. During one performance her shoulder straps fell and she accidentally exposed herself,

and Pavlova reduced an embarrassed Karsavina to tears.

England[edit]

After leaving Russia, Pavlova moved to London, England, settling, in 1912, at the Ivy House on North End

Road, Golders Green, north of Hampstead Heath, where she lived for the rest of her life. The house had an

ornamental lake where she fed her pet swans, and where now stands a statue of her by the Scots

sculptor George Henry Paulin. The house was featured in the film Anna Pavlova. It is now the London Jewish

Cultural Centre, but a blue plaque marks it as a site of significant historical interest being Pavlova's

home.

[3][4]

While in London, Pavlova was influential in the development of British ballet, most notably inspiring

the career of Alicia Markova. The Gate pub, located on the border of Arkley and Totteridge (London Borough of

Barnet), has a story, framed on its walls, describing a visit by Pavlova and her dance company.

Pavlova was introduced to audiences in the United States by Max Rabinoff during his time as managing

director of the Boston Grand Opera Company from 1914 to 1917 and was featured there with her Russian

Ballet Company during that period.

[5]

Personal life[edit]

Victor Dandr, her manager and companion, asserted he was her husband in his biography of the dancer in

1932: Anna Pavlova: In Art & Life

[6]

Victor Dandr wrote of Pavlova's many charity dance performances and charitable efforts to support Russian

orphans in post-World War I Paris

...who were in danger of finding themselves literally in the street. They were already suffering terrible privations

and it seemed as though there would soon be no means whatever to carry on their education.

[7]

Fifteen girls were adopted into a home Pavlova purchased near Paris at Saint-Cloud, overseen by the

Comtesse de Guerne and supported by her performances and funds solicited by Pavlova, including many small

donations from members of the Camp Fire Girls of America who made her an honorary member.

[8]

During her life she had many pets including a Siamese cat, various dogs, Cadilan birds and swans.

[9]

Dandr

indicated she was a lifelong lover of animals and this is evidenced by photographic portraits she sat for which

often included an animal she loved. A formal studio portrait was made of her with Jack, her favorite swan.

[10]

Death[edit]

Anna Pavlova arriving in The Hague in 1927

Urn with Anna Pavlova's ashes

While touring in The Hague, Pavlova was told that she had pneumonia and required an operation. She was

also told that she would never be able to dance again if she went ahead with it. She refused to have the

surgery, saying "If I can't dance then I'd rather be dead." She died of pleurisy, in the bedroom next to the

Japanese Salon of the Hotel Des Indes in The Hague, three weeks short of her 50th birthday.

Victor Dandr wrote the Anna Pavlova died a half hour past midnight on Friday, January 23, 1931 with her

maid Marguerite Letienne, Dr. Zalevsky and himself at her bedside. Her last words were, "Get my 'Swan'

costume ready."

[11]

In accordance with old ballet tradition, on the day she was to have next performed, the show went on as

scheduled, with a single spotlight circling an empty stage where she would have been. Memorial services were

held in the Russian Orthodox Church in London. Anna Pavlova was cremated, and her ashes placed in

a columbarium at Golders Green Crematorium, where her urn was subsequently adorned with her ballet shoes

(which since then have been stolen).

Pavlova's ashes have been a source of much controversy, following attempts by Valentina Zhilenkova and

Moscow mayor Yury Luzhkov, to have them flown to Moscow for interment in theNovodevichy Cemetery.

These attempts were based on claims that it was Pavlova's dying wish that her ashes be returned to Russia

following the fall of Communism. These claims were later found to be false, as there is no evidence to suggest

that this was her wish at all. The only documentary evidence that suggests that such a move would be possible

is in the will of Pavlova's husband, who stipulated that if Russian authorities agreed to such a move and treated

her remains with proper reverence, then the crematorium caretakers should agree to it. Despite this clause, the

will does not contain a formal request or plans for a posthumous journey to Russia.

The most recent attempt to move Pavlova's remains to Russia came in 2001. Golders Green Crematorium had

made arrangements for them to be flown to Russia for interment on 14 March 2001, in a ceremony to be

attended by various Russian dignitaries. This plan was later abandoned after Russian authorities withdrew

permission for the move. It was later revealed that neither Pavlova's family nor the Russian Government had

sanctioned the move and that they had agreed the remains should stay in London.

[12][13]

Legacy[edit]

Commemorative coin, Central Bank of Russia

Pavlova inspired the choreographer Frederick Ashton when as a boy of 13 he saw her dance in the Municipal

Theater in Lima, Peru.

The Pavlova dessert is believed to have been created in honour of the dancer in Wellington during her tour of

New Zealand and Australia in the 1920s. The nationality of its creator has been a source of argument between

the two nations for many years, but formal research indicates New Zealand as the source.

[14]

The Jarabe Tapato, known in English as the 'Mexican Hat Dance', gained popularity outside of Mexico when

Pavlova created a staged version in pointe shoes, for which she was showered with hats by her adoring

Mexican audiences. Afterward, in 1924, the Jarabe Tapato was proclaimed Mexicos national dance.

She once said that the country that would produce the best ballerina in history would be the United States

because of all the different cultures that came together there.

[citation needed]

Anna Pavlova was able to complete 37 turns while on top of a moving elephant while on a tour in China.

In 1980, Igor Carl Faberge licensed a collection of 8-inch Full Lead Crystal Wine Glasses to commemorate the

centenary of Anna's birth. The glasses were crafted in Japan under the supervision of The Franklin Mint. A

frosted image of Anna Pavlova appears in the stem of each glass. Originally each set contained 12 glasses.

Pavlova's life was depicted in the 1983 film Anna Pavlova.

There are at least five memorials to Pavlova in London, England: a contemporary sculpture by Tom Merrifield

of Pavlova as the Dragonfly in the grounds of Ivy House, a sculpture by Scot George Henry Paulin in the

middle of the Ivy House pond, a blue plaque on the front of Ivy House, a statuette sitting with the urn that holds

her ashes in Golders Green Crematorium, and the gilded statue atop the Victoria Palace Theatre.

[15][16]

When the Victoria Palace Theatre in London, England, opened in 1911, a gilded statue of Pavlova had been

installed above the cupola of the theatre. This was taken down for its safety duringWorld War II and was lost. In

2006, a replica of the original statue was restored in its place.

[17]

A McDonnell Douglas MD-11 of the Dutch airline KLM, with the registration PH-KCH carries her name. It was

delivered on August 31, 1995

Anna Pavlova appears as a character in the fourth episode of the British series Mr Selfridge, played by real-life

ballerina Natalia Kremen.

Gallery[edit]

Christmas pavlova

Stained glass window entitled "El Jarabe Tapatio"

The Butterfly (Costume Design by Lon Bakst for Anna Pavlova), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

London, Victoria Palace Theatre, rooftop statue of Anna Pavlova

See also[edit]

Biography portal

List of Russian ballet dancers

Notes[edit]

1. Jump up^

, (.: Oleg Kerensky. Anna Pavlova. N-Y., Dutton Publ.,

1973. ISBN 0-525-17658-6)

2. Jump up^ Fonteyn, Margot, Pavlova, Portrait of a Dancer. Viking, 1984.

3. Jump up^ Blue plaque, Hendon Corporation.

4. Jump up^ "London Jewish Cultural Centre Now Booking". London Jewish Cultural Centre. Retrieved 5

May 2012.

5. Jump up^ "Max Rabinoff Papers". Columbia.edu. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

6. Jump up^ "Anna Pavlova: In Art & Life" (London 1932; reprinted in the USA Arno Pres NYC 1979) author's

forward

7. Jump up^ "Anna Pavlova: In Art & Life" (London 1932; reprinted in the USA Arno Pres NYC 1979) p 248

8. Jump up^ "Anna Pavlova: In Art & Life" (London 1932; reprinted in the USA Arno Pres NYC 1979) pp 251-

259

9. Jump up^ "Anna Pavlova: In Art & Life" (London 1932; reprinted in the USA Arno Pres NYC 1972, 1979)

10. Jump up^ "Anna Pavlova: In Art & Life" (London 1932; reprinted in the USA Arno Pres NYC 1979) p 53, pp

329-349

11. Jump up^ "Anna Pavlova: In Art & Life" (London 1932; reprinted in the USA Arno Pres NYC 1979) p 360

12. Jump up^ "BBC News, Pavlova's ashes stay in London". BBC News. 2001-03-08. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

13. Jump up^ Amelia Gentleman in Moscow (2001-03-07). "Anger as Pavlova's ashes leave London for

Moscow". The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

14. Jump up^ Leach, Helen, The Pavlova Story: A Slice of New Zealand's Culinary History, University of Otago

Pr, 30 August 2008, ISBN 978-1-877372-57-5

15. Jump up^ "Ballerinas & Meringues: Pavlova 2012 @ Ivy House", Londonist.com, accessed January 14,

2013.

16. Jump up^ "Ten Dancer Statues Of London", Londonist.com, accessed January 14, 2013.

17. Jump up^ City-of-London.com accessed March 27, 2011

External links[edit]

Other[edit]

Anna Pavlova in Australia 1926, 1929 Tours - programs and ephemera held by the National Library of

Australia

Film of Anna Pavlova

Pictures of Anna Pavlova - digitised and held by the National Library of Australia

Creative Quotations from Anna Pavlova

Andros on Ballet

Heroine Worship: Anna Pavlova, The Swan

Anna Pavlova on Encyclopaedia Britannica

Guide to the Collection on Anna Pavlova. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine,

California.

Anna Pavlova at the Internet Movie Database

Anna Pavlova at Find a Grave

Wikimedia Commons has

media related to Anna

Pavlova.

Authority control

WorldCat

VIAF: 42020434

LCCN: n79033028

ISNI: 0000 0000 8120 9762

GND: 118641557

SUDOC: 032315856

BNF: cb13749631q

NDL: 00550052

Categories:

1881 births

1931 deaths

19th-century Russian people

20th-century Russian people

Ballets Russes dancers

Deaths from lung disease

Eastern Orthodox Christians from Russia

English people of Russian descent

Imperial Russian ballet dancers

Imperial Russian emigrants to the United Kingdom

National Museum of Dance Hall of Fame inductees

Mistresses of Russian royalty

People from Saint Petersburg

Prima ballerinas

Russian Orthodox Christians

Navigation menu

Create account

Log in

Article

Talk

Read

Edit

View history

Main page

Contents

Featured content

Current events

Random article

Donate to Wikipedia

Wikimedia Shop

Interaction

Help

About Wikipedia

Community portal

Recent changes

Contact page

Tools

Print/export

Languages

Afrikaans

(

Catal

Dansk

Deutsch

Eesti

Espaol

Esperanto

Franais

Frysk

Hrvatski

Italiano

Latina

Latvieu

Ltzebuergesch

Nederlands

Norsk bokml

Polski

Portugus

Ripoarisch

Runa Simi

Simple English

Slovenina

/ srpski

Srpskohrvatski /

Suomi

Svenska

Tagalog

Trke

Ting Vit

Winaray

Edit links

This page was last modified on 16 January 2014 at 00:20.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site,

you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

Privacy policy

About Wikipedia

Disclaimers

Contact Wikipedia

Developers

Mobile view

Вам также может понравиться

- The NutcrackerДокумент13 страницThe NutcrackerIng Jenny DavilaОценок пока нет

- Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes (1909-1929) and Petipa's MasterworksДокумент26 страницDiaghilev’s Ballet Russes (1909-1929) and Petipa's MasterworksTTОценок пока нет

- History of Russian BalletДокумент8 страницHistory of Russian BalletSlev1822Оценок пока нет

- Journal Baby PDFДокумент18 страницJournal Baby PDFAruni AzizahОценок пока нет

- Rudolf Von Laban - Lisa Ullmann - The Mastery of Movement-Macdonald PDFДокумент210 страницRudolf Von Laban - Lisa Ullmann - The Mastery of Movement-Macdonald PDFAzael Contreras100% (1)

- The Russian Ballet According to Ellen TerryДокумент72 страницыThe Russian Ballet According to Ellen TerryBibusca Costel50% (4)

- Dancing The Score: Dance Notation and DifféranceДокумент13 страницDancing The Score: Dance Notation and DifféranceVicki WattsОценок пока нет

- World's first ballet school established in 1661Документ6 страницWorld's first ballet school established in 1661Nexer Aguillon100% (1)

- Classical Ballet DanceДокумент31 страницаClassical Ballet DanceJay CeeОценок пока нет

- Tchaikovsky (G.bantock) - Suite Da 'Il Lago Dei Cigni' Op.20 (Trascr. Per Pf. Solo)Документ36 страницTchaikovsky (G.bantock) - Suite Da 'Il Lago Dei Cigni' Op.20 (Trascr. Per Pf. Solo)Luca D'Agostino100% (1)

- Violin Playing As I Teach It (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)От EverandViolin Playing As I Teach It (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)Рейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (3)

- RodeoДокумент3 страницыRodeoJohnny WattОценок пока нет

- NullДокумент15 страницNullapi-26769326100% (1)

- Days With Ulanova: An Intimate Portrait of the Legendary Russian BallerinaОт EverandDays With Ulanova: An Intimate Portrait of the Legendary Russian BallerinaОценок пока нет

- 2022 03 21TheNewYorkerДокумент86 страниц2022 03 21TheNewYorkerCopame Mkt100% (2)

- Exam Essentials Proficiency Practice Test 4Документ33 страницыExam Essentials Proficiency Practice Test 4scholakowa100% (4)

- Procurement 20B NegotaitionsДокумент49 страницProcurement 20B Negotaitionsbalaje99 kОценок пока нет

- Violin Playing As I Teach It (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)От EverandViolin Playing As I Teach It (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Рейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (3)

- The Lindy by Margaret Batiuchok NYU Masters Thesis 16 May 1988 History of Swing DancingДокумент112 страницThe Lindy by Margaret Batiuchok NYU Masters Thesis 16 May 1988 History of Swing DancingScribdInsight100% (3)

- Mlle Anna Pavlowa - 00Документ26 страницMlle Anna Pavlowa - 00Carlos GutiérrezОценок пока нет

- SPA Theater Arts CGДокумент34 страницыSPA Theater Arts CGAvengel Joseph Federis100% (10)

- Chekhov Guide PDFДокумент21 страницаChekhov Guide PDFBogdan FlorinОценок пока нет

- Pe 12 Midterm To PrintДокумент12 страницPe 12 Midterm To PrintKristina PabloОценок пока нет

- Mindy Aloff - Dance Anecdotes - Stories From The Worlds of Ballet, Broadway, The Ballroom, and Modern Dance-Oxford University Press, USA (2006)Документ285 страницMindy Aloff - Dance Anecdotes - Stories From The Worlds of Ballet, Broadway, The Ballroom, and Modern Dance-Oxford University Press, USA (2006)Merve ErgünОценок пока нет

- A Brief History of the Evolution of BalletДокумент3 страницыA Brief History of the Evolution of BalletSevda Kal SözerОценок пока нет

- World Dance Cultures From Ritual To Spectacle (Patricia Leigh Beaman)Документ663 страницыWorld Dance Cultures From Ritual To Spectacle (Patricia Leigh Beaman)Johanna Mahabir100% (1)

- Anna Pavlova Research PaperДокумент7 страницAnna Pavlova Research PaperaubreyepОценок пока нет

- Form of DanceДокумент3 страницыForm of DanceCherymae AndradeОценок пока нет

- Petipa, 12th March 2013Документ3 страницыPetipa, 12th March 2013wattsbethanyОценок пока нет

- Arandia, Mary JoyceДокумент8 страницArandia, Mary JoyceXine ShakuraОценок пока нет

- History of Tchaikovsky's Iconic Ballet "Swan LakeДокумент2 страницыHistory of Tchaikovsky's Iconic Ballet "Swan LakeSilvana StamenkovskaОценок пока нет

- Research Paper On The History of BalletДокумент5 страницResearch Paper On The History of Balletjpkoptplg100% (1)

- Anna Pavlova: By: Geri Ferrer Dance Block 5Документ7 страницAnna Pavlova: By: Geri Ferrer Dance Block 5geriОценок пока нет

- The Art of The Ballets Russes CapturedДокумент23 страницыThe Art of The Ballets Russes Capturedmarisol galloОценок пока нет

- A New Kind of CompanyДокумент18 страницA New Kind of CompanyFilipa MonteiroОценок пока нет

- Sylvia (Ballet) : HistoryДокумент10 страницSylvia (Ballet) : HistoryIng Jenny DavilaОценок пока нет

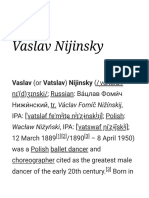

- Vaslav Nijinsky Biography - The Greatest Male Dancer of the Early 20th CenturyДокумент122 страницыVaslav Nijinsky Biography - The Greatest Male Dancer of the Early 20th CenturyEzra Mikah G. CaalimОценок пока нет

- PAVANAДокумент3 страницыPAVANAUlyssesm90Оценок пока нет

- Giselle La Sylphide: Pointe WorkДокумент2 страницыGiselle La Sylphide: Pointe Workchris rosalesОценок пока нет

- Cecchetti TextДокумент334 страницыCecchetti TextJuan Pablo RomeroОценок пока нет

- What Is Ballet?: History of Ballet DanceДокумент1 страницаWhat Is Ballet?: History of Ballet DanceFiorella Alejandro GalvanОценок пока нет

- Lesson 2: Dancing Toward The 21 CenturyДокумент37 страницLesson 2: Dancing Toward The 21 CenturyJuliana Brock0% (1)

- Advanced Ballet Unit UpdatedДокумент12 страницAdvanced Ballet Unit UpdatedMaria QuinteroОценок пока нет

- Eonnagata: Sadler's Wells, London in Association With Ex Machina & Sylvie Guillem PresentsДокумент16 страницEonnagata: Sadler's Wells, London in Association With Ex Machina & Sylvie Guillem PresentsfluxusmalagaОценок пока нет

- Komatsu Wheel Loader Wa100 1 Wa150!1!10001 and Up Operation Maintenance Manual Seam04160101Документ22 страницыKomatsu Wheel Loader Wa100 1 Wa150!1!10001 and Up Operation Maintenance Manual Seam04160101jasonhorne240296mnb100% (27)

- BalletДокумент3 страницыBalletHiep Nguyen KhacОценок пока нет

- Kyla Mae P. Laguna Bsba1-Block 4 Ramon ObusanДокумент4 страницыKyla Mae P. Laguna Bsba1-Block 4 Ramon ObusanXine ShakuraОценок пока нет

- The Nutcracker Student Matinee GuideДокумент16 страницThe Nutcracker Student Matinee GuidekrparfittОценок пока нет

- Y.Y. Cai - Tesina Storia Della Musica Anno 21-22Документ13 страницY.Y. Cai - Tesina Storia Della Musica Anno 21-22Yang Yang CaiОценок пока нет

- Csardaskiralyno Brusszel 2015 Balassi Intezet enДокумент4 страницыCsardaskiralyno Brusszel 2015 Balassi Intezet enBalassi IntézetОценок пока нет

- Dance IndexДокумент16 страницDance Indexmordidacampestre100% (1)

- Sergei DiaghilevДокумент38 страницSergei DiaghilevEzra Mikah G. CaalimОценок пока нет

- Republic of The PhilippinesДокумент8 страницRepublic of The PhilippinesTimothy John PabloОценок пока нет

- The Fairy DollДокумент2 страницыThe Fairy DollRigodon Lopez LopezОценок пока нет

- Les SylphidesДокумент4 страницыLes SylphidesIng Jenny DavilaОценок пока нет

- BalletДокумент13 страницBalletAllie MundekisОценок пока нет

- Operas Every Child Should Know: Descriptions of the Text and Music of Some of the Most Famous MasterpiecesОт EverandOperas Every Child Should Know: Descriptions of the Text and Music of Some of the Most Famous MasterpiecesОценок пока нет

- Vaslav Nijinsky: Famous Russian Ballet DancerДокумент2 страницыVaslav Nijinsky: Famous Russian Ballet DancerDaphneyОценок пока нет

- Stravinsky PetrushkaДокумент3 страницыStravinsky Petrushkaiñaki SorianoОценок пока нет

- 2018 4 SirotkinaДокумент11 страниц2018 4 SirotkinaАнтон ЧернецовОценок пока нет

- Feature Article-Diaghilev and The Golden Age of Ballet RusseДокумент2 страницыFeature Article-Diaghilev and The Golden Age of Ballet Russevicky_mc18Оценок пока нет

- Free PPT Templates for PresentationsДокумент3 страницыFree PPT Templates for PresentationsPutriBudiasihОценок пока нет

- Baby Memory BookДокумент6 страницBaby Memory BookPutriBudiasihОценок пока нет

- Demo planner template download and purchase guideДокумент92 страницыDemo planner template download and purchase guidePutriBudiasihОценок пока нет

- Buletin As-Sunnah Edisi 70Документ2 страницыBuletin As-Sunnah Edisi 70PutriBudiasihОценок пока нет

- Donald Duck April Fools Maze Printables 0311 FDCOMДокумент1 страницаDonald Duck April Fools Maze Printables 0311 FDCOMPutriBudiasihОценок пока нет

- Research Copy KimДокумент19 страницResearch Copy KimKevin Roland VargasОценок пока нет

- Presentation Japan CultureДокумент3 страницыPresentation Japan Cultureδιάβολος дьяволОценок пока нет

- Book of Abstracts and BiosДокумент31 страницаBook of Abstracts and BiosLise UytterhoevenОценок пока нет

- Entropy 2014Документ396 страницEntropy 2014Jordan StupnikovОценок пока нет

- Essential Spanish Dance - SevillanasДокумент11 страницEssential Spanish Dance - SevillanasArmin ParvinОценок пока нет

- Shoemakers DanceДокумент1 страницаShoemakers DanceNihan Atlığ SimpsonОценок пока нет

- Ej 967723Документ11 страницEj 967723api-541799317Оценок пока нет

- Rubrics For DancingДокумент1 страницаRubrics For DancingDAVID JONH ACOSTAОценок пока нет

- Daily Lesson Log Plaridel National High School 9 Kilven D. Masion Mapeh (Physical Education) 2Документ5 страницDaily Lesson Log Plaridel National High School 9 Kilven D. Masion Mapeh (Physical Education) 2KILVEN MASIONОценок пока нет

- Lesson 7 - 8Документ3 страницыLesson 7 - 8Min MatmatОценок пока нет

- Resume Wynne WharffДокумент4 страницыResume Wynne Wharffapi-578367237Оценок пока нет

- PE and Health 3 Module 1 (Week 1 and 2)Документ4 страницыPE and Health 3 Module 1 (Week 1 and 2)Robert Clavo100% (1)

- TangoДокумент1 страницаTangomastyОценок пока нет

- Philippine ArtistsДокумент40 страницPhilippine ArtistsLaurent Ashly ArellanoОценок пока нет

- Kalabharathi Fest BrochureДокумент6 страницKalabharathi Fest BrochureRamdasDasОценок пока нет

- Eco-Friendly Art of Bhil Tribe in Nandurbar District (MS)Документ6 страницEco-Friendly Art of Bhil Tribe in Nandurbar District (MS)Anonymous CwJeBCAXpОценок пока нет

- Fosse Fact FileДокумент1 страницаFosse Fact FilekeiraОценок пока нет

- Lesson 2 Modern Contemporary Dance PDFДокумент8 страницLesson 2 Modern Contemporary Dance PDFJohnlloyd MontierroОценок пока нет

- Wayang Wong in The Court of YogyakartaДокумент24 страницыWayang Wong in The Court of YogyakartaImran NawawiОценок пока нет

- Interpretative DancДокумент5 страницInterpretative Dancgrafei pennaОценок пока нет