Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

6 Frontier Jerusalem: Blurred Separation and Uneasy Coexistence in A Divided City

Загружено:

Daysilirion0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

15 просмотров26 страницThis essay explores the city of Jerusalem, which lies at the heart of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. With its future tied to the future of the conflict, Jerusalem remains caught between two options. Re-thinking the frontier as a site of both conflict and coexistence is key to imagining future possibilities for the city.

Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

6 Frontier Jerusalem: Blurred Separation and Uneasy Coexistence in a Divided City

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документThis essay explores the city of Jerusalem, which lies at the heart of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. With its future tied to the future of the conflict, Jerusalem remains caught between two options. Re-thinking the frontier as a site of both conflict and coexistence is key to imagining future possibilities for the city.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

15 просмотров26 страниц6 Frontier Jerusalem: Blurred Separation and Uneasy Coexistence in A Divided City

Загружено:

DaysilirionThis essay explores the city of Jerusalem, which lies at the heart of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. With its future tied to the future of the conflict, Jerusalem remains caught between two options. Re-thinking the frontier as a site of both conflict and coexistence is key to imagining future possibilities for the city.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 26

http://the.sagepub.

com/

Thesis Eleven

http://the.sagepub.com/content/121/1/76

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0725513614526156

2014 121: 76 Thesis Eleven

Rachel Busbridge

city

Frontier Jerusalem: Blurred separation and uneasy coexistence in a divided

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at: Thesis Eleven Additional services and information for

http://the.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://the.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

http://the.sagepub.com/content/121/1/76.refs.html Citations:

What is This?

- Apr 2, 2014 Version of Record >>

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Article

Frontier Jerusalem:

Blurred separation and

uneasy coexistence in a

divided city

Rachel Busbridge

Freie Universitat Berlin, Germany

Abstract

In this essay, I explore the city of Jerusalem, which not only lies at the heart of the

Israeli-Palestinian conflict but is inextricably shaped by its developments. Nominally

unified under Israeli sovereignty, Jerusalem nevertheless remains starkly divided

between an Israeli west and an occupied Palestinian east and is best understood

as a frontier city characterized by long-simmering tensions and quotidian conflict.

With its future tied to the future of the conflict, Jerusalem remains caught between

two options: the almost global preference for the citys repartition in accordance

with a two-state solution and the Israeli desire to maintain the status quo. A closer

look at contemporary Jerusalem, however, reveals the untenability of both options.

In this essay, I seek to document how the reality of Israeli-Palestinian division sits

alongside a dynamic of blurred separation in the city, which has forged an uneasy

coexistence of sorts. Re-thinking the frontier as a site of both conflict and coexis-

tence, I argue, is key to imagining future possibilities for the city that do not rest on

the desire for ethnically-pure spaces, but are rather guided by a politics of co-

presence that recognizes the impossibility of disentangling Arab and Jewish histories,

memories and connections to the city.

Keywords

Divided cities, frontier, Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Jerusalem, settler colonialism

Corresponding author:

Rachel Busbridge, Freie Universitat Berlin, Altensteinstr. 40, Institut fur Islamwissenschaft, Berlin 14195,

Germany.

Email: r.busbridge@latrobe.edu.au

Thesis Eleven

2014, Vol. 121(1) 76100

The Author(s) 2014

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0725513614526156

the.sagepub.com

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Introduction

Every year around May, Israel celebrates Yom Yerushalayim (Jerusalem Day), a national

holiday commemorating the Israeli victory in 1967s Six Day War, which saw the

country establish control over the Old City and reunify Jerusalem. Close to 100,000

right-wing Israeli activists

1

spill onto the streets in marches supported by the Jerusalem

municipality and escorted by police, following a route that takes them into the conquered

Old City to the Western Wall (Kotel) and which, from 2011, has also included Jerusa-

lems Palestinian neighbourhoods. Streets are closed to traffic and cordoned off for the

thousands of white-shirted revellers and their sea of blue-and-white flags to march, chant

and dance through the neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah to Damascus Gate (Bab al-

Amoud), the main entrance of the Old Citys Muslim quarter, amassing along the narrow

thoroughfare of al-Wad Street that leads to the Kotel. Death to the Arabs, Mohammed

was a pig and Let your village burn are favoured slogans of the marchers, while Pales-

tinian families lock themselves away in their houses, peering down from windows. Small

business owners will shutter their shops, encouraged by Jerusalems police who are con-

cerned about damage to property and the outbreak of clashes; a brave few will remain

open, risking vandalism and assaults from the keyed up revellers. Culminating in the

Western Wall plaza, the march turns into evening festivities. The sounds continue echo-

ing into the night and over the rooftops of the Old City; its Palestinian residents fall

asleep listening to the celebrations that mark their occupation.

The city of Jerusalem is, without doubt, one of the most lauded in the world. The

celebrated birthplace of three monotheistic religions, it is a revered destination for the

many pilgrims who come to wander the streets of the Old City, circumambulate

the purported site of Jesus resurrection, touch the stones of the fallen Second Temple or

pray in the al-Aqsa mosque, which holds its own in silver against the golden-blue Dome

of the Rock. Yet, Jerusalem is also the political, geographical and cultural heart of the

Israeli-Palestinian conflict (Makdisi 2010), something which is often missed by the tour-

ists and pilgrims who marvel at its collection of photo opportunities and soft beauty.

Indeed, for all the claims to its alleged reunification, the city remains starkly divided

between an Israeli West and an occupied Palestinian East, and is the site of slow-

simmering religious, political and cultural tensions between the two, effectively segre-

gated, peoples. Jerusalem is quite evidently a frontier city, framed and shaped by intract-

able conflict and largely irreconcilable claims to ownership and sovereignty, and like all

frontier cities it is characterized by both confrontation and contradiction (Pullan 2011).

In many ways, the question of the citys future is fundamentally a question about the

future of the conflict; and like the conflict more broadly, the hegemonic terms of debate

remained trapped between the Israeli states desire to maintain Jerusalem as its united

and complete capital and the global preference for the citys repartitioning into an

Israeli and Palestinian capital, as per the so-called two-state solution. Nevertheless,

there is a burgeoning area of work sceptical of this dominant paradigm, with a number

of scholars calling for more creative and importantly, just ways of imagining the

citys future (e.g. Dumper 2013; Makdisi 2010; Mendel 2013; Weizman 2007).

In this essay, I join these scholars in calling for new ways of thinking about con-

temporary Jerusalem. It is clear that the status quo/two-state paradigm is not only

Busbridge 77

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

untenable, but unjust insofar as it is unlikely to solve the problems that have caused the

conflict in the first place. On the one hand, Jerusalems ongoing divisions and tensions

go very much against the Israeli claim to have united the city, as does the persistent

inequality that structures the lives and encounters of Palestinian Arabs and Israeli Jews.

On the other hand, the notion that Jerusalem could be divided in the middle to create a

pure Jewish west and a pure Palestinian east is fallacious in light of the facts on

the ground, which are connected not just to the 1967 occupation but also to the broader

conflict (see Mendel 2013: 56).

My particular interest here is the ways in which this reality of Arab-Jewish division

sits alongside a dynamic of blurred separation in the city, where Palestinian and Israeli

space variously intermingles and overlays each other, forging an uneasy coexistence of

sorts. Certainly, compared to the violence of the second Intifada (20005), which saw

Arabs and Jews retreat into their separate quarters, present-day Jerusalem is character-

ized by a tentative, albeit asymmetrical and uneven, mixing as Palestinians and Israelis

encounter each other more often in the urban fabric of the city. This, of course, is shaped

by the varying regimes of dispossession and inequality that structure both the city and

Israeli planning policies, something quite often (and quite rightly) pointed out by critics

of various persuasions. Nevertheless, and as is my point of departure here, such regimes

not only have unintended consequences that work against their underlying rationales, but

also are never complete in the sense that they can do away with that they seek to ostracize

(see also Busbridge in press). I take my inspiration from the idea of the frontier as a site

of both contest and contact (Cavanagh 2011: 158). To emphasize only the former, as is

often done in critical accounts of Jerusalem, is to reduce the frontier from a zone of

encounter and interaction to [merely] a zone of conflict (Rose and Davis 2005: iv) and

is also to miss some of the more subtle and arguably hopeful elements of the contem-

porary city. As much as encounters cannot help but be shaped by the violence of the fron-

tier, it is the possibilities of interaction and the reality of tentative coexistence that offers

slivers of hope in an otherwise bleak landscape.

If Jerusalem reveals all that is most dysfunctional about the Israeli-Palestinian con-

flict, then, it is also in Jerusalem that the increasingly intertwined lives, histories and

experiences of Israelis and Palestinians are most evident (e.g. Bashir 2011). It is the

impossibility of disentangling Israeli and Palestinian space that I aim to document here

through both text and image. In doing so, I make a call for a politics of co-presence in

Jerusalem. In contrast to the never-ending search for roots and the desire for ethnically-

pure spaces, this politics of co-presence seeks the more hopeful possibilities that lie at the

interstices of blurred separation and uneasy coexistence. The only viable choice left for

Jerusalem, I suggest, lies in the acknowledgement of the complexity of Palestinian-

Israeli encounters, as well as their long and intertwined histories in and connections to

the city which is now incontrovertibly and unavoidably both Arab and Jewish.

Borders and frontiers in Jerusalem

Despite its claim to be an ancient and eternal holy city, metropolitan Jerusalem is in

fact a thoroughly modern creation and a particularly strange one at that. The borders of

what is now known as Greater Jerusalem seemingly make little sense: in the east, they

78 Thesis Eleven 121(1)

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

are largely marked by the walls, barriers and checkpoints that supposedly separate the

city from the West Bank; in the west, they fold out to the various red-roofed satellite

towns that dot the hills on the way to the plains of Tel Aviv (Figure 1). As Yonatan

Mendel describes, Jerusalems

. . . boundaries extend far beyond its population centres, encompassing dozens of villages,

barren hilltops, orchards and tracts of desert, as well as new-build suburbs with scant rela-

tion to the historical city; in the north, they stretch up, like a long middle finger, nearly to

Ramallah, to take in the Old Qalandia airport, some 10 kilometres from the Old City walls,

and bulge down almost to Bethlehem in the south. (2013: 36)

For all its apparent randomness, however, a closer look at the city reveals a particular

logic to its urbanism and one which is arguably not that unusual in terms of its history.

Like the patchwork stone walls of the Old City, which speak to its razing and rebuilding

by successive conquerors, modern-day Jerusalem wears the marks of its most recent vic-

tor; namely, Israel in the 1948 and 1967 wars, and its enduring project to claim the city as

the capital of the Jewish state.

The 1947 United Nations Partition Plan (which sought to split Mandate Palestine into

an Arab and a Jewish state) originally slated Jerusalem as a corpus separatum interna-

tional city to be administered separately by the UN. The outbreak of war the following

year, however, saw the original plan abandoned. Zionist forces conquered half of the city

and Jerusalem was transformed into an Israeli west and a Jordanian-administered east,

Figure 1. Map of Greater Jerusalem 2011. Courtesy of Ir Amin.

Busbridge 79

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

partitioned by the 1949 Armistice Line (the Green Line, so-called because of the colour

of the pen used to draw it). Whereas the newly-established Israeli state formalized West

Jerusalem as its official capital in 1950, the east largely languished under Jordanian rule

as the Hashemite Kingdom sought to downgrade its status and also its Palestinian iden-

tity (see Shlaim 2000: 36). Its victory in 1967 saw Israel once again expand its control

over the city, militarily occupying East Jerusalem as well as the broader West Bank. Sub-

sequently, they enlarged East Jerusalems boundaries from the 6 sq km previously under

Jordanian administration

2

by an additional 64 sq km, incorporating and annexing some

28 West Bank villages, their orchards and fields as well as wide swathes of desert into

Jerusalems municipal limits (BTselem 2013a). In 1980, Israel enshrined in Basic Law

Jerusalem as its united and complete capital. For the rest of the world (including,

importantly, the Palestinians themselves), East Jerusalem is illegally occupied territory

and the status of West Jerusalem as the Israeli capital remains controversial.

In such a context, the Green Line as an administrative boundary between Israel as a

sovereign entity and the Palestinian territories it occupies has largely lost significance in

Jerusalem from the perspective of the Israeli state at least (Newman 2012: 253). In

some ways, the Green Line remains like a faint trace on the urban landscape of the city,

particularly where the differences between Palestinian East Jerusalem (al-Quds) and

Israeli West Jerusalem (Yerushalayim) are most evident. This is the case across Road 1 in

the centre of the city, which separates the Palestinian neighbourhood of Bab al-Zahra

outside the walls of the Old City from the Haredi (ultra-Orthodox Jewish) neighbour-

hood of Mea Shearim (Figure 2). Here, Jerusalem is experienced as two very different

urban spaces, each with its own tongue, script and aesthetics. East Jerusalem remains dis-

cernibly Arab, with its Palestinian majority population and landscape punctuated by

minarets and church towers; in Bab al-Zahra vendors tout coffee and kebabs, fruit and

Figure 2. Road 1, separating East Jerusalem (left) from West Jerusalem (right).

80 Thesis Eleven 121(1)

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

vegetables are sold in open-air markets and families relax in sheesha cafes (Figure 3).

West Jerusalem is unmistakably Jewish, visually more European and home to an increas-

ing religious Orthodox population who live in places like Mea Shearim, which is akin to

an insulated Eastern European shtetl (Figure 4).

Nevertheless, the Arab-Jewish separation that defines the city is far blurrier than is

often presumed to be the case, and as much as the east-west divide is both palpable and

meaningful, it should not be regarded simplistically. While it is common to imagine Jer-

usalem in terms of two different cities facing directly onto each other (e.g. Klein 2008),

instances of clear-cut separation like that across Road 1 are not only anomalous, but

largely illusory. The project to establish Jerusalem as the eternal and indivisible capital

of the Jewish state has rendered borders and boundaries equally spurious and tentative in

Jerusalem, not least because it entails an active process in which Israel must simultane-

ously make Jerusalem Jewish and curtail Palestinian claims to the city.

3

This twin

dynamic of Judaization and de-Arabization (Yiftachel 1999) is settler colonial in orien-

tation, in the sense that it is premised on the logic of the elimination of the native and the

acquisition of their land for exclusive ownership by the settler (see Wolfe 2006).

It is in this regard that understanding Jerusalem through the notion of the frontier is

valuable. While borders and boundaries are traditionally conceived of as lines separ-

ating sovereign territories (Newman and Paasi 1998), frontiers typically exist when a

state is taking possession of a territory, and therefore mark the expansion of state

sovereignty (Prescott 1987: 36). Frontiers are far more uneven than are borders, and are

asymmetrically tipped towards those doing the advancing. In Jerusalem, to frame the city

through the east-west paradigm, or the framework of Israel versus Palestine, is to only

tell part of the story. As is the case across Israel-Palestine more generally, the expansion

of borders in Jerusalem has resulted in Palestinian loss of land, displacement and

Figure 3. On the way to Friday prayers. Old City, East Jerusalem.

Busbridge 81

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

dispossession by virtue of Israels ethnic-exclusive definition as a Jewish state, which

requires a Jewish demographic majority and entails differentiated rights for Jews and

non-Jews. It is this settler colonial reality, and the various land, immigration, settlement

and military policies that it entails, which has created a highly asymmetrical, segregated

and stratified political geography in the contemporary city (Yiftachel 1999).

If the notion of the frontier points to the colonially-rooted unevenness and inequality

that shapes Jerusalem, it also speaks to something critical about the relations between

Israelis and Palestinians that constitute the human weave of the citys urban geography.

As I have emphasized earlier, the frontier is a site of violence, replacement and nation-

building (Evans 2009), and as such it is the place in which opposing identities appear

irreconcilable the battle at the frontier is, after all, a battle of life-and-death. Nonethe-

less, frontiers are porous and sometimes largely imaginary spaces, where intergroup

relations [are] marked even in conditions of unequal power by negotiation and

exchange as well as coercion and violence (Elkins and Pederson 2012: 2). The reality

of the frontier as equally a place of encounter perhaps portends to alter the identities

locked in conflict with each other, or at the very least blur them. Frontiers are never lin-

ear, formal or stabilized as we often imagine our social identities to be, but are rather

deep, shifting, fragmented and elastic spaces in which the distinction between inside

Figure 4. Jaffa Street, West Jerusalem.

82 Thesis Eleven 121(1)

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

and outside cannot be clearly marked (Weizman 2007: 4). Likewise, as much as settler

colonialism seeks the elimination of the native, seemingly making spatial coexistence

anomalous (Russell 2001: 2), indigenous presence is never totally eradicated (Evans

2009; see also Guha and Spivak 1988). At the frontier, the trace of the other is always

present.

What I see as most interesting about Jerusalem is the way in which the same settler

colonial logic of the frontier, and its deep inequality, has manifested in quite different

realities in both the east and west. It has also manifested in very different realities for the

citys Jewish population, which makes up 64 per cent of the citys nearly 800,000 res-

idents and is spread across the east and west, and the Palestinian population, which

stands at 36 per cent and is located almost exclusively in the east (BTselem 2012). On

the one hand, East Jerusalem is structured by the ongoing settlement enterprise with its

brutal but simple modus operandi: maximum land for Jews with minimum Arabs. In the

east, Palestinians find themselves pushed into ever-smaller spaces as more Israeli settle-

ments are established and more land is claimed for Jewish use: indeed, in East Jerusalem,

a mere 13 per cent is available for Palestinian construction and much of this is already

built up, while 35 per cent has been expropriated for Israeli settlements (UN OCHA

2011). West Jerusalem, on the other hand, is seemingly established as fully Israeli, and

yet urban space is largely constructed in such a way as to write out and over pre-1948

Palestinian history and replace Palestinian spaces with Jewish ones. Likewise, for all

efforts to maintain the Jewishness of West Jerusalem, the deliberate de-development

(Roy 1995) of the east has compelled an increasing Palestinian presence, even if only

a fleeting one. It is these different realities, as well as their underlying connective logic,

that I hope to elucidate in the remainder of this essay. Like the photographs themselves,

this exploration offers merely snapshots. Yet, in first looking east then looking west,

I want to journey through modern-day Jerusalem to examine the logics and dynamics

of the city, as well as their transmutation into the realm of everyday life.

Looking east

For the most part, East Jerusalemite Palestinians who were unwillingly incorporated into

unified Jerusalem hold the status of permanent resident of the State of Israel, compared

to Israeli residents of Jerusalem who hold citizenship.

4

This status positions East Jer-

usalemite Palestinians akin to foreign nationals who have freely chosen to migrate to

Israel. As permanent residents, the main right afforded to Palestinians is the right to live

and work in Israel, although this is subject to a number of highly restrictive conditions

(see BTselem 2013a). Unlike citizens who may leave and return to the city at any given

time, permanent residents may have their status revoked should they spend too long

away from the city. Permanent residents have the right to vote in local municipal

elections but not elections to the Knesset (national parliament). Furthermore, permanent

residency status is not immediately handed down to ones children and, should one have

a non-resident partner, they must apply for a family unification visa if their partner is to

legally live in the city. For East Jerusalemite Palestinians, such conditions are exceed-

ingly difficult to negotiate. Not only are family unification visas, for instance, very rarely

granted, but they may be evicted from the city at any given time it is not unusual that

Busbridge 83

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

politically active East Jerusalemite Palestinians, especially those deemed security

threats, are expelled to the West Bank or the Gaza Strip.

This permanent resident status is rendered all the more tenuous by the various policies

to which Palestinians are subject by virtue of the occupation. As the Israeli human rights

organization BTselem (2012) states,

since East Jerusalem was annexed in 1967, the government of Israels primary goal in

Jerusalem has been to create a demographic and geographic situation that will thwart any

future attempt to challenge Israeli sovereignty over the city. To achieve this goal, the

government has been taking actions to increase the number of Jews, and reduce the number

of Palestinians, living in the city.

Jerusalem municipal policy identifies the ideal demographic balance in Jerusalem to

be 72 per cent Jews to 28 per cent Arabs (Halper 2009). In order to achieve this, the

municipality subjects Palestinians to a chaotic maze of planning policies, regulations and

restrictions intended to thwart their presence in the city a task accorded a particular

sense of urgency because of the high Palestinian population growth rate, which is only

rivalled by that of the Jewish Haredi (ultra-orthodox) community.

The settlement project plays an important role in establishing Israeli sovereignty over

the east side of the city, which has undergone a striking process of demographic

manipulation and urban transformation since 1967. This, as Eyal Weizman (2007: 256)

details, was laid out in the 1968 Jerusalem master plan, the first and cardinal principle

of which was to ensure [Jerusalems] unification by build[ing] the city in a manner that

would prevent its possibility of being repartitioned. Central to this was the establish-

ment of 12 remote Jewish neighbourhoods in East Jerusalem, which function as set-

tlement fingers reaching in and between Palestinians neighbourhoods and villages,

ghettoizing them and trapping their natural growth. The master plan also entailed the

construction of a second, outer ring of so-called settlement dormitory suburbs, which

were key to the expansion and enlargement of the citys boundaries to create Greater

Jerusalem. In order to weave together these disparately located settlements, a network

of roads and infrastructure have been established to create the city as an organic whole;

Road 1 mentioned above, for instance, connects the northern settlements of Pisgat Zeev,

Ha Givaa HaTzarfatit and Neve Yaacov to the southern settlements of East Talpiot, Gilo

and Har Homa (Pullan et al. 2007: 178). Presently, some 200,000 Israelis live beyond the

Green Line in East Jerusalem (BTselem 2012).

5

There are marked differences between Jewish and Palestinian areas. Palestinians pay

equal taxes to Jews, and yet receive only 912 per cent of the municipal budget (Margalit

2010) something that is quite evident in a brief tour of the city. Compared to Jewish

suburbs in both West and East Jerusalem, which are well-serviced and often green and

leafy (Figure 5),

6

Palestinian neighbourhoods in East Jerusalem are poorly serviced:

trash is not collected regularly and so is often burnt in the streets, roads and footpaths

are cracked or often not paved and infrastructure is limited and run-down (Figure 6).

BTselem (2011) reports that almost 90 per cent of sewerage pipes, roads and sidewalks

are found in West Jerusalem, with entire East Jerusalem neighbourhoods not connected

to the sewerage system at all; West Jerusalem has 1000 public parks, 24 swimming

84 Thesis Eleven 121(1)

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

pools, 26 libraries and 531 sports facilities, whereas East Jerusalem respectively has 45,

three, two and 33. Furthermore, Palestinian areas are typically dense and overcrowded,

due to a severe shortage of housing in the East Jerusalem Palestinian sector. While

new Jewish settlements pop up regularly, the municipality is reluctant to grant building

permits to Palestinians, which results in significant pressure for East Jerusalemite Pales-

tinian families (Halper 2009). On the one hand, the lack of building permits means that

Figure 5. Street in Rehavia, West Jerusalem.

Figure 6. Street in Silwan, East Jerusalem.

Busbridge 85

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

many families build illegally

7

and risk having their houses demolished; indeed, since

1967, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimates

that some 2000 Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem have been demolished, with as many

as 46 per cent of all homes currently deemed illegal by municipality zoning laws (UN

OCHA 2009). On the other hand, the artificial housing shortage has inflated prices to the

extent that many Palestinians are left with no option but to live in overcrowded conditions

or move to the West Bank where property is cheaper. This is a precarious decision consid-

ering that permanent residents must prove their continuing connection to the city or else

face revocation of their status; as such, many Palestinians who move to the West Bank will

keep a permanent Jerusalem address on which they continue to pay municipal taxes.

The so-called separation wall has arguably emerged as the dominant feature in the

urban fabric of East Jerusalem, with its 8-metre-high concrete blocks dwarfing Palesti-

nian roads, houses and buildings (Figure 7). While its construction began in 2002 as a

temporary security measure during the second Intifada, the wall is now a permanent

fixture in Jerusalem, and plays a key role in designating municipal boundaries and there-

fore Jewish-Arab demography in the city. Tellingly, the walls route incorporates the set-

tlements of the outer ring on the Israeli side while relegating some 55,000 Palestinian

residents of Jerusalem to the West Bank and leaving approximately 1600 West Banker

Palestinians inside the citys de facto boundaries (UN OCHA 2011). This absurd situa-

tion of selective separation means that one or two Palestinian houses may be cut off from

their village on the other side of the wall in a cynical calculation of land versus Arabs; at

times, the wall even divides villages and neighbourhoods in two, such as in Abu Dis, or

severs from the city outlying villages that previously relied on economic, social and

institutional connections to Jerusalem, turning them into ghost towns. This is the case

in Al-Ram (Figure 8), which lies just north of the citys municipal boundaries and is

Figure 7. The separation wall on the road to Ramallah, East Jerusalem.

86 Thesis Eleven 121(1)

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

home to 58,000 Palestinians, half of which hold permanent resident status (BTselem

2013b). Since the walls construction, several thousand have left to East Jerusalem and

Al-Ram has become an enclave: many shops and businesses have closed, and the village

is increasingly becoming the destination of choice for West Banker Palestinians exiled

from their homes and villages elsewhere, many of whom are criminals or drug addicts.

The dominance of the wall in shaping the everyday lives of Palestinians stands in con-

trast to its impact on Israeli settlers living in East Jerusalem. Not only does the walls

path better facilitate their integration into the city and serve to separate them from Pales-

tinian neighbourhoods, but it is typically landscaped where it snakes along Israeli areas

or is only visible in the distance (Figure 9).

As much as all Jewish Israelis living in East Jerusalem are considered settlers

according to international law, it is important to point out that the relations between

Palestinians and Israelis are variable. Some of the major settlement blocs like Maale

Adumim are exclusively Jewish gated communities; others, like HaGivaa HaTzarfadit,

see Palestinians and Jews living side-by-side, especially as rents and property prices

escalate in Palestinian neighbourhoods. Certainly, the vast majority of Israelis living

in East Jerusalem are considered quality of life settlers, attracted by the cheaper cost

of living and occasional government subsidies (Friedman and Etkes 2007). However,

a small proportion of settlers (about 2000) are motivated by religious ideology and have

established settler enclaves inside the Old City and its surrounding areas (the Holy

Basin), entering into a hostile relationship with local Palestinian residents. The form

these enclaves take is indicative of the haphazard, opportunistic and sometimes question-

able way in which properties are procured by the right-wing settler organizations that

organize them.

8

They may take the form of a building, a house, an apartment or some-

times just a single room, such as in the neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah where settlers

Figure 8. View from the other side (in Al-Ram).

Busbridge 87

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

have taken over the front room of a house while a Palestinian family continues to live in

the rest. In the Muslim and Christian quarters of the Old City, Israeli flags, surveillance

cameras and re-enforced steel doors mark Jewish settlements (Figure 10), which are

guarded by private security guards paid for by the government and Jerusalem Municipal-

ity (BTselem 2011). Palestinian residents are intimidated, harassed and sometimes

assaulted by settlers and settler guards alike, with the atmosphere of tension adding to

the militarization of the Old City which is patrolled by police and regularly closed in

response to violence in the West Bank or on Jewish holidays (Figure 11). For the

Figure 9. The Israeli settlement of Pisgat Zeev, East Jerusalem. In the background, the separation

wall; behind that, the Palestinian village of Anata and the Shuafat refugee camp.

88 Thesis Eleven 121(1)

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Palestinian shopkeepers who make their living from tourists (Figure 12), these condi-

tions have resulted in a lack of customers which, in conjunction with increasing munic-

ipal taxes, has led to the closure of at least 250 shops in recent years.

9

The Palestinian village of Silwan, which is located just underneath the Temple

Mount/Haram al-Shariff outside the walls of the Old City, demonstrates the ways in

which occupation, settlement and inequality intertwine in everyday life in East Jerusa-

lem, and also, importantly, how Palestinian and Israeli space overlay each other in a par-

ticularly uneven configuration. Here, a settler enclave has sprung up as part of an

archaeological dig: the City of David, believed to be the location of the biblical city

of King David from 3000 years ago. Taking advantage of archaeology as a means to

legitimize Israeli presence in occupied East Jerusalem (Abu-Haj 2007), the dig is run

by the settler organization Elad who, with the support of the Israeli government, have

deemed it a national park. There is in fact no way to separate the City of David from

Figure 10. Al-Wad Street, in the heart of the Muslim Quarter, Old City, East Jerusalem. The

Israeli flags mark a settlement.

Busbridge 89

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Silwan (Figure 13). The park sits in and runs through the heart of the neighbourhood,

archaeological digs take place under peoples houses (resulting in the collapse of some)

and a number of Palestinian residents have to cross through the park to go about their

daily activities: it is not unusual, for instance, for the Israeli school groups or soldiers

who visit the park as part of organized tours to run into a young girl on her way to school,

or an old man carrying his shopping back from the souq. Some 400 settlers live in prop-

erties incorporated into the park by Elad and receive municipal services that the local

Palestinians do not. While Silwan is one of the poorest villages in East Jerusalem, many

settlers live along newly paved, well-lit streets; indeed, when settlements front onto

Palestinian streets, newly-built footpaths absurdly end at the perimeter of their proper-

ties. With 80 houses in the al-Bustan neighbourhood slated for demolition to make way

for the Kings Garden, which will function as a natural corridor between the settle-

ments and West Jerusalem, it is not surprising that Silwan is one of the tensest areas

of East Jerusalem. Violence flares up sporadically, especially between settler guards and

local Palestinians, and stone-throwing youth frequently encounter tear gas and rubber

bullets shot by border police.

Looking west

Whereas the pressures of the occupation combined with the close quarters in which

Palestinians and Israeli often live make East Jerusalem a site of constant tension

threatening to spill over into violence, West Jerusalem for the most part escapes the

conflicts that structure daily life in the east. Public space is mostly Jewish, as is the

population, and West Jerusalem has solidified itself as the internationally acceptable (as

opposed to accepted) capital of the Israeli state. In many ways, West Jerusalem is a

microcosm of broader Israeli society and the city is home to the same social divisions

Figure 11. Israeli police checkpoint outside Damascus Gate. Old City, Jerusalem.

90 Thesis Eleven 121(1)

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

found across Israel. The citys Ashkenazi (Eastern European), Mizrahi (Arab), Ethiopian

and Russian Jewish populations remain largely segregated, frequenting ethno-specific

restaurants and nightspots; the migrant worker population, too, has its own public spaces

(albeit small), and one may see Nepalese or Filipinos gathering in West Jerusalems

malls and thoroughfares to informally celebrate their own cultural events and holidays.

The citys religious significance manifests in the masses of young diaspora Jews on

Taglit Birthright trips

10

who can be found filling its streets during the summer

months, joining religious Jewry from abroad on their yearly vacations, making the dis-

tinction between Jewish and Israeli particularly apparent. The purchase of properties

by French and American Jews in prime areas of the city, for instance, has driven up

prices and made a handful of neighbourhoods populated only during summer, which has

incited anger from Israeli-born Jerusalemites. However, the starkest division and the

one most dominant in West Jerusalem is that of religious/secular (Figure 14). Jerusa-

lems Jewish population is becoming increasingly religious, as the Haredi population

Figure 12. Shop selling to tourists in the Christian Quarter, Old City, East Jerusalem.

Busbridge 91

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

grows significantly and secular Israelis move to satellite towns outside the citys munic-

ipal limits (Alfasi et al. 2012). The contest between secular and religious Jews to shape

public space has most recently manifested in contentions over gender-segregation on

buses and the blacking out of images of women on billboards and advertisements.

11

While it may not be immediately evident, the conflict between Israel and the

Palestinians is nevertheless present in West Jerusalem, shaping its geography and

landscape as much as it does in the east. As Krystall (1998) explains, prior to 1948, the

Figure 13. City of David archaeological park, Silwan, East Jerusalem.

Figure 14. Graffiti, West Jerusalem.

92 Thesis Eleven 121(1)

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Palestinian community living in what was to become West Jerusalem numbered about

28,000 and was one of the most prosperous in the Middle East, living in often grand

residences in neighbourhoods like Qatamon, Baqa, Talbiyya and Musrara. Compared to

the 95,000 strong Jewish community which owned 30 per cent of West Jerusalem lands

in 1947, the West Jerusalemite Palestinian population owned 34 per cent (excluding the

Arab villages which were later incorporated into municipal limits) and typically rented to

Jews living in mixed neighbourhoods. With the outbreak of war, the vast majority of

West Jerusalem residents, Palestinian and Jewish, fled or were evacuated from their

homes. Palestinians living in villages on the outskirts, in particular, were targeted by

Jewish paramilitaries seeking to gain control over the citys entrance on the main road to

Tel Aviv. For instance, most residents of the village of Lifta which now stands largely

empty at the entrance to Jerusalem (Figure 15) left the village after a series of attacks in

late 1947, which resulted in seven deaths and a number of houses destroyed. Residents of

other villages were expelled in similar ways, or fled following the infamous April 1948

massacre of civilians at Deir Yassin by the Stern Gang and Irgun paramilitary organi-

zations. Upon the formal cessation of hostilities, Jewish residents were permitted to

return to their homes in West Jerusalem; Palestinians were not and their homes were re-

settled, mostly by new immigrants, but also by some Jewish families displaced from

Figure 15. Lifta, a pre-1948 Palestinian village now located in West Jerusalem.

Busbridge 93

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Jewish areas in East Jerusalem (such as Shimon HaTzadik). By 1948 the conflict had

manifested in such a way that all the neighbourhoods of Jerusalem except for the Jew-

ish Quarter in the otherwise Arab Old City were exclusively Arab or Jewish, with vir-

tually no communication between them (Krystall 1998: 9).

In addition to incorporating the vast majority of Jewish Jerusalem, with the exception of

a handful of enclaves on the east side like the HebrewUniversity on Mount Scopus, newly-

founded Israeli West Jerusalem also incorporated nine previously Arab villages and neigh-

bourhoods into its bounds. These Palestinian histories remain present in West Jerusalem,

as do many old Palestinian homes, even as they have been integrated into Israeli urban and

suburban spaces. Many of the houses of Deir Yassin, for instance, were incorporated into

an Israeli hospital for the mentally ill; in other places, it is not unusual to glimpse Arabic

writing above a doorway or a crescent on an old iron gate. A number of the former Pales-

tinian West Jerusalem neighbourhoods have been re-named as part of a process of Judai-

zation Talbiyya, for example, has formally become Komemiyut (even if it has failed to

catch on) and are highly sought-after real estate. Grand Arab residences are now mar-

keted as Beit Aravi (in Hebrew: Arab house) by Israeli real-estaters who emphasize their

authentic charm and character.

12

There are, however, a handful of sites that directly testify

to their Palestinian character and which are yet to be Judaized. Lifta is one such site, and is

in fact one of the few remaining Palestinian villages not demolished or re-populated with

Jews after 1948. Nevertheless, Liftas future presently hangs in the balance, with Israeli

developers seeking to turn the old Palestinian village into an exclusively Jewish luxury

resort, complete with 212 housing units, a hotel, a shopping mall and open green areas;

the mosque would be converted into a synagogue, with the old houses incorporated into

developments (see Busbridge in press).

Mamilla (Maman Allah) cemetery is another site in West Jerusalem that speaks to

the Palestinian history of many of its spaces (Figure 16). Located just outside the walls of

the Old City close to Jaffa Gate, Mamilla is the largest and most significant Muslim

cemetery in historic Palestine, having been in use since the seventh century and believed

to contain the remains of the Prophet Muhammads companions and warriors of Salah al-

Dins (Saladins) army (Makdisi 2010: 521). Since it was transferred to Israeli control in

1948, Mamilla cemetery has been progressively built over with a handful of carparks, and

most significantly, Independence Park, which is the second largest park in Jerusalem.

Currently, only a tiny portion of the once 50-acre-large cemetery is visible, albeit in a state

of disrepair: the area is overgrown with weeds, trash is strewn between the head stones and

tombs, which are themselves cracked and damaged. Controversially, a portion of Mamilla

cemetery is the site of the planned Museumof Tolerance in Jerusalem, which is intended to

be a great landmark promoting the principles of mutual respect and social responsibility.

Since construction was first announced in 2004, it has been suspended on a number of

occasions due to news breaking in 2006 that workers excavating had been discovering

and then disposing of human remains (Makdisi 2010). Despite widespread criticism,

as well as the withdrawal of various architects including Frank Gehry, who originally

designed the building, construction continues today, albeit hidden behind the tall silver

fence that surrounds the site and dominates what is left of Mamillas graves.

As mentioned earlier, Palestinians are becoming increasingly more visible in West

Jerusalems public spaces, although this presence is more transient than permanent.

94 Thesis Eleven 121(1)

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Whereas 200,000 Jewish Israelis live in settlements in East Jerusalem, very few

Palestinians are permanent residents in West Jerusalem and of these, the vast majority

are Palestinian citizens of Israel coming from Arab towns in the north. Original Jer-

usalemite Palestinians remain unable to return to or claim compensation for their

properties, despite a great many living only relatively short distances away in East

Jerusalem or the broader West Bank. Other Palestinians who may be interested in

purchasing property encounter a number of legal, bureaucratic and logistical hurdles that

make it effectively impossible;

13

likewise, Jewish landlords are typically reluctant to rent

to Palestinians, particularly in more conservative areas with strident anti-Arab senti-

ments. The Palestinians who are present are thus those who work in West Jerusalem,

which is in fact one of the few options available to East Jerusalemites who encounter

rampant poverty, unemployment and a severe lack of opportunities in that part of the city

(see UNCTAD 2013). The vast majority are in the construction and service sectors,

working variously as shop assistants, kitchen-hands, chefs, gardeners, construction

workers and street cleaners (Figure 17) thus literally engaged in the day-to-day servi-

cing and building of West Jerusalem.

Increasingly, East Jerusalemite Palestinians are opting to spend their leisure time in

West Jerusalem too. This is a particularly new development, albeit one also connected to

the occupation and the vast inequality that defines the east-west divide. On the one hand,

the construction of the Jerusalem Light Rail, which connects Israeli settlements in the

east with West Jerusalem, has made the west side of the city more accessible for Pales-

tinians. As much as the Light Rail entrenches the occupation insofar as it enacts the

Israeli claim to united Jerusalem (it is also illegal as a measure undertaken by an occu-

pying power to demographically-alter the territory it occupies), the train has emerged as

Figure 16. Mamilla cemetery, West Jerusalem. The fence at the back protects the site of the

planned Museum of Tolerance.

Busbridge 95

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

one of a few sites of tentative coexistence unthinkable only a handful of years ago. Here,

one can see Jews and Arabs sitting next to each other as equal patrons of the service, and

all stops are announced in Hebrew, Arabic and English (although it is perhaps significant

that many of the Arabic announcements are in fact Arabizations of Hebrew place

names). On the other hand, the lack of public spaces in the east, including cultural centres

and cinemas for example, means that many Palestinians choose to head to the west for

leisure activities. As the west side is rendered more accessible, more and more East Jer-

usalemite Palestinians are entering West Jerusalems shopping malls and strips, restau-

rants and cafes as consumers; likewise, groups of young Palestinian men are increasingly

choosing to congregate in parks or other public spaces in the west. The evidence of this

growing Palestinian presence in the west pops up in often surprising ways, such as

Palestinian-oriented graffiti, for example (Figure 18), but most stridently in terms of visi-

ble presence. While this has sometimes made for incidents of confrontation and violence,

with Palestinians typically the target of assault (in 2012, for instance, three Palestinian

youths were lynched by a mob of Jewish teenagers),

14

in most instances it has made for

a cautiously shared public space (Figure 19).

Re-imagining Jerusalems frontier

The project of re-imagining the frontier as a site of both contest and contact thus takes on

a particular urgency in Jerusalem: not only because the citys political future demands it,

but also because to think only in terms of the former is to miss something important

about the dynamics of the contemporary city. For me, what is most important about this

task is that it compels us to examine the unforeseen and unanticipated outcomes of the

settler colonial project, particularly when it comes to the question of relations between

Figure 17. Palestinian street cleaner, Ben Yehuda mall, West Jerusalem.

96 Thesis Eleven 121(1)

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

the parties respectively positioned as settler and native. The frontier, as I have sought to

examine and illuminate here, is a site of conflict, contestation and dispossession, but it is

also importantly that which binds the settler and native together. It is, to put it simply, the

Figure 19. Palestinian women sitting in Ben Yehuda mall, West Jerusalem.

Figure 18. Graffiti in West Jerusalem demanding the release of the East Jerusalemite Palestinian

hunger striker Samer Issawi. Issawi ended his nine month hunger strike in protest of the Israeli

practice of administrative detention in April 2013.

Busbridge 97

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

reality and hope of coexistence in settler colonial contexts, and the challenge herein is

how to transform relations at the frontier. Jerusalem in this regard is particularly instruc-

tive, not least because the formal settlement project is unlikely to ever be complete,

compared to, say, the settler colonial spaces of Australia and Canada where the defeat

and domination of the native was achieved through the violent reality of genocide. Israeli

hitnahulut (settlement), as Oren Yiftachel (1999) frames it, has not conquered Palesti-

nian sumoud (steadfastness); instead, the two are locked in a seemingly endless battle

with one other where neither is slated to emerge victorious. In contrast to the

claims of united Jerusalem or the desire to re-partition the city along ethnically pure

lines, Jerusalem speaks to the unavoidable reality that not only must Israelis and Pales-

tinians learn to live together, but that they already do. Much like the broader Israeli-

Palestinian conflict, east and west are not only bound together in Jerusalem but are

imbricated in each other. At the frontier of the city, it is thus the simple fact of presence

of both Arab and Jew that compels us to think beyond the twin fantasies of ethnic separa-

tion and exclusive ownership.

Notes

1. These are mostly ideologically-motivated settlers from the West Bank (including East Jerusa-

lem), or people connected to settler organizations.

2. Comprised of the Old City and a handful of outlying villages.

3. Indeed, Israel is not only one of the only states in the world without internationally recognized

borders, but it has expanded its borders on numerous occasions (Newman 2012: 252).

4. While Israel offers citizenship to East Jerusalemite Palestinians, it is refused by the majority of

the population for political reasons (i.e. taking Israeli citizenship recognizes East Jerusalems

annexation). Increasingly, however, more Palestinians are taking citizenship because of the

difficulties of living in Jerusalem as a permanent resident.

5. Adding to an additional 300,000 settlers living in non-annexed areas of the West Bank.

6. With the exception of Haredi neighbourhoods, which are typically quite poor.

7. Many structures built before 1967 are deemed illegal for not conforming to municipal reg-

ulations, making illegality an artifice. It is also important to emphasize that no Jewish homes

have, to date, been demolished in Jerusalem.

8. Settler organizations, like Ateret Cohanim which is active in the Old City, will sometimes

purchase properties in underhanded transactions with local Palestinians; other times, they will

occupy empty properties without permission from owners or even claim rooms in inhabited

properties, living alongside Palestinian families.

9. See Kestler-DAmours (2013).

10. Birthright Israel organizes free ten-day trips to Israel for young diaspora Jews, with the stated

aim of encouraging a sense of connection amongst world Jewry to Jewish heritage and history

in Israel.

11. See Reuters (2011).

12. See Prusher (2013).

13. All properties confiscated in 1948 were turned over to the Israel Land Administration (ILA) as

state land. Until 2009, state land could only be sold or rented to citizens of Israel or anyone

entitled to citizenship under the Law of Return (i.e. Jews in the diaspora), which automatically

excluded East Jerusalemite Palestinians, most of whom have the status of permanent resident.

While foreigners (a category which includes permanent residents) are now able to buy and

98 Thesis Eleven 121(1)

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

lease land from the ILA, they must nevertheless have the transaction confirmed by a special

committee and authorized by the ILA chair.

14. See Rosenberg (2012).

References

Abu El-Haj N (2003) Reflections on archaeology and Israeli settler-nationhood. Radical History

Review 86: 149163.

Alfasi N, Ashery SF and Benenson I (2012) Between the individual and the community:

Residential patterns of the Haredi population in Jerusalem. International Journal of Urban and

Regional Research 37: 21522176.

Bashir B (2011) Engaging with the injustice/justice of Zionism: New challenges to Palestinian

nationalism. Ethical Perspectives 18: 632645.

BTselem (2011) Settler enclaves in East Jerusalem. Available at: http://www.btselem.org/jer-

usalem/settler_enclaves (accessed 21 February 2014).

BTselem (2012) Background on East Jerusalem. Available at: http://www.btselem.org/jerusalem

(accessed 21 February 2014).

BTselem (2013a) Legal status of East Jerusalem and its residents. Available at: http://www.

btselem.org/jerusalem/legal_status (accessed 21 February 2014).

BTselem (2013b) The separation barrier surrounding A-Ram. Available at: http://www.btselem.

org/separation_barrier/a-ram (accessed 21 February 2014).

Busbridge R (in press) Haunted geography: Writing nation and contesting claims in the ghost

village of Lifta. Interventions.

Cavanagh E (2011) Review essay: Discussing settler colonialisms spatial cultures. Settler

Colonial Studies 1: 154167.

Dumper M (2013) Israel, Palestine and the Future of Jerusalem. New York: Columbia University

Press.

Elkins C and Pederson S (2012) Settler Colonialism in the Twentieth Century: Projects, Practices,

Legacies. New York and London: Routledge.

Evans J (2009) Where lawlessness is law: The settler-colonial frontier as a legal space of violence.

Australian Feminist Law Journal 30: 322.

Friedman L and Etkes D (2007) Quality of life settlers. Peace Now. Available at: http://peacenow.

org.il/eng/content/quality-life-settlers (accessed 21 February 2014).

Guha R and Spivak GC (1988) Selected Subaltern Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Halper J (2009) Obstacles to Peace, 4th edn. Jerusalem: ICAHD.

Kestler-DAmours J (2013) Isolation devastates East Jerusalem economy. Inter Press Service

News Agency, 26 May. Available at: http://www.ipsnews.net/2013/05/isolation-devastates-

east-jerusalem-economy/ (accessed 21 February 2014).

Klein M (2008) Jerusalem as an Israeli problem: A review of forty years of Israeli rule over Arab

Jerusalem. Israel Studies 13: 5472.

Krystall N (1998) The de-Arabization of West Jerusalem 194750. Journal of Palestine Studies

XXVII(2): 522.

Makdisi S (2010) The architecture of erasure. Critical Inquiry 36: 519559.

Margalit M (2010) Seizing Control of Space in East Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Sifrai Aliat Gag.

Mendel Y (2013) New Jerusalem. New Left Review 81: 3556.

Newman D (2012) Borders and conflict resolution. In: Wilson TM and Donnan F (eds) A

Companion to Border Studies. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Newman D and Paasi A (1998) Fences and neighbours in the postmodern world: Boundary

narratives in political geography. Progress in Human Geography 22: 186207.

Busbridge 99

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Prescott JRV (1987) Political Boundaries and Frontiers. London: Routledge.

Prusher I (2013) Israels absentee property law exposes an absence of morality in Jerusalem.

Haaretz Online, 7 June. Available at: http://www.haaretz.com/blogs/jerusalem-vivendi/

israel-s-absentee-property-law-exposes-an-absence-of-morality-in-jerusalem.premium-1.

528427 (accessed 21 February 2014).

Pullan W (2011) Frontier urbanism: The periphery at the centre of contested cities. The Journal of

Architecture 16: 1535.

Pullan W, Misselwitz P, Nasrallah R and Yacobi H (2007) Jerusalems Road 1. City: Analysis of

Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action 11: 176198.

Reuters (2011) Israelis take Jerusalems gender fight to buses and billboards, 14 November.

Available at: http://blogs.reuters.com/faithworld/2011/11/14/israelis-take-jerusalems-gender-

fight-to-buses-and-billboards/ (accessed 21 February 2014).

Rose DB and Davis R (eds) (2005) Dislocating the Frontier: Essaying the Mystique of the

Outback. Canberra: ANU e-Press.

Rosenberg O (2012) Israel police: Hundreds watched attempt to lynch Palestinians in Jerusalem, did

not interfere. Haaretz Online, 20 August. Available at: http://www.haaretz.com/news/national/

israel-police-hundreds-watched-attempt-to-lynch-palestinians-in-jerusalem-did-not-interfere-1.

459293 (accessed 21 February 2014).

Roy S (1995) The Gaza Strip: The Political Economy of De-development. Washington, DC:

Institute for Palestine Studies.

Russell L (2001) Colonial Frontiers: Indigenous-European Encounters in Settler Societies.

Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Shlaim A (2000) The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World. New York: W.W. Norton.

UNCTAD (2013) The Palestinian Economy in East Jerusalem: Enduring Annexation, Isolation

and Disintegration. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

UN OCHA (2009) The planning crisis in East Jerusalem: Understanding the phenomenon of

illegal construction. Available at: http://www.ochaopt.org/documents/ocha_opt_planning_

crisis_east_jerusalem_april_2009_english.pdf (accessed 21 February 2014).

UN OCHA (2011) Barrier update: Special focus. Available at: http://www.ochaopt.org/documents/

ocha_opt_barrier_update_july_2011_english.pdf http://www.haaretz.com/news/national/israel-

police-hundreds-watched-attempt-to-lynch-palestinians-in-jerusalem-did-not-interfere-1.459293

Weizman E (2007) Hollow Land: Israels Architecture of Occupation. London and New York:

Verso.

Wolfe P (2006) Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide

Research 8: 387409.

Yiftachel O (1999) Ethnocracy: The politics of Judaising Israel/Palestine. Constellations 6:

362391.

Author biography

Rachel Busbridge is an Alexander von Humboldt Postdoctoral Fellow at Institut fur

Islamwissenschaft, Freie Universitat, Berlin, and a Research Associate at the Centre for

Dialogue, La Trobe University, Melbourne. A political sociologist, her research interests

include the politics of recognition and reconciliation, culture, identity, nation and post-

colonial theory, which she has published on in the contexts of Israel-Palestine and

Australian multiculturalism.

100 Thesis Eleven 121(1)

by Pepe Portillo on June 29, 2014 the.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- So I'm A Spider, So What - , Vol. 12Документ253 страницыSo I'm A Spider, So What - , Vol. 12dslx4892100% (3)

- AC71630 2013 Training PDFДокумент202 страницыAC71630 2013 Training PDFKebede Michael100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- 14 Risk and Private Military WorkДокумент23 страницы14 Risk and Private Military WorkDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- 2 Knowledge in Idealistic PerspectiveДокумент10 страниц2 Knowledge in Idealistic PerspectiveDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- 6 Capitalist Class Relations, The State, and New Deal Foreign Trade PolicyДокумент27 страниц6 Capitalist Class Relations, The State, and New Deal Foreign Trade PolicyDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- 13 Resurrecting An Old and Troubling ConstructДокумент3 страницы13 Resurrecting An Old and Troubling ConstructDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- 2 Embodied Relationality and Caring After DeathДокумент27 страниц2 Embodied Relationality and Caring After DeathDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- 8 Foucault and RealityДокумент24 страницы8 Foucault and RealityDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- 16 A Visceral Politics of SoundДокумент18 страниц16 A Visceral Politics of SoundDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- Capital & Class: Farewell JohannesДокумент12 страницCapital & Class: Farewell JohannesDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- Capital & Class: Myths at WorkДокумент4 страницыCapital & Class: Myths at WorkDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- 4 A Profit-Rate Invariant Solution To The Marxian Transformation ProblemДокумент37 страниц4 A Profit-Rate Invariant Solution To The Marxian Transformation ProblemDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- 22 The Political Economy of New SlaveryДокумент4 страницы22 The Political Economy of New SlaveryDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- Capital & Class: A Last WordДокумент3 страницыCapital & Class: A Last WordDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- Alcohol and Dating Risk Factors For Sexual Assault Among College WomenДокумент25 страницAlcohol and Dating Risk Factors For Sexual Assault Among College WomenDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- 6 The Oldest System-Programme of German Idealism'Документ2 страницы6 The Oldest System-Programme of German Idealism'DaysilirionОценок пока нет

- 13 The Engineered and The Vernacular in Cultural Quarter DevelopmentДокумент21 страница13 The Engineered and The Vernacular in Cultural Quarter DevelopmentDaysilirionОценок пока нет

- CastroДокумент51 страницаCastroytyОценок пока нет

- 201311703Документ68 страниц201311703The Myanmar TimesОценок пока нет

- RaulGonzalezSal 2022 Chapter3JewishSoldier MilitaryServiceAndTheДокумент61 страницаRaulGonzalezSal 2022 Chapter3JewishSoldier MilitaryServiceAndTheJULIO TORREJON CASTILLOОценок пока нет

- Briefing On United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC)Документ5 страницBriefing On United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC)akar PhyoeОценок пока нет

- Famele Domestic VioleceДокумент14 страницFamele Domestic VioleceAde AdriiОценок пока нет

- Rank Modification PDFДокумент19 страницRank Modification PDFjoeresОценок пока нет

- t901 White PaperДокумент6 страницt901 White Papers.azad445599Оценок пока нет

- 918BJMAДокумент18 страниц918BJMABertrand SebastienОценок пока нет

- Teachers Guide Lesson Plan Cold WarДокумент18 страницTeachers Guide Lesson Plan Cold Warapi-235491175Оценок пока нет

- Conman Systems PDFДокумент2 страницыConman Systems PDFGajanand GoudanavarОценок пока нет

- YA MWH-B HOMEWORK #09 - Hot Wars During The Cold WarДокумент2 страницыYA MWH-B HOMEWORK #09 - Hot Wars During The Cold War3vadeОценок пока нет

- Sample Question Paper ULET 2023Документ1 страницаSample Question Paper ULET 2023craftystuff6Оценок пока нет

- Sourdin, Alternative Dispute ResolutionДокумент16 страницSourdin, Alternative Dispute ResolutionsimahenyimpaОценок пока нет

- Mark XIIA Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) Mode 5Документ4 страницыMark XIIA Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) Mode 5joma11Оценок пока нет

- Regime Survival Strategies in Zimbabwe After IndependenceДокумент12 страницRegime Survival Strategies in Zimbabwe After IndependenceAlihan AksoyОценок пока нет

- PI Motion-MainДокумент41 страницаPI Motion-MainDaleSaranОценок пока нет

- Encyclopedia of The Boer War Martin Marix EvansДокумент807 страницEncyclopedia of The Boer War Martin Marix EvansAbdel Guerra Lopez100% (1)

- Territorial Disputes in The South China SeaДокумент21 страницаTerritorial Disputes in The South China SeaSirJhey Dela Cruz100% (1)

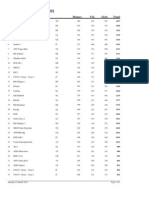

- Score Overall Team NISC 2011Документ2 страницыScore Overall Team NISC 2011AVRM Magazine StandОценок пока нет

- Conflict Resolution by Elders Successes Challenges and Opportunities 1Документ21 страницаConflict Resolution by Elders Successes Challenges and Opportunities 1Firakiyya KadiimОценок пока нет

- Helio Lancer Reference Sheet v1Документ2 страницыHelio Lancer Reference Sheet v1wwudijwdОценок пока нет

- Aero India Startup Manthan 2021Документ18 страницAero India Startup Manthan 2021Mansoor MasoodОценок пока нет

- 80 Set Questions For Practice-3Документ272 страницы80 Set Questions For Practice-3SANKAR VОценок пока нет

- 11chap08 PDFДокумент12 страниц11chap08 PDFDan Stefan DanОценок пока нет

- Exercise 1: Add One Missing Letter in Each WordДокумент5 страницExercise 1: Add One Missing Letter in Each WordNgọc ĐậuОценок пока нет

- Port Game 2021Документ5 страницPort Game 2021ASRIL KAHFI0% (1)

- English Grade 10Документ3 страницыEnglish Grade 10Uploader101Оценок пока нет

- Pratiyogita Darpan June 2023Документ171 страницаPratiyogita Darpan June 2023saikat.onergy2Оценок пока нет