Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Conflicts. Socialist Mass Housing

Загружено:

Andrius RopolasОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Conflicts. Socialist Mass Housing

Загружено:

Andrius RopolasАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CONFLICTS.

SOCIALIST

MASS

HOUSING

Shrinking population in socialist mass housing areas in Eastern Europe

by adapting Japanese methods and Asian conditions.

Andrius Ropolas

Tokyo / Brussels

2014

Master Dissertation Project

Conficts. Socialist mass housing

Andrius Ropolas

Supervisors

Ohno Hidetoshi / Bruno Peeters

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Faculty of Architecture

International Master of Science in Architecture, Campus: Brussels

/

The University of Tokyo, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences

Ohno Lab

2014

Funded by the AUSMIP grant

ausmip.org

andrius.ropolas@gmail.com / andrius.ropolas.eu

4 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank all people who helped during this

research. First of all professor Hidetoshi Ohno for his ad-

vises and tolerance when I was occupying his precious time.

Bruno Peeters for his calming tone and in depth responses

from Brussels. Friends from Bulgaria, Poland, Romania who

helped me understand better the common issues of social-

ist housing areas in Eastern Europe. Friends from Korea,

China and Japan who helped me to orientate myself through

Asian context. My sister who was my eyes in a local context.

And all others who helped by having shorther or longer

dicussions about the research.

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

5

6 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

7

ABSTRACT

Shrinking population is a rarely discussed issue in Eastern Europe. However the

statistics reveal that this region is one of the main hot spots for shrinkage. This

paper suggests that socialist mass housing areas in smaller Eastern European cit-

ies will be greatly affected by shrinkage. As a way to fnd strategies and defne a

mindset it is proposed to look at a specifc urban conditions in Asia as a result of

rapid urbanization, which was also the driving force behind socialist mass hous-

ing areas. The experience of working with shrinkage in Japan is greatly support-

ing the paper.

The complexity of shrinkage and specifc socialist heritage issues are discussed

through the spatial conficts of socialist mass housing areas. Main identifed

conficts are between private and public, city and countryside, past and present.

This approach on conficts tries to bypass huge amount of existing problems and

to tackle directly their reasons. The goal is to fnd an answer if we need to solve

these conficts and how it can be done.

The paper concludes with main points on how to rebalance existing spatial

conficts. The key points are - privatization of vast green spaces, creation of fber

structures and reconfguration of spatial characters of the areas. Paper suggests

that it is not necessary to solve spatial conficts, but instead - rebalance them.

This should start a chain reaction and problems would solve themselves.

8 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4

ABSTRACT 7

INTRODUCTION 11

SOCIALIST MASS HOUSING LINK WITH

ASIAN MASS HOUSING 12

BACKGROUND OF SOCIALIST MASS HOUSING

AREAS AND ALTERNTIVES IN ASIA 19

URBANIZATION OF THE SOVIET UNION 20

The roots - Constructivism 20

Prefab mass housing units khrushchevki 24

Urban surfaces micro-districts 28

CONDITIONS IN ASIA 32

Tokyo - land readjustment 32

Hong Kong - green contrast 34

Seoul - gated communities 36

Shenzhen - green boundaries 38

SHRINKING EASTERN EUROPE

AND LEARNING FROM SHRINKING JAPAN 43

COMMON DENOMINATORS IN

EASTERN EUROPE 44

CONSEQUENCES OF SHRINKING

EASTERN EUROPE 50

LEARNING FROM SHRINKING JAPAN 52

Fibercity 52

CONFLICTS IN SHRINKING

EASTERN EUROPE 54

The complexity 54

1. Confict between private and public 56

2. Confict between past and present 58

3. Confict between city and countryside 60

POSITIVE ELEMENTS OF SOCIALIST

MASS HOUSING 62

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

9

SOLVING CONFLICTS IN

SOCIALIST MASS HOUSING AREAS 65

DO WE NEED TO SOLVE CONFLICTS IN

SOCIALIST MASS HOUSING AREAS? 66

BORDERS 67

EDITING FIBERS 68

Fibers 68

Private and public 70

City and countryside 72

Past and present 74

LIMITATIONS 76

CONCLUSIONS 79

IN SEARCH FOR

THE DIAGRAM OF EVERYTHING 80

POST-SOCIALIST FIBERCITY 81

RESEARCH CONCLUSIONS 82

BIBLIOGRAPHY 86

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 89

10 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

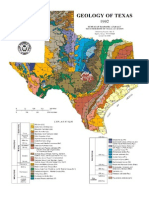

Figure 1. Shrinking cities. Based on Atlas of Shrinking Cities

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

11

INTRODUCTION

First part presents overall issues and goals of the research. It

introduces a global shrinkage issue, tendencies, the hotspots

and the relevance of socialist mass housing areas.

12 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

Industrialization did not only cause fast economic and urban growth,

it also enabled unprecedented process of shrinkage (Rieniets, 2011)

FOCUS OF THE RESEARCH

T

his research will try fnd common critical points for

socialist mass housing areas in Eastern Europe in the

time of shrinkage. They should give theoretical mindset for

practical actions which would be based on interpretation of

Asian conditions and solutions. The theoretical and practical

background of the Ohno Lab studies at The University of

Tokyo on Fibercity will be used as a possible starting point

for solutions.

The research is focusing primarily on conditions of second

biggest (or comparable size and importance) cities of the

Eastern European countries. Processes happening in capi-

tals might be very different, shrinkage might be much small-

er or even not meaningful and this research does not try to

cover these situations. Although the goal is to fnd common

solutions and research generic aspect of the socialist mass

housing areas. A specifc Dainava mass housing area from

Kaunas, Lithuania will be used to illustrate theoretical fnd-

ings. This area will be later used as a project design case to

test practical solutions. This specifc area was chosen as an

example which could represent processes in most of Eastern

Europe the best based on statistical reasons:

Shrinkage in Lithuania (-19,61%) next 50 years is very

close to an average of Eastern Europe (-21,36%) (United

Nations, 2012).

Second biggest city of Lithuania, Kaunas is losing its

population (-23% during 2001-2013 period) (Statistics

Lithuania, 2013).

Dainava mass housing area is one of the frst to be built

in Kaunas (frst constructions dating back to 1963) with

biggest number of elderly (Kauno planas, 2013) and

with highest number of apartments currently for sale

per resident compared with all mass housing areas in

the city (based on aruodas.lt public listings).

In the end, there is no goal to solve all problems of the

shrinking cities in Eastern Europe, but focus on very im-

portant generic parts of the cities and few very specifc key

issues.

GLOBAL SITUATION

According to United Nations world population will increase

by 43,93% in 2060 compared with 2010, almost from 7 bil-

lion to 10 billion (United Nations, 2012). This simple num-

ber tells that we will need to build more, use more resourc-

es. However it is not quite true. When looking at particular

regions in more detail, we can notice that growth is not

spread equally throughout the world and some regions will

experience shrinkage. This means that new problems might

occur by keeping existing infrastructure to be effcient and

managing living environment to be pleasant and attractive.

Japan is one of the countries where population will shrink

the most 19.51% comparing 2060 and 2010 data (United

Nations, 2012).

Media often focus on Japan while talking about shrink-

age, however there is a bigger region in a world which faces

shrinkage at similar speed that is Eastern Europe. Shrink-

age in Eastern Europe is not an issue of few countries, but

all region. This gives an idea that there must some common

points among all countries. A total population of this region

climbs over 328 million people (United Nations, 2012)

and with decrease of -21.63% during next 50 years (United

Nations, 2012) this would mean a loss of over 70 million

people. A number equal to a total population of Poland, Bal-

tic States, Czech Republic, Serbia and Bulgaria combined.

Looking historically this region was a part of Eastern Bloc

where development ant politics were strictly controlled and

most things were based on standardization. Over half of

population in Eastern Europe lives in a socialist mass hous-

ing areas (Stanilov, 2007, p. 181) built during Soviet regime.

Naturally, shrinkage will greatly affect these areas. Of

course, as growing number of total population in the world

does not reveal the full story and we must look closer to fnd

shrinkage, same applies to Eastern European cities.

Looking at the future it is easy to notice that capitals in the

region can maintain population by attracting people from

the regions, however it is more diffcult situation for smaller

cities. Particularly in the case of Lithuania we can notice

that population of capital Vilnius in years 2001-2013 lost

only 3% of population, however second biggest city Kaunas

lost 23% during same period, while national loss was 15%

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

13

Figure 2. A map of population change in Europe during 2010-2060 period.

Based on Eurostat data.

Pluses represent countries growing more than 10%

Lines represent countries between -10% decline and 10% growth

Minuses represent countries shrinking more than -10% percent

Black solid line marks countries which were a part of Eastern Bloc

14 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

(Statistics Lithuania, 2013). That is why exploring second

biggest cities, like Kaunas, can give better understanding

and more useful answers to shrinkage in Eastern Europe.

Similar situations can be found in all Eastern Europe

region, meaning that it should be possible to fnd common

answers to common issues.

SOCIALIST MASS HOUSING LINK WITH ASIAN

MASS HOUSING

S

ocialist mass housing ideas in Eastern Europe were

copied by Soviet government from Western European

examples (Listova, 2009), but they had completely differ-

ent impact and purpose. Mass housing developments (with

more than 2500 units) in Western Europe never were a big

trend and now they takes only 3-7 percent of the market,

as compared to Eastern Europe where this number jumps

to 40-50 percent and where over half of population live

(Stanilov, 2007, p. 181). In Western Europe these areas were

seen as areas for less successful part of population, where in

Eastern Europe they were built as a houses for masses. They

did not focus on particular part of society as everybody had

to be equal under communist ideology. Even today when

mass housing areas in Western Europe are seen as prob-

lematic places, as possible ghettos for immigrants while

picture in Eastern Europe is completely different. Due to

low number of immigrants, socialist areas house most of the

population in Eastern Europe without any particular social

order. However it is worth noting that it is slowly changing

and residents in those areas are becoming less wealthy and

misbalance starts to appear.

In Asia housing areas have completely different history

than in Eastern Europe. They also often have some specifc

development differences due to specifc contexts. However,

like in Eastern Europe, mass housing areas in Asia are seen

as a normal part of society where people live without any

specifc social status. In some places, like Hong Kong it is

diffcult to imagine a life not in an apartment building as

they are the only possibility for Hong Kong to sustain its

population. Rapidly growing population in Asia was and in

some parts still is the main factor for building vast apart-

ment housing areas. Same reasons were in Soviet Union

where urban population started growing immensely in the

beginning of 20 century. Although Soviet Union started

their housing experiments in early 20 century, the biggest

construction boom in Soviet Union came later to the middle

of the century. In Japan, South Korea and Hong Kong con-

struction boom started around the same time as in Soviet

Union. And, interestingly, the decline of rapid population

growth, as in Soviet Union, in South Korea and Japan came

at the same time too around 1990.

China, on the other hand, started growing a little bit later.

As China had close political and ideological ties to Soviet

Union, they applied some already tested methods from

Soviet Union to their planning system (Bruton et al., 2005,

p. 229). However it is important to notice that soon China

started adapting those methods and created new conditions.

This evolution can be found by exploring the urban history

of Shenzhen.

Another interesting relation is purely visual. The visual

similarity of the housing blocks in Seoul and post-socialist

countries is striking. Two completely different economic and

political systems around the same time produced visually

very similar solutions.

Similar thing can be noted while talking about repetitive-

ness of housing blocks in Hong Kong. The socialist mass

housing features like copy-pasted balconies, windows, build-

ings are brought to a level where it becomes a dominant fea-

ture of city landscape, cannot be unnoticed in Hong Kong.

Here, again in different political and economic system, the

continuous repetitiveness has similar visual importance in

both natural and urban landscapes.

It is worth understanding background of housing block de-

velopments in Asia more, as they can reveal some meanings

and solutions for socialist mass housing areas in Eastern

Europe. Undoubtedly, after further research it will be pos-

sible to see socialist mass housing areas in Eastern Europe

in different, wider perspective.

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

15

Figure 3. Construction of Capsule Tower. Kisho Kurokawa visited Soviet

Union to fnd out more about prefabricated construction.

Figure 4. A construction of a typical socialist apartment. Picture by Stan

Wayman, 1963.

Figure 5. Seoul Figure 6. Shenzhen Figure 7. Moscow

16 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

Population projections

geo\time 2010 2060 Change

Serbia 9.647.000 6.297.000 -34,73%

Ukraine 46.050.000 30.859.000 -32,99%

Belarus 9.491.000 6.832.000 -28,02%

Bulgaria 7.563.710 5.531.318 -26,87%

Latvia 2.248.374 1.671.729 -25,65%

Georgia 4.389.000 3.417.000 -22,15%

Eastern Europe 296.183.000 232.927.000 -21,36%

Russia 143.618.000 115.023.000 -19,91%

Lithuania 3.329.039 2.676.297 -19,61%

Japan 127.353.000 102.507.000 -19,51%

Romania 21.462.186 17.308.201 -19,35%

Germany 81.742.884 66.360.154 -18,82%

Poland 38.167.329 32.710.238 -14,30%

Estonia 1.340.141 1.172.707 -12,49%

Hungary 10.014.324 8.860.284 -11,52%

Europe 740.308.000 690.622.000 -6,71%

Malta 412.970 387.422 -6,19%

Slovakia 5.424.925 5.116.496 -5,69%

Portugal 10.637.713 10.265.958 -3,49%

Czech Republic 10.506.813 10.467.652 -0,37%

Greece 11.305.118 11.294.664 -0,09%

Slovenia 2.046.976 2.057.964 0,54%

Netherlands 16.574.989 17.070.150 2,99%

EU (27 countries) 501.044.066 516.939.958 3,17%

Austria 8.375.290 8.868.529 5,89%

Liechtenstein 35.894 38.328 6,78%

Finland 5.351.427 5.744.452 7,34%

Italy 60.340.328 64.989.319 7,70%

Denmark 5.534.738 6.079.838 9,85%

Spain 45.989.016 52.279.310 13,68%

France 64.714.074 73.724.251 13,92%

Switzerland 7.785.806 9.319.289 19,70%

Sweden 9.340.682 11.525.240 23,39%

Belgium 10.839.905 13.445.216 24,03%

United Kingdom 62.008.048 78.925.262 27,28%

Kazkhstan 15.921.000 20.541.000 29,02%

Turkey 72.138.000 95.331.000 32,15%

Norway 4.858.199 6.587.061 35,59%

Iceland 317.630 435.030 36,96%

Cyprus 803.147 1.134.460 41,25%

World 6.916.183.000 9.957.399.000 43,97%

Luxembourg 502.066 728.098 45,02%

Ireland 4.467.854 6.544.749 46,49%

Figure 8. United Nations and Eurostat data

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

17

18 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

Figure 9. Construction of a socialist mass housing area

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

19

BACKGROUND OF SOCIALIST MASS HOUSING

AREAS AND ALTERNTIVES IN ASIA

This chapter covers the background of socialist mass hous-

ing areas by exploring urban and architectural origins. At

the same time urbanization of Soviet Union is compared

with urbanization in Asia. Several specifc condition from

Tokyo, Hong Kong, Seoul and Shenzhen are explored as a

possible alternatives for socialist mass housing areas.

20 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

URBANIZATION OF THE SOVIET UNION

U

rbanization which took place in Soviet Union was the

most intense at that time in the world. During the

most rapid period from 1926 to 1939 the urban population

more than doubled reaching 55.9 million, while in U.S. for

urban population to double it took 30 years and in UK 70

years (Pokshishevskiy, 1980, p. 35). Impressive statistics con-

tinued as in 30 years period from 1955 to 1985 ffty million

new apartments were built (Goldhoorn and Sverdlov, 2009).

Also worth to mention that between 1956 and 1964, just

in 8 years, quarter population of Soviet Union (54 million

people) moved to new apartments (Bronovitskaya, 2009,

p. 24). In Russia alone the urban population from 1926 to

1989 grew by 56% (Becker et al., 2012, p. 6) and in all Soviet

Union urban population from 1917 to 1982 grew from 16%

to 64% affecting 146 million people (Yanitsky, 1986, p. 265).

All these numbers tell one simple thing - Soviet Union had

to take a new approach to urbanization and architecture to

cope with its changing society during the 20th century. This

meant experimentation, failure and arguable success.

THE ROOTS - CONSTRUCTIVISM

In early days of the Soviet Union, one of the most interest-

ing architectural movements at that time, constructivism

was born. Constructivists had a strong relations with artists,

but at the same time their architecture was oriented towards

Communist partys embraced social politics: Their inno-

vations were useful to a revolutionary regime in need of a

dynamic visual language to promote communism (Bradley

and Esche, 2007, p. 402).

Discussions started to fnd the most appropriate urban form

for the communist society, but common opinion was dif-

fcult to reach. The opinions dived in two camps urbanist

and de-urbanist schools (Bater, 1980, p. 22). Most of their

proposals were utopian and speculating on infnite budgets,

but their ideas later laid foundations for a socialist cities.

Urbanists were infuenced by Garden city concept (How-

ard, 1902) and Le Corbusiers theories, although the link is

not completely direct (Bater, 1980, p. 23). On the other side,

de-urbanists were very radical and wanted an essentially

townless socialist society in which age-old contradiction

between town and country would be abolished once and

for all. (Bater, 1980, p. 23). Their idea was to spread people

around the country based on linear urban forms and com-

pletely forget the concept of the city.

Radical urban concepts were not realized, but some radical

experiments on architectural scale did see the light. Among

them - projects where constructivists tested their ideas on

a new life style of a proletariats. The best known example

of a new ideology is a Narkomfn building. Here architects

of the project Moisei Ginzburg and Ignaty Milinis tried

not only to promote new type of architecture celebrating

new technology of reinforced concrete, but also to address

an urban challenge create a social environment in the

city (Ghazali, 2007). This was an important issue having in

mind new political direction and increasing industrialization

which was followed by urbanization. Main concept of the

building was a total separation of individual sleeping cells

from a common spaces. It was probably the most interesting

example at that time which used standardization as a tool to

create new urban condition. According to a new ideologies,

residents had only small, 6 square meters for two people,

individual cells for sleeping and all other activities had to

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

21

Figure 10. Ivan Leonidov Magnitogorsk Proposal (1930)

Figure 11. Ivan Leonidov Magnitogorsk Proposal (1930)

22 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

be common, shared with all other residents (Prevost and

Dushkina, 1999, p. 9). Women were freed from cooking as

everybody were eating at a canteen, children could spent

their time in kindergartens. Big corridor had to replicate a

village road and the confguration of a program had to en-

able social experience. Overall, it was an attempt to remodel

the concept of the traditional family and propose a com-

munistic lifestyle, where society is your family. Narkomfn

model shows frst attempts of government to control society

using architecture, a belief of architects that architecture can

shape new model of people which later was proved to be an

utopia (Smirnov, 2011).

Around the same time when Narkomfn project was com-

pleted (1932), other architects and engineers were working

on exploring possibilities of standardization by using prefab

blocks and prefab dwelling cells. However after change in

politics of the Soviet Union, when Stalin came in power in

1930s, constructivism was undesirable. Changed concept

of society also changed the ideology of architecture - from

avant-garde it turned to imperialistic Stalinist expression

with interpretations of antique motives. Although archi-

tectural expression was suppressed, the investigations on

standardization continued: At the Institute of Architecture

in Moscow, Burov continued to investigate large-panel

construction and eventually laid the technological ground-

work for the architecture of the post-war-era (Urban,

2013, p. 12). After the ruling of Stalin, the approach to

society and naturally to architecture changed. New leader

Nikita Khrushchev heavily focused on modernization and

urbanization of Soviet Union. Instead of nave, decorative

Stalinist expression, on 1954 December 7, he gave a speech

and promoted a new standardized mass housing program

(Khrushchev, 2009) which roots can be seen in some early

constructivist experiments.

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

23

Figure 12. Nikolai Milyutins plan for a Linear City.

Residential area (), industrial zones (). Railway running along.

Figure 13. Narkomfn building - one of the most famous examples of constructivist architecture, 1932

24 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

PREFAB MASS HOUSING UNITS KHRUSHCHEVKI

It is them [architects] who understand architecture as a

decorative art rather than means of satisfying material needs

of soviet people. It is them who waste the funds of soviet

people on beauty which nobody needs, instead of building

simpler, but more (Listova, 2009) it is this speech where

in 1954 Nikita Khrushchev drew a new direction for archi-

tecture and urbanization in Soviet Union. After it, architects

became less important and architecture had one simple goal

to be cheap.

In 1939 the average space per person in Soviet Union was 5

square meters. When Krushchev came in power in 1953, the

standard apartment size by frst mass prefab house model

K-7 was based on the concept of the minimum (which was

also the maximum) 9 square meters per person. (Strelka In-

stitute of Media, Architecture and Design, 2012a). It meant

that one room apartment with all facilities was around 30

square meters, two rooms 44 m2, three rooms - 61 m2

(Resog, 2014). For a lot of people these apartments were

frst personal property in their life and often frst urban

experience, as a lot of people came directly from villages.

The speed and low quality of construction was an outcome

of a tight economic pressures and political program. There

are records of 5 story houses built in 5 days, but quality of

them is unknown (Listova, 2009). First mass fve story hous-

ing K-7 could be built in 45 days 15 days mounting prefab

pieces and 1 month for interior fnishing (Listova, 2009).

Due to extremely low quality of K-7 model, where engineers

proposed 4 centimeter thickness of inner walls and only 8

centimeters for walls between apartments, the structure was

later updated to suit the needs of people better. Bigger and

more comfortable apartments had to accommodate people

better. To ensure that, the frst residents of new prototype

housing had visits from specialists of housing typology who

checked the apartments to see how the residents inhabited

the space. Although apartments improved, they still did

not suit the needs of the people well, because the habits of

people were not so easily predictable.

Today most of these buildings are in poor condition. First

houses (type K-7) now are being widely demolished in Mos-

cow (Complex of urban policy and construction in Moscow,

2014) , but improved house models (like I-464A) have a

theoretical 100-125 years lifespan (Ruseckas et al., 2009, p.

26) and make up a very important part of a residential mar-

ket in Eastern Europe.

It is them [architects] who under-

stand architecture as a decorative art

rather than means of satisfying mate-

rial needs of soviet people. It is them

who waste the funds of soviet people

on beauty which nobody needs, in-

stead of building simpler, but more

- Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Communist

Party of the Soviet Union, 1954 (Listova, 2009)

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

25

Figure 14. Construction of socialist mass housing area

Figure 15. Nikita Khrushchev

Figure 16. Prefab panel

26 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

Figure 17. 1-464A14-LT type used in Lithuania

Figure 18. 1-464-LI-15 type used in Lithuania

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

27

Figure 19. Fragment of the 1-464-LI-15 type used in Lithuania

28 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

URBAN SURFACES MICRO-DISTRICTS

Repetitive, downgraded architecture created very monotonic

urban environment micro-districts. This problem was

understood by the architects and builders as Valentin Galec-

kiy, organizer of the frst house building factory, has stated

that they saw the ugliness, but it was just the most effcient

and cheap method (Listova, 2009). Society also reacted to

these developments and repetitiveness was often mocked in

cinema and music (Rappaport, 1962; Ryazanov, 1975; Seryj,

1971). The most famous example in a movie Ironiya sudby,

ili s legkim parom! shows a man who managed to fnd

exactly the same as his apartment with the same door lock

in exactly the same street, but in the different city.

Micro-districts did not have urban elements developed

through centuries street perspectives, houses, squares,

intersections, boulevards. A border conditions where ex-

change happen (Sennett, 2011, p. 324) did not fnd place in

micro-districts. As typical example of modernist planning,

micro-districts were planned thinking of them as surfaces.

Therefore, each of the zones must be separated so that they

do not interfere with adjacent zones. (Ohno, 2004, p. 28).

Empty surfaces - landscapes were flled with grey concrete

blocks around Moscow and later all Eastern Bloc (Snopek,

2011, p. 33). Although in some cases local architects tried

to create more vibrant environment by constructing micro-

districts in a more scenic landscape (Lazdynai district in

Vilnius, Lithuania), they still lacked diversity.

On the other hand, strict scientifc planning arranged

public functions around the housing blocks in a convenient

distances. Schools, shops and pharmacies were maximum

10 minute distance from the apartments (Bronovitskaya,

2009, p. 24). Stadiums, hospitals, libraries and other facilities

were within a close distance, often in the centers of micro-

districts. Greenery during the time grew and also became

richer and inviting. These benefts of modernistic planning

are appreciated even today as new generation of residents

who grew up there have more natural feeling to this type of

planning (Bronovitskaya, 2009, p. 25).

This adaptation means that socialist mass housing areas

eventually from forced lifestyle are turning to a lifestyle

which people choose because of specifc qualities, even if it

might seem uncomfortable for most of the people. Simi-

larly as people choose to live in boats in Amsterdam or in

fooded Venice.

We did not have rich architectural

elements, but just plain poor panels.

It was possible to do only them, not

because we were such idiots, but be-

cause it was possible to produce only

those type of panels in factories which

we already had, with their standard

equipment.

- Elena Kapustian, architect, advisor of Russian academy of

architecture and building science (Listova, 2009)

Figure 20. Elena Kapustian giving interview to a TV

programme Sovetskaja Imperia. Krushchevki.

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

29

Scientifcally calculated arrangements of functions in city and mass housing area. Gutnov and Baburob, 1971

Figure 21. Top - NUS in an agricultural zone.

Figure 22. Bottom - Plan of a NUS.

30 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

29.37 hectares

60.8% takes green spaces

over 600 trees

Coverage within 3 minutes from bus stop

5 foors, 9 foors, 12 foors

Informal path system

Commercial and public functions

Road structure

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

31

Figure 23. Opposite page - analysis of Dainava

micro-district.

Figure 24. Orthogonal drawing of Dainava micro-

district in Kaunas, Lithuania based on existing

situation. Dainava is one of the frst socialist mass

housing areas to be built in Kaunas with construc-

tions starting in 1963.

32 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

CONDITIONS IN ASIA

A

ccording to Asian Development Bank (2008) in next 20

years 1.1 billion people will move to the cities in Asia.

It is a unique shift in human history which is followed by

intense construction of cities. In 2011 there were 23 megaci-

ties (cities with population over 10 million) with 13 of them

being in Asia, by the 2025 world is expected to have 37

megacities and 22 in Asia (United Nations, 2011, p. 5). The

most standing out city in this sense is Tokyo which from

1950s is and will continue to be in the nearest future, the

biggest megacity. However Tokyo is not developing now at

extremes pace as it was until 1990s. Same can be said about

Seoul, which is now balancing on the limit of becoming a

megacity. Here population grew rapidly just after Korean

war in 1953 and slowed down around 1990 (Oh et al., 2009,

p. 16). However when Tokyo and Seoul slowed down Shen-

zhen started demonstrating incredibly rapid development

by growing population by 2 million every 5 years, which in

2020 should be over 14 million (United Nations, 2011, p.

222). But not only rapid growth and size is interesting while

talking about urbanization, density is also one of the key

factors. In this sense Hong Kong demonstrates examples of

extreme density with its Kwun Tong area reaching 56 200

people per square kilometer (Hong Kong Census and Statis-

tics Department, 2013a). This makes Hong Kong one of the

densest areas in the world ( Jenks and Burgess, 2003, p. 245).

This vast urbanization produced special conditions and

regulation forms which infuenced mass housing develop-

ment in those cities. In next sections several cases based on

impressions from study trips will be explored. It is impor-

tant to understand what is the background and meaning

of each context and what allowed or forced specifc urban

forms to take shape.

TOKYO - LAND READJUSTMENT

Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 was a disaster for Tokyo,

but at the same time it was a chance for rapid modernization

frst subway line opened in 1927 and Haneda airport in

1931. However history repeated itself and during WWII To-

kyo was heavily damaged once more. Reconstruction took

again. In both times land readjustment method was used for

urban reconstruction (Sorensen, 2000a, p. 52). Today land

readjustment is called The Mother of City Planning (So-

rensen, 2000b, p. 217), because 30% of urban areas in Japan

are arranged using this method. It was and still is a very

attractive concept because it can be self-fnancing model

of regeneration combining at the same time a lot of differ-

ent land owners. This model has a wide range of applicable

situations including public housing projects, railway, transit,

new town developments and etc. (Sorensen, 2000a, p. 53).

The really basic idea of land readjustment is that landown-

ers agree that location of their land would be adjusted and

property resized normally it becomes 2/3 of the previous

size. However due to new infrastructure development and

creation of public spaces, the land price rise and the land

owners in the end make proft. At the same time additional

land taken from landowners can be sold to developers,

thereby fnancing the land readjustment process.

As land readjustment can help to develop wide range of

different situations - it also has some negative effects, like

encouraging sprawl (Sorensen, 2000b, p. 218). Rapidly

growing urban population in Tokyo led that in 1975 all

23 wards were almost fully urbanized (Zhao, 2006, p. 29).

Naturally this led to further urbanization of urban fringe.

Here land readjustment is extremely helpful for developers

to rearrange a usually very fragmented property limits to

a different patterns and free up plots for big developments

(Sorensen, 2000a, p. 55). That is why residential develop-

ments around Tokyo have a strictly planned order - they are

basically developed in a tabula rasa situation. The strict zon-

ing prevents diversity in the plots and functions are clearly

separated. This can be seen by looking at a development

of Kashiwa-no-ha station area. Developers can create any

desirable situation they want, so the new high-rise apartment

blocks are standing next to the express train station, big

shopping center and a park.

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

33

In Tokyo possible problems with the contemporary needs

and an existing situation are solved by applying land read-

justment method. Although it is not always perfect it can be

used as a tool to arrange existing very complicated areas for

the future.

Figure 25. Before land readjustment

Figure 26. After land readjustment

Complexity of properties and big number of individual own-

ers are often the problems to start any change in socialist

mass housing areas. In Tokyo, land readjustment enabled

very complex urban fabric to change and meet contempo-

rary needs in very fexible way. However in a socialist mass

housing areas this complexity is not in the land, which is

owned by the government, but in the ownership of apart-

ments. Thus land readjustment method could be remodeled

as an apartment readjustment method where owners would

be encouraged to swap or sell their apartments by getting

benefts.

34 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

HONG KONG - GREEN CONTRAST

According to Miles Glendinning (2012) Hong Kong is a hot

spot for mass housing. After World War II population in

Hong Kong started booming. Both natural increase and im-

migration due to civil war in China contributed to popula-

tion increase from 600 000 in 1945 to 2.5 million in 1957

( Jenks and Burgess, 2003, p. 246).

Today most of the cities are looking after a compact city

model, but in the past trends were different and sprawl was

often the answer to the growing population in Europe and

USA. Hong Kong also tried to distribute growing popula-

tion by creating new towns. However in 1970s the down-

sides of dispersed population became visible as the hilly

terrain was separating new towns from center and lack of

local economy could not make new towns economically self-

suffcient ( Jenks and Burgess, 2003, p. 248). Urban planners

had to rethink the strategy.

The government focused on providing public housing at

low prices to keep up with economic demands. They could

do it easily because they owned the land (Henderson, 1991,

p. 172). However everything was not that simple, because

Hong Kong by using capitalist model, was focusing on rev-

enue and in 1970s they were making one third of all revenue

from land leases - a biggest portion in the world (Hender-

son, 1991, p. 172). This meant that they had a confict on

one side trying to provide cheap public housing by using the

land and on the other side - trying to make proft by renting

out the same land to the developers. Naturally this led to

minimizing the land area for public housing. To compen-

sate loss, buildings had to go high. Henderson (1991, p. 173)

sums up to what situation this policy led: They are obliged

to live in blocks of 35 to 50 stories, made up of apartments

that are little more than glorifed closets (with a predomi-

nant foor-space allocation of 3.3 square metres per person),

formed into estates and new towns with staggeringly high

population densities.

The design of frst public housing projects did not pay a lot

of attention to a free ground space, greenery or other typi-

cal elements of western housing blocks. Instead, the estates

were developed by focusing only on building volumes. This

can be seen by observing some of the frst developments

like Shek Kip Mei Estate (1953), Model Housing Estate

(1954) and others. Of course having in mind all diffculties

with land area, terrain and revenue policy it is hard to expect

anything different.

Today urban area in Hong Kong takes up less than 25% of

all land, around 40% of it is preserved for recreation and

conservation (Hong Kong Census and Statistics Depart-

ment, 2013b). Although the urban area has increased, so

did the population which now is 7.15 million (Hong Kong

Census and Statistics Department, 2013a). New residential

projects, like Kin Ming Estate (Figure 27. and Figure 28. ),

continues to follow the guidelines set by the frst develop-

ments and focuses primarily on the density, forcing residents

to have their recreational activities in surrounding parks.

Hong Kong by having tight pressures for the land and

specifc terrain has produced a well working situation where

greenery is not mixing with mass housing blocks. It is a

contrast to the socialist mass housing developments where

it was very important to provide vast green spaces around

the buildings. However in both cases greens space makes a

big and important part urban fabric and the main difference

is purely a relation of a green spaces with a buildings. Hong

Kong always being an epicenter of business and exchange

gives an idea that today the speed, relation with a city and

urban life is more important for people than daily wander-

ings through green space.

The presence of green space in daily life is still very impor-

tant, but it can be just visual. As socialist mass housing is

now playing by the market economy rules and the lifestyle of

people changed accordingly, the organization of green space

could adapt by interpreting Hong Kong experience. This

means that the amount of green space could be reduced it

is not important anymore for buildings and green to mix, as

long as the visual relation is maintained.

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

35

Hong Kong because of limited land, complex topography

and high demand created an interesting situation where

green and urban spaces work well by being separated. There

is very clear division between what is green and what is

urban.

Figure 27. Kin Ming Estate, picture by Baycrest - Wikipedia user

Figure 28. Kin Ming Estate

36 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

SEOUL - GATED COMMUNITIES

Population of Seoul started to increase rapidly after the end

of the Korean War in 1953, but the modernization and con-

trol of urban space began later. After the war a lot of people

had to be relocated, so in 1950s government started to clear

the slums to make space in the city. It continued in 1960s

too: Most areas near railroads, streets, sewage disposal

facilities and crowded downtown areas were cleared (Shin,

1995, p. 55). In 1962 First and Second National Economic

Development Plans were introduced and rapid economic

growth started (Oh et al., 2009, p. 10). Same year Mapo

Apartments - frst apartment block was built. Although

there are not many scholar sources analyzing this pioneer of

housing block areas in Seoul, the pictures (Figure 31. ) from

that time reveal that Mapo apartments were already built on

an existing urban fabric, moreover, they were built in a place

of a former prison (Matt, 2006). This case demonstrates that

in Seoul housing development started by a redevelopment of

an existing urban situation which was initiated by a govern-

ment policy.

Other pictures reveal extreme contrast with surrounding

area clean modernistic courtyard and dense, low-rise maze

of old streets outside the complex the area of squatters

which eventually was removed. The contrast is emphasized

even more by a wall, which separates two situations, telling

that the frst residential development is Seoul was a gated

community. Interestingly, this relates to the development

before which was a prison. Just instead of protecting

outside from the inside, the sterile situation inside was pro-

tected from the squatting outside.

Naturally, the redevelopment continued and in 1991, after

29 years, this complex was demolished. Today in this area

we can fnd another residential development which con-

tinues the tradition of gated communities. Similar to its

predecessor, new development separates itself from dense

urban fabric with diverse activities and encloses in a clean,

sterile environment.

Although gated communities are heavily criticized, in Seoul

they work quite well and are appreciated by the society. They

can be seen in the frst mass residential developments and

are continued to be built today. Most of the new residential

areas in Seoul today are gated. The biggest concentration

of gated developments in the city center are in Sinbanpo-ro

area which is next to the famous Gangnam entertainment

district. It is interesting relation where calm and at frst sight

boring gated residential area is next to a lively and open part

of the city. Same as frst Mapo Apartments development

which created an island of open space in a dense squatted

neighborhood.

Probably it is this vivid contrast which makes gated com-

munities in Seoul work. Socialist mass housing areas could

beneft from gated areas not by trying to promote safety

or prestige, but by trying to create a contrast to an existing

context. It can be a tool to bring new spaces to the city.

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

37

In Seoul issues with private and public property are solved

by creating gated communities. Often criticized concept of

gated communities here works quite well and is well ac-

cepted by society.

Figure 29. Secured entrance to the area Figure 31. Mapo apartments in 1963

Figure 30. Fenced streetscape

38 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

SHENZHEN - GREEN BOUNDARIES

Shenzhen is noticeable for its green areas and vast scale

which is a contrast to dense and compact neighboring Hong

Kong. This can be compared to the spaces which are found

in soviet planned areas. And indeed in the beginning of

Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SSEZ) the city planning

was still based on the Soviet Union planning model cen-

trally controlled 5 year plans (Bruton et al., 2005, p. 229). In

1986 this model started to change and ft better immense

growth (Bruton et al., 2005, p. 231). Interestingly, the frst

developed, Luohu area was following more Hong Kong

model of space and had relatively narrow 2-4 lane streets

and walkable distances (Zacharias and Tang, 2010, p. 223).

However with further growth more cars came to the city

and city planners decided to focus further developments on

cars by using green corridors (Zacharias and Tang, 2010, p.

223). In modernistic fashion, roads are now surrounded by

green buffer zones.

The similarity of the new city center Futian with Le Cor-

busiers plan for Paris cannot be unnoticed, as Zacharias and

Tang (2010) notice: The cite radieuse model is unmistak-

able, although its reasons are not entirely what Le Corbusier

had in mind. New city center was planned on an agri-

cultural land (Wang et al., 2009, p. 959) and this situation

enabled any decision possible. New housing districts were

planned in Shenzhen using similar ideas, but illegal hous-

ing was appearing on the edge of the city at the same time.

This was due to very fast growth, when at the same moment

city needed cheap housing for people from rural areas and

new housing for richer urban residents (Wang et al., 2009, p.

959).

Although most of the frst developments were often based

on the same layout, later developments tried to introduce

more variety to the urban fabric. But the base of the road

and city structure was laid on soviet planning principles

mixed with infuence of Le Corbusier and the result is a lack

of spatial diversity. Housing blocks often are clearly divided

and separated from each other by immense amount of

greenery. Often greenery and road axes are making distanc-

es unwalkable.

Promotion of vast green spaces between the buildings and

the roads in Shenzhen brings an opposite than desired effect

and creates spatial problems. Greenery is good, but in this

case we can see that ammount is also important. This idea

of overdose of qualities can be seen in socialist mass hous-

ing areas too. Too many green public spaces create unneces-

sary distances and unusable voids. Shenzhen can serve as an

example to demonstrate that excessive green space can bring

negative effects.

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

39

In Shenzhen too many green spaces

create a very monotonic streetscape

and unwalkable distances.

Figure 32. Green boundaries

Figure 33. Unwalkable distances

40 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

HONG KONG

green contrast

unbuilt area in a test site

Hung Hom

76%

SEOUL

gated communities

unbuilt area in a test site

Sinbanpo

82%

SHENZHEN

green boundaries

unbuilt area in a test site

Lianhuacun

85%

TOKYO

land readjustment

unbuilt area in a test site

Kashiwanoha

80%

10 min

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

41

KAUNAS

unbuilt area in a test site

Dainava

89%

Figure 34. Opposite page - A comparison of mass

housing areas in different Asian cities by built/

unbuilt ratio in an area covered by 10 minutes

walk (400 meters radius).

Figure 35. On the right - same size area in one of

the densest, Dainava socialist mass housing, areas

in Kaunas, Lithuania.

Figure 36. On the left - aerial view of Dainava.

42 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

Figure 37. Photo by Alexander Gronsky from series Pastoral 2008-2012

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

43

SHRINKING EASTERN EUROPE AND

LEARNING FROM SHRINKING JAPAN

Here socialist mass housing phenomena is explored as a

common property of Eastern European countries. The con-

sequences, issues and potentials are covered while concept

of Fibercity is presented as a tool for actions. At the same

the main confict points in socialist mass housing areas are

identifed.

44 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

COMMON DENOMINATORS IN EASTERN EUROPE

I

s it possible to fnd common denominators for all post-

socialist countries? These countries are very different

with their climate, culture, religion and history, but one

implied political ideology for the same period, with same

beginning and end, produced common elements. Ivan

Szeknyi (2008) argues that urban forms in socialist societies

did not differ that much. Usually centers of the cities were

deteriorating and the new developments around the city

were booming by building massive housing developments

(Szelenyi, 2008, p. 304). As the main reasons for this pro-

cess he mentions nationalized urban housing market. Private

housing was permitted only in the villages for a long time

and city development was entirely under control of the state.

However, as Szelenyi (2008, p. 304) describes, the state was

interested in a fast and cheap developments. City centers

were not attractive for fast and cheap developments due to

already existing urban fabric. Renovating and upgrading

old buildings was not effcient and fast enough. All focus of

socialist government was primarily on a new mass housing

areas on the edge on the cities in a tabula rasa condition.

Infrastructural and architectural aspects of urban develop-

ment were typically oriented almost exclusively to the local

industrial combine and its attendant (large scale) housing

estates (Beyer and Brade, 2006). These developments were

often generic with small adaptations to a local climate. By

having similar urban forms governed by similar rules, these

cities after 1990s inherited similar problems.

After 1990s Eastern Europe went to the state which Janos

Kornai described this state as crisis of post-communist

transformation (Szelenyi, 2008, p. 309). In 1995 Szelenyi

predicted that growing economies will lead people in East-

ern Europe from mass housing areas to the city centers and

mostly to the suburban areas (Szelenyi, 2008, p. 315). Which

we can now confrm is true. Most of the post-socialist cities

are experiencing suburban growth which is very connected

with a socialist past (Nuissl and Rink, 2005). It is a paradox

in time of shrinkage that cities are expanding regardless

shrinking population. It is agreed that higher income people

move to suburban and central areas, which means that

mass housing areas are slowly becoming inhabited by lower

income population (Stanilov, 2007, p. 183). Having in mind

shrinking population perspectives which project over 20%

of shrinkage in Eastern Europe (United Nations, 2012), we

Construction Change Capitalization

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

45

Plodviv, Bulgaria; City population: 339 077

Kaunas, Lithuania; City population: 311 148

Krakow, Poland; City population: 758 334

Cluj-Napoca, Romania; City population: 324 576

Nizhny Novgorod, Russia; City population: 1 250 619

Lviv, Ukraine; City population: 729 842

Figure 38. A comparison

between different cities in

Eastern Europe. City cen-

ters, socialist mass housing

areas and suburbs.

Figure 39. Opposite page

- 3 common steps for a

socialist mass housing

areas.

46 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

Picture: 214 . , Plodviv, Bulgaria; City population: 339 077

Picture: 6 Birelio 23-iosios g., Kaunas, Lithuania; City population: 311 148

Picture: Franciszka Knianina, Krakow, Poland; City population: 758 334

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

47

Picture: Kulparkivska St, 135, Lviv, Ukraine; City population: 729 842

Picture: Aleea Ciuca 7, Cluj-Napoca, Romania; City population: 324 576

Picture: 4 . , Nizhny Novgorod, Russia; City population: 1 250 619

Figure 40. A glimpse

inside socialist mass hous-

ing areas today in different

countries. There is almost

no difference between these

areas. They hardly refect

climate or cultural back-

ground of the countries.

48 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

needs is one of the main problems today in socialist mass

housing areas. However it is worth to mention that some

of features of socialist mass housing areas, like pedestrian

access, reduction of cars, high density, are seen as an objec-

tives of contemporary developments today (Scott, 2009, p.

62).

The activities were planned in the center of the block

furthest from the edge the highways. However today we

can notice an opposite situation where main roads are most

attractive locations for commercial functions turning the

most active part of the areas from the center to the edge

(Figure 42. ). This shift creates a lot of spatial confict.

can imagine that this rising misbalance of income can be a

serious issue. However, shrinking population does not mean

more vacant housing in Eastern Europe yet. The living

space per person in this part of Europe is still low compared

to a Western Europe. For example in Russia average size per

person is 19.6 square meters as in Denmark it jumps to 51

or Norway 74 (Beyer and Brade, 2006). But with drastically

dropping population rates number of vacant houses and

apartments will increase.

Similarities can be found not only in history, urban patterns

and social problems, but also in architectural and spatial

realities of today. It is easy to see similarities by comparing

visually socialist mass housing areas in different countries

(Figure 40 on page 47). This comparison reveal little dif-

ference in architecture and space.

However the easiest way to fnd common denominators in

socialist mass housing areas is to look at their guide book.

In 1960s a group of architects and planners from The

University of Moscow led by Alexei Gutnov published a

book called The Ideal Communist City (English version

which is referred here came out later, Gutnov and Baburov,

1971). It was a summary and justifcation of developments

which were already being built. Here authors justifed and

explained in a scientifc way the ideal urban confguration

which can be seen in a diagram of New Urban Settlement

(Figure 41. ). This book predicted that 75% of global popu-

lation by the year 2000 will live in a cities and because of

that, we urgently had to rethink the way our cities are built,

the way we live. Based on the communist model of soci-

ety, predictions of the future and problems of that time in

the cities, it was justifed the need to build repetitive high-

rise blocks with community centers in the middle, next to

highways with easy access to public transport. The lack of

private space is seen as necessary element to socialize in gen-

erous green public space. Connectivity with a city center is

not emphasized as the main goal is to bring people to work

in industrial complex and back.

What can be noted from that book, that everything is trying

to have an order: leisure, work, industry, education. And as

we see from the wrong prediction in the book about global

population growth, not everything what is predicted and

planned becomes true. Inability to adapt to unpredictable

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

49

Figure 41.

THE IDEAL COMMUNIST CITY

New Urban Settlement diagram (Gutnov, 1971)

1. Residential units

2. School and sports area

3. Rapid transport above pedestrian level

4. Highway

5. Community center

Concentration towards center

Activities on the edge

Figure 42.

THE NOT IDEAL POST-COMMU-

NIST CITY

An adaptation of NUS to a contemporary situation

(drawing by author)

1. Residential units

2. School and sports area

3. Main street

4. Shopping center, gas station, kiosks

5. Parking in public space

6. Green perimeter

1

2

3

6

4

4

4

4

4

5

50 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

CONSEQUENCES OF SHRINKING EASTERN EUROPE

almost half of all medium-sized cities in Europe

are experiencing population and economic decline

(Schlappa and Neill, 2013, p. 10). Tendencies of shrinking

population in Eastern Europe can just add more impor-

tance and dynamism to the existing conficts and at the

same time, shrinkage can be seen as a tool to change these

areas to better. The consequences of this process are very

well described by Hidetoshi Ohno in a theory of Fibercity

(Ohno and Ohno Laboratory, 2006). Although there focus

is on Japanese context, almost everything can be applied to

Eastern Europe too, as the projections show similar tenden-

cies. Main mentioned moments of shrinkage are: disap-

pearing rural villages, increasing number of vacant homes,

unmaintained infrastructure, growing attraction of a city

center, political and social focus on elderly (as their numbers

will increase, they will become main voters), less attention to

youth, pensions will shrink as society will get older and as a

consequence the economy will face great challenges (Ohno

and Ohno Laboratory, 2006, p. 3).

All these processes are true for both Japanese and Eastern

European contexts, however one moment considering im-

migration might be different. As Japan sees a possibility of

growing immigration rates as one way to maintain work-

force, in Eastern Europe this can be a diffcult challenge.

Europe has a great history on migration and it is historically

very natural process, however the most attractive countries

for immigrants are in Western Europe where economy

is strongest. So if Eastern Europe does not keep up their

economies with Western Europe soon, it is hard to imagine

big fows of immigration which could balance the shrinking

population. In socialist mass housing areas this possibility

would mean that due to relatively small amount of foreign-

ers, these areas are unlikely to become ghettos for immi-

grants.

Another moment which is important to clarify while talk-

ing about socialist mass housing areas is a possibly growing

attraction of the city centers while population is shrink-

ing. It is hard to tell a precise trend for all Eastern Europe.

People will not abandon quickly just recently built suburban

houses, nor city centers can become a massive attraction

points soon, as the heritage restrictions often limit develop-

ments and make them more expensive. But global tenden-

cies, following compact city model, shows that in a long

term city centers should become the most attractive areas.

Looking at examples from Denmark and Netherlands,

it is easy to imagine a combination of new developments

and heritage areas working together in Easter Europe too.

Even though, in some countries like Poland, socialist mass

housing areas are still very popular, they are now becoming

second or third generation houses. Minimum moderniza-

tion, which is done now, like insulating, upgrading heating

system and repainting, has only temporary effect. Without

a more radical renovation the quality of these apartments

will not be able to compete with recent developments in

the city centers. Over half of population in Eastern Europe

live in mass housing areas (Stanilov, 2007, p. 181), meaning

that perspectives of shift towards the city center will greatly

affect socialist housing areas even if they are still popular in

some countries today.

Shrinking population will introduce more change in social-

ist housing neighborhoods. These areas already have seen

some change by adding functions shopping centers, res-

taurants, offce buildings, but did not experience change by

reduction. In this case it is reduction of people. Although it

might seem that new added functions are directly depended

on population of neighborhoods, it is not quite true. New

commercial functions are probably just partly depended,

because, they are focusing mostly on streets - car users. So if

population will reduce in the neighborhoods, it should not

have a massive effect on the new commercial activities on

the perimter of the areas.

Growing number of elderly will need more green, recre-

ational spaces and elderly facilities. As described in report

by Urbact (Schlappa and Neill, 2013, p. 38), it is important

to keep active lifestyle, delay dependency for elderly and

environment should encourage this. However, existing

generic feeling and still present mono-functional design of

the neighborhoods does not create an attractive aging envi-

ronment. Existing confict for a public space, where public

space is invaded slowly by chaotic car parking and commer-

cial activities, can be more present if residents will not have

more control over it. In shrinking society landscape will

gain more importance (Schlappa and Neill, 2013, p. 31), so

the debates for control over it will naturally rise.

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

51

Even if renovated, neighborhoods are still seen as a socialist

housing areas. In the future, it can be argued, that because

of their difference, specifc character, they have possibil-

ity to become new hip areas and be gentrifed. Moreover,

knowing that industrial areas are now often converted for a

residential purpose, this might seem possible. However in-

dustrial areas often have unique spaces and are becoming in-

creasingly rare in the cities. It is very different with socialist

housing areas, as they are generic and very common in most

of the cities in Eastern Europe. This means that these areas

are unlikely to be seen with a positive attitude in the future.

Proposals talking about the historical value, like Belyaevo

Forever (Snopek, 2011) project proposing to include Bely-

aevo socialist housing area in Moscow to UNESCO, can be

seen more as provocative discussions than real possibilities.

Deteriorative view on socialist housing areas can lead to

psychologically less comfortable environment.

To be able to react and use described negative impacts

of shrinkage as an opportunity to reshape socialist mass

housing areas for better, we need tools. There already have

been different possibilities proposing what has to be done,

but they are often too general and avoid direct answers by

providing huge palette of possible actions (Schlappa and

Neill, 2013; Hollander et al., 2009; Laursen, 2008). At the

same time they agree that urban shrinkage demands new

approaches to urban planning, design and management

(Schlappa and Neill, 2013, p. 43). This means that it is not

enough just to fnd some examples which some shrinking

cities successfully applied. We need a completely new ap-

proach towards a contemporary city, a new mindset.

52 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

LEARNING FROM SHRINKING JAPAN

A

fter decades of growth Japan now faces an opposite

tendency rapidly shrinking and aging population.

Japan has similar population tendencies as Eastern Europe.

Estimated population shrinkage in Japan from 2010 to

2060 is -19.51%, while Eastern Europe it is a little bit bigger

-21.63% (United Nations, 2012). However differently than

in Eastern Europe, country is adapting and preparing for

future challenges. A big focus is on aging society, which is

a consequence of shrinking population, public spaces are

often well designed for visually impaired, and government

is trying to adapt economy for future realities. Urban scale

also has model focused on shrinking population. After

decades of different proposals for expanding Tokyo to the

Tokyo bay, at the times facing shrinkage there is a proposal

to manage shrinkage and use it to improve the living condi-

tions Fibercity.

FIBERCITY

Fibercity is a contemporary city vision developed by Hi-

detoshi Ohno at The University of Tokyo (Ohno and Ohno

Laboratory, 2006; Ohno et al., 2012; Ohno, 2004). Although

it focuses on Japan and especially Tokyo, the methods

can be translated to different context and scale too. It was

already shown in a research on Nagaoka city in Japan (Ohno

and Wada, 2012; Ohno et al., 2012). Although Tokyo and

Nagaoka cannot even be compared in size (Tokyo metropol-

itan area has over 35 million population and Nagaoka just

reaches 280 thousand), Fibercity vision showed that it could

be adapted to both contexts.

Not only ability to adapt to different scales is interesting

in Fibercity. This concept fully understands the modern-

istic planning nature and clearly explains the transition

and difference from traditional modernistic planning to a

shrinking city vision of Fibercity. It is very important aspect,

because nature of socialist housing areas in Eastern Europe

is extremely modernistic, thus a model working with them

should have a relation and understanding of their strong

modernistic nature.

Fibercity confronts traditional 20th century city model

Atomic city model and proposes to look at a city not as

a machine, but as a fabric (Ohno, 2004, p. 38). Fibercity

concept goes beyond restrictions of a geometrical city forms

and accepts the unpredictable shapes and fows as the driv-

ing force. Exchange, democracy of mobility, reliable urban

system with various possibilities are the main values. It can

be said that it encompass in one place theories of Richard

Sennett on borders and boundaries (Sennett, 2011) and

Christopher Alexander ideas laid in City is not a tree (Al-

exander, 1966).

As a way of acting Fibercity proposes editing existing rather

than radical modernistic creation from tabula rasa approach.

As Fibercity sees a city as a fabric rather than machine, it

proposes to edit it by using fbers linear elements. This is

a new concept which goes away from modernistic zoning

of surfaces to a more free, democratic and adaptable linear

structure.

Focus on linear elements does not deny modernistic history,

it proposes how to infuence it without again creating tabula

rasa. Importance of linear elements is coming from the

needs of XXI century exchange and freedom of mobility

(Ohno, 2004, p. 28, 31).

Diverse range of applications and fexibility is another

important feature of Fibercity strategy. As in a fabric, fber

does not have to be always the same and can be used in

many different ways to achieve complexity. In concrete

terms various strategies may be conceived, such as insert-

ing a new border into an existing domain, substituting an

isolating boundary with one that encourages exchange, or

relaxing the opposition between domains by blurring their

boundaries (Ohno, 2004, p. 37). This method does not

demand huge investment, which can be an issue in a city

with shrinking population and economy. It is very important

to have this in mind while working with socialist housing

neighborhoods where economical questions are always very

sensitive matter as there is a tendency for lower income

residents to live.

The main challenge using this model for a socialist mass

housing areas is to recognize exiting linear elements and to

fnd where new should be created.

A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

53

Figure 43. An illustration of the Fibercity from

Tokyo Fibercity 2050, Ohno, 2006.

54 A. Ropolas / Conficts. Socialist mass housing (2014)

CONFLICTS IN SHRINKING EASTERN EUROPE

THE COMPLEXITY

mass housing was above all a movement that was domi-

nated by confict, by emergency. (Glendinning, 2012).

We cannot start talking about soviet mass housing areas

without recognizing the full complexity of the issue. Ac-

cording to Miles Glendinning (2012) mass housing emerged

from conficts of struggle for salvation, threat, market

demands and some other practical issues. In post-socialist

countries this confict is even more visible and the descrip-

tion can be expanded with more elements. Soviet housing

block areas encompass huge amount of different issues at

once, because at the same time they relate to completely

different political, economic, historical situations. They are

one of the few remaining elements in post-socialist soci-

ety which try to glue the break of Soviet Union in 1990s.

As most of the structures built during the times of Soviet

Union are demolished or converted unrecognizably, these

areas often stand unchanged - at the same time they are in

the past and in the present. It covers the conficting rela-

tion of soviet housing areas with two political ideologies,

two economical directions and two architectural and urban

realities. These areas leave a strong modernistic mark on

the cities which cannot be redeveloped or change as easy as

some industrial or infrastructural areas of that time. Ulti-

mately these areas hold a confict between communism and

capitalism. Although this is overall very broad confict and

can be expanded to various felds, it can also be identifed

from architectural point of view.

Michel Foucault has proposed a concept of heterotopia

(Foucault and Miskowiec, 1986) which is focusing on

other spaces. It is a concept to defne the space which

is here and not here, which is real and not real at the same

time. This concept does not state that all conficts neces-

sarily are heterotopias, but is shows that heterotopia often

has a contradictory or even conficting elements. We can

use heterotopia as a way of looking at conficts which soviet

mass housing possess. Heterotopia is an interesting concept

to explore a mass housing areas, because heterotopian space

could not have a place in soviet society where everything

was planned, mass housing was standardized, and living

space scientifcally calculated. There could not be any place

for otherness or unpredictability. This can be seen in a typo-

logical guidebook (Zveadina and Blashkevich, 1978) and the

book The Ideal Communist City (Gutnov and Baburov,

1971) where all possible living conditions were set, meaning

that people are unable to do anything beyond that. Thus by

recognizing heterotopia we can fnd those delicate elements

of soviet mass housing areas which are able to adapt, change

and create new meanings by respecting strict and top-down

implied planning attitude.

There are seven original defnitions of heterotopia which

cover different types of spaces. During last decades the

concept was elaborated by other thinkers too and now it

is diffcult to state precisely all possible meanings. So to

keep the idea of heterotopia original, without any additional

interpretations, we can try to fnd the spatial conficts as

heterotopias based on seven original defnitions proposed by

Foucault heterotopias of crises, deviation, compensation,

time, juxtaposition, purifcation and illusion (Foucault and

Miskowiec, 1986).

Firstly, lets try to fnd what social mass housing areas are

not. These areas cannot be called heterotopias of crises,

because they are not spaces for people in crises, neither for

people out of norm or with special needs they are not

heterotopias of deviation too. Not heterotopias of compen-

sation as these areas do not compensate anything. Gated

communities can be seen as a heterotopias (Low, 2008;

Hook and Vrdoljak, 2002) and by Foucaults defnition they

would be heterotopias of purifcation. However, almost

none of the socialist mass housing areas after 1990s became

gated. In most cases the land between the houses remained

public and accessible to everybody.

However soviet mass housing areas impose a contradiction

of time, because they are spaces from different ideology,

which does not exist now, in a contemporary world, stand-

ing often unchanged. In a way they can be compared to a

museums and this means that they are heterotopias of time.

Also there is a confict between city and countryside. They

were built as ultimate symbols of urbanization, with great

connectivity to the city for a new type of dweller, but at the

same time they offered vast green space and ability to run

away from urban environment. This contradiction makes

soviet mass housing areas as a heterotopias of juxtaposition.

Lastly, if soviet housing areas are not gated, they still possess