Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Pollo Vs David

Загружено:

Irish Asilo PinedaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Pollo Vs David

Загружено:

Irish Asilo PinedaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

G.R. No.

181881

Briccio Ricky A. Pollo, petitioner

vs.

Chairperson Karina Constantino-David, Director IV Raquel De Guzman Buensalida, Director IV Lydia

A. Castillo, Director III Engelbert Anthony D. Unite and the Civil Service Commision, respondents

[This case involves a search of office computer assigned to a government employee who was then charged

administratively and was eventually dismissed from the service. The employees personal files stored in the

computer were used by the government employer as evidence of his misconduct.]

FACTS:

On January 3, 2007, an anonymous letter-complaint was received by the respondent Civil Service

Commission (CSC) Chairperson alleging that the chief of the Mamamayan muna hindi mamaya na

division of Civil Service Commission Regional Office No. IV (CSC-ROIV) has been lawyering for public

officials with pending cases in the CSC. Chairperson David immediately formed a team with background

in information technology and issued a memorandum directing them to back up all the files in the

computers found in the [CSC-ROIV] Mamamayan Muna (PALD) and Legal divisions.

The team proceeded at once to the CSC-ROIV office and backed up all files in the hard disk of

computers at the Public Assistance and Liaison Division (PALD) and the Legal Services Division. This

was witnessed by several employees. At around 10:00 p.m. of the same day, the investigating team

finished their task. The next day, all the computers in the PALD were sealed and secured. The diskettes

containing the back-up files sourced from the hard disk of PALD and LSD computers were then turned

over to Chairperson David. It was found that most of the files in the 17 diskettes containing files copied

from the computer assigned to and being used by the petitioner, numbering about 40 to 42 documents,

were draft pleadings or letters in connection with administrative cases in the CSC and other tribunals.

Chairperson David thus issued a Show-Cause Order requiring the petitioner to submit his explanation or

counter-affidavit within five days from notice.

Petitioner filed his Comment, denying that he is the person referred to in the anonymous letter-

complaint. He asserted that he had protested the unlawful taking of his computer done while he was on

leave, citing the letter dated January 8, 2007 in which he informed Director Castillo of CSC-ROIV that the

files in his computer were his personal files and those of his sister, relatives, friends and some associates

and that he is not authorizing their sealing, copying, duplicating and printing as these would violate his

constitutional right to privacy and protection against self-incrimination and warrantless search and

seizure. He pointed out that though government property, the temporary use and ownership of the

computer issued under a Memorandum of Receipt is ceded to the employee who may exercise all

attributes of ownership, including its use for personal purposes. In view of the illegal search, the

files/documents copied from his computer without his consent [are] thus inadmissible as evidence, being

fruits of a poisonous tree.

The CSC found prima facie case against the petitioner and charged him with Dishonesty, Grave

Misconduct, Conduct Prejudicial to the Best Interest of the Service and Violation of R.A. No.

6713 (Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees). Petitioner then filed an

Omnibus Motion (For Reconsideration, to Dismiss and/or to Defer) assailing the formal charge as

without basis having proceeded from an illegal search, which is beyond the authority of the CSC

Chairman, such power pertaining solely to the court. The CSC denied this omnibus motion.

On March 14, 2007, petitioner filed an Urgent Petition before the Court of Appeals (CA) assailing

both the January 11, 2007 Show-Cause Order and February 26, 2007 Resolution as having been issued

with grave abuse of discretion amounting to excess or total absence of jurisdiction. On July 24, 2007, the

CSC issued a Resolution finding petitioner GUILTY of Dishonesty, Grave Misconduct, Conduct

Prejudicial to the Best Interest of the Service and Violation of Republic Act 6713. He is meted

the penalty of DISMISSAL FROM THE SERVICE with all its accessory penalties. This Resolution was

also brought to the CA by herein petitioner.

By a Decision dated October 11, 2007, the CA dismissed the petitioners petition for certiorari

after finding no grave abuse of discretion committed by respondents CSC officials. His motion for

reconsideration having been denied by the CA, petitioner brought this appeal before the Supreme Court.

II. THE ISSUE

Was the search conducted on petitioners office computer and the copying of his personal files

without his knowledge and consent alleged as a transgression on his constitutional right to privacy

lawful? [Note that in the discussion,management prerogative will be tackled as well.]

III. THE RULING

[The Supreme Court DENIED the petition and AFFIRMED the CA, which in turn upheld the CSC

resolution dismissing the petitioner from service. The High Tribunal held that the search on petitioners office

computer and the copying of his personal files were both LAWFUL and DID NOT VIOLATE his constitutional

right to privacy.]

The Supreme Court held that the search made by the Civil Service Commission (CSC) in office-issued

computer of a public employee did not violate Section 2, Article III of the 1987 Constitution since it

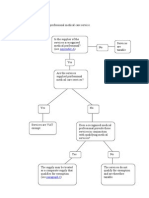

passed the two-fold test:

a. the employee cannot have any reasonable expectation of privacy under the circumstances; and

b. the inception and scope of the intrusion made by the CSC was reasonable.

Citing the American case of O'Connor vs. Ortega, the Court held that public employees' expectations of

privacy in their offices, desks and file cabinets may be reduced by virtue of actual office practices and

procedures, and/or by legitimate regulation. In addition, the Court likewise referred to its ruling in Social

Justice Society vs. Dangerous Drugs Board, et al.which stated that the employees' privacy interest in an office

is to a large extent circumscribed by the company's work policies, the collective bargaining agreement, if

any, entered into by management and the bargaining unit, and the inherent right of the employer to

maintain discipline and efficiency in the workplace. Their privacy expectation in a regulated office

environment is, in fine, reduced; and a degree of impingement upon such privacy has been upheld.

In the case, Pollo, who was under investigation for moonlighting as an advocate for and on behalf of

public employees facing complaints before the CSC, failed to prove that he had an actual (subjective)

expectation of privacy either in his office or in the government-issued computer which contained his

personal files. He did not allege that he had a separate enclosed office which he did not share with

anyone, or that his office was always locked and not open to other employees or visitors. Neither did he

allege that he used a password or adopted any means to prevent other people from accessing his

computer files.

IN DEPTH:

(1) NO, the petitioner had no reasonable expectation of privacy in his office and computer files.

Petitioner failed to prove that he had an actual (subjective) expectation of privacy either in his

office or government-issued computer which contained his personal files. Petitioner did not allege that

he had a separate enclosed office which he did not share with anyone, or that his office was always

locked and not open to other employees or visitors. Neither did he allege that he used passwords or

adopted any means to prevent other employees from accessing his computer files. On the contrary, he

submits that being in the public assistance office of the CSC-ROIV, he normally would have visitors in his

office like friends, associates and even unknown people, whom he even allowed to use his computer

which to him seemed a trivial request. He described his office as full of people, his friends, unknown

people and that in the past 22 years he had been discharging his functions at the PALD, he is

personally assisting incoming clients, receiving documents, drafting cases on appeals, in charge of

accomplishment report, Mamamayan Muna Program, Public Sector Unionism, Correction of name,

accreditation of service, and hardly had any time for himself alone, that in fact he stays in the office as a

paying customer. Under this scenario, it can hardly be deduced that petitioner had such expectation of

privacy that society would recognize as reasonable.

Moreover, even assuming arguendo, in the absence of allegation or proof of the aforementioned

factual circumstances, that petitioner had at least a subjective expectation of privacy in his computer as he

claims, such is negated by the presence of policy regulating the use of office computers [CSC Office

Memorandum No. 10, S. 2002 Computer Use Policy (CUP)], as in Simons. The CSC in this case had

implemented a policy that put its employees on notice that they have no expectation of privacy

in anything they create, store, send or receive on the office computers, and that the CSC may monitor the

use of the computer resources using both automated or human means. This implies that on-the-spot

inspections may be done to ensure that the computer resources were used only for such legitimate

business purposes.

(2) YES, the search authorized by the respondent CSC Chair, which involved the copying of the

contents of the hard drive on petitioners computer, was reasonable in its inception and scope.

The search of petitioners computer files was conducted in connection with investigation

of work-related misconduct prompted by an anonymous letter-complaint addressed to Chairperson

David regarding anomalies in the CSC-ROIV where the head of the Mamamayan Muna Hindi Mamaya

Na division is supposedly lawyering for individuals with pending cases in the CSC. A search by a

government employer of an employees office is justified at inception when there are reasonable

grounds for suspecting that it will turn up evidence that the employee is guilty of work-related

misconduct.

Under the facts obtaining, the search conducted on petitioners computer was justified at its

inception and scope. We quote with approval the CSCs discussion on the reasonableness of its actions,

consistent as it were with the guidelines established by OConnor:

Even conceding for a moment that there is no such administrative policy, there is no doubt in the

mind of the Commission that the search of Pollos computer has successfully passed the test of

reasonableness for warrantless searches in the workplace as enunciated in the above-discussed American

authorities. It bears emphasis that the Commission pursued the search in its capacity as a government

employer and that it was undertaken in connection with an investigation involving a work-related

misconduct, one of the circumstances exempted from the warrant requirement. At the inception of the

search, a complaint was received recounting that a certain division chief in the CSCRO No. IV was

lawyering for parties having pending cases with the said regional office or in the Commission. The

nature of the imputation was serious, as it was grievously disturbing. If, indeed, a CSC employee was

found to be furtively engaged in the practice of lawyering for parties with pending cases before the

Commission would be a highly repugnant scenario, then such a case would have shattering

repercussions. It would undeniably cast clouds of doubt upon the institutional integrity of the

Commission as a quasi-judicial agency, and in the process, render it less effective in fulfilling its mandate

as an impartial and objective dispenser of administrative justice. It is settled that a court or an

administrative tribunal must not only be actually impartial but must be seen to be so, otherwise the

general public would not have any trust and confidence in it.

Considering the damaging nature of the accusation, the Commission had to act fast, if only to

arrest or limit any possible adverse consequence or fall-out. Thus, on the same date that the complaint

was received, a search was forthwith conducted involving the computer resources in the concerned

regional office. That it was the computers that were subjected to the search was justified since these

furnished the easiest means for an employee to encode and store documents. Indeed, the computers

would be a likely starting point in ferreting out incriminating evidence. Concomitantly, the ephemeral

nature of computer files, that is, they could easily be destroyed at a click of a button, necessitated

drastic and immediate action. Pointedly, to impose the need to comply with the probable cause

requirement would invariably defeat the purpose of the wok-related investigation.

Thus, petitioners claim of violation of his constitutional right to privacy must necessarily

fail. His other argument invoking the privacy of communication and correspondence under Section

3(1), Article III of the 1987 Constitution is also untenable considering the recognition accorded to certain

legitimate intrusions into the privacy of employees in the government workplace under the aforecited

authorities. We likewise find no merit in his contention that OConnor and Simons are not relevant

because the present case does not involve a criminal offense like child pornography. As already

mentioned, the search of petitioners computer was justified there being reasonable ground for

suspecting that the files stored therein would yield incriminating evidence relevant to the

investigation being conducted by CSC as government employer of such misconduct subject of the

anonymous complaint. This situation clearly falls under the exception to the warrantless requirement in

administrative searches defined in OConnor.

FYI - Guidelines in the use computers by employees:

The CSC had a policy regulating the use of office computers which stated, among others:

1. The computers are the property of the CSC and may be used only for legitimate purposes.

2. No expectation of privacy. Users except the Members of the CSC, shall not have an expectation of

privacy in anything they create, store, send, or receive on the computers.

3. Waiver of privacy rights. Users expressly waive any right to privacy in anything they create,

store, send, or receive on the computer through the internet or any other computer network.

Users understand that the CSC may use human or automated means to monitor the use of its

computers.

4. Non-exclusivity of computer resources. A computer resource is not a personal property or for the

exclusive use of a User to whom a memorandum of receipt has been issued.

5. Passwords do not imply privacy. Use of passwords to gain access to the computer system or to

encode particular files or messages does not imply that Users have an expectation of privacy in

the material they create or receive on the computer system.

With regard to the second test, the Court held that the search was justified at inception and scope since

there was reasonable ground for suspecting that it will turn up evidence that the employee was guilty of

work-related misconduct.

Вам также может понравиться

- Demand Letter To The Department of JusticeДокумент4 страницыDemand Letter To The Department of JusticeGordon Duff100% (1)

- Municipal and International LawДокумент12 страницMunicipal and International LawAartika SainiОценок пока нет

- New Defense Clandestine Service Blends Civilian and Military OperationsДокумент3 страницыNew Defense Clandestine Service Blends Civilian and Military Operationsjack007xrayОценок пока нет

- Pollo vs. Constantino-DavidДокумент2 страницыPollo vs. Constantino-DavidMichelle Vale CruzОценок пока нет

- Medical Jurisprudence 2013 SyllabusДокумент13 страницMedical Jurisprudence 2013 SyllabusEdlyn Favorito RomeroОценок пока нет

- Gibbs vs. CIR and CTA rules on prescription of tax claimsДокумент2 страницыGibbs vs. CIR and CTA rules on prescription of tax claimsIrish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Case: Pollo Vs David Topic: Search and Seizure of Government Computer DoctrineДокумент3 страницыCase: Pollo Vs David Topic: Search and Seizure of Government Computer DoctrinePiaОценок пока нет

- Philippine Court Motion Declare Defendant DefaultДокумент4 страницыPhilippine Court Motion Declare Defendant DefaultGilianne Kathryn Layco Gantuangco-CabilingОценок пока нет

- 3.1 Ayala Land Inc V CastilloДокумент72 страницы3.1 Ayala Land Inc V CastilloSheena Reyes-BellenОценок пока нет

- Arbitration Clause Valid Despite Challenge to Underlying ContractДокумент2 страницыArbitration Clause Valid Despite Challenge to Underlying ContractKristine Salvador CayetanoОценок пока нет

- Hippocratic OathДокумент1 страницаHippocratic OathkaliyasaОценок пока нет

- 5 Garcia Vs SandiganbayanДокумент11 страниц5 Garcia Vs SandiganbayanBUTTERFLYОценок пока нет

- ELLERY MARCH G. TORRES, Petitioner, vs. Philippine Amusement and Gaming CORPORATION, Represented by ATTY. CARLOS R. BAUTISTA, JR.,Respondent. FactsДокумент2 страницыELLERY MARCH G. TORRES, Petitioner, vs. Philippine Amusement and Gaming CORPORATION, Represented by ATTY. CARLOS R. BAUTISTA, JR.,Respondent. FactsWhere Did Macky GallegoОценок пока нет

- Rules On DNA EvidenceДокумент2 страницыRules On DNA EvidenceNilsy YnzonОценок пока нет

- Mendoza V ComelecДокумент2 страницыMendoza V ComelecKelly MatiraОценок пока нет

- Norkis Trading V GniloДокумент2 страницыNorkis Trading V GniloIrish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Espiritu Vs JovellanosДокумент2 страницыEspiritu Vs Jovellanoshanabi_13Оценок пока нет

- Upus 1Документ4 страницыUpus 1KrzavnОценок пока нет

- Caong Vs RegualosДокумент5 страницCaong Vs RegualosIrish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- ADR Reviewer MidtermДокумент7 страницADR Reviewer MidtermTom SumawayОценок пока нет

- Appeal in Civil Cases and Criminal CasesДокумент27 страницAppeal in Civil Cases and Criminal CasesPrateek MahlaОценок пока нет

- Protacio v. Laya MananghayaДокумент4 страницыProtacio v. Laya MananghayaIrish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Trinidad Et Al Vs Atty Angelito Villarin Lawyer and The ClientДокумент1 страницаTrinidad Et Al Vs Atty Angelito Villarin Lawyer and The ClientCassandra LaysonОценок пока нет

- Pollo vs. Constantino David Digest2Документ3 страницыPollo vs. Constantino David Digest2chrissieОценок пока нет

- CSC Employee Computer Search UpheldДокумент6 страницCSC Employee Computer Search Upheldviva_33Оценок пока нет

- General Milling vs. ViajarДокумент3 страницыGeneral Milling vs. ViajarIrish Asilo Pineda100% (2)

- 038-Liberty Flour Mills Employees v. Liberty Flour Mills, Inc. G.R. Nos. 58768-70 December 29, 1989Документ6 страниц038-Liberty Flour Mills Employees v. Liberty Flour Mills, Inc. G.R. Nos. 58768-70 December 29, 1989Jopan SJОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Provisions On BudgetingДокумент6 страницConstitutional Provisions On BudgetingJohn Dx LapidОценок пока нет

- WCH Open Letter On Who Pandemic Treaty 2Документ2 страницыWCH Open Letter On Who Pandemic Treaty 2Jamie White100% (3)

- 31 Pollo Vs Constantino-David DigestДокумент5 страниц31 Pollo Vs Constantino-David DigestKirby Jaguio LegaspiОценок пока нет

- Piracy in General, and Mutiny On The High Seas or Philippine Waters People V. TulinДокумент2 страницыPiracy in General, and Mutiny On The High Seas or Philippine Waters People V. TulinadeeОценок пока нет

- Tinker V Des Moines Points To PonderДокумент2 страницыTinker V Des Moines Points To Ponderapi-362440038Оценок пока нет

- Estate of Mercedes Jacob Vs CAДокумент18 страницEstate of Mercedes Jacob Vs CAQuennie Jane SaplagioОценок пока нет

- Almeda vs. Bathala Marketing Industries, Inc., 542 SCRA 470 (2008)Документ7 страницAlmeda vs. Bathala Marketing Industries, Inc., 542 SCRA 470 (2008)Jahzel Dela Pena CarpioОценок пока нет

- Agricultural Corp v Security Agency on Wage Order ComplianceДокумент2 страницыAgricultural Corp v Security Agency on Wage Order ComplianceMarivic Asilo Zacarias-LozanoОценок пока нет

- Court determines better right to disputed propertyДокумент2 страницыCourt determines better right to disputed propertyyurets929Оценок пока нет

- Fallacy of Negative PremisesДокумент3 страницыFallacy of Negative PremisesGenaTerreОценок пока нет

- Rojas V MaglanaДокумент4 страницыRojas V MaglanaJennyОценок пока нет

- Aguila Vs CAДокумент6 страницAguila Vs CAPatrick RamosОценок пока нет

- Jardin VS NLRC PDFДокумент1 страницаJardin VS NLRC PDFCel DelabahanОценок пока нет

- SC upholds Bouncing Check Law constitutionalityДокумент2 страницыSC upholds Bouncing Check Law constitutionalityApril Enrile-MorenoОценок пока нет

- "Torture" Means Any Act by Which Severe Pain or Suffering, Whether Physical or Mental, IsДокумент4 страницы"Torture" Means Any Act by Which Severe Pain or Suffering, Whether Physical or Mental, IsKathleen Rose TaninasОценок пока нет

- IlanoДокумент3 страницыIlanoCourtney TirolОценок пока нет

- AMPARO G. PEREZ, ET AL., Plaintiffs and Appellees, PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK, Binalbagan Branch, ET AL., Defendants and Appellants. G.R. No. L-21813 July 30, 1966Документ1 страницаAMPARO G. PEREZ, ET AL., Plaintiffs and Appellees, PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK, Binalbagan Branch, ET AL., Defendants and Appellants. G.R. No. L-21813 July 30, 1966Mitch IsmaelОценок пока нет

- Saguisag v. Exec Secretary OchoaДокумент3 страницыSaguisag v. Exec Secretary OchoaBruce WayneОценок пока нет

- PP vs. DADDAOДокумент9 страницPP vs. DADDAOstefocsalev17Оценок пока нет

- Mantok Realty vs. CLT Realty 2007Документ4 страницыMantok Realty vs. CLT Realty 2007Meg MagtibayОценок пока нет

- Digest UCPB Vs Spouses BelusoДокумент2 страницыDigest UCPB Vs Spouses BelusoylessinОценок пока нет

- Nego Cases 2Документ28 страницNego Cases 2Jake CastañedaОценок пока нет

- Bir Ruling (Da 013 08)Документ5 страницBir Ruling (Da 013 08)Jake PeraltaОценок пока нет

- Tanada Vs AngaraДокумент3 страницыTanada Vs AngaraTOMATOОценок пока нет

- China Banking Corp. v. CoДокумент6 страницChina Banking Corp. v. CoRubyОценок пока нет

- Fabilo Vs IACДокумент2 страницыFabilo Vs IACKristine KristineeeОценок пока нет

- Tibajia V CA Abubakar V Auditor General Inciong V CA Traders Insurance V Dy Eng BiokДокумент5 страницTibajia V CA Abubakar V Auditor General Inciong V CA Traders Insurance V Dy Eng BiokKate Eloise EsberОценок пока нет

- Jamado@tfvc - Edu.oh: Law On SalesДокумент2 страницыJamado@tfvc - Edu.oh: Law On SalesKRIS ANNE SAMUDIOОценок пока нет

- Laher v. LopezДокумент7 страницLaher v. LopezHayden Richard AllauiganОценок пока нет

- Kwin Transcripts - InsuranceДокумент84 страницыKwin Transcripts - InsuranceMario P. Trinidad Jr.Оценок пока нет

- Spouses Luciana and Pedro Dalida vs. CA and Agustin Ramos, G.R. No. L-53983 Sept. 30, 1982Документ1 страницаSpouses Luciana and Pedro Dalida vs. CA and Agustin Ramos, G.R. No. L-53983 Sept. 30, 1982Rea RioОценок пока нет

- Pale Reviewer PDFДокумент51 страницаPale Reviewer PDFNinoОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 127347. November 25, 1999. Alfredo N. Aguila, JR., Petitioner, vs. Honorable Court of Appeals and Felicidad S. Vda. de Abrogar, RespondentsДокумент10 страницG.R. No. 127347. November 25, 1999. Alfredo N. Aguila, JR., Petitioner, vs. Honorable Court of Appeals and Felicidad S. Vda. de Abrogar, RespondentsCarmela SalazarОценок пока нет

- Partnership PrintДокумент7 страницPartnership PrintDeurod JoeОценок пока нет

- Koh vs. Court of Appeals decision clarifies venue rulesДокумент43 страницыKoh vs. Court of Appeals decision clarifies venue rulesLeo GuillermoОценок пока нет

- Philippine Deposit Insurance Corporation ActДокумент22 страницыPhilippine Deposit Insurance Corporation ActBellaDJОценок пока нет

- CBCI NOT NEGOTIABLEДокумент1 страницаCBCI NOT NEGOTIABLEStefanRodriguezОценок пока нет

- Quisay v. People (2016): Lack of Prior Written Authority Renders Information DefectiveДокумент1 страницаQuisay v. People (2016): Lack of Prior Written Authority Renders Information DefectiveAndrea RioОценок пока нет

- Supreme Court rules on sugar annuity disputeДокумент6 страницSupreme Court rules on sugar annuity disputeGeraldine Abila LagutanОценок пока нет

- D2a - 1 Ibaan v. CAДокумент2 страницыD2a - 1 Ibaan v. CAAaron AristonОценок пока нет

- Guiang vs. CoДокумент6 страницGuiang vs. CoJoshua CuentoОценок пока нет

- Roman Catholic Bishop v. De la PeñaДокумент2 страницыRoman Catholic Bishop v. De la PeñaChin MartinzОценок пока нет

- SC rules public officer liable for failing to return money, not for private transactionДокумент5 страницSC rules public officer liable for failing to return money, not for private transactionylessinОценок пока нет

- 6 Royal Shirt V CoДокумент1 страница6 Royal Shirt V CoErwinRommelC.FuentesОценок пока нет

- China Banking Corp Vs BorromeoДокумент9 страницChina Banking Corp Vs BorromeoDeniseEstebanОценок пока нет

- 001 Brondial Civil ProcedureДокумент80 страниц001 Brondial Civil ProcedureisraeljamoraОценок пока нет

- Dumpit-Murillo Vs Court of AppealsДокумент1 страницаDumpit-Murillo Vs Court of AppealsJoseph GabutinaОценок пока нет

- Antazo, Adrian - GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA vs. PURGANANДокумент2 страницыAntazo, Adrian - GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA vs. PURGANANDenz Christian ResentesОценок пока нет

- Gempesaw v. CAДокумент15 страницGempesaw v. CAPMVОценок пока нет

- Supreme Court Rules Punitive Damages are Taxable IncomeДокумент5 страницSupreme Court Rules Punitive Damages are Taxable IncomejОценок пока нет

- R.A. 876Документ6 страницR.A. 876HaruОценок пока нет

- Labor Case 124 147 DigestsДокумент26 страницLabor Case 124 147 Digestsjack reyesОценок пока нет

- R.A. 10590 - Oversees Voting Act of 2013Документ5 страницR.A. 10590 - Oversees Voting Act of 2013Irish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Republic Act No 8344Документ6 страницRepublic Act No 8344Sam de la CruzОценок пока нет

- LyricsДокумент9 страницLyricsIrish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 14 Market DevelopmentДокумент30 страницChapter 14 Market Developmentپایگاه اطلاع رسانی صنعتОценок пока нет

- Labor Stadards Report - Sec. 14, 15, 16Документ7 страницLabor Stadards Report - Sec. 14, 15, 16Irish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Consti 2 - Finals ReviewerДокумент28 страницConsti 2 - Finals ReviewerIrish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Labor Stadards Report - Sec. 14, 15, 16Документ7 страницLabor Stadards Report - Sec. 14, 15, 16Irish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Code of Ethics Medical ProfessionДокумент8 страницCode of Ethics Medical ProfessionAustin CharlesОценок пока нет

- Lright To Refuse TreatmentДокумент7 страницLright To Refuse TreatmentSam de la CruzОценок пока нет

- Santiago A. Del Rosario, Et Al., vs. Honorable Alfredo Bengzon, G.R. No. 88265, December 21, 1989Документ7 страницSantiago A. Del Rosario, Et Al., vs. Honorable Alfredo Bengzon, G.R. No. 88265, December 21, 1989Irish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Garcia-Rueda vs. Pascasio, G.R. No. 118141, September 5, 1997Документ7 страницGarcia-Rueda vs. Pascasio, G.R. No. 118141, September 5, 1997Irish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Bill of Rights ConstitutionДокумент3 страницыBill of Rights ConstitutionSam de la CruzОценок пока нет

- BISIGДокумент2 страницыBISIGIrish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Elmer Vs Rural BankДокумент1 страницаElmer Vs Rural BankIrish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Oblicon Codal ReviewerДокумент9 страницOblicon Codal ReviewerLoris Marriel VillarОценок пока нет

- LyricsДокумент9 страницLyricsIrish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Ipra LawДокумент9 страницIpra LawIrish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- 8 Arco Metal Vs SamahanДокумент7 страниц8 Arco Metal Vs SamahanIrish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- 4 Vergara Vs Coca ColaДокумент7 страниц4 Vergara Vs Coca ColaaiceljoyОценок пока нет

- Medical Services AppendixcДокумент1 страницаMedical Services AppendixcIrish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Labor Law Non-Diminution of Benefits. (T) He Principle Against Diminution of Benefits Is Applicable OnlyДокумент2 страницыLabor Law Non-Diminution of Benefits. (T) He Principle Against Diminution of Benefits Is Applicable OnlyIrish Asilo PinedaОценок пока нет

- Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vo.2, No.2, May 2011Документ289 страницMediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vo.2, No.2, May 2011sokolpacukajОценок пока нет

- Peace Studies: Clark UniversityДокумент22 страницыPeace Studies: Clark UniversityGonzalo Farrera BravoОценок пока нет

- Waiver of Rights To Bail-During Trial For IdentificationДокумент114 страницWaiver of Rights To Bail-During Trial For IdentificationJennica Gyrl G. DelfinОценок пока нет

- Decision On Kenya's Deputy President MR William Ruto's Request For Excusai From Continuous Presence at TrialДокумент27 страницDecision On Kenya's Deputy President MR William Ruto's Request For Excusai From Continuous Presence at TrialJournalists For JusticeОценок пока нет

- SMM of NIKE (Updated)Документ17 страницSMM of NIKE (Updated)Muhammad Usama MunirОценок пока нет

- Atty. Patrick Sarmiento's Administrative Law and Local Government SyllabusДокумент23 страницыAtty. Patrick Sarmiento's Administrative Law and Local Government SyllabusNiel Edar BallezaОценок пока нет

- Anand Yadav Pro 1Документ23 страницыAnand Yadav Pro 1amanОценок пока нет

- Yale-New Haven Case StudyДокумент2 страницыYale-New Haven Case Studyahhshuga50% (2)

- 11 Social Action: Concept and PrinciplesДокумент18 страниц11 Social Action: Concept and PrinciplesAditya VermaОценок пока нет

- Rio 20 Conference SummaryДокумент3 страницыRio 20 Conference SummaryAyush BishtОценок пока нет

- JOSE MIGUEL T. ARROYO v. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICEДокумент2 страницыJOSE MIGUEL T. ARROYO v. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICESally ChinОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Adjudication - Pasquale PasquinoДокумент13 страницConstitutional Adjudication - Pasquale PasquinocrisforoniОценок пока нет

- Overview On The Ethiopian ConstitutionДокумент6 страницOverview On The Ethiopian ConstitutionAmar Elias100% (1)

- The Logic of Developmental StateДокумент19 страницThe Logic of Developmental StateGelo Adina100% (2)

- Indian Judicial System Explained: Supreme Court, High Courts and Lower CourtsДокумент8 страницIndian Judicial System Explained: Supreme Court, High Courts and Lower Courtscsc tikonaparkОценок пока нет

- Classical Criminology HandoutsДокумент3 страницыClassical Criminology HandoutsLove BachoОценок пока нет

- Neighbouring Rights Protection in India: Sanjay PandeyДокумент15 страницNeighbouring Rights Protection in India: Sanjay PandeyVicky VermaОценок пока нет

- Sunga-Chan v. CAДокумент2 страницыSunga-Chan v. CAHans LazaroОценок пока нет

- Guagua National Colleges v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 188492Документ14 страницGuagua National Colleges v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 188492ArjayОценок пока нет