Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Reference Rehmat Ullah

Загружено:

Muhammad FarhanИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Reference Rehmat Ullah

Загружено:

Muhammad FarhanАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Tolerance

By

Sarah Peterson

July 2003

What is Tolerance?

Tolerance is the appreciation of diversity and the ability to live

and let others live. It is the ability to exercise a fair and objective

attitude towards those whose opinions, practices, religion,

nationality and so on differ from one's own.[1] As William Ury

notes, "tolerance is not just agreeing with one another or

remaining indifferent in the face of injustice, but rather showing

respect for the essential humanity in every person."[2]

Intolerance is the failure to appreciate and respect the practices,

opinions and beliefs of another group. For instance, there is a

high degree of intolerance between Israeli Jews and Palestinians

who are at odds over issues of identity, security, self-

determination, statehood, the right of return for refugees, the

status of Jerusalem and many other issues. The result is

continuing inter-group violence.

Why Does Tolerance Matter?

At a post-9/11 conference on multiculturalism in the United

States, participants asked, "How can we be tolerant of those who

are intolerant of us?"[3] For many, tolerating intolerance is

neither acceptable nor possible.

Though tolerance may seem an impossible exercise in certain

situations -- as illustrated by Hobbes in the introductory caption

to this essay -- being tolerant nonetheless remains key to easing

hostile tensions between groups and to helping communities

move past intractable conflict. That is because tolerance is

integral to different groups relating to one another in a respectful

and understanding way. In cases where communities have been

deeply entrenched in violent conflict, being tolerant helps the affected groups endure the pain of

the past and resolve their differences. In Rwanda, the Hutus and the Tutsis have tolerated

a reconciliation process, which has helped them to work through their anger and resentment

towards one another.

Hobbes: "How are you doing

on your New Year's

resolutions?"

Calvin: "I didn't make any.

See, in order to improve

oneself, one must have some

idea of what's 'good.' That

implies certain values. But as

we all know, values are

relative. Every system of belief

is equally valid and we need

to tolerate diversity. Virtue

isn't 'better' than vice. It's just

different."

Hobbes: "I don't know if I can

tolerate that much tolerance."

Calvin: "I refuse to be

victimized by notions of

virtuous behavior."

-- A Bill Watterson cartoon

shows Calvin and Hobbes

walking through the snow.

The Origins of Intolerance

In situations where conditions are economically depressed and

politically charged, groups and individuals may find it hard to

tolerate those that are different from them or have caused them

harm. In such cases, discrimination, dehumanization, repression,

and violence may occur. This can be seen in the context of

Kosovo, where Kosovar Alabanians, grappling with poverty and

unemployment, needed a scapegoat, and supported an aggressive

Serbian attack against neighboring Bosnian Muslim and Croatian

neighbors.

The Consequences of Intolerance

Intolerance will drive groups apart, creating a sense of permanent separation between them. For

example, though the laws of apartheid in South Africa were abolished nine years ago, there still

exists a noticeable level of personal separation between black and white South Africans, as

evidenced in studies on the levels of perceived social distance between the two groups.[4] This

continued racial division perpetuates the problems of inter-group resentment and hostility.

How is Intolerance Perpetuated?

Between Individuals: In the absence of their own experiences, individuals base their

impressions and opinions of one another on assumptions. These assumptions can be influenced

by the positive or negative beliefs of those who are either closest or most influential in their

lives, including parents or other family members, colleagues, educators, and/or role models.

In the Media: Individual attitudes are influenced by the images of other groups in the media and

the press. For instance, many Serbian communities believed that the western media portrayed a

negative image of the Serbian people during the NATO bombing in Kosovo and Serbia.[5] This

de-humanization may have contributed to the West's willingness to bomb Serbia. However, there

are studies that suggest media images may not influence individuals in all cases. For example, a

study conducted on stereotypes discovered people of specific towns in southeastern Australia did

not agree with the negative stereotypes of Muslims presented in the media.[6]

In Education: There exists school curriculum and educational literature that provide biased

and/or negative historical accounts of world cultures. Education or schooling based on myths can

demonize and dehumanize other cultures rather than promote cultural understanding and a

tolerance for diversity and differences.

What Can Be Done to Deal with Intolerance?

To encourage tolerance, parties to a conflict and third parties must remind themselves and others

that tolerating tolerance is preferable to tolerating intolerance. Following are some useful

strategies that may be used as tools to promote tolerance.

Inter-Group Contact: There is evidence that casual inter-group contact does not necessarily

reduce inter-group tensions, and may in fact exacerbate existing animosities. However, through

intimate inter-group contact, groups will base their opinions of one another on personal

experiences, which can reduce prejudices. Intimate inter-group contact should be sustained over

Angela

Khaminwa emphasizes the

flexibility of meanings of the

concept "coexistence."

a week or longer in order for it to be effective.[7]

In Dialogue: To enhance communication between both sides, dialogue mechanisms such

as dialogue groups or problem solving workshops provide opportunities for both sides to express

their needs and interests. In such cases, actors engaged in the workshops or similar forums feel

their concerns have been heard and recognized. Restorative justice programs such as victim-

offender mediation provide this kind of opportunity. For instance, through victim-offender

mediation, victims can ask for an apology from the offender.[8]

What Individuals Can Do

Individuals should continually focus on being tolerant of others in their daily lives. This involves

consciously challenging the stereotypes and assumptions that they typically encounter in making

decisions about others and/or working with others either in a social or a professional

environment.

What the Media Can Do

The media should use positive images to promote understanding and cultural sensitivity. The

more groups and individuals are exposed to positive media messages about other cultures, the

less they are likely to find faults with one another -- particularly those communities who have

little access to the outside world and are susceptible to what the media tells them. See the section

on stereotypes in this volume to learn more about how the media perpetuate negative images of

different groups.

What the Educational System Can Do

Educators are instrumental in promoting tolerance and peaceful coexistence. For instance,

schools that create a tolerant environment help young people respect and understand different

cultures. In Israel, an Arab and Israeli community called Neve Shalom or Wahat Al-Salam

("Oasis of Peace") created a school designed to support inter-cultural understanding by providing

children between the first and sixth grades the opportunity to learn and grow together in a

tolerant environment.[9]

What Other Third Parties Can Do

Conflict transformation NGOs (non-governmental organizations) and other actors in the field

of peacebuilding can offer mechanisms such as trainings to help parties to a conflict

communicate with one another. For instance, several organizations have launched a series of

projects in Macedonia that aim to reduce tensions between the country's Albanian, Romani and

Macedonian populations, including activities that promote democracy, ethnic tolerance, and

respect for human rights.[10]

International organizations need to find ways to enshrine the principles of tolerance in policy.

For instance, the United Nations has already created The Declaration of Moral Principles on

Tolerance, adopted and signed in Paris by UNESCO's 185 member states on Nov. 16, 1995,

which qualifies tolerance as a moral, political, and legal requirement for individuals, groups, and

states.[11]

Governments also should aim to institutionalize policies of tolerance. For example, in South

Africa, the Education Ministry has advocated the integration of a public school tolerance

curriculum into the classroom; the curriculum promotes a holistic approach to learning. The

United States government has recognized one week a year as international education week,

encouraging schools, organizations, institutions, and individuals to engage in projects and

exchanges to heighten global awareness of cultural differences.

The Diaspora community can also play an important role in promoting and sustaining tolerance.

They can provide resources to ease tensions and affect institutional policies in a positive way.

For example, Jewish, Irish, and Islamic communities have contributed to the peacebuilding effort

within their places of origin from their places of residence in the United States. [12]

[1] The American Heritage Dictionary (New York: Dell Publishing, 1994).

[2] William Ury, Getting To Peace (New York: The Penguin Group, 1999), 127.

[3] As identified by Serge Schmemann, a New York Times columnist noted in his piece of Dec.

29, 2002, in The New York Times entitled "The Burden of Tolerance in a World of Division" that

tolerance is a burden rather than a blessing in today's society.

[4] Jannie Malan, "From Exclusive Aversion to Inclusive Coexistence," Short Paper, African

Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), Conference on Coexistence

Community Consultations, Durban, South Africa, January 2003, 6.

[5] As noted by Susan Sachs, a New York Times columnist in her piece of Dec. 16, 2001, in The

New York Times entitled "In One Muslim Land, an Effort to Enforce Lessons of Tolerance."

[6] Amber Hague, "Attitudes of high school students and teachers towards Muslims and Islam in

a southeaster Australian community,"Intercultural Education 2 (2001): 185-196.

[7] Yehuda Amir, "Contact Hypothesis in Ethnic Relations," in Weiner, Eugene, eds. The

Handbook of Interethnic Coexistence (New York: The Continuing Publishing Company, 2000),

162-181.

[8] The Ukrainian Centre for Common Ground has launched a successful restorative justice

project. Information available on-line atwww.sfcg.org.

[9] Neve Shalom homepage [on-line]; available at www.nswas.com; Internet.

[10] Lessons in Tolerance after Conflict. http://www.beyondintractability.org/library/external-

resource?biblio=9997

[11] "A Global Quest for Tolerance" [article on-line] (UNESCO, 1995, accessed 11 February

2003); available athttp://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/fight-

against-discrimination/promoting-tolerance/; Internet.

[12] Louis Kriesberg, "Coexistence and the Reconciliation of Communal Conflicts." In Weiner,

Eugene, eds. The Handbook of Interethnic Coexistence (New York: The Continuing Publishing

Company, 2000), 182-198.

Use the following to cite this article:

Peterson, Sarah. "Tolerance." Beyond Intractability. Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess.

Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: July 2003

<http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/tolerance>.

Additional Resources

Post a comment or suggestion about this page or topic...

Вам также может понравиться

- SynopsisДокумент10 страницSynopsisMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Bank of Punjab: Internship Report ONДокумент7 страницBank of Punjab: Internship Report ONMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Naveed and ButtДокумент5 страницNaveed and ButtMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Main Page000Документ5 страницMain Page000Muhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Chapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesДокумент4 страницыChapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- SahibДокумент45 страницSahibMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- ObjectivesДокумент10 страницObjectivesMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Socio-Economic Causes and Impact of Exchange Marriage (Watta Satta) in Tribal Area of D.GkhanДокумент3 страницыSocio-Economic Causes and Impact of Exchange Marriage (Watta Satta) in Tribal Area of D.GkhanMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Socio-Economic Causes of Watta Satta Marriages in Tribal AreasДокумент3 страницыSocio-Economic Causes of Watta Satta Marriages in Tribal AreasMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Title Page Acknowledgement Table of ContentsДокумент4 страницыTitle Page Acknowledgement Table of ContentsMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- AsДокумент11 страницAsMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Curriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanДокумент2 страницыCurriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Muhammad Abdul RaufДокумент1 страницаMuhammad Abdul RaufMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Rosheen Feroz: Curriculum VitaeДокумент2 страницыRosheen Feroz: Curriculum VitaeMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- To Whom It May Concern: Dated 20 September 2012Документ1 страницаTo Whom It May Concern: Dated 20 September 2012Muhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Desi Efu ReportДокумент66 страницDesi Efu ReportMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Lazib Shah: Degree Year Marks/CGPA Board/ UniversityДокумент1 страницаLazib Shah: Degree Year Marks/CGPA Board/ UniversityMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Chapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesДокумент4 страницыChapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Muhammad Faisal HanifДокумент2 страницыMuhammad Faisal HanifMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Govt. Postgraduate College, D.G.Khan: Hope CertificateДокумент1 страницаGovt. Postgraduate College, D.G.Khan: Hope CertificateMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Importance of RamadanДокумент4 страницыImportance of RamadanMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Curriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanДокумент2 страницыCurriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

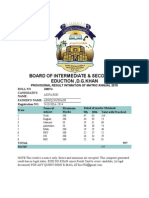

- Matric Result Notice for Asifa Bibi with 557 Total MarksДокумент1 страницаMatric Result Notice for Asifa Bibi with 557 Total MarksMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- People's Review of ADB, Sindh Rural Development Project DraftДокумент46 страницPeople's Review of ADB, Sindh Rural Development Project DraftMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Zahid SynopsisДокумент10 страницZahid SynopsisMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- SaqlainДокумент21 страницаSaqlainMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Sajid Hussain: Degree Years Marks Board/ UniversityДокумент1 страницаSajid Hussain: Degree Years Marks Board/ UniversityMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Reference Rehmat UllahДокумент5 страницReference Rehmat UllahMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Reference Rehmat UllahДокумент5 страницReference Rehmat UllahMuhammad FarhanОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)