Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

CaylanPlazaNP2012 Libre

Загружено:

Anival Lincol Támara LázaroАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CaylanPlazaNP2012 Libre

Загружено:

Anival Lincol Támara LázaroАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

85

awpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology, Volume 32, Number 1, pp. 1000. Copyright 2012 Institute of Andean Studies. All rights reserved.

Piaza iivr axn vuniic vrnvonxaxcr ar rnr Eanis Honizox

crxrrn ov Casix, Nrvrxa Vaiirs, Prn

Matthew Helmer, David Chicoine, and Hugo Ikehara

Te following article examines ancient Andean performance at the Early Horizon site of Cayln (8001 BC), Nepea

Valley, North-Central Coast of Peru. Cayln, a hypothesized early urban polity, was organized around a series of monu-

mental enclosure compounds, each dominated by a plaza. Our research considers public performance from one of Caylns

largest and best preserved plazas, Plaza-A.

Results indicate a spatially exclusive, neighborhood-based plaza environment. Public activities included spec-

tacles with music, processions, and architecture entombment. Patterns of small-scale plaza interactions are also discussed.

At Cayln, regular public interactions structured and maintained group identities in a new residential environment.

Tese results highlight the role of public performance in the maintenance and reproduction of community during periods

of social transformation associated with the emergence of urban lifeways.

La presente contribucin examina la interpretacin ritual en el sitio de Cayln, costa nor-central del Per, durante el

Horizonte Temprano (8001 a.C.). Cayln, una hipottica entidad poltica urbana temprana, fue organizado en torno

a la articulacin de una serie de complejos cercados, cada uno dominado por una plaza, los cuales fueron el foco de una

gran variedad de actividades pblicas. Nuestra investigacin considera el paisaje pblico de la Plaza A, uno de los espacios

ms grandes y mejores conservados en Cayln.

Los resultados indican que mediante la manipulacin y control del movimiento y otras experiencias corporales se

crean contextos de interpretacin ritual extraordinarias dentro de entornos de plazas en barrios espacialmente exclusivos.

Actividades pblicas incluyen espectculos con msica, procesiones, y enterramiento arquitectnico. Patrones de interac-

cin a pequea escala en las plazas son tambin discutidos. En Cayln, interacciones pblicas regulares mantuvieron

identidades grupales en un ambiente residencial novedoso. Estos resultados resaltan el rol de la interpretacin ritual

pblica en el mantenimiento y reproduccin de comunidades durante periodos de transformacin social asociados a la

emergencia de modos de vida urbanos en la costa nor-central del Per.

Matthew Helmer, Sainsbury Research Unit for the Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas, University of East Anglia,

Norwich, NR4 7TJ, United Kingdom, m.helmer@uea.ac.uk

David Chicoine, Department of Geography and Anthropology, Louisiana State University, 227 Howe-Russell-Knien

Geoscience Complex, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, dchico@lsu.edu

Hugo Ikehara, Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh, PA, 15260, hci1@pitt.edu

awpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology Volume 32, Number 1

86

W

ithin the last decade, Andean scholars have be-

gun to recognize the value of considering ar-

chaeological contexts through the lens of performance

studies in order to understand the structures and in-

stitutions of ancient communities (Coben 2006; Hill

2005; Moore 2006; Quilter 2001; Swenson 2011). In-

deed, the archaeological study of performance provides

key insights into methods of social maintenance, trans-

formation, and displays of authority in culturally spe-

cic contexts (Inomata and Coben 2006: 11). In this

article, we focus on plaza settings contemporary with

the emergence of enclosed, incipient urban lifeways on

the North-Central Coast of Peru. Specically, recent

excavations at the Early Horizon center of Cayln (ca.

8001 BC), have yielded signicant spatial and mate-

rial data to assess the design, use, and modication of a

monumental plaza.

Troughout the rst millennium BC, communi-

ties on the North Coast of Peru developed new forms

of community organization characterized by dense

agglomerations of enclosed, walled compounds (e.g.,

Billman 1996; Brennan 1982; Chicoine 2006a; Pozor-

ski and Pozorski 1987; Swenson 2011; Warner 2010;

Wilson 1988). Tis settlement pattern contrasts with

earlier built forms which focused on large, singular, and

open mound-plaza complexes. In the Nepea Valley

(Figure 1), coastal Ancash, Early Horizon settlements

like Cayln supersede Initial Period ceremonial centers

including Cerro Blanco and Huaca Partida (Shibata

2010). Whereas the latter were typically organized on

a central axis and utilized for large-scale public displays

and activities, our research at Cayln indicates that pla-

za settings were designed to facilitate innovative kinds

of performance and social interactions in the context

of incipient demographic and spatial crowding. In this

article, we present spatial and artifactual data from eld

research at Cayln to explore plaza life and public per-

formance during the Early Horizon and link these data

to some of the social changes related to the emergence

of urbanism in coastal Peru.

In overall area, Cayln is the largest site in the

lower Nepea Valley (Daggett 1987: 74). Yet, it has

received little scientic attention (Daggett 1984: 214

218; Kosok 1965: 208209; Proulx 1968: 31, 7172,

1973: 114, 116). In 2009 and 2010, Chicoine and Ike-

hara (2009, 2011) directed the rst systematic map-

ping and excavations at Cayln. Mapping of the stand-

ing architecture combined with horizontal and vertical

excavations yielded important data on the occupation,

organization, and material culture at the site.

Cayln is organized as a series of enclosure com-

pounds, preliminarily interpreted as neighborhoods,

accessed by cross-cutting pathways, corridors, and av-

enues. A striking, recurrent feature of the Cayln com-

pounds is the presence of monumental, benched plazas

surrounded by complex arrangements of smaller patio

rooms, colonnaded galleries, and roofed chambers.

Excavations in various sectors of Cayln have yielded

a large amount of Early Horizon artifacts, including

ceramic panpipes (Pozorski and Pozorski 1987: 58;

Proulx 1985: 244), slate projectile points (Daggett

1987: 74), and decorated ceramics including Stamped

Circle-and-Dot, Textile Impressed, and White-on-Red

designs. Based on preliminary results, Cayln is inter-

preted as an extensive habitation center with strong

public components (Chicoine and Ikehara 2010).

In this article, we focus on Plaza-A, one of the

largest and best preserved structures at the site in an

attempt to understand public life and performance at

Cayln. Field methods included the clearing and map-

ping of surcial architectural remains in addition to

vertical and horizontal excavations to document the

plazas spatial organization and associated activities.

We argue that Plaza-A was an exclusive, neigh-

borhood-oriented public space. We hypothesize that

plaza settings were utilized for gatherings associated

with festivals and other, more personal forms of pub-

lic interactions. Insights into these interactions point

toward the importance of plazas as places to both

structure and maintain independent co-resident group

identities in an incipient urban environment.

Archaeology, Performance and

Ancient Andean Public Life

Other than platform mounds, plazas are the signature

of Andean public life. Teir omnipresence for millen-

nia throughout the ancient monumental landscape is a

testament to the importance of plaza life in Andean so-

87

Helmer, Chicoine, and Ikehara: Plaza life and public performance

ciety. Yet, the articulation of these plazas varies, reect-

ing vastly dierent social structures (see Moore 1996a,

1996b; Swenson 2011). Performance studies provide a

particularly potent framework for investigating ancient

public life. In addition to studies of architectural simi-

larities (e.g., Mackey 1987; Menzel 1959; Rowe 1962;

Williams 1985) and labor investment and organiza-

tion (e.g., Pozorski 1980; Pozorski and Pozorski 2005;

Vega-Centeno 2007), performance studies of public

arenas have the potential to bring unique insights into

mechanisms of social cohesion, interactions, negotia-

tions, and experiences that shaped ancient Andean life.

In the Andes, performance studies have focused

on the materialization of culture with a focus on elite

ideology (DeMarrais 2004; DeMarrais et al. 1996).

Hill (2005), for instance, has emphasized the spec-

tacular qualities of Moche Phase (AD 1800) rituals

of human sacrice, in particular the dismemberment

of war prisoners and sacricial victims. Quilter (2001),

meanwhile, has investigated shifts in Moche public

art and displays of elite authority. More recently, Sw-

enson (2011) has suggested an intimate link between

political actions and exclusive staged spectacles in the

Jequepeque Valley during the late Early Horizon and

Early Intermediate Period. His study points toward the

negotiated and contested aspects of theatrical perfor-

mances, and their importance in the creation of power

asymmetries. Here, we are more concerned with the

role of performance in community transformation and

organization.

We operate from a standpoint of performance

which Kapchan (1995: 479) denes as aesthetic

practices-patterns of behavior, ways of speaking, man-

ners of bodily comportmentwhose repetitions situ-

ate actors in time and space, structuring individual

and group identities. Public events such as festivals,

religious congregations, and other activities relegated

to public spaces fall into what we consider to be pub-

lic performances. Te cultural importance of public

performance comes from shared experiences in built

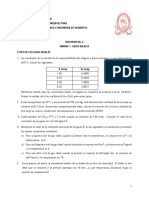

Figure 1. Map of Nepea Valley showing sites relevant to text. Credit: David Chicoine, Hugo Ikehara.

awpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology Volume 32, Number 1

88

settings which are enacted by social groups (Giddens

1984; Tuan 1977). Understanding these shared expe-

riences brings insights into mechanisms of social (re)

production and political structures within institution-

alized spectacles (Inomata and Coben 2006).

Performance archaeology is a relatively recent

eld of study, and its practitioners are still laying out

its foundations (see Inomata and Coben 2006; Pearson

and Shanks 2001). One particularly heated point of

debate concerns the meaning of performance itself,

and its scale of analysis. Hodder (2006: 9697), for

instance, favors a denition of performance as simply

a venue of showing and looking, which includes all

scales of interactions with a lesser emphasis on perfor-

mance as heightened encounters and/or in large-scale

events (see also Goman 1967). Tis is eectively

demonstrated through a case study at Catal Hoyuk,

where Hodder illustrates how highly structured daily

interactions within households represents a type of per-

formance which typied social life. Houston (2006), in

contrast, opposes the idea that small-scale interactions

take on similar qualities as large scale, special events

(see also Hymes 1975). Houston (2006: 137, 149) ar-

gues that the importance of performance comes pre-

cisely from the separation between small-scale, mun-

dane encounters and the extraordinary experience of

large-scale public displays.

We are in general agreement with Houston, Ino-

mata, and others that public interaction operates dif-

ferently from encounters in other contexts, and should

be studied on its own terms. However, performance is

highly contextual, and is something which is constant-

ly embodied through dierent genres (Turner 1987:

82; see also Butler 1993). We consider public perfor-

mance to be a particular genre concerned with com-

munal activities between larger numbers of individuals

housed within a more monumental, or extraordinary

venue than one would encounter in other contexts.

However, we keep in mind that plaza settings, as with

other forms of architecture, are often used in dynamic

contexts not necessarily conned to one type of en-

counter. In other words, it is necessary to acknowledge

the possibility that plazas and their associated activities

were not necessarily conned to episodic large-scale

events, and may have been used uidly for many types

of public encounters which is something we account

for in our analysis of Caylns public settings.

Teoretical foundations of performance archaeol-

ogy are what form the basis of our inquiry into Cayln

public life. We were particularly inspired by Inomatas

(2006: 205) argument that theatrical events within

loosely integrated polities associated with the Classic

Maya were pivotal to integrating groups that could eas-

ily divide at the kin level. We hypothesize that a similar

scenario was likely in occurrence at Cayln. In addition,

our methodological framework is aided from Moores

(2006) and Houston and Taubes (2000) illustrations

that archaeologists can partially reconstruct material-

izations of human sensation which reect relationships

between common experiences and public performance.

Te goal of this paper is to further develop appli-

cations of performance theory, but more importantly to

use performance theory as a unique and useful way to

understand ancient Andean public life. We utilize a con-

textual approach to understanding performance by de-

termining basic plaza experiences and activities that likely

took place. Tis information is used to inform how Early

Horizon public life at the onset of urbanism indicates an

important shift in sociopolitical organization.

Early Horizon Enclosure Compounds

on the North-Central Coast of Per

Between 1,000 and 800 BC (Table 1), changes in set-

tlement patterns resulted in the abandonment of Ini-

tial Period mound-plaza complexes along the North-

Central coast of Peru in favor of enclosure architecture

(Daggett 1987, 1999; Pozorski and Pozorski 1987;

Wilson 1988). Instead of a singular mound-plaza core,

groups nucleated around a number of plazas and small-

er mounds, where singular public spaces no longer

dominated the constructed landscape (e.g., Chicoine

2006b; Pozorski and Pozorski 1987).

In Nepea, the mound-plaza complex of Cerro

Blanco (1,500150 BC), located less than 3km from

Cayln, is one of the best known ceremonial centers

(e.g., Ikehara and Shibata 2008; Shibata 2010; Tello

1943; Vega-Centeno 2000). Recent research by Shi-

bata (2010) has resulted in a Nepea-based sequence

89

Helmer, Chicoine, and Ikehara: Plaza life and public performance

for the Initial Period and Early Horizon. Excavations

indicate that Cerro Blanco was mainly built and occu-

pied during the Initial Period, and later re-occupied by

Early Horizon squatters. Shibatas chronology for Cer-

ro Blanco has four main divisions: (1) Huambocayn

Phase (1,5001100 BC), associated with the rst rais-

ing of the central mound at Cerro Blanco; (2) Cerro

Blanco Phase (1,100800 BC), which is roughly coeval

with the Cupisnique and Manchay traditions associat-

ed with the U-shaped construction; (3) Nepea Phase

(800450 BC), correspondent with the abandonment

of Cerro Blancos U-shaped complex and a brief shift

to megalithic construction in the lower Nepea Valley;

and (4) Samanco Phase (450150 BC) corresponding

with the complete abandonment of Cerro Blanco (Shi-

bata 2010: 305306). Research at Cayln indicates the

establishment of the settlement at the beginning of the

Nepea Phase, and a continuous occupation until the

end of the Samanco Phase and beyond.

Shibatas work at Cerro Blanco provides com-

Table 1. Chronological table showing general and local sequences. Credit: Hugo Ikehara

General sequences Local sequences

Kaulicke 2010 Lanning 1967 Shibata 2010 Daggett 1984 Billman 1994 Burger 1993 Mesa 2007

Nepea Nepea Moche Chavn Chavn

0

Epiformative

Late

Salinar

White on red

100

Samanco

200

Final

Formative

Early

Horizon

Phase 3

Early

Salinar

Janabarriu

300

400

Late

Formative

Late

Guaape

Chakinani

Nepea

Phase 2

500

Urabarriu

Janabarriu

600

700

Phase 1

800

Middle

Formative

Cerro

Blanco

Middle

Guaape

900

Initial

Period

Kotosh

1000

1100

Huambocayn

1200

Early

Formative

Wairajirca

1300

awpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology Volume 32, Number 1

90

parative architectural and contextual data to assess

the Initial Period-Early Horizon transition in Nepe-

a. Te main mound at Cerro Blanco measures 15m

high, with an area of 120 by 95m (Bischof 1997: 206;

Daggett 1987: 118; Proulx 1985: 53; Shibata 2010;

Vega-Centeno 2000: 141). On either side of the main

mound are two smaller platform mounds, forming the

U-shaped wings of Cerro Blanco. Tese encompass

an open area approximately 90 by 90m between the

main mound and surrounding wings, forming a large

open plaza area oriented northeast up-river toward the

Cordillera Negra. Atop one of the surrounding wings,

Julio C. Tello (1943; see also Museo de Arqueologa

y Antropologa de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de

San Marcos 2005; Vega-Centeno 2000: 142146, Fig-

ure 4) excavated a small (5 by 5m) interior gallery room

with low walls and platforms, none measuring over one

meter in height. Tese walls were elaborately decorated

with polychrome feline murals, and the structure faces

the open plaza area. Te discovery of Caylns mark-

edly dierent iconographic themes indicates a con-

scious disassociation with or avoidance of feline-based

visual arts. Cayln artists favored a dierent, abstract

and light manipulated iconographic experience devoid

of colors and animate creatures.

On the opposite wing of Cerro Blanco, Ikehara

and Shibata (2008: 29, Figure 4) found high volumes

of ne serving vessels, likely utilized for feasting along

the U-shaped wing platform area. Ikehara and Shibata

(2008: 151152) interpret Cerro Blancos social or-

ganization as being relatively de-centralized, with the

exception of episodic public spectacles where members

from neighboring communities came together in large

numbers and elites displayed power through commen-

sal politics.

A variety of causes for the abandonment of Initial

Period centers have been put forth by scholars, includ-

ing hostile invasion (Pozorski and Pozorski 1987: 118

119, 121), internal political turmoil (Burger 1992:

189190), and environmental forces (Daggett 1987:

7071). Recently, political factionalism (Pozorski and

Pozorski 2006), innovations in foodways and feasting

practices (Chicoine 2011a), shifts in elite strategies

(Chicoine 2010a), and regional conict (Ikehara and

Chicoine 2011) have been highlighted as major forces

in the reorganization of coastal societies at the begin-

ning of the Early Horizon.

One of the most visible materializations of Early

Horizon social transformation is the emergence of nu-

cleated settlements characterized by stone-wall enclo-

sure compounds, or cercaduras. Tese sites are typically

associated with agglomerated square and rectangular

structures of various sizes built of quarried rocks set in

mortar. Although traditionally associated with post-

Moche urban phenomena (Bawden 1977, 1982; Shi-

mada 1994), cercaduras and other forms of enclosed

urban lifeways represent the most salient form of com-

munity organization in Early Horizon Nepea and

elsewhere (Brennan 1982; Chicoine 2010a; Chicoine

and Ikehara 2010; Swenson 2011; Warner 2010).

Early Horizon enclosures are documented

around the North-Central coast in Nepea (Chicoine

2006b; Chicoine and Ikehara 2010; Daggett 1984,

1987; Proulx 1968), Santa (Wilson 1988), Casma

(Ghezzi 2006; Pozorski and Pozorski 1987, 2005), and

into the Vir, Moche, and Jequetepeque valleys further

north (Billman 1996; Brennan 1978, 1982; Collier

1955; Warner 2010). Many of these enclosures have

only been documented through survey, but excavated

examples include Chankillo (Ghezzi 2006), Pampa

Rosario, and San Diego (Pozorski and Pozorski 1987)

in Casma, Cerro Arena in Moche (Brennan 1978), and

Jatanca in Jequetepeque (Warner 2010). In Nepea

(Figure 1), enclosure compounds have been reported

at Huambacho (Chicoine 2006b), Sute Bajo (Cotrina

et al. 2003), Samanco (Daggett 1999), and Cayln

(Chicoine and Ikehara 2010). On the North-Central

coast, these enclosures have high densities of ceramic

panpipes (Chicoine 2006b: 6; Pozorski and Pozorski

1987: 58; Proulx 1985: 244) and large quantities of

maize possibly associated with brewing maize chicha

(Chicoine 2011a: 436; Pozorski and Pozorski 1987:

5859, 119).

At Huambacho, Chicoine (2006a, Figures 4.4

4.5) identied at least four room types, including large

colonnaded patios, backrooms of various sizes around

patios, completely enclosed small storage rooms, and

plazas. Huambacho is dominated by two monumental

plazas, each enclosed by four benched walls decorated

with geometric friezes, and rows of decorated columns

91

Helmer, Chicoine, and Ikehara: Plaza life and public performance

creating roof structures along the top platform levels

(Chicoine 2006a: Figure 4.3). Plazas are accessed by

narrow staircases no more than a meter wide and lo-

cated in the corners. Te Huambacho settings are em-

bedded in a highly controlled access environment, and

are connected to each other through narrow, baed

corridors. Stylistically, Huambacho art contrasts mark-

edly from previous polychrome feline supernaturals,

and instead favor light-manipulated geometric designs

which were painted white and sunken at various depths

to form positive and negative replicated designs (Chi-

coine 2006b: 1112). Research at Cayln brings more

insights into crucial social developments in Nepea

during the rst millennium BC.

Field Research at Cayln

Te Proyecto de Investigacin Arqueolgica Cayln

began in 2009 with the objective of mapping the ar-

chaeological complex and documenting the prehistoric

occupation of the most extensive settlement in Nepe-

a. Te rst phase of the project (20092010), was

carried out under the direction of Chicoine and Ike-

hara (2009, 2011). Fieldwork resulted in the system-

atic architectural mapping of the ca. 50ha monumental

core (Figure 2), as well as the topographical mapping

of more than 200ha in the surrounding Cerro Cayln

slopes and gullies. Based on its immense size, Cayln

likely represents a primary center of a lower-valley

polity with secondary satellites at the smaller sites of

Huambacho, Sute Bajo and Samanco.

Cayln is located 15km from the Pacic Ocean

and 60km from the base of the Cordillera Negra

mountain system (Daggett 1984: 215). Cayln was

rst documented by Kosok (1965), who was baed by

the sites size, as well as its labyrinthean and orthogonal

layout. Later survey research by Proulx (1968, 1973,

1985), and Daggett (1984, 1987, 1999) provided

a basic sketch of the site and descriptions of surface

materials. Daggett (1987: 74, 1999) was the rst to

recognize a main occupation during the Early Horizon

on the basis of architectural similarities with the sites of

San Diego and Pampa Rosario in Casma (Pozorski and

Figure 2. Map of Cayln with Compound-A and Plaza-A shaded; dot denotes location where Figure 3 photograph was taken. Credit:

David Chicoine, Hugo Ikehara, Luis Tandaipan.

awpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology Volume 32, Number 1

92

Pozorski 1987: 5170), and the discovery of ceramic

panpipes and Stamped Circle-and-Dot ceramics.

Stylistic evidence places Caylns primary occu-

pation during the Early Horizon, most likely between

the ninth and rst centuries BC based on compara-

tive radiocarbon evidence from Huambacho (Chicoine

2010b; Chicoine and Ikehara 2010, 2011). Cayln was

subsequently reoccupied by several dierent groups

until the colonial period. Te reoccupations are mainly

documented by hundreds of looted graves at the sur-

face of the site. Te core of the site is composed of at

least a dozen enclosure compounds organized around

well-dened axes and avenues. Current research is on-

going to determine the contemporaneity of the dier-

ent architectural compounds. Based on preliminary

spatial and material evidence, it is hypothesized that

these compounds were built and maintained by co-

resident groups (Chicoine and Ikehara 2010: 365).

Each compound comprises a series of colon-

naded patio rooms, smaller roofed areas, galleries,

and corridors. Early Horizon architecture at Cayln is

exceptional for the quality of its stonework, complex-

ity in layout, and consistency in building technique,

materials, and basic rectangular modular aspect. Walls

are typically built of quarried rocks set in clay mortar

and their exterior facades are usually well faced and,

in some instances, decorated with elaborate niches,

columns, and friezes. As observed at other Early Ho-

rizon centers in the region, walls at Cayln are consis-

tently erected using the orthostatic technique (Brennan

1980: 6; Chicoine 2006a: 87, 2006b: 16).

In addition, each compound is dominated by a

large plaza open to the sky, but enclosed with monumen-

tal platform benches and high walls. Tis article presents

data from Plaza-A (Figures 3, 4, 5), a space embedded

within one of the larger and better preserved compound

areas at the site. Material and spatial data were recov-

ered through mapping, surface clearing of architecture,

area excavations, and three-dimensional reconstructions.

Combined, these various methods of research yield sig-

nicant data about Caylns public landscape.

Excavations at P|aza-A

Fieldwork at Plaza-A involved the clearing and map-

ping of standing architecture. Tis operation was car-

ried out as part of the systematic mapping of the com-

Figure 3. Photograph of Plaza-A from the southwest. Credit: David Chicoine.

93

Helmer, Chicoine, and Ikehara: Plaza life and public performance

plete archaeological complex at Cayln. Twenty-one

rectangular rooms were identied in the immediate

vicinity of Plaza-A, within an area that appears bound

to a single enclosure compound. Tey vary in surface

area between 36 to 400sq m. Te rooms appear to ex-

hibit some variability in their organization, perhaps in

relation to their respective function. Tese compound

rooms are reminiscent to those at Huambacho (Chi-

coine 2006b), which are interpreted as patio rooms,

storerooms, and living quarters. Other excavations

on-site have documented dense refuse assemblages

within a sub-compound area, including hearths, trash

accumulations, and dried feces likely associated with

intense domestic use. Te structures contiguous to

Figure 4. Plan reconstruction of the

Plaza-A and the excavation units realized in

2009 and 2010; the shaded area denotes area

of raised platform benches. Credit: Hugo

Ikehara.

Figure 5. Isometric reconstruction

of Compound-A and Plaza-A. Credit:

Matthew Helmer.

awpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology Volume 32, Number 1

94

Plaza-A, in addition to sharing adjoining walls, share

the same general alignment 46 degrees east of mag-

netic north. Tis shared compass orientation further

strengthens the relationship between the plaza and its

adjacent rooms as part of a single compound.

Most structures at Cayln are still standing today

but Plaza-A is particularly well preserved which facili-

tated more accurate clearing and mapping. Stone and

mud walls of Plaza-A and its surrounding compound

rooms are estimated to be at least two meters high.

Seven corridors averaging between one and two meters

in width surround Plaza-A. Some of these corridors

served as paths of entry, while others appear to be used

as ll chambers and refuse deposits that do not connect

to plaza accesses. Te compound in which Plaza-A is

embedded is only accessible through a 1.75m wide cor-

ridor with numerous bends and baed check points.

We systematically cleared the area around Plaza-

A, and found two one meter wide entrances in the east-

ern and western corners. Tese entrances formed the

focus of excavations, henceforth Entrance 1 and En-

trance 2, as part of UE2 and UE5, respectively, which

totaled 180sq m (Figure 4). Field procedures consisted

in the clearing of wall and oor features and the sam-

pling of matrix contents through in situ recovery and

screening (3mm mesh) in natural and cultural layers.

Plaza-A is enclosed by monumental bench walls or ter-

races on all sides. Te central area measures approxi-

mately 45 by 45m. Te monumental wall consists of

smaller retaining walls encasing a ll-chamber topped

by a oor. Tis wall is estimated to have stood at ap-

proximately ve meters, and slightly higher (6.3m)

along the southwestern extent where a higher number

of terrace levels are present.

As for most areas at Cayln, the stratigraphical

sequence at Plaza-A includes a surface layer of wind-

blown sand over a stratum of rubble composed of the

collapsed roof superstructures and wall structures. Te

rubble layer is laid on top of a thin accumulation of

sand, and sometimes trash and ash associated with the

use of clay plastered oor contexts. Te oors them-

selves are laid over a stratum of ll composed of sand,

Figure 6. Photographs of Entrance 1 (UE2) access and architecture (inset: drawing of one of the lock apparatuses). Credit: David

Chicoine, Hugo Ikehara.

95

Helmer, Chicoine, and Ikehara: Plaza life and public performance

trash, and rubble arranged as suboor middens and

construction lls before reaching the sterile sand and

gravel soil. Successive building episodes are visible

through superimposed oors, blocked staircases, and

raised architecture.

Entrance 1 (UE2) Excavations. Excavations at En-

trance 1 totaled 75sq m. Tis excavation revealed a

corner entrance, three levels of platform benches, re-

mains of a sculpted column, a window, and a staircase

leading from the entrance down the various platform

bench levels down to the open plaza oor (Figure 6).

All architecture was covered in a yellowish brown plas-

ter and constructed with locally quarried rocks. Tese

data, presented below, provide a wealth of information

regarding public life at Cayln.

Te plaza entrance is relatively narrow, measuring

approximately one meter wide. It is located approxi-

mately four meters above ground level on the top plaza

platform (Figure 7) and originates from a narrow cor-

ridor connected to colonnaded patios and backrooms

to the southwest. A type of lock was documented on

the highest bench level, where two square niches with

reeds were found (Figure 6). Similar lock or door de-

vices have been documented at the site of Chankillo in

Casma (Ghezzi 2006: 72). Te staircase leading from

the top platform bench and inner corridor down to the

plaza oor measured one meter wide, with 13 steps.

Tree levels of platform benches were document-

ed; the top two were excavated. Tese top two benches

measured 1.3m high and 2.3m wide, and were deco-

rated with a positive-negative stepped geometric de-

sign sunken at various depths (Figure 7). Designs were

sculpted out of plaster atop at quarried rocks. Rem-

nants of white paint were recovered on the plaster of

the friezes. Entrance 1s excavated column was partially

destroyed. It measures 0.7 by 0.5m with what we be-

lieve to be a sculpted S design at the base (Figure 8).

Mapping revealed a number of similar sized colonnades

visible at the surface likely decorated with analogous

designs. Te Cayln columns and designs are similar to

examples excavated at Huambacho (Chicoine 2006b:

Figure 7. Photograph of Entrance 1 (UE2) decorated platform benches and staircase (scale: 100 cm). Credit: David Chicoine.

awpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology Volume 32, Number 1

96

11, Figure 7). Finally, a one meter wide window was

documented along the northwest plaza wall on the sec-

ond platform level with a sculpted frame. It is uncer-

tain whether or not more windows once have lined the

entirety of the plaza walls, due to wall collapse in this

portion of the plaza.

With regard to stratigraphy, the unit was excavat-

ed to the abandonment level (Floors 1 and 2) with the

exception of a small vertical excavation on the highest

bench level directly in front of Entrance 1. A sequence

of ve oors was documented on this platform (Fig-

ure 9), which extended down to sterile sub-soil. Ini-

tial strata comprise windblown sand intermixed with

dense layers of wall collapse above the last plastered

oor. Floors are covered with a yellowish gray plaster

and were found relatively clean of refuse. In between

subsequent oor levels are layers of gray sand and grav-

el with dense secondary refuse deposits.

Figure 8. Photograph of the

remains of sculpted column

excavated in Entrance 1 (UE2)

(scale: 100 cm). Credit: David

Chicoine.

97

Helmer, Chicoine, and Ikehara: Plaza life and public performance

Entrance 2 (UE5) Excavations. Te entrance

opposite Entrance 1 was also excavated in the

eastern plaza corner. UE5 extended both inside

and outside of the plaza in order to gain infor-

mation from outer corridor areas (Figure 10).

Covering 105sq m, Entrance 2 excavations docu-

mented a corner entrance, two levels of decorated

platform benches, three decorated columns, a

sealed staircase (Figure 11), and seven outer cor-

ridors terracing up from modern surface level to

the top of the plaza.

Here, only two levels of platform benches

were documented in contrast to three at En-

trance 1. Te top platform bench level comprises

a 2.5m area between the colonnades and outer

retaining wall forming what was likely a roofed

patio area, based on the discovery of cane thatch,

Figure 9. Photograph of the stratigraphic sequence documented during the vertical excavations of UE2 (top bench). Credit: David

Chicoine.

Figure 10. Plan reconstruction of Entrance 2 and the excavations of

UE5. Credit: David Chicoine, Hugo Ikehara, Matthew Helmer.

awpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology Volume 32, Number 1

98

and cane-imprinted plaster. Tis platform extends an

additional two meters outside of the colonnaded area

with a decorated faade identical to the geometric pat-

tern documented from Entrance 1. Tis platform is

fronted by a smaller, undecorated platform which leads

down to the open plaza surface. Te columns appear to

be ornamented with the same S shaped design seen

at the base of the column associated with Entrance 1.

Another one meter wide staircase was discovered in

this plaza corner, analogous to Entrance 1. However, this

staircase was blocked with stone seals which were used as

ll chambers to create two plastered oors on top of the

staircase during a later phase of use. Additionally, the one

meter wide outer corner entrance was blocked with a sim-

ilar seal, with a dense amount of refuse utilized to build

up the highest platform bench during the nal construc-

tion phase. As a result, Entrance 2 excavations provided

clear indications of two major construction phases in that

portion of the plaza: an early phase when the entrance

and staircase were being used, and a later phase when

these were sealed and built over with a higher platform.

Outside of Entrance 2, a large corridor area was

documented between the plaza and the adjacent spac-

es. Excavations provide an L-shaped transect of the cor-

ridor system leading to Plaza-A. Corridor walls were

nely plastered along the exterior facades, but were

crudely plastered with ngerprint marks on the inside.

Along the northern side of Entrance 2, three cor-

ridors were excavated, none of which provided direct

access into the plaza. Te top two corridors extended

1.5m down to well preserved oors. Tese corridors

were relatively clean of artifacts and packed with large

stones which likely served as ll materials to reinforce

the high plaza walls.

Along the southern side of Entrance 2, four ad-

ditional narrow corridors were excavated. Each of these

contained much denser artifact assemblages than the

northern corridors, likely reecting more intense us-

age. Tese corridors had a series of 90 degree zig-zag-

ging turns, and terraced up to the uppermost corridor

which aorded direct plaza access. Te uppermost

corridor also had the densest artifact assemblage. Te

Figure 11. Photograph Entrance 2 (UE5) sealed staircase with subsequent bench built on top. Credit: David Chicoine.

99

Helmer, Chicoine, and Ikehara: Plaza life and public performance

discovery of plaster with cane imprints within

the layers of wall collapse indicates the corridors

were roofed.

Entrance 2s stratigraphy (Figure 12) was

documented through two small vertical excava-

tions inside and outside of Plaza-A, in addition

to the oors and construction ll materials ex-

cavated above the staircase. Inside the plaza, ve

superimposed oors align well with the oor

sequence retrieved in UE2. A vertical excava-

tion extended three meters from the top of the

outer plaza retaining wall down to the base of

the wall in the sterile sub-soil. Tis vertical exca-

vation was located directly outside of the plaza

entrance, and documented remnants of an early

staircase, a sequence of destroyed oors, and

dense layers of secondary refuse construction ll.

Combined, excavation data from both en-

trances help to understand the construction and

subsequent renovation of Plaza-A. During early

phases, plaza oors were between 1 and 1.5m

lower, which were raised through a series of ren-

ovations involving dense layers of refuse topped

with a plastered oor. Each renovation, we be-

lieve, was associated with the accretion of walls

in order to retain the higher surfaces (Figure 13).

Previous columns were used to align the higher

walls, which was evidenced in the UE5 excava-

tions. Remains of earlier plaster friezes were also

discovered in UE2 platform bench construction

ll. During a late phase of use, Entrance 2 was

sealed and its inner staircase was entombed in a

well preserved state.

Materia| Remains from P|aza-A

With the exception of surface materials from mixed temporal

contexts, diagnostic materials recovered from Plaza-A can be

associated with the Early Horizon occupation based on stylis-

tic and stratigraphic grounds. Early Horizon materials include

7, 272 ceramic vessel sherds, 200 non-vessel ceramic objects,

Figure 12. Prole drawing of UE5 (inner plaza) and UE5-Ext. 3 (outer plaza), Plaza-A Entrance 2. Credit: David Chicoine, Matthew

Helmer.

Figure 13. Isometric reconstruction of the superimposed construction

phases documented at Plaza-A, Entrance 1 southwest corner. Credit:

Hugo Ikehara.

awpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology Volume 32, Number 1

100

1.64kg of animal bones, 72kg of lithics, 24.5kg of shell

remains, and 5.6kg of botanical remains. Vessel shapes

and styles (Tables 2 and 3) are all characteristic of the

Early Horizon in the region (see Chicoine 2010b;

Daggett 1984, 1987; Kaulicke 2010; Pozorski and

Pozorski 1987, 2006; Proulx 1968, 1985). Non-vessel

ceramic objects include panpipe fragments, reshaped

pottery sherd discs, a spindle-whorl, and grater bowl

sherds. Animal bones include large mammals (cam-

elidae and canidae), small mammals (rodentia), avian

bones, and sh bones. Lithic artifacts include akes,

cores, projectile points, a mace head, and grinding

stones. A vast array of plant remains was collected; by

number, maize (Zea mays) and peanuts (Arachis hypo-

gea) represent the bulk of the corpus. Finally, miscella-

neous artifacts include what appear to be macaw (Aras

macao) feathers, a wooden spindle rod (huso) with at-

tached bers; four pre-forms and 16 beads made from

Spondylus (Spondylus princeps) shell; and dried feces.

Tese data are discussed further in the following sec-

tion analyzing Plaza-A performance and spectacle.

Evaluating Performance at Plaza-A

Te analysis of plaza encounters at Cayln focuses on

how the architectural arrangement of Plaza-A manipu-

lated the senses, creating common emotional experi-

ences (see Moore 2006). Tis is central to the notion

that public performance entails heightened interac-

tions in special contexts, as illustrated earlier (Eliade

1957; Houston 2006; Hymes 1975). Here, we focus

on experiences associated with movement and visual

elds. We correlate perceptual data with dierent activ-

ities associated with the plaza, focusing on continuities

and changes through time.

Te analysis is based on the architectural and

material evidence retrieved during eld excavations as

well as from three-dimensional reconstructions of the

plaza. A general problem came from sourcing materials

to specic contexts, since Plaza-A oors were generally

kept clean. Te bulk of the sample came from second-

ary deposits involved with construction lls. How-

ever, the need for construction ll before renovation

episodes would have been most pragmatically solved

by utilizing trash produced nearby (see Smith 1971).

Indeed, the discovery of earlier clay friezes in construc-

tion ll strengthens the evidence that plaza-associated

refuse is associated with secondary deposits. While

these contexts are certainly mixed, a large sum of this

refuse likely came from plaza usage.

Table 3. Ceramic vessel forms with frequencies and depositional

contexts from Plaza-A assemblage. Credit: Matthew Helmer.

Vessel shape Total

%

of total

%

of ne/

decorated

%

ne/

decorated

ne

serving

Bottle 14 4.60 n=9;

64.3%

28.10%

Stirrup Spout

Bottle

14 4.60 n=9;

64.3%

28.10%

Carinated Bowl 16 5.30 n=8;

50.0%

25%

plain

serving

Bowl 15 4.90

Shallow Bowl 6 2.00

Deep Bowl 11 3.60

Incurved Bowl 30 9.80 n=1;

3.3%

3.10%

Neck Jar 51 16.70 n=1;

2.0%

3.10%

Neckless Jar 148 49.00 n=4;

2.7%

12.50%

Total 305 100.00 n=32;

10.7%

100.00%

Tab|e 2. Ceramic decoration types from Plaza-A and their

percentages of the total Plaza-A decorated assemblage. Credit:

Matthew Helmer.

Decoration n %

Later

White-on-Red 16 21.1

Pattern Burnished 2 2.6

Circle-Dot 7 9.2

Incised Appliqu 6 7.9

Earlier

Textile Impressed 19 25

Zoned Punctate 7 9.2

Fine Blackware 10 13.1

Misc. 9 11.8

Total 76 100

101

Helmer, Chicoine, and Ikehara: Plaza life and public performance

Spatial data are compared between dierent

spaces within the compound area, elsewhere on-site, as

well as neighboring sites in the region. We also consult

iconographic data from the Moche (AD 1800) of the

North Coast, famous for their ne line ceramic draw-

ings which vividly depict ritual activities (see Donnan

and McClelland 1999). Moche Phase groups occupied

Nepea only a few centuries after Caylns abandon-

ment, and built an outpost only a few kilometers from

Cayln at the site of Paamarca (see Chicoine 2011b;

Schaedel 1967; Trever et al. 2011). Based on current ra-

diocarbon measurements from the Santa Valley to the

north, it is unlikely that Moche Phase constructions

at Paamarca began before AD 300 and/or continued

after AD 800 (see Chicoine 2011b: 543544). Moche

visual arts provide a link to explicit iconographic evi-

dence available for interpreting performance in Early

Horizon Nepea. We also consult comparative data

from the Nasca (AD 200600), where relevant work

has been done regarding music and public ceremony

(Carmichael 1998; Gruszczynska-Zilkowska 2009).

Finally, we consult ethnographic evidence per-

taining to public festival from traditional Andean

groups (Romero 2002; Stobart 2002) to put in per-

spective the Cayln results. Burger and Salazar-Burger

(1998) have made a similar analysis between traditional

Andean groups and Initial Period spectacle at the Cen-

tral Coast site Mina Perdida. Tey argue that although

signicant changes have occurred, a common culture

history between these groups and ancient Andean cul-

tures creates one of the few cross-cultural references

available for evaluating ancient performance (Burger

and Salazar-Burger 1998: 29).

Visua| Fie|ds

Visual experiences are crucial in the creation of a spe-

cial place, and also share key insights into the inclu-

sionary or exclusionary characteristics of spaces. Te

most apparent special visual quality at Plaza-A is the

level of monumentality and detail employed in the

construction. Walls were higher, larger, and also more

nely constructed; the retaining wall of the plaza

stood between ve and six meters, and towered over

walls of other structures that averaged two meters in

height based on wall collapse estimates and standing

wall measurements. Outer walls visible to outsiders

had smooth white plaster and were adorned with white

decorated adobes and friezes, which would have shined

in the sunlight. Typical architecture in domestic con-

texts at Cayln is unpainted, un-plastered, or crudely

plastered with nger print marks. Plazas are one of the

most highly decorated areas of Cayln, with complex,

step-designed geometric friezes.

Other extraordinary visual experiences inside

Plaza-A are indicated by iso-views and focal points

inside of the plaza. Te high benches enclosing the

Figure 14. Viewshed inside

Plaza-A. Credit: Matthew Helmer,

Hugo Ikehara.

awpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology Volume 32, Number 1

102

open plaza space blocked any potential viewing from

outside. At Cayln, architects created visual exclusiv-

ity, which contrasts markedly with Initial Period plazas

designed to openly broadcast public events (see Burger

and Salazar-Burger 1991, 1998; Moore 1996b). Dark,

narrow, enclosed corridors contrasted with the open,

white painted plaza reecting bright light in the sunny

desert landscape. Te entire 180 degrees of visual plane

is enclosed by the plazas high walls, creating a plaza-

centered visual experience (Figure 14). Plaza-focused

visual experiences contrast with Initial Period plazas,

where visual experiences focused on other features,

such as a fronted pyramid or an extension of view into

the horizon (Moore 1996b: 111, 113).

Plaza-A facilitated a space for face-to-face inter-

actions for larger numbers of individuals than all other

areas around the compound. Trough the result of

successive building phases, Plaza-A has a total surface

Figure 15. (Top) Iso-view inside of Entrance

1. (Bottom) Iso-view outside of Entrance 1

from Patio 1A. Credit: Matthew Helmer,

Hugo Ikehara.

103

Helmer, Chicoine, and Ikehara: Plaza life and public performance

area of approximately 2023sq m. Most of the space is

represented by benched areas (ca. 1340 sq m, 66%),

while the unroofed, open area is smaller (ca. 683sq m,

34%). Based on capacity estimates published by Moore

(1996b: 149), the plaza could have held around 100

individuals during smaller-scale plaza interactions, and

perhaps as many as 500 individuals for larger events.

Te architecture of Plaza-A emphasizes the im-

portance of the southern wall as a focal point. Te

southern wall is signicantly higher than other plaza

walls, with an estimated height of 6.3m. Terefore,

individuals entering Entrance 1 via the southern wall

would have been more prominent and had a better

vantage point to the area below. A window located near

to this entrance provided a viewing area for individuals

inside the plaza to the outside, but was placed too high

to allow outsiders to view in (Figure 15). Te benches

all face the sunken plaza oor as a visual focal point, in-

dicating a stage-audience orientation for possible plaza

interactive experiences.

All benches and oor areas are visible to anyone

inside the plaza. Wide visual elds with dierent tiers

of occupied space facilitated face-to-face interaction

between individuals on the same bench level, and be-

tween individuals sitting on the benches and standing

at the oor level (see Vega-Centeno 2010: 134 for a

similar argument of bench-oor interaction). Moche

iconography shows interactions between individuals

sitting on benches and others standing on a lower level,

possibly associated with elite-commoner relations and

oering ceremonies (Donnan and McClelland 1999:

59, 100). Frieze iconography would have been visible

from anywhere in the plaza, although maximum view-

ing would have come from the open plaza oor.

Other architectural details inside the plaza also

contributed to the extraordinary nature of the visual

experience through abstract, shadow-manipulated de-

signs. Te stepped friezes form a continuous geometric

pattern across the platform bench facades. Te friezes

created mesmerizing visual eects through the sharp

contrast between white/light and black/shadow areas

active through varying depths. Plaza columns depict

similar geometric designs, but are hollow, allowing light

to pass completely through. Combined with changing

perspectives as one moves throughout the plaza, these

friezes become changing and dynamic expressions that

dazzle the eye.

Display items recovered at Plaza-A, such as weap-

ons, stone pendants, decorated vessels and blue striped

clothing would have added to this special visual experi-

ence. Red feathers were recovered from oor contexts.

In the upper corridor leading to Entrance 2, numer-

ous red, blue, and green parrot feathers were recovered

(Figure 16). Te feathers likely belong to the scarlet

macaw (Ara macao). Spondylus shell (Spondylus prin-

ceps) beads and pre-forms were also recovered from

de facto contexts (Figure 17). Tese are indigenous to

Ecuador far to the north and are considered to be an-

cient Andean prestige items (see Carter 2008; Paulsen

1974; Pillsbury 1996). Ikehara (2007) argues that the

display of exotics at Cerro Blanco in Nepea played a

primary role in spectacles as one of the few indicators

Figure 16. Photograph of Macaw feathers recovered from

Plaza-A. Credit: Matthew Helmer.

Figure 17. Photograph of Spondylus shell beads and pre-forms

recovered from Plaza-A. Credit: Matthew Helmer.

awpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology Volume 32, Number 1

104

of social status in Initial Period Andean chiefdoms, and

we argue that exotic display was important to public

spectacle at Cayln as well.

Accessing P|aza-A

Physical access into Plaza-A is one of the most dening

characteristics of what made the plaza extraordinary

for its patrons through exclusivity and manipulation

of motion. As aforementioned, Initial Period plazas

on the North-Central Coast emphasized large, open

spaces, with graded access relegated to mound tops.

In contrast, the Cayln evidence indicates that plazas

were embedded within enclosure compounds, high

walls, a series of baed corridors, doorways, and lock

systems. Te locks were likely functional considering

the strength of two pairs of ca. 15cm wide reeds, each

located in a square stone and mud niche. Indeed, the

reeds were found still solidly in place within the wall

matrix, more than 2000 years after their abandonment.

During early phases, access to Plaza-A was possible

through both entrances from zig-zagging, narrow cor-

ridors only large enough for one person to pass at a time.

Corridors did not have other connecting hallways, and

emphasized elongated two way movement. Corridors ar-

ticially increased travelling distance from real distance

between nearby rooms and the plaza. Tis speaks to the

exclusive nature of plaza access and the desire to increase

the dierence between the outside and the inside.

Compound rooms surrounding Entrance 1 have

the most direct and shortest paths of access into Plaza-

A (Figure 18, Table 4). Tis is the only area where a

nearby avenue connects the enclosure complex with

the entire eastern quadrant of Cayln. It is possible that

the administration of Plaza-A originated in this more

monumental area to the west, based on its proximity

to the entrance and minimal distance to traverse before

achieving plaza access (see Hillier and Hanson 1984).

Here, compound walls are higher, and the plaza has an

extra platform bench and lock system associated with

the more monumental Entrance 1.

Figure 18. Plan reconstruction of

access paths to Entrances 1 and 2.

Credit: Hugo Ikehara, Matthew

Helmer.

105

Helmer, Chicoine, and Ikehara: Plaza life and public performance

Access into Plaza-A from Entrance 2 is much

more restricted, with an extended series of zig-zagging

corridors beginning from compound rooms and grad-

ually terracing up to the entrance. During later plaza

use, access into Plaza-A became further restricted when

Entrance 2 was sealed and built over with higher plat-

forms. At this time, eastern inhabitants would have

had to navigate extra distances because of the sealing

of Entrance 2. Also, the inward renovation of the plaza

added outside corridors with each building phase.

Overall, systems of entrances, locks, and corri-

dors at Plaza-A indicate the intention of Caylns archi-

tects to restrict access and movement between the plaza

and outer-lying areas. From a spatial syntax perspec-

tive, topological complexities embedded in the built

environment are keys in structuring behaviors such as

pedestrian trac and other human movements (Hillier

and Hanson 1984; Turner and Penn 2002). Such con-

siderations were explicitly materialized in plaza settings

at Cayln.

Once inside the plaza, access patterns were still

explicitly laid out. Staircases located in corners allowed

access through the various bench levels and down to the

open oor. Based on their worn condition, the staircases

were heavily used. Terefore, although it seems that ac-

cess was exclusive, those who had intimate knowledge

of the plaza utilized the space quite regularly. Tis con-

trasts with staircases excavated at some Initial Period sites

where staircases show little evidence of use (e.g., Cardal,

see Burger and Salazar-Burger 1991). During later plaza

use, the western Entrance 2 staircase was entombed with

oors built on top, perhaps as a further form of spatial

control. Entrance 2s corner access was also blocked, and

the cutting o of movement from this side of the plaza

likely had signicant social implications involved with

the connement of use to the monumental Entrance 1.

Te seals used to create the surfaces above the entrance

were not plastered over, leaving the outline of previous

staircase walls clearly visible.

At Huambacho, Chicoine (2006a: 106109)

notes similar access patterns, with small corner en-

trances originating from patio rooms and narrow cor-

ridors. Navigation throughout the compound area is

much easier at Huambacho, since there are only two

compound areas in contrast to more than a dozen es-

timated at Cayln (see Chicoine and Ikehara 2010).

More enclosure compound areas housing individuals

from diering social groups residing together likely

created the more stringent access patterns seen at Cay-

ln between neighborhood areas.

Procession and the Spectac|e

of Movement and Music

Patterns of access indicate single le, maze-like mo-

tion as a key component to experiencing Plaza-A.

Ancient Andean spectacles were not stationary events,

and movement was critical (e.g., Bastien 1985; Isbell

1985; Mendoza 2000; Rasnake 1988; Sallnow 1987).

Human depictions in ancient Andean iconography

are often shown in side prole emphasizing motion,

and frequently portray music, dance, and procession

in conjunction with one another (e.g., Bolaos 1988:

Figures 45; Donnan 1982; Donnan and McClelland

1999: Figures 4.29, 4.31, 4.83, 4.84; Lumbreras 1972:

Figure 18).

Te spatial layout of Plaza-A lends itself to an

extensive procession component. Te key here is the

inter-connected nature between residential areas and

the plaza. Processions could have started in connected

domestic patios, and then passed through the maze-

like corridors before funneling into the plaza through

the designated entryways. Longer processions, possibly

Table 4. Access distances to entrances 1 and 2. Credit: Matthew

Helmer.

Entrance 1

Room area

(m2)

Distance to

plaza (m real)

Distance to

plaza

(m travelled)

Number

of turns

Patio 1-A 462 5 20 2

Patio 1-B 196 9 28 5

Backroom 1-A 51 1 28 4

Backroom 2-A 48 1 42 4

Avenue n/a 10 >125 10

Entrance 2

Patio 2-A 360 8 119 11

Patio 2-B 484 6 139 10

Patio 2-C 304 6 55 4

Backroom 2-A 147 1 47 3

awpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology Volume 32, Number 1

106

involving outside visitors, could have been conducted

from the long avenue, passing through Compound-As

western patio groups before entering Plaza-A. Moche

iconographic processions show one individual leading

a musical procession of some 31 dancers interlocked in

held hands followed by musicians (Donnan and Mc-

Clelland 1999: Figure 4.31). Tis indicates a single-

le nature of procession movement, and the narrow

pathways throughout Plaza-A compare favorably with

elongated, single-le procession. Attention to move-

ment is also indicated by the tiered rows of benches

and staircases laying out a connected path throughout

the plaza. Te worn nature of Plaza-As stairs and oors

attest to their heavy trac, which likely necessitated

the series of renovations.

Further evidence for procession and dance is indi-

cated by the discovery of panpipes throughout Plaza-A.

Te omnipresence of panpipes throughout Early Ho-

rizon contexts around the North-Central Coast indi-

cates their importance in the social landscape (Chicoine

2006a; Daggett 1987; Pozorski and Pozorski 1987;

Proulx 1985; Wilson 1988). Sixty-eight panpipe frag-

ments were found in Plaza-A (Figure 19).Tese appear

to be built to size prototypes, with minimal variation

noted in the sample. Tube openings range in size from

610mm in diameter generally, with one incidence

of larger tubes measuring 15mm in diameter. Proulx

(1985: 244) argues that Nepea panpipes were built

with a slip-cast technique to create size prototypes. At

Cayln, panpipe fragments were recovered from oor

contexts as well as from wall fall and construction ll

contexts where we argue that plaza-associated refuse was

located.

Music may not have been a casual activity for

popular consumption in Andean prehistory, and has

been documented as a privileged activity reserved for

special occasions (Romero 2002: 2021). In highland

Bolivia, Stobart (2002: 88) notes that even today little

music making takes place outside of festivals. Ethno-

historically, dierent genres of Andean music were ac-

companied by specic instruments for each activity

(Bolaos 1988: 226227). Traditional Andean soci-

eties continue to reserve dierent types of music for

dierent activities, such as rites of passage, festivals,

religious music, and work music (Romero 2002: 31,

Figure 2).

Because of Andean musics unique place within

formal events, it is likely that Caylns panpipes rep-

resent a particular ideology of public performance.

Chicoine notes a variety of musical instruments at

Huambacho, including drumsticks, utes and pan-

pipes (Chicoine 2006a: 134, 177, Figure 6.5) which

he associates with feasting events (Chicoine 2011a).

Panpipe oerings were excavated inside of a plaza at

Chankillo which borders the sites solar observatory

(Ghezzi and Ruggles 2007: 1241), indicating that Ear-

ly Horizon panpipe usage may have also been associ-

ated with cosmological events.

Comparative evidence for specic panpipe usage

in Andean antiquity can also be taken from Early In-

termediate Period contexts. At Cahuachi on the South

Coast (AD 200600), Nascas largest ceremonial site

Figure 19. Photograph of ceramic panpipe remains recovered

from Plaza-A. Credit: Matthew Helmer.

107

Helmer, Chicoine, and Ikehara: Plaza life and public performance

interpreted as a pilgrimage center (Silverman 1993),

ceramic iconography shows the usage of these panpipes

in public ceremonies (Carmichael 1998: Figure 13),

possibly associated with agricultural fertility perfor-

mances (Townsend 1985: 125). Experiments have in-

dicated that Nasca panpipes conform to size prototypes

with a typical range of two octaves (Gruszczyska-

Zikowska 2008: 154). Tese panpipes may have been

engineered to produce the highest possible ranges of

sound creating both melody and complex dissonance

(Gruszczyska-Zikowska 2008: 164).

Modern panpipes are also built at specic size

prototypes, where each size corresponds to an octave

range (Romero 2002: 30). In traditional Aymara com-

munities, panpipe performances are frequently paired

as duets played in an interlocked exchange of com-

plementary notes in dierent ranges (Stobart 2002:

8081). Donnan (1982: 99, Figure 4) also notes that

Moche panpipe players are usually paired in iconogra-

phy, with their panpipes tied together. Larger panpipe

performances during modern day feasts form a me-

lodic dissonance as groups of individual players engage

in competitive playing of dierent melodies (Stobart

2002: 89). Caylns sonic environment likely embod-

ied a particular musical ideology reected in the con-

formity of panpipe size and plaza locus of use. Com-

parative evidence indicates a possible association with

duets and wide musical ranges to create a mesmerizing

experience in complement with abstract plaza art.

Te design of Plaza-A, we argue, was primarily

focused on public spectacle. However, as alluded to ear-

lier, it is important to recognize the potential uidity of

usage within public spaces. Based on the plazas central

location within a residential compound and the diver-

sity of the associated material remains, it is likely that

Plaza-A was used outside of the large-scale spectacles

for which it was primarily designed. Material evidence

for other types of plaza activities comes from oor re-

coveries including lithic akes, cores, textile produc-

tion materials (wooden huso rod and spindle whorl),

and high ratios of cooking and utilitarian vessels in re-

lation to serving vessels (Table 3). Further evidence for

regular plaza use comes from surfaces showing heavy

use-wear. Although access patterns were complex and

rigidly controlled, those living in the immediate vicin-

ity of Plaza-A would have had intimate knowledge of

the area and could have regularly frequented the plaza.

In these smaller scale contexts, the plaza likely func-

tioned as an exclusive courtyard for compound resi-

dents. Frequent face-to-face interactions forged a col-

lective identity through exclusion from other enclosure

compounds.

Summary

To summarize, the monumentality of Plaza-A was

an immediate indicator of the spaces dierence from

other areas. Patterns of physical and visual perception

show that particular attention was devoted to create an

enhanced, exclusive experience inside Plaza-A. Public

interactions would have contrasted with interactions in

surrounding residential spaces. Movement was restrict-

ed but continuous and accompanied by music, and

sight was confounded by view shed, light, and shadow

manipulation.

Festivals centered on music and procession as ac-

tivities of ritualized movement and sound which created

common emotional experiences. Display items may

have been adorned as individual markers of status. Fes-

tivals also emphasized a trance-like experience through

dance, zig-zagging, single-le movement, and abstract

art. Activities involved a stage and audience style of pre-

sentation. Bodily co-presence between various members

of the enclosure complex was paramount to public inter-

actions and the maintenance of community.

Compound residents likely also used the plaza

to impress outsiders brought in from the north avenue

through the surrounding neighborhood. We venture in

suggesting that each compounds respective plaza was

a marker of sub-group identity at Cayln. Spectacles

would have showcased the plaza at its ideal, as a theater

run by compound residents. At other times, the plaza

functioned as a neighborhood courtyard, when more in-

timate interactions could have taken place. Cayln was

a crowded, populous place where the ability to achieve

privacy played a major role in the maintenance of com-

munity. Outside activity was blocked through high walls

and sunken environments, with fragmented and moni-

tored access ways enacting an exclusive experience.

awpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology Volume 32, Number 1

108

Private rituals could have also taken place in the

plaza without outsiders being able to see them. Regular

public encounters inside Plaza-A could have formed

an attachment to place, necessary for the identication

of ones community and ideology. Tese interactions

gained symbolic power through the extraordinary plaza

space. Te controlled nature of the plaza experience re-

ects a desire for community exclusivity in early urban

environments in both a real and symbolic sense. All of

this was done in an eort to distinguish the plaza, and

interactions within it, from the mundane, as well as

from other compound groups through the promotion

and display of communal activities.

Discussion: Early Horizon Plaza

Settings in Perspective

Te evidence excavated at Cayln and presented in this

article allows for a discussion of performance in the

context of incipient urbanism on the North-Central

Coast during the Early Horizon. Historically, research

on early Andean coastal architecture has focused on the

large mound-plaza complexes associated with painted

feline visual arts which predate the enclosure com-

pound tradition seen at Cayln (e.g., Burger and Sala-

zar-Burger 1991, 1998; Conklin 1982; Fung 1988;

Grieder 1975; Moore 1996b; Pozorski 1980; Pozorski

and Pozorski 1987; Tello 1943; Williams 1985). Tese

structures are typically associated with plazas which are

much larger than what is seen during the subsequent

enclosure compound tradition.

Moore (1996b, 2005) has analyzed experiential

qualities at one of the largest of these mound-plaza

complexes, Sechn Alto (2,1501000 BC, from Po-

zorski and Pozorski 2005) in the neighboring Casma

Valley. At Sechn Alto, the main mound measures 300

by 250m and 35m high. It is fronted by four large

rectangular plazas extending approximately 1200m

into the distance surrounded by low mounds and walls

(Pozorski and Pozorski 2005: 145). Te low retaining

walls of Sechns more than one kilometer long plaza

create an experience of extended depth, making the

principal mound seem distant and the plaza courtyard

space extend further into the horizon (Moore 1996b:

111). Moore suggests that orientation played a key role

in the visual experience from the main mound, where

the extended depth created an innite view across the

plaza courtyard and horizon into the Cordillera Negra.

He (1996b: 160161) hypothesizes a plaza focused ex-

perience at Sechn sites, and interprets Sechns central

alignment as an axis of movement, possibly for proces-

sions. Moore argues that U-shaped centers focused on

easily projectable forms of expression, such as shouted

phrases, body postures, and music which were broad-

casted through the open design (Moore 1996b: 163).

Conversely, Sechn Alto and other Initial Period

centers illustrate graded access relegated to mound tops

(e.g., Burger and Salazar-Burger 1991, 1998; Fuchs et

al. 2011: Figures 35; Pozorski 1983; Pozorski and

Pozorski 2005). Like many Initial Period platform

mounds, the main mound of Sechn Alto was accessed

by a single monumental staircase. Tis staircase was

located in front of the plaza area which connected to

various terraces or atria and enclosed rooms. Of in-

terest, one of the small summit structures at Sechn

Alto shares elements with later plazas such as Plaza-A

at Cayln, with platform benches and rows of deco-

rated colonnades (Pozorski and Pozorski 2005: Figures

8, 150). It is possible that these elements shifted from

mound-top to plaza during the subsequent enclosure

compound tradition in the region. In any case, the

dierence is striking and lends weight to contrasting

forms of social organization. A similar shift is noted by

Swenson (2011) and Warner (2010) in Jequetepeque

at the end of the Early Horizon.

In Nepea, Early Horizon architecture as seen

through eldwork at Cayln contrasts sharply with

previous Initial Period settings, and changes hint at

new forms of social, political, and religious arrange-

ments. For instance, when we contrast Cayln with

previous patterns at neighboring ceremonial centers,

strikingly dierent pictures emerge allowing for dia-

chronic insights into the development of new forms

of community during the Early Horizon. During the

Cerro Blanco Phase, groups directed most of their

building eorts toward large central platform mounds

seen at Cerro Blanco and Huaca Partida. At the be-

ginning of the Nepea Phase, around 800 BC, Initial

Period ceremonial centers were abandoned and popu-

109

Helmer, Chicoine, and Ikehara: Plaza life and public performance

lations nucleated at extensive enclosure-based settle-

ments. Troughout the Samanco Phase and until the

rst century BC, the Cayln data points toward less

social integration and a greater spatial fragmentation

as evidenced by the construction and renovation of a

multitude of low mounds and benched plazas.

Preliminary results point towards forms of socio-

political arrangements in which neighboring co-resi-

dent groups competed and collaborated for communal

prestige in an incipient urban environment without

a clearly dened, singular hierarchy. Central to the

maintenance of this organization was the ability of dif-

ferent groups to host public events which emphasized

exclusionary strategies (Chicoine 2010a, 2011a). At

Huambacho, these public events were held at a small

elite center, while at Cayln they were held in large

residential compounds in close proximity to neighbor-

ing groups. Tis type of political economy diers from

Initial Period public events which emphasized more

integrated public events (Ikehara and Shibata 2008).

It is likely that Cerro Blanco spectacles incorporated

populations from various hamlets throughout Nepea.

In contrast, the Huambacho and Cayln evidence il-

lustrate a more fragmented ritual landscape.

Te need for diering social groups to coalesce

together permanently may have been predicated by an

increase in conict seen throughout the North-Central

Coast during the Early Horizon (Ikehara 2010; Wilson

1988). Exclusive public interactions within diering

residential compounds at Cayln were likely a cop-

ing mechanism which kept individual groups solidi-

ed within this time period of social upheaval.

Further north during the second half of the Early

Horizon, analogous sociopolitical developments are

also materialized in the emergence of enclosures and

urbanism (Brennan 1982; Swenson 2011). In the Je-

quetepeque valley, the site of Jatanca (Swenson 2011;

Warner 2010) was organized as eight enclosure com-

pounds. Te compounds were horizontally elongated,

with a chain of access beginning with a high walled but

easily accessed plaza with central entrance, and end-

ing in increasingly exclusive stage-like and residential

zones.

Te Jatanca situation contrasts with Cayln.

Plazas at Jatanca are embedded within and accessed

through the other compound rooms. Tey also lack

the platform benches found at Cayln, but contain

platform stages behind the plaza which served as fo-

cal points for ritual performances. Public spectacle at

Jatanca involved rituals associated with choreographed

rites of presentation (Swenson 2011: 298) centered on

these stages, and emphasized separation between plaza

audience and exclusive platform set (Swenson 2011:

299). Combined, the data from Nepea and Jequete-