Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

K Steer, Roman Scotland

Загружено:

Ionutz Ionutz0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

18 просмотров15 страницThe Scottish Historical Review, Vol. 33, no. 116, Part 2 (oct., 1954), pp. 115-128. Jstor is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content. In 1937 the Glasgow Archaeological Society appointed a Committee to organize a systematic investigation, by means of surveys and excavations, of Roman roads and forts in south-west Scotland

Исходное описание:

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документThe Scottish Historical Review, Vol. 33, no. 116, Part 2 (oct., 1954), pp. 115-128. Jstor is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content. In 1937 the Glasgow Archaeological Society appointed a Committee to organize a systematic investigation, by means of surveys and excavations, of Roman roads and forts in south-west Scotland

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

18 просмотров15 страницK Steer, Roman Scotland

Загружено:

Ionutz IonutzThe Scottish Historical Review, Vol. 33, no. 116, Part 2 (oct., 1954), pp. 115-128. Jstor is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content. In 1937 the Glasgow Archaeological Society appointed a Committee to organize a systematic investigation, by means of surveys and excavations, of Roman roads and forts in south-west Scotland

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 15

Roman Scotland

Author(s): Kenneth Steer

Source: The Scottish Historical Review, Vol. 33, No. 116, Part 2 (Oct., 1954), pp. 115-128

Published by: Edinburgh University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25526263 .

Accessed: 11/08/2013 07:23

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

Edinburgh University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Scottish

Historical Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Roman Scotland

IN

1937

the

Glasgow Archaeological Society,

on

the initiative

of Mr.

J.

M.

Davidson,

appointed

a

Committee to

organize

a

systematic investigation, by

means

of

surveys

and

excavations,

of Roman roads and forts in south-west Scotland. This bold

and

imaginative project

was

in the best traditions of the

Glasgow

Society,

which,

like its sister

society

in

Dumfries,

has

so

often

taken the lead in the

exploration

of Roman remains within its

territory;

and there

can

be

no

doubt that the moment was

opportune

for

an

enterprise

of the kind. For the concentration

of

resources on

the Antonine Wall

during

the

previous twenty

years

had

inevitably

retarded field research in other

parts

of

Roman

Scotland;

and nowhere

was

the situation

more

unsatis

factory

than in the

south-west, where,

apart

from excavations at

Birrens and

Burnswark,

and the

discovery

of

a

temporary camp

at Little

Clyde, scarcely

any progress

had been made since the

publication

of

Roy's

classic folio.1

Indeed,

in

some

respects

the

position

had

deteriorated,

for

a

number of authentic Roman roads

and fortifications in the

area,

whose true character had been

recognized by Roy,

or

divined

by

less

gifted antiquarian topo

graphers,

had fallen victim to

the

pervasive scepticism

of the late

nineteenth

century,

and had either been

summarily rejected

or

set aside. Thus

a

systematic

re-examination of both known and

putative

Roman sites in the south-west

was

long

overdue,

and

the

Society

was

exceptionally

fortunate in

having

at its command

not

only

an

experienced

team of

field-workers,

but also

a

scholar

of the calibre of the late Mr. S. N.

Miller,

to whom the task of

co-ordinating

and

editing

the various

reports

was

entrusted.

Moreover,

in

1938

unexpected

assistance

was

obtained from

another

quarter

when it

was learned that Dr.

J.

K. St.

Joseph

was

engaged

on a

similar

survey

to that

projected by

the

Society,

in

preparation

for the revised

(third)

edition of the Ordnance

Survey

Map

of Roman Britain.

By

a

happy

arrangement

it

was

agreed

that Dr. St.

Joseph's

detailed

reports

should be

incorporated

in

1

The

Military Antiquities of

the Romans in Britain

(London, 1793).

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

n6 Kenneth Steer

the

Society's

volume,

and in return the

Society

undertook to

defray

the cost of trial trenches on

selected sites.

The scheme thus started under the most

favourable

auspices,

but

even so

the results obtained in the first three

years

exceeded

all

expectations. Discerning ground-observation brought

to

light

new

permanent

forts at

Bothwellhaugh,

Loudoun Hill and

Crawford;

two small

earthworks,

at

Milton and

Durisdeer,

were

excavated and

proved

to be Roman road

posts (fortlets)

of

a

type

already

known at

Chew Green and Kaims

Castle;

and

many

miles

of Roman roads

were

patiently

retrieved from the limbo of lost

reputations

into which

they

had been

consigned.

Nor

was

this

all,

for in

June, 1939,

Dr. O. G. S. Crawford carried out the first

air reconnaissance of Roman sites in Scotland.

Any

doubts that

air-photography,

as an

aid to

archaeological

research,

would lose

its effectiveness

on

transfer from the chalk Downs to the

grimmer

scenery

of the

Highland

zone were at once set at rest. For

although

the subsoil conditions

pertaining

in the

Highland

zone

are,

in

general,

less favourable

to the

preservation

of

crop

markings

in arable than

are

those in the south of

England,

there

is

ample compensation

in the fact that the moorlands and old

grasslands

of Scotland still enshrine hundreds of ancient monu

ments whose

remains,

though

visible on

the

ground,

have not been

recorded for lack of intensive field-work. In these

circumstances,

the

aeroplane obviously

has

an

invaluable role to

play

as a

spotter,

and the

point

was

firmly

driven

hoipe by

Dr. Crawford's

foray

which

produced, amongst

other

things,

a

second fort

at

Birrens;

a

fortlet at

Redshaw

Burn,

in

Annandale;

a

signal-station

near

the

Beef

Tub;

a

temporary camp

at

Galloberry,

in

Nithsdale;

and

a

fort at

Cardean,

in Strathmore. A brief account of the results

of this

epoch-making flight

was

given

at the

time,2 but,

as

in the

case of Dr. St.

Joseph's

researches,

detailed

publication

of the

new

material in the south-west

was

reserved for the

Glasgow

Society's report.

Then the

war

intervened,

not

only

to

interrupt

the

investigation

but also to

suspend

the

publication

of what had

already

been

ascertained;

and

owing

to various misfortunes after

the

war it was not until the end of

1952

that the book

emerged

from the

press.3

2

Antiquity,

xiii

(1939), 280-92.

3

The Roman

Occupation of

South-We stern

Scotland,

being reports

of excavations

and

surveys

carried out under the

auspices

of the

Glasgow Archaeological Society

by John

Clarke,

J.

M.

Davidson,

Anne S.

Robertson,

J.

K. St.

Joseph,

edited for the

Society

with a historical

survey by

S. N. Miller.

Pp.

xx,

246

;

figs.

12,

plates

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Roman Scotland

117

As

was to be

expected,

the book is

a

storehouse of

information,

reflecting

the

greatest

credit

upon

its

contributors,

and will

become

a

standard reference-work for students of Roman Scot

land. The first

section,

which is devoted to a

detailed

description

of the roads from Carlisle to the

Forth,

to

Nithsdale,

from the

Tweed to the

Clyde,

from

mid-Clydesdale

towards the

Ayrshire

coast,

and from

Castledykes

to the

Forth-Clyde

isthmus,

is

admirably

done. The accounts are

lucidly

written,

and the

skilful insertion of

strip-maps,

derived from the Ordnance

Survey

6-inch

sheets,

makes them

easy

to

follow

on

the

ground.

It is

no

exaggeration

to

say

that this contribution has revolutionized

our

knowledge

of the Roman road

system

in

Scotland;

and

even

though

the

system

that

emerges

in the south-west is

manifestly

incomplete

as

it

stands,

numerous

possible

routes are

indicated

for further

study,

and much

sound,

practical

advice is

given

on

how to

distinguish

between Roman and later metalled roads.

Only

one

minor criticism

may

be

offered,

namely

that it is most

unlikely

that the blue

clay lining

observed in the side-ditches of the

road from

Castledykes

to

Collielaw

(p. 71)

was

deliberately

laid

to

render them

watertight: watertight drainage-ditches

would

defeat their

own

purpose,

and

many

instances

are

known where

similar blue

clay

has

developed

from natural

causes,

being

due

either to

leaching

or to the anaerobic conditions induced

by

waterlogging.4

The second of the three main sections which

compose

the

book deals with the

forts,

fortlets and

temporary camps

in the

area,

and

principally

with those which

were

excavated

or

trenched

in the course

of the

survey. Here,

again,

a

considerable amount

of fresh material has been made

available,

but the section is to

some extent weakened

by

the fact that it takes

hardly

any

note of

discoveries made since

1940,

and

by

a

lack of balance in the

treatment of the sites concerned. For

example,

the account of

the unfinished excavations at

Castledykes,

which

occupies

no

less

than

forty-four

pages

and fourteen

plates,

seems to be

unduly

elaborate for

an

interim

report.

On the other

hand,

it is dis

appointing

to find that the

(presumably)

final

reports

on

the

fortlets

at Milton and Durisdeer

are

merely

illustrated in each

case

by

a

ground plan (rampart-sections,

and

a

photograph

of

lxvi.

Glasgow: University

Press,

1952. (Obtainable

from the

Joint

Hon.

Secretary, Glasgow Archaeological Society,

2 Ailsa

Drive,

Glasgow,

S. 2.

45s.).

4

Cf. M.

J. O'Kelly,

Cork Historical and

Archaeological Society Journal,

lvi

(1951), 29-44.

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

118 Kenneth Steer

Durisdeer?one of the most

photogenic

Roman sites in Britain?

might surely

have been

included),

and that neither

plans

nor

photographs

are

provided

for

a

number of

new

discoveries such

as

the

signal-station

on

White

Type,

whose

position

is

only

vaguely

indicated

on

the

map

(PI.

viii

d),

and the fortlet at

Barburgh

Mill. A more

serious

defect, however,

is the inade

quate publication

of the

pottery

from these excavations. For

although large quantities

of Antonine

coarse

pottery

were

found

at

Bothwellhaugh,

Milton,

Durisdeer and

Castledykes,

some of it

in sealed

deposits, only

a

few

representative pieces,

all from

Castledykes,

are

illustrated,

and in no

instance is the

precise

find-spot given.

Yet if the stratified sherds had been

fully

published,

so

that

comparison

could be made with the

closely

datable Antonine

wares

from

Corbridge,

the

history

not

only

of

the sites in

question,

but of Antonine Scotland

as a

whole,

might

be less obscure than it is at

present.

In the

concluding

section Mr. Miller selects the

significant

features from the mass of evidence that has been

presented

in the

previous

pages,

and draws them

together

to form

a

comprehen

sive

picture

of the Roman

occupation

of south-west Scotland.

Those familiar with Miller's

published work?notably

his

reports

on

the excavations at

York,

Balmuildy

and Old

Kilpatrick;

his

survey

of the Roman

Empire

in the first three centuries in

Eyre's

European

Civilization;

and the

chapter

which he contributed to

the latest volume of the

Cambridge

Ancient

History?will

need

no

assurance that the

present essay

is

a

masterly exposition

of both

fact and

deduction,

in which breadth of

judgment

is balanced with

meticulous attention to

detail. It is true that discoveries made

since

1948,

when this section of the book

was

evidently

com

pleted,

have invalidated

a

few of Miller's

conclusions,

while

some

of his

speculations

on

problems

still unsolved will not command

the

support

of all scholars.

Nevertheless,

the

core of the work

remains

sound, and,

in

company

with his other

writings,

con

stitutes

a

worthy

memorial to an

accomplished

scholar and teacher

whose

untimely

death

was a

grievous

loss to Roman studies.

Since

1948, however,

great

strides have been made in

our

knowledge

of Roman Scotland elsewhere than in the south

west. In the hands of Dr. St.

Joseph,

the air

camera has added

large

numbers of

new sites to the

map,

as well

as

revealing

much

fresh information about known

sites;

while

study

of the National

Survey air-photographs

has also

produced

several

major

dis

coveries. Professor Richmond has

reported

on

his excavations

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Roman Scotland

119

at

Newstead and

Cappuck,

and has

begun

a

systematic

examina

tion of the

legionary

fortress at

Inchtuthil;

and Dr. Crawford has

published

his Rhind Lectures

on

The

Topography of

Roman

Scotland,

North

of

the Antonine Wall. All this work has had

a

bearing, directly

or

indirectly,

on

the

problems

of the south

west,

and it seems

fitting

therefore that comment on

Miller's

survey

should take the form of

an assessment of the

present

position

of research

on

Roman Scotland

as a

whole.

Owing

to

considerations of

space,

only

a

broad treatment can

be

attempted,

and the

mere

recital of ascertained

facts,

and of unsolved

problems,

will leave

no

margin

for

adequate

discussion of current contro

versies.

The Flavian

Occupation

Although

recent discoveries at

Milton,

in

Annandale,

suggest

that Roman

troops may

have

penetrated

into that district in the

governorship

of Petillius Cerialis

(a.d. 71-4),

or one of his

immediate

predecessors,

the first

chapter

in the Roman

occupa

tion of Scotland

opens

in a.d. 80

when,

after two

years

prelim

inary campaigning, Agricola's

armies invaded the Lowlands.

One of the most

important

results obtained

during

the

period

under review has been the confirmation of

Roy's hypothesis

that

the armies concerned in this invasion did not

operate

as a

single

column,

but advanced

along

two

major

routes.5 The

Agricolan

date of the Scottish section of Dere

Street,

the

great

eastern

highway

from York to the

Forth,

was

established

long

ago,

and

a

similar

early origin

for the western trunk

road,

running

from

Carlisle

through

Annandale into

upper Clydesdale,

has

now

been

demonstrated

by

discoveries at Birrens and Milton.

Moreover,

the

Glasgow Society's

survey

has shown that the latter road did

not link the Firths of

Solway

and

Clyde,

as

had

previously

been

supposed,

but that it turned north-eastwards

on

crossing

the

watershed into

Clydesdale,

and

ran

along

the southern

slopes

of the Pentlands

to

converge

on

Dere Street in the

neighbourhood

of Inveresk. Thus the initial

strategy

of the

invading

forces

is

seen to have taken the form of

a

pincer-movement

which

was

evidently designed

to

envelop

the

Selgovae, dwelling

in the

tangled

foothills of the central

massif,

and to isolate them from

the other Lowland tribes?the Votadini of

Northumberland,

5

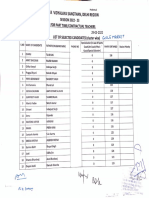

See

accompanying

map.

The writer is indebted

to the

Society

for the Promo

tion of Roman Studies for

permission

to

adapt

this

map

from the one

which

app2ared

in vol. xli of the

Society's Journal.

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WKr?^r%!\. '

*^^^^^^^^^^^^P|

R0MAN SITES IN SCOTLAND I

HSw^ *^*a^^fc?//^ /^ V KA? HOUSE C3 /^llllli^ I]

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

122

Kenneth Steer

Lothian and the

Merse;

the Damnonii of

Clydesdale

and

Ayr

shire;

and the Novantae of Nithsdale and

Galloway.

From

Inveresk,

which was

presumably

one

of the

principal supply

bases for the

expedition,

forward elements moved

across

the

Forth and succeeded in

reaching

the

Tay

before the end of the

summer.

The

rapidity

with which the Lowlands

were

overrun6

was

doubtless made

possible by

lack of

unity,

if not bitter

hostility,

between the tribes

concerned,

for whereas the later

history

of the

Votadini and the Damnonii

implies

that both

were

long-standing

allies of

Rome,

and Roman

goods

were

reaching

the Votadinian

hill-town

on

Traprain

Law in the Flavian

period,

the distribution

of Roman

garrisons

tells

a

very

different

story

of the

Selgovae

and

Novantae.

The next

season,

Tacitus tells

us,

was

devoted

to consolidation

of the

ground already gained.

To this

end,

a

temporary

frontier,

consisting

of

a

chain of stockaded

posts

whose remains have been

found

at Bar

Hill,

Mumrills and

elsewhere,

was set

up

on

the

Forth-Clyde

isthmus,

while behind the frontier the

process

of

cordoning

off the

Selgovae by

means

of

a

network of roads and

forts

proceeded

apace.

It is

probable

that to

this

year

should be

assigned

the construction of the

Agricolan

forts at Newstead and

Cappuck

on

Dere

Street,

at Birrens and Milton

on

the Annandale

road,

at Oakwood in the

valley

of the Ettrick

Water,

at Inveresk

and Cramond

on

the

Forth,

and at

Lyne, Castledykes

and Loudoun

Hill

on

the

important

lateral road that

ran

from Newstead

by way

of the Tweed and middle

Clyde

to reach the west coast some

where in the

neighbourhood

of Irvine. Nor does this list

by any

means

exhaust the

possibilities,

for

a

minor route of

penetration

in this

phase, leading

up

Eskdale from

Netherby,

may

be

repre

sented

by

the fort at

Broomholm,

near

Langholm,

where

early

aurei have been

found,

and

by

the earlier of the two

superimposed

forts at

Raeburnfoot;

while

nothing

is known

as

yet

of the dis

position

of the

Agricolan garrisons

on

the Annandale road

between Milton and Inveresk. In the

following

year (a.d. 82)

Agricola

carried out an

exploration

of the left

flank,

amongst

tribes hitherto

unknown,

and stationed

troops

in

an area

facing

6

It is

significant

that neither of the two

groups

of Roman

siege-works

known in

Scotland

can

be connected with

Agricola's campaigns.

Excavation has shown that

the earthworks which invest the native fort

on

Woden

Law,

Roxburghshire,

were

built

by troops engaged

in

peacetime

manoeuvres.

And,

despite

Miller's remarks

(footnote p. 209),

the two

siege-camps

on

Burnswark?which

may equally

well be

practice camps?must

be referred to a

later

period, assuming

that

they

are contem

porary,

since the south

camp incorporates

a

fortlet of Antonine

type

in its circuit.

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Roman Scotland

123

Ireland. The

scene

of this action has been the

subject

of much

controversy

in the

past,

but there

can now be

no

doubt that it

lay

in

Galloway

or

south

Ayrshire,

and

not in

Argyllshire

or

Kintyre

as some commentators have

supposed.

For recent

air-photograph

discoveries include

a

large

fort at

Dalswinton,

in

Nithsdale,

which

is

presumably

of Flavian date since it is less than three miles

distant from the Antonine fort

at

Carzield;

a

fort at

Glenlochar,

subsequently proved by

excavation to have been founded under

Agricola

and

reoccupied

in the Antonine

period;

and

a

small

fort,

as

yet

undated,

as

far west as

Gatehouse of Fleet.

Having

thus established

a

firm

grip

on

the

Lowlands,

and

secured his land

communications,

Agricola,

in his two final

campaigns,

led his armies

across

the

Forth, and,

warding

off

sporadic

counter-attacks,

eventually compelled

the Caledonians

to

fight

a

pitched

battle at Mons

Graupius

where the

superior

discipline

and tactics of the Roman

troops

carried the

day.

With

the

crossing

of the Forth the terrain

was no

longer

suitable for

the broad

pincer-movements

which had

proved

so

successful

hitherto,

and

a

single

line of advance

was

perforce adopted leading

to Strathmore

by

way

of

Stirling,

Strathallan and Strathearn.

The route taken is

signposted

as

far north

as

Meigle by

the

permanent

forts at

Camelon, Ardoch,

Strageath,

Bertha and

Cardean,

all of which

are

known,

or

presumed,

to be

Agricolan

foundations;

but

none

of the

temporary camps

that

prolong

the

line of Roman

penetration

northwards in

a

wide

arc from the

North Esk to the

Moray

Firth has been

dated,

and it is

possible

that

some,

at

least,

of these

camps

were

constructed in the

course

of the Severan

campaigns

in the

early

third

century.

Nor has the

site of Mons

Graupius

been

identified,

although

there is

general

agreement

with Macdonald's

opinion

that it

lay

north of Strath

more.

Recent research

has, however,

thrown

a

good

deal of

new

light

on

the measures taken

by Agricola

to consolidate his

victory.

The excavations at

present

in

progress

on

the

great camp

at

Inchtuthil,

near

Meikleour,

have

already

substantiated

Colling

wood's

theory7

that the remains

are

those of

a

legionary

fortress

erected in a.d.

83-4

to serve as a

base for the

permanent occupa

tion of

Strathmore;

while the forts

at

Callander,

Dalginross,

Fendoch,

and

perhaps

Steed

Stalls,

fall into

place

as

elements in

a

strategic

cordon

designed

to

protect

the vulnerable left flank of

the terra limitanea

by sealing

off the

Highland

passes.

And since

7

Collingwood

and

Myres,

Roman Britain and the

English

Settlements,

second ed.

(Oxford, 1937), 119.

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

124

Kenneth Steer

this

system

must have been

largely dependent

for its success on

the

transport

of

supplies

and reinforcements

by

sea,

it

can

be

confidently

assumed that the fort of

Carpow,

on

the south bank

of the

Tay estuary,

was

established

at this time to

guard

a

natural harbour.

Beyond

Cardean at least one more

permanent

fort

may

be

presumed,

at the terminus of the road which has been

traced

intermittently

as far as

Kirriemuir,

but it is clear that

Agricola's policy

was to

blockade,

and not to

annex,

the

High

lands.

That Tacitus' famous

phrase

'

perdomita

Britannia et statim

omissa

'

cannot be taken to mean

that

Agricola's conquests

were

immediately

surrendered

on

his

recall,

was

convincingly

demon

strated

by

Macdonald

over

thirty

years

ago.8

But it is now

apparent

that the transfer of

Legio

II Adiutrix from Britain to

Pannonia in a.d.

85

or

86 necessitated

a

reorganization

of the

northern defences which involved the evacuation of the

legionary

fortress

at Inchtuthil and the

auxiliary

fort

at

Fendoch,

and the

consolidation of forts further south.9 The

Agricolan

forts

at Newstead and Milton

were now

completely

rebuilt,

the former

on an

exceptionally

massive

scale,

while alterations

designed

to

strengthen

the

existing

defences

were

undertaken

at

Oakwood,

Cappuck

and elsewhere. This second

phase

in the Flavian

occupation

of Scotland

only

lasted, however,

until about

a.d.

ioo,10 when,

with the

possible exception

of the

garrisons

in

lower

Annandale,

a

general

withdrawal took

place

to the

Tyne

Solway

line. This withdrawal

was

presumably

connected with

the

preparations

for

Trajan's

Dacian

wars of a.d.

101-6,

but

evidence from Newstead and Oakwood shows that in the south

east it

was carried out

hurriedly

and in the face of

strong enemy

pressure.

At

Milton,

on

the other

hand,

the second Flavian fort

was

peacefully

dismantled,

and is

thought

to have been immedi

ately

succeeded

by

a

fortlet.

The Antonine

Occupation

During

the next

forty

years,

trouble in the

Lowlands,

which

may

have been due in

part

to the infiltration of alien elements

8

Journal of

Roman

Studies,

ix

(1919),

n

1-38.

9

Analogies

from the German frontier

suggest

that the chain of wooden watch

towers on the Gask

ridge,

between

Strageath

and

Bertha, may represent

a

frontier

line. If

so,

the Domitianic

reorganization

would

seem to

provide

the most suitable

occasion for the creation of such

a

frontier.

10

For the

date,

which has been the

subject

of

lively disputation

in the

past,

cf.

Proceedings of

the

Society of Antiquaries of

Scotland,

lxxxiv

(1949-50),

26.

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Roman Scotland

125

from the north-east and from

Ireland,

provoked

a

Roman

punitive

campaign

on more

than

one

occasion,

and

eventually

the situation

became

so

serious that between

a.d.

139

and

142

the

region

was

once

again

absorbed into the Roman

province.

Hadrian's Wall

was now

partly

dismantled and

a new

frontier-wall

was con

structed

on

the

Forth-Clyde

isthmus. North of the isthmus the

road to Strathmore

was

reopened

at least as far

as

Ardoch,

and in

the Lowlands the

Agricolan system

of roads and forts

was

largely

restored,1

and

even

extended in some areas. On

general grounds

it seems

likely

that the British dediticii who

were

conscripted

into the Roman

army

about this

time,

and

dispatched

to the

German

frontier,2

were

drawn from the

reconquered

districts,

and two

pieces

of evidence

suggest

that the

Selgovae

may

have

been the chief victims. In the first

place,

the native settlements

and homesteads of second- and

third-century

date,

which

are

such

a

striking

feature of the Votadinian

landscape,

are

notably

absent

from the

territory

of the

Selgovae.

And

secondly,

the fact that

the site of the Flavian fort at

Oakwood

was not

reoccupied

in

this

period,

and that Milton and Raeburnfoot

were now tenanted

only by patrol

units ensconced in

fortlets,

implies

a

relaxation of

the former cordon control in the Ettrick Forest

region.

Never

theless the overall

strength

and

deployment

of the Antonine

garrisons

in the

Lowlands,

concerning

which

a

great

deal has

been learned in the last fifteen

years,

makes it

impossible

to believe

that the

deportation

of the native tribesmen

was on

anything

like

the scale

envisaged by Collingwood.3

For the

auxiliary

forts at

Lyne,

Inveresk, Cramond,

Castledykes,

Loudoun Hill and

Glenlochar

were

rebuilt;

new

forts

were

established at Bothwell

haugh

and

Carzield;

and the lines of

communication,

especially

in Annandale and

Nithsdale,

were further

protected by

fortlets

ranging

from

one

fifth of

an acre to one acre in extent. Recent

research has also furnished

supplementary

reasons for

rejecting

Collingwood's

low estimate of the tactical and

strategical

value

of the Antonine Wall.4 For the

gap

which

was

formerly

believed

to have existed

on

the left flank of the Wall has

now been closed

1

Miller's

suggestion (pp. 221?6)

that Nithsdale

was not

originally

included in

the Antonine scheme of

occupation

does violence

to the

pottery

evidence from

Carzield

{Transactions

of

the

Dumfriesshire

and

Galloway

Natural

History

and

Antiquarian Society, 3rd

Series, xxiv,

i-n),

and in

any

case

is

no

longer

tenable

now that Glenlochar is known to have been held

throughout

the Antonine

period.

2

Germ

ant

a,

vi

(1922),

31-7.

3

Op.

cit., 146-7.

4

Op.

cit., 140-4,

and

Journal of

Roman

Studies,

xxvi

(1936),

80-6. For the

opposite

view,

cf. Richmond's observations in the latter

volume,

190?4.

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

126 Kenneth Steer

by

the

discovery

of

an

Antonine fort

overlooking

the site of

Dumbuck ford at

Whitemoss,

near

Bishopton,

and of

a

survivor

(Lurg Moor)

of the chain of fortlets and

signal-posts

that

evidently

prolonged

the defensive

system

at

least

as

far as

the mouth of the

Clyde estuary.

Similarly,

the

rediscovery

of the

long-lost

fort at

Carriden on the

Forth,

which has

yielded

Antonine

pottery,

shows that

corresponding precautions

were

taken on

the

right

flank to

prevent

the Wall from

being

turned

by

sea-borne land

ings.5

The Antonine frontier

organization

thus bears all the

hall-marks of

a

permanent arrangement,

and can no

longer

be

written off

as a

temporary expedient

which

was

only

intended

to last

'

until the

pacification

of the Lowlands had stood the test

of time \6 On the Wall

itself,

where

comparatively

little work

has been done since

1937,

the most

interesting discovery

is that

the fort at

Duntocher

was

preceded by

a

fortlet also of Antonine

date. This

discovery

is

obviously

of considerable

importance

for the structural

history

of the

limes,

but its

implications

have

still to be worked out.

In

spite

of the

progress

made in the

knowledge

of the

anatomy

of the Antonine

occupation

of

Scotland,

the

history

of the

period

remains obscure at

many

vital

points.

The chief

difficulty

is

that whereas two

periods

of

occupation

have been found in all the

Antonine forts

so

far examined between the two Walls

(with

the

doubtful

exception

of

Carzield),

the Antonine Wall forts exhibit

three

periods;

and it is

not

clear

why

there should be this

difference between the Antonine Wall and its

hinterland,

or

how

the successive

periods

are to be correlated with the evidence

from Hadrian's Wall and fitted into the framework of known

events.

Assuming

that the two

periods

observed in the

Lowland

forts

are to be

equated

with the first two

periods

on

the Antonine

Wall,

the most

plausible explanation

of the break in the

occupa

tion would

seem to be that the entire Roman forces

were

hurriedly

withdrawn from Scotland in

a.d.

155

to

deal with the revolt of

the

Brigantes

in that

year.7

For the renewed advance into

Scotland had

only

been achieved at

the cost of

stripping

the

garrisons

from

Brigantian territory,

and it is known that Birrens

was

destroyed

at this time and

was

rebuilt in a.d.

158

as soon

5

The

supposed

Roman watch-tower at

Inchgarvie (R.C.A.M. Inventory,

Midlothian and West

Lothian,

no.

332)

should be remembered in this connection.

6

Collingwood,

op. cit., 148.

7

This

explanation

was first

propounded by Collingwood, Journal of

Roman

Studies,

xxvi

(1936),

86.

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Roman Scotland

127

as

the insurrection had been crushed. On the other

hand,

a case

can

be made out for

supposing

that,

Birrens

excepted,

the first

Antonine

period

continued until

a.d.

163

when the threat of

a

further

rising brought Calpurnius Agricola

to

Britain,

and

Hadrian's Wall

was once more

put

into commission.8 Whatever

the exact date of the

intermission,

once

the crisis

was over no

time

was

lost in

reoccupying

and

repairing

the abandoned fortifications.

Several

forts,

such

as

Cappuck

and

Ardoch,

were now

reduced in

size but

were

equipped

with more substantial

defences,

while there

are

indications that increased

importance

was now

attached to the

cavalry

arm.

How

long

this

phase

of

occupation

lasted is not

yet

certain. Macdonald linked the second destruction of the

Antonine

Wall, which,

on

his

view,

left the Lowland forts

unscathed,

with the barbarian invasion recorded

by

Dio Cassius

in

a.d.

184,9

and he concluded that the restoration of the frontier

by Ulpius

Marcellus

was

short-lived,

being

followed

a

year

or

two

later,

by

the evacuation of the whole of Scotland

apart

from

Birrens.

Others, however,

would

postpone

the evacuation

until

a.d.

196

when Clodius Albinus transferred the bulk of the

British

garrison

to the continent in

pursuit

of his bid for the

imperial

throne,

and the Maeatae seized the

opportunity

to break

into the defenceless

province.

There

is,

in

fact,

no

evidence

as

yet

for the

precise

date of the

event,

although

the latest

pottery

from the Antonine Wall is said to

correspond closely

with the

vessels which

occur in the destruction

deposits

of a.d.

197

at

Corbridge.10

The Severan

Campaigns

As

soon as he had defeated Albinus at

Lyons

in a.d.

197,

the

new

emperor, Septimius

Severus,

sent Virius

Lupus

to Britain

to

repair

the shattered northern

defences;

and from a.d.

209-11,

Severus,

accompanied by

his sons

Caracalla and

Geta,

personally

conducted

a

series of

punitive campaigns

in Scotland?first

against

the Caledonians of Aberdeenshire and

beyond,

and then

against

the Maeatae of

Strathearn,

Strathmore and the Mearns.

It has

already

been

suggested

that

some

of the

temporary camps

in these

regions

may

have been built at this

time,

but

apart

from

Cramond,

which served

as an

advanced

supply-base

for the

expeditions,

and

Birrens,

which

was

reconstructed

as an

outpost

8

Cf.

J.

P.

Gillam,

*

Calpurnius Agricola

',

Transactions

of

the Architectural and

Archaeological Society of

Durham and

Northumberland,

x

(1953), 359-75.

9

lxxiii,

8.

10

Gillam,

loc.

cit.,

367.

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

128 Kenneth Steer

of Hadrian's

Wall,

no

Scottish fort has

so

far

produced

any

proof

of

occupation

after the end of the second

century.

It is true that

Miller

(pp. 235-9)

and Mr. Eric

Birley1

have

argued,

on some

what different

grounds,

that the third

period

of

occupation

on

the

Antonine Wall was

initiated

by

Severus and not

by Ulpius

Marcellus,

but at

present

this

theory

lacks

support

from the

archaeological

evidence. Miller's

appeals

to the Falkirk coin

hoard and the Dolichenus relief from

Croy

Hill

(p. 238)

do not

help

the

case,

since the hoard extends down to Severus Alexander

(a.d. 222-35),

while Dolichenus

was

already being worshipped

on

Hadrian's Wall in the

reign

of Antoninus Pius. Yet all

are

agreed

that

on

Severus' death in a.d. 211

the Roman command

finally

abandoned the

Agricolan

and Antonine

policies

of extend

ing

direct control

over

the

Lowlands,

in favour of

a

system

of

indirect control

through

the medium of buffer-states. The aims

and achievements of the New

Deal,

which had

profound

con

sequences

for Roman and native relations in the third and fourth

centuries, lie, however,

outside the

scope

of this review.

Bibliographical

Note

The above

survey

is

largely

based

on

excavation

reports

which

are to

be

found,

or

will

shortly

appear,

either in the

Proceedings of

the

Society

of Antiquaries of

Scotland

or in the Transactions

of

the

Dumfriesshire

and

Galloway

Natural

History

and

Antiquarian Society.

Some of the

books and more

general

papers

consulted have been cited in the

text,

and to these should be added: E. B.

Birley,'

Dumfriesshire in Roman

Times

'

{Transactions

of

the

Dumfriesshire

and

Galloway

Natural

History

and

Antiquarian Society,

Third

Series,

xxv,

132-50),

and

'

The

Brigantian

Problem'

(ibid.,

xxix, 46-65); J.

K. St.

Joseph,

'Air

Reconnaissance of North Britain

'

{^Journal of

Roman

Studies,

xli

(1951), 52-65);

I. A.

Richmond,

'Recent Discoveries in Roman

Britain from the Air and in the Field

'

(ibid.,

xxxiii

(1943), 45-54),

and

'

Gnaeus Iulius

Agricola' (ibid.,

xxxiv

(1944), 34-45).

Kenneth Steer.

1

Proceedings of

the

Society of Antiquaries of Scotland,

lxxii

(1937-8),

343-4.

This content downloaded from 147.143.2.5 on Sun, 11 Aug 2013 07:23:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Вам также может понравиться

- Changelog DCДокумент55 страницChangelog DCDaniel LucaОценок пока нет

- Pedagogie, Nadia Mirela FloreaДокумент296 страницPedagogie, Nadia Mirela FloreasorelinoОценок пока нет

- Valerie Hope, Trophies and TombstonesДокумент20 страницValerie Hope, Trophies and TombstonesIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Richmond, 4 Roman Camps at CawthornДокумент93 страницыRichmond, 4 Roman Camps at CawthornIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- 100 Personalitati Care Au Schimbat Destinul Lumii - KennedyДокумент32 страницы100 Personalitati Care Au Schimbat Destinul Lumii - Kennedylandmd09Оценок пока нет

- Richard Reece, Town and Country, The Ened of RBДокумент17 страницRichard Reece, Town and Country, The Ened of RBIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Walters, 2 R Finger RingsДокумент4 страницыWalters, 2 R Finger RingsIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Culegere de Bancuri Romanesti Volumul 2Документ141 страницаCulegere de Bancuri Romanesti Volumul 2dualqq100% (13)

- Chapman Et Al, RB in 2008Документ147 страницChapman Et Al, RB in 2008Ionutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Von Perikovits, NW Roman Empire Fortifications 3rd To 5th C ADДокумент44 страницыVon Perikovits, NW Roman Empire Fortifications 3rd To 5th C ADIonutz Ionutz100% (1)

- Smith, Roman Place Names in Lancashire and CumbriaДокумент13 страницSmith, Roman Place Names in Lancashire and CumbriaIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Thould and Thould, Arthritis in RBДокумент4 страницыThould and Thould, Arthritis in RBIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Richard Reece, Roman CurrencyДокумент9 страницRichard Reece, Roman CurrencyIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Splitting the Difference or Taking a New Approach to Roman Britain's DeclineДокумент4 страницыSplitting the Difference or Taking a New Approach to Roman Britain's DeclineIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Roman Coins from Fourteen British SitesДокумент13 страницRoman Coins from Fourteen British SitesIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Richard Reece, Roman Coinage in Western EmpireДокумент36 страницRichard Reece, Roman Coinage in Western EmpireIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Richard Reece, Interpreting Roman HoardsДокумент10 страницRichard Reece, Interpreting Roman HoardsIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Richard Reece, Roman CoriniumДокумент6 страницRichard Reece, Roman CoriniumIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Richard Reece, Coin Collection From RomeДокумент31 страницаRichard Reece, Coin Collection From RomeIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Reece and Dunnett, Excavation of Theatre at GosbecksДокумент27 страницReece and Dunnett, Excavation of Theatre at GosbecksIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Mattingly, Roman Gold CoinsДокумент4 страницыMattingly, Roman Gold CoinsIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- P Topping, New Signal Station in CumbriaДокумент4 страницыP Topping, New Signal Station in CumbriaIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Mackreth, RB Brooch, NorfolkДокумент15 страницMackreth, RB Brooch, NorfolkIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- P Bartholomew, 4thC SaxonsДокумент18 страницP Bartholomew, 4thC SaxonsIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- Mattingly, Roman CoinsДокумент4 страницыMattingly, Roman CoinsIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- JD Hill, Pre-Roman Iron AgeДокумент53 страницыJD Hill, Pre-Roman Iron AgeIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- P and A Woodward, Urban Foundation Deposits in RBДокумент20 страницP and A Woodward, Urban Foundation Deposits in RBIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- M PITTS, Utility of Identity in Roman ArchaeologyДокумент22 страницыM PITTS, Utility of Identity in Roman ArchaeologyIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- King, Animal Remains From Temples in RomanBritainДокумент42 страницыKing, Animal Remains From Temples in RomanBritainIonutz IonutzОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Punjab Public Service Commission, Lahore: NoticeДокумент4 страницыPunjab Public Service Commission, Lahore: NoticeZawar HussainОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Philippine LIteratureДокумент4 страницыIntroduction To Philippine LIteratureRiza VillanuevaОценок пока нет

- (Lib24.vn) 14-De-Thi-Thu-Tn-Thpt-2021-Mon-Tieng-Anh-Bo-De-Chuan-Cau-Truc-Minh-Hoa-De-14-File-Word-Co-Loi-GiaiДокумент18 страниц(Lib24.vn) 14-De-Thi-Thu-Tn-Thpt-2021-Mon-Tieng-Anh-Bo-De-Chuan-Cau-Truc-Minh-Hoa-De-14-File-Word-Co-Loi-GiaiThi Na ThachОценок пока нет

- Imagery in : MacbethДокумент2 страницыImagery in : MacbethMaffy MahmoodОценок пока нет

- Mspo TraceДокумент44 страницыMspo TraceAl IkhwanОценок пока нет

- I.C. Via MAFFI ROMA Graduatoria - Istituto - III Fascia - ATA - Privacy (Albo)Документ314 страницI.C. Via MAFFI ROMA Graduatoria - Istituto - III Fascia - ATA - Privacy (Albo)rsueuropawoolf8793Оценок пока нет

- Koshi MergedДокумент23 страницыKoshi MergedswyizqngcnaqbjeyleОценок пока нет

- Batang HeneralДокумент2 страницыBatang HeneralissaiahnicolleОценок пока нет

- Commentary On Genesis 45,1-15.howardДокумент3 страницыCommentary On Genesis 45,1-15.howardgcr1974Оценок пока нет

- Notebook Export HHRSQJGQTYOL 1675198389405Документ21 страницаNotebook Export HHRSQJGQTYOL 1675198389405Angelina NguyenОценок пока нет

- VISTA VERDE - T2 - ViettelДокумент3 страницыVISTA VERDE - T2 - ViettelHữu Thiên NguyenОценок пока нет

- The Unity of IsaiahДокумент140 страницThe Unity of IsaiahAlan Siu Kuen WongОценок пока нет

- Assess horse form and ratings with THE CURTIS RATING SYSTEMДокумент1 страницаAssess horse form and ratings with THE CURTIS RATING SYSTEMFloat KgbОценок пока нет

- Merry Christmas or Happy Sabbath!Документ3 страницыMerry Christmas or Happy Sabbath!SonofManОценок пока нет

- Q Skills For Success Reading and Writing 5 2nd EditionДокумент272 страницыQ Skills For Success Reading and Writing 5 2nd EditionHoa NguyễnОценок пока нет

- Guy Fawkes and Bonfire NightДокумент13 страницGuy Fawkes and Bonfire NighttomeualoyОценок пока нет

- Giovanni Maria Trabaci, Gagliarda QuintaДокумент2 страницыGiovanni Maria Trabaci, Gagliarda QuintaErhan Savas100% (1)

- Final List Update PDFДокумент44 страницыFinal List Update PDFKaushal TiwariОценок пока нет

- Intimate story leaves readers wanting moreДокумент4 страницыIntimate story leaves readers wanting moreSAM DASОценок пока нет

- Lat Bhairav and Gazi MiyanДокумент38 страницLat Bhairav and Gazi Miyanrajendra_giriaОценок пока нет

- Staff ListДокумент3 страницыStaff ListMichael BriggsОценок пока нет

- Roster MAN 1 Madina T.P. 2023-2024Документ17 страницRoster MAN 1 Madina T.P. 2023-2024Nabila Zahra LubisОценок пока нет

- Camp Minsi - Trail MapДокумент1 страницаCamp Minsi - Trail MapCamp MinsiОценок пока нет

- A. C. Kak and Malcolm Slaney, Principles of Computerized Tomographic ImagingДокумент1 страницаA. C. Kak and Malcolm Slaney, Principles of Computerized Tomographic ImagingSerchius ZolotareusОценок пока нет

- UppppДокумент11 страницUpppppiyush sharmaОценок пока нет

- Philfolkdanceppt 170626115635Документ23 страницыPhilfolkdanceppt 170626115635marvin agubanОценок пока нет

- Jose Muñoz - Bruna LayosДокумент12 страницJose Muñoz - Bruna LayosjoeydelacОценок пока нет

- Central University of Rajasthan, Kishangarh-305802Документ8 страницCentral University of Rajasthan, Kishangarh-305802Mukesh BishtОценок пока нет

- IllusДокумент5 страницIllusSashimiTourloublancОценок пока нет

- Makkah Ber Product Lahore 2018 ListДокумент20 страницMakkah Ber Product Lahore 2018 ListAli PapuОценок пока нет