Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Philosophy As A Kind of Cinema: Introducing Godard and Philosophy

Загружено:

utilsc0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

15 просмотров9 страницcinema

Оригинальное название

209-420-4-PB

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документcinema

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

15 просмотров9 страницPhilosophy As A Kind of Cinema: Introducing Godard and Philosophy

Загружено:

utilsccinema

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 9

Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy | Revue de la philosophie franaise et de langue franaise

Vol XVIII, No 2 (2010) | jffp.org | DOI 10.5195/jffp.2010.209

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No

Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh

as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program, and is co-sponsored by the

University of Pittsburgh Press

Philosophy as a Kind of Cinema

Introducing Godard and Philosophy

John E. Drabinski

Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy - Revue de la philosophie franaise et de

langue franaise, Vol XVIII, No 2 (2010) pp 1-7.

Vol XVIII, No 2 (2010)

ISSN 1936-6280 (print)

ISSN 2155-1162 (online)

DOI 10.5195/jffp.2010.209

http://www.jffp.org

Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy | Revue de la philosophie franaise et de langue franaise

Vol XVIII, No 2 (2010) | jffp.org | DOI 10.5195/jffp.2010.209

Philosophy as a Kind of Cinema

Introducing Godard and Philosophy

John E. Drabinski

Amherst College

Space has inscribed itself on film in another form, which is

not a whole anymore, but a sum of translations, a sum of

feelings which are forwarded, that is, time.

- Godard, Ici et ailleurs

Jean-Luc Godard is nothing if not an enigma. His image has a life of its

own, especially in its younger form: cigarette, sunglasses, smirk, rambling

revolutionary slogans, and important books. It wasnt just an image, we all

know, for it reflected perfectly in iconic image the more substantial

revolutionary recklessness with the camera we see from Breathless forward.

Filmmaking is never the same after Godard. Images and their sequencing

Godard cloaked them in sunglasses and made them smirk. He made them

revolutionary. Thats his thing. And even the older Godard makes for an

iconic photograph: rough facial hair, the artists glasses, smirk, and

important books. His films continue to be unpredictable, compelling, and

revolutionary.

It never hurts to be handsome and charming in photographs. Iconic

presence and attitude move the eyes and mind. Cinema, after all, is that

peculiar blend of image and publicity, often too blended at the expense of

the art form commercialism and fame. For cinema is of course also an art,

crafted in the intersection of technology and the human imagination, whose

possibility is tied to the limitations and possibilities of both. Something

about Godards genius overrides his iconic pose. Sure, he works outside the

major studio system and mass cultural venues even for television, he

would produce the unnerving and complex France/tour/dtour/deux/enfants

and he has that signature cinematic voice, but Godards genius and enigma

is tightly bound up with the ideas he brings to sound and image. His cinema

and cinematic language is philosophical. Iconic pose, charisma, style, and

2 | P h i l o s o p h y a s a K i n d o f C i n e m a

Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy | Revue de la philosophie franaise et de langue franaise

Vol XV, No 1 (2010) | jffp.org | DOI 10.5195/jffp.2010.209

important books. Just as there is Godard the icon and the iconic shots, faces,

and angles in his films, there is also the look and charm of big ideas: Godard

moves from icon to thinker. Important books accompany so many important

moments in Godards work; we see works by Derrida, Bataille, Merleau-

Ponty, Levinas, and others. The books signal ideas, of course, and provide a

complicated map of detours, fragmentations, and even just edifications.

Why Derridas Of Grammatology? What is evoked by Levinas Entre Nous at

the moment of crisis in Notre Musique? And so on. Many of those moments

have been written up by theorists and commentators. Many more stand in

need of more attention.

Books mean something in Godard, and it is interesting to note how

many of those featured books bear the name of a philosopher. It is enough to

consider Jean-Luc Godard as filmmaker and innovator of cinematic

technique and trend. That is plenty, for the immensity and intensity of his

cinephilia, technical innovation, and infusion of the art of cinema with

quirky, often radical politics offers an intellectual a lifetime of work. Indeed,

we could say that even the finest work written about Godards cinema is

itself always only a beginning. Who would pretend to have exhausted the

meaning of his films? No one. There is more to be said, more films to see,

more nuance to explode into fully developed aesthetics and politics. The old

man is still making films. Those films still call for commentary.

Tracking Godards references and allusions whether in a shot, a book

on the margins of the frame, a turn of phrase, or a whole sequence and

montage is surely plenty thought about his cinema. There is some of that

in the pages below. Yet, as a general feature, the essays collected in this

volume begin a slightly different conversation, one begun, from the very

beginning, inside Godards cinematic work itself. Four guiding questions.

What does Godards work have to say about philosophy? What does or can

J o h n E . D r a b i n s k i | 3

Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy | Revue de la philosophie franaise et de langue franaise

Vol XVIII, No 2 (2010) | jffp.org | DOI 10.5195/jffp.2010.209

philosophy say about Godards work? Or, further even, how can we see

Godards work as itself a form of philosophy?

1

Can philosophy be a kind of

cinema? Philosophers talk about film. Film theorists talk about philosophy.

But part of what is important in thinking through cinema and philosophy is

the problem of the question: what does it mean to think cinema and

philosophy at the same time, rather than in instrumental terms that would

simply lay philosophical concepts over a film or series of shots?

Perhaps philosophy and cinema form an important language for fashioning

the very ideas we call philosophical. Consider, for example, what Gilles

Deleuze has to say about Godard in a short interview discussion of

Nietzsche from 1968. Deleuzes concern in this remark is the fate of the

image how the image functions in philosophy as a site of critique, but also

as a critical site for intervention against the Western traditions obsession

with certain metaphysical notions of reality. This provokes a remark on

Godards cinema, as Deleuze claims:

Godard transforms cinema by introducing thought into it. He

doesnt have thoughts on cinema, he doesnt put more or less valid

thought into cinema; he starts cinema thinking, and for the first

time, if Im not mistaken. Theoretically, Godard would be capable

of filming Kants Critique or Spinozas Ethics, and it wouldnt be

abstract cinema or a cinematographic application. Godard knew

how to find both a new means and a new image which

necessarily presupposes revolutionary content. So, in philosophy,

were all experiencing this same problem of formal renewal.

2

4 | P h i l o s o p h y a s a K i n d o f C i n e m a

Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy | Revue de la philosophie franaise et de langue franaise

Vol XV, No 1 (2010) | jffp.org | DOI 10.5195/jffp.2010.209

It is difficult to know what he has in mind here, as Deleuze makes these

remarks just as Godard floods the film world with a series of important

films, including Week-end, 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her and Le Chinoise,

following Masculin-fminin, Made in U.S.A, and Pierrot le fou in the years just

prior to mention only a handful. Those are all provocative films, inventive

and quirky, yet we could say that Deleuzes characterization of Godard is as

prophetic as it is descriptive. In the decades that follow Deleuzes remarks,

Godard composed some of the most challenging, self-reflective, self-critical,

and highly theoretical works in his oeuvre. Difficult works like Comment a

va? and Numro Deux, put together in that decade following, function more

like essays than interrupted narratives, and the self-critique we find in films

such as Ici et ailleurs and others, where the problem of representing the Other

is put in such stark terms, sit squarely within the troubled, anxious, and

urgent philosophical tasks of the 1970s in France and elsewhere. What is

shown as a philosophical promise in the late-1960s becomes philosophy

brought to a dense, polysemic cinematic language in the 1970s and after. If

philosophy, as Deleuze has it, is primarily concerned with the creation of

concepts, then Godards cinema can be said to create concepts in sound and

image that other, altogether neglected, mode of philosophizing.

Now, lets pause and consider whats really at stake in cinema as a kind

of philosophy. Deleuze is making a genuinely incredible claim here, even if

it is still suggestive and not yet systematic (though his scattered treatments

on Godard in the two Cinema books help flesh out this claim). According to

Deleuze, it is not simply that philosophy might be an especially rich site for

reflection in Godards cinema, but that a philosophical work itself is or could be

produced in Godards deployment of the image. In the context of Deleuzes

work, of course, this makes perfect sense and embodies his claim that the

task of philosophy lies in the creation of concepts, not faithful (conventional)

interpretations of texts and rehashing the tradition alone. Cinema, in that

context, is a perfectly and reasonably viable candidate for the creation of

concepts at the level of image and sound. And so cinema is also a candidate

for a medium that does, and therefore invents, philosophy. But it means that

philosophy is not wielded as an interpretative instrument, overwhelming

the unicity of the cinematic work with an alien set of ideas. Rather, cinema is

a kind of philosophy. Philosophy is a kind of cinema.

Let us assume Deleuze is right in his characterization. What this

would mean, of course, is that we philosophically-minded commentators

have to re-strategize our reading of Godards work; it is not enough to apply

philosophy to his films or detect an idea or two in the cracks of a given

montage or character. We have to address Godards cinema as philosophical

discourse. To that end, and within that frame, the following essays gathered

by my co-editor Burlin Barr and me take up three general strategies for

thinking Godard as philosophy. In these strategies we see important

possibilities in the chiasmic meeting of philosophy and cinema. First, there is

J o h n E . D r a b i n s k i | 5

Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy | Revue de la philosophie franaise et de langue franaise

Vol XVIII, No 2 (2010) | jffp.org | DOI 10.5195/jffp.2010.209

the strategy of engaging Godards cinematic play and language with

particular philosophers here, Deleuze , Flix Guattari, and Alain Badiou

which produces a portrait of Godards image and sound alongside

contemporary theorists. What does the philosopher have to say to cinema?

And what does cinema say to the philosopher? Second, there is the question

of how cinematic language functions as a transmission of meaning, meaning

that can register across the philosophical spectrum, asking questions of

language, writing, history, and so on. How does cinema function as a

theoretical discourse? How are we to theorize cinematic language and its

transmission of affect, concept, and the lesson(s) of ideas? And third, there is

the question of where to situate Godard in terms of larger philosophical (and

broadly theoretical) endeavors. How does Godard relate to the history of

film and poetics more generally? And how is that relation the condition for

the possibility of his crafting a singular image?

The essays below by David Sterritt and Michael Walsh put Godards

work in conversation with the critical works of Deleuze, Guattari, and

Badiou. Sterritts essay Schizoanalyzing Souls: Godard, Deleuze, and the

Mystical Line of Flight, which opens our collection, takes up the resonance

of Godards cinematic work and principles in Deleuze and Guattari,

describing the image as, in the latters turn of phrase, the link between man

and the world. In particular, Sterritt shows how Godards 1985 film Hail

Mary works through the problem of materiality in opposition to the abstract

in the recasting of Mary as incarnate, desiring, and holy, and therefore Mary

as operating in the plane of immanence. For Walsh in his Happiness is Not

Fun: Godard, the 20

th

Century, and Badiou, it is Badious work that

resonates across so much of Godards work, ranging from the films of the

1960s up through a cluster of recent short works, especially the enigmatic

6 | P h i l o s o p h y a s a K i n d o f C i n e m a

Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy | Revue de la philosophie franaise et de langue franaise

Vol XV, No 1 (2010) | jffp.org | DOI 10.5195/jffp.2010.209

short film De LOrigine du XXIe Sicle. With special attention to Badious

work on the same theme, Walsh examines how the notion of the century

gathers together so many important sites between Godard, Lacan, and

Badiou, all of which are instructive for those working in cinema or

philosophical inquiry more widely. In both essays, what we see is how the

conceptual apparatus of a given thinker functions like theoretical discourse

always functions: to illuminate what could not quite be seen otherwise.

Cinema enacts its own particular transmission of philosophical

meaning; the play of sound, image, and the frame provide the architecture

for another sort of theoretical language. In developing and exploiting the

possibilities of this language, Godard is of course complex and often

perplexing. David Wills essay The Audible Life of the Image tracks

Godards use of sound as its own kind of image. Through a meticulous

reading of Godards vanishing of the visual, with particular emphasis on

Histoire(s) du cinma and loge de lamour, Wills shows how cinematic

language, in Godards hands, produces meaning in the aural, which both

interrupts the visual and works outside the visible economy of image

making. In his Shot and Counter-Shot: Presence, Obscurity, and the

Breakdown of Discourse in Godards Notre Musique, Burlin Barr examines

how the play of shot and counter-shot produces a peculiar transmission of

meaning through historical, memorial, and, ultimately, provocatively

political signs and signification. The result, in Barrs analysis of Notre

Musique, is a cinematic work and discourse whose force and meaning

derives from the play of interruptions. Jonathan Lahey Dronsfield takes a

different, if intimately related, approach by emphasizing Godards explicit

and sometimes exhausting citation of written texts. What are the sources

of Godards work and how do those sources function in his cinematic

productions? Dronsfields essay, Pedagogy of the Written Image, takes

these citations as an initial point of departure, developing from that point a

larger theory of how the written image intertexts, photographed books,

blackboards, and so on intervenes in Godards work as its own kind of

image, untethered (and so more radical in its function) from the expected

play of moving image and sound. From Wills, Barr, and Dronsfield, we see

the seriousness and subtlety of Godards approach to cinematic language as

a site of the transmission of affect and idea which is to say, Godards

production of philosophy and a philosophical discourse in sound, image,

and frame.

Gabriel Rockhills Modernism as a Misnomer: Godards Archeology of

the Image, the essay that closes our collection, offers a broad take on the

meaning of Godards revolutionary rethinking of the image. Through an

extended meditation on and dialogue with Baudelaires aesthetics, Rockhill

circles around much of Godards early work Breathless in particular in

order to document Godards struggle to craft another sort of image that is

both experimental and innovative, but one that also rediscover[s] the

J o h n E . D r a b i n s k i | 7

Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy | Revue de la philosophie franaise et de langue franaise

Vol XVIII, No 2 (2010) | jffp.org | DOI 10.5195/jffp.2010.209

essential power of cinema by returning to it origins. In this treatment of

Godard, Rockhill is able to situate Godard in that difficult space which

defines so much of twentieth century philosophys attempt to renew itself

with modesty and a robust sense of finitude: aesthetic strategy, the time of

the image, and the aspirations and failures of modernism as a poetic project.

*

In all, then, this collection is the beginning of a conversation. It is the

beginning of a philosophical conversation whose orientation is complex

from the beginning, entwined as it is in the complex theoretical questions of

the meaning of commentary and the transcendent, provocative address from

Godards films themselves. And yet there is absolute clarity on the most

crucial issue: between spectator and film, Godard produces a certain kind of

philosophy. Cinema as a kind of philosophy. Yes. But also philosophy as a

kind of cinema.

1

I outline my assessment of this possibility in Cinema as a Kind of Philosophy, which functions

as the Introduction to Godard Between Identity and Difference (New York: Continuum,

2008).

2

Gilles Deleuze, On Nietzsche and the Image of Thought, trs. Michael Taormina, in Desert

Islands and Other Texts (1953-1974). (New York: Semiotext(e), 2004), 141.

Вам также может понравиться

- "A Study Guide for Pablo Neruda's ""Ode to a Large Tuna in the Market"""От Everand"A Study Guide for Pablo Neruda's ""Ode to a Large Tuna in the Market"""Оценок пока нет

- Review Badiou HappinessДокумент7 страницReview Badiou HappinessArashBKОценок пока нет

- You'd Have To Be Stupid Not To See That': ParallaxДокумент14 страницYou'd Have To Be Stupid Not To See That': ParallaxMads Peter KarlsenОценок пока нет

- Phenomenology of Spirit Is One of A Small Number of Books From The Nineteenth Century ThatДокумент3 страницыPhenomenology of Spirit Is One of A Small Number of Books From The Nineteenth Century ThatBenjamin Seet100% (1)

- Beyond Dogmatic Finality: Whitehead and The Laws of NatureДокумент15 страницBeyond Dogmatic Finality: Whitehead and The Laws of NatureChristopher CannonОценок пока нет

- PHL 590-301, ThompsonДокумент2 страницыPHL 590-301, ThompsonCharlotte MackieОценок пока нет

- Kant, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche On The Morality of PityДокумент17 страницKant, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche On The Morality of PityArcticОценок пока нет

- !ReadMe - Philosophy by AuthorДокумент4 страницы!ReadMe - Philosophy by Authormorefloyd100% (1)

- Deleuze Vs Badiou On LeibnizДокумент16 страницDeleuze Vs Badiou On LeibnizslipgunОценок пока нет

- Nico Baumbach Jacques Ranciere and The Fictional Capacity of Documentary 1 PDFДокумент17 страницNico Baumbach Jacques Ranciere and The Fictional Capacity of Documentary 1 PDFCInematiXXXОценок пока нет

- B, JДокумент155 страницB, JGustavo NogueiraОценок пока нет

- How Plausable Is Nietzsche's Critique of Conventional MoralityДокумент7 страницHow Plausable Is Nietzsche's Critique of Conventional MoralityJonny MillerОценок пока нет

- Lecture 4: From The Linguistic Model To Semiotic Ecology: Structure and Indexicality in Pictures and in The Perceptual WorldДокумент122 страницыLecture 4: From The Linguistic Model To Semiotic Ecology: Structure and Indexicality in Pictures and in The Perceptual WorldStefano PernaОценок пока нет

- Complexul OedipДокумент6 страницComplexul OedipMădălina ŞtefaniaОценок пока нет

- Eduardo Pellejero, Politics of Involution PDFДокумент11 страницEduardo Pellejero, Politics of Involution PDFEduardo PellejeroОценок пока нет

- Lorna Collins and Elizabeth Rush (Eds) : Making SenseДокумент256 страницLorna Collins and Elizabeth Rush (Eds) : Making SenseAlmudena Molina MadridОценок пока нет

- Crowds DeleuzeДокумент25 страницCrowds DeleuzebastantebienОценок пока нет

- 2Q:Klwhkhdgdqg'Hohx) H7Kh3Urfhvvri0Dwhuldolw/: Configurations, Volume 13, Number 1, Winter 2005, Pp. 57-76 (Article)Документ21 страница2Q:Klwhkhdgdqg'Hohx) H7Kh3Urfhvvri0Dwhuldolw/: Configurations, Volume 13, Number 1, Winter 2005, Pp. 57-76 (Article)Alex DeLargeОценок пока нет

- The Lives of OthersДокумент3 страницыThe Lives of OthersAjsaОценок пока нет

- The Case of Peter Eisenman and Bernard TschumiДокумент258 страницThe Case of Peter Eisenman and Bernard TschumiRishmaRSОценок пока нет

- Bertell Ollman - Dance of The Dialectic - Steps in Marx's MethodДокумент59 страницBertell Ollman - Dance of The Dialectic - Steps in Marx's MethodfroseboomОценок пока нет

- MCSTAY Privacy and Philosophy New Media and Affective ProtocolДокумент197 страницMCSTAY Privacy and Philosophy New Media and Affective ProtocollectordigitalisОценок пока нет

- Madeleine FaganДокумент50 страницMadeleine FaganCarlos RoaОценок пока нет

- Blanchot, Philosophy, Literature, PoliticsДокумент12 страницBlanchot, Philosophy, Literature, PoliticsElu ValerioОценок пока нет

- Fredric Jameson, Badiou and The French Tradition, NLR 102, November-December 2016Документ19 страницFredric Jameson, Badiou and The French Tradition, NLR 102, November-December 2016madspeterОценок пока нет

- Interpretation and Objectivity: A Gadamerian Reevaluation of Max Weber's Social ScienceДокумент12 страницInterpretation and Objectivity: A Gadamerian Reevaluation of Max Weber's Social ScienceÀrabe CronusОценок пока нет

- Koepnick, Fascist Aesthetics Revisited (1999)Документ23 страницыKoepnick, Fascist Aesthetics Revisited (1999)Dragana Tasic OtasevicОценок пока нет

- Derrida, Passe PartoutДокумент7 страницDerrida, Passe PartoutLaura Leigh Benfield BrittainОценок пока нет

- Nietzsche S Critique of MoralityДокумент16 страницNietzsche S Critique of MoralityElisaОценок пока нет

- A Close Reading of Georg Simmel's Essay How Is Society Possible The Thought of The Outside and Its Various IncarnationsДокумент16 страницA Close Reading of Georg Simmel's Essay How Is Society Possible The Thought of The Outside and Its Various IncarnationsdekknОценок пока нет

- German Idealism - ExistentialismДокумент71 страницаGerman Idealism - ExistentialismBeverlyn JamisonОценок пока нет

- Capital v1Документ188 страницCapital v1MTOzОценок пока нет

- Therness and Deconstruction in Jacques Derrida (#759752) - 1174771Документ7 страницTherness and Deconstruction in Jacques Derrida (#759752) - 1174771Muhammad SayedОценок пока нет

- Puppet Theater in Plato's CaveДокумент12 страницPuppet Theater in Plato's CaveAllison De FrenОценок пока нет

- Ica 2013 ProgramДокумент52 страницыIca 2013 Programcristihainic7449Оценок пока нет

- The Role of Lacanian Psychoanalysis in The Problem of Sexual DifferenceДокумент9 страницThe Role of Lacanian Psychoanalysis in The Problem of Sexual DifferenceJack MitchellОценок пока нет

- Foucault - The Langauge of SpaceДокумент264 страницыFoucault - The Langauge of SpaceAli Reza ShahbazinОценок пока нет

- Contemporary PluralismДокумент8 страницContemporary PluralismTerence BlakeОценок пока нет

- Whitehead and Religion: How His Concept Differs From The Traditional ApproachДокумент16 страницWhitehead and Religion: How His Concept Differs From The Traditional ApproachPaul ChapmanОценок пока нет

- Roberto Esposito - Institution (2022, Polity) - Libgen - LiДокумент124 страницыRoberto Esposito - Institution (2022, Polity) - Libgen - Liyijing.wang.25Оценок пока нет

- Introna KДокумент44 страницыIntrona KMichael LiОценок пока нет

- Space and Society: Dr. Zujaja Wahaj Topic: David Harvey's Theory of Time-Space Compression (Part II)Документ27 страницSpace and Society: Dr. Zujaja Wahaj Topic: David Harvey's Theory of Time-Space Compression (Part II)GulshaRaufОценок пока нет

- Eric Alliez-The Grace of The UniversalДокумент6 страницEric Alliez-The Grace of The Universalm_y_tanatusОценок пока нет

- Gabriela Mistral The Teaching Journey of A Poet PDFДокумент214 страницGabriela Mistral The Teaching Journey of A Poet PDFAlexander CorreaОценок пока нет

- Nelson Goodman Winget NotationДокумент30 страницNelson Goodman Winget NotationagustingsОценок пока нет

- Foucault and Deleuze: Making A Difference With NietzscheДокумент18 страницFoucault and Deleuze: Making A Difference With Nietzschenonservi@mОценок пока нет

- Veena Das The Ground Between Anthropologists Engage Philosophy - Pgs. 288-314Документ27 страницVeena Das The Ground Between Anthropologists Engage Philosophy - Pgs. 288-314Mariana OliveiraОценок пока нет

- Reidar Andreas Due DeleuzeДокумент192 страницыReidar Andreas Due Deleuzeliebest0dОценок пока нет

- ExcerptA KOSMOS 2003 PDFДокумент133 страницыExcerptA KOSMOS 2003 PDFbartsch6Оценок пока нет

- Deleuze and TimeДокумент233 страницыDeleuze and TimeRyan SullivanОценок пока нет

- The Aesthetics Symptoms of Architectural Form The Case of Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art by Richard Meier PDFДокумент18 страницThe Aesthetics Symptoms of Architectural Form The Case of Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art by Richard Meier PDFArchana M RajanОценок пока нет

- Michael Sukale (Auth.) - Comparative Studies in Phenomenology-Springer Netherlands (1977)Документ161 страницаMichael Sukale (Auth.) - Comparative Studies in Phenomenology-Springer Netherlands (1977)Juan PabloОценок пока нет

- Deleuze - From Sacher-Masoch To MasochismДокумент11 страницDeleuze - From Sacher-Masoch To MasochismAudrey HernandezОценок пока нет

- ART - Deleuze and Cadiot On Robinson Crusoe and CapitalismДокумент15 страницART - Deleuze and Cadiot On Robinson Crusoe and CapitalismMatiasBarrios86Оценок пока нет

- Cederberg - LevinasДокумент259 страницCederberg - Levinasredcloud111100% (1)

- Eric Alliez-What Is Contemporary French Philosophy TodayДокумент18 страницEric Alliez-What Is Contemporary French Philosophy TodayClifford DuffyОценок пока нет

- Rebecca Comay - Benjamin's EndgameДокумент21 страницаRebecca Comay - Benjamin's EndgamehuobristОценок пока нет

- Daniel Eggers - The Language of Desire - Expressivism and The Psychology of Moral Judgement-De Gruyter (2021)Документ262 страницыDaniel Eggers - The Language of Desire - Expressivism and The Psychology of Moral Judgement-De Gruyter (2021)ignoramus83Оценок пока нет

- Steinel Heat Gun User ManualДокумент18 страницSteinel Heat Gun User ManualutilscОценок пока нет

- Guide IbmДокумент19 страницGuide IbmmirzakadbtОценок пока нет

- Interchangeable Lenses For The ExaktaДокумент10 страницInterchangeable Lenses For The ExaktautilscОценок пока нет

- MT-501 Instalation ManualДокумент5 страницMT-501 Instalation ManualmymamymОценок пока нет

- Specifications-Cassete Feeding Unit Y1 Y2 SMДокумент1 страницаSpecifications-Cassete Feeding Unit Y1 Y2 SMutilscОценок пока нет

- Send FaxДокумент528 страницSend FaxutilscОценок пока нет

- Specifications DADF N1 PID DraftДокумент1 страницаSpecifications DADF N1 PID DraftutilscОценок пока нет

- Puncher q1 GTC GCDДокумент10 страницPuncher q1 GTC GCDutilscОценок пока нет

- Portable Manual: Finisher, Sorter, Deliverytray Puncher-Q1Документ48 страницPortable Manual: Finisher, Sorter, Deliverytray Puncher-Q1utilscОценок пока нет

- Network Guide En-GbДокумент244 страницыNetwork Guide En-GbutilscОценок пока нет

- Saddle Finisher q2 q4 SMДокумент262 страницыSaddle Finisher q2 q4 SMutilscОценок пока нет

- Saddle Finisher q2 q4 IpДокумент48 страницSaddle Finisher q2 q4 IputilscОценок пока нет

- Remote Ui Guide En-GbДокумент172 страницыRemote Ui Guide En-GbutilscОценок пока нет

- Installation Procedure: Finisher, Sorter, Deliverytray Puncher-Q1Документ20 страницInstallation Procedure: Finisher, Sorter, Deliverytray Puncher-Q1utilscОценок пока нет

- Service Manual: Finisher, Sorter, Deliverytray Puncher-Q1Документ64 страницыService Manual: Finisher, Sorter, Deliverytray Puncher-Q1utilscОценок пока нет

- Puncher q1 GTC GCDДокумент10 страницPuncher q1 GTC GCDutilscОценок пока нет

- Circuit Diagram: Finisher, Sorter, Deliverytray 3 Way Unit-A1/A2Документ12 страницCircuit Diagram: Finisher, Sorter, Deliverytray 3 Way Unit-A1/A2Catalin PatileaОценок пока нет

- Saddle Finisher q2 q4 CDДокумент46 страницSaddle Finisher q2 q4 CDutilscОценок пока нет

- Paper Deck q1 GTC GCDДокумент12 страницPaper Deck q1 GTC GCDutilscОценок пока нет

- Paper Deck q1 GTC GCDДокумент12 страницPaper Deck q1 GTC GCDutilscОценок пока нет

- Installation Procedure: Finisher, Sorter, Deliverytray Puncher-Q1Документ20 страницInstallation Procedure: Finisher, Sorter, Deliverytray Puncher-Q1utilscОценок пока нет

- Paper Deck q1 PCДокумент36 страницPaper Deck q1 PCutilscОценок пока нет

- Paper Deck q1 SMДокумент106 страницPaper Deck q1 SMutilscОценок пока нет

- SY103A eДокумент16 страницSY103A eutilscОценок пока нет

- Tda4852 CNV 2Документ16 страницTda4852 CNV 2utilscОценок пока нет

- Multi PDL Printer Kit-e1-SmДокумент42 страницыMulti PDL Printer Kit-e1-SmutilscОценок пока нет

- Ir2270 2870 3570 4570-cdДокумент22 страницыIr2270 2870 3570 4570-cdutilscОценок пока нет

- Multi PDL Printer Kit-e1-PcДокумент16 страницMulti PDL Printer Kit-e1-PcutilscОценок пока нет

- Multi PDL Printer Kit-e1-IpДокумент16 страницMulti PDL Printer Kit-e1-IputilscОценок пока нет

- Tda 4858Документ44 страницыTda 4858utilscОценок пока нет

- Film Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile AnthimanthaaraiДокумент8 страницFilm Career: 16 Vayathinile Muthal Mariyathai Vedham Pudhithu Karuththamma Kizhakku Cheemayile Anthimanthaaraidasdaa8291Оценок пока нет

- Weebly MoviesДокумент32 страницыWeebly Moviesapi-264662253Оценок пока нет

- Passive VoiceДокумент18 страницPassive VoiceVel CaОценок пока нет

- List of Raja MoivesДокумент79 страницList of Raja MoivesSivakumaar NagarajanОценок пока нет

- Amber Krieg ResumeДокумент1 страницаAmber Krieg Resumeapi-376941376Оценок пока нет

- Student Database 2021 (BIHERДокумент116 страницStudent Database 2021 (BIHER242503 ktr.et.eee.16Оценок пока нет

- 3.7.1 Collaborative ActivitiesДокумент252 страницы3.7.1 Collaborative Activitiesbharat kashyapОценок пока нет

- GalgotiasДокумент154 страницыGalgotiasSACHIN SINGHОценок пока нет

- Teacher's Notes: About The AuthorДокумент3 страницыTeacher's Notes: About The AuthorEl CiganitoОценок пока нет

- Sanskrit (2023-2024)Документ7 страницSanskrit (2023-2024)Cricket Hot SamacharОценок пока нет

- Halloween Song Thriller Michael Jackson Activities With Music Songs Nursery Rhymes CLT Com 60085Документ3 страницыHalloween Song Thriller Michael Jackson Activities With Music Songs Nursery Rhymes CLT Com 60085Света СливаОценок пока нет

- Mika Song ListДокумент3 страницыMika Song ListparthivjethiОценок пока нет

- Nov-2017 Ntse Marks List: DharawadaДокумент65 страницNov-2017 Ntse Marks List: Dharawadasuresh_tОценок пока нет

- Kund Schoolarship Test For IVДокумент2 страницыKund Schoolarship Test For IVEr. Shashikant GargОценок пока нет

- 2010 11 First Level ImoДокумент18 страниц2010 11 First Level ImoPhool ChandОценок пока нет

- Class ChartsДокумент8 страницClass ChartsAminath Thifla [1942]Оценок пока нет

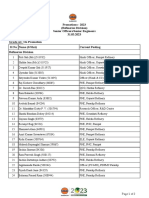

- Panel ListДокумент8 страницPanel ListPunna NithishОценок пока нет

- New Guntur PDFДокумент2 страницыNew Guntur PDFMeet SeshuОценок пока нет

- Bruce Lee: Listening and ReadingДокумент2 страницыBruce Lee: Listening and ReadingJessy RodriguezОценок пока нет

- Mahalakshmi Prashna Shastra Telugu by Ram Krishna - Telugu Book HouseДокумент66 страницMahalakshmi Prashna Shastra Telugu by Ram Krishna - Telugu Book HouselakshmankannaОценок пока нет

- Mech PDFДокумент7 страницMech PDFLingutla Sairam KumarОценок пока нет

- Ssociation For Omputing Achinery: Etention Ist For The YearДокумент3 страницыSsociation For Omputing Achinery: Etention Ist For The Yearprashant kumarОценок пока нет

- Industrial TourДокумент1 страницаIndustrial TourNishant KumarОценок пока нет

- The Order of National Artist: Contemporary Philippine Arts From The RegionsДокумент37 страницThe Order of National Artist: Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Regionsshey mahilumОценок пока нет

- An Unforgettable Experience in My Life Was A Magnitude 6.9 EarthquakeДокумент7 страницAn Unforgettable Experience in My Life Was A Magnitude 6.9 EarthquakeFachreza AkbarОценок пока нет

- M.S. Dhoni The Untold Story 2016 Hindi Movie BluRay 500mb 480p 1.6GB 720p 5GB 14GB 18GB 1080pДокумент1 страницаM.S. Dhoni The Untold Story 2016 Hindi Movie BluRay 500mb 480p 1.6GB 720p 5GB 14GB 18GB 1080pdhananjayverma726Оценок пока нет

- Movie ClozeДокумент2 страницыMovie ClozeFarkas-Szövő NikolettОценок пока нет

- Blade Runner RevДокумент22 страницыBlade Runner RevEdson F. OkudaОценок пока нет

- REF Promotions Grade A To A1Документ2 страницыREF Promotions Grade A To A1Salman KhanОценок пока нет

- Naveen KumarДокумент5 страницNaveen Kumarcryptocasper223Оценок пока нет