Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Bombay Group of Poets

Загружено:

Vipasha BhardwajИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Bombay Group of Poets

Загружено:

Vipasha BhardwajАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

1

2

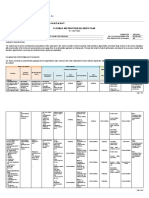

INTRODUCTION

This dissertation offers a prolific insight into the writings of Bombay group of poets in Indian

Writing in English. The poets taken into account for analysis are Dilip Chitre,Arun Kolatkar

and Eunice de Souza. It is a novice attempt to bring out a completely new dimension of the

urban landscape poetry which brings out the seriousness from the quotidian city life along with

the world of fear, anxiety and despair that it offers. Unlike the high-seriousness of pre-

Independence poets, these Bombay poets are transparently true to life, they are not Idealists

rather eccentric in their approach to life. They have not lived abroad but live or have lived in

the vicious atmosphere of Bombay struggling to come up with a striking individuality of its

own, an angularity in its gestures with a tone of defiance (or at least non-conformity).

I shall be looking at close quarters towards their features as Bilingual Experimentalist,

the post-modern aspects in their work, the influence of Marathi poets which has shaped their

poetry and the confessional nature of their poems.

And at the moment of contact, they do not know if the hand that is reaching for theirs belongs to a

Hindu or Muslim or Christian or Brahmin or untouchable or whether you were born in this city or

arrived only this morning or whether you live in Malabar Hill or New York or Jogeshwari; whether

youre from Bombay or Mumbai or New York. All they know is that youre trying to get to the city

of gold, and thats enough. Come on board, they say. Well adjust.

-Suketu Mehta ( Maximum City)

In Rushdies fifth novel, The Moors Last Sigh, he would expand on this idea: Bombay

was central, had been so from the moment of its creation: the bastard child of a Portuguese

English wedding, and yet the most Indian of Indian citiesall rivers flowed into its human sea.

It was an ocean of stories; we were all its narrators and everybody talked at once (Rushdie

1997:350). Situated centrally on the western Malabar coast of India, Bombay was once an

island fishing village included in the dowry of the Portuguese princess, Catherine of Braganza,

when she married Charles II. Cities often live in our imaginations, their physical and social

architecture exercising real power by conjuring up fictions and myths. Bombay, it has been

3

said, is not a city but a state of mind; a state of a young mans mind, exciting and excitable,

exuberant and effervescent, dynamic and dramatic.

There is no doubt that this port metropolis-with its self-conscious commingling of

cultures and commodities, fabulous wealth and unimaginable poverty, and teeming tensions

and transformations has provided writers with compelling literary material, particularly in what

has come to be known as the Bombay poets in English. Bollywood too has long projected

Bombay as a Janus-faced space of desire and disappointment, emancipation and exploitation.

In its polarities and contradictions, this vibrant city embodies both the promise and the betrayals

of Independence, enables encounters across classes, castes, communities, and genders in

hitherto unprecedented ways that gestured towards, without necessarily realizing, egalitarian

possibilities.

The political scientist Sudipta Kaviraj in his book Politics in India has remarked that

Democracy in the decades after independence had a clearly marked space of residence.The

city, Bombay and Calcutta, par excellence, had that mysterious quality, liberating and

contaminating at the same time . But unlike Delhi, Bombay isnt a city rich with history. Unlike

Calcutta whose cultural icons include Rabindranath Tagore and Satyajit Ray, Bombay, devoid

of any regional character, could function as the urban archetype in early Hindi cinema. Bombay

makes news when terrorists attack the city or when Mukesh Ambani, the wealthiest man in

India, spends a billion dollars to erect a skyscraper for himself, or when the symbol of its

squalor, the slum, provides the backdrop for an Academy Award-winning film. But

nevertheless, it is in the realm of cosmopolitanism that Bombay has such symbolic importance

to India.

Bombay is where barriers crumble and this provided the terrorists with a good reason

on a November night in 2008 to siege the city for more than two days killing hundreds of people

in a place which represents what India can be-a place where people from all parts of the country,

speaking different languages, worshiping different gods, come together for the common

purpose of leading a better life. Two years later, the city continues to live on edge (Unlike Delhi

and Ahmedabad, to name two cities which have erupted into riots after experiencing targeted

violence, Bombay stayed calm. Mass retaliation is rare in trading cities). It is a city, Pico Iyer

relates, that is both beachhead for the modern and multi-cultured port, a haven of tolerance for

Hindus, Muslims, Parsis, Christians, Sikhs, Jains, and others bound in a money-minded mix.

Its kindred spirits, he suggests, are those other island staging-posts of people, capital and

4

modernity, Hong Kong and Manhattan. Bombay has become a self-conscious cocktail of

cultural heterogeneity:

On the one hand, the colonial authorities stamped the official public space with their representations

and encouraged the use and spread of the English language, Gothic and later other styles of

architecture, Western music and theatre. On the other, the native migrant communities developed

their own community cultures, their languages through their community associationsBy the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a distinct form of upper class cosmopolitan culture had

developed in Bombay as much as its opposite. (qtd.in Images of Transcendence and Survival by

Rohinton Mistry)

But what ultimately may tear the city apart some day is the threat within, the Shiv Sena.

In his novel, The Moors Last Sigh, the Bombay-born Salman Rushdie writes: Those who

hated India, those who sought to ruin it, would need to ruin Bombay. The people he had in

mind were the politicians whom Thackeray nurtured. The Shiv Sena has used thuggish force

to attack communities, businesses, and ideas that it abhors. The city is littered with examples

of businesses changing their names, altering their recruitment practices, and acquiescing to the

whimsical demands of the party, and its rival off-shoot, Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (the

Maharashtra Re-creation Army). Most recently, Thackerays grandson went to meet the vice-

chancellor of the citys premier university and remarked that he was annoyed that the university

had included the Bombay-born Canadian writer Rohinton Mistrys novel, Such A Long

Journey, as part of its literature syllabus, since it ridiculed his political party and Marathi

culture. The vice-chancellor immediately withdrew the book from the syllabus, to the horror

of many of the citys residents.

Imperial architecture, panoramas of skyscraper-studded skylines, crowded streets,

overflowing trains, advertising billboards, throbbing nightclubs, Bombay often evokes the

hallmark of swapaner nagari,a city of dreams. Rohinton Mistry,in his film(adopted from the

novel) Such A Long Journey(1998) has described Bombay as A golden nest with no place to

rest. Milan Luthrias recent Hindi film, Taxi 9 2 11: Nau Do Gyarah (2006, hereafter Taxi)

examining representations of post-colonial Bombay, traces the simultaneous possibilities and

problems of Bombays reputation as the quintessentially modern city of India, the countrys

commercial display window. The city is crammed to the core and as they say even the

footpath has no space here. Being both a city of debris and a city of spectacle, Ranjani

5

Mazumdar in her recent work on Bombay cinema demonstrates that Bombay claims the

fantasy of a lifestyle unblemished by the chaos and poverty that exist all around (ibid.,p.110).

Combining its regional and linguistic chauvinism with the broader projects of Hindu

nationalism, the Shiv Sena made significant political gains in the 1980s and

1990s, positioning Bombay at the center of a nation rescripted as a sacred, Hindu space, a

project culminating in and symbolized by the citys official name change to Mumbai(under

chauvinist pressure) in 1995. Bombay or Mumbai, the place has always enjoyed a unique place

in Hindi film lore and today in the genre of poetry too. But today, there has been a significant

change in the citys cinematic image. It is no longer conceived primarily as the cosmopolitan

urban space but imagined as a localized milieu inscribed with a regional flavor. The industrial

dynamics as well as the sociopolitical and economic events played a role in reimagining the

city. The city has been for centuries a focus for global trade around the Arabian Sea and beyond,

owing in large part to its endowment with one of the largest harbors in South Asia, and,

especially from the mid-nineteenth century, has long been attractive to a wide range of

migrants. The figure of the city as cosmopolitan is a constant feature in narratives of its recent

decline.

A particular kind of worldliness, cultural pluralism exists in Bombay. And perhaps this

might be the reason why Bombay inspires much literary faculty. Unsurprisingly, the Bombay

poem is preoccupied with the cosmopolitanism and the stories generated by migrants and

minority communities. Writers from minority communities within India like Salman Rushdie,

Rohinton Mistry(of Parsi background) Nissim Ezekiel(Jewish), Shama Futehally (from a

Muslim family)have found Bombay a familiar and productive, if not always congenial, space

to write about. Much of the romance about Bombay comes from the fact that authors have

found poetry and insight in its most charmless parts; chawls, crammed local trains, defiled

beaches, prostitutes, the monsoon rains et al. The absence of a picturesque landscape has never

dettered the readers curiosity to rejoice the artistic pieces. Even the dusty world of construction

and redevelopment has inspired bestsellers, like Last Man in Tower by Aravind Adiga. The

narratives do not attempt to erase the ugliness and despair of life in Bombay. Instead the fact

that Bombay thrives despite all its problems is what makes it both beautiful and inspiring to

our authors. And consequently, poetry and fairy dust are sprinkled over the citys most

maddening aspects, from water shortage to riots.

6

The sordid side of Bombay has also served as happy hunting ground for the citys

chroniclers. The countrys financial capital is plagued by a surfeit of socio-economic issues.

The sleazy underworld, murderous husbands, corrupt administrationstheres a lot that is

askew in our urban landscape but when written about by the likes of Suketu Mehta (Maximum

City), Gyan Prakash (Mumbai Fables), S. H. Zaidi (Black Friday, Mafia Queens of Mumbai) and

Sonia Faleiro (Beautiful Thing), these dark stories are much more than depressing news items.

They become crazy mirrors reflecting the reality of this city with symbolism and insight.

Without literature, both fiction and non-fiction, to show us the possibilities contained in

everyday life in this city, Bombay would feel a lot less magical.

Sometimes,Indian Poetry in English reminds us of the Johhny Walker jingle: "Main

Bumbai ka babu, nam mera anjana/ English sur mein gaoon main Hindusthani gana".The

Indianness in English words is a very distinct feature that differentiates and familiarizes the

Bombay poets. The role of this one city is immensely significant in churning out some of the

great authors, not just Ezekiel, Gieve Patel, Eunice de Souza,Dilip Chitre,Arun Kolatkar, Adil

Jussawalla, Salim Peeradina but also Parthasarathy and Arvind Mehrotra who studied here.

Kamala Das rose to fame when she was in Bombay (it wasn't Mumbai then).

Living in a single place, or at least they seem to be, these poets in a sense are

stubbornly local in their temperament. Professor Vinayak Krishna Gokak at the symposium

on Poetry India,1974 held in Madras explained that poems should be composed about the

life that goes on around us embodying the stuff of every day. It would be the height of audacity

to advise a poet what he should or should not write about.

Modernism has often been viewed, in turn, as a Euro-American product, trans-national

only insofar as many modernist artists and writers were expatriates or exiles in Europe and in

the United States. But it is time to clear a space, as Amit Chaudhri had put it, for alternative

trajectories and genealogies of modernism outside of these Western filiations, beyond the

canonical period of high modernism (1910-1930) and to explore how modernism was

reinvented through displacement. Somebody again said that one must write poetry that is easy

to understand. If it is to be difficult, it should be difficult in the manner of the modernists. But

our Bombay poets do not talk about fundamental brain-stuff, although they deliver expression,

persuasion or revelation extracted from the trivial things in life. Several questions darken our

7

mind when we chart out their unmapped territory; is it intuition? Is it the dreams of us that are

awake? Is it an expression of personality or an escape from it? What is it?

In the impersonal and almost callous society that is fast growing around us, we have

begun to experience loneliness in crowded cities. Sensitive people find it hard to live unless

they share their joys and sorrows and their ditties and dreams with like-minded people. As a

thirst-aiding center, the meeting of these Bombay poets provide great psychological relief to

desolate readers.

As we know modern Indian English-language poetry began to emerge at the end of

Second World War after the end of colonialism. The writers who came to be celebrated as the

pioneers of modernism wanted to liberate themselves from an overbearing literary culture,

breaking down from the Tagore Syndrome characterized by cultural nationalism, romantic

love, idealization of nature, metaphysics and mysticism and an ideal nation building. The poets

of the recent times with a different sensibility are trying to articulate the existential tensions,

anxieties and doubts of individuals sentenced to the solitude, ambiguity and anguish of the

post-industrial urban infernos. Dilip Chitre in his introduction to an Anthology of Marathi

Poetry,Volume I of contemporary Indian Poetry (1945-65) alludes to this experience as the

broken gestalt and shows with examples from Marathi poetry how the very cultures that broke

off violently from the tradition were the very cultures that had a deep-rooted sense of their

native ways of feeling because it was individuals in these cultures who experienced the deepest

trauma when the mechanized society enjoying the fruits of a mass civilization broke up their

sense of an organic inner life.

The modern poets were more open with its surprising attitudes towards such topics as

guilt, sexuality, ambition, memories of past rebellions, conflicts, shames, childhood and love

affairs and an assertion of an articulate but fractured self that they became part of the

confessional mode of poetry that started in America during the early 50s and 60s.Although

they were exposed in a big way to the experiments in contemporary Western poetry, as they

have either lived and studied abroad, brought up in urban centers, yet they refused to imitate

since they were well aware of the indigenous traditions that were rich in situations, characters,

symbols ,motifs and archetypes that could well serve as a source of metaphors for the conflicts

of modern life.

8

The Bombay poets as a group tend to be marginal to traditional Hindu society not only

by being alienated by their English-language education but also, more significantly, by coming

from such communities as the Parsis, Jews and Christians, or by being rebels from Hinduism

and Islam, or by living abroad. There is no other authentic mentality for these poets except that

of the modern world and its concerns, which they may express or criticize but of which they

are a part, as are an increasing number of Indians.

The twentieth century suburb has often been the object of scorn and derision (

The Country and The City,12). The Bombay poets often include the whole urban landscape to

reveal the sin and squalid of the metropolis. The moral failings of city-dwellers are creatively

wrapped in satirical verses which scornfully brings out the disintegrity. The urban theory of

Heterotopia, coined by social theorist and literary critic Michel Foucalt in the 1960s, is

reflected in the works of these Bombay poets. A world off-center that possesses multiple,

fragmented and incompatible meanings, the contemporary transformation of the city displays

a profound redrawing of the contours of public and private space, bringing to the fore an equally

treacherous and fertile ground of conditions that are not merely hybrid, but rather defy an easy

description in these terms( Foucalt 6).The privatization of public spaces creates a camp-like

situation, a space where law is suspended as a result of which the society is disintegrated. The

space in the city is annihilated and the citizen reduced to bare life. Today, more and more

people are exposed to the conditions of bare life: the homeless, illegal immigrants, the

inhabitants of slums. The idea of shared or collective spaces can be traced in the Bombay poems

when the poet talks about the journey by a commuter in the local trains. They show how these

city-dwellers have embraced the brutality of the grotesque urbanism.

The haunting obsession of the nineteenth century: themes of development and

stagnation, themes of crisis and cycle, themes of the accumulation of the past, the big surplus

of the dead and the menacing cooling of the world, have been inculcated in the urban poems.

Bombay is a city in the midst of extensive social and spatial (re)construction. The border, the

boundary everything dissolves in this globally and increasingly interconnected metropolis.

After the Second World War in India that coincided with a feverish activity in translation

and unleashed a tremendous variety of cross-influences almost all of a sudden, writes the

bilingual Marathi-English poet Dilip Chitre, the 1950s and 1960s represented a fantastic

conglomeration of clashing realities (Anthology 5) that was particularly palpable in Bombay:

city of gold by the early 20

th

century and magnetizing city for migrants, gateway for India and

window on the West, dream city of cosmopolitan desire(Prakash 75) and unlimited

9

possibilities, mosaic of modern culture and communal mix. With the arrival of successive

waves of migrants, ethnic, caste, religious, and linguistic diversity has become a constitutive

aspect of the city. As early as 1832,visitors to the city remarked on its heterogeneity: In twenty

minutes walk through the bazaar of Bombay, my ear has been struck by the sounds of every

language that I have heard in any part of the worldin a tone which implied that the speakers

were quite at home (B.Hall cited in Kosambi 1986: 38). Bombay is certainly the most

composite, multilingual and multiconfessional of Indian cities, where Portuguese, British,

Jews, Parsis, Iraqis, Russians, Chinese, Persians but also Indians and refugees from the whole

sub-continent congregated and left their mark. Most Bombay poets are not originally from

the city and have precisely migrated there, uprooted from other states, small cities or rural

backgrounds (Dilip Chitre came from Gujarat, Arun Kolatkar from Kolhapur, a small town in

South Maharashtra, etc. The Progressive Artists Group which is the most influential school of

modern art in India and was formed in 1947 in Bombay is precisely a product of such

migrations and cosmopolitanism.

When many modern Indian poets started writing in the 1950s and 1960s, it was

the time for Beat poetry, sound poetry, visual poetry, concrete poetry, jazz poetry and

continuing surrealism; a time of openness to everything else that was happening in the world

and of feverish experimentation with all kinds of forms and mediums. Bombay poets engaged

with these new paradigms and with the internationalism of the avant-garde. They had all been

exposed to the modernist galaxy and often consciously placed themselves in this lineage. An

unpublished fragment by Arun Kolatkar reads as follows: I was born the year Hart Crane

killed himself / Nine years after Ulysses was burnt / three years after Auden published his first

collection / one year after Makovsky killed himself / I had my first tooth when / Dylan Thomas

published his first collection (Kolatkar Papers).

Bombay poets hence developed strong affinities with European modernism and the

counter-culture of the 1960s. Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, the Dadaists and Surrealists, William

Carlos and the contemporary Beats in the United States, but also anti-establishment little

magazines like Partisan Review ,Paris Review or Evergreen Review , which were read,

circulated and discussed, are the defining influences of a lot of modern Indian poems.

Over half the citys population of millions live in the gigantic slums of Bombay;

the richest urban center in India is also home to Dharavi, Asias largest slum. Overflowing

sewers, broken water-pipes, pot-holed pavements, rodent invasions, bribe-extracting public

10

servants, uncollected hills of garbage, open manholes, shattered streetlights are sewn together

in a patchwork quilt of lives and stories connected by chance encounters and shared experiences

in Bombay (Mistry 1991: 279)

This period which is sometimes described as a kind of Indian renaissance signaled

years of collective endeavors. The poets often formed small alternative presses and workshops,

countless journals and underground anti-establishment little magazines, like the cyclostyled

Shabda (literally word or speech) in Marathi started by Dilip Chitre, Arun Kolatkar and

others in 1954 or Damn You: A Magazine of the Arts , started in 1965 by the poet Arvind

Krishna Mehrotra and modeled on the American publication Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts

, which rapidly became a temporary outpost of the American and European avant-garde

(King,23).

This renaissance affected all artistic domains. We thus find in the 1950s and 1960s in

Bombay the same creative symbiosis between the visual arts and literature that is a trademark

of Euro-American modernism. Amit Chaudhuri talks about the metropolitan flirtations

between artistic subcultures and the way Bombay poet-critics like Nissim Ezekiel, Arvind

Krishna Mehrotra, Adil Jussawalla and Gieve Patel poached and encroached upon the territory

of painters ( Clearing a Space, 224). Many of the journals and little magazines published at

the time are meticulously crafted and designed works of art, edited together by painters and

poets (Vrischtik edited by the painters Gulam Sheikh and Bhupen Khakar,Shabda edited by the

painter Bandu Waze, by Dilip Chitre, Arun Kolatkar and others) who not only worked together

but sometimes, like Gieve Patel or Kolatkar who trained as a visual artist at the J. J. School of

Art, were both painters and poets. Kolatkar thus designed the covers for a lot of little magazines

and collections:Shabda in the 1950s,Dionysus in the 1960s, all the covers of the small

publishing cooperative Clearing House later in the 1970s, etc. Poets, writers, painters, theater

and film directors gathered around the J. J. School of Art which became the nucleus for all art

activity (Dalmia 4) on Indias West coast but also around the Jehangir Art Gallery in the South

Bombay district of Kala Ghoda, where the Progressive Artists Group was formed, notably in

the Artists Aid Fund Center which Dilip Chitre evokes as follows: the place reminded me

more of an orphanage than an art gallery (Remembering Arun Kolatkar). They often lodged

together in small congested spaces and lived in self-conscious literary bohemianism(

Engblom 391)

11

Throughout all the different representation of Bombay by different people, one thing is

very common. It is the tone of confession and sordidness. In the century that rolled past us

quite a handful of Indian poets who chose to write in English had their rendezvous with future

in this city uncontained by movie screen and epigramwhere it is perfectly historical/to be

looking out/on a sooty handkerchief of ocean/searching for God (lines 14-42) as poet

Arundhati Subramanion would qualify it in the poem Where I live. Despite its paradoxes,

Bombay is a city of dreams where nightmares lurk everywhere. It is luxurious and gritty; full

of promise, it is sure to betray. One may wonder if the almost proverbial Mumbai Muse has

been a coincidental myth or if the alchemy of this city is indeed at work.

12

Chapter One: Arun Kolatkar

My name is Arun Kolatkar

I had a little matchbox

I lost it

then I found it

I kept it

in my right hand pocket

It is still there

(Poems in English 1953-1967)

It is evident from the above mentioned lines that the Indian English poet taken for analysis

takes his imagination to a non-realistic poetic mode different from a superior kind of logical

and emotional communication; such poetry may be concerned with the irrational, with chance,

or with structures of art. Because experimental poetry foregrounds technique, new concepts

,or explores uncommon experience it usually neglects the common world and environment or

treats it in strange, unconventional ways (King, 23 ). Few artists remain pure experimentalists

for long; the fascination with techniques, fantasies, games and the subconscious is the product

of a period of an artists life which will eventually give way or be assimilated to a sense of

reality-if only in a preoccupation with ones difference or alienation from communal or cultural

perceptions of reality.

Kolatkar also led another life, and took great care to keep the two lives separate. Arun

Kolatkar was a visual artist by profession and he quickly established himself in this league

which, in 1989, inducted him into the hall of fame for lifetime achievement. His poet friends

13

were scarcely aware of the advertising legend in their midst, for he never spoke to them about

his prize-winning ad campaigns or the agencies he did them for. His first poems started

appearing in English and Marathi magazines in the early 1950s and he continued to write in

both languages for the next fifty years, creating two independent and equally significant bodies

of work. Occasionally he made jottings in which he wondered about the strange bilingual

creature he was:

I have a pen in my possession

which writes in 2 languages

and draws in one

My pencil is sharpened at both ends

I use one end to write in Marathi

the other in English

what I write with one end

comes out as English

what I write with the other

comes out as Marathi. ( from Translations)

With the paperback revolution in the publishing industry after the Second World

War in India that coincided with a feverish activity in translation and unleashed a tremendous

variety of cross influences almost all of a sudden the 1950s and 1960s represented a fantastic

conglomeration of clashing realities (Chitre, Anthology 5) that was particularly palpable in

Bombay: city of gold by the early 20

th

century and magnetizing city for migrants, gateway for

India and window on the West, dream city of cosmopolitan desire (Prakash 75) and unlimited

possibilities, mosaic of modern culture and communal mix.

14

By the later 60s English-language poetry in India had a handful of new classic

volumes, not necessarily published by Writers Workshop, and established significant writers

but it was gaining recognition from those with an interest in poetry and culture both in India

and abroad. By now the modern Indian English poets formed a sufficiently large group to have

different tastes, aesthetics, standards and styles. This partly reflected the rapidity with which

the poetry was evolving towards international standards as well as different notions of the art.

Their international standards could be gauged from The Progressive Artists Group

which is the most influential school of modern art in India and was formed in 1947 in Bombay

is precisely a product of migrations and cosmopolitanism. Not only were Jewish European

migrs largely involved in the development of the Progressive Artists Group (like the German

cartoonist Rudi Von Leyden or the Austrian painter Walter Langhammer who became the first

arts director of the Times of India), but the founding fathers of this group all come from

different regional, religious and linguistic backgrounds: F. N. Souza from Goa, K. H. Ara from

Hyderabad, M. F. Husain from Pandharpur in Maharashtra, S. H. Raza from Madhya Pradesh,

Sadanand Bakre from Baroda, etc.

All his life Kolatkar had an inexplicable dread of publishers contracts, refusing to sign

them. This made his work difficult to come by, even in India. Jejuri was first published by a

small co-operative, Clearing House, of which he was a part, and thereafter it was kept in print

by his old friend.,Ashok Shahane, who set up Pras Prakashan with the sole purpose of

publishing Kolatkars first Marathi collection Arun Kolatkarchya Kavita . Jejuri, a sequence

of thirty-one poems based on a visit to a temple town of the same near Pune,appeared in 1976

to instant acclaim,winning the Commonwealth Poetry Prize and establishing his international

reputation. But Jejuri has been a controversial poem for a variety of reasons. This poem is a

case in point when we deal with all the important questions of the expression of Indian

sensibility through an unusual perspective. Jejuri,thirty miles from Pune,has one of the most

prominent temples in Western Maharashtra and it is dedicated to the god known as Mallari

Martand.This Hindu deity, also known as Khandoba, is worshipped by people of all castes and

creeds. Divided into many small poems, Jejuri stands as a composite whole.

Only incidentally, though, is Jejuri about a temple town or matters of faith. The first

question that comes to our mind is: why does the narrator go to Jejuri? Is religious quest the

chief motive behind the narrators visit to Jejuri? At its heart,and at the heart of all Kolatkars

work, lies a moral vision, whose basis is the things of this world, precisely, rapturously

15

observed. So, a common doorstep is revealed to be a pillar on its side, Yes./ Thats what it is

; the eight-arm goddess, once you begin to count, has eighteen arms; and the rundown Maruti

temple, where nobody comes to worship but is home to a mongrel bitch and her puppies, is, for

that reason, nothing less than the house of god. The matter of fact tone, bemused, seemingly

offhand, is easy to get wrong, and Kolatkars Marathi critics got it badly wrong, finding it to

be cold, flippant, at best skeptical. They were forgetting, of course, that the clarity of Kolatkars

observations would not be possible without abundant sympathy for the person or animal (or

even inanimate object) being observed; forgetting too,that without abundant sympathy for

what was being observed, the poems would not be the acts of attention they are(Mehrotra,

Arvind Krishna.Arun Kolatkar,Collected Poems in English).

The thirty-six sections of Jejuri consist,like The Boatride,of varied and difficult to

analyze perceptions and attitudes of someone on a journey. Here it is an apparently skeptical

tourist who arrives in the ancient place of pilgrimage; at the end he is waiting with irritation

for a train so he can depart. The opening poem establishes themes of perception and alienation:

Your own divided face in a pair of glasses

on an old mans nose

is all the countryside you get to see. (lines 10-12)

At the end of the bumpy ride

with your own face on either side

when you get off the bus

you dont step inside the old mans head . (lines 22-25)

( The Bus, Jejuri)

Talking about alienation, Dileep Jhaveri in his essay Tradition-Independence-Metropolis-

Modernity-Freedom:Elusion and Illusion has rightly said, Truly in Bharat now we the poets

carry the mark of both disinherited children and strangers to ourselves and all.

16

But one aspect of Jejuri which is very significant is, Kolatkars divine perspective which he

draws from everything that is before his naked eyes. He is struck by the faith of the pilgrims

who come to worship at Jejuris shrines as by the shrines themselves, one of which happens to

be not shrine at all (but nevertheless his divinity has a flip side to it):

The door was open

Manohar thought

It was one more temple.

He looked inside.

Wondering

which god he was going to find.

He quickly turned away

when a wide eyed calf

looked back at him.

It isnt another temple,

its just a cowshed.

(Manohar, Jejuri)

The first question that comes to our mind is: why does the narrator go to Jejuri? Is

religious quest the chief motive behind the narrators visit to Jejuri? Jejuri is conventionally

regarded as a quest poem. It is,undoubtedly,a presentation of modern urban skepticism

impinging upon the ancient religious tradition. The dilapidation of this tradition is shown by

using irony, differently and brilliantly. According to M.K.Naik, the thematic complex is much

larger and the poem is a conscious attempt to present in sharp contrast three major value

17

systems-viz. those of ancient religious tradition, modern Industrial civilization and-a value

system older than both these-the Life principle in Nature and its ways. The poem is full of

pictures of aridity and ugliness, decay and neglect, fossilization and perversion. The ironic

description in these lines makes it clear:

the little town

with its sixty three priests inside their sixty three houses

huddled at the foot of the hill

with its three hundred pillars five hundred steps and eighteen arches

(lines 1-4)

(Between Jejuri and the Railway

Station.,Jejuri)

Also The Priest skeptically views a priest calculating what he will get from the

tourists offerings. Kolatkar has shown the priests worldliness and greed. The tour bus stands

purring softly in front of the priest.

A catgrin on its face

and a live, ready to eat pilgrim

held between its teeth (lines 30-33)

(The Priest, Jejuri)

The above mentioned lines also inform us that in Kolatkars poems, inanimate objects

often form a parallel world constantly endeavoring to defeat human beings.

The discrepancy between appearance and possible reality, between the

commercialization of the ruined places of worship and what in the speakers view is divine, is

shown in the next poem, Heart of Ruin, about a mongrel bitch and her puppies in a ruined

temple: No more a place of worship this place/ is nothing less than the house of god. The

difficulty in knowing what has been seen and the way reality can be re-visualized, re-perceived,

is shown by The Doorstep:

18

Thats no doorstep.

Its a pillar on its side.

Yes.

Thats what it is.

(The Doorstep,Jejuri)

Arun Kolatkar has ridiculed the blind faith of the pilgrims by saying that almost every

stone at Jejuri is sacred because it is an image of some god. Kolatkar replied when asked by an

interviewer (The Indian Literary Review,vol.I,no.4,August 1978,pp.6-10) whether he believed

in God- I leave the question alone.I dont think I have to take a position about God one way

or the other. Thus, there is no limit to the number of stone images of the gods whom the

pilgrims can worship .This is an ironical way of denying the being of any god and doubting the

legitimacy of any conviction in the stories which have accumulated around the name of

Khandoba. It can be said that modernism offered a shimmering vision of escape from

everything conservative, traditional and limited:

Sweet as grapes

are the stone of jejuri

said chaitanya

he popped a stone

in his mouth

and spat out gods

(Chaitanya. Jejuri)

It is very difficult to decide at Jejuri what is a god and what is a stone because any stone a

pilgrim picks up may attest to be the image of a god.

19

In the poem Makarand,the protagonist prefers to smoke outside rather than entering inside

the temple premises, shirtless. He objects to the very act of worshipping a stone or bronze

image that supposedly represents a deity.

In the poem Between Jejuri and the Railway Station, Kolatkars proficiency as a visual artist

comes to the fore with remarkable sophistication. In contrast to the petrification of the spirit in

the temple town, the fowls do an astonishing dance. The typography which represents the

dancing puts the themes of dynamism and perception into visual terms. The dancing chickens,

like the butterfly and mongrel puppies, stand for a divine quality which the legends of Jejuri

represent but which has been lost among its ruins and commercialization.

The modern poets were born during a decade before or after the Independence. They were

neither a part of the freedom struggle nor its witnesses and were presented with this freedom

on a platter like toy building blocks ,mechano sets, jigsaw puzzles, crayons or coloring sketch

books. They were free to articulate that freedom even if they did not comprehend it. The grass

root relationship with tradition is a short statement in their poetry

Jejuri has evoked mixed reactions. It has been called a poem of extraordinary qualities

(Acharya. Jejuri. Kavi,28) ; a poem that depicts symbolically the tortured psyche of modern

man ( Shantinath Desai. Arun Kolatkaranchi Jejuri: Devanchi vasti. Pratishthan, 37) and

an X-ray vision of the enveloping dilapidation and the poets reaction to it

(E.V.Ramakrishnan, Jejuri, the Search for Place, Journal of Indian Writing in English, p.19).

Bruce King in his Modern Indian Poetry in English commented, Jejuri is, I think, less a

poem of skepticism and a poem about a modern wastelands loss of faith than a poem which

contrasts deadness of perception with the ability to see the divine in the natural vitality of life.

In Kolatkars hands the tradition of saints poetry takes the form.of an ironic parody of a

pilgrimage which while mocking institutionalized religion affirms the free imagination and the

dynamism of life. As a modern poet, Kolatkar shares some of his freedom of spirit at the same

time articulates it.

Acclaimed as a Bombay poet,Arun Kolatkar reflects on his childhood events on the streets

of Bombay, in the poem Crying Mangoes in Colaba originally published in Marathi as

Kolabyachi pheri, when he used to accompany his father to Colaba on ravivars (Sunday) to

20

sell mangoes. Upon translation, the poem still retains its native Marathi flavor; Mangoes are

called hapoos and paayriii in Marathi and they have secured their place in the English

translation as well. The poem is deeply autobiographical. In the collection Making love to a

poem Kolatkar talks about his views upon translating a poem. Written in a simplistic manner,

Kolatkar asserts:

Translating a poem is like making love

having an affair

Making love to a poem

with the body of another language

you may meet a poem you like

getting to know the poem carnally

getting carnal knowledge (I,lines1-7)

Arun Kolatkar says that he cannot translate a poem until he has got the feeling that he has

possessed it. Then he goes on to cite examples of Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Mahatma Gandhi.

For him, some of the finest poetry in India, or indeed the world, has come from a sense of

alienation. His bilingualism is perhaps what makes him a distinct figure in the realm of

contemporary poetry:

Ive written in 2 languages from the start

I was writing what I hoped were poems

switching from the one to the other freely

without asking myself whether I had

the right to write in either

and riding rough shod over both

or the qualifications

qualifications I knew I had none(II, lines 1-8)

21

First published in Debonair the Taxi Song is highly colloquial in tone perhaps because

Kolatkar was highly influenced by American popular music. He said that gangster films,

cartoon strips and blues had shaped his sense of the English language and he felt closer to the

American idiom, particularly Black American speech, than to British English. He mentioned

Bessie Smith,Big Bill Broonzy and Muddy Waters- Their names are like poems, he said- and

quoted the harmonica player Blind Sonny Terrys remark, A harmonica player must know

how to do a good tox chase. One reason why the poet liked blues was that the musicians were

often untrained and improvised as they went along. He dwelt on the musics social history;

how during the Depression blues performers moved from place to place, playing in honky-

tonks, sometimes under the protection of mobsters. He remembered the Elton John song Dont

shoot me, Im the only piano player. In the concerned poem, Kolatkar represents a typical

Metropolitan life devoid of any humane bond between yesteryears bosom friends. The urban

energy has turned its denizens into automated beings and friends have turned into sceptic

strangers reluctant to help each other at the time of crisis. Using the first person narration,

Kolatkar in a dialogic manner asks :

from colaba to dadar

you think i aint gonna pay you

after all that trouble

well thats where you are wrong

cause Im gonna pay you double.(lines 10-14)

In his Kala Ghoda poems which appeared after decades of winning the Commonwealth Prize

for poetry for Jejuri,Kolatkar sharpens and renews the experiences of our very familiar world.

Most importantly,he lends you an alternative eye to see into the life of apparently irrelevant

things. Kala Ghoda is the crescent that stretches from the Regal Circle to the University of

Mumbai. In this collection, particularly, Kolatkar explicitly uses the Bombay landscape; from

the iconic Max Mueller Bhawan to a petty roadside stall,every nook and corner of the city

forms Kolatkars imagination. Enchanted by the ordinary, Kolatkar made the ordinary

22

enchanting. Which is why,however familiar one may be with his work, its always as though

one is encountering it for the first time.

With a concentration of centers like the National Gallery of Modern Art,the Prince of Wales

Museum,the Jehangir Art Gallery,the Bombay Natural History Society,the David Sassoon

Library and the University,this place is a hub of cultural activity. Over the years Kala Ghoda

has come to be instinctively identified with its festival, an interactive cultural mlange that

spreads from November to January every year which brings works in the field of

music,dance,theatre,film,and art from across the country for Mumbaikars.

To express the appearance of trifling that is made to appear having some effect on the

poem,a few examples are taken from Kolatkars work.For e.g the Lund & Blockley shop at

Colaba,the neighbourhood of Byculla in South Mumbai etc. Also the morning breakfast menu

served at some food joint in Kala Ghoda is recalled by Kolatkar in an overt manner in the poem

Breakfast Time at Kala Ghoda:

They are serving khima pao at Olympia,

dal gosht at Baghdadi,

puri bhaji at Kailash Parbat,

aab gosht at Sarvis,

kebabs with sprigs of mint at Gulshan-e-Iran,

nali nehari at Noor Mohamadis,

baida ghotala at the Oriental,

paya soup at Benazir,

brun maska at Military Caf,

upma at Swagat,

23

shira at Anand vihar,

and fried eggs and bacon at Wayside Inn.

For,yes,its breakfast time at Kala Ghoda

as elsewhere

in and around Bombay (lines 1-15)

In Arun Kolatkars poetry,we see another face of this much-touted art district of Bombay.

The life at the peripheries slowly starts coming to the fore and Kolatkars vision indeed catches

it in its characteristic acts. There is a resurrection of the rubbish,the outcastes,the thrown-away.

Thus lepers,blind men,rat-poison men,potato peelers,street cleaners,shoeshine

boys,dogs,crows,old bicycle tyres,charas pills,kerosene,lice,shitin their veritable third world

make their presence felt in Kolatkars Kala Ghoda. Its not just to the sights of the third world

that Kolatkar draws you but its music,smells,tastes and feels as well. Sometimes its music

comes upon us with a bang and a boom as is expressed in The Boomtown Lepers Band :

Trrrap a boom chaka,shh chaka boom tap. (lines1-2)

During his drinking days,Kolatkar had had his run-ins with the police, being picked up for

disorderly behavior on at least one occasion. Years later, he recalled the jail experience in Kala

Ghoda poems:

Nearer home,in Bombay itself,

the miserable bunch

of drunks,delinquents,smalltime crooks

and the usual suspects

have already been served their morning kanji

in Byculla jail.

24

Theyve been herded together now

and subjected

to an hour of force-fed education.

(VI,lines 1-9)

Kolatkar is aware as a visual artist that a slight manipulation of sight lines, of angle of

vision,can defamiliarize and turn into art what is normally regarded as dull, common place

reality. In the poem Temperature Normal.Pulse,respiration satisfactory published under the

Hospital Poems, we can see Kolatkar experimenting with the subject matter:

i lean back in the armchair

and Bombay sinks

the level of the balcony parapet rises

and the city is submerged

the terraces the chimneys the watertanks the antennas

everything

the whole city

gone under (lines 1-8)

25

By reproducing conversations heard in a restaurant in Three Cups of Tea, Kolatkar

introduced the Bombay urban vernacular, the language of the Indian poetry: A lawyer walks

into Wayside Inn/ softly humming Aasamaa pe hai khuda/ .In Irani Restaurant Bombay,he

introduces seedy restaurant interiors and the bazaar art on their walls:

the cockeyed shah of iran watches the cake

decompose carefully in a cracked showcase;

distracted only by a fly on the make

as it finds in a loafers wrist an operational base.

dogmatically green and elaborate trees defeat

breeze; the crooked swan begs pardon

if it disturb the pond; the road,neat

as a needle,points at a lovely cottage with a garden.

the thirsty loafer sees the stylized perfection

of the landscape,in a glass of water,wobble.

a sticky tea print for his scholarly attention

singles out a verse from the blank testament of the table. (lines 1-

12)

As a Bombay loafer himself, someone who daily trudged the citys footpaths, particularly

the area of Kala Ghoda, Kolatkar is familiar with the locality too well. The view from a

restaurant rather than a restaurant interior is the subject of Kala Ghoda Poems. On most days,

around breakfast time and again in the late afternoon, after the lunch when the crowd had left,

Kolatkar could be found at Wayside Inn in Rampart Row. Sometime in the early 1980s,the idea

of writing a sequence of poems on the street life of Kala Ghoda, encompassing its varied

26

population (the lavatory attendant, the municipal sweeper, the kerosene vendor, the drug

pusher, the shoeshine, the ogress who bathes the baby boy, the idli lady, the rat-poison

man,the cellist,the lawyer), its animals (pi-dog,crow), its statuary (David Sassoon), its

commercial establishments (Lund & Blockley) and its buildings (St Andrews church,Max

Mueller Bhavan, Prince of Wales Museum, Jehangir Art Gallery) ,began to take shape in his

mind.

Being a bilingual poet Arun Kolatkar translated the Marathi poem Main manager ko

bola,part of a sequence of three poems all written in 1960,into English and titled the sequence

Three Cups of Tea published in Arun Kolatkarchya Kavita (1977).

main manager ko bola mujhe pagaar mangta hai

manager bola company ke rule se pagaar ek tarikh ko milega

uski ghadi table pay padi thi

maine ghadi uthake liya

aur manager ko police chowki ka rasta dikhaya

bola agar complaint karna hai toh karlo

mere rule se pagaar ajhee hoga

The second poem is a translation of the first:

i want my pay i said

to the manager

youll get paid said

the manager

but not before the first

dont you know the rules?

coolly I picked up his

wrist watch

27

that lay on his table

wanna bring in the cops

I said

cordin to my rules

Listen baby

i get paid when i say so (lines 1-14)

The language of the first poem is Bombay-Hindi; that of the translation is parody

tough-guy American speech. Occasionally, Kolatkar translated his Marathi poems into English,

but he mostly kept the two separate. His early Marathi poems are what he calls cluster bombs,

densely packed with sounds and metaphors. He created two very different bodies of work of

equal distinction and importance in two languages. He drew his work on a multiplicity of

literary traditions. He drew on the Marathi of course, and Sanskrit, which he knew; he drew on

the English and American traditions, especially Black American music and speech (cordin to

my rules/listen baby/I get paid when i say so); and he drew on the European tradition. He drew

on a few others besides. As he said in an interview once, talking about poets, Anything might

swim into their ken.Kolatkar was evolving towards a conscious style less poetry using

colloquial, common speech. Dilip Chitre has suggested that such poems might be regarded as

an Indian equivalent to the neo-Dada, humorous pop poetry of the 1960s.Dada or Dadaism was

an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20

th

century born out of negative

reaction to the horrors of World War I. The movement was begun by a group of artists and

poets who rejected reason and logic, giving more importance to nonsense, irrationality and

intuition. Neo-Dada is exemplified by its use of modern materials, popular imagery and

absurdist contrast. Kolatkar was also influenced by the poet and bhakta Tukaram and dedicated

a few verses to him in his collection Translations. His early verse in both English and Marathi

often seems surreal; it is obscure and difficult to interpret, but consists of projections of sexual

desires and anxieties into sinister, extraordinary, irrational images.

Kolatkar calls the now Mumbai, a city without soul. In The Shit Sermon he

describes the city as:

Shit city, he thunders;

28

the lion of Bombay thunders,

Shit City!

I shit on you.

You were a group

of seven shitty islands (lines 1-6)

He feels that the city gets more and more unrecognizable with each passing year. It

is with an ironical eye that Kolatkar looks at the cement- eating, blood-guzzling Mumbai of

the present. When he says he finds himself cast in a role that he detests, that of an observer, a

spectator, the irony in his words only intensifies the pain that this poet feels about the slow

disintegration of a city/ I cared about more than any other (David Sassoon). It is this care

and love for Mumbai,which really provokes his bitterness about the soulless way in which the

city keeps changing. Despite all this bitterness, Man of the year, the penultimate poem in the

collection, reveals Kolatkars insatiable longing to remain in this world, and his despair that

time is running out fast:

But nobody knows better than I

that time

is one thing Im running out of fast,

and my one regret is going to be this:

to leave this world

so full of girls I never kissed. (lines 10-15)

By taking an odd, non-committal tone and by bringing in unusual perspectives

Kolatkar turns the commonplace into an aesthetic experience, using the ordinary as the basis

of art. Compared to poetry as it is being written elsewhere, landscape is sparingly used by the

modern poets in Indian poetry. For instance, there is no one like A.R. Ammons whose poetry

gives the impression of subsisting solely on the beaches and rural fields of New Jersey. No one

like Seamus Heaney whose poetry derives its strength from the Irish countryside. Although the

Bombay poets here ignore the countryside, unlike Jayanta Mahapatra and Keki N. Daruwalla.

Needless to say, urban landscape relates the human reality providing glimmerings of the view

of stony city life.

29

Ironical juxtaposition of different cultural quotients, multi-lingual wanderings, unpredictable

imagery, and continuity of themes are characteristics of Kolatkars poetry. Nothing could

escape the poets alert eyes and even the beggar women of Bombay have found their safe haven

in his collection The Barefoot Queen of the Crossroads. Kolatkar reveals that art is made by

the reality. Kolatkars mode of perpetuating a single theme to the length of entire books has by

now become familiar to his readers. All his three books in English, Jejuri, Kala Ghoda Poems

and Sarpa Satra are evidence to his meditative mind, as are his Marathi works,Droan, Bhijki

Vahi (won the Sahitya Akademi award in 2004)and Chirmiri. Perhaps it is the same

unwillingness to let go easily that makes Arun Kolatkar the poet of our times,who belongs,and

wants to always belong to everything that is a part of our age.

Jejuri offers a rich description of India while at the same time performing a complex act of

devotion,discovering the divine trace in a degenerate world. Salman Rushdie called it

sprightly,clear-sighted,deeply felta modern classic. For Arvind Krishna Mehrotra,it

wasamong the finest single poems written in India in the last forty years. Jeet Thayil

attributed its popularity in India to the Kolatkarean voice: unhurried,lit with

whimsy,unpretentious even when making learned literary or mythological allusions. And

whatever the poets eye alights on-particularly the odd,the misshapen,and the famished-

receives the gift of close attention.

Through his Bombay poems, Kolatkar brings into fore two very different dimensions of the

same city. On the one hand, industrialization has polished the central part of the city making it

a desirable end for most of the citizens whereas the reality of the cityscape is preserved among

the impoverished masses. Modern Indian poetry is sustained by the continuing breezes from

the West- which now means Europe as well as America. Today in the Indian situation, poets

cannot afford to ignore the temperature of the environment in which they live and their poems

are born. The Tagore Syndrome of immortal touch of poetry,the cosmic play and the ineffable

joy of the verses are long gone. The modern poets stir the backyard gutter of urban vulgarity

and bathos and pathetic futility, and imitate the modernist techniques of allusiveness, clowning,

multi-linguism and facetiousness to communicate his sense of nausea and disgust. Following

the tradition of Eliot, Kolatkar is definitely disillusioned in the post-war society where the

society has turned into a wasteland. The irregular pace of the verse was chosen deliberately

being suited to the given times and climes of the society and the interpretation of the poets

mood. The poems are numbered but not titled properly; no rhymes, no capital letters, no

30

punctuation marks; no clutching at false hopes, no spouting forth cheap sentiment; it is the

moan of disillusion,naked and un ashamed. In the prefatory note to his The Night is Heavy

(1943) Krishnan Shungloo wrote thus,summing up the predicament of a suffering poet:

in courting life

i have wedded despair

i too have rooted in flesh and spirit

crucified my love on a harlots bed

fraulein i mean

men and women wearing the mask of life

the dead souls of our civilization

we are the gods jest

the cryptic joke

we doubt and have no answer ( lines 5-12)

31

32

CHAPTER TWO: DILIP CHITRE

Dilip Chitre was a noted and influential bilingual poet and translator who worked in Marathi

and English. His literary output in both languages has been sizeable. His versatile creative

practice extends to painting and filmmaking- activities that he saw as seamless extensions of

his poetic sensibility. Poetry, he wrote has been the mainstay of my creative practice for

more than fifty years and it could be my way of wrapping up my life. A prolific poet in

Marathi,Dilip Chitre has published less in English. He was one of the earliest and the most

important influences behind the famous little magazine movement of the sixties in Marathi.

He started Shabda with Arun Kolatkar and Ramesh Samarth.Nevertheless, he privately

published two hundred copies of Ambulance Ride (1972), his first volume of English poems-

Travelling in a Cage- did not appear until 1980.

His poems are mostly autobiographical and, while in a variety of moods ranging from

the lyrical and meditative to the incantatory, reflect what a continuing crisis of his inner life

seems. Influenced by the great Marathi Bhakti poet Tukaram, but himself a rationalist with

mystic learnings, Chitre creates a large, intense world from his emotions, especially his

obsession with sex, madness and death. There is in his work, as is shown by the poem Prayer

to Shakti, a Blakean Romanticism which celebrates living intensely, excessively, and being

open to experience, as a desire to be one with the universe. Not surprisingly, often such poems

develop from free associations, use incantations and invocations which bring the sub- or

unconscious into view. Chitre writes in cycles of lyrics which often have their significance in

the sequence rather than in any individual poem.

Marathi is my given mother tongue. English is my favourite other tongue. They don't

divide me. I will not cohere without either of them says Dilip Chitre in an Interview with The

Indian Express (1998). Being a bilingual poet Chitre believed his bilingualism has baffled

critics. A bilingual writers literary orientation is assumed to be like the erotic orientation of

a bisexual-dangerously ambiguous and oblique, he said. Somehow on either side of the

language divide, ones loyalty to ones audience is held suspect. Such suspicion

notwithstanding, he has earned for himself as a writer of stature in both languages.

On the symposium held in Madras on Poetry India in 1974, Chitre delivered a lecture

on A Home for Every Voice where he said Iam a disturbed poet trying to disturb my fellow-

33

poets and not a theoretician or dialectician pontificating or expounding. As a Marathi,Chitre

was remarkably close to his culture. He feels that an ongoing crisis has affected the very special

ecology of culture. The functional plurality of cultures is besieged and overpowered by an ethos

unlike his own, historically younger and ideologically impatient. Chitre further spoke, We

poets must perceive our ecology and our habitat in terms of language and all that language

feeds on. We should be shaken by the continuous erosion of local and regional colour,the dying

of dialects, the termination of oral traditions, the withering of folklore. The impending

disintegration of tribal culture in Indias heartland is no less serious than the annihilation of

rain forests or the widening holes in the ozone layer. Our bio-diversity is expressed in ethnic,

linguistic, and cultural terms. This made us open to the world. We translated the world into

India just as we transformed ourselves with the help of tribal traditions. As mentioned earlier,

influenced by the Bhakti poet Tukaram, Chitre is of the opinion that, Bhakti,I believe, was

our equivalent of Renaissance Humanism and it is Bhakti upon which our modern polity and

worldview can be founded. The inclusive spirit and the open mind that is free of xenophobia

and cultural prejudice is ever ready to participate in a larger world and regards life not as a

moveable feast but as a liberating and self-renewing experience of pilgrimage.

Chitre seems to ask the following questions to his audience, has the story of Indian

poetry been any different in the last half century? Or is it also a story of a kind of republic in

the making, a levelling of iniquitous hierarchies and dominant traditions? Do we take an

inclusive and pluralistic view of poetry created in India during the last fifty years or are we

members of a parochial elite who have excluded a large number of their own contemporaries

on the grounds that they are not our equals simply because they are not identical with us?

The poet is definitely disturbed by these questions even though they may seem nave,

plebian, or irrelevant.

Chitres first collection of Marathi poetry, Kavita, was published in 1960, followed by

Kavitenantarchya Kavita eighteen years later. His collected Marathi poems,Ekoon Kavita,

appeared in three successive volumes in the nineties, the first volume winning the prestigious

Sahitya Akademi Award in 1994. The year 2008 saw the publication of two important Chitre

collections: Shesha, a volume of new and selected translations from Marathi, and As Is Where

Is, a book of new and selected poems in English.

Chitre always viewed the writing and translation of poetry as part of a continuum. His book,

Says Tuka, is a well-loved and much-acclaimed rendition in English of the haunting poetry of

34

the 17th-century mystic of Maharashtra, Tukaram. It won the Sahitya Akademi award for

translation in the year 1994 (making him the only poet to have won awards for both poetry and

translation in the same year).

He is aware that his ongoing translation of Marathi saint poets (which he began at the age of

16) has a certain subversive canonical significance. I realized, he says in an interview with

The Indian Express (1998), that literature of the West had so overwhelmed us that we seemed

to think that literature was invented there and that we are practitioners of a European art. This

isn't true. We had begun to define ourselves in terms of others. The West was ignorant of our

languages. They thought Marathi was a dialect of Hindi this about a language that is among

the 20 most spoken languages in the world and has a literature that has existed continuously

for 700 years. I took this as a passport to the literary world. I had to show them who my

Shakespeare, my Racine, my Dostoevsky were.

Additionally, translation has meant its own unique challenges and rewards the inheritance of

a complex cultural space. More than three decades of translating Tukaram, wrote Chitre,

have helped me to learn to live with problems that can only be understood by people who

often live in a no-man's land between two linguistic cultures belonging to two distinct

civilizations.

The eight poems in this edition are from Shesha, a selection from Chitres oeuvre in Marathi.

Garnered from a period that spans several decades (from the 1950s to the first decade of the

new millennium), they reveal different facets of Chitres art from the poetry of love to the

poetry of metaphysical reflection, from the poetry of eroticism to the poetry of lyrical elegy,

from the poetry of nostalgia to the poetry of trenchant critique.

One of my personal favorites, says Chitre, is At midnight in the bakery at the corner which

uncovers a deeply subtle and sensual longing. There are no broad political strokes in this poem

of loss and sadness, only an aching memory of the way things were in a world before the lines

between faiths and communities grew inflexible and unforgiving. The passing of an old order,

of a warmer, more innocent history is poignantly evoked in the last line: When the bread

develops its sponge, the smell / Of the entire building fills my nostrils. ( lines 16-17)

Namdeo Dhasal, a quintessentially Marathi Dalit poet, was Dilip Chitres mentor throughout

his life. Raw, raging, associative, almost carnal in its tactility, Dhasals poetry emerges from

35

the underbelly of the city- its menacing, unplumbed netherworld. For Dhasal and for Chitre

too, Bombay is a world of pimps and smugglers, of crooks and petty politicians, of opium dens,

brothels and beleaguered urban tenements. The poetic world of Dilip Chitre can be described

as that of Bombay without her make-up, her botox, her power yoga; the Bombay that seethes,

unruly, menacing yet vitally alive, beneath the glitzy mall and multiplex, the high-rise and

flyover. The Bombay of the non-gentrifiable, the untamable, the non-recyclable.

It is a peculiar characteristic of the Bombay poets that they are often concerned about the

communal clashes which is predominant in India. The reason may be attributed to the very

nature of power politics prevalent in and around Maharashtra; the Shiv Sena crusade with its

parochial set of principles. Even Dilip Chitre feels that the real crisis in contemporary Indian

culturewhere any dissent can be seen as an act aimed at hurting sentimentsis that few of

us are prepared to celebrate the heterogeneity of our cultural heritage. Politicians have always

exploited religion and sectarian faith to create law and order problems. Today, they only need

to announce that their followers sentiments are hurt and we all understand the not-so-veiled

threat to take the law into their own hands. The Staterepresenting the political will of the

peopleis only too glad to clamp down bans, tighten censorship, and muzzle dissent. It only

increases the States own power over the individual citizen and the minorities. Via politics,

religion has wreaked havoc in India since independence. Revivalists and atavists have

succeeded in taking us back to a mythologized past which should have become increasingly

irrelevant to our public life since we embraced our present Constitution. If the executive gives

in to populist pressures and violent threats to any minority, and if even the judiciary succumbs

to majority public opinion, all minority opinion and individual expression is doomed to go

forever underground in this country. His appeal goes to all the secular-minded poets and writers

to unite against communalism. Through his Marathi poetry, he wanted the minorities to raise

their voice; the real world itself is a cluster of probabilities and alternate pathways that we

must find diversification of art-forms and diversity of poetic genius, the natural law governing

poetry.

As an acute observer, such conditions were bound to bother him. At the ripe young age of 16,

Dilip Purushottam Chitre made a decision that would change his life forever. He decided he

wanted to live as a poet and artist. It could not have been an easy choice. He admits to vague

premonitions of it being difficult, and admits it proved hard at times. And yet, after over fifty

years of living that life of poet and artist, he stands by it, refusing to have it any other way.

Chitre considers himself a pluri-lingual like many other South Asian writers. Kolatkar,

36

Nagarkar, Vilas Sarang and Damodar Prabhu are what he would call his contemporary Anglo-

Marathi writers. There are Anglo-Bangla, Anglo-Malayalam and Anglo-Oriya poets, among

his contemporaries. Their individual histories as bilingual writers are very different though, if

that matters. Most Bombay poets are not originally from the city and have precisely migrated

there, uprooted from other states, small cities or rural backgrounds (Dilip Chitre came from

Gujarat, Arun Kolatkar from Kolhapur, a small town in South Maharashtra, etc.). When they

were born or brought up in Bombay, they often come from religious minorities who, at one

point in time, also found refuge in the city,like Adil Jussawalla and Gieve Patel who are Parsi

or Nissim Ezekiel who was Jewish.

Better known as a Bombay poet,Chitres Bombay poems reveal an alienation and attempt to

use poetry as a means of holding together an otherwise fragmented reality. Bombay is a symbol

of the modern Indian chaos resulting from contact with the West and of mans estrangement

from a manmade world. His early poems in Marathi were written between the age of 15 and

21. They begin with his experience of uprooting from his native place Baroda. Chitre has been

writing poetry seriously since the age of about 16, when he took the momentous decision to

live as a poet and an artist. He had an ambiguous intuition it was not going to be an easy life.

It did prove very difficult indeed, at times. However, his curiosity and the realm of human

experience made his life an exciting adventure and he was rewarded, from time to time, by

revelations that constitute the fundamental aspect of his work, the insights that made it

worthwhile to be a poet and an artist. He entered Bombay when he attained puberty.

Simultaneously, Bombay entered his poetry. Being a precocious reader, his grounding in

literature was wider and deeper than his academic upbringing, and often at variance with it.He

was passionately interested in music, photography, drawing, and painting since the age of 10.

In Bombay, he had opportunities to mingle with artists, musicians, film technicians and

photographers much older than himself.

He met Pandit Sharadchandra Arolkar, an outstanding vocalist of the Gwalior Gharana at age

16. He was a daily visitor to his home in Shivaji Park until he left for Ethiopia. He was a

profound influence on Chitres ideas of art, not just music. Bombay figures in his early Marathi

and English poetry in different ways and at several levels. He perceived the metropolis in

juxtaposition with primordial nature as perceived in his childhood. There was a discord. There

was a sense of manmade alienation that haunted him.

37

Though most of his early poetry is metrical and sometimes stylized, it was spontaneous and

unpremeditated. The big city's polyphony, its cacophony as well, its many human voices and

points of view, made him move towards more accommodative, open-ended, cadenced free

verse and the rhythms of colloquial speech. His early poetry was sensuous, erotic, and exuded

a kind of sexuality that was instinctive and natural to him in his youth. Yet, he felt he was being

robbed of his youth itself by the big city where human values come to die, lured by its opulence

and glitz. In the poem At midnight in the Bakery at the Corner, Chitre deals with this very

issue of sexual advances by his friends wife in an oblique manner. Although he refuses at first

but towards the end, he succumbs to the call of bodily instincts. The underlying meaning of the

poem is veiled by an apparent discussion on childhood nostalgia, the poet getting drunk after

his friends left for the Gulf countries. Its only at the end that a vague suggestion is made when,

The wife of the Pathan next door enters my room

Closes the door and turns her back to me

I tell her, sister, go find somenone else (lines 13-15)

In the poem Ode to Bombay Chitre brings out various facets of the city; the crowded

apartments, human beings turned into mindless machines, the ambivalent positioning of the

temple and brothels on the same street, communal murders and riots. He says, before he dies

shall dedicate a poem to this city but the decaying nature of its existence forces him to tersely

terminate the verse;

Once I promised you an epic

And now you have robbed me

You have reduced me to rubble( lines 19-21)

Chitre dared to face an ugly world, he refuses to aestheticize it in his poetry. Bombay became

for him a map and a metaphor for the larger world. It prepared him for all the later big cities in

his life: Chicago, New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, London, Paris, Moscow, St.

Petersburg, Berlin, Tokyo and Hong Kong, for example. All of them had something of

Mumbai in them. Cities in his work connect with all the major themes of life and death,

though the countryside is equally present.

38

Dilip Chitres poetry is characterized by an easy, fluent, unpunctuated line, a ruminating

manner that lingers lovingly over both the sunlight and the shadow in his moods and insights

that flare like matches in a dim-lit vault. His black moods never weigh heavy on the reader,

but drift away like cloud shadows. Some of his poems are charged with a storming energy,

e.g. Scattered the Mind which manages to convey, not to the mind, but to the gut as it were,

the seething chaos of the Indian scene. The torn and blistered railway lines metaphorically

casts a blight on the subcontinent. He has a sharp eye and nose for the sights and smells of his

native city, Bombay. In the poem he calls the city a garbled relic because it carries the

legacy of a long European tradition. Bombay was handcrafted by the Britishers and they

played an instrumental role in shaping and showing the way to modernism. Recalling the

days of Raj, Chitre says the city still lures the citizen with the Englishmen clubs and

concubines and the jokes they entertained. The English dignity is represented by Victoria

Terminus in the poem Bombay boulevard:

only in Bombay

some English dignity remains

Victoria Terminus

that gothic foundation of our modernity

still stands majestically(lines 6-11)

The poem also takes us back to one of the most controversial periods of independent Indias

history, the Emergency (1975-77) when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi unilaterally had a

state of emergency declared across the country. For much of the Emergency, most of

Gandhis political opponents were imprisoned and the press was censored. Several other

atrocities were reported from the time, including a forced mass-sterilization campaign. There

was destruction of the slum and low-income housing near the suburbs of Bombay and the

Jama Masjid area of Old Delhi. All these hitches in the countrys history have been briefly

mentioned by Chitre in this poem. For him, Bombay is a shrinking island crowded by

smugglers and displaced bastards. Now these displaced bastards could be the migrants from

different communities sharing the same space with the native population,we dont know.The

shimmering glow of modernity is juxtaposed with the reality of the native squalor filled by

the voices of coolies and poets.

39

Chitre, who lived in Ethiopia for four years and in America where he joined the International

Writing Program of the University of Iowa in the US as an invited Fellow, uses the

schizophrenic search for identity as a source of his poetry. The collection Travelling in a

Cage is a remarkable long poem of 17 sections. In these poems written while in exile the

poets relationship to the new country becomes a metaphor for his relationship to himself, its