Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

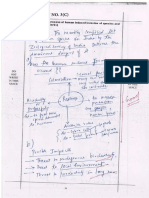

Idea of Pan Islamic

Загружено:

Assif YousufАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Idea of Pan Islamic

Загружено:

Assif YousufАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Sumanta Banerjee, in his review of Meredith Taxs book Double Bind: The Muslim Right, the Anglo-

American Left, and Universal Human Rights (The Left and Political Islam, EPW, 30 March 2013), has

underlined the mistakes of sections of the left in their understanding of political Islam both in India

and abroad. These mistakes, he claimed in the introduction to his review of the book, are the legacy

of Vladimir Lenins idea of accommodating political Islam in the anti-imperialist programme in the

early 1920s. While judging Lenins strategy, it seems that he has taken an ahistorical position, and

has viewed the role of the Islamic movement only from the ideo- logical premise, without

considering the transformative character of any archaic ideology prevailing within the masses and

being advocated by their proponents under circumstantial pressure built within diverse time-space

continuums, and under the pressure of the class-interest and aspiration of the people whom the

move- ment intends to grasp. The ideology of political Islam is on the assumption made implicitly or

explicitly that Muslim societies form a self-consistent, extraterritorial and trans- historical unit. This

may be described summarily by a small number of de ni- tively constituted generic features tran-

scending space, time and circumstances. These features are at once derived from, and foreclosed by,

Muslim scriptures, and the early historical experience of Muslims and their incapacity to think of

political arrangement in terms of civic pluralism, and to rest forever content with an arrangement of

public affairs ruled by a medieval legal system (Al-Azmeh 2005). This ideological thinking is be tting

with the imperialist desire to use Islam for a world order that serves the interest of the imperialists.

But, it is no denying the fact that the Muslim community from

national as well as global perspectives is an oppressed community under an imperi- alistic and

hegemonic world order and as such the forces with the reactionary ideo- logical moorings who are

spearheading the resistance movement always have two polar opposite tendencies one to trans-

form itself to side with the progressive classes and other anti-imperialist forces, and the other to

resolve the con ict of ideology and politics to take direct refuge in the imperialist camp. The policy

frame- work of the left should take these two opposing tendencies into cognisance.

Indian Perspective Islamic universalism in India was a by- product of European imperialist policies

and predated Jamaluddin al-Afghanis efforts to rally Muslims behind the Ottoman bid for the

caliphate. Afghanis posthu mous reputation as the intellectual progenitor of Islamic universalist

politics in India was not unearned. After all, he had preached Hindu-Muslim unity and waxed

eloquent on the virtues of territorial nationalism. There were always historical links between the

ideologues of radical Islam based on the interpretation of jihad, and anti-colonial nationalism in

south Asia and west Asia. While sharing dis- taste for western imperialism, they avoid a rigid

separation between worldly and religious points of view. The jihad as anti-colonial nationalism

transforms itself into jihad as terrorism in the face of the weakening of the peoples resistance

against imperialist and national- hegemonic subversion. During the period of the rising tide of the

mass activity of anti-colonial nationalism, jihadi Islam also engaged in a vibrant dialogue with ijtihad

(independent reasoning). That is why Muhammad Iqbal applauded the Turks for vesting

responsibility for collec- tive ijtihad in an elected assembly (Jalal 2008). The republican form of

government was not only thoroughly consistent with the spirit of Islam, but had also become a

necessity in view of the new forces that were set free in the world of Islam. In the anti-colonial

struggle in India, the Khilafat movement, along with M K Gandhis jana-satyagraha (mass civil

DISCUSSION

january 4, 2014 vol xlix no 1 EPW Economic & Political Weekly70

disobedience), had unleashed a large-scale militant peasant movement against the British

colonialists. This united Hindu- Muslim struggle might have led the move- ment to its evident

culmination of attain- ing actual freedom, had Gandhi not termi- nated his programme of satyagraha

at a crucial juncture. Gandhis desire to fuse his campaign for non-cooperation with the Khilafat

movement launched by Indian Muslims in 1919 to prevent the dismem- berment of the Ottoman

Empire and preserve intact the spiritual and temporal authority of the Ottoman S ultan as the

Caliph of Islam was an organisational success in Gorakhpur (Amin). In the winter of 1921-22, the

Khilafat and Congress Vol- unteer Organisations were merged into a composite National Volunteer

Corps. After the incident of Chauri Chaura and in the backdrop of rising peasant militancy emerging

from Hindu-Muslim unity, Gandhi suspended the satyagraha movement and, thus, paved the way for

disunity and left the people branded with violence to endure all manner of sufferings for years to

come.

Leninist Formulation That these regions became so vulnerable can be explained by the fact that the

rela- tions between Crown Prince Amanullah of Afghanistan and Britain were not at all amicable, and

Russias central Asian possessions had already become a bone of contention in the Anglo-Russian

relations in the pre-revolutionary period, notwith- standing the fact that Russia and Britain were

allies in the rst world war. Thus, immediately after the revolution, Abdul Jabbar Khairy and Abdul

Sattar Khairy, two pan-Islamists, had travelled to Russia in November 1918, under the pseudo- nyms

Professor Ahmed Harris and Pro- fessor Ahmed Hadi, respectively. This was followed by the historic

meeting bet- ween Lenin and an Indian delegation comprising, among others, Raja Mahendra Pratap

and Moulana Barakatullah on 7 March 1918. Despite the pan-Islamic faith of Barakat- ullah, he was a

nationalist, and Lenin himself attached great importance to a united nationalist front for the

colonies. Lenins Imperialism, followed by the Colonial Theses, was adopted at the

Second Congress of Comintern in 1920. Lenins formulation that Comintern was required to extend

support to nationalist movements in the colonial countries was rejected by M N Roy, a position very

similar to the position of Leon Trotsky who believed in proletarian revolution in a colony like India

(Gupta 2006; Chowdhuri 2011). In consonance with this theoretical position, the Indian

Revolutionary Asso- ciation (IRA) was formed with Lenins support, and despite its strong inclination

towards pan-Islamism, Lenin had no dif- culty in considering the IRA as a possi- ble ally while

formulating the strategy of anti-imperialist struggle. The rest of the history of anti-colonialist

struggle did not in any way underline Lenins strate- gic mistake in formulating a broad anti-

imperialist united front. So, to relate the failure of Lenins strategy in one particular case with his

stand on the Islamic movement, and to advocate a uniform strategic line denounc- ing the

movement of the radical Islam instead of taking a stand through a con- crete class-analysis of the

concrete situa- tion, is guided by a deterministic approach.

Jihad against Imperialism A multilayered concept like jihad is best understood with reference to the

histori- cal evolution of the idea in response to the shifting requirements of the Muslim community.

So, jihad in the postcolonial era has been more effective as an instru- ment of political opposition to

the secular modernity promoted by Muslim nation states than that of resistance to western

domination. The present phase of capi- talist neo-liberalism has further eroded the content of

resistance of political Islam against the oppressor. Evidently, only the new socialist project can

transcend capitalist neo-liberalism, which has the capacity to absorb not only all variants of jihadi

pan-Islamist resistance against imperialist oppression, but also certain kinds of modernists

movements. But this does not mean that the left should not distinguish between the pan-Islamist

forces promoted and patronised by the imperialists and the pan-Islamist mass resistance against

direct imperialist onslaught.

Going a step further, Sumanta Banerjee lamented that the left has not strived much to impel the

Indian state to take measures to stop the propagation of fascist ideology under the garb of religious

freedom. He even envisaged that the left should engage themselves in a pitched battle on the street

with Islamic forces to ensure the freedom of littrateurs like Taslima Nasrin and Salman Rushdie.

This one-dimensional approach to de ne demo- cracy and the limits of tolerance in demo- cracy

does not take the two different but interdependent contradictions prevailing in the here and now

into cognisance. People cannot live without their past, but they always face a civilisational pull of

progress not to live within it. People identify themselves with the separate causes of the oppressor

and the oppressed communities in a developing country like India, and, at the same time, like to

engage themselves in the ongoing strug- gle for eradication of this division of inequality for a

common cause. While advocating the British cultural tendency to conceive of democracy

instrumentally, one should remember that at one level, modern British history may be a history of

progressive democratisation, but, at another, it is also a history of expanding state authority and

coercion. Instead of imposing a strict rule of behavioural democracy, we should rely more on the

internal dynamics of contend- ing opinions operating within the garb of community rights and

freedom, and make space for internal debates to ourish through democratic empowerment. If the

left does not recognise this internal dynamic and imposes behavioural norms decided by the left

groups and the state, then what will happen to Lenins distinc- tion between the role of the

communists from the oppressed community and from the oppressor community?

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Frictions Within Bureaucracy QДокумент3 страницыThe Frictions Within Bureaucracy QAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Q 3 (C) Q4 (C) Q5 (B) Q5 (C) Vineet Kumar1Документ12 страницQ 3 (C) Q4 (C) Q5 (B) Q5 (C) Vineet Kumar1Assif YousufОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Enough of Aid Lets Talk ReparationsДокумент3 страницыEnough of Aid Lets Talk ReparationsAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- Settlement Under LoadsДокумент33 страницыSettlement Under LoadsAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- IASbabas Frontline IDSaДокумент29 страницIASbabas Frontline IDSaAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- Career Objective: Inam Ul HaqДокумент2 страницыCareer Objective: Inam Ul HaqAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Fdi 2018Документ5 страницFdi 2018Assif YousufОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Test 2Документ3 страницыTest 2Assif YousufОценок пока нет

- Saad Miya Khan Test 1 Checked CompressedДокумент39 страницSaad Miya Khan Test 1 Checked CompressedAssif Yousuf100% (2)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- CITIZENS' CHARTERS GUIDEДокумент7 страницCITIZENS' CHARTERS GUIDEAshish GuptaОценок пока нет

- Crossroads Final Report With Appendix PDFДокумент116 страницCrossroads Final Report With Appendix PDFAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- Lessons From Semi-Arid Regions On How To Adapt To Climate ChangeДокумент3 страницыLessons From Semi-Arid Regions On How To Adapt To Climate ChangeAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Numerical Reasoning FormulaeДокумент7 страницNumerical Reasoning FormulaeAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- Capstone Report FormatДокумент10 страницCapstone Report FormatArvin F. VillodresОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Hum Kadam Dialogues - BackgroundДокумент3 страницыHum Kadam Dialogues - BackgroundAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Annual Calendar 2015Документ1 страницаAnnual Calendar 2015burningdreams24x7Оценок пока нет

- Academic Calendar of Autumn Term 2014-15 For Regular ProgrammesДокумент2 страницыAcademic Calendar of Autumn Term 2014-15 For Regular Programmespremadhikari007Оценок пока нет

- Final Book Price List - ColourДокумент2 страницыFinal Book Price List - ColourAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- Hum Kadam Dialogues - Concept NoteДокумент3 страницыHum Kadam Dialogues - Concept NoteAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- Building Project ReportДокумент32 страницыBuilding Project ReportAssif Yousuf100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Electrical ScienceДокумент9 страницElectrical ScienceAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Regulated Power SupplyДокумент22 страницыRegulated Power SupplyAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- Ishfaq ReportДокумент30 страницIshfaq ReportAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- LNM 1Документ42 страницыLNM 1KANHIYA78100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Department of Civil Engineering POSTERS For (A) CES Competition and (B) Open House 2014Документ1 страницаDepartment of Civil Engineering POSTERS For (A) CES Competition and (B) Open House 2014Assif YousufОценок пока нет

- SIKA Shotcrete HandbookДокумент38 страницSIKA Shotcrete Handbooktantenghui100% (1)

- 8085 MicroprocessorДокумент23 страницы8085 Microprocessorauromaaroot196% (55)

- 4 - Academic Benefits PolicyДокумент1 страница4 - Academic Benefits PolicyAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Environmental Management PlanДокумент31 страницаEnvironmental Management PlanAssif Yousuf100% (3)

- Process Tree For Highway ConstructionДокумент1 страницаProcess Tree For Highway ConstructionAssif YousufОценок пока нет

- Encyclopædia Americana - Vol II PDFДокумент620 страницEncyclopædia Americana - Vol II PDFRodrigo SilvaОценок пока нет

- 44B Villegas V Hiu Chiong Tsai Pao Ho PDFДокумент2 страницы44B Villegas V Hiu Chiong Tsai Pao Ho PDFKJPL_1987Оценок пока нет

- EXL ServiceДокумент2 страницыEXL ServiceMohit MishraОценок пока нет

- SYD611S Individual Assignment 2024Документ2 страницыSYD611S Individual Assignment 2024Amunyela FelistasОценок пока нет

- Flowserve Corp Case StudyДокумент3 страницыFlowserve Corp Case Studytexwan_Оценок пока нет

- IPR and Outer Spaces Activities FinalДокумент25 страницIPR and Outer Spaces Activities FinalKarthickОценок пока нет

- Mobile phone controlled car locking systemДокумент13 страницMobile phone controlled car locking systemKevin Adrian ZorillaОценок пока нет

- 8098 pt1Документ385 страниц8098 pt1Hotib PerwiraОценок пока нет

- SECTION 26. Registration of Threatened and Exotic Wildlife in The Possession of Private Persons. - NoДокумент5 страницSECTION 26. Registration of Threatened and Exotic Wildlife in The Possession of Private Persons. - NoAron PanturillaОценок пока нет

- Year 2019 Current Affairs - English - January To December 2019 MCQ by Sarkari Job News PDFДокумент232 страницыYear 2019 Current Affairs - English - January To December 2019 MCQ by Sarkari Job News PDFAnujОценок пока нет

- Legal Notice: Submitted By: Amit Grover Bba L.LB (H) Section B A3221515130Документ9 страницLegal Notice: Submitted By: Amit Grover Bba L.LB (H) Section B A3221515130Amit GroverОценок пока нет

- 4 - Factors Affecting ConformityДокумент8 страниц4 - Factors Affecting ConformityKirill MomohОценок пока нет

- NSS 87Документ2 страницыNSS 87Mahalakshmi Susila100% (1)

- CIAC jurisdiction over construction disputesДокумент4 страницыCIAC jurisdiction over construction disputesxyrakrezelОценок пока нет

- Lic Form 3815 BДокумент2 страницыLic Form 3815 BKaushal Sharma100% (1)

- Strategic Road Map For A Better Internet Café IndustryДокумент12 страницStrategic Road Map For A Better Internet Café Industrygener moradaОценок пока нет

- CV Experienced Marketing ProfessionalДокумент2 страницыCV Experienced Marketing ProfessionalPankaj JaiswalОценок пока нет

- Engineering Economy 2ed Edition: January 2018Документ12 страницEngineering Economy 2ed Edition: January 2018anup chauhanОценок пока нет

- Tax 2 AssignmentДокумент6 страницTax 2 AssignmentKim EcarmaОценок пока нет

- AACCSA Journal of Trade and Business V.1 No. 1Документ90 страницAACCSA Journal of Trade and Business V.1 No. 1Peter MuigaiОценок пока нет

- MG6863 - ENGINEERING ECONOMICS - Question BankДокумент19 страницMG6863 - ENGINEERING ECONOMICS - Question BankSRMBALAAОценок пока нет

- 721-1002-000 Ad 0Документ124 страницы721-1002-000 Ad 0rashmi mОценок пока нет

- History, and Culture of DenmarkДокумент14 страницHistory, and Culture of DenmarkRina ApriliaОценок пока нет

- NBA Live Mobile Lineup with Jeremy Lin, LeBron James, Dirk NowitzkiДокумент41 страницаNBA Live Mobile Lineup with Jeremy Lin, LeBron James, Dirk NowitzkiCCMbasketОценок пока нет

- School Form 10 SF10 Learners Permanent Academic Record For Elementary SchoolДокумент10 страницSchool Form 10 SF10 Learners Permanent Academic Record For Elementary SchoolRene ManansalaОценок пока нет

- Ombudsman Complaint - TolentinoДокумент5 страницOmbudsman Complaint - TolentinoReginaldo BucuОценок пока нет

- Electricity TariffsДокумент5 страницElectricity TariffsaliОценок пока нет

- Florida SUS Matrix Guide 2020Документ3 страницыFlorida SUS Matrix Guide 2020mortensenkОценок пока нет

- Courtroom Etiquette and ProcedureДокумент3 страницыCourtroom Etiquette and ProcedureVineethSundarОценок пока нет

- Decathlon - Retail Management UpdatedДокумент15 страницDecathlon - Retail Management UpdatedManu SrivastavaОценок пока нет

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentОт EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (6)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziОт EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (157)

- North Korea Confidential: Private Markets, Fashion Trends, Prison Camps, Dissenters and DefectorsОт EverandNorth Korea Confidential: Private Markets, Fashion Trends, Prison Camps, Dissenters and DefectorsРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (106)

- Ask a North Korean: Defectors Talk About Their Lives Inside the World's Most Secretive NationОт EverandAsk a North Korean: Defectors Talk About Their Lives Inside the World's Most Secretive NationРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (31)

- No Mission Is Impossible: The Death-Defying Missions of the Israeli Special ForcesОт EverandNo Mission Is Impossible: The Death-Defying Missions of the Israeli Special ForcesРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (7)

- The Showman: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr ZelenskyОт EverandThe Showman: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr ZelenskyРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (3)

- From Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaОт EverandFrom Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (23)